Abstract

Menopause has been linked to changes in memory. Oestrogen-containing hormone therapy is prescribed to treat menopause-related symptoms and can ameliorate memory changes, although the parameters impacting oestrogen-related memory efficacy are unclear. Cognitive experience and practice have been shown to be neuroprotective and to improve learning and memory during ageing, with the type of task playing a role in subsequent cognitive outcomes. Whether task complexity matters, and whether these outcomes interact with menopause and oestrogen status, remains unknown. To investigate this, we used a rat model of surgical menopause to systematically assess whether maze task complexity, as well as order of task presentation, impacts spatial learning and memory during middle age when rats received vehicle, low-17β-oestradiol (E2) or high-E2 treatment. The direction, and even presence, of the effects of prior maze experience differed depending on the E2 dose. Surgical menopause without E2 treatment yielded the least benefit, as prior maze experience did not have a substantial effect on subsequent task performance for vehicle treated rats regardless of task demand level during the first exposure to maze experience or final testing. High-dose E2 yielded a variable benefit, and low-dose E2 produced the greatest benefit. Specifically, low-dose E2 broadly enhanced learning and memory in surgically menopausal rats that had prior experience on another task, regardless of the complexity level of this prior experience. These results demonstrate that E2 dose influences the impact of prior cognitive experience on learning and memory during ageing, and highlights the importance of prior cognitive experience in subsequent learning and memory outcomes.

Keywords: ageing, cognitive reserve, memory, menopause, oestradiol

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Ageing is often accompanied by a decline in cognitive function. A diverse set of variables, including genetic, epigenetic, and lifestyle factors, contribute to the extent and severity of cognitive changes in an ageing individual. Collectively, these factors have an impact on whether that individual undergoes typical brain ageing processes, or develops pathological and cognitive changes associated with neurodegenerative disease and dementia. Although women typically live longer than men, age alone does not account for the disproportionate number of women affected by the most common form of dementia, Alzheimer's disease.1,2 The significant decline in ovarian hormones that women experience by midlife with menopause can be accompanied by cognitive changes. Indeed, as many as two-thirds of menopausal women report memory changes, especially in domains related to working memory and attention.3-11

Ovarian hormones, and oestrogens in particular, functionally impact all major peripheral body systems, as well as the brain. Further exploration into the complex interplay between the endocrine system and cognition is necessary to more clearly understand how these systems work together to impact brain health during midlife and beyond. That oestrogens are neuroprotective remains a popular tenet receiving significant scientific support and attention over the past few decades. Basic science research utilising animal models has shown that under certain conditions, oestrogen treatment enhances memory in surgically menopausal, or ovariectomised (OVX), rodents.12-17 Underlying factors contributing to variations in oestrogen-induced cognitive efficacy have been of great interest to the field. In part, these queries stem from the collective results of past and ongoing clinical trials evaluating oestrogen-containing hormone therapy in women. The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) suggested that initiating oestrogen-containing hormone therapy (specifically conjugated equine oestrogens; CEE) given with or without the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate in post-menopausal women aged 65 years and older could be detrimental to cognition and increase the relative risk of developing dementia.18-20 More recent ongoing evaluations (eg, the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study [KEEPS], the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estrogen [ELITE], the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study-Younger [WHIMS-Y], the Women's Health Initiative Study of Cognitive Aging [WHISCA] and the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation [SWAN]) have been undertaken aiming to better understand cognitive ageing, as well as how the use of oestrogen-containing hormone therapy impacts cognition and other health-related outcomes.21-26 The expansion and continuation of clinical studies emphasises that the merit of deciphering factors impacting oestrogen-containing hormone therapy is enduring, and that the possibility remains for hormone therapy to positively impact age-related cognitive change in women.

Even with the plethora of research indicating that oestrogen can induce positive effects on the brain and its functioning, it is important to acknowledge that oestrogen-containing hormone therapy is not a golden ticket to ensure healthy brain ageing. Indeed, currently the clinical recommendation is to not prescribe hormone therapy for the primary indication of memory complaints.27 There are conflicting reports in the scientific literature regarding factors that impact the efficacy of hormone therapy for cognition.28-30 Some lifestyle factors have been positively correlated to healthy cognitive ageing, including prior cognitive experience and cognitive practice. Both clinical and preclinical research suggest that performing complex cognitive tasks can be neuroprotective during ageing as well as delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease.31 Several decades of human research associates a higher educational attainment with a decreased incidence of developing dementia and good cognition while living longer lives.32-35 Findings from the Nun Studies show an increased incidence of dementia with lower education levels.36 Similar results have been reported in a more heterogeneous population, representative of US adults over 50 years of age.34

Whether the extent of prior cognitive experience interacts with how oestrogen impacts age-related cognitive change in females remains unknown. This question poses challenges to investigate clinically as a result of ethical and logistical control issues.37 The experimental control afforded by rat models permits the deciphering of key variables associated with exogenous oestrogen exposures in conjunction with life factors including cognitive practice and reserve. We propose this can be roughly equated to cognitive reserve associated with educational attainment, albeit in a more narrow sense related to cognitive flexibility capacity. Rodents are often tested on a battery of maze tasks of varying complexity to evaluate different memory types.38 The order in which animals experience or learn these tasks could impact performance as well as the ability to shift task rule learning from one task to another. Indeed, our laboratory has shown that cognitive practice earlier in life benefits memory for a familiar task longitudinally for both sexes.39 Furthermore, females in particular have the capacity to transfer the benefits of earlier cognitive practice to novel tasks, even when they are aged.39 Although rodent models provide significant control over experimental conditions, some conflicting reports regarding the beneficial effects of oestrogen treatments on spatial memory tasks remain. One such instance is the Morris water maze, wherein we have previously reported 17β-estradiol (E2) administration to benefit spatial reference memory performance in some experimental designs,40,41 but not in others,17,42 despite identical protocols used for the task itself. Understanding the impact of prior learning and memory experience on later learning and memory prowess, and whether E2 exposure impacts outcomes, will aid in interpretating findings within and across laboratories, and benefit translation to humans with varied histories of cognitive demand and experience.

The overarching goal of the present study was to determine how prior cognitive demand experience alters subsequent learning and memory, as well as whether E2 treatment influences the effects of cognitive experience. We utilised two spatial memory tasks of varying cognitive demand and complexity. The delayed match-to-sample (DMS) water maze task was considered a low cognitive demand task that required animals to learn the new location of a single hidden platform within a day; the platform location changed each day, thus requiring the animals to update that platform location daily. The water radial-arm maze task (WRAM) was considered a high cognitive demand task because it involved an increasing working memory load within a day, such that animals had to remember several items of information to effectively solve the task each day. We tested whether prior low- and/or high- cognitive demand experience using spatial maze learning and memory altered learning and memory performance for subsequent tasks with or without tonic E2 treatment in middle-aged, surgically menopausal rats.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Subjects

Sixty female, non-sexually experienced Fischer-344-CDF rats were obtained from the National Institute on Aging colony at Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC, USA). Rats were 11 months old upon arrival. All animals were pair-housed, had free access to food and water, and were maintained under a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle for the entirety of the experiment. Rats were given 2 weeks to acclimate in the vivarium prior to the commencement of the experiment. All procedures were approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to National Institutes of Health standards.

2.2 ∣. Ovariectomy and hormone treatment

Surgeries were completed in two waves. OVX occurred 2 weeks after arrival to the facility. Under inhaled isoflurane anaesthesia, dorsolateral incisions were made in the skin and peritoneum. The ovaries and tips of the uterine horns were exposed, ligated, and excised. Muscle and skin incisions were sutured closed with dissolvable vicryl suture. All subjects received a s.c. injection of 5 mg/mL/kg Rimadyl® (carprofen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) (Orion Pharma Animal Health, Solletuna, Sweden) for pain management and 2 mL of sterile saline for post-surgical hydration. Rats were single-housed for a 48-hour recovery period before being re-pair-housed with a cage mate.

Two weeks after OVX, Alzet osmotic pumps (2006 model with a constant release rate of 0.15 μL of solution every hour for 6 weeks) (Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA, USA) were implanted s.c. to deliver vehicle (polyethylene glycol; PEG) or E2 treatment. Rats were anaesthetised using inhaled isoflurane anaesthesia and a small incision was made in the skin of the scruff of the neck. A small pocket was made in the s.c. space and osmotic pumps were inserted. The skin incision was sutured closed with dissolvable vicryl suture. Rats from each wave of surgery were randomly assigned to vehicle (PEG), low-E2 (2 μg /day dissolved in PEG) or high-E2 (4 μg /day dissolved in PEG) treatment groups. The E2 doses were based on doses known to produce cognitive-behavioural effects of exogenous oestrogen treatment when administered via osmotic pumps.43-45 Based on prior rodent research in our laboratory and others evaluating circulating serum E2 levels with exogenous treatment, the low-E2 dose was selected to produced medium-high physiological levels of circulating E2 similar to those observed during the oestrous cycle,46-50 and the high-E2 dose was selected to produce high physiological to supra-physiological circulating E2 levels because doses used in the rodent literature to investigate E2 effects on cognition and brain structure can exceed 10 μg.17,48,50 Rats were given a 48-hour recovery period before being re-pair-housed with their cage mate until euthanisation.

Rats were randomly assigned to the high cognitive demand WRAM-first condition (vehicle, n = 10; low-E2, n = 10; high-E2, n = 9) or the low cognitive demand DMS-first condition (vehicle, n = 11; low-E2, n = 10; high-E2, n = 10).

2.3 ∣. Vaginal cytology

Vaginal smears were obtained 1 day prior to osmotic pump insertion to confirm that OVX was successful. One day of smears was also completed 1 week after pump insertion to confirm successful vehicle treatment or hormone treatment in the oestrogen-treated groups. Smears were classified as proestrus-, oestrus-, metoestrus-, or dioestrus- like smears.51,52

2.4 ∣. Behaviour testing

Two weeks after osmotic pump surgeries, subjects began behavioural testing on either WRAM or DMS water mazes. Half of the rats in each treatment group were assigned to learn the high cognitive demand WRAM first, followed by the low cognitive demand DMS second. The other half were assigned to learn the low cognitive demand DMS first, followed by the high cognitive demand WRAM second. Rats were 12 months old at the start of behaviour testing.

2.5 ∣. WRAM

The win-shift eight-arm WRAM was a water escape task that measured spatial working and reference memory.13,38,53-57 The WRAM was constructed with eight evenly spaced and equally sized arms radiating out from the circular centre (each arm 38.1 cm × 12.7 cm). Salient spatial cues were placed on the walls and around the room to aid in spatial navigation. The maze was filled with room temperature water (maintained at 18-20°C) and made opaque with black non-toxic powdered paint. Each rat was assigned a pre-determined set of platform location combinations such that four of the eight arms contained a hidden escape platform at the end of the arm, submerged 2-3 cm beneath the surface of the water. Platform location combinations remained constant across days for each rat, but varied amongst rats. Each subject received four trials per day for 14 consecutive days. The first 12 days were considered baseline testing. At the beginning of each testing session, the rat was placed in the non-platformed start arm of the maze and was given a maximum of 3 minutes to locate a platform on each trial. If the rat did not find the platform within the allotted 3-minute time limit, the experimenter guided the rat to the nearest platform. Once a platform was located, the rat remained on it for 15 seconds before being returned to its heated testing cage for a 30-second inter-trial-interval (ITI). During the ITI, the experimenter removed the just-found platform from the maze (not replaced with a daily testing session), removed any debris, and stirred the water to distribute potential olfactory cues. Following 12 days of baseline testing, on days 13 and 14, a 4-hour delay was implemented between trials 2 and 3 to evaluate memory retention after a delay. Arm entry errors prior to locating a platform were recorded for each trial on the testing sheet by the experimenter, defined as the tip of the rat's snout passing a line 11 cm into the arm (visible to the experimenter outside of the maze, but not visible to the rat). Three error types were recorded. Working memory correct (WMC) errors were entries into an arm that previously contained a platform within a day (trials 2-4). Reference memory (RM) errors were first entries into an arm that never contained a platform. Working memory incorrect (WMI) errors were subsequent entries within a day into an arm that never contained a platform. The WRAM was defined as a high cognitive demand spatial working and reference memory task because the number of locations needed to be recalled increases as trials progress, thus progressively taxing working memory load capacity across trials within each day.

2.6 ∣. DMS water maze

The DMS was a water escape task that evaluated spatial working and recent memory.38 The apparatus had four equally sized and spaced arms (each arm 38.1 cm × 12.7 cm), configured as a plus shape, radiating out from a circular centre. Salient spatial cues were placed on the walls and around the room to aid spatial navigation. A single platform was submerged 2-3 cm below the surface of the water in one of the four arms. The platform remained in the same location within a day for all rats, and the platform location changed across days. With this protocol, rats must update their working memory to go to the newly learned location within each day, thus breaking the association with the rewarded place in space from the previous day. However, working memory was not increasingly taxed with DMS because there was only one item of updated information (ie, the constant daily location of the one platform) to retain in a given testing session. Each rat experienced six trials per day for 10 days. The first 8 days were considered baseline testing. The first trial of each day was operationally defined as an information trial in which the rats were exposed to the new platform location. Trial 2 was considered the working memory trial, and trials 3-6 were recent memory trials, where rats must update and retain information about the current platform escape location. Rats were dropped off in one of two alternating non-platformed start arms that were not directly across from the platform location, such that each rat was required to make a series of left and right turns to locate the platform. The order in which drop-off location points occurred was semi-random so that there was no consistent pattern of left and right turns within a day or across days. Each trial had a maximum 90-second swim time before the experimenter led the rat to the platform. Once found, the rat remained on the platform for 15 seconds before being returned to its heated testing cage for a 30-second ITI, during which the experimenter removed any debris from the maze and stirred the water to obscure potential olfactory cues. After eight days of baseline testing was completed, a 4-hour delay was implemented between trials 1 and 2 for days 9 and 10 to test delayed memory retention for the new platform location each day. An arm entry was recorded when the tip of rat's snout passed the 11 cm mark into a given arm. Total entry errors into non-platformed arms on each trial prior to locating the platform were calculated. The DMS water maze was defined as a low cognitive demand spatial memory task because, although information needed to be updated across days (requiring working memory), the task did not involve an increasing working memory load component within or across days.

2.7 ∣. Body weights

Body weights (grams) were recorded at baseline (ie, prior to OVX surgery), at pump insertion surgery (ie, 2 weeks after OVX), prior to behaviour (ie, 2 weeks after pump insertion) and at euthanasia.

2.8 ∣. Euthanisation

Rats were euthanised 1 day after the completion of their respective maze tasks, and were approximately 13 months of age at this time point. Subjects were deeply anaesthetised using inhaled isoflurane anaesthesia and decapitated. After confirming successful OVX, the uterine horns were removed from the body cavity, trimmed of excess fat, and wet weight was collected for each subject. Osmotic pumps were removed from the dorsal subcutaneous space and inspected for pump integrity.

2.9 ∣. Statistical analysis

All data analyses were completed using Statview statistical soft-ware. Given that our primary question was whether prior maze-induced cognitive experience impacts later cognitive abilities for animals with no, low, or high exogenous E2 exposure, separate analyses were completed for vehicle, low-E2 and high-E2 treatment groups. Repeated measures ANOVAs were utilised for WRAM and DMS data. The independent variable within each analysis was experience (naïve, low-demand or high-demand). For WRAM data analyses, “low-demand-experience” refers to prior testing on the DMS before exposure to WRAM testing, and “naïve” refers to the respective groups’ first exposure to a maze task. For DMS data analyses, “high-demand-experience” refers to prior testing on the WRAM before exposure to DMS testing, and “naïve” refers to the respective groups’ first exposure to a maze task. As an additional question that would more directly allow assimilation of our findings into the prior maze literature testing memory in naïve rats treated with E2, we evaluated the effect of treatment in naïve rats only for each task. The repeated measures were trials nested within days. The dependent variable was errors; for WRAM, this included analyses for WMC, WMI, and RM errors, and, for DMS, this comprised a total error analysis. ANOVAs were utilised to assess body weights and uterine weights, with treatment as the independent variable and body weight or uterine weight as the dependent variable, respectively. All analyses were two-tailed and the alpha level was set at 0.05. Results were deemed marginal if the P value was between 0.05 and 0.10 to acknowledge trends that may be observed within and between laboratories investigating similar research queries.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. WRAM

WRAM data were divided into two blocks: days 1-6 were considered the learning phase of the task wherein the rats were learning the rules of the task, and days 7-12 were considered the asymptotic phase of the task, where rats were performing to the best of their ability and exhibited steady-state performance. These blocks were chosen based on the trajectory of the subjects’ learning curves in this experiment; additionally, we have previously reported cognitive effects when WRAM data were evaluated using similar blocks with age-matched rat models of menopause.13,45-58-59 Furthermore, such data blocking was the optimal way to indirectly compare WRAM and DMS data in this experiment. That is, in DMS, day 1 was analyzed separately, such that each rat had six exposures to the same platform location. Because WRAM requires that subjects find a combination of four platform locations per day, assessing performance on days 1-6 for WRAM provides a comparable six-exposures to each platform location as was completed on day 1 of DMS. Similarly, the latter half of testing (days 7-12) was blocked after rats learned the rules of the task, comparable to the days 2-8 blocking structure in the DMS.

Of note, benefits of E2 treatment may not be readily apparent when there is a low working memory demand, nor when performance is averaged across low and high working memory loads.13 Prior findings in our laboratory have shown that group differences typically become evident on the WRAM when working memory load is highly taxed, during moderate to high working memory load trials. Therefore, we performed separate evaluations for WMC errors on trials 3 and 4 alone, the moderate and maximum working memory load trials respectively, as performed previously.42,58-60-63

3.1.1 ∣. Effects of low-demand experience on WRAM performance

For the learning phase (days 1-6), there were no main effects or interactions of low-demand-experience for the vehicle treated rats, the low-E2 treated rats, or the high-E2 treated rats for WMC, WMI, or RM errors (data not shown).

For the asymptotic phase (days 7-12), there was a marginal main effect of low-demand-experience for WMC for the vehicle rats (F1,19 = 3.23, P = 0.09) (Figure 1A) and the high-E2 rats (F1,17 = 3.69, P = 0.07) (Figure 1C), whereby the non-significant trend suggested rats with prior low-demand-experience tended to make more errors than their naïve counterparts. There was no main effect or interaction for WMC errors for the low-E2 treated rats during the asymptotic phase collapsed across all trials (Figure 1B). When trial 3, the moderate working memory load trial, was evaluated independently, for the vehicle treated rats there was no difference between the naïve group and low-demand-experience group for WMC errors (Figure 1D). However, for the low-E2 treated rats, there was a main effect of low-demand-experience on trial 3 (F1,18 = 10.69, P < 0.01), such that low-demand-experience low-E2 treated rats made fewer WMC errors than naïve low-E2 treated rats, indicating that low-E2 treatment enhanced memory with a moderate working memory load only when subjects had prior low-demand-experience (Figure 1E). Interestingly, for the high-E2 treated rats, there was a marginal main effect of low-demand-experience on trial 3 (F1,17 = 3.59, P = 0.08), such that high-E2 treatment tended to have an impairing effect on the moderate working memory load trial when subjects had low-demand-experience (Figure 1F). There were no main effects for trial 4, the maximum working memory load trial, indicating that the WRAM task was sufficiently difficult on the highest working memory load trial to impair all groups, an effect we have previously observed with middle-aged intact rats.58 There were no main effects or interactions across all trials for WMI errors, nor were there high-working memory load trial-specific effects for WMI. Likewise, there were no main effects of low-demand-experience for RM errors in any treatment group.

FIGURE 1.

Water radial-arm maze task (WRAM) asymptotic phase performance. A-C, Working memory correct (WMC) errors across trials 2-4 of the asymptotic phase for vehicle, low-17β-oestradiol (E2), and high-E2 groups. Solid lines represent naïve subjects in each treatment group, and dashed lines represent low-demand experience subjects in each treatment group. D-F, WMC errors on the moderate working memory load trial (trial 3) only during the asymptotic phase. The low-E2 group with prior low-demand experience exhibited enhanced performance compared to the naïve low-E2 group. There was trend where the high-E2 treated group with prior low-demand experience tended to make more errors on the moderate working memory load trial the naïve high-E2 group, although this effect was statistically marginal. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, #P < 0.10. Naïve vehicle, n = 10; naïve low-E2, n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 9; low-demand experience vehicle, n = 11; low-demand experience low- E2, n = 10; low-demand experience high-E2, n = 10

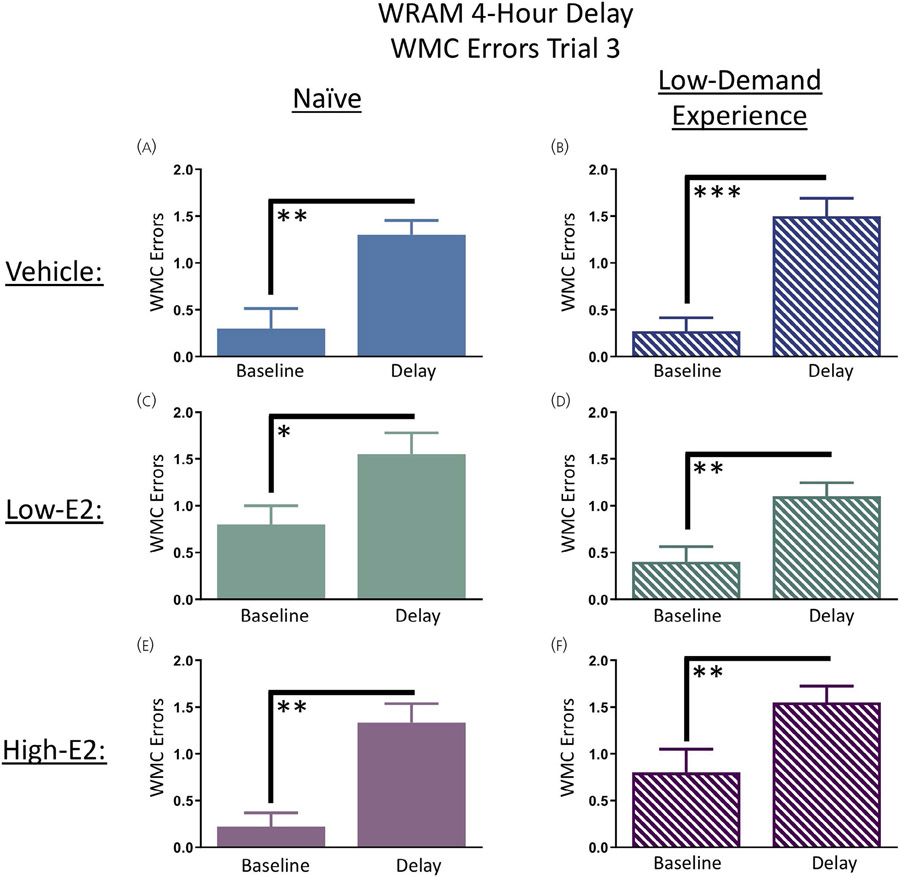

On days 13 and 14 of WRAM testing, rats were given a 4-hour delay between trials 2 and 3. Each treatment group was assessed separately to evaluate individual group performance on trial 3 of day 12 (the last day of baseline WRAM testing) versus the average of trial 3 following both 4-hour delays (days 13 and 14). For WMC errors, there was a main effect of delay day for the naïve vehicle group (F9,1 = 12.86, P < 0.01), the low-demand-experience vehicle group (F10,1 = 23.07, P < 0.001), the naïve low-E2 group (F9,1 = 7.11, P < 0.05), the low-demand-experience low-E2 group (F9,1 = 14.23, P < 0.01), the naïve high-E2 group (F8,1 = 18.18, P < 0.01) and the low-demand-experience high-E2 group (F9,1 = 16.2, P < 0.01), such that all groups, regardless of treatment or prior low cognitive demand maze experience, made more WMC errors on trial 3 following a 4-hour delay in the WRAM (Figure 2A-F).

FIGURE 2.

Water radial-arm maze task (WRAM) delayed memory retention. A-F, Following a 4-hour delay between trials 2 and 3, all subjects, regardless of treatment group and prior experience, made more working memory correct (WMC) errors on trial 3 after the delay (day 13 + 14) compared to trial 3 WMC performance on the last day of baseline testing (day 12). Solid bars represent naïve subjects in each treatment group, and dashed bars represent low-demand experience subjects in each treatment group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Naïve vehicle, n = 10; naïve low-17β-oestradiol (E2), n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 9; low-demand experience vehicle, n = 11; low-demand experience low-E2, n = 10; low-demand experience high-E2, n = 10

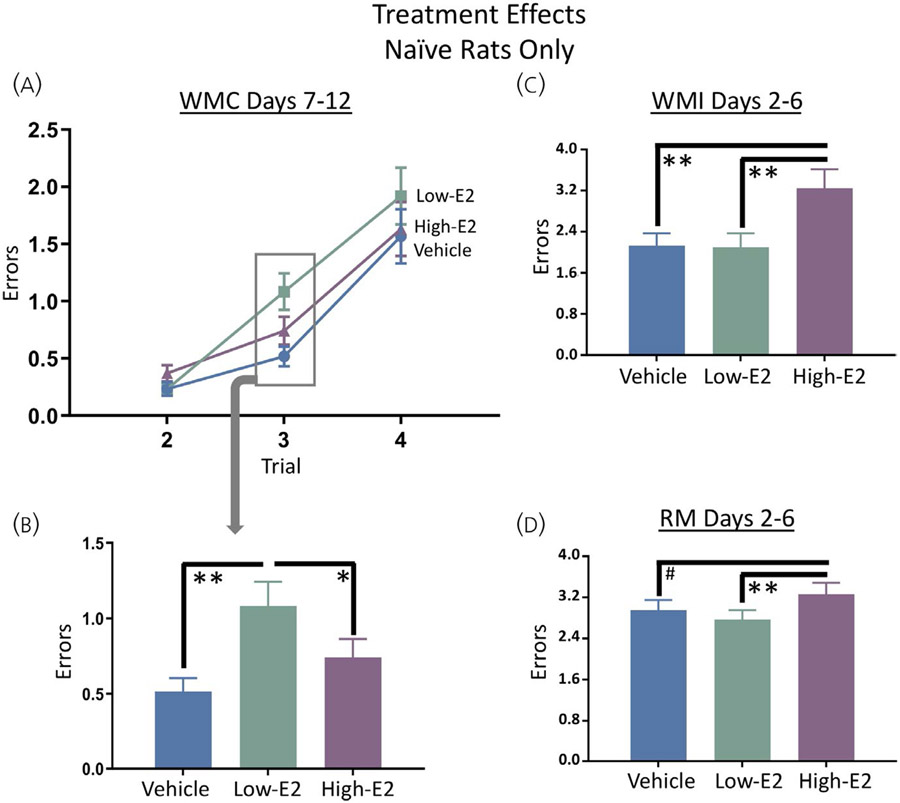

3.1.2 ∣. Hormone treatment effects in naïve subjects only

For rats with no prior testing experience, there were no main effects or interactions with treatment during the learning phase. During the asymptotic phase (Figure 3A), there was a main effect of treatment for WMC errors on trial 3 only for naïve rats (F2,26 = 6.48, P < 0.01). The low-E2 group made more WMC errors on the moderate working memory load trial compared to the vehicle group (Fisher's post-hoc least significant difference [PLSD]: P < 0.01) and the high-E2 group (Fisher's PLSD: P < 0.05) groups (Figure 3B). Of note, in the current study day 1 was included in the analysis of experience effects to determine whether there was a transfer of prior cognitive practice to the new task; however, we typically remove day 1 of the WRAM from analysis for naïve subjects.45,64,65 This is because day 1 is the first exposure to this task and it typically represents exploration instead of working memory as this is the initial introduction to the win-shift rule associated with this specific WRAM protocol. Thus, to permit interpretation relative to prior and future studies, we performed an additional analysis excluding day 1 for naïve subjects only, thereby assessing days 2-6. There was a treatment main effect for WMI errors (F2,57 = 4.95, P < 0.05); the high-E2 group made more WMI errors compared to the vehicle group (Fisher's PLSD: P < 0.01) and the low-E2 group (Fisher's PLSD: P < 0.01) for days 2-6 (Figure 3C). There was also a treatment main effect for RM (F2,57 = 4.32, P < 0.05), whereby high-E2 rats made more RM errors compared to low-E2 rats (Fisher's PLSD: P < 0.01). Although a trend suggested that high-E2 treated rats tended to make more RM errors compared to vehicle treated rats, this comparison did not reach statistical significance (Fisher's PLSD: P = 0.07) (Figure 3D). When the moderate and maximum working memory load trials were assessed separately, a marginal treatment main effect was present for WMI errors on trial 4 (F2,26 = 2.81, P = 0.08), with high-E2 treated rats having a higher mean, and low-E2 treated rats a lower mean, than vehicle treated rats; however, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the marginal nature of the findings.

FIGURE 3.

Treatment effects in naïve rats in the water radial-arm maze task (WRAM). A, B, During the asymptotic phase, the naïve low-17β-oestradiol (E2) group made more working memory correct (WMC) errors when working memory load was moderately taxed compared to naïve vehicle and naïve high-E2 groups. Further analysis of the learning phase excluding day 1, the first introduction to the maze, revealed that the naïve high-E2 group had impaired (C) working memory (WMI) and (D) reference memory (RM) compared to naïve vehicle and naïve low-E2 groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, #P < 0.10. Naïve vehicle, n = 10; naïve low-E2, n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 9

3.2 ∣. DMS water maze

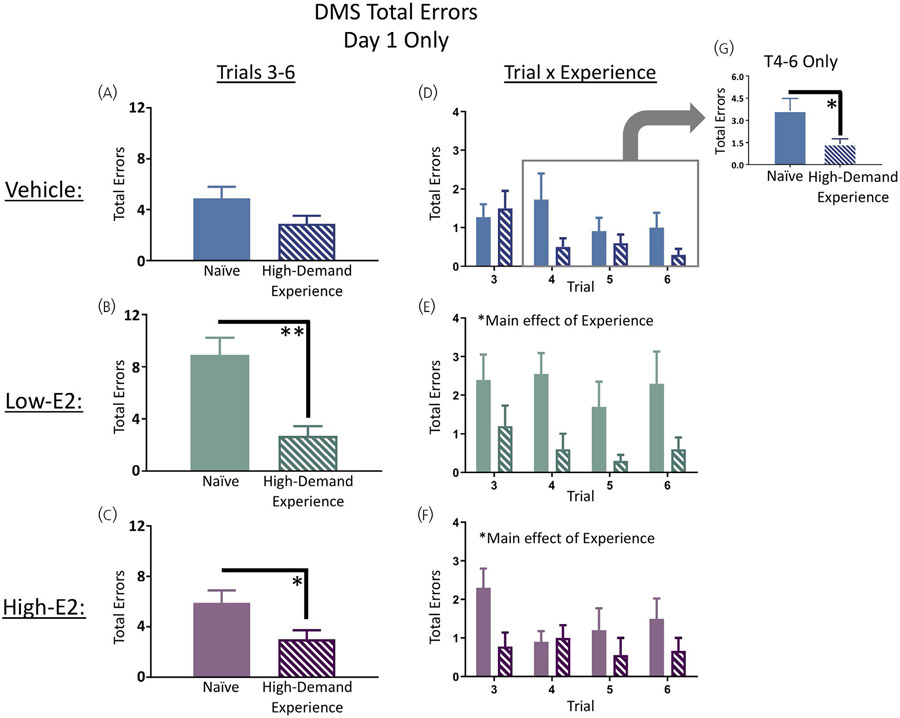

As noted above, day 1 of DMS was analysed separately within each treatment group so that we could evaluate the effect of high-demand-experience (that is, the effect of prior testing experience on the WRAM) on the first exposure to the DMS, a low cognitive demand working memory task. For each treatment group, performance on the recent memory trials, trials 3-6, were analysed on day 1, aiming to assess performance after two exposures to reinforcement at the same location in space (ie, the rat is removed from the water and placed into the heated testing cage as a result of locating the platform). For the vehicle treated rats, there was no difference between naïve rats and high-demand-experience rats on trials 3-6 (Figure 4A). There was a main effect of high-demand-experience for low-E2treated rats (F1,18 = 11.12, P < 0.01) (Figure 4B), as well as for high-E2treated rats (F1,17 = 4.49, P = 0.049) (Figure 4C), with low- or high- E2 treated high-demand-experience rats making fewer errors than their naïve counterparts for trials 3-6 on day 1 of DMS testing. It is notable that, upon visualising errors on each trial (Figure 4D-F), vehicle treated rats with high-demand experience did appear to perform better than vehicle treated naïve counterparts on trials 4-6. Therefore, we made a post-hoc decision to evaluate trials 4-6 on day 1 for the vehicle treated group; there was a significant effect of high-demand-experience (F1,19 = 4.65, P < 0.05), where high-demand-experience vehicle treated rats made fewer errors than naïve vehicle treated rats on trials 4-6 (Figure 4G).

FIGURE 4.

Delayed match-to-sample (DMS) day 1 only performance. Low-17β-oestradiol (E2) (B, E) and high-E2 (C, F) treated rats with prior high-demand experience made fewer errors than their naïve counterparts on trials 3-6 of DMS. A, D, G, Post hoc analysis of later trials within the first session of DMS (trials 4-6) revealed vehicle treated rats with high-demand experience made fewer errors than naïve vehicle treated rats, indicating that even with high-demand experience, ovariectomised (OVX) rats without exogenous E2 treatment required an additional platform location exposure before exhibiting enhanced performance compared to OVX rats naïve to behaviour testing. Solid bars represent naïve subjects in each treatment group, and dashed bars represent low-demand experience subjects in each treatment group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Naïve vehicle, n = 11; naïve low-E2, n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience vehicle, n = 10; high-demand experience low-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience high-E2, n = 9

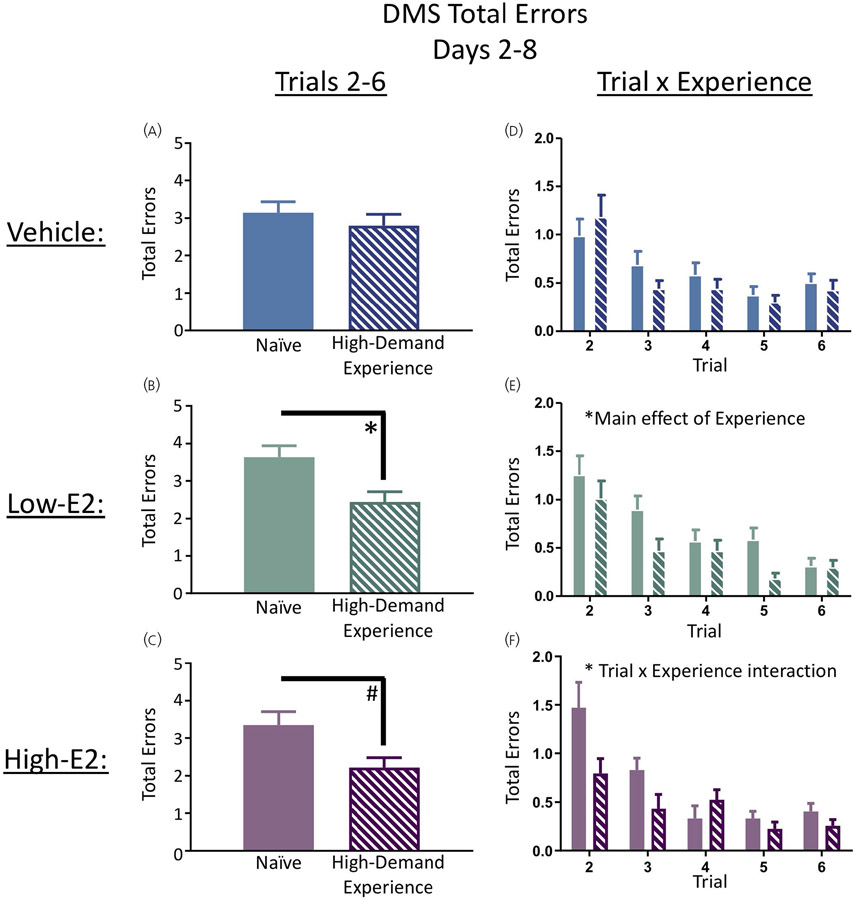

Days 2-8 of DMS were analysed within each vehicle or hormone-treated group for trials 2-6 (working plus recent memory trials). Performance of vehicle treated rats with high-demand-experience did not differ from naïve vehicle treated rats for the remainder of the baseline days, indicating that high-demand-experience did not impact performance in OVX rats administered vehicle treatment (Figure 5A,D). There was a main effect of high-demand-experience for the low-E2 treated rats (F1,18 = 6.00, P < 0.05) whereby high-demand-experience rats treated with low-E2 made fewer errors than naïve rats treated with low-E2 (Figure 5B,E), suggesting that prior high-demand experience enhanced performance on the DMS when low-E2 treatment was administered. There was a marginal main effect of high-demand-experience for the high-E2 group (F1,17 = 3.69, P = 0.07), where high-demand-experience rats treated with high-E2 tended to make fewer errors than naïve rats treated with high-E2, suggesting a subtle, but not statistically significant, enhancement in performance on the DMS for high-E2 treated rats with prior high-demand cognitive experience across all trials (Figure 5C). There was, however, a significant high-demand-experience × trial interaction for the high-E2 group (F4,68 = 2.93, P < 0.05) (Figure 5F), with the benefit of high-demand experience appearing to be most prominent on trial 2, when the platform location is being updated, requiring working memory. Collectively, these results indicate that high-demand cognitive experience was most beneficial to subsequent DMS performance when E2 was present after OVX, particularly with the low-E2 dose. Of note, we separately evaluated trials 3-6 for days 2-8 to assess whether these effects were carried by trial 2, the working memory trial. When trial 2 was excluded from each analysis, the same effects remained for each group, indicating that the effects were not specifically carried by the working memory trial (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Delayed match-to-sample (DMS) performance days 2-8. A-F, High-demand experienced rats treated with low-17β-oestradiol (E2) exhibited enhanced performance on trials 2-6 across all baseline testing days compared to naïve counterparts. There was a trial × experience interaction for the high-E2 treated groups where high-E2 rats with prior experience made fewer errors on earlier trials compared to naïve counterparts. Solid bars represent naïve subjects in each treatment group, and dashed bars represent low-demand experience subjects in each treatment group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.10. Naïve vehicle, n = 11; naïve low-E2, n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience vehicle, n = 10; high-demand experience low-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience high-E2, n = 9

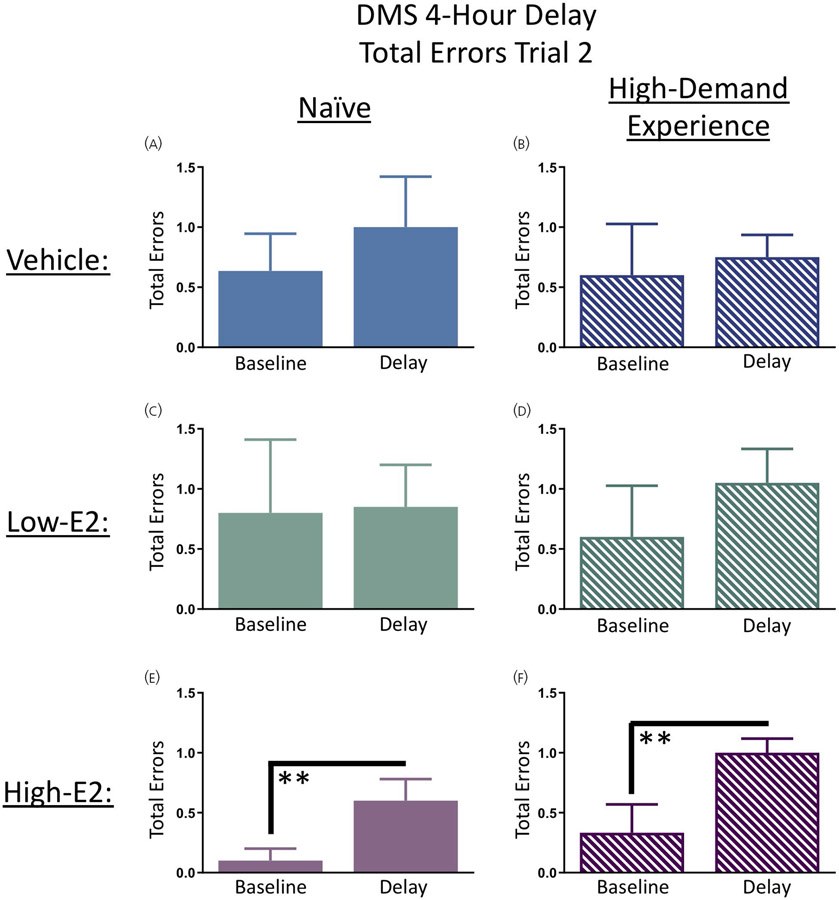

On days 9 and 10 of DMS testing, rats were given a 4-hour delay between the information trial (trial 1) and the working memory trial (trial 2). Each treatment group was analysed separately to assess performance on trial 2 of day 8 (the last day of baseline testing) compared to the average of trial 2 following both 4-hour delays (days 9 and 10). There were no differences between baseline and delay days for the naïve vehicle group, the high-demand-experience vehicle group, the naïve low-E2 group, or the high-demand-experience low-E2 group (Figure 6A-D). However, there was a main effect of delay day for the naïve high-E2 rats (F9,1 = 11.25, P < 0.01) and for the high-demand-experience high-E2 rats (F8,1 = 10.67, P < 0.01), such that number of errors committed in the DMS task by high-E2 treated rats increased with this elevated 4-hour long temporal retention requirement; this impairment was apparent regardless of whether rats had prior high-demand cognitive experience or whether DMS was their first maze experience (Figure 6E-F).

FIGURE 6.

Delayed match-to-sample (DMS) delayed memory retention. A-D, Four-hour delays between trials 1 and 2 did not significantly impact vehicle treated rats or low-17β-oestradiol (E2) treated rats regardless of prior testing experience. E, F, High-E2 treated rats committed more total errors prior to locating the platform on the post-delay trial compared to baseline. This observation is likely resultant of lower errors on the last day of baseline testing, which exacerbated the observed difference in error scores on the post-delay trial. Solid bars represent naïve subjects in each treatment group, and dashed bars represent low-demand experience subjects in each treatment group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01. naïve vehicle, n = 11; naïve low-E2, n = 10; naïve high-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience vehicle, n = 10; high-demand experience low-E2, n = 10; high-demand experience high-E2, n = 9

3.2.1 ∣. Hormone treatment effects in naïve subjects only

For rats that had not received prior testing, there were no main effects or interactions with treatment on day 1 only, nor on days 2-8, of the DMS task; since this was demonstrated for every treatment group, it can be interpreted that naïve rats show comparable DMS performance regardless of exogenous E2 treatment, within the parameters administered in the current experiment, after OVX (data not shown).

3.3 ∣. Physiological indicators of E2 treatment: vaginal smears, body weights and uterine weights

Prior to osmotic pump insertion, all rats exhibited dioestrus-like smears characterised by leukocytes but with more scarcity of cells compared to an ovary-intact dioestrus smear, indicating successful ovary removal. As anticipated after pump insertion, E2-treated rats exhibited oestrus-like smears containing cornified cells, whereas vehicle treated rats continued to display dioestrus-like or blank vaginal smears.

Regarding body weight, across time, there was a main effect of measurement time point (F3,171 = 83.38, P < 0.0001), as well as a measurement time point × treatment interaction (F6,171 = 30.04, P < 0.0001). At baseline, prior to OVX surgery, there were no group differences in weight, nor were there group differences prior to pump insertion. However, body weight increased in all rats between OVX and pump insertion time points (F1,58 = 161.18, P < 0.0001). Prior to commencement of behaviour testing, 2 weeks after pump insertion, there was a main effect of treatment (F2,58 = 9.72, P < 0.001); a Fisher's PLSD post hoc test revealed that the low-E2 group (P < 0.0001) and the high-E2 group (P < 0.0001) weighed less than the vehicle treated group. Body weights in the low-E2 and high-E2 groups did not differ from each other. At euthanasia, there was also a main effect of treatment (F2,57 = 9.93, P < 0.001); a Fisher's PLSD post hoc test revealed that the low-E2 group (P < 0.0001) and the high-E2 group (P < 0.0001) weighed less than the vehicle treated group, although the oestrogen-treated groups did not differ from each other (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7.

A, Body weights. Body weight (g) increased for all subjects between ovariectomy (OVX) and pump insertion time points. Following vehicle or 17β-oestradiol (E2) treatment initiation, OVX rats treated with low-E2 or high-E2 decreased body weights compared to OVX-vehicle treated rats. This difference persisted through the end of the experiment. B, Uterine wet weights at euthanasia. All groups were OVX. The low-E2 and high-E2 treated rats exhibited significantly heavier uterine wet weights at death compared to the vehicle treated rats, but there was no statistical difference in weight between E2 groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ****P < 0.0001. Vehicle, n = 21; low-E2, n = 20; high-E2, n = 19

Uterine wet weights were collected at euthanasia. As expected, there was a main effect of treatment (F2,54 = 26.28, P < 0.0001). Fisher's PLSD post hoc tests indicated that uteri from the vehicle treated group weighed significantly less than those of the low-E2 group (P < 0.0001) and the high-E2 group (P < 0.0001) (Figure 7B). Uterine weight did not differ between low- and high- E2 treated groups.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Cognitive practice is considered neuroprotective and can impart benefits in acquiring and remembering novel information. Whether oestrogen milieu interacts with prior cognitive experience or cognitive reserve to influence outcomes is an area of substantial interest from both basic science and translational clinical perspectives. In the present study, we evaluated whether prior experience on a low cognitive demand maze task (the DMS, testing spatial working memory without an increasing memory load component) or a high cognitive demand maze task (the WRAM, testing spatial working and reference memory requiring maintenance of an increasing multi-item working memory load) affected the ability to learn the subsequent cognitive task, and whether E2 milieu impacted outcomes, during middle age. The administered E2 doses of low (2 μg/day) and high (4 μg/day) were selected to produce physiologically relevant circulating levels of E2 following OVX, based on serum levels reported in prior rat studies.44,46,49-50 The low-E2 dose, which had the most favorable cognitive-behavioural effects overall related to experience in this experiment, corresponds to physiological E2 levels expected in a regularly cycling rat and best compliments the current standard recommendations for oestrogen-containing menopausal hormone therapy in women. Although hormone therapy dosage may vary based on the treatment indication, in general, the lowest effective dose of oestrogen, often in a non-oral administration route (such as a transdermal patch, vaginal application, or intrauterine device), is recommended to produce physiologically relevant circulating E2 levels that concomitantly minimises health risks. Overall, we report that prior experience on tasks of varying complexity altered learning and/or memory for the subsequent maze task, and these effects were further influenced by exogenous E2 treatment.

4.1 ∣. Low-demand experience impacts subsequent high-demand working memory performance only with oestrogen supplementation

Prior experience on a low cognitive demand spatial working memory task did not impart benefits when subsequently learning a more cognitively demanding spatial working memory task, and this lack of benefit from a low cognitive demand task did not differ with E2 treatment. However, E2 treatment did impact whether prior low cognitive demand experience affected subsequent ability to handle a higher memory load on a high cognitive demand task at the end of testing, after task rules had been learned. Specifically, experience on the low cognitive demand spatial working memory task in combination with low-E2 treatment enhanced the subsequent ability to handle a moderately high working memory load on the more cognitively demanding task compared to naïve rats with this same low-E2 treatment. Analysis of treatment effects in the rats that had not been previously behaviourally tested exhibited increased working memory errors on the moderate working memory load trial with low-E2 treatment compared to the vehicle and high-E2 treatments. Thus, an alternate explanation for the observed profile of experience-induced effects within the low-E2 group could be that prior low cognitive demand experience attenuates E2-induced impairments in naïve rats in the latter portion of testing. We recently reported a similar pattern of effects using a transitional menopause model with behaviourally naïve rats administered a comparable E2 regimen; working memory enhancements were evident during the initial learning portion, although some impairments were seen during the latter testing portion in the WRAM.45 Collectively, the data suggest that the biological processes underlying learning and working memory recall are differentially affected by exogenous E2 administration, particularly when treatment occurs in middle age following surgical or transitional reproductive senescence. Although trends suggested an impact of prior maze experience in OVX rats that were not administered E2, or OVX rats that were treated with high-E2, these effects did not reach statistical significance as defined by the convention of P < 0.05.

There are direct neural connections and interactions between the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and hippocampus, and the presence of nuclear and membrane-bound oestrogen receptors in each of these brain regions is thought to be important for learning and memory.66 Thus, E2 has the potential to influence the capacity to successfully learn a new spatial task via updating rules associated with previously learned information via receptors within these circuits. That significant effects of prior maze experience were observed with one E2 dose, but not without E2 or a higher E2 dose, highlights the importance of considering dose when assessing and interpreting the impact of prior cognitive experience on subsequent cognitive outcomes. An imbalance of circulating E2 after surgical menopause, especially outside of the physiological range, may impair brain mechanisms involved in shifting to new rules without interference. Indeed, there are data showing that high or supra-physiological circulating E2 levels could negatively impact cognitive performance.29,67-69 Future explorations into the neural circuits and molecular mechanisms involved in these putative interactive and complex observations will permit deciphering the parameters of oestrogen actions on memory load, strategy shifting and prior cognitive experience in a systematic fashion.

4.2 ∣. High-demand experience enhances subsequent low-demand learning and recent memory performance with oestrogen supplementation

Prior experience on a cognitively challenging spatial working memory task bestowed beneficial effects for learning and memory on a subsequent low-demand cognitive task, particularly when E2 was present. Upon the first exposure to the low-demand DMS task, surgically menopausal rats treated with E2 that also had prior high-demand experience on the WRAM demonstrated enhanced learning compared to E2treated rats naïve to the DMS task on day 1. This was true when E2 was given at either dose after surgical menopause. Unlike the WRAM that necessitates a win-shift strategy within a day for successful performance, the DMS is a win-stay task where subjects are required to return to the same spatial location repeatedly within a daily session for successful performance. As a result, learning can be observed across trials for a single daily testing session for the DMS task, even within the first day of the task. As we have observed with a variety of maze tasks, a single analysis averaging across all trials within a day, or across blocks of days, has the potential to mask differences in learning curves related to the variable of interest.13,38 Thus, to further aid in understanding each group's performance, it was important to assess later trials for OVX-vehicle rats that demonstrated clear learning as indicated by reduced errors by the end of the daily session for the DMS. In this post-hoc analysis assessing learning in rats that were treated with vehicle only, we highlight that rats with prior high-demand experience did show an advantage on later trials of day 1 of the DMS task, even when E2 treatment was not administered. Although E2 treatment after OVX may aid in acquiring new task rules faster than if circulating E2 is not present in measurable quantities, it is noteworthy that performance was enhanced in all groups with prior high-demand experience on day 1 of the DMS, regardless of E2 exposure. Of note, the platform location changes across days in the DMS, which requires working memory updates without an increasing memory load component within each daily session. Only rats with prior experience requiring high-demand and E2 supplementation continued to show enhanced performance compared to naïve counterparts across subsequent days of the less complex DMS task, indicating that the prior cognitive experience aided in the capacity to update the daily platform location when E2 was present. In comparison, OVX rats that did not receive E2 treatment performed similarly across days 2-8, regardless of their prior experience profile, suggesting that prior cognitive experience and E2 status likely work in concert to produce the enhanced performance on the low-demand task.

That rats with prior high-demand cognitive experience treated with E2 showed enhanced performance compared to naïve rats treated with E2 on an earlier trial on day 1 (as well as consistently across the remaining days) of the DMS task could partly be a result of E2 influencing cognitive flexibility to shift from one set of task rules to another with less proactive interference for new rule learning. Both the WRAM and DMS task comprise hippocampal- and frontal cortex- dependent spatial working memory tasks that require communication between these two brain regions. Prior research using in vivo electrophysiological recordings in the mPFC and hippocampus indicated that muscimol-infusion-induced inhibition of the mPFC impaired learning a spatial reversal task compared to vehicle treated rats, and coordinated communication between the two brain areas was also reduced with mPFC inhibition.70 Furthermore, in OVX female mice, chemogenetic inhibition of the dorsal hippocampus and mPFC, together or independently, impaired spatial and episodic-like memory consolidation,71 and direct E2 infusion into the hippocampus regulated dendritic spine density locally, as well as in the mPFC via ERK1/2 and mTOR pathways, both of which are critical cellular signalling cascades for learning and memory consolidation.72 In the present study, E2 may have conferred an additive task acquisition benefit to the groups primed with high cognitive demand experience (requiring frontal cortex activation) to overcome the detrimental effects of OVX on memory via reciprocal actions between the hippocampus and frontal cortex. Indeed, although vehicle treated rats performed similarly across days 2-8 of DMS regardless of experience profile, the beneficial effects of prior high-demand experience in the E2treated rats persisted throughout the remainder of DMS testing compared to their naïve counterparts. Overall, rats that had prior experience on a high cognitive demand task and were also given E2 treatment, particularly at the low dose, exhibited enhanced learning and memory for a subsequent low cognitive demand task. Infusions of E2 into the mPFC of OVX rats have been reported to bias the use of a place strategy in lieu of a response strategy to solve a spatial task,73 and this strategy bias could be related to our findings that E2 treatment after OVX bestowed a cognitive benefit to high cognitive demand experienced rats in acquiring a novel spatial memory task. Interestingly, when a 4-hour memory retention test was implemented between the learning trial and the working memory trial on the low cognitive demand task, only the rats receiving high-E2-treatment – both naïve and those that had high cognitive demand task experience – made more errors on the post-delay working memory trial compared to their individual group performance on the last day the DMS. The dose of E2 could impact overall outcomes with and without prior cognitive experience on subsequent cognitive performance when delayed memory recall is required. Specifically, low E2 dose treatment yielded beneficial effects for learning and memory on a low cognitive demand task when there was a background of prior high-demand experience, and both low-E2 groups retained a similar performance level with and without a delayed memory retention challenge, regardless of prior experience. On the other hand, although high E2 dose treatment imparted learning and memory benefits on the low-demand DMS task when there was a background of prior high-demand experience, high-E2 rats exhibited more errors, interpreted as impaired memory retention, following a delay on the DMS compared to baseline performance. This latter effect could partly be a result of the high E2 group's strong performance at baseline when there was no delay. In addition, rats treated with high-E2 may have utilised a different task-solving strategy after the delay that led to increased errors compared to their individual baselines.

4.3 ∣. Peripheral markers of hormone manipulations

We utilised several physiological indicators to confirm successful surgical menopause and E2 treatment across the experiment. Although a limitation of this experiment is that serum E2 levels were not obtained following treatment, we based the utilised treatment doses on previously published literature with similar doses used in rat models of surgical menopause, and had several peripheral markers of E2 treatment in place to verify E2 stimulation.43-47 Rats treated with vehicle exhibited blank or dioestrus-like smears, indicative of successful ovary removal, and those treated with either E2 dose exhibited cornified smears, indicative of oestrogen stimulation of the vaginal epithelium. Vehicle treated rats gained weight following OVX, E2 attenuated OVX-induced body weight gain, and OVX rats maintained a higher weight than both E2treated groups through the end of the experiment. These OVX- and E2- induced body weight changes concur with other rat studies.17,42,74-77 In addition, confirming E2-induced stimulation, uterine weights were increased with both E2 doses compared to vehicle treatment.17,42,44-78 Because the peripheral markers utilised here did not detect dose-dependent differences between low-E2 and high-E2 treated groups, in future studies it would be beneficial to measure serum hormone levels and correlate these values with cognitive performance to further decipher effects related to E2 dose.

5 ∣. CONCLUSIONS

The present study demonstrates that E2 treatment following OVX, in combination with prior cognitive practice, benefits subsequent cognition of varying complexity. The benefits of prior cognitive task experience were most pronounced with low-dose E2 administration; indeed, the low E2 dose treatment utilised in this experiment yielded the broadest beneficial cognitive effects for subsequent learning and memory performance on mazes of varying complexity. Oestrogen administration following surgical menopause in middle age has shown mixed cognitive effects in both animal and human studies. Our findings suggest that hormone milieu does not impact cognitive outcomes in isolation, but it interacts with exposure to prior learning and cognitive practice. For rodent studies, this highlights that maze task order and complexity impact the mnemonic outcomes of E2 treatment. Many laboratories, including our own, implement a battery of tasks to evaluate various types of learning and memory, as well as anxiety-like, depressive-like, and exploratory behaviours. While one experimental resolution could be to counterbalance task testing order, our findings indicate that prior maze testing experience impacts subsequent task performance differently depending on both E2 milieu and task complexity. Therefore, counterbalancing task order may muddle treatment effects.

We have previously shown that for gonadally intact rats, intermittent, repeated training on a simple spatial task, the T-maze, can benefit learning future, novel tasks. Of note, the benefits of prior experience were specific to the experienced aged female rats relative to experienced aged male rats. One year after the first behavioural training on the simple T-maze, ovary-intact females with prior cognitive practice showed superior memory compared to naïve ovary-intact counterparts on untrained domains, including the high-demand WRAM and the reference memory Morris water maze (experienced in that order), as well as enhanced performance on the previously trained T-maze.39 In addition, the observed enhancement was not accounted for by the procedural components of testing and was only noted when there was prior training requiring some level of cognitive demand.39 The current experiment provides putative insight into why E2 treatment fails to consistently enhance performance across a battery of maze tasks. For example, E2 induced spatial working memory benefits on the WRAM, but it yielded no benefit to reference memory on the Morris water maze when it immediately followed the WRAM17,42,65; however, we have observed subtle E2 induced learning enhancements on the DMS when it followed the WRAM.65 It is also important to note that these E2-associated benefits may be specific to the spatial memory domain or hippocampal-dependent learning tasks, as previous studies have shown that acute E2 treatment after OVX biases the preferred learning strategy for spatial and non-spatial tasks,79 and that E2 dose can influence task-specific outcomes.69 These cumulative findings indicate that it is important to describe the previous behavioural experience animals have had when reporting experimental results, and also highlight the need to consider the use of multiple behavioural tasks when aiming to fully encompass the impact of experimental manipulations on learning and memory outcomes.

As the behavioural endocrinology field moves forward to translate preclinical findings to better cognitive health in women during ageing, it is important to consider histories of cognitive experience and oestrogenic milieu as putative mediating factors of efficacy of oestrogen treatments, rather than secondary nuances arising from the idiosyncrasies of preclinical rodent behavioural testing. Taking such considerations into account will clarify how factors such as enrichment, educational attainment, cognitive status, and cognitive reserve histories influence the impact of hormone therapies on cognitive and brain ageing in menopausal women.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding information: Dr Heather Bimonte-Nelson: NIA (AG028084), State of Arizona, Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS14-052688), NIH Alzheimer's Disease Core Center (P30AG019610), Arizona State University Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and Department of Psychology. Dr Stephanie Koebele: NIA (1F31AG056110).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data from this experiment are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367–429. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riedel BC, Thompson PM, Brinton RD. Age, APOE and sex: triad of risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;160:134–147. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan Mitchell E, Fugate Woods N. Midlife women’s attributions about perceived memory changes: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10(4):351–362. 10.1089/152460901750269670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber MT, Mapstone M. Memory complaints and memory performance in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2009;16(4):694–700. 10.1097/gme.0b013e318196a0c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber MT, Mapstone M, Staskiewicz J, Maki PM. Reconciling subjective memory complaints with objective memory performance in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2012;19(7):735–741. 10.1097/gme.0b013e318241fd22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilberman JM, Cerezo GH, Del Sueldo M, Fernandez-Pérez C, Martell-Claros N, Vicario A. Association between hypertension, menopause, and cognition in women. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17(12):970–976. 10.1111/jch.12643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unkenstein AE, Bryant CA, Judd FK, Ong B, Kinsella GJ. Understanding women’s experience of memory over the menopausal transition: subjective and objective memory in pre-, peri-, and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23(12):1319–1329. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rentz DM, Weiss BK, Jacobs EG, et al. Sex differences in episodic memory in early midlife: impact of reproductive aging. Menopause. 2017;24(4):400–408. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan KN, Derby CA, Gleason CE. Cognitive changes with reproductive aging, perimenopause, and menopause. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45:751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Im EO, Hu Y, Cheng CY, Ko Y, Chee E, Chee W. Racial/ethnic differences in cognitive symptoms during the menopausal transition. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41(2):217–237. 10.1177/0193945918767660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson VW. Memory at midlife: perception and misperception. Menopause. 2009;16(4):635–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh M, Meyer EM, Millard WJ, Simpkins JW. Ovarian steroid deprivation results in a reversible learning impairment and compromised cholinergic function in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 1994;644(2):305–312. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91694-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bimonte HA, Denenberg VH. Estradiol facilitates performance as working memory load increases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24(2):161–173. 10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heikkinen T, Puoliväli J, Liu L, Rissanen A, Tanila H. Effects of ovariectomy and estrogen treatment on learning and hippocampal neurotransmitters in mice. Horm Behav. 2002;41(1):22–32. 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heikkinen T, Puoliväli J, Tanila H. Effects of long-term ovariectomy and estrogen treatment on maze learning in aged mice. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39(9):1277–1283. 10.1016/j.exger.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace M, Luine V, Arellanos A, Frankfurt M. Ovariectomized rats show decreased recognition memory and spine density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2006;1126(1):176–182. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koebele SV, Nishimura KJ, Bimonte-Nelson HA, et al. A long-term cyclic plus tonic regimen of 17β-estradiol improves the ability to handle a high spatial working memory load in ovariectomized middle-aged female rats. Horm Behav. 2019;2020(118):104656. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2019.104656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: women’s health initiative memory study. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2959–2968. 10.1001/jama.291.24.2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in post-menopausal women. JAMA. 2003;289(20):2651–2662. 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coker LH, Espeland MA, Rapp SR, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cognitive outcomes: The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118(4–5):304–310. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wharton W, Gleason CE, Miller VM, Asthana S. Rationale and design of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) and the KEEPS Cognitive and Affective Sub Study (KEEPS Cog). Brain Res. 2013;1514:12–17. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaughan L, Espeland MA, Snively B, et al. The rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of Younger Women (WHIMS-Y). Brain Res. 2013;1514:3–11. 10.1016/j.brinres.2013.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS–cognitive and affective study. PLoS Medicine. 2015;12(6):1–25. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Lesnick TG, et al. Early postmenopausal transdermal 17β-estradiol therapy and amyloid-β deposition. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;53(2):547–556. 10.3233/JAD-160258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maki PM, Henderson VW. Hormone therapy, dementia, and cognition: the Women’s Health Initiative 10 years on. Climacteric. 2012;15(3):256–262. 10.3109/13697137.2012.660613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greendale GA, Huang MH, Wight RG, et al. Effects of the menopause transition and hormone use on cognitive performance in midlife women. Neurology. 2009;72(21):1850–1857. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a71193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinkerton JV, Sánchez Aguirre F, Blake J, et al. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):1–26. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turgeon JL, Carr MC, Maki PM, Mendelsohn ME, Wise PM. Complex actions of sex steroids in adipose tissue, the cardiovascular system, and brain: Insights from basic science and clinical studies. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(6):575–605. 10.1210/er.2005-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korol DL, Pisani SL. Estrogens and cognition: friends or foes?. An evaluation of the opposing effects of estrogens on learning and memory. Horm Behav. 2015;74:105–115. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koebele SV, Bimonte-Nelson HA. The endocrine-brain-aging triad where many paths meet: female reproductive hormone changes at midlife and their influence on circuits important for learning and memory. Exp Gerontol. 2017;94:14–23. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson RS, Wang T, Yu L, Grodstein F, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Cognitive Activity and Onset Age of Incident Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Neurology. 2021. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortimer JA, Graves AB. Education and socioeconomic determinants of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:S39–S44.8389010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp ES, Gatz M. The relationship between education and dementia an updated systematic review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(4):289–304. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c83c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Kim JK, Zhang YS, Sasson I, Hayward MD. Educational differences in the prevalence of dementia and life expectancy with dementia: changes from 2000 to 2010. Journals Gerontol Ser B. 2018;73(suppl_1):S20–S28. 10.1093/geronb/gbx135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crimmins EM, Saito Y.Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1629–1641. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00273-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyas SL, Salazar JC, Snowdon DA, et al. Transitions to mild cognitive impairments, dementia, and death: findings from the Nun study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(11):1231–1238. 10.1093/aje/kwm085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387–395. 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Daniel JM, Koebele SV. The mazes. In: Bimonte-Nelson HA, ed. The Maze Book: Theories, Practice, and Protocols for Testing Rodent Cognition, Vol. 94, 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer US; 2015:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talboom JS, West SG, Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Enders CK, Crain I, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Learning to remember: cognitive training-induced attenuation of age-related memory decline depends on sex and cognitive demand, and can transfer to untrained cognitive domains. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(12):2791–2802. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talboom JS, Williams BJ, Baxley ER, West SG, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Higher levels of estradiol replacement correlate with better spatial memory in surgically menopausal young and middle- aged rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90(1):155–163. 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Francis KR, Umphlet CD, Granholm AC. Progesterone reverses the spatial memory enhancements initiated by tonic and cyclic oestrogen therapy in middle-aged ovariectomized female rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(1):229–242. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prakapenka AV, Hiroi R, Quihuis AM, et al. Contrasting effects of individual versus combined estrogen and progestogen regimens as working memory load increases in middle-aged ovariectomized rats: one plus one does not equal two. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;64:1–14. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Tsang C, Nonnenmacher S, et al. Tonic Premarin dose-dependently enhances memory, affects neurotrophin protein levels and alters gene expression in middle-aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(4):680–697. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Talboom JS, Braden BB, et al. Continuous estrone treatment impairs spatial memory and does not impact number of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in the surgically menopausal middle-aged rat. Horm Behav. 2012;62(1):1–9. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koebele SV, Mennenga SE, Poisson ML, et al. Characterizing the effects of tonic 17β-estradiol administration on spatial learning and memory in the follicle-deplete middle-aged female rat. Horm Behav. 2020;126:104854. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mennenga SE, Bimonte-Nelson HA. The importance of incorporating both sexes and embracing hormonal diversity when conducting rodent behavioral assays. In: Bimonte-Nelson HA, ed. The Maze Book: Theories, Practice, and Protocols for Testing Rodent Cognition, 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer US; 2015:299–321. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long T, Yao JK, Li J, et al. Estradiol and selective estrogen receptor agonists differentially affect brain monoamines and amino acids levels in transitional and surgical menopausal rat models. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019;496:110533. 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibbs RB. Effects of estrogen on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons vary as a function of dose and duration of treatment. Brain Res. 1997;757:10–16. 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01432-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibbs RB. Long-term treatment with estrogen and progesterone enhances acquisition of a spatial memory task by ovariectomized aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(1):107–116. 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00103-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibbs RB. Effects of gonadal hormone replacement on measures of basal forebrain cholinergic function. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):931–938. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00433-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldman J, Murr A, Cooper R. The rodent estrous cycle: characterization of vaginal cytology and its utility in toxicological studies. Birth defects Res Part B. 2007;80:84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koebele SV, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Modeling menopause: the utility of rodents in translational behavioral endocrinology research. Maturitas. 2016;87:5–17. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bimonte HA, Hyde LA, Hoplight BJ, Denenberg VH. In two species, females exhibit superior working memory and inferior reference memory on the water radial-arm maze. Physiol Behav. 2000;70:311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bimonte HA, Granholm ACE, Seo H, Isacson O. Spatial memory testing decreases hippocampal amyloid precursor protein in young, but not aged, female rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;298:50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bimonte HA, Nelson ME, Granholm ACE. Age-related deficits as working memory load increases: relationships with growth factors. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(1):37–48. 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00015-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Singleton RS, Hunter CL, Price KL, Moore AB, Granholm A-CE. Ovarian hormones and cognition in the aged female rat: I. Long-term, but not short-term, ovariectomy enhances spatial performance. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117(6):1395–1406. 10.1037/h0087876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Singleton RS, Williams BJ, Granholm A-CE. Ovarian hormones and cognition in the aged female rat: II. Progesterone supplementation reverses the cognitive enhancing effects of ovariectomy. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(4):707–714. 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koebele SV, Mennenga SE, Hiroi R, et al. Cognitive changes across the menopause transition: a longitudinal evaluation of the impact of age and ovarian status on spatial memory. Horm Behav. 2017;87:96–114. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Braden BB, Andrews MG, Acosta JI, Mennenga SE, Lavery C, Bimonte-Nelson HA. A comparison of progestins within three classes: differential effects on learning and memory in the aging surgically menopausal rat. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322(Pt B):258–268. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braden BB, Kingston ML, Whitton E, Lavery C, Tsang CWS, Bimonte-Nelson HA. The GABA-A antagonist bicuculline attenuates progesterone-induced memory impairments in middle-aged ovariectomized rats. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:1–8. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Camp BW, Gerson JE, Tsang CWS, et al. High serum androstenedione levels correlate with impaired memory in the surgically menopausal rat: a replication and new findings. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36(8):3086–3095. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08194.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mennenga SE, Gerson JE, Koebele SV, et al. Understanding the cognitive impact of the contraceptive estrogen Ethinyl Estradiol: tonic and cyclic administration impairs memory, and performance correlates with basal forebrain cholinergic system integrity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;54:1–13. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koebele SV, Palmer JM, Hadder B, et al. Hysterectomy uniquely impacts spatial memory in a rat model: a role for the non-pregnant uterus in cognitive processes. Endocrinology. 2019;160:1–19. 10.1210/en.2018-00709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernaud VE, Hiroi R, Poisson ML, et al. Age impacts the burden that reference memory imparts on an increasing working memory load and modifies relationships with cholinergic activity. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hiroi R, Weyrich G, Koebele SV, et al. Benefits of hormone therapy estrogens depend on estrogen type: 17beta-estradiol and conjugated equine estrogens have differential effects on cognitive, anxiety-like, and depressive-like behaviors and increase tryptophan hydroxylase-2 mRNA levels in dorsal. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:1–20. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almey A, Milner TA, Brake WG. Estrogen receptors in the central nervous system and their implication for dopamine-dependent cognition in females. Horm Behav. 2015;74:125–138. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.010.Estrogen [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barha CK, Dalton GL, Galea LAM. Low doses of 17α-estradiol and 17β-estradiol facilitate, whereas higher doses of estrone and 17α- and 17β-estradiol impair, contextual fear conditioning in adult female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(2):547–559. 10.1038/npp.2009.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holmes MM, Wide JK, Galea LA. Low levels of estradiol facilitate, whereas high levels of estradiol impair, working memory performance on the radial arm maze. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116(5):928–934. 10.1037/0735-7044.116.5.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Galea LAM, Wide JK, Paine TA, Holmes MM, Ormerod BK, Floresco SB. High levels of estradiol disrupt conditioned place preference learning, stimulus response learning and reference memory but have limited effects on working memory. Behav Brain Res. 2001;126(1–2):115–126. 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00255-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guise KG, Shapiro ML. Medial prefrontal cortex reduces memory interference by modifying hippocampal encoding. Neuron. 2017;94(1):183–192.e8. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tuscher JJ, Taxier LR, Fortress AM, Frick KM. Chemogenetic inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex, individually and concurrently, impairs object recognition and spatial memory consolidation in female mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2018;156:103–116. 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]