Abstract

A strain designated TFA which very efficiently utilizes tetralin has been isolated from the Rhine river. The strain has been identified as Sphingomonas macrogoltabidus, based on 16S rDNA sequence similarity. Genetic analysis of tetralin biodegradation has been performed by insertion mutagenesis and by physical analysis and analysis of complementation between the mutants. The genes involved in tetralin utilization are clustered in a region of 9 kb, comprising at least five genes grouped in two divergently transcribed operons.

Tetralin (1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene) is produced for industrial purposes from naphthalene by catalytic hydrogenation or from anthracene by cracking. Because of its solvent characteristics, it is widely used as a degreasing agent and solvent for fats, resins, and waxes, as a substitute for turpentine in paints, lacquers, and shoe polishes, and also in the petrochemical industry in connection with coal liquefaction (7). It is also present in coal tar and petroleum from different origins. Tetralin is toxic to bacteria at concentrations above 15 μM (17). Because of its lipophilic character, it may interact with biological membranes, leading to changes in their structure and function, which in turn may impair growth and cell activity (19, 20). Although changes in the composition of the membranes may lead to organic solvent tolerance (10), tetralin is also highly toxic because of the formation of hydroperoxides in the cell (6).

Tetralin is a bicyclic molecule consisting of an aromatic moiety and an alicyclic moiety which share two carbon atoms. This is an interesting characteristic, since oxidation pathways known to attack aromatic rings are quite different from those acting on alicyclic rings (2, 26). In principle, the initial transformation of tetralin may involve an attack of either the aromatic or alicyclic ring, thus rendering the corresponding alicyclic or aromatic intermediate. The mineralization of tetralin could then require the recruitment of two types of metabolic pathways. In spite of this, very little is known about tetralin utilization by bacteria. Tetralin oxidation by mixed cultures and co-oxidation by pure cultures in the presence of a mixture of substrates have long been reported (21, 23), but only a few bacterial strains able to grow on tetralin as the sole carbon and energy source have been isolated (15, 17). They all grow slowly on tetralin, with 18 h being the best reported doubling time (17). By identifying the potential intermediates accumulated, several reports suggest that some bacteria, such as Pseudomonas stutzeri AS39 (15), initially hydroxylate and further oxidize the alicyclic ring, since 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthol and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalone are accumulated. Others, such as Corynebacterium sp. strain C125 (18), initially modify the aromatic ring, which after dioxygenation and dehydrogenation is cleaved in the extradiol position by a catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. However, a complete biodegradation pathway has not been elucidated.

A new strain designated TFA has been isolated from mud from the Rhine river by an enrichment culture in liquid carbon-free minimal medium (5) to which tetralin was supplied via the vapor phase. Strain TFA is a small, short rod-shaped, strictly aerobic, gram-negative bacterium, naturally tolerant to 100 mg of streptomycin liter−1 and able to grow on tetralin as the only carbon and energy source to a high cell density (2 × 109 CFU ml−1), with a doubling time of 8 h, in a wide range of pH values (5.3 to 9). This is the best reported doubling time for a strain growing on tetralin (17).

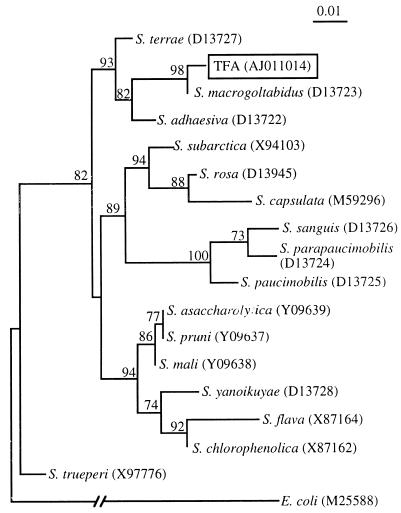

The fatty acid profile of strain TFA did not match any of those in the database of the Microbial Identification System. The metabolic fingerprint from the Biolog MicroPlate tests did not allow the unambiguous identification of the strain either, since it showed only a very low-level match to that of Acinetobacter radioresistens. An internal 16S rDNA fragment was amplified by PCR (ProGene thermocycler; Techne Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) with the primers f27 and r519 (11) and commercially sequenced (Boehringer Mannheim). The resulting sequence of 455 bp was initially compared to those in the databases by using the FASTA3 program. Unambiguous positions of representative sequences of different species of the genus Sphingomonas, which showed a high similarity to that of strain TFA, were aligned by using the CLUSTAL W program (25) with default parameters. Maximum likelihood analysis was conducted with the NUCML program of the MOLPHY package (1). We calculated a distance matrix by using the HKY85 model of nucleotide substitution (9) and constructed a phylogenetic tree by the neighbor-joining method (13). This analysis clearly showed that strain TFA belongs to the genus Sphingomonas (Fig. 1). Its rDNA sequence was most similar to that of Sphingomonas macrogoltabidus, a polyethylene glycol-utilizing bacterium (24), with which it showed 98.9% identity. We tentatively assigned strain TFA to this species, although we admit that an unambiguous assignment is difficult, since the 16S rDNA sequence is not complete and no clear officially recognized standard exists relating 16S rDNA sequence similarity to taxonomic hierarchy.

FIG. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree inferred from the 16S rRNA sequences of species of the genus Sphingomonas. The E. coli sequence was used as an out-group. Nucleotide sequence database accession numbers are shown in parentheses. The length of each branch is proportional to the estimated number of substitutions per position. Numbers in nodes are local bootstrap probabilities expressed as percentages (1).

Mutagenesis with Tn5 or miniTn5Km was carried out by overnight matings of Escherichia coli strains, bearing pGS9 (16) or pUT-miniTn5Km (3), with strain TFA, on plates of MML medium (mineral medium plus 2 g of tryptone liter−1 and 1 g of yeast extract liter−1). The frequency of kanamycin-resistant transconjugants ranged from 4 × 10−5 to 4 × 10−6 per recipient cell on plates of mineral medium containing 20 mg of kanamycin liter−1 and 5 g of β-hydroxybutyrate liter−1 as the carbon source. Five independent mutants unable to use tetralin as the only carbon source (Thn−) were isolated from a total of 3,920 transconjugants bearing Tn5 insertions. Four additional Thn− mutants were isolated from 3,336 transconjugants bearing miniTn5 insertions. Transposon insertions were designated by T or mT, depending on whether Tn5 or miniTn5Km was inserted, followed by a collection number. Total DNA from each mutant was isolated as described previously (8) and digested with different restriction enzymes, and Southern blots were hybridized with a kanamycin resistance probe (internal HindIII fragment of Tn5). Results (not shown) indicated that all mutants carried a single insertion except the mutant TFA-T3, which bore two Tn5 insertions. Hybridization patterns also showed that the insertions were in different locations, thus confirming that mutants bore independent transposon insertions, although at least some of them could be closely linked.

To confirm that the Thn− phenotype of the mutants was conferred by the transposon insertions and also to isolate the insertion responsible for the mutant phenotype in strain TFA-T3, 50 ng of total DNA (of 40 to 50 kb) from several mutants, including strain TFA-T3, was used to directly transform the wild-type strain TFA by electrotransformation with a BTX Electro cell manipulator (Biotechnologies & Experimental Research, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Under optimal conditions (2.5 kV and 246 Ω), kanamycin-resistant transformants appeared at a frequency of 3 × 104 to 5 × 104 μg of DNA−1. Transformants obtained with DNA from the mutant strain TFA-T3 were of two types, Thn+ or Thn−, and the phenotype depended on which of the two original insertions in strain TFA-T3 had been acquired. The original strain, TFA-T3, was replaced by one of the Thn− transformants for subsequent work. On the other hand, more than 95% of transformants obtained with DNA from the other mutants exhibited a Thn− phenotype. The low background level of kanamycin-resistant Thn+ colonies obtained after transformation apparently consisted of spontaneously kanamycin-resistant mutants (frequency of spontaneous mutation was 10−8 cell−1). Southern blots of total DNA from selected transformants confirmed that insertions in the transformants were in the same locations as in the original mutants (data not shown). These results clearly show that strain TFA can be readily transformed with linear DNA, that double recombination leading to the integration of a transposon insertion into the TFA genome is more frequent than a new transposition event, and that transposon insertions were responsible for the Thn− phenotype.

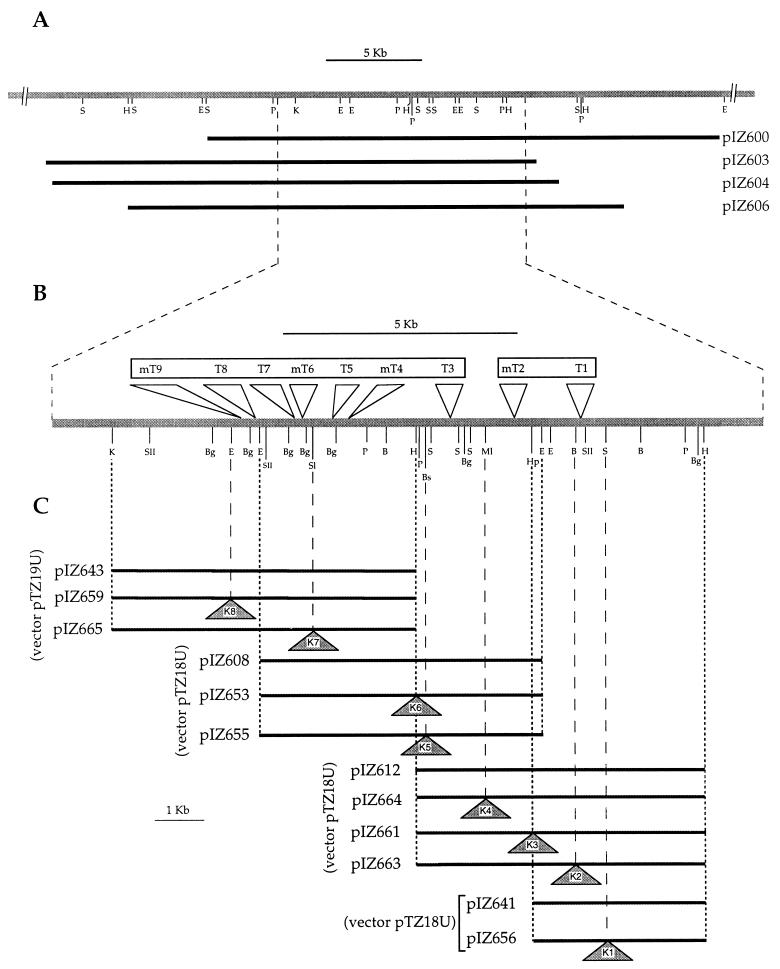

To construct a genomic library of the strain, DNA fragments of 23 to 33 kb were isolated after partial digestion of total DNA from strain TFA with Sau3AI, ligated to the cosmid pLAFR3 (22), packaged into lambda phages (packaging extract from Pharmacia), and transfected into E. coli DH5α. If we assume a genome complexity similar to that of E. coli, the number of transfectants indicated that the probability of a gene being represented in the gene bank was 0.99. The whole gene bank was transferred from DH5α to each of the Thn− mutants by overnight matings which also included DH5α bearing the helper plasmid pRK2013 in triparental mating mixtures, as described previously (4). The frequency of transconjugants resistant to tetracycline (5 mg liter−1) was 10−2 per recipient cell, and the frequency of complemented Thn+ tetracycline-resistant transconjugants was 10−5 per recipient cell. Restriction analysis of cosmids isolated from different Thn+ transconjugants led to the identification of four different cosmids which shared a common DNA region of ∼17 kb (Fig. 2A). The four cosmids were reintroduced into DH5α by electrotransformation, and transformants bearing each of the cosmids were used as donors in new matings with the Thn− mutants. All four cosmids complemented each of the Thn− transposon mutants, thus showing that DNA regions in which transposons were inserted are represented in the four cosmids.

FIG. 2.

(A) Physical map of the genomic region of strain TFA involved in tetralin biodegradation. Genomic DNA carried by each of the cosmids complementing the transposon mutants are represented by black bars. (B) Physical location of each transposon insertion. T or mT denotes Tn5 or miniTn5Km insertions, respectively. Boxes grouping transposon insertions represent complementation groups. (C) Subcloning of the genomic region of strain TFA involved in tetralin biodegradation and location of the KIXX cassette insertions (K1 to K8) present in each subclone. B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; Bs, BstEII; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Hp, HpaI; K, KpnI; Ml, MluI; P, PstI; SII, SacII; Sl, SalI; S, SmaI.

Plasmid DNA from each complemented mutant bearing the cosmid pIZ606 was isolated by the alkaline lysis procedure (14) and used to transform DH5α by electrotransformation. Transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani medium containing either tetracycline (vector selective marker) or kanamycin (transposon marker). Tetracycline-resistant transformants were readily selected at similar frequencies. Interestingly, kanamycin-resistant transformants were also selected, although their frequencies varied widely depending on the DNA preparation. All kanamycin-resistant transformants were also resistant to tetracycline. Plasmid DNA from one kanamycin-resistant transformant coming from each of the nine electrotransformations was isolated and analyzed. Comparison of the restriction fragments of the cosmids isolated from these transformants to those of pIZ606 showed that all cosmids conferring kanamycin resistance were pIZ606 derivatives which had acquired a Tn5 or miniTn5 insertion. Insertions were precisely mapped by restriction fragment comparison, and they appeared to be clustered within a region of 7.5 kb, which was present in the four original cosmids complementing the Thn− mutants. Their physical locations are shown in Fig. 2B. By a comparison to the hybridization pattern obtained with the original mutants (data not shown), it was clear that the locations of the insertions in the pIZ606 derivatives corresponded to those in the original mutants, thus showing that mutations had been readily cloned in vivo within the cosmid pIZ606 by a double crossover event. Although the number of mutants isolated is not very high, the clustering of all of them suggests that all gene products required for tetralin utilization are highly likely to be encoded in this region.

Complementation tests were performed by the conjugative transfer of pIZ606 or each cosmid derivative from DH5α to each Thn− mutant. Although recombination between DNA sequences of the mutants and those in the cosmids may take place, an estimation of the number of Thn+ transconjugants in relation to the total number of tetracycline-resistant transconjugants allows a distinction between true complementation and recombination events leading to the reconstitution of a wild-type sequence. Positive complementation with a pIZ606 derivative cosmid was assumed when the number of Thn+ transconjugants in relation to the total number of transconjugants was of the same order of magnitude as that obtained with the cosmid pIZ606, which bears the wild-type sequence. Typical values of positive complementation ranged from 25 to 100% of that obtained with pIZ606. Values for those matings yielding negative complementation were 5% or lower. Results clearly showed two complementation groups (Fig. 2B). Since some insertions which did not complement are separated by long distances, it is highly unlikely that all insertions of the same complementation group are in the same gene. This result suggests that these insertion mutations are polar and that complementation groups therefore represent operons.

To genetically identify genes present in these operons, we decided to construct additional mutants by the insertion of the KIXX cassette, which does not normally result in polar mutations since it has “out” promoters driving the transcription of the flanking sequences. To this end, different fragments of the region involved in tetralin biodegradation were isolated from the cosmid pIZ606 and cloned in pTZ18U or pTZ19U (12), which do not replicate in strain TFA, and the KIXX cassette was inserted at selected restriction sites (Fig. 2C). The resulting plasmids were introduced into strain TFA by electrotransformation, and selection was made for kanamycin resistance, the cassette resistance marker. Among the transformants resistant to kanamycin, ∼90% were also resistant to 5 mg of ampicillin (vector resistance marker) liter−1, thus resulting from a single recombination event leading to the integration of the plasmid into the TFA genome. However, some transformants were sensitive to ampicillin, suggesting that these may have arisen from a double recombination event leading to a substitution of the wild-type sequence by the KIXX insertion. These transformants were Thn−, indicating that the insertion of the cassette in these locations resulted in a loss of tetralin utilization capability. The KIXX insertions at the expected locations in transformants were confirmed by hybridization (data not shown).

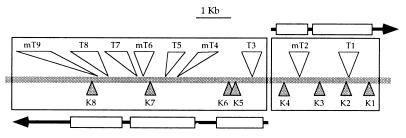

Complementation tests were also performed by mating DH5α, harboring either pIZ606 or each cosmid derivative bearing the transposon insertions, to each of the KIXX insertion mutants. Using the same criterion as for the analysis of complementation between the transposon insertions, most of the matings resulted in a clear positive or negative complementation (Table 1). The combined information from the complementation tests (Table 1) and the relative physical location of each insertion (Fig. 3) allowed us to make the following interpretations. (i) The complementation patterns fit well with the notion that two operons, previously identified by complementation between transposon mutants, do exist in this DNA region. (ii) Since transposon insertions are polar, cosmids with transposons could complement KIXX insertions in the same operon only if transposons are inserted in other genes located downstream of the KIXX insertion; therefore, the complementation pattern may also reveal the direction of transcription of each operon. The complementation pattern in Table 1 indicates that the two operons are divergently transcribed. (iii) The two operons are very close, since insertions T3 and K4, one in each operon, are separated by 800 bp. (iv) The operon transcribed to the right in Fig. 3 comprises at least two genes. This conclusion is based on the complementation of K4 with T1 and mT2. (v) The operon transcribed to the left in Fig. 3 comprises at least three genes. This is based on complementation patterns of K5, K6, and K7.

TABLE 1.

Complementation of Thn− mutants bearing KIXX insertions with derivatives of cosmid pIZ606 bearing Tn5 or miniTn5Km insertions

| pIZ606 cosmid with insertion | KIXX insertiona

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K8 | K7 | K6 | K5 | K4 | K3 | K2 | K1 | |

| None | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mT9 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T8 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T7 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mT6 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T5 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mT4 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T3 | + | ± | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| mT2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| T1 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

±, ambiguous complementation result.

FIG. 3.

Diagram showing the locations of transposon and KIXX insertions. The two divergent operons inferred from the complementation results are shown by black arrows which contain white rectangles representing complementation groups.

However, the complementation pattern of K8 did not fit well with the interpretation of the two divergent operons. It should not have been complemented by any cosmid bearing an insertion in the same operon, or it should have been complemented by all cosmids, if K8 were located in a third operon. However, it was complemented by cosmids bearing T3 and mT4 but not by those bearing T5, mT6, T7, T8, or mT9. A possible explanation for this complementation pattern is that weak transcription from an internal promoter located between mT4 and T5 is sufficient to provide enough product of the gene mutated in K8 to complement the mutation.

During analysis of strain TFA to identify tetralin biodegradation genes, we have found that the recombination frequency in strain TFA is apparently high enough to allow the easy introduction of cloned insertion mutations into the genome by a double crossover event, with no need of counterselecting the vector, an in vivo rescue of mutations in plasmids bearing the wild-type sequence, or even an insertion mutation transfer between strains, by directly transforming with linear genomic DNA from the donor mutant. These characteristics substantially increase the possibilities of genetic manipulation in strain TFA, thus making it an excellent candidate for metabolic engineering.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AJ011014.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología, grant BIO96-0908, by the European Union under the ENVIRONMENT program, contract EV5V-CT92-0192, and by a fellowship of the Spanish Ministerio de Educación to M.J.H.

We thank Jürgen Havel for the enrichment of strain TFA, Gabriel Gutierrez for his assistance in DNA sequence analysis, and Josep Casadesús for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi J, Hasegawa M. Computer science monographs. Vol. 28. Tokyo, Japan: The Institute of Statistical Mathematics; 1996. MOLPHY version 2.3: programs in molecular phylogenetics based in maximum likelihood. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagley S. Microbial metabolism of aromatic compounds. In: Moo-Young M, editor. Comprehensive biotechnology, vol. I. A. T. Bull and H. Dalton (ed.), The principles of biotechnology: scientific fundamentals. Oxford, England: Pergamon Press; 1985. pp. 483–505. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in Gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorn E, Hellwig M, Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Isolation and characterization of a 3-cholobenzoate degrading pseudomonad. Arch Microbiol. 1974;99:61–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00696222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrante A A, Augliera J, Lewis K, Klibanov A M. Cloning of an organic solvent-resistance gene in Escherichia coli: the unexpected role of alkylhydroperoxide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7617–7621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaydos R M. Naphthalene. In: Grayson M, Eckroth D, editors. Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1981. pp. 698–719. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govantes F, Molina-López J A, Santero E. Mechanism of coordinated synthesis of the antagonistic regulatory proteins NifL and NifA of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6817–6823. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6817-6823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22:160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heipieper H J, Weber F J, Sikkema J, Keweloh H, de Bont J A M. Mechanisms of resistance of whole cells to toxic organic solvents. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:409–415. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugenholtz P, Pitulle C, Hershberger K L, Pace N R. Novel division level bacterial diversity in a Yellowstone hot spring. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:366–376. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.366-376.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead D A, Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Single-stranded DNA “blue” T7 promoter plasmids: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1:67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber A F, Winkler U K. Transformation of tetralin by whole cells of Pseudomonas stutzeri AS 39. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1983;18:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selvaraj G, Iyer V N. Suicide plasmid vehicles for insertion mutagenesis in Rhizobium meliloti and related bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:1292–1300. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.3.1292-1300.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M. Isolation and initial characterization of bacteria growing on tetralin. Biodegradation. 1991;2:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M. Metabolism of tetralin (1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene) in Corynebacterium sp. strain C125. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:567–572. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.567-572.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M, Poolman B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikkema J, Poolman B, Konings W N, de Bont J A M. Effects of the membrane action of tetralin on the functional and structural properties of artificial and bacterial membranes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2986–2992. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2986-2992.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soli G, Bens E M. Bacteria which attack petroleum hydrocarbons in a saline medium. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1972;14:319–330. doi: 10.1002/bit.260140305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staskawicz B, Dahlbeck N, Keen N, Napoli C. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5789–5794. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5789-5794.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strawinsky R J, Stoner R W. The utilization of hydrocarbons by bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1940;40:461–462. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi M, Kawai F, Shimada Y, Toyota A. Taxonomic study of polyethylene glycol-utilizing bacteria: emended description of the genus Sphingomonas and new descriptions of Sphingomonas macrogoltabidus sp. nov., Sphingomonas sanguis sp. nov. and Sphingomonas terrae sp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trudgill P W. Microbial degradation of the alicyclic ring. In: Gibson D T, editor. Microbial degradation of organic compounds. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1984. pp. 131–180. [Google Scholar]