Abstract

This work aims to develop a photoelectrochemical (PEC) platform for detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike glyprotein S1. The PEC platform is based on the modification of a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) coated glass slide with strontium titanate (SrTiO3 or ST), sulfur-doped carbon nitride (g–C3N4–S or CNS) and palladium nanoparticles entrapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix (PdAlO(OH) or PdNPs). The PEC platform was denoted as PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO and it was characterized by SEM, TEM, FTIR, DRX, and EIS. The PEC response of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform was optimized by evaluating the effects of the concentration of the donor molecule, the nature of the buffer, pH, antibody concentration, potential applied to the working electrode, and incubation time. The optimized PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC platform was modified with 5 μg mL−1 of antibody for determination of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1. A decrease in the photocurrent was observed with an increase in the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 from 1 fg mL−1 to 1000 pg mL−1 showing that the platform is a promising alternative for the detection of S1 protein from SARS-CoV-2. The designed PEC platform exhibited recovery percentages of 96.20% and 109.65% in artificial saliva samples.

Keywords: SARS CoV-2, Photoelectrochemical platform, SrTiO3, Palladium nanoparticles, g-C3N4-S

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for the COVID-19, which was announced as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 due to millions of cases confirmed globally (Word Health Organization, 2020). Nowadays, COVID-19 has become a huge public health issue that has infected more than 271 million and killed more than 5.3 million people worldwide (Word Health Organization, 2021). The fifth wave of COVID-19 caused by the emergence of the omicron variant, which is characterized by deletions and more than 30 mutations, brought greater transmissibility, higher viral binding affinity and immune escape. In addition, there are still uncertainties regarding the behavior of this variant, including in relation to vaccine-mediated immunity (Karim and Karim, 2021). Therefore, the development of devices to confirm/detect quickly and in a reliable form the infection by SARS-CoV-2 virus is of high importance nowadays since the early and fast diagnosis of infected patients can delay the spread of this infectious disease (Yakoh et al., 2021; Morales-Narvaez and Dincer, 2020). In this sense, there has been proposed a number of methods for the detection of the corona virus based on several different strategies including detection the viral nucleic acids during acute infection (Chu et al., 2020), methods based on artificial intelligence (Pirouz et al., 2020), serological assay (Amanat et al., 2020), and sensors (Kumar et al., 2022).

In addition, there are many reliable, robust and well-established commercially available methods based on different operational principles for the SARS-CoV-2 detection including those based on quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and conventional lateral flow immunoassays. The RT-PCR has been presented as the gold standard method for the COVID-19 diagnosis and it can be performed by minimally invasive sampling procedures, however, has been related some difficulties in the use of the RT-PCR including false-negative rate range up to 37% (Mehmandoust et al., 2022). The ELISA is a simple and safe assay for serum and plasma samples from infected patients and it involves multiple liquid handling steps. The conventional lateral flow immunoassays (LFIA) are quick, reliable and low cost tests based on the application of a drop of sample on an immunochromatographic stick; however, the conventional lateral flow immunoassays present limitations in quantitative and sensitive analyses of SARS-CoV-2 detection (Li, and Lillehoj, 2021; Oliveira et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2021). Therefore, a specific, reliable, easy to use, simple, fast, and portable method for the quantitative and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 is a feasible alternative to commercially applied methods.

In this context, the photoelectrochemical methods stand out as a promising approach for the development of sensors for immunodiagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers. It has attracted growing interest in bioanalysis since the excitation (light) and detection (current) signals are of different nature, such as this technique can operate with low background signal contributing for a high sensitivity (Zhang et al., 2019).

An essencial issue for the establishment of an efficient photoelectrochemical sensor is the choice of the material exploited in the development of the photoelectroactive platform, since it determines the efficiency of photogenerated charges lifetime and the intensity of the photocurrent (Zhang et al., 2019).

The semiconductors are among the most exploited materials in development of photoelectrochemical sensors, since these materials can absorbs light from an incident radiation source to produce electron/hole couples and generate photocurrent (Bard, 2001). Due to the capability of the semiconductors in conversion of photon-to-current, they are widely used for construction of detectors for photoelectrochemical systems and photocatalytic applications. In addition, it is also possible to improve the conversion efficiency of the semiconductors through the interaction of these materials with sensitizing species and/or by combining two or more photoactive materials.

Semiconductors based on ceramic materials have received high attention in the development of devices based on photo-to-electron conversion (Rozhansky and Zakheim, 2005) due to its exquisites properties including ferroelectricity, piezoelectricity, electro-optical, magneto-optical properties, good chemical resistance, resistance to use in high temperatures etc. (Magalhães et al., 2017). Among the ceramic based materials, perovskites, such as strontium titanate (SrTiO3) presents very interesting characteristics to development of sensors such as high chemical and thermal stability (Yang et al., 2020). However, SrTiO3 presents a high band gap such as it presents low capability to produce electron/holes pairs under incidence of visible light.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has attracted considerable attention, especially in the recent years, in the fields of photocatalysis, photoelectrochemistry, and electrochemistry owing to its ability to be doped and its tunable structure, photocatalytic and photoelectronic properties (Sagara et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017). However, the undoped g-C3N4 can does not exhibit a photocatalytic performance as good as expected owing to fast recombination of photoinduced charge carriers (Niu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2017). In order to solve this problem, several strategies has been proposed (Chai et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020), including the doping with metal and/or non-metal chemical elements which has showed to be one of the most effective methods to improve the electronic structure and photoelectrochemical properties of the g-C3N4. In this sense, several non-metal dopants have been investigated, including sulfur (Wang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). The doping of g-C3N4 by sulfur has indicated that the dopant can play a significant role in tuning the electronic structure, reducing the band gap, broadening the light responsive region, assisting the separation of photo-generated charge carriers, thus creating more active sites on g-C3N4 (Jiang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019).

Palladium is highly exploited in electrocatalysis of a number of species (Li et al., 2005; Tronto et al., 2006; Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2008) and it is highly exploited as nanoparticles supported on several materials in order to obtain palladium-supported nanoparticles of high stability and high surface-to-volume ratio (Choudary et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2008; Gniewek et al., 2008). In addition, palladium nanoparticles based materials has been exploited in catalytic and electrocatalytic reactions of manys species (Trzeciak and Augustyniak, 2019; Xu et al., 2022). The proposed PEC immunosensor exploits ascorbic acid as donor molecule. Thus, Pd nanoparticles were employed in order to improve the electrochemical oxidation of the donor molecule (Wu et al., 2012).

In this context, the present work exploits the use of SrTiO3 combined to sulfur dopped g-C3N4 and nanoparticles of palladium supported in aluminum hydroxide as a photoelectrochemical platform for detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and solutions

All chemicals were of analytical grade and they were used without further purification steps. Strontium titanate (SrTiO3), palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix (Pd/AlO(OH)), 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-yl] sulfonic ethane (HEPES), chitosan (1%), glutaraldehyde (5%), bovine albumin (BSA) (1%), and thiourea (CH4N2S) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 antibody (Ab273074) and SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 (Ab272105) were purchased from abcam, USA. These proteins were denoted as anti-SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2, respectively. Monobasic sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4.H2O), acetic acid (CH3COOH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ascorbic acid (C6H8O6 or AA), and boric acid (H3BO3) were purchased from Isofar - Indústria e Comércio de Produtos Químicos Ltda, Brazil. Ethanol was purchased from Merck - Brazil. All working solutions were prepared with water purified in an OS100LXE system from GEHAKA Company.

2.2. Preparation of sulfur-doped carbon nitride and construction of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC platform

Sulfur-doped carbon nitride (g–C3N4–S or CNS) was synthesized using thiourea (H2NCSNH2) as precursor under high temperature heating conditions using a muffle, according to (Guan et al., 2021). Firstly, a certain amount of the percussor was weighed, taken to the muffle, keeping the temperature at 550°C for 2 h, then the material was cooled to room temperature. A yellow g–C3N4–S (CNS) product obtained was ground to a fine powder with aid of a mortar and pistle.

For the construction of the PEC platform, 3 mg of SrTiO3 (ST), 1 mg of CNS and 3 mg of Pd/AlO(OH) (represented as PdNPs) were weighed for dispersion in 20 μL of deionized water for further mixing and homogenization. Then 20 μL of this dispersion was removed to be placed directly on the surface of the FTO electrode, which was dried at room temperature and then taken to the heating plate at a temperature of 350°C for 30 min, thus forming a film of the composite material PdNPs/CNS/ST on the FTO surface.

Then, a stock solution of SARS-CoV-2 antibody was prepared at a concentration of 10 μg mL−1 with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) from which SARS-CoV-2 antibody solutions were prepared at concentrations: 1, 2.5 and 5 μg mL−1.

For the modification of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform with SARS CoV-2 antibody, 15 μL of chitosan (1% m/v) and 15 μL of glutaraldehyde (5% m/v) were mixed. From this solution an aliquot of 10 μL was removed and mixed with 10 μL of the SARS-CoV antibody solution. Then, 10 μL of this last solution was added to the surface of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform and the platform modified with SARS-CoV-2 antibody was left to dry for 30 min. After this step, 10 μL of BSA (0.5% m/v) was added to the antibody-modified platform, which was allowed to dry for 10 min, and washed with deionized water to remove weakly adsorbed species, obtaining the anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunosensor (anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO). Finally, the study of the SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2 interaction was performed by incubating the surface of the immunosensor with 10 μL of SARS-CoV-2 solutions for 30 min. Then, the amperograms were recorded by applying a potential of 0.0 V vs Ag/AgCl(Sat. KCl).

2.3. Characterization of the materials used to build the PEC platform

The SEM measurements were carried out in a Scanning Electron Microscope - FEI Quanta 200 FEG and TEM measurements were performed on a Tecnai G2-20 Transmission Electron Microscope - FEI SuperTwin 200 kV.

FT-IR measurements were performed to identify the functional groups of the materials exploited to construct the PEC platform. For this purpose, a KBr pellet was prepared mixing KBr powder to the compounds to be analyzed (1 wt%). The mixtures were pressed in specific molds with a pressure of 10–15 kpsi, thus forming a disc. In order to obtain the FTIR spectra, a Shimadzu spectrophotometer, IR model Prestige-21 was used in the spectral range from 4000 to 400 cm−1. The crystal structure of the materials were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) device using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer, with a CuKα radiation tube operating at 40 kV/40 mA. XRD measurements were performed with a 2θ in the range of 10°–90°, with a step size of 0.02° and counting time of 0.5 s.

2.4. Electrochemical and photoelectrochemystry measurements

The electrochemical and photoelectrochemical measurements (PEC) were performed with an Autolab potentiostat/galvanostat model PGSTAT 128N from Metrohm-Autolab coupled to a Nova 2.1 software. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were also performed with an Autolab potentiostat/galvanostat model PGSTAT 128N from Metrohm-Autolab equipped with a frequency response analyser (FRA 2) in a frequency ranging from 105 Hz to 0.1 Hz. In both cases, a three-electrode conventional cell composed of a working electrode (FTO - Fluorine-Doped Tin Oxide), an Ag/AgCl electrode as reference electrode and a gold electrode as auxiliary electrode. The PEC measurements were performed with a commercial lamp of 30 W as light source attached to a homemade dark box.

2.5. Preparation and analysis of saliva samples

In order to evaluate the applicability of the immunosensor were performed analysis of artificial saliva samples acquired at a local drugstore. The detection of the SARS-CoV-2 was performed with the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform by using the external calibration method.

The samples were prepared containing different concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 (1 fg mL−1, 10 fg mL−1, 100 fg mL−1, 1 pg mL−1, 10 pg mL−1 and 100 pg mL−1) and then the immunosensor (anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO) was incubated with 10 μL of each sample for 30 min. Before the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1, 10 μL of BSA (0.5% m/v) was added on the sensor surface for 5 min in order to block non-specific bindings. Finally, for the PEC measurements, the immunosensor was washed with deionized water and measurements were performed in 0.1 mol L−1 HEPES buffer solution (pH 7.0), containing 0.3 mol L−1 of AA, Eapl. = 0.0 V.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of the materials used to build the PEC platform

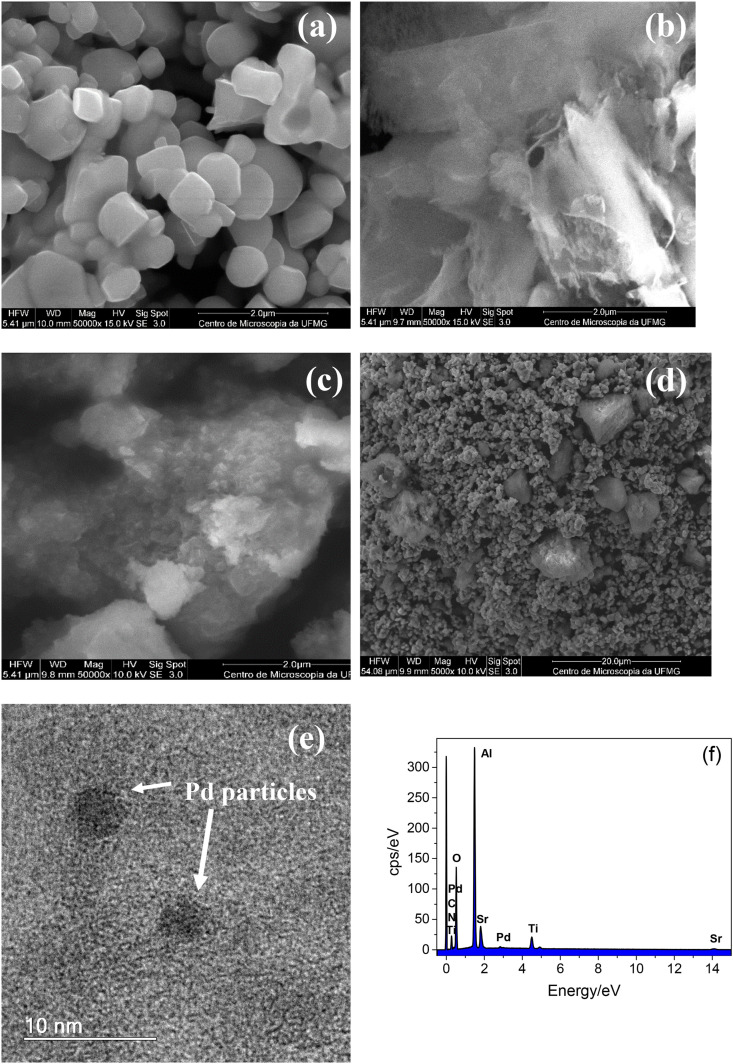

The Fig. 1 shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (a) strontium titanate, SrTiO3, (b) sulfur-doped carbon nitride, g-C3N4-S, (c) palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix, Pd/AlO(OH), and (d) the composite material (PdNPs/CNS/ST). The SEM image of SrTiO3 show nanometric particles with edges relatively smooth. On the other hand, the sulfur doped carbon nitride presented micrometer structures of exfoliated surface.

Fig. 1.

SEM images of scanning electron microscopy images of (a) strontium titanate, SrTiO3, (b) sulfur-doped carbon nitride, g-C3N4-S, (c) palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix, Pd/AlO(OH), and (d) the composite material (PdNPs/CNS/ST), (e) TEM image of PdNPs/CNS/ST sample, (f) and EDX spectrum of the PdNPs/CNS/ST sample.

The SEM image of the palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix, Pd/AlO(OH) show rugous micrometric particles (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, the PdNPs/CNS/ST composite presents a heterogeneuos morphology with particles of different dimensions including micrometric and nanometric particles. TEM image presented in Fig. 1e show the presence of the palladium nanoparticles in the PdNPs/CNS/ST composite. Fig. 1f show the EDX spectrum of the PdNPs/CNS/ST sample. As can be seen, the EDX spectrum has shown the presence of Pd, Al, C, N, Ti, O, and Sr elements on the surface of composite suggesting the successful preparation of PdNPs/CNS/ST sample.

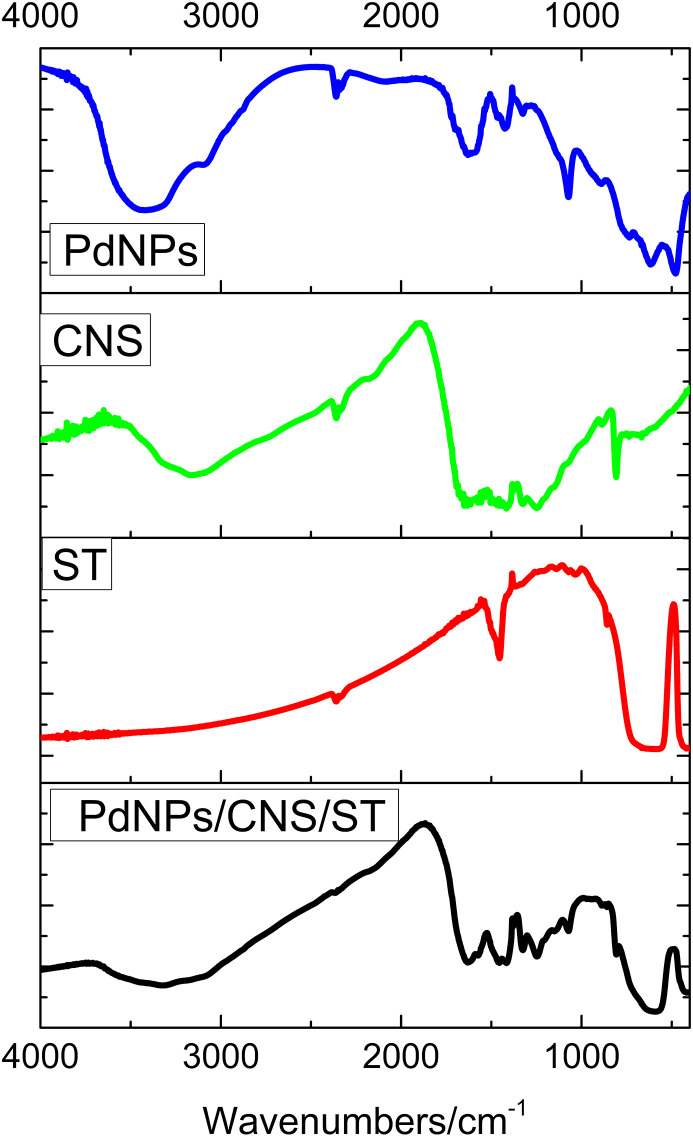

The materials that make up the PEC platform and the complete composite material were characterized by FTIR and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) techniques. In this sense, Fig. 2 shows the FTIR spectra for palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix (PdAlO(OH) or PdNPs). The PdNPs (blue spectrum) show a peak around 3450 cm−1 and a weak band at 1641 cm−1 referring to the elongation of adsorbed water. In addition, bands at 1072 cm−1 and 740, 620 and 479 cm−1 correspond, respectively, to the symmetrical vibration Al–OH and Al–O groups, respectively (Liu et al., 2012; Abdollahifar et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2018).

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectra for PdNPs, CNS, ST, and PdNPs/CNS/ST.

The g–C3N4–S (CNS) spectrum (Fig. 2, Green spectrum) presented bands in 3500–3000 cm−1 corresponding to the stretching vibration of N–H probability attributed to uncondensed amine groups and O–H groups from adsorbed water molecules. The bands between 1200 and 1700 cm−1 can be assigned to stretching vibration modes of the aromatic CN heterocycle and a sharp absorption band appearing at 810 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of the triazine units (Guan et al., 2021). The spectrum obtained for SrTiO3, ST (Fig. 2, red spectrum) shows peaks around 1470 cm−1 that can be attributed to the elongation modes of the carboxylate group (COOH). The peaks around 851 cm−1 and 585 cm−1 correspond to the vibration and elongation of Ti–O (Xian et al., 2014; Mohammadi et al., 2020). The spectrum obtained for the PdNPs/CNS/ST composite (Fig. 2, black spectrum) indicate the presence of the ST with CNS and PdNPs, since the bands related to each material are observed for the complete composite.

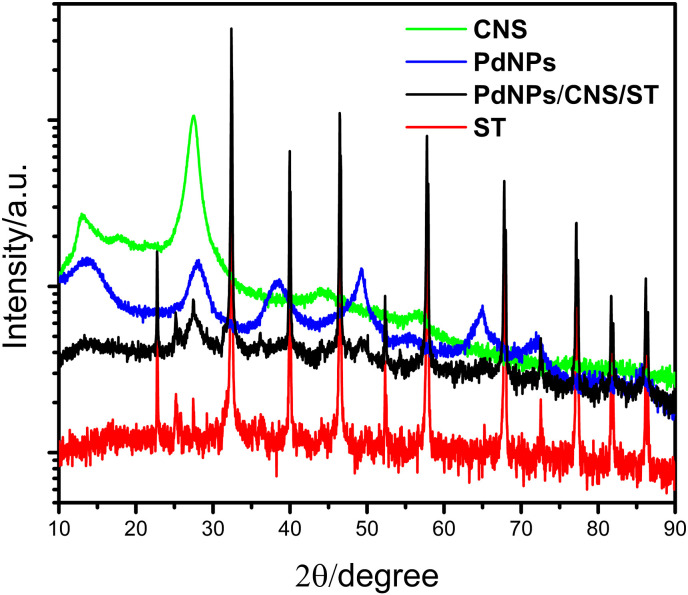

Fig. 3 shows the diffractograms of the materials that make up the composite. In the ST XRD pattern (red diffractogram) it is possible to observe the peaks corresponding to the planes (100), (110), (111), (200), (210), (211), (220), (310), and (222) that belong to the cubic perovskite structure with space group Pm-3m (ICDD-01-084-0444). The peaks close to 25.0° and 27.5° are impurities not identified.

Fig. 3.

DRX spectra for the ST (SrTiO3); CNS (g–C3N4–S); PdNPs (PdAlO(OH)), and PdNPs/CNS/ST.

The CNS diffractogram (Fig. 3, green diffractogram) shows the two (001) and (002) peaks at 13.10° and 27.43°, respectively, corresponding to interlayer stacking of the aromatic system, that are characteristic of graphitic materials (Wang et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2016; Cao et al., 2017). Finally, in Fig. 3, blue diffractogram, peaks characteristic of the planes (020), (120), (031), (200), (002), and (251) can be observed, which are attributed to the nanocrystalline structure of the aluminum oxide hydroxide, with orthorhombic structure and space group Amam. It is also noted that there is no peak observed for the PdNPs material, as observed in the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 2, blue spectrum), which is due to the Pd/AlO(OH) compound (described as PdNPs) presenting only 0.5% Pd metal (by weight) (Goksu, 2015). In addition, the XRD spectrum of the material PdNPs/CNS/ST (black diffractogram) shows characteristics of the three above-mentioned patterns, indicating the mixing of the three studied materials.

3.2. Electrochemical and photoelectrochemystry measurements

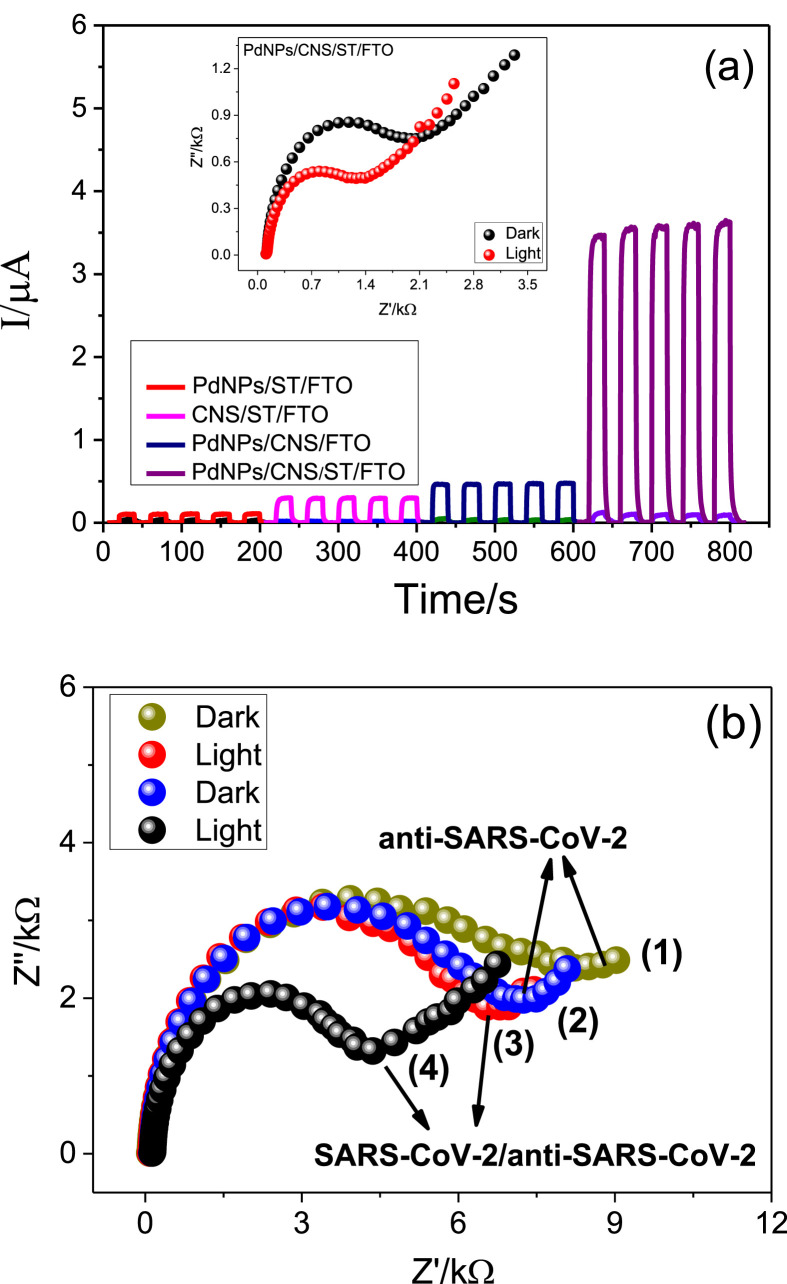

Fig. 4a shows the amperograms referring to the FTO platforms modified with PdNPs/ST, CNS/ST, PdNPs/CNS, and PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO in the presence of a 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffer solution (PBS) in the absence and presence of 0.2 mol L−1 AA, under an applied potential of 0.0Vv Ag/AgCl and incidence of chopped light. For all photoelectrochemical platforms, there is a significant increase in photocurrents when they are in the presence of the donor molecule. The increase of the photocurrent in the presence of donor molecule is due to a lower recombination of the photogenerated electron/hole pairs due to the transfer of electrons from the AA to the platforms. However, the comparison of the photocurrent of the different modified FTO electrodes shows that the FTO modified with PdNPs/CNS/ST presented a significantly higher photocurrent compared to the other electrodes. This result is probably due to the strong synergism existing in relation to strontium titanate, sulfur-doped carbon nitride and palladium nanoparticles trapped in aluminum hydroxide matrix. The combination of these three materials provided an increase in the speed of electronic transfer of ascorbic acid, thus favoring a greater sensitivity of the system. The figure inserted in Fig. 4a shows the Nyquist diagrams for the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform in the presence of 0.1 mol L−1 KCl containing 5 mmol L−1 of K3[Fe(CN)6]. The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) were obtained in the absence (black spectrum) and presence (red spectrum) of visible LED light. According to this figure, it is observed that in the presence of light there is a decrease in the resistance to charge transfer between the redox probe and the surface of the modified FTO. This decrease suggests an increased photogeneration of the electron/hole pairs on the surface of the FTO containing the PdNPs/CNS/ST composite material.

Fig. 4.

(a) Amperograms obtained for PdNPs/ST/FTO (red amperogram), CNS/ST/FTO (pink amperogram), PdNPs/CNS/FTO (blue amperogram), PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO (purple amperogram). Experiments carried out in 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.0. Eappl. = 0.0 V vs Ag/AgCl. Inset of Fig. 4(a)): Nyquist plots for the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform in without and with incidence of visible LED light. (b) Nyquist plots for the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform without (spectrum 1) and with incidence of visible LED light (spectrum 2), Nyquist plots for the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform without (spectrum 3) and with incidence of visible LED light (spectrum 4) after incubation in a SARS-CoV-2 solution. EIS experiments performed in 0.1 mmol L−1 KCl solution containing 5 mmol L−1 K3[Fe(CN)6] and Eappl. = 0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4b shows the EIS for the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform in the absence (spectrum 1) and presence (spectrum 2) of visible LED light as well as the EIS for the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform previously incubated in a solution containing the SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform) in the absence (spectrum 3) and presence (spectrum 4) of light. As can be seen, the incidence of light provides a decrease of the charge transfer resistance between the redox probe and the PEC platform. These results suggest that the electrode modified with PdNPs/CNS/ST is a sensitive electrochemical platform for monitoring of SARS-CoV-2, since the SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2 interaction has promoted a change of the analytical signal obtained with the platform for the probe molecule. Thus, the best conditions for obtaining the analytical signal of the donor molecule were further evaluated through the study of its concentration, pH of the medium, type of buffer solution and potential applied to the working electrode.

Fig. S1a shows an increase of the photocurrent with an increase of the concentration of ascorbic acid (AA) from 0 to 0.4 mol L−1. As can be seen, the photocurrent has increased significantly from 0 up to 0.3 mol L−1 and for AA concentrations higher than 0.3 mol L−1 there is very low variation of the photocurrent of the platform for the donor molecule (Fig. S1a and S1a1) indicating that for concentrations higher than 0.3 mol L−1 is reaching a saturation of the response due to the more difficult oxidation of the donor molecule on the photoelectrochemical platform surface.

Fig. S1b shows the amperograms obtained for 0.1 mol L−1 PBS with pH values ranging from 5.0 to 8.0. The photocurrent values increase from pH 5.0 up to pH 7.0 and decrease for pH values higher than 7.0 (Fig. S1b1). This result suggests that in an electrolyte that has an equal concentration of hydronium ions and hydroxyl ions, there is greater stability for the photoelectrochemical platform and, consequently, a better response for the donor molecule. In this sense, an electrolyte solution with a pH value of 7.0 was used for the other studies.

Fig. S1c shows amperograms for different buffers (Britton-Robinson – BR; Phosphate – PBS; Mcllvaine – MC; Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride – TRIS; Piperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) – PIPES; and N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) – HEPES). According to Fig. S1c it is observed that a higher photocurrent was achieved with the HEPES buffer. The HEPES buffer may act as an effective antenna molecule to some semiconductors improving the visible light photoactivity (Qiu et al., 2018; Yotsumoto Neto et al., 2019). Thus, the HEPES buffer probably can interact with the photoactive composite improving the photocurrent of the photoelectrochemical platform.

Fig. S1d shows the photocurrent responses of the platform for different potentials applied to the working electrode (from −0.3 to +0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl) to favor AA oxidation and verify at which potential the maximum oxidation of the donor molecule occurs. Based on the amperograms, it is observed that the photocurrent increased from −0.3 V to 0.0 V and remained constant between 0.0 and 0.1 V. At potentials higher than 0.1 V, a decrease in the platform photocurrent is observed, probably due to higher charge recombination. In this context, the 0.0 V potential was chosen to be applied to the working electrode in further studies.

Fig. S2a shows an amperometric response of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform modified with SARS-CoV-2 antibody at different concentrations 0–10 μg mL−1. These studies were performed in 0.1 mol L−1 HEPES buffer solution, pH 7.0, under an applied potential (Eappl.) of 0.0 V vs Ag/AgCl. This figure shows that increasing the antibody concentration from 0 to 10 μg mL−1 provides a gradual decrease in the photocurrent of the photoelectrochemical platform in the presence of AA. These results suggest that the SARS CoV-2 antibody makes the oxidation of the donor molecule more difficult, favoring the recombination of photogenerated charges. It is observed that after the immobilization of the antibody, there is a variation in the photocurrent of the system, which increases more significantly between 0 and 5 μg mL−1 and remains practically constant between the concentration of 5 and 10 μg mL−1. Due to the small difference between photocurrents for SARS-CoV-2 antibody concentrations between 5 and 10 μg mL−1 and the economy of the reagent, the concentration of 5 μg mL−1 was chosen for the other studies.

The SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2 interaction time is extremely important for the development and application of an immunosensor in order to find a better interaction between biological materials on the anti-SARS-CoV-2 modified platform. Thus Fig. S2b shows amperograms for different incubation times (0; 5; 10; 15; 20; 25; 30; 35; and 40 min) of the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform in a solution of SARS-CoV-2. Fig. S2b shows that there is a gradual decrease in the photocurrent of AA on the PEC platform up to a time of 30 min with the increase of the incubation time, indicating an increase in the recombination of photogenerated charges on the electrode surface. After this time, it is observed that the photocurrent does not change and remains constant up to 40 min. In this sense, an incubation time of 30 min was fixed for the construction of the analytical curve.

The evaluation of the precision of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform was performed in the presence of 0.3 mol L−1 AA through the repeatability of 24 successive measurements of the fotocurrent performed within a time interval of 1000 s. Fig. S2c shows the amperograms for the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC platform (black amperogram), SARS-CoV-2 antibody modified PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform (red amperogram) and the SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2 modified PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform (blue amperogram). After performing the measurements, it was possible to assess the precision of the sensor considering the relative standard deviation (RSD) of all photocurrent values (0.12%, 0.56% and 1.62%, respectively). From the results, it can be seen that the immunosensor before and after the immobilization of SARS-CoV-2/anti-SARS-CoV-2 provided us with excellent values of RSD, so the immunosensor platform has good repeatability for measurements performed on the same working day. Additionally, in order to verify the stability of the platform after the immobilization of 5 μg mL−1 of the SARS-CoV-2 antibody on the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform, five PEC platforms were prepared in the same way and on different working days (Fig. S2d)Fig. S1d. Thus, a RSD of about 2.3% was calculated for the prepared platforms, which suggests that the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform presents good reproducibility.

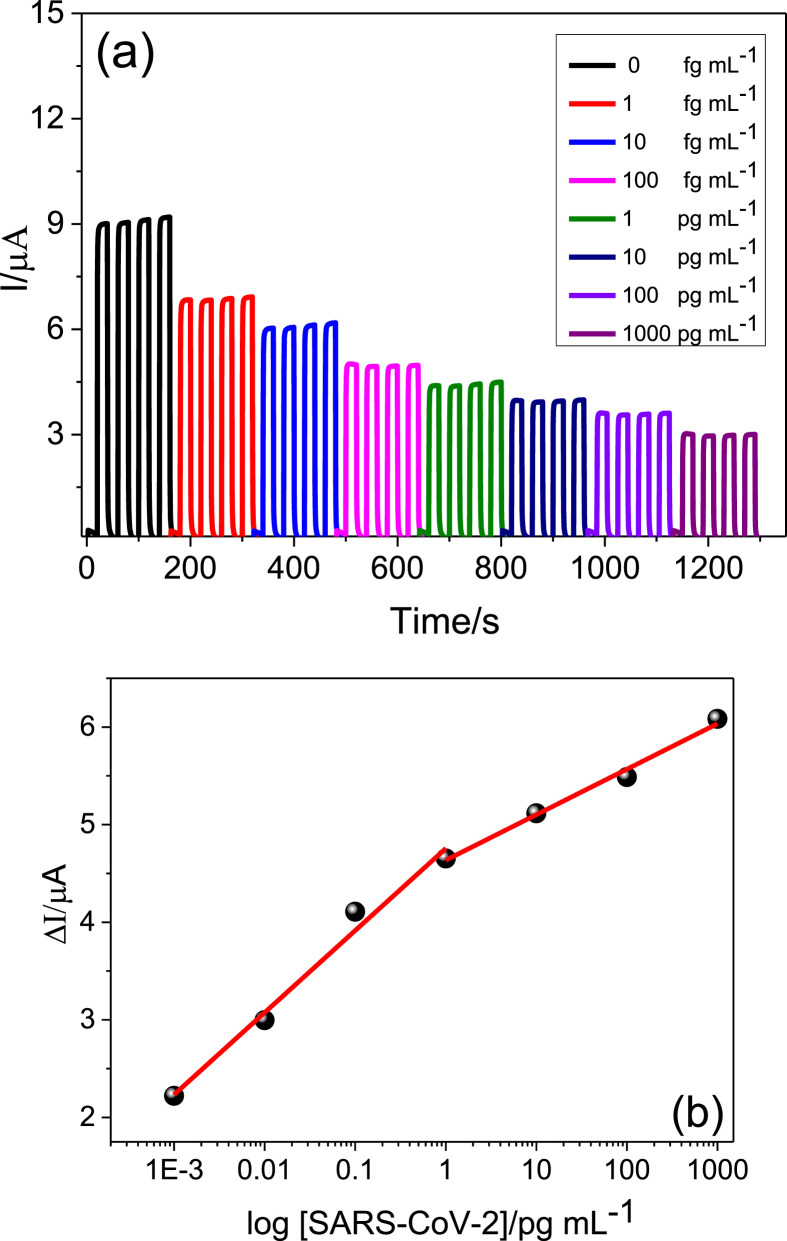

Fig. 5a shows the amperograms for diferent concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 (from 0 to 1000 pg mL−1). In this figure, it can be seen that as the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 was increased, a decrease in the photocurrent of the system was observed. As can be seen in Fig. 5b, the association between SARS-CoV-2 and immobilized antibody increases the shift of the photocurrent [(ΔI = (Io – I)] of the immunosensor, showing that the photocurrent intensity is proportional to the logarithm of SARS-CoV-2 concentration, where Io and I are the photocurrent of the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform before and after incubating with SARS-CoV-2, respectively.

Fig. 5.

(a) Photocurrent response for anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor for blank (black amperogram) and after incubating in different concentrations of SARS-CoV-2: 1 fg mL−1; 10 fg mL−1; 100 fg mL−1; 1 pg mL−1; 10 pg mL−1; 100 pg mL−1; 1000 pg mL−1 (other amperograms). (b) Analytical curve for SARS-CoV-2 detection with the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO immunosensor platform. Measurements carried out in 0.1 mol L−1 HEPES solution (pH 7.0) containing 0.3 mol L−1 AA. Eappl. = 0.0 V vs Ag/AgCl(sat. KCl). tinc = 30 min. The RSD was less than 1%.

The analytical curve for SARS-CoV-2 exhibited two good linear relationships for concentrations ranging from 1 to 1000 fg mL−1 and 1–1000 pg mL−1. The linear regression equations were ΔI/μA = 4.76 + 0.84 log ([SARS-CoV-2]/pg mL−1), with a correlation coefficient of 0.992 and ΔI/μA = 4.64 + 0.47 log ([SARS-CoV-2]/pg mL−1) with a correlation coefficient of 0.996. The proposed method is able to experimentally detect 1 fg mL−1. The analytical characteristics of this PEC immunosensor were compared to previously reported methods. It can be seen from Table S1 (Funari et al., 2020, Imran et al., 2021, Karakus et al., 2021, Moitra et al., 2020, Pramanik et al., 2021, Rahmati et al., 2021, Vadlamani et al., 2020, Yakoh et al., 2021) show that the proposed PEC immunosensor exhibits some superior characteristics or similar to the others immunosensors for SARS-CoV-2.

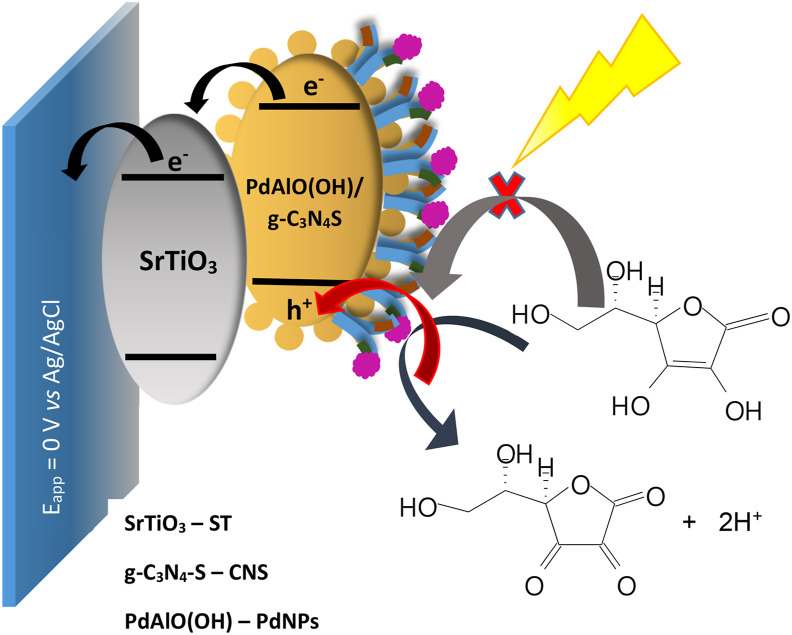

The mechanism by which the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC immunosensor detects the presence of SARS-CoV-2 under visible LED light illumination is presented in Fig. 6 . According to the proposed mechanism, the PdNPs/g-C3N4S material on the surface of the SrTiO3/FTO platform captures photons promoting electrons from valence band to conducting band giving rising to e−/h+ couples. Thus the electron photogenerated at conducting band of PdNPs/g-C3N4S can be injected in the conduction band of the perovskite (SrTiO3) and later to the FTO electrode and the hole in the valence band of the PdNPs/g-C3N4S can be transferred to the hole scavenger molecule. Simultaneously, the SARS-CoV-2 protein present in the sample can interact with the immobilized anti-SARS-CoV-2, decreasing the efficiency of the system to produce photocurrent since the anti-SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV-2 interaction reduces the efficiency of the photoactive material to transfer holes to donor molecules.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism for the photoelectrochemical detection of the immunosensor anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO.

4. Application of the photoelectrochemical immunosensor in artificial saliva samples

In order to evaluate the accuracy and the applicability of the designed immunosensing platform in artificial saliva samples, the anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC sensor was tested to target SARS-CoV-2 at different concentrations in artificial saliva samples. The samples were spiked with the following concentrations of SARS-CoV-2: 1 fg mL−1, 10 fg mL−1, 100 fg mL−1, 1 pg mL−1, 10 pg mL−1 e 100 pg mL−1 and the quantification of the biological material in the spiked samples was performed by the external calibration method. The found recovery values were between 96.20% and 109.65% (Table S2) with low values of relative standard deviation, indicating good accuracy and precision. The results suggest that the developed PEC immunosensor is a promissing strategy for the detection of SARS-CoV-2.

5. Conclusion

The present work reports the development of a PEC immunosensor for feasible SARS CoV-2 spike glycoprotein detection based on a low cost commercial LED lamp of low power combined to a homemade box to control the incidence of light. The electrochemical response of the PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO platform was highly sensitive to light incidence onto the PEC cell suggesting an improved electron-hole separation under visible LED light illumination. The interaction between SrTiO3 particles with g–C3N4–S and palladium nanoaprticles improved the PEC efficiency of the sensing platform under visible LED light, reflecting on a wide linear response range and a low limit of detection for SARS CoV-2 S1 protein. The designed immunosensor is a feasible device to sensitive, accurate and precise determination of SARS-CoV-2 in artificial saliva samples. The anti-SARS-CoV-2/PdNPs/CNS/ST/FTO PEC immunosensor may be a promising alternative for detection of SARS CoV-2 in non-invasive biological samples as saliva due its high sensitivity and detectability.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chirlene N. Botelho: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Suringo S. Falcão: Formal analysis; Writing - review & editing. Rossy-Eric P. Soares: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Alan S. de Menezes: XRD analyzes, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Silma R. Pereira: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Lauro T. Kubota: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Flavio S. Damos: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Rita C. S. Luz: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Bioanalítica (465389/2014-7); Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico do Maranhão - FAPEMA (INFRA-03186/18, INFRA-03195/18, UNIVERSAL-01057/19), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq (308204/2018-2; 309828/2020-1). The authors gratefully acknowledge the Analytical Center of UFMA that provided the FTIR spectra. C. N. Botelho acknowledge to FAPEMA for the scholarship. The authors gratefully acknowledge to the Microscopy Center/UFMG that provided the morphological images and EDX spectrum.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosx.2022.100167.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abdollahifar M., Zamani M.R., Beiygie E., Nekouei H. Synthesis of micro– mesopores flower-like γ-Al2O3 nano-architectures. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2014;79(8):1007–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Amanat F., Stadlbauer D., Strohmeier S., Nguyen T.H.O., Chromikova V., McMahon M., Jiang K., Arunkumar G.A., Polanco J., Bermudez-Gonzalez M., Caplivski D., Cheng A., Kedzierska K., Vapalahti O., Hepojoki J.M., Simon V., Krammer F. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat. Med. 2020;26(7):1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0913-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard A.J. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 2001. Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Qin C., Wang Y., Zhang H., Sun G., Zhang Z. Solid-state method synthesis of SnO2-Decorated g-C3N4 nanocomposites with enhanced Gas-sensing property to ethanol. Materials. 2017;10(6):604. doi: 10.3390/ma10060604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai B., Yan J.T., Wang C.L., Ren Z.D., Zhu Y.C. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B over phosphorus doped graphitic carbon nitride. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;391:376–383. [Google Scholar]

- Choi E., Song K., An S., Lee K., Youn M., Park K., Jeong S., Kim H. Cu/ZnO/AlOOH catalyst for methanol synthesis through CO2 hydrogenation. Kor. J. Chem. Eng. 2018;35:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Choudary B.M., Madhi S., Chowdari N.S., Kantam M.L., Sreedhar B. Layered double hydroxide supported Nanopalladium catalyst for Heck-, Suzuki-, Sonogashira-, and Stille-type coupling reactions of chloroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(47):14127–14136. doi: 10.1021/ja026975w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.K.W., Pan Y., Cheng S.M.S., Hui K.P.Y., Krishna P., Liu Y., Poon L.L.M. Molecular diagnosis of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing an outbreak of pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 2020;66(4):549–555. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Domínguez S., Berenguer A., Linares A., Cazorla D. Inorganic materials as supports for palladium nanoparticles: application in the semi-hydrogenation of phenylacetylene. J. Catal. 2008;257(1):87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fu J.W., Yu J.G., Jiang C.J., Cheng B. g-C3N4-based heterostructured photocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;8 [Google Scholar]

- Funari R., Chu K.Y., Shen A.Q. Detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by gold nanospikes in an opto-microfluidic chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;169 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gniewek A., Ziólkowski J.J., Trzeciak A.M., Zawadzki M., Grabowska H., Wrzyszcz J. Palladium nanoparticles supported on alumina-based oxides as heterogeneous catalysts of the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction. J. Catal. 2008;254(1):121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Goksu H. Recyclable aluminium oxy-hydroxide supported Pd nanoparticles for selective hydrogenation of nitro compounds via sodium borohydride hydrolysis. New J. Chem. 2015;39:8498–8504. [Google Scholar]

- Guan K., Li J., Lei W., Wang H., Tong Z., Jia Q., Zhang H., Zhang S. Synthesis of sulfur doped g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic activity in molten salt. J. Materiomics. 2021;7:1131–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Wang L.J., Sun H.R., Li M.Y., Shi W.L. High-efficiency photocatalytic water splitting by a N-doped porous g-C3N4 nanosheet polymer photocatalyst derived from urea and N, N-dimethylformamide. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020;7:1770–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Imran S., Ahmadi S., Kerman K. Electrochemical biosensors for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses. Micromachines. 2021;12(2):174. doi: 10.3390/mi12020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Yuan X., Pan Y., Liang J., Zeng G., Wu Z., Wang H. Doping of graphitic carbon nitride for photocatalysis: a review. Appl. Catal., B. 2017;217:388–406. [Google Scholar]

- Karakus E., Erdemir E., Demirbilek N., Liv L. Colorimetric and electrochemical detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen with a gold nanoparticle-based biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021;1182 doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S.S.A., Karim Q.A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:2126–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6. 10317 Erratum in: Lancet. 2022; 399(10320):142. PMID: 34871545; PMCID: PMC8640673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Shetti N.P., Jagannath S., Aminabhavi T.M. Electrochemical sensors for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;430 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.132966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lillehoj P.B. Microfluidic magneto immunosensor for rapid, high sensitivity. ACS Sens. 2021;6(3):1270–1278. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.0c02561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Wang L., Li H. Application of recoverable nanosized palladium (0) catalyst in Sonogashira reaction. Tetrahedron. 2005;61(36):8633–8640. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sun Y., Dong F., Ho W.K. Enhancing the photocatalytic activity of bulk gC3N4 by introducing mesoporous structure and hybridizing with graphene. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;436:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.F., Wang S., Chang W., Zhang L.H., Wu Z.S., Song S.Y., Xing Y. Preparation and enhanced photocatalytic performance of sulfur doping terminal-methylated g-C3N4 nanosheets with extended visible-light response. J. Mater. Chem. 2019;7:20640–20648. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Shih K., Gao Y., Li F., We L. Dechlorinating transformation of propachlor through nucleophilic substitution by dithionite on the surface of alumina. J. Soils Sediments. 2012;12:724–733. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães S.R., Junior W.D.M., Souza A.E., Teixeira S.R., Li M.S., Longo E. Synthesis of BaTIO3 and SrTIO3 by microwave assisted hidrotermal method (mah) using anatase as titanium precursor. Quim. Nova. 2017;40(2):166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmandoust M., Pinar Gumus Z., Soylak M., Erk N. Electrochemical immunosensor for rapid and highly sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in the nasal sample. Talanta. 2022;240 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi P., Ghorbani-Shahna F., Bahrami A., Rafati A.A. Farhadian M. Plasma-photocatalytic degradation of gaseous toluene using SrTiO3/rGO as an efficient heterojunction for by-products abatement and synergistic effects. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2020;394 [Google Scholar]

- Moitra P., Alafeef M., Dighe K., Frieman M.B., Pan D. Selective Naked-eye detection of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by N Gene targeted antisense oligonucleotide capped plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2020;14(6):7617–7627. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Narvaez E., Dincer C. The impact of biosensing in a pandemic outbreak: COVID-19. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;163 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu P., Zhang L., Liu G., Cheng H.M. Graphene-Like carbon nitride nanosheets for improved photocatalytic activities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22(22):4763–4770. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira B.A., Oliveira L.C., Sabino E.C., Okay T.S. SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 disease: a mini review on diagnostic methods. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 2020;62:44. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202062044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirouz B., Haghshenas S.S., Haghshenas S.S., Piro P. Investigating a serious challenge in the sustainable development process: analysis of confirmed cases of COVID-19 (new type of coronavirus) through a binary classification using artificial intelligence and regression analysis. Sustainability. 2020;12:2427. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A., Gao Y., Patibandla S., Mitra D., McCandless M.G., Fassero L.A., Gates K., Tandon R., Ray P.C. The rapid diagnosis and effective inhibition of coronavirus using spike antibody attached gold nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2021;3:1588–1596. doi: 10.1039/d0na01007c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Shu J., Tang D. Nayf4:yb, er upconversion nanotransducer with in-situ fabrication of Ag2S for near-infrared light responsive photoelectrochemical biosensor. Anal. Chem. 2018;90(20):12214–12220. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati Z., Roushani M., Hosseini H., Choobin H. Electrochemical immunosensor with Cu2O nanocube coating for detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Microchim. Acta. 2021;188:105. doi: 10.1007/s00604-021-04762-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozhansky I.V., Zakheim D.A. Modeling of the electrical properties of polycrystalline ceramic semiconductors with submicron grains. Microelectron. Eng. 2005;81(2):494–502. [Google Scholar]

- Sagara N., Kamimura S., Tsubota T., Ohno T. Photoelectrochemical CO2 reduction by a p-type boron-doped g-C3N4 electrode under visible light. Appl. Catal., B. 2016;192:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Shao L., Jiang D., Xiao P., Zhu L., Meng S., Chen M. Enhancement of g-C3N4 nanosheets photocatalysis by synergistic interaction of ZnS microsphere and RGO inducing multistep charge transfer. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016;198:200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto J., Leroux F., Dubois M., Taviot C., Valim J.B. Hybrid organic–inorganic materials: layered hydroxy double salts intercalated with substituted thiophene monomers. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2006;67(5–6):978–982. [Google Scholar]

- Trzeciak A.M., Augustyniak A.W. The role of palladium nanoparticles in catalytic C–C cross-coupling reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;384:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamani B., Uppal T., Verma S., Misra M. Functionalized TiO2 nanotubebased electrochemical biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Sensors. 2020;20(20):5871. doi: 10.3390/s20205871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Bian Y.R., Hu J.T., Dai L.M. Highly crystalline sulfur-doped carbon nitride as photocatalyst for efficient visible-light hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal., B. 2018;238:592–598. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Maeda K., Thomas A., Takanabe K., Xin G., Carlsson J.M., Domen K., Antonietti M. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 2008;8(1):76–80. doi: 10.1038/nmat2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report – 134. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200602-covid-19-sitrep-134.pdf?sfvrsn=cc95e5d5_2

- Word Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2021. https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=CjwKCAjwnK36BRBVEiwAsMT8WJ3y00_BUzvrLsvbl3uthuoTHOcc45gyEUbpYRyEqAzll3aZB6TYxoCcM0QAvDBwE

- Wu Geng-huang, Wu Yan-fang, Liu Xi-wei, Rong Ming-cong, Chen Xiao-mei, Chen Xi. An electrochemical ascorbic acid sensor based on palladium nanoparticles supported on graphene oxide. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;745:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian T., Yang H., Di L., Ma J., Zhang H., Dai J. Photocatalytic reduction synthesis of SrTiO3-graphene nanocomposites and their enhanced photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014;9(1):327. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Zhang Y., Li L., Shao Q., Huang X. Recent progress in low-dimensional palladium-based nanostructures for electrocatalysis and beyond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022;459 [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Sadique M.A., Ranjan P., Kumar N., Singhal A., Srivastava A.K., Khan R. SERS based lateral flow immunoassay for point-of-care detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;4(4):2974–2995. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.1c00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoh A., Pimpitak U., Rengpipat S., Hirankarn N., Chailapakul O., Chaiyo S. Paper-based electrochemical biosensor for diagnosing COVID-19: detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;176 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Fei Z., Zhao D., Ang W.H., Li Y., Dyson P.J. Palladium nanoparticles Stabilized by an ionic polymer and ionic liquid: a versatile system for C−C cross-coupling reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47(8):3292–3297. doi: 10.1021/ic702305t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wang L.-J., Wang X.-P., Chen J.-X., Yang X.-W., Li M.-H., Deng M.-J. Perovskite-type SrTiO3 thin film preparation and field emission properties. Vacuum. 2020;178(1) [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto Neto S., Lima M.I.S., Pereira S.R.F., Goulart L.R., Luz R.C.S., Damos F.S. Immunodiagnostic of leprosy exploiting a photoelectrochemical platform based on a recombinant peptide mimetic of a Mycobacterium leprae antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019;143 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.J., Shi R., Zhao Y.X., Bian T., Zhao Y.F., Zhou C., Waterhouse G.I.N., Wu L.Z., Tung C.H., Zhang T.R. Alkali-assisted synthesis of nitrogen deficient graphitic carbon nitride with tunable band structures for efficient visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201605148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li H., Li J., Sun H., Zhou L., Wang R. A novel photoelectrochemical sensor based on Gr-SiNWs-Si/Pt electrode for sensing of Hydroquinone. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019;14:1794–1808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Shi R., Shang L., Wu L.Z., Tung C.H., Zhang T.R. Template-free large-scale synthesis of g-C3N4 microtubes for enhanced visible light-driven photocatalytic H2 production. Nano Res. 2018;11:3462–3468. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.