Abstract

Objectives

To identify trends in volume of calls to the Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) around the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Analysis of call frequency from VCL administrative records for all veteran contacts calling on their own behalf with gender identified from January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2020. Interrupted time series analysis used to identify potential impact of COVID-19 pandemic on call volume by women and men veteran contacts.

Results

Call volume to VCL from veterans increased over time, for both women and men veterans, with no significant change in call volume by women contacts following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and a decrease in calls by men contacts associated with COVID-19 onset. Call volume varied by month with patterns similar in years prior to and following COVID-19 onset.

Conclusions

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was not associated with a spike in calls by veterans to VCL. The pandemic may have led to an increase in calls by some as well as a decrease in calls by others, leveling out the overall volume trends.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Emerging findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health mitigation measures (e.g., closures, restrictions on gatherings) in the United States indicate increased mental distress, especially among women (Czeisler et al., 2020; Devaraj and Patel, 2021). There is some evidence, both from the United States3 and internationally, of increase in crisis hotline outreach (calls or chats) associated with the onset of COVID-19 and mitigation measures (Arendt et al., 2020; Brülhart et al., 2021).

Military veterans experience elevated levels of mental distress and suicide risk, compared with the general public (Blosnich et al., 2021). Among U.S. military veterans with pre-existing mental health conditions, both contracting COVID-19 and experiencing COVID-19-related stress were found to be associated with increased suicidal ideation (Na et al., 2021). While lags in the availability of mortality data limit our ability to assess whether suicide rates rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, early analyses do not suggest that was the case during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (Devaraj and Patel, 2021).

The Veterans Crisis Line (VCL), administered by the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs, provides crisis services and suicide prevention assessment and intervention to U.S. military servicemembers, veterans and their family members/caregivers through a 24-h hotline accessible via phone, text, or online chat. Given the documented relationship between COVID-19-related stress with increased suicidal ideation among veterans, as well as changes to healthcare availability during the pandemic, it is plausible that veterans have increasingly relied on VCL support during this challenging time. As such, we sought to identify temporal changes in VCL call volume by veteran callers in the context of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and sample

The VCL database used for analysis is completed by VCL responders for each call, text, and some chat content. Variables include date and time of call, veteran status, and gender (limited to male/female binary; identified either by corresponding medical record or VCL responder assessment). For this analysis, we included all contacts to VCL that occurred during calendar years 2018–2020 identified as by a veteran calling on their own behalf and with gender identified. We excluded contacts identified by the VCL responder as prank calls.

2.2. Analysis

We examined overall call volume trends from 2018 through 2020 as well as variation in volume by month. Given gender differences in veterans’ characteristics, experiences, suicide risks, and of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ziobrowski et al., 2017; Zamarro et al., 2020), we examined trends separately for contacts to VCL by women and men veterans. We assessed whether the overall volume and trends in volume by month varied prior to the onset of COVID-19 (2018–2019) versus 2020, when widespread news and impact of COVID-19 had reached the U.S. We calculated average monthly number of contacts per day and conducted an interrupted time series (ITS) analysis to assess for change in call volume over time as well as for changes that may be attributed to the pre/post COVID-19 periods. We operationalized contacts between January 1-December 31, 2019 as “pre-COVID-19 onset” and contacts between January 1-December 31, 2020, as “COVID-19 era.”

3. Findings

Overall, we observed increases in average monthly VCL call volume, for both women and men veterans in 2019 and 2020; this increasing trend was consistent with trends observed from 2018 to 2019, prior to the onset of COVID-19. In the ITS analysis, we did not observe a significant change in average monthly call volume (e.g., no significant up/down ‘jump’) after the onset of COVID-19 for women contacts. However, we did observe a statistically significant decrease in average monthly call volume for contacts by men. Specifically, the ITS analysis indicated an average drop of 507 contacts during 2020 among men. For women, the change in slope following the onset of COVID-19 is negative and statistically significant; for men, a statistically significant change in slope was not observed. Of note, the level change for men and slope change for women are both of very small magnitude, compared to average monthly volume of calls. Thus, the impact of COVID-19 on monthly call volume appears be negligible.

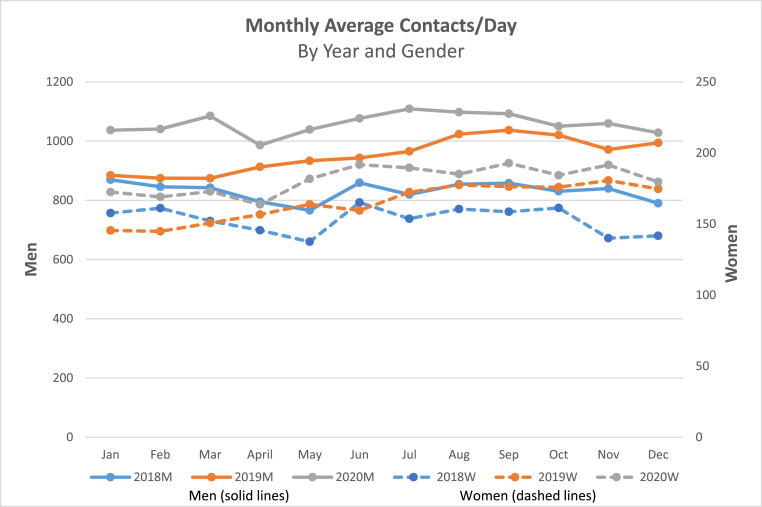

In 2020, we observed the lowest average number of contacts per day by women in the month of April, followed by an increase in May and June, with a peak average number of contacts per day in September (Fig. 1 ). This trend of higher rates of contacts in the second half of the calendar year paralleled a similar trend observed in 2019. For men, in 2020, we observed an increase in contacts per day in March, followed by a decrease in April and then a steady rise to a peak in July. As observed for women, this was similar to what was observed in 2019.

Fig. 1.

Figure footnote: Monthly average contacts per day to the Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) for the period between January 2018–December 2020, for veterans calling on their own behalf with gender identified. Blue lines represent 2018 calendar year, orange lines represent 2019, and grey lines represent 2020. Solid lines represent calls by men veterans and dashed lines represent calls by women veterans. For both men and women veterans, the average monthly VCL call volume increased in 2019 and 2020, consistent with trends from 2018 to 2019. The scales (y axis) for are different by gender to account for the overwhelming majority of the veteran population and veteran VCL callers being men.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted stress, mental health, and well-being in a variety of ways, and with differential impacts by gender (Zamarro et al., 2020). Prior analyses of crisis helpline use across multiple countries found an increase in COVID-related call volume following the onset of the pandemic along with a decrease in non-COVID-related calls (Brülhart et al., 2021). In contrast, we did not observe a substantial increase in VCL contacts associated with the onset of the pandemic in the U.S. Thus, although disruptions in employment and requirements to stay home may have exacerbated stress in some cases, US veterans may have also been benefited from increased social support and a decrease in certain stressors. Further, or alternatively, increased telehealth services in response to the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased access to healthcare care for some veterans, reducing the need for VCL outreach. In addition, some VCL outreach may have been inhibited due to lack of privacy to make a call associated with pandemic lockdowns (i.e., more people being home together). Finally, the VCL is designed and marketed to address a variety of crises, not limited to handling suicide risk. As such, we may be less likely to detect an increase in call volume overall even if the content or reason for calls related to suicide risk did increase. We did not observe major differences in call volume trend by caller gender; variation in monthly trends by gender in 2020 may reflect differential impact of the pandemic on caregiving and employment, thus impacting both stress and mental health as well as availability to utilize resources (Collins, andivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough, 2021; Mooi-Reci and Risman, 2021).

Our data were limited to a particular set of VCL contacts (veterans calling on their own behalf with gender identified). Additionally, the dataset does not include calls that were diverted to a back-up center for a period of approximately one week in Sugg et al., 2019, when VCL staff transitioned to remote work as necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic; this may account for observed decline in call volume in this time period. Despite the need for adjustments to VCL operations in response to the pandemic, however, the program did not experience disruption in service, “continuing to meet performance targets answering 95% of calls within 20 s with an average speed of 9 s” (U.S. Devaraj and Patel, 2021).

As news of the novel coronavirus globally was present in the U.S. at the start of 2020, we examined the full calendar year of 2020 as impacted by the novel coronavirus. The increase in call volume in March 2020 corresponded with the timing of COVID-19 being identified as a pandemic and the implementation of public health measures to mitigate the virus spread. The decrease in call volume in April may have been due to the novelty of the experience, and the perception that impacts would be short-term, increased information through other sources, as well as lack of privacy and opportunity for calls. The rise in contacts in subsequent months is somewhat consistent with seasonal trends of prior years, with the warmer months often corresponding with increased energy to seek help (Sugg et al., 2019) and may also be associated with increased VCL marketing during this time. Further, outreach to VCL during 2020 may have also been impacted but other societal events during this year, in particular the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 and the resulting social action around racial justice and police brutality.

This analysis of call (text and some chat) volume trends for a subset of VCL callers over a three-year period reveals variation by month and gender and little variation associated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, analysis of volume alone is limited in demonstrating the impact of the pandemic on veteran outreach. Further analysis will investigate the content and context of calls related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including examination of potential factors contributing to these trends in call volume.

Author statement

Each author contributed to the study design or analysis, and manuscript: Melissa E. Dichter: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition. Sumedha Chhatre: Methodology, Analysis, Writing. Claire Hoffmire: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Visualization. Scarlett Bellamy: Methodology, Writing. Ann Elizabeth Montgomery: Conceptualization, Writing. Ian McCoy: Data Curation, Writing.

Declaration of competing interest

This study was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development (IIR 18–287; PI: Dichter). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or United States government. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors thank and recognize the contributions of partners from the Veterans Crisis Line and VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention as well as C. Brent Roberts, Aneeza Agha, Katherine Iverson, Lindsay Monteith, and Lauren Krishnamurti for their contributions to the larger study.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This study was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development (IIR 18–287; PI: Dichter). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or United States government. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors thank and recognize the contributions of partners from the Veterans Crisis Line and VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention as well as C. Brent Roberts, Aneeza Agha, Katherine Iverson, Lindsay Monteith, and Lauren Krishnamurti for their contributions to the larger study.

References

- Arendt F., Markiewitz A., Mestas M., Scherr S. COVID-19 pandemic, government responses, and public mental health: investigating consequences through crisis hotline calls in two countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J.R., Garfin D.R., Maguen S., Vogt D., Dichter M.E., Hoffmire C.A., et al. Differences in childhood adversity, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among veterans and nonveterans. Am. Psychol. 2021;76(2):284. doi: 10.1037/amp0000755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brülhart Marius, et al. Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature. 2021:121–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.E., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R.…Rajaratnam S.M. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep; Atlanta, GA: 2020. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation during the COVID-19 - United States, June 24-30, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj S., Patel P.C. Change in psychological distress in response to changes in reduced mobility during the early 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of modest effects from the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021;270 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi-Reci I., Risman B.J. The gendered impacts of COVID-19: lessons and reflections. Gend. Soc. 2021;35(2):161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Na P.J., Tsai J., Hill M.L., Nichter B., Norman S.B., Southwick S.M., Pietrzak R.H. Prevalence, risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. military veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;137:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugg M.M., Dixon P.G., Runkle J.D. Crisis support-seeking behavior and temperature in the United States: is there an association in young adults and adolescents? Sci. Total Environ. 2019;669:400–411. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziobrowski H., Sartor C.E., Tsai J., Pietrzak R.H. Gender differences in mental and physical health conditions in US veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;101:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarro G., Perez-Arce F., Prados M.J. Frontiers in Public Health; Switzerland: 2020. Gender Differences in the Impact of COVID-19. Working Paper. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

Further-reading

- Collins C., Landivar L.C., Ruppanner L., Scarborough W.J. COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021;28:101–112. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention . 2021. National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report.https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2021/2021-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-9-8-21.pdf Retrieved 10/14/21 from. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention . 2021. 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report.https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2020/2020_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G., Levy Y., Sommerfeld E., Segal A., Assa D., Ben-Dayan L., et al. Suicide-related calls to a national crisis chat hotline service during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;139:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]