Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To quantify adolescent- and parent-perceived importance of provider-adolescent discussions about sexual and reproductive health (SRH), describe prevalence of provider confidentiality practices and provider-adolescent discussions about SRH topics during preventive visits, and identify missed opportunities for such conversations.

METHODS:

We used data from a national Internet survey of 11- to 17-year-old adolescents and their parents. Data were weighted to represent the noninstitutionalized US adolescent population. Adolescents who had a preventive visit in the past 2 years and their parents reported on perceived importance of provider-adolescent discussions about SRH topics: puberty, safe dating, gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual decision-making, sexually transmitted infections and HIV, methods of birth control, and where to get SRH services. Adolescents and parents reported whether they had ever discussed confidentiality with the adolescent’s provider. Adolescents reported experiences at their most recent preventive visit, including whether a provider spoke about specific SRH topics and whether they had time alone with a provider.

RESULTS:

A majority of adolescents and parents deemed provider-adolescent discussions about puberty, sexually transmitted infections and HIV, and birth control as important. However, fewer than one-third of adolescents reported discussions about SRH topics other than puberty at their most recent preventive visit. These discussions were particularly uncommon among younger adolescents. Within age groups, discussions about several topics varied by sex.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although most parents and adolescents value provider-adolescent discussions of selected SRH topics, these discussions do not occur routinely during preventive visits. Preventive visits represent a missed opportunity for adolescents to receive screening, education, and guidance related to SRH.

Adolescent preventive visits present important opportunities for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) promotion and disease prevention. In primary care settings, quality adolescent SRH services include education about confidentiality, provision of time alone for adolescents with their health care providers, developmentally appropriate screening for sexual risk and counseling about preventive behaviors, and provision of appropriate biomedical SRH services.1–7 Educating adolescents and parents about confidentiality and ensuring time alone between adolescents and their providers may facilitate communication about sensitive topics related to SRH.2 However, research indicates that many US adolescents have never had a private discussion with their provider.8,9

Confidential discussions with providers can play an important role in addressing adolescents’ SRH needs, including preventing unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2 Although teen-aged pregnancy rates have declined substantially, each year, ~456 000 women <20 become pregnant, and US rates remain among the highest in the industrialized world.10 US youth aged 15 to 24 account for nearly half of the 26 million new STIs each year.11 Ideally, SRH discussions occur within the context of risk screening, education, anticipatory guidance, and referral and address topics including puberty, sexual orientation, sexual identity, sexual intercourse, pregnancy and STI prevention, communication with partners, and healthy versus unhealthy relationships.5,12,13 There has been little population-based research examining adolescent-reported SRH discussions with providers in primary care settings, particularly with adolescents aged 14 and younger.14 National monitoring surveys, such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the National Health Interview Survey,15 and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, do not collect data on provider-adolescent SRH discussions. Findings from a 2016 population-based survey indicate that fewer than one-third of 13- to 18-year-olds reported discussing STIs and HIV, birth control, or sexual orientation at their last health care visit.16 Clinic-based studies suggest that SRH discussions may be less common with younger adolescents and with boys versus girls.13,17 Little is known about adolescent and parent preferences for SRH topics for providers to address. Efforts to improve the quality of SRH services would benefit from a clearer understanding of topics routinely covered in provider-adolescent discussions about SRH as well as parent and adolescent preferences regarding SRH topics to address.

Using data from a nationally representative sample of 11- to 17-year-old adolescents and their parents, we describe adolescent and parent preferences for discussing specific SRH topics with primary care providers. We broaden the scope of SRH discussion topics that are typically assessed (eg, STIs and HIV, birth control methods) to include developmentally important topics during adolescence (eg, puberty, safe dating, sexual orientation, gender identity) and elements of quality SRH services on the basis of recent research,1,8,16 including provider-adolescent and provider-parent discussions about confidentiality, time alone between adolescents and providers, face-to-face screening about sexual activity, and provider-adolescent discussions about specific SRH topics during a most recent preventive visit. Finally, we examine gaps between adolescent- and parent-expressed importance of provider-adolescent discussions about SRH topics and adolescent experience during a most recent preventive visit. With each of these descriptions, we consider differences between younger and older adolescents and, within age groups, differences by sex.

METHODS

Data Source and Sample

This study was a part of the multimethod Confidential Adolescent Sexual Health Services study. In June 2019, we conducted an Internet survey with national sample of 11- to 17-year-old adolescents and their parents. Parents were existing members of an online national panel (KnowledgePanel, maintained by the research firm Ipsos)18 that uses dual-frame sampling (list-assisted, random-digit dialing and address-based sampling) to obtain a probability-based sample of US households. This methodology improves population coverage, especially for hard-to-reach individuals, because it samples households regardless of phone or Internet status. Parents received standard KnowledgePanel incentives18 for completing the Confidential Adolescent Sexual Health Services survey (equivalent to $5 US dollars). The University of Minnesota and Columbia University Institutional Review Boards approved the study.

The research firm sent e-mail invitations to 2495 KnowledgePanel members, of whom 1234 completed an eligibility screener (49.5%). Panel members were eligible if they were the parent or guardian of a child aged 11 to 17 years old and could read English or Spanish. We asked eligible parents to allow their children aged 11 to 17 years old to participate. Parents with multiple children aged 11 to 17 years old were asked questions about their child with the most recent birthday, and this child became eligible for participation. Parents provided consent for themselves and this child before the start of parent surveys. Adolescents provided assent before their surveys. The final sample consisted of 1005 parent-adolescent dyads, a response rate of 61.4% calculated by using American Association for Public Opinion Research formula 4,19 assuming 50% of panelists who did not respond to the survey invitation were eligible. The sample was weighted to represent the noninstitutionalized US adolescent population by age, sex, race and/or ethnicity, census region, metropolitan status, household income and language proficiency. Data for the present analysis come from parent-adolescent dyads in which the adolescent had a preventive visit in the last 2 years (n = 853 dyads; 84.8% of respondents). We used a 2-year window to align with a recent population-based survey of youth regarding clinical preventive services.16

Measures

We developed survey items on the basis of the literature, existing care guidelines, and our previous research.2,5,8,16 Because many items had not been used with younger adolescents, we cognitively tested items with a racially diverse group of 11- to 14-year-olds (n = 7) to ensure they were able to answer survey questions as intended.20 After refining survey questions, we pretested survey instruments (n = 27 parent-adolescent dyads) before data collection.

Importance of SRH Discussions

Parent and adolescent surveys assessed perceived importance of health care providers talking with adolescents about specific SRH topics during a preventive visit, including: (1) puberty, (2) safe dating, (3) gender identity, (4) sexual orientation, (5) sexual decision-making, (6) STIs and HIV, (7) methods of birth control, and (8) where to get SRH services. Items used a 4-point response ranging from “not at all important” to “very important.” We categorized those who endorsed a topic as either “very important” or “moderately important” as perceiving the topic was important.

Experience With Elements of Quality SRH Services

Parallel items on parent and adolescent surveys assessed whether a provider had ever discussed confidentiality of adolescent services with them. The adolescent survey asked questions about adolescents’ experiences at their most recent preventive visit, including whether the adolescent had time alone with a provider, whether the provider asked if the adolescent had ever had sex, and whether the provider had talked with the adolescent about each of the SRH topics described above.

Missed Opportunities for SRH Discussions

We constructed a measure of missed opportunity for SRH discussions at adolescents’ most recent preventive visit, defined as the percentage of adolescents who thought it was important that a provider talk with them about a particular topic but did not discuss that topic at their most recent preventive visit. We constructed a similar measure for parents, namely the percentage of parents who thought it important that providers talk with their adolescent about a particular topic but whose child reported that they did not discuss that topic at their most recent preventive visit.

Demographic Characteristics

Information on demographic characteristics was reported by adolescents (sex, age, race and/or ethnicity, sexual orientation) and parents (sex, age, relationship to adolescent, marital status). The research firm provided information on respondents’ area of residence (metropolitan versus nonmetropolitan) and household income.

Data Analysis

We described respondents’ perceived importance and experience with discussing SRH topics with providers. We used χ2 tests to compare perceived importance and experience between 11- to 14-year-olds (younger adolescents) and 15- to 17-year-olds (older adolescents). Within age groups, we used χ2 tests to evaluate differences between boys and girls. Analyses were conducted by using Stata version 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and weighted to yield nationally representative estimates.

RESULTS

Our sample (Table 1) included youth who self-identified as non-Hispanic white (54%), non-Hispanic Black (15%), Hispanic (24%), and other racial groups (7%). Approximately half (49%) were female, 91% identified as heterosexual, and 17% lived in nonmetropolitan areas. Just more than half (54%) of parents identified as the mother or stepmother of the adolescent respondent, and approximately half (53%) were ages 40 to 50 years. Most parents (88%) were married or living with a partner. Annual household income varied from <$25 000 (12%) to >$125 000 (28%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Adolescent and Parent Participants

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Adolescents | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 418 (48.9) |

| Male | 427 (51.0) |

| Other | 2 (0.1) |

| Age, y | |

| 11–14 | 465 (56.1) |

| 15–17 | 388 (43.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 511 (54.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 94 (15.1) |

| Other and/or multiple races | 48 (6.6) |

| Hispanic | 200 (24.2) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 762 (90.7) |

| Bisexual, gay, lesbian, or other | 39 (4.6) |

| Not sure | 40 (4.7) |

| Residence | |

| Metropolitan | 569 (82.8) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 284 (17.2) |

| Parents | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 521 (53.8) |

| Male | 332 (46.2) |

| Age, y | |

| Younger than 40 | 224 (27.9) |

| 40–45 | 262 (31.3) |

| 46–50 | 183 (21.3) |

| Older than 50 | 183 (19.5) |

| Relationship to adolescent participant | |

| Mother or stepmother | 520 (53.6) |

| Father or stepfather | 330 (46.2) |

| Other | 2 (0.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 707 (83.5) |

| Living with partner | 33 (4.2) |

| Single (widowed, separated, divorced, never married) | 113 (12.3) |

| Household income, $ | |

| <25 000 | 101 (12.4) |

| 25 000–49 999 | 155 (18.0) |

| 50 000–74 999 | 150 (16.2) |

| 75 000–99 999 | 134 (13.9) |

| 100 000–124 999 | 113 (11.3) |

| 125 000+ | 200 (28.2) |

Data are raw frequencies and weighted percentages.

Importance of Discussing SRH Topics With Health Care Providers

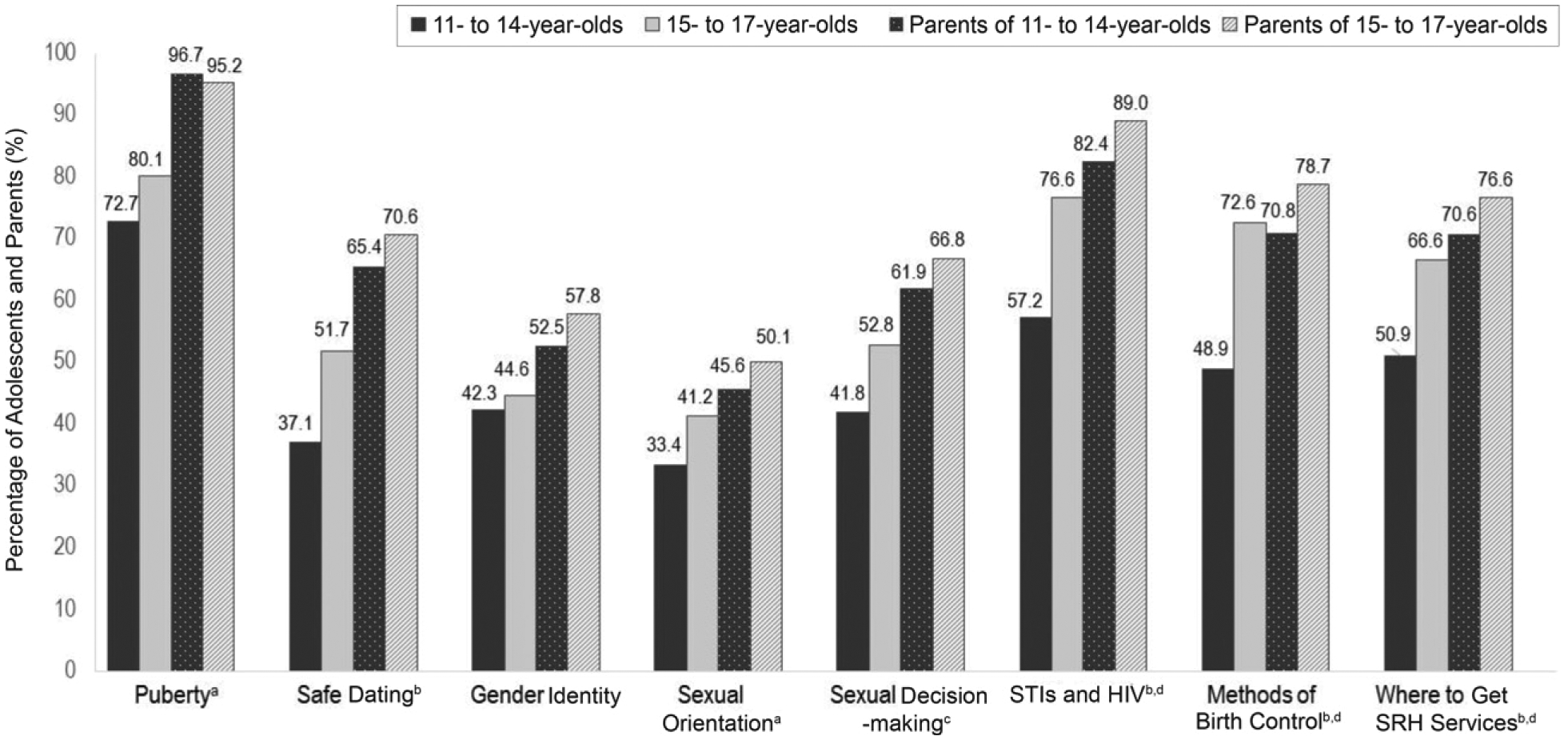

Figure 1 depicts adolescent- and parent-reported importance of provider-adolescent discussions about SRH topics. Among adolescents, topics most frequently endorsed as important included puberty, STIs and HIV, methods of birth control, and where to get SRH services. A greater percentage of older adolescents than younger adolescents reported that each topic was important. Within age groups, similar percentages of boys and girls noted the importance of discussing most topics, although some sex differences existed. Among younger adolescents, a greater percentage of girls noted the importance of discussions about puberty (80.5% of girls versus 67.2% of boys; P = .007). Among older adolescents, a greater percentage of girls noted the importance of discussions about STIs and HIV (84.8% of girls versus 73.0% of boys; P = .02) and methods of birth control (80.9% of girls versus 68.4% of boys; P = .02).

FIGURE 1.

Adolescent- and parent-reported importance of provider-adolescent discussions about SRH topics. The figure depicts percentages of adolescents and parents endorsing each topic, by age. Footnotes indicate statistical significance for comparisons based on χ2 analyses. a Adolescent differences by age, P <.05. b Adolescent differences by age, P <.001.c Adolescent differences by age, P <.01. d Parent differences by age of adolescent, P <.05.

More parents than adolescents reported the importance of providers discussing all topics with their adolescents. Among parents, the topics most frequently endorsed as important included puberty, STIs and HIV, methods of birth control, and where to get SRH services. Figure 1 depicts significant differences between parents of younger adolescents and parents of older adolescents. Within age groups, similar percentages of parents of boys and parents of girls noted the importance of discussing all topics.

Experience With Elements of Quality SRH Services

When we examined experience with elements of quality SRH services, 24.0% of younger adolescents and 42.3% of older adolescents (P < .001) reporting ever having a provider speak with them about confidentiality (Table 2). Approximately 31.2% of parents of younger adolescents and 35.7% of parents of older adolescents (P = .24) reported ever having a provider speak with them about confidentiality of adolescent services (Table 2). When we examined a specific confidentiality practice, 20.0% of younger adolescents and 44.1% of older adolescents (P < .001) reported having time alone with a provider at their most recent preventive visit (Table 2). For each indicator, there were no sex differences within adolescent age groups.

TABLE 2.

Respondent Experiences With Elements of Quality SRH Services, by Adolescent Age Group

| % Affirmative Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 11–14-year-olds (n = 465) | 15–17-year-olds (n = 388) | Differences by Age Group, Pa | |

| Provider ever discussed confidentiality with adolescent | 24.0 | 42.3 | <.001 |

| Provider ever discussed confidentiality of adolescent services with parent | 31.2 | 35.7 | .24 |

| Adolescent’s most recent preventive visit | |||

| Adolescent had time alone with provider | 20.0 | 42.3 | <.001 |

| Provider asked whether teenager had had sex | 14.0 | 38.7 | <.001 |

| Topics provider discussed | |||

| Puberty | 46.3 | 53.9 | .06 |

| Safe dating | 10.5 | 23.5 | <.001 |

| Gender identity | 8.3 | 19.5 | <.001 |

| Sexual orientation | 9.7 | 16.4 | .02 |

| Sexual decision-making | 12.6 | 22.3 | .003 |

| STIs and HIV | 15.1 | 31.4 | <.001 |

| Methods of birth control | 10.3 | 27.5 | <.001 |

| Where to get SRH services | 9.4 | 21.3 | <.001 |

Differences between adolescent age groups were tested by using χ2 tests.

At their most recent preventive visit, 14.0% of younger adolescents and 38.7% of older adolescents (P < .001) reported that providers asked about their sexual activity (Table 2). Within age groups, 19.4% of younger girls, versus 9.0% of younger boys (P = .01), noted that providers asked about their sexual activity. Of potential SRH topics, provider-adolescent discussions about puberty were most common (Table 2). Fewer than one-third of adolescents reported a provider discussing any other SRH topic. With the exception of puberty, significantly greater percentages of older adolescents than younger adolescents reported discussing these topics (Table 2). Within age groups, 2 differences based on sex were observed. Among younger adolescents, a greater percentage of girls reported that providers discussed puberty (52.7% of girls versus 40.0% of boys; P = .02). Among older adolescents, a greater percentage of girls reported that providers discussed methods of birth control (37.3% of girls versus 18.1% of boys; P < .001).

Missed Opportunities for SRH Discussions

Table 3 presents gaps between perceived importance of discussing SRH topics and actual discussions at the adolescent’s most recent preventive visit. Among adolescents, gaps varied in magnitude by topic and age, ranging from 40.0% of older adolescents who thought puberty was important but did not discuss this topic to 85.6% of younger adolescents who thought sexual orientation was important but did not discuss this topic. Gaps between importance and actual discussions were significantly greater among younger versus older adolescents on 6 of 8 topics assessed. Within age groups, gaps were similar for boys and girls, with the exception of discussion about methods of birth control, for which older boys had a significantly greater gap (77.5% of older boys versus 56.9% of older girls; P = .004).

TABLE 3.

Gaps Between Perceived Importance and Discussions About SRH Topics at Most Recent Preventive Visit, by Adolescent Age Group

| Of Those Who Perceived a Topic to Be Important, % of Teenagers Who Did Not Discuss With Provider | Adolescents, % | Differences by Age Group, Pa | Parents, % | Differences by Age Group, Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11–14-year-olds | 15–17-year-olds | 11–14-year-olds | 15–17-year-olds | |||

| Puberty | 45.5 | 40.0 | .23 | 53.1 | 44.7 | .04 |

| Safe dating | 78.8 | 63.8 | .01 | 85.5 | 70.0 | <.001 |

| Gender identity | 85.1 | 67.6 | .002 | 86.7 | 71.9 | .003 |

| Sexual orientation | 85.6 | 70.5 | .01 | 82.9 | 73.1 | .06 |

| Sexual decision-making | 76.7 | 66.3 | .06 | 81.3 | 70.7 | .021 |

| STIs and HIV | 78.6 | 63.7 | .002 | 82.5 | 65.6 | <.001 |

| Methods of birth control | 84.0 | 66.3 | <.001 | 86.3 | 66.1 | <.001 |

| Where to get SRH services | 84.3 | 75.3 | .05 | 87.2 | 74.0 | .001 |

Differences between age groups were tested by using χ2 tests.

Likewise, substantial gaps in provider-adolescent discussions existed on the basis of parent perceptions (Table 3). The percentage of parents who perceived a given topic to be important but whose adolescents did not discuss that topic at their most recent preventive visit ranged from 44.7% for puberty among parents of older adolescents to 87.2% for where to get SRH services among parents of younger adolescents. Gaps between importance and actual provider-adolescent discussions were significantly greater among parents of younger adolescents than parents of older adolescents on 7 of 8 topics assessed. Gaps were generally similar for parents of boys and parents of girls. However, parents of younger boys had a significantly greater gap regarding discussion of puberty (59.8% of parents of younger boys versus 46.2% of parents of younger girls; P = .02), and parents of older boys had a significantly greater gap regarding discussion about methods of birth control (76.9% of parents of older boys versus 55.6% of parents of older girls; P = .002).

DISCUSSION

This nationally representative survey examines prevalence of discussions between primary care providers and adolescents about a range of SRH topics and adolescent and parent interest in having these conversations. Although most parents and many adolescents think it is important for adolescents to discuss SRH topics with their providers, these discussions often do not occur during preventive visits. SRH discussions are particularly uncommon among younger adolescents, indicating critical missed opportunities for screening, education, and guidance. Within age groups, discussions about puberty were less common with younger boys than girls and discussions about birth control were less common with older boys than girls. Moreover, findings suggest that key elements of quality care associated with discussion about sensitive topics (eg, confidentiality conversations, time alone, assessment of adolescent sexual activity) are not sufficiently implemented.

Both parents and adolescents noted the importance of provider-adolescent discussions about selected SRH topics, including puberty, STIs and HIV, methods of birth control, and where to access SRH services. In previous studies, clinicians have expressed concern about negative parental reactions when they introduce sexual topics, a potential barrier to initiating such conversations.1,21 Notably, our findings suggest that most parents think it is important for providers to talk with their adolescents about these topics. In fact, across all SRH topics studied, more parents than adolescents noted the importance of providers having these conversations.

Although older adolescents were more likely to report provider-adolescent SRH discussions to be important, younger adolescents showed high levels of interest in certain topics, with half or more reporting that discussions about puberty, STIs and HIV, and where to get SRH services were important. Our findings suggest that parents and adolescents agree with professional guidelines that conversations about SRH begin in early adolescence.2,5,6 Previous research on parent and adolescent attitudes regarding delivery of confidential preventive services, however, found that most parents and adolescents supported initiation of confidential services in middle or late adolescence.22 Thus, although parents and teenagers commonly perceive that provider-adolescent discussions about certain SRH topics are important, less consensus exists on whether these conversations should occur confidentially with young adolescents.22

Professional organizations recommend that providers routinely have conversations about confidentiality with adolescent patients and their parents and ensure time alone during preventive visits beginning in early adolescence.2,5,23 Ours is among the first studies to examine prevalence of confidentiality conversations and implementation of time alone with adolescents as young as ages 11 and 12. Consistent with previous research,8,24 confidentiality conversations and time alone during the most recent preventive visit were infrequent across all adolescent ages. Compared with older adolescents, younger adolescents were less likely to report confidentiality conversations and time alone, with fewer than one-quarter reporting either of these practices. Despite robust evidence regarding benefits of confidentiality provisions,8,25,26 our findings and previous research reveal a substantial divergence between professional guidelines and implementation of confidentiality practices in adolescent preventive care.1,8,24 Multiple factors may contribute to lack of confidential care, ranging from knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of providers, parents, and adolescents to clinic-level characteristics, such as protocols, workflows, physical space, and billing mechanisms.26

Fewer than one-third of adolescents reported discussions about SRH topics other than puberty during their most recent preventive visit. Our findings suggest clear gaps between parent- and adolescent-perceived importance of discussing SRH topics and adolescents’ actual experience. These gaps are particularly notable for younger adolescents. Similar gaps have been found with other potentially sensitive adolescent health topics.27 Thus, although parents and adolescents think that provider-adolescent conversations about SRH are important, providers frequently miss opportunities to engage around these topics.

Discussions about SRH are often sensitive for adolescents regardless of gender, and many youth are uncomfortable raising these topics without provider prompting.28 In previous research, investigators found that every time a conversation about sexuality occurred during an adolescent preventive visit, providers initiated it.25 Such findings point to the importance of provider initiation of SRH discussions, which may be facilitated through training and systems-level supports.1,29 For example, routine use of health checklists and/or screening questionnaires may increase the likelihood of discussing SRH and other potentially sensitive topics with adolescents during clinic visits.23 Ensuring that adolescents are prepared to engage with providers about SRH, through formal and informal health education, may be another strategy to address observed gaps in SRH discussions.

Study strengths include a national sample spanning the developmental continuum from early to later adolescence, a focus on SRH services within the context of primary care, and assessment of adolescents’ experiences discussing a broad range of SRH topics with providers. Limitations include use of retrospective self-report data, although previous research suggests that adolescent self-report of health care services is highly accurate and reliable.30,31 Another limitation is that survey questions assessed provider-adolescent interactions at only the most recent preventive visit. Providers may choose not to cover all SRH topics during a single visit because specific topics may not be relevant for all adolescents at every preventive care visit. Although 11-to 12-year-olds might have reported on visits that occurred before adolescence, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening and counseling on SRH topics during preventive visits starting as early as 7 years.5 A final limitation is that we did not examine how providers approached SRH discussions with adolescents or who initiated these discussions, both of which may impact the quality and effectiveness of these interactions.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings reveal that primary care providers frequently miss opportunities for critical conversations about SRH with adolescents, particularly with younger adolescents, and for some topics, with boys. Further research to identify strategies that enhance providers’ capacities to engage adolescents in SRH discussions will be helpful. It will also be important for research and interventions to address structural barriers and facilitators to provider/adolescent SRH conversations within primary care systems.12,16

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Professional organizations recommend that adolescent sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in primary care settings include education about confidentiality, time alone for adolescents with health care providers, developmentally appropriate screening and counseling on SRH topics, and appropriate biomedical services.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

This study is among the first population-based studies to examine adolescents’ receipt of screening and counseling about SRH topics in primary care. We found that provider-adolescent discussions about SRH do not occur routinely during preventive visits, especially among younger adolescents.

FUNDING:

Supported by cooperative agreement U48DP005022-04-05 (Dr Sieving, principal investigator), funded by the Prevention Research Center Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by funds from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services (T71MC00006; Dr Sieving, principal investigator).

ABBREVIATIONS

- SRH

sexual and reproductive health

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2020-049411.

This work was presented in part at the annual meeting of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine; March 2020; virtual conference.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sieving RE, Mehus C, Catallozzi M, et al. Understanding primary care providers’ perceptions and practices in implementing confidential adolescent sexual and reproductive health services. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(4): 569–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcell AV, Burstein GR; Committee on Adolescence. Sexual and reproductive health care services in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5): e20172858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society for Adolescent Medicine. Access to health care for adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(4): 342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edman JC, Adams SH, Park MJ, Irwin CE Jr. Who gets confidential care? Disparities in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4): 393–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elster AB, Kuznets NJ. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS): Recommendations and Rationale. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04): 1–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grilo SA, Catallozzi M, Santelli JS, et al. Confidentiality discussions and private time with a health-care provider for youth, United States, 2016. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(3): 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams SH, Park MJ, Twietmeyer L, Brindis CD, Irwin CE Jr. Association between adolescent preventive care and the role of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(1):43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kost K, Maddow-Zimet I, Apraia A. Pregnancies, births, and abortions among adolescents and young women in the United States, 2013: national and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/us-adolescent-pregnancy-trends-2013. Accessed April 21, 2021

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases: adolescents and young adults. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/life-stages-populations/adolescents-youngadults.htm. Accessed April 18, 2021

- 12.Boekeloo BO. Will you ask? Will they tell you? Are you ready to hear and respond?: barriers to physician-adolescent discussion about sexuality. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):111–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander SC, Christ SL, Fortenberry JD, et al. Identifying types of sex conversations in adolescent health maintenance visits. Sex Health. 2016;13(1): 22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copen CE, Dittus PJ, Leichliter JS. Confidentiality Concerns and Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 15–25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams SH, Park MJ, Irwin CE Jr. Adolescent and young adult preventive care: comparing national survey rates. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):238–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santelli JS, Klein JD, Song X, et al. Discussion of potentially sensitive topics with young people. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20181403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcell AV, Gibbs SE, Pilgrim NA, et al. Sexual and reproductive health care receipt among young males aged 15–24. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(4):382–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ipsos. KnowledgePanel. Available at: https:/www.ipsos.com/en-us/solutions/public-affairs/knowledgepanel. Accessed April 18, 2021

- 19.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th ed. Washington, DC: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee MD, Rubin SE, Campos G, O’Sullivan LF. Challenges of providing confidential care to adolescents in urban primary care: clinician perspectives. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(1):37–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song X, Klein JD, Yan H, et al. Parent and adolescent attitudes towards preventive care and confidentiality. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2): 235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford C, English A, Sigman G. Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper for the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):160–167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Sullivan LF, McKee MD, Rubin SE, Campos G. Primary care providers’ reports of time alone and the provision of sexual health services to urban adolescent patients: results of a prospective card study. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(1):110–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Pollak KI, et al. Sexuality talk during adolescent health maintenance visits. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pampati S, Liddon N, Dittus PJ, Adkins SH, Steiner RJ. Confidentiality matters but how do we improve implementation in adolescent sexual and reproductive health care? J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(3):315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santelli JS, Grilo SA, Klein JD, et al. The unmet need for discussions between health care providers and adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Same RV, Bell DL, Rosenthal SL, Marcell AV. Sexual and reproductive health care: adolescent and adult men’s willingness to talk and preferred approach. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2):175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Cleave J New directions to improve preventive care discussions for adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20183618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Child Health Insurance Research Initiative. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein JD, Graff CA, Santelli JS, Hedberg VA, Allan MJ, Elster AB. Developing quality measures for adolescent care: validity of adolescents’ self-reported receipt of preventive services. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(1 pt 2):391–404 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]