Abstract

Background

Diarrhea is the second most common cause of death in under-five children. Fluid and food replacement during diarrheal episodes have a paramount effect to avert morbidity and mortality. However, there is limited information about feeding practices. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of drinking or eating more and associated factors during diarrhea among under-five children in East Africa using demographic and health surveys (DHSs).

Methods

Secondary data analysis was done on DHSs 2008 to 2018 in 12 East African Countries. Total weighted samples of 20,559 mothers with their under-five children were included. Data cleaning, coding, and analysis were performed using Stata 16. Multilevel binary logistic regression were performed to identify factors associated with drinking or eating more during diarrheal episodes. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% CI, and p-value < 0.05 were used to declare statistical significance.

Results

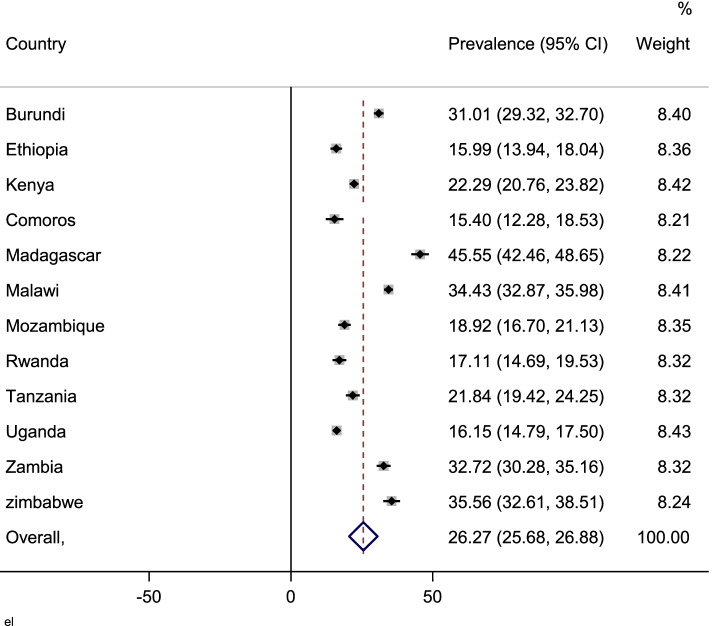

Prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrhea disease in East Africa was 26.27%(95% CI: 25.68–26.88). Mothers age > 35 years (AOR: 1.14, 95% CI: (1.03, 1.26), mothers primary education (AOR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06,1.28), secondary education (AOR: 1.43,95% CI: 1.27,1.61), and higher education (AOR: 1.42,95% CI: 1.11,1.81), occupation of mothers (agriculture, AOR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.3–3.6), sales and services, AOR = 1.20, CI:1.07,1.34), manual, AOR =1.28,95% CI: 1.11,1.44), children age 1–2 years (AOR =1.34,95% CI: 1.22,1.46) and 3–4 years (AOR =1.36,95% CI: 1.20,1.55), four and more antenatal visits (AOR: 1.14,95% CI: 1.03,1.27), rich wealth status (AOR:1.27,95% CI: 1.16,1.40), birth in health facility (AOR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.10, 1.30) and visit health facility (AOR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.22) were associated with drinking or eating more.

Conclusion

The prevalence of drinking or eating more is low in East Africa. Maternal age, occupation, antenatal care visit, marital status, educational status, wealth status, place of delivery, visiting health facility, and child age were significantly associated with drinking or eating more during diarrheal episodes. Health policy and programs should focus on educating mothers, improving the household wealth status, encouraging women to contact health facilities for better feeding practices of children during diarrheal episodes.

Keywords: Prevalence, Drinking or eating more, Children, East Africa

Background

According to the world health organization (WHO), diarrhea is the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day or more frequent passage than normal for the child and is the second most killer, preceded by pneumonia, of children under the age of five [1, 2]. Every year approximately 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrhea are detected and are responsible for the killing of around 525,000 children worldwide [1], of which 90% of death is in low and middle-income countries [3]. In Africa, diarrhea is the leading cause of mortality among young children, accounting for more than half of all deaths among children under the age of five, and globally, it is responsible for one in ten child deaths each year [4, 5]. Childhood diarrhea has a consequence on the child’s development and cognitive abilities [6]. Children who suffer from diarrhea during their first 2 years of life may have an 8 cm growth decrement and a 10 intelligent quotient point decrement when they reach 7–9 years old [5].

Dehydration is the commonest cause of death in children with diarrhea. Diarrhea-induced dehydration can also result in the loss of important nutrients, resulting in micronutrient deficits and severe malnutrition in children [7]. Although fluid replacement during diarrheal episodes can avert a large share of death from diarrheal illness, only a small proportion of children experiencing life-threatening episodes of diarrhea receive treatment [8, 9]. To avert diarrheal disease-related mortality and morbidity, WHO and UNICEF devised a seven-point action plan for comprehensive diarrhea control [10]. During a diarrhea attack, fluid replacement, continued feeding, and increasing suitable fluids in the home are indeed the mainstays of its treatment [11, 12]. About 39% of children under the age of five in developing countries and 34% of children under the age of five in Africa receive fluid replacement during diarrheal episodes [11, 12].

Diarrhea in children is usually connected with poor household features, such as a poor parental education [13, 14], a big family size [13], lower socio-economic status [14], and also maternal employment status [15, 16]. This in return affects the feeding practice of children during diarrheal episodes, for instance, mothers who have one under-five child are more likely to have appropriate feeding practices (eating or drinking more) during diarrhea episodes as compared to those who have two or more children [17]. Other factors associated with appropriate feeding practice is women attending antenatal and postnatal visits [18].

Fluid replacement and continued feeding can help control complications and speed up recovery from diarrheal disease. The ability to recognize the factors that influence feeding behavior during a diarrheal episode is a necessary precondition for developing diarrheal disease effective intervention strategies. Although studies were conducted in some parts of the East African countries, no previous study was conducted to estimate eating or drinking more during diarrheal episodes among under-five children using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in East African countries. The previous studies mainly focus on national or subnational level, however currently there is a need of integrating east Africa in different circumstances including the health of the population [19], hence it could give an insight to develop child health programs in a coordinated manner in the region. Therefore this study aimed to estimate the prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes among under-five children in the 12 East Africa Countries from 2008 to 2018 using recent DHS.

Methods

Study settings and data source

In this study, the analysis was conducted using secondary data from DHS in east African countries. There are 19 countries in East Africa, of those 13 countries have DHS while six countries did not (Djibouti, Mauritius, Somalia, Somaliland, Seychelles, and Reunion). The study used 12 countries’ (Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Comoros, Rwanda, Mozambique, Tanzania, Madagascar, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Uganda and Malawi), that was conducted after 2008. One country Eritrea was excluded from the study due to restriction of the DHS data. The data were obtained from the official database of the DHS program, www.measuredhs.com after authorization was granted via online request by explaining the purpose of our study. DHS is a nationally representative household survey that collects data on broad range of health indicators like mortality, morbidity, fertility, contraceptive utilization, maternal and child health [20, 21]. In this study, we used the child record datasets (KR file), and extract the outcome and independent variables. The surveys employ stratified, multi-stage, random sampling techniques. Detailed survey techniques and sampling methods used to collect data have been documented somewhere [22].

Study variables

Outcome variable

Feeding practice (drinking or eating more than usual) during childhood diarrhea episodes. The respondents were asked, the amount of foods offered or amount of liquids given during diarrheal episodes 2 weeks prior to the survey in the categories of “more than usual”, “same as usual”, “somewhat less”, “much less”, “none”, “never gave food”, or “don’t know” [20]. Then the outcome is derived after merging thevariable of the amount of food and liquid given and coded 1 if drinking or eating more than usual and the rest coded as 0 [20, 23].

Independent variables

The independent variables were categorized into individual-level and community-level variables after a thorough literature review [17, 18, 24, 25]. The individual-level variables are age, level of education, marital status of respondents, number of ANC visits, place of delivery, distance from the health facility, and wealth status, whereas, the community-level variables include community-level poverty, media exposure, and residence which was driven from individual-level variables. The community poverty level was measured using the household wealth index. The proportion of women in households with a low household wealth index was then calculated and classified as low poverty (those with < 50%) and higher poverty (those with > 50%) using the national median value. Community-level media exposure was created from the respondents’ exposure to newspaper/magazine, radio, and television after merging them and recoding them to Yes/No. since the data were not normally distributed, the median was utilized, and the results were classified as low if less than 50% of respondents had exposure to at least one medium, and high if more than 50% of respondents had exposure to at least one medium.

Data management and statistical analysis

In this study, Stata version 16 software was used for data analysis. Prior to data analysis, the data were weighted to ensure representativeness of the DHS sample and to obtain reliable estimates and standard errors. We applied weighting for sampling weight using women’s individual sampling weight while we run all the analysis. We used cross-tabulations and summary statistics for the descriptive results. Four models were fitted in this study: the null model, which had no explanatory variables, model I, which had individual-level factors, model II, which had community-level factors, and model III, which had both individual and community-level components. Since the models were nested, the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Median Odds Ratio (MOR) and Likelihood Ratio test (LLR), deviance (−2LLR) values were used for model comparison and fitness, respectively. Model III was chosen as the best-fitted model since it had the lowest deviation. Variables having a p-value less than 0.2 in bivariable were used for multivariable analysis. Finally, in the multivariable analysis, adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and a p-value of less than 0.05 were utilized to identify associated factors of drinking or eating more than usual. Forest plot was used to show the overall and the prevalence of each country.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 20,559 mothers/caregivers with their respective under-five children with recent diarrhea were included in the study. Out of all the study participants, 45.59% were between the age of 25–34 years, and the mean age with standard deviation was 27.80 + 6.72. The majority of the participants 16,223(78.91%) were from rural area. From all the countries included 17.43% were from Malawi (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and other characteristics of respondents in East Africa (n = 20,559)

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 15–24 | 7452 | 36.25 |

| 25–34 | 9374 | 45.59 | |

| > 35 | 3733 | 18.16 | |

| Residence | Urban | 4336 | 21.09 |

| Rural | 16,223 | 78.91 | |

| Country | Burundi | 2877 | 13.99 |

| Comoros | 514 | 2.50 | |

| Ethiopia | 1227 | 5.97 | |

| Kenya | 2841 | 13.82 | |

| Madagascar | 993 | 4.83 | |

| Malawi | 3584 | 17.43 | |

| Mozambique | 1204 | 5.86 | |

| Rwanda | 929 | 4.52 | |

| Tanzania | 1122 | 5.46 | |

| Uganda | 2832 | 13.77 | |

| Zambia | 1422 | 6.92 | |

| Zimbabwe | 1014 | 4.93 | |

| Sex of household head | Male | 15,609 | 75.92 |

| Female | 4950 | 24.08 | |

| Current marital status of respondents | Married | 13,960 | 67.90 |

| Not married | 6599 | 32.10 | |

| Educational status of respondents | No education | 4598 | 22.37 |

| Primary education | 11,337 | 55.14 | |

| Secondary education | 4135 | 20.11 | |

| Higher education | 489 | 2.38 | |

| Educational status of partner(n = 16,632) | No education | 3318 | 19.95 |

| Primary education | 8519 | 51.22 | |

| Secondary education | 4049 | 24.34 | |

| Higher education | 746 | 4.49 | |

| Occupation of respondents | Not working | 5042 | 24.53 |

| sales and services | 2722 | 13.24 | |

| agricultural | 9474 | 46.08 | |

| Manual | 3262 | 15.87 | |

| Others | 59 | 0.29 | |

| Wealth status | Poor | 9803 | 47.68 |

| Middle | 3940 | 19.16 | |

| Rich | 6816 | 33.15 | |

| Community-level poverty | Low | 10,534 | 51.24 |

| High | 10,025 | 48.76 | |

| Community-level media exposure | Low | 10,125 | 49.25 |

| High | 10,434 | 50.75 | |

| Visit the health facility for the last 12 months (n = 19,063) | No | 4167 | 21.86 |

| Yes | 14,896 | 78.14 | |

| Distance to the health facility (n = 18,542) | Big problem | 8303 | 44.78 |

| Not big problem | 10,239 | 55.22 |

Prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrhea episodes among children aged less than 5 years

Out of 20,559 children, only 1520 (7.39%) were offered food to eat more than the usual amount, and 5010 (24.37%) to drink more liquids. The prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrhea disease in East Africa was found to be 26.27% (95% CI: 25.68–26.88). Ranges from 15.40% in Comoros to 45.55% in Madagascar (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of overall prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual in the 12 East Africa Countries from 2008 to 2018

Obstetrics related characteristics of respondents

The majority of mothers (45.70%) had four or more antenatal care visits during pregnancy. Nearly 60% of the participants give their first birth between the ages of 18–24. Approximately three-fourths (72.23%) of mothers’ place of delivery was at a health facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric-related characteristics of mothers in East Africa (n = 20,559)

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ANC visit | 0 | 3973 | 19.32 |

| 1–3 | 7191 | 34.98 | |

| 4+ | 9395 | 45.70 | |

| Current pregnancy | No | 19,006 | 92.45 |

| Yes | 1553 | 7.55 | |

| Number of living children | 1 | 4684 | 22.78 |

| 2–5 | 12,986 | 63.17 | |

| 6+ | 2889 | 14.05 | |

| Age of mother at first child in years | < 18 | 6892 | 33.52 |

| 18–24 | 12,301 | 59.83 | |

| 25+ | 1366 | 6.64 | |

| Place of delivery (n = 20,539) | Home | 5708 | 27.77 |

| Health facility | 14,851 | 72.23 |

Child characteristics and common childhood illnesses

A majority of the children (52.77%) were male,53.06% were between the ages of 1 and 2 months. The majority of the children (61.50%) were currently breastfed. Regarding the symptoms, 45.97% had a fever and 44.30% had a cough in the 2 weeks preceding the survey, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Child characteristics and common childhood illness in East Africa (n = 20,559)

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of child | Male | 10,848 | 52.77 |

| Female | 9711 | 47.23 | |

| Current age in years | < 1 | 5432 | 26.42 |

| 1–2 | 10,908 | 53.06 | |

| 3+ | 4219 | 20.52 | |

| Child is twin | Single | 20,022 | 97.39 |

| Multiple | 537 | 2.61 | |

| Currently breast feed | No | 7915 | 38.50 |

| Yes | 12,644 | 61.50 | |

| Had fever in the last two weeks (n = 20,541) | No | 11,099 | 54.03 |

| Yes | 9442 | 45.97 | |

| Had cough in the last two weeks (n = 20,532 | No | 11,436 | 55.70 |

| Yes | 9097 | 44.30 |

Factors associated with drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes

In this analysis, the multivariable multilevel model was fitted and found ICC of 6.8% (95%.

CI: 5.5, 8.3) and deviance of 21,456.484. From the final model age of respondents, occupation,, educational status, marital status, number of antenatal care visits, place of delivery, visiting health facility in the past 12 months, wealth status and child age were variables significantly associated with drinking or eating more than usual during diarrhea for children aged less than 5 years. Accordingly, children whose mother is in the age group of > 35 years increases the odds of eating or drinking more than the usual during diarrheal episodes by 1.14 times (AOR = 1.14, CI: 1.03, 1.26) compared to mothers with the age group of 15–24 years. Children whose mothers had primary education, secondary education, higher education 1.17 (AOR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.28), 1.43 (AOR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.27, 1.61), 1.42(AOR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.81) times more likely to drink or eat more than usual compared to mothers with no education, respectively. Children whose mother is married were 1.27 times more likely to drink or eat more than usual when compared with unmarried ones (95% CI: 1.18, 1.37). Children whose mother works in sales and services, agriculture occupations, and manual work, 1.20 (AOR = 1.20, CI: 1.07, 1.34), 1.36 (AOR = 1.36, CI: 1.24, 1.47), and 1.28 (AOR =1.28, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.44) times more likely to drink or eat more than usual compared to mothers with no work, respectively. Children from the middle family 1.13 (AOR =1.13, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.23) and the rich family 1.27(AOR =1.27, 95%CI: 1.16, 1.40) times more likely to drink or eat more than usual compared with poor families. Children being in the age group of 1–2 years (AOR =1.34, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.46) and 3 and above years (AOR =1.36, 95% CI: 1.20, 1.55) are more likely to drink or eat more than usual compared with infants. Children whose mothers attended four or more antenatal visit (AOR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.27) were more likely to drink or eat more than usual compared with no visits. Mothers who gave birth at a health facility (AOR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.10, 1.30) were more likely to give more drink or food to their children. Mothers who visit health facilities in the last 12 months (AOR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.22) were more likely to give more fluid or food to their children.

In the empty model, the values of Intra Class Correlation (ICC = 7.66%) and Median Odds Ratio (MOR = 1.64) implies the presence of community-level variability of drinking or eating more. Around 8% of the variation in modern contraceptive use is attributed to ICC. In the empty model, the presence of heterogeneity of drinking or eating more between clusters is indicated by the MOR with a value of 1.64. It indicates that if we randomly select under-five age children, a child at the cluster with higher drinking or eating had around 1.64 times higher odds of drinking or eating more than a child at cluster with lower drinking or eating. Model III had the lowest deviance value (21,456.484) and hence it was selected as the best-fitted model (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes in East Africa (n = 20,559)

| Variables | Null model | Model I AOR (95% CI) | Model II AOR (95% CI) | Model III AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of respondents | ||||

| 15–24 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–34 | 0.99(0.92,1.07) | 0.99(0.92,1.07) | ||

| > 35 | 1.14(1.03, 1.26) | 1.14(1.03, 1.26)* | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 1 | |||

| Urban | 1.21(1.11,1.32) | 0.97 (0.87,1.08) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married | 1.27(1.18,1.37) | 1.27(1.18,1.37)*** | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| No education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary education | 1.16(1.06,1.27) | 1.17(1.06,1.28)** | ||

| Secondary education | 1.42(1.27,1.60) | 1.43(1.27,1.61)** | ||

| Higher education | 1.40(1.10,1.79) | 1.42(1.11,1.81)** | ||

| Occupation of respondents | ||||

| Not working | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sales and services | 1.19(1.06, 1.34) | 1.20(1.07,1.34)** | ||

| Agricultural | 1.36(1.25,1.49) | 1.36(1.24,1.47)*** | ||

| Manual | 1.27(1.11,1.44) | 1.28(1.11,1.44)*** | ||

| Others | 1.20(0.65,2.18) | 1.18(0.65,2.16) | ||

| Wealth status | ||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | ||

| Middle | 1.14(1.04, 1.25) | 1.13(1.03 1.23)* | ||

| Rich | 1,29(1.18, 1.40) | 1.27(1.16, 1.40)*** | ||

| Community-level poverty | ||||

| High | 1 | |||

| Low | 1.18(1.07,1.32) | 1.10(0.99, 1.22) | ||

| Number of ANC visit | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1–3 | 1.06(0.95,1.18) | 1.06(0.95,1.18) | ||

| 4+ | 1.14(1.03,1.27) | 1.14(1.03,1.27)* | ||

| Place of delivery | ||||

| Home | 1 | 1 | ||

| Health facility | 1.19(1.10,1.30) | 1.19(1.10,1.30)*** | ||

| Child age | ||||

| < 1 year | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1–2 years | 1.34(1.22,1.46) | 1.34(1.22,1.46)** | ||

| 3–4 years | 1.36(1.20,1.55) | 1.36(1.20,1.55)** | ||

| Currently breastfeeding | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.98(0.84,1.00) | 0.92(0.83,1.00) | ||

| Community-level media exposure | ||||

| Low | 1 | |||

| High | 0.95(0.86,1.05) | 0.92 (0.83,1.02) | ||

| Visit the health facility for the last 12 months | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.12(1.03,1.22) | 1.12(1.03,1.22)** | ||

| Intercept | 0.27(0.22,0.34) | 0.11(0.09,0.14) | 0.29(0.2,0.32) | 0.11(0.09,0.14) |

| Measure of variations | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −11,688.45 | −10,730.50 | −11,670.46 | −10,728.24 |

| Deviance | 23,376.89 | 21,461.01 | 23,340.91 | 21,456.48 |

| Variance | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| ICC | 7.67(6.32, 9.26) | 6.83(5.54,8.34) | 7.54(6.21,9.12) | 6.80(5.53,8.33) |

| PCV | Reference | 11.1% | 3.7% | 14.8% |

| MOR | 1.64 | 1.59 | 1.62 | 1.57 |

Null model-contains no explanatory variables; Model I-includes individual-level factors only; Model II-includes community-level factors only; Model III includes both individual-level and community-level factors, AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence internal, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, MOR median odds ratio, PVC proportional change in variance.

*** P-value < 0.001, ** p-value < 0.01, * p-value < 0.05

Discussion

Mothers or caregivers are recommended to enhance feeding practices, notably giving children more fluid and food than normal, to avoid mortality, dehydration, and the consequences of diarrhea on nutritional status [10, 26, 27]. Oral rehydration therapy is the most commonly prescribed treatment for diarrhea. Rice water, yogurt, soup, salt sugar solution, and clean water are some home-based fluids that are recommended [28]. The findings of our study will help policy and program makers to develop tailored intervention strategies by considering the level of feeding practice and the factors associated with it.

In this study, the overall prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes was 26.27%(95% CI: 25.68–26.88), and maternal age, mother’s occupation, antenatal care visit, marital status, educational status, wealth status, place of delivery, child age, and visiting health facility in the past 12 months were significantly associated with drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes.

This study showed that the prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes was similar to a study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan (26.2%) [29]. It is higher than a study done in Ethiopia DHS (15.4%) [18]. This variation may be due to the difference in sociocultural and socioeconomic status. However, the prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual in this study is lower than a study conducted in Ethiopia, West Hararge Zone (40.8%), in Burayu Town (53.6%) [30], and Gamo Gofa zone (70.7%) [17]. This may be due to the fact that nationally representative data in our study and the difference in the study populations (those studies recruited less than 2 years).

The odds of drinking or eating more than usual among children whose mothers aged > 35 years were higher compared to mothers whose age is between 15 and 24 years. This was supported in a study done in Ethiopia [17, 31], and a study done in Nellore District, South India [24] where mothers’ age is associated with good knowledge to feed their children. The possible reason could be as a woman gets older the probability of getting information about feeding practice and learning from their experience is getting higher and higher. The other possible reason might be older women exposed to health-related information during their consecutive pregnancy visits.

This study showed that the odds of drinking or eating more than usual among children whose mother married was higher compared with unmarried mothers. The possible reason might be those married mothers may have better coordination with their spouse, the increase in activity to the household and they may get better knowledge from their parents. Parents’ support are essential for the health of their children [32].

Children whose mothers education primary, secondary, and higher education have higher odds of drinking or eating more than usual compared with those who have no education. This was supported by a study done in Ugandan children where maternal literacy is associated with better infant and young children feeding practice [33]. This is in fact, health knowledge and behavior are improved by education, the higher the education the ability to read and comprehend the nutrition requirement guideline increases [34, 35]. In addition, access and ability to search health related information increases. This implies that educating mothers could be one strategy to improve children feeding practice during diarrheal episodes.

The odds of drinking or eating more than usual among children whose mothers worked in sales and services, agriculture and manual were higher compared with children whose mothers did not have work. Participating in work may expose mothers to information regarding feeding practices from peers and friends [29, 36, 37].

This study revealed that the odds of drinking or eating more than usual among children with middle and rich families were higher compared with the poor ones. The possible reason could be children from the poor household have poor access to adequate food, which makes them less likely to eat or drink more than the usual amount [38–41]. It means that being wealthiest determine the ease of accessing resources to meet one’s own need and in return children’s feeding practice during diarrheal episodes. This implies that there is a need to improve household wealth status.

The results of this study show that the odds of drinking or eating more than usual among children aged above 1 year is higher compared with infants. This was supported by different studies which reported that children aged between 6 and 11 months were not given appropriate complementary feeding [42, 43]. This could be due to the reason the practice of complementary feeding as infants are less likely to eat food as compared with older children. This implies that there is a need for health programme intervention to pay more attention to give more fluids or foods during the diarrheal episode for infants, hence they are at risk of fluid loss compared with older children [44].

The current study showed that mothers who had ANC visits, who gave birth at health facility, and who visit health facilities in the last 12 months, were more likely to drink or eat more than usual. This is consistent with studies which show mothers who had more than four ANC visits feed their children appropriately [17, 29]. This might be due to improved access to health-care facilities increases the amount of health-related information received from health workers, including information on how to feed during diarrheal episodes. These facilities are a good place to go for advice on child feeding practices, as well as maternal and child care. Health professionals may provide information, education, and counseling to mothers who had ANC and who gave birth at health facilities, and who visit health facilities about proper child feeding practices for normal child growth and during an illness such as diarrhea disease.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Regarding the strengths, the study uses large data set from 12 east African countries, which is representative across the countries. This study also used a multilevel modeling technique to come up with a more reliable result that takes into account the survey data’s hierarchical nature. However, the study is not free of limitations, the survey is prone to social desirability due to the self-reported nature of the interview, and the cross-sectional nature of the study may not explain the temporal relationship of the independent and the outcome variables.

Conclusions

This study shows that drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes is low in East African countries. Maternal age, mothers occupation, antenatal care visit, marital status, educational status, wealth status, place of delivery, visiting health facility in the past 12 months, and child age were significantly associated with drinking or eating more than usual during diarrheal episodes. Health policy and programs should focus on educating mothers/caregivers, improving the wealth status, encouraging women to contact health facilities for better feeding practice of children during diarrheal episodes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the DHS programs, for granting access to all the relevant DHS data for this study.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- ICC

Intra-class Correlation Coefficient

- MOR

Median Odds Ratio

- PCV

Proportional Change in Variance

- SD

Standard Deviation

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. HBE, SMF, DGB, and EAF conceived the idea. HBE extract the data, conducted the analysis, and write the original draft of the manuscript, ESS, DBA, RET, FMA, TGA, WDN critically reviewed the manuscript. DGB, WDN, and SMF assisted in the data analysis and interpretation. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors’ have not received any funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The availability of the data set for this study was obtained from the DHS program data sets using the website www.measuredhs.com after we have sent research objectives.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical approval and permission to access the data were obtained from the DHS website www.measuredhs.com. All DHS surveys were approved by ICF International and an Institutional Review Board (IRB) in each country, in accordance with United states Department of Health and Human Services requirements for human subject protection and theethical standards are available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X. All methods were carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

It is not applicable for this study since the study used secondary data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Habitu Birhan Eshetu, Email: habser12@gmail.com.

Samrawit Mihret Fetene, Email: samrimih21@gmail.com.

Ever Siyoum Shewarega, Email: eversiyoum@yahoo.com.

Elsa Awoke Fentie, Email: elsaawoke91@gmail.com.

Desale Bihonegn Asmamaw, Email: desalebihonegn1988@gmail.com.

Rediet Eristu Teklu, Email: redieteristu7@gmail.com.

Fantu Mamo Aragaw, Email: fantuma3@gmail.com.

Daniel Gashaneh Belay, Email: danielgashaneh28@gmail.com.

Tewodros Getaneh Alemu, Email: tewodrosgetaneh7@gmail.com.

Wubshet Debebe Negash, Email: wubshetdn@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Diarrhoeal disease. Tropical doctor. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jelliffe DB, Jelliffe PEF. Dietary management of young children with acute diarrhoea. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNICEF. One is too many: ending child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea. New York, NY; 2016.

- 4.Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bhatia SK. Diarrheal Diseases. InBiomaterials for Clinical Applications. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. p. 121–45.

- 6.Pinkerton, Relana et al. Early childhood diarrhea predicts cognitive delays in later childhood independently of malnutrition. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(5):1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Sibbald BJ. One is too many. Can Nurse. 1996;92(9):22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Walker N, Rizvi A, Campbell H, Rudan I, et al. Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;381:1417–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhutta ZA, Zipursky A, Wazny K, Levine MM, Black RE, Bassani DG, et al. Setting priorities for development of emerging interventions against childhood diarrhoea. J Glob Health. 2013;3(1) [cited 2021 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc3700035/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.World Health Organization U . A 7-point plan for plan for comprehensive diarrhoea control - prevention and treatment measures - diarrhoea - diarrhea - diarrea: why children are still dying and what can be don. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta GR. Tackling pneumonia and diarrhoea: the deadliest diseases for the world’s poorest children. Lancet. 2012;379:2123–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardlaw T, Salama P, Brocklehurst C, Chopra M, Mason E. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. Lancet. 2010;375:870–872. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asfaha KF, Tesfamichael FA, Fisseha GK, et al. Determinants of childhood diarrhea in Medebay Zana District, Northwest Tigray, Ethiopia: a community based unmatched case–control study. BMC pediatrics. 2018;18(1):1–9. Available from: 10.1186/s12887-018-1098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Escobar AL, Coimbra CE, Welch JR, Horta BL, Santos RV, Cardoso AM. Diarrhea and health inequity among Indigenous children in Brazil: results from the First National Survey of Indigenous People’s Health and Nutrition. BMC public health. 2015;15(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Atnafu A, Sisay MM, Demissie GD, Tessema ZT. Geographical disparities and determinants of childhood diarrheal illness in Ethiopia: further analysis of 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. Trop Med Health. 2020;48(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Tambe A, Nzefa L, Nicoline N. Childhood diarrhea determinants in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross sectional study of Tiko-Cameroon. Challenges. 2015;6(2):229–243. doi: 10.3390/challe6020229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fikadu T, Girma S. Feeding practice during diarrheal episode among children aged between 6 to 23 months in Mirab Abaya District, Gamo Gofa zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/2374895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsehay CT, Aschalew AY, Dellie E, Gebremedhin T. Feeding practices and associated factors during diarrheal disease among children aged less than five years: evidence from the Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016. Pediatr Heal Med Ther. 2021;12:69–78. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S289442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamin AE, Maleche A. Realizing Universal Health Coverage in East Africa: the relevance of human rights. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK. The DHS program - guide to DHS statistics (English). Demograhic and Health Surveys. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesema GA, Tessema ZT, Tamirat KS, Teshale AB. Prevalence of stillbirth and its associated factors in East Africa: generalized linear mixed modeling. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Tesema GA, Yeshaw Y, Worku MG, Tessema ZT, Teshale AB. Pooled prevalence and associated factors of chronic undernutrition among under-five children in East Africa: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3 March):e0248637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngwira A, Chamera F, Soko MM. Estimating the national and regional prevalence of drinking or eating more than usual during childhood diarrhea in Malawi using the bivariate sample selection copula regression. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kishore E, Umamahesh R, … VM-. Feeding Practice during Diarrheal Episode among Children Aged between 6 to 23 Months in Nellore District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. ijhcr.com. [cited 2021 Nov 29]; Available from: https://www.ijhcr.com/index.php/ijhcr/article/view/1177

- 25.Pantenburg B, Ochoa T, … LE-TA journal of, 2014 undefined. Feeding of young children during diarrhea: caregivers’ intended practices and perceptions. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [cited 2021 Nov 27]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4155559/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Pantenburg B, Ochoa TJ, Ecker L, Ruiz J. Feeding of young children during diarrhea: caregivers’ intended practices and perceptions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(3):555–562. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNICEF . One is too many: ending child deaths from pneumonia and Diarrhoea. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhoea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. Geneva; 2005.

- 29.Masiha SA, Khalid A, Malik B, Muhammad S, Shah A. Oral rehydration therapy- knowledge , attitude and practice ( KAP) survey of Pakistani mothers. J Rawalpindi Med Coll Students Suppl. 2015;19(s-1):51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degefa N, Tadesse H, Aga F, Yeheyis T. Sick child feeding practice and associated factors among mothers of children less than 24 months old, in Burayu town, Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr (United Kingdom). 2019;2019 [cited 2021 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijpedi/2019/3293516/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dodicho T. Knowledge and practice of mothers/caregivers on home management of diarrhea in under five children in Mareka District, Southern Ethiopia. J Heal Med Nurs. 2016;27:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Psychological Association. Parents and caregivers are essential to children’s healthy development: American Psychological Association; 2016. [cited 2022 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/parents-caregivers

- 33.Ickes SB, Hurst TE, Flax VL. Maternal literacy, facility birth, and education are positively associated with better infant and young child feeding practices and nutritional status among Ugandan children. J Nutr. 2015;145(11):2578–2586. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore SG, Donnelly JK, Jones S. Effect of educational interventions on understanding and use of nutrition labels : a systematic review. 2018. pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mocan N, Altindag DT. Education, cognition, health knowledge, and health behavior. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(3):265–279. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tassew AA, Tekle DY, Belachew AB, Adhena BM. Factors affecting feeding 6–23 months age children according to minimum acceptable diet in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis of the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0203098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Kushwaha KP, Sankar J, Sankar MJ, Gupta A, Dadhich JP, Gupta YP, et al. Effect of peer counselling by mother support groups on infant and young child feeding practices: the Lalitpur experience. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e109181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong R, Banta JE, Betancourt JA. Relationship between household wealth inequality and chronic childhood under-nutrition in Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health. 2006;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zere E, McIntyre D. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puspitasari MD, Gayatri M. Indonesia infant and young child feeding practice: the role of women’s empowerment in household domain. Global J Health Sci. 2020;12(9):129. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v12n9p129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chilton M, Chyatte M, Breaux J. The negative effects of poverty & food insecurity on child development. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:262–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kassa T, Meshesha B, Haji Y, Ebrahim J. Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6-23 months in southern Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0675-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mekbib E. Magnitude and factors associated with appropriate complementary feeding among mothers having children 6-23 months-of-age in northern Ethiopia; a community-based cross-sectional study. J Food Nutr Sci. 2014;2(2):36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vega RM, Avva U. Pediatric dehydration. StatPearls. 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The availability of the data set for this study was obtained from the DHS program data sets using the website www.measuredhs.com after we have sent research objectives.