Abstract

Background

Demand is increasing for youth-specific preference-based health-related quality-of-life measures for inclusion in evaluations of healthcare interventions for children and adolescents. The EQ-5D-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) has the potential to become such a preference-based measure.

Objective

This study applied the recently published EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol to develop a German EQ-5D-Y value set and explored the differences between values given to youth health by parents and non-parents.

Methods

To elicit EQ-5D-Y health state preferences, a representative sample of 1030 adults of the general population completed a discrete choice experiment (DCE) online survey, and 215 adults participated in face-to-face interviews applying composite time trade-off (cTTO). Respondents were asked to consider a 10-year-old child living in the health states. DCE data were modelled using a mixed logit model. To derive the value set, DCE latent scale values were anchored onto adjusted mean cTTO values using a linear mapping approach.

Results

Adult respondents considered pain/discomfort and feeling worried/sad/unhappy as the two most important dimensions in terms of youth health. Adjusted mean cTTO values ranged from − 0.350 for health state 33333 to 0.970 for health state 21111. The EQ-5D-Y value set showed a logical order for all parameter estimates, and predicted values ranged from − 0.283 to 1. Differences in preferences by parental status were mainly observed for cTTO results, where mean values were larger for parents than for non-parents.

Conclusions

Applying the valuation protocol, a German EQ-5D-Y value set with internally consistent coefficients was developed. This enables the instrument to be used in economic evaluations of paediatric healthcare interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40273-022-01143-9.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| When considering youth health, respondents from the German adult general public considered the health dimensions pain/discomfort and feeling worried/sad/unhappy as most important. |

| Following the international EQ-5D-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) valuation protocol, an EQ-5D-Y value set for Germany was developed, which now enables cost-utility analysis of paediatric healthcare interventions. |

Introduction

Economic evaluations compare the costs and benefits of healthcare approaches, applications, and technologies (hereafter, ‘healthcare interventions’). To measure benefit, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) are often used as a standard utility measure in cost-utility analyses (CUAs) [1]. In several countries, CUAs including QALYs are used to inform decision making in healthcare [1, 2]. QALYs combine health-related quality of life (HRQoL), obtained by direct or indirect valuation approaches, with length of life [3, 4]. CUAs of healthcare interventions for children and adolescents are less standardised than those for interventions for adults [5, 6]. This is because there is less consensus around how HRQoL should be measured and valued for children and adolescents.

A review in 2019 summarised all primary studies reporting health utilities for childhood conditions and identified various approaches that had been used in practice [3]. In general, indirect valuation approaches are seen as advantageous as they use standardised generic preference-based HRQoL instruments with corresponding value sets to obtain a single utility for each health state to be used in QALY calculations [1, 4]. Several such instruments have been designed for younger populations. However, some were designed only for specific age groups (e.g. 16D for adolescents aged 12–15 years, 17D for children aged 8–11 years, and Assessment of Health Utility Measurement for adolescents aged 12–18 years) or have unclear age ranges and are relatively long (e.g. Assessment of Quality of Life 6 Dimension (AQoL-6D), which has 20 items, and the Quality of Well-Being scale (QWB), which asks about three dimensions and 58 symptoms) [4, 6]. Hence, the number of generic preference-based HRQoL instruments applicable to a broad age range in children and adolescents is limited, and there is no widely used child-specific instrument [4, 6, 7].

The generation of value sets for youth-specific1 HRQoL instruments is a more recent development that follows a debate on methodological and conceptual issues of valuation studies for paediatric instruments. The discussion is first and foremost about whose values should be considered: those of the adult general public, of parents, or of children and adolescents themselves [6, 7]. Studies show differences in the values given to child health by the adult general public and parents [8, 9] and between those given by adults and adolescents [10, 11]. The most suitable elicitation methods and perspectives in valuation tasks have also been discussed [4, 6, 7].

The EQ-5D-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) is a short generic instrument developed by the EuroQol Group to measure HRQoL in children and adolescents aged 8–15 years as an equivalent to the adult instrument EQ-5D-3L (three-level version of EQ-5D). It consists of five dimensions: mobility (MO), looking after myself (SC), doing usual activities (UA), having pain/discomfort (PD), and feeling worried/sad/unhappy (AD), with each dimension specifying three levels of severity: no problems/not (level 1), some problems/a bit (level 2), and a lot of problems/very (level 3)2 [12–14]. The adult instruments are widely used to assess HRQoL and calculate QALYs in economic evaluations, and—with its similar structure—the EQ-5D-Y also has the potential to be used [2, 7, 15]. However, very few EQ-5D-Y value sets currently exist [12, 16, 17]. As previous studies have shown that health state values for adults and children differ, value sets for adult instruments should not be used to calculate EQ-5D-Y-based utilities. Instead, separate value sets are necessary [18, 19]. Based on results of explorative studies testing different approaches of valuing EQ-5D-Y health states, a first international valuation protocol for EQ-5D-Y was recently published [20].

In Germany, no youth-specific HRQoL instrument is available that allows for utility calculation. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to develop a German value set for EQ-5D-Y—as one of the first national value sets—according to the methods proposed by the protocol to enable the use of the EQ-5D-Y as a utility measure. In addition, we explored differences in values given to child health states by parents and non-parents.

Methods

Data Collection

Data collection took place between November 2019 and July 2020. As suggested by the EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol, it was split in two sub-surveys to collect (1) discrete choice experiment (DCE) data via an online survey and (2) composite time trade-off (cTTO) data via interviews. Ethical approvals for both sub-surveys were received in Germany (Ethics Committee of Bielefeld University, No. EUB 2018-172 and EUB 2019-204).

Methods for Eliciting Health State Preferences

DCEs are used to assess the relative importance of dimensions and levels, and cTTO is used to rescale/anchor the latent scale DCE values on a scale from full health (1) to dead (0) [20]. The DCE task uses pairwise comparisons. The respondent is asked to decide which out of two health states, A and B, is better (forced choice) [21, 22]. As we used neither a ‘duration’ attribute nor a comparison to the alternative ‘dead’ in our DCE, only latent scale values were produced. The cTTO identifies the number of life-years in full health at which the respondent is indifferent between a longer period of life-years with impaired health and a shorter life duration in full health. The respondent is asked to trade-off life-years. In cTTO, the conventional TTO is used to start the tasks for all health states. For health states that the respondent considers to be worse than being dead, lead-time TTO is used [23–25].

Health State Selection

The DCE design from the EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol is D-efficient and consists of 150 DCE pairs separated into ten blocks. A two-dimension overlap was used for all pairs, meaning that the health states in each pair differed in the levels of three dimensions, whereas the other two dimensions presented the same level [20]. Differences between health states were presented in bold font to reduce non-attendance. Further, level balance among blocks was ensured. In each block, the order of health state pairs was randomized, as well as the left/right presentation during the task. Each respondent completed 18 DCE tasks: 15 from the experimental design and three for quality control (QC) purposes (see Sect. 2.7).

The cTTO design included one block of ten health states, which were valued by each respondent. The design included three mild health states (11112, 11121, 21111), two moderate ones (22223, 22232), and five severe health states (31133, 32223, 33233, 33323, 33333) [20]. The order of health states was randomised for each participant.

Framing of Discrete Choice Experiment and Composite Time Trade-Off Tasks

In both valuation tasks, participants were asked to imagine a hypothetical 10-year-old child when valuing the health states. Therefore, the wording of the EQ-5D-Y proxy version 1 was used for the health states, which means only the part of the item describing the dimension and severity level, e.g. ‘no problems walking about’ was used (rather than ‘I have no problems walking about’) [12].

Interview Process

The online DCE survey consisted of the following elements:

Information sheet on the project aim and procedures

Consent

Demographic questions on age, gender, and region to inform the quota sampling

Self-reported EQ-5D-Y to familiarise respondents with the instrument

Three questions on experience with severe illness

18 DCE tasks (15 DCE tasks and three DCE tasks for QC)

Self-reported EQ-5D-5L

Socio-demographic and health-related questions

The cTTO data were collected via computer-assisted personal interviews using the EuroQol portable valuation technology (EQ-PVT). An interviewer guideline was prepared explaining the interviewer’s role, how to handle the software, and instructions to be given to the respondents. Each of the four interviewers attended a day-long training session and had to conduct three test interviews. The interviews consisted of the following3:

Welcome and study aim (information sheet obtained prior to the interview)

Written consent

Self-reported EQ-5D-Y to familiarise respondents with the instrument

cTTO wheelchair examples plus three cTTO practice states

Ten cTTO tasks

Feedback module

Debriefing questions

Socio-demographic questions and three questions on experience with severe illness

Self-reported EQ-5D-5L

Most of the cTTO interviews were conducted face to face; however, with the advent of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) pandemic, 32 interviews were conducted online using a video conference application to finish data collection.

Sample and Recruitment

For the DCE survey, we aimed for a sample of 1000 respondents from the adult general population in Germany recruited by an online panel of a market research agency. To facilitate a representative sample in terms of gender, age groups, educational level, and region (16 federal states in Germany), quota-based sampling was applied based on German official statistics [26].

For the cTTO interviews, we aimed for 200 respondents from the adult general population [20]. A convenience sample controlled in terms of gender and age groups was recruited. Respondents came from Bielefeld and surrounding areas and were mostly recruited by study team members as well as through advertisements in local newspapers. The interviews were conducted mainly at Bielefeld University. A small number of participants came from other German regions as some interviews were conducted online. All interview respondents received a €20 voucher.

Quality Control

To identify non-engaged respondents in the DCE online survey, two QC criteria were applied. First, we included three fixed dominant pairs in which one health state logically dominated the other. This enabled us to check choices for rationality and to identify respondents who seemed to have a low level of attentiveness to, engagement with, or understanding of the tasks or made irrational choices. The dominant pairs were presented at the beginning and end of the DCE tasks and at a random position in the middle. Respondents were excluded if they gave a wrong answer to at least two of the three dominant pairs. The dominant pairs were excluded from the modelling analysis. Second, the QC procedure included a time criterion. Respondents were also excluded if they spent less than 150 seconds on all DCE tasks. We assumed that ‘speeders’, who finished the online survey too quickly, did not consider the health states in detail.

For the cTTO interviews, we applied the QC process established by the EuroQol Group for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies [27]. Poor interview quality is indicated by

a short amount of time spent in the wheelchair example to explain cTTO tasks,

missing explanation for the ‘worse than dead’ task (lead-time TTO),

less than 5 minutes spent on all cTTO tasks, or

obvious inconsistency in the cTTO ratings when the value of 33333 is not the lowest or at least 0.5 higher than the state with the lowest value.

If interviews had continuously poor quality, data were excluded from the analysis. Further, the interview included a feedback module by which each respondent was presented with the rank ordering implied by their cTTO valuations. Respondents were asked to review their responses and to flag any health state they felt should be reconsidered. These states could not be re-valued but were excluded from modelling [28, 29].

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to examine the sample characteristics and the responses to the cTTO. Sample characteristics with regard to experience with illness and self-reported HRQoL were compared with the characteristics of the representative adult sample of the German EQ-5D-5L valuation study [30]. The DCE data were analysed using choice models under a random utility framework with a linear, additive utility function, as in Eq. (1):

| 1 |

The ten independent variables are made up of two variables for each EQ-5D-Y dimension, representing the two levels beyond level 1 (‘no problems’; the reference category). The coefficients therefore indicate the decrement from level 1 to the respective level.

A mixed logit model specification was chosen, given the a priori expectation that there would be unobservable random preference heterogeneity in the data and that multinomial logit models cannot account for such heterogeneity [31]. In this model, each of the ten parameters were modelled as random and normally distributed using 5000 Halton draws. Coefficients from the model were transformed into relative attribute importance (RAI) scores to aid interpretation; these were obtained by dividing the utility range for each attribute by the total utility range.

To produce the value set, the coefficients from the mixed logit model need to be anchored onto the scale of full health to dead. There are several different anchoring approaches, including rescaling based on the mean value of the worst health state (33333 rescaling), mapping the DCE data onto the cTTO data (mapping), and hybrid modelling [19, 32]. Earlier studies noted that the ratio of the cTTO and DCE data is not well balanced in the EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol, so the performance of the hybrid model may be suboptimal [17]. Of the remaining two approaches, mapping takes into account the mean values of all ten health states valued in the cTTO task, relative to one with 33333 rescaling. Therefore, we chose mapping as the preferred anchoring method. Specifically, we mapped the DCE data onto mean cTTO values, which were adjusted for censoring at − 1 (obtained by estimating Tobit models for each state). This adjustment was deemed appropriate given that the cTTO task does not allow for utilities below − 1.

A range of specifications for the mapping model were examined, including linear models with and without constants, as well as the inclusion of a quadratic term. Based on a combination of parameter significance, adjusted R-squared values, and the alignment between cTTO values and the resulting value sets, the preferred specification was a linear function without a constant, as in Eq. (2):

| 2 |

where cTTOi is the adjusted mean cTTO utility and DCEi is the latent scale DCE utility for ith health state (1 ≤ i ≤ 10). The estimated β was used to rescale the latent scale DCE values from the mixed logit model.

To compare results by parental status, we split the two samples based on responses to the question “Do you or have you ever had primary responsibility for a child (as a birth parent, foster parent, adoptive parent, or similar)?” Respondents who answered “yes” were classified as having parental experience, referred to as ‘parents’, and those answering “no” were referred to as ‘non-parents’. For the DCE responses, we compared conditional logit model results by parental status. For cTTO, we compared the adjusted mean values of the ten cTTO health states for both groups. Value sets by parental status were also estimated and compared.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In total, 1030 respondents completed the DCE survey with appropriate data quality (309 failed QC: 277 because of timing and 32 because of dominant pairs). The DCE sample is representative for the German general population aged ≥18 years with respect to gender, age groups, educational level, and region. Table 1 shows marginal proportional differences. A comparison of characteristics of included and excluded DCE respondents is presented in Table S1.1 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM). A total of 215 respondents completed the cTTO interviews. The cTTO sample underrepresents male respondents, respondents aged ≥ 70 years, and lower and middle educated respondents, whereas respondents aged 18–29 years are slightly overrepresented (see Table 1). In particular, higher educated people are overrepresented.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristics | cTTO survey | DCE survey | German adult general population [26] | Proportional difference between cTTO sample and general population | Proportional difference between DCE sample and general population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 215 | N = 1030 | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 139 (64.6) | 546 (53.0) | 51.1 | + 13.5 | + 1.9 |

| Male | 76 (35.4) | 482 (46.8) | 48.9 | − 13.5 | − 2.1 |

| Diverse | – | 2 (0.2) | – | – | – |

| Age groups, years | |||||

| 18–24 | 27 (12.6) | 95 (9.2) | 9.1 | + 3.5 | + 0.1 |

| 25–29 | 31 (14.4) | 69 (6.7) | 7.5 | + 6.9 | − 0.8 |

| 30–39 | 28 (13.0) | 153 (14.9) | 15.3 | − 2.3 | − 0.4 |

| 40–49 | 41 (19.1) | 152 (14.8) | 15.0 | + 4.1 | − 0.2 |

| 50–59 | 46 (21.4) | 203 (19.7) | 19.4 | + 2.0 | + 0.3 |

| 60–69 | 26 (12.1) | 149 (14.5) | 14.9 | − 2.8 | − 0.4 |

| ≥ 70 | 16 (7.4) | 209 (20.3) | 18.8 | − 11.4 | + 1.5 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Still in education | – | 17 (1.7) | 3.6 | − 3.6 | − 1.9 |

| Lower educationa | 11 (5.1) | 305 (29.6) | 34.7 | − 29.6 | − 5.1 |

| Middle educationb | 37 (17.2) | 336 (32.6) | 29.8 | − 12.6 | + 2.8 |

| Higher educationc | 166 (77.2) | 365 (35.4) | 31.9 | + 45.3 | + 3.5 |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 7 (0.7) | – | – | – |

| Region (federal state) | |||||

| Baden-Württemberg | – | 135 (13.1) | 13.3 | – | − 0.2 |

| Bayern | – | 165 (16.0) | 15.7 | – | + 0.3 |

| Berlin | – | 45 (4.4) | 4.4 | – | 0 |

| Brandenburg | – | 32 (3.1) | 3.1 | – | 0 |

| Bremen | – | 9 (0.9) | 0.8 | – | + 0.1 |

| Hamburg | – | 23 (2.2) | 2.2 | – | 0 |

| Hessen | – | 72 (7.0) | 7.5 | – | − 0.5 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | – | 22 (2.1) | 2.0 | – | + 0.1 |

| Niedersachsen | – | 100 (9.7) | 9.6 | – | + 0.1 |

| Nordrhein-Westfalen | – | 226 (21.9) | 21.5 | – | + 0.4 |

| Rheinland-Pfalz | – | 50 (4.9) | 4.9 | – | 0 |

| Saarland | – | 11 (1.1) | 1.2 | – | − 0.1 |

| Sachsen | – | 51 (5.0) | 5.0 | – | 0 |

| Sachsen-Anhalt | – | 28 (2.7) | 2.7 | – | 0 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | – | 36 (3.5) | 3.5 | – | 0 |

| Thüringen | – | 25 (2.4) | 2.6 | – | − 0.2 |

| Responsibility for childrend | |||||

| Yes | 120 (55.8) | 564 (54.9) | – | – | – |

| No | 95 (44.2) | 463 (45.1) | – | – | – |

Data are presented as n (%) or % unless otherwise indicated

cTTO composite time trade-off, DCE discrete choice experiment

aLower education: with or without secondary general school certificate

bMiddle education: intermediate school certificate

cHigher education: entrance qualification for universities of applied sciences; university entrance qualification

dOriginal wording of the question in the DCE as well as in the cTTO survey: “Do you or have you ever had primary responsibility for a child (as a birth parent, foster parent, adoptive parent, or similar)?”

As Table 2 illustrates, the cTTO and DCE samples differ in terms of respondents’ experiences with severe illness and respondents’ HRQoL. While the DCE sample contained a higher proportion of respondents who had experienced severe illness themselves than did the cTTO sample (37.7 vs. 22.3%, respectively), the proportion of respondents that had experience with severe illness in terms of other people that they had cared for was higher in the cTTO sample than in the DCE sample (30.7 vs. 14.7%, respectively). The reported problems on EQ-5D-5L and in the mean visual analogue scale (VAS) value show that the cTTO sample reported fewer health problems than the DCE sample. However, the DCE sample corresponds better with the self-reported health of the German adult general population [30].

Table 2.

Respondents’ experiences with severe illness and health-related quality of life

| Respondents’ experience with illness and their EQ-5D-5L reported HRQoL | cTTO survey | DCE survey | German adult general population [30] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiences with severe illness | |||

| In yourself (yes) | 48 (22.3) | 388 (37.7) | 34.4 |

| In your family (yes) | 150 (69.8) | 687 (66.7) | 68.8 |

| In caring for another person (yes) | 66 (30.7) | 151 (14.7) | 82.6 |

| EQ-5D-5L—descriptive system | |||

| Mobility (MO) | |||

| No problems | 194 (90.2) | 664 (64.5) | 69.3 |

| Slight problems | 14 (6.5) | 219 (21.3) | 15.4 |

| Moderate problems | 6 (2.8) | 107 (10.4) | 9.9 |

| Severe problems | 1 (0.5) | 35 (3.4) | 5.3 |

| Unable | – | 4 (0.4) | 0.2 |

| Missing | – | 1 (0.1) | – |

| Self-care (SC) | |||

| No problems | 207 (97.2) | 934 (90.9) | 93.61 |

| Slight problems | 3 (1.4) | 63 (6.1) | 3.54 |

| Moderate problems | 3 (1.4) | 24 (2.3) | 1.9 |

| Severe problems | – | 6 (0.6) | 0.7 |

| Unable | – | 1 (0.1) | 0.3 |

| Missing | – | 2 (0.2) | – |

| Usual activities (UA) | |||

| No problems | 195 (90.7) | 688 (66.9) | 77.3 |

| Slight problems | 14 (6.5) | 226 (22.0) | 12.7 |

| Moderate problems | 5 (2.3) | 75 (7.3) | 7.3 |

| Severe problems | 1 (0.5) | 32 (3.1) | 2.3 |

| Unable | – | 7 (0.7) | 0.5 |

| Missing | – | 2 (0.2) | – |

| Pain/discomfort (PD) | |||

| No | 120 (55.8) | 347 (33.8) | 44.4 |

| Slight | 73 (34.0) | 449 (43.7) | 35.1 |

| Moderate | 17 (7.9) | 188 (18.3) | 15.8 |

| Severe | 5 (2.3) | 42 (4.1) | 4.4 |

| Extreme | – | 2 (0.2) | 0.4 |

| Missing | – | 2 (0.2) | – |

| Anxiety/depression (AD) | |||

| Not | 168 (78.1) | 589 (57.4) | 74.4 |

| Slightly | 36 (16.7) | 274 (26.7) | 17.2 |

| Moderately | 9 (4.2) | 103 (10.0) | 6.9 |

| Severely | 1 (0.5) | 45 (4.4) | 1.3 |

| Extremely | 1 (0.5) | 16 (1.6) | 0.3 |

| Missing | – | 3 (0.3) | – |

| EQ-5D-5L—Index values | |||

| Mean | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Standard deviation | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Minimum | 0.7 | − 0.3 | − 0.5 |

| Maximum | 1.0 | 1 | 1 |

| EQ-5D-5L—visual analogue scale (VAS) | |||

| Mean | 86.9 | 73.7 | 79.5 |

| Standard deviation | 12.13 | 18.6 | 17.1 |

| Minimum | 30 | 1 | 10 |

| Maximum | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Data are presented as n (%) or % unless otherwise indicated

cTTO composite time trade-off, DCE discrete choice experiment

Modelling

In the feedback module, 13.77% of cTTO responses (n = 296) were removed by respondents. The following results include all cTTO valuations after the feedback module (2150–296 = 1854 observations). The mean cTTO values ranged from − 0.260 for health state 33333 to 0.970 for health state 21111 (Table 3). For the adjusted cTTO data, the value for health state 33333 was − 0.350.

Table 3.

Composite time trade-off results

| State | N | Observed raw data | No. of − 1 observations | Adjusted data for censoring at − 1a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| 21111 | 205 | 0.9700 | 0.0038 | 0 | 0.9700 | 0.0038 |

| 11112 | 205 | 0.9485 | 0.0058 | 0 | 0.9485 | 0.0058 |

| 11121 | 207 | 0.9326 | 0.0115 | 1 | 0.9325 | 0.0115 |

| 22232 | 169 | 0.4707 | 0.0402 | 11 | 0.4594 | 0.0429 |

| 22223 | 180 | 0.4217 | 0.0399 | 13 | 0.4081 | 0.0429 |

| 32223 | 175 | 0.2757 | 0.0449 | 18 | 0.2499 | 0.0499 |

| 31133 | 172 | 0.1125 | 0.0498 | 27 | 0.0584 | 0.0588 |

| 33323 | 170 | − 0.0250 | 0.0469 | 26 | − 0.0756 | 0.0550 |

| 33233 | 179 | − 0.0835 | 0.0471 | 35 | − 0.1584 | 0.0582 |

| 33333 | 192 | − 0.2604 | 0.0425 | 43 | − 0.3497 | 0.0544 |

SE standard error

aAdjustments made using Tobit models

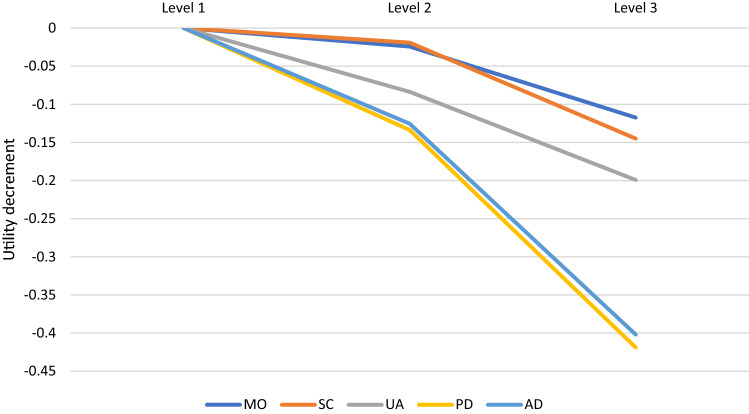

The coefficients from the mixed logit model, the RAI scores, and the rescaled coefficients (the value set) are shown in Table 4. The results from the mapping model that were used to create the value set can be found in Table S2.1 in the ESM. The predicted values ranged from − 0.283 (for 33333) to 1 (for 11111). The preference ranking, from most to least important, of the dimensions was as follows: (1) PD, (2) AD, (3) UA, (4) SC, and (5) MO. The utility decrements for a movement from MO1 to MO2 and from SC1 to SC2 were particularly small at approximately 0.02. In contrast, the decrement for a movement from PD1 to PD2 was approximately 0.13.

Table 4.

Modelling results for the German EQ-5D-Y value set

| Independent variables of the model | Latent scalea | Rescaledb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SD | Relative attribute importance (%) | Value set | |

| MO2 | − 0.1778** (0.0767) | 0.1650 (0.1233) | 9.2 | − 0.0242 |

| MO3 | − 0.8627*** (0.1236) | 1.0468*** (0.0936) | − 0.1175 | |

| SC2 | − 0.1401** (0.0566) | 0.4098*** (0.1359) | 11.3 | − 0.0191 |

| SC3 | − 1.0652*** (0.0849) | 0.5188*** (0.1169) | − 0.1450 | |

| UA2 | − 0.6145*** (0.0548) | 0.1687 (0.2060) | 15.5 | − 0.0837 |

| UA3 | − 1.4636*** (0.0845) | 0.5726*** (0.0919) | − 0.1993 | |

| PD2 | − 0.9820*** (0.0594) | 0.0632 (0.0881) | 32.7 | − 0.1337 |

| PD3 | − 3.0772*** (0.1323) | 1.4831*** (0.0976) | − 0.4190 | |

| AD2 | − 0.9213*** (0.0581) | 0.2160 (0.1664) | 31.3 | − 0.1254 |

| AD3 | − 2.9521*** (0.1220) | 1.6490*** (0.0949) | − 0.4019 | |

| Log-likelihood | − 6094 | |||

| Observations | 30,900 | |||

| Sample size | 1030 | |||

Numbers in parentheses represent standard errors

AD feeling worried/sad/unhappy, cTTO composite time trade-off, DCE discrete choice experiment, MO mobility, PD having pain/discomfort, SC looking after myself, SD standard deviation, UA doing usual activities

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

aBased on a mixed logit model, with all parameters modelled as random and normally distributed, using 5000 Halton draws. Coefficients indicate the decrement from level 1 to the respective level

bRescaled using a linear mapping model between the DCE results and the adjusted mean values from the cTTO task

Applying the value set, EQ-5D-Y health state utilities can be estimated by subtracting the relevant decrement for each problem on each dimension from 1. For example, the predicted EQ-5D-Y index value for health state 22233 can be calculated as follows:

The symptomatic dimensions (PD and AD) had similar RAI scores, with each about 30%, whereas functional dimensions (MO, SC, and UA) had far lower RAI scores, ranging from 9.2% for MO to 15.5% for UA (Table 4). The decrements of the two symptomatic dimensions, PD and AD, were also similar, with PD having the greatest overall impact. The only dimension with linear utility decrements by level was UA, with larger utility decrements occurring between level 2 and 3 for each of the other dimensions, compared with the decrement between levels 1 and 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Utility decrements of German EQ-5D-Y value set. AD feeling worried/sad/unhappy, MO mobility, PD having pain/discomfort, SC looking after myself, UA doing usual activities

Subgroup Analysis: Parental Status

The DCE and cTTO samples showed similar proportions of respondents reporting responsibility for children either at present or in the past (55–56% answering ‘yes’). Demographics differed between parents and non-parents (Table S3.1 in the ESM). For example, non-parents were typically younger, and a higher proportion had high education levels (or were still in education). The DCE results did not differ substantially between these two groups (Table S3.2 in the ESM). Non-parents had a slightly stronger preference for MO and a weaker preference for PD; however, the difference in RAI scores was only 1.4 pp (percentage points) in both cases. Figure 2 illustrates the adjusted mean utilities from the cTTO task for each health state in both subgroups. Mean utilities were always greater for parents than for non-parents. However, only three of the mean differences were statistically significant (two mild and one moderate state). When generating two separate value sets based on data from parents and non-parents, the value sets had significantly different scales (Table S3.3 and Fig. S3.1 in the ESM): the value for 33333 for non-parents was − 0.210 compared with − 0.358 for parents.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of adjusted mean utilities from the composite time trade-off task, by parental status. Mean differences; ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Discussion

The EQ-5D-Y valuation study in Germany was one of the first studies to develop an EQ-5D-Y value set. We applied the recently published valuation protocol and obtained health state preferences using a combination of DCE and cTTO. The value set was modelled using a mixed logit model, and the latent DCE coefficients were anchored using a linear mapping approach. The developed German EQ-5D-Y value set can be applied alongside the EQ-5D-Y descriptive system, which is appropriate for use in children and adolescents aged 8–15 years (self-report) and children aged 4–7 years (proxy report); in special cases, the instrument can also be used for adolescents aged 16 or 17 years [12]. Indeed, there is discussion on whether values derived considering a 10-year-old in the valuation tasks are suitable for the whole age range of the instrument. A recently published qualitative study indicated that health state preferences for a 10-year-old child might not be representative for the full EQ-5D-Y age range [33], whereas quantitate studies did not find significantly different values when different age descriptions were used [34, 35].

The results illustrate that the German adult general public considers PD as the most important dimension for children and adolescents, followed by AD. Of the functional dimensions, UA had the highest decrements for level 2 and 3 compared with the two other dimensions (MO and SC). Overall, people consider it important that children and adolescents have no pain/discomfort, are not worried/sad/unhappy, and can do their usual activities without any limitations, as children without health problems do.

The same ordering of the three most important dimensions was observed in the Slovenian EQ-5D-Y valuation study [16]. However, the level decrements in all dimensions are higher in the Slovenian than the German EQ-5D-Y value set, with the exception of AD, where decrements are similar. Therefore, the value range is larger in Slovenia (− 0.691 to 1) than in Germany (− 0.283 to 1). Nevertheless, this comparison is limited because Prevolnik Rupel et al. [16] used the weighted censored average value of the worst health state 33333 for anchoring, whereas the means of all ten cTTO health states were used for rescaling in Germany. According to the recently published Spanish EQ-5D-Y value set, PD and AD were the two most important dimensions, followed by MO, which differs from the results in Germany and Slovenia. The value range in Spain is relatively large (− 0.539 to 1) and therefore more comparable to the Slovenian than to the German value set [36]. In terms of comparability of the value sets, it is worth noting that the Spanish and German EQ-5D-Y value sets were modelled differently [36]. The Japanese EQ-5D-Y value set differs from all other EQ-5D-Y value sets as the value range is particularly narrow (0.28–1) and the coefficients are accordingly much smaller. In particular, the level 3 decrements are smaller than those of the German EQ-5D-Y value set. The Japanese team deviated from the protocol by including 26 health states in the cTTO exercise, which also limits comparability [17]. Furthermore, there might be cultural differences in the context of valuing child health states between countries that influence the resulting EQ-5D-Y value sets. Notably, the Japanese values for the adult EQ-5D-5L instrument were higher than those of European EQ-5D-5L value sets [17, 37].

When comparing the German EQ-5D-5L [30] and EQ-5D-Y value sets, it is notable that the latter has a smaller value range and that single decrements per level differ. However, one similarity can be observed: the dimensions with the highest decrements are PD and AD. More detailed comparison is limited because of the different numbers of severity levels between the instruments, the different wording used in the adult- and youth-specific instruments, and the different valuation methods and modelling approaches [18, 30].

With the establishment of the valuation protocol, more EQ-5D-Y value sets will be produced in the future, and the influence of using different value sets for children and adolescents and adults in CUA will need to be further explored. There are no guidelines from international agencies on using youth-specific preference-based measures, and there are concerns about how to use youth-specific measures alongside adult measures or how to combine and/or compare these utilities [6].

When comparing results by parental status, mean cTTO values were always greater for parents than for non-parents. These differences were only statistically significant for a few health states, although this may partly be explained by the high variation in values for some states (particularly severe states) and the relatively small subgroup sizes. The observed differences are in line with earlier studies [9, 38]. Matza et al. [9] also found that parents were less willing to trade within TTO tasks, so parents’ responses revealed higher values than those of non-parents. Hartman and Craig [8] explored health state values for children using a DCE with a time component, showing that parents preferred a longer lifespan instead of a longer time in healthier states compared with non-parents. If the time component is the key driver of differences between parents and non-parents, this may explain why the DCE results did not differ substantially between these two groups in our study. As noted by Powell et al. [39], future valuation studies may benefit from being representative in relation to parental status given the potential impact on preferences when valuing child health. Our results indicate that this representativeness should apply to both the DCE and the cTTO samples.

This study has some limitations. The DCE sample is nationally representative in terms of gender, age groups, education, and region but not necessarily in terms of other variables. Furthermore, there is evidence of a tendency for low-level engagement and random responses when DCEs are administered online [40]. We attempted to address this issue by including the QC criteria, but we cannot be entirely sure that the sample consists of only individuals who were fully engaged in the task. However, there is debate within the literature about whether respondents with ‘irrational’ responses should be excluded from analyses [41]. Furthermore, a convenience cTTO sample was recruited (rather than a nationally representative sample), and highly educated respondents were overrepresented, which might have influenced the results. Furthermore, the latter portion of the cTTO data collection was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the interviews were conducted before the pandemic outbreak, but 32 respondents were interviewed after the lockdown from March to May 2020. These respondents may have had slightly different preferences to the other respondents because of the pandemic. Additionally, the later interviews were online/video interviews, which may also have influenced values, although online interviews have been shown to be feasible, with acceptable data quality [42]. Moreover, demographics of the parent and non-parent groups differed, which might have affected health state valuations and the differences found between the two groups. However, differences were as typically expected between these two groups, and it is not possible to disentangle the effects. Additionally, this subgroup analysis was not explicitly considered at the design stage, nor is it part of the EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol, so it was not factored into the experimental design.

It is worth highlighting that there is ongoing discussion on the most appropriate way to value youth health states and analyse valuation data. The EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol represents an initial set of recommendations for achieving this goal but it can (and likely will) be updated over time as further research is conducted (including EQ-5D-Y valuation studies such as this).

Conclusion

The German EQ-5D-Y valuation study was one of the first studies to apply the recently published EQ-5D-Y valuation protocol. It confirms that the development of EQ-5D-Y value sets using the methods set out in the protocol is feasible. The results of the EQ-5D-Y valuation study in Germany show that the adult general population considers PD and AD to be the most important EQ-5D-Y health dimensions for children and adolescents. The availability of a German EQ-5D-Y value set enables a preference-based HRQoL measurement in children and adolescents in Germany and therefore enables the instrument to be used in economic evaluations, mainly CUAs, of paediatric healthcare interventions. Furthermore, the value set may also prove useful in other contexts (e.g., clinical contexts) in which summarising HRQoL into a single summary score would be helpful.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nahne Knizia, Viola Nicasius-Burbach, Lisa Steiner, and Alina Baumgärtner, who acted as interviewers during the study. The authors also thank the EuroQol office staff (Elly Stolk and Bram Roudijk) for their support in conducting the study and their advice/consultation during the data analysis.

IMPACT HTA HRQoL Group: Valentina Prevolnik Rupel3, Juan Manuel Ramos-Goñi4.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Declarations

Funding

The funding of this study was two-part. Most of the online DCE data collection was conducted within the European Commission-funded project IMPACT HTA (Improved methods and actionable tools for enhancing Health Technology Assessment), work package 5: “Exploring health preferences on different sub-population groups using EQ-5D” (Grant number 779312; www.impact-hta.eu). Additionally obtained DCE data and the cTTO data collection were funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (EQ project no. 20180510). The European Commission had no role in the study design, collection, and analysis of data; writing of the report; or submission of the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

Simone Kreimeier, David Mott, Kristina Ludwig, and Wolfgang Greiner, as well as Valentina Prevolnik Rupel and Juan Manuel Ramos-Goñi (members of the IMPACT HTA HRQoL Group), are members of the EuroQol Group. There are no other conflicts of interest. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the EuroQol Group.

Availability of data and material

All the data and material will be stored and publicly available at the certified data repository Zenodo, hosted by CERN.

Code availability

Code is available from the authors on request.

Ethics approval

Ethical approvals for both sub-surveys, using the DCE method and the cTTO method, were received in Germany from the Ethics Committee of Bielefeld University, No. EUB 2018-172 and EUB 2019-204.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JMR-G prepared the concept and the design of the study. SK, KL, WG, JMR-G, and VPR contributed to the material preparation and data collection. The analysis was performed by DM and SK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SK and DM, and all authors commented on subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

This article is published in a special edition journal supplement wholly funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation

Footnotes

The terms ‘youth specific’ and ‘youth’ as used in this paper refer to both children and adolescents.

Due to the number of levels, the EQ-5D-Y is sometimes also referred to as the EQ-5D-Y-3L as a version with five levels is also under development.

To address a research objective outside the scope of this paper, the interviews also contained 15 DCE tasks after point seven. However, as these data are not relevant to the context of this article, they are not considered further here.

The original Online version of this article was revised :The disclosure statement was missed and published.

The members of “IMPACT HTA HRQoL Group” are presented in Acknowledgements section.

Change history

10/14/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40273-022-01206-x

Contributor Information

Simone Kreimeier, Email: simone.kreimeier@uni-bielefeld.de.

IMPACT HTA HRQoL Group:

References

- 1.Drummond MF, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy-Martin M, Slaap B, Herdman M, van Reenen M, Kennedy-Martin T, Greiner W, et al. Which multi-attribute utility instruments are recommended for use in cost-utility analysis? A review of national health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:1245–1257. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon J, Kim SW, Ungar WJ, Tsiplova K, Madan J, Petrou S. Patterns, trends and methodological associations in the measurement and valuation of childhood health utilities. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1705–1724. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G, Ratcliffe J. A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:1013–1028. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ungar WJ, Gerber A. The uniqueness of child health and challenges to measuring costs and consequences. In: Ungar WJ, editor. Economic evaluation in child health. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 2010. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, Ratcliffe J. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: where are we now and where are we going? Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:325–340. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00873-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreimeier S, Greiner W. EQ-5D-Y as a health-related quality of life instrument for children and adolescents: the instrument's characteristics, development, current use, and challenges of developing its value set. Value Health. 2019;22:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman JD, Craig BM. Comparison of parent and non-parent preferences in the valuation of child health. Value Health. 2016;19:A275. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.1960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matza LS, Boye KS, Feeny DH, Johnston JA, Bowman L, Jordan JB. Impact of caregiver and parenting status on time trade-off and standard gamble utility scores for health state descriptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mott DJ, Shah KK, Ramos-Goñi JM, Devlin NJ, Rivero-Arias O. Valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L health states using a discrete choice experiment: do adult and adolescent preferences differ? Med Decis Mak. 2021;41:584–596. doi: 10.1177/0272989X21999607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratcliffe J, Huynh E, Stevens K, Brazier J, Sawyer M, Flynn T. Nothing about us without us? A comparison of adolescent and adult health-state values for the child health utility-9D using profile case best-worst scaling. Health Econ. 2016;25:486–496. doi: 10.1002/hec.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-Y user guide: basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-Y instrument. 2014. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-y-about/. Accessed 4 Feb 2020.

- 13.Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:887–897. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9649-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevolnik Rupel V, Ogorevc M. EQ-5D-Y value set for Slovenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiroiwa T, Ikeda S, Noto S, Fukuda T, Stolk E. Valuation survey of EQ-5D-Y based on the international common protocol: development of a value set in Japan. Med Decis Mak. 2021;41:597–606. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreimeier S, Oppe M, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cole A, Devlin N, Herdman M, et al. Valuation of EuroQol Five-Dimensional Questionnaire, Youth Version (EQ-5D-Y) and EuroQol Five-Dimensional Questionnaire, Three-Level Version (EQ-5D-3L) health states: the impact of wording and perspective. Value Health. 2018;21:1291–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah KK, Ramos-Goñi JM, Kreimeier S, Devlin NJ. An exploration of methods for obtaining 0 = dead anchors for latent scale EQ-5D-Y values. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01205-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Stolk E, Shah K, Kreimeier S, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N. International valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00909-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Anis A. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ. 2012;31:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolk EA, Oppe M, Scalone L, Krabbe PFM. Discrete choice modeling for the quantification of health states: the case of the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2010;13:1005–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oppe M, Rand-Hendriksen K, Shah K, Ramos-Goñi JM, Luo N. EuroQol protocols for time trade-off valuation of health outcomes. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:993–1004. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen BMF, Oppe M, Versteegh MM, Stolk EA. Introducing the composite time trade-off: a test of feasibility and face validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devlin NJ, Tsuchiya A, Buckingham K, Tilling C. A uniform time trade off method for states better and worse than dead: feasibility study of the 'lead time' approach. Health Econ. 2011;20:348–361. doi: 10.1002/hec.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS). Bevölkerungsstand am 31.12.2018. Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011. 2019. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?sequenz=statistikTabellen&selectionname=12411#abreadcrumb. Accessed 24 Sept 2019.

- 27.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Slaap B, Busschbach JJV, Stolk E. Quality control process for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Value Health. 2017;20:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, van Hout B, Ramos-Goñi JM. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2019;22:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig K, von der Schulenburg J-MG, Greiner W. Valuation of the EQ-5D-5L with composite time trade-off for the German population—an exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:39. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0617-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg J-M, Greiner W. German Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:663–674. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vass C, Boeri M, Karim S, Marshall D, Craig B, Ho K, Mott DJ, Ngorsuraches S, Badawy S, Muhlbacher A, Gonzalez J, Heidenreich S. Accounting for preference heterogeneity in discrete-choice experiments: a review of the state of practice. Value Health. 2022. (forthcoming). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Rowen D, Brazier J, van Hout B. A comparison of methods for converting DCE values onto the full health-dead QALY scale. Med Decis Mak. 2015;35:328–340. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14559542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reckers-Droog V, Karimi M, Lipman S, Verstraete J. Why do adults value EQ-5D-Y-3L health states differently for themselves than for children and adolescents: a think-aloud study. Value Health. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Retra JGA, Essers BAB, Joore MA, Evers SMAA, Dirksen CD. Age dependency of EQ-5D-Youth health states valuations on a visual analogue scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:386. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01638-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos-Goñi JM, Carillo AE, Rivero-Arias O, Rowen D, Mott DJ, Shah K, Oppe M. Does changing the age of a child to be considered in EQ-5D-Y-3L DCE based valuation studies affect health preferences? Value Health. 2022. (forthcoming). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Estévez-Carrillo A, Rivero-Arias O, Wolfgang G, Simone K, et al. Accounting for unobservable preference heterogeneity and evaluating alternative anchoring approaches to estimate country-specific EQ-5D-Y value sets: a case study using Spanish preference data. Value Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiroiwa T, Ikeda S, Noto S, Igarashi A, Fukuda T, Saito S, Shimozuma K. Comparison of value set based on DCE and/or TTO data: scoring for EQ-5D-5L health states in Japan. Value Health. 2016;19:648–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Pol M, Shiell A. Extrinsic goals and time tradeoff. Med Decis Mak. 2007;27:406–413. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07302127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell PA, Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Tsuchiya A, Brazier JE. Valuing child and adolescent health: a qualitative study on different perspectives and priorities taken by the adult general public. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:222. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01858-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulhern B, Longworth L, Brazier J, Rowen D, Bansback N, Devlin N, Tsuchiya A. Binary choice health state valuation and mode of administration: head-to-head comparison of online and CAPI. Value Health. 2013;16:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Deleting 'irrational' responses from discrete choice experiments: a case of investigating or imposing preferences? Health Econ. 2006;15:797–811. doi: 10.1002/hec.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipman SA. Time for Tele-TTO? Lessons learned from digital interviewer-assisted time trade-off data collection. Patient. 2021;14:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s40271-020-00490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.