Abstract

Introduction

Youth (aged 10 to 24 years) comprise nearly one-third of Uganda’s population and often face challenges accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, with a disproportionately high incidence of negative SRH outcomes. Responding to COVID-19, Uganda implemented strict public health measures including broad public transportation, schooling, and business shut-downs, causing mass reverse-migration of youth from urban schools and workplaces back to rural home villages. Our study aimed to qualitatively describe the perceived unintended impacts of COVID-19 health measures on youth SRH in two rural districts.

Methods

Semi-structured focus group discussions (FGD) and key informant interviews (KII) with purposively selected youth, parents, community leaders, community health worker (CHW) coordinators and supervisors, health providers, facility and district health managers, and district health officers were conducted to explore lived experiences and impressions of the impacts of COVID-19 measures on youth SRH. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using deductive thematic analysis.

Results

Four COVID-19-related themes and three subthemes resulted from 15 FGDs and 2 KIIs (n=94). Public transportation shutdown and mandatory mask-wearing were barriers to youth SRH care-seeking. School/workplace closures and subsequent urban youth migration back to rural homes increased demand at ill-prepared, rural health facilities, further impeding care-seeking. Youth reported fear of discovery by parents, which deterred SRH service seeking. Lockdown led to family financial hardship, isolation, and overcrowding; youth mistreatment, gender-based violence, and forced marriage ensued with some youth reportedly entering partnerships as a means of escape. Idleness and increased social contact were perceived to lead to increased and earlier sexual activity. Reported SRH impacts included increased severity of infection and complications due to delayed care seeking, and surges in youth sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, and abortion.

Conclusion

COVID-19 public health measures reportedly reduced youth care seeking while increasing risky behaviours and negative SRH outcomes. Investment in youth SRH programming is critical to reverse unintended pandemic effects and regain momentum toward youth SRH targets. Future pandemic management must consider social and health disparities, and mitigate unintended risks of public health measures to youth SRH.

Keywords: Adolescent, COVID-19, Qualitative research, Reproductive health, Sexual health, Uganda

During the first wave of the pandemic, Uganda implemented nation-wide strict measures to manage coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Early in 2020, border screenings and preparation of a national prevention response plan were initiated (1,2). By mid-March, public gatherings were suspended, borders closed, and educational institutions shut down (3). With a few days' advance notice, all public transport (including common “boda boda” motorcycles) was suspended (4). By the end of March, a presidential directive led to a curfew, nonessential business closures, and mandatory mask-wearing (in all public spaces), and banned private vehicle travel, enforced by police, military, and local community officers (3,5). Government health facilities remained open for emergency and maternal health services; travel permission and assistance could be requested through local government officials (5). In May, some restrictions eased; select businesses could partially open and public transport in some regions was permitted to operate at half-capacity. By July, boda bodas could resume daytime operation (3). Curfews, gathering restrictions, and school closures remained in place until August 2020 (3). Overall, the lockdown caused an unprecedented reverse mass migration of an urban working/schooling population back to their family homes in rural communities (6).

During 2020, Sub-Saharan African (SSA) reported significantly lower COVID-19-related cases and mortality compared to other global regions, hypothesized due to a younger demographic, limited long-term care facilities, lack of testing, and prior human coronaviruses exposure (7,8). Uganda reported fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths during the first wave compared to similarly equipped SSA neighbours (2). By September 2020, Uganda reported 3500 cumulative COVID-19-related cases and 39 deaths (9).

Youth (10 to 24 years) comprise 32.4% of Uganda’s population (10). Before COVID-19, Ugandan youth faced challenges accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services with concerning SRH indicators; 20% of girls reported sexual activity before 15 years old; one-quarter of 15 to 19-year-old girls were pregnant or already mothers (10). Young females disproportionately experienced delivery complications, maternal death, risky abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and gender-based violence (GBV) (11). Health-wise, youth remain an underserved demographic; improving SRH health indicators remains a national priority.

Globally, evidence of the impact of COVID-19 on youth is critical, especially from low-income countries (3). An opportunity emerged to explore the health effects of COVID-19 on youth during a qualitative study to prepare for a Global Affairs Canada-funded intervention to answer the research question: “What were the lived experiences and impact of COVID-19 public health restrictions on youth SRH in rural Uganda from the perspective of youth, parents of youth, community leaders, and healthcare providers?”

METHODS

Our study was set in two rural Ugandan districts (Rubirizi, Bushenyi) with a combined population of ~360,000 according to the most recent census (2014, [12]). A larger, baseline study sought to understand the youth health context before the “Healthy Adolescents and Young People” (HAY!) initiative (2021-2024). HAY! targets youth SRH needs through community and facility-based capacity-building activities.

Baseline data collection (August 2020) coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic first wave in Uganda. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) and Key Informant Interview (KII) participants included youth (18 to 24 years old), mothers of youth, community leaders, Community Health Worker (CHWs) Coordinators, CHW supervisors, health providers, facility managers, district health managers, and district health officers. Using purposive sampling, known contacts from past initiatives (district health and facility managers) were approached who in-turn initiated snowball sampling of youth, parents, and clinical care providers. Table 1 shows characteristics and descriptions.

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics, category descriptions, and interview type

| Interview type | Participant category | Description | # Interviews conducted | # Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Group Discussion | Youth | An individual aged 18–24 years. | 3 | 21 (4M, 17F) |

| Mother | A mother to a child aged 10–24 years. | 1 | 8 (0M, 8 F) | |

| Community Leader | An elected village chairperson. | 1 | 8 (5M, 3F) | |

| Community Health Worker (CHW) Coordinator | CHWs are community-based volunteers with basic training conducting health promotion within their home village. One peer-elected CHW coordinator per CHW group (~8–20 CHWs) facilitates reporting, group activities, and meetings. | 2 | 16 (7M, 9F) | |

| CHW Supervisor | One clinical health provider from each government facility assigned to supervise a CHW group. | 2 | 13 (6M, 7F) | |

| Health Provider | A clinical health provider at a government health facility (i.e., nurse, clinical officer). | 1 | 6 (2M, 4F) | |

| Facility Manager | The designated clinician ‘in-charge’ for a government health facility. | 2 | 12 (6M, 6F) | |

| District Health Manager | One of a group of District Health Team members responsible for public health oversight in each district. | 2 | 8 (7M, 1 F) | |

| Key Informant Interview | District Health Officer | The most senior leader responsible for health in each district. | 2 | 3 (2M, 0F) |

| Total | 17 | 94 (39M, 55F) | ||

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to uncover youth health and SRH context in target districts. Questions were consistent across participant groups, all of whom were asked: “Based on your experiences, how has COVID-19 impacted the ability of youth in your community to seek SRH information and/or services and how has that affected their health?.” The English guide was translated into Runyankole (vernacular) and pilot-tested with respondent groups, including youth, in a neighbouring, non-study district, then minimally revised. Experienced male and female facilitators fluent in local language and context conducted FGDs and KIIs. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, then translated into English. In-person FGDs/KIIs accommodated COVID-19 restrictions through outdoor venues, spacing, small group size, and masking.

Data were organized using NVIVO software (13). Six analysts reviewed transcripts, coding COVID-19-relevant content using deductive thematic analysis. A priori themes paralleling country COVID-19 health restrictions were chosen based on the conceptual framework from the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) (14). This framework posits that governments bear primary responsibility for protecting health equity; broad public health restrictions implemented uniformly across all society sectors, without regard for health inequities in the young may cause unintended negative health consequences for vulnerable populations. Analysts reached a consensus on sub-themes and inter-relatedness through shared coding notes and in-person and virtual discussions.

RESULTS

Fifteen FGDs and 2 KIIs (n=94) were conducted. Table 1 summarizes participant sex and interview type. Data saturation was reached when no new sub-themes were identified in the final ~15% of transcripts analyzed.

Four main themes emerged related to COVID-19 impact on youth health. Table 2 shows themes and sub-themes which were highly consistent across all participant groups with no substantive difference in participant experiences between districts. The country-wide public transportation shutdown and an early and sudden mandatory mask-wearing requirement were identified as significant youth SRH service care-seeking barriers, especially for contraceptive usage. School/workplace closure and subsequent youth migration back to family homes resulted in a bulging youth population; this was reported to increase service and commodity demand (especially for youth-preferred contraceptives [i.e., condoms, implants, injectables]) at ill-prepared, small, rural health facilities, reducing the quality of care. Youth reported fearing discovery by parents while seeking SRH services locally (especially contraception and STI testing). Lockdown led to unemployment and subsequent family financial hardship, youth idleness, isolation, and household over-crowding. Lockdown disproportionately impacted females who reportedly faced increased mistreatment, abuse, and forced marriage; some married to escape family violence and forced manual labour at home. Idleness combined with a larger youth village population reportedly led to increased and earlier sexual activity.

Table 2.

Emerging themes, sub-themes, and representative quotations

| Theme 1: Public transportation shutdown. An early, country-wide public transport shutdown deterred youth SRH access, leading to decreased facility utilization of contraception, antenatal and delivery care services. | |

| Youth | “A youth will think of going to a clinic even if it is far, they need transport and there were no transport means during the COVID-19 and they cannot walk up to there, so they decide to stay with their challenges till COVID-19 ends...” |

| Theme 2: Mask mandate. Required face-covering discouraged youth care-seeking early in the pandemic due to limited availability and youth finances. Youth either chose not to visit health facilities or were turned away. | |

| Youth | “Yes, [COVID-19] has impacted our access and uptake of these services, because sometimes if you do not have a mask or even money to buy it, you cannot go to a health center for services because health workers will not treat you and you will stay with your disease, you can even die.” |

| Youth | “usually when [youth] reach the health facility and they do not have masks nor money to buy them, they are chased by health workers to go back home, and they have no option but to go back unattended” |

| Theme 3: School/workplace closure. A large proportion of youth working and schooling in urban centres returned to home villages, dramatically increasing youth populations. Youth-expressed fears of lost anonymity and confidentiality while care seeking at local facilities led to a significant decrease in SRH care-seeking compared with being at school, especially for contraception and STD testing. Increased youth pregnancy, abortions, and infections were reported outcomes. Attending local clinics during lockdown often necessitated parental awareness; youth feared reporting back to families in contrast to usual anonymous services available at schools/urban/away-from-home settings. | |

| Youth | “…we hear that many… have become pregnant because there are no measures. If you ask youths who have been using condoms before, they are no longer using them... It was easier for them while they were still at school because they would pretend that they are going to buy books and they end up buying condoms without anyone knowing, but now at home they say, “our neighbor is my mother’s friend, won’t he tell her that I bought condoms from him?” |

| Community Leader | “[Youth] are scared of meeting their parents or other relatives at these facilities, …they fear their parents finding out.” |

| Youth | When they go to the health facility, they will go to the same table as patients with other diseases, they will meet their neighbors and by the time [health workers] treat that youth, the neighbor will be aware of the disease she is suffering from...” |

| Health Worker | “We are having so many youths and adolescents in communities, and most of them like feel shy to come and access these services… for example you get a report that there is a girl here or a youth here, who had unsafe abortion and is failing to come to the facility.” |

| Subtheme 3a: Facilities ill-prepared/SRH commodity shortages. Demand for youth-oriented commodities (i.e., condoms, birth control pills) and youth service/consultation was lower before COVID-19. Due to a surge in youth population, unprepared and under equipped facilities posed a care- seeking barrier for youth. | |

| Health Provider | “… the reason why they are not coming to government facilities... Now if she comes today wanting [injectable contraceptive] and she finds it not there, she will not come tomorrow and she will tell her fellow[youth]…” |

| Youth | “…now, [during lockdown]… a girl might not ask him to look for condoms because they know that these condoms are hard to find.” |

| Health Worker | “…there are some commodities which you find we do not have, a youth will come telling you she wants family planning for one month and yet for us we have implants, you cannot put an implant in a lady who is 15 years old.” |

| Theme 4: Lockdown. Restricted travel and work reduced family incomes and resulted in crowded living conditions. Social and financial stressors and isolation increased youth risk (especially amongst females) of forced early marriage, gender-based violence, and family violence; seeking help was often not possible. | |

| Health Provider | “…there was a 13-year-old girl who was pregnant, and she had a complication… she told us that her paternal aunt was given 50 000 shillings [~15USD] and she gave her away for marriage.” |

| CHW Coordinator | “During this COVID-19 period, gender-based violence has greatly increased… in this season financial issues have increased, and it leads to violence between a wife, husband and children.” |

| Subtheme 4a: Youth mistreatment, family violence & GBV. Crowded living conditions and family financial insecurity led directly and indirectly to youth mistreatment. Some female youth fled homes to escape labor, domestic violence, and poverty, becoming ‘house girls’ elsewhere or partnering with same-age or older men. Often females ‘used’ for sexual activity and/or impregnated were subsequently abandoned. | |

| CHW Coordinator | “There is so much gender-based violence because you find that a 14-year-old girl is married to a 20-year-old man who tries to look for employment but things are a bit tough, if their child wants to drink milk, they cannot afford it...” |

| Youth | “There are some families that are always fighting, so girls make up their minds that ‘in case I find a man who can take me in, I will leave this violent family”. |

| Parent | “…due to COVID-19, gender-based violence has increased in families and it has affected children, to an extent that some children have left their homes and are now on streets.” |

| Subtheme 4b: Increased population of idle youth. An expanded population comprising newly ‘out-of-school’ and unemployed youths with more leisure time resulted in earlier and more youth sexual activity. Combined with limited contraception availability and decreased youth SRH care-seeking, teen pregnancies, and SRH complications reportedly increased. | |

| Community Leader | “[Teens] are all in villages lousing around, those who have been in segregated schools are now able to access their opposite gender and engage in sexual intercourse, most girls have become pregnant, others have gotten married before they are ready.” |

| Youth | “Most of [the 14- to 15-year-olds] have gotten married during this COVID-19 period, since they are in villages.” |

| CHW | “…most times they were in schools and now the population is increasing because they are in the villages doing nothing, that is why most of them are getting pregnant, most of them are aborting, because they are idle, have nothing to do.” |

| Parent | “COVID-19 has caused congestion of young people … and challenges have increased, 13 and 14 year girls are also getting pregnant and this is because adolescents have become many in the community and their interactions have also increased.” |

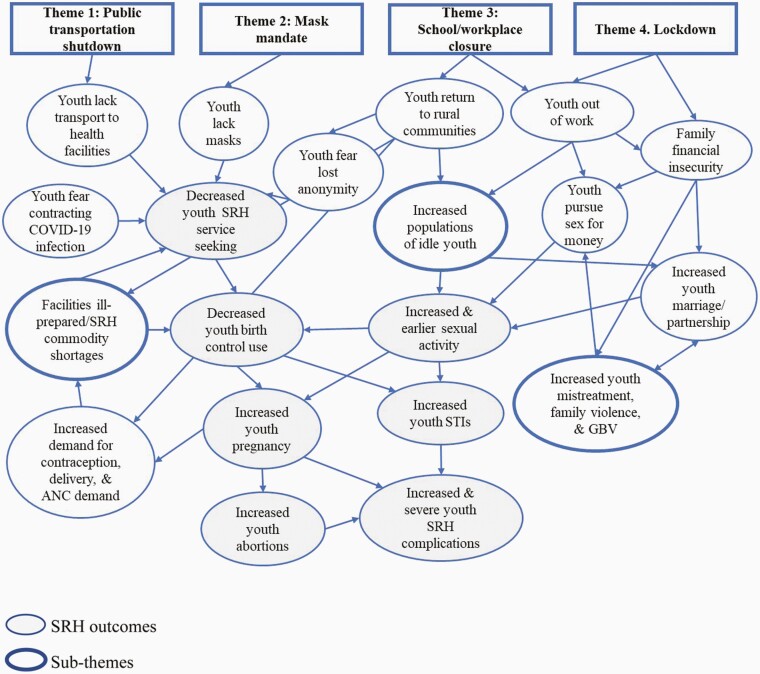

Reported health, family, economic, and social COVID-19 effects were highly inter-related and complex, as Figure 1 illustrates. Some positive COVID-19 impacts were mentioned (i.e., increased youth-parent interactions). However, generally, all participant groups expressed concerns about public health measures leading to negative SRH outcomes, having experienced and observed decreased SRH service access causing perceived surges in STIs, pregnancies, abortions, and more frequent and severe SRH complications. Participants perceived home financial insecurities causing youth mistreatment, family violence, and GBV, which were often attributed to increased youth marriage or partnerships, or vice versa, and youth using sex for money.

Figure 1.

Inter-relatedness of key themes, sub-themes, and key SRH outcomes.

DISCUSSION

While stringent public health measures were necessary for COVID-19 containment, our findings highlight concerning trends of unintended youth SRH consequences, potentially resulting from limited consideration of social inequities within national COVID-19 public health measures. A dramatic, unprecedented “reverse” youth migration from urban places of work/study back to rural villages caused unusual health facility, family, and youth stressors. Five months into the pandemic, reduced youth care-seeking, and health-risk behaviours were perceived to impact SRH outcomes, despite Uganda’s relatively low COVID-19 case burden.

Compared with older adults, youth generally experience lower COVID-19 severity (15). However, they disproportionately suffer from mental health, education disruption, and financial burdens (16–19). Our study fills an important gap in understanding the lived pandemic experiences of youth in a low-income setting. Although anecdotal experience and media widely speculate the unintended impacts of COVID-19 public health measures, low-income country publications are few.

The COVID-19 lockdown contributed to health service access challenges and heightened vulnerability due to social changes, income loss, and isolation, consistent with past epidemic trends and emerging pandemic literature. Ebola outbreak lockdowns in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo were associated with increased domestic violence, exploitation, sexual assault, transactional sex, and teenage pregnancy (20–22). Kenya experienced an increase in reported GBV cases linked to COVID-19 lockdowns (23,24). In Uganda, a study reported increased domestic violence due to public transport shutdown and health facility commodity shortages (3), while a health records review documented decreased care-seeking amongst pregnant females and increased adverse maternal and newborn outcomes (25). A “mask wearing requirement” is not a commonly reported barrier, however, a “public transportation shutdown” affected financially insecure rural youth disproportionately. Further quantitative studies corroborating participant experiences are warranted.

The reverse migration trend permeated and exaggerated emerging themes. Return by huge numbers of youth to tight-knit, rural communities led to youth concerns of confidentiality loss, commodity shortages, high demand, and longer wait times at unprepared and resource-poor rural facilities, deterring youth SRH care seeking. We are unaware of peer-reviewed documentation of this phenomenon elsewhere; however, expect similar trends throughout rural Uganda and other regions where urban schooling/working away from rural communities is common.

Stringent research and public health restrictions limited interviewee numbers and breadth. Ethics approval limited participants to 18 years and older; a broader stakeholder cross-section including more and younger youth would be complementary. Despite limitations, our study proceeded owing to already-secured funding, in-progress approvals, a skilled local interview team, and government engagement, uniquely enabling the capture of experiences during the lockdown.

The extent of poor SRH outcomes reported early in the pandemic is alarming. Emerging documentation supports similar trends elsewhere in Uganda (26,27). Repeated lockdowns, persisting school closures, and mounting case numbers will likely add to this burden. Additionally, the compounding and inter-relatedness of lockdowns, reverse migration, social and economic themes, and their SRH impact (Figure 1) reinforce the need for public health policy that incorporates social disparities, as articulated by the CSDH conceptual framework (14). Solutions must be comprehensive and will be costly.

More studies should quantitatively document the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth SRH and explore longer-term youth health impacts. However, health leaders, policymakers, funders, and implementers should not wait to initiate the critical programming needed to curb current, persisting, and emerging negative youth SRH trends as identified in this study. To manage the complex pandemic consequences, community-based, multi-sectoral programming aligned with CSDH framework themes is needed, especially in high-disparity settings with youth populations, to regain momentum toward global youth SRH targets. Additionally, future pandemic management must seriously consider social, economic, and health disparities amongst youth to mitigate negative effects from necessary public health measures. Youth desire and deserve protected, safe, and confidential access to quality SRH; they are our future, and our future depends on their health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank HAY! team members Barbara Naggayi, Neema Murembe, Joy Muhumuza, Clare Kyokushaba, and Robens Mutatina who supported field data collection and study planning. Promise Anjolaoluwa Adeboye contributed to background context research.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study received approval from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB20-1311) and the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee (16/07-20). All participants provided informed consent.

MANUSCRIPT FUNDING

This study was undertaken with financial support from the Government of Canada provided through Global Affairs Canada (P-006328). A manuscript writing workshop was funded by Mbarara University of Science and Technology.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

SK, EK, ET, JK, and TK received partial salary support through the GAC contribution during the study period. There are no other disclosures. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

SUPPLEMENT FUNDING

This article is part of a special supplement on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth. Production of this supplement was made possible through a financial contribution from the Public Health Agency of Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. World Health Organization; 2020. [cited November 4, 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sarki AM, Ezeh A, Stranges S.. Uganda as a role model for pandemic containment in Africa. Am J Public Health 2020;110(12):1800–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parkes J, Datzberger S, Howell C, et al. . Young people, inequality and violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Uganda - CoVAC Working Paper. University College London, Medical Research Council/Uganda Virus Research Institute & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Raising Voices, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lumu I. COVID-19 response in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Uganda. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020;14(3):e46–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Museveni YK. Address by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni president of the republic of uganda to the nation on the corona virus (covid 19) guidelines on the preventive measures. Entebbe: State house; 2020. [updated March 18, 2020; cited November 2, 2021]. Available from: https://www.mediacentre.go.ug/media/president-museveni-covidc19-guidelines-nation-corona-virus [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coronavirus fears spark urban-rural exodus across. Africa: The Citizen; 2020. [updated March 28; cited November 2, 2021]. Available from: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/news/africa/Coronavirus-fears-spark-urban-rural-exodus-across-Africa/3302426-5507414-ro6i7o/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adams J, MacKenzie MJ, Amegah AK, et al. . The conundrum of low COVID-19 mortality burden in sub-Saharan Africa: Myth or reality? Glob Health Sci Pract 2021;9(3):433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rice BL, Annapragada A, Baker RE, et al. . Variation in SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks across sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Med 2021;27(3):447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO Health Emergency Dashboard. Uganda: World Health Organization; [cited November 2, 2021]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/ug [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda; Rockville, Maryland: Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atuyambe M, Kibira SPS, Bukenya J, Muhumuza C, Apolot RR, Mulogo E.. Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: Evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso district, Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2015;12(35):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The National Population and Housing Census 2014 - Area Specific Profile Series. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. NVivo. 12 ed. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2018. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/support-services/nvivo-downloads [Google Scholar]

- 14. CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kluge H. Statement – Older people are at highest risk from COVID-19, but all must act to prevent community spread. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2020. [updated April 2; cited November 2, 2021]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/statements/statement-older-people-are-at-highest-risk-from-covid-19,-but-all-must-act-to-prevent-community-spread [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G.. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, et al. . Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Youth and COVID-19: Response, recovery and resilience. OECD, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/youth-and-covid-19-response-recovery-and-resilience-c40e61c6/ [Google Scholar]

- 19. COVID-19 and School Closures - One year of education disruption. UNICEF, 2020. https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/COVID19-and-school-closures-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peterman A, Potts A, O’Donnell M, et al. . Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children. Washington DC: Center for Global Development, 2020. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/press/pandemics-and-violence-against-women-and-children/pandemics-and-vawg-april2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. “Everything on her shoulders” - Rapid assessment on gender and violence against women and girls in the Ebola outbreak in Beni, DRC. International Rescue Committee, 2019. https://www.rescue.org/report/everything-her-shoulders-rapid-assessment-gender-and-violence-against-women-and-girls-ebola [Google Scholar]

- 22. Onyango MA, Resnick K, Davis A, Shah RR.. Gender-based violence among adolescent girls and young women: A neglected consequence of the West African Ebola outbreak. In: Schwartz DA, Anoko JN, Abramowitz SA, editors. Pregnant in the Time of Ebola: Women and Their Children in the 2013-2015 West African Epidemic. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23. John N, Roy C, Mwangi M, Raval N, McGovern T.. COVID-19 and gender-based violence (GBV): Hard-to-reach women and girls, services, and programmes in Kenya. Gender and Development. 2021;29:55–71. 10.1080/13552074.2021.1885219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flowe H, Rockowitz S, Rockey J, et al. . Sexual and Other Forms of Violence During the COVID-19 -Pandemic Emergency in Kenya - Patterns of Violence and Impacts on Women and Girls. University of Birmingham, The Institute for Global Innovation, 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/7wghn/ [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burt JF, Ouma J, Lubyayi L, et al. . Indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal, neonatal, child, sexual and reproductive health services in Kampala, Uganda. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(8):3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Right(s) here: Delivering SRHR under COVID-19. UNFPA, 2020. https://uganda.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/rights_here_delivering_srhr_under_covid-19_1_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27. Research findings on the situation of, and impact of COVID-19 on school going girls and young women in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) Uganda Chapter, 2021. [Google Scholar]