Abstract

The intensive care units in North West London are part of one of the oldest critical care networks in the UK, forming a mature and established strategic alliance to share resources, experience and knowledge for the benefit of its patients. North West London saw an early surge in COVID-19 admissions, which urgently threatened the capacity of some of its intensive care units even before the UK government announced lockdown. The pre-existing relationships and culture within the network allowed its members to unite and work rapidly to develop agile and innovative solutions, protecting any individual unit from becoming overwhelmed, and ultimately protecting its patients. Within a short 50-day period 223 patients were transferred within the network to distribute pressures. This unprecedented number of critical care transfers, combined with the creation of extra capacity and new pathways, allowed the region to continue to offer timely and unrationed access to critical care for all patients who would benefit from admission. This extraordinary response is a testament to the power and benefits of a regionally networked approach to critical care, and the lessons learned may benefit other healthcare providers, managers and policy makers, especially in regions currently facing new outbreaks of COVID-19.

Keywords: Critical care network, transfer medicine, COVID-19, critical care capacity, emergency preparedness

Introduction

COVID-19 hit North West London early, with hospital admissions soaring even before the United Kingdom (UK) entered lockdown. This was particularly marked in outer North West London, which is densely populated and home to a high-risk population. This placed unprecedented demand on capacity and resources of Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in the region, leading to the highest frequency of critical care transfers that have ever been, and may ever be, performed in North West London.

The North West London Critical Care Network (NWLCCN) is a strategic alliance of acute hospitals, health commissioning groups and the London Ambulance Service (LAS), covering a population of 2·4 million with approximately 186 commissioned critical care beds. 1 As one of the first-generation adult critical care networks in the UK, NWLCCN has extensive experience in emergency and winter surge planning, and was pivotal in creating CRITCON, a tool for ICU surge reporting and management in response to 2009 H1N1 influenza. 2 , 3

Critical care transfers are complex. They necessitate caring for physiologically vulnerable patients in an isolated environment, incurring the stress of acceleration/deceleration and risking accidental discontinuity in treatment, life support or monitoring. With an incidence of serious adverse events of up to 8·9%, critical care transfers should only be undertaken when clinically indicated, with clear benefit to the patient. 4 Ordinarily, these risks are mitigated across NWLCCN by extensive transfer training, use of protocols and dedicated mobile application, adherence to national guidelines and standardised transfer equipment, and close collaboration with LAS. 5

The COVID-19 pandemic posed an unrivalled challenge. NWLCCN needed to deliver a coordinated and innovative response to enable the sustained decompression of critical care admission surges across multiple sites over many weeks. The strength of the collegiate culture and working relationships within NWLCCN was a key enabler, dissipating the pressures of the pandemic and protecting any unit from becoming overwhelmed.

This article presents some of the strategies, pathways and solutions developed within NWLCCN to manage the pandemic from three viewpoints: first, Northwick Park Hospital (NPH), NWLCCN’s busiest acute surge hospital; second, the NWLCCN Transfer Hub, set up in response to the pandemic; and third, Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust (RBHT), the biggest recipient of COVID-19 transfers within NWLCCN. We believe our experiences are testament to the power of collaborative working and a regionally-networked approach. We hope this may benefit other regions currently facing new outbreaks. 6

Transferring the critically ill from one of London’s hardest hit hospitals

Northwick Park Hospital was one of UK’s hardest hit hospitals for ICU COVID-19 admissions, relative to baseline critical care capacity. 7 NPH is a large district general hospital near Heathrow Airport, serving a diverse population of approximately one million, where Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities, at an increased risk of COVID-19, 8 predominate. It houses a tertiary Infectious Diseases service and one of London’s busiest emergency departments. These all contributed to what followed.

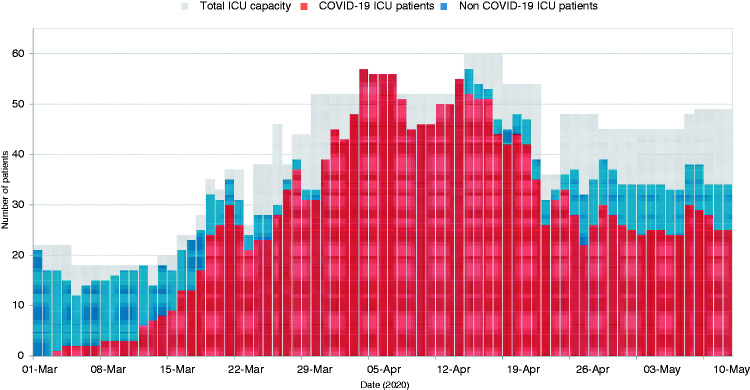

NPH acted early and pre-emptively. After the first COVID-19 case arrived in the UK on 31 January 2020, we initiated training and simulation to develop pathways for triage, safe intubation, and transfer to ICU for suspected COVID-19 patients under strict personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control precautions. On 3 March, these preparations were tested when we admitted one of the first intubated COVID-19 positive patients in the country to ICU. We were then among the first to witness the rapid, devastating impact of COVID-19 spreading through our local communities, with critical care demands soaring. Critical care capacity was increased in planned phases, with operating theatres, post-surgical recovery, and finally medical wards being converted into ICU beds. However, both the onset and rate of admissions at NPH were outliers within London and nationally, and these beds filled as quickly as they were opened (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Northwick Park Hospital’s daily ICU bed capacity, COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 bed occupancy.

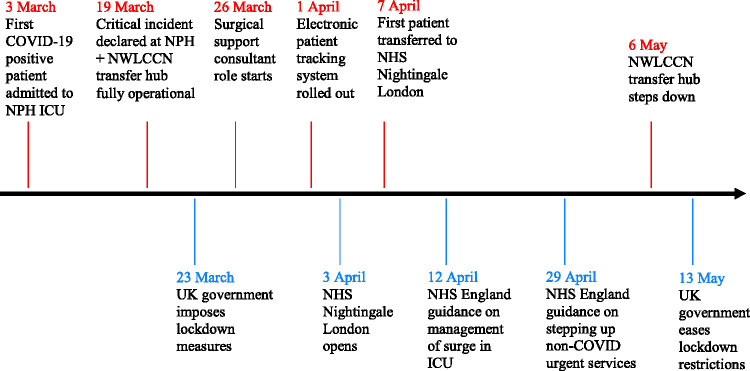

On 19 March, NPH declared a ‘critical incident’, as the number of ventilated COVID-19 patients exceeded available critical care beds and the rate of simultaneous new admissions exceeded staffing resources. 9 This occurred before the UK entered lockdown on 23 March, and the publication of clinical guidelines for the management of surge during the pandemic on 12 April (Figure 2). Capacity-driven inter-hospital transfers were already occurring, but the numbers of new cases warranted urgent escalation. We therefore requested assistance from NWLCCN to alleviate pressures on capacity by coordinating transfers of critically ill COVID-19 patients to other hospitals.

Figure 2.

Timeline of events in Northwick Park Hospital (above arrow) and UK (below arrow).

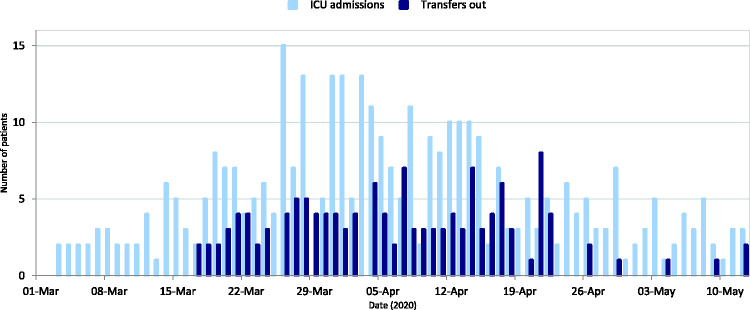

Throughout this surge we frequently reviewed over 20 patients daily for ICU admission, and intubated an average of 7·5 patients per day for several weeks. Every day we admitted enough patients to fill a medium-sized district general hospital ICU. Inter-hospital transfers were our only means of controlling capacity and ensuring provision of safe, high quality critical care (Figure 3). This bought us time to expand, and ultimately triple, our baseline ICU bed capacity.

Figure 3.

Daily admissions to and transfers out from Northwick Park Hospital ICU.

To support the high number of patients and inter-hospital transfers we adapted our processes; reorganising space, staffing, equipment, and training. 10 We upskilled non-intensive-care-trained health professionals, and deployed them into ICU. Hospital COVID-19 guidelines and standard operating procedures (SOPs) were rapidly created, with multidisciplinary collaboration between hospital management, ICU and infection control teams. An electronic patient tracking system was developed, allowing real-time monitoring of patient flow within the hospital.

Anaesthetists were assigned to dedicated intubating teams, and the entire multi-professional ICU team was providing hands-on care to critically unwell patients in line with national guidance. With elective surgery cancelled, consultant surgeons filled a new role as Surgical Support Consultants, 11 providing logistical support for expanding ICU capacity and organising the flow of patients in and out of ICU. Appropriate patients for inter-hospital transfers were identified and prepared nightly, and communicated to NWLCCN in the morning. Transfer teams, often arriving in full PPE, were met at a dedicated entrance and chaperoned to ICU for patient handover, with prepared drugs and equipment ready for transfer. These measures yielded substantial improvements in efficiency and safety, which allowed us to transfer out up to 8 patients a day and on one occasion conduct 4 transfers simultaneously.

From 1 March to 12 May, when national lockdown started to ease, we transferred out 136 of 365 (37%) patients admitted to ICU in NPH. Many patients owe their survival to the close collaboration and aid from NWLCCN and receiving hospitals.

Creating and coordinating NWLCCN transfer hub

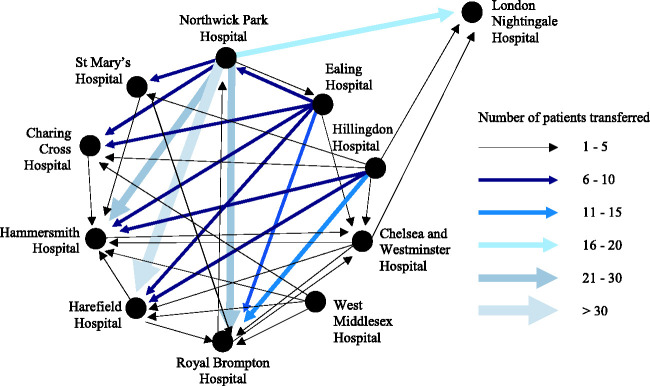

On 17 March 2020 the NWLCCN quarterly planning meeting was in session when NPH reached out for urgent support; COVID-19 admissions were rising, and NPH required mutual aid to maintain ICU capacity. With COVID-19 admissions forecast to increase exponentially across the region, it became clear that NWLCCN would need to unite to deliver sustained and high-volume patient transfers over the coming weeks to manage capacity at NPH and other NWLCCN ICUs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Transfers by location and volume within NWLCCN from 17th March to 6th May 2020.

A NWLCCN COVID-19 Transfer Hub was rapidly mobilised to manage the strategy and logistics of decompression. This was coordinated by three doctors, seconded to the role full-time and armed with a dedicated phone line and email address to act as a single point of contact for NWLCCN transfers. We joined video conferences each morning with medical directors from North West London hospitals, where ICU bed statuses were declared and anticipated staffing or equipment issues raised. We communicated closely throughout the day with ICU leads for real-time updates on the fluctuating operational and clinical pressures on the ground. Our minute-to-minute oversight of demand and capacity allowed us to tactically plan the volume and destinations of patient transfers. Over the coming weeks, this constant dialogue with ICUs formed the backbone of a close, collaborative relationship between the Hub and each of the clinical leads.

The organisation and logistics of transferring critically unwell patients during the COVID-19 crisis posed extra challenges to an already complex task fraught with inherent risk. 4 Our first challenge concerned staffing transfer teams. In England, save for specialised services, e.g. Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) transfers, adult critical care transfers are generally performed by referring hospital teams (often a critical care nurse and ICU or anaesthetic doctor). 12 This contrasts with the use of dedicated regionalised transfer teams in Scotland and Wales, and in paediatric practice. However, with ICUs rapidly expanding, and high rates of staff sickness and self-isolation, there were concerns that taking staff from already stretched ICUs could limit the volume and speed of transfers, and compromise care in the rest of the unit. Whilst receiving ICUs could frequently send transfer teams to retrieve patients, we recognised the need for a staffing safety-net to ensure that vital transfer work could continue reliably in all circumstances.

We therefore established an emergency bank of stand-by transfer volunteers consisting of critical care nurses, ICU doctors, and anaesthetists from the region. A prerequisite to joining the bank was evidence of formal training in transferring critically ill patients. At its peak, the bank had 69 members. The number of professionals volunteering to work when off-duty is testament to the culture within NWLCCN, and also a legacy of NWLCCN’s previous work on transfer training, education and transfer safety. 13 , 14 To support the bank’s operations, we adopted an app-based framework. This allowed volunteers to schedule shifts according to their availability, and facilitated the automatic distribution of Hub-developed SOPs for COVID-19 ICU patient transfers and other essential information to volunteers. In total, 36% of transfers were performed by retrieval teams from the receiving unit, 14% by sending teams from the decompressing units, and 26% by transfer volunteers, with the remaining 24% performed by LAS and out-of-sector teams. This patchwork approach allowed us to flex resources up or down on a daily basis to meet fluctuating demand.

Another challenge concerned transfer vehicles. As the degree of strain that COVID-19 would impose on LAS was uncertain, we secured the services of four additional independent ambulances. Two were equipped with transfer equipment including ventilators, thus ensuring that decompressing hospitals were not without vital equipment (e.g. for intra-hospital transfers or ad hoc additional bed capacity). We retained centralised control of the deployment of these vehicles, enabling them to be dispatched according to a real-time holistic appraisal of capacity and equipment pressures within NWLCCN. Overall, the Hub’s independent ambulances performed 71% of ICU transfers.

To the extent possible, we sought to anticipate transfer demand, and pre-positioned ambulances at expected sending or retrieving hospitals each morning. However, there were inherent limitations on our ability to pre-plan specific COVID-19 patient transfers due to rapid deteriorations in patient condition, and constant changes in ICU capacity at potential receiving hospitals. This continuous state of flux heightened the importance of clear communication in order to provide ICU consultants with immediate intelligence on sector-wide bed availability for mutual aid.

During the 50-day period from 17 March to 6 May 2020, the Hub oversaw 238 patient transfers (Table 1), at its peak coordinating 13 transfers in a single day, into seven different receiving ICUs. Over the Hub’s busiest seven-day period (commencing 4 April), we averaged nine transfers per day. Critical care transfers are usually driven by clinical escalation, and only very rarely by capacity; however, during these 50-days alone, we performed 223 capacity-driven transfers, nearly 10 times the annual average. Over 95% of patients transferred were (or were suspected to be) COVID-19 positive. While equipment and logistical challenges were occasionally reported, no incidents of death or serious clinical deterioration occurred during transfer.

Table 1.

Critical care transfers from North West London hospitals

| COVID-19 emergency response (17 March 2020–6 May 2020) | Equivalent 50-day period in 2019 | Annual average numbers (2017–2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of critical care transfers | 238 | 106 | 682 |

| Indication for transfer: | |||

| ICU capacity transfers | 223 (94.5%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (3.6%) |

| Clinical | 7 (3%) | 83 (78.3%) | 529 (77.5%) |

| Repatriation | 8 (3.5%) | 23 (21.7%) | 129 (18.9%) |

| Level of transfer: | |||

| Mechanically ventilated | 232 (97%) | 49 (46.2%) | 325 (47.6%) |

| Not mechanically ventilated | 6 (3%) | 57 (53.8%) | 357 (52.4%) |

A centralised Hub for transfer coordination was an essential enabler for optimising mutual aid delivery within NWLCCN. The Hub served as a real-time arbiter of ICU capacity pressures across NWLCCN, facilitating the rapid and resource-efficient delivery of a high volume of transfers. Centralising transfer coordination also reduced the associated organisational and logistical demands placed on ICU clinicians, allowing them to focus on clinical needs and patient care.

Streamlining transfers to receiving hospitals within the critical care network

RBHT is a specialist cardiothoracic centre. Its two campuses within North West London – The Royal Brompton Hospital and The Harefield Hospital – provide tertiary and quaternary care to a wide region of the country. RBHT is also the ECMO provider for South West England. During the pandemic, The Harefield Hospital was the designated cardiac surgical centre for West London and a COVID-19 Heart Attack Centre, while The Royal Brompton Hospital continued to provide veno-venous ECMO services. While maintaining receiving capabilities for these specialist pathways, RBHT provided the greatest mutual aid to other ICUs within North West London (Figure 4).

A number of enabling factors contributed to this ability. Firstly, as neither hospital has an emergency department, we received no direct COVID-19-related admissions. Moreover, we have substantial baseline ICU capacity, given our specialist surgical centre status. We could therefore restructure normal hospital operations to create dedicated ICUs for mutual aid within NWLCCN. At our peak, we surged to 32 ventilated COVID-19 beds at The Harefield Hospital and just under 80 at The Royal Brompton Hospital.

Secondly, we quickly recognised the importance of dedicated retrieval teams. As an ECMO provider, we are experienced in retrieving patients with severe acute respiratory failure. However, it became clear that transferring patients in large numbers during the pandemic posed significant challenges. Our transfers were initially conducted on a transfer-by-transfer basis, using the staff and equipment available. This was inefficient and limited our daily transfer capacity. We therefore introduced a dedicated retrieval rota, allocating a critical care consultant, registrar, and nurse from each hospital to retrievals each day. This provided an invaluable staffing resource to the Transfer Hub coordinators who could draw upon our retrieval capability and capacity; of the 104 patients received by RBHT from NWLCCN, 64% were retrieved using RBHT transfer teams. The clinical expertise and resources of our hospitals allowed us to transfer some of the sickest COVID-19 patients, including in the prone position when necessary.

Thirdly, we streamlined our logistics processes. We bought our own ambulance trolley and installed a footbridge, ventilator bracket, oxygen cylinder tray, and high-quality fluid and equipment poles. RBHT retrieval teams checked their equipment each morning and liaised with the Transfer Hub, who would allocate an ambulance and provide a list of patients and locations for the day. We directed referring hospitals to send referral letters to a single designated RBHT email address. We treated equipment as contaminated for the day once it had entered the red zone at any referring hospital, requiring all subsequent ambulance journeys to be undertaken in PPE. COVID-19 patients arrived through a designated entrance, and were kept separate from non-COVID areas of the hospital. Any necessary imaging was performed upon entry to the hospital. All equipment was cleaned and stored in a designated clean area of the ICU after the final retrieval of each day.

Finally, we built on our expertise in managing mechanically ventilated patients undergoing tracheostomy weaning by establishing a dedicated COVID-19 tracheostomy weaning unit at The Royal Brompton Hospital. Our bespoke pathway accepted referrals and transfers from across NWLCCN of patients appropriate for a tracheostomy or who already had one. We worked closely with surgeons, specialist respiratory physicians and physiotherapists, enabling us to share our specific expertise in this field for the mutual benefit of all patients in NWLCCN.

Conclusion

Whilst the UK may have an average of 6.6 critical care beds per 100,000 population, North West London has closer to 8 critical care beds per 100,000 population (15–20% more than the average UK network). 15 However, the unprecedented pressures experienced by NPH and the NWLCCN meant that transfer services had to undergo profound restructuring to face this crisis. Our experience has demonstrated that critical care transfers can be an effective crisis management tool for distributing regional demand in a major conurbation, where demand can show significant variation and outstrip capacity at individual sites despite extensive, city-wide capacity expansion. Longer-range retrieval programs have been utilised internationally during the COVID-19 pandemic, including high-speed rail-based transfers from Paris to Bordeaux, 16 and military-operated aero-medical retrievals from Bergamo, Italy to Germany. 17

Co-ordinated, clinician-led mutual aid and interhospital transfers were essential to North West London’s ability to cope with pandemic-induced regional critical care demand. Alongside ramping up ICU bed capacity, NWLCCN transfer service ensured unrationed, timely access to critical care for all patients who would benefit from admission. Specific innovative measures that led to the network’s success include fastidious identification and communication of critically ill patients appropriate for transfer by ICU leads, streamlining the transfer process facilitated by Surgical Site Consultants, rapid establishment of a central coordinating Transfer Hub to manage network-wide strategy and logistics of decompressing ICUs, formation of dedicated transfer teams and SOPs for COVID-19 transfers, and partnering with a digital workforce management platform to create a bespoke app to automate the scheduling and administration of transfer volunteers. NWLCCN’s established collaborative learning and governance program provided not only operational and clinical harmonisation, but also longstanding pre-pandemic working relationships with mutual familiarity and patterns of support. This enabled an unprecedented joint effort by the NWLCCN team and clinicians across all NWLCCN sites to support patients in hospitals other than their own. Our experience, both during and prior to the pandemic, is informing discussions about developing a more formalised transfer service for critical care patients across London and the UK.

Quality improvement literature has discussed potential benefits of networks over other structures, as networks have a flatter hierarchy and thus facilitate crisis learning. 18 Unlike many other critical care networks in the UK, NWLCCN is not structured around a single, large tertiary centre fed by district hospitals, but instead comprises a complex array of academic centres and large or medium-sized general hospitals. It therefore operates on a point-to-point, rather than hub-and-spoke model. This exacerbates the logistical complexities of transfers, which must deliver patients to multiple sites within a network, as opposed to a single focal receiving site. However, our experience demonstrates that with shared learning, rapid coordination, and regional innovation, critical care transfers can be successfully coordinated across such a network. This suggests that local networks may have structural advantages over national centralised structures, in being more agile and able to respond to local challenges. However, network-initiated and volunteer-based transfer services may not be sufficiently robust to cope in the face of unrelenting demand. When formalising these services in the future, one challenge will be to ensure that this does not become a limiting factor.

The COVID-19 pandemic was tremendously challenging for North West London, whose pattern of population and disease would undoubtedly have resulted in critical care demand exceeding supply at individual sites without a coordinated response. Surviving this crisis has given us a unique opportunity for learning, development and growth.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the North West London Critical Care Network strategic and operational team and importantly, all critical care and other clinical colleagues at the Network hospitals. They have all worked tirelessly to set up and organise the Hub, provide transfer teams, support referral and receiving hospital functions, and contribute to innovation and development. Much of this was in voluntary time and all of it was well beyond normal roles and working patterns, and for this we are very grateful.

We also wish to thank the London Ambulance Service and the drivers and coordinators of the independent ambulance providers - Special Ambulance Transfer Service (SATS) and Healthcare And Transport Services (HATS). We would like to give particular thanks to Gezz Van Zwanenberg for his early, invaluable work in setting up the transfer hub and to Jo Gilroy for support with coordination.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Eleanor Pett https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6206-3539

Giulia Sartori https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2867-9193

Ganesh Suntharalingam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5165-3277

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics. Clinical commissioning group population estimates (National Statistics), www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/clinicalcommissioninggroupmidyearpopulationestimates (2018, accessed 15 June 2020).

- 2.Critical Care Network North West London. CRITCON, www.londonccn.nhs.uk/managing-the-unit/capacity-escalation/critcon/ (2014, accessed 15 June 2020).

- 3.Intensive Care Society. Clinical Guidance: Assessing whether COVID-19 patients will benefit from critical care, and an objective approach to capacity challenges, www.wcctn.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/1210/COVID%5F19%5Fcare%5Fguidance%5F5may%5Fendorsed.pdf (2020, accessed 13 July 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Fanara B, Manzon C, Barbot O, et al. Recommendations for the intra- hospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care 2010; 14: R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FoëX B, Van Zwanenberg G, Handy J, et al. Guidance on: the transfer of the critically ill adult. The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/transfer_critically_ill_adult_2019.pdf (2019, accessed 15 June 2020).

- 6.Mapping the coronavirus outbreak. Graphic: Steven Bernard and Cale Tilford. Sources: ECDC; Covid Tracking Project; FT. research, www.ft.com/content/a26fbf7e-48f8-11ea-aeb3-955839e06441. (accessed 5 July 2020).

- 7.Batchelor G. Revealed the hospitals facing most pressure to meet coronavirus demand. Health Serv J, www.hsj.co.uk/quality-and-performance/revealed-the-hospitals-facing-most-pressure-to-meet-coronavirus-demand/7027354.article (2020, accessed 19 June 2020).

- 8.Epi cell, Surveillance cell and Health Intelligence Team. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. Public Health England, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/892085/disparities_review.pdf [2020, accessed 19 June 2020).

- 9.Mackintosh T. Coronavirus: The London hospital hit by a ‘tidal wave’ of patients. BBC News, 2 June, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-52812457 (2020, accessed 12 June 2020).

- 10.Association of Anaesthetists. ICU surge capacity in a busy London district general hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, https://anaesthetists.org/Home/Resources-publications/COVID-19-guidance/ICU-surge-capacity-in-a-busy-London-district-general-hospital-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic (accessed 14 June 2020).

- 11.NHS England, Redeploying your secondary care medical workforce safely. National Health Service England, 26 March, www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/Redeploying-your-secondary-care-medical-workforce-safely_26-March.pdf (2020, Accessed 14 June 2020).

- 12.Grier S, Brant G, Gould T, et al. Critical care transfer in an English critical care network: analysis of 1124 transfers delivered by an ad-hoc system. J Intensive Care Soc 2020; 21: 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Critical Care Network North West London. Transfer Course, www.londonccn.nhs.uk/training-research/transfer-training/transfer-course/ (accessed 6 July 2020).

- 14.Van Zwanenberg G, Dransfield M, Juneja R; for North West London Critical Care Network. A consensus to determine the ideal critical care transfer bag. J Intensive Care Soc 2016; 17: 332–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes A, Ferdinande P, Flaatten H, et al. The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 1647–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keohane D. France’s TGV speeds Covid-19 patients to spare hospital beds. Financial Times, 2 April, www.ft.com/content/619bd7b0-7424-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca (2020, accessed 12 June 2020).

- 17.Chang B. Inside the German military's Airbus A310 'flying hospital', which is transporting coronavirus patients from Italy to Germany. Business Insider, 1 April, www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-german-military-airbus-a-310-medevac-coronavirus-italy-germany-2020-3?r=US&IR=T (2020, accessed 13 June 2020).

- 18.Moynihan D. Learning under uncertainty: networks in crisis management. Public Admin Rev 2008; 68: 350–361. [Google Scholar]