Keywords: exercise, obesity, oxidative metabolism, placenta, PRDM16

Abstract

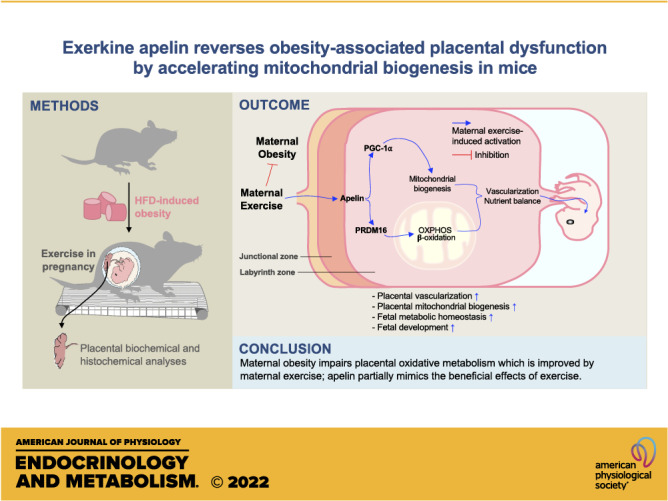

Maternal exercise (ME) protects against adverse effects of maternal obesity (MO) on fetal development. As a cytokine stimulated by exercise, apelin (APN) is elevated due to ME, but its roles in mediating the effects of ME on placental development remain to be defined. Two studies were conducted. In the first study, 18 female mice were assigned to control (CON), obesogenic diet (OB), or OB with exercise (OB/Ex) groups (n = 6); in the second study, the same number of female mice were assigned to three groups; CON with PBS injection (CD/PBS), OB/PBS, or OB with apelin injection (OB/APN). In the exercise study, daily treadmill exercise during pregnancy significantly elevated the expression of PR domain 16 (PRDM16; P < 0.001), which correlated with enhanced oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis in the placenta (P < 0.05). More importantly, these changes were partially mirrored in the apelin study. Apelin administration upregulated PRDM16 protein level (P < 0.001), mitochondrial biogenesis (P < 0.05), placental nutrient transporter expression (P < 0.001), and placental vascularization (P < 0.01), which were impaired due to MO (P < 0.05). In summary, MO impairs oxidative phosphorylation in the placenta, which is improved by ME; apelin administration partially mimics the beneficial effects of exercise on improving placental function, which prevents placental dysfunction due to MO.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Maternal exercise prevents metabolic disorders of mothers and offspring induced by high-fat diet. Exercise intervention enhances PRDM16 activation, oxidative metabolism, and vascularization of placenta, which are inhibited due to maternal obesity. Similar to maternal exercise, apelin administration improves placental function of obese dams.

INTRODUCTION

Presently, the rates of pregnant women with obesity have risen in the United States (1), and obesity in pregnancy is a key risk factor impairing fetal development and predisposing offspring to metabolic dysfunctions later in life (2). The placenta is an important organ that is responsible for supplying oxygen and nutrients to the fetus and also mediates maternal metabolism through secreting hormones and cytokines (3). In animal studies, maternal obesity (MO) impedes vascularization and homeostasis of nutrient transporters in the placenta (4, 5), which impairs fetal development (5). In clinical trials, maternal obesity suppresses mitochondrial oxidative function and ATP production predominantly in males (6) and elevates oxidative stress in the placenta (7). Because developing cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts require a high energy supply, insufficient ATPs due to maternal obesity impairs placental function (8–10). Besides, mitochondria are also the sites of generating metabolites for hormone synthesis in the placenta, which is hampered due to maternal obesity (6). Thus, enhancing the placental oxidative function of mothers with obesity is critical for improving fetal development and the long-term metabolic health of offspring.

Exercise during pregnancy is one of the strategies for improving placental/fetal development impaired due to high-fat diet (HFD) feeding during pregnancy in animal models (5, 11, 12). We previously found that maternal exercise (ME) improves mitochondrial biogenesis in fetal brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle (13, 14). Furthermore, maternal exercise has long-term effects on prevention of the metabolic disorder in offspring mice born to obese mothers (15, 16). Of note, maternal exercise improves mitochondrial biogenesis in fetal skeletal muscle of dams fed HFD, which prevents offspring metabolic dysfunction (17). In our previous study, we found that maternal exercise improves placental development of mothers with obesity (5), though mechanisms remain to be established.

Apelin (APN) is a newly discovered cytokine stimulated by exercise, so called exerkine (18, 19). It is a ligand of a G-protein-coupled apelin receptor (APLNR or APJ; 20). Activation of APJ signaling stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis via upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (Ppargc1a or PGC-1α) in the brown fat and skeletal muscle (14, 21). Interestingly, we recently found that maternal exercise profoundly stimulates apelin secretion by the placenta (5), whereas the role of apelin on placental mitochondrial metabolism remains to be examined. Thus, in the current study, we suggest that apelin mediates the upregulation of placental mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation due to maternal exercise. In addition, PR domain 16 (PRDM16) is a key transcription factor driving mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in brown fat (22, 23). Furthermore, PRDM16 stimulates fatty acid oxidation (24). These discoveries prompted us to hypothesize that exercise during pregnancy induces placental PRDM16 expression, mitochondrial biogenesis, and oxidative metabolism in the placenta of mothers with obesity mainly through stimulating APJ signaling; compared with exercise, maternal apelin supplementation can exert similar beneficial effects in improving placental vascularization and nutrient transporter expression of obese dams.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

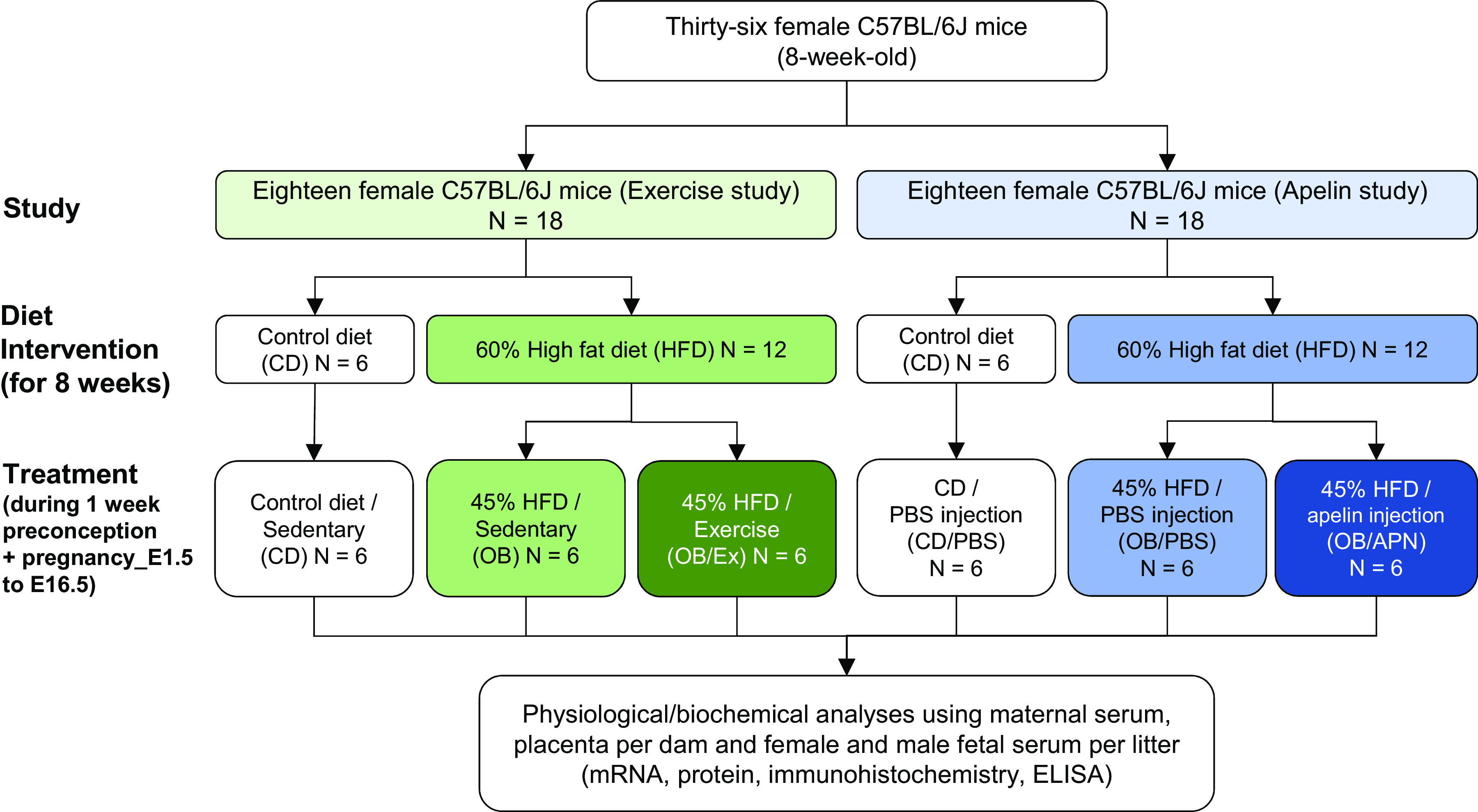

Two animal studies were conducted. For the exercise intervention study, 8-wk-old C57BL/6J female mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were randomly assigned into two groups and fed either a control diet (6 mice; control diet, CD; 10% energy from fat, D12450J; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or a high-fat diet (12 mice; HFD; 60% energy from fat, D12492; Research Diets) for 8 wk to induce obesity. One week before mating, the HFD was replaced with an obesogenic diet (OB; 45% energy from fat, D12451; Research Diets), which was maintained during pregnancy. After mating with age-matched healthy males, obese female mice were further assigned to either sedentary or exercise groups during pregnancy. As a result, there were three groups (CON, n = 6; OB, n = 6; OB/Ex, n = 6).

For apelin administration study, age-matched female mice (8-wk-old) fed a CD or HFD (60% for 8 wk and 45% for 1 wk before mating) were used, and the HFD mice were further randomly assigned for vehicle only (PBS) or apelin administration during pregnancy (CD/PBS, n = 6; OB/PBS, n = 6; OB/APN, n = 6). [Pyr1]apelin-13 (0.5 µmol/kg/day, AAPPTec, Louisville, KY) or PBS was intraperitoneally (ip) injected daily during pregnancy (E1.5 to E16.5), as described in a previous study (25). Vaginal smears were examined to determine the success of mating. All animals were fed ad libitum. After mating, maternal mice were housed individually under 12:12 h light/dark cycle at 22°C (Fig. 1). Food intake was determined. Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (26, 27). All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Washington State University.

Figure 1.

Experimental designs for two independent mouse studies.

Treadmill Exercise Protocol

Pregnant obese mice were subjected to daily treadmill exercise at the same time every morning as described previously (28). Briefly, before mating, treadmill running exercise training was conducted in all female mice at a flat degree, with a speed of 10 m/min for 10 min, three times during a week, which allowed mice to be adapted to exercise. After mating, maternal mice were undergone daily treadmill exercise; depending on gestational progress, exercise intensity was adjusted as follows: E1.5 to E7.5 [40% of maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max), 10 m/min], E8.5 to E 14.5 (65%, 13 m/min), and E15.5 to E16.5 (50%, 12 m/min). Each bout of exercise included warming up (5 m/min for 10 min), main exercise (10–13 m/min for 40 min), and cooling down (5 m/min for 10 min).

Tissue and Blood Collection

At E18.5, after 5 h of fasting, pregnant mice were anesthetized by carbon dioxide inhalation and cervical dislocation (29). Then, maternal blood samples were collected via cardiopuncture under deep anesthesia by carbon dioxide inhalation. In addition, fetal blood was collected through the retro-orbital sinus as described previously (13). Fetuses and all placenta per dam were collected as previously described (5). Fetal sex was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; 30), and fetal samples were pooled based on sex. On the other hand, all placenta of a single litter were pooled together, and each pregnancy was considered as an experimental unit. Maternal physiological changes due to exercise have been previously reported (5).

Serum Analysis

Serum glucose was measured with a Contour blood glucose monitoring system (Bayer HealthCare, Mishawaka, IN), and insulin concentration was measured (%coefficient of variation; means ± SD; 8.12 ± 5.96) using a mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index was calculated based on the following formula: HOMA-IR = fasting insulin (ng/mL) × fasting blood glucose (mg/dL)/405 (31, 32). Serum triglyceride (TG) levels were further analyzed (%coefficient of variation; means ± SD; 2.23 ± 2.76) using a TG colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Gene Expression and Single Cell RNA Sequencing Data Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from placenta using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). RNA integrity was assessed using Nano-Drop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and cDNA was synthesized using extracted RNA with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative measurement of mRNA expression was performed by quantitative real-time PCR (IQ5; Bio-Rad) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Target genes were normalized using 18S rRNA (33), which correlates with total RNA content and remained stable across the groups. Target primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The qPCR experiments followed the minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines (34).

Table 1.

qPCR primer sequences

| Gene Name | Forward/Reverse | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Prdm16 | F | 5'-TGTGCGAAGGTGTCCAAACT-3' |

| R | 5'-AACGTCACCGTCACTTTTGG-3' | |

| Ppargc1a | F | 5'-CCATACACAACCGCAGTCGC-3' |

| R | 5'-GTGGGAGGAGTTAGGCCTGC-3' | |

| Tfam | F | 5'-CCAAAAAGACCTCGTTCAGC-3' |

| R | 5'-CTTCAGCCATCTGCTCTTCC-3' | |

| Cox7a1 | F | 5'-CAGCGTCATGGTCAGTCTGT-3' |

| R | 5'-AGAAAACCGTGTGGCAGAGA-3' | |

| Nrf1 | F | 5'-GCACCTTTGGAGAATGTGGT-3' |

| R | 5'-CTGAGCCTGGGTCATTTTGT-3' | |

| Cpt1a | F | 5'-TCGCTCATTCCGCCGC-3' |

| R | 5'-GAGATCGATGCCATCAGGGG-3' | |

| Cpt2 | F | 5'-TTCTGCAGTGCGGTTTCTGA-3' |

| R | 5'-GTGTCACTTCTGGCAGGGTT-3' | |

| Acadm | F | 5'-AGGGTTTAGTTTTGAGTTGACGG-3' |

| R | 5'-CCCCGCTTTTGTCATATTCCG-3' | |

| Acaa2 | F | 5'-GAACGAAGCTTTTGCCCCTC-3' |

| R | 5'-CTTTCCACCTCGACGCCTTA-3' | |

| Hadh | F | 5'-CCATCTTTGCCAGCAACACG-3' |

| R | 5'-GCACGGGGTTGAAAAAGTGG-3' | |

| Glut1 | F | 5'-GCGGGAGACGCATAGTTACA-3' |

| R | 5'-CAGCCCCGTTACTCACCTTG-3' | |

| Snat1 | F | 5'-GGGCATAAGGTACACCGAGG-3' |

| R | 5'-CAACGTGCACCTGTTTACCG-3' | |

| Lat1 | F | 5'-GGGAAGGACATGGGACAAGG-3' |

| R | 5'-GCCAACACAATGTTCCCCAC-3' | |

| Cd36 | F | 5'-TGAATGGTTGAGACCCCGTG-3' |

| R | 5'-TAGAACAGCTTGCTTGCCCA-3' | |

| Lpl | F | 5'-GAAAGGGCTCTGCCTGAGTT-3' |

| R | 5'-TAGGGCATCTGAGAGCGAGT-3' | |

| Vegfa | F | 5'-TGGACCCTGGCTTTACTGCT-3' |

| R | 5'-GCAGTAGCTTCGCTGGTAGA-3' | |

| Vegfr1 | F | 5'-TGTGCACATGACGGAAGGAA-3' |

| R | 5'-GTATTGGTCTGCCGATGGGT-3' | |

| Ccn1 | F | 5'-AGAGGCTTCCTGTCTTTGGC-3' |

| R | 5'-CCAAGACGTGGTCTGAACGA-3' | |

| mtNd1 | F | 5'-CACTATTCGGAGCTTTACG-3' |

| R | 5'-TGTTTCTGCTAGGGTTGA-3' | |

| 18S | F | 5'-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3' |

| R | 5'-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3' |

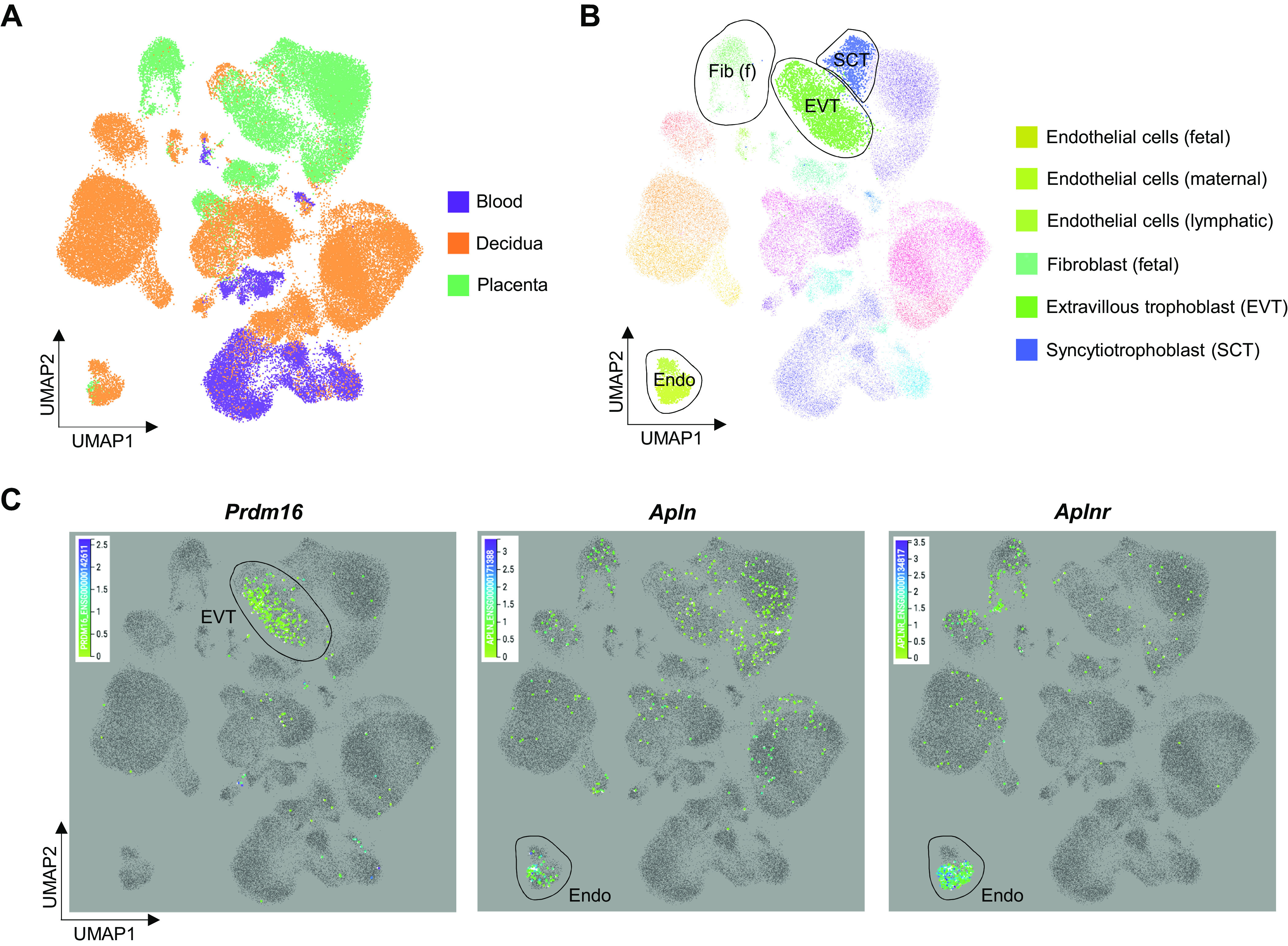

For single-cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing analysis of Prdm16, Apln, and Aplnr gene expression, we utilized publicly available data in “Maternal-Fetal Interface model” (https://maternal-fetal-interface.cellgeni.sanger.ac.uk), as previously reported (35). Using the interface model of the website, we selected cell types, including endothelial cells (fetal, maternal, and lymphatic), fibroblast (fetal), extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs), and syncytiotrophoblasts, and locations, including blood, decidua, and placenta. Then, selected genes (Prdm16, Apln, and Aplnr) were observed in specific cell types and locations listed earlier, which were presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis in human placenta. Previously referenced public data were utilized and its programmed model for maternal and fetal interface was used (35). A: cell clusters of different tissues (blood, decidua, and placenta) of maternal-fetal interface. B: highlighted cell types related to the genes (Prdm16, Apln, and Aplnr). C: Prdm16, Apln, and Aplnr expressed in specific target cells.

Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number

Total DNA was extracted using DNA extraction lysis buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, 0.5 M EDTA, 5 M NaCl, and 10% SDS) and proteinase K (No. 25530-015, Invitrogen). The extracted DNA was used for measuring mitochondrial DNA copy numbers using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and expressed as the ratio of mitochondrial DNA copy number (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1; Nd1) to the genomic DNA (lipoprotein lipase; Lpl; 36). The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Immunoblotting Analysis

Lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCL, pH 6.8, 2.0% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4) was used to extract proteins from the homogenized placenta, and the protein concentration of lysates was determined using the Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad). Twenty microgram of total proteins were loaded in each well. Antibodies against PRDM16 (No. PA5-20872; dilution 1:1,000) and CD31 (No. PA5-24411; dilution 1:1,000) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). PGC-1α (No. 66369-1-IG; dilution 1:1,000; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (No. sc-7269; dilution 1:500; Dallas, TX). An antibody against β-tubulin was further obtained (No. E7; dilution 1:200; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). For secondary antibodies, IRDye 680 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000) and IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000) were purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). Selected proteins were detected by the infrared imaging system (Odyssey, LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified (Image Studio Lite, LI-COR Biosciences; 14).

Histological Analysis

At E18.5, randomly selected fresh placenta samples were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h at room temperature and, then, paraffin embedded (14). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunocytochemical (ICC) staining were performed using the cross section of the center of each sample (5-µm-thick). For H&E staining, the size of junctional and labyrinth zones was measured using ImageJ software (ver. 1.52a, National Institutes of Health). For ICC staining, an endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) primary antibody (No. sc-136977; dilution 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat anti-mouse IgG2b Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (No. A-21141; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. Images for H&E (EVOS XL Core Imaging System; Mill Creek, WA) and ICC (EVOS FL Color Imaging System; Mill Creek) were obtained. Vessel density was determined by examining four randomly selected slides per sample and the number of vessels in the labyrinth zone was counted, and the average of each sample was used for data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The GraphPad Prism 7 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for making figures. The statistical analysis software (SPSS Statistics version 21, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was utilized for analyzing data. Statistical power for sample size was determined based on our previous studies (n = 6; 80% power, α = 0.05). One way ANOVA analyses were used, which were followed by post hoc analysis (Tukey’s test). Pearson correlations were further used. Results were showed as means ± SE, and statistical differences were shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for CON versus OB or CD/PBS versus OB/PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 for OB versus OB/Ex or OB/PBS versus OB/APN; $P < 0.05, $$P < 0.01, and $$$P < 0.001 for CON versus OB/Ex or CD/PBS versus OB/APN.

RESULTS

Prdm16, Apln, and Aplnr Expression in Placenta

Based on single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), Prdm16 was mostly expressed in extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs) and syncytiotrophoblasts (SCTs; Fig. 2, A–C), which are responsible for nutrient and gas exchanges between the mother and her fetus (3). On the other hand, Apln and Aplnr were widely expressed, especially in endothelial cells in both maternal and fetal sides of placenta, as well as EVTs, SCTs, and fetal fibroblasts (Fig. 2, A–C).

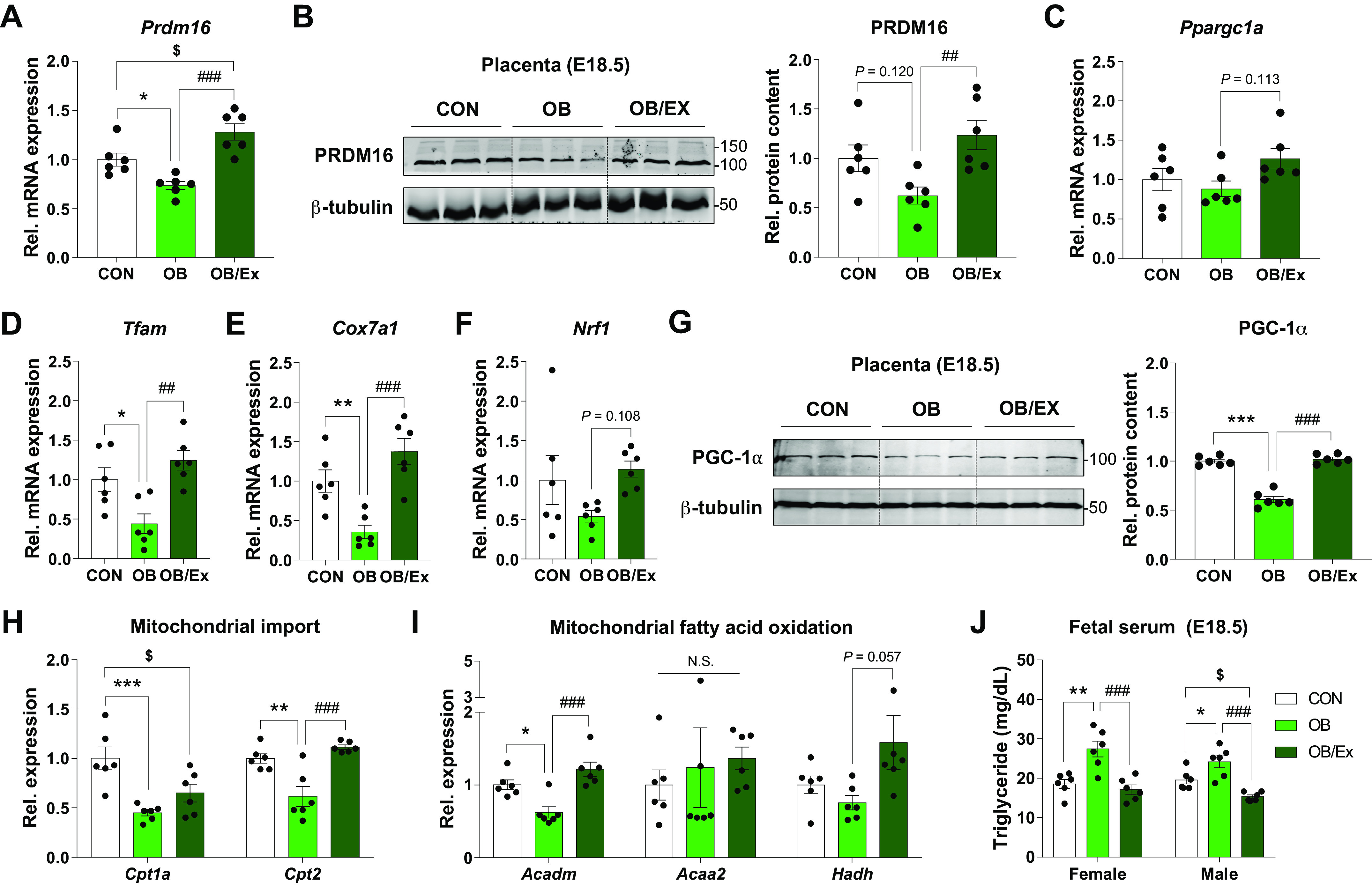

Exercise Enhances the Expression of PRDM16 and Oxidative Metabolic Markers in the Placenta

Recently, it was reported that PRDM16, a transcription factor partnering with PGC-1α, regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation (24). The level of PRDM16 was decreased in OB, but its level was elevated in response to maternal exercise in the OB/Ex group (Fig. 3, A and B), concomitant with normalized expression of placental fatty acid oxidation-related genes (Fig. 3, H and I). The mRNA expression of biomarkers related to mitochondrial biogenesis and the protein level of PGC-1α were suppressed in OB group but recovered in the OB/Ex group (Fig. 3, C–G), showing beneficial effects of ME during pregnancy in improving placental oxidative metabolism. Consistently, the triglyceride level in fetal serum was higher in OB, which was prevented by maternal exercise (Fig. 3J). Taken together, our data showed that ME elevates the expression of PRDM16 and oxidative metabolic markers of placenta, which were downregulated due to maternal obesity (MO).

Figure 3.

Exercise during pregnancy enhances placental PRDM16 expression and oxidative capacity. mRNA expression (A) and cropped images and means of protein levels (B) of PRDM16 in E18.5 placenta. C–F: expression of genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis in E18.5 placenta. G: cropped Western blot images and quantification of PGC-1α in the placenta at E18.5 (β-tubulin was used for normalization). Relative expression of mitochondrial import (H) and fatty acid oxidation (I)-related genes in the placenta at E18.5. J: triglyceride content in fetal serum. Data are shown as the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS; ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 in OB vs. OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN; $P < 0.05 in CON vs. OB/Ex or CD/PBS vs. OB/APN by one way ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Tukey’s test; A–J). APN, apelin; CD, control diet; CON, control; OB, obesogenic diet; OB/Ex, OB with exercise; PRDM16, PR domain 16.

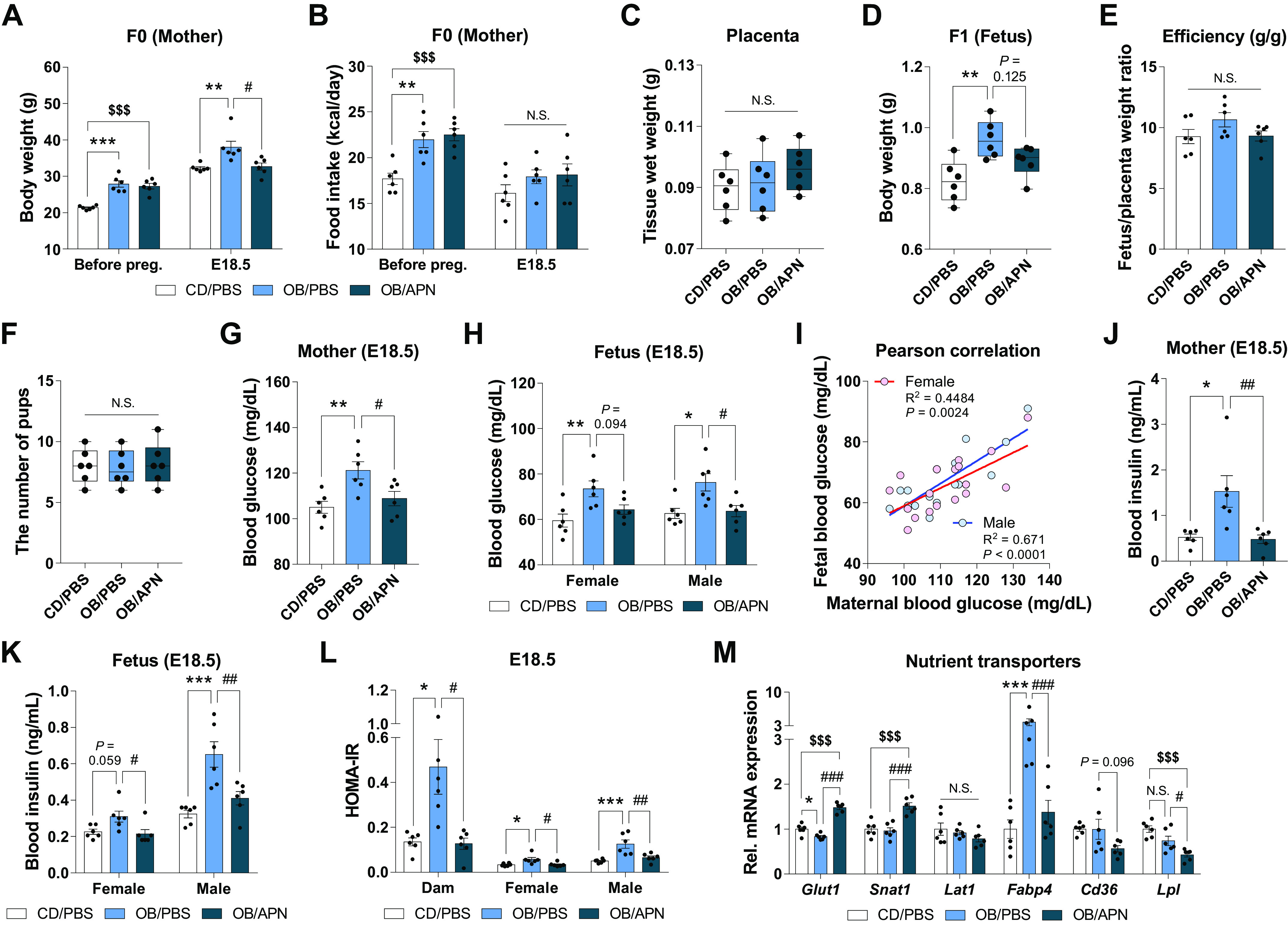

Apelin Regulates Expression of Nutrient Transporters in Placenta

To explore whether apelin supplementation mirrors the beneficial effects of exercise on glucose metabolism and placental function, we administered apelin or PBS daily during pregnancy to MO mice. The body weights were increased in OB/PBS group, but OB/APN group showed less weight gain (vs. OB/PBS; Fig. 4A) despite no changes in energy intake versus OB/PBS group (Fig. 4B). Although no significant changes in placental weights and efficiency were found, fetal body weights were increased in OB/PBS compared with CD/PBS group (Fig. 4, C–E), consistent with changes in maternal body weights (Fig. 4A). No differences in litter sizes were observed among treatments (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Apelin supplementation during pregnancy improves both maternal and fetal physiological parameters, and nutrient transporter expression in placenta. Maternal body weight (A) and energy intake (B) before pregnancy and during pregnancy at E18.5. Weight of placenta (C) and fetus (D) at E18.5. Placental efficiency (E) and the number of fetus (F) at E18.5. Serum glucose levels of mother (G) and fetus (H) at E18.5. I: Pearson correlation of blood glucose levels between mothers and fetuses (E18.5) of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN. Serum insulin levels of mothers (J) and fetuses (K) at E18.5. L: insulin resistance of mothers and fetuses at E18.5. M: relative gene expression of nutrient transporters in the placenta at E18.5. Data are shown as the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P< 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in OB vs. OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN; $$$P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB/Ex or CD/PBS vs. OB/APN by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (A–M) or Pearson correlation (I). APN, apelin; CD, control diet; CON, control; OB, obesogenic diet; OB/Ex, OB with exercise.

In the bio-parameters of glucose metabolism, OB/PBS mice showed elevated serum glucose levels in both mothers and fetuses (vs. CD/PBS), which were suppressed by apelin (vs. OB/PBS) (Fig. 4, G and H), consistent with improved insulin sensitivity (Fig. 4, J and L). These data suggested a close correlation between maternal and fetal glucose levels in serum (Fig. 4I). Besides, apelin administration upregulated the expression of nutrient transporters, including glucose transporter (Glut1) and amino acid transporter (Snat1); however, fatty acid transporters (Fabp4, Cd36, and Lpl) were downregulated in OB/APN (vs. OB/PBS; Fig. 4M). In short, apelin administration not only enhances the expression of glucose and amino acid transporters but also restores the elevated fatty acid transporters, consistent with the reduction in fetal body weight.

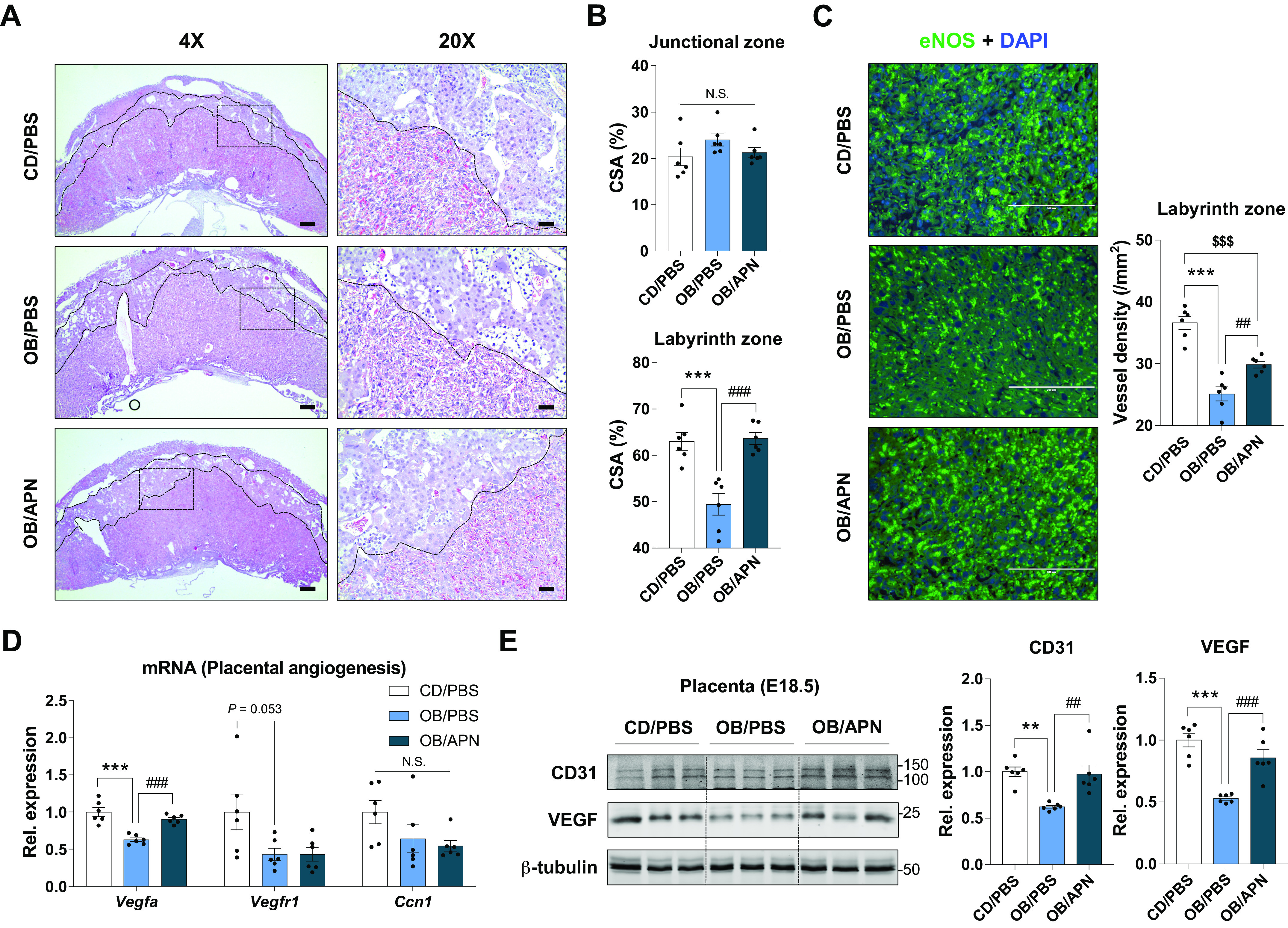

Apelin Administration Mimics the Benefits of Maternal Exercise in Improving Placental Vascularization

Although there were no significant changes in the size of junctional zone among CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN groups, the size of labyrinth zone was substantially decreased in OB/PBS (vs. CD/PBS) but recovered in OB/APN group (vs. OB/PBS; Fig. 5, A and B). Consistently, the density of vessel was also reduced in OB/PBS compared with CD/PBS, but OB/APN showed elevated density compared with OB/PBS (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the gene expression and protein contents of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were downregulated in OB/PBS compared with CD/PBS, but prevented in OB/APN group (Fig. 5, D and E), showing that apelin enhances placental vascularization impaired due to maternal obesity.

Figure 5.

Apelin supplementation during pregnancy enhances placental vascularization. Representative images of H&E (A), and the percentage of cross-sectional areas of junctional zone or labyrinth zone (B) in the placenta at E18.5 (×4, scale bar = 500 µm; ×20, scale bar = 100 µm). C: representative images of immunocytochemical staining of eNOS and mean vessel density in the labyrinth areas of placenta at E18.5 (scale bar = 200 µm). D: relative expression of angiogenic genes in the placenta at E18.5. E: cropped Western blot images and means of CD31 and VEGF in E18.5 placenta (β-tubulin was used for normalization). Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 6). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS; ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 in OB vs. OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN; $$$P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB/Ex or CD/PBS vs. OB/APN by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (A–E). APN, apelin; CD, control diet; CON, control; CSA, cross-sectional area; OB, obesogenic diet; OB/Ex, OB with exercise; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

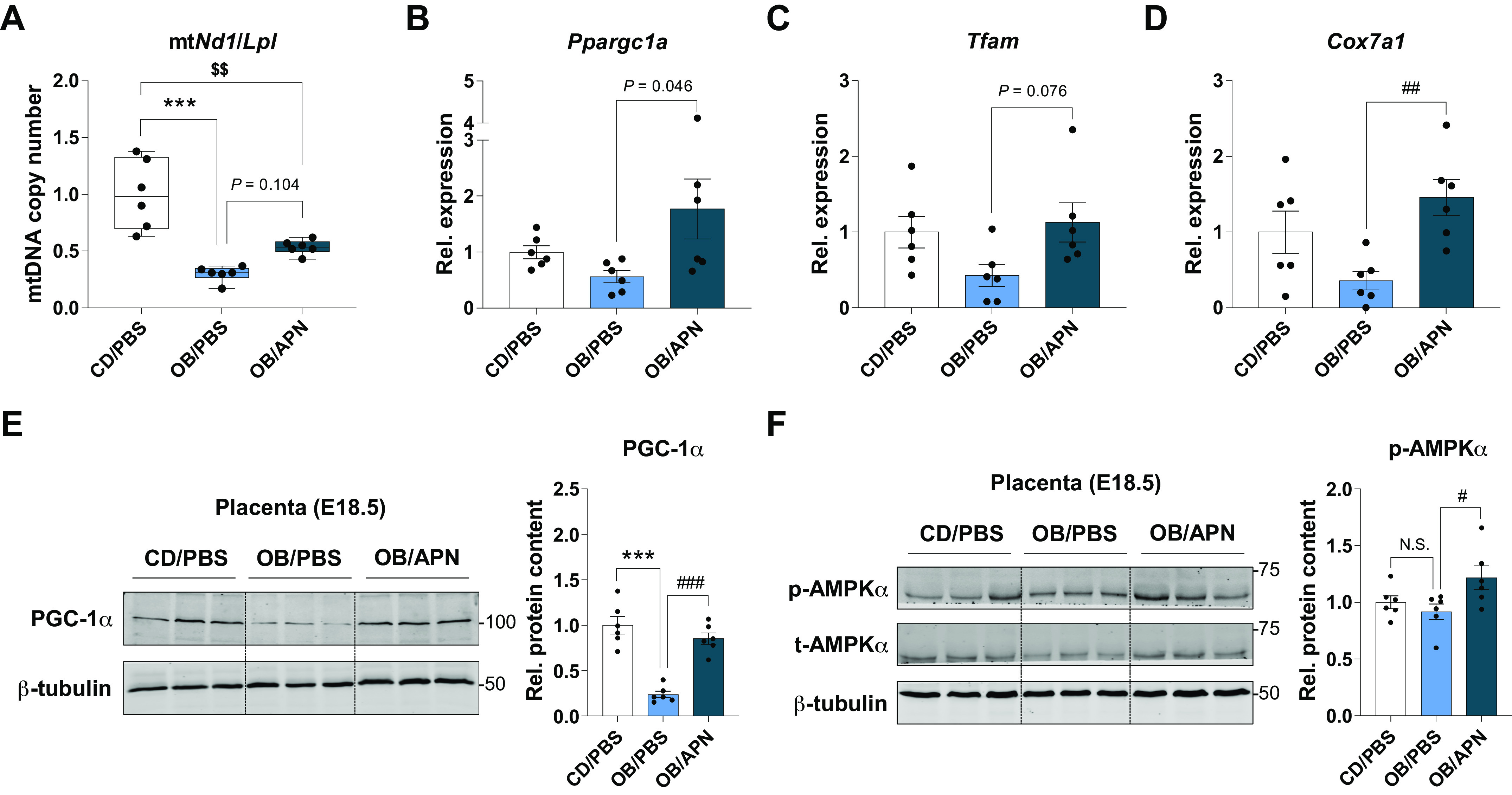

Apelin Administration Activates Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Oxidative Metabolism in Placenta

One of the major effects of exercise is to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis (37), which oxidizes substrates for energy generation in the placenta (38). Expectedly, mitochondrial DNA copy number was downregulated due to maternal obesity (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, mitochondrial marker genes, including Ppargc1a, Tfam, and Cox7a1, were upregulated in response to apelin administration (Fig. 6, B–D). Consistently, the protein level of PGC-1α, a coactivator of mitochondrial biogenesis, was also elevated by apelin injection (Fig. 6E). Consistently, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a downstream effector of APJ signaling, was further activated by apelin administration (Fig. 6F), which is known to activate PGC-1α (39, 40).

Figure 6.

Apelin administration induces mitochondrial biogenesis in the placenta. A: mitochondrial copy number in E18.5 placenta. B–D: relative expression of mitochondrial biogenesis-related genes in the placenta at E18.5. E: cropped Western blot images of PGC-1α in E18.5 placenta (β-tubulin was used for normalization). Data are shown as the means ± SE (n = 6). ***P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in OB vs. OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN; $$P < 0.01 in CON vs. OB/Ex or CD/PBS vs. OB/APN by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (A–F). AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; APN, apelin; CD, control diet; CON, control; OB, obesogenic diet; OB/Ex, OB with exercise; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α.

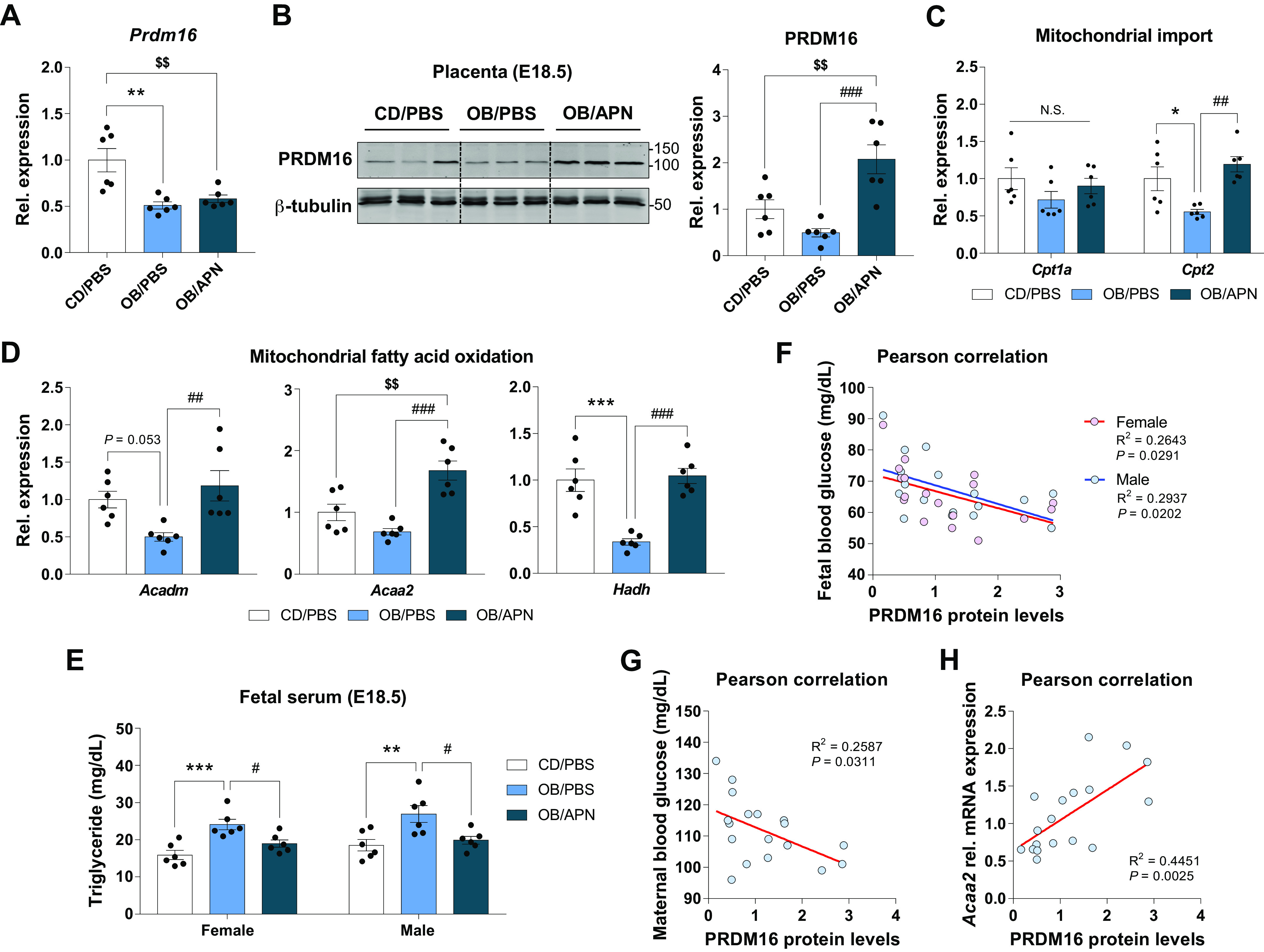

PRDM16 regulates oxidative metabolism (24). We further found that the significant reduction of Prdm16 mRNA expression and its protein levels was observed in OB/PBS group versus CD/PBS, which was elevated in the OB/APN group (Fig. 6, A and B). Similar changes were also observed in the expression of Cpt1a and Cpt2 (Fig. 7C), which transfer fatty acids into the mitochondria (41). Consistently, genes regulating mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation were reduced due to maternal obesity but prevented by exercise (Fig. 7D), negatively correlated with changes in triglyceride contents in fetal serum (Fig. 7E). Based on Pearson correlation analysis, PRDM16 expression was negatively correlated with the blood glucose levels of mothers and their fetuses (Fig. 7, F and G), and positively associated with the expression of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative gene, Acaa2 (Fig. 7H). Taken together, apelin administration enhances placental mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism impaired due to MO.

Figure 7.

Apelin administration protects the impairment of PRDM16 and oxidative metabolism in the placenta. Relative gene expression (A) and cropped Western blot images and quantification (B) of PRDM16 in the placenta at E18.5. Relative expression of mitochondrial import (C) and fatty acid oxidation (D)-related genes in the placenta at E18.5. E: fetal serum triglyceride content. F–H: Pearson correlations among PRDM16 levels, blood glucose of mothers and fetuses, and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative genes in the placenta (E18.5) of CD/PBS, OB/PBS, and OB/APN. Data are shown as the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in CON vs. OB or CD/PBS vs. OB/PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 in OB vs. OB/Ex or OB/PBS vs. OB/APN; $$P < 0.01 in CON vs. OB/Ex or CD/PBS vs. OB/APN by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (A–E) or Pearson correlations (F–H). APN, apelin; CD, control diet; CON, control; OB, obesogenic diet; OB/Ex, OB with exercise; PRDM16, PR domain 16.

DISCUSSION

We show that maternal exercise during pregnancy improves oxidative metabolism, vascularization, and the expression of nutrient transporters of obese dams, and these beneficial effects can be mimicked by apelin administration. These data suggest that APJ signaling is a potential therapeutic target for improving placental and fetal development impaired due to maternal obesity. Considering the commonness of maternal obesity and the increasing prevalence of maternal sedentary lifestyle, these discoveries are clinically important to improve placental and fetal development of obese and inactive mothers, generating long-term beneficial effects on offspring metabolic health.

Maternal obesity is not only strongly linked to gestational complications but also programs long-term metabolic dysfunction in offspring such as the incidences of microbial dysbiosis and steatosis in animal models (42–44). Offspring mice born to obese mothers have a high risk of neonatal obesity, which maintains even after shifting to a healthy diet after weaning (45–48). Placenta mediates fetal programming and its malfunction due to maternal obesity affects fetal development (7). Despite exercise is effective in preventing diet-induced obesity in adults, little is known about the impacts of exercise during pregnancy on placental development.

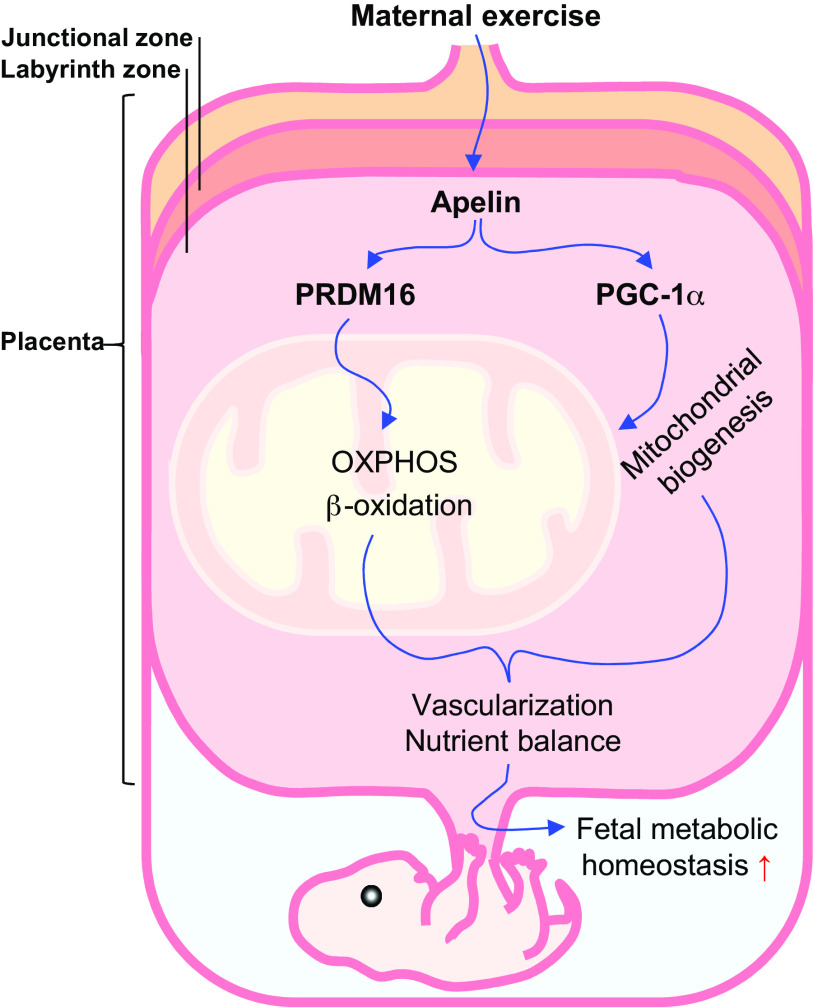

Placenta mediates maternal and fetal nutrient and oxygen exchange and also functions as an endocrine organ; these biological processes require energy, which is met by extensive oxidative metabolism in placenta (7). Both animal and human studies showed that maternal obesity during pregnancy suppresses oxidative metabolism but enhances oxidative stress in the placenta (49, 50). However, maternal exercise reduces oxidative stress and improves eNOS activity (51), which improves fetal cardiovascular system development (52). Placental vascular system is critical for oxygen and nutrient delivery to the fetus (53). The junctional zone is the endocrine component of placenta, whereas the labyrinth zone mediates the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and others (54). In our previous study, we found that maternal exercise improved placental vascularization and nutrient transporter expression in obese mice, associated with enhanced eNOS activity (5). Consistent with the benefits of maternal exercise, the present study further showed that maternal exercise promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative capacity of placenta, which is associated with PRDM16 activation (24). In partnership with PGC-1α, PRDM16 promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in intestine (24). Excitingly, based on scRNA-seq (35), Prdm16 is predominantly expressed in EVTs and SCTs, suggesting that PRDM16 may directly regulate mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in trophoblasts, which affect nutrient transport and its endocrine function (55). Consistently, we found that PRDM16 activation and mitochondrial oxidative function were enhanced by maternal exercise. In addition, both Ppargc1a mRNA expression and PGC-1α protein level were downregulated in the OB group but elevated in OB/Ex group, suggesting the protective effect of maternal exercise against adverse changes in placenta of obese mothers. Furthermore, we found that apelin administration increased mitochondrial DNA copy number and the expression of mitochondrial markers, including Tfam and Cox7a1, which were reduced due to maternal obesity. The expression of Cpt1a and Cpt2, which mediate the rate-limiting transport of fatty acid acyl-CoA into mitochondria for β-oxidation, was enhanced by maternal exercise, suggesting increased placental oxidation of lipids. Consistently, the lipid concentration in the fetal circulation was reduced due to maternal exercise and apelin administration. The enhanced oxidation by the placenta might also partially explain the reduction of glucose and lipid levels in the fetus due to maternal exercise and apelin administration, which improves fetal development (5). In summary, maternal exercise stimulates APJ signaling, which activates PRDM16 expression and oxidative metabolism in placenta, improving fetal development (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Graphic view of mechanisms linking maternal exercise and apelin administration to enhanced oxidative function and vascularization of placenta. PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α; PRDM16, PR domain 16.

Effective nutrient transportation requires the presence of nutrient transporters. The present study showed that maternal obesity suppresses the expression of glucose and amino acid transporters, including Glut1 and Snat1, which were reversed by apelin supplementation. Insufficient placental expression and activity of glucose transporter (GLUT) and amino acid transporter such as Snat1 and Lat1, are associated with deterioration in fetal development (56–58). On the other hand, we observed that maternal and fetal blood glucose levels were elevated due to MO, which is might be due to impaired glucose uptake by the fetal liver and muscle (59, 60). Effective nutrient and oxygen transportation require the presence of an extensive vascular system (53). Consistently, we showed that a notable decrease of labyrinth zone and vessel density was observed in OB/PBS group but alleviated by maternal exercise (5). Importantly, we found that apelin administration mimicked the effects of maternal exercise in improving vasculature of placenta impaired due to obesity. In support of the roles of APJ in improving vascular system development, scRNA-seq analysis showed that Apln and Aplnr abundantly express in endothelial cells of the placenta and decidua (35), as well as fetal fibroblasts which are multipotent progenitor cells (61, 62). Thus, maternal exercise may stimulate apelin secretion and APJ signaling to enhance vasculogenesis in the placenta. Taken together, these data show that maternal exercise and apelin administration not only enhance the expression of nutrient transporters in placenta, but also improve its vasculature system in placenta of obese mothers.

In our previous study, we found that exercise during pregnancy potently stimulates apelin expression in the placenta (5, 13). Of note, ME stimulated apelin expression in placental labyrinth zone, where exchange of nutrients between maternal and fetal blood occurs (13). Furthermore, ME and/or apelin administration elevated apelin serum levels in mothers and their fetuses, demonstrating that ME may stimulate APJ signaling in the placental vascular system to improve placental function (13), consistent with a recent study (63). Thus, we suggest that apelin might be secreted from placenta, which can be released into the fetal circulation. In addition, apelin in maternal circulation might cross placenta into the fetal circulation, consistent with the permeability of endothelial cells to apelin (11).

The present study focuses on analyzing the effects of maternal exercise and apelin administration during pregnancy on the gene expression of placental oxidative metabolism, vascular system, and nutrient transportation. However, gene expression and protein levels do not always align with functional readouts (64). Thus, the lack of direct functional measurement is a deficiency of the current study. Also, due to the small sizes of mouse placenta and no difference observed between female and male placentas in previous studies (5, 63), we did not separate placenta based on sexes and considered each pregnancy as an experimental unit. Besides, we initially expected that the decrease in placental nutrient transporter expression, vascularization, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and size of the labyrinth zone would reduce the fetal weight. However, in the current study, we found that obesity-induced placental insufficiency was associated with increased fetal body weight, which could be due to the upregulation of fatty acid transporters in the placenta of obese dams, as well as elevated fetal insulin and glucose levels, leading to fetal macrosomia (65). Of note, in our previous studies, we robustly found that 45% HFD during pregnancy increased neonatal weight, whereas 60% HFD reduced, which might be due to the extremely high fat of the 60% HFD resulting in a reduction of feed intake and deficiency of other nutrients. Consistently, systemic meta-analysis showed the association between MO and fetal macrosomia (66).

Besides apelin, recent studies identified other placenta-derived hormones including apelin, superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3), adiponectin, and irisin (19). Briefly, SOD3 was recently highlighted as an exercise-induced mediator secreted from placental trophoblasts in regulating fetal hepatic glucose metabolism (63). Adiponectin and irisin, which are known as exercise-regulated hormones (67, 68), are also expressed in the placenta, which facilitate fetal growth and glucose metabolism (69–71).

In summary, our finding (Fig. 8) suggests that ME-stimulated apelin not only stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis but also oxidative metabolism, which facilitates placental vascularization and nutrient transporter expression. Considering that exercise is highly accessible and the commonness of placental dysfunction, our discovery on the importance of ME and apelin in mediating placental function has important clinical implications. Obesity in pregnancy impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the placenta, which is protectively enhanced by ME. Exogenous apelin administration, partially mimicking the beneficial effects of exercise in improving placental mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism may represent a therapeutic approach to overcome placental dysfunction and fetal abnormal growth due to MO.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01-HD067449).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.A.C., J.S.S., M.-J.Z., and M.D. conceived and designed research; S.A.C., J.S.S., L.Z., Y.G., X.L., and J.M.d. performed experiments; S.A.C., J.S.S., and M.D. analyzed data; S.A.C., J.S.S., M.-J.Z., and M.D. interpreted results of experiments; S.A.C. prepared figures; S.A.C. drafted manuscript; S.A.C. and M.D. edited and revised manuscript; S.A.C., J.S.S., L.Z., Y.G., X.L., J.M.d., M.-J.Z., and M.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 392. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowe WL Jr, Bain JR, Nodzenski M, Reisetter AC, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Newgard CB, Scholtens DM; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Maternal BMI and glycemia impact the fetal metabolome. Diabetes Care 40: 902–910, 2017. [Erratum in Diabetes Care 41: 640, 2018] . doi: 10.2337/dc16-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napso T, Yong HEJ, Lopez-Tello J, Sferruzzi-Perri AN. The role of placental hormones in mediating maternal adaptations to support pregnancy and lactation. Front Physiol 9: 1091, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart TJ, O'Neill K, Condon D, Sasson I, Sen P, Xia Y, Simmons RA. Diet-induced obesity alters the maternal metabolome and early placenta transcriptome and decreases placenta vascularity in the mouse. Biol Reprod 98: 795–809, 2018. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son JS, Liu X, Tian Q, Zhao L, Chen Y, Hu Y, Chae SA, de Avila JM, Zhu MJ, Du M. Exercise prevents the adverse effects of maternal obesity on placental vascularization and fetal growth. J Physiol 597: 3333–3347, 2019. doi: 10.1113/JP277698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hebert JF, Myatt L. Placental mitochondrial dysfunction with metabolic diseases: therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1867: 165967, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malti N, Merzouk H, Merzouk SA, Loukidi B, Karaouzene N, Malti A, Narce M. Oxidative stress and maternal obesity: feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta 35: 411–416, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He N, van Iperen L, de Jong D, Szuhai K, Helmerhorst FM, van der Westerlaken LA, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM. Human extravillous trophoblasts penetrate decidual veins and lymphatics before remodeling spiral arteries during early pregnancy. PloS One 12: e0169849, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolahi KS, Valent AM, Thornburg KL. Cytotrophoblast, not syncytiotrophoblast, dominates glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation in human term placenta. Sci Rep 7: 42941, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep42941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aye ILMH, Aiken CE, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS. Placental energy metabolism in health and disease-significance of development and implications for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 226: S928–S944, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangwiro YTM, Cuffe JSM, Briffa JF, Mahizir D, Anevska K, Jefferies AJ, Hosseini S, Romano T, Moritz KM, Wlodek ME. Maternal exercise in rats upregulates the placental insulin-like growth factor system with diet- and sex-specific responses: minimal effects in mothers born growth restricted. J Physiol 596: 5947–5964, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP275758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangwiro YTM, Cuffe JSM, Mahizir D, Anevska K, Gravina S, Romano T, Moritz KM, Briffa JF, Wlodek ME. Exercise initiated during pregnancy in rats born growth restricted alters placental mTOR and nutrient transporter expression. J Physiol 597: 1905–1918, 2019. doi: 10.1113/JP277227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Son JS, Zhao L, Chen Y, Chen K, Chae SA, de Avila JM, Wang H, Zhu M-J, Jiang Z, Du M. Maternal exercise via exerkine apelin enhances brown adipogenesis and prevents metabolic dysfunction in offspring mice. Sci Adv 6: eaaz0359, 2020. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Son JS, Chae SA, Wang H, Chen Y, Bravo Iniguez A, de Avila JM, Jiang Z, Zhu MJ, Du M. Maternal inactivity programs skeletal muscle dysfunction in offspring mice by attenuating apelin signaling and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Rep 33: 108461, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanford KI, Takahashi H, So K, Alves-Wagner AB, Prince NB, Lehnig AC, Getchell KM, Lee MY, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Maternal exercise improves glucose tolerance in female offspring. Diabetes 66: 2124–2136, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db17-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanford KI, Lee MY, Getchell KM, So K, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Exercise before and during pregnancy prevents the deleterious effects of maternal high-fat feeding on metabolic health of male offspring. Diabetes 64: 427–433, 2015. doi: 10.2337/db13-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laker RC, Lillard TS, Okutsu M, Zhang M, Hoehn KL, Connelly JJ, Yan Z. Exercise prevents maternal high-fat diet-induced hypermethylation of the Pgc-1α gene and age-dependent metabolic dysfunction in the offspring. Diabetes 63: 1605–1611, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Besse-Patin A, Montastier E, Vinel C, Castan-Laurell I, Louche K, Dray C, Daviaud D, Mir L, Marques MA, Thalamas C, Valet P, Langin D, Moro C, Viguerie N. Effect of endurance training on skeletal muscle myokine expression in obese men: identification of apelin as a novel myokine. Int J Obe (Lond) 38: 707–713, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chae SA, Son JS, Du M. Prenatal exercise in fetal development: a placental perspective. FEBS J, 2021. doi: 10.1111/febs.16173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatemoto K, Hosoya M, Habata Y, Fujii R, Kakegawa T, Zou MX, Kawamata Y, Fukusumi S, Hinuma S, Kitada C, Kurokawa T, Onda H, Fujino M. Isolation and characterization of a novel endogenous peptide ligand for the human APJ receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 251: 471–476, 1998. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Than A, He HL, Chua SH, Xu D, Sun L, Leow MK, Chen P. Apelin enhances brown adipogenesis and browning of white adipocytes. J Biol Chem 290: 14679–14691, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.643817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen P, Levy JD, Zhang Y, Frontini A, Kolodin DP, Svensson KJ, Lo JC, Zeng X, Ye L, Khandekar MJ, Wu J, Gunawardana SC, Banks AS, Camporez JP, Jurczak MJ, Kajimura S, Piston DW, Mathis D, Cinti S, Shulman GI, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell 156: 304–316, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scimè A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454: 961–967, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stine RR, Sakers AP, TeSlaa T, Kissig M, Stine ZE, Kwon CW, Cheng L, Lim HW, Kaestner KH, Rabinowitz JD, Seale P. PRDM16 maintains homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium by controlling region-specific metabolism. Cell Stem Cell 25: 830–845.e8, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinel C, Lukjanenko L, Batut A, Deleruyelle S, Pradère JP, Le Gonidec S, Dortignac A, Geoffre N, Pereira O, Karaz S, Lee U, Camus M, Chaoui K, Mouisel E, Bigot A, Mouly V, Vigneau M, Pagano AF, Chopard A, Pillard F, Guyonnet S, Cesari M, Burlet-Schiltz O, Pahor M, Feige JN, Vellas B, Valet P, Dray C. The exerkine apelin reverses age-associated sarcopenia. Nat Med 24: 1360–1371, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilkenny C, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: ARRIVE-ing at a solution. Lab Anim 44: 377–378, 2010. doi: 10.1258/la.2010.0010021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 8: e1000412, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chae SA, Son JS, Zhu M-J, de Avila JM, Du M. Treadmill running of mouse as a model for studying influence of maternal exercise on offspring. Bio Protoc 10: e3838, 2020. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou T, Chen D, Yang Q, Wang B, Zhu MJ, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Resveratrol supplementation of high-fat diet-fed pregnant mice promotes brown and beige adipocyte development and prevents obesity in male offspring. J Physiol 595: 1547–1562, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tunster SJ. Genetic sex determination of mice by simplex PCR. Biol Sex Differ 8: 31, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13293-017-0154-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roza NA, Possignolo LF, Palanch AC, Gontijo JA. Effect of long-term high-fat diet intake on peripheral insulin sensibility, blood pressure, and renal function in female rats. Food Nutr Res 60: 28536, 2016. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v60.28536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parks BW, Sallam T, Mehrabian M, Psychogios N, Hui ST, Norheim F, Castellani LW, Rau CD, Pan C, Phun J, Zhou Z, Yang WP, Neuhaus I, Gargalovic PS, Kirchgessner TG, Graham M, Lee R, Tontonoz P, Gerszten RE, Hevener AL, Lusis AJ. Genetic architecture of insulin resistance in the mouse. Cell Metab 21: 334–347, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Q, Liang X, Sun X, Zhang L, Fu X, Rogers CJ, Berim A, Zhang S, Wang S, Wang B, Foretz M, Viollet B, Gang DR, Rodgers BD, Zhu MJ, Du M. AMPK/α-ketoglutarate axis dynamically mediates DNA demethylation in the Prdm16 promoter and brown adipogenesis. Cell Metab 24: 542–554, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55: 611–622, 2009. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vento-Tormo R, Efremova M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, Park JE, Stephenson E, Polański K, Goncalves A, Gardner L, Holmqvist S, Henriksson J, Zou A, Sharkey AM, Millar B, Innes B, Wood L, Wilbrey-Clark A, Payne RP, Ivarsson MA, Lisgo S, Filby A, Rowitch DH, Bulmer JN, Wright GJ, Stubbington MJT, Haniffa M, Moffett A, Teichmann SA. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature 563: 347–353, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurya SK, Herrera JL, Sahoo SK, Reis FCG, Vega RB, Kelly DP, Periasamy M. Sarcolipin signaling promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle. Cell Rep 24: 2919–2931, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson MM, Dasari S, Konopka AR, Johnson ML, Manjunatha S, Esponda RR, Carter RE, Lanza IR, Nair KS. Enhanced protein translation underlies improved metabolic and physical adaptations to different exercise training modes in young and old humans. Cell Metab 25: 581–592, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu M, Sferruzzi-Perri AN. Placental mitochondrial function in response to gestational exposures. Placenta 104: 124–137, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalfalah F, Sobek S, Bornholz B, Götz-Rösch C, Tigges J, Fritsche E, Krutmann J, Köhrer K, Deenen R, Ohse S, Boerries M, Busch H, Boege F. Inadequate mito-biogenesis in primary dermal fibroblasts from old humans is associated with impairment of PGC1A-independent stimulation. Exp Gerontol 56: 59–68, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem 47: 69–84, 2010. doi: 10.1042/bse0470069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liepinsh E, Makrecka-Kuka M, Volska K, Kuka J, Makarova E, Antone U, Sevostjanovs E, Vilskersts R, Strods A, Tars K, Dambrova M. Long-chain acylcarnitines determine ischaemia/reperfusion-induced damage in heart mitochondria. Biochem J 473: 1191–1202, 2016. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCurdy CE, Bishop JM, Williams SM, Grayson BE, Smith MS, Friedman JE, Grove KL. Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 119: 323–335, 2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI32661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorn SR, Baquero KC, Newsom SA, El Kasmi KC, Bergman BC, Shulman GI, Grove KL, Friedman JE. Early life exposure to maternal insulin resistance has persistent effects on hepatic NAFLD in juvenile nonhuman primates. Diabetes 63: 2702–2713, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db14-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma J, Prince AL, Bader D, Hu M, Ganu R, Baquero K, Blundell P, Alan Harris R, Frias AE, Grove KL, Aagaard KM. High-fat maternal diet during pregnancy persistently alters the offspring microbiome in a primate model. Nat Commun 5: 1–11, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruce KD, Cagampang FR, Argenton M, Zhang J, Ethirajan PL, Burdge GC, Bateman AC, Clough GF, Poston L, Hanson MA, McConnell JM, Byrne CD. Maternal high‐fat feeding primes steatohepatitis in adult mice offspring, involving mitochondrial dysfunction and altered lipogenesis gene expression. Hepatology 50: 1796–1808, 2009. doi: 10.1002/hep.23205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mouralidarane A, Soeda J, Visconti-Pugmire C, Samuelsson A-M, Pombo J, Maragkoudaki X, Butt A, Saraswati R, Novelli M, Fusai G, Poston L, Taylor PD, Oben JA. Maternal obesity programs offspring nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by innate immune dysfunction in mice. Hepatology 58: 128–138, 2013. doi: 10.1002/hep.26248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oben JA, Mouralidarane A, Samuelsson A-M, Matthews PJ, Morgan ML, McKee C, Soeda J, Fernandez-Twinn DS, Martin-Gronert MS, Ozanne SE, Sigala B, Novelli M, Poston L, Taylor PD. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and lactation programs the development of offspring non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. J Hepatol 52: 913–920, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jonscher KR, Stewart MS, Alfonso-Garcia A, DeFelice BC, Wang XX, Luo Y, Levi M, Heerwagen MJR, Janssen RC, de la Houssaye BA, Wiitala E, Florey G, Jonscher RL, Potma EO, Fiehn O, Friedman JE. Early PQQ supplementation has persistent long‐term protective effects on developmental programming of hepatic lipotoxicity and inflammation in obese mice. FASEB J 31: 1434–1448, 2017. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600906R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallace JG, Bellissimo CJ, Yeo E, Fei Xia Y, Petrik JJ, Surette MG, Bowdish DME, Sloboda DM. Obesity during pregnancy results in maternal intestinal inflammation, placental hypoxia, and alters fetal glucose metabolism at mid-gestation. Sci Rep 9: 17621, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos-Rosendo C, Bugatto F, González-Domínguez A, Lechuga-Sancho AM, M MR, Visiedo F. Placental adaptive changes to protect function and decrease oxidative damage in metabolically healthy maternal obesity. Antioxidants (Basel) 9: 794, 2020. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saiyin T, Engineer A, Greco ER, Kim MY, Lu X, Jones DL, Feng Q. Maternal voluntary exercise mitigates oxidative stress and incidence of congenital heart defects in pre-gestational diabetes. J Cell Mol Med 23: 5553–5565, 2019. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engineer A, Saiyin T, Greco ER, Feng Q. Say NO to ROS: their roles in embryonic heart development and pathogenesis of congenital heart defects in maternal diabetes. Antioxidants (Basel) 8: 436, 2019. doi: 10.3390/antiox8100436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woods L, Perez-Garcia V, Hemberger M. Regulation of placental development and its impact on fetal growth-new insights from mouse models. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9: 570, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guttmacher AE, Maddox YT, Spong CY. The Human Placenta Project: placental structure, development, and function in real time. Placenta 35: 303–304, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aplin JD. Developmental cell biology of human villous trophoblast: current research problems. Int J Dev Biol 54: 323–329, 2010. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082759ja. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanirowski PJ, Lipa M, Bomba-Opoń D, Wielgoś M. Expression of placental glucose transporter proteins in pregnancies complicated by fetal growth disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 123: 95–131, 2021. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Gronigen Case G, Storey KM, Parmeley LE, Schulz LC. Effects of maternal nutrient restriction during the periconceptional period on placental development in the mouse. PloS One 16: e0244971, 2021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang C-X, Chen F, Zhang W-F, Zhang SH, Shi K, Song H-Q, Wang Y-J, Kim SW, Guan W-T. Leucine promotes the growth of fetal pigs by increasing protein synthesis through the mTOR signaling pathway in longissimus dorsi muscle at late gestation. J Agric Food Chem 66: 3840–3849, 2018. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campodonico-Burnett W, Hetrick B, Wesolowski SR, Schenk S, Takahashi DL, Dean TA, Sullivan EL, Kievit P, Gannon M, Aagaard K, Friedman JE, McCurdy CE. Maternal obesity and western-style diet impair fetal and juvenile offspring skeletal muscle insulin-stimulated glucose transport in nonhuman primates. Diabetes 69: 1389–1400, 2020. doi: 10.2337/db19-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falcão-Tebas F, Marin EC, Kuang J, Bishop DJ, McConell GK. Maternal exercise attenuates the lower skeletal muscle glucose uptake and insulin secretion caused by paternal obesity in female adult rat offspring. J Physiol 598: 4251–4270, 2020. doi: 10.1113/JP279582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Golos TG, Giakoumopoulos M, Gerami-Naini B. Review: trophoblast differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Placenta Suppl 34: S56–S61, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mali P, Ye Z, Hommond HH, Yu X, Lin J, Chen G, Zou J, Cheng L. Improved efficiency and pace of generating induced pluripotent stem cells from human adult and fetal fibroblasts. Stem Cells 26: 1998–2005, 2008. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kusuyama J, Alves-Wagner AB, Conlin RH, Makarewicz NS, Albertson BG, Prince NB, Kobayashi S, Kozuka C, Møller M, Bjerre M, Fuglsang J, Miele E, Middelbeek RJW, Xiudong Y, Xia Y, Garneau L, Bhattacharjee J, Aguer C, Patti ME, Hirshman MF, Jessen N, Hatta T, Ovesen PG, Adamo KB, Nozik-Grayck E, Goodyear LJ. Placental superoxide dismutase 3 mediates benefits of maternal exercise on offspring health. Cell Metab 33: 939–956.e8, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edfors F, Danielsson F, Hallström BM, Käll L, Lundberg E, Pontén F, Forsström B, Uhlén M. Gene-specific correlation of RNA and protein levels in human cells and tissues. Mol Syst Biol 12: 883, 2016. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salihu HM, Dongarwar D, King LM, Yusuf KK, Ibrahimi S, Salinas-Miranda AA. Trends in the incidence of fetal macrosomia and its phenotypes in the United States, 1971-2017. Arch Gynecol Obstet 301: 415–426, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaudet L, Ferraro ZM, Wen SW, Walker M. Maternal obesity and occurrence of fetal macrosomia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2014: 640291, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/640291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blüher M, Bullen JW Jr, Lee JH, Kralisch S, Fasshauer M, Klöting N, Niebauer J, Schön MR, Williams CJ, Mantzoros CS. Circulating adiponectin and expression of adiponectin receptors in human skeletal muscle: associations with metabolic parameters and insulin resistance and regulation by physical training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 2310–2316, 2006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Højlund K, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 481: 463–468, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aye IL, Rosario FJ, Powell TL, Jansson T. Adiponectin supplementation in pregnant mice prevents the adverse effects of maternal obesity on placental function and fetal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 12858–12863, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515484112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drewlo S, Johnson E, Kilburn BA, Kadam L, Armistead B, Kohan-Ghadr HR. Irisin induces trophoblast differentiation via AMPK activation in the human placenta. J Cell Physiol 235: 7146–7158, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salem H, Yatchenko Y, Anosov M, Rosenfeld T, Altarescu G, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Birk R. Maternal and neonatal irisin precursor gene FNDC5 polymorphism is associated with preterm birth. Gene 649: 58–62, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]