Abstract

BACKGROUND

Bow hunter’s syndrome (BHS) is a rare but surgically treatable cause of vertebrobasilar insufficiency due to dynamic rotational occlusion of the vertebral artery. Typically, patients present with posterior circulation transient ischaemic symptoms such as presyncope, syncope, vertigo, diplopia, and horizontal nystagmus, but irreversible deficits, including medullary and cerebellar infarctions, have also been described.

CASE SUMMARY

A 70-year-old patient presented an acute onset of vertigo and gait instability triggered by right head rotation. His medical history included previous episodes of unilateral left neck and occipital pain followed by light-headedness, sweating, and blurred vision when turning his head, and these episodes were associated with severe degenerative changes in the atlanto-dens and left atlanto-axial facet joints and right rotation of the C2 cervical vertebrae. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed the presence of acute bilateral cerebellar ischaemic lesions, while static vascular imaging did not reveal any vertebral artery abnormalities. Dynamic ultrasonography and angiography were performed and confirmed the presence of a dynamic occlusion of the vertebral artery V3-V4 segment when the head was rotated to the right secondary to left C1-C2 bone spur compression. Surgical decompression led to complete resolution of paroxysmal symptoms without neurological sequelae.

CONCLUSION

BHS should be considered in cases of repeated posterior circulation transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke, particularly when associated with high cervical spine abnormalities.

Keywords: Bow hunter’s syndrome, Stroke, Non-invasive duplex ultrasonography, Dynamic angiography, Neurosurgery, Case report

Core Tip: Bow hunter’s syndrome (BHS) represents a paradigmatic example of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. It is an uncommon but potentially harmful condition whose clinical manifestations encompass posterior circulation transient ischaemic symptoms and irreversible deficits, including medullary and cerebellar infarctions. We present herein a case of BHS resulting from rotational occlusion of a nondominant left vertebral artery by C1-C2 bone spur compression that was successfully treated with posterior cervical decompression. This case highlights the role of dynamic vertebral digital subtraction angiography and neurosurgery in BHS diagnosis and treatment, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Bow hunter’s syndrome (BHS) or rotational vertebral artery occlusion syndrome (RVAO) is an uncommon case of vertebrobasilar stroke and represents a paradigmatic example of vertebrobasilar circulation insufficiency (VBI) resulting from rotational stenosis or dynamic occlusion of a dominant vertebral artery (VA)[1]. Rare cases of nondominant VA involvement[2-4] or bilateral vertebral compression[5-7] have also been reported. The pathogenesis of BHS is strictly associated with the anatomical course of VAs, which can be affected by head motion and compressed by several cervical structures, typically at the atlantoaxial level[1]. Therefore, repetitive shear stress, thrombus formation due to blood flow stasis with artery-to artery embolism and vessel dissection have been suggested as possible underlying mechanisms[8]. Due to the limited number of cases described in literature, the exact incidence of BHS is still unknown[8]. Male in the 5th-7th decade of life with concurrent cerebrovascular risk factors represent the prototype of BHS patients[1,8-10], nevertheless cases in pediatric age have been described too[11-13]. Since its first description in 1978[14], several conditions have been listed among BHS etiologies, such as osteophytes, fibrous bands, or lateral disc herniation. Other less common causes included neck muscle hypertrophy[15], cervical tumours[16,17] and contralateral/ipsilateral VA dissection with or without pseudoaneurysm[18-20]. Clinical manifestations can range from posterior circulation transient ischaemic symptoms (e.g., dizziness and vertigo[21,22], isolated or transitional nystagmus[23,24] and loss of consciousness) to irreversible deficits, including medullary and cerebellar infarctions, depending on the amount of compensatory flow and the duration of dynamic occlusion. Consequently, all other possible etiologies of posterior ischaemic stroke[25] as well as episodic causes of vestibular disorders and vertigo[26,27] should be included in the differential diagnosis of BHS. Diagnosis relies mainly on dynamic digital subtraction cerebral angiography (DSA)[1,10], even if a diagnostic algorithm based on non-invasive duplex ultrasonography has been recently proposed[28]. Finally, BHS treatment relies either on conservative or neurosurgical therapeutical approaches[29].

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 70-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of vertigo and gait instability triggered by rotating his head to the right. The main differences in comparison with previous episodes of imbalance triggered by head rotation were the duration of symptoms (several hours) and the presence of mild signs of cerebellar involvement at the neurological examination.

History of present illness

He denied having any cervical trauma or injures. His vascular risk factors also included moderate smoking, dyslipidaemia and arterial hypertension.

History of past illness

His medical history included peripheral chronic arteriopathy and previous episodes of left neck and occipital pain followed by light-headedness, sweating and blurred vision triggered by rotating his head and associated with severe spondylotic changes in the cervical spine and foramen magnum stenosis. Previously performed cervical spine computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified degenerative changes in the atlantoaxial and left-axial facet joints with right rotation of the C2 cervical vertebrae (Figure 1A and B). However, given the imbalance between perioperative risks and clinical paucisintomaticity, a neurosurgical approach was discouraged.

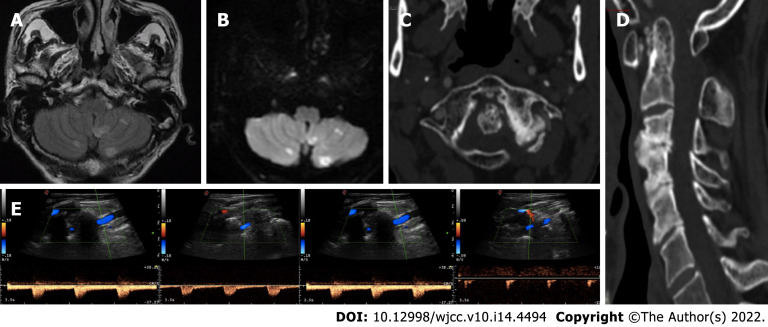

Figure 1.

Neuroradiological and neurosonological evaluation. A and B: Axial fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) brain magnetic resonance imaging sequences with subacute bilateral cerebellar ischaemic lesions involving the area supplied by the posterior inferior cerebellar artery; C and D: Axial and sagittal cervical computed tomography scan showing marked degenerative joint alterations with atlo-axial instability and retroposition of dens, spinal canal stenosis and ankilosis of lateral left zygo-apophisal joints with underlying congenital partial atlo-occipital fusion; E: Vertebral ultrasound examination documenting regular blood flow in the left VA in the neutral position (left side) and “stump flow” demodulation in both the V1-V2 and V3-V4 segments (right side) in cases of slight contralateral head rotation (20°).

Personal and family history

No other relevant events were reported in his personal and family history.

Physical examination

At hospital admission, his neurological examination was normal except for a significant left lateropulsion in the Romberg position and a wide-based gait. No other signs of brainstem involvement were appreciable.

Laboratory examinations

Routine blood tests were unremarkable, apart from moderate dyslipidaemia as an additional cerebrovascular risk factor.

Imaging examinations

Static neuroimaging: Brain CT and MRI identified subacute bilateral cerebellar ischaemic lesions (with left prevalence) involving the area supplied by the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, while magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed right VA dominance. Moderate carotid atheromasia was also appreciable. Ultrasound examination of the neck arteries in the neutral position and CT angiography (CTA) did not show haemodynamic abnormalities in the Vas and excluded signs of arterial dissections or severe stenosis of the vertebrobasilar system, confirming a right VA predominance (Figure 1C and D). Conversely, ultrasound examination of the left VA in both the V1-V2 and V3-V4 segments with slight contralateral head rotation (approximately 20°) showed a Doppler waveform demodulation known as stump flow, which suggested distal VA steno-occlusion (Figure 1E).

Dynamic ultrasonography and angiography

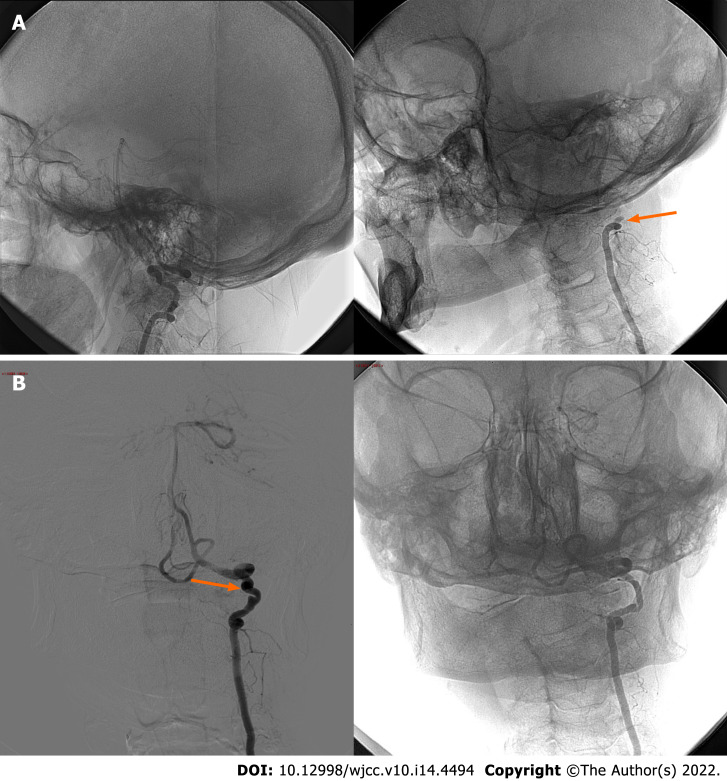

After having his head mobilized following CTA execution, the patient presented an episode of loss of consciousness without prodromic symptoms. Thus, dynamic causes of vertebral occlusion and related symptoms were considered, and the absence of a flow signal in the left V3-V4 VA was documented by ultrasound examination while the head was turned to the right. Dynamic vertebral DSA with anteroposterior and lateral projections secondary to left C1-C2 bone spur compression confirmed the clinical suspicion of BHS[1,10]. Moreover, the left V3 and VA appeared elongated and exhibited irregular luminal injection and focal parietal ectasia, probably due to repeated microtrauma of the artery wall (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Digital subtraction angiography. A: Lateral cerebral angiography projections without stenosis of the left vertebral artery in the neutral position (left side) and with complete occlusion of the V3 segment at the C2 Level upon turning the head to the right at 40° (right side; arrow); B: Anteroposterior cerebral angiography projections confirming the dynamic occlusion of the left VA in case of right head rotation (right side). Please note left VA irregular luminal injection and focal parietal ectasia in the neutral position (left side; arrow).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the case presented was left dynamic vertebral artery occlusion (Bow Hunter’s syndrome) resulting from left C1-C2 bone spur compression.

TREATMENT

After neurosurgical revaluation, surgical decompression of the left VA at the C1-C2 Level was performed, including removal of the aforementioned C1-C2 osteophyte as well as partial removal of the C1 posterior arch and opening of the transverse foramen through a posterior approach (Video).

The patient was placed in the three-quarter prone position on the right side, with the head slightly flexed via pin fixation (segment 1). Through a hockey stick incision in the left retromastoid region, the occipital squama, foramen magnum and C1-C2 posterior arches were sequentially exposed (segment 2). After identification and isolation of the left V3 segment above C1, a lateral dissection C1-C2 bone spur (BS) was exposed and gradually removed (segments 3-6). Finally, the C1 posterior arch and its transverse foramen were partially opened until the V2 and V3 segments were isolated (segments 7-8). Postoperative cervical CT excluded signs of vertebral instability, confirming the marked degenerative joint alterations at the atlo-axials and atlo-occipital levels previously described.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient tolerated the procedure well, and on day 5 post surgery, cervical spine CT excluded signs of vertebral instability. He was discharged with antiplatelet treatment as a secondary prevention due to several vascular risks.

A follow-up angiography 12 months after the procedure documented no evidence of significant stenosis, compression or occlusion of the left VA along its course either in the neutral position or in cases of bilateral head turning. The patient also denied any other focal neurological deficit and remained completely asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

BHS is a rare cause of stroke that represents a paradigmatic example of VBI. This term, which was first coined in the 1950’s[30], has been widely adopted for decades to denote a pattern of recurrent symptomatic ischaemia to regions irrigated by posterior circulation, reflecting hypoperfusion of poorly collateralized structures due to haemodynamically significant stenosis or artery-to artery embolism[31]. However, it has recently been argued that VBI should actually be limited to vertebrobasilar ischaemia related to direct vertebral artery compression induced by head movement, reflecting the physiopathological mechanism occurring in BHS[32]. Specifically, compression has frequently been noted to occur at the most dynamic portions of VAs, either C5-C7 (V1-V2)[33] or C1-C2 (V3-V4)[1,10,34]. In these sections, the vessel is progressively stretched between the two transverse foramina during head turning, becoming particularly susceptible to microtrauma.

Differential diagnosis may potentially be difficult, leading to unrecognized cases with harmful consequences. Indeed, posterior circulation Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke can result in a considerable risk of stroke recurrence[35], especially in cases of vertebrobasilar stenosis[36,37] or in combination with other cerebrovascular risks. BHS is mainly related to dominant VA compression, whereas the contralateral vessel is frequently hypoplastic, atresic and stenotic[38]. These predisposing factors, which can lead to the limitation of collateral flow during head turning, represent a potential clue for further evaluations of cases where BHS is highly suspected, such as patients with recurrent posterior TIA/stroke and cervical spine abnormalities. In cases of nondominant VA-induced BHS, Iida et al[3] proposed head rotation-induced downbeating nystagmus (DBN) as another clinical clue, although we did not observe DBN in our patient. Furthermore, instrumental investigations may lead to inconclusive results if inadequately performed. Indeed, a pathognomonic finding in BHS is the improvement in symptoms when the patient is in a neutral position, since the Vas are not compressed. Therefore, diagnosis with static vascular imaging (e.g., CTA and MRA) is not feasible. Dynamic ultrasound is a non-invasive and potentially useful diagnostic tool, but it can lead to false results even when performed in highly specialized neurological institutes[1]. However, when BHS is suspected, a number of authors have recommended DSA as the definitive diagnostic modality[1,29,33,34].

Proper recognition is of the utmost importance, as secondary stroke prevention should start with deciphering the most likely stroke mechanism to establish tailored and potentially resolutive therapies[39]. Regarding treatment, due to the paucity of BHS reports in the neurological and neurosurgical literature, international guidelines for its management have not yet been validated. According to the underlying etiology, a management algorithm including conservative and surgical treatment has been proposed[29]. On the one hand, conservative treatment methods include avoidance of head rotation, cervical collars and antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Despite its safety, a conservative approach does not guarantee complete clinical remission or allow long-term outcomes to be assessed. On the other hand, a surgical approach can lead to definitive results and is advised in cases of high and impending cerebrovascular risk[1,29]. In particular, Zaidi et al[1] suggested that patients should be offered surgical intervention when (1) Symptoms interfere with quality of life; (2) there is angiographic evidence of a severe reduction in VA flow during head rotation combined with insufficient compensatory collateral circulation; and (3) medical treatment has failed. Depending on the mechanism of VA occlusion, cervical fusion or decompression represent the most well-known surgical methods, which share the same success rate in achieving the resolution of symptoms[40]. However, the question of which type of surgical approach should be performed (e.g., posterior[1,41], anterior or antero-lateral[19,42,43]) is still debated. Independent of the surgical approach, in a recent review of 153 patients with BHS, surgery was associated with a higher number of favourable outcomes than those with conservative treatment[10]. Finally, endovascular approaches have been proposed in recent years, with limited evidence and experience in comparison to surgery[44-46]. However, as suggested by a few authors, a multidisciplinary approach could be used in selected cases to further increase the efficacy of surgical decompression[47-50].

CONCLUSION

Bow hunter’s syndrome is a rare, potentially severe but treatable condition that should be considered in the diagnostic flow-chart for repeated posterior circulation TIA or ischaemic stroke, especially when associated with high cervical spine abnormalities. Furthermore, our case proves the safety and long-term outcomes of surgery in BHS management, further demonstrating its appropriate indication for selected patients.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient provided informed consent for video and image acquisition as well as for data storage in the medical record during hospitalization.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 23, 2021

First decision: January 12, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Byeon H, South Korea; Tanaka M, Hungary S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Niccolò Orlandi, Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, Center for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41121, Italy.

Francesco Cavallieri, Neurology Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy; Clinical and Experimental Medicine PhD Program, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41121, Italy.

Ilaria Grisendi, Neurology Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

Antonio Romano, Neurosurgery Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

Reza Ghadirpour, Neurosurgery Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

Manuela Napoli, Neuroradiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Medicine, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 41123, Italy.

Claudio Moratti, Neuroradiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Medicine, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 41123, Italy.

Matteo Zanichelli, Neuroradiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Medicine, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 41123, Italy.

Rosario Pascarella, Neuroradiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Medicine, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 41123, Italy.

Franco Valzania, Neurology Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

Marialuisa Zedde, Neurology Unit, Neuromotor and Rehabilitation Department, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy. marialuisa.zedde@ausl.re.it.

References

- 1.Zaidi HA, Albuquerque FC, Chowdhry SA, Zabramski JM, Ducruet AF, Spetzler RF. Diagnosis and management of bow hunter's syndrome: 15-year experience at barrow neurological institute. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuyama T, Morimoto T, Sakaki T. Bow Hunter's stroke caused by a nondominant vertebral artery occlusion: case report. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1393–1395. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iida Y, Murata H, Johkura K, Higashida T, Tanaka T, Tateishi K. Bow Hunter's Syndrome by Nondominant Vertebral Artery Compression: A Case Report, Literature Review, and Significance of Downbeat Nystagmus as the Diagnostic Clue. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Stefano V, Colasurdo M, Onofrj M, Caulo M, De Angelis MV. Recurrent stereotyped TIAs: atypical Bow Hunter's syndrome due to compression of non-dominant vertebral artery terminating in PICA. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1941–1944. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healy AT, Lee BS, Walsh K, Bain MD, Krishnaney AA. Bow hunter's syndrome secondary to bilateral dynamic vertebral artery compression. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toluian T, Volterra D, Gioppo A, Rigamonti P. Bow Hunter's syndrome: an unusual case of bilateral dynamic occlusion of vertebral arteries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:1131–1132. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming JB, Vora TK, Harrigan MR. Rare case of bilateral vertebral artery stenosis caused by C4-5 spondylotic changes manifesting with bilateral bow hunter's syndrome. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:799.E1–799.E5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan G, Xu J, Shi J, Cao Y. Advances in the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment of Bow Hunter's Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Interv Neurol. 2016;5:29–38. doi: 10.1159/000444306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz R, Donoso R, Weissman K. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion ("bow hunter syndrome") Eur Spine J. 2021;30:1440–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi V, Rawls A, Moore O, Victorica B, Khan S, Saravanapavan P, Midivelli S, Raviraj P, Khanna A, Bidari S, Hedna VS. Rare Etiology of Bow Hunter's Syndrome and Systematic Review of Literature. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2015;8:7–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golomb MR, Ducis KA, Martinez ML. Bow Hunter's Syndrome in Children: A Review of the Literature and Presentation of a New Case in a 12-Year-Old Girl. J Child Neurol. 2020;35:767–772. doi: 10.1177/0883073820927108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patankar AP. Vertebro-basilar stroke due to Bow-Hunter syndrome: an unusual presentation of rotatory atlanto-axial subluxation in a fourteen year old. Br J Neurosurg. 2019:1–3. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2019.1668538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qashqari H, Bhathal I, Pulcine E, Muthusami P, Moharir M, MacGregor D, Kulkarni A, Dlamini N. Bow hunter syndrome: A rare yet important etiology of posterior circulation stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorensen BF. Bow hunter's stroke. Neurosurgery. 1978;2:259–261. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197805000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar J, Wolfe SQ, Ching BH, Kellicut DC. Bow hunter's syndrome causing vertebrobasilar insufficiency in a young man with neck muscle hypertrophy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:1032.e1–1032.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori M, Yamahata H, Yamaguchi S, Niiro T, Atsuchi M, Kasuya J, Tokimura H, Arita K. Bow-hunter's syndrome due to left C7 schwannoma in a patient with bilateral absence of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. J Orthop Sci. 2019;24:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haimoto S, Nishimura Y, Hara M, Yamamoto Y, Fukuoka T, Fukuyama R, Wakabayashi T, Ginsberg HJ. Surgical Treatment of Rotational Vertebral Artery Syndrome Induced by Spinal Tumor: A Case Report and Literature Review. NMC Case Rep J. 2017;4:101–105. doi: 10.2176/nmccrj.cr.2016-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi Y, Nagasawa H, Yamakawa T, Kato T. Bow hunter's syndrome after contralateral vertebral artery dissection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:916.e7–916.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez RN, Wipplinger C, Navarro-Ramirez R, Patsalides A, Tsiouris AJ, Stieg PE, Kirnaz S, Schmidt FA, Härtl R. Bow Hunter Syndrome with Associated Pseudoaneurysm. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue S, Shi H, Du X, Ma X. Bow Hunter's syndrome combined with ipsilateral vertebral artery dissection/pseudoaneurysm: case study and literature review. Br J Neurosurg. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1718604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt T, Baloh RW. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion: a clinical entity or various syndromes? Neurology. 2005;65:1156–1157. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183154.93624.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergl PA. Provoked Dizziness from Bow Hunter's Syndrome. Am J Med. 2017;130:e375–e378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum CA, Kasner SE. Transient Ischemic Attacks Presenting with Dizziness or Vertigo. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:629–642, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura Y, Toi T, Ogawa Y, Oshima T, Saito Y. Transitional nystagmus in a Bow Hunter's Syndrome case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:435. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-02009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Front Neurol. 2014;5:30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karatas M. Central vertigo and dizziness: epidemiology, differential diagnosis, and common causes. Neurologist. 2008;14:355–364. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31817533a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman-Toker DE, Edlow JA. TiTrATE: A Novel, Evidence-Based Approach to Diagnosing Acute Dizziness and Vertigo. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:577–599, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimihira L, Yoshimoto T, Ihara M. New diagnostic algorithm for detection of covert Bow Hunter's Syndrome. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:2162–2165. doi: 10.7150/ijms.56442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornelius JF, George B, N'dri Oka D, Spiriev T, Steiger HJ, Hänggi D. Bow-hunter's syndrome caused by dynamic vertebral artery stenosis at the cranio-cervical junction--a management algorithm based on a systematic review and a clinical series. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:127–35; discussion 135. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siekert RG, Millikan CH. Syndrome of intermittent insufficiency of the basilar arterial system. Neurology. 1955;5:625–630. doi: 10.1212/wnl.5.9.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stayman A, Nogueira RG, Gupta R. Diagnosis and management of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2013;15:240–251. doi: 10.1007/s11936-013-0228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandratheva A, Werring D, Kaski D. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency: an insufficient term that should be retired. Pract Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2020-002668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jost GF, Dailey AT. Bow hunter's syndrome revisited: 2 new cases and literature review of 124 cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38:E7. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuyama T, Morimoto T, Sakaki T. Comparison of C1-2 posterior fusion and decompression of the vertebral artery in the treatment of bow hunter's stroke. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:619–623. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.4.0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Prognosis of vertebrobasilar transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke. Brain. 2003;126:1940–1954. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulli G, Khan S, Markus HS. Vertebrobasilar stenosis predicts high early recurrent stroke risk in posterior circulation stroke and TIA. Stroke. 2009;40:2732–2737. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.553859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merwick Á, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. BMJ. 2014;348:g3175. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadeja N, Nalleballe K. Pearls & Oy-sters: Bow hunter syndrome: A rare cause of posterior circulation stroke: Do not look the other way. Neurology. 2018;91:329–331. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esenwa C, Gutierrez J. Secondary stroke prevention: challenges and solutions. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:437–450. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S63791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strickland BA, Pham MH, Bakhsheshian J, Russin JJ, Mack WJ, Acosta FL. Bow Hunter's Syndrome: Surgical Management (Video) and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;103:953.e7–953.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan NR, Elarjani T, Chen SH, Miskolczi L, Strasser S, Morcos JJ. Atlanto-Occipital Decompression of Vertebral Artery for a Variant of Bow Hunter's Syndrome: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2021;21:E363–E364. doi: 10.1093/ons/opab231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schunemann V, Kim J, Dornbos D 3rd, Nimjee SM. C2-C3 Anterior Cervical Arthrodesis in the Treatment of Bow Hunter's Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Giotta Lucifero A, Marasco S, Elsawaf Y, Del Maestro M, Elbabaa SK, Galzio R. Anterolateral approach for subaxial vertebral artery decompression in the treatment of rotational occlusion syndrome: results of a personal series and technical note. Neurol Res. 2021;43:110–125. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2020.1831303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mileva NB, Vassilev DI, Serbezova I, Rigatelli G, Gill RJ. Vertebral Artery Stenting in a Patient With Bow Hunter's Syndrome. JACC Case Rep. 2019;1:73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motiei-Langroudi R, Griessenauer CJ, Alturki A, Adeeb N, Thomas AJ, Ogilvy CS. Bow Hunter's Syndrome from a Tortuous V1 Segment Vertebral Artery Treated with Stent Placement. World Neurosurg. 2017;98:878.e11–878.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darkhabani MZ, Thompson MC, Lazzaro MA, Taqi MA, Zaidat OO. Vertebral artery stenting for the treatment of bow hunter's syndrome: report of 4 cases. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:908.e1–908.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding D, Mehta GU, Medel R, Liu KC. Utility of intraoperative angiography during subaxial foramen transversarium decompression for bow hunter's syndrome. Interv Neuroradiol. 2013;19:240–244. doi: 10.1177/159101991301900215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen HS, Doan N, Eckardt G, Pollock G. Surgical decompression coupled with diagnostic dynamic intraoperative angiography for bow hunter's syndrome. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:147. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.165173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng S, Boetto J, Favier V, Thouvenot E, Costalat V, Lonjon N. Bow Hunter's Syndrome: Surgical Vertebral Artery Decompression Guided by Dynamic Intraoperative Angiography. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Velat GJ, Reavey-Cantwell JF, Ulm AJ, Lewis SB. Intraoperative dynamic angiography to detect resolution of Bow Hunter's syndrome: Technical case report. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:420–3; discussion 423. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]