Abstract

Our objectives were to 1) investigate the difference in chemical composition and disappearance kinetics between loose dried distillers’ grains (DDG) and extruded DDG cubes and 2) evaluate the effects of supplementation rate of extruded DDG cubes on voluntary dry matter intake (DMI), rate and extent of digestibility, and blood parameters of growing beef heifers offered ad libitum bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) hay. To characterize the changes in chemical composition during the extrusion process, loose and extruded DDG were evaluated via near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy, and dry matter (DM) disappearance kinetics were evaluated via time point in situ incubations. Extruded DDG cubes had greater (P ≤ 0.01) contents of fat, neutral detergent insoluble crude protein, and total digestible nutrients, but lower (P ≤ 0.01) neutral and acid detergent fiber than loose DDG. Additionally, the DM of extruded DDG cubes was more immediately soluble (P < 0.01), had greater (P < 0.01) effective degradability and lag time, and tended (P = 0.07) to have a greater disappearance rate than loose DDG. In the 29-d supplementation rate study, 23 Charolais-cross heifers were randomly assigned to one of four supplemental treatments: 1) control, no supplement; 2) low, 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d; 3) intermediate, 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d; or 4) high, 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d. Titanium dioxide was used as an external marker to estimate fecal output and particulate passage rate (Kp). Blood was collected from each animal to determine supplementation effects on blood metabolites. Indigestible neutral detergent fiber was used as an internal marker to assess the rate and extent of hay and diet DM digestibility (DMD). Increasing supplementation rate increased Kp and total diet DMI linearly (P < 0.01), yet linearly decreased (P < 0.01) hay DMI. Hay DMD decreased quadratically (P < 0.01), while total diet DMD increased linearly (P < 0.01) with increased DDG cube inclusion. Supplemented heifers had greater (P = 0.07) blood urea nitrogen concentrations than control animals 4 h post-supplementation. Intermediate and high rates of supplementation resulted in lower (P < 0.01) serum nonesterified fatty acid concentrations post-supplementation than control heifers. Concentrations of serum glucose and lactate were greatest (P ≤ 0.06) 8 h post-supplementation. Our results suggest that extruded DDG cubes may be an adequate supplement for cattle consuming moderate-quality forage, and further research is warranted.

Keywords: digestibility, disappearance, extruded dried distillers’ grains cube, intake, supplementation rate

Lay Summary

Growing cattle are oftentimes provided supplemental concentrate as a source of protein and energy in order to meet performance goals when consuming low-quality forages. The effects of supplemental concentrate on forage intake vary, which may be related to the quality of forage and the characteristics of the supplement being evaluated. Dried distillers’ grains (DDG) are a by-product of ethanol production and have become a common supplement for growing cattle due to the increased energy and rumen undegradable protein content. A stable DDG cube made via a novel extrusion process may be advantageous for pasture supplementation due to the reduced risk of loss of product from wind and soil mixing that is common with loose DDG. The effects of supplementation rate of traditional concentrate sources on forage intake are abundant, but research regarding extruded DDG cubes is almost nonexistent. Thus, our objective was to evaluate extruded DDG cube supplementation rate (0, 0.90, 1.81, or 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d) for growing cattle on voluntary intake and digestibility of moderate-quality forage. Although increasing supplementation rate reduced forage intake and digestibility, total diet intake and digestibility were increased. Our results suggested that extruded DDG cubes have potential as a supplement for cattle consuming moderate-quality forage.

A novel extrusion process has allowed for the production of a stable dried distillers’ grains cube that is a potential supplement for growing cattle consuming moderate-quality forages.

Introduction

Supplemental concentrate as a source of protein and energy is typically required for grazing growing cattle to meet performance goals. This management strategy is more common for low-quality forages as protein and energy consumed from the forage alone are often inadequate to meet production goals (Moore et al., 1999). Consequently, relatively few studies have evaluated supplementation regimens’ effects on cattle consuming medium- to high-quality forage. However, supplementation of protein and energy to growing cattle can also be employed as a management strategy when forage availability is limited, to improve the utilization of forage, or to increase production and profitability (Kunkle et al., 2000), all of which are associated with medium- to high-quality forages. The effects of supplemental concentrate on forage intake vary, which may be related to the quality of forage and the characteristics of the supplement being evaluated. Morris et al. (2005) determined that consumption of both low- and high-quality forage was decreased in heifers in response to increased supplementation rate of loose dried distillers’ grains (DDG); however, the response was greater for higher quality forages. In contrast, Winterholler et al. (2012) reported supplementation of loose DDG increased the intake of low-quality tallgrass prairie hay by 18% to 31% compared with unsupplemented cows.

Traditional sources of supplemental concentrate tend to be high in starch content, which negatively affects forage digestibility, but by-products of grain milling and distilling industries are often moderate in protein with lower starch content (Morris et al., 2005). DDG are a by-product of ethanol production and have become a commonly utilized supplement for growing cattle due to the high energy and rumen undegradable protein (RUP) content. In addition, starch is removed from the DDG during the ethanol production process, resulting in a significant increase in the concentration of other nutrients (Stock et al., 1999; Spiehs et al., 2002). Placing DDG under high pressure, at high temperatures, has enabled the production of a stable DDG cube that provides advantages for supplementing cattle on pasture, such as reduced loss of product to wind and soil mixing, which is common when feeding loose DDG on pasture.

Although research evaluating supplementation rates of traditional protein and energy sources is abundant, research investigating the effects of supplementation rates of extruded DDG cubes is not documented. Therefore, the objectives of these studies were to 1) investigate the differences in chemical composition and disappearance kinetics between loose DDG and the extruded DDG cube obtained from a production plant (MasterHand Milling, Lexington, NE) and 2) evaluate the effects of supplementation rate of DDG cubes on voluntary intake (DMI), rate and extent of digestibility, and blood parameters of growing beef heifers offered ad libitum bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) hay.

Materials and Methods

All animals and procedures used in this experiment were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee (protocol AG-14-13) of Oklahoma State University.

Chemical composition of loose and extruded DDG

Twice daily from 12 to 14 August 2019, one sample of each DDG before entering the extrusion process and DDG following the extrusion process at the MasterHand Milling production facility (Lexington, NE) were collected (n = 12 samples). Data logs from processing machines were obtained for comparison of the extrusion process between the collection days. Data logs contained the setpoints and actual measurements at the time of collection for temperatures throughout processing, as well as rotations per minute (RPM), pressure, and thrust of the machine. On collection dates, all five extruder temperatures were set at 82 °C with a set point of 33 RPM. The actual measurements of extruder temperatures differed slightly between collection dates, with temperatures ranging from 81 to 92 °C. Water temperature in the extruder ranged from 32 to 35 °C, with an average temperature of 33 °C. The melt temperature, or the last temperature measurement before entering the dying process, ranged from 87 to 94 °C and averaged 91 °C. The setpoint and actual measurements for RPM of the extruder ranged from 31.1 to 33 RPM, but the average for the exact measurement over the collection period was 32.6 RPM. Extruder pressure varied over the collection period, with an average of 3,019 psi, whereas the screw thrust averaged 50% with minimal variation.

Loose DDG samples were ground to pass through a 2-mm screen using a cutting mill (Pulverisette 19, Fritsch Milling and Sizing Inc., Pittsboro, NC), while extruded DDG cube samples were crushed with a mortar and pestle prior to being ground in the same manner. Following the grinding process, the chemical composition of all samples was estimated via near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS; NIRS DS2500 F, Foss Analytics, Eden Prairie, MN) following the procedures of Chen et al. (2013). The total mixed ration and high moisture corn calibration were used for NIRS analyses, and all global and neighborhood H values were below 2.0 and 0.5, respectively. Additionally, DDG samples were analyzed for nitrogen (method 990.03; AOAC, 2000) to calculate crude protein (CP) as N × 6.25, fat content (method Am 5-04; AOCS, 2005), and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) according to Van Soest et al. (1991). Total digestible nutrients (TDN) were calculated based on equations from Tedeschi and Fox (2020). Wet lab values for ash, crude protein, fat, NDF, and ADF and NIRS estimates for NDF digestibility (NDFD), ND insoluble CP (NDICP), AD insoluble CP (ADICP) were used in the calculation of TDN. Wet lab values for ash, crude protein, fat, NDF and ADF, and NIRS estimates for NDFID, NDICP, ADICP, and calculated TDN were compared for paired loose and extruded DDG collected at the same time points.

Based on the values from NIRS analysis, the average TDN was calculated for both the loose and extruded DDG and used as selection criteria for further evaluation. Paired samples of DDG from pre- and post-extrusion samples, one collected on 12 August 2019 at 1500 hours and the other on 13 August 2019 at 0800 hours, were closest to the average TDN and therefore selected for the evaluation of in situ disappearance kinetics.

Supplementation rate and intake

Charolais-cross heifers (n = 23; BW = 286 ± 38.9 kg) were used to evaluate the effects of DDG cube supplementation rate on voluntary intake of ad libitum bermudagrass (C. dactylon) hay during a 29-d study. Animals were randomly assigned to one of four supplementation treatments: 1) Control (CON), no supplement offered (n = 6); 2) Low (DGL), DDG cubes offered at 0.90 kg/d (n = 6); 3) Intermediate (DGI), DDG cubes offered at 1.81 kg/d (n = 5); or 4) High (DGH), DDG cubes offered at 3.62 kg/d (n = 6). Supplementation rates were selected to achieve approximately 0%, 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1.0% of BW intake (dry matter [DM] basis) for CON, DGL, DGI, and DGH, respectively. All heifers were maintained in a dry lot with ad libitum access to round bales of bermudagrass hay fed in a ring-type feeder. The chemical composition of the hay and supplemental DDG cubes are presented in Table 1. Heifers were separated into individual feeding stalls each morning and offered supplemental DDG cubes for 1 h. After 1 h, animals were returned to the dry lot, and orts were collected and weighed to determine actual supplement intake as a percent of BW for use in the analysis. This was especially necessary for DGH heifers due to variable intake between animals and a pattern of fluctuating intake of supplemental DDG cubes from day to day, which may have been caused by jaw fatigue from extensive chewing (Forbes, 1986) in the short period of exposure.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of bermudagrass hay and supplemental extruded dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cubes fed

| Item1 | Bermudagrass hay | DDG cube |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition2 | ||

| DM, % | 89.3 | 90.6 |

| CP, % DM | 10.5 | 34.9 |

| aNDF, % DM | 68.8 | 33.5 |

| ADF, % DM | 36.3 | 10.6 |

| Fat, % DM | 3.0 | 8.9 |

| NFC, % DM | 9.8 | 12.6 |

| TDN, % DM | 59.9 | 86.1 |

Items are chemical composition of hay and supplement fed evaluated via near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy.

aNDF, neutral detergent fiber with the addition of alpha-amylase and sodium sulfite; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NFC, non-fiber carbohydrates; TDN, total digestible nutrients calculated according to Tedeschi and Fox (2020).

Following a 14-d adaptation to supplement and feeding stalls, heifers were orally dosed twice daily with 5 g of titanium dioxide (TiO2), at 0800 and 1700 hours, in porcine gelatin capsules (10 g/d; Torpac #10: Torpac Inc., Fairfield, NJ) from days 15 to 25 (Brisson et al., 1956). After the concentration of TiO2 was assumed to have reached a plateau (Owens and Hanson, 1992), fecal samples were collected from the rectum from days 22 to 25 at the time of each dosing to estimate fecal output (FO). Fecal sampling continued from days 25 to 29 at 3, 15, 19, 23, 27, 39, 51, 63, 72, 87, and 96 h after the last dose of TiO2 to determine passage rate (Kp). Following collection, all fecal samples were dried in a forced-air oven at 55 °C for 72 h, or until weight loss ceased. After drying, daily fecal samples were composited by animals and ground to pass through a 2-mm screen using a cutting mill and stored for future analysis. In addition, subsamples of hay and supplemental DDG cubes offered were collected throughout the trial and dried and ground in the same manner before being stored for future analysis. On day 26, blood was collected from each animal via jugular venipuncture (9 mL neutral Sarstedt Monovette, Sarstedt AG & Co. KG, Nümbrecht, Germany) immediately before supplementation and 4 and 8 h post-supplementation for analysis of blood urea N (BUN), nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA), glucose, and lactate.

Digestibility parameters were evaluated using indigestible NDF (iNDF) as an internal digestibility marker based on Adams et al. (2020), while disappearance kinetics and rate and extent of the disappearance of DM and NDF were determined via time point in situ incubations.

Digestibility and in situ disappearance kinetics

Four Holstein steers (BW = 281 ± 29.5 kg) fitted with rumen cannulas were used as in situ incubation animals. All incubation animals were maintained in a dry lot with ad libitum access to round bales of bermudagrass (C. dactylon) hay similar to that used in the supplementation rate experiment. Two steers received 0.90 kg/d of supplemental DDG cubes throughout the incubation period to evaluate the effects of supplementation on the rate and extent of digestion of the incubated forage samples. Supplemented animals were adapted to the DDG cubes for 14 d before the onset of the trial. Steers receiving DDG cubes were separated into individual stalls at 0700 hours every morning and provided DDG cubes daily throughout the incubation period.

The measurement of iNDF was performed using F57 fiber bags (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY) filled with a sample size-to-surface area ratio of 20 mg/cm2 and a 576 h ruminal incubation (Norris et al., 2019; Adams et al., 2020). Hay and supplemental DDG cubes, as well as the fecal samples composited by animal (n = 23) were prepared in duplicate for each cannulated animal, and all bags were incubated for 576 h within a commercial laundry bag placed in the rumen.

Disappearance kinetics were evaluated using the same bag type and sample size-to-surface area ratio. In addition to hay and supplemental DDG cubes fed throughout the trial, the paired samples of loose DDG and extruded DDG cubes selected from the production plant were included to determine differences in the extent of digestion. For each incubation animal (n = 4) and incubation length (n = 9), three replicates of hay samples and four replicates of supplemental DDG cubes fed in the supplementation trial, as well as four replicates of both production plant loose and extruded DDG were ruminally incubated for 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h within a second commercial laundry bag. All bags were inserted in reverse order for ease of removal, with internal marker samples being inserted at h-0 and the addition of disappearance kinetics samples beginning at h-456. Upon completion of incubation, all bags were simultaneously removed from the rumen and immediately soaked in ice water to terminate fermentation (Dewhurst et al., 1995). After fermentation ceased, all bags were rinsed on the delicate cycle of a household washing machine with cold water (Krizsan and Huhtanen, 2013) until the water was clear. Although the 0 h bags were not ruminally incubated, they underwent the same soaking and rinsing processes as the incubated bags to estimate the immediately soluble fraction of each feedstuff (Warner et al., 2020a). All bags were dried in a forced-air oven at 55 °C for 48 h and subsequently dried at 105 °C for 24 h.

Laboratory analysis

Concentrations of TiO2 in each hay, supplement, and all fecal samples were measured in duplicate using a handheld X-ray fluorescence analyzer (Delta Premium with Rh anode, Olympus Scientific Solutions, Waltham, MA) following procedures of Thompson et al. (2019). Marker concentrations in fecal composite samples were used to estimate FO, while Kp was determined from the disappearance of TiO2 in fecal samples collected over 96 h.

Blood samples were agitated and stored on ice for transportation back to the laboratory, where serum was separated via centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 20 min and held at −20 °C for future analysis (Zebeli et al., 2010). Serum glucose and lactate concentrations were determined using an immobilized enzyme analyzer (YSI Model 2900D; YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH). Serum urea nitrogen concentrations were measured via automated colorimetric procedures (Marsh et al., 1965), and serum concentrations of NEFA were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric method (NEFA-C Kit; WAKO Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). The intra- and inter-assay CV were, respectively, 3.8% and 14.7% for BUN, and 3.6% and 10.8% for NEFA.

Following drying procedures, all in situ bags were transferred into a desiccator to equilibrate and weighed to determine DM remaining (DMR). Following Van Soest et al. (1991) procedure, all bags were subsequently washed in neutral detergent (ND) solution with a ratio of 100 mL/g DM and 4 mL of heat-stable amylase using the ANKOM2000 automated fiber analyzer (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY) with the omission of sodium sulfite (Van Soest, 1994). Afterward, bags were soaked in acetone and air-dried before being dried at 105 °C for 24 h. Upon removing from the dryer, bags were placed in a desiccator to equilibrate and weighed to obtain NDF remaining (NDFR) for the estimation of disappearance kinetics and iNDF for digestibility estimations. Fecal composite samples collected from each heifer during the supplementation rate study were washed in duplicate using the ND washing procedure mentioned above to determine NDF content for the calculation of NDFD.

Calculations

Determination of DMR post-incubation was calculated using the following equations of Adams et al. (2020), and as iNDF and NDFR were calculated in the same manner, both will be referred to as NDFR within the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where W1 is the initial weight of the empty bag (g), W2 is the initial sample weight (g), W3 is the weight of the dried bag and sample remaining after the initial post-incubation water rinse (g), W4 is the weight of the dried bag and sample remaining following the ND wash (g), C1 is the blank correction factor following the initial post-incubation water rinse (average weight of the dry bag following the cold water rinse divided by the initial weight of the empty bag, for each incubation length), and C2 is the blank correction factor following the ND wash (average weight of the dry bag following the ND wash divided by the initial weight of the empty bag, for each incubation length).

Fecal output was calculated according to Van Soest (1994) technique using the equation:

| (3) |

Furthermore, equations reported by Kartchner (1980) were used to estimate hay and total diet DMI and DM digestibility (DMD) for heifers during the intake experiment, with TiO2 as the external marker and iNDF as the internal digestibility marker (Supplementary Table S1).

The degradation fractions of DM and NDF were defined according to Ørskov and McDonald (1979), with the A fraction being the immediately soluble fraction of the feedstuff that rapidly disappears upon ruminal incubation, the B fraction defined as the amount of the specific nutrient that disappears at a fractional rate over time, and the C fraction being the undegradable portion that did not disappear throughout incubation.

Disappearance curves for incubation animal and sample type were analyzed using PROC NLIN, with the fraction parameters being B: 20 to 50 by 2, C: 10 to 40 by 2, K: 0 to 0.2 by 0.01, and L: 0 to 10 by 1 and bounds for the model being specified as B: 0 to 100, C: 0 to 100, K: 0 to 0.3, and L: 0 to 48. Because of the initial violation of the C fraction’s boundary in the nonlinear model, the undegradable or C fraction was the concentration of the nutrient remaining after 120 h of incubation for each sample type (Warner et al., 2020a). While the B and C fractions, as well as the lag time and rate of disappearance (Kd), were determined via nonlinear regression, the A fraction and effective degradability of each of the nutrients were calculated according to Ørskov and McDonald (1979) using the following equations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

The Kp determined for CON and DGL heifers in the supplementation rate and intake trial were used in the calculation of effective degradability for in situ samples incubated in non-supplemented and supplemented incubation animals, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The comparison of the NIRS analysis of paired samples of loose and extruded DDG was conducted using the mixed procedures of SAS, with the shift within the collection date acting as the random variable. Effects of extrusion on in situ A, B, and C fractions, effective degradability, Kd, and the lag time of DM were analyzed using PROC MIXED with incubation animal within replicate as the random variable.

Effects of incubation animal diet on in situ A, B, and C fractions, effective degradability, Kd, and lag time of hay and DDG cube DM and NDF were analyzed using PROC MIXED with incubation animal within incubation animal diet acting as the random variable.

The particle Kp for the supplementation rate study was determined for each animal by regressing the natural logarithm of TiO2 concentration in feces over sampling time using the regression procedure of SAS (Martínez-Pérez et al., 2013). The parameters for forage and total intake and diet digestibility were analyzed via PROC REG to determine the relationship between actual extruded DDG cube intake and forage intake and digestibility.

All blood parameters were analyzed using PROC MIXED within the hour of the collection as the repeated measure and animal within treatment as the subject. Based upon Akaike Information Criterion values, compound symmetry covariance structure for repeated measures best fit the data for blood parameters and was used within the model (Littell et al., 1998).

Interactions were considered significant at P < 0.10, while main effect differences were deemed significant at P ≤ 0.05, and main effect differences at 0.10 ≥ P > 0.05 were assumed to be tendencies. The LSMEANS statement was used to determine the least-squares means, and the largest standard error is reported.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the effects of extrusion on the chemical composition of DDG

The chemical composition of loose and extruded DDG is presented in Table 2. No differences in ash, NDFD, or ADICP (P ≥ 0.55) were detected between the loose and extruded DDG. The CP content of the extruded DDG was approximately 1 percentage unit less (P = 0.05) than the loose DDG. The fat content of the extruded DDG was greater (P < 0.01) than that of the loose DDG. However, loose DDG had greater NDF and ADF (P ≤ 0.05) concentration than extruded DDG cubes. More specifically, concentrations of NDF and ADF were decreased in extruded DDG by approximately 10% and 15%, respectively. Although lower in fiber content, extruded DDG cubes had greater NDICP (P = 0.01) than loose DDG. As NDICP represents a fraction of RUP (Sniffen et al., 1992), the higher content observed for extruded DDG suggests their protein is more resistant to ruminal breakdown and more protein is likely to bypass the rumen intact to the lower digestive tract. In addition, the calculated TDN was greater (P < 0.01) for extruded DDG cubes by approximately 5 percentage units.

Table 2.

Effect of extrusion on the chemical composition of dried distillers’ grains (DDG)

| Items1 | Loose | Extruded | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition2, %DM | ||||

| CP | 30.89 | 29.93 | 0.398 | 0.05 |

| Fat | 6.12 | 8.51 | 0.114 | < 0.01 |

| NDF | 35.11 | 31.73 | 0.842 | 0.03 |

| ADF | 11.63 | 9.79 | 0.510 | 0.05 |

| Ash | 9.93 | 10.26 | 0.546 | 0.65 |

| NDFD | 77.89 | 79.40 | 1.693 | 0.55 |

| NDICP | 7.31 | 8.12 | 0.158 | 0.01 |

| ADICP | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.024 | 0.84 |

| TDN | 86.83 | 91.38 | 0.638 | < 0.01 |

Items are chemical composition of loose and extruded DDG evaluated via near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy and wet chemistry (CP, fat, NDF, ADF, and ash).

NDF, neutral detergent fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDFD, NDF digestibility; NDICP, ND insoluble CP; ADICP, AD insoluble CP; TDN, total digestible nutrients calculated according to Tedeschi and Fox (2020).

Overall, the increased NDICP and estimated energy content of the extruded DDG indicate they may be nutritionally advantageous over loose DDG. Solanas et al. (2008) evaluated the effects of feedstuff extrusion, and the differences in chemical composition in soybean meal before and after extrusion were minimal. Similar to our study, fiber concentrations were greater in ground corn than in extruded corn based on the reported chemical composition (Alvarado et al., 2009).

Dry matter disappearance data for loose and extruded DDG are presented in Table 3. When comparing disappearance kinetics of loose and extruded DDG, the extruded DDG cubes displayed a greater A fraction (P < 0.01) than the loose DDG for DM. More specifically, extruded DDG cubes had a 2.0 percentage unit greater A fraction of DM than loose DDG. The A fractions observed in the current study were approximately 23% greater than observations by Winterholler et al. (2009) for loose DDG and 25% greater for extruded compared with that observed by Winterholler et al. (2009). A greater B fraction (P = 0.04) was observed for loose DDG compared with extruded DDG, with 40.9% and 39.0% of DM disappearing at a fractional rate, respectively. There was no difference (P = 0.87) in the C fraction, or ruminally undegradable fractions, of DM. The effective degradability of DM was approximately 2.2 percentage units greater (P < 0.01) for the extruded DDG than the loose DDG, which was likely associated with the greater A fraction of extruded DDG cubes. There was a tendency (P = 0.07) for the Kd of DM to be faster for extruded DDG than for loose DDG (2.1% and 2.0% per h, respectively). In a study comparing grain processing methods, the DM Kd of extruded grains was faster than that of dry-rolled grains (Gaebe et al., 1998). The lag time of DM disappearance was significantly greater (P < 0.01) for extruded DDG cubes when compared with loose DDG, with 7.3 and 2.9 h lag times, respectively. Although the A fraction of DM was much greater than that observed by Winterholler et al. (2009), both the Kd and effective degradability in the current study was similar to that observed by their lab regardless of the supplement form.

Table 3.

In situ DM disappearance of loose and extruded dried distillers’ grains (DDG)

| Item1 | Loose | Extruded | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM disappearance, %DM | ||||

| A fraction | 40.36a | 42.33b | 0.555 | <0.01 |

| B fraction | 40.93b | 39.08a | 0.833 | 0.04 |

| C fraction | 18.70 | 18.58 | 0.784 | 0.87 |

| ED | 57.98a | 59.77b | 0.879 | <0.01 |

| Kd, %/h | 2.01a | 2.14b | 0.108 | 0.07 |

| Lag time, h | 2.97a | 7.39b | 1.611 | <0.01 |

Disappearance kinetics: A fraction, immediately soluble; B fraction, fractional disappearance rate; C fraction, undegradable; ED, effective degradability; Kd, disappearance rate (Orskov and McDonald, 1979).

Least-squares means followed by different superscripts differ within rows (P < 0.05).

Effect of supplementation rate on intake and digestibility

Intake and digestibility of hay and diet

There was no relationship (P = 0.41; r2 = 0.03) between supplementation rate and FO (Figure 1). However, particulate Kp increased linearly (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.50), ranging from 2.46% to 3.34% per h with increased inclusion of supplemental DDG cubes (Figure 2). This agrees with McCollum and Galyean (1985a), who reported increased Kp of prairie hay with an increased supplementation rate. In general agreeance with our results, Guthrie and Wagner (1988) observed a linear increase in forage Kp with increased inclusion of supplemental protein; however, they found the increase in Kp to be highly correlated with increases in forage intake. As forage intake was reduced with supplemental DDG cubes in our study, the increase in Kp is likely related to the greater total DMI and greater protein content of the total diet (McCollum and Galyean, 1985b; Guthrie and Wagner, 1988).

Figure 1.

Linear effect of supplemental dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube intake on fecal output (P = 0.41; y = −0.1880x + 3.1983; r2 = 0.03). Circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d.

Figure 2.

Linear effect of supplemental dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube intake on particle passage rate (P < 0.01; y = 0.6913x + 2.5480; r2 = 0.50). Circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d.

Forage DMI decreased linearly with increasing supplementation rate (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.51), whereas total diet DMI increased linearly (P = 0.01; r2 = 0.29) with increased supplemental DDG cubes (Figure 3A and B, respectively). Positive associative effects of increased forage digestibility and intake are most commonly associated with providing rumen degradable protein (RDP) to protein-deficient forage diets with low CP and TDN:CP ratio >7:1 (Moore et al., 1999). However, the hay used in the current experiment was not deficient in RDP (Table 1) and the TDN:CP ratio would be considered balanced (5.7:1) based on Moore et al. (1999). Decreased forage DMI due to supplementation has been attributed to a forage TDN:CP ratio <7, and is typically observed when cattle consume forages adequate in RDP (Moore et al., 1999). Thus, the reduction in hay DMI with supplementation of DDG cubes in our study may be due to the TDN:CP ratio of 5.7 for the bermudagrass hay. In a meta-analysis, Griffin et al. (2012) reported a similar quadratic decrease in forage intake with an increased loose DDG supplementation rate. Additionally, Morris et al. (2005) observed decreased forage DMI and a forage replacement rate of −0.32 when loose supplemental DDG were fed to cattle consuming smooth bromegrass. In other studies that related forage intake to supplemental concentrate, forage replacement ranged from approximately −0.33 to −0.50 (Garcés-Yépez et al., 1997; MacDonald et al., 2007). Overall, the forage replacement rate of −1.78 observed in the current study is greater than that reported in similar studies and is due to the low-quality forage and high-quality supplemental DDG cubes.

Figure 3.

Effects of supplemental dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube intake on (A) hay DMI (linear; P < 0.01; y = −1.7800x + 5.3679; r2 = 0.51) and (B) total diet DMI (linear; P = 0.01; y = 1.1484x + 5.3699; r2 = 0.29). Circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d.

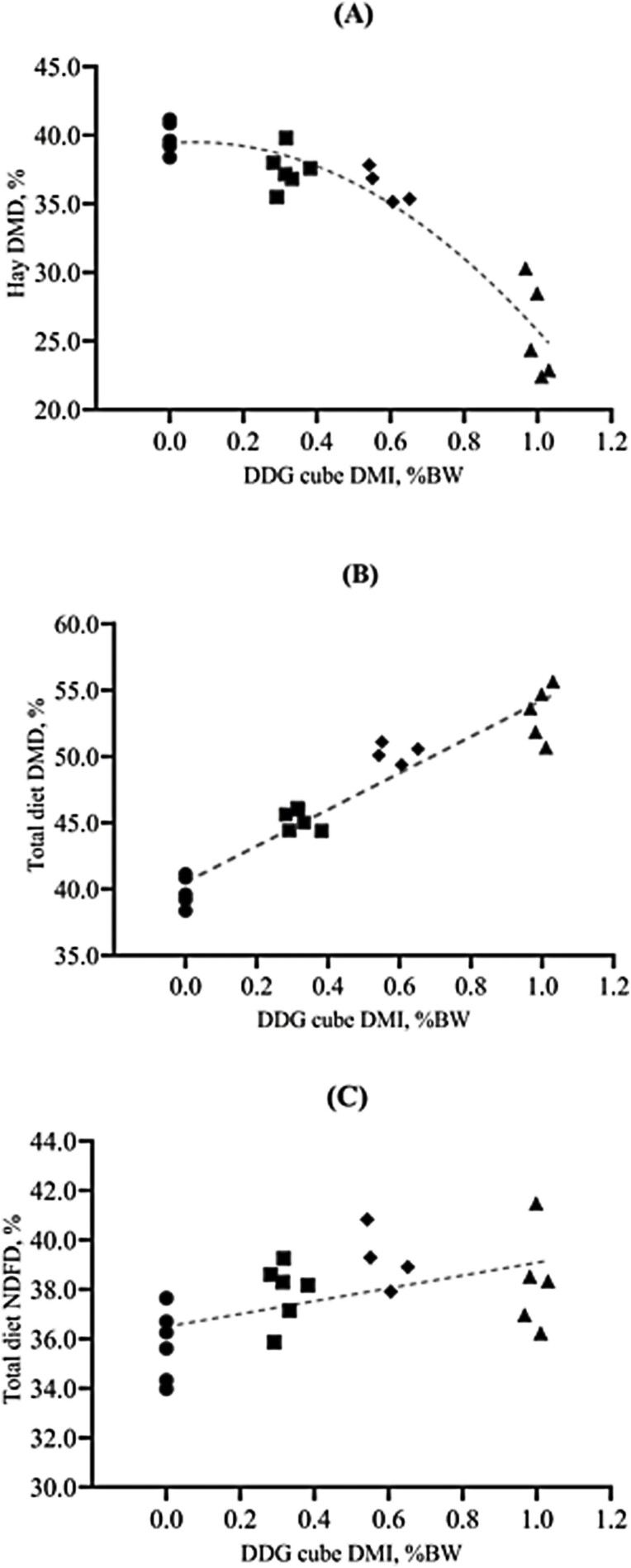

Forage DMD was strongly associated with DDG cube intake (r2 = 0.90), and a quadratic decrease (P < 0.01) was observed with a greater supplementation rate (Figure 4A). However, increased inclusion of supplemental DDG cubes resulted in a linear increase (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.91) in total diet DMD, with DGH having 17.42% greater diet digestibility than CON (Figure 4B). It has been noted that increased diet digestibility, with consumed energy in excess of nutritive energy required by the animal, would result in decreased DMI (Ellis, 1978). As indicated by the reduced forage DMI with increased supplemental DDGS, the supplemented animals required less energy from the forage due to supplemental energy and increased diet digestibility. Total diet NDFD increased linearly (P = 0.01; r2 = 0.27) with increased rate of supplementation (Figure 4C). When DelCurto et al. (1990) evaluated the effects of supplemental protein concentration on NDFD for steers consuming low-quality hay, a quadratic response was observed with moderate (24.7% CP) and high (41.3% CP) supplements improving NDFD by 30% compared with the low (12.4% CP) supplement. Although Chase and Hibberd (1987) detected a cubic decrease in NDFD with an increased rate of corn supplementation for beef cows consuming native hay, the greatest reduction occurred as corn inclusion was increased from 1 to 2 kg/d and could be attributed to the increase in starch. As corn grain is generally higher in starch content than DDG cubes, the positive linear relationship between total diet NDFD and DDG cube supplementation rate in the current study was likely a result of generally lower supplementation rates and starch content.

Figure 4.

Effects of supplemental dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube intake on (A) hay DMD (quadratic; P < 0.01; y = −15.8044x2 + 2.1320x + 39.4136; r2 = 0.90), (B) total diet DMD (linear; P < 0.01; y = 13.7304x + 40.5147; r2 = 0.91), (C) total diet NDFD (linear; P = 0.01; y = 2.5911x + 36.4947; r2 = 0.27). Circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d.

In situ DM and NDF disappearance of hay and supplement

The disappearance of DM and NDF of hay and extruded DDG cubes fed during the supplementation rate experiment is displayed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. There was no effect of incubation animal supplementation (P ≥ 0.25) on any variable of DM disappearance of the hay (Table 4) or DDG cubes (Table 5) fed throughout the trial. As the hay and DDG cube samples were comingled within the rumen during incubation, it was not unexpected to observe those lack of differences in DM disappearance due to the diet of the incubation animal.

Table 4.

Effects of incubation animal diet on in situ DM and NDF disappearance of bermudagrass hay

| Items1 | Diet2 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-supplemented | Supplemented | |||

| DM disappearance, %DM | ||||

| A fraction | 19.18 | 18.78 | 1.321 | 0.85 |

| B fraction | 29.58 | 28.83 | 1.499 | 0.75 |

| C fraction | 51.23 | 52.38 | 0.927 | 0.47 |

| ED | 34.10 | 32.51 | 0.272 | 0.35 |

| Kd, %/h | 2.55 | 2.58 | 0.272 | 0.94 |

| Lag time, h | 4.37 | 2.39 | 2.289 | 0.60 |

| NDF disappearance, %DM | ||||

| A fraction | 29.46a | 31.10b | 0.345 | 0.07 |

| B fraction | 26.29 | 24.28 | 0.688 | 0.17 |

| C fraction | 44.23 | 44.61 | 0.359 | 0.53 |

| ED | 43.25 | 44.02 | 0.631 | 0.47 |

| Kd, %/h | 2.76 | 3.22 | 0.312 | 0.41 |

| Lag time, h | 7.97 | 13.28 | 2.340 | 0.24 |

Disappearance kinetics: A fraction, immediately soluble; B fraction, fractional disappearance rate; C fraction, undegradable; ED, effective degradability; Kd, disappearance rate (Orskov and McDonald, 1979).

Incubation animal diet: Non-supplemented, received no supplemental DDG cubes during in situ incubation period; Supplemented, received 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d during in situ incubation period.

Least-squares means followed by different superscripts differ within rows (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Effects of incubation animal diet on in situ DM and NDF disappearance of supplemental extruded dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cubes

| Items1 | Diet2 | SEM | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-supplemented | Supplemented | |||

| DM disappearance, %DM | ||||

| A fraction | 39.13 | 39.63 | 0.940 | 0.74 |

| B fraction | 40.01 | 36.27 | 1.891 | 0.29 |

| C fraction | 20.85 | 24.09 | 1.456 | 0.25 |

| ED | 57.61 | 55.71 | 1.604 | 0.49 |

| Kd, %/h | 2.15 | 2.23 | 0.188 | 0.79 |

| Lag time, h | 5.42 | 13.43 | 3.670 | 0.26 |

| NDF disappearance, %DM | ||||

| A fraction | 57.39 | 57.08 | 0.234 | 0.44 |

| B fraction | 35.08 | 35.38 | 1.408 | 0.89 |

| C fraction | 7.51 | 7.53 | 1.203 | 0.99 |

| ED | 77.33 | 74.85 | 1.899 | 0.45 |

| Kd, %/h | 3.36 | 2.83 | 0.552 | 0.57 |

| Lag time, h | 12.63 | 15.91 | 3.193 | 0.54 |

Disappearance kinetics: A fraction, immediately soluble; B fraction, fractional disappearance rate; C fraction, undegradable; ED, effective degradability; Kd, disappearance rate (Orskov and McDonald, 1979).

Incubation animal diet: Non-supplemented, received no supplemental DDG cubes during in situ incubation period; Supplemented, received 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d during in situ incubation period.

Least-squares means followed by different superscripts differ within rows (P < 0.05).

However, there was a tendency for the A fraction (P = 0.07) of hay NDF to be greater when the incubation animal received supplemental DDG cubes. Similar to DM disappearance, the remaining variables of NDF disappearance for hay were not affected (P ≥ 0.17) by incubation animal diet. Furthermore, no effect of incubation animal treatment (P = 0.44) was observed for any variable of NDF disappearance of the DDG cubes.

Blood metabolites

A treatment × hour interaction (P = 0.07) was present for BUN concentration, with supplemented animals having greater concentrations 4 h following supplementation compared with CON (Figure 5). More specifically, supplemented heifers had approximately 2.7 mg/dL greater BUN concentrations 4 h after consuming supplemental DDG than those not supplemented. Similar to our results, Cappellozza et al. (2014a) observed increased plasma urea nitrogen concentrations in beef heifers following protein supplementation compared with control animals. As rumen ammonia and BUN are generally related, our results indicated that increased BUN concentration in supplemented animals may be due to rumen ammonia concentration reaching a peak level approximately 4 h postprandial (Lewis, 1957). Additionally, intake of dietary CP and RDP have been reported to be positively associated with BUN concentration (Broderick and Clayton, 1997). Although our observed BUN concentrations followed the same trend as seen in similar studies, the relatively low concentrations in the current study may be due to the short supplementation period (Hammond, 1997).

Figure 5.

Effects of dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube supplementation rate on blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration in heifers consuming bermudagrass hay (circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d; Time = hour of blood collection in relation to time of supplementation). Treatment × time interaction, P = 0.07. Treatment effect, P = 0.01. Time effect, P < 0.01.

Serum NEFA concentrations displayed a treatment × hour interaction (P < 0.01), with DGH and DGI having significantly lower concentrations 4 and 8 h post-supplementation compared to CON at the same time points (Figure 6). Cappellozza et al. (2014b) also observed lower NEFA concentrations in beef heifers that provided supplemental protein or energy compared to those not supplemented. In further agreeance with our study, cows consuming prairie hay and provided supplemental RUP had lower plasma NEFA concentrations than cows only consuming the low-quality hay (Sletmoen-Olson et al., 2000). When the energy requirements of animals are not met by the diet, adipose tissue is mobilized to meet the energy requirements and can be indicated by increased concentrations of NEFA in the blood (Bowden, 1971). Thus, CON heifers having approximately 230% and 80% greater concentrations of NEFA 4 and 8 h following supplementation, respectively, compared with DGI and DGH suggests that the hay alone did not supply enough energy to meet animal requirements and that the additional energy provided by the extruded DDG cubes was adequate to do so.

Figure 6.

Effects of dried distillers’ grain (DDG) cube supplementation rate on serum nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) concentration in heifers consuming bermudagrass hay (circle = no supplementation, square = 0.90 kg DDG cubes per d, diamond = 1.81 kg DDG cubes per d, triangle = 3.62 kg DDG cubes per d; Time = hour of blood collection in relation to time of supplementation). Treatment × time interaction, P < 0.01. Treatment effect, P < 0.01. Time effect, P < 0.01.

Regardless of treatment, glucose concentrations were greatest (P < 0.01) and lactate concentrations tended to be greater (P = 0.06) immediately before supplementation and 8 h post-supplementation (Table 6). The similar trends in glucose and lactate concentrations with respect to time are likely due to lactate being a product of glucose metabolism, which has also been observed in feedlot steers (Warner et al., 2020b). Reilly and Chandrasena (1978) further supported our results as they determined an interrelationship between glucose and lactate concentrations by evaluating their kinetic parameters in sheep.

Table 6.

Effect of dried distillers’ grains (DDG) cube supplementation rate on blood glucose and lactate concentrations

| Item | Treatment1 | SEM2 | P-value | Hour3 | SEM | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | DGL | DGI | DGH | 0 | 4 | 8 | |||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 60.35 | 67.31 | 68.82 | 69.62 | 3.709 | 0.23 | 67.46b | 61.83a | 70.28b | 2.129 | <0.01 |

| Lactate, mg/dL | 18.43 | 26.11 | 33.94 | 31.85 | 6.429 | 0.29 | 27.59ab | 22.75a | 32.40b | 3.793 | 0.06 |

Supplemental treatment: CON, no supplement; DGL, DDG cubes at 0.90 kg/d; DGI, DDG cubes at 1.81 kg/d; DGH, DDG cubes at 3.62 kg/d.

Group variances are estimated separately, the largest SEM is reported.

Hour of blood collection: 0, before supplementation; 4, 4 h post-supplementation; 8, 8 h post-supplementation.

Least-squares means followed by different superscripts differ within rows (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

In conclusion, increasing DDG cube supplementation to calves consuming bermudagrass hay may reduce forage intake and increase diet digestibility. In addition, our results suggest that extruded DDG cubes are an adequate supplement for calves consuming moderate-quality hay due to the increased supply of energy and may be helpful in grazing systems with high-quality forages. Future research is warranted to evaluate the ability of DDG cubes to allow for increased stocking rates in grazing systems and overall increased productivity.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Animal Science online.

Acknowledgments

This experiment was funded in part by gifts of supplemental feed from MasterHand Milling Inc. (Lexington, NE), the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station of the Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources at Oklahoma State University, and the Dennis and Marta White Endowed Chair in Animal Science.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADF

acid detergent fiber

- ADICP

acid detergent insoluble crude protein

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CP

crude protein

- DDG

dried distillers’ grains

- DM

dry matter

- DMD

DM digestibility

- DMI

DM intake

- DMR

DM remaining

- FO

fecal output

- iNDF

indigestible neutral detergent fiber

- Kd

rate of digestion

- Kp

rate of passage

- ND

neutral detergent

- NDF

neutral detergent fiber

- NDFD

NDF digestibility

- NDFR

NDF remaining

- NDICP

ND insoluble crude protein

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

- NIRS

near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- PPR

particulate passage rate

- RDP

rumen degradable protein

- RPM

rotations per minute

- RUP

rumen undegradable protein

- TDN

total digestible nutrients

- TiO2

titanium dioxide

- XRF

X-ray fluorescence

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams, J. M., Norris A. B., Dias Batista L. F., Rivera M. E., and Tedeschi L. O.. . 2020. Comparison of in situ techniques to evaluate the recovery of indigestible components and the accuracy of digestibility estimates. J. Anim. Sci. 98:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, C., Anrique R., and Navarrete S.. . 2009. Effect of including extruded, rolled or ground corn in dairy cow diets based on direct cut silage. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 69:356–365. doi: 10.4067/S0718-58392009000300008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. 2000. Official methods of analysis, 17th ed. Gaithersburg (MD): The Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS Official Procedure. 2005. Approved procedure Am 5-04, rapid determination of oil/fat utilizing high temperature solvent extraction. Urbana (IL): American Oil Chemists’ Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, D. M. 1971. Non-esterified fatty acids and ketone bodies in blood as indicators of nutritional status in ruminants: a review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 51:1–13. doi: 10.4141/cjas71-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson, G. J., Pigden W. J., and Sylvestre P. E.. . 1956. Effect of frequency of administration of chromic oxide on its fecal excretion pattern by grazing cattle. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 37:90–94. doi: 10.4141/cjas57-013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick, G. A., and Clayton M. K.. . 1997. A statistical evaluation of animal and nutritional factors influencing concentrations of milk urea nitrogen. J. Dairy Sci. 80:2964–2971. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76262-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellozza, B. I., Cooke R. F., Guarnieri Filho T. A., and Bohnert D. W.. . 2014a. Supplementation based on protein or energy ingredients to beef cattle consuming low-quality cool-season foraged: i. Forage disappearance parameters in rumen-fistulated steers and physiological responses in pregnant heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 92:2716–2724. doi: 10.2527/jas2013-7441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellozza, B. I., Cooke R. F., Reis M. M., Moriel P., Keisler D. H., and Bohnert D. W.. . 2014b. Supplementation based on protein or energy ingredients to beef cattle consuming low-quality cool-season forages: II. Performance, reproductive, and metabolic responses of replacement heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 92:2725–2734. doi: 10.2527/jas2013-7442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase, C. C., and Hibberd C. A.. . 1987. Utilization of low-quality native grass hay by beef cows fed increasing quantities of corn grain. J. Anim. Sci. 65:557–566. doi: 10.2527/jas1987.652557x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Yang Z., and Han L.. . 2013. A review of the use of near-infrared spectroscopy for analyzing feed protein materials. Appl. Spectroc. Rev 48:509–522. doi: 10.1080/05704928.2012.756403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DelCurto, T., Cochran R. C., Harmon D. L., Beharka A. A., Jacques K. A., Towne G., and Vanzant E. S.. . 1990. Supplementation of dormant tallgrass-prairie forage: i. Influence of varying supplemental protein and(or) energy levels on forage utilization characteristics of beef steers in confinement. J. Anim. Sci. 68:515–531. doi: 10.2527/1990.682515x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst, R. J., Hepper D., and Webster A. J. F.. . 1995. Comparison of in sacco and in vitro techniques for estimating the rate and extent of rumen fermentation of a range of dietary ingredients. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 51:211–229. doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(94)00692-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, W. C. 1978. Determinants of grazed forage intake and digestibility. J. Dairy Sci. 61:1828–1840. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(78)83809-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, J. M. 1986. The voluntary food intake of farm animals. Butterworths (LDN): Butterworths & Co. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés-Yépez, P., Kunkle W. E., Bates D. B., Moore J. E., Thatcher W. W., and Sollenberger L. E.. . 1997. Effects of supplemental energy source and amount on forage intake and performance by steers and intake and diet digestibility by sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 75:1918–1925. doi: 10.2527/1997.75719118x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebe, R. J., Sanson D. W., Rush I. G., Riley M. L., Hixon D. L., and Paisley S. I.. . 1998. Effects of extruded corn or grain sorghum on intake, digestibility, weight gain, and carcasses of finishing steers. J. Anim. Sci. 76:2001–2007. doi: 10.2527/1998.7682001x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, W. A., Bremer V. R., Klopfenstein T. J., Stalker L. A., Lomas L. W., Moyer J. L., and Erickson G. E.. . 2012. A meta-analysis evaluation of supplementing dried distillers’ grains plus solubles to cattle consuming forage-based diets. Prof. Anim. Sci. 28:306–312. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30360-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, M. J., and Wagner D. G.. . 1988. Influence of protein or grin supplementation and increasing levels of soybean meal on intake, utilization and passage rate of prairie hay in beef steers and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 66:1529–1537. doi: 10.2527/jas1988.661529x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, A. 1997. Update on BUN and MUN as a guide for protein supplementation in cattle. In: Proceedings in Florida Ruminant Nutr. Symp., Univ. Florida, Gainesville; p. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kartchner, R. J. 1980. Effects of protein and energy supplementation of cows grazing native winter range forage on intake and digestibility. J. Anim. Sci. 51:432–438. doi: 10.2527/jas1980.512432x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krizsan, S. J., and Huhtanen P.. . 2013. Effect of diet composition and incubation time on feed indigestible neutral detergent fiber concentration in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 96:1715–1726. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkle, W. E., Johns J. T., Poore M. H., and Herd D. B.. . 2000. Designing supplementation programs for beef cattle fed forage-based diets. J. Anim. Sci. 77:1–11. doi: 10.2527/jas2000.00218812007700ES0012x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. 1957. Blood-urea concentration in relation to protein utilization in the ruminant. J. Agric. Sci. 48:438–446. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600032962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littell, R. C., Henry P. R., and Ammerman C. B.. . 1998. Statistical analysis of repeated measures data using SAS procedures. J. Anim. Sci. 76:1216–1231. doi: 10.2527/1998.7641216x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, J. C., Klopfenstein T. J., Erickson G. E., and Griffin W. A.. . 2007. Effects of dried distillers grains and equivalent undegradable intake protein or ether extract on performance and forage intake of heifers grazing smooth bromegrass pastures. J. Anim. Sci. 85:2614–2624. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, W. H., Fingerhut B., and Miller H.. . 1965. Automated and direct methods for the determination of blood urea. Clin. Chem. 11:624–627. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/11/6/624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pérez, M. F., Calderón-Mendoza D., Islas A., Encinias A. M., Loya-Olguín F., and Soto-Navarro S. A.. . 2013. Effect of corn dry distiller grains plus solubles supplementation level on performance and digestion characteristics of steers grazing native range during forage growing season. J. Anim. Sci. 91:1350–1361. doi: 10.2527/jas2012-5251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum, F. T., and Galyean M. L.. . 1985a. Influence of cottonseed meal supplementation on voluntary intake, rumen fermentation and rate of passage of prairie hay in beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 60:570–577. doi: 10.2527/jas1985.602570x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum, F. T., and Galyean M. L.. . 1985b. Cattle grazing blue grama rangeland II. Seasonal forage intake and digesta kinetics. J. Range Manage. 38:543–546. doi: 10.2307/3899749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. E., Brant M. H., Kunkle W. E., and Hopkins D. I.. . 1999. Effects of supplementation on voluntary forage intake, diet digestibility, and animal performance. J. Anim. Sci. 77:122–135. doi: 10.2527/1999.77suppl_2122x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S., Klopfenstein T. J., Adams D. C., Erickson G. E., and Vander Pol K. J.. . 2005. The effects of dried distillers grains on heifers consuming low or high quality forage. Nebr. Beef Rep. MP83-A:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, A. B., Tedeschi L. O., and Muir J. P.. . 2019. Assessment of in situ techniques to determine indigestible components in the feed and feces of cattle receiving supplemental condensed tannins. J. Anim. Sci. 97:5016–5026. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørskov, E. R., and McDonald I.. . 1979. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci 92:499–503. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600063048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, F. N., and Hanson C. F.. . 1992. External and internal markers for appraising site and extent of digestion in ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 75:2605–2617. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78023-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, P. E. B., and Chandrasena L. G.. . 1978. Glucose lactate interrelations in sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 235:E487–E492. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.5.E487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletmoen-Olson, K. E., Caton J. S., Olson K. C., Redmer D. A., Kirsch J. D., and Reynolds L. P.. . 2000. Undegraded intake protein supplementation: II. Effects on plasma hormone and metabolite concentrations in periparturient beef cows fed low-quality hay during gestation and lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 78:456–463. doi: 10.2527/2000.782456x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniffen, C. J., O’Connor J. D., Van Soest P. J., Fox D. G., and Russell J. B.. . 1992. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets: II. Carbohydrate and protein availability. J. Anim. Sci. 70:3562–3577. doi: 10.2527/1992.70113562x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanas, E. M., Castrillo C., Jover M., and de Vega A.. . 2008. Effect of extrusion on in situ ruminal protein degradability and in vitro digestibility of undegraded protein from different feedstuffs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 88:2589–2597. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiehs, M. J., Whitney M. H., and Shurson G. C.. . 2002. Nutrient database for distiller’s dried grains with solubles produced from new ethanol plants in Minnesota and South Dakota. J. Anim. Sci. 80:2639–2645. doi: 10.1093/ansci/80.10.2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock, R., Lewis J. M., Klopfenstein T. J., and Milton C. T.. . 1999. Review of new information on the use of wet and dry milling feed by-products in feedlot diets. Faculty Papers and Publications in Animal Science; 555. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, L. O., and Fox D. G.. . 2020. The ruminant nutrition system: volume I – an applied model for predicting nutrient requirements and feed utilization in ruminants, 3rd ed. Ann Arbor (MI): XanEdu. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L. R., Beck M. R., Gunter S. A., Williams G. D., Place S. E., and Reuter R. R.. . 2019. An energy supplement with monensin reduces methane emission intensity of stocker cattle grazing winter wheat. Prof. Anim. Sci. 35:433–440. doi: 10.15232/aas.2018-01841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P. J. 1994. Nutritional ecology of the ruminant, 2nd ed. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P. J., Robertson J. B., and Lewis B. A.. . 1991. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner, A. L., Beck P. A., Foote A. P., Pierce K. N., Robison C. A., Hubbell D. S., and Wilson B. K.. . 2020b. Effects of utilizing cotton byproducts in a finishing diet on beef cattle performance, carcass traits, fecal characteristics, and plasma metabolites. J. Anim. Sci. 98:1–9. doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner, A. L., Beck P. A., Foote A. P., Pierce K. N., Robison C. A., Stevens N. E., and Wilson B. K.. . 2020a. Evaluation of ruminal degradability and metabolism of feedlot finishing diets with or without cotton byproducts. J. Anim. Sci. 98:1–10. doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterholler, S. J., Lalman D. L., Dye T. K., McMurphy C. P., and Richards C. J.. . 2009. In situ ruminal degradation characteristics of by-product feedstuffs for beef cattle consuming low-quality forage. J. Anim. Sci. 87:2996–3002. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterholler, S. J., McMurphy C. P., Mourer G. L., Krehbiel C. R., Horn G. W., and Lalman D. L.. . 2012. Supplementation of dried distillers grains with solubles to beef cows consuming low-quality forage during late gestation and early lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 90:2014–2025. doi: 10.2527/jas2011-4152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebeli, Q., Dunn S. M., and Ametaj B. N.. . 2010. Strong associations among rumen endotoxin and acute phase proteins with plasma minerals in lactating cows fed graded amounts of concentrate. J. Anim. Sci. 88:1545–1553. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.