Abstract

Oxytocin (OT), a nonapeptide, has a variety of functions. Despite extensive studies on OT over past decades, our understanding of its neural functions and their regulation remains incomplete. OT is mainly produced in OT neurons in the supraoptic nucleus (SON), paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and accessory nuclei between the SON and PVN. OT exerts neuromodulatory effects in the brain and spinal cord. While magnocellular OT neurons in the SON and PVN mainly innervate the pituitary and forebrain regions, and parvocellular OT neurons in the PVN innervate brainstem and spinal cord, the two sets of OT neurons have close interactions histologically and functionally. OT expression occurs at early life to promote mental and physical development, while its subsequent decrease in expression in later life stage accompanies aging and diseases. Adaptive changes in this OT system, however, take place under different conditions and upon the maturation of OT release machinery. OT can modulate social recognition and behaviors, learning and memory, emotion, reward, and other higher brain functions. OT also regulates eating and drinking, sleep and wakefulness, nociception and analgesia, sexual behavior, parturition, lactation and other instinctive behaviors. OT regulates the autonomic nervous system, and somatic and specialized senses. Notably, OT can have different modulatory effects on the same function under different conditions. Such divergence may derive from different neural connections, OT receptor gene dimorphism and methylation, and complex interactions with other hormones. In this review, brain functions of OT and their underlying neural mechanisms as well as the perspectives of their clinical usage are presented.

Keywords: functions, hypothalamus, neurohumoral reflex, oxytocin, supraoptic nucleus

Introduction

Hormones are important factors for body development and adaptive responses to environmental changes. Among many hormones, oxytocin (OT) is not only the key factor in the milk-ejection reflex, the most classical neural humoral reflex (Wakerley et al., 1994), but also possesses a variety of functions such as regulation of immunological, metabolic and endocrine activity and many other peripheral functions (Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019b; Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2013) as outlined in Figure 1. OT is mainly synthesized in OT neurons in the supraoptic nucleus (SON), paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and several accessory nuclei in the hypothalamus. In the SON and lateral and peripheral PVN, OT neurons, as magnocellular neuroendocrine cells, co-exist with vasopressin (VP) neurons as well as astrocytes (Wang et al., 2021a) and project to many hypothalamic sites, forebrain structures, periventricular area in addition to the posterior pituitary (Figure 2A). In the medial PVN, there is a group of non-neuroendocrine parvocellular OT neurons that innervate varieties of brainstem and spinal cord sites (Figure 2B). There are mutual innervations among the SON and PVN. For example, some spinal cord-projecting parvocellular OT neurons send collateral projections onto magnocellular OT neurons (Eliava et al., 2016). The inherent connections among OT neurons within different hypothalamic nuclei form a network (Figure 2C), which is an important structural basis for coordinated activity of OT neurons at different sets in response to external stimuli. In addition, many extrahypothalamic regions also contain OT neurons or receive neural innervations from OT neurons (Knobloch & Grinevich, 2014), and they may exert local regulatory roles. OT functions are mediated by OT receptor (OTR) that is present on the target tissue throughout the mammalian body (Assinder, 2022; Gimpl & Fahrenholz, 2001). Thus, OT can modulate higher brain functions, instinctive behaviors, somatic and visceral sensations, visceral motor activity, etc. In this review, OT functions in the central nervous system are discussed to aid readers in understanding OT functions as they face abundant, sometime contradictory reports. Table 1 is a summary of OT higher brain functions and the underlying mechanisms.

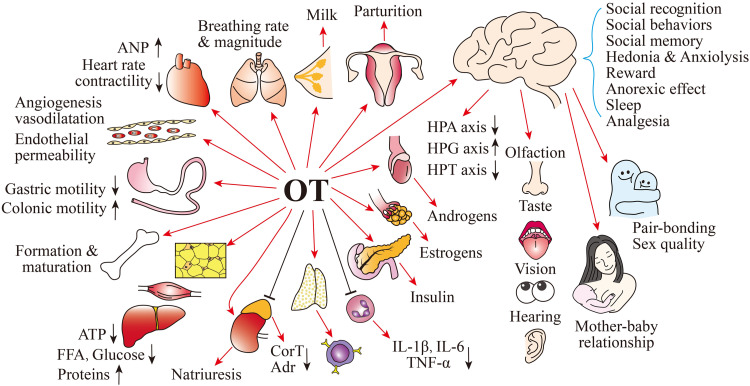

Figure 1.

Summary of hormonal functions of oxytocin (OT). Abbreviations: Adrenaline (Adr), Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), Corticosteroids (CorT), Free fatty acids (FFA), Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, Hypothalamic pituitary gonad (HPG) axis, Hypothalamic pituitary thyroid (HPT) axis, Interleukin (IL), and Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.

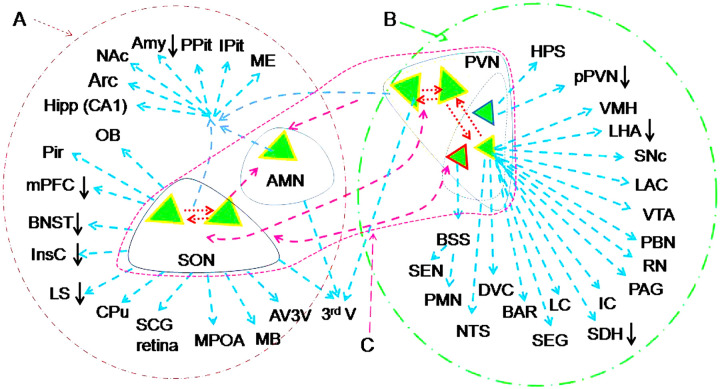

Figure 2.

Outline of neural innervations of OT neurons in the central nervous system. A-C. Magnocellular OT neurons (A), parvocellular OT neurons (B) and their interconnections (C). Note that: Oxytocin (OT, green triangles) neurons in the parvocellular division (smaller triangles) of the paraventricular nucleus (pPVN) likely belong to different functional groups; OT neurons in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and PVN connect mutually through axon/axon collaterals (dashed blue arrows) or dendrites (red dashed arrows); the downward arrows indicate inhibition evoked by OT activation of GABAergic interneurons. Abbreviations of neural structures: The third ventricle (3rdV), Accessory magnocellular nuclei (AMN), Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), Amygdala (Amy), Arcuate nucleus (Arc), Anteroventral third ventricle region (AV3 V), Barrington's nucleus (BAR), Bed nuclei of the stria terminalis (BNST), Bulbospinal system (BSS), Caudate putamen (CPu), Dorsal vagal complex (DVC), Hippocampus (Hipp), Hypophyseal portal system (HPS), Inferior colliculus (IC), Insular cortex (InsC), Intermediate lobe of the pituitary (IPit), Lateral hypothalamus area (LHA), Lateral septum (LS), Left auditory cortex (LAC), Locus coeruleus (LC), Mammillary body complex (MB), Median eminence (ME), Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), Medial preoptic area (MPOA), Nucleus accumbens (NAc), Nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), Olfactory bulb (OB), Parabrachial nucleus (PBN), Phrenic motor nucleus (PMN), Periaqueductal gray (PAG), Piriform cortex (Pir), Posterior pituitary (PPit), Raphe nucleus (RN), Spinal dorsal horn (SDH), Spinal ejaculation generator (SEG). Substantia nigra compact part (SNc), Superior cervical ganglion (SCG), Sympathetic excitatory neuron (SEN), Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH), Ventral tegmental area (VTA). Neural connections of OT neurons refer to (Knobloch & Grinevich, 2014; Liao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021).

Table 1.

OT Higher Brain Functions and the Underlying Mechanisms.

| Category | Physiologic effects | Neural mechanisms | Pharmacological effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social cognition | (1)Promote their sociability, learning and memory, and locomotor activity while decreasing plasma corticosterone and anxiety. | (2)Desensitizing amygdala by increasing 5-HT in RN, NA in LC, GABA in mPFC and DA in VTA, NAc, and ACC. | (3) IAO can facilitate social recognition and inter-personal synchrony, but alleviate negative symptoms in schizophrenia | (1) (Cuneo et al., 2021; Jahangard et al., 2020; Meixner et al., 2019); (2) (Jung et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021a; Maier et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021b); (3) (Runyan et al., 2021; Sabe et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2021b) |

| Pro-social behavior | (4)Promote parenting behavior, pair-bonding, social interaction, and affiliative behavior as well as neonate brain development; reducing fear. | (5) Activating GABA inhibition during delivery; promoting neurite outgrowth and synapse formation; holding normal OT/OTR signaling; inhibiting amygdala. | (6) IAO improves social functioning in ASD patients; activating GABAergic signal in BNST; activating PVN-social brain routes; optimizing OT neuronal activity. | (4) (John & Jaeggi, 2021; Shishido et al., 2021; Yoshihara et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019); (5) (Reichova et al., 2021; Tyzio et al., 2014); (6) (Francesconi et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Jimenez et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021e) |

| Learning and memory | (7) Enhance positive social memory and attenuate memory consolidation and retrieval of non-social stimuli. | (8) Increase OT release in the OBs; enhance cortical information transfer; increase signal-to-noise ratio via GABA action; inhibit neuronal death. | (9) IAO can reduce deficits in safety learning, contextual fear and levels of glucocorticoid; reverse amyloid β-induced hippocampal impairment. | (7) (Feifel et al., 2012; Guastella et al., 2008; Latt et al., 2018; Plasencia et al., 2019; Tse et al., 2018); (8) (Bertoni et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2015; Larrazolo-Lopez et al., 2008); (9) (Kreutzmann & Fendt, 2021; Takahashi et al., 2020). |

| Anti-depressive & anxiolysis | (10) Increase self-confidence and inter-personal relationship; decrease cognitive anxiety, social stress, depression and suicidality. | (11) Inhibit amygdala and HPA-axis by activation of PVN GABA action; protect the hippocampus; increase 5-HT release in RN and RN-hippocampal activity. | (12) Cure moderate sub-clinical depression; reverse maternal depression; enhance connectivity of amygdala and bilateral insula and middle CG genotype in patients. | (10) (Fisher et al., 2021; La Fratta et al., 2021; Torres et al., 2022; Warrener et al., 2021); (11) (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2021; Matsushita et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2022; Yoshida et al., 2009); (12) (Li et al., 2021e; Lindley Baron-Cohen et al., 2021) |

| Reward | (13) Produce enjoying experience and motivation to rewarding stimuli like pair bonding, prize, gambling, delicious meals; sexual contact, and positive social interaction; promote sociability, suppress social stress, depression and anxiety. | (14) Activate 5-HT and Glu transmission from RN to VTA and VTA to reinforce learning by serotonergic neuron co-transmitter glutamate mesocorticolimbic DA pathway from the VTA to the NAc and PVN; inhibit activities of the HPA axis, amygdala and endogenous opioid system | (15) OT-driven social signals compete with drug-elicited reinforcing signals in brain reward circuitry and enable the rewarding effects of prosocial behavior at the expense of drug-related rewards. It involves DA and glutamatergic systems in NAc, GABA and Glu signals in the CeA, and opioid effect in the VTA. | (13) (Cuneo et al., 2021; Dolen et al., 2013; Horrell et al., 2019; La Fratta et al., 2021; Siu et al., 2021); (14) (Courtiol et al., 2021; Hung et al., 2017; Sundar et al., 2021); (15) (Bowen & Neumann, 2017; Logan et al., 2021; Pedersen, 2017; Tops et al., 2014) |

| Negative impacts | (16) Create intergroup conflict and violence as well as maternal attacks; postpartum maternal depression following social stress. | (17) Prolonged increase in somatodendritic OT secretion causes post-excitation inhibition of OT neurons, which results in -abnormality of brain and peripheral functions; it is often associated with increase VP secretion and HPA-axis activity | (18) More anhedonia in individuals low in extraversion, trust-altruism, and openness to experience, elevated depressive symptoms recall memories, particularly in non-social context; intrapartum OT application increase morbidity of postnatal depressive symptoms in pregnant women | (16) (De Dreu et al., 2011; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021e); (17) (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021c; Li et al., 2021e; Liu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2006) (18) (Tichelman et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2021a; Wong et al., 2021c) |

Abbreviations: 5-HT, serotonin; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CeA, central nucleus of the amygdala; DA, dopamine; GABA, ɣ-aminobutyric acid; Glu, glutamate; HPA axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis; IAO, intranasal application of OT; LC, Locus coeruleus; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; NA, norepinephrine; NAc, nucleus accumbens; OBs, olfactory bulb; OT, oxytocin; OTR, OT receptor; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; RN, raphe nuclei; VP, vasopressin; VTA.

Higher Brain Functions

In humans, OT is essential for brain functioning during development. OT roles have been well recorded in at-birth anti-inflammation and protection of the developing fetal brain (Kingsbury & Bilbo, 2019), neonate preference for the mother (Galbally et al., 2011) and social functioning of children and adolescents (Ellis et al., 2021; John & Jaeggi, 2021). OT is also involved in maintenance of normal brain functions during aging (Rocha-Santos et al., 2020; Sakakibara et al., 2010). A dramatic OT brain function is its modulation of cognition and behavior in social activity. As reported, OTRs are present in extensive brain areas in human, particularly the olfactory bulbs (OBs), globus pallidum, caudate, putamen, thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and temporal pole (Quintana et al., 2019). Thus, OT can influence cortical organization and regulate higher brain functions through many approaches as outlined in Figure 3.

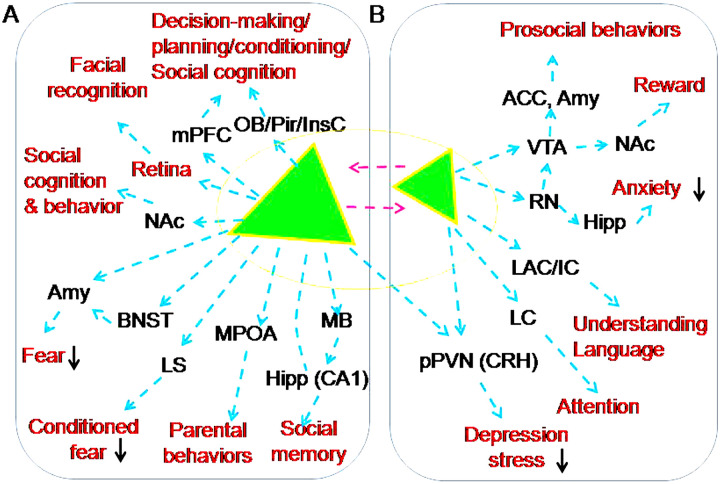

Figure 3.

Approaches of OT modulation of the higher brain functions. A-B. Magnocellular OT neurons (A) and parvocellular OT neurons (B). The red font indicates a variety of OT effects (please refer to the text for details). Signs and abbreviations are the same as Figure 2.

Social Cognition

Abundant evidence indicates that OT can promote social recognition. In patients with ovarian cancer, higher levels of positive affection, purpose in life and social nurturance are related to higher levels of OT in ascites (Cuneo et al., 2021). Suicide survivors have significantly lower serum OT concentrations, which are associated with negative perceptions of the quality of social lives (Jahangard et al., 2020). OT levels in cerebrospinal fluid are increased in individuals with schizophrenia but decreased in their serum (Hernandez-Diaz et al., 2021). Moreover, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)? rs53576 and functional polymorphism rs2268498 of OTR gene influence language functions by reducing an interpretation bias in the spontaneous appraisal of neutral words (Meixner et al., 2019). Malfunctions of OT-OTR signaling processes can significantly disturb social interaction capabilities and cope with daily life activities in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), major depression, Williams syndrome, sexual offenses, fragile X syndrome and posttraumatic stress disorder (Jurek & Neumann, 2018). Thus, a balanced OT/OTR signaling process is pivotal for mental health.

Effect of OT on social recognition is mediated by multiple neurotransmitter systems, such as brainstem serotonin (5-HT), noradrenaline and dopamine and different brain structures. In 121 healthy subjects, OT switched bilateral amygdala threat sensitization to desensitization, and this effect was significantly attenuated during decreased central serotonin signaling via pretreatment with acute tryptophan depletion (Liu et al., 2021a). Disturbing OT neuronal activity in the SON can activate the amygdala in rats (Liu et al., 2017), a brain region facilitating social anxiety and fear in humans (Meixner et al., 2019). Optogenetic excitation of PVN OT fibers excites noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus and augments attention to novel objects by co-release of OT and glutamate in male rats (Wang et al., 2021b). Fear-related behaviors are rigidly controlled by the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) while OT-mediated decrease in neuronal activity in the mPFC could facilitate social buffering in rats (Jung et al., 2021). In addition, corticostriatal connectivity in women (Bethlehem et al., 2017) and additional brain regions such as the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in both women and men (Maier et al., 2019), are also involved in OT effects on social recognition. It is likely that biochemical activity of OT neurons in the PVN and SON during social interactions increases significantly and that OT release in their terminals in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) increases excitatory drive onto reward-specific VTA dopamine neurons in the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex to reduce stress and fear, and thus enhances individuals’ prosocial behaviors as well as language functions.

OT functions are also manifested when intranasal administration of OT (IAO) is used in patients and in animal models. Pharmacologically, IAO can facilitate adaptive individuation/categorization face-processing in men (Liu et al., 2021b), detection accuracy of briefly-presented emotional stimuli including facial emotion recognition (Schulze et al., 2011), and interpersonal synchrony during dance (Josef et al., 2019), but reduce the negative emotional impact of jealousy in established romantic partners and thus, help maintenance of positive inter-personal relationships (Zheng et al., 2021b). Consistently, IAO can increase the pleasantness of social touch massage and neural responses in key regions involved in reward, social cognition, emotion and salience and in default mode networks in men (Chen et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021a). In animal studies, the underlying neurochemical processes are further explored. IAO can reduce the impairments in social novelty recognition and increase inhibitory synaptic inputs in the mPFC in rats with traumatic brain injury (Runyan et al., 2021). Notably, high doses of IAO may be more efficacious in alleviating negative symptoms in schizophrenia; however, that could be a pharmacological effect only since salivary OT levels have no clear correlation with the negative symptoms in humans (Sabe et al., 2021). Thus, studying on OT effects on higher brain functions should consider brain OT levels and OTR signaling efficiency rather than peripheral levels only, especially under pathological conditions.

Pro-Social Behavior

OT can influence parenting behavior, pair-bonding and affiliative behavior (de Jong & Neumann, 2018). People who grow up under conditions that are more adverse tend to have lower endogenous OT (Ellis et al., 2021). Thus, OT can increase social closeness, attachment and prosocial behaviors.

Parental behaviors are specific form of social behaviors. While OT is well-known as a key hormone in the establishment and maintenance of maternal behavior, it also promotes paternal behaviors (Yoshihara et al., 2018). Maternal behavior begins at the end of pregnancy before breastfeeding (Bridges, 2015) and is clearly associated with OT actions. In women who received epidural anesthesia, significantly higher mean salivary OT level appeared at 1–2 days after giving a birth than at 36–37 gestational weeks and OT levels became significantly lower at 4–5 days postpartum than that at 1–2 days postpartum. Postpartum maternity blues and fatigue were negatively correlated with salivary OT level at 4–5 days postpartum women (Shishido et al., 2021) and in primiparous postpartum California mice (Guoynes & Marler, 2021). In mandarin voles, microinjection of an OTR antagonist into the medial optic area (MPOA) of fathers can significantly reduce the total duration of paternal behavior, increase the latency to approach the pup and initiate paternal behavior (Yuan et al., 2019). Different from maternal behaviors, paternal behaviors rely on additional sensory signals from their mates, environment, and/or offspring to present paternal behavior (Horrell et al., 2019).

Disorders in OT/OTR signaling cause aberrant social behaviors as represented by ASDs, which has been illustrated in children (John & Jaeggi, 2021; Yang et al., 2017) and in mice (Kitagawa et al., 2021). OT-mediated GABA inhibition during the delivery process can protect individuals from chronic Cl− deficiency-associated ASDs in rodent offspring (Tyzio et al., 2014). Moreover, OT stimulates the expression of numerous genes involved in neurite outgrowth and glutamatergic synapse formation in mouse early development stages (Reichova et al., 2021), and thus the decreased OT actions could cause ASDs. Correspondingly, OT is accepted as an effective treatment for some core symptoms of ASDs, especially in the domain of social functioning revealed in a multilevel meta-analytic model of human data (Huang et al., 2021).

Paradoxically, many ASD subjects exhibit elevated but not decreased serum OT levels, which are correlated with childhood Autism Rating Scale score (Yang et al., 2017). This fact suggests that ASDs are associated with reduced OT/OTR signaling process but not blood OT levels. This finding is consistent with the fact that many neurodevelopmental disorders share common learning and behavioral impairments as well as dysregulation of OTR, such as abnormal DNA methylation in the OTR gene (Siu et al., 2021),

It adults with ASDs, there are higher levels of OTR gene methylation in the intron 1 area. This hypermethylation is related to clinical symptoms and to a hypoconnectivity between cortico-cortical areas involved in the theory of mind. The hypermethylation is also positively correlated to social responsiveness deficits in ASDs and to a hyperconnectivity between striatal and cortical brain areas in humans (Andari et al., 2020). Moreover, ASD severity is also associated with OTR SNP rs2254298 (Yang et al., 2017). In two ASD-associated OTR SNPs, rs2254298 and rs53576 have significant association with altered brain activity in the right supramarginal gyrus, which can be an important etiology of ASDs in adolescents (Uzefovsky et al., 2019). It was also reported that disease severity of the patients carrying GA and AA genotypes (GA/AA) of the SNP rs237902 is more severe compared to severity of GG genotype in ASD children (Ocakoglu et al., 2018). Thus, abnormal OTR signals in brain regions regulating social behaviors may underlie the etiology of ASDs. Taken together, disorders in OT/OTR signaling can cause ASD-associated aberrant social behaviors.

Effects of OT on social behaviors are related to OT actions on social brains directly or through the circulation. OT can increase the firing activity of GABAergic neurons in the dorsolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) by activation of OTR, which in turn inhibits output neurons from the BNST to central amygdala in male rats (Francesconi et al., 2021), thereby inhibiting cued fear. Moreover, circulating OT increases social interaction and maternal behaviors by acting on the mPFC after being taken up into the brain via the receptor for advanced glycation end-products, an OT-binding protein in male mice (Munesue et al., 2021). In the establishment of parental behaviors, the PVN likely occupies a central position in female rats (Munetomo et al., 2016) and male mice (Shabalova et al., 2020). It is known that PVN OT neurons project to the hippocampus, amygdala, ventral striatum, hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens (NAc, in the ventral striatum) and brainstem nuclei that are known as the key structures modulating social behaviors in rats (Ruthschilling et al., 2012) and in female rabbits (Jimenez et al., 2015). This histology feature sets a solid neural basis for OT to modulate parental behaviors. Notably, OT neurons in the SON are also implicated in maintenance of maternal behaviors as highlighted in a series of observations recently in rats (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021a; Li et al., 2021b; Li et al., 2021c). This is consistent with the structural connection of the SON neurons with the brain regions in rats (Zhang et al., 2021) that regulate maternal behaviors.

IAO but not intranasal VP promotes cooperative behaviors shown in a meta-analysis of human data (Yang et al., 2021), friendliness in horses (Lee & Yoon, 2021), and patience, cognitive flexibility in reversal learning and generosity under advantageous conditions in humans (Kapetaniou et al., 2021). OT also alleviates negative consequences of isolation in humans (Pfundmair & Echterhoff, 2021). In animal experiments, urinary OT concentrations following IAO are positively associated with dogs’ duration of social proximity and looking towards their owners (Pedretti et al., 2021). As a whole, OT can promote social behaviors directly or indirectly.

Learning and Memory

Learning and memory are modulated by OT. In humans, OT can enhance positive social memory while attenuating memory consolidation and retrieval of non-social stimuli like words and visual objects in humans (Guastella et al., 2008). Mothers with high salivary OT responsiveness recall previous positive social events with great detail and use uncontrollability attribution to explain such positive events (Tse et al., 2018), which may enhance the sensitivity and positive behaviors of parenting. Prenatal and early postnatal periods appear to be the most sensitive periods of brain development in mammals; action of various factors at these stages of brain development can result in neurodegeneration, memory impairment, and mood disorders at later periods of life. OT serves as an anti-stress, pro-angiogenic, and neurogenesis-controlling molecule contributing to dramatic changes in brain plasticity in early life stress, and thus prevents aberrant memory and behaviors (Lopatina et al., 2021). Women have higher plasma OT levels than men; older adults have higher plasma VP levels than young adults. Functionally, higher OT and lower VP levels are associated with faster sensorimotor processing speed, with sex and age moderating these effects including verbal memory (Plasencia et al., 2019). This integrated approach identifies variations in endogenous peripheral neuropeptide levels in humans, supporting their sex- and age-specific role as “difference makers” in attachment and cognition. In animal studies, vaginocervical stimulation promotes olfactory social recognition memory in female rats due to release of OT in the OBs during proestrus period (Larrazolo-Lopez et al., 2008). IAO has the capacity to compensate deficits in safety learning, along with a reduction in contextual fear and corticosterone levels shown in rats (Kreutzmann & Fendt, 2021). Obviously, the activity of the OT system is highly correlated with learning and memory in humans and animals. Notably, facilitatory effects of OT on long-term memory processes in healthy humans are based on emotional but not non-emotional stimuli (Brambilla et al., 2016).

OT selective facilitation of learning with social feedback is likely associated with enhanced responses and functional connectivity in emotional memory and reward processing regions in humans (Hu et al., 2015). As an essential carrier of memory process, the septohippocampal pathway is also the target of OT as shown in animal studies. OT can enhance cortical information transfer while simultaneously lowering background activity by increasing fast-spiking inhibitory interneuronal activity in the hippocampus shown in a mouse model of ASDs (Bertoni et al., 2021). In mice, OT can reverse amyloid-β-induced impairment of synaptic plasticity in hippocampus trough phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1 and 2 (pERK1/2) and Ca2+-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Takahashi et al., 2020). OT can alleviate stress-evoked hippocampal dysfunction and neuronal loss by inhibiting glucocorticoids-induced neuronal death in mouse primary hippocampal neurons (Latt et al., 2018).

In patients with schizophrenia, after 3 weeks of IAO treatment, there is no evidence for an amnestic effect; however, there is significantly better performance with IAO on several subtests of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT); namely total Recall trials, short delayed free recall and total recall discrimination (Feifel et al., 2012). IAO attenuates the normal bias in selecting the happy face accompanied by reduced activation in a network of brain regions that support mentalizing and processing of facial emotion, salience, aversion, uncertainty and ambiguity in social stimuli, including the amygdala, temporo-parietal junction, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus and insula (Wigton et al., 2022). IAO can increase ratings of the vividness of recalled memories during the social context only; however, individuals with elevated depressive symptoms also recall memories that are more negative following IAO relative to placebo and only in the non-social context (Wong et al., 2021a). This is consistent with previous proposal that OT has no effect on or even worsening of memory in non-emotional stimuli (Brambilla et al., 2016). In animal studies, IAO can compensate deficits in safety learning, along with a reduction in contextual fear and corticosterone levels as shown in rats under acoustic startle test (Kreutzmann & Fendt, 2021). IAO also overcomes maternal separation-induced impairment in long-term potentiation generation in the CA1 area of the hippocampus in rats (Joushi et al., 2021). These memory enhancing effects of IAO may contribute to the facilitation of social engagement and social interactions in patients with schizophrenia.

Anti-Depression and Anxiolysis

Disorders in OT secretion involve many psychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and ASDs (Yoon & Kim, 2020), which have been recognized in many studies of animals and humans. In young male soccer players, winners with higher OT levels have significantly lower cognitive anxiety and higher self-confidence scores than losers who have higher cortisol levels (La Fratta et al., 2021). In patients of premanifest and manifest Huntington's disease, OT levels are negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Fisher et al., 2021). Veterans who socialized with comrades more frequently have higher levels of urinary OT as well as less depressive symptoms. Social connectedness is a strong negative predictor of symptoms of both depression and suicidality (Warrener et al., 2021). Salivary OT after an episode of playing with parents has better reliabilities than baseline in children's social behavior (Torres et al., 2022). Numerous studies from humans and animals also indicate that OT uniquely facilitates adaptive fear but reduces maladaptive anxiety (Janecek & Dabrowska, 2019).

In general, the anti-depressive effect of OT is believed due to its regulating neuronal activity, influencing neuroplasticity and regeneration, altering neurotransmitter release, down-regulating hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, anti-inflammation, antioxidation, and genetic effects (Xie et al., 2022). As shown in studies on rats, excessive increase in glucocorticoids in chronic stress causes atrophy of the hippocampus (Warfvinge et al., 2020), while central OT can activate GABAA-receptors in the PVN and thus inhibit acute restraint stress-induced corticotrophin-releasing hormone mRNA expression (Bulbul et al., 2011) and the toxic effects of glucocorticoids (Matsushita et al., 2019). Interaction between 5-HT and OT systems is also important in these processes. The anxiolytic effects of OT in preclinical and clinical findings are not only related to the HPA axis, but also to the 5-HT system (Yoon & Kim, 2020). OT in the brain can facilitate 5-HT release within the median raphe nucleus and reduce anxiety-related behavior via OTRs in mice (Yoshida et al., 2009). This effect is associated with activation of 5-HT2A receptor (5-HT2A-R) and 5-HT2C-R heteroreceptor complexes in the raphe-hippocampal 5--HT neuron systems. This is because pathological blunting of the OTR promoters in 5-HT2A-R and especially in 5-HT2C-R heteroreceptor complexes promotes the development of depression and other types of psychiatric diseases involving disturbances in social behaviors in major depression (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2021). Recent studies in rats further highlight that social stress-evoked increase in hypothalamic OT secretion can account for maternal depression (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021f). Notably, IAO can benefit new mothers who report moderate sub-clinical levels of depression (Lindley Baron-Cohen et al., 2021). In rats, social stress-elicited maternal depression is reversible upon IAO (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021f). Functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation revealed that IAO can reduce amygdala hyper-activity in subjects with anxiety, and enhance connectivity between the amygdala and bilateral insula and middle cingulate gyrus in patients but not in healthy controls. Thus, the occurrence of depression and anxiety are due to disorders in OT-associated signaling processes while IAO has the potential to treat depression and anxiety.

Reward and Addiction

Social cognition and prosocial behaviors are closely associated with the rewarding mechanism. The reward system is mainly made up of the main dopamine pathways of the brain, especially the mesolimbic pathway from the VTA to NAc. This system is activated by rewarding (e.g. pair bonding, sexual contact, and positive social interaction) or reinforcing stimuli (e.g. addictive drugs). OT interacts with the mesocorticolimbic circuit and produces rewarding effects in response to rewarding stimuli (Dolen et al., 2013). It is likely that OT release from parvocellular division of the PVN and axonal collaterals of magnocellular OT neurons (Strathearn et al., 2019; Sundar et al., 2021) causes release of dopamine in the NAc and PVN while suppressing activity of the HPA axis and brain endogenous opioid systems (Hung et al., 2017), thereby facilitating rewards. This process can be enforced by serotonin transmission from raphe neurons to VTA to reinforce learning by serotonergic neuron co-transmitter glutamate (Courtiol et al., 2021). The rewarding functions of OT result from its acting within the NAc and VTA, and facilitate social reward and approach behavior. However, in aversive social contexts, additional pathways in the BNST play critical roles in mediating the effects of OT induction of avoidance of potentially dangerous social contexts (Steinman et al., 2019).

Addiction occurrence correlates with a hypodopaminergic dysfunction within the reward circuitry of the brain (Gardner, 2011) as well as malfunctions of the OT system. Acute cocaine treatment decreases OT levels in the hippocampus of rats (Johns et al., 1993). In mice, 14-day escalating-dose cocaine administration and 14-day withdrawal increase plasma corticosterone levels and OTR binding in the piriform cortex, lateral septum and amygdala. A specific cocaine withdrawal-induced increase in OTR binding is present in the medial septum (Georgiou et al., 2016). OT has protective effects against drug addiction by modulation of the initial response to drugs of abuse via shifting novelty processing from ventral to dorsal striatal structure (Tops et al., 2014), and attenuation of the development of dependence by reducing drug-elicited dopamine neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic circuit (Pedersen, 2017). OT also decreases withdrawal symptoms like facial fasciculation, convulsion, hypothermia, and anxiety-like and depression-like behavior during morphine, cocaine, nicotine, and alcohol abstinence (Bowen & Neumann, 2017). In addition, OT blocks drug reinstatement by blocking exposure to drug cues, drug priming, or stressful experience-evoked activation of the NAc (Cox et al., 2017) and exerts a general anti-stress effect (Ferrer-Perez et al., 2019). These views have gained supports from animal studies. IAO can decrease craving and relapse related to alcohol, cannabis, opioids, cocaine, or nicotine, etc (Houghton et al., 2021; Van Hedger et al., 2020). Activation of OTRs during recovery from opioid overdose could also eliminate or attenuate negative side effects associated with traditional opioid receptor antagonism (Brackley & Toney, 2021). These effects are associated with increased release of dopamine and glutamate and the activation of cortical and basal ganglia sites, which modulates the activity of mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons (Koob & Volkow, 2016). OT-reduced addictive behaviors is also related to restoring abnormal drug-induced changes in the glutamatergic system in NAc (Logan et al., 2021; Sundar et al., 2021). In addition, changes in synaptic transmission in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) are an important target in mediating alcohol dependence. Acute alcohol consumption facilitates GABAergic transmission in the CeA via both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms while decreasing ionotropic glutamate receptors-mediated transmissions; chronic alcohol drinking increases baseline GABAergic transmission and upregulatesN-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated transmission (Roberto et al., 2021). It is likely that drug-mediated and OT-driven social reward signals compete within the brain reward circuitry; while drugs suppress the activity of OT system, OT may enable the rewarding effects of prosocial behavior at the expense of drug-related rewards (Kovatsi & Nikolaou, 2019; Sundar et al., 2021). It is likely that under physiological condition, OT activates dopamine release while suppressing endogenous opioid release, and thus facilitation of opioids on dopamine release is negligible. However, drug-evoked addiction is accompanied with strong dopamine release while inhibiting OT neuronal activity. Once endogenous OT system is reactivated or exogenous OT is supplied, the rewarding effects of OT surpasses that of the additive substances, stable dopamine release is restored without the need of other substances. As a whole, OT can prevent stress and priming-induced relapse to drug seeking while inspiring rewarding to replace the impulse of addiction.

Negative Impacts on Higher Brain Functions

While OT is generally considered as a “cuddle chemical”, its adverse effects on social behaviors have also been identified. For example, OT may create intergroup conflict and violence because OT motivates in-group favoritism in humans (De Dreu et al., 2011) and in wild chimpanzees (Samuni et al., 2017). It is typically observed in maternal attacks toward unfamiliar male intruder in lactating rats (Li et al., 2021d). Individuals low in extraversion, trust-altruism, and openness to experience become significantly more anhedonia after receiving IAO relative to placebo, following imagery training of positive social outcomes in humans (Wong et al., 2021c). Similarly, individuals with elevated depressive symptoms recall memories that are more negative following IAO in the non-social context (Wong et al., 2021b). In addition, intrapartum OT application is positively associated with postnatal depressive symptoms in pregnant women (Tichelman et al., 2021). These findings implicate that abnormally increased OT bioavailability in vulnerable persons can evoke or enforce some negative social activities.

Mechanisms underlying differential effects of OT on intra-group cooperation and inter-group hostility have not been identified neurophysiologically. However, destructive effects of overly-produced OT in the hypothalamus could account for many of these adverse OT effects. Excessive OT in the hypothalamus can reduce OT release from axon terminals including the posterior pituitary and possibly in the brain identified in rat dams deprived of pups, which causes hypogalactia and maternal depression (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021f). This is because excessive OT causes post-excitation inhibition of OT neurons as shown in rats (Wang et al., 2006) and reduced OT neuronal excitability, which in turn reduces OT release into the blood and the brain via axonal terminals (Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, when cytosolic Ca2+-dependent OT release from the somata and dendrites of OT neurons increases (Ludwig et al., 2002), brain OT release through axon collaterals could be reduced, thereby causing depression and anxiety. Notably, IAO does not worsen maternal behaviors but alleviates maternal depression in rats (Li et al., 2021c; Li et al., 2021e; Liu et al., 2019). Since IAO tends to increase brain OT levels, these findings indicate that social stress does reduce extrahypothalamic OT release despite the increase in hypothalamic OT levels.

Instinctive Behaviors

OT can regulate defence, eating and drinking, sexual behavior, female reproduction, sleep, and other instinctive behaviors directly or by modulating activity of limbic system and other brain structures. Approaches mediating OT effects on the instinctive behaviors and somatosensory processes are presented in Figure 4 and Table 2.

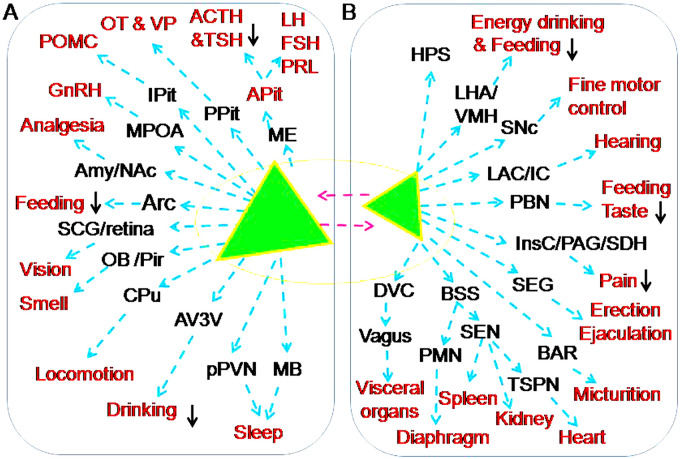

Figure 4.

Approaches mediating OT effects on the instinctive behaviors and somatosensory processes. A-B. Magnocellular OT neurons (A) and parvocellular OT neurons (B). The red font indicates a variety of targets of OT actions (please refer to the text for details). Abbreviations: Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), Anterior pituitary (APit), Corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), Luteinizing hormone (LH), Proopiomelanocortin (POMC), Prolactin (PRL), Thoracic sympathetic preganglionic neurons (TSPN), Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and Vasopressin (VP). Signs and other abbreviations are the same as Figure 2.

Table 2.

OT Effect on Instinctive Behavior and the Underlying Mechanisms.

| Category | Physiologic effects | Neural mechanisms | Pharmacological effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating and drinking | (1) Decrease food and drinking intake driven by energy; block consumption of toxic food and increase proactive control over feeding with overweight. | (2) Activate VMH and DVC; change activity of the LH and AN; block alcohol-induced DA release within the NAc; activate paraventricular thalamic neurons and suppress HPA axis. | (3) Improve feeding and social skills of infants with Prader-Willi syndrome; improves feeding of patients with anorexia nervosa and inhibit MCH neuronal activity in the LH. | (1) (Bowen et al., 2011; Gartner et al., 2018; Klockars et al., 2017; Pirnia et al., 2020; Plessow et al., 2021); (2) (Althammer & Grinevich, 2017; Klockars et al., 2017; McConn et al., 2019b; Peters et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2012); (3) (Russell et al., 2018; Tauber et al., 2017) |

| Reproduction | (4) Promote sex processes; stimulate HPG axis activity and ovulation; maintain normal menstruation and pregnancy; determine pulsatile OT release during parturition and breastfeeding and maternal behavior. | (5) Activate OT-DAergic neural pathways; increase GnRH release; activate PVN-VTA/SEG pathways; promote maturation of pulsatile OT release machinery involving the SON, PVN and MB as well as OT neurons-maternal behavior-regulating brain regions. | (6) Improve sexuality and its quality; accelerate parturition; facilitate conditional milk letdown; improve erectile dysfunction in aged people with Parkinson's disease; alleviate menstrual migraine and postpartum mood disorders. | (4) (Cera et al., 2021; Dekker et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2003; Higuchi & Okere, 2002); (5) (Bealer et al., 2010; Hou et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021d; Selvage & Johnston, 2004; Uta et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2013); (6) (Bealer et al., 2010; Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Cowley, 2005; Lassey et al., 2021; Sakakibara et al., 2010) |

| Anti-aging | (7) Reduction of OT secretion is accompanied with reduced general health levels, immunity, sexuality and cognitive activity. | (8) Reduced number of OT neurons makes all OT-associated brain functions decrease over time. | (9) Increase functional connectivity of neural circuits involved in social perception; improve emotional stability and body functions | (7) (Maestrini et al., 2018; Orihashi et al., 2020); (8) (Sannino et al., 2017; Zohrabi et al., 2020); (9) (Crowley et al., 2015; Sakakibara et al., 2010; Valdes-Hernandeza et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019b). |

| Nociception and analgesia | (10) OTR SNP increases pain; OT inhibits chronic somatic pains and visceral pain while reducing panic emotions to injury. | (11) Increase neural activity and neural connections between different brain areas; increase GABAergic signals in the brain and NA signals in spinal cord. | (12) Improve chronic pelvic and low back pains; inhibit the DRG, ACC, PAG, amygdala and NAc regions; increase social proximity and support and anxiolysis. | (10) (Lucas et al., 2021; Tsushima et al., 2021); (11) (Gamal-Eltrabily et al., 2020; Schneider et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2021); (12) (Flynn et al., 2021; Kreuder et al., 2019; Riem et al., 2021). |

| Sleep | (13) Improve sleep quality in postpartum women, cancer survivors, patients with ALS and women with a history of sexual assault. | (14) Inhibit HPA axis and melatonin secretion; cause anxiolytic, anti-depression, sedating effects and emotional stability; regulate MB activity. | (15) Increase respiratory rate and reduce obstructive event duration and oxygen desaturation in patients with sleep apnea. | (13) (Comasco et al., 2016; Gabery et al., 2021; Kendall-Tackett et al., 2013; Lipschitz et al., 2015); (14) (Comasco et al., 2016; Bulbul et al., 2011; Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1997; (15) (Jain et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2020). |

Abbreviations: ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis;AN, arcuate nucleus; DA, dopamine; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; DVC, dorsal vagal complex; GABA, ɣ-aminobutyric acid; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; HPA axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis; LH, lateral hypothalamus; MCH, melanin-concentrating hormone; MB, mammillary body complex; NA, norepinephrine; NAc, nucleus accumbens; OT, oxytocin; OTR, OT receptor; PAG, Periaqueductal gray; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; SEG, Spinal ejaculation generator; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SON, supraoptic nucleus; VMH, Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus; VP, vasopressin; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Eating and Drinking

Eating and drinking are important for the growth, energy supply, hydration and biochemical activities for physiological processes, and they are under the regulation of OT.

Eating

Food intake is driven by hunger that is associated with hypothalamic feeding center and vagal activity, which are modulated by OT. A systematic review including 26 studies of 912 participants showed that endogenous OT in nonclinical samples does not change significantly through altered diet or behaviors; in contrast, exogenous OT reduces indices of food intake in clinical and nonclinical samples (Skinner et al., 2018). For instance, IAO can increase proactive control over feeding behavior with overweight or obesity while evoking satiety signals and inhibiting eating in men (Plessow et al., 2021). In chickens, intracerebroventricular injection of OT dose-dependently reduces food intake and increases c-Fos expression in arcuate, dorsomedial nucleus, lateral hypothalamus, PVN, and ventromedial hypothalamus (McConn et al., 2019b). However, endogenous OT may mediate anorexigenic effects of other factors, such as that oleoylethanolamide causes satiety by activation of vagus and OT secretion in humans (Igarashi et al., 2021). Central OT serves as a mediator of other anorexic substances like l-tryptophan as shown in mice (Gartner et al., 2018). In mice, OT delivered into the intestinal tract decreases food intake to those who receive intraperitoneal administration. Oral OT also dramatically increases plasma OT levels and the expression of neural activation marker c-Fos protein in the PVN in mice (Maejima et al., 2020). These facts support the proposal that OT can reduce feeding.

OT neurons are glucose sensors. In rats, insulin activation of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase increases glucokinase-mediated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, which induces closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels, opens voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels, and stimulates OT release from the SON (Song et al., 2014). From the PVN, OT can activate brainstem vagal neurons in the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) including the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and nucleus tractus solitarius (Althammer & Grinevich, 2017). Activated DVC neurons can increase digestive fluid secretion in response to stomach distention and elevated osmolality, and block consumption of toxic foods in rats (Mitra et al., 2010). OT-decreased food intake driven by energy is also involved in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (Klockars et al., 2017) and the arcuate nucleus (Maejima et al., 2014) as shown in rats. OT directly evokes a substantial excitatory effect on presumptive GABA cells that contain melanin-concentrating hormone (Yao et al., 2012). Thus, OT also influences the secretion of melanin-concentrating hormone that can promote eating (Koop and Oster, 2021). By contrast, OT activation of paraventricular thalamic neurons promotes feeding motivation to attenuate stress-induced hypophagia but does not influence normal feeding in mice (Barrett et al., 2021). In addition, OT effects on appetite may involve CRH signaling in the hypothalamus in chickens (McConn et al., 2019b).

Notably, patients with Prader-Willi syndrome display poor feeding and social skills as infants and fewer hypothalamic OT neurons were documented in adults. IAO significantly increases acylated ghrelin and connectivity of the right superior orbitofrontal network that correlated with changes in sucking and behavior in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome and improves feeding and social skills (Tauber et al., 2017). In patients with anorexia nervosa, plasma OT levels are significantly reduced (Monteleone et al., 2016). IAO can reduce eating concern and cognitive rigidity while lowering salivary cortisol levels and reducing stress responsiveness to food and eating (Russell et al., 2018), thereby promoting nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa. Although such effects require replication with inclusion of more sensitive subjective measures, as a whole, OT functions as a homeostatic regulator of food consumption, ingestive behavior and energy metabolism.

Drinking

Drinking is essential for water supplement and volemic and hydromineral homeostasis and also important for taking energy drinking and enjoyment. While VP is the major hormones responsible for volemic and osmotic regulation in general (Smith et al., 2015), OT also modulate water and alcohol intake. In a single-case study, IAO for two six-week stages significantly reduced addiction severity index in five domains of medical status, occupational status, alcohol consumption, family status, and mental status (Pirnia et al., 2020). In prairie voles, intraperitoneal injection of OT can reduce 15% ethanol versus water consumption only in the first hour of access after treatment (Stevenson et al., 2017). In rats, intracerebroventricular OT application can completely block alcohol-induced dopamine release within the NAc (Peters et al., 2017). In female mice, disruptions in OT signaling may contribute to increased vulnerability to alcohol-associated addiction (Rodriguez et al., 2020). Moreover, OT may also mediate the regulation of water intake by other hormones, such as endothelin in rats (Samson et al., 1991) and serotonin in water-deprived rats (de Souza Villa et al., 2008). OT administration blocks the increase in voluntary ethanol consumption observed in socially defeated mice (Reguilon et al., 2021). It is likely that OT influence of alcohol consumption is mainly associated with its effect on social cognition and rewarding

Relative to the effect on food intake, endogenous OT inhibition of water intake in humans is weaker. Evidence of OT regulation of water intake is mainly from animal studies. As reported, mesotocin, an OT-like hormone of nonmammalian tetrapods and in most marsupials, decreases food intake and induces water intake; OTR antagonism can prevent mesotocin-mediated changes in food intake but not water intake in chicks (McConn et al., 2019a). Notably, in rats freely accessing to beer and water in their home cages, consumption of beer that has more calories (mainly from carbohydrates and alcohol) but not water was significantly less in the OT pre-treated rats (Bowen et al., 2011). This is in agreement with the finding that OT acting in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus of rats decreases food intake driven by energy (e.g. chow) but not by palatability (e.g. energy-dilute saccharin and sucrose solutions) (Klockars et al., 2017). Both beer/alcohol and food are energy-enriched substance while saccharin and sucrose solutions are palatable but energy-diluted. Thus, OT inhibitory effects on feeding and drinking are aimed at reducing the energy/caloric intake.

Reproduction-Associated Activity

OT has extensive regulatory effects on reproduction including sexual behaviors, menstrual cycle, parturition, lactation and aging.

Sexual activity

In both males and females, sexual activity at all stages is closely associated with OT actions. Plasma OT levels increase during sexual arousal and are significantly higher during orgasm/ejaculation than during prior baseline levels in both women and men (Cera et al., 2021; Dekker et al., 2021). In the brain, OT-dopaminergic neural pathways play a role not only in the erectile function and copulation, but also in the motivational and rewarding aspects of the anticipatory phase of sexual behavior. Deficits in OT system or its interactions with brain amine systems can result in loss of libido, impotence and lack of orgasm; conversely, over-activation of these systems may cause abnormal desire and multiple orgasms (Magon & Kalra, 2011). Postpartum women appear to experience a decrease in sexual interest possibly as a feature of a more generalized decrease in amygdala responsiveness to arousing stimuli, which also relates to the actions of OT (Rupp et al., 2013). Thus, appropriate OT levels and actions are essential to maintain the quality of sexual activity. Mechanistic studies in rats reveal that OT in the VTA from the PVN can induce penile erection (Melis et al., 2007) by promoting dopamine and glutamate release into the NAc, mPFC, amygdala, and other forebrain regions (Peris et al., 2017). The coordinated reactions of this OT-PVN-VTA-forebrain/spinal cord pathways make the sexual intercourse accompany with positive motivation and reward of sexual behavior (Magon & Kalra, 2011).

It seems contradictory that over-activation of the OT system causes abnormal desire and multiple orgasms while postpartum women have decreased sexual interest. However, it could be an outcome of reproductive trade-offs whereby mother-infant interactions activate the reward system by breastfeeding and bonding rather than by sexual drive. This notion is supported by the following observations (Gregory et al., 2015). 1) Postpartum women show lower sexual excitation, higher sexual inhibition, and lower sexual desire compared to nulliparous women; 2) Postpartum women show higher reward area activation to infant stimuli and nulliparous women show higher activation to sexual stimuli; and 3) IAO increases VTA but not NAc activation to both crying infant and sexual images for all women. Thus, OT may contribute to the altered reproductive priorities in postpartum women by increasing VTA activation to salient infant stimuli. In addition, the reduced estrogen level in postpartum may also decrease sexual drive, which can mask a transiently increased sexual desire elicited by OT pulse during suckling; however, breastfeeding the baby elicits the reward associated with women's emotional and physical satisfaction. Therefore, decreased sexual interest in breastfeeding mothers occurs, particularly in the first 1–2 months of postpartum period.

Menstruation

Menstrual cycle is a unique physiological phenomenon of women, driven by a series of changes in steroid hormone production and modulated by OT. Plasma OT is different at different stages of menstruation in ovulating women; compared to the luteal phase, OT levels are significantly high during ovulatory phase (Evans et al., 2003). A higher dose of OT could promote the growth of follicles as shown in postpartum buffaloes (Murtaza et al., 2021). In the hypothalamus, OT can stimulate the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, specifically at pre-ovulation stage as revealed in studies on cycling female rats (Selvage & Johnston, 2004). Consistently, during the proestrus, c-Fos expression in the SON increases significantly in association with facilitatory retraction of astrocytic processes in rats (Liu et al., 2016). Thus, OT secretion is closely associated with the neuroendocrine regulation of menstrual cycle.

Migraine is a major cause of disability worldwide, particularly among women aged 15–49 years. Overall, the incidence of migraine is threefold higher among women than men. In association with menstrual cycle, changes in estrogen and OT secretion can underlie migraines, which can be relieved by OT (Krause et al., 2021). Consistently, intravenous OT application can rapidly and temporally relieve the pain (Phillips et al., 2006). It is believed that cyclically released hypothalamic OT inhibits trigeminal neuronal excitability that can promote migraine pain. Coincident with decreased levels of both estrogen and OT during menstruation, magnesium and cholesterol, which positively modulate the affinity of OT for OTRs, also decrease. Thus, decreased OT alongside the reduction of trigeminal OTR expression and its affinity to OT promotes the activation of meningeal trigeminal nociceptors and increases the likelihood of an menstrual migraine attack (Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Tzabazis et al., 2017).

Pregnancy and parturition

During pregnancy, OT is not only important for the development and protection of fetus, but also critical for the maturation of maternal pulsatile OT secretion machinery during lactation. From the middle stage of gestation, central OTR binding is increased gradually in the SON, PVN, BNST and MPOA (Bealer et al., 2006); its blockade delays OT release and reduces milk yields during suckling in rats (Lipschitz et al., 2003) and in adult marmosets (Taylor & French, 2015). However, brain and blood OT levels do not change significantly during pregnancy until parturition. Functionally, activation of central OTR during gestation can cause morphological changes in magnocellular OT neurons, disinhibition of OT neurons in response to GABA, and adaptations in membrane response characteristics of OT neurons (Bealer et al., 2010). Resultantly, OT neurons become more reactive to neural inputs from the cervix, mammary glands and conditional stimuli from other sources.

When cervix or vaginal walls are stretched, neural signals reach the SON and PVN of the hypothalamus and OT neurons are activated; the resultant release of OT in a bolus initiates self-sustaining cycle of uterine contractions in rats (Higuchi & Okere, 2002). This neural-humoral reflex is called Ferguson reflex. In clinical practice, while using OT to assist parturition remains controversial (Litorp et al., 2021), induction of labor with a single-balloon catheter and OT results in a shorter time from insertion to delivery without increasing the rate of cesarean delivery (Lassey et al., 2021). Thus, how to activate the mechanism underlying Ferguson reflex is worthy of investigation for augmentation of labor.

Lactation

In all mammals, OT is an essential hormone that is used by mothers to provide milk to their offspring, as proved by OT knockout in mice (Winslow & Insel, 2002). Suckling-increased OT secretion is essential for the maintenance of maternal behaviors in the brain and the development of mammary glands in rats (Li et al., 2021e). In response to suckling stimulation, neural signals from the mammary glands reach the hypothalamus, trigger synchronized burst-like activation of OT neurons in the SON and PVN, and result in a pulsatile release of OT from the posterior pituitary and milk ejection (Wakerley et al., 1994). In association with the conventional suckling signals, the hypothalamus also receives signals from other sensory organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract, OBs, vagus and cortex-hypothalamus neural pathway, which allows conditioned OT release available (Uvnas-Moberg et al., 2014). In the activation of OT neurons, many extracellular and intracellular events occur, such as neurochemical environment (Brown et al., 2013), mobilization of OTR-signaling events (Hatton & Wang, 2008), intercellular junctional coupling (Wang et al., 2019a), astrocytic plasticity (Wang & Hatton, 2009), ion channel activity (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021c) identified in rats and others as reviewed (Hou et al., 2016). In addition, synchronization of burst firing of a large pool of OT involving those on bilateral sides of the hypothalamic OT neurons (Wang et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1997) is required to trigger full milk ejections in lactating rats. Such synchronized activity among OT neurons is determined by the activity of the mammillary body complex (Wang et al., 2013). In addition, OT release via activating the Ferguson reflex can increase the strength of the milk-ejection reflex shown in Holstein cattle (Morales et al., 2020). It indicates that different neurohumoral reflexes for OT release can be additive. It remains to clarify the neural circuit that controls the burst synchrony and the bolus of OT secretion.

In clinical trials, IAO has been found to promote breastfeeding in human (Cowley, 2005) and in lactating rats (Li et al., 2021c; Liu et al., 2019). In the neonatal unit setting, IAO can cause initial faster production and then become no difference from placebo treatment (Fewtrell et al., 2006). This finding is consistent with the finding in rat model that acute social stress-reduced OT neuronal activity, maternal depression and hypogalactia can recover spontaneously in chronic social stress (Li et al., 2021d). In cesarean rats that the reduced OT neuronal activity and aberrant maternal behavior at early postpartum stage can recover spontaneously as the elapsing of postpartum time while IAO can reverse depressive-like maternal behavior (Li et al., 2021e). These facts indicate that OT can promote breastfeeding by accelerating maturation of the machinery for the milk-ejection reflex through improving OT neuronal activity and maternal mood at the early postpartum stages.

Anti-Aging

Aging, as a process of negative growth and functional loss, is closely associated with alterations of OT actions. Around 35 years of age, blood OT levels in women decrease gradually (Maestrini et al., 2018). Moreover, there is a positive correlation between serum OT levels and the volume of the left hippocampus and amygdala among people aged 65 years and older (Orihashi et al., 2020). IAO can increase functional connectivity of neural circuits involved in action observation and social perception among old men (Valdes-Hernandeza et al., 2021). Decreased OT levels in elderly people are associated with reduced sex steroid production, socially emotional deficits, symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases, lower sexual ability, reduced vagal nervous tone and low muscle power (Sannino et al., 2017; Zohrabi et al., 2020). As shown in aged male rats, the number of parvocellular OT neurons and their OT release are significantly decreased in the PVN, DVC and substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord (Calza et al., 1990), which weakens the regulation of visceral activity.

By contrast, OT application can significantly improve erectile dysfunction in aged people with Parkinson's disease (Sakakibara et al., 2010), relieve aging-associated symptoms such as mood disorders in menopausal women (Crowley et al., 2015) and exert many other protective functions, such as reducing blood pressure (Wang et al., 2019b). Notably, chronic IAO has no significant impact on cardiovascular, urine, or serum measures. Relative to placebo, OT does not significantly increase the likelihood of adverse events. Chronic IAO appears safe and well-tolerated in generally healthy older men (Rung et al., 2021). These facts highlight the anti-aging effects and therapeutic potential of OT in aging-associated diseases.

Nociception and Analgesia

In addition to menstrual migraines as stated above, OT extensively suppresses nociception and exerts analgesia effects in humans and animals. Acute dental pain elevates salivary OT levels in pregnant women (Gurler et al., 2021). Women with the minor allele OTR rs53576 report 8.18-fold higher breast and nipple pain severity over time while women with the OTR rs2254298 minor allele also report allodynia (Lucas et al., 2021). This finding suggests that disorders in OT/OTR signaling can cause breast and nipple pain and its associated breastfeeding cessation. By contrast, IAO for 4 weeks can significantly improve chronic pelvic pain in 1/3 women observed (Flynn et al., 2021) and that IAO improves pains in patients with chronic low back pain (Schneider et al., 2020). In rats, neuropathic pain induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation upregulates OT synthesis in the SON and PVN as well as axon terminals of OT neurons in the posterior pituitary and spinal cord (Nishimura et al., 2019). These facts suggest that both magnocellular and parvocellular OT system are activated in response to nociceptive stimulation. Similar effect of OT is also identified in visceral pain in mice (Tsushima et al., 2021). OT analgesia effect can occur at the dorsal root ganglion (Zhu et al., 2021), anterior cingulate (Li et al., 2021 g), medial amygdala, CeA and NAc regions (Saito et al., 2021; Tsushima et al., 2021). In rats, increased release of opiate peptides from the periaqueductal gray area likely mediates OT analgesic effect (Yang et al., 2011). OT analgesic effect on chronic pain is associated with its increases of intrinsic neural activity of the medial frontal, parietal and occipital functional network and the associations between left NAc, left caudate nucleus and right amygdala with pain-specific psychometric scores (Schneider et al., 2020). Moreover, this OT effect involves increased GABAergic transmission at the cortical insular level and activating descending spinal noradrenergic mechanisms (Gamal-Eltrabily et al., 2020). In addition, this OT effect is also related to its suppressing anxiousness as shown in mice (Saito et al., 2021).

Clinical trials also support OT analgesia effects. IAO enhances the pain-relieving effects of social support in romantic couples (Kreuder et al., 2019). IAO enhancement of social proximity may be a mechanism underlying social influences on cardiovascular and mental health; however, IAO effects depend on interpersonal insecurities and may trigger discomfort in avoidantly attached individuals during experimentally-induced pains (Riem et al., 2021). Thus, OT exerts analgesia function for both somatic and visceral pains by activating both endogenous analgesia machinery and anxiolytic physiology.

Sleep

In humans, OT can increase the quality of sleep. Under basal and disease conditions, endogenous OT facilitates sleep in postpartum women (Comasco et al., 2016), among cancer survivors (Lipschitz et al., 2015) and in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Gabery et al., 2021). Women with a history of sexual assault have a number of sleep difficulties, increased risk of depression, and overall poorer subjective well-being. Sexual assault survivors who are breastfeeding and have pulsatile OT secretion are at lower risk on all of the sleep and depression parameters than sexual assault survivors who are mixed or formula feeding (Kendall-Tackett et al., 2013). By contrast, sleep deprivation can increase OT in the SON as shown in Syrian Hamsters (Knochel et al., 2021), which may antagonize the effect of awake-evoking factors.

The wakefulness-sleep cycle is related to dynamics of activating and inhibiting forebrain neurotransmitter systems that are modulated by rhythmic release of several hormones such as melatonin, cortisol and orexin (Koop and Oster, 2021). OT improvement of sleep is associated with its inhibition of the HPA axis (Bulbul et al., 2011) and melatonin secretion (Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1997). This effect is also associated with OT anxiolytic, anti-depression and sedating effects as well as its increasing emotional stability as shown in postpartum women (Comasco et al., 2016). In addition, OT fibers also innervate the mammillary body complex as shown in mice (Liao et al., 2020) that participates in sleep regulation, memory and many other functions (Benarroch et al., 2015). Thus, OT could modulate sleep by modulating the activity of mammillary body cells.

In clinical trials, a general sleep-promoting effect of OT remains to be established (Raymond et al., 2021). However, in clinical trials of obstructive sleep apnea patients, IAO has been confirmed to increase respiratory rate and reduce obstructive event duration and oxygen desaturation (Jain et al., 2017; Jain et al., 2020). Thus, while sleep-promoting effect of OT remains to be identified, IAO can be used to improve sleep problems in patients of obstructive sleep apnea.

Regulation of Sensorimotor Activity

OTRs distribute in extensive brain regions, which allows OT to modulate sensory and motor activity through acting on OTRs within sensory and motor centers. OT effects on sensorimotor activity involve autonomic neural activity, specific sensation and somatic sensorimotor activities (Figure 4).

Effects on Autonomic Nervous System

OT modulation of visceral activity is closely related to its regulation of autonomic nervous activity, such as cardiac rhythm, gastrointestinal tract contraction, breathing rhythm, and sweating, etc.

Parasympathetic nervous system

Heart rate variability (HRV) refers to variation in the interval between successive heart beats. Low HRV is an indicator of potential autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Listening to a slow-tempo music sequence increases the salivary OT concentration of participants whose high frequency component of the HRV increases while the heart rate decreases (Ooishi et al., 2017). In the postpartum period, multiparous women have higher saliva OT levels, higher parasympathetic nervous activity and lower physical stress index compared with primiparous women. In multiparous perinatal women, OT levels correlate positively with parasympathetic nervous activity, but negatively with physical stress index (Washio et al., 2020). In women at the third trimester of pregnancy and during low-risk labor, application of OT increases vagally mediated activity (Reyes-Lagos et al., 2015). IAO increases high frequency HRV (an index of cardio-parasympathetic activity) in men at clinical high risk for psychosis (Martins et al., 2020) and with 38 men either receiving 24 IU OT intranasally or a placebo spray. While accomplishing an emotion classification task, electrodermal responses are measured as an index of sympathetic activity. Moreover, heart rate changes recorded are additionally mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system. OT enhances differential heart rate responses to facial expressions as a function of the emotional valence, but has no effect on electrodermal activity or tonic measures of physiological arousal. These results indicate that OT specifically modulates phasic activity of the parasympathetic nervous system which potentially reflects an increased motivational value of facial expressions following OT treatment. These findings suggest that anxiolytic effects of OT are not reflected in short-term sympathetic responses and may even be a consequence rather than a prerequisite of improved social information processing (Gamer & Buchel, 2012). In rats of lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia, respiratory rate is elevated and mean R-R interval is reduced, and OT administration significantly attenuates the hyperventilation and restores the values of the mean R-R interval, supporting that OT promotes cardiac cholinergic autonomic coupling (Elorza-Avila et al., 2017). Histologically, OT fibers from the PVN likely innervate the DVC in the brainstem and the intermediolateral and sacral parasympathetic nuclei in rats (Althammer & Grinevich, 2017), which allow OT to regulate visceral activities and maintain homeostasis of the internal environment.

Among these neural connections, the PVN-DVC-vagal-organ pathway is a major approach for OT regulation of visceral activities. As shown in rats, activation of this pathway can increase insulin levels (Bjorkstrand et al., 1996), reduce heart rate and cardiac contractility (Houshmand et al., 2015), suppress food and water intake of the digestive system (Niimi et al., 2001), slow gastric emptying (Tolentino et al., 2021) and regulate hepatic metabolic activity (Dos Santos et al., 2021). Recently, it is also reported that activation of brain OT neurons inhibits colitis-associated cancer progression in association of suppression of sympathetic neuronal activity in the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion as shown in mice (Pan et al., 2021). Thus, OT can modulate visceral activities by increasing parasympathetic nervous activity although the parasympathetic outflow function of endogenous OT remains to be studied.

Sympathetic nervous system

Sympathetic nerves arise from the intermediolateral nucleus of the lateral grey column from the first thoracic vertebra of the vertebral column to the second or third lumbar vertebra. Their activities are regulated by many sites or centers in the brain, such as the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), PVN, lateral hypothalamus and limbic system (Kerman et al., 2006). OT fibers are present in these sites and conditionally regulate their activities and sympathetic neural outflows.

On the one hand, the OT system has inhibitory influence on sympathetic activity by decreasing social stress and the HPA axis activity in general (Moberg et al., 2020). In early postpartum mothers, although plasma OT did not increase reliably from pre-stress levels during stressors, greater overall OT level is related to greater vasodilatation and cardiac stroke volume responses to reduction in heart rate and to the cold pressor, as well as to lower plasma norepinephrine and higher prolactin levels (Grewen & Light, 2011). Consistently, in OT knockout mice, there are higher sympathetic tone and higher heart rate (Michelini et al., 2003).

On the other hand, there are also reports supporting OT activation of sympathetic activity. IAO can reduce engagement of the parasympathetic nervous system in patients of chronic neck and shoulder pain and under cognitive stress (Tracy et al., 2018), which are accompanied with relative increase in sympathetic outflows. Histologically, 80% RVLM-projecting PVN cells in rats are OT neurons (Lee et al., 2013) and microinjection of OT into rat RVLM increases sympathetic outflows as indicated by blood pressure increase (Ishizuka et al., 1993). It is also believed that a population of OT neurons in the PVN projects to sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the upper thoracic spinal cord; their activation by OT selectively increases heart rate in rats (Yang et al., 2009). Moreover, OT is a specific component of the sympathetic pathway innervating the spleen in rats (MacNeil et al., 2003). In addition, blocking OTRs attenuates the increase in renal nerve activity induced by intracerebral application of prostaglandin E2 when measured 10 and 30 min post-injection. However, it remains to exclude a pharmacological effect of OT in its activation of sympathetic nervous activity. This is because of the finding that PVN-induced activation of sympathetic activity to the kidney is mainly mediated by glutamate or VP neurons whereas dopamine via Dl receptors may mediate some of the PVN inhibitory effects identified in rats (Yang et al., 2002).

As a whole, OT effects on the autonomic nervous system are not a simply inhibition or excitation, but at maintaining homeostasis of the internal environment. Thus, the PVN-DVC pathway can be prevailing at rest whereas PVN-sympathetic pathway becomes dominant when a stressful environment is present. In addition, this differential function should result from activation of different neural connections between higher brain centers and different sub-population of OT neurons in the PVN. This possibility remains to be validated in experimental studies, particularly involving humans.

Specific Sensation

OT neurons have extensive neural connections with specific sensory organs that also express OTRs. Correspondingly, OT can influence the sense of smell, vision, hearing, taste, and others.

Olfaction

Olfaction deficits are common in schizophrenia and correlate with negative symptoms and low social drive. Individuals with schizophrenia report experiencing more negative emotionality than controls in response to the olfactory stimuli. Lower plasma OT levels are associated with poorer accuracy for pleasant and unpleasant odors and greater severity of asociality among them (Strauss et al., 2015). Olfactory deficits can be improved by IAO in patients with schizophrenia (Woolley et al., 2015). In animal study, intrabulbar infusions of OT induced full maternal behavior in female rats tested within two hours of pup exposure while intrabulbar infusions of OTR antagonist during delivery blocks the occurrence of maternal behavior (Yu et al., 1996a). It has been found that hypothalamic OT could directly modulate main OB cellular activity following release from neural terminals from OT neurons. It has been reported that high-frequency stimulation of the PVN produced inhibitory responses in 80% of mitral cells and excitatory responses in 74% of inhibitory granule cells tested; both responses were blocked by infusion of an OTR antagonist into the OBs and mimicked by intracerebroventricular OT applications (Yu et al., 1996b). OT activation of granule cells is associated with its increasing excitatory postsynaptic currents as shown in granule cell cultures (Osako et al., 2001), suggesting increased glutamatergic synaptic transmission from mitral/tufted cells to granule cells. However, in cultured mitral/tufted cells, OT also reduces the frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (Osako et al., 2000). Consistently, in mouse accessory OBs, OT can modulate glutamatergic NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation at the mitral-to-granule cell synapse (Fang et al., 2008). Thus, OT can function as a gate to control information flows within the local OB neural circuits and from the OBs to the brain regions regulating maternal behavior.

Similarly, intrabulbar OT can act to preserve social recognition responses (Dluzen et al., 1998) by increasing norepinephrine release and activating alpha-adrenoceptors (Dluzen et al., 2000). Interestingly, intrabulbar OT infusion can increase mouse performance in a social interaction task, enhance odor-evoked responses of mitral/tufted cells and neural discrimination of odors but reduce the spontaneous firing rate of mitral/tufted cells. OT also decreases odor-evoked calcium responses specifically in granule cells and modulates ATP-sensitive potassium channels to exert inhibitory effect on mitral cell activity through OTR-Gq-PLC-IP3 signalling pathway (Sun et al., 2021). By contrast, excitatory outputs of olfactory nerves from mitral cells can mediate effects of IAO on the brain activity including OT neurons in the SON in rats (Liu et al., 2017; Meddle et al., 2000; Yeomans et al., 2021). It is likely that OT modulates social interaction including social memory and maternal behavior by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio of odor responses in mitral cells.

Hearing