Abstract

Background

Human cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis is highly prevalent in the Peruvian jungle, where it affects military forces deployed to fight against drug trafficking and civilian people that migrate from the highland to the lowland jungle for economic activities such as mining, agriculture, construction, and chestnut harvest.

We explored the genetic diversity and population structure of 124 L. (V.) braziliensis isolates collected from the highland (Junín, Cusco, and Ayacucho) and lowland Peruvian jungle (Loreto, Ucayali, and Madre de Dios). All samples were genotyped using Multilocus Microsatellite Typing (MLMT) of ten highly polymorphic markers.

Principal findings

High polymorphism and genetic diversity were found in Peruvian isolates of L. (V.) braziliensis. Most markers are not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; this deviation is most likely caused by local inbreeding, as shown by the positive FIS values. Linkage Disequilibrium in subpopulations was not strong, suggesting the reproduction was not strictly clonal. Likewise, for the first time, two genetic clusters of this parasite were determined, distributed in both areas of the Peruvian jungle, which suggested a possible recent colonization event of the highland jungle from the lowland jungle.

Conclusions

L. (V.) braziliensis exhibits considerable genetic diversity with two different clusters in the Peruvian jungle. Migration analysis suggested a colonization event between geographical areas of distribution. Although no human migration was observed at the time of sampling, earlier displacement of humans, reservoirs, or vectors could have been responsible for the parasite spread in both regions.

Author summary

L. (V.) braziliensis is widespread in the Peruvian jungle region. In this region, the departments of Cusco and Madre de Dios account for a large number of patients that get infected while working in the virgin forest. For the first time, we described ample genetic diversity among Peruvian L. (V.) braziliensis isolates with new alleles that were not previously reported in South America. In addition, two different genetic clusters or subpopulations of L. (V.) braziliensis in the Amazon Rainforest of Peru were described. This finding reveals the important distribution of parasite populations and suggests a possible colonization event between ecoregions of the highland and lowland Peruvian jungle independently of recent human migration.

Introduction

In the New World, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) stands out as the most common presentation of leishmaniasis, leading to disfigurement, social stigma, and functional impairment of affected patients [1].

Peru is one of the 10 countries that account for more than 75% of all CL cases reported worldwide [2]. Leishmaniasis is endemic in 19 of its 24 departments, representing more than 70% of its territory [3]. Epidemiological data indicate that between 2015–2020 Peru reported 31,463 cases of leishmaniasis, of which 92% corresponded to CL and 8% to mucosal leishmaniasis (ML) [4].

The most prevalent Leishmania species in the country belong to the L. (Viannia) subgenus and include L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) peruviana, L. (V.) lainsoni, and L. (V.) guyanensis. Inside of Peru, the southern jungle regions of Cusco and Madre de Dios have the highest prevalence of CL, with most cases caused by L. (V.) braziliensis [3].

Despite the importance of leishmaniasis in Peru, there is little knowledge about local genetic diversity and population structure for L. (V.) braziliensis [5,6]. A study found a significant genetic diversity in 25 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis from Pilcopata, Cusco, Peru, co-analyzed with 99 strains from Bolivia using 12 microsatellite markers [6]. They detected a high genetic heterogeneity among local L. (V.) braziliensis strains, suggesting that the population is structured. Another study used 15 microsatellite markers in 31 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis from Brazil, Peru, and Paraguay. Only 6 of these strains correspond to Peru, and these were grouped phylogenetically with strains from the state of Acre, Brazil, and two strains of L. (V.) peruviana from Peru (cluster 3) [5]. Another study showed high genetic variability in 24 isolates of L. (V.) braziliensis using 14 microsatellite markers unrelated to in-vitro drug susceptibility, and clinical phenotypes; neither factorial correspondence analysis nor a phylogenetic analysis revealed geographic structure [7]

Finally, a Brazilian study that used 15 microsatellite markers and 120 strains of various Leishmania species, including 63 L. (V.) braziliensis strains, also found high genetic diversity and three subpopulations partially correlated with Brazilian geography [8]. Other studies have used amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) and whole-genome sequencing to describe Leishmania populations. The first found three subpopulations not linked to their geographical distribution between Peru and Brazil [9] and the second made a description of the possible geographical speciation and diversification of L. (V.) peruviana from populations of L. (V.) braziliensis that were able to cross the Andean mountain range through the Porculla pass during the late Pleistocene [10]. New studies in Peru could improve knowledge about routes of transmission, gene flow, and the role of different genetic variants in parasite virulence, infectivity, pathogenesis, and drug resistance [11–13].

In this study, we analyzed the genetic diversity and population structure of L. (V.) braziliensis from the Peruvian jungle region by Multilocus Microsatellite Typing (MLMT) of 10 polymorphic markers to understand the geographical distribution and population dynamics of this parasite.

Methods

Ethics statement

Samples were collected from patients with clinical suspicion of CL under a U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit 6 (NAMRU-6) human subjects research protocol approved by its Institutional Review Board (IRB) reference number NMRCD.2007.0018, in compliance with all applicable regulations governing the protection of human subjects. All patients participated voluntarily in the study and provided written informed consent.

Study sites

Study sites comprised two ecological regions determined by different climate, geomorphology, hydrology, soil, and vegetation [14,15]: the highland jungle or Rupa-Rupa (400–1000 meters) that includes the departments of Ayacucho, Cusco, and Junín and the lowland jungle or Omagua (80–400 meters) represented by the departments of Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Map of Peru indicating the ecological regions of the highland jungle or Rupa-Rupa (dark green) and the lowland jungle or Omagua (light green), on which the divisions by departments are superimposed.

The collection sites of the L. (V.) braziliensis strains are indicated by colored circles. Loreto in orange, Ucayali in yellow, Madre de Dios in dark-green, Junín in blue, Ayacucho in light-green and Cusco in red. (Modified from a map available at d-maps.com https://dmaps.com/carte.php?num_car=4765&lang=en).

Sample collection

Isolation of Leishmania parasites from a lesion was done as follows: a 21 G, 3 cc, 1 1/2" syringe with a needle containing 0.1 ml of sterile saline solution with 0.1 mg/mL gentamicin and 0.05 mg/ml 5-fluorocytosine was inserted horizontally or perpendicular to the internal border of the ulcer. After the needle was positioned, it was slightly rotated to the left and the right without injecting the saline. The parasite-containing tissue was aspirated and inoculated on Senekjie’s modified biphasic blood agar medium [16]. After 3–5 days, 0.1 ml of liquid phase with promastigotes was mass cultured in 5 ml of Schneider’s Drosophila medium supplemented with 30% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% gentamicin for two or three weeks.

DNA extraction and genotyping of samples

DNA was extracted from promastigotes of Leishmania strains grown in mass cultures using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN, United States). Then, the extracted DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and subsequently used for the detection of species belonging to the L. (Viannia) subgenus by a kinetoplast-DNA-based PCR (kDNA-PCR) [17]. The species were determined by a FRET probes-based Nested Real-Time PCR as previously described [18].

Multi Locus Microsatellite Typing (MLMT)

Ten highly polymorphic neutral microsatellite markers were selected from previous reports and used to determine genetic diversity indexes in the L. (V.) braziliensis strains: AC52, B3H, Ibh3, E11, 7GN, EMI, LBA, ARP, G09, and LRC (Table 1) [5,6,19].

Table 1. Characteristics of microsatellite markers used in this study.

| Locus | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | Motif | Ta(°C) | Dye | Allele size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poolplexing group A | |||||

| B3H | 5’-GGTATGCGTGGATATGAAGC-3′ | (AC)13 | 60 | 6-FAM | 59–93 |

| 5’-CTCGGCATCGCAGTTTC-3′ | |||||

| AC52 | 5′-CATCTACGGCTGATGCAGAA-3′ | (CA)18TA(CA)14 | 58 | NED | 86–140 |

| 5′-CGTCTGGCTAAAGTGGGAAT-3′ | |||||

| Ibh3 | 5′-GGAGAGGCTGCGATGTATCT-3′ | (GT)2GG (GT)2GG(GT)4 | 58 | HEX | 117–133 |

| 5′-CAGGGCTGTCTTGACGAAG-3′ | |||||

| Poolplexing group B | |||||

| E11 | 5′-TGCGTAGGGCAAAGGAGTT-3′ | (GA)10 | 58 | 6-FAM | 93–111 |

| 5′-GGGTGTCTGCCTGCATTC-3′ | |||||

| 7GN | 5’-CTCCTGGAACGGCTAACAC-3′ | (AC)11 | 60 | HEX | 105–131 |

| 5’-TGATATGAGGCACATTCAGC-3′ | |||||

| LBA | 5′-CCTCTGTGAGAAGGCAAGGA-3′ | (GA)11 | 64 | HEX | 165–193 |

| 5’-GCTGCACATGCATTCTCTCGT-3′ | |||||

| EMI | 5′-CGCTGAAGCACGGCGAATG-3′ | (GT)20 | 60 | NED | 180–206 |

| 5′-CGTAGCTCCTCTGTCCGTTC-3′ | |||||

| Poolplexing group C | |||||

| LRC | 5′-CTGCCTCTGCCTCACCTACT-3′ | (GT)17 | 60 | HEX | 112–166 |

| 5′-CTAACCCTCACACTCCCCATC-3′ | |||||

| ARP | 5′-GGCTTCGGTCTGTTCGACTA-3′ | (GT)10 | 60 | NED | 129–173 |

| 5′-CACCCACTCGCATCCGTA-3′ | |||||

| G09 | 5′-CAAGCAGGCAAGAGTCTGAAA-3′ | (CA)3(GA)12 | 60 | 6-FAM | 152–168 |

| 5′-GTCTCCCGTATTGCTCTCTCTA-3′ | |||||

Ta: annealing temperature

PCR was performed in 10 μl mix containing 1X PCR Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.4 μM of each primer, 0.05 U/μl Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher) and 0.4 ng DNA. Fluorophores in the forward primers (6-FAM, HEX, and NED) and PCR conditions were modified from the original publications to eliminate split and stutter peaks [5,6].

Amplification conditions were: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, with a gradient annealing of 55°C to 65°C for each primer for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute; then a final extension step of 72°C for 15 minutes. PCRs were performed in triplicate, and DNA from L. (V.) braziliensis MHOM/BR/84/LTB300 reference strain was used as a positive control of amplification.

PCR products from multiple microsatellite markers were combined in a single lane, a procedure called pseudo-multiplexing or poolplexing (Table 1) depending on allele size and fluorophores wavelength emitted to avoid overlapping between loci [20]. Fluorescently labeled PCR products were separated on 50 cm electrophoresis capillaries with POP7 in a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using GeneScan 350ROX dye as a size standard. Electropherograms were analyzed to determine the allele size-calling using the second-order least squares method provided by GeneMapper v4.0 [21] The reference strain for L. (V.) braziliensis, MHOM/BR/84/LTB300, was used in each electrophoretic run to provide a consistent size marker for each of the ten microsatellite loci [5–8]. The sizes of the identified alleles were recorded in whole numbers for the analysis with GenAlEx 6.5 [22].

Genetic diversity indexes

We calculated the number of alleles (NA), observed heterozygosity (HO), and expected heterozygosity (HE) using the software GenAlEx 6.5. Allelic richness (rn) was calculated through the rarefaction method using FSTAT 2.9.3.2 [23], whereas polymorphic information content (PIC) measures the ability of a marker to detect polymorphisms, was calculated with CERVUS 3.0 [24]. The 95% confidence interval for inbreeding coefficient (FIS) was determined using 100,000 bootstraps for populations in FSTAT. The frequencies of null alleles, stuttering effects, and typographic errors were evaluated by Micro-Checker 2.3.3 [25]. Hardy–Weinberg deviations for each locus, fixation indices FST and RhoST, considering different sample sizes among populations, were estimated with the method of Weir and Cockerham [26] using the software Genepop 4.4 [27]. Additionally, we performed the Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) with ARLEQUIN v3.5 [28] using 10,000 permutations and estimated genetic variation at different levels: 1) among groups or ecoregions, considering the highland jungle or Rupa-Rupa, and the lowland jungle or Omagua, 2) among populations within groups or Peruvian departments within ecoregions (Ayacucho, Cusco, Junín for highland jungle, Madre de Dios, Loreto and Ucayali for lowland jungle; and 3) within populations or between individuals.

Genetic structure and population dynamics

The genetic structure of the L. (V.) braziliensis population was determined through Bayesian grouping analysis by STRUCTURE v2.3 [29] based on an admixture model with K varying from 1 to 10, 30 independent runs were performed for each value of K with a burn-in of 1,000,000, followed by 1,000,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations.

The optimal number of subpopulations was determined using the ΔK method implemented in Structure Harvester v0.6.94 [30]. We performed a factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) using GENETIX [31] to condense allelic frequencies information in factors for multidimensional visualization without a priori assumption of grouping.

Additionally, POPULATION v1.2.32 was used to generate Neighbor-Joining tree using Nei’s minimum distance (DA) [32] and MEGA-X to visualize the phylogenetic tree with radiation topology and circle style.

Linkage disequilibrium analysis

Linkage disequilibrium was assessed using LinkDos [33], assuming that pairs of loci are at linkage equilibrium. The Bonferroni correction was applied to decrease type I errors [34]. Multilocus linkage disequilibrium was evaluated using the method of the standardized index of association (r̄d). We used the R package poppr [35] to test the null hypothesis of no linkage disequilibrium with 1000 permutations.

Colonization history analysis of L. (V.) braziliensis

Different models of gene flow and colonization between lowland (L) and highland (H) jungle were evaluated and compared using a Bayesian approach of the structured coalescent implemented in MIGRATE-N v4.4.4. [36]. Each model was run using a Markov chain Monte Carlo scheme with four parallel chains (heated chains) to support the model selection approach (29). For each locus, ten replicate heated chains were used. Each replicate was burned-in for 100,000 steps and then ran for 1,000,000 steps collecting 100,000 samples every ten steps. We specified prior distributions for the parameter used in the models: the mutation-scaled population size Theta, the mutation-scaled immigration rates, and for some models the mutation-scaled divergence time used a uniform prior distribution with bounds of 0 and 100 generation times mutation rate. The units for the mutation-scaled population sizes were four times the number of individuals times mutation rate per generation, the mutation-scaled immigration rate was immigration rate per mutation rate, and the mutation-scaled divergence time was generation times per mutation rate.

The tested models were: (1) Immigration ongoing and recurrent, assuming that both populations existed for a long time: (a) Migrants only move from L to H. (b) Migrants only move from H to L. (c) Migrants move between both jungles at potentially different rates. (2) Divergence with immigration, considering one population split from the other some time ago: (a) L is ancestral, H is colonized from L, ongoing/directional gene flow L➜H. (b) H is ancestral, L is colonized from H, ongoing/recurrent gene flow between L←→H. (c) L is ancestral, H is colonized from L, ongoing/recurrent gene flow between L←→H. (d) H is ancestral, L is colonized from H, ongoing/directional gene flow H➜L. (3) Divergence without immigration, considering one population split some time ago from the other: (a) H is ancestral, L is colonized from H, no gene flow/migration afterward. (b) L is ancestral, H is colonized from L, no gene flow afterwards. (c) L is ancestral, H is colonized from L, no gene flow afterward. Models 3b and 3c are the same with different prior ranges for divergence in generation times mutation rate. The log marginal likelihoods were used to estimate the log Bayes factor, which was used to estimate the best model.

Results

Optimization of microsatellite markers amplification

The optimal quantity of Leishmania DNA was estimated in 0.4 ng (equivalent to 4.8 x 103 parasites), which is 25 to 250 times less of template DNA than described in previous articles where authors used between 10 ng to 100 ng of template DNA to amplify microsatellite markers of Leishmania by PCR (equivalent to 1.2 x 105 up to 1.2 x 106 parasites) [5,6,19]. All potential artifacts were removed based on suggestions previously described [20,37]. Split peaks, stuttering or shadow bands, and false peaks were eliminated by decreasing primer concentrations in markers 7GN, AC52, ARP, B3H, EMI, and Ibh3 (0.06 μM final concentration of each primer). Optimizing thermal conditions resulted in better hybridization temperatures for most primers at 60°C, whereas AC52, E11, and Ibh3 at 58°C, and LBA at 64°C.

We eliminated fluorescence saturation signal and background noise using a 1:1000 dilution of PCR products for all markers to perform fragment analysis. This process allowed the proper allocation of alleles in most L. (V.) braziliensis isolates. However, no amplification in G09 (four samples) and B3H, EMI, and E11 (one sample each one) were observed (S1 Table). Micro-Checker found the presence of null alleles in all markers in the total population due to an apparent general excess of homozygotes (heterozygous deficit). Also, null alleles were apparently present in the E11 and EMI markers of cluster 1 (N = 25) and the B3H marker of cluster 2 (N = 99) (S2 Table).

The population of L. (V.) braziliensis exhibited high genetic diversity

The 124 L. (V.) braziliensis strains exhibited one or two peaks in all electropherograms analyzed. GenAlEx 6.5 determined that the 124 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis exhibited a high number of alleles per locus with a mean allelic diversity of 14.9, ranging from 6 to 26 alleles per locus (markers Ibh3 and AC52, respectively). Also, the microsatellite markers analyzed in the total L. (V.) braziliensis population showed high average expected heterozygosity (HE = 0.816), slightly higher than observed heterozygosity (HO = 0.669), high mean polymorphic information content (PIC = 0.790) (Table 2), and a mean inbreeding coefficient of 0.18. Genepop v4.4 analysis showed a significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for the observed heterozygote deficit in the majority of markers, except for ARP and G09 (p > 0.05) in the total population (124 strains).

Table 2. Genetic diversity parameters of the 10 L. (V.) braziliensis microsatellite loci.

| Locus | N A | H O | H E | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC52 | 26 | 0.831 | 0.936 | 0.928 |

| B3H | 18 | 0.553 | 0.835 | 0.812 |

| Ibh3 | 6 | 0.266 | 0.556 | 0.506 |

| E11 | 9 | 0.577 | 0.739 | 0.702 |

| 7GN | 13 | 0.734 | 0.853 | 0.833 |

| EMI | 13 | 0.748 | 0.829 | 0.804 |

| LBA | 15 | 0.806 | 0.904 | 0.892 |

| ARP | 20 | 0.855 | 0.922 | 0.913 |

| G09 | 9 | 0.542 | 0.664 | 0.601 |

| LRC | 20 | 0.782 | 0.923 | 0.913 |

| Mean | 14.9 | 0.669 | 0.816 | 0.790 |

NA = allelic diversity, HO = observed heterozygosity, HE = expected heterozygosity, PIC = polymorphic information content. NA, HO, and HE were estimated with GenAlEx 6.5; PIC was estimated with CERVUS 3.0.

On the other hand, genetic diversity parameters showed that strains collected in the lowland jungle had more variability than those collected in the highland jungle when considered the pre-established ecoregions (Table 3).

Table 3. Genetic diversity for each pre-established ecoregion.

| Ecoregion | Strains | N A | H O | H E | F IS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highland jungle | 25 | Mean | 3.400 | 0.329 | 0.386 | 0.169 |

| SD | 0.670 | 0.080 | 0.091 | - | ||

| Lowland jungle | 99 | Mean | 14.400 | 0.753 | 0.781 | 0.041 |

| SD | 1.968 | 0.058 | 0.057 | - |

All parameters were estimated with GenAlEx 6.5.

However, AMOVA analysis showed that most percentages of the variation were between individuals within populations (82.15%) rather than by pre-established groups or ecoregions (9.39%) (Table 4).

Table 4. Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) for L. (V.) braziliensis population.

| Source of variation | Sum of squares | Variance components | Estimated variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Among ecoregions | 74.41 | 0.42 | 9.39 |

| Among departments within ecoregions | 40.66 | 0.38 | 8.46 |

| Between individuals within populations | 887.76 | 3.69 | 82.15 |

| Total | 1002.84 | 4.49 | 100.00 |

Results were determined with Arlequin 3.5.

The population structure of L. (V.) braziliensis showed a marked differentiation by ecoregions

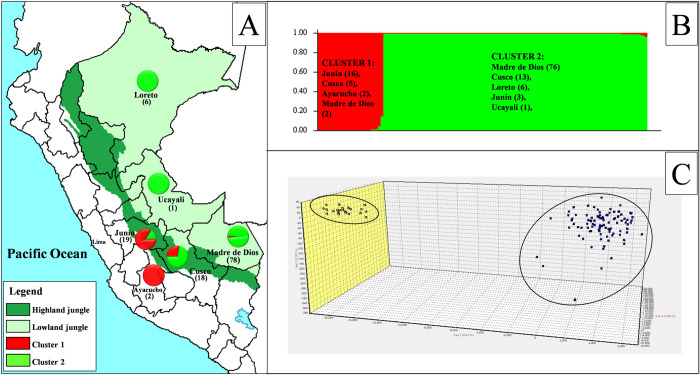

The 124 L. (V.) braziliensis strains were grouped into two genetic clusters by STRUCTURE v2.3 (S3 Table and S1 Fig). Cluster 1 comprised 25 strains, from which 23 were isolated from the highland jungle of the departments of Junín, Cusco, and Ayacucho and two strains from Madre de Dios in the lowland region (Fig 2A and 2B, in red).

Fig 2. Presence of two L. (V.) braziliensis genetic clusters from the Peruvian jungle.

(A) Map of Peru showing the geographical ecoregions where the highland jungle in dark green is represented by samples from the departments of Junín, Cusco, and Ayacucho, and lowland jungle in light green includes samples from Loreto, Ucayali, and Madre de Dios. The pie charts describe the distribution of the two subpopulations inferred where Cluster 1 is in red and Cluster 2 is in green. (The map is based on a public map downloaded from https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=4765&lang=en). (B) Graphic of STRUCTURE v2.3 analysis showing the number of strains isolated by each department with 25 strains for Cluster 1 and 99 strains for Cluster 2. (C) Factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) plot where 25 yellow squares correspond to strains of cluster 1 and 99 dark blue squares represent Cluster 2.

Cluster 2 comprised 99 strains, 83 of these were isolated from the lowland jungle of the departments of Loreto, Ucayali, and Madre de Dios, and 16 strains were from Cusco and Junín (Fig 2A and 2B, in green). The factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) showed a similar grouping (Fig 2C). GenAlEx determined private alleles or alleles unique to a single population; it reported 0.5±0.2 alleles for highland jungle and 11.5±1.8 alleles for lowland jungle. Fixation indices FST (0.319) and RhoST (0.434) showed moderately high genetic differentiation in the two clusters found (S4 Table). In addition, the analysis of the Neighbor-Joining tree confirmed the results showed by STRUCTURE and FCA where Cluster 1 groups 25 strains from Junín, Cusco, and Ayacucho, while Cluster 2 groups 99 strains mainly from Madre de Dios, Loreto, and Ucayali (S2 Fig).

Given the different sample sizes between clusters, the allelic richness analysis after the rarefaction method was based on a sample size of 21 diploid individuals per cluster, which was the smallest number of individuals to be analyzed (Table 5).

Table 5. Allelic richness for both clusters.

| Marker | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 |

|---|---|---|

| AC52 | 2.977 | 18.387 |

| B3H | 1.000 | 10.586 |

| Ibh3 | 1.000 | 3.281 |

| E11 | 2.840 | 5.543 |

| 7GN | 3.000 | 10.345 |

| EMI | 4.840 | 9.847 |

| LBA | 3.000 | 12.451 |

| ARP | 7.634 | 15.164 |

| G09 | 2.000 | 5.637 |

| LRC | 4.677 | 13.722 |

The results were determined with FSTAT 2.9.3.2.

Characterization of subpopulations in Peruvian L. (V.) braziliensis

The mean inbreeding coefficient FIS values were 0.1693 (95% CI 0.0118–0.3085) and 0.0413 (95%CI 0.0204–0.0696) for Clusters 1 and 2, respectively (Table 3).

In addition, pairwise linkage disequilibrium analysis presented 11.1% (5 pairs of loci from 45) and 17.8% (8 pairs of loci from 45) of non-random association between loci after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.001) in Cluster 1 and 2, respectively. Genetic Cluster 1 exhibited standardized index of association, values of 0.060 (p = 0.000) and the Cluster 2, 0.001 (p = 0.429) in the multilocus analysis.

Possible event of colonization in L. (V.) braziliensis

Two geographic units were characterized: the Peruvian highland jungle and lowland jungle. For the statistical analysis, geographic units were treated as two populations, all possible connection models between these two populations were evaluated with MIGRATE-N v4.4.4; these models can be grouped into 1) models of ongoing immigration, 2) models of colonization with migration after the colonization event, and 3) models of colonization without immigration after the colonization event. All models with immigration have model probabilities of 0.0000 and low log marginal likelihoods. Only the model where the highland is colonized from the lowland has high model probability (the models 3b and 3c specify the same model but differ in their prior probability range: 3c investigated events only in the colonization time range of 0 to 50, whereas 3b used a range of 0 to 100 (Table 6). Hence, the occurrence of L. (V.) braziliensis in the highlands is likely a result of a colonization event from the lowlands.

Table 6. Probability of models proposed to analyze possible events of gene flow and colonization.

| Model | Log(marginal Likelihood) | LBF | Model-probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a: | -29428.2 | -3611.72 | 0 |

| 1b: | -28569.2 | -2752.72 | 0 |

| 1c: | -28291.15 | -2474.67 | 0 |

| 2a: | -27422.57 | -1606.09 | 0 |

| 2b: | -26910.43 | -1093.95 | 0 |

| 2c: | -26866.04 | -1049.56 | 0 |

| 2d: | -26714.12 | -897.64 | 0 |

| 3a: | -26097.23 | -280.75 | 0 |

| 3b: | -25816.48 | 0 | 0.9998 (*) |

| 3c: | -25824.81 | -8.33 | 0.0002 (*) |

LBF = Log Bayes Factor.

*Difference between models 3b and 3c was a uniform prior probability of 0 to 100 and 0 to 50 generation × mutation rate, respectively.

Assuming that the parasite lives in the vector insect with a replication time of 7.6 hours and replicates in human hosts every 48.8 hours [38], and based on a wide range of mutation rates for microsatellites [39], we estimate that the limits for the colonization event, in years, were more recent in vectors than in human hosts (S1 File and S5 Table).

Discussion

This study confirms the high genetic diversity in L. (V.) braziliensis from the Peruvian Amazon rainforest with two clusters distributed across the highland jungle, Rupa-Rupa, and lowland jungle, Omagua [14]. Furthermore, it reveals a possible event of past colonization of the highland jungle from the lowland jungle without subsequent gene flow.

The quality and quantity of DNA isolated from in-vitro cultured Leishmania promastigotes were crucial for the successful amplification of the ten polymorphic microsatellite markers by PCR. Previous assays that we performed with DNA extracted from other types of clinical samples like biopsies, lancet scrapping, and filter paper imprints resulted in poor resolution of certain microsatellite markers due to the presence of artifacts, stutters principally, and absence of amplification which made it challenging to identify the true alleles [40].

Most of the ten markers showed new alleles reflecting high polymorphism in the populations of the parasites isolated from different Peruvian regions compared to the range of alleles previously reported (see S6 Table) [5,6]. The finding of high genetic diversity (NA = 14.9, HE = 0.816) is consistent with previous studies conducted in Peru. One of them with 124 L. (V.) braziliensis strains from different countries including 25 strains from the endemic zone of Pilcopata, Cusco showed NA = 12.4 and HE = 0.75 [6]. A second study assessed 56 L. (V.) braziliensis strains from an unknown location in Peru and reported NA = 9.7 and HE = 0.77 [19]. Our study included isolates from the mountainous or highland jungle and swampy or lowland jungle from central and southeast Peru, specifically from endemic regions of Madre de Dios (78 strains) and Cusco (18 strains) adding evidence to published studies about genetic variability in this parasite [6,9,19].

The high genetic diversity that we observe could be explained in part by the type of reproduction of the parasite. Interestingly, both clusters have moderate FIS values, being FIS value for Cluster 2 (FIS = 0.041, associated with lowland jungle) near zero that could suggest high recombination. This result is similar to the high recombination rates suggested for L. (V.) braziliensis from different regions of Peru, using whole-genome sequencing (WGS, 21 isolates, mean FIS = -0.11) [10]. In contrast, Cluster 1 (FIS = 0.169, associated with highland jungle) has a higher FIS value than Cluster 2, suggesting a more recent establishment due to migration or colonization. Our FIS values are lower than those found in Pilcopata, Cusco, Peru (25 isolates in 1993–1994 with FIS = 0.5) and Acre, Brazil (63 isolates from 1980 to 2008 with FIS = 0.519) [6,8]. These two studies had limited samples per geographic region and strong population subdivision (Wahlund effect), suggesting partially clonal populations. Similarly, to eliminate space-time bias leading to a Wahlund effect in our study, more samples should have been collected from other Peruvian regions, but only low numbers of annual cases were reported during years of our collection (2012–2016) compared to higher cases we found in endemic regions of Cusco and Madre de Dios [41]. Also, the linkage disequilibrium between pairs of loci and multilocus for both Peruvian subpopulations of L. (V.) braziliensis was not strong, suggesting that the reproduction could not be strictly clonal similar to the previous report in Brazil [8]. Interspecific genetic recombination or the presence of hybrids in contrast to earlier reports have not been found in our study [42,43].

Although the genetic clusters described are distributed between the ecoregions of highland and lowland jungles, most isolates are from three areas: Junín, Cusco, and Madre de Dios. A deeper analysis indicates significant differences in geographic variation. In particular, the samples from the districts of Tahuamanú, Las Piedras, and Tambopata in Madre de Dios show high variability as a result of the intrapopulation contribution to the diversity found by AMOVA. The higher allelic richness in cluster 2 reinforces the high diversity observed principally in the Omagua and part of Rupa-Rupa regions, compared with the diversity of alleles grouped in Cluster 1 present mainly in the highland jungle. A possible explanation for the extensive diversity may be the presence of several hydrographic basins in Madre de Dios facilitating isolation and genetic variation of the parasite. However, the rivers and altitudinal floors do not seem to be an unbeatable barrier for the dispersal of possible vectors of the subpopulations of L. (V.) braziliensis [44]. Recently we have described the presence of some putative vector species (Lutzomyia auraensis, Lu. davisi) naturally infected with L. (V.) braziliensis in Madre de Dios [45,46]. The same sandfly species were found infected with L. (V.) braziliensis in the Brazilian state of Acre, neighbor to Madre de Dios [47,48]. Remarkably, the two clusters identified here do not appear in an earlier work where the authors, through WGS, focused on the speciation and diversification of L. (V.) peruviana and L. (V.) braziliensis. Their temporal and spatial sampling scheme [10] differs from our study. They collected isolates from 1990 to 2003; most isolates were from Cajamarca, Huánuco, Pasco, and collection altitudes were around 630 meters and higher than 1900 meters. In contrast, our isolates were from 2012 to 2016 and principally from geographical areas lower than 1000 meters from Junín, Cusco, and Madre de Dios. This study [10] suggested high gene flow in contrast with the marked genetic differentiation that we found between the two clusters and the MIGRATE-N results that showed colonization of L. (V.) braziliensis from lowland jungle to highland jungle and posterior populational isolation without gene flow. Discrepancies could derive from differences in the number of representative strain isolates, site of sampling, and methodological approaches used, MLMT versus WGS.

Cluster 2 distributed between the Peruvian lowland jungle and part of the highland jungle could be similar to subpopulation 3 of a previous study that grouped six strains of L. (V.) braziliensis from the mountainous region and lowland jungle of Peru with two strains from the neighboring Brazilian state of Acre, using 15 MLMT loci [5]. Two of those markers were assessed in our study (B3H and 7GN) considering high number of alleles shown. Likewise, Cluster 2 could be similar to subpopulation Pop3A that grouped strains of the Brazilian state of Acre close to the border with Madre de Dios [8].

The observation that some alleles from the lowland jungle were present in the highland jungle, despite the STRUCTURE, FCA, and Neighbor-Joining tree findings of two completely separate L. (V.) braziliensis genetic groups, led us to search for an explanation. We assumed several different models of gene flow and colonization between the altitudinal regions. The role of human migration was investigated because cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis are zoonotic diseases without the involvement of humans in the transmission [49]. In addition, patients from whom parasites were isolated performed different activities: military deployed in the highland jungle (Junín, Cusco, Ayacucho) and civilians living in the lowland jungle (Loreto, Ucayali, Madre de Dios) without contact with each other at the time of sampling. Likewise, known human migration from Cusco and Puno to Madre de Dios through the Interoceanic Highway [50] was dismissed because no contact was observed between both groups of people and no register of possible migration between civilians. The recent colonization event could have been driven by the participation of the vectors and the reservoirs in historical times [46,51–53]. Spanish chroniclers and studies on human skulls reported human migration from the highland jungle to the western Andean valleys [54–56]. More recent human migration from other Peruvian departments to Cusco and Madre de Dios due to economic factors [57] would partially explain the possible recent colonization event, before the time of our study. We do not rule out that patients during written informed consent may give inaccurate data about the geographic location where possibly they became infected. Therefore, the infection may have occurred before they were to work in the highland jungle (military) or in the lowland jungle (civilian population), where they eventually developed the disease.

As mentioned above, the MIGRATE-N results and divergence time in coalescent units showing a recent colonization event from lowland jungle to highland jungle could explain the geographic distribution of Cluster 2 in both regions (S1 File and S5 Table). This event is more recent than the speciation and diversification of the L. (V.) braziliensis complex in the late Pleistocene [10].

No correlation was found between clinical characteristics from patients (size of lesion, location of lesion, number of lesions, time of disease, age of patients, response to treatment) and a particular parasite genetic profile, similar to that already described by many studies [8,58]. Other factors such as the nutritional and immunological status of the patient may explain the differences in disease outcome [8,59,60]. Likewise, different parasite and vector factors explain the pleiomorphism of leishmaniasis [61] that cannot be explained only by the analysis of genetic diversity and population structure described. It is expected that studies applying whole-genome sequencing of Leishmania can provide epidemiological information to design control strategies in endemic regions [62,63].

The high genetic diversity and population structure of L. (V.) braziliensis described in our work will help better understand the evolutionary history of this parasite in Peru [9,10,64,65]. New epidemiological studies may benefit from the knowledge of the distribution of the leishmaniasis agent [66,67] to develop transmission mitigation strategies between military [68,69] and civilian people in endemic areas of Peru [70,71].

Supporting information

(TIF)

The genetic distance was measured by Nei’s minimum distance.

(TIF)

1Precise sizes of amplified fragments that represent genotypes obtained at each of 10 loci by PCR. NA, fragment non-amplified.

(XLSX)

A) Values for all populations. B) Values for cluster 1, 25 isolates. C) Values for cluster 2, 99 isolates.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Multiple potential translations of the divergence time estimate of MIGRATE are given: g, generation; μ, locus mutation rate per generation; the 2.5% and the 97.5% are percentiles of the posterior distribution of the divergence time and mark the boundary of the 95% confidence interval. The microsatellite mutation rate values are not known for Leishmania but are probable values [39]. The generations per year were calculated from replication times in promastigotes and amastigotes [38].

(XLSX)

1Range of allele size reported for 124 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [6] where 25 strains were from Peru. 2Range of fragment size obtained for 31 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [5], where six strains were from Peru. 3Range of fragment size reported for 21 Peruvian strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [7]. 4Range of fragment size found in this study for 124 Peruvian strains of L. (V.) braziliensis.

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Luis Angel Rosales for his great collaboration in taking samples of patients in Puerto Maldonado and thank Christie Joya for the critical revision of this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by an award from the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (AFHSB) and its Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response (GEIS) Section, PROMIS ID P00106_18_N6_04 for FY2018. PB was partly supported by grant DBI 1564822 from the US National Science Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. Lancet; 2005. pp. 1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67629-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS ONE. 2012. p. e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas CM, Franke ED, Cachay MI, Tejada A, Cruz ME, Kreutzer RD, et al. Geographic distribution and clinical description of leishmaniasis cases in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59: 312–317. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centro Nacional de Epidemiologia, Prevencion y Control de Enfermedades. [cited 11 Mar 2020]. Available: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/sala/2020/SE28/leishmaniosis.pdf

- 5.Oddone R, Schweynoch C, Schönian G, De Sousa CDS, Cupolillo E, Espinosa D, et al. Development of a multilocus microsatellite typing approach for discriminating strains of Leishmania (Viannia) species. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47: 2818–2825. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00645-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rougeron V, De Meeû T, Hide M, Waleckx E, Bermudez H, Arevalo J, et al. Extreme inbreeding in Leishmania braziliensis. 2009. [cited 14 Mar 2020]. Available: doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904420106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adaui V, Maes I, Huyse T, Van den Broeck F, Talledo M, Kuhls K, et al. Multilocus genotyping reveals a polyphyletic pattern among naturally antimony-resistant Leishmania braziliensis isolates from Peru. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11: 1873–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhls K, Cupolillo E, Silva SO, Schweynoch C, Côrtes Boité M, Mello MN, et al. Population Structure and Evidence for Both Clonality and Recombination among Brazilian Strains of the Subgenus Leishmania (Viannia). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e2490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odiwuor S, Veland N, Maes I, Arévalo J, Dujardin JC, Van der Auwera G. Evolution of the Leishmania braziliensis species complex from amplified fragment length polymorphisms, and clinical implications. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12: 1994–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Broeck F, Savill NJ, Imamura H, Sanders M, Maes I, Cooper S, et al. Ecological divergence and hybridization of Neotropical Leishmania parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920136117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motoie G, Ferreira GEM, Cupolillo E, Canavez F, Pereira-Chioccola VL. Spatial distribution and population genetics of Leishmania infantum genotypes in São Paulo State, Brazil, employing multilocus microsatellite typing directly in dog infected tissues. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;18: 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira GEM, dos Santos BN, Dorval MEC, Ramos TPB, Porrozzi R, Peixoto AA, et al. The genetic structure of Leishmania infantum populations in Brazil and its possible association with the transmission cycle of visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS One. 2012;7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cupolillo E, Grimaldi G, Momen H. Genetic diversity among Leishmania (Viannia) parasites. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91: 617–626. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1997.11813180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulgar-Vidal, J. Las ocho regiones naturales del Perú. [cited 11 Mar 2020]. Available: https://journals.openedition.org/terrabrasilis/1027

- 15.Brack Egg A MC. Enciclopedia “ECOLOGÍA DEL PERÚ.” [cited 11 Mar 2020]. Available: https://www.peruecologico.com.pe/libro.htm

- 16.Senekjie HA. Biochemical Reactions, Cultural Characteristics and Growth Requirements of Trypanosoma cruzi 1. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1943;s1–23: 523–531. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1943.s1-23.523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez M, Inga R, Cangalaya M, Echevarria J, Llanos-Cuentas A, Orrego C, et al. Diagnosis of Leishmania using the polymerase chain reaction: A simplified procedure for field work. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49: 348–356. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsukayama P, Núñez JH, De Los Santos M, Soberón V, Lucas CM, Matlashewski G, et al. A FRET-Based Real-Time PCR Assay to Identify the Main Causal Agents of New World Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7: e1956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rougeron V, Waleckx E, Hide M, De Meeûs T, Arevalo J, Llanos-Cuentas A, et al. A set of 12 microsatellite loci for genetic studies of Leishmania braziliensis. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8: 351–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guichoux E, Lagache L, Wagner S, Chaumeil P, Léger P, Lepais O, et al. Current trends in microsatellite genotyping. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011;11: 591–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GeneMapperSoftware Version 4.0 Reference and Troubleshooting Guide Front Cover Process Quality Values and Basic Troubleshooting SNPlex System Troubleshooting Algorithms. 2005.

- 22.Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinforma Appl. 2012;28: 2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goudet J. FSTAT (Version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. Journal of Heredity. 1995; 86: 485–486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol. 2007;16: 1099–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P. MICRO-CHECKER: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4: 535–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00684.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michalakis Y, Excoffier L. A generic estimation of population subdivision using distances between alleles with special reference for microsatellite loci. Genetics. 1996;142. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rousset F. GENEPOP’007: A complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8: 103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10: 564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14: 2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earl DA, vonHoldt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4: 359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F, Belkhirr K. GENETIX 4.05, logiciel sous Windows TM pour la génétique des populations. Laboratoire Génome, Populations, Interactions. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nei M, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data II. Gene frequency data. J Mol Evol. 1983;19. doi: 10.1007/BF02300753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garnier-Gere P, Dillmann C. A Computer Program for Testing Pairwise Linkage Disequilibria in Subdivided Populations. J Hered. 1992;83: 239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice WR. Analizing tables of statistical tests. Evolution (N Y). 1989;43: 223–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamvar ZN, Tabima JF, Gr̈unwald NJ. Poppr: An R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ. 2014;2014: 1–14. doi: 10.7717/peerj.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beerli P, Felsenstein J. Maximum-likelihood estimation of migration rates and effective population numbers in two populations using a coalescent approach. Genetics. 1999;152: 763–773. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fishback AG, Danzmann RG, Sakamoto T, Ferguson MM. Optimization of semi-automated microsatellite multiplex polymerase chain reaction systems for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture Elsevier; Mar 15, 1999. pp. 247–254. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00434-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jara M, Maes I, Imamura H, Domagalska MA, Dujardin JC, Arevalo J. Tracking of quiescence in Leishmania by quantifying the expression of GFP in the ribosomal DNA locus. Sci Rep. 2019;9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55486-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seyfert AL, Cristescu MEA, Frisse L, Schaack S, Thomas WK, Lynch M. The rate and spectrum of microsatellite mutation in Caenorhabditis elegans and Daphnia pulex. Genetics. 2008;178. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez Velez ES. Utilidad de muestras clínicas de pacientes para realizar estudios de variabilidad genética de Leishmania (V.) braziliensis, procedentes de diferentes departamentos del Perú. 2019. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12672/11043 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centro Nacional de Epidemiología Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Casos de leishmaniosis por años. Perú 2000–2017. 2017 p. 9. Available: http://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/sala/2017/SE52/leishmaniosis.pdf

- 42.Kato H, Cáceres AG, Hashiguchi Y. First Evidence of a Hybrid of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis/L. (V.) peruviana DNA Detected from the Phlebotomine Sand Fly Lutzomyia tejadai in Peru. Pimenta PF, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10: e0004336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabbabi A, Cáceres AG, Bustamante Chauca TP, Seki C, Choochartpong Y, Mizushima D, et al. Nuclear and kinetoplast dna analyses reveal genetically complex Leishmania strains with hybrid and mito-nuclear discordance in Peru. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zorrilla V, Vásquez G, Espada L, Ramírez P. Vectores de la leishmaniasis tegumentaria y la Enfermedad de Carrión en el Perú: una actualización. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2017;34: 485. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2017.343.2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdivia HO, De Los Santos MB, Fernandez R, Baldeviano GC, Zorrilla VO, Vera H, et al. Natural Leishmania infection of Lutzomyia auraensis in Madre de Dios, Peru, detected by a fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based real-time polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87: 511–517. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zorrilla V, De Los Santos MB, Espada L, Santos R del P, Fernandez R, Urquia A, et al. Distribution and identification of sand flies naturally infected with Leishmania from the Southeastern Peruvian Amazon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11: e0006029–e0006029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teles CBG, dos Santos AP de A, Freitas RA, de Oliveira AFJ, Ogawa GM, Rodrigues MS, et al. Phlebotomine sandfly (Diptera: Psychodidae) diversity and their Leishmania DNA in a hot spot of American cutaneous leishmaniasis human cases along the Brazilian border with Peru and Bolivia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Araujo-Pereira T, De Pita-Pereira D, Boité MC, Melo M, Da Costa-Rego TA, Fuzari AA, et al. First description of Leishmania (viannia) infection in Evandromyia saulensis, pressatia sp. and Trichophoromyia auraensis (psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in a transmission area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Acre State, amazon basin, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sáenz E, Sánchez L, Chalco M. Leishmaniasis tegumentaria: una revisión con énfasis en la literatura peruana. Dermatol Peru. 2017;27. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jensen KE, Naik NN, O’Neal C, Salmón-Mulanovich G, Riley-Powell AR, Lee GO, et al. Small scale migration along the interoceanic highway in Madre de Dios, Peru: An exploration of community perceptions and dynamics due to migration. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18: 12. doi: 10.1186/s12914-018-0152-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies CR, Reithinger R, Campbell-Lendrum D, Feliciangeli D, Borges R, Rodriguez N. The epidemiology and control of leishmaniasis in Andean countries. Cadernos de saúde pública / Ministério da Saúde, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública. 2000. pp. 925–950. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000400013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roque ALR, Jansen AM. Wild and synanthropic reservoirs of Leishmania species in the Americas. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife. Australian Society for Parasitology; 2014. pp. 251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramírez JD, Hernández C, León CM, Ayala MS, Flórez C, González C. Taxonomy, diversity, temporal and geographical distribution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Colombia: A retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2016;6. doi: 10.1038/srep28266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altamirano-Enciso AJ, Marzochi MCA, Moreira JS, Schubach AO, Marzochi KBF. Sobre a origem e dispersão das leishmanioses cutânea e mucosa com base em fontes históricas pré e pós-colombianas. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 2003;10. doi: 10.1590/s0104-59702003000300004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lainson R. The Neotropical Leishmania species: a brief historical review of their discovery, ecology and taxonomy. Rev Pan-Amazônica Saúde. 2010;1. doi: 10.5123/s2176-62232010000200002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frías L, Leles D, Araújo A. Studies on protozoa in ancient remains—A review. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2013. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762013000100001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sánchez A. Migraciones internas en el Perú. Primera ed. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, editor. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. Lima; 2015. Available: https://peru.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl951/files/Documentos/Migraciones_Internas.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aluru S, Hide M, Michel G, Bañuls AL, Marty P, Pomares C. Multilocus microsatellite typing of Leishmania and clinical applications: A review. Parasite. 2015;22. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2015016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Oliveira L, Pereira R, Moreira RB, Pereira De Oliveira M, De Oliveira Reis S, Paes De Oliveira Neto M, et al. Is Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis parasite load associated with disease pathogenesis? Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57: 132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gabriel Á, Valério-Bolas A, Palma-Marques J, Mourata-Gonçalves P, Ruas P, Dias-Guerreiro T, et al. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: The Complexity of Host’s Effective Immune Response against a Polymorphic Parasitic Disease. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/2603730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bañuls AL, Bastien P, Pomares C, Arevalo J, Fisa R, Hide M. Clinical pleiomorphism in human leishmaniases, with special mention of asymptomatic infection. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2011. pp. 1451–1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Awadalla P. The evolutionary genomics of pathogen recombination. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2003. doi: 10.1038/nrg964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Domagalska MA, Dujardin JC. Next-Generation Molecular Surveillance of TriTryp Diseases. Trends in Parasitology. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Momen H, Cupolillo E. Speculations on the Origin and Evolution of the Genus Leishmania. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95: 583–588. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000400023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tuon FF, Amato Neto V, Sabbaga Amato V. Leishmania: Origin, evolution and future since the Precambrian. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008. pp. 158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cupolillo E, Brahim LR, Toaldo CB, de Oliveira-Neto MP, de Brito ME, Falqueto A, de Farias Naiff M, Grimaldi G Jr. Genetic polymorphism and molecular epidemiology of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis from different hosts and geographic areas in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. Jul;41(7):3126–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3126-3132.2003 ; PMCID: PMC165365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schonian G, Kuhls K, Mauricio IL. Molecular approaches for a better understanding of the epidemiology and population genetics of Leishmania. Parasitology. 2011;138: 405–425. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010001538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patino LH, Mendez C, Rodriguez O, Romero Y, Velandia D, Alvarado M, et al. Spatial distribution, Leishmania species and clinical traits of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis cases in the Colombian army. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beiter KJ, Wentlent ZJ, Hamouda AR, Thomas BN. Nonconventional opponents: A review of malaria and leishmaniasis among United States Armed Forces. PeerJ. 2019;2019. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oré M, Sáenz E, Cabrera R, Sanchez JF, De Los Santos MB, Lucas CM, et al. Outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in peruvian military personnel undertaking training activities in the amazon basin, 2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93: 340–346. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coleman RE, Burkett DA, Sherwood V, Caci J, Spradling S, Jennings BT, et al. Impact of Phlebotomine Sand Flies on U.S. Military Operations at Tallil Air Base, Iraq: 2. Temporal and Geographic Distribution of Sand Flies. J Med Entomol. 2007;44: 29–41. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[29:iopsfo]2.0.co;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

The genetic distance was measured by Nei’s minimum distance.

(TIF)

1Precise sizes of amplified fragments that represent genotypes obtained at each of 10 loci by PCR. NA, fragment non-amplified.

(XLSX)

A) Values for all populations. B) Values for cluster 1, 25 isolates. C) Values for cluster 2, 99 isolates.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Multiple potential translations of the divergence time estimate of MIGRATE are given: g, generation; μ, locus mutation rate per generation; the 2.5% and the 97.5% are percentiles of the posterior distribution of the divergence time and mark the boundary of the 95% confidence interval. The microsatellite mutation rate values are not known for Leishmania but are probable values [39]. The generations per year were calculated from replication times in promastigotes and amastigotes [38].

(XLSX)

1Range of allele size reported for 124 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [6] where 25 strains were from Peru. 2Range of fragment size obtained for 31 strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [5], where six strains were from Peru. 3Range of fragment size reported for 21 Peruvian strains of L. (V.) braziliensis in reference [7]. 4Range of fragment size found in this study for 124 Peruvian strains of L. (V.) braziliensis.

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.