Abstract

Over the past decade, the development of next-generation sequencing for human microbiota has led to remarkable discoveries. The characterization of gastric microbiota has enabled the examination of genera associated with several diseases, including gastritis, precancerous lesions, and gastric cancer. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is well known to cause gastric dysbiosis by reducing diversity, because this bacterium is the predominant bacterium. However, as the diseases developed into more severe stages, such as atrophic gastritis, premalignant lesion, and gastric adenocarcinoma, the dominance of H. pylori began to be displaced by other bacteria, including Streptococcus, Prevotella, Achromobacter, Citrobacter, Clostridium, Rhodococcus, Lactobacillus, and Phyllobacterium. Moreover, a massive reduction in H. pylori in cancer sites was observed as compared with noncancer tissue in the same individual. In addition, several cases of H. pylori-negative gastritis were found. Among these individuals, there was an enrichment of Paludibacter, Dialister, Streptococcus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Treponema. These remarkable findings suggest the major role of gastric microbiota in the development of gastroduodenal diseases and led us to the hypothesis that H. pylori might not be the only gastric pathogen. The gastric microbiota point of view of disease development should lead to a more comprehensive consideration of this relationship.

Keywords: Gastric microbiota, Helicobacter pylori, Cancer, Gastric cancer, Gastritis, Precancerous lesion

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases have caused an increasing burden, with more than 80 million deaths worldwide. Diarrheal diseases and cirrhosis are among the top 10 death-causing gastroduodenal diseases in developing and middle- to low-income countries [1]. On the other hand, in developed and high-income countries, GI malignancies are one of the death-causing diseases, of which colon, liver, and gastric cancers are the most prevalent [2]. Gastric cancer is among the five most common digestive cancers worldwide, along with colorectal, pancreatic, and esophageal cancers. Altogether, these cancers are responsible for the deaths of > 365,000 people per year in Europe, accounting for almost one in every three cancer-related deaths [3]. In addition, patients with advanced gastric cancer in Europe had a 5-year survival rate of < 30%. In 2018, the estimated age-standardized incidence of gastric cancer was 15.7 per 100,000 male population and 7.0 per 100,000 female populations worldwide [4]. More than 90% of all gastric cancers are gastric tissue adenocarcinoma, and the remaining are lymphomas or gastric malignancies of the GI stromal tissue [5]. Several factors highly influence the development of these gastroduodenal diseases, including host genetic polymorphisms related to vulnerability and environmental factors associated with diets, lifestyle habits, and infection pathogens, especially Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).

H. pylori is believed to cause several gastroduodenal diseases, including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer diseases, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [6, 7]. H. pylori is estimated to have infected 4.4 billion people worldwide in the general adult population from 1970 to 2016, with the highest incidence in Africa (79.1%), Latin America and the Caribbean (63.4%), and Asia (54.7%) and a lower incidence in Northern America (37.1%) and Oceania (24.4%) [8]. Although it was previously reported that only 1–2% of patients with H. pylori infection developed gastric cancer in Japan and Taiwan [9], the recent consensus and a meta-analysis reported that H. pylori eradication could reduce the incidence of gastric cancer by 0.55-fold (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.42–0.72) [10]. These findings suggest that H. pylori infection still plays a major role in the development of gastric cancer; thus, eradication therapy for H. pylori infection is an effective approach to reducing the burden of gastric cancer.

Although H. pylori infection is highly associated with gastroduodenal diseases, several studies have reported the prevalence of gastritis in the absence of H. pylori infection [11, 12]. Even in more severe conditions such as premalignant or gastric adenocarcinoma, a low abundance of H. pylori was reported [13]. In addition, there has been an increase in the sensitivity of current methods for detecting specific bacterial communities in the microenvironment, and current computational biology can predict the taxonomy associated with certain diseases [14]. These findings have brought about the possibility of discovering other agents responsible for the development of gastroduodenal diseases in conjunction with H. pylori infection. In this review, we discuss the currently known role of gastric microbiota in the development of gastroduodenal diseases, which suggests that H. pylori is not the only agent for the development of gastroduodenal diseases.

Gastric bacterial microbiome profile

The human stomach is a special area in the human GI organ system. It has a unique bacterial community resulting from a combination of gastric acid secretion, mucus thickness, and peristaltic movements [15]. With that combination of gastric physiology, the gastric cavity was believed to be a sterile environment because of its high acidity, which is unsuitable for bacterial colonization [16]; however, several acid-resistant bacteria could live in the stomach mucosa and are derived from the transient bacteria in the mouth and food, including Streptococcus, Neisseria, and Lactobacillus, with concentrations of approximately < 103 colony-forming units/mL [17]. Furthermore, the discovery of H. pylori in 1983 opened the era of the pathogen responsible for gastroduodenal diseases [18].

In recent years, as a result of the introduction of the bacterial 16S rDNA identification technique, molecular technology has undergone rapid development. This approach may prove the existence of a gastric microbial community without the use of any culture technique. Gastric mucosal-associated microbes such as Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and Stomatococcus were discovered in the early phase of molecular method studies [19]. A study conducted in the United States that identified gastric microbial communities in patients with gastric disease found 128 kinds of phylotypes belonging to five major phyla of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria with 1506 types of non-H. pylori bacteria [20]. Another study conducted in Hong Kong with similar gastric conditions showed identification of 1223 non-H. pylori bacteria that could be classified into 133 kinds of phylotypes belonging to eight bacterial phyla [21]. Those studies were conducted in America and Hong Kong but yielded similar bacterial phyla, with five of eight identified phyla in the latter (Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria) the same between different populations. These data suggest the similarity of gastric microbial communities observed from distinct populations. Another study conducted pyrosequencing analyses of gastric mucosa-associated bacteria in six healthy subjects and obtained 262 phylotypes belonging to 13 classes, including some that had not been confirmed by other studies, such as Chlamydia and Cyanobacteria [22]. In general, the human stomach holds a core microbiome. Although the gastric microbiome is highly variable between individuals, recent studies have detected five major phyla in the stomach, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria. The predominant genera in the stomach are Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Rothia, and Haemophilus [23]. However, when interpreting the current findings on the gastric “core microbiome,” caution is necessary, as these findings might be obtained from sequence-based techniques with only limited data on bacterial viability. To confirm the viability of the discovered microbes, further study is necessary.

There are several factors that affect the variability of gastric microbiota, including diet and supplementary nutrient intake, geographic origin, aging, medication (e.g., antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors [PPIs], and H2 antagonists), H. pylori infection, and other systemic diseases [24–27]. The variability in gastric microbial composition could be a normal variation or lead to a dysbiosis. Basically, a dysbiosis is defined as the microbial imbalance in a certain microenvironment [28]. A dysbiosis is usually associated with a certain disorder—either local organ or systemic manifestation. Whether dysbiosis is caused by the disorder (e.g., H. pylori infection, cancers, or autoimmune diseases) or is causing the disorder (e.g., vulnerability to infection, chronic metabolic diseases, and cancers) remains unclear. Accumulated evidence supports the hypothesis that gastric dysbiosis is associated with the development of gastroduodenal diseases [29–31]. These findings led to a new perspective on the gastric microbial environment as a whole system responsible for the pathogenesis of disease.

H. pylori as standalone pathogen and its interaction with gastric microbiota

H. pylori is widely known to be a major risk factor for the development of various gastroduodenal diseases, including chronic gastritis, ulcers, and gastric cancer. H. pylori has been classified as a class I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [32, 33] because of the close relationship between H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer. Worldwide, H. pylori has been associated with at least 90% of all noncardia gastric cancer cases [34]. Based on geographical distribution, a major overlap was observed between H. pylori positivity and the incidence of gastric cancer in various countries worldwide. Because of this major overlap in distribution and the classification of H. pylori as a class I carcinogenic factor, several studies have demonstrated a causal relationship between the presence of H. pylori and the gastric cancer development. A systematic review of 12 studies showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma was threefold higher (95% CI, 2.3–3.8) than that in noninfected individuals. However, when the pooled analysis was restricted to 10 or more years after the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, the prevalence increased by 5.9-fold (95% CI, 3.4–10.3) [35]. These findings provide evidence that links H. pylori infection to gastric cancer.

There is a well-recognized association between H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer. However, the actual pathogenic pathway of H. pylori-inducing gastric cancer has not been completely elucidated with clear evidence of H. pylori-inducing DNA damage and inflammation [36, 37]. Numerous factors affect the development of various diseases after the colonization of H. pylori in the human stomach, including host genetic susceptibility, H. pylori virulence factors, and individual lifestyle and dietary habits. Because to its polymorphism, the genetic susceptibility of the hostis involved in the gastroduodenal disease development and increases the risk of gastric cancer. Many genetic polymorphisms have been reported to be significantly associated with the development of gastric cancer. However, among the best studied are those that encode interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist, anti-inflammatory IL-10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α proinflammatory cytokines, and the IL-17 cytokine family. The association of genetic variability in the promoters or noncoding regions of these genes with increased risk for the development of gastric cancer has been well documented [38–41]. In addition, several gene polymorphisms were reported to be highly associated with the development of atrophic gastritis, such as transforming growth factor-β1, TNF-α, interferon-γ, and IL-6 in H. pylori-negative individuals [42]. In addition to genetic susceptibility, dietary patterns that include a high intake of salt and smoking habits have been reported to increase the odds for the development of gastroduodenal diseases, including gastric cancer. Besides affecting an individual’s susceptibility to gastric cancer, the host’s genetic and habitual routine factors also affect the gastric microbial community. In a study comparing the gastric microbiomes between Indian, USA, Chinese, and Colombian populations, a distinction was observed that separated into three cluster populations, consisting of samples from United States and Colombia, which were formed closely with each other; the Indian samples; and the Chinese samples [43]. In addition, two different populations with distinct risks of gastric cancer in Colombia showed different microbial communities [26]. In Indonesia, which is a large country with various ethnicities, also showed a significantly different gastric microbiome, which might be responsible for the increase in the odds for developing H. pylori infection [27]. When the gastric microbiomes of twins were compared, genetic alteration of gastric microbiota showed no role in the difference. In that study, no signs of increasing coexisting bacterial communities were found in twins when compared with an unrelated person of the same ethnicity [44]. These findings emphasize that the host and population can affect the gastric microbial community via the design of its own core microbiome in each population.

Among the H. pylori virulence factors, CagA is the most documented as associated with disease pathogenesis. It is encoded as part of the cag pathogenicity island, a type IV secretion system playing the role of a syringe that facilitates CagA protein entrance into host cells [45]. In general, a person infected by H. pylori containing CagA will develop greater gastric damage, including gastritis (superficial and atrophic), duodenal ulcers, and gastric carcinogenesis [46]. CagA mainly affects the induction of more severe clinical outcomes via several mechanisms, including a reduction in glycogen synthase kinase–3 activity, failure to maintain organ structure, activation of the ERK pathway, change in cellular polarity, alteration of cell cycles, promotion of cell proliferation, and replacement of gastric epithelial cells into intestine-specific cells [47]. Alongside CagA, another important virulence factor is VacA, which encodes vacuolating cytotoxin and plays a vital role in the survival of H. pylori by inducing the flow of ions and nutrients, altering the integrity of the gastric epithelium [48]. This gene has variable genetic characteristics in several regions, which could be used to stratify the levels of H. pylori virulence [47–49]. In addition, numerous outer membrane proteins were significantly associated with H. pylori virulence. Recent findings showed that Helicobacter outer membrane protein Q (HopQ) interacts with the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule family and enhances the adherence of H. pylori to gastric mucosal cells. In addition to its function of promoting adherence to the host cell, HopQ is also a dependent factor of the T4SS translocating CagA protein in the host cell [50]. The virulence of H. pylori is important not only in the development of mucosal inflammation but also in the alteration of the gastric microbial community. An experiment in an animal model revealed that even though H. pylori in gerbils infected by cagA isogenic mutant had a diversity similar to that in the wild type, its composition was different, suggesting the ability H. pylori to change the microbial community in a cagA-dependent manner [51]. These findings suggest that H. pylori strain-specific virulence genes not only affect its ability to colonize, causing mucosal damage and inducing the secretion of several proinflammatory cytokines, but also altered the gastric microbiota. Considering the many important virulence factors of H. pylori, which other virulence factor is important to the alteration of the gastric microbial community should be identified.

Although H. pylori has been well documented as being closely related to gastroduodenal diseases, not all infected individuals develop cancer or even ulcers. Most cases are gastritis. A recent animal model study investigated whether malignant lesions in rodents actually represented cancer. The lesions were reported as putative malignant lesions instead of proliferative metaplastic or reactive lesions. In addition, experiments conducted with organoids constructed from gastric cancer mouse models failed to induce tumors in a xenograft model, whereas the controls produced tumors [52]. These findings confirmed the complexity of gastric cancer development, which can be related to a specific human–H. pylori genetic mechanism, the possible roles of certain gastric microbial profiles, and many other factors. Although studies are still in the early phase, factors other than non-H. pylori bacteria may be responsible for the development of gastroduodenal diseases.

H. pylori-negative gastritis and its microbial community

Gastritis is defined as inflammation that occurs in the gastric mucosa. It is most commonly observed in the spectrum of gastroduodenal diseases. Histologically, gastritis is divided into two categories, namely, superficial gastritis (nonatrophic) and atrophic gastritis [53]. Superficial gastritis is defined as an inflammation of the gastric mucosa and is evaluated based on the appearance of polymorphonuclear infiltration in acute gastritis and mononuclear infiltration in chronic gastritis. On the other hand, atrophic gastritis is defined as loss of the appropriate glands [54]. Several etiological factors lead to gastritis, including chemical agents (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, dietary factors, alcohol, and bile reflux), physical agents (e.g., radiation), immune-mediated conditions, and infections (e.g., H. pylori, parasites, and viruses) [53]. The most common etiological factor is H. pylori infection. Gastritis the results from H. pylori infection is often chronic, with some cases progressing to atrophic gastritis.

Although in clinical practice, H. pylori has been widely accepted as causing most or all cases of gastritis, some patients still have H. pylori-negative gastritis. This category might be slightly difficult to define because of some limitations in the detection of H. pylori infection from widely available diagnostic modalities. After considering the use of several screening methods for H. pylori, the prevalence of H. pylori-negative gastritis was found in one study to be approximately 21% in the United States [55]. The authors of that study reported that several differential diagnoses could explain their findings, but the observed gastritis was mostly more focal and milder than H. pylori gastritis and tended to be chronic rather than chronic–active or active. Thus, the etiology of the observed gastritis was not clearly determined. In addition, using a similar approach, H. pylori-negative gastritis was also observed in approximately 27% of all cases of gastritis in Indonesia [11]. Because this phenomenon is certainly caused by an agent, the gastric microbiota approach might provide some insight into the associated agent.

Knowing that the 16s rRNA sequence approach will yield more sensitive results, several studies have described the microbial community in patients with gastritis without H. pylori infection. A study conducted in Mongolia consisting of 11 patients with H. pylori-negative gastritis revealed a similar diversity index between these patients and individuals with normal mucosa. With regard to the gastric microbial composition, the relative abundance in the H. pylori-negative group showed a decreased amount Proteobacteria and increments in the Bacteroidetes population with the introduction of Spirochaetes as compared with the healthy group, in which the proportions of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were evenly distributed [56]. Screening for H. pylori noninfection was based on the relative abundance of 2%, which is typically found in H. pylori-negative individuals [57, 58]. By applying similar criteria, a study in Indonesia also reported that Paludibacter sp. bacteria increased the abundance in the H. pylori-negative gastritis patients [27]. These findings suggest that, even in the absence of H. pylori, it is still possible to detect typical gastritis caused by infection and that the gastric microbiota was also altered. Indeed, recent studies describing the microbiota and gastritis especially in the absence of H. pylori are still limited to a cross-sectional design, which still provides two-way hypotheses. Therefore, studies using a more causative design, such as cohort studies, animal studies, or in vitro models, are needed to confirm the role of gastric dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of gastritis.

Lack of H. pylori in premalignancy and adenocarcinoma

Determination of H. pylori infection in clinical practice was based on several diagnostic modalities, including the visualization of H. pylori-like bacteria (spiral shape) from the gastric biopsy, the appearance of H. pylori antibody from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and detection of H. pylori antigen from the stool and/or from urease-based tests [59]. When tested on individuals with gastritis, these diagnostic methodologies have excellent performance, but they are widely reported to have a very low H. pylori infection positivity rate among patients with gastric cancer or in premalignant patients. The positivity rate was even lower than in patients with gastritis and ulcer diseases [60]. Because of the confidence that H. pylori must exist, the most common explanation in those situations relies on the possible “false-negative” result [59–61].

Compared with other diagnostic modalities, the sequence of the 16s rRNA approach showed greater sensitivity. The low prevalence of H. pylori as detected by conventional methodologies is probably due to the dysbiosis caused by the development of disease. After applying H. pylori detection using the next-generation sequencing approach, the lower abundance of H. pylori among gastric cancer and premalignant individuals was reinforced. Among the H. pylori–positive individuals, H. pylori was the most predominant bacteria in the benign condition, such as gastritis and ulcer. However, when it was developed as a premalignancy (e.g., atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia) and gastric cancer, the dysbiosis began to occur, and a large amount of other bacteria colonized the gastric mucosa [13, 62]. One study in Portugal showed that although that individuals with gastric cancer had lower diversity than individuals with chronic gastritis did, the abundance of H. pylori was reduced significantly and was replaced by non-H. pylori Proteobacteria [29]. In addition, among H. pylori-infected individuals with gastric cancer, H. pylori still maintained its dominance; however, it was reduced significantly as the disease progressed to gastric cancer, while the diversity increased [63, 64]. Interestingly, the gastric cancer lesion did not cover the entire gastric cavity, and it is also interesting to observe the different microbial profiles between cancer and normal specimens within the same individual. The gastric normal location showed the highest observed OTU compared with the peri-tumor lesion and the tumor lesion. Although H. pylori still showed the highest abundance across those three locations, it was significantly reduced in the tumor lesion compared with the normal lesion [65]. These results suggest that even though the dysbiosis resulting from disease development led to either a higher or lower diversity index, the abundance of H. pylori was severely reduced, suggesting that the ability of H. pylori to colonize was massively reduced by the arrival of other bacteria, which could allow it to easily stay in more favorable conditions and might promote more severe disease development.

In addition to being affected by external factors, such as lower acidity as well as the attack of other bacteria, the lower abundance of H. pylori is also affected by the H. pylori activity itself. The activity of H. pylori is dependent on its shape, which is known to be spiral or coccoid form. This coccoid form is an inactive state of H. pylori that is affected by several factors, including antibiotic exposure, extreme pH change, and a low amount of metabolic substances [66]. The production of H. pylori urease capability is increased when it lives in a highly acidic environment, a condition that is absent in both cancer and the precancerous state (atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia). This acidic condition allows H. pylori to produce urease and live in the most active and optimal form. When in the less acidic condition, H. pylori adapts and changes its form into a coccoid shape, forming a biofilm [67]. In this state, H. pylori still exists; however, is does not colonize as actively and its biological function is highly reduced. These factors may preclude its identification by several conventional tests. However, there remains a lack of knowledge regarding whether H. pylori, after assuming its coccoid form, could change back into a spiral shape and recover its virulence ability. Further studies determining the factors and mechanisms related to the reversion into a spiral shape and its maximum virulence potential would be of interest.

Are the new candidates the real villain?

The development of gastroduodenal diseases, including gastritis, ulcers, and gastric cancer, is complex. Infection-related gastritis might be involved only in inflammation caused by pathogenic aggression. With regard to ulcers and gastric cancer, the mechanism begins as a complex interaction between host, agent, and environmental factors. Currently, the well-accepted concept of gastric cancer pathogenesis is Correa’s pathway, with confounding factors such as high-salt diets and other carcinogenic substances that promote the carcinogenic pathway [68]. However, investigation of the microbiome in cancer research and findings regarding dysbiosis related to cancer pathogenesis open opportunities for other factors, which are, in this case, other bacterial agents of cancer development.

Studies that identified microbial candidates related to gastritis have mostly included precancerous or gastric cancer conditions. Because it is the mildest disease in the disease spectrum, gastritis was primarily regarded as the control group. An investigation revealed that the dysbiosis related to the incidence of gastritis was mostly caused by H. pylori, because the pathogen was the most abundant and dominant taxon in patients with gastritis [13]. When limited to patients with H. pylori gastritis only, the associated dysbiosis was slightly different. A study in Indonesia that determined the association between non-H. pylori bacteria and gastritis cases showed that the abundance of Paludibacter and Dialister species was significantly increased in infected patients as compared with individuals with healthy gastric mucosa [27]. In addition, the Mongolian population, which has a high incidence of gastric cancer, showed augmentation of dysbiosis by the Streptococcus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Treponema taxa in patients with H. pylori-negative gastritis [56]. These findings suggest potential new candidate pathogens that might be related to the development of gastritis in the absence of H. pylori infection.

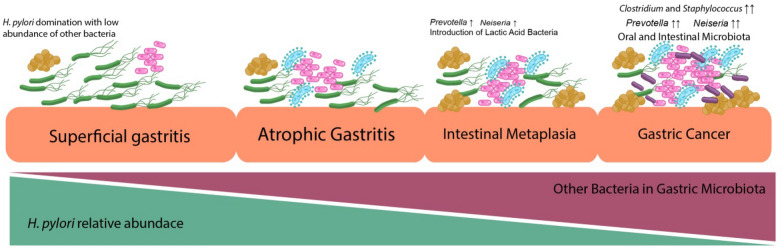

Bacterial candidates related to the development of gastric cancer have been investigated over the past few years in several populations, with intriguing results. In general, the dysbiosis characteristics of gastric microbiota can be used to distinguish gastric cancer from other diseases. Even though gastric dysbiosis occurred with inconsistent shifting diversity index values, a decrease in the relative abundance of H. pylori and incremental changes in the relative abundance of other bacteria have been frequently reported [29, 62, 69] (Fig. 1). Table 1 summarizes the information known regarding gastric dysbiosis associated with gastroduodenal diseases. In gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, the observed microbial community was mainly composed of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria at the phylum level. At the genus level, an increase in relative abundance was reported in Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Haemophilus, and Neisseria [70]. In addition, a significant difference in gastric microbial community was also observed between nonatrophic gastritis and gastric cancer, in which the diversity index was gradually reduced when diseases progressed from gastritis to gastric cancer, with increased abundance of non-H. pylori proteobacteria. In a validation cohort analysis, the populations of several bacteria, including Streptococcus, Prevotella, Achromobacter, Citrobacter, Clostridium, Rhodococcus, Lactobacillus, and Phyllobacterium, were significantly increased in patients with gastric cancer as compared with those with chronic gastritis [29]. At the species level, populations of Prevotella melaninogenica, Streptococcus anginosus, and Propionibacterium acne were increased in tumor tissues, whereas those of H. pylori and Bacteroides uniformis were deceased [65]. In addition, an analysis of gastric microbial communities from different stages of gastric cancer development revealed the importance of Peptostreptococcus stomatis, S. anginosus, Parvimonas micra, Slackia exigua, and Dialister pneumosintes in the progression of gastric cancer, as they were found to coexist from the precancerous stage [30].

Fig. 1.

Association of Helicobacter pylori abundance with the different stages of gastric conditions. The presence of H. pylori was dominant in the superficial gastritis condition; thus, this domination reduced microbial diversity. In atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, the relative abundance of H. pylori began to decrease with the introduction of other bacteria, including the incremental of Prevotella sp. and Neisseria sp. In the gastric cancer condition, H. pylori started to deteriorate with a significantly increased amount other bacteria, including oral cavity microbiota, intestinal microbiota, and lactic acid bacteria

Table 1.

Characteristics of gastric dysbiosis in different gastroduodenal diseases

| Samples and subjects | Characteristics of dysbiosis | References |

|---|---|---|

| 5 Dyspepsia and 10 gastric cancer samples | Domination of different species of the genera Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Veillonella, and Prevotella with low abundance of H. pylori among patients with gastric cancer. | [86] |

| 5 Patients with nonatrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and intestinal-type gastric cancer | Bacterial diversity index ranged from 8 to 57, with a decrease from atrophic gastritis to intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer. Significant decrease in bacterial diversity observed from gastric cancer compared with nonatrophic gastritis. | [87] |

| 10 Patients with chronic gastritis, 11 patients with noncardia gastric cancer, and 10 patients with intestinal metaplasia | Increased relative abundance of Streptococcaceae family with lower relative abundance of Helicobacteraceae family among the gastric cancer group compared with the chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia groups. | [64] |

| 212 Patients with chronic gastritis and 103 patients with gastric cancer enrolled with only 12 patients (6 cancer and 6 chronic gastritis) carried out for microbiome analysis | Five genera bacteria, including Lactobacillus, Escherichia Shigella, Nitrospirae, Burkholderia fungorum, and Lachnospiraceae, were enriched among patients with gastric cancer. The presence of H. pylori heavily changed the structure of the microbiota with a small influence on the relative proportion of other bacteria. | [88] |

| 81 Patients with chronic gastritis and 54 patients with gastric cancer | In general, the gastric carcinoma microbiota was characterized as having reduced microbial diversity with a decreased abundance of Helicobacter and enrichment of other bacteria genera, mostly represented by intestinal commensal bacteria. Specifically, Citrobacter, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, and Rhodococcus were also significantly more abundant in gastric carcinoma. Helicobacter, Neisseria, Prevotella, and Streptococcus were most abundant in the microbiota of patients with chronic gastritis. | [29] |

| 21 Patients with superficial gastritis, 23 patients with atrophic gastritis, 17 patients with intestinal metaplasia, and 20 patients with gastric cancer | In general, there was significant mucosa microbial dysbiosis in the intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer cases compared with cases of superficial gastritis. Several species, including Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Streptococcus anginosus, Parvimonas micra, Slackia exigua, and Dialister pneumosintes, were centralites in the ecological network analysis. | [30] |

| 110 H. pylori-negative individuals and 7 H. pylori–positive patients | Significantly lower diversity among H. pylori–positive patients. A high abundance of Paludibacter sp. and Dialister sp. was observed among individuals with gastric damage. | [27] |

| 24 Controls negative for H. pylori and with nongastritis with 11 additional H. pylori-negative gastritis patients with 40 H. pylori–positive patients | Significantly increased abundance of Streptococcus sp. and Haemophilus parainfluenzae among H. pylori-negative gastritis patients, whereas Treponema sp. was uniquely found in H. pylori-negative gastritis patients based on occurrence. | [56] |

| 120 Patients without cancer (20 normal, 20 gastritis, 40 atrophic gastritis, and 40 intestinal metaplasia) and 48 patients with gastric cancer | The least diversity was seen among the gastritis and atrophic gastritis group. Lactobacilli and Enterococci were the dominant genus in several patients with cancer, especially in the absence of H pylori. In addition, Carnobacterium, Glutamicibacter, Paeniglutamicibacter, Fusobacterium, and Parvimonas were associated with gastric cancer regardless of H pylori infection. | [89] |

| 230 Normal tissues, 247 peritumoral tissues, and 229 tumoral tissues from 276 patients with gastric cancer | The tumor microhabitat showed an increased abundance of Prevotella melaninogenica, Streptococcus anginosus, and Propionibacterium acne with decreased abundance of H. pylori, Prevotella copri, and Bacteroides uniformis. | [65] |

| 288 Controls and 268 patients with gastric cancer | There is a different description of microbial community from different levels. At the species level, the patients with gastric cancer had higher relative abundances of H. pylori, Propionibacterium acnes, and Prevotella copri than the controls did, whereas the relative abundance of Lactococcus lactis was higher in the healthy controls than in the patients. | [71] |

| 36 Paired nontumor tissue and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma samples | Increased relative abundance of Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Haemophilus, and Neisseria among carcinoma tissue compared with nontumor tissue specimens. | [70] |

Gastric dysbiosis not only causes microbial imbalance in the gastric cavity but also leads to functional shifting that might be responsible for the development of gastroduodenal disease. A study conducted in South Korea showed that the associated bacteria in the gastric cancer population compared with controls were H. pylori, Propionibacterium acnes, and Prevotella copri [71]. The overabundance of P. acnes is associated with enhancement of gastric cancer development via the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-15 [72]. It has been strongly suggested that P. copri induces inflammatory conditions that might also be responsible for gastric cancer development [73]. In addition, recent findings showed an increased abundance of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including Streptococcus [30], Lactobacillus [29–31], Bifidobacterium, and Lactococcus, in patients with gastric cancer [74]. LAB have been considered to promote the development of gastric cancer via several mechanisms, including the production of N-nitroso compounds, reactive oxygen species, and anti-H. pylori properties [75]. The most powerful evidence proving the role of LAB in gastric cancer development was obtained from an insulin-gastrin (INS-GAS) transgenic mouse model. In that study, GI intraepithelial neoplasia, which is associated with a strong upregulation of proinflammatory and cancer-related genes, was promoted in male INS-GAS mice colonized with a specific microbiome (including Lactobacillus murinus ASF361, Clostridium ASF356, and Bacteroides ASF519) [76]. In addition, the evidence to date clearly shows that lactate, the metabolite of LABs, can promote inflammation, angiogenesis, and metastasis and regulate the immune response [77], which might influence the outcome of gastric cancer. These findings emphasize the involvement of non-H. pylori bacteria in the development of gastric cancer in some manner.

The future of H. pylori and gastric microbiota

Undeniably, H. pylori is an important factor in the development of gastroduodenal diseases. Since its discovery in 1983, it has remarkably changed the perspective on gastroduodenal diseases, and eradication therapy could prevent the progression of gastric mucosal conditions and carcinogenesis [61–78]. However, because of the wide clinical spectrum of infected individuals, which ranges from superficial gastritis to adenocarcinoma, and from the H. pylori standpoint, different virulence characteristics of H. pylori may exist between the outcomes. The bacterial genome-wide association approach has shown promising outcomes of several single-nucleotide polymorphisms that were highly correlated with and increased the odds for gastric cancer [79]. Although the findings are limited to only one study, this approach described how H. pylori operates as a pathogen of different clinical outcomes. The application of this approach in high-risk gastric cancer populations, such as East Asian populations, is interesting.

An increasing amount of data on relationship between the involvement of gastric microbiota and its associated dysbiosis with the development of gastroduodenal diseases clearly show that H. pylori is not the single responsible pathogen. The gastric microbial community is undeniably involved in the disease pathogenesis via several mechanisms. However, the currently investigated gastric dysbiosis and even the discovered gastric microbial biomarkers are still limited to a two-way association with the disease. The have been no studies investigating whether transferring of the dysbiosis microbial community leads to diseases. Furthermore, no study has used the opposite approach to examine whether the restoration of the gastric microbiota from dysbiosis to an equilibrium state might improve the clinical condition. In addition, current findings are limited to the description of existing bacteria in a particular clinical condition and provide insufficient evidence or a proposed underlying mechanism of the pathogenesis. Therefore, there is a need for further studies examining the restoration of gastric dysbiosis while focusing on culture-omics and the possible mechanism of gastric microbiome-related gastroduodenal diseases.

In addition, a possible connection exists between gastric and gut microbiota in terms of development of disease and H. pylori infection. The long-term use of PPIs has been described to possibly disrupt the gut microbiota into a dysbiotic stage, with PPI being one of the main drugs for dyspepsia therapy and the H. pylori eradication regimen [80, 81]. In addition, one study described that patients with H. pylori infection had an increased diversity and richness of gut microbiota. A reduced number of Bacteroidetes and elevated numbers of Fimicutes and Proteobacter were observed in patients with gastritis as compared with healthy individuals [82]. A cohort study found that changes in gut microbiota in patients after radical distal gastrectomy resulted in an alteration of gut microbiota with increments of Akkermansia sp, Esherichia/Shigella, Lactobacillus, and Dialister [83]. The introduction of Akkermansia might be beneficial because the bacteria introduced in the gastric cancer group were depleted in an animal model experiment [84]. A biomarker discovery analysis yielded a combination of the genera Lachnospira, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Veillonella, and Tyzzerella_3, which showed promising performance in distinguishing patients with gastric cancer from healthy controls. This group of bacteria, specifically Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Lachnospiraceae, increased the number of CD3+T, CD4+T, and natural killer cells [85]. These findings confirmed the involvement of gut microbiota in gastric carcinogenesis. The management of gastroduodenal diseases should also take into consideration the alteration of gut microbiota.

Conclusions

The involvement of H. pylori in the development of gastroduodenal diseases is an indisputable factor. However, recent findings on gastric microbiota in some spectrum diseases showed remarkably smaller populations of H. pylori and increments of other bacteria in gastric carcinogenesis, suggesting that H. pylori may not be the only pathogen responsible for the pathogenesis of the disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, LAW; writing—original draft preparation, LAW, YAAR; writing—review and editing, RV, IDNW, MM; visualization, LAW; supervision, RV, MM, YY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Riset Mandat Top Tier 2021 grant from Universitas Airlangga (771/UN3.15/PT/2021) (MM).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare there is no potential competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yoshio Yamaoka, Email: yyamaoka@oita-u.ac.jp.

Muhammad Miftahussurur, Email: muhammad-m@fk.unair.ac.id.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory; 2016 [cited Nov 11, 2020]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gho/data.

- 2.Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global burden of 5 major types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335–49.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Indonesia source GLOBOCAN 2018. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2019;256:1–2.

- 5.Milosavljević T, Kostić-Milosavljević M, Krstić M, Sokić-Milutinović A. Epidemiological trends in stomach-related diseases. Dig Dis. 2014;32:2136. doi: 10.1159/000357852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:239–48. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629–41. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:4209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liou JM, Malfertheiner P, Lee YC, Sheu BS, Sugano K, Cheng HC, Yeoh KG, Hsu PI, Goh KL, Mahachai V, Gotoda T, Chang WL, Chen MJ, Chiang TH, Chen CC, Wu CY, Leow AH-R, Wu JY, Wu DC, Hong TC, Lu H, Yamaoka Y, Megraud F, Chan FKL, Sung JJ, Lin JT, Graham DY, Wu MS, El-Omar EM. Asian pacific alliance on Helicobacter and Microbiota (APAHAM). Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: the Taipei global consensus. Gut. 2020;69:2093–112. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miftahussurur M, Waskito LA, Syam AF, Nusi IA, Wibawa ID, Rezkitha YA, Siregar G, Yulizal OK, Akil F, Uwan WB, Simanjuntak D. Analysis of risks of gastric cancer by gastric mucosa among Indonesian ethnic groups. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0216670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiota S, Thrift AP, Green L, Shah R, Verstovsek G, Rugge M, Graham DY, El-Serag HB. Clinical manifestations of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1037–46.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira-Marques J, Ferreira RM, Pinto-Ribeiro I, Figueiredo C. Helicobacter pylori infection, the gastric microbiome and gastric cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1149:195–210. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Guryn K, Leone V, Chang EB. Regional diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:314–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nardone G, Compare D. The human gastric microbiota: is it time to rethink the pathogenesis of stomach diseases? U Eur Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:255–60. doi: 10.1177/2050640614566846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Ren R, Yang Y. Mucosa microbiome of gastric lesions: fungi and bacteria interactions. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2020;171:195–213. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monstein HJ, Tiveljung A, Kraft CH, Borch K, Jonasson J. Profiling of bacterial flora in gastric biopsies from patients with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and histologically normal control individuals by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis and 16S rDNA sequence analysis. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:817–22. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-9-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Purdom EA, Francois F, Perez-Perez G, Blaser MJ, Relman DA. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:732–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li XX, Wong GL-H, To KF, Wong VW-S, Lai LH, Chow DK-L, Lau JY-W, Sung JJ-Y, Ding C. Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stearns JC, Lynch MDJ, Senadheera DB, Tenenbaum HC, Goldberg MB, Cvitkovitch DG, Croitoru K, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Neufeld JD. Bacterial biogeography of the human digestive tract. Sci Rep. 2011;1:170. doi: 10.1038/srep00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li TH, Qin Y, Sham PC, Lau KS, Chu KM, Leung WK. Alterations in gastric microbiota after H. pylori eradication and in different histological stages of gastric carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44935. doi: 10.1038/srep44935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cires MJ, Wong X, Carrasco-Pozo C, Gotteland M. The gastrointestinal tract as a key target organ for the health-promoting effects of dietary proanthocyanidins. Front Nutr. 2016;3:57. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2016.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nardone G, Compare D, Rocco A. A microbiota-centric view of diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:298–312. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30108-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang I, Woltemate S, Piazuelo MB, Bravo LE, Yepez MC, Romero-Gallo J, Delgado AG, Wilson KT, Peek RM, Correa P, Josenhans C, Fox JG, Suerbaum S. Different gastric microbiota compositions in two human populations with high and low gastric cancer risk in Colombia [sci rep:18594] Sci Rep. 2016;6:18594. doi: 10.1038/srep18594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miftahussurur M, Waskito LA, El-Serag HB, Ajami NJ, Nusi IA, Syam AF, Matsumoto T, Rezkitha YAA, Doohan D, Fauzia KA, Maimunah U, Sugihartono T, Uchida T, Yamaoka Y. Gastric microbiota and Helicobacter pylori in Indonesian population. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12695. doi: 10.1111/hel.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:219–32. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira RM, Pereira-Marques J, Pinto-Ribeiro I, Costa JL, Carneiro F, MacHado JC, Figueiredo C. Gastric microbial community profiling reveals a dysbiotic cancer-associated microbiota. Gut. 2018;67:226–36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coker OO, Dai Z, Nie Y, Zhao G, Cao L, Nakatsu G, Wu WK, Wong SH, Chen Z, Sung JJY, Yu J. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. 2018;67:1024–32. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gantuya B, Bolor D, Oyuntsetseg K, Erdene-Ochir Y, Sanduijav R, Davaadorj D, Tserentogtokh T, Azzaya D, Uchida T, Matsuhisa T, Yamaoka Y. New observations regarding Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer in Mongolia. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12491. doi: 10.1111/hel.12491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Møller H, Heseltine E, Vainio H. Working group report on schistosomes, liver flukes andHelicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer. Meeting held at IARC, LYON, 7–14 june 1994.19974. 1995;60:587-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.IARC. Infection with Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994:177–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, De Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to pylori. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:487–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb PM, Law M, Varghese C, Forman D. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu L, Xie C. A lucid review of Helicobacter pylori-induced DNA damage in gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12631. doi: 10.1111/hel.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sayed IM, Sahan AZ, Venkova T, Chakraborty A, Mukhopadhyay D, Bimczok D, Beswick EJ, Reyes VE, Pinchuk I, Sahoo D, Ghosh P. Helicobacter pylori infection downregulates the DNA glycosylase NEIL2, resulting in increased genome damage and inflammation in gastric epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:11082–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KEL, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, Lanyon G, Martin M, Fraumeni JF, Rabkin CS. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka S, Nagashima H, Cruz M, Uchida T, Uotani T, Jiménez Abreu JA, Mahachai V, Vilaichone RK, Ratanachu-Ek T, Tshering L, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. LInterleukin-17 C in human Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Infect Immun. 2017;85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Persson C, Canedo P, MacHado JC, El-Omar EM, Forman D. Polymorphisms in inflammatory response genes and their association with gastric cancer: a HuGE systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:259–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado JC, Figueiredo C, Canedo P, Pharoah P, Carvalho R, Nabais S, Castro Alves C, Campos ML, Van Doorn LJ, Caldas C, Seruca R, Carneiro F. Sobrinho-Simões M. A proinflammatory genetic profile increases the risk for chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:364–71. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00899-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Negovan A, Iancu M, Tripon F, Crauciuc A, Mocan S, Bănescu C. Cytokine TGF-β1, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6 gene polymorphisms and localization of premalignant gastric lesions in immunohistochemically H. pylori-negative patients. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:2743–51. doi: 10.7150/ijms.60517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Das A, Pereira V, Saxena S, Ghosh TS, Anbumani D, Bag S, Das B, Nair GB, Abraham P, Mande SS. Gastric microbiome of Indian patients with Helicobacter pylori infection, and their interaction networks. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15438. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15510-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong Q, Xin Y, Wang L, Meng X, Yu X, Lu L, Xuan S. Characterization of gastric microbiota in twins. Curr Microbiol. 2017;74:224–9. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Fischer W. Composition, structure and function of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island encoded type IV secretion system. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:955–65. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baj J, Forma A, Sitarz M, Portincasa P, Garruti G, Krasowska D, Maciejewski R. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors—mechanisms of bacterial pathogenicity in the gastric microenvironment. Cells. 2020;10:1–37. doi: 10.3390/cells10010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ansari S, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori virulence factor cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA)-mediated gastric pathogenicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papini E, Satin B, Norais N, De Bernard M, Telford JL, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. Selective increase of the permeability of polarized epithelial cell monolayers by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:813–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chauhan N, Tay ACY, Marshall BJ, Jain U. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a distinct toxin exerts diverse functionalities in numerous cells: an overview. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12544. doi: 10.1111/hel.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Javaheri A, Kruse T, Moonens K, Mejías-Luque R, Debraekeleer A, Asche CI, Tegtmeyer N, Kalali B, Bach NC, Sieber SA, Hill DJ, Königer V, Hauck CR, Moskalenko R, Haas R, Busch DH, Klaile E, Slevogt H, Schmidt A, Backert S, Remaut H, Singer BB, Gerhard M. Helicobacter pylori adhesin HopQ engages in a virulence-enhancing interaction with human CEACAMs. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16189. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noto JM, Zackular JP, Varga MG, Delgado A, Romero-Gallo J, Scholz MB, Piazuelo MB, Skaar EP, Peek RM. Modification of the gastric mucosal microbiota by a strain-specific Helicobacter pylori oncoprotein and carcinogenic histologic phenotype. mBio. 2019;10. 10.1128/mBio.00955-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Petersen CP, Mills JC, Goldenring JR. Murine models of gastric corpus Preneoplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rugge M, Pennelli G, Pilozzi E, Fassan M, Ingravallo G, Russo VM, Di Mario F. Gruppo Italiano Patologi Apparato Digerente (GIPAD), Società Italiana di Anatomia Patologica e Citopatologia Diagnostica/International Academy of Pathology, Italian division (SIAPEC/IAP). Gastritis: the histology report. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(Suppl 4):373-84. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(11)60593-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. 1996;20:1161-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Nordenstedt H, Graham DY, Kramer JR, Rugge M, Verstovsek G, Fitzgerald S, Alsarraj A, Shaib Y, Velez ME, Abraham N, Anand B, Cole R, El-Serag HB. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:65–71. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gantuya B, El-Serag HB, Matsumoto T, Ajami NJ, Oyuntsetseg K, Azzaya D, Uchida T, Yamaoka Y. Gastric microbiota in Helicobacter pylori-negative and -positive gastritis among high incidence of gastric cancer area. Cancers. 2019;11. 10.3390/cancers11040504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kim J, Kim N, Jo HJ, Park JH, Nam RH, Seok YJ, Kim YR, Kim JS, Kim JM, Kim JM, Lee DH, Jung HC. An appropriate cutoff value for determining the colonization of Helicobacter pylori by the pyrosequencing method: comparison with conventional methods. Helicobacter. 2015;20:370–80. doi: 10.1111/hel.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Perez Perez GI. Is there a role for the non-Helicobacter pylori bacteria in the risk of developing gastric cancer? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Miftahussurur M, Yamaoka Y. Diagnostic methods of Helicobacter pylori infection for epidemiological studies: critical importance of indirect test validation. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:4819423. doi: 10.1155/2016/4819423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsieh YY, Tung SY, Pan HY, Yen CW, Xu HW, Lin YJ, Deng YF, Hsu WT, Wu CS, Li C. Increased abundance of Clostridium and Fusobacterium in gastric microbiota of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2018;8:158. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5191–204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Assumpção PP, Araújo TMT, de Assumpção PB, Barra WF, Khayat AS, Assumpção CB, Ishak G, Nunes DN, Dias-Neto E, Coelho LGV. Suicide journey of H. pylori through gastric carcinogenesis: the role of non-H. pylori microbiome and potential consequences for clinical practice. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1591–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jo HJ, Kim J, Kim N, Park JH, Nam RH, Seok YJ, Kim YR, Kim JS, Kim JM, Kim JM, Lee DH, Jung HC. Analysis of gastric microbiota by pyrosequencing: minor role of bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori in the gastric carcinogenesis. Helicobacter. 2016;21:364–74. doi: 10.1111/hel.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eun CS, Kim BK, Han DS, Kim SY, Kim KM, Choi BY, Song KS, Kim YS, Kim JF. Differences in gastric mucosal microbiota profiling in patients with chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer using pyrosequencing methods. Helicobacter. 2014;19:407–16. doi: 10.1111/hel.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X, Shao L, Liu X, Ji F, Mei Y, Cheng Y, Liu F, Yan C, Li L, Ling Z. Alterations of gastric mucosal microbiota across different stomach microhabitats in a cohort of 276 patients with gastric cancer. EBiomedicine. 2019;40:336–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ierardi E, Losurdo G, Mileti A, Paolillo R, Giorgio F, Principi M, Di Leo A. The puzzle of coccoid forms of Helicobacter pylori: beyond basic science. Antibiot (Basel) 2020;9:1–14. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andersen LP, Rasmussen LA, LP Helicobacter pylori-coccoid forms and biofilm formation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56:112–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miftahussurur M, Yamaoka Y, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori as an oncogenic pathogen, revisited. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2017;19:e4. doi: 10.1017/erm.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park CH, Lee AR, Lee YR, Eun CS, Lee SK, Han DS. Evaluation of gastric microbiome and metagenomic function in patients with intestinal metaplasia using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12547. doi: 10.1111/hel.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shao D, Vogtmann E, Liu A, Qin J, Chen W, Abnet CC, Wei W. Microbial characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma from a high-risk region of China. Cancer. 2019;125:3993–4002. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gunathilake MN, Lee J, Choi IJ, Kim YIl, Ahn Y, Park C, Kim J. Association between the relative abundance of gastric microbiota and the risk of gastric cancer: a case–control study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13589. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50054-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Montalban-Arques A, Wurm P, Trajanoski S, Schauer S, Kienesberger S, Halwachs B, Högenauer C, Langner C, Gorkiewicz G. Propionibacterium acnes overabundance and natural killer group 2 member D system activation in corpus-dominant lymphocytic gastritis. J Pathol. 2016;240:425–36. doi: 10.1002/path.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu J, Xu S, Xiang C, Cao Q, Li Q, Huang J, Shi L, Zhang J, Zhan Z. Tongue coating microbiota community and risk effect on gastric cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9:4039–48. doi: 10.7150/jca.25280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Castaño-Rodríguez N, Goh KL, Fock KM, Mitchell HM, Kaakoush NO. Dysbiosis of the microbiome in gastric carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15957. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vinasco K, Mitchell HM, Kaakoush NO, Castaño-Rodríguez N. Microbial carcinogenesis: lactic acid bacteria in gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1872:188309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lertpiriyapong K, Whary MT, Muthupalani S, Lofgren JL, Gamazon ER, Feng Y, Ge Z, Wang TC, Fox JG. Gastric colonisation with a restricted commensal microbiota replicates the promotion of neoplastic lesions by diverse intestinal microbiota in the Helicobacter pylori INS-GAS mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. 2014;63:54–63. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doherty JR, Cleveland JL. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3685–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI69741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mégraud F, Lehours P, Vale FF. The history of Helicobacter pylori: from phylogeography to paleomicrobiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:922–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berthenet E, Yahara K, Thorell K, Pascoe B, Meric G, Mikhail JM, Engstrand L, Enroth H, Burette A, Megraud F, Varon C, Atherton JC, Smith S, Wilkinson TS, Hitchings MD, Falush D, Sheppard SK. A GWAS on Helicobacter pylori strains points to genetic variants associated with gastric cancer risk. BMC Biol. 2018;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0550-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hojo M, Asahara T, Nagahara A, Takeda T, Matsumoto K, Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, Asaoka D, Takahashi T, Nomoto K, Yamashiro Y, Watanabe S. Gut microbiota composition before and after use of proton pump inhibitors. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2940–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan ME, Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Welter D, Ley RE, Bell JT, Spector TD, Steves CJ. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65:749–56. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gao JJ, Zhang Y, Gerhard M, Mejias-Luque R, Zhang L, Vieth M, Ma JL, Bajbouj M, Suchanek S, Liu WD, Ulm K, Quante M, Li ZX, Zhou T, Schmid R, Classen M, Li WQ, You WC, Pan KF. Association between gut microbiota and Helicobacter pylori-related gastric lesions in a high-risk population of gastric cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:202. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liang W, Yang Y, Wang H, Wang H, Yu X, Lu Y, Shen S, Teng L. Gut microbiota shifts in patients with gastric cancer in perioperative period. Medicine. 2019;98:e16626. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu C, Su Z, Li Y, Li Y, Liu K, Chu F, Liu T, Chen R, Ding X. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota is associated with gastric carcinogenesis in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;126:110036. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qi YF, Sun JN, Ren LF, Cao XL, Dong JH, Tao K, Guan XM, Cui YN, Su W. Intestinal microbiota is altered in patients with gastric cancer from Shanxi Province, China. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1193–203. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5411-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dicksved J, Lindberg M, Rosenquist M, Enroth H, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:509–16. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aviles-Jimenez F, Vazquez-Jimenez F, Medrano-Guzman R, Mantilla A, Torres J. Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4202. doi: 10.1038/srep04202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang L, Zhou J, Xin Y, Geng C, Tian Z, Yu X, Dong Q. Bacterial overgrowth and diversification of microbiota in gastric cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:261–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gantuya B, El Serag HB, Matsumoto T, Ajami NJ, Uchida T, Oyuntsetseg K, Bolor D, Yamaoka Y. Gastric mucosal microbiota in a Mongolian population with gastric cancer and precursor conditions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:770–80. doi: 10.1111/apt.15675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.