Abstract

Aims

Cardiomyocyte Ca2+ homoeostasis is altered with ageing and predisposes the heart to Ca2+ intolerance and arrhythmia. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is an osmotically activated cation channel with expression in cardiomyocytes of the aged heart. The objective of this study was to examine the role of TRPV4 in Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis following ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R), a pathological scenario associated with osmotic stress.

Methods and results

Cardiomyocyte membrane potential was monitored prior to and following I/R in Langendorff-perfused hearts of Aged (19–28 months) male and female C57BL/6 mice ± TRPV4 inhibition (1 μM HC067047, HC). Diastolic resting membrane potential was similar between Aged and Aged HC at baseline, but following I/R Aged exhibited depolarized diastolic membrane potential vs. Aged HC. The effects of TRPV4 on cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signalling following I/R were examined in isolated hearts of Aged cardiac-specific GCaMP6f mice (±HC) using high-speed confocal fluorescence microscopy, with cardiomyocytes of Aged exhibiting an increased incidence of pro-arrhythmic Ca2+ signalling vs. Aged HC. In the isolated cell environment, cardiomyocytes of Aged responded to sustained hypoosmotic stress (250mOsm) with an increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude (fluo-4) and higher incidence of pro-arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ signals vs. Aged HC. Intracardiac electrocardiogram measurements in isolated hearts following I/R revealed an increased arrhythmia incidence, an accelerated time to ventricular arrhythmia, and increased arrhythmia score in Aged vs. Aged HC. Aged exhibited depolarized resting membrane potential, increased pro-arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ signalling, and greater incidence of arrhythmia when compared with Young (3–5 months).

Conclusion

TRPV4 contributes to pro-arrhythmic cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signalling, electrophysiological abnormalities, and ventricular arrhythmia in the aged mouse heart.

Keywords: Calcium, Excitation-contraction coupling, Ischemia–reperfusion, Arrhythmia, GCaMP

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cytosolic Ca2+ links the action potential (AP) to mechanical contraction during cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). Ca2+ influx via T-tubule L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC) activates Ca2+-induced-Ca2+ release (CICR) from Ryanodine Receptors (RyRs) in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Generalized CICR initiates systolic contraction, and the SR Ca2+ release per cycle depends on SR Ca2+ content and the amplitude of LTCC Ca2+ influx. Cellular Ca2+ extrusion or sequestration directs diastolic relaxation, predominantly via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and the Sarco-Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA).1 A number of alterations to ECC proteins occur with ageing. Most notably, RyRs exhibit increased diastolic Ca2+ leak, and SERCA expression and/or function declines leading to impaired SR Ca2+ sequestration. The net effect of these changes is a decreased tolerance to elevated intracellular Ca2+ and increased risk for Ca2+-dependent arrhythmias.2,3

Advanced age has been shown to be the strongest variable associating with 30-day mortality following myocardial infarction (MI), and cardiac arrhythmias are a leading cause of mortality following MI.4–6 Paradoxically, the prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias increases when blood flow is restored to ischaemic regions, in part, due to an inability to restore cardiomyocyte Ca2+ homoeostasis. Indeed, cardiomyocyte Ca2+ overload, Ca2+-dependent cell death, and Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia are the major contributors to pathology of ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury. Cardiomyocyte Ca2+ overload following I/R is classically thought to be a pH-driven process, initiated by anaerobic metabolism during ischaemia and associated accumulation of H+ and cellular metabolites. During reperfusion and wash-out of the extracellular milieu, the large outward H+ gradient promotes Na+/H+ and subsequent Na+/Ca2+ exchange.7 Restoration of oxygen during reperfusion also increases cellular oxidative stress with resulting impaired Ca2+ transport via oxidative modification of RyR and SERCA.7–9 The osmotic environment also exhibits a large shift during no-flow ischaemia, as pH and cellular metabolites equilibrate across the plasma membrane and generate a hyperosmotic environment relative to physiological levels. However, upon reperfusion and restoration of the extracellular environment hypoosmotic stress is sensed by the cardiomyocyte. Activation of osmotic- or stretch-sensitive cation channels may therefore also contribute to Ca2+ overload and Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia following I/R.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels alter Ca2+ homoeostasis in cardiac disease states.10–16 Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) functions primarily as a Ca2+ influx channel and is responsive to a number of gating stimuli, including hypoosmotic stress.17 TRPV4 has a high single-channel conductance (50–100 pS), forms homo- and hetero-tetramers with other TRP channels, and exhibits cooperative gating.18–20 Importantly, TRPV4 protein expression increases in cardiomyocytes with ageing and previous work indicates a role for TRPV4 in augmented Ca2+ cycling following hypoosmotic stress and hypercontractility following I/R.21 In this investigation, we use a multi-faceted experimental approach in combination with the specific small-molecule TRPV4 inhibitor HC067047 to test the hypothesis that TRPV4 activation contributes to changes in cardiomyocyte electrophysiology and Ca2+ homoeostasis following I/R in hearts of aged mice. We show that TRPV4 contributes to cardiomyocyte membrane depolarization, pro-arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ signalling, and ventricular arrhythmia in hearts of aged mice following I/R. These factors make TRPV4 a potential ion channel target to prevent cardiomyocyte Ca2+ overload and Ca2+-dependent arrhythmogenesis following I/R in aged populations, which are at the highest risk of MI.

2. Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

Animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Missouri (Approval reference number 9581), conform to the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, and complied with all US regulations involving animal experiments. Male and female C57BL/6 and transgenic MerCreMer x Tg(Rosa-CAG-loxP-STOP-loxP-GCaMP6f) were studied at ages of 3–5 (Young) or 19–28 months (Aged). Mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine: xylazine (100 mg/kg: 5 mg/kg) and hearts were rapidly (∼30 s) excised for subsequent experimentation.

2.2 Solutions

Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) for Langendorff heart experiments contained (in mmol/L): 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose, 0.4 caprylic acid, 1 pyruvate, and 0.5 Na EDTA. CaCl2 was 1.8 mmol/L for electrophysiology measurements and 1 mmol/L for Ca2+ imaging experiments. For isolated cardiomyocyte experiments, sustained hypoosmotic stress was achieved via a switch from a calculated ∼300 mOsm/L solution containing (in mmol/L) 110 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10D-glucose, 10 Hepes, 50 Mannitol, pH 7.4 with NaOH to ∼250 mOsm/L solution of the same composition lacking Mannitol.

2.3 Ischaemia–reperfusion electrophysiology

Langendorff heart experiments were performed at 34–36°C while perfused with KHB at constant afterload (60 mmHg). Following aortic cannulation (∼4 min), the left anterior descending (LAD) artery was ligated using 6-0 PolyPro Blue Monofilament suture (NC-1 needle). Organ-level electrical activity was monitored by an intracardiac ECG catheter. For intracellular recording, 40 μmol/L blebbistatin was used to mechanically arrest the heart, while epicardial AP recordings from the left ventricular area at-risk were obtained under baseline, ischaemic (45 min), and reperfusion (30 min) conditions. Intracellular recordings were made using glass micropipettes (1.0 mm, 40–50 MOhm, 2 mol/L KCl filling solution), an ELC-03XS amplifier, and Clampex 11.3.4 (2018) software.

2.4 Ischaemia–reperfusion Ca2+ experiments

Left ventricular cardiomyocyte Ca2+ was monitored in situ after global I/R using Langendorff-perfused hearts with cardiac-specific expression of the Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f. The Langendorff heart protocol was modified to aid in cardioplegia for confocal imaging (28–30°C, 1 mmol/L Ca2+ KHB, and 40 μmol/L blebbistatin). Hearts were paced at 5–6 Hz, and GCaMP6f Ca2+ fluorescence was monitored using high-speed laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy (100 frames/second; 488-nm excitation; 500–560-nm emission) during baseline, ischaemia, and reperfusion conditions.

2.5 Cardiomyocyte functional experiments

Intracellular Ca2+ (Fluo-4/AM) was monitored in electrically stimulated (0.5 Hz) isolated cardiomyocytes at 25°C using laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy. Following 5 min of baseline recording under isosmotic conditions (∼300 mOsm/L), cardiomyocytes were superfused with ∼250 mOsm/L hypoosmotic solution for 30 min and imaged every 60 s.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All data are reported as individual observations or means ± standard error (SE). Summary data were analysed using parametric (paired/unpaired t tests or nested t test) or nonparametric (Wilcoxon or Mann–Whitney rank test) where appropriate based on experimental design (Shapiro–Wilk test for normality). Linear regression was conducted on AP characteristics, and regression lines are accompanied by a 95% prediction band. One-tailed tests were conducted for arrhythmia comparisons. Population percentages were compared by Z test of two population proportions. For nonlinear fits to frequency distributions, an extra sum-of-squares F test was used to test whether membrane potential frequency histograms were best fit by a single Gaussian distribution or sum of two Gaussian distributions. In AP parameter analysis and GCaMP6f cardiomyocyte Ca2+ fluorescence data, the F test was used to compare population variance. Data are reported as statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*). All statistics were performed with GraphPad Prism version 8.4.2 (464) for MacOS. Additional details can be found in the Supplementary material online, Methods. The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

3. Results

3.1 TRPV4 contributes to membrane depolarization following I/R in aged hearts

Cardiomyocyte resting membrane potential (RMP) of Aged hearts and Aged hearts treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC) demonstrated similar means and distributions under baseline conditions (Figure 1A–C). During the reperfusion phase of I/R, the mean RMP was depolarized in Aged vs. Aged HC (Figure 1D and E). The RMP population distribution during reperfusion in Aged was best fit by a double Gaussian (Figure 1F, left) with means at −73 mV (primary, mean 1) and −63 mV (secondary, mean 2). Aged HC exhibited a single population with mean at −74 mV (Figure 1F, right). Therefore, the shift in overall group mean in Aged was due to the emergence of a secondary population of depolarized cardiomyocytes. As depolarization of RMP leads to secondary effects on AP waveform, we examined the relationship between RMP and AP amplitude (Figure 2A, Supplementary material online, Figure S1), RMP and AP upstroke velocity (Figure 2B, Supplementary material online, Figure S2), and RMP and AP decay time (Figure 2C and D, Supplementary material online, Figure S3). In both Aged and Aged HC, AP amplitude (Figure 2A) and AP upstroke velocity (Figure 2B) exhibited a negative correlation with RMP across the full range of RMP values. The relationship between RMP and decay time was more complex due to a higher sample variance in Aged vs. Aged HC (F test, P < 0.001) and a poor fit to linear regression over the entire reperfusion RMP range (Supplementary material online, Figure S3). Data were therefore separated into two RMP ranges for linear regression. In both Aged and Aged HC, decay time was independent of RMP over the −90 to −60 mV range. Over the −60 to −35 mV range decay time exhibited a positive correlation with RMP in Aged, with prolonged decay time at more depolarized RMP. In Aged HC, there were minimal data points in the −60 to −35 mV RMP range (Figure 2D) and no points more depolarized than −50 mV for comparison to Aged (Figure 1F). Young hearts were more resistant to depolarization during reperfusion compared with Aged (Mean −76mV, Supplementary material online, Figure S4C). Furthermore, a secondary population of depolarized cardiomyocytes was not evident in Young hearts (Supplementary material online, Figure S4D). Taken together, these data indicate TRPV4 contributes to a shift in RMP with associated alteration in AP waveform in aged hearts following I/R.

Figure 1.

TRPV4 contributes to membrane depolarization following ischaemia–reperfusion in aged hearts. (A) Example left ventricular AP from cardiomyocytes of an isolated perfused Aged heart (left) and Aged heart pre-treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L, right) under baseline conditions. (B) Summary data of cardiomyocyte resting membrane potential (RMP) of Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey) under baseline conditions. (C) Frequency histograms of RMP with associated Gaussian fits of cardiomyocyte populations under baseline conditions in Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey) hearts. (D) Example left ventricular APs from cardiomyocytes of an isolated perfused Aged (left) and Aged HC heart (right) following ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R). (E) Summary data of cardiomyocyte RMP of Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey) following I/R. (F) Frequency histograms of RMP with associated Gaussian fits (Double Gaussian Aged; Single Gaussian Aged HC) of cardiomyocyte populations following I/R in Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). n = 52 cells from N = 6 animals Aged baseline; n = 47 cells from N = 5 animals Aged HC baseline; n = 122 cells from N = 6 animals Aged I/R; n = 108 cells from N = 5 animals Aged HC I/R. *P = 0.019 Aged vs. Aged HC, nested t test (E).

Figure 2.

Cardiomyocyte action potential properties following ischaemia–reperfusion in aged hearts. (A) Linear regression (solid line) with 95% prediction bands (dashed lines) of AP amplitude vs. RMP following I/R of Aged (burgundy, left) Aged pre-treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L, grey, centre). Overlay of linear regression (solid lines) and prediction bands (dashed lines) are shown at right for Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). (B) Linear regression (solid line) with 95% prediction bands (dashed lines) of AP upstroke velocity vs. RMP following I/R of Aged (burgundy, left) and Aged HC (grey, centre). Overlay of linear regression (solid lines) and prediction bands (dashed lines) are shown at right for Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). (C) Linear regression (solid line) with 95% prediction bands (dashed lines) of AP decay time (90–10%) vs. RMP following I/R of Aged (burgundy, left) and Aged HC (grey, centre) from −90 to −60 mV. Overlay of linear regression (solid lines) and prediction bands (dashed lines) are shown at right for Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). (D) Linear regression (solid line) with 95% prediction bands (dashed lines) of AP decay time (90 − 10%) vs. RMP following I/R of Aged (burgundy, left) and Aged HC (grey, centre) constrained from −60 to −35 mV. n = 178–219 cells from N = 5–6 animals Aged; n = 141–148 cells from N = 4 animals Aged HC (A–C). n = 41 cells from N = 6 animals Aged; n = 7 cells from N = 4 animals Aged HC (D). Note minimal points in Aged HC in this RMP range, with no data points between −50 and −35 mV. One Aged HC heart was excluded from regression analysis due to low rate (<2 Hz).

3.2 Arrhythmic cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signals following I/R observed in situ in hearts of aged GCaMP6f mice

Langendorff-perfused hearts with cardiomyocyte-specific expression of GCaMP6f (Figure 3A) were subjected to global I/R, while subepicardial cardiomyocytes were imaged with high-speed 2D confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3B). Under baseline conditions, cardiomyocytes of Aged GCaMP6f hearts demonstrated similar F/F0 values compared with those of Aged GCaMP6f HC (Figure 3C, left panel), and both groups had a similar population distribution and variance (F test, P = 0.7). During the first 30 min following I/R, cardiomyocytes from Aged GCaMP6f hearts demonstrated a wide population distribution (Figure 3C, right panel) with a higher sample variance vs. Aged GCaMP6f HC (F test, P < 0.001). This dispersion in F/F0 values was due in part to the emergence of cardiomyocyte populations with high F/F0 (Figure 3B, Cell 4 trace, Figure 3C, right panel). Further, population analysis of all cells sampled during the first 30 min following I/R revealed a higher proportion of cardiomyocytes exhibiting Ca2+ waves and non-steady-state ECC in Aged GCaMP6f (79/1,658) vs. Aged GCaMP6f HC (0/942) (Figure 3D). Aged GCaMP6f hearts exhibited a wide population distribution and increased F/F0 during reperfusion compared with Young GCaMP6f hearts (Supplementary material online, Figure S5A). Further, Aged GCaMP6f hearts had increased Ca2+ waves and non-steady-state ECC compared with Young GCaMP6f hearts (Supplementary material online, Figure S5B).

Figure 3.

Cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signalling following ischaemia–reperfusion in aged hearts. (A) Schematic of MerCreMer × GCaMP6f double transgenic mice. When treated with tamoxifen ‘STOP’ sequence is excised leading to GCaMP6f expression in cardiomyocytes. Unfiltered and filtered light (460–480 nm excitation/500–540 emission) images of an isolated perfused Aged GCaMP6f heart shown at right. (B) Example high-speed two-dimensional confocal images of GCaMP6f fluorescence in sub-epicardial cardiomyocytes of an Aged GCaMP6f heart during diastole (upper) and peak systole (lower) under baseline conditions (left) and following I/R (right). Raw fluorescence profiles (8 bits) of baseline cells 1 and 2 (left) and I/R cells 3 and 4 (right) shown below images. Dashed lines indicate diastolic and systolic fluorescence values of a typical cell within the field, and illustrate heterogeneity in Aged following I/R (cells 3 and 4). (C) Summary super plots of Ca2+ transient amplitude (F/F0, calculated per cell) in Aged and Aged pre-treated with TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L) under baseline conditions (left) and following I/R (right). Individual cardiomyocyte F/F0 values are presented (n = 155 Aged and n = 180 Aged HC baseline; n = 580 Aged and n = 513 Aged HC I/R) with sample mean ± SEM calculated per heart (N = 5 Aged, N = 3 Aged HC) and shown to right of individual cardiomyocyte scatter plots, with corresponding colour. Aged and Aged HC had equal variance under baseline conditions (F test P = 0.4, nested t test P = 0.47) but unequal variance following I/R (F test P < 0.001, nested t test P = 0.2). (D) Example high-speed (100 Hz) two-dimensional confocal images of GCaMP6f fluorescence in sub-epicardial cardiomyocytes of an Aged GCaMP6f heart during diastole (upper) and peak systole (lower) following I/R. Raw fluorescence profiles of stable cell (cell 1) and cell exhibiting spontaneous Ca2+ waves (cell 2) are shown below images. Dashed lines indicate diastolic and systolic fluorescence of cell 1 (left). Summary data of percent of total cells (79/1,658 Aged vs. 0/942 Aged HC) exhibiting Ca2+ wave or Ca2+ overload behaviour following I/R, calculated across all experimental preparations in Aged (burgundy) and Aged pre-treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L). *P < 0.001 Aged vs. Aged HC, two-tailed Z test of two population proportions (right). Distance scale bars in B, D = 30 µm.

3.3 Arrhythmic Ca2+ signals following hypoosmotic stress in cardiomyocytes of aged hearts

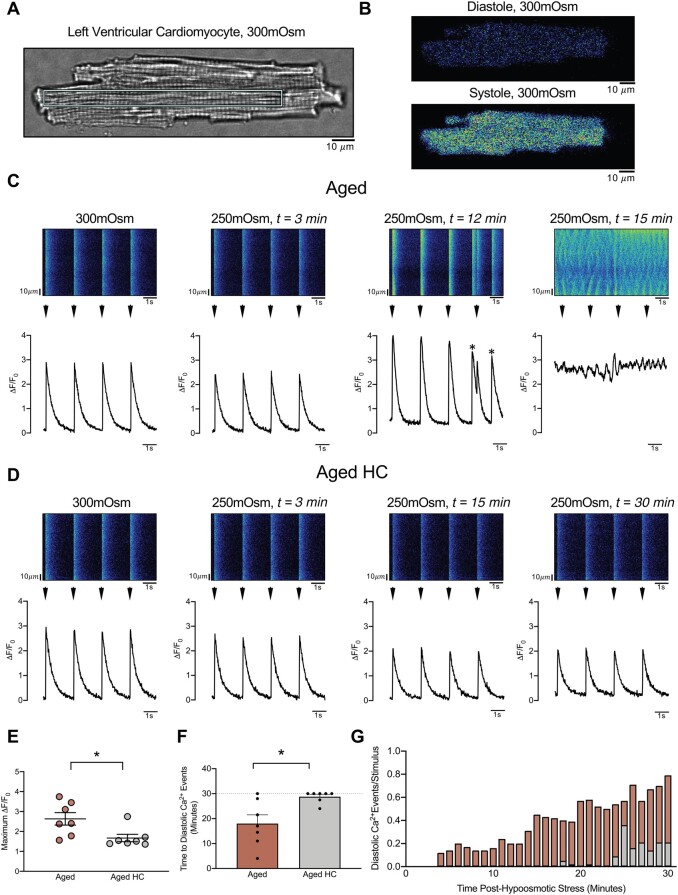

In order to investigate the time course of TRPV4-dependent effects under tightly controlled experimental conditions at the isolated cell level, Ca2+ transient amplitude and incidence of arrhythmic Ca2+ signals were quantified in enzymatically isolated left ventricular cardiomyocytes from Aged and Aged HC prior to (Supplementary material online, Figure S6) and during sustained hypoosmotic stress (Figure 4A–D). Cardiomyocytes from Aged demonstrated increased maximum Ca2+ transient amplitude (ΔF/F0) during hypoosmotic stress compared with Aged HC (Figure 4E). Cardiomyocytes from Aged exhibited an increased incidence and earlier onset of arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ signalling events compared with Aged HC (Figure 4F and G). Aged cardiomyocytes also exhibited increased incidence and earlier onset of arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ signalling events during hypoosmotic stress compared with Young (Supplementary material online, Figure S7A and B).

Figure 4.

Diastolic Ca2+ signals following hypoosmotic stress in cardiomyocytes of aged hearts. (A) Transmitted light image of left ventricular cardiomyocyte isolated from an Aged heart, with cyan rectangle indicating region used for pseudo-line scan images and quantification in panel C. Identical size region in separate cell was used for panel D. (B) Example Fluo-4 fluorescence during diastole (upper) and peak systole (lower) of cardiomyocyte shown in A (300 mOsm/L conditions). (C) Pseudo-line scan images (upper) and ΔF/F0 fluorescence profiles (lower) of cardiomyocyte of Aged prior to (300 mOsm/L) and following sustained hypoosmotic stress (250 mOsm/L) at t = 3 min, t = 12 min, and t = 15 min. Electrical stimuli indicated by arrowheads; spontaneous (non-paced) Ca2+ transients indicated by (*) at t = 12 min. Ca2+ waves unresponsive to pacing shown at t = 15 min. Cell death occurred at t = 16 min (not shown). (D) Pseudo-line scan images (upper) and ΔF/F0 fluorescence profiles (lower) of cardiomyocyte of Aged pre-treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L), prior to (300 mOsm/L) and following sustained hypoosmotic stress (250 mOsm/L) at t = 3 min, t = 15 min, and t = 30 min. Protocol concluded at 30 min with no cell death in Aged HC. Note modest reduction in ΔF/F0 at t = 3 min in both Aged (C) and Aged HC (D) in response to changes in osmotic conditions. (E) Summary data of peak Ca2+ transient amplitude during 30 min of hypoosmotic stress protocol in Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). (F) Time to spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ events in Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). (G) Ratio of spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ events per electrical stimulation with time in Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey). n = 7 cells from N = 7 animals per group. *P = 0.014 Aged vs. Aged HC, paired two-tailed t test (E). *P = 0.023 Aged vs. Aged HC, One-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test (F). Distance scale bars in A–D = 10 µm.

3.4 TRPV4 contributes to arrhythmia following I/R in aged hearts

To examine the role of TRPV4 in ventricular arrhythmia, intracardiac ECG recordings were used to assess the incidence of ventricular premature beats (Figure 5A), salvos of ventricular premature beats, and ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation (Figure 5B) in Aged and Aged HC during reperfusion. Aged demonstrated increased incidence (Figure 5C and D) and earlier onset of ventricular arrhythmia compared with Aged HC (Figure 5E). Specifically, there was an increased incidence of ventricular premature beats and sustained ventricular arrhythmia in Aged during reperfusion (Figure 5D). Aged hearts had an increased incidence of arrhythmia during reperfusion compared with Young (Supplementary material online, Figure S7C).

Figure 5.

TRPV4 contributes to arrhythmia following ischaemia–reperfusion in aged hearts. (A) Example left ventricular APs (upper panel), left-atrial electrocardiogram lead (middle panel), and left ventricular electrocardiogram lead (lower panel) of an Aged heart following I/R. Ventricular premature beat highlighted in pink. Example trace taken 19 min into reperfusion phase. (B) Example combined left-atrial/left ventricular electrocardiogram lead (upper panel) and left ventricular electrocardiogram lead (lower panel) of a separate Aged heart following I/R. Ventricular tachycardia highlighted in red. Example trace taken 11 min into reperfusion phase. (C) Summary data demonstrating percentage of total sampled hearts (5/5 Aged vs. 2/5 Aged HC) exhibiting ventricular arrhythmia or ventricular premature beats following I/R. (D) Pie charts indicating percentage of total minutes with at least one ventricular arrhythmic event in Aged (left) and Aged HC (right). (E) Time to arrhythmia in hearts of Aged (burgundy, N = 5) and Aged pre-treated with the TRPV4 antagonist HC067047 (Aged HC, 1 µmol/L, grey, N = 5, left). Arrhythmia score for Aged (burgundy) and Aged HC (grey) shown in early (0–15 min, middle, N = 5 per group) and later (15–30 min, right, N = 4 Aged and N = 5 Aged HC) reperfusion. In 15–30 min time range one Aged heart exhibited AV block and was excluded from Arrhythmia Score analysis. *P = 0.038 Aged vs. Aged HC, two-tailed Z test of two population proportions (C). *P = 0.003 Aged vs. Aged HC, one-tailed unpaired t test (E, left) *P = 0.02 Aged vs. Aged HC, one-tailed Mann–Whitney test (E, middle).

4. Discussion

4.1 Role of TRPV4 in Ca2+ homoeostasis in the aged heart

As with other TRP channel family members, TRPV4 is generally not considered a critical component of cardiomyocyte ECC. Nevertheless, emerging data indicate that TRPC,13 TRPM,14,22 TRPP,23 TRPA,24 and TRPV15 channel family members can contribute to cardiomyocyte and cardiac contractility. Furthermore, in the chronically stressed or aged myocardium TRP channel expression and/or function is increased, which contributes to pathological Ca2+ handling and adverse cardiac remodelling.21,22,25–27 Consistent with the cardiac consequences of increased cation flux through TRPC and TRPM, our data indicate TRPV4 contributes to pro-arrhythmic Ca2+ handling and electrophysiological derangements in the aged heart following select stimuli. Under normal conditions, TRPV4 activity is modest as shown by minimal differences in RMP (Figure 1) and Ca2+ handling (Figure 3) between Aged and Aged HC. These data are consistent with previous investigations showing limited functional impact of TRPV4 on cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling or ventricular pressure development in the absence of TRPV4 gating stimuli.16,21 However, following global I/R21 or stretch16 TRPV4 Ca2+ entry shifts Ca2+ flux balance towards cellular and SR Ca2+ accumulation with a resulting increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude and hypercontractility. Although initially beneficial for contractility, sustained TRPV4 activation and excessive Ca2+ influx devolves into pathological Ca2+ overload with spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ transients, Ca2+ waves (Figure 4C), and cardiomyocyte damage.16,21,28

4.2 Role of TRPV4 in ventricular arrhythmia following I/R in the aged heart

The formation of a secondary population of highly depolarized cells (i.e. with a mean 10 mV depolarized from the primary mean) in Aged but not Aged HC hearts points towards a TRPV4-dependent contribution to membrane depolarization during early reperfusion. Independent measurements in Aged GCaMP6f hearts revealed a similar time course of changes to Ca2+ signalling in early reperfusion, with an increased dispersion in Ca2+ transient amplitude and incidence of pro-arrhythmic Ca2+ signalling events (Figure 3). Furthermore, using highly controlled experimental conditions in the isolated cell environment, pro-arrhythmic Ca2+ signalling was evident in Aged cardiomyocytes within 30 min of sustained hypoosmotic stress (Figure 4). TRPV4 is a high-flux Ca2+ channel18 and would therefore directly contribute to both membrane depolarization and cellular Ca2+ overload, which promotes Ca2+ cycling instability and pro-arrhythmic delayed after-depolarizations (DADs) via NCX.29,30 Our data also show that, following I/R, depolarized RMP associated with AP alterations including decreased amplitude, slower upstroke velocity, and prolonged AP decay (Figure 2). These electrophysiological changes highlight the complex mechanisms of arrhythmia associated with membrane depolarization.31 Although membrane potential depolarization can lead to depolarization-induced increases in automaticity, it also leads to incomplete Na+ channel recovery from inactivation and decreased availability of Na+ channels. Thus, decreased Na+ channel availability can be pro-arrhythmic as it slows upstroke velocity (Figure 2B), reduces cardiomyocyte excitability, and decreases myocardial conduction velocity.32,33 Decreased upstroke velocity in combination with prolonged AP decay (Figure 2D) will also lengthen action-potential duration, which can lead to early-after-depolarizations (EADs) and arrhythmogenesis.34 Our results also indicated phenotypic dispersion following I/R, and dispersion in both excitability and refractoriness increases arrhythmia vulnerability. TRPV4 contributes to cardiomyocyte damage,21,28 which may further exacerbate membrane depolarization and Ca2+ handling abnormalities. Together, these complex alterations in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling and electrophysiology produce a vicious cycle leading to increased ventricular arrhythmia burden following I/R (Figure 5).

Our data are consistent with TRPV4-dependent effects being additive to other ionic imbalances well described in the scientific literature. Indeed, Aged hearts treated with HC exhibited membrane depolarization during reperfusion compared with baseline conditions (Figure 1F vs. C), and 2/5 of the Aged hearts treated with HC exhibited ventricular premature beats (Figure 5C and D). Importantly, however, TRPV4 antagonism with HC significantly delayed onset of ventricular arrhythmia and decreased severity of arrhythmia (Figure 5E), highlighting the potential therapeutic value in reducing the activity of this specific ionic flux.

4.3 Susceptibility of the aged heart to ventricular arrhythmia

The aged heart is generally intolerant to excessive Ca2+ influx35,36 due to decreased expression and/or function of the SERCA pump37–39 with increased RyR SR Ca2+ leak.40,41 Cellular electrophysiological properties are also altered with age and may include prolongation of the AP.42,43 Cardiomyocytes of aged hearts also have decreased mitochondrial efficiency, impaired ATP generation, and increased oxidative stress. At the organ level, ageing associates with significant structural changes including hypertrophy and fibrosis.44 Together, these alterations decrease the tolerance of the aged myocardium to pathophysiologic Ca2+ stress and create a substrate for arrhythmia. Comparison of Young vs. Aged hearts revealed a number of age-specific findings. There were minimal differences between Young and Aged under baseline conditions. However, following I/R Aged exhibited depolarized RMP (Supplementary material online, Figure S4), increased incidence of arrhythmic Ca2+ signalling (Supplementary material online, Figure S5), and increased incidence of ventricular arrhythmia (Supplementary material online, Figure S7C) vs. Young. Similarly, cardiomyocytes of Aged subjected to hypoosmotic stress exhibited a shorter time to sustained arrhythmic cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signalling vs. Young (Supplementary material online, Figure S7A and B). It is important to note that following I/R, a TRPV4-independent depolarization was apparent vs. baseline conditions in groups with minimal TRPV4 activity (e.g. Young and Aged HC). Such findings are expected based on the well-established contribution of other ionic mechanisms to membrane depolarization following I/R.8 However, taken together with TRPV4 antagonist studies in Aged, the comparison of Young vs. Aged indicates TRPV4 may be a contributing factor to age-dependent cardiac dysfunction following select stimuli including I/R.

4.4 Study limitations

Pharmacological TRPV4 inhibition: This investigation combined cell- and organ-level measurements of Ca2+, cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, and cardiac electrocardiograms with the small-molecule TRPV4 antagonist HC067047. This pharmacological agent is well established in the primary literature as a specific inhibitor of TRPV4 channels. A caveat to interpretation of TRP channel inhibitors is that such approaches may also inhibit the activity of other TRP channel subunits should the functional channel form as a hetero-tetramer. With respect to TRPV4 channels, notable assembly partners include TRPC and TRPP family members.28,45–48

Langendorff heart experimental conditions: The mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmia are complex, and an advantage of the Langendorff heart preparation is that it permits experimental control of many variables that are difficult to control for in vivo.49 However, because these highly controlled experimental conditions do not precisely replicate in vivo conditions they associate with several limitations. For example, it is well established that the isolated perfused Langendorff heart exhibits increased tissue oedema relative to in vivo or to whole-blood perfused models, and Langendorff-perfused hearts demonstrate localized areas of hypoxia due to impaired reactive hyperaemia and vasodilatory signalling with saline perfusion.49,50 Nevertheless, the organ-level I/R injury induced in Langendorff hearts associates with hypoosmotic stress, intracellular acidosis, Ca2+ overload, and cell death comparably to in vivo conditions. Tissue osmolarity was not assessed in isolated hearts during I/R protocols, and future studies are necessary to determine osmotic changes required to activate TRPV4 in the heart following I/R.

5. Conclusions and proposed model

We propose the following model of cardiomyocyte Ca2+ homoeostasis following myocardial I/R: cardiomyocyte anaerobic metabolism results in intracellular acidification and a secondary pH-induced elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ via sequential Na+/H+ (NHE) and Na+/Ca2+ (‘reverse-mode’ NCX) exchange. This increase in intracellular Ca2+ places the cardiomyocyte at risk for Ca2+ overload, which is increased further by TRPV4 channel activation. TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ influx results in depolarizing ICa and elevates diastolic Ca2+ levels. Increased cytosolic Ca2+ favours SERCA-mediated SR Ca2+ uptake, increases SR Ca2+ content, enhances systolic SR Ca2+ release during ECC, and promotes hypercontractility in early reperfusion.21 However, the increased SR Ca2+ also predisposes the cardiomyocyte to pro-arrhythmic diastolic Ca2+ release events (e.g. Ca2+ waves) which are established triggers for DADs.29,30 TRPV4-mediated cellular Ca2+ overload also contributes to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and cellular damage, which may exacerbate membrane depolarization and arrhythmogenesis. In sum, the electrophysiological and Ca2+ handling abnormalities lead to ventricular premature beats (VPBs) and ventricular arrhythmia. This study adds to a rapidly expanding literature in preclinical animal models indicating a role for TRPV4 in cardiac dysfunction following pathological stimuli.16,21 TRPV4 inhibition may therefore represent a potential anti-arrhythmic strategy following myocardial infarction with ageing.

Translational perspective

Aged populations are at high risk for myocardial infarction, I/R injury, and ventricular arrhythmia. The TRPV4 channel contributes to I/R-induced changes in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling and promotes ventricular arrhythmia in the aged mouse heart. Pharmacological TRPV4 inhibition may represent a potential anti-arrhythmic strategy for aged populations following myocardial infarction and I/R.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was included in a doctoral dissertation at the University of Missouri (D. Peana). D. Peana would like to acknowledge the mentoring contributions of Dr William P. Fay, Dr Laurel A. Grisanti, Dr Maike Krenz, and Dr Luis Polo-Parada as doctoral committee members. The authors would also like to thank Michelle Lambert for technical assistance and recognize Dr Steven S. Segal, Dr Michael J. Davis, and Dr Erika M. Boerman for technical advice and use of equipment.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health [Grant numbers F31HL147559 to D.P.; R01HL136292 to T.L.D].

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Eisner DA, Caldwell JL, Kistamás K, Trafford AW.. Calcium and excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Circ Res 2017;121:181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hamilton S, Terentyev D.. Altered intracellular calcium homeostasis and arrhythmogenesis in the aged heart. Int J Mol Sci 2019:20:2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feridooni HA, Dibb KM, Howlett SE.. How cardiomyocyte excitation, calcium release and contraction become altered with age. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015;83:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zaman S, Kovoor P.. Sudden cardiac death early after myocardial infarction: pathogenesis, risk stratification, and primary prevention. Circulation 2014;129:2426–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee KL, Woodlief LH, Topol EJ, Weaver WD, Betriu A, Col J, Simoons M, Aylward P, Van de Werf F, Califf RM.. Predictors of 30-day mortality in the era of reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Results from an international trial of 41,021 patients. GUSTO-I Investigators. Circulation 1995;91:1659–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roger VL. Epidemiology of myocardial infarction. Med Clin North Am 2007;91:537–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ.. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2012;298:229–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy E, Steenbergen C.. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev 2008;88:581–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zima AV, Blatter LA.. Redox regulation of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc Res 2006;71:310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Makarewich CA, Zhang H, Davis J, Correll RN, Trappanese DM, Hoffman NE, Troupes CD, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Madesh M, Chen X, Gao E, Molkentin JD, Houser SR.. Transient receptor potential channels contribute to pathological structural and functional remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2014;115:567–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu X, Eder P, Chang B, Molkentin JD.. TRPC channels are necessary mediators of pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:7000–7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorin C, Vögeli I, Niggli E.. Dystrophic cardiomyopathy: role of TRPV2 channels in stretch-induced cell damage. Cardiovasc Res 2015;106:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doleschal B, Primessnig U, Wölkart G, Wolf S, Schernthaner M, Lichtenegger M, Glasnov TN, Kappe CO, Mayer B, Antoons G, Heinzel F, Poteser M, Groschner K.. TRPC3 contributes to regulation of cardiac contractility and arrhythmogenesis by dynamic interaction with NCX1. Cardiovasc Res 2015;106:163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mathar I, Kecskes M, Van der Mieren G, Jacobs G, Camacho Londoño JE, Uhl S, Flockerzi V, Voets T, Freichel M, Nilius B, Herijgers P, Vennekens R.. Increased β-adrenergic inotropy in ventricular myocardium from Trpm4-/- mice. Circ Res 2014;114:283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubinstein J, Lasko VM, Koch SE, Singh VP, Carreira V, Robbins N, Patel AR, Jiang M, Bidwell P, Kranias EG, Jones WK, Lorenz JN.. Novel role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 in the regulation of cardiac performance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014;306:H574–H584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Veteto AB, Peana D, Lambert MD, McDonald KS, Domeier TL.. TRPV4 contributes to stretch-induced hypercontractility and time-dependent dysfunction in the aged heart. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:1887–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liedtke W, Friedman JM.. Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4-/- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. White JP, Cibelli M, Urban L, Nilius B, McGeown JG, Nagy I.. TRPV4: molecular conductor of a diverse orchestra. Physiol Rev 2016;96:911–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT.. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 2012;336:597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deng Z, Paknejad N, Maksaev G, Sala-Rabanal M, Nichols CG, Hite RK, Yuan P.. Cryo-EM and X-ray structures of TRPV4 reveal insight into ion permeation and gating mechanisms. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018;25:252–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones JL, Peana D, Veteto AB, Lambert MD, Nourian Z, Karasseva NG, Hill MA, Lindman BR, Baines CP, Krenz M, Domeier TL.. TRPV4 increases cardiomyocyte calcium cycling and contractility yet contributes to damage in the aged heart following hypoosmotic stress. Cardiovasc Res 2018,115:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guinamard R, Demion M, Magaud C, Potreau D, Bois P.. Functional expression of the TRPM4 cationic current in ventricular cardiomyocytes from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2006,48:587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuo IY, Kwaczala AT, Nguyen L, Russell KS, Campbell SG, Ehrlich BE.. Decreased polycystin 2 expression alters calcium-contraction coupling and changes β-adrenergic signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:16604–16609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andrei SR, Sinharoy P, Bratz IN, Damron DS.. TRPA1 is functionally co-expressed with TRPV1 in cardiac muscle: co-localization at z-discs, costameres and intercalated discs. Channels (Austin) 2016;10:395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seo K, Rainer PP, Shalkey Hahn V, Lee DI, Jo SH, Andersen A, Liu T, Xu X, Willette RN, Lepore JJ, Marino JP, Birnbaumer L, Schnackenberg CG, Kass DA.. Combined TRPC3 and TRPC6 blockade by selective small-molecule or genetic deletion inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:1551–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iwata Y, Ohtake H, Suzuki O, Matsuda J, Komamura K, Wakabayashi S.. Blockade of sarcolemmal TRPV2 accumulation inhibits progression of dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2013;99:760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koch SE, Mann A, Jones S, Robbins N, Alkhattabi A, Worley MC, Gao X, Lasko-Roiniotis VM, Karani R, Fulford L, Jiang M, Nieman M, Lorenz JN, Rubinstein J.. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 function regulates cardiac hypertrophy via stretch-induced activation. J Hypertens 2017;35:602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu QF, Qian C, Zhao N, Dong Q, Li J, Wang BB, Chen L, Yu L, Han B, Du YM, Liao YH.. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 involves in hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in cardiomyocytes. Cell Death Dis 2017;8:e2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kass RS, Lederer WJ, Tsien RW, Weingart R.. Role of calcium ions in transient inward currents and aftercontractions induced by strophanthidin in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol 1978;281:187–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lederer WJ, Tsien RW.. Transient inward current underlying arrhythmogenic effects of cardiotonic steroids in Purkinje fibres. J Physiol 1976;263:73–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Antzelevitch C, Burashnikov A.. Overview of basic mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmia. Card Electrophysiol Clin 2011;3:23–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Remme CA, Bezzina CR.. Sodium channel (dys)function and cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Ther 2010;28:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1989;321:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weiss JN, Garfinkel A, Karagueuzian HS, Nguyen TP, Olcese R, Chen PS, Qu Z.. Perspective: a dynamics-based classification of ventricular arrhythmias. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015;82:136–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Domeier TL, Roberts CJ, Gibson AK, Hanft LM, McDonald KS, Segal SS.. Dantrolene suppresses spontaneous Ca2+ release without altering excitation-contraction coupling in cardiomyocytes of aged mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014;307:H818–H829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hano O, Bogdanov KY, Sakai M, Danziger RG, Spurgeon HA, Lakatta EG.. Reduced threshold for myocardial cell calcium intolerance in the rat heart with aging. Am J Physiol 1995;269(5 Pt 2):H1607–H1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qin F, Siwik DA, Lancel S, Zhang J, Kuster GM, Luptak I, Wang L, Tong X, Kang YJ, Cohen RA, Colucci WS.. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated SERCA cysteine 674 oxidation contributes to impaired cardiac myocyte relaxation in senescent mouse heart. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Isenberg G, Borschke B, Rueckschloss U.. Ca2+ transients of cardiomyocytes from senescent mice peak late and decay slowly. Cell Calcium 2003;34:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu A, Narayanan N.. Effects of aging on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-cycling proteins and their phosphorylation in rat myocardium. Am J Physiol 1998;275:H2087–H2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grandy SA, Howlett SE.. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling is altered in myocytes from aged male mice but not in cells from aged female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006; 291:H2362–H2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu X, Altschafl BA, Hajjar RJ, Valdivia HH, Schmidt U.. Altered Ca2+ sparks and gating properties of ryanodine receptors in aging cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium 2005;37:583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dibb KM, Rueckschloss U, Eisner DA, Isenberg G, Trafford AW.. Mechanisms underlying enhanced cardiac excitation contraction coupling observed in the senescent sheep myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004;37:1171–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walker KE, Lakatta EG, Houser SR.. Age associated changes in membrane currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 1993;27:1968–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Loffredo FS, Nikolova AP, Pancoast JR, Lee RT.. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: molecular pathways of the aging myocardium. Circ Res 2014;115:97–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liao J, Wu Q, Qian C, Zhao N, Zhao Z, Lu K, Zhang S, Dong Q, Chen L, Li Q, Du Y.. TRPV4 blockade suppresses atrial fibrillation in sterile pericarditis rats. JCI Insight 2020;5:e137528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dong Q, Li J, Wu QF, Zhao N, Qian C, Ding D, Wang BB, Chen L, Guo KF, Fu D, Han B, Liao YH, Du YM.. Blockage of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Sci Rep 2017;7:42678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu Q, Lu K, Zhao Z, Wang B, Liu H, Zhang S, Liao J, Zeng Y, Dong Q, Zhao N, Han B, Du Y.. Blockade of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 enhances antioxidation after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019;2019:7283683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Adapala RK, Kanugula AK, Paruchuri S, Chilian WM, Thodeti CK.. TRPV4 deletion protects heart from myocardial infarction-induced adverse remodeling via modulation of cardiac fibroblast differentiation. Basic Res Cardiol 2020;115:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bell RM, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM.. Retrograde heart perfusion: the Langendorff technique of isolated heart perfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011;50:940–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Giles AV, Sun J, Femnou AN, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Taylor JL, Covian R, Murphy E, Balaban RS.. Paradoxical arteriole constriction compromises cytosolic and mitochondrial oxygen delivery in the isolated saline-perfused heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018;315:H1791–H1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.