Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has presented a unique set of psychological stressors for healthcare professionals. There is currently a dearth of literature establishing the impact amongst intensive care workers, who may be at the greatest risk. This study aimed to establish the prevalence of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder amongst a cohort of intensive care workers within the United Kingdom.

Methods

A questionnaire was designed to incorporate validated screening tools for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) anxiety (Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale, GAD-7), and post-traumatic stress disorder (Impact of Event Scale–Revised, IES-R). All intensive care workers at the Countess of Chester Hospital (UK) were eligible. Data was collected between 17th June and 8th July 2020.

Results

The majority of the 131 respondents were nurses (52.7% [69/131]) or doctors (32.8% [43/141]). Almost one-third (29.8% [39/131]) reported a significant or extreme impact of COVID-19 on their mental health. In total, 16%(21/131) had symptoms of moderate depression, 11.5%(15/131) moderately severe depression and 6.1%(8/131) severe depression. Females had significantly higher mean PHQ-9 scores than males (8.8 and 5.7 respectively, p = 0.009). Furthermore, 18.3% (24/131) had moderate anxiety with 14.5% (19/131) having severe anxiety. Mean GAD-7 scores were higher amongst females than males (8.7 and 6.3 respectively, p = 0.028). Additionally, 28.2% (37/131) reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD (IES-R ≥ 33). Despite these findings, only 3.1% (4/131) of staff accessed trust mental health support.

Conclusion

The impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers is significant and warrants specific focus and attention in order to preserve this key sector of the workforce.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, critical care, anxiety, depression

Introduction

In January 2020, the outbreak of a new coronavirus (COVID-19) was declared a public health emergency of international concern, and shortly afterwards it became a global pandemic. 1 COVID-19 presents a unique set of psychological challenges to the healthcare worker, and is the most severe pandemic since Spanish Influenza. 2 Previous experiences from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and novel influenza A (H1N1) epidemics have identified the psychological strain on healthcare workers, particularly those on the frontline, as being substantial.3,4 There is increasing recognition that the psychological impact of COVID-19 is not dissimilar. Protecting the psychological well-being of healthcare workers is essential for the long-term capacity of the health workforce. 1

A recent cross-sectional study of the general population in China, 5 found that 35.1% of respondents had symptoms of anxiety whilst 20.1% had depressive symptoms, with healthcare workers being at the highest risk of poor sleep. A similar study specifically assessing nurses and doctors in Wuhan found 22.4% had moderate depressive symptoms and 6.2% severe symptoms. 6 It is worth noting that the majority of study participants were from the Hubei Province and therefore it is unknown whether such findings are generalisable to other populations such as the United Kingdom (UK). Similarly, a multi-centre study of 906 healthcare workers in Singapore and India found 5.3% had moderate to very severe depression and 8.7% had severe to extremely severe anxiety. 7 Lai et al 8 recently assessed healthcare workers across 34 hospitals in China and found 50.4% of respondents had symptoms of depression whilst 44.6% had symptoms of anxiety. Frontline workers involved directly with diagnosis, treatment and patient care were at the highest risk of developing mental health symptoms and psychological distress.

Healthcare workers are already recognised as being a high-risk cohort in terms of adverse mental health, and life-and-death emergencies are already a major stressor for doctors. 9 This is supported by a systematic review conducted in 2019, which found the incidence of suicide amongst physicians to be higher than the general population (Standardised Mortality Rate = 1.44) with anaesthetists being a particularly high-risk group. 10 More recently, Dutheil et al 11 highlighted that determining which patients are likely to benefit from assisted ventilation compounds this stressor. Such decisions are made on a daily basis on intensive care and it is therefore not unreasonable to assume intensive care workers may be more affected than those working in other specialties. COVID-19 will undoubtedly magnify this psychological burden and it therefore warrants specific attention.

Whilst research is increasingly focusing on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers, there is currently a dearth of literature from the UK and more specifically amongst intensive care workers. The mounting challenges facing intensive care workers in the UK have not previously been seen on this scale and the psychological impact needs to be established. The main aim of this study was to establish the prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms amongst healthcare workers on an intensive care unit in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Questionnaire design

A recent review 12 identified the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), 13 Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) 14 and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) as the most commonly used tools to assess the psychological impact of COVID-19. To facilitate comparison to other studies, the PHQ-9 was chosen to screen for depression and the IES-R to assess prevalence of PTSD symptoms. To avoid overburdening respondents with too many questions, the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), 15 rather than the SAS, was used to establish anxiety levels. All three screening tools were incorporated into the study questionnaire. Demographic data including age, gender and job role were also collected. To preserve the anonymity, age brackets were used and ethnicity omitted. Participants were asked to indicate the self-perceived impact of COVID-19 on their mental health, and highlight factors that had contributed to this. Additionally, we assessed participants’ awareness of trust mental health support services. All intensive care staff were eligible except students.

Data collection

Data was collected between the 17th June and the 8th July 2020. A statement of presumed consent was included and participants were directed to read this before completing the questionnaire. Information detailing trust mental health support was also included.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS 25.0 was used for data analysis. Proportions were reported as counts (percentages). Means (standard deviation) were used for reporting parametric data. Independent t-tests compared continuous variables between male and females. One-way ANOVA was used to compare mean PHQ-9, GAD-7 or IES-R scores between job roles and age categories. A p-value of ≤0.05, two tailed, was deemed statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained through the Health Research Authority (Integrated Research Application Programme [IRAS 285114]).

Results

Demographics

In total, 131 intensive care workers completed the survey. The majority of participants were female (74.0% [97/131]). Respondents included doctors (32.8% [43/131]), intensive care unit (ICU) nurses (31.3% [41/131]), redeployed nurses (21.4% [28/131]), health care assistants (HCAs) (7.6% [10/131]), allied health professionals (AHPs) (3.1% [4/131]) and other roles including domestic and administration services (3.9% [5/131]). Age demographics were as follows: 15–24 years (3.8% [5/131]), 25–34 years (39.7% [52/131]), 35–44 years (25.2% [33/131]), 45–54 years (22.1% [29/131]), 55–64 years (7.6% [10/131]) or greater than 65 years (1.5% [2/131]). All respondents had worked on ICU within the last 3 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (26.0%) |

| Female | 97 (74.0%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

| Age (years) | |

| 15–24 | 5 (3.8%) |

| 25–34 | 52 (39.7%) |

| 35–44 | 33 (25.2%) |

| 45–54 | 29 (22.1%) |

| 55–64 | 10 (7.6%) |

| >65 | 2 (1.5%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

| Occupation | |

| ITU nurse | 41 (31.3%) |

| Redeployed nurse | 28 (21.4%) |

| HCA | 10 (7.6%) |

| AHP | 4 (3.1%) |

| Doctor | 43 (32.8%) |

| Other | 5 (3.8%) |

| Total | 131 (100%) |

Previous or current diagnosis of anxiety or depression

Approximately 1 in 10 respondents (10.7% [14/131]) reported a formal diagnosis of either anxiety or depression at the time of study participation with the majority being female (85.7% [12/14]). Additionally, 16.8% [22/131] had previously been diagnosed with anxiety or depression, 72.7% [16/22] of whom were female.

Perceived risk

Perceived risk to personal health as a result of working on intensive care was stratified as either no risk (8.4% [11/131/]), minimal (50.4% [66/131]), moderate (29.8% [39/131]) high (9.9% [13/131/]) or extreme risk (1.5% [2/131]). No males felt they were taking a high or extreme level of risk, unlike 15.5% [15/97] of females.

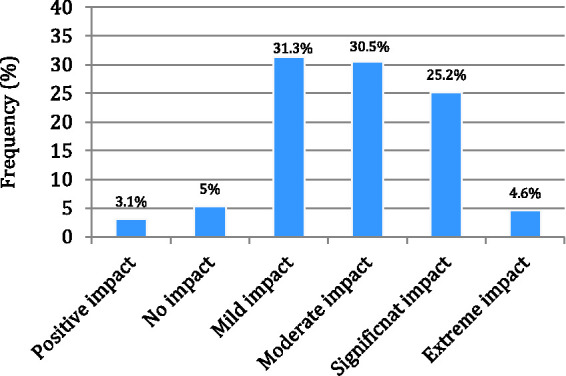

Impact of COVID-19 on mental health

Almost all respondents (91.6% [120/131]) felt that working on intensive care during the pandemic impacted negatively on their mental health. This impact was rated as mild (31.3% [41/131]), moderate (30.5% [40/131]), significant (25.2% [33/131]) or extreme (4.6% [6/131]). Interestingly, 3.1% [4/131] rated the impact as being positive with just 5.3% [7/131] reporting no impact at all (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Self-rated impact of COVID-19 on mental health.

Respondents indicated which factors had impacted most on their mental health. The most common reason was the risk of transmitting COVID-19 to family members (78.6% [103/131]) followed by being busier at work, (60.3% [79/131]), the risk of personally contracting COVID-19 (56.5% 74/131]), a change in usual working environment (51.1% [67/131]) and altered shift patterns (43.5% [57/131]).

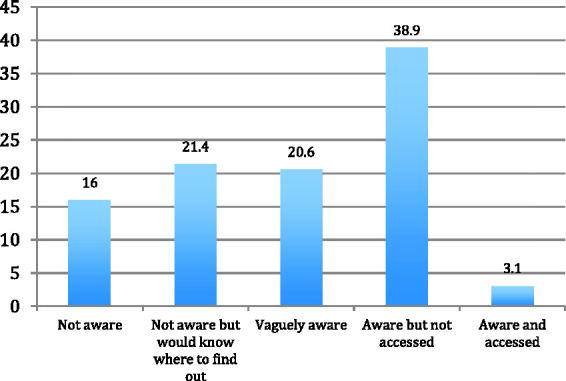

Awareness of mental health support and access to the service

In relation to trust mental health support services, respondents were either not aware of available services at all (16% [21/131]), not aware but would know where to find more information (21.4% [28/131]), vaguely aware (20.6% [27/131]), aware but had not accessed (38.9% [51/131]), or aware and had already accessed the service (3.1% [4/131]) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Awareness of mental health support within the hospital.

Depression

The PHQ-9 comprises 9 multiple choice questions. A score of 5-9 indicates mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 moderately severe depression, and 20–27 severe depression. The mean PHQ-9 score was 8.0 (SD 6.1), consistent with mild depression. In total, 29.8% [39/131] of respondents had mild depression, 16.0% [21/131] moderate depression, 11.5% [15/131] moderately severe depression and 6.1% [8/131] severe depression. The remaining 36.6% [48/131] had either none or very few symptoms of depression (Table 2). Mean PHQ-9 scores (Table 3) were significantly higher amongst females (8.8, SD 5.9) compared to males (5.7, SD 5.9) [p = 0.009, t = 2.636, df 129). Comparing job roles, HCAs scored the highest (mean 10.6, SD 7.7), followed by ICU nurses (mean 9.1, SD 5.5), redeployed nurses (mean 8.8, SD 6.2), AHPs (mean 7.8, SD 9.4) and finally doctors (mean 5.8, SD 5.3). It is worth noting that HCAs (n = 10) and AHPs (n = 4) had relatively smaller sample sizes in comparison. Differences in mean PHQ-9 scores between job roles were not statistically significant. The highest mean PHQ-9 score was seen in those aged 15–24 years (mean 9.6, SD 5.3), followed by 25–34 years (mean 8.6, SD 5.9). In contrast, the lowest mean PHQ-9 score was found in 55–64 year olds (mean 5.7, SD 4.3) although differences between age groups did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

PHQ-9, GAD-7 and IES-R categories between gender and occupation.

|

Gender |

Occupation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | ITU nurse | Redeployed nurse | HCA | AHP | Doctor | Other | |

| Severity category | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| PHQ-9, depressive symptoms | |||||||||

| None/minimal (0–4) | 48 (36.6%) | 19 (55.9%) | 29 (29.9%) | 9 (22%) | 9 (32.1%) | 3 (30.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 22 (51.2%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Mild (5–9) | 39 (29.8%) | 11 (32.4%) | 28 (28.9%) | 15 (36.6%) | 7 (25.0%) | 2 (20.0% | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (34.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Moderate (10–14) | 21 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (21.6%) | 9 (22.0%) | 6 (21.4%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 2 (4.7%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 15 (11.5% | 3 (8.8%) | 12 (12.4%) | 6 (14.6%) | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (7.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Severe (20–27) | 8 (6.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | 7 (7.2%) | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (10.7%) | 1(10%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| GAD-7, anxiety | |||||||||

| None/minimal (0–4) | 38 (29.0%) | 16 (47.1%) | 22 (22.7%) | 9 (22.0%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 18 (41.9%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Mild (5–9) | 50 (38.2%) | 11 (32.4%) | 39 (40.2%) | 13 (31.7%) | 14 (50.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 16 (37.2%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Moderate (10–14) | 24 (18.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 21 (21.6%) | 12 (29.3%) | 5 (17.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 6 (14.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Severe (>15) | 19 (14.5%) | 4 (11.8%) | 15 (15.5%) | 7 (17.1%) | 4 (14.3%) | 4 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (7.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| IES-R, distress | |||||||||

| None/minimal (0–11) | 37 (28.2%) | 13 (38.20%) | 24 (24.7%) | 8 (19.5%) | 6 (21.4%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 19 (44.19%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Suggestive of PTSD (12–32) | 57 (43.5%) | 16(47.1%) | 41 (42.3%) | 17 (41.5%) | 12 (42.9%) | 5 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 18 (41.86%) | 3 (60.0% |

| Consistent with PTSD (≥33) | 37 (28.2%) | 5 (14.7%) | 32 (33.0%) | 16 (39.0%) | 10 (35.71%) | 4 (40.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 6 (13.95%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Table 3.

Mean PHQ-0, GAD-7 and IES-R with comparisons between gender and job role.

|

Gender |

Occupation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | MaleMean (SD) | FemaleMean (SD) | ITU nurseMean (SD) | Redeployed nurseMean (SD) | HCAMean (SD) | AHPMean (SD) | DoctorMean (SD) | OtherMean (SD) | |

| Scale | |||||||||

| PHQ-9 | 8.0 (6.1) | 5.7 (6.0) | 8.8 (5.9) | 9.1 (5.5) | 8.8 (6.2) | 10.6 (7.7) | 7.8 (9.4) | 5.8 (5.3) | 8.0 (8.0) |

| GAD-7 | 8.1 (5.5) | 6.3 (5.5) | 8.7 (5.4) | 9.4 (5.7) | 8.2 (4.7) | 11.4 (6.2) | 5.5 (6.8) | 4.5 (5.1) | 5.6 (6.6) |

| IES-R | 23.0 (17.8) | 18.0 (17.0) | 24.7 (17.8) | 27.6 (17.7) | 25.4 (18.6) | 27.8 (14.2) | 23.3 (25.8) | 17.1 (17.1) | 11.6 (3.8) |

Anxiety

The GAD-7 comprises 7 multiple choice questions. A score of 5–9 indicates mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety and ≥15 severe anxiety. The mean GAD-7 score was 8.1 (SD 5.5), correlating with mild anxiety. In total, 38.2% [50/131] of respondents had mild anxiety, 18.3% [24/131] moderate anxiety and 14.5% [19/131] severe anxiety. The remaining 29% [38/131] had either none or very few symptoms of anxiety (Table 2). Mean GAD-7 scores (See Table 3) were significantly higher amongst females (8.7, SD 5.5) compared to males (mean 6.3, SD 5.5, p-value = 0.028, t = 2.23. df 129). Comparing job roles, HCAs scored the highest (mean 11.4, SD 6.2), followed by ICU nurses (mean 9.4, SD 5.7), redeployed nurses (mean 8.2, SD 4.7), doctors (mean 6.5, SD 5.1) and finally AHPs (mean 5.5, SD 6.8). Differences in mean GAD-7 scores between job roles were not statistically significant. The age group with the highest mean GAD-7 score was the 15–24 year olds (mean 11.4, SD 2.8), followed by those aged 25–34 years (mean 8.7, SD 5.6). In contrast, the lowest mean GAD-7 score was seen amongst those aged 55–64 years (mean 5.4, SD 3.6). Differences in the mean GAD-7 score between age groups did not reach statistical significance.

PTSD

The IES-R comprises a 22-item scale with a maximum score of 88. Working on intensive care during the Covid-19 pandemic was regarded as the stressful life event. A score of 12–32 is suggestive of PTSD whilst ≥33 represents the best cut-off for a probable diagnosis of PTSD but would typically be used in conjunction with a clinical assessment to establish a definitive diagnosis. In total, almost a third of respondents (28.2% [37/131]) scored ≥33 (Table 2). The mean IES-R score across all participants was 23.0 (SD 17.8) and was higher amongst females (mean 24.7, SD 17.9) compared to males (mean 18.0, SD 17.0), although not statistically significant (p = 0.057, t = 1.92, df 129) (Table 3). Comparing job roles, HCAs scored the highest (mean 27.8, SD 14.2), followed by ICU nurses (mean 27.6, SD 17.7), redeployed nurses (mean 25.4, SD 18.6), AHPs (mean 23.3, SD 25.8) and finally doctors (mean 17.1, SD 17.1). Differences in mean IES-R scores between job roles were not statistically significant. Those aged 15–24 years had the highest mean IES-R score (mean 33.4, SD 19.9), followed by those aged 25–34 years (mean 24.4, SD 18.7). The lowest mean IES-R score was amongst those aged >65 years (mean 15.0, SD 18.4). There was no statistically significant difference between mean IES-R score and age category.

Discussion

COVID-19 is likely to have had a significant adverse impact on the psychological well-being of intensive care workers with almost one-third (29.8% [39/131]) reporting a significant or extreme impact on their mental health. The most commonly cited reasons included the risk of transmitting COVID-19 to family members, and the risk of personally contracting it. Given that COVID-19 is highly transmissible 16 and potentially fatal, 17 this is understandable. Being unable to socialise or living apart from family were other underlying factors. Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), especially early in the pandemic, may have further contributed to healthcare workers’ concerns. 18

Our study indicates 27.5% [36/131] of intensive care workers had symptoms of moderate or moderately severe depression with 6.1% [8/131] having severe depression. These results are comparable to a study of nurses and doctors working in Wuhan that found 22.4% had moderate depressive symptoms and 6.2% severe symptoms. 6 A study of healthcare workers in China 8 found 18% of those working ‘on the frontline’ had at least moderate depression; less than the 33.6% [44/131] in our study. A multi-centre study in Singapore and India found only 5.3% of healthcare workers had moderate or severe depression. 7 However, this study used a different screening tool, limiting direct comparisons. When drawing parallels to the UK population, data demonstrating the typical distribution of PHQ-9 responses are limited, but one study in Germany reported 5.6% of the general population had at least moderate symptoms of depression. 19 Clearly this is lower than the 33.6% [44/131] identified in our study. Similarly, a social study assessing the impact of COVID-19 on the UK population 20 reported a mean PHQ-9 score of 5.8; less than the 8.0 identified in our study, during the same period. The mean PHQ-9 score of females in our study was significantly higher than males (8.8 vs. 5.7). Both are higher than would be expected for the general population which Kocalevent et al 19 reported as being 2.7 for males and 3.1 for females. Reasons for this are not fully understood but are in keeping with a recent systematic review 21 and reflect the already established gender gap for anxiety and depression. 22 Males may also be less likely to recognise or report symptoms of mental health disorders. Younger age groups in our study had higher PHQ-9 scores, which was surprising given that older people are at greater risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. Whilst this finding may relate to less clinical experience, it perhaps reflects changing societal views on mental health with younger generations more willing to admit they are struggling.

Reflecting on anxiety levels amongst intensive care workers, 18.3% [24/131] had symptoms of moderate anxiety whilst 14.5% [19/131] had severe anxiety. These figures are higher than the findings of Lai et al 8 who found 9.1% of ‘frontline’ healthcare workers had moderate anxiety and 6.8% had severe anxiety with a median GAD-7 score of 5.0. In contrast, the mean GAD-7 score from our cohort was 8.1 suggesting that intensive care workers may be at greater risk compared to other healthcare workers. Normative GAD-7 data from Germany 23 estimates that 5% of people have at least moderate anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10); lower than the 32.8% found in our study. The on-going social study within the UK 20 reports the mean GAD-7 score in the general population as 7.4 for the same time period as our study. Additionally, females in our study experienced significantly higher GAD-7 scores than their male counterparts (8.7 vs. 6.3). Those aged 15-34 years had the highest mean GAD-7 scores, in keeping with a study of the general population in China which found younger people are more likely to have generalised anxiety disorder. 5

One of the most striking findings of our study was the mean IES-R score of 23.0 which is higher than the mean of 8.3 described by Chew et al 7 amongst healthcare workers in Singapore and India. This difference suggests that, when compared to general healthcare workers, intensive care workers may carry the greatest risk of adverse psychological morbidity. A large cross-sectional study in China found that 53.8% of the general population had an IES-R score consistent with a probable diagnosis PTSD (≥33), significantly higher than the 28.2% amongst our intensive care workers. However, this study was conducted earlier in the pandemic when there was less understanding about the disease. Importantly, the true scale of PTSD may not be clear until further down the line when more healthcare workers may experience troublesome symptoms.

Only 3.1% [4/131] of participants accessed the trust well-being support services, which is surprising given the high prevalence of anxiety and depression identified. We found that 58% [76/131] of participants were either unaware or only vaguely aware of support available, therefore it is important that services are clearly communicated to all staff. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some staff would rather be booked into a mandatory one-off appointment with a psychologist whereas others would prefer group sessions.

To mitigate the psychological burden of COVID-19, a multi-faceted approach is required. Possible solutions include greater provision of psychological support, with mandatory appointments improving identification of those at greatest risk. Although not ideal, this could be via telepsychiatry in line with social distancing guidance. 24 To reduce barriers in accessing support, appointments should be made available outside of normal working hours. Support should focus on organisational factors with a broader goal of developing a culture of improved individual coping strategies. 25 Promptly identifying and addressing mental health issues will help reduce the unwanted social, psychological, and economic burden of the disease.26,27 Other options include establishing a peer-support system 28 or development of online mental health services for early screening and interventions.29,30 Albott et al 31 advocate a ‘Battle buddy’ programme, whereby peers are assigned to support another worker with a similar level of experience and responsibility. Some suggestions highlighted by our study participants include relaxing of PPE in COVID-free zones of intensive care, ensuring staff are familiar with their working environment, encouraging the taking of annual leave and provision of adequate ‘rest days’. When workload is lower than usual, staff could be encouraged to take time away from the ward as this would inevitably improve morale.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature demonstrates an association between anxiety, depression, PTSD and COVID-19 but it is of course difficult to make causal inferences. However, a UK-based cross-sectional study of 171 intensive care workers conducted in 2018, 32 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, found 16% of staff had ‘clinically significant levels of anxiety’ whilst 8% had ‘clinically significant levels of depression’. These levels are much lower than those in our study although a different screening tool was used, namely a PHQ-4, 33 limiting direct comparisons. It is also worth noting the relatively small sample size of the HCAs and AHPs in comparison to doctors and nurses and therefore limited conclusions can be drawn about these sub-groups. Finally, our study lacks longitudinal follow-up, which would be useful to establish whether the levels of anxiety and depression amongst ICU workers will be sustained or not. Nevertheless, the study has strengths given that to the best of our knowledge it is the only study specifically assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers.

In terms of future work, a collaborative UK wide study of the mental health sequelae of COVID-19 would be beneficial. Incorporation of data from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups would be invaluable, with the multi-centre study design facilitating easier preservation of anonymity amongst sub-groups. Furthermore, exploring the psychological impact amongst healthcare workers outside of intensive care would be useful. Maunders et al 34 found that during the 2003 SARS pandemic, intensive care workers tended to be less affected by burnout than workers from other hospital departments and it is unclear as to whether or not this would hold true within the UK.

In summary, the psychological well-being of intensive care workers is likely to have been adversely affected by the pandemic. Levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD appear to be greater in intensive care workers than other healthcare workers, as well as the general population. Staff are working in exceptionally difficult conditions and are likely to be at their stress limit. 35 We echo the findings of a recent review 36 suggesting healthcare systems are currently ill-prepared to cope with the psychological impact of COVID-19. In light of this and in the face of a ‘second wave’ of COVID-19, we advocate specific attention needs to be paid to support this group. Acknowledging the mounting psychological burden and establishing the scale of the problem are the first steps towards achieving this.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inc-10.1177_1751143720983182 for Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers: A single-centre cross-sectional UK-based study by Natasha Dykes, Oliver Johnson and Peter Bamford in Journal of the Intensive Care Society

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the healthcare professionals who participated in this study and acknowledge their invaluable contribution to patients on the intensive care unit at the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Oliver Johnson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3161-1053

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mentalhealth-considerations.pdf (2020, accessed 9 May 2020).

- 2.Morens DM, Daszak P, Taubenberger JK. Escaping Pandora's box – another novel coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1293–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185: 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, et al. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the a/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Zhao N. Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry 2020; 51: 102052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88: 559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutheil F, Trousselard M, Perrier C, et al. Urinary interleukin-8 is a biomarker of stress in emergency physicians, especially with advancing age – the JOBSTRESS* randomized trial. PloS One 2013; 8: e71658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2019; 14: e0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutheil F, Mondillon L, Navel V. PTSD as the second tsunami of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic. Psychol Med 2020; 33: 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohlken J, Schomig F, Lemke MR, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers – a short current review. Psychiatr Prax 2020; 47: 190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss DS. The impact of event scale: revised. In: Wilson JP, Tang CS-K. (eds) Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2007, pp.219–238. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang W, Tang J, Wei F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan-Yeung M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health 2004; 10: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35: 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.https://www.covidsocialstudy.org/ (2020, accessed 12 August 2020).

- 21.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88: 901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015; 40: 219–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008; 46: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah K, Chaudhari G, Kamrai D, et al. How essential is to focus on physician's health and burnout in coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? Cureus 2020; 12: e7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maunder RG, Leszcz M, Savage D, et al. Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza: an evidence-based approach to mitigating the stress experienced by healthcare workers. Can J Public Health 2008; 99: 486–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci 2018; 8: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah K, Kamrai D, Mekala H, et al. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus 2020; 12: e7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banerjee D. The COVID-19 outbreak: crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 50: 102014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Rethinking online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 50: 102015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zandifar A, Badrfam R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 51: 101990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, et al. Battle buddies: rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg 2020; 131(1): 43--54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Colville GA, Dawson D, Rabinthiran S, et al. A survey of moral distress in staff working in intensive care in the UK. J Intensive Care Soc 2019; 20: 196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009; 50: 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 1924–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JD, et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res 2020; 288: 112972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaka A, Shamloo SE, Fiorente P, et al. COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment: a call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J Health Psychol 2020; 25: 883–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inc-10.1177_1751143720983182 for Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers: A single-centre cross-sectional UK-based study by Natasha Dykes, Oliver Johnson and Peter Bamford in Journal of the Intensive Care Society