Abstract

Introduction

Breathlessness is debilitating and increases in prevalence with age, with people progressively reducing their everyday activities to ‘self-manage’ it. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of breathlessness on function in terms of activities that have been reduced or ceased (‘compromised’) in older men.

Methods

A cross-sectional postal survey of Swedish 73-year-old man in the VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease study self-reporting on demographics, breathlessness (modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale, Dyspnoea-12, Multidimensional Dyspnea Scale) and its duration, anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), performance status (WHO Performance Status), everyday activities reduced/ceased and exertion.

Results

148/828 (17.9%) respondents reported breathlessness (mMRC >2), of whom 51.9% had reduced/ceased activities compared with 9.6% who did not. Physical activity was the most common activity reduced/ceased (48.0%) followed by sexual activity (41.2%) and social activities (37.8%). Of 16.0% of respondents with mMRC 3–4 talking on the phone was affected compared with only 2.9% of respondents with mMRC 2. Worsening breathlessness was associated with increasingly sedentary lifestyles and more limited function, those reporting reduced/ceased activities had an associated increase in reporting anxiety and depression. In adjusted analyses, breathlessness was associated with increased likelihood of activities being ceased overall as well as physical and sexual activities being affected separately.

Conclusion

Worsening breathlessness was associated with decreasing levels of self-reported physical activity, sexual activity and function. Overall, the study showed that people with persisting breathlessness modify their lifestyle to avoid it by reducing or ceasing a range of activities, seeking to minimise their exposure to the symptom.

Keywords: perception of asthma/breathlessness, respiratory measurement

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

People living with persisting breathlessness progressively reduce their everyday activities. A more nuanced understanding of the impact is needed to help inform older people’s mastery of the symptom to optimise their independent living and functioning.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this cohort of elderly men, worsening persisting breathlessness was associated with increased likelihood of everyday activities being progressively reduced or ceased.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

This study highlights the full breadth of impact of persisting breathlessness with social, sexual and physical functioning progressively diminishing as persisting breathlessness worsens. Delineating the type and degree to which everyday activities have been compromised is critical for providing adequate clinical care for this population.

Introduction

Breathlessness is one of the most prevalent, debilitating symptoms in chronic, progressive conditions,1 with increasing prevalence in advanced disease and age.2 Persisting breathlessness3 4 detrimentally affects people’s quality of life, including their physical, mental, social and sexual well-being.5–8 Everyday activities are also affected, with people forgoing activities and everyday interactions as their persisting breathlessness worsens.9 The symptom also associates with increased health service utilisation and earlier death.10 11

Persisting breathlessness is insidious, and over time, results in marked disability as people progressively reduce their day-to-day and social activities to ‘self-manage’ it.9 12 This often leads to a downward spiral of worsening breathlessness, with physical deconditioning which, in turn, worsens the person’s breathlessness. Consequently, people’s impaired function and perceived inability to do their usual everyday activities increases burden on their caregivers13 and increases contact with health services, including primary care, emergency departments and hospitalisations.14 This is particularly the case for older people who are often at an increased risk of declining physical activity.15 Given that chronic symptom burden can be amplified in the older population,16 it is important to understand the range of activities that are affected by worsening breathlessness in this population.17 A more nuanced understanding of the impact on everyday life will help inform the development of support mechanisms to improve older people’s mastery of the symptom and ultimately optimise their independent living and functioning.18

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of breathlessness on function in terms of activities that have been reduced or ceased (‘compromised’) in older men.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional study of 73-year-old men in the county of Blekinge, Sweden taking part in the VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (VASCOL) study.19 The VASCOL study is a longitudinal cohort study; the details have been presented elsewhere.19

Study participants were recruited from a screening campaign of aortic aneurysm offered to all men aged 65 (n=1900) in the county of Blekinge, Sweden in 2010–2011. All men invited to the screening were also invited to participate in the VASCOL study, of which a total of 1302 agreed to participate (wave 1; baseline). Data for the current study were collected at follow-up in 2019 using a postal survey that was sent out to 1193 participants who were still alive and who had a known address (wave 2; follow-up). The postal survey was completed by 907 participants. Eligible for inclusion in the current analysis were complete responses on self-reported everyday activities reduced or ceased (n=828) as well as self-reported breathlessness and its duration, anxiety/depression, performance status. No missing data were imputed.

The associations between breathlessness and activities compromised were analysed using data collected at this single time point follow-up (wave 2) only as this was the first time that questions about breathlessness were asked.

Patient and public involvement

Ten pilot participants of similar age to the VASCOL study participants provided critical feedback on the length, layout and linguistics aspects of the wave two survey. The full details have been presented elsewhere.19

Data collection and key measures

Demographics (marital status; education level) were collected at baseline (wave 1). Self-reported data collected at follow-up (wave 2) included height, weight, smoking history, conditions; breathlessness (modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale20; Dyspnoea-12 (D-12)21; Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile (MDP)22), anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)23), performance status (WHO Performance Status (WHOPS),24 use of walking aids (yes/no) and long-term oxygen therapy for breathlessness (yes/no), number of years with breathing problems (years); everyday activities reduced/ceased due to breathlessness (multiple item question) and self-rated exertion (multiple item question). Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg)/height (m).

Breathlessness was assessed using the mMRC breathlessness scale20 and the validated Swedish postal versions of the D-12 and MDP.21 22 The mMRC20 is a five-point ordinal scale (0–4) correlating level of exertion before it is limited by breathlessness. Higher scores reflect higher functional impairment due to breathlessness. Breathlessness was defined as an mMRC score of ≥2 for the current analysis. The D-1221 is a 12-item questionnaire with descriptors of breathlessness across two domains: physical (items 1–7) and affective (items 8–12); scores range from 0 to 3 for each question, giving a total score range 0–36. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the D-12 total score is 2.83 (95% CI 1.99 to 3.66).25 The MDP22 is an 11-item questionnaire with descriptors of breathlessness across three domains: A1 unpleasantness (score range 0–10), immediate perception (score range 0–60) and emotional response (score range 0–50). The MCID for the A1 component has been reported as 0.82 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.08).25 Higher scores of all breathlessness measurements in the present study indicate worse breathlessness.

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the HADS, a validated 14-item screening tool that assesses each symptom separately (scores each 0–21).23 Higher scores indicate greater likelihood of the symptom being present. The MCID for HADS has been reported as 1.32 for the anxiety score, 1.4 for the depression score and 1.17 for the total score.26

Performance status was assessed using the WHOPS ordinal scale (0–4),24 with higher scores reflecting poorer function. This study merged grades 2–4 into a single category for the analysis.

Assessment for the mMRC, D-12, MDP, HADS and WHOPS focused on the period ‘during the last 2 weeks’.

Respondents were able to select from a list of everyday activities they have reduced or ceased due to breathlessness. These included: physical (eg, walking, carrying things, exercise), social contact, clubs or associations, telephone conversations, sexual activity and ‘other’. There were three possible responses for each type of activity: 1 = ‘unchanged’; 2 = ‘more rarely’ and 3 = ‘given up completely’ and, given small numbers, the latter two were combined and recoded to ‘yes’.

Exertion was self-rated as: 1 = ‘sedentary’ (walk or cycle less than 2 hours a week); 2 = ‘moderate exercise’ (moderate physical activities for at least 4 hours a week including, for example, walking, regular gardening or bowling); 3 = ‘moderate but regular exercise’ (engage in activities for at least 2–3 hours a week on average and exercise regularly 1–2 times a week for at least 30 min at a time with activities that causes more exertion such as sports or more strenuous gardening); 4 = ‘frequent exercise’ (engage in strenuous exercise and sports regularly/several times a week, at least three times per week and at least 30 min at a time, including competitive sports).27

Statistical analysis

The population was described and comparisons between those who identified and those who did not identify reduced/ceased activities were conducted using t tests for continuous variables, χ2 or Kruskal-Wallis tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to explore the impact of known confounders on the model exploring the factors likely to influence participation levels in everyday activities. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows V.26.0. (SPSS Chicago, Illinois, 2011).

Results

Participants

Of the 1193 men invited to the study, 828 (69.4%) responded with complete data for all relevant fields. (table 1) Respondents were aged 73, with 520 (62.8%) educated above elementary school, 658 (79.5%) lived with a partner and 566 (68.4%) reported being overweight or obese (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical description of those who have responded to activities reduced/ceased and mMRC (n=828)

| Activities reduced/ceased | P value | ||||

| Yes (n=162) | No (n=666) | ||||

| Age follow-up (mean (SD)) | 73.27 (0.72) | 73.21 (0.67) | 0.330 | ||

| Marital status* | Living separately/living alone/divorced/widowed | 33 (22.3) | 78 (12.6) | 0.003 | |

| Married/partnered | 115 (77.7) | 543 (87.4) | |||

| Education* | Elementary | 63 (42.3) | 193 (30.8) | 0.040 | |

| Upper secondary | 26 (17.5) | 150 (23.9) | |||

| Professional school | 32 (21.5) | 136 (21.7) | |||

| University | 28 (18.8) | 148 (23.6) | |||

| Smoking status | Current smoker | 10 (6.2) | 40 (6.0) | 0.61 | |

| Former smoker | 99 (61.1) | 388 (58.3) | |||

| Never smoked | 49 (30.2) | 232 (34.8) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean (SD) | 28.83 (4.7) | 26.64 (3.4) | <0.001 | |

| WHO categories n (%) |

Underweight/healthy weight | 28 (17.6) | 213 (32.9) | <0.001 | |

| Overweight | 73 (45.9) | 342 (52.8) | |||

| Obese | 58 (36.5) | 93 (14.4) | |||

| Duration of breathing problems (years) | Mean (SD) | 6.66 (9.3) | 3.59 (9.8) | 0.020 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS) scores† | Anxiety summary score (0–21) | 5.25 (4.5) | 2.98 (3.0) | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety grouped n (%) |

Normal (0–7) | 111 (71.6) | 585 (91.0) | <0.001 | |

| Borderline (8–10) | 16 (10.3) | 42 (6.5) | |||

| Abnormal (11–21) | 28 (18.1) | 16 (2.5) | |||

| Depression summary score (0–21) | 4.75 (3.8) | 2.56 (2.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Depression grouped n (%) |

Normal (0–7) | 117 (74.5) | 614 (95.2) | <0.001 | |

| Borderline (8–10) | 25 (15.9) | 24 (3.7) | |||

| Abnormal (11–21) | 15 (9.6) | 7 (1.1) | |||

| WHO Performance Status;‡ n (%) |

Fully active; no performance restrictions. | 52 (32.7) | 536 (81.5) | <0.001 | |

| Strenuous physical activity restricted; fully ambulatory and able to carry out light work. | 79 (49.7) | 102 (15.5) | |||

| Capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about >50% of waking hours/capable of only limited self-care; confined to bed or chair >50% of waking hours/completely disabled; cannot carry out any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair. | 28 (17.6) | 20 (3.0) | |||

| Exertion; n (%) | Sedentary | 29 (17.9) | 34 (5.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate exercise | 104 (64.2) | 411 (61.0) | |||

| Moderate but regular exercise | 25 (15.4) | 190 (28.2) | |||

| Frequent exercise | 4 (2.5) | 39 (5.8) | |||

| Additional therapies/supports | Use walking aids; n (%) | 11 (7.3) | 2 (0.3) | <0.001 | |

| Use oxygen therapy; n (%) | 7 (4.6) | 4 (0.6) | <0.001 | ||

| modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale; n (%) | 0 | 45 (27.8) | 528 (79.3) | <0.001 | |

| 1 | 33 (20.4) | 74 (11.1) | |||

| 2 | 30 (18.5) | 39 (5.9) | |||

| 3 | 26 (16.1) | 17 (2.6) | |||

| 4 | 28 (17.3) | 8 (1.2) | |||

| Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile (MDP)† | Total§ | 14.88 (22.4) | 1.64 (5.4) | <0.001 | |

| Perception¶ | 8.20 (11.0) | 1.08 (2.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Emotional** | 5.40 (8.0) | 0.83 (3.2) | <0.001 | ||

| A1†† | 2.05 (2.1) | 0.35 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

| MDP—A1 by group score | 0 | 479 (77.6) | 47 (30.5) | <0.001 | |

| 1 | 88 (14.3) | 25 (16.2) | |||

| 2 | 28 (4.5) | 32 (20.8) | |||

| 3 | 16 (2.6) | 24 (15.6) | |||

| 4–8 | 6 (1.0) | 26 (16.9) | |||

| Dyspnoea-12 (D-12)‡‡ |

Total Score | 5.61 (7.0) | 0.61 (2.0) | <0.001 | |

| Total score with imputation (according to Yorke)§§ | 5.63 (6.9) | 0.60 (2.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Physical subdomain score¶¶ | 3.54 (4.1) | 0.46 (1.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Affect subdomain score*** | 2.07 (3.2) | 0.15 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

*Activities (reduced/ceased) include: physical activities, social contacts, associations, talking on the phone, sexual activities, other;~baseline data (not collected at Wave 2).

†Respondents’ numbers reflect complete data for that measure.

‡grades 2–4 merged into a single category.

§65.6% scored 0 for MDP Total.

¶61.4% scored 0 for MDP Perception.

**76.1% scored 0 for MDP Emotional.

††68.2% scored 0 for MDP-A1.

‡‡71.7%scored 0 for D-12 total score.

§§71.4% scored 0 for D-12 total score with imputation.

¶¶71.6% scored 0 for D-12 Physical.

***86.4% scored 0 for D-12 Affect.

Breathlessness of mMRC >2 was reported by 148/828 (17.9%) of respondents (table 1); and by 84/162 (51.9%) of respondents who identified they had reduced/ceased activities compared with 64/666 (9.6%) who did not (table 1). Those reporting activities reduced/ceased experienced breathing problems for a median of 4.0 years (IQR 2.0–7.0) compared with a median 0 years (IQR 0.0 to 3.0) for those not reporting any activities reduced/ceased (table 1)

Higher anxiety scores (HADS 11–21) were reported by 44/828 (5.3%) respondents of whom 22/44 (52.4%) reported breathlessness of mMRC >2 (table 2). Higher depression scores (HADS 11–21) were reported by 22/828 (2.7%) respondents of whom 9/22 (22.2%) reported breathlessness of mMRC >2. Of those reporting activities reduced/ceased (n=162), 28 (17.3%) reported higher anxiety scores and 15 (9.3%) reported higher depression scores, compared with 16 (2.4%) and 7 (1.1%) of those whose activities were not affected (n=666) (table 1).

Table 2.

Clinical description of respondents including self-reported activities reduced/ceased by mMRC (n=828)

| mMRC | P value | |||||||

| 0 (n=573) | 1 (n=107) | 2 (n=69) | 3 (n=43) | 4 (n=36) | ||||

| Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)* | Anxiety | Normal (0–7) | 505 (91.7) | 86 (81.9) | 54 (79.4) | 31 (72.1) | 20 (64.5) | <0.001 |

| Borderline (8–10) | 33 (6.0) | 10 (9.5) | 7 (10.3) | 5 (11.6) | 3 (9.7) | |||

| Abnormal (11–21) | 13 (2.4) | 9 (8.6) | 7 (10.3) | 7 (16.3) | 8 (25.8) | |||

| Depression | Normal (0–7) | 529 (95.5) | 91 (86.7) | 58 (84.1) | 32 (80.0) | 21 (61.8) | <0.001 | |

| Borderline (8–10) | 17 (3.1) | 9 (8.6) | 9 (13.0) | 5 (12.5) | 9 (26.5) | |||

| Abnormal (11–21) | 8 (1.4) | 5 (4.8) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (11.8) | |||

| Body mass index (BMI) (WHO categories) | Underweight/healthy weight | 196 (35.1) | 22 (21.4) | 14 (20.6) | 5 (11.6) | 4 (11.4) | <0.001 | |

| Overweight | 297 (53.2) | 56 (54.4) | 29 (42.7) | 23 (53.5) | 10 (28.6) | |||

| Obese | 65 (11.7) | 25 (24.3) | 25 (36.8) | 15 (34.9) | 21 (60.0) | |||

| WHO Performance Status | Fully active; no performance restrictions. | 474 (83.8) | 66 (62.3) | 29 (42.0) | 11 (26.2) | 8 (23.5) | <0.001 | |

| Strenuous physical activity restricted; fully ambulatory and able to carry out light work. | 74 (13.1) | 35 (33.1) | 34 (49.3) | 22 (52.4) | 16 (47.1) | |||

| More limited than capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about >50% of waking hours. | 18 (3.2) | 5 (4.7) | 6 (8.7) | 9 (21.4) | 10 (29.4) | |||

| Self-rated exertion n (%) |

Sedentary | 21 (3.7) | 11 (10.5 | 9 (13.4) | 12 (27.9) | 9 (25.7) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate exercise | 329 (58.7) | 71 (67.6) | 47 (70.2) | 24 (55.8) | 22 (62.9) | |||

| Moderate but regular exercise | 173 (30.8) | 23 (21.9) | 8 (11.9) | 6 (14.0) | 3 (8.6) | |||

| Frequent exercise | 38 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.9) | |||

| Additional therapies/supports | Use walking aids; n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (3.2) | <0.001 | |

| Use oxygen therapy; n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (12.5) | <0.001 | ||

| Activities reduced/ceased | Physical activities | 19 (3.3) | 27 (25.5) | 23 (33.3) | 21 (48.8) | 27 (75.0) | <0.001 | |

| Social contacts | 12 (2.1) | 7 (6.6) | 4 (5.8) | 11 (25.6) | 12 (33.3) | <0.001 | ||

| Associations | 18 (3.1) | 11 (10.4) | 5 (7.4) | 12 (27.9) | 12 (34.3) | <0.001 | ||

| Talking on the phone | 8 (1.4) | 8 (7.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (16.3) | 6 (16.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Sexual activities | 37 (6.5) | 24 (22.8) | 17 (25.0) | 22 (51.2) | 22 (61.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 5 (0.9) | 2 (2.5) | 6 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (20.0) | <0.001 | ||

*Respondents’ numbers reflect complete data for that measure.

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council.

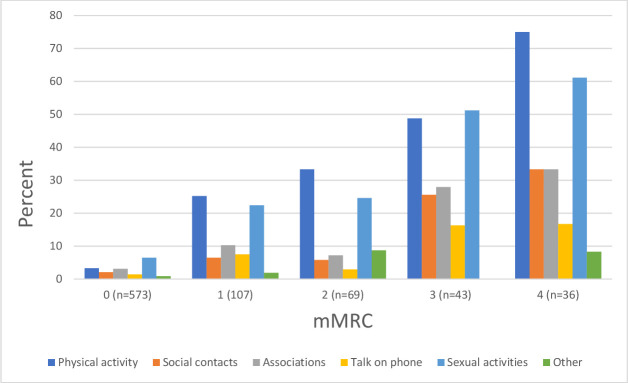

Activities reduced/ceased

Activities reduced/ceased were reported by 162 (19.6%) of respondents (table 1) and its prevalence increased with measures of breathlessness. For respondents reporting breathlessness of mMRC ≥2, physical activity was the most common activity reduced/ceased (48.0%) followed by sexual activity (41.2%) (table 2). Social activities (social contacts; associations) were the third most commonly activity reduced/ceased (37.8%). For 16.0% of respondents with mMRC 3–4, talking on the phone was identified as being affected compared with only 2.9% of respondents with mMRC 2 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Activities reduced/ceased by modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale (n=828).

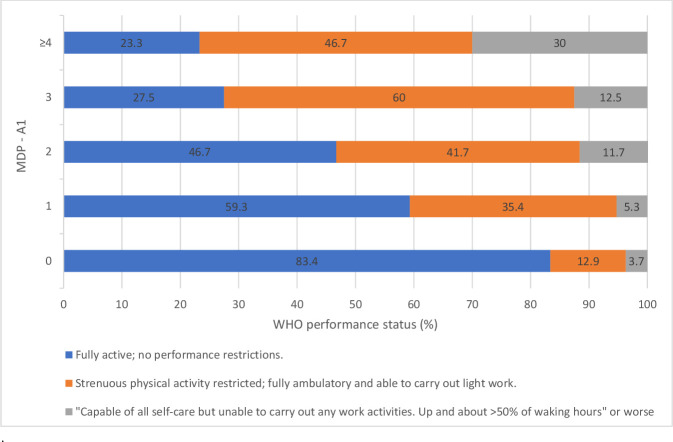

A similar pattern was seen when using MDP A1 for breathlessness although the group with the highest (worst) MDP A1 scores had more reduced/ceased sexual and social activities (figure 2). The same relationships were seen when breathlessness was evaluated using D-12.

Figure 2.

WHO performance status by Multi-Dimensional Dyspnea Profile (MDP)—A1 unpleasantness (n=771).

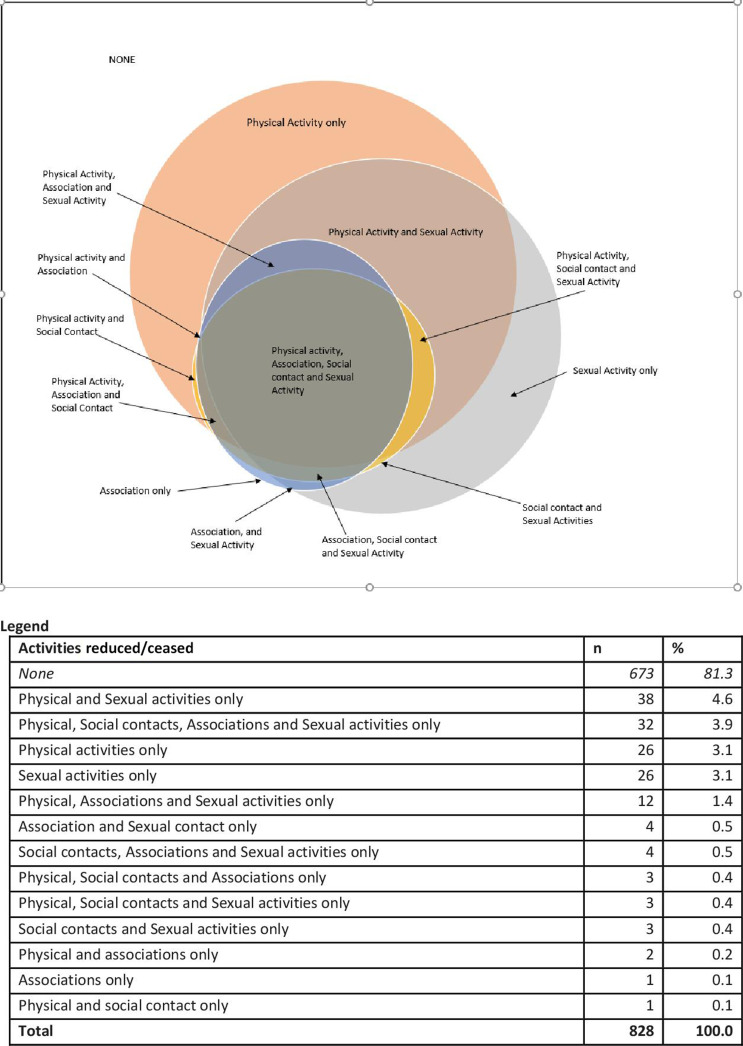

Activities most often reduced/ceased for people reporting breathlessness include physical or sexual activity alone or in combination with each other as well as in combination with social activities (social contact; associations) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Combinations of self-reported activities reduced/ceased by 73-year old men in a Swedish sample (n=828).

Self-rated exertion and performance status

People reported increasingly sedentary lifestyles with increasing severity of breathlessness (by mMRC; though the same relationship was seen when using MDP A1 and D-12; data not shown) (table 2). Of those reporting activities reduced/ceased (n=162), 17.9% reported being sedentary compared with only 5.0% of those who did not forgo any activities (n=666) and, if exercising, doing so less often (table 1).

Participants reported progressive limitations on their performance for work and everyday activities as their breathlessness worsened (table 2). People reporting no breathlessness (mMRC 0) reflected that 83.8% were able to function without any restrictions decreasing to 23.5% for people with an mMRC of 4. Again, these findings are consistent across measures of breathlessness.

Logistic regression

Adjusting for key demographic factors (marital status, highest level of education), BMI and HADS scores, breathlessness is associated with increased likelihood of activities being ceased overall, and separately, for physical and sexual activities. The ORs increase as breathlessness worsens, having controlled for other factors (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted ORs of correlates of self-reported activities reduced/ceased (excluding MDP-A1 as a categorical variable with levels at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4)

| Reduced/ceased any activities* | Reduced/ceased physical activities | Reduced/ceased sexual activities | |

| OR (95% CI) | |||

| Highest level of education† | |||

| Elementary | Ref | ||

| Upper secondary | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.26) | 0.90 (0.43 to 1.88) | 0.70 (0.36 to 1.37) |

| Professional school | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.08) | 0.73 (0.35 to 1.52) | 0.75 (0.39 to 1.42) |

| University | 0.76 (0.40 to 1.44) | 0.69 (0.30 to 1.57) | 0.58 (0.28 to 1.19) |

| Marital status† | |||

| Living separately/living alone/divorced/widowed | Ref | ||

| Married/partnered | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.90) | 0.70 (0.35 to 1.43) | 0.82 (0.43 to 1.56) |

| Body mass index (BMI)‡ WHO category | |||

| Underweight/healthy weight | Ref | ||

| Overweight | 1.46 (0.8 to 2.66) | 1.58 (0.71 to 3.5) | 1.87 (0.95 to 3.69) |

| Obese | 2.53 (1.27 to 5.04) | 3.45 (1.47 to 8.13) | 2.12 (0.97 to 4.64) |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS) Anxiety‡ Score classes | |||

| Normal (0–7) | Ref | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 1.26 (0.59 to 2.71) | 1.51 (0.63 to 3.64) | 1.25 (0.54 to 2.86) |

| Abnormal (11–21) | 1.95 (0.76 to 4.99) | 3.83 (1.40 to 10.51) | 1.97 (0.78 to 4.97) |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS) Depression‡ Score classes | |||

| Normal (0–7) | Ref | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 1.78 (0.77 to 4.10) | 1.37 (0.55 to 3.43) | 2.17 (0.94 to 5.01) |

| Abnormal (11–21) | 4.42 (1.30 to 15.01) | 4.42 (1.21 to 16.12) | 4.69 (1.44 to 15.23) |

| modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale categories‡ | |||

| 0 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 4.90 (2.74 to 8.77) | 10.95 (5.15 to 23.28) | 3.54 (1.86 to 6.73) |

| 2 | 7.44 (3.96 to 14.00) | 12.84 (5.76 to 28.62) | 3.50 (1.69 to 7.23) |

| 3 | 11.79 (5.36 to 25.92) | 17.4 (6.96 to 43.52) | 10.4 (4.70 to 23.00) |

| 4 | 21.13 (7.42 to 60.16) | 49.98 (16.30 to 153.27) | 11.08 (4.20 to 29.21) |

*Activities (reduced/ceased) include: physical activities, social contacts, associations, talking on the phone, sexual activities, other.

†Baseline data (not collected at Wave 2).

‡Follow-up data (Wave 2).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that worsening breathlessness was associated with decreasing levels of self-reported physical activity, sexual activity and function. Overall, it showed that people with persisting breathlessness modify their lifestyle to avoid their breathlessness by reducing or ceasing a range of activities, seeking to minimise their exposure to the symptom.

These findings are consistent with studies that have shown progressive limitations in everyday activities for people living with the symptom in the community, with physical activities that require more strenuous exertion being most commonly affected for all age groups, followed by sexual activity.8 28 Everyday activities, including hobbies and recreation, are affected within the home (eg, gardening) and more broadly (eg, sports).9 One population study showed a positive association between the presence of breathlessness and the prevalence and duration of sexual inactivity in Australians aged 65 and over.8 Sexual function is integral to a person’s quality of life across the lifespan, including for people living with chronic, progressive conditions and at the end of life.29 30 Optimising the physical and sexual well-being of older adults is important, and both aspects should be addressed proactively in clinical consultations where persisting breathlessness is identified.31

This study showed that social activities are also adversely reduced in the presence of persisting breathlessness, which can lead to increased social isolation.32 33 Changes in people’s capacity to engage in social activities within their family unit or community may play a role in the observed relationship between anxiety, depression or both.34 Optimising people’s physical function and providing social support may improve their social functioning.

Findings also include that speech (ie, talking on the phone) also becomes challenging, which limits a critical enabler of social interactions. Persisting breathlessness restricts mobility,35 with people experiencing an increasingly shrinking physical and social environment.33 36 A decreasing ability to communicate verbally would contribute to isolation and loneliness. For younger people, such breathlessness can potentially have implications for their employment and performance at work. Speech production is altered by respiratory diseases (respiratory muscle activity and speech breathing patterns).37 Studies have shown that breathlessness impacts speech, especially when combined with a physical activity.37 Given the role communication plays in everyday life, it is important that this impact be minimised through effective management.

Importantly, these findings pertain to people with breathlessness of a median of 4 years as they report on activities reduced or ceased. The chronicity of the symptom is important in considering the impact on people’s lives and well-being.

Strengths and limitations

This population-based study offers a detailed snapshot of the impact worsening breathlessness has on everyday activities in older men, with more activities being affected as breathlessness progresses. The study offers a correlation with impaired function and level of exertion in a population that is at increased risk of declining mobility due to advancing age. The use of validated measures enables comparisons with other studies. The study had a high completion rate with 907/1193 (76%) completing the survey at follow-up.

Limitations include that no breathlessness measures were taken at baseline, thus limiting this study to a cross-sectional design. Generalisability does not extend to women or younger men. Planned follows-up will include breathlessness measures, which would enable correlations with activities reduced/ceased to be examined from the current wave 2 over time as well as the inclusion of women and younger men.

Implications for research and practice

Although breathlessness is known to adversely affect everyday activities for people living with breathlessness, this study further delineates the enormity of this impact. It provides a more refined level of detail about the type and degree to which everyday activities have been compromised for this population. This more granular detail can help counteract the pervasive clinical nihilism about breathlessness and its impact ‘… simply because it is expected’ by clinicians. It can enable clinicians to work with patients and caregivers to help them plan their day-to-day life in anticipation for that which may be compromised in the future and set meaningful priorities as people face progressive worsening of their persisting breathlessness. This can allow people to focus on activities that are real priorities to them.

Current medical history taking often fails to recognise and assess the extent of the limitations on all aspects of everyday life experienced by patients and caregivers, daily.38 This is often because patients underestimate the severity of their breathlessness and under-report its impact because they might think that this is irrelevant information for their clinicians or have reduced their activities to minimise or avoid being breathless.18 39 Given that people often live with persisting breathlessness for years, it is important to identify lifestyle changes as they occur to minimise deconditioning. Timely, regular and accurate assessment of persisting breathlessness that can identify its presence, severity and impact will enable clinicians to address previously unmet needs with appropriate evidence-based care and empower patients and caregivers to talk about their modified lifestyle as part of their history giving. For the health system, systematic screening and assessment may reduce unplanned contact with services, including hospitalisations and, if hospitalised, length of stay.

Allied health such as occupational therapists and physiotherapists is skilled at identification and management of the impact of breathlessness on everyday life.40 41 A routine referral to allied health is also warranted to ensure more in-depth exploration of these issues and the use of effective, non-pharmacological management strategies. Such interventions can help to optimise function and reduce the anxiety associated with breathlessness and its impact on everyday life as patients and caregivers learn how to self-manage breathlessness.41 42

Optimising people’s ability to perform activities that go beyond basic self-care is important, especially for older adults who might be living with multiple comorbidities and who might not have extensive support network(s). Improving people’s capacity to perform more physically demanding activities, maintain their sexual activity and intimacy and sustain meaningful social interactions within their immediate setting and the broader community will have an impact on their overall quality of life, including their mental well-being. Providing access to multidisciplinary care, including allied health clinicians, and enhanced community support will be critical to meet the needs of the growing older population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Debbie Marriott for her expertise and generous assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: all authors; data collection: MO, ME; data analyses: SC, DC; drafting the article: SK, DC; revision for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published: all authors; guarantor for the overall content: ME.

Funding: The VASCOL baseline study was funded by the Research Council of Blekinge, Sweden. MO and ME was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Swedish Research Council (reference number: 2019–02081).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request and after approval by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, by contacting: registrator@etikprovning.se. Collaboration with researchers from different disciplines is welcomed, including suggestions for additional data collection. Those interested should submit a study proposal to the primary investigator: pmekstrom@gmail.com

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019-00134). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R, et al. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:660–77. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punekar YS, Mullerova H, Small M, et al. Prevalence and burden of dyspnoea among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five European countries. Pulm Ther 2016;2:59–72. 10.1007/s41030-016-0011-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson MJ, Yorke J, Hansen-Flaschen J, et al. Towards an expert consensus to delineate a clinical syndrome of chronic breathlessness. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1602277. 10.1183/13993003.02277-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morélot-Panzini C, Adler D, Aguilaniu B, et al. Breathlessness despite optimal pathophysiological treatment: on the relevance of being chronic. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1701159. 10.1183/13993003.01159-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulos LM, Ampon RD, Currow DC, et al. Prevalence and burden of breathlessness in Australian adults: the National breathlessness Survey-a cross-sectional web-based population survey. Respirology 2021;26:768–75. 10.1111/resp.14070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currow DC, Chang S, Grande ED, et al. Quality of life changes with duration of chronic breathlessness: a random sample of community-dwelling people. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:818–27. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currow DC, Dal Grande E, Ferreira D, et al. Chronic breathlessness associated with poorer physical and mental health-related quality of life (SF-12) across all adult age groups. Thorax 2017;72:1151–3. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekström M, Johnson MJ, Taylor B, et al. Breathlessness and sexual activity in older adults: the Australian longitudinal study of ageing. npj Prim Care Resp Med 2018;28:1–6. 10.1038/s41533-018-0090-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kochovska S, Chang S, Morgan DD, et al. Activities Forgone because of chronic breathlessness: a cross-sectional population prevalence study. Palliat Med Rep 2020;1:166–70. 10.1089/pmr.2020.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchinson A, Pickering A, Williams P, et al. Breathlessness and presentation to the emergency department: a survey and clinical record review. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17:53. 10.1186/s12890-017-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Winckelmann K, Renier W, Thompson M, et al. The frequency and outcome of acute dyspnoea in primary care: an observational study. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:240–6. 10.1080/13814788.2016.1213809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchinson A, Barclay-Klingle N, Galvin K, et al. Living with breathlessness: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1701477. 10.1183/13993003.01477-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Psychosocial consequences of living with breathlessness due to advanced disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9:232–7. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Currow DC, Chang S, Ekström M, et al. Health service utilisation associated with chronic breathlessness: random population sample. ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00415-2021. 10.1183/23120541.00415-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun F, Norman IJ, While AE. Physical activity in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1–17. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim K, Taylor L. Factors associated with physical activity among older people--a population-based study. Prev Med 2005;40:33–40. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tieck K, Mackenzie L, Lovell M. The lived experience of refractory breathlessness for people living in the community. Br J Occup Ther 2019;82:127–35. 10.1177/0308022618804754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carel H. Breathlessness: the Rift between objective measurement and subjective experience. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:332–3. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30106-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsson M, Engström G, Currow DC, et al. Vascular and chronic obstructive lung disease (VASCOL): a longitudinal study on morbidity, symptoms and quality of life among older men in Blekinge County, Sweden. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046473. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580–6. 10.1378/chest.93.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundh J, Bornefalk H, Sköld CM, et al. Clinical validation of the Swedish version of Dyspnoea-12 instrument in outpatients with cardiorespiratory disease. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019;6:e000418. 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekström M, Bornefalk H, Sköld M, et al. Validation of the Swedish multidimensional dyspnea profile (MDP) in outpatients with cardiorespiratory disease. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019;6:e000381. 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young J, Badgery-Parker T, Dobbins T, et al. Comparison of ECOG/WHO performance status and ASA score as a measure of functional status. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:258–64. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekström M, Bornefalk H, Sköld CM, et al. Minimal clinically important differences for Dyspnea-12 and MDP scores are similar at 2 weeks and 6 months: follow-up of a longitudinal clinical study. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2002823. 10.1183/13993003.02823-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, et al. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:46. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swedish public health agency's national survey. Available: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/public-health-reporting/ [Accessed 16 Mar 2022].

- 28.Seow H, Dutta P, Johnson MJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of breathlessness across Canada: a national retrospective cohort study in home care and nursing home populations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;62:346–54. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hordern AJ, Currow DC. A patient-centred approach to sexuality in the face of life-limiting illness. Med J Aust 2003;179:S8–11. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matzo M, Ehiemua Pope L, Whalen J. An integrative review of sexual health issues in advanced incurable disease. J Palliat Med 2013;16:686–91. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindau ST, Surawska H, Paice J, et al. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psychooncology 2011;20:179–85. 10.1002/pon.1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gysels M, Bausewein C, Higginson IJ. Experiences of breathlessness: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Palliat Support Care 2007;5:281–302. 10.1017/S1478951507000454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ek K, Sahlberg-Blom E, Andershed B, et al. Struggling to retain living space: patients' stories about living with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1480–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currow DC, Chang S, Reddel HK, et al. Breathlessness, anxiety, depression, and function-the BAD-F study: a cross-sectional and population prevalence study in adults. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:197–205. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips J, Dal Grande E, Ritchie C, et al. A population-based cross-sectional study that defined normative population data for the Life-Space mobility Assessment-composite score. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:885–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira DH, Kochovska S, Honson A, et al. Two faces of the same coin: a qualitative study of patients’ and carers’ coexistence with chronic breathlessness associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:1–12. 10.1186/s12904-020-00572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee L, Friesen M, Lambert IR, et al. Evaluation of dyspnea during physical and speech activities in patients with pulmonary diseases. Chest 1998;113:625–32. 10.1378/chest.113.3.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celli B, Blasi F, Gaga M, et al. Perception of symptoms and quality of life - comparison of patients' and physicians' views in the COPD MIRROR study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:2189–96. 10.2147/COPD.S136711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:451–60. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan DD, White KM. Occupational therapy interventions for breathlessness at the end of life. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:138–43. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283537d0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White KM. The role of the occupational therapist in the care of people living with lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2016;5:244–6. 10.21037/tlcr.2016.05.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brighton LJ, Miller S, Farquhar M, et al. Holistic services for people with advanced disease and chronic breathlessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2019;74:270–81. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request and after approval by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, by contacting: registrator@etikprovning.se. Collaboration with researchers from different disciplines is welcomed, including suggestions for additional data collection. Those interested should submit a study proposal to the primary investigator: pmekstrom@gmail.com