Abstract

Frequency-dependent phase velocity was measured in 8 cancellous-bone-mimicking phantoms consisting of suspensions of randomly-oriented nylon filaments (simulating trabeculae) in a soft-tissue-mimicking medium (simulating marrow). Trabecular thicknesses ranged from 152 – 356 microns. Volume fractions of nylon filament material ranged from 0 to 10%. Phase velocity varied approximately linearly with frequency over the range from 300 to 700 kHz. The increase in phase velocity (compared with phase velocity in a phantom containing no filaments) at 500 kHz was approximately proportional to volume fraction occupied by nylon filaments. The derivative of phase velocity with respect to frequency was negative and exhibited nonlinear, monotonically-decreasing dependence on volume fraction. The dependencies of phase velocity and its derivative on volume fraction in these phantoms were similar to those reported in previous studies on 1) human cancellous bone and 2) phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water.

Keywords: bone, trabecular, cancellous, velocity, dispersion

PACS code: 4380-Qf

I. INTRODUCTION

Bone sonometry is now an accepted method for diagnosis of osteoporosis (Langton and Njeh, 2004; Laugier, 2008). Speed of sound (SOS) in cancellous bone is highly correlated with bone mineral density (Rossman et al., 1989, Tavakoli and Evans, 1991, Zagzebski et al., 1991, Njeh et al., 1996, Laugier et al., 1997, Nicholson et al., 1998, Hans et al., 1999, Trebacz and Natali, 1999), which is an indicator of systemic osteoporotic fracture risk (Cummings et al., 1993). Calcaneal SOS (in combination with broadband ultrasound attenuation or BUA) has been shown to be predictive of hip fractures in women in prospective studies (Hans et al., 1996, Miller et al., 2002, Hans et al., 2004, Huopio et al., 2004, Schott et al., 2005, Krieg et al., 2006).

Despite the clinical utility of SOS, the mechanisms responsible for variations of SOS in cancellous bone are not well understood yet. Unlike soft tissues, which typically exhibit positive dispersion (phase velocity increasing with ultrasonic frequency) (O’Donnell et al., 1981), cancellous bone exhibits negative dispersion (Nicholson et al., 1996; Strelitzki and Evans, 1996; Droin et al., 1998; Wear, 2000a; Wear, 2000b). This negative dispersion may be explained using a stratified model (Brekhovskikh, 1980, Hughes et al., 1999, Wear, 2001, Qin, 2001), modified Biot-Attenborough theory (Lee et al., 2003), a restricted-bandwidth form of the Kramers-Kronig dispersion relations (Waters and Hoffmeister, 2005) or from the interference of two or more positively-dispersive pulses (Marutyan et al., 2006; Marutyan et al., 2007; Bauer et al., 2008; Anderson et al., 2008).

Measurements on cancellous-bone-mimicking phantoms can provide insight into the determinants of phase velocity and dispersion. The present study complements a previous study, which showed that for phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water, phase velocity and dispersion are primarily determined by volume fraction occupied by nylon wires (Wear, 2005a). In the present study, a new phantom design is utilized. Water is replaced by soft-tissue-mimicking material, which is a more realistic surrogate for marrow than water. Also in the present study, parallel nylon wires are replaced by randomly-oriented nylon filaments. In cancellous bone, the orientation of trabeculae is somewhere in between these two extremes.

II. METHODS

A. Phantoms

Eight phantoms containing nylon filaments (simulating trabeculae) in proprietary soft tissue-mimicking material (simulating marrow) (CIRS Inc., Norfolk, VA) were interrogated. Figure 1 shows a picture of a phantom. A reference phantom containing only soft tissue-mimicking material was also interrogated. Table 1 shows the phantom properties. Three of the phantoms contained nylon filaments with diameter equal to 152 μm, which is reasonably close to the mean trabecular thickness in human calcaneus, 127 μm (Ulrich, 1999). The dimensions for all phantoms were 80 mm X 60 mm X 25 mm. The scanning window dimensions for all phantoms were 60 X 50 mm.

Figure 1.

A phantom containing nylon filaments and a reference phantom.

Table 1.

Properties of phantoms.

| Filament Diameter (μm) |

Filament Length (mm) |

Filament Number Density (# per cc) |

Volume Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | 0 | 0 |

| 152 | 10 | 100 | 1.8 |

| 203 | 10 | 100 | 3.2 |

| 229 | 10 | 100 | 4.1 |

| 330 | 10 | 100 | 8.5 |

| 356 | 10 | 100 | 9.9 |

| 152 | 12 | 100 | 2.2 |

| 229 | 12 | 100 | 3.3 |

| 152 | 12 | 200 | 4.4 |

Nylon is a useful surrogate for cancellous bone material. The longitudinal sound speed in nylon (2600 m/s) is near the low end of the range reported for mineralized bone material (2800 – 4000 m/s, near 500 kHz) (Duck, 1990). The dependencies of phase velocity and dispersion on volume fraction in phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires in water are similar to those in human cancellous bone (Wear, 2005a). Nylon wires exhibit frequency-dependent scattering similar to that exhibited by cancellous bone (Wear, 1999; Wear, 2004).

A previously reported phantom design, consisting of cubic granules of gelatin immersed in epoxy, has been shown to be useful for the prediction of the dependences of phase velocity, dispersion, and attenuation on porosity of cancellous bone (Clarke et al., 1994; Strelitzki et al., 1997).

B. Ultrasonic Methods

A Panametrics (Waltham, MA) 5800 pulser/receiver was used. Samples were interrogated in through-transmission in a water tank using a pair of coaxially-aligned, Panametrics 500 kHz, broadband, 0.75” (1.9 cm) diameter, 1.5” (3.8 cm) focal length transducers. The propagation path between transducers was twice the focal length. Received radio frequency (RF) signals were digitized (8 bit, 10 MHz) using a LeCroy (Chestnut Ridge, NY) 9310C Dual 400 MHz oscilloscope and stored on computer (via GPIB) for off-line analysis. The transducers were maintained in constant positions. Each phantom was suspended in the water tank by a 2-dimensional stage that enabled movement of the phantom in the two dimensions perpendicular to the beam propagation direction. Attenuation measurements were made at 15 positions throughout each phantom scanning window corresponding to a 3 X 5 grid in which neighboring measurements were separated by 1 cm.

Frequency-dependent phase velocity, cp(f), was computed using

| (1) |

where f is frequency, Δϕ(f) is the difference in unwrapped phases (see next paragraph) of the received signals with and without the phantom in the water path, d is the phantom thickness (2.5 cm), and cw is the temperature-dependent speed of sound in distilled water given by (Kaye and Laby, 1973)

| (2) |

and T is the temperature in degrees Celsius. Temperature, measured with a digital thermometer, was about 20° for these measurements, which meant that cw was about 1482 m/s.

The unwrapped phase difference, Δϕ(f), was computed as follows. Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT’s) of the digitized received signals were taken. The phase of the signal at each frequency was taken to be the inverse tangent of the ratio of the imaginary to real parts of the FFT at that frequency. Since the inverse tangent function yields principal values between -π and π, the phase had to be unwrapped by adding an integer multiple of 2π to all frequencies above each frequency where a discontinuity appeared.

Dispersion was characterized by the slope, dcp/df, of a linear least-squares regression fit of cp(f) vs. f over the range from 300 to 700 kHz, which roughly corresponded to the system −6 dB bandwidth.

III. RESULTS

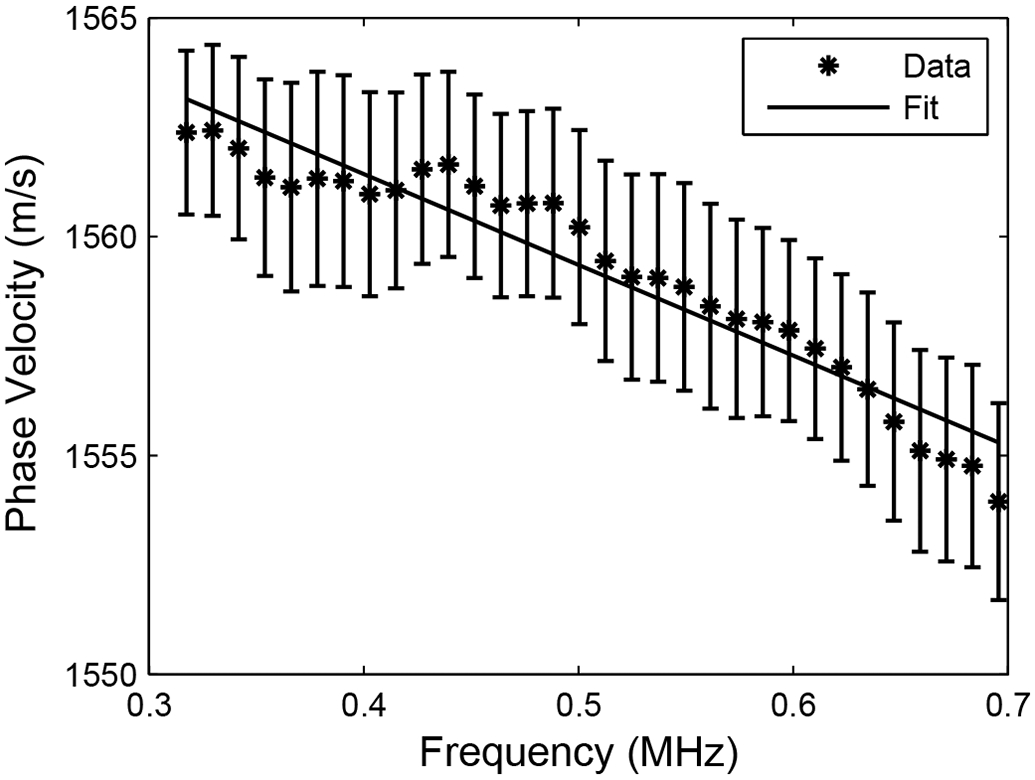

Figure 2 shows measurements of phase velocity (cp) vs. frequency (f) for one phantom. Phase velocity declined approximately linearly with frequency for all phantoms.

Figure 2.

Measurements of phase velocity vs. frequency for one phantom. A linear fit is also shown. Error bars denote standard errors.

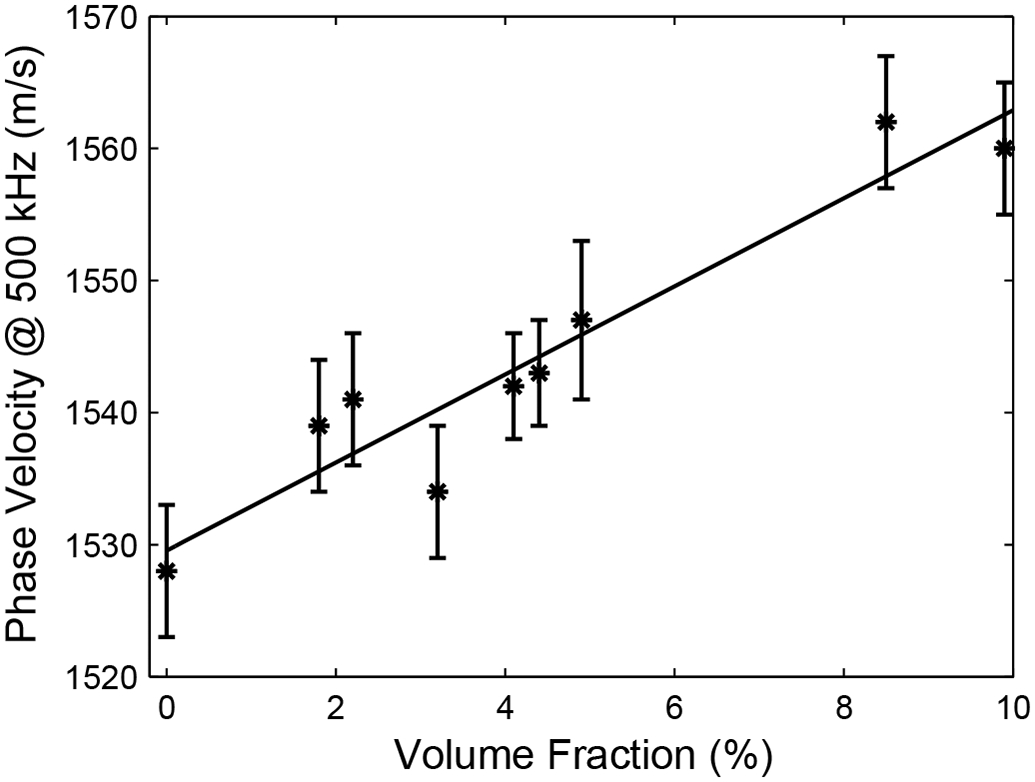

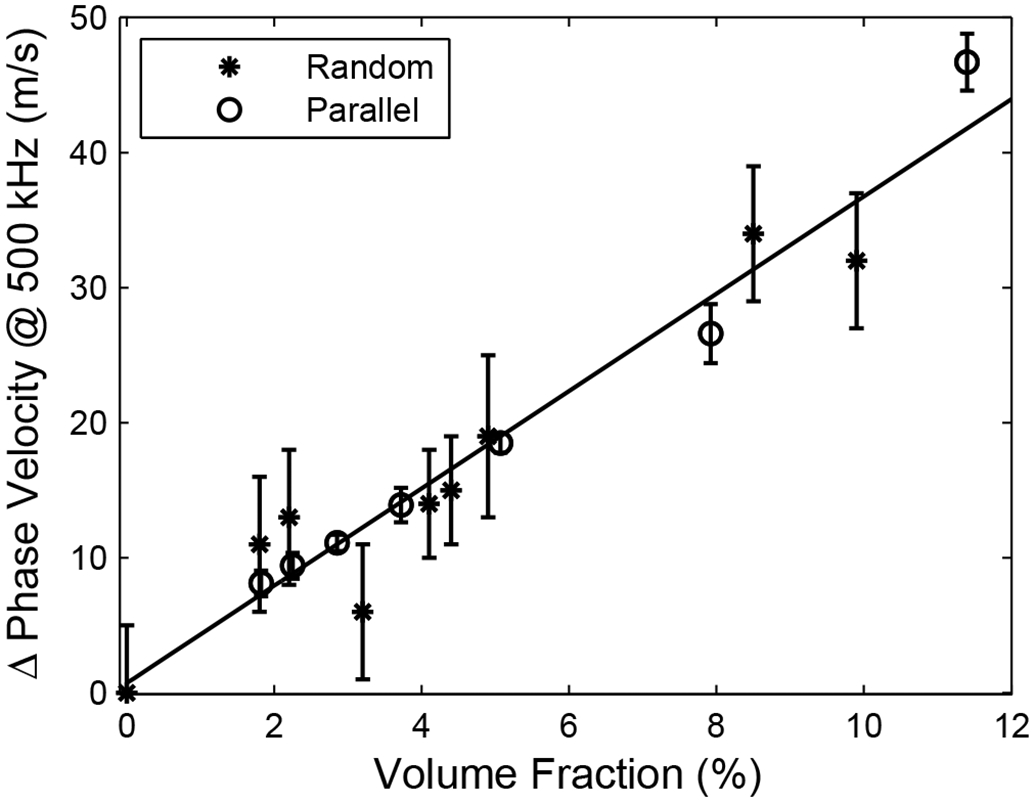

Figure 3 shows measurements of cp(500 kHz) vs. volume fraction (VF) on all the phantoms. A linear fit, cp(500 kHz) = 1530 + 3.3 VF m/s (where VF is expressed as a percentage), is in good agreement with the data.

Figure 3.

Average phase velocity at 500 kHz vs. volume fraction occupied by nylon filaments. Error bars denote standard deviations.

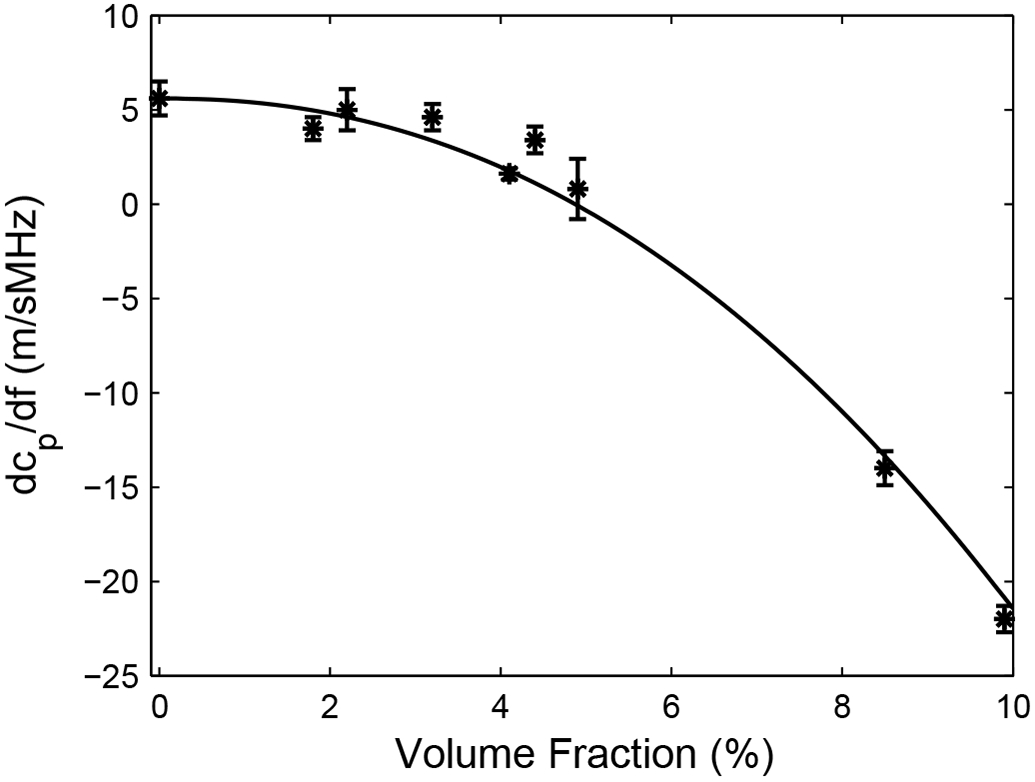

Figure 4 shows measurements of dcp/df vs. VF for all phantoms. A power law fit, dcp/df = 5.6 – 0.18 VF 2.1 is also shown. Values for dcp/df ranged from +5 to −22 m/sMHz, which is consistent with values reported in human calcaneus in vitro. A greater range for dcp/df has been measured in vivo. See Table 2.

Figure 4.

dcp/df vs. volume fraction occupied by nylon filaments. Error bars denote standard deviations.

Table 2.

Estimates of the first derivative of phase velocity with respect to frequency, dcp/df, in human calcaneus from Nicholson et al. (1996, Table 1), Strelitzki and Evans (1996, Table 2), Droin, et al. (1998, Table 1), Wear (2000a, Table 1), and Wear (2007, Table 2). N is the number of calcaneus samples upon which measurements were based.

| Author(s) | N | Frequency Range (kHz) |

Age Range (years) |

dcp/df (mean ± standard deviation) (m/sMHz) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicholson et al. | in vitro | 70 | 200 - 800 | 22 - 76 | −40 |

| Strelitzki and Evans | in vitro | 10 | 600 - 800 | unknown | −32 ± 27 |

| Droin et al. | in vitro | 15 | 200 - 600 | 69 - 89 | −15 ± 13 |

| Wear (2000) | in vitro | 24 | 200 - 600 | unknown | −18 ± 15 |

| Wear (2007) | in vivo | 73 | 300 - 600 | 21 - 78 | −59 ± 52 |

IV. DISCUSSION

Phase velocity (cp) in phantoms consisting of randomly-distributed nylon filaments (simulating trabeculae) immersed in soft-tissue-mimicking material (simulating marrow), is an approximately linear, monotonically-increasing function of volume fraction. The derivative of phase velocity with respect to frequency, dcp/df, in these phantoms is a nonlinear, monotonically-decreasing function of volume fraction. Both phase velocity and dcp/df appear to be primarily determined by volume fraction. Since group velocity is determined by cp and dcp/df (Duck, 1990; Wear, 2005a), then group velocity must also be primarily determined by volume fraction.

A previous study showed similar trends for phase velocity and dcp/df in phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water (Wear, 2005a). In Figure 5, the change in phase velocity (compared with the zero volume fraction level) is plotted vs. volume fraction for both the previous and current phantom designs. In Figure 6, the change in dcp/df (compared with the zero volume fraction level) is plotted vs. volume fraction for both phantom designs. Despite significant differences in micro-architecture and fluid media for the two types of phantoms, the effect of volume fraction on phase velocity and dcp/df is remarkably similar. Moreover, it was argued previously that the volume-fraction dependencies of phase velocity and dcp/df in phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water were similar to those reported in cancellous bone in vitro (Wear, 2005a; Wear et al., 2005b). These empirical results, taken collectively, suggest that changes in phase velocity and dcp/df observed in human cancellous bone are primarily determined by volume fraction.

Figure 5.

Change in phase velocity (compared with the zero volume fraction level) vs. volume fraction for the present study, which utilized randomly distributed nylon filaments in soft-tissue-mimicking material, and a previous study (Wear, 2005), which utilized phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water. Error bars denote standard deviations.

Figure 6.

Change in dcp/df (compared with the zero volume fraction level) vs. volume fraction for the present study, which utilized randomly distributed nylon filaments in soft-tissue-mimicking material, and a previous study (Wear, 2005) which utilized phantoms consisting of parallel nylon wires immersed in water. Error bars denote standard deviations.

Nicholson et al. (2001) measured phase velocity in 69 human calcaneal cancellous bone cubes. They found that, after the data were adjusted for density (which is a measure of bone quantity rather than micro-architecture), there was no significant dependence of phase velocity on micro-architectural parameters. The dominant role of bone quantity (as opposed to micro-architecture) was also seen in a three-dimensional simulation study by Haïat et al. (2007), in which variations in volume fraction of micro CT reconstructions of human cancellous femur explained 94% of variations in SOS.

In measurements on human cancellous lumbar spine, Hans et al. (1999) found SOS to be approximately 2-3% higher in the axial direction compared with the sagittal and coronal directions. Since bone volume fraction is identical in all three orientations, these results suggest that the arrangement of trabeculae, not just the quantity of trabecular material (i.e. volume fraction), does play a role in determining SOS. In these experiments, however, the comparison was between extreme differences in angle between the ultrasound propagation direction and the predominant trabecular direction: approximately parallel (axial) vs. approximately perpendicular (sagittal and coronal). Less dramatic variations in trabecular arrangement, such as those in the phantom experiments and simulation study described above, may not necessarily produce significant variations in SOS or phase velocity.

Anisotropy is more pronounced in bovine cancellous bone. Hosokawa and Otani (1998) found fast wave velocity to be approximately 25% greater in the direction parallel to the predominant trabecular orientation compared with other directions in bovine cancellous tibia. Hughes et al. (1999) found fast wave velocity to be approximately 100% greater in the parallel direction in bovine cancellous tibia and femur. Hoffmeister et al. (2000) found SOS to be approximately 25% higher in the parallel direction in bovine cancellous tibia. Given the dependence of cancellous bone microstructure on loading conditions, and the differences in loading conditions between humans and cows, the enhanced anisotropy in bovine cancellous bone is perhaps not surprising.

V. CONCLUSION

The experiments on phantoms reported here reinforce previous results on phantoms and human cancellous bone in vitro in which volume fraction of trabeculae is the dominant determinant of phase velocity. In bovine cancellous bone, however, both volume fraction and trabecular orientation are significant determinants of phase velocity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to Laura Perfetti and Heather Miller, C.I.R.S., Norfolk, VA, for assistance in phantom design and construction. The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the Food and Drug Administration.

REFERENCES

- Anderson CC, Marutyan KR, Holland MR, Wear KA, and Miller JG, (2008). “Interference between wave modes may contribute to the apparent negative dispersion observed in cancellous bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 124, 1781–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AQ, Marutyan KR, Holland MR, and Miller JG, (2008), “Negative dispersion in bone: The role of interference in measurements of the apparent phase velocity of two temporally overlapping signals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 123, 2407–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekhovskikh LM, (1980). Waves in Layered Media. (Academic Press, New York, NY: ). [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AJ, Evans JA, Truscott JG, Milner R, and Smith MA, (1994), “A phantom for quantitative ultrasound of trabecular bone,” Phys. Med. Biol, 39, 1677–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Browner W, Cauley J, Ensrud KE, Genant HK, Palermo L, Scott J, and Vogt TM, (1993). “Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures.” Lancet, 341, 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droin P, Berger G, and Laugier P, (1998), “Velocity dispersion of acoustic waves in cancellous bone,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferro. Freq. Cont, 45, 581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck FA (1990), Physical properties of tissue. (University Press, Cambridge, UK: ). [Google Scholar]

- Haïat G, Padilla F, Peyrin F, and Laugier P, (2007), “Variation of ultrasonic parameters with microstructure and material properties of trabecular bone: a 3D model simulation,” J. Bone Miner. Res, 22, 665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans D, Dargent-Molina P, Schott AM, Sebert JL, Cormier C, Kotzki PO, Delmas PD, Pouilles JM, Breart G, and Meunier PJ, (1996). “Ultrasonographic heel measurements to predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS prospective study,” Lancet, 348, 511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans D, Wu C, Njeh CF, Zhao S, Augat P, Newitt D, Link T Lu Y, Majumdar S, and Genant HK, (1999), “Ultrasound velocity of trabecular cubes reflects mainly bone density and elasticity,” Calcif. Tissue Int, 64, 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans D, Schott AM, Duboeuf F, Durosier C, and Meunier PJ, (2004) “Does follow-up duration influence the ultrasound and DXA prediction of hip fracture? The EPIDOS prospective study,” Bone, 35, 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister BK, Whitten SA, and Rho JY, (2000), “Low-Megahertz ultrasonic properties of bovine cancellous bone,” Bone, 26, 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa A and Otani T (1998), “Acoustic anisotropy in bovine cancellous bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 103, 2718–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ER, Leighton TG, Petley GW, and White PR, (1999), “Ultrasonic propagation in cancellous bone: a new stratified model,” Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, 25, 811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huopio J Kroger H Honkanen R, Jurvelin J, Saarikoski S, and Alhava E (2004), “Calcaneal ultrasound predicts early postmenopausal fractures as well as axial BMD. A prospective study of 422 women,” Osteo. Int, 15, 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye GWC, and Laby TH, (1973), Table of Physical and Chemical Constants. (Longman, London, UK: ). [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M, Cornuz J, Ruffieux C, et al. (2006) “Prediction of hip fracture risk by quantitative ultrasound in more than 7000 Swiss women ≥ 70 years of age: comparison of three technologically different bone ultrasound devices in the SEMOF study,” J. Bone. Miner. Res, 21, 1457–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton CM, and Njeh CF, ed. (2004), The Physical Measurement of Bone, Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol, U. K. [Google Scholar]

- Laugier P, Droin P, Laval-Jeantet AM, and Berger G, (1997), “In vitro assessment of the relationship between acoustic properties and bone mass density of the calcaneus by comparison of ultrasound parametric imaging and quantitative computed tomography,” Bone, 20, 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugier P, “Instrumentation for In Vivo Ultrasonic Characterization of Bone Strength,” (2008), IEEE Trans Ultrason. Ferro. Freq. Cont, 55, 1179–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KI, Roh H, and Yoon SW (2003), “Acoustic wave propagation in bovine cancellous bone: Application of the modified Biot-Attenborough model,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 114, 2284–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marutyan KR, Holland MR, and Miller JG, (2006), “Anomalous negative dispersion in bone can result from the interference of fast and slow waves,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 120, EL 55 – EL61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marutyan KR, Bretthorst GL, and Miller JG, (2007), “Bayesian estimation of the underlying bone properties from mixed fast and slow mode ultrasonic signals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 121, EL8 – EL14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PD, Siris ES, Barrett-Connor E, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Chen Y, Berger ML, Santora AC, and Sherwood LM, (2002), “Predeiction of fracture risk in postmenopausal white women with peripheral bone densitometry: evidence from the national osteoporosis risk assessment,” J. Bone & Miner. Res, 17, 2222–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njeh CF, Hodgskinson R, Currey JD, and Langton CM, (1996). “Orthogonal relationships between ultrasonic velocity and material properties of bovine cancellous bone.” Med. Eng. Phys, 18, pp. 373–381, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson PHF , Lowet G, Langton CM, Dequeker J, and Van der Perre G, (1996), “Comparison of time-domain and frequency-domain approaches to ultrasonic velocity measurements in trabecular bone,” Phys. Med. Biol, 41, 2421–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson PHF, Muller R, Lowet G, Cheng XG, Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P Van Der Perre G, Dequeker J, and Boonen S (1998). “Do quantitative ultrasound measurements reflect structure independently of density in human vertebral cancellous bone?” Bone. 23, pp. 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson PHF, Muller R, Cheng XG, Ruegsegger P Van der Perre G, Dequeker J, and Boonen S, (2001), “Quantitative ultrasound and trabecular architecture in the human calcaneus,” J. Bone & Miner. Res, 16, 1886–1892). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell M, Jaynes ET, and Miller JG (1981), “Kramers-Kronig relationship between ultrasonic attenuation and phase velocity.” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 69, 696–701. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman P, Zagzebski J, Mesina C, Sorenson J, and Mazess R, (1989), “Comparison of Speed of Sound and Ultrasound Attenuation in the Os Calcis to Bone Density of the Radius, Femur and Lumbar Spine,” Clin. Phys. Physiol.Meas, 10, 353–360.’ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott M, Hans D, Duboeuf F, Dargent-Molina P, Jajri T, Breart G, and Meunier PJ, (2005). “Quantitative ultrasound parameters as well as bone mineral density are better predictors of trochanteric than cervical hip fractures in elderly women. Results from the EPIDOS study,” Bone, 37, 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelitzki R, and Evans JA, (1996), “On the measurement of the velocity of ultrasound in the os calcis using short pulses,” Eur. J. Ultrasound, 4, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Strelitzki R, Evans JA, and Clarke AJ, (1997), “The influence of porosity and pore size on the ultrasonic properties of bone investigated using a phantom material,” Osteo. Int, 7, 370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli MB and Evans JA. (1991). Dependence of the velocity and attenuation of ultrasound in bone on the mineral content. Phys. Med. Biol, 36, 1529–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebacz H, and Natali A. (1999). “Ultrasound velocity and attenuation in cancellous bone samples from lumbar vertebra and calcaneus,” Osteo. Int’l, 9, 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D, van Rietbergen B, Laib A, and Rüegsegger P, (1999), “The ability of three-dimensional structural indices to reflect mechanical aspects of trabecular bone,” Bone, 25, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters KR, and Hoffmeister BK, (2005), “Kramers-Kronig analysis of attenuation and dispersion in trabecular bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 118, 3912–3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (1999), “Frequency dependence of ultrasonic backscatter from human trabecular bone: theory and experiment,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 106, 3659–3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2000a), “Measurements of phase velocity and group velocity in human calcaneus,” Ultrasound. Med. Biol, 26, 641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2000b), “The effects of frequency-dependent attenuation and dispersion on sound speed measurements: applications in human trabecular bone”, IEEE Trans Ultrason. Ferro. Freq. Cont, 47, 265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2001), “A stratified model to predict dispersion in trabecular bone,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferro. Freq. Cont, 48, 1079–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2004), “Measurement of dependence of backscatter coefficient from cylinders on frequency and diameter using focused transducers—with applications in trabecular bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 115, 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2005a) “The dependences of phase velocity and dispersion on trabecular thickness and spacing in trabecular bone-mimicking phantoms,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 118, 1186–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, Laib A, Stuber AP, and Reynolds JC, (2005b), “Comparison of measurements of phase velocity in human calcaneus to Biot theory,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 117, 3319–3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear KA, (2007), “Group Velocity, Phase Velocity, and dispersion in Human Calcaneus In Vivo,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 121, 2431–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski JA, Rossman PJ, Mesina C, Mazess RB, and Madsen EL, (1991). “Ultrasound transmission measurements through the os calcis,” Calcif. Tissue Int’l, 49, 107–111, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]