Abstract

Objective:

Recently there have been calls to strengthen integration of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention messages, spurred by increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. To assess the extent to which public health/clinical messages about unintended pregnancy prevention also address STI prevention, we conducted a content analysis of web-based health promotion information for young people.

Study Design:

Websites identified through a systematic Google search were eligible for inclusion if they were operated by a United States-based organization with a mission related to public health/clinical services and the URL included: 1) original content; 2) about sexual and reproductive health; 3) explicitly for adolescents and/or young adults. Using defined protocols, URLs were screened and content was selected and analyzed thematically.

Results:

Many of the 32 eligible websites presented information about pregnancy and STI prevention separately. Concurrent discussion of the two topics was often limited to statements about (1) strategies that can prevent both outcomes (abstinence, condoms only, condoms plus moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods) and (2) contraceptive methods that confer no STI protection. We also identified framing of condom use with moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods for back-up pregnancy prevention but not STI prevention. STI prevention methods in addition to condoms, such as STI/HIV testing, vaccination, or pre-exposure or post-exposure prophylaxis, were typically not addressed with pregnancy prevention information.

Conclusions:

There may be missed opportunities for promoting STI prevention online in the context of increasing awareness of and access to a full range of contraceptive methods.

Implications:

Strengthening messages that integrate pregnancy and STI prevention may include: describing STI prevention strategies when noting that birth control methods do not prevent STIs; promoting a full complement of STI prevention strategies; and always connecting condom use to STI prevention, even when promoting condoms for back-up contraception.

Keywords: Health promotion, Adolescents, Condoms, STI prevention, Pregnancy prevention

1. Introduction

Integrating unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention has been a long-standing public health challenge. These outcomes have traditionally been addressed through distinct funding streams and vertically-oriented programs in the United States. At the individual-level, the most effective pregnancy prevention methods confer no STI protection, so use of condoms, a fundamental STI prevention strategy, with more effective contraception is recommended for at-risk individuals [1,2]. Despite such complexity, the need for integration remains given the burden of both unintended pregnancy and STIs, particularly among adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 years who account for about half of all annual STIs and unintended pregnancies [3,4].

Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) among adolescents and young adults has renewed attention to the importance of addressing STI prevention and pregnancy prevention together. Recent studies suggest that condom use with LARC methods is low among adolescents—an issue also documented with moderately effective contraceptive methods (e.g., oral contraceptives, birth control patch, shot, or ring) [5,6]. However, adolescent LARC users may be even less likely to use condoms and more likely to have multiple partners compared to moderately effective method users [6]. Such findings have spurred calls for strengthening health education and clinic-based counseling to address both pregnancy and STI prevention [7,8].

National recommendations for quality family planning services emphasize counseling about STI prevention, including condom use, as a routine part of contraceptive care [2]. However, the extent to which public health and clinical messages address both prevention goals simultaneously remains unclear. Empirically assessing current messages is a key first step toward improving them, and online health information for adolescents and young adults provides a practical opportunity for such assessment. Over 60% of adolescents 15–18 years of age have looked up health information on the internet, and about one-quarter (28%) of women aged 15–19 years obtained information about sexual and reproductive health online [9,10]. Moreover, online information has the potential to change health behavior [11].

We conducted a content analysis of web-based health promotion information for young people to assess how public health/clinical messages about pregnancy prevention also address STI prevention. Three questions guided our analysis: (1) To what extent and how are unintended pregnancy and STI prevention discussed simultaneously? (2) How is condom use framed in relation to both pregnancy and STI prevention? (3) What STI prevention strategies are promoted in addition to condoms (e.g., testing, vaccination, pre-exposure prophylaxis)?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample identification

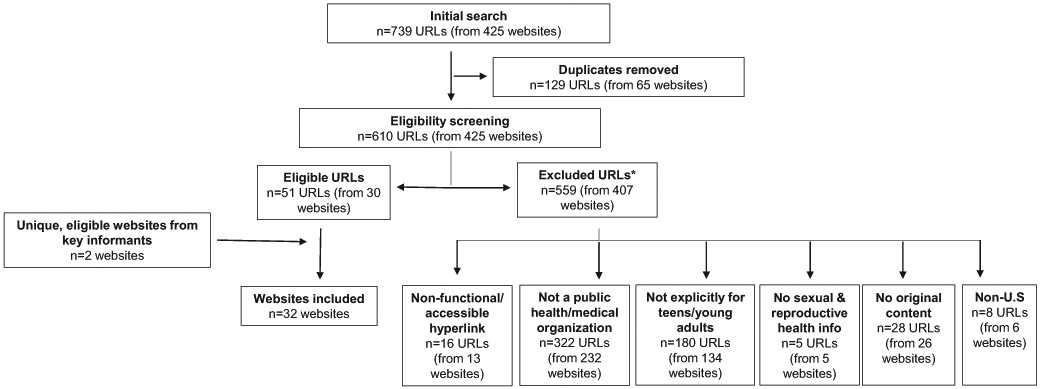

To identify websites, we used systematic procedures adapted from previously published web content analyses [12-14]. Fig. 1 presents the search process. First, we conducted a systematic search using Google, the most popular search engine worldwide [15]. We searched keyword combinations related to adolescents and sexual and reproductive health (Supplementary Material A). We followed procedures to limit personalized results, including turning off location services and using an “incognito” browser. Two coders independently reviewed unique URLs from the first five pages (~50 links) of each keyword search [16,17]. A website was eligible for inclusion if it was operated by an organization in the United States with a mission to promote health and/or provide clinical services and the URL reviewed included: 1) original content; 2) about sexual and reproductive health; 3) explicitly for adolescents and/or young adults (Supplementary Material B). Four adolescent sexual and reproductive health experts reviewed the list of included websites and suggested additional websites, which we added if the sites met the above criteria.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for systematically identifying a sample of websites.

*URLs were excluded by applying eligibility criteria hierarchically (ordered from left to right in the flow diagram).

2.2. Content selection and management

We selected sexual and reproductive health content for young people using defined protocols, excluding videos, clinic locator information, birth control reminders, blogs, quizzes and non-English-language content. For websites that addressed broader health topics and/or audiences, we only selected sexual and reproductive health for young people either from (1) defined sub-sections about “sexual health” or “sexual and reproductive health” and/or “for teens” or (2) by reviewing the entire website to identify information for young people about pregnancy, STIs, sexual development, sexuality, or relationships. For the latter approach, a second author verified content selection. We created PDFs of selected content from each website using PDFmyURL.com. PDFs ranged from six to 3094 pages (Median=120 pages).

2.3. Coding and analysis

We uploaded PDFs to MAXQDA version 12.3 (VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany) for coding and qualitative analysis. Images were not coded. We developed a preliminary codebook with deductive codes based on the research questions (e.g., birth control, condoms, abstinence), and two coders independently reviewed a subset of websites (n=6) to identify inductive codes and refine the codebook. These same coders double coded another eight websites (25%) to ensure consistent application of codes. Intercoder reliability, determined by percentage agreement, was 89%. One author coded the remaining websites and analyzed content thematically, confirming findings with the second coder [18].

3. Results

3.1. Website characteristics

We identified 32 eligible websites operated by a variety of public health/medical organizations, including non-profit advocacy/education organizations (n=14), health clinics/systems (n=10), government health agencies (n=3), academic institutions (n=2), professional medical organizations (n=2) and a for-profit company (n=1). Table 1 provides information about each website. Over half (53%, n=17) focused specifically on sexual and reproductive health. The majority (59%, n=19) provided content primarily for adolescents and young adults, whereas some websites also addressed a broader audience.

Table 1.

Website characteristicsa

| Website | Operated by | Organization description | Primary audience | Scope of content | Type of content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| http://annexteenclinic.org/ | Annex Clinic | Local medical provider | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://kidshealth.org/ | Nemours | Non-profit pediatric health system | Kids, teens, and parents | Multiple health topics, including a defined sub-section on sexual health | Informational web pages |

| http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ | LA County Department of Public Health | Local health department | Health professionals and health consumers, including youth in foster care | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://stayteen.org/ | Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) | National non-profit organization | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| http://teen411.com/home | Valley Community Clinic | Local medical provider | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://teenclinic.org/ | Boulder Family Women's Health Center | Local medical provider | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| http://utteenhealth.org/ | University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio | Local medical center | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.acog.org/ | The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | National professional medical organization | Providers and patients, including teens specifically | Sexual and reproductive health | FAQs |

| http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/ | Advocates for Youth | National non-profit organization | Public health practitioners, parents, teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.ashasexualhealth.org/ | American Sexual Health Association | National non-profit organization that promotes sexual health through advocacy and education | Health consumers | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.emedicinehealth.com/script/main/hp.asp | WebMD | Health consumer website | Health consumers, including teens specifically | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.goaskalice.columbia.edu/ | Columbia University | Academic institution | Health consumers, including adolescents and young adults | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.helpnothassle.org/ | The Youth Project | Local non-profit organization | Teens | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.iwannaknow.org/ | American Sexual Health Association | National non-profit organization that promotes sexual health through advocacy and education | Teens and young adults | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages Ask the Experts |

| http://www.nysyouth.net/ | ACT Youth Network ACT for Youth Center of Excellence |

Technical assistance provider on positive youth development | Teens | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.pamf.org/ | Palo Alto Medical Foundation for Health Care, Research and Education (PAMF) | Local non-profit health care organization | Patients, including teens specifically | Multiple health topics, including a defined subsection on sexual health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.positive.org/Home/index.html | Coalition for Positive Sexuality | Non-profit advocacy and sex education organization | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.safeteens.org/ | Maternal and Family Health Services, Inc. | Non-profit health and human services organization | Teens | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.scarleteen.com/ | Scarleteen | Independent, grassroots sexuality and relationships education and support organization and website | Teens and young adults | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://www.summitmedicalgroup.com/ | Summit Medical Group | Physician-owned multispecialty practice | Patients and caregivers, including teens specifically | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| http://www.teenhealthrights.org/ | National Center for Youth Law | Non-profit legal organization | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health, with a focus on pregnancy and parenting | Informational web pages |

| http://www.teensource.org/ | Essential Access Health | Administrator of California's Title X federal family planning program | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| http://youngmenshealthsite.org/ | Boston Children's Hospital | Local medical center | Teen boys and young men | Multiple health topics, including a defined sub-section on sexual health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| http://youngwomenshealth.org/ | Boston Children's Hospital | Local medical center | Teen girls and young women | Multiple health topics, including a defined sub-section on sexual health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| https://healthychildren.org/ | American Academy of Pediatrics | National professional medical organization | Parents | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| https://sexetc.org/ | Answer | National sexuality education organization | Teens | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| https://sites.google.com/site/mchdyouthsexualhealth/ | Mesa County Public Health Clinic | Local medical provider | Youth | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages |

| https://www.bedsider.org/ | Power to Decide (Formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) | National non-profit organization | Women 18–29 years old | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| https://www.fairview.org/ | Fairview Health Services | Local medical provider | Patients, including teens specifically | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| https://www.girlshealth.gov/ | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Women's Health | Federal government | Teen girls | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

| https://www.plannedparenthood.org/ | Planned Parenthood Federation of America | National sexual and reproductive health care advocate and provider | Health consumers, including teens specifically | Sexual and reproductive health | Informational web pages Q&A |

| https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/index.page | New York City Department of Health | Local health department | Health consumers, including teens specifically | Multiple health topics | Informational web pages |

Website content was downloaded April–July 2017.

3.2. To what extent and how are unintended pregnancy and STI prevention discussed simultaneously?

Websites generally presented pregnancy and STI prevention information separately. In fact, 14 websites (44%) were organized, in part, by separate sections about types of birth control and STIs. Within this structure, concurrent discussion of the two topics was often limited to discrete statements (1) outlining strategies that can simultaneously prevent both outcomes and (2) emphasizing that certain contraceptive methods confer no STI protection. This information was most often found with birth control content.

3.2.1. Strategies to prevent both unintended pregnancy and STIs

Twenty-nine (91%) websites promoted strategies to simultaneously prevent both pregnancy and STIs (Table 2). Strategies typically included abstinence, condoms only, and condoms with moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods. Across the 29 websites that promoted such strategies, there were more than 400 discrete statements. Many websites promoted both single and multiple method approaches to reducing both risks. Occasionally, it was unclear whether condom use was recommended in addition to another contraceptive method or as a single method, for example: “Depo-Provera® injections do not protect against sexually transmitted infections. So you need to use a condom […]”.

Table 2.

Examples from reviewed websites of messages about how to simultaneously prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs

| Abstinence only |

|

| Condoms only |

Framing Condoms as Contraception

|

| methods | |

| Condoms plus a moderately or highly effective method of contraception |

Promoting Condoms for Both STI and Pregnancy Prevention

Framing Condoms as Contraception

|

This is the only message in this list of examples that explicitly states that condoms should be used with contraception specifically for STI prevention.

3.2.2. Most contraceptive methods do not prevent STIs

Websites commonly mentioned that certain contraceptive methods do not prevent STIs, sometimes describing this as a disadvantage of the method. However, only about half of such statements also included information about STI prevention strategies; this was done somewhat inconsistently within websites with sub-sections for types of birth control. For example, one website promoted condom use in conjunction with oral contraceptives but did not do so for other types of hormonal birth control, including IUDs and implants. Moreover, a statement about withdrawal conferring no STI protection suggested using another method, “like the IUD, implant, ring, patch, shot, or pill if you’re using withdrawal as your primary method” but none of these suggested methods prevent STIs.

3.3. How is condom use framed in relation to pregnancy and STI prevention?

Thirty-one (97%) websites addressed condom use. Websites with sections about birth control included male and female condoms as contraception, in which case effectiveness was usually described in relation to pregnancy prevention only; STI prevention was often noted as an added benefit of the method. Information about types of STIs generally included condoms as a prevention strategy. Distinct descriptions of condom use in relation to each prevention goal further illustrate how typical website structure—separate sections for birth control and STIs—may limit integrated messaging. Additionally, common messages about condom use with moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods (1) for back-up pregnancy prevention and/or (2) without explicit reference to STI prevention may also undermine integration.

3.3.1. Condom use framed as back-up pregnancy prevention

Half of websites (n=16) included statements promoting condom use with moderately or highly effective methods in terms of back-up pregnancy prevention only (Box 1). Emphasizing condom use with another method for back-up pregnancy prevention has the potential to discourage condom use with methods that are highly effective. According to one website: “[…] especially where user error is a non-issue, like with an IUD or an implant – the difference [in effectiveness] is so slight that backing up is just overkill.” A majority of recommendations for temporary use of back-up contraception after starting a method or when taking medications that could decrease contraceptive effectiveness cited condoms as an example. Statements encouraging consistent condom use for STI prevention accompanied this information in just a few cases, which actually created conflicting messages about the recommended length and purpose of using condoms with more effective contraceptive methods.

Box 1. Examples from reviewed websites of promoting condoms with moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods for pregnancy prevention only.

|

3.3.2. Unclear framing of condoms with more effective methods for STI prevention

Information intended to promote condoms with more effective methods for STI prevention may not clearly emphasize this prevention goal. Of the 26 websites with such statements, 10 (38%) had at least one that encouraged condom use with contraception for additional protection against pregnancy as well as STI prevention (Table 2). Such framing along with (1) the promotion of condoms with moderately effective methods for back-up contraception described above; and (2) descriptions of condoms for STI prevention as contraception (e.g., “latex or polyurethane condoms are the only method of birth control that can protect against the HIV virus and AIDS” [italics added]) may overly emphasize condom use for pregnancy prevention. Moreover, most websites had information about condoms with more effective methods that failed to promote condom use directly in relation to STI prevention, even though implied. For example, the statement “Combining condoms with hormonal birth control—such as the pill, ring, or shot—is a very effective way to prevent against both pregnancy and STDs” does not explicitly state that condoms are recommended specifically for preventing STIs.

3.4. What STI prevention strategies are promoted in addition to condoms?

Twenty-six websites (81%) mentioned STI prevention options in addition to condoms, although HIV prevention strategies were limited (Box 2). However, these strategies were often not addressed in combination with contraceptive information.

Box 2. STI prevention strategies promoted within reviewed websites.

| • Condoms | • Partner communication |

| • Abstinence | • Pre-exposure prophylaxis |

| • Dental dams | • Post-exposure prophylaxis |

| • STI/HIV testing | • Avoiding alcohol |

| • HBV vaccination | • Avoiding injecting drugs |

| • HPV vaccination | • Washing hands and sex toys |

| • Mutual monogamy | • Avoiding sharing personal care items |

| • Treatment* | • Masturbation |

| • Testing and treatment of partners | • Outercourse |

| • Minimizing number of partners | • Circumcision |

Specifically for genital herpes, scabies, HIV, and perinatal HBV.

3.4.1. A variety of STI prevention strategies were frequently promoted except for biomedical HIV prevention

Thirty websites (94%) addressed STI/HIV testing, although they did not typically frame testing as a prevention option. Content about hepatitis B (HBV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) generally included vaccination as a prevention strategy. In contrast, only five websites (16%) explicitly mentioned pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and just two (6%) described treatment as HIV prevention.

3.4.2. Few STI prevention strategies beyond condoms were promoted with contraceptive methods

Notably, information simultaneously addressing pregnancy and STI prevention generally did not address the range of STI prevention strategies reflected in Box 2. In a few cases, STI/HIV testing was promoted with contraceptive methods, typically as an alternative to condoms even though testing and mutual monogamy may not always be a realistic strategy for young people. Moreover, one website encouraged testing without emphasizing mutual monogamy and another described a complex testing-based strategy that might be difficult for young people to understand and implement: “six months of safer sex, six months of sexual monogamy, and then TWO full STI screenings for each partner—once at the start of that six months, once at the end—before ditching latex barriers.” Information about emergency contraception (EC), particularly in the context of condom errors, offers a logical opportunity for promoting STI testing with contraception, yet this was not done routinely. Relatedly, only two websites mentioned PEP in conjunction with EC.

4. Discussion

To inform specific recommendations for strengthening public health and clinical messages intended to address both pregnancy and STI prevention, we conducted a systematic assessment of online web content about sexual and reproductive health for adolescents and young adults. We found that many sites are organized by separate sections about birth control and STIs, which may hinder integration of pregnancy and STI prevention content. Pregnancy and STI prevention were primarily addressed through discrete messages about how to prevent both outcomes. It is promising that such statements were prevalent. However, we also identified notable limitations aligning with conceptual concerns previously raised [8], including missed opportunities, inconsistent messaging, and potentially problematic framing.

Perhaps the most obvious missed opportunity is the frequent absence of information about how to prevent STIs when noting that certain contraceptive methods confer no STI protection. This would be straightforward to address by consistently providing information about STI prevention methods, ideally including a range of options. Although websites promoted many STI prevention approaches, a comprehensive set of strategies was not typically included with information about pregnancy prevention. In particular, we noted a lack of information about STI testing and PEP when promoting EC in the context of condom failure. Additionally, absence of information about PrEP and treatment as prevention when discussing HIV prevention emerged as another missed opportunity. Perhaps this gap reflects the fact that these strategies are more recent prevention options, and in the case of PrEP, may be less available for adolescents. Going forward, addressing biomedical HIV prevention will help ensure that online information for young people reflects scientific advances in prevention technology.

Different strategies for simultaneous prevention of unplanned pregnancy and STIs were often promoted within a single website, including abstinence, condoms only, and condoms plus moderately or highly effective contraceptive methods. Offering a full range of prevention options is consistent with contraceptive counseling guidelines [2], and there is no single, ideal approach [19,20]. However, multiple different types of messages may make it difficult for youth to select and implement the best approach for their unique circumstances. Communication materials may benefit from a more in-depth discussion of ways to prevent both outcomes, including benefits and limitations of different strategies and a comprehensive menu of options.

Finally, framing condom use with highly or moderately effective contraceptive methods in terms of contraception and back-up pregnancy prevention, combined with the absence of explicit statements about condom use for STI prevention, could be problematic. Studies suggest that pregnancy prevention is the primary motivator for condom use, even when using a moderately or highly effective method of contraception [21,22]. Although messages about condoms as contraception or back-up contraception may resonate with young people, promoting condom use with more effective contraceptive methods directly in relation to STI prevention will help emphasize the importance of this prevention goal. Doing so may involve developing clear, succinct messages that address the efficacy of condoms for STI prevention, which is inherently more complex to describe given differences across types of STIs.

This study has limitations. For one, although our methods were systematic, our search strategy yielded a sample of health promotion messages. To keep the review manageable, we did not use exhaustive search procedures, and we excluded certain types of content. It is also possible that our content selection process, although standardized, did not capture all relevant content on included websites. Additionally, given our interest in public health and clinical messages we conducted a controlled search using keywords rather than mimicking adolescent search behavior, which generally involves searching questions or phrases [23]. The content analyzed in this study may, therefore, not be the content adolescents frequently view, which includes websites such as Wikipedia that were not eligible for inclusion in our study [23]. Relatedly, we did not analyze video content which is a format commonly accessed by youth [24]. In general, we cannot draw conclusions about the impact of the web content analyzed on adolescent behavior; we do not know how many adolescents typically view this content nor how they interpret it.

Future research could assess broader content and formats as well as information from other sources of health education including sexual health education curricula, providers, and parents. To that end, analysis of content for parents and providers might indicate whether these audiences are receiving integrated information to share with young people. Another important next step is to assess how current and potential messages about pregnancy and STI prevention influence adolescents' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. We know framing of health messages is important in this regard [25], yet empirical testing could inform appropriate changes to health promotion content that ensure comprehensiveness and saliency while minimizing information overload [26].

In particular, future research should explore how to structure online information to facilitate integration of pregnancy and STI prevention information. Frameworks aligned with the concept of sexual health may offer a useful strategy for doing so [8,27,28]. For example, organizing content according to aspects of a healthy relationship, such as decisionmaking about sexual activity and conversations with partners about pregnancy and STI prevention, may be one approach that also better resonates with young people. At minimum, adding website sections about simultaneously addressing unintended pregnancy and STI prevention would allow for a more comprehensive presentation of prevention strategies while also raising the visibility of this issue. Such structural changes in combination with improving discrete messages incorporated throughout websites offer opportunities to strengthen integration of online pregnancy and STI prevention information for adolescents and young adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eric Buhi, Ty Collins, and Rachel Kachur for thoughtful discussions and assistance on the search strategy, and Melissa Kottke, Deb Levine, Maria Trent, and Fred Wyand for providing input on the included websites. We also appreciate Retze Faber with PDFmyURL.com for providing technical assistance on data management and Jaimie Shing for her research assistant support.

Funding

This work was supported by Emory University Professional Development Support Funds and Letz Funds from the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2018.04.011.

References

- [1].Bearinger LH, Resnick MD. Dual method use in adolescents: a review and framework for research on use of STD and pregnancy protection. J Adolesc Health 2003;32: 340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, Curtis K, Glass E, Godfrey E. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Williams RL, Fortenberry JD. Dual use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and condoms among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:S29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Steiner RJ, Liddon N, Swartzendruber AL, Rasberry CN, Sales JM. Long-Acting reversible contraception and condom use among female US high school students: Implications for sexually transmitted infection prevention.JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:428–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Potter J, Soren K. Long-Acting reversible contraception and condom use: We need a better message. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:417–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Steiner RJ, Liddon N, Swartzendruber AL, Pazol K, Sales JM. Moving the message beyond the methods: Toward integration of unintended pregnancy and STI/HIV prevention. Am J Prev Med 2018;54:440–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kaiser Family Foundation. Sexual Health of Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/sexual-health-of-adolescents-and-young-adults-in-the-united-states/; 2014, Accessed date: 21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Menlo Park, CA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Korda H, Itani Z. Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract 2013;14:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Marques SS, Lin JS, Starling MS, Daquiz AG, Goldfarb ES, Garcia KC. Sexuality education websites for adolescents: A framework-based content analysis. J Health Commun 2015;20:1310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Borzekowski DL, Schenk S, Wilson JL, Peebles R. e-Ana and e-Mia: A content analysis of pro-eating disorder Web sites. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Harris K, Byrd K, Engel M, Weeks K, Ahlers-Schmidt CR Internet-based information on long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents. J Prim Care Community Health 2016;7:76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Search Engine Land. Google still world's most popular search engine by far, but share of unique searchers dips slightly. https://searchengineland.com/google-worlds-most-popular-search-engine-148089; 2013, Accessed date: 21 December 2017.

- [16].Rahnavardi M, Arabi MS, Ardalan G, Zamani N, Jahanbin M, Sohani F. Accuracy and coverage of reproductive health information on the Internet accessed in English and Persian from Iran.J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2008;34:153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Minzer-Conzetti K, Garzon MC, Haggstrom AN, Horii KA, Mancini AJ, Morel KD. Information about infantile hemangiomas on the Internet: how accurate is it? J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].O'Leary A Are dual-method messages undermining STI/HIV prevention? Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:691210 7 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cates W Jr, Steiner MJ. Dual protection against unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections: what is the best contraceptive approach? Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Powers AM. Motivations for condom use: do pregnancy prevention goals undermine disease prevention among heterosexual young adults? Health Psychol 1999;18:464–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lemoine J, Teal SB, Peters M, Guiahi M. Motivating factors for dual-method contraceptive use among adolescents and young women: a qualitative investigation. Contraception 2017;96:352–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Buhi ER, Daley EM, Fuhrmann HJ, Smith SA. An observational study of how young people search for online sexual health information. J Am Coll Health 2009;58: 101–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boyar R, Levine D, Zensius N. TECHsex USA: youth sexuality and reproductive health in the digital age. Oakland, CA: ISIS, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med 2012;43:101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pew Research Center. Information Overload. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/12/07/information-overload/, Accessed date: 13 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Swartzendruber A, Zenilman JM. A national strategy to improve sexual health. JAMA 2010;304:1005–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tharp AT, Carter M, Fasula AM, Hatfield-Timajchy K,Jayne PE, Latzman NE. Advancing adolescent sexual and reproductive health by promoting healthy relationships. J Womens Health 2013;22:911–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.