Abstract

Background and aims

Postoperative complications are frequent encounters in the patients admitted to postanesthesia care units (PACU). The main aim of this study was to assess the incidence of complications and associated factors among surgical patients admitted in limited‐resource settings of the PACU.

Methods

This is an observational study of 396 surgical patients admitted to PACU. This study was conducted from February 1 to March 30, 2021, in Ethiopia. Study participants' demographics, anesthesia, and surgery‐related parameters, PACU complications, and length of stay in PACU were documented. Multivariate and bivariate logistic regression analyses, the odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. p‐value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

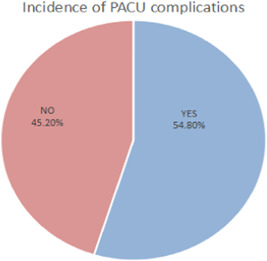

The incidence of complications among surgical patients admitted to PACU was 54.8%. Of these, respiratory‐related complications and postoperative nausea/vomiting were the most common types of PACU complications. Being a female (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.928; 95% CI: 1.899–4.512) was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing PACU complications. Duration of anesthesia >4 h (AOR = 5.406; 95% CI: 2.418–12.088) revealed an increased risk of association with PACU complications. The occurrences of intraoperative complications (AOR = 2.238; 95% CI: 0.991–5.056) during surgery were also associated with PACU complications. Patients who develop PACU complications were strongly associated with length of PACU stay for >4 h (AOR = 2.177; 95% CI: 0.741–6.401).

Conclusion

The identified risk factors for complications in surgical patients admitted to PACU are female sex, longer duration of anesthesia, and intraoperative complications occurrences. Patients who developed complications had a long time of stay in PACU. Based on our findings, we recommend the PACU team needs to develop area‐specific institutional guidelines and protocols to improve the patients' quality of care and outcomes in PACU.

Keywords: anesthesia, postanesthesia care unit, postoperative complications

1. INTRODUCTION

Postoperative complications in patients admitted to postanesthesia care units (PACU) are frequent encounters and approximately account for 4.25%–37.3%, with severity ranging from trivial to critical incidents. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

Complications types may differ in literature for various reasons: however, the most frequently encountered PACU complications were respiratory, cardiovascular, hypothermia, pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and central nervous system‐related adverse events. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

According to the review reports of the Anesthesia Closed Claims Project (CCP) database, the leading cause of anesthesia‐related malpractice claims is the breakdown in communication. 14

The operating room (OR), the PACU, and the intensive care unit (ICU) are particularly vulnerable to communication failures between clinicians.

Ineffective communication in the PACU affects health‐care expenses, length of hospital stays, unplanned ICU admission, mortality, and morbidity. 15 , 16 , 17

The dearth of interventional studies revealed that the implementation of a checklist decreased the overall medical errors and rate of preventable adverse events in PACU. 18 , 19 , 20 Another study also showed that using the postanesthetic care tool (PACT) improves early detection of patients at risk of deterioration, handover to surgical ward nurses, and reduces health care expenses. 21

Therefore, prevention and management strategies based on implementing standardized handover protocols, proper staffing of well‐trained experts, monitoring devices, and infrastructures to improve the quality of patient care should be a crucial part of safe anesthesia in PACU. 22 , 23

In previously published studies, patient, anesthesia, and surgery‐related risk factors have been identified for PACU complications. Further explorations into the etiology of these complications should help for developing strategies to prevent and manage those critical incidents.

The recommendation and guidelines proposed vary considerably between clinical setups in a diverse health context; hence resource‐oriented local solutions to each health system, particularly in resource‐limited settings should be considered. 24 , 25

In a four‐centered study done in Canada, american society of anesthesiology (ASA) physical status, length of anesthesia duration, the occurrence of intraoperative complications, and use of pure spinal or narcotic techniques have been identified as independent single risk factors for PACU complications. 10

On the other hand, the study done in the Philippines revealed that duration of surgery, the occurrence of intraoperative complications, and postoperative complications were identified as significant predictors for the length of stay at PACU. 26

Despite the magnitude of the problem in daily clinical activity, there has been very little or no research examining the incidence and factors associated with PACU complications in sub‐Saharan countries including Ethiopia. The main objective of this study is to evaluate the incidence of complications and associated factors among surgical patients admitted in limited‐resource settings of the PACU.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Study design, settings, and patients

A hospital‐based observational study was employed from February 01 to May 30, 2021, in St. Paul's millennium medical college and teaching hospital, Ethiopia.

This study was reported in line with STROCSS criteria and registered at www.researchregistry.com with research registry UIN: research registry 7482.

The study was approved by the St. Paul's hospital ethical clearance committee and informed written consent was obtained from each study participant and/or legal guardians of underage study participants. Confidentiality was assured throughout the research.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

During the study period, we included all surgical patients who were admitted to PACU for monitoring and stabilization into this study.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Patients transferred directly from the operation theater to an ICU, ward, or outpatient department were excluded.

2.4. Postoperative and postanesthesia care

On the arrival of patients from the OR to the PACU, the responsible nurses applied standard monitoring. Cardiovascular variables (HR, DBP, and SBP) were measured using noninvasive monitoring devices. Respiratory‐related variables (oxygen saturation, breathing pattern, and respiratory rate) were observed using pulse oximetry and clinical observation. Other adverse events (pain, PONV, hypothermia, consciousness level, bleeding from the incision site, and unplanned ICU admission) were monitored.

General anesthesia was induced using either intravenous or inhalational anesthetics agents with muscle relaxants to facilitate tracheal intubation. Inhalational agents and opioids were used for the maintenance of anesthesia and analgesia respectively. After the surgery was completed, reversal agents were administered before extubation and transferred to PACU depending on the patients' physiologic status and the clinical judgment of the responsible senior anesthetist.

In our setup, the overall activities including staffing and infrastructures provided in PACU are suboptimal compared to the standard of care recommended by the American Society of Anesthesiology. 27

The timing of monitoring and documentation depends on the patients' physiologic status and varied among care providers of the unit. Moreover, there are no standardized pain management protocols and discharge criteria. The unit provides minimal to intermediate care for surgical patients who may require close observation of vital signs, temporary noninvasive ventilation, and hemodynamic support. This single unit is equipped with six beds to provide services for all patients regardless of the age group and type of surgery

Nurses are available at all times, and anesthetists/anesthesiologists supervise the overall activities based on patients' conditions. However, the nurses working in our setup didn't receive any kinds of training in PACU. In the institution, there is a lack of a uniform and standardized checklist used for discharging the patients from one department to another; however, each patient admitted to PACU was monitored for a minimum of 1–4 h, and discharged to the respective wards/units.

The primary outcome of our study was to estimate the incidence of any complications in patients admitted to PACU. Complications were categorized into respiratory‐related complications (including desaturation, stridor, and wheezing), cardiovascular (hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, tachycardia, and shock), central nervous system (agitation, deep sedation, seizure, and confusion), and 0ther complications (excessive pain, hypothermia, bleeding from the incision site, reintubation, and unplanned ICU admission). Operational terms of complications are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operational definitions of terms

| Management | ||

|---|---|---|

| Desaturation | Oxygen saturation <94% checked by pulse oximetry | Noninvasive ventilation |

| Airway maneuvers | ||

| Stridor | High‐pitched sound during inspiration | CPAP |

| Wheezing | High‐pitched sound during expiration | |

| Hypertension: | A systolic BP > 160 mmHg for longer than 5 min and/or increased by 20% from baseline | Fluid restriction |

| vasodilators | ||

| Hypotension: | A diastolic BP < 90 mmHg for longer than 5 min and/or decreased by 20% from baseline | Fluid administration |

| Vasopressors | ||

| Tachycardia | Heart rate >100 for adults, different in different pediatric age groups | Observation |

| Bradycardia | Heart rate <60 for adults and less than 80 for children | Oxygen |

| Atropine | ||

| Excessive pain | Moaning or screaming, writhing in pain at any time in PACU or initial care dominated by pain control or requiring more analgesic than ordered. | NSAIDs |

| Acetaminophen | ||

| Weak opioids | ||

| ICU admission | Unplanned requirement of ICU admission before discharge from PACU | ICU care |

| Re‐intubation | Unplanned intubation before discharge from PACU | Treating the underlying causes |

| Hypothermia | A temperature <36.5℃ | Cooling measures |

| PONV | Nausea and/vomiting during PACU stay | Fluid |

| Metoclopramide | ||

| Intraoperative complications | A patient who developed any cardiovascular, and/or respiratory adverse events (laryngospasm and/or bronchospasm and/or aspiration) and/or significant blood loss. | Optimizing and treating the underlying causes |

| Significant blood loss | A total blood loss >30% of an estimated blood volume during the intraoperative period | Blood transfusion |

Abbreviations: CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; PACU, postanesthesia care unit; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting.

2.5. Sample size and sampling techniques

We calculated the sample size from the primary outcome variable by using single population formula, which is the incidence of PACU complications. Since there is no preliminary data in the study setting p = 0.5 (prevalence of PACU complications 50%) was taken for the calculation to get the largest sample size, 95% confidence interval, and 5% margin of error giving us 384 study subjects. Since the studied population in a year is less than 10,000, the corrected sample size formula was used, and the final sample size becomes 396 by adding a 10% attrition rate. A convenient sampling technique was used to select the study participants.

2.6. Data collection techniques

We collected our data using a pretested questionnaire by trained 4 PACU nurses and anesthetists data collectors. Demographics and preexisting co‐morbidity variables were documented from the patient medical chart. The occurrences of complications and length of PACU stay were recorded from bedside observation, monitoring devices, and documentation of attending nurses until discharging patients to the respective department. The data were cross‐checked by the principal investigator to ensure accuracy and completeness.

2.7. Data analysis

We entered and analyzed data using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26). We used descriptive statistics to summarize the frequency table, and the standardized residual tests to test the outlier data. Multicollinearity was checked by VIF, tolerance, and confidence index. All independent variables were analyzed using bivariate analysis, and the variables that had an association at a p‐value less than or equal to 25 were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model, and p‐value < 0.05 was considered to be a risk factor for PACU complications during the postoperative period in this study. The results of associated variables were presented as a frequency table, crude, and adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval. Hosmer Lemeshow test was used to check the goodness of the model, and the model was the best fit with a p‐value of 689.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and pre‐existing comorbidity characteristics of the study participants

A total of 396 patients admitted to PACU during the study period were enrolled for final analysis. Of these, 204 (51.51%) were males and females accounted for 192 (48.49%). The mean (SD) of the study participants was 38.99 (19.47) with a range of 4 months to 96 years. Regarding the ASA physical status, the majority 305 (77.02%) of patients were ASA class I followed by ASA class II 69 (17.42%) and ≥ASA class III 22 (5.56%). Assessment of preoperative comorbidity revealed that only 94 (23.74%) of patients had pre‐existing comorbidity as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

| Variables | Category | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 204 | 51.51 |

| Female | 196 | 48.49 | |

| Age group | ≤5 | 36 | 9.1 |

| 6–15 | 15 | 3.8 | |

| 16–29 | 101 | 25.5 | |

| 30–45 | 79 | 19.95 | |

| 46–60 | 127 | 32.05 | |

| >60 | 38 | 9.6 | |

| ASA classification | 1 | 305 | 77.02 |

| 2 | 69 | 17.42 | |

| ≥3 | 22 | 5.56 | |

| Pre‐existing comorbidity | None | 302 | 76.26 |

| Respiratory | 9 | 2.27 | |

| cardio‐vascular system | 22 | 5.55 | |

| Neurological | 3 | 0.76 | |

| Endocrine (DM) | 17 | 4.3 | |

| reto‐viral infection | 24 | 6.06 | |

| >1 Comorbidity | 19 | 4.8 |

3.2. Anesthesia‐related characteristics of study participants

Of all study participants, 296 (74.75%) had received general anesthesia. With regard to the level of anesthesia care providers, 246(62.12%) of the procedures have been performed by residents and anesthetists 150 (37.88%). Cases with intraoperative complications were observed only in 35 (8.34%) patients. The mean (SD) duration of anesthesia and duration of stay in the PACU was 157.88 (86.87) and 170.74 (38.49), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anesthesia‐related characteristics of study participants

| Types of anesthesia | General | 296 | 74.75 |

| Regional | 60 | 15.15 | |

| Combined | 24 | 6.06 | |

| monitored anesthesia care | 16 | 4.04 | |

| Level of anesthetist | Anesthetist | 150 | 37.88 |

| Resident | 246 | 62.12 | |

| Anesthesia duration (hours) | 0–2 h | 172 | 43.43 |

| 2–3 h | 106 | 26.77 | |

| 3–4 h | 77 | 19.45 | |

| >4 h | 41 | 10.35 | |

| Intraoperative complication presence | Yes | 35 | 8.84 |

| No | 361 | 91.16 | |

| Duration of stay in the postanesthesia care unit | 60–120 min | 172 | 43.43 |

| 120–180 min | 106 | 26.77 | |

| 180–240 min | 77 | 19.45 | |

| >240 min | 41 | 10.35 |

3.3. Surgery‐related characteristics of study participants

The majority of 298 (75.25%) types of surgery were elective, and the rest 98 (24.75) were emergency. Regards to surgical indication by specialty, most of them were general surgery 147 (37.12%), gynecology 44 (11.12%), orthopedics 43 (10.86%), and variety of pediatrics surgery 41 (10.35%). The majority of the surgical procedures have been done in supine position 359 (90.66%). More than two‐thirds of 304 (76.76%) surgical duration were between 0 and 3 h (Table 4).

Table 4.

Surgery‐related characteristics of the study participants

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of surgery | Elective | 298 | 75.25 |

| Emergency | 98 | 24.75 | |

| Surgical indication by specialty | General surgery | 147 | 37.12 |

| Gynecology | 44 | 11.12 | |

| Orthopedics | 43 | 10.86 | |

| Pediatric surgery | 41 | 10.35 | |

| Cardiothoracic | 15 | 3.78 | |

| Hepato‐biliary | 17 | 4.3 | |

| Uro‐surgery | 32 | 8.08 | |

| Neurosurgery | 29 | 7.32 | |

| ENT | 28 | 7.07 | |

| Position during surgery | Supine | 359 | 90.66 |

| Prone | 13 | 3.28 | |

| Lateral | 11 | 2.78 | |

| Lithotomy | 13 | 3.28 | |

| Surgical time (hours) | 0–2 h | 144 | 36.36 |

| 2–3 h | 160 | 40.4 | |

| 3–4 h | 60 | 15.15 | |

| >4 h | 32 | 8.09 |

3.4. Incidence of PACU complications

Of the total study participants admitted to PACU, the total incidence of PACU complications was 217 (54.8%) as shown in Figure 1. Among those, 58 (14.64%) patients had developed more than one complication and only 14 (3.53%) of them had required unplanned reintubation and ICU admission.

Figure 1.

Incidence of complications among surgical patients admitted to postanesthesia care units.

3.5. Types of PACU complications

With regard to the types of PACU complications, the majority of patients were developed respiratory and airway related adverse events 94 (43.32%) followed by PONV 48 (22.12%), and cardiovascular related adverse events 41 (18.9%) as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Types of postanesthesia care unit complications of study participants

| Types of complications | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Airway and respiratory | 94 | 43.32 |

| cardio‐vascular system | 41 | 18.9 |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 48 | 22.12 |

| central nervous system | 19 | 8.76 |

| Other complications | 15 | 6.9 |

3.6. Patient, anesthesia, and surgery‐related factors associated with PACU complications among study participants

The results from multiple logistic regressions showed that female sex, prolonged duration of anesthesia, intraoperative complications presence, and length of stay in PACU were found to be statistically significant with PACU complications.

Female sex (AOR = 2.570; 95% CI: 1.621–4.075), duration of anesthesia greater than 4 h (AOR = 5.406; 95% CI: 2.418–12.088), intraoperative complications occurrences (AOR = 2.238; 95% CI: 0.991–5.056) and duration of PACU stay > hours 4.538 (2.089–9.857) had shown an association with postoperative complications in PACU (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showing factors associated with PACU complications

| Variables | Category | PACU complication | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| Sex | Male | 117 | 87 | 1 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 62 | 130 | 2.820 (1.870–4.251) | 2.570 (1.621–4.075)*** | ||

| Duration of anesthesia hours | 0–2 | 101 | 69 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2–3 | 42 | 66 | 2.3 (1.404–3.767) | 2.226 (1.330–3.725)** | 0.002 | |

| 3–4 | 26 | 51 | 2.871 (1.635–5.041) | 3.050 (1.690–5.505)*** | <0.001 | |

| >4 | 10 | 31 | 4.508 (2.089–9.857) | 5.406 (2.418–12.088)*** | <0.001 | |

| Intraoperative complication | No | 9 | 26 | 1 | 1 | 0.025 |

| Yes | 170 | 191 | 2.571 (1.172–5.641) | 2.238 (0.991–5.056)** | ||

| Duration of PACU stay hours | 1–2 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2–3 | 80 | 74 | 2.300 (1.404–3.767) | 1.226 (0.426–3.527) | 0.242 | |

| 3–4 | 44 | 62 | 2.871 (1.635–5.041) | 1.898 (0.645–5.584) | 0.054 | |

| >4 | 43 | 75 | 4.538 (2.089–9.857) | 2.177 (0.741–6.401)** | 0.020 | |

Note: Statistically significant

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odd ratio; PACU, postanesthesia care unit.

p < 0.05

p < 0.001.

4. DISCUSSION

The infrastructure and staffing of PACU in low‐income countries are often substandard; with less equipped monitoring, a limited number of beds, a lack of locally adopted protocols, and trained health care providers. These limitations significantly impact the clinical outcomes of the early postoperative period. With such resource‐constrained environments, standardizing the service became even more crucial to improve the quality of care. 28 , 29

Certainly, it is desirable to adopt prediction tools in surgical patients, when the risk of postoperative complications is high, but, staffing and medical resources of a particular clinical setup should be considered. Developing risk prediction tools is not enough, though. It can be used as a baseline source to develop evidence‐based clinical pathways. Implementing and evaluating the adopted clinical pathway to improve the quality of postoperative care is the key. 15

This study aimed to evaluate the incidence of complications and associated factors among surgical patients admitted in limited‐resource settings of the PACU.

In our resource‐constrained setup, there is an inconsistently predefined protocol for management and discharge criteria of patients, that is, no or substandard clinical pathways. Thus, this study can serve to identify problems and find solutions for countries with limited setup.

Despite most of the patients being ASA class I without comorbidity, our study has revealed that the overall incidence of postoperative complications in PACU among patients undergoing surgery is 54.6%. In contradiction to our finding, previous studies conducted in different countries using a varied standard of care had reported that only (4.25%–37.3%) of surgical patients had developed PACU complications. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4

This significant discrepancy could be explained by the fact that in our study area there are traditional and inconsistent handover trends, 16 limited nursing staff compared to workload intensity, 30 and medical resources constraints to provide standardized care. By implementing cost‐effective clinical pathways in routine practice, the early identification of structural problems may significantly improve patient care and postoperative outcome.

Of all PACU complications, the majorities (17.7%) were respiratory and airway‐related complications. These findings are consistent with previous studies. 5 , 6 , 7 The possible explanation for the high rate of respiratory complications is due to hypoventilation caused by hypo‐active emergence and residual effects of muscle relaxant agents, as most of the participants had undergone surgery with general anesthesia. 4 , 31 In disagreement with our finding, other studies 8 , 9 reported that the majority of PACU complications were cardiovascular‐related. In another study, PONV, 10 , 31 central nervous system, 2 , 11 and pain 12 , 13 were reported as the most common PACU complications.

Depending upon the severity of complications, poorly managed events in the early postoperative period can diversely impact the clinical outcome; which may increase the length of hospital stays, unplanned ICU admission, reintubation, and even death. 15 , 16 , 17 Therefore, prevention of critical incidents and provision of evidence‐based care should be an integral role of standard patient care in the PACU.

Our study found that female sex, duration of anesthesia, presence of intraoperative complications, and duration of stay in PACU were factors associated with PACU complications.

Female patients were more at risk of developing complications than their male counterparts (AOR = 2.570; 95% CI: 1.621–4.075). Similarly, other studies 12 , 32 , 33 , 34 also found that being a female is a risk factor to develop PACU complications. This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that: the higher incidence of PONV 35 and postoperative pain 36 in female patients attributed to the high rate of PACU complications. Provisions of preemptive analgesia and PONV prophylaxis for female patients are crucial to improving postoperative outcomes. 37 , 38

Another factor associated with PACU complications in the present study was the duration of anesthesia. Duration of anesthesia >4 h (AOR = 5.406; 95% CI: 2.418–12.088) and 2–3 h (AOR = 3.050 95% CI: 1.690–5.505) had five‐ and three‐fold risk for developing PACU complications compared to the duration of anesthesia less than or equal to 2 h, respectively. This result is consistent with other studies 6 , 10 , 32 , 39 that reported the risk of developing PACU complications is higher in patients with prolonged duration of anesthesia.

The intraoperative complications presence (AOR = 2.238; 95% CI: 0.991–5.056) was a risk factor to predict PACU complications, as revealed by the present study.

Different risk factors identified as challenging preoperatively might be strongly associated with intraoperative complications. The occurrences of intraoperative complications increased the likelihood of postoperative morbidity and prolonged hospital stay (6, 7, and 10). Therefore, the identification of risk factors for perioperative complications and adequate optimization should be an integral part of anesthetic management. 40

Inconsistent with our findings, other studies revealed that types of anesthesia, the urgency of surgery, ASA class, preexisting disease, and other factors are associated with PACU complications. The standard of clinical setup, types of surgery performed, level of expertise, available medications, sustainable training, and attention given to the health sector might contribute to the dissimilarity of the findings.

The length of stay in PACU greater than 4 h (AOR = 4.538; 95% CI: 2.089–9.857) were strongly correlated with the incidence of PACU complication, our study also observed that patients who encountered PACU complications significantly required a prolonged duration of stay than initially planned compared to patients without complications. 9 , 26

4.1. The limitation of the study

Our study had some limitations. First, we conducted our study in resource‐limited settings of a single‐center hospital which is difficult to conclude the overall features of the country. Second, this study identified complications that exclusively occurred in PACU and failed to detect any types of postoperative complications experienced by patients after being discharged from PACU. Furthermore, we included mixed population and diversified age groups which might affect the confounding factors.

4.2. Strength of the study

This study is prospective and observational used as a primary source of data.

5. CONCLUSION

The incidence of PACU complications is 54.6% in the present study which is higher than in prior studies done in different countries. Female sex, intraoperative complications occurrence, and duration of anesthesia are found to be independent risk factors for developing PACU complications. Based on the present study's findings, we recommend the PACU team needs to develop area‐specific institutional guidelines and protocols to improve the patient outcomes in PACU. We also recommend the researcher conduct a multi‐centered study on a larger group of patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bisrat Abebe: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Natnael Kifle: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Muluken Gunta: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Temesgen Tantu: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Mekete Wondwosen: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Dereje Zewdu: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

Dereje Zewdu affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge St. Paul's hospital millennium medical college for giving us ethical clearance. Our thanks also go to data collectors and study participants for their invaluable support.

Abebe B, Kifle N, Gunta M, Tantu T, Wondwosen M, Zewdu D. Incidence and factors associated with post‐anesthesia care unit complications in resource‐limited settings: an observational study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022;5:e649. 10.1002/hsr2.649

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Faraj JH, Vegesna AR, Mudali IN, et al. Survey and management of anesthesia‐related complications in PACU. Qatar Med J. 2013;2012(2):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zelcer J, Wells DG. Anesthetic‐related recovery room complications. Anes Inten Care. 1987;15(2):168‐174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belcher AW, Leung S, Cohen B, et al. Incidence of complications in the post‐anesthesia care unit and associated healthcare utilization in patients undergoing non‐cardiac surgery requiring neuromuscular blockade 2005–2013: a single‐center study. J Clin Anesth. 2017;43:33‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kluger MT, Bullock MF. Recovery room incidents: a review of 419 reports from the Anaesthetic Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS). Anesthesia. 2002;57(11):1060‐1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van der Walt JH, Webb RK, Osborne GA, Morgan C, Mackay P. The Australian incident monitoring study. Recovery room incidents in the first 2000 incident reports. Anes Inten Care. 1993;21(5):650‐652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tarrac SE. A description of intraoperative and postanesthesia complication rates. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21(2):88‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salman MJ, Asfarn NS. Recovery room incidents. Basrah J Surg. 2007;13(1):1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hajnour MS, Tan PS, Eldawlatly A, Alzahrani TA, Ahmed AE, Khokhar RS. Adverse events survey in the postanesthetic care unit in a teaching hospital. Saudi J Laparos. 2016;1(1):13. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruins SD, Leong PM, Ng SY. Retrospective review of critical incidents in the post‐anesthesia care unit at a major tertiary hospital. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(8):497‐501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duncan PG, Cohen MM, Tweed WA, et al. The Canadian four‐center study of anesthetic outcomes: III. Are anesthetic complications predictable in day surgical practice? Can J Anes. 1992;39(5):440‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nourizadeh M, Rostami M, Saeedi F, Niknejad H, Tatari M. Evaluation of the incidence of post‐anesthetic complications in recovery unit of 9‐day hospital in torbat‐e‐heydaryieh in 2016. Modern Care J. 2018;15(2):e74011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poorsheykhian M, Emami Sigaroodi A, Kazamnejad E, Raoof M. Incidence of post general anesthesia complications in the recovery room. J Guil Univ Med Sci. 2012;21(82):8‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Popov DC, Peniche AD. Nurse interventions and the complications in the post‐anesthesia recovery room. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2009;43:953‐961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Douglas RN, Stephens LS, Posner KL, et al. Communication failures contributing to patient injury in anesthesia malpractice claims. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127(3):470‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eichenberger AS, Haller G, Cheseaux N, Lechappe V, Garnerin P, Walder B. A clinical pathway in a post‐anesthesia care unit to reduce the length of stay, mortality, and unplanned intensive care unit admission. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(12):859‐866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagpal K, Arora S, Abboudi M, et al. Postoperative handover: problems, pitfalls, and prevention of error. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):171‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang CC, Chuang YF, Chen PE, Tao P, Tung TH, Chien CW. Effect of postoperative adverse events on hospitalization expenditures and length of stay among surgery patients in taiwan: a nationwide population‐based case‐control study. Front Med. 2021;8:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bigham MT, Logsdon TR, Manicone PE, et al. Decreasing handoff‐related care failures in children's hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e572‐e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Starmer AJ, O'Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I‐PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):876‐884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boat AC, Spaeth JP. Handoff checklists improve the reliability of patient handoffs in the operating room and postanesthesia care unit. Pediat Anes. 2013;7:647‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Street M, Phillips NM, Kent B, Colgan S, Mohebbi M. Minimising post‐operative risk using a Post‐Anaesthetic Care Tool (PACT): protocol for a prospective observational study and cost‐effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mamaril ME, Sullivan E, Clifford TL, Newhouse R, Windle PE. Safe staffing for the post‐anesthesia care unit: weighing the evidence and identifying the gaps. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007;22(6):393‐399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chekol B, Eshetie D, Temesgen N. Assessment of staffing and service provision in the post‐anesthesia care unit of hospitals found in Amhara regional state, 2020. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2021;13:125‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Florman JE, Cushing D, Keller LA, Rughani AI. A protocol for postoperative admission of elective craniotomy patients to a non‐ICU or step‐down setting. J Neurosurg. 2017;127(6):1392‐1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Souza Gutierrez C, Bottega K, de Jezus Castro SM, et al. The impact of the incorporation of a feasible postoperative mortality model at the Post‐Anaesthetic Care Unit (PACU) on postoperative clinical deterioration: a pragmatic trial with 5,353 patients. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0257941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aspi MT, Ko‐Villa E. The use of determinants of length of stay in the post‐anesthesia care unit (PACU) at the Philippine General Hospital among postoperative patients who underwent elective surgeries to create a predictive model for PACU length of stay. Acta Med Phil. 2020;54(5):490‐497. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Updated by the Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Task Force on Postanesthetic Care , Silverstein JH, Chung FF, Connis RT, et al. original Guidelines were developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Practice guidelines for postanesthetic care: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):291‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Epiu I, Tindimwebwa JV, Mijumbi C, et al. Challenges of anesthesia in low‐and middle‐income countries: a cross‐sectional survey of access to safe obstetric anesthesia in East Africa. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(1):290‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hadler RA, Chawla S, Stewart BT, McCunn MC, Kushner AL. Anesthesia care capacity at health facilities in 22 low‐ and middle‐income countries. World J Surg. 2016;40(5):1025‐1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kiekkas P, Tsekoura V, Fligou F, Tzenalis A, Michalopoulos E, Voyagis G. Missed nursing care in the postanesthesia care unit: a cross‐sectional study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36(3):232‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xará D, Santos A, Abelha F. Adverse respiratory events in a post‐anesthesia care unit. Archivos de Bronconeumología. 2015;51(2):69‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Quintero‐Cifuentes IF, Pérez‐López D, Victoria‐Cuellar DF, et al. Incidence of early postanesthetic hypoxemia in the postanesthetic care unit and related factors. Colomb J Anestesiol. 2018;46(4):309‐316. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tennant I, Augier R, Crawford‐Sykes A, et al. Minor postoperative complications related to anesthesia in elective gynecological and orthopedic surgical patients at a teaching hospital in Kingston, Jamaica. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2012;62:193‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myles PS, Hunt JO, Moloney JT. Postoperative ‘minor’ complications: comparison between men and women. Anaesthesia. 1997;52(4):300‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stadler M, Bardiau F, Seidel L, Albert A, Boogaerts JG. The difference in risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2003;98(1):46‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kanaan SF, Melton BL, Waitman LR, Simpson MH, Sharma NK. The effect of age and gender on acute postoperative pain and function following lumbar spine surgeries. Physiother Res Int. 2021;26(2):e1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aga A, Abrar M, Ashebir Z, Seifu A, Zewdu D, Teshome D. The use of perineural dexamethasone and transverse abdominal plane block for postoperative analgesia in cesarean section operations under spinal anesthesia: an observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zewdu D, Tantu T, Olana M, Teshome D. Effectiveness of wound site infiltration for parturients undergoing elective cesarean section in an Ethiopian hospital: a prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg. 2021;64:102255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Phan K, Kim JS, Kim JH, et al. Anesthesia duration as an independent risk factor for early postoperative complications in adults undergoing elective ACDF. Glob Spine J. 2017;7(8):727‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in‐hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1368‐1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.