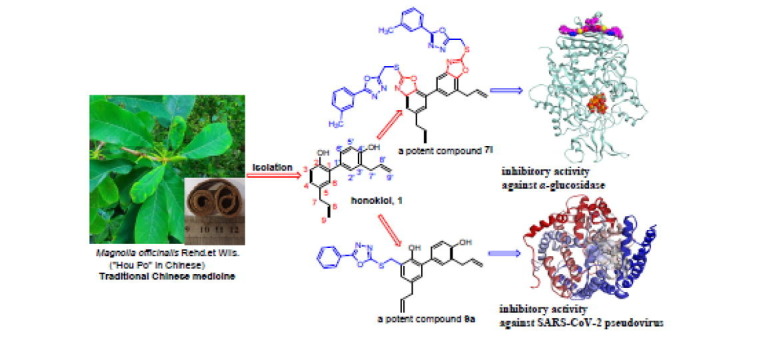

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Honokiol; Thioethers; 1,3,4-Oxadiazole; α-Glucosidase inhibitor; SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitor

Abstract

Honokiol, isolated from a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) Magnolia officinalis, is a biphenolic compound with several biological activities. To improve and broaden its biological activity, herein, two series of honokiol thioethers bearing 1,3,4-oxadiazole moieties were prepared and assessed for their α-glucosidase and SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitory activities. Among all the honokiol thioethers, compound 7l exhibited the strongest α-glucosidase inhibitory effect with an IC50 value of 18.9 ± 2.3 µM, which was superior to the reference drug acarbose (IC50 = 24.4 ± 0.3 µM). Some interesting results of structure–activity relationships (SARs) have also been discussed. Enzyme kinetic study demonstrated that 7l was a noncompetitive α-glucosidase inhibitor, which was further supported by the results of molecular docking. Moreover, honokiol thioethers 7e, 9a, 9e, and 9r exhibited potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entering into HEK-293 T-ACE2h. Especially 9a displayed the strongest inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entry with an IC50 value of 16.96 ± 2.45 μM, which was lower than the positive control Evans blue (21.98 ± 1.98 μM). Biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding and docking studies suggested that 9a and 9r may effectively block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the host ACE2 receptor through dual recognition of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2. Additionally, the potent honokiol thioethers 7l, 9a, and 9r displayed relatively no cytotoxicity to normal cells (LO2). These findings will provide a theoretical basis for the discovery of honokiol derivatives as potential both α-glucosidase and SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors.

1. Introduction

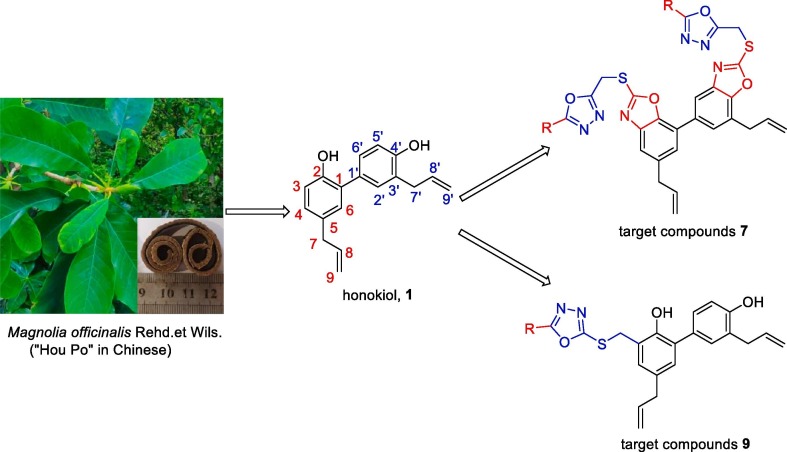

Natural products are the components or metabolites of animals, plant extracts, insects, marine organisms, and microorganisms, which serve as the molecular basis for Chinese herbal medicine to perform pharmacodynamic functions.1, 2 Natural products have long been appreciated for their chemical diversity, biochemical specificity, and other molecular properties that make them suitable as lead structures for drug discovery.3, 4, 5 From 1981 to 2014, >59% of new drugs approved by the US FDA were derived directly or indirectly from natural products.1 Currently, 70–95% of the global population are using traditional medicinal herbs and their natural bioactive ingredients for disease treatment or prevention, and over 50% of all clinical medicines are from natural substances or their derivatives.4, 5, 6 The Chinese herbal medicine “Hou Po” is derived from the bark of the Magnolia officinalis plant (Fig. 1 ), and has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine formulas or Chinese patent medications. “Hou Po” has been proven to have many pharmacological effects such as antiaging, antitumor, and antidiabetic.7, 8, 9, 10 Honokiol (1, Fig. 1), an important biphenolic component of Magnolia officinalis Rehd et Wils., has piqued the interest of a growing number of researchers due to its good biological activity, high targeting, and low toxicity.11, 12, 13 Several recent studies in vivo and in vitro models have demonstrated multiple biological efficacies of honokiol, including anti-angiogenesis,14 anticancer,15, 16 antiviral,17 anti-inflammatory,18 antioxidant activities.19 In addition, recently, honokiol has been reported to have a good inhibitory effect on SARS-COV-2 infection.20, 21, 22 However, little attention has been paid so far to the biological activities of honokiol derivatives in the treatment of diabetes and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fig. 1.

Honokiol and its thioether derivatives derived from Magnolia officinalis.

Based on the above-mentioned, and in our continuous efforts to improve and broaden the biological activity of honokiol,23, 24 herein, we have successfully prepared two series of honokiol thioethers containing 1,3,4-oxadiazole moieties (7 and 9, Fig. 1), and evaluated their α-glucosidase and SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitory activities.

2. Results and discussion

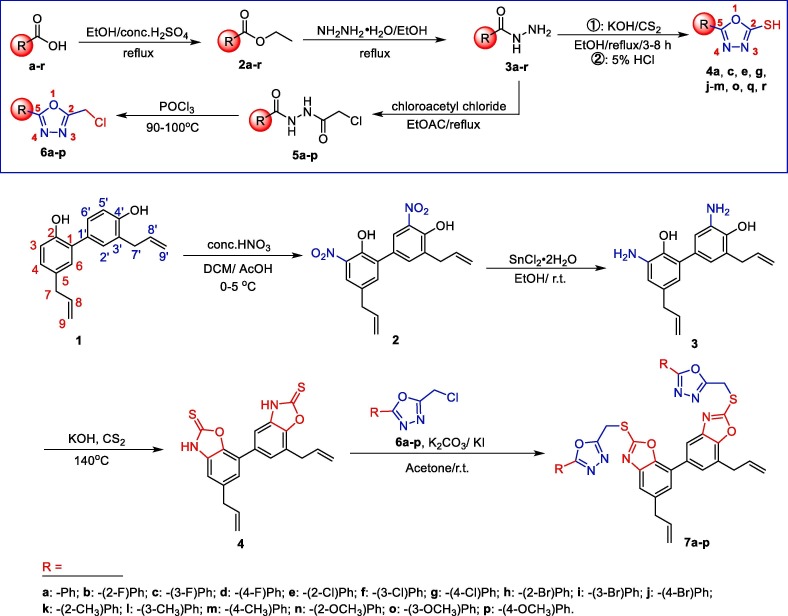

2.1. Preparation of honokiol thioethers bearing the 1,3,4-oxadiazole moiety (7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r)

As shown in Scheme 1 , we first synthesized the key intermediates (4a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, r) and (6a–p) through two different routes using various substituted aryl acids according to the reported methods.25, 26 Subsequently, the honokiol was reacted with concentrated nitric acid (HNO3) to obtain 3,5′-dinitrohonokiol (2) in a high yield. Then, the reduction of compound 2 in the presence of SnCl2 to give 3,5′-diaminohonokiol (3), followed by the cyclization of 3 with carbon disulfide (CS2) to afford a key intermediate 4 at 140 °C. In the end, with the intermediate 4 in hand, it was reacted with the corresponding 2-chloromethyl-5-substituted phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles (6a–p) to obtain the disubstituted honokiol thioethers 7a–p.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes of honokiol dithioether derivatives 7a–p.

Additionally, as Scheme 2 displays, honokiol and iodine (I2) were reacted to give an iodocyclization compound 5, and then the hydroxymethylation of 5 produced intermediate 6 with formaldehyde (HCHO) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Afterwards, intermediate 6 was ring-opened in the presence of zinc and acetic acid to obtain compound 7, followed by a chlorination reaction to give another important intermediate 8. Finally, the monosubstituted honokiol thioethers 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r were achieved by the reaction of compound 8 with the intermediates 5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiols (4a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, r) in the presence of potassium carbonate (K2CO3) and potassium iodide (KI). All the title honokiol thioethers have purity > 95% by HPLC assay. Moreover, structures of all the title honokiol thioethers 7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r were characterized by IR, 1H/13C NMR, and HR-MS spectral analyses.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic routes of honokiol monosulfide derivatives 9a–c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r.

2.2. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity and structure–activity relationships (SARs)

All the title honokiol thioethers (7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r) were evaluated for their in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activities with the reference drug acarbose as a positive control.27 As shown in Table 1 , after the introduction of the 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring on the precursor honokiol, most of the target honokiol thioethers displayed more potent α-glucosidase inhibitory activities than honokiol. Among them, honokiol thioethers 7h, 7k, 7l, 7o, and 9o showed outstanding inhibitory activities with inhibition rates of 91.5%, 95.3%, 95.2%, 95.5%, and 81.8%, respectively. To further investigate the α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of potent derivatives 7h, 7k, 7l, 7o, and 9o, their IC50 values were determined as 25.8 ± 2.3, 25.0 ± 1.9, 18.9 ± 2.3, 24.5 ± 2.0, and 52.9 ± 3.4 µM, respectively. In particular, derivative 7l exhibited the strongest inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 18.9 ± 2.3 µM, which was more potent than the reference drug acarbose (24.4 ± 0.3 µM).

Table 1.

In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of honokiol thioethers.a

| Compound | Substituent (R) | Inhibition rate (%) | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | –Ph | 6.3 ± 1.7 | –b |

| 7b | –(2-F)Ph | 33.9 ± 2.8 | – |

| 7c | –(3-F)Ph | 14.6 ± 1.9 | – |

| 7d | –(4-F)Ph | 8.4 ± 0.4 | – |

| 7e | –(2-Cl)Ph | 19.4 ± 3.1 | – |

| 7f | –(3-Cl)Ph | 10.4 ± 1.4 | – |

| 7g | –(4-Cl)Ph | 57.9 ± 2.6 | – |

| 7h | –(2-Br)Ph | 91.5 ± 0.1 | 25.8 ± 2.3 |

| 7i | –(3-Br)Ph | 12.4 ± 2.3 | – |

| 7j | –(4-Br)Ph | 22.4 ± 1.4 | – |

| 7k | –(2-CH3)Ph | 95.3 ± 1.6 | 25.0 ± 1.9 |

| 7l | –(3-CH3)Ph | 95.2 ± 0.4 | 18.9 ± 2.3 |

| 7m | –(4-CH3)Ph | 13.5 ± 0.3 | – |

| 7n | –(2-OCH3)Ph | 25.2 ± 1.6 | – |

| 7o | –(3-OCH3)Ph | 95.5 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 2.0 |

| 7p | –(4-OCH3)Ph | 9.9 ± 0.4 | – |

| 9a | -Ph | 69.8 ± 3.8 | – |

| 9c | –(3-F)Ph | 53.5 ± 1.5 | – |

| 9e | –(2-Cl)Ph | 64.5 ± 2.5 | – |

| 9g | –(4-Cl)Ph | 7.1 ± 1.3 | – |

| 9j | –(4-Br)Ph | 3.7 ± 0.1 | – |

| 9k | –(2-CH3)Ph | 64.5 ± 2.1 | – |

| 9l | –(3-CH3)Ph | 78.2 ± 0.1 | – |

| 9m | –(4-CH3)Ph | 6.7 ± 0.6 | – |

| 9o | –(3-OCH3)Ph | 81.8 ± 2.1 | 52.9 ± 3.4 |

| 9q | –(4-NO2)Ph | 79.5 ± 0.1 | – |

| 9r | 3-pyridyl | 33.2 ± 2.1 | – |

| honokiol | / | 17.1 ± 1.7 | – |

| acarbosec | / | 96.4 ± 0.5 | 24.4 ± 0.3 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Not determined; cAcarbose was used as the positive control.

Furthermore, some interesting structure–activity relationships (SARs) were also obtained. The SARs revealed that in the series of honokiol dithioether derivatives (7a–p), the derivatives were more active when there was a substituent on the phenyl group of the 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring than that of no substituent on the phenyl group. For example, among compounds 7a–p, 7a (R = -Ph) exhibited the weakest inhibitory effect with an inhibition rate of only 6.3%. When the halogen groups substituted on the phenyl ring of the 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring, the introduction of 5-(2-bromophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole ring on honokiol gave the most active compounds than that of other 5-(halogenphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole rings. For example, the inhibition rate of 7h was 91.5%, whereas the inhibition rates of 7b-g, 7i, and 7k were 33.9%, 14.6%, 8.4%, 19.4%, 10.4%, 57.9%, 12.4%, and 22.4%, respectively. When electron donating groups (EDGs) substituted on the phenyl ring of the 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring, the introduction of 5-(2-methylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole, 5-(3-methylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole or 5-(3-meoxylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole on honokiol could enhance the α-glucosidase inhibitory effect {e.g. 7k [R = –(2-CH3)Ph] vs. 7m [R = –(4-CH3)Ph], and 7o [R = –(3-OCH3)Ph] vs. 7p [R = –(4-OCH3)Ph]}. Additionally, in the series of honokiol monosulfide derivatives, it was also found that the introduction of 5-(3-meoxylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole on honokiol could result in a more potent derivative than those of other 1,3,4-oxadiazoles. Among honokiol monosulfide derivatives, 9o displayed the best α-glucosidase inhibitory activity.

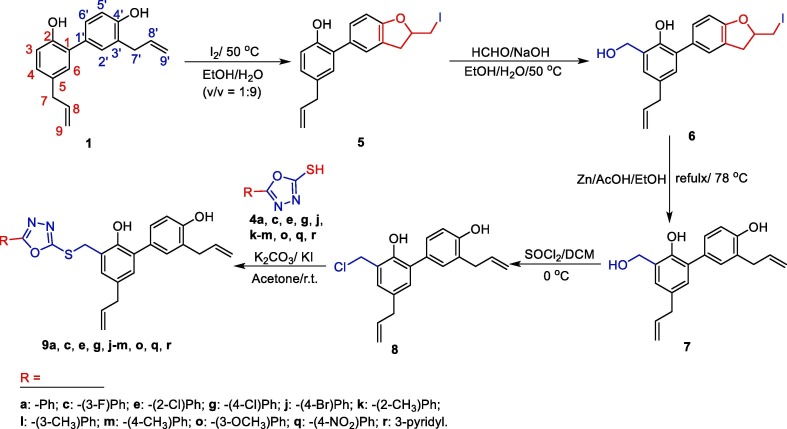

2.3. Kinetic and molecular docking studies

To investigate the inhibition mode of honokiol thioethers towards α-glucosidase, the enzyme kinetic of the potent derivative 7l was analyzed by using the Lineweaver-Burk plot.27, 28 As revealed in Fig. 2 A, the Vm values gradually declined with increasing of the concentration of inhibitor 7l at a constant Km value. Consequently, this result indicated that the inhibitor 7l was a noncompetitive inhibitor against α-glucosidase. Additionally, the Ki value of inhibitor 7l was determined by the Dixon plot method to be approximately 20.8 µM (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Kinetic studies of compound 7l against α-glucosidase. (A): The Lineweaver–Burk plot in the absence and presence of different concentrations of 7l; (B): The Dixon plot in the presence of different concentrations of p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (PNPG).

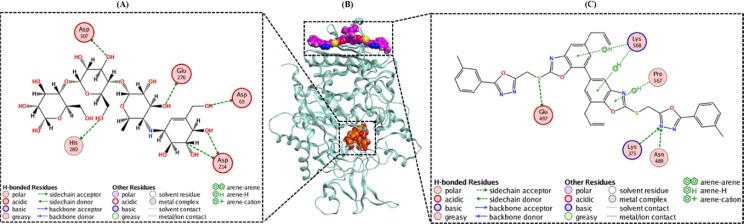

Furthermore, to explore the possible interaction mode of the potent compound 7l with α-glucosidase, molecular docking studies were conducted based on previous reports.28, 29 As shown in Fig. 3 B, the binding site of 7l to α-glucosidase is significantly different from that of acarbose to α-glucosidase. The former is bound to the top domain of the enzyme, while the latter is bound to the middle domain of the enzyme. This result was consistent with 7l being a noncompetitive inhibitor as demonstrated in the enzyme kinetic test. In addition, as displayed in the 2D bonding patterns of 7l and acarbose to α-glucosidase (Fig. 3A and 3C), it can be found that the sulfur atom of 7l interacted with residue Glu497 through a hydrogen bond; The nitrogen atom of 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring of 7l formed interactions with residues Lys373 and Asn489 through hydrogen bonds; Two phenyl rings of the skeleton of 7l had π-π stacking interactions with residue Lys568. While acarbose is bound to α-glucosidase mainly through hydrogen bonds with its residues Asp307, Glu276, Asp69, Asp214, and His280.

Fig. 3.

Binding results of compounds 7l and acarbose in the active sites of α-glucosidase (PDB: 3AXH). (A): 2D binding model of 7l with α-glucosidase; (B): 3D binding models of 7l and acarbose with α-glucosidase; (C): 2D binding model of acarbose with α-glucosidase.

2.4. Antiviral activities of honokiol thioethers against SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entry

A model of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped viruses carrying a reporter of luciferase to infect HEK-293 T-ACE2h cells was first constructed according to the previous reports.30, 31, 32 The control was cells only infected with SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudovirus, whose luciferase luminescence value was defined as 100%. Evans blue was served as a positive inhibitor for viral entry. As displayed in Table 2 , the toxicities of honokiol thioethers to the host HEK-293 T-ACE2h cells were well improved after optimizing the structure of honokiol, and their maximum nontoxic concentration (CC0 > 100 μM) values were all greater than that of the precursor honokiol (CC0 = 50.0 μM). Moreover, among these honokiol thioethers, compounds 7e, 9a, 9e, and 9r exhibited potent antiviral effect on SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entering HEK-293 T-ACE2h. Especially 9a displayed the strongest inhibition of pseudovirus entry with an IC50 value of 16.96 ± 2.45 μM, which was lower than the positive control Evans blue (21.98 ± 1.98 μM). Furthermore, it can be visualized from Fig. S1 that the inhibitory effect against pseudovirus entry of Evans blue, 9a, and 9r was in a concentration-dependent manner. Compound 9a almost completely inhibited SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entry at 100 μM and did not exhibit any toxicity to the host cells. The above results indicated that 9a could be a prospective candidate as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 virus entry.

Table 2.

IC50 values of honokiol thioethers against the entry of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudovirus into HEK-293 T-ACE2h cells.

| Compound | Substituent R | CC0 (µM) for 4 h | IC50 (µM) against pseudovirus entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | –Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7b | –(2-F)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7c | –(3-F)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7d | –(4-F)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7e | –(2-Cl)Ph | >100 | 84.35 ± 5.58 |

| 7f | –(3-Cl)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7g | –(4-Cl)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7h | –(2-Br)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7i | –(3-Br)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7j | –(4-Br)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7k | –(2-CH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7l | –(3-CH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7m | –(4-CH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7n | –(2-OCH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7o | –(3-OCH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 7p | –(4-OCH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 9a | -Ph | >100 | 16.96 ± 2.45 |

| 9b | –(2-F)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 9e | –(2-Cl)Ph | >100 | 85.18 ± 12.76 |

| 9k | –(2-CH3)Ph | >100 | >100 |

| 9r | 3-pyridyl | >100 | 45.61 ± 4.66 |

| honokiol | / | 50.00 | >50 |

| Evans blue | / | >100 | 21.98 ± 1.98 |

2.5. Honokiol thioethers 9a and 9r bind and interact with SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor

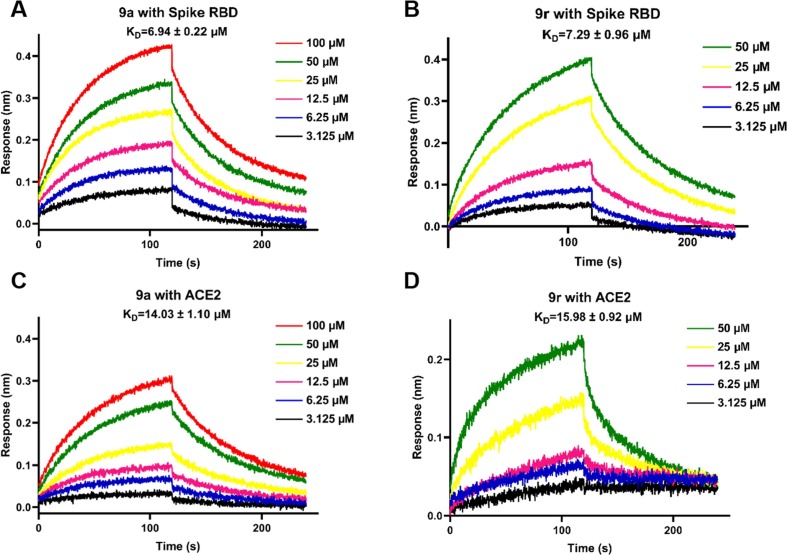

As we know, SARS-CoV-2 can use ACE2 receptor on the surface of human cells to invade cells and thus achieve infection.33 To further investigate the inhibition mode of these honokiol thioethers, we evaluated the binding behaviors of two potent compounds 9a and 9r in combination with both SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2 by biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding and docking assays. As displayed in Fig. 4 , the binding ability of 9a and 9r with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2 was in a dose-dependent manner. Further based on the data in Table 3 , it was evident that both derivatives 9a and 9r bound more strongly to SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD with equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values of 6.94 ± 0.22 and 7.29 ± 0.96 μM, respectively, compared with honokiol. Similarly, 9a and 9r also had the slightly stronger binding ability to ACE2 protein than honokiol (KD = 16.98 ± 3.4 μM), and their KD values were 14.03 ± 1.10 and 15.98 ± 0.92 μM, respectively. Moreover, the binding energy values of 9a and 9r with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD (9a: –33.7192 kcal/mol; 9r: –32.4406 kcal/mol) and human ACE2 (9a: –42.3154 kcal/mol; 9r: –34.6448 kcal/mol) obtained by molecular docking studies were consistent with the BLI assay results described above (Table 3). In addition, the binding ability of 9a with both SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and ACE2 was slightly stronger than that of 9r.

Fig. 4.

Binding curves of 9a and 9r with human ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD proteins by BLI binding kinetics assay. (A) and (B): Compounds 9a and 9r binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD protein, respectively; (C) and (D): The interaction of 9a and 9r binding to human ACE2 protein, respectively.

Table 3.

Equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values of 9a and 9r with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2 protein by a BLI binding assay, and their binding energy by molecular docking studies.

| compound | KD values (µM) by BLI |

binding energy (kcal/mol) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| spike RBD | human ACE2 | spike RBD | human ACE2 | |

| 9a | 6.94 ± 0.22 | 14.03 ± 1.10 | –33.7192 | –42.3154 |

| 9r | 7.29 ± 0.96 | 15.98 ± 0.92 | –32.4406 | –34.6448 |

| honokiol | 25.01 ± 7.29 | 16.98 ± 3.4 | –24.304 | −31.963 |

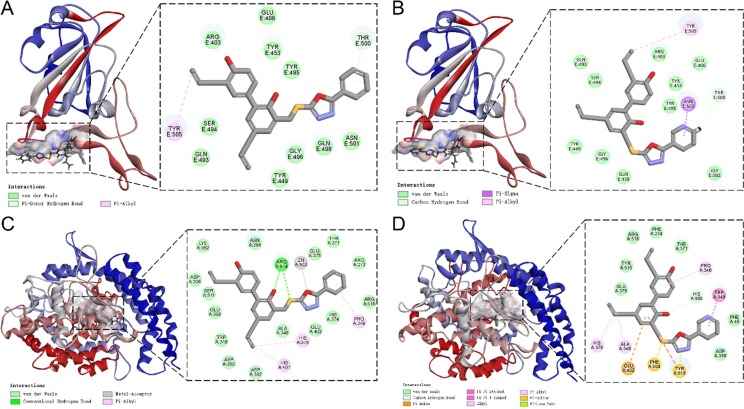

Furthermore, details of the interaction of compounds 9a and 9r with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2 can be obtained in Fig. 5 A-D. Compounds 9a and 9r interacted with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD mainly via residues Tyr505 and Asn501 (Fig. 5A and B); The interaction of 9a with human ACE2 was stronger than that of 9r, mainly via hydrogen bonds with a key residue Arg514 (Fig. 5C and D). Taken together, these findings indicated that 9a and 9r may effectively block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the host ACE2 receptor through dual recognition of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2.

Fig. 5.

Docking results of compounds 9a and 9r in the active sites of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD (PDB: 6M0J) and human ACE2 proteins (PDB: 3AXH). (A) and (B) Predicted interactions of compounds 9a and 9r with SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD, respectively. (C) and (D) Predicted interactions of compounds 9a and 9r with human ACE2 protein, respectively.

2.6. Cytotoxicity against normal cells (LO2)

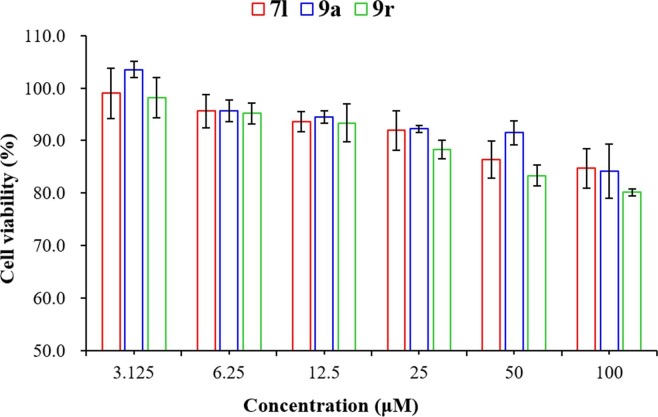

The potent compounds 7l, 9a, and 9r were selected for cytotoxicity assay to investigate their toxic effects on normal mammalian cells using the MTT assay.24 As displayed in Fig. 6 , the viability of normal cells (LO2) did not change much after treatment with different concentrations of 7l, 9a, and 9r, the survival rates were all above 80% even at the 100 µM level. The result revealed that these honokiol thioethers exhibited relatively no cytotoxicity toward normal cells (LO2).

Fig. 6.

Cell viability of LO2 cells after treatment by 7l, 9a, and 9r. The results are presented as the mean ± SD.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, two series of honokiol thioethers bearing 1,3,4-oxadiazole fragments (7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r) were prepared and evaluated for their α-glucosidase and SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitory activities. Among these honokiol thioethers, compound 7l displayed the strongest α-glucosidase inhibitory effect with an IC50 value of 18.9 ± 2.3 µM, which was more potent than the reference drug acarbose (IC50 = 24.4 ± 0.3 µM). Some interesting SARs were also observed. Enzyme kinetic study manifested that 7l was a noncompetitive α-glucosidase inhibitor, which was further supported by the molecular docking results. The binding site of 7l to α-glucosidase was significantly different from that of acarbose to α-glucosidase. Moreover, honokiol thioethers 7e, 9a, 9e, and 9r exhibited potent antiviral effects on SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entering into HEK-293 T-ACE2h. Especially 9a displayed the strongest inhibitory activity against pseudovirus entry with an IC50 value of 16.96 ± 2.45 μM, which was lower than the positive control Evans blue (21.98 ± 1.98 μM). BLI binding and docking studies suggested that 9a and 9r may effectively block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the host ACE2 receptor through dual recognition of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2. Additionally, the potent honokiol thioethers 7l, 9a, and 9r displayed relatively no cytotoxicity to normal cells (LO2). These findings will offer some insights into the discovery of honokiol derivatives as potential both α-glucosidase and SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Chemicals and instrument

Honokiol was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD. The α-glucosidase enzyme and p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside (PNPG) were obtained from Beijing Solarbio Inc. All other reagents were obtained from commercial sources. A melting-point instrument was used to measure the melting points (m.p.) for all the target honokiol. Infrared spectra (IR) were detected by a PE-1710 FT-IR spectrometer (Waltham, USA). 1H/13C NMR spectra of all the target honokiol thioethers were measured by a 400 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer. HRMS spectra of all the honokiol thioethers were determined using a Thermo Fisher LTQFT Ultra instrument.

4.2. Preparation of 5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiols (4a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, r) and 2-chloromethyl-5-substituted phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles (6a–p)

The 5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiols and 2-chloromethyl-5-substituted phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles were prepared according to previously reported methods.25 In brief, 98% H2SO4 (0.2 mL) was added to the solution of various aromatic acids a–r (10 mmol) in EtOH (15 mL), and then refluxed overnight. The mixture was concentrated once the reaction was finished, and the residue was purified to give the corresponding esters 2a–r. Following that, esters 2a–r were reacted with NH2NH2·H2O to yield aryl hydrazides 3a–r, which were then cyclized with carbon disulfide, potassium hydroxide (KOH), and 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl) to yield 5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiols (4a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, r). Additionally, the aryl hydrazides 3a–p were treated with chloroacetyl chloride (10 mmol) to yield compounds 5a–p via another approach. Finally, the 2-chloromethyl-5-substituted phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles (6a–p) are obtained by treating 5a–p with POCl3.

4.3. Synthesis of honokiol thioethers 7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r

The synthesis of intermediates 2 – 8 was carried out according to the previous reports.34, 35 The corresponding intermediates 1,3,4-oxadiazoles (6a–p, 4a, c, e, g, j, k–m, o, q, r) (0.25 mmol), K2CO3 (0.5 mmol, 69.1 mg), and KI (0.02 mmol, 3.3 mg) were added to a solution of the intermediate 4/8 (0.2 mmol) in acetone. The reaction mixture was filtrated and then the filtrate was concentrated in vacuum, when the reaction was completed. Then the concentrate was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography (PTLC), yielding the honokiol thioethers 7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r. Spectral data of honokiol thioethers 7a–d are listed below, and others are listed in Supplementary Material.

Data for 5′,7-diallyl-2,2′-bis(((5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-5,7′-bibenzo[d]oxazole (7a): White solid, yield: 70%, m.p. 122–125℃; IR cm−1(KBr): 2978, 2931, 1550, 1504,1147, 1115, 707, 688,1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3) δ: 7.92–7.99 (m, 5H, -Ph), 7.44–7.53 (m, 8H, -Ph), 7.29 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 5.99–6.08 (m, 2H, –CH = CH2), 5.11–5.19 (m, 4H, –CH2 = CH), 4.84 (s, 2H, –CH 2-N), 4.82 (s, 2H, –CH 2 -N), 3.67 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH = CH2), 3.54 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH = CH2,13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3) δ: 165.75, 162.46, 162.42, 162.32, 150.91, 148.46, 142.64, 142.04, 137.47, 137.21, 134.85, 132.30, 132.02, 131.97, 129.10, 129.05, 127.02, 126.99, 125.14, 124.57, 124.08, 123.45, 123.36, 117.73, 117.06, 116.61, 116.35, 40.19, 34.05, 25.86; HRMS: calcd for C38H29N6O4S2 ([M + H]+) 697.1691, found 697.1684, error value: 1.0 ppm.

Data for 5′,7-diallyl-2,2′-(((5-(2-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-2-(((5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-5,7′-bibenzo[d]oxazole (7b): Yellow solid, yield: 40%, m.p. 58–61℃; IR cm−1(KBr): 2921, 1504, 1494, 1147, 1114, 668,1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3) δ: 7.95–8.03 (m, 2H, -Ph), 7.91 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.50–7.52 (m, 3H, -Ph), 7.44 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.28–7.29 (m, 2H, -Ph), 7.17–7.24 (m, 3H, -Ph), 5.99–6.08 (m, 2H, –CH = CH2), 5.11–5.19 (m, 4H, –CH2 = CH), 4.86 (s, 2H, –CH 2-N), 4.83 (s, 2H, –CH 2 -N), 3.67 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH = CH2), 3.53 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H,–CH 2-CH = CH2,13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3) δ: 162.82, 162.51, 162.21, 160.04 (d, JCF = 257.0 Hz), 150.89, 148.45, 142.62, 142.02, 137.40, 137.22, 134.87, 133.85, 133.79, 133.70, 132.27, 129.80, 125.11, 124.67, 124.54, 124.06, 123.30, 117.71, 117.14, 117.02 (d, JCCF = 17.0 Hz), 117.01, 116.46 (d, JCCF = 28.0 Hz), 112.04, 111.93, 40.18, 34.04, 25.79; HRMS: calcd for C38H27F2N6O4S2 ([M + H]+) 733.1503, found 733.1501, error value: 0.3 ppm.

Data for 5′,7-diallyl-2,2′-(((5-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-2-(((5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-5,7′-bibenzo[d]oxazole (7c): Yellow solid, yield: 68%, m.p. 133–135℃; IR cm−1(KBr): 2925, 1508, 1493, 1149, 1117, 869,1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3) δ: 7.92 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.75–7.81 (m, 2H, -Ph), 7.64–7.72 (m, 2H, -Ph), 7.52 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.40–7.48 (m, 3H, -Ph), 7.30 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.19–7.22 (m, 2H, -Ph), 5.99–6.08 (m, 2H, –CH = CH2), 5.11–5.20 (m, 4H, –CH2 = CH), 4.84 (s, 2H, –CH 2-N), 4.81 (s, 2H, –CH 2 -N), 3.67 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH=CH2), 3.54 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH=CH2,13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3) δ: 164.74, 163.11 (d, JCF = 187.0 Hz), 162.82, 162.76, 162.52, 150.91, 148.46, 142.59, 141.99, 137.51, 137.17, 134.82, 132.30, 131.01, 130.95, 130.87, 125.35, 125.26, 125.16, 124.62, 124.05, 123.36, 122.77, 119.16, 119.12 (d, JCCF = 21.0 Hz), 118.95, 117.74, 117.07, 116.61 (d, JCCF = 25.0 Hz), 114.19, 114.16, 113.95, 40.18, 34.05, 25.82; HRMS: calcd for C38H27F2N6O4S2 ([M + H]+) 733.1503, found 733.1500, error value: 0.4 ppm.

Data for 5′,7-diallyl-2,2′-(((5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-2-(((5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methyl)thio)-5,7′-bibenzo[d]oxazole (7d): White solid, yield: 72%, m.p. 104–106℃; IR cm− 1(KBr): 2923, 1609, 1498, 1236, 1148, 1115, 844,1H NMR (400 MHz CDCl3) δ: 7.92–8.02 (m, 5H, -Ph), 7.52 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.44 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.29 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, -Ph), 7.12–7.18 (m, 4H, -Ph), 5.99–6.08 (m, 2H, –CH=CH2), 5.12–5.20 (m, 4H, –CH2=CH), 4.83 (s, 2H, –CH 2-N), 4.81 (s, 2H, –CH 2 -N), 3.67 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH=CH2), 3.54 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, –CH 2-CH=CH2,13C NMR (100 MHz CDCl3) δ: 166.15, 163.77 (d, JCF = 187.0 Hz), 162.48, 162.43, 162.27, 150.90, 148.45, 142.61, 142.01, 137.49, 137.17, 134.81, 132.28, 129.38, 129.35, 129.29, 129.26, 125.12, 124.56, 124.03, 123.38, 119.80, 119.77, 117.73, 117.07, 116.47 (d, JCCF = 22.0 Hz), 116.42 (d, JCCF = 22.0 Hz), 40.18, 34.05, 25.84; HRMS: calcd for C38H27F2N6O4S2 ([M + H]+) 733.1503, found 733.1495, error value: 1.1 ppm.

4.4. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity

All the honokiol thioethers were evaluated for their in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activities by using PNPG as a substrate according to the reported methods.28 In brief, the tested compounds were dissolved by DMSO and PBS buffer in a series of concentrations. After adding the compounds and α-glucosidase solutions (1.0 U/mL in PBS) to a 96-well plate, it was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, 1 mM of PNPG was placed in each well, and then the mixture was incubated for 10 min. Finally, the OD values at 405 nm of each well was determined by a microplate reader. The blank control (CK) group was only PBS buffer. The control group employed PBS to replace the solution of tested honokiol derivatives. PBS buffer was used instead of α-glucosidase solution as the blank sample group. The α-glucosidase inhibitory rate% = [(ODcontrol–ODCK) – (ODsample –OD blank sample]/ (ODcontrol–ODCK). The IC50 values of all the title honokiol thioethers were obtained by SPSS 21.0 software. Each experiment was repeated three times.

4.5. Kinetic study

In order to investigate the inhibition mechanism of compound 7l, kinetic studies were carried out as the method of previous reports.27, 28 A solution of α-glucosidase at 1.0 U/mL was incubated with 7l for 15 min at 30 °C. A microplate reader was utilized to determine OD values every 5 min for 30 min, before adding a range of PNPG concentrations to the above mixture. The type of inhibition and Km values of 7l were analyzed using Lineweaver-Burk plots. The Dixon plot method was used to afford Ki value for 7l.

4.6. Molecular docking study

Discovery Studio 4.5 was used to carried out the molecular docking studies on the structures of oligo-1,6-glucosidase (PDB: 3AXH), SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD (PDB ID: 6M0J), and human ACE2 bound with its inhibitor (PDB ID:1R4L). The structures of compounds 7l, 9a, 9r, and ligands were built and optimized by ChemBioDraw Ultra and Gaussian software, respectively. The bind modes were based on the previously reported methods and conducted by the Discovery Studio 4.5.28, 29

4.7. Biolayer interferometry binding

All BLI assays were conducted on an Octet system to investigate the affinities of compounds with the proteins of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2. Human ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD sensors were constructed by nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) biosensors (Fortebio, USA) and recombinant His-tag human ACE2 or recombinant His-tag SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD, respectively. Compounds stock solution (10 mM in DMSO) were diluted to the different concentrations by PBS buffer. An assay cycle consists of equilibrium incubation in PBS for 10 min, baseline incubation in PBS for 120 s, followed by associating in compound solution for 120 s, and then dissociation in PBS for 120 s. Both protein-coated and blank biosensors were immersed into wells with serial dilutions of the samples. The experiments were carried out at 30 °C. The binding curves were subtracted from empty biosensors and PBS controls by selecting the “Double Reference” model. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was calculated using a 1:1 binding model by Data Analysis Software 9.0.

4.8. Inhibition of honokiol derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entering into HEK-293 T-ACE2h

The pseudovirus assay was carried out as previously described.30 Briefly, HEK-293 T-ACE2h cells in 96-well plates were incubated with the tested compound that contained DMEM medium (100 μL) for 2 h. Each well was inoculated with pseudovirus (30 μL), medium (20 μL), and a two-fold concentration of drugs (50 μL) and incubated for additional 2 h at 37 °C. The inoculum was withdrawn after roughly 2 h of incubation, and the cells were coated with fresh DMEM (100 μL). The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h before being agitated for 10 min with cell lysate buffer (100 μL). The cell lysate was then transferred to an opaque 96-well white solid plate with luminescence solution (100 μL), which was used to measure luciferase luminescence using a microplate reader at 578 nm. The IC50 values of inhibition pseudovirus entry the host cells by honokiol derivatives were calculated by SPSS 21.0 software.

4.9. Cytotoxicity studies against LO2 cells

Cytotoxicities of compounds 7l, 9a, and 9r towards normal cells (LO2) were tested using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as previous report.24

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ting Xu: Data curation, Methodology. Jie-Ru Meng: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Wanqing Cheng: Data curation. Jia-Zheng Liu: Methodology, Software. Junyan Chu: Data curation. Qian Zhang: Methodology. Nannan Ma: Software. Li-Ping Bai: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. Yong Guo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Natural Science Foundation of Henan province, China (No. 222300420524) for financial assistance. The authors also thank the financial support by The Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR (File no. 0065/2020/A2, 0004/2019/A1 and 0043/2020/AGJ), Emergency Key Program of Guangzhou Laboratory (Grant No. EKPG21-06) and the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province for the support of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Joint Laboratory of Respiratory Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

Supporting materials includes spectral data of all target compounds 7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r; detailed procedures of synthesis of intermediates 2–8, cell culture, cell viability assay, construction of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudoviruses model, spectral data for compounds 7d–p, 9a–c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r, and copies of spectra of compounds 7a–p, 9a, c, e, g, j–m, o, q, and 9r. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116838.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Alonso-Castro A.J., Zapata-Bustos R., Domínguez F., García-Carrancá A., Salazar-Olivo L.A. Magnolia dealbata Zucc and its active principles honokiol and magnolol stimulate glucose uptake in murine and human adipocytes using the insulin-signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amblard F., Delinsky D., Arbiser J.L., Schinazi R.F. Facile purification of honokiol and its antiviral and cytotoxic properties. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3426–3427. doi: 10.1021/jm060268m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharate S.S., Mignani S., Vishwakarma R.A. Why are the majority of active compounds in the CNS domain natural products? A critical analysis. J Med Chem. 2018;61:10345–10374. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabral C., Efferth T., Pires I.M., Severino P., Lemos M.F.L. Natural products as a source for new leads in cancer research and treatment. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern Med. 2018:1–2. doi: 10.1155/2018/8243680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey A.L., Edrada-Ebel R., Quinn R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:111–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen C.Y., Jiang J.G., Yang L., Wang D.W., Zhu W. Anti-ageing active ingredients from herbs and nutraceuticals used in traditional Chinese medicine: pharmacological mechanisms and implications for drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:1395–1425. doi: 10.1111/bph.13631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leeman-Neill R.J., Cai Q., Joyce S.C., et al. Honokiol inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor signaling and enhances the antitumor effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2571–2579. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liou K.-T., Shen Y.-C., Chen C.-F., Tsao C.-M., Tsai S.-K. The anti-inflammatory effect of honokiol on neutrophils: mechanisms in the inhibition of reactive oxygen species production. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;475:19–27. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)02121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L., Chen J., Wang X., et al. Structural modification of honokiol, a biphenyl occurring in magnolia officinalis: the evaluation of honokiol analogues as inhibitors of angiogenesis and for their cytotoxicity and structure–activity relationship. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6469–6481. doi: 10.1021/jm200830u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ong C.P., Lee W.L., Tang Y.Q., Yap W.H. Honokiol: A review of its anticancer potential and mechanisms. Cancers. 2019;12:48. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park E.-J., Min H.-Y., Chung H.-J., et al. Down-regulation of c-Src/EGFR-mediated signaling activation is involved in the honokiol-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauf A., Olatunde A., Imran M., et al. Honokiol: A review of its pharmacological potential and therapeutic insights. Phytomedicine. 2021;90:153647. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J., Chen L.J., Liu L., et al. Liposomal honokiol, a potent anti-angiogenesis agent, in combination with radiotherapy produces a synergistic antitumor efficacy without increasing toxicity. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:617–628. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi X., Zhang T., Lou H., Song H., Li C., Fan P. Anticancer effects of honokiol via mitochondrial dysfunction are strongly enhanced by the mitochondria-targeting carrier berberine. J Med Chem. 2020;63:11786–11800. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mottaghi S., Abbaszadeh H. Natural lignans honokiol and magnolol as potential anticarcinogenic and anticancer agents. A comprehensive mechanistic review. Nutr. Cancer. 2021:1–18. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2021.1931364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S., Li L., Tan L., Liang X. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus-1 replication by natural compound honokiol. Virol Sin. 2019;34:315–323. doi: 10.1007/s12250-019-00104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijesuriya Y.K., Lappas M. Potent anti-inflammatory effects of honokiol in human fetal membranes and myometrium. Phytomedicine. 2018;49:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X., Li Y., Yang Q., Cai H., Wang L., Zhao X. Improving the antioxidant activity of natural antioxidant honokiol by introducing the amino group. J Mol Model. 2021;27:1–10. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Angelis M., Della-Morte D., Buttinelli G., et al. Protective role of combined polyphenols and micronutrients against influenza a virus and SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1721. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9111721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panigrahi G.K., Sahoo S.K., Sahoo A., et al. Bioactive molecules from plants: A prospective approach to combat SARS-CoV-2. Adv Tradit Med. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13596-021-00599-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanikawa T., Hayashi T., Suzuki R., Kitamura M., Inoue Y. Inhibitory effect of honokiol on furin-like activity and SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Tradit Complementary Med. 2022;12:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Y., Hou E., Wen T., et al. Development of membrane-active honokiol/magnolol amphiphiles as potent antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J Med Chem. 2021;64:12903–12916. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu T., Tian W., Zhang Q., et al. Novel 1,3,4-thiadiazole/oxadiazole-linked honokiol derivatives suppress cancer via inducing PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent autophagy. Bioorg Chem. 2021;115:105257. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Y., Xu T., Bao C., et al. Design and synthesis of new norfloxacin-1,3,4-oxadiazole hybrids as antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;136:104966. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.104966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang R., Han M., Fan J., et al. Development of novel (+)-nootkatone thioethers containing 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole/thiadiazole moieties as insecticide candidates against three species of insect pests. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:15544–15553. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c05853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X.Q., Mou X.F., Mao N., et al. Design, semisynthesis, α-glucosidase inhibitory, cytotoxic, and antibacterial activities of p-terphenyl derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;146:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y., Hou E., Ma N., Liu Z., Fan J., Yang R. Discovery, biological evaluation and docking studies of novel N-acyl-2-aminothiazoles fused (+)-nootkatone from Citrus paradisi Macf. as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:104294. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye G.J., Lan T., Huang Z.X., et al. Design and synthesis of novel xanthone-triazole derivatives as potential antidiabetic agents: α-glucosidase inhibition and glucose uptake promotion. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;177:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y., Meng J.R., Liu J.Z., et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of honokiol derivatives bearing 3-((5-phenyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-yl) methyl) oxazol-2(3H)-ones as potential viral entry inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:885. doi: 10.3390/ph14090885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodon J., Muñoz-Basagoiti J., Perez-Zsolt D., et al. Identification of plitidepsin as potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2-induced cytopathic effect after a drug repurposing screen. Front Pharm. 2021;12:278. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.646676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nie J., Li Q., Wu J., et al. Establishment and validation of a pseudovirus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:680–686. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1743767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh M., Bansal V., Feschotte C. A single-cell RNA expression map of human coronavirus entry factors. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108175. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu B., Fu S.H., Tang H., et al. Design, synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of honokiol derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rynearson K.D., Charrette B., Gabriel C., et al. 2-Aminobenzoxazole ligands of the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:3521–3525. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.05.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.