Abstract

Membrane vesicles released by Escherichia coli O157:H7 into culture medium were purified and analyzed for protein and DNA content. Electron micrographs revealed vesicles that are spherical, range in size from 20 to 100 nm, and have a complete bilayer. Analysis of vesicle protein by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrates vesicles that contain many proteins with molecular sizes similar to outer membrane proteins and a number of cellular proteins. Immunoblot (Western) analysis of vesicles suggests the presence of cell antigens. Treatment of vesicles with exogenous DNase hydrolyzed surface-associated DNA; PCR demonstrated that vesicles contain DNA encoding the virulence genes eae, stx1 and stx2, and uidA, which encodes for β-galactosidase. Immunoblot analysis of intact and lysed, proteinase K-treated vesicles demonstrate that Shiga toxins 1 and 2 are contained within vesicles. These results suggest that vesicles contain toxic material and transfer experiments demonstrate that vesicles can deliver genetic material to other gram-negative organisms.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is an important pathogen and is thus a serious public health concern. E. coli O157:H7 presents a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, including diarrhea, vomiting, and cramping abdominal pain; more seriously, it also leads to hemolytic-uremic syndrome, an important complication of E. coli O157:H7 infection (17, 23). Although most cases of foodborne illness are associated with consumption of contaminated undercooked ground beef, illness from consumption of contaminated unpasteurized apple cider, lettuce, radish sprouts, alfalfa sprouts, yogurt, mayonnaise, and water has also been reported (6). Factors influencing the survival of E. coli O157:H7 include acid tolerance and resistance to desiccation, while low infective dose and the production of toxins (Shiga toxin and hemolysins) affect pathogenicity (4, 6, 23).

Like other bacteria, E. coli O157:H7 produces membrane vesicles, which may play a role in virulence (12, 24). Vesicle production has been reported in other gram-negative pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (3), Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (16), Bacteroides fragilis (18), and Haemophilus influenzae (11). Vesicles may contain lipopolysaccharide, periplasmic proteins, outer membrane proteins (OMPs), phospholipids, DNA, and other factors associated with the virulence of the producing bacteria (3, 9, 18). For instance, studies have shown that vesicles released by P. aeruginosa contain autolysins (10, 13). Vesicles released from P. aeruginosa are able to fuse with the membranes of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, whereupon they release autolysins, resulting in cell lysis of the targeted organism (10, 13). Research suggests that vesicles released by other pathogens possess enzymatic and toxic activity towards prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (18, 24).

Several reports indicate that vesicles contain DNA and RNA and may have a role in the exchange of genetic material. Some studies have demonstrated that vesicles released by N. gonorrhoeae and H. influenzae can export DNA from the producing strain and transfer DNA to recipient cells (3, 11). Dorward et al. (3) reported that the DNA within vesicles released from N. gonorrhoeae was protected against exogenous nucleases and that vesicles functioned as a system for DNA delivery.

The present study was undertaken to determine whether E. coli O157:H7 produces vesicles under normal growth conditions. Vesicles were analyzed for the presence of Shiga toxins and DNA and for the transfer of virulent genes. We present our findings on purified membrane vesicles released by E. coli O157:H7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

The strains of E. coli used are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were stored in tryptic soy broth (TSB)-glycerol (1:1) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at −20°C. For vesicle isolation, a colony isolated from a Trypticase soy agar plate was inoculated into TSB and incubated for 8 h at 37°C with shaking (150 rpm). The culture was used to inoculate TSB for vesicle isolation.

TABLE 1.

Summary of E. coli isolates

| Strain | Serotype | Stx production | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEC8B | O111:H8 | Stx1, Stx2 | R. Wilsona |

| DEC3D | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | R. Wilson |

| 43895 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | American Type Culture Collection |

| 33694 | NDd | Negative | American Type Culture Collection |

| 93-111 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | P. Fives-Taylorb |

| VDH5 | O157:H7 | Negative | Vermont Department of Health |

| 4516 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | D. G. Whitec |

| 19261 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | D. G. White |

| 8247 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | D. G. White |

| 8302 | O157:H7 | Stx1, Stx2 | D. G. White |

| JM109 | ND | Negative | Promega |

Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pa.

University of Vermont, Burlington, Vt.

North Dakota State University, Fargo, N.D.

ND, not determined.

Vesicle isolation.

TSB (150 ml) was inoculated with 106 E. coli bacteria and incubated at 37°C for 15 h with shaking (150 rpm). Vesicles were harvested from the supernatant according to the method of Kadurugamuwa and Beveridge (9). Briefly, after incubation, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was decanted and passed through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter (Micron Separations, Inc., Westboro, Mass.) to remove the remaining cells and cellular debris. Vesicles were collected by centrifugation (150,000 × g, 3 h, 4°C) with a Ti 45 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.), washed, resuspended in 50 mM HEPES (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) supplemented with 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and stored at −20°C until needed. Vesicle preparations were checked for the presence of E. coli by surface plating of the vesicle suspension on tryptic soy agar and by electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy.

E. coli O157:H7 (early stationary phase) were prepared by using a modified rapid procedure for embedding in Lowicryl K4M (Chemische Werke Lowi, Waldkraiburg, Germany) as described previously (2). Cells were fixed in 0.1% glutaraldehyde–2% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Services, Ft. Washington, Pa.)–phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were collected by centrifugation (11,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C), washed twice in PBS, and then quenched for 30 min in PBS supplemented with 0.15 M NH4Cl and 0.15 M glycine (pH 8.0). The cell pellet was washed with PBS, sequentially dehydrated in N,N-dimethylformamide (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, Wis.), and infiltrated with Lowicryl K4M. Thin sections were mounted on Formvar-coated copper grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Sections were observed with a transmission electron microscope (model 10B; Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, N.Y.).

OMP isolation.

OMPs were isolated as described by Achtman et al. (1). Whole-cell samples were washed two times in 10 mM Tris (pH 8) and lysed by sonication. Whole cells were removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was aspirated into ultratubes (Beckman). A 20% (wt/vol) Sarkosyl (Sigma) solution was added to achieve a final concentration of 2%; the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and then centrifuged (38,000 × g, 1 h, 4°C) to pellet the membrane proteins. The pellet was washed with PBS and resuspended in sterile, distilled, deionized water. Samples were used immediately or were stored at −20°C until needed.

Protein electrophoresis.

Whole-cell, OMP, and vesicle preparations (25 μg of protein) were mixed with sample buffer (no heat treatment) and loaded onto a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins were separated by electrophoresis. Polypeptides were either silver stained (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in PBS (pH 7.2) containing 1 M glycine (Sigma), 5% nonfat dry milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (Fisher) for 1 h at room temperature and washed in TPBS (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20; Fisher). Membranes were probed with rabbit anti-E. coli antibody (antigen for antibody production included whole and lysed cells; Virostat, Portland, Maine) diluted 1:1,000 in TPBS containing 0.1% nonfat dry milk. A peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used for detection, and blots were developed according to the manufacturer (Sigma).

DNase treatment of vesicles.

DNase buffers were made as described by Maniatis et al. (14). To hydrolyze DNA on the surface of the vesicles, 185 μl of vesicle (intact or lysed) sample, 20 μl of 10× reaction buffer, and 3 μl of DNase (1 mg ml−1) were combined and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Reactions were stopped with 50 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). DNase-treated vesicles were subjected to ultracentrifugation for 40 min (30,000 × g, 4°C) in a Ti 40 Beckman rotor, the supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was washed with 500 μl of sterile high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water and centrifuged (30,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of sterile HPLC-grade water and stored at −20°C until needed.

DNA assay.

Surface-associated and intravesicle DNA was quantified by using the Pico Green Assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Vesicles (30 μg of protein) were either used directly or treated with DNase as described previously. Additionally, one-half of the DNase-treated vesicle preparation was lysed by treatment with 5 μl of GES (5 M guanidinium thiocyanate, 100 mM EDTA, 0.5% [vol/vol] Sarkosyl) reagent to release DNA within vesicles. After this course of treatment, only DNA contained within the vesicle remained available for detection. Samples were processed further according to the manufacturer’s directions (Molecular Probes).

DNA isolation.

DNA was isolated from E. coli (intact cells) according to the method of Pitcher et al. (19). Briefly, 100 μl of cells suspended in TE were lysed with 500 μl of GES reagent at room temperature for 5 min. Cell lysates were cooled on ice, and 250 μl of cold ammonium acetate (7.5 M) was added with mixing. After incubation on ice for 10 min, 500 μl of chloroform–2-pentanol (24:1) was added, and the samples were vortexed. Samples were centrifuged (5,000 × g, 10 min), the aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and 0.54 volume of cold 2-propanol was added. Tubes were inverted for 1 min to allow precipitation of DNA. Finally, DNA was pelleted (5,000 × g, 30 s), washed with 70% ethanol, and dried under a vacuum.

PCR protocol.

Primer sets were selected to amplify regions from the virulence genes eae, stx1, and stx2. Primers were also selected to amplify uidA, a gene phenotypically present in >95% of E. coli isolates (5).

The DNA primers used for amplification of the eae gene were SK1 (5′-CCC GAA TTC GGC ACA AGC ATA AGC-3′) and SK2 (5′-CCC GAA TCC GTC TCG CCA GTA TTC G-3′), yielding a PCR product of 863 bp (20). Thirty cycles, each consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 60 s at 60°C, and 60 s at 72°C, were carried out.

Primers for stx1 and stx2 included stx-IF (5′-ACA CTG GAT GAT CTC AGT GG-3′), stx-IR (5′-CTG AAT CCC CCT CCA TTA TG-3′), stx-IIF (5′-CCA TGA CAA CGG ACA GCA GTT-3′), and stx-IIR (5′-CCT GTC AAC TGA GCA CTT TG-3′). Primers for stx1 and stx2 yielded PCR products of 614 and 779 bp, respectively (7). Thirty cycles, each consisting of 60 s at 94°C, 60 s at 55°C, and 60 s at 72°C, were carried out.

Primers for amplification of the uidA gene, M14641:1991U20 (5′-CTC TAC ACC ACG CCG AAC AC-3′) and M14641:2892 (5′-CCT TCT CTG CCG TTT CCA AAT-3′), produce a 922-bp fragment (21). Reaction conditions were 60 s at 94°C, 60 s at 60°C, and 60 s at 72°C for 30 cycles.

For all reactions, amplifications were performed in a total volume of 50 μl, containing 10 μl of intact vesicles, ≥50 pmol of each primer, 2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.), 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Sigma), and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Sigma). A 1-μl aliquot of an E. coli O157:H7 whole-cell suspension (i.e., whole-cell DNA) was used as a positive control for all PCRs. Sterile HPLC-grade water was used as a negative control. All reactions were subjected to a hot start for 5 min at 95°C. PCRs were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 2400 (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Foster City, Calif.). PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels by electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV transillumination. Restriction analysis of purified PCR products confirmed that amplified products were from target genes and not a result of arbitrary priming.

Detection of Stx.

To remove surface-associated Stx, vesicles (50 μg of protein) were treated with 5 μl of proteinase K (200 μg ml−1) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Treated and untreated vesicle samples (50 μg of protein) were loaded onto an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins were separated by electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked, and probed with pooled mouse anti-E. coli O157:H7 Stx1 and Stx2 monoclonal antibody (Toxin Technology, Sarasota, Fla.). Membranes were probed with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody and developed accordingly.

DNA transfer.

E. coli JM109 competent cells (Promega, Madison, Wis.) or noncompetent JM109 cells were used in the experiments. E. coli JM109 noncompetent cells were cultured in LB broth at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) overnight. An aliquot (1 ml) was removed, and cells were pelleted and resuspended in cold SOC medium. A 100-μl cell suspension was transferred to prechilled polypropylene culture tubes, and 100 μl of membrane vesicles (previously treated with DNase) was added; DNase was then added to the suspension to achieve a 1-ng ml−1 concentration. Suspensions were incubated at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for 3 h. Cells were serially diluted (1:10) and plated on LB agar. For experiments with competent cells, cells were thawed and 100 μl of the cell suspension was added to tubes containing 100 μl of DNase-treated vesicles. Tubes were incubated on ice for 10 min, heat shocked for 50 s at 42°C, and placed on ice for 2 min. After the addition of cold SOC medium, the suspensions were incubated at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for 3 h. Cells were serially diluted (1:10) and plated on LB agar. All experiments were completed twice.

Five colonies randomly selected were used in PCRs to determine the presence of the eae, stx1, or stx2 gene. Reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl containing ≥50 pmol of each primer (eae, stx1, or stx2 [see above]), 10× PCR buffer, a 2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 U of Taq polymerase, and sterile HPLC-grade water. PCR conditions were the same as those described above. Controls included E. coli JM109 whole cells, vesicles alone, and PCR cocktail alone (no template DNA).

RESULTS

A transmission electron micrograph shows vesicle formation on the E. coli O157:H7 cell surface (Fig. 1A). It is important to note that vesicles have an intact membrane bilayer and contain electron-dense material. No external material was seen associated with vesicles, suggesting the vesicle surface is free of cellular particulate material. Electron microscopy also suggests that vesicle formation by E. coli O157:H7 follows the model described by Kadurugamuwa and Beveridge (10). Figure 1B shows negatively stained vesicles recovered from the supernatant of E. coli O157:H7 culture medium. Vesicles range in size from 20 to 100 nm and have a uniform, spherical morphology.

FIG. 1.

Cells and vesicles of E. coli O157:H7. (A) Ultrathin sections show vesicles associated with a whole cell. The inset is an enlargement of the enclosed area and clearly shows a vesicle membrane bilayer (arrow). Bar = 50 nm. (B) Negatively stained vesicle preparations demonstrate the uniform size and morphology of vesicles. The arrowheads indicate representative individual vesicles. Note that the vesicles appear to contain electron-dense material. Bar = 250 nm.

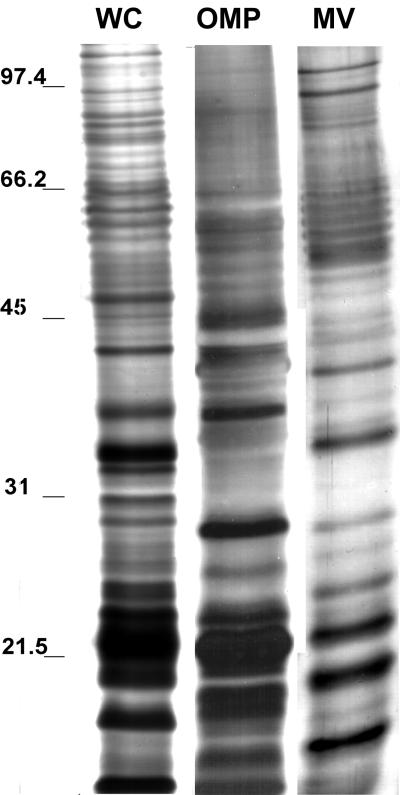

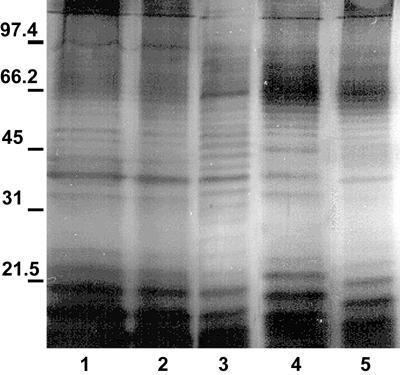

Protein profiles of vesicles, OMP from whole cells, and whole-cell lysates were compared by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Fig. 2). The banding pattern shows that vesicles have many proteins with molecular sizes similar to those of outer membranes and whole cells. Prominently stained bands in lanes containing vesicle preparations were in the range of <31 kDa and corresponded in size to prominent bands in the OMP lane. Vesicle lanes contained a trace amount of proteins that were >45 kDa. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that the vesicles contain many antigens (Fig. 3). This is not surprising since vesicles are derived from the whole cell. Vesicles isolated from all E. coli O157:H7 strains evaluated had similar protein profiles (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE protein profiles of whole cells (WC), OMPs, and vesicles (MV) in a 10% polyacrylamide gel stained with silver stain (samples are from strain E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43895). Each lane contains 25 μg of the total protein. Samples were not heat treated prior to loading. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of E. coli O157:H7 whole cells (WC), OMPs, and vesicles (MV). The blot was probed with polyclonal anti-E. coli antibody. Each lane contains 25 μg of total protein. A 30-kDa protein was highly immunoreactive in the vesicle sample. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE profiles of vesicles isolated from various E. coli O157:H7 strains. Each lane contains 15 μg of total protein. Gels were silver stained. Samples were not heat treated prior to loading. Lanes: 1, VDH5; 2, H8302; 3, B19261; 4, DEC3D; 5, ATCC 33694. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

A sensitive, DNA-specific assay was used to determine whether vesicles contain DNA (Table 2). Intact and lysed vesicle samples were treated with DNase and analyzed for DNA. DNA was detected only in association with intact and DNase-treated intact vesicles. These results suggest that DNA is contained within the vesicle. Moreover, experiments also confirm that vesicles are intact since DNA within the vesicle was protected from hydrolysis by exogenous DNase. The DNA content of vesicles was variable within and between the strains of E. coli vesicles evaluated.

TABLE 2.

DNA content associated with vesicles from E. coli O157:H7 isolates

| Strain | Serotype | Amt (ng) of DNA/30 μg of vesicle protein (avg ± SE)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | Lysedb | ||

| ATCC 43895 | O157:H7 | 1.29 ± 0.43 | 2.54 ± 0.18 |

| 8302 | O157:H7 | 3.77 ± 1.7 | 6.93 ± 1.1 |

| ATCC 33694 | None | 0.347 ± 0.24 | 1.51 ± 0.16 |

n = 3.

Vesicles lysed with GES reagent.

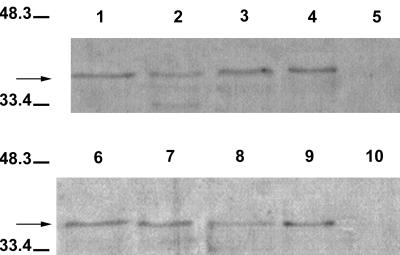

Detection of genetic material within vesicles prompted further examination of DNA for the presence of specific genes. Vesicle DNA was analyzed by PCR for the presence of eae (863 bp), stx1 (614 bp), stx2 (779 bp), and uidA (922 bp) (Fig. 5). E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43895 vesicles isolated from the culture medium of stationary-phase cells were treated with DNase and tested in PCRs with eae, stx1, stx2, and uidA primers. The expected-size DNA fragments were amplified during the PCR, indicating the presence of these genes within DNase-treated vesicles (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Agarose gel analysis of PCR products produced with E. coli O157:H7 vesicle-associated DNA. (A) Profiles for stx1 (614 bp) and stx2 (779 bp). Primers for stx1 and stx2 were used with samples in lanes 1 to 5 and 6 to 10, respectively. Samples in each lane were as follows: lanes 1 and 6, intact vesicles; lanes 2 and 7, intact vesicles treated with DNase; lanes 3 and 8, lysed vesicles treated with DNase; lanes 4 and 9, whole cells; and lanes 5 and 10, negative control (PCR cocktail, no template DNA). The lack of fragments in lanes 3 and 8 and the presence of fragments in lanes 2 and 7 indicate that DNA is located in the vesicles. Moreover, the results indicate that DNase treatment was sufficient to digest vesicle-associated DNA. (B) PCR products of eae (863 bp) and uidA (922 bp) primers. Primers for eae and uidA were used with samples in lanes 1 to 3 and lanes 4 to 6, respectively. Lanes: 1 and 4, intact vesicles (treated with DNase); 2 and 5, whole cells; 3 and 6, negative control (PCR cocktail, no template DNA). Molecular size standards (in kilobases) are indicated on the left.

Western analysis demonstrated the association of Shiga toxin with vesicle preparations (Fig. 6). Bands were present only in lanes containing vesicle preparations from Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Lanes 5 and 10 contained vesicles from E. coli isolates which were Shiga toxin negative. Slight differences in band intensity may be related to differences in the amount of toxin associated with vesicles of a given strain.

FIG. 6.

Immunoblots of Shiga toxin association with E. coli O157:H7 vesicles. The blot was probed with pooled monoclonal antibody against Stx1 and Stx2. Lanes; 1, DEC3D; 2, B4516; 3, H8247; 4, H8302; 5, ATCC 33694; 6, ATCC 43895; 7, B19261; 8, 93-111; 9, DEC8B; 10, VDH5. Note the absence of bands in lane 5 (non-O157, non-Stx-producing isolate) and lane 10 (O157, non-Stx-producing isolate). An arrow indicates the major protein immunologically reactive to pooled monoclonal Stx1 and Stx2 antibody.

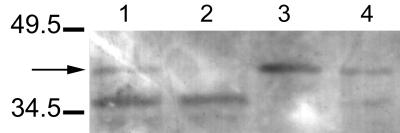

Immunoblot analysis was used to demonstrate that Shiga toxin is located within vesicles (Fig. 7). Intact and lysed vesicles were treated with proteinase K to determine whether toxin(s) is located within the vesicles. A band (41 kDa) corresponding in size to that visualized in lanes containing partially purified Stx1 and Stx2 toxins was visualized in lanes containing intact and lysed vesicles. (Lanes containing purified Stx1 and Stx2 [Toxin Technology] and proteinase K are not shown.) No band was visualized in the lane containing lysed vesicles treated with protease, suggesting Stx is located within vesicles. The prominent band (36 kDa) in the lanes containing proteinase K-treated samples (lanes 1 and 2) is probably the result of the degradation of the protein (Shiga toxin) by proteinase K. Additional faint bands (≤36 kDa) in lanes are likely the result of sample processing. Since pooled monoclonal antibody (containing both Stx1 and Stx2 antibodies) was used, the differentiation of bands associated with Stx1 or Stx2 was not possible.

FIG. 7.

Immunoblot demonstrating that Shiga toxins are located inside vesicles. Intact and lysed vesicles (from E. coli O157:H7) were treated with proteinase K to determine whether Stx is located inside the vesicles. The blot was probed with pooled monoclonal antibody against Stx1 and Stx2. Lanes: 1, intact vesicles treated with proteinase K; 2, lysed vesicles treated with proteinase K; 3, intact vesicles; 4, lysed vesicles. Presence of a band in lane 1 (arrow) and no band in lane 2 indicates that Stx was protected from hydrolysis by virtue of its location within the vesicle (lane 1). Prestained molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Vesicle-mediated transfer of genetic material was demonstrated by PCR amplification of E. coli O157:H7 virulence genes by using recipient E. coli (JM109) cells in the PCR (Table 3). Primers specific for eae (863 bp), stx1 (614 bp), and stx2 (779 bp) were used. Regardless of whether the recipient strain was competent, transfer of genetic material occurred. The extent to which vesicle-mediated transfer of genetic material to E. coli JM109 cells occurs could not be determined from this set of experiments.

TABLE 3.

Transfer of genetic material by vesicles isolated from E. coli O157:H7 to E. coli JM109

| E. coli JM109 cell state | No. of colonies positive/no. tested for target gene:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| eae | stx1 | stx2 | |

| Competent cells | 0/5 | 4/5 | NDa |

| Noncompetent cells | 3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that E. coli O157:H7 releases membrane vesicles and that the vesicles contain nucleic acids and Shiga toxins. DNase- and proteinase K-treated vesicles contained intact DNA and toxins, suggesting that incorporated substances are protected from exogenous enzymes. Vesicle production was a general phenomenon of E. coli O157:H7 growth and, on average, strain ATCC 43895 produced 25.9 (±4.8) μg of vesicles mg of cells−1 under standard culture conditions. These data suggest that vesicle formation by E. coli O157:H7 represents an effective mechanism for the transport and transfer of genetic material and toxins by this pathogen.

Photoelectron micrographs show that vesicles released from E. coli O157:H7 are similar in size and morphology. Vesicles produced by E. coli O157:H7 (average diameter, 50 nm) are comparable in size to vesicles produced by other pathogens (average diameter, 20 to 80 nm) (3, 8, 9). Vesicles released by all of the E. coli strains evaluated (Table 1) were characterized by a well-defined membrane bilayer, suggesting that they originate from the bacterial cell and are not formed during sample processing. According to the model proposed by Kadurugamuwa and Beveridge (9), vesicle formation begins with protrusions, or blebbing, of the outer membrane. As the vesicle expands in size, the periplasm and its contents are taken up into the vesicle. The formation is completed when the vesicle pinches off and is released into the external milieu. Electron micrographs of E. coli O157:H7 vesicles (Fig. 1) show electron-dense material to be present in vesicles during formation and after release into the extracellular milieu, further supporting the hypothesis of Kadurugamuwa and Beveridge (9).

Previous studies show vesicles released from gram-negative bacteria contain DNA, peptidoglycan, enzymes, and toxins (3, 9, 10, 15, 18, 24). It is proposed here that vesicles play a role in the pathogenesis of these organisms through the transport of toxic macromolecules to heterologous and homologous bacteria or to host cells. Vesicles from P. aeruginosa exhibit predatory action towards other bacteria by fusing to the bacterial outer membrane and subsequently releasing degradative enzymes, resulting in cell lysis (13). Lysis of competing bacteria, for instance, would provide nutrients for the vesicle-producing strain and limit competition from other bacteria. Grenier and Mayrand (8) demonstrated that B. gingivalis vesicles adhere to epithelial cells and act as an intermediate for the attachment of bacteria to host cells. More significantly, vesicles have the ability to attach to host cells, thereby promoting attachment of the parent pathogen (vesicle producer) and thus facilitating disease (8, 15).

The SDS-PAGE profiles of the vesicles revealed that the vesicle protein profiles were similar to OMPs (Fig. 2); however, the identity of each protein was not determined. Differences in banding patterns may be associated with cell proteins that were incorporated into vesicles during formation or may result from the enzymatic degradation of OMPs by surface-associated proteases (8). The similarity in protein profiles suggests that vesicles likely have antigens in common with whole bacteria and, in vivo, could compete for antibodies interfering with the immune response. Immunoblot analysis with polyclonal anti-E. coli antibody indicated that vesicles from E. coli O157:H7 possess antigens common to the whole cell (Fig. 3). Similarities in the antigen profile in vitro may have implications in vivo. Vesicles could interfere with the host immune response, serve as antigen in vaccines, or interfere with the accuracy of a rapid immunologically based screening test for the presence of E. coli O157:H7 in food or medical samples.

Sherman et al. (22) demonstrated that OMPs function in mediating the attachment of E. coli O157:H7 to epithelial cells. Perhaps OMPs integrated into vesicles function as a cooperative priming mechanism for the attachment of the producing organism to host cells (i.e., epithelial cells). Vesicles produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans were reported to promote the adherence of the parent cell to epithelial cells (15). Aside from promoting adherence of the vesicle-producing strain to epithelial cells, the vesicles could deliver Shiga toxin directly to the epithelial cells. Toxin within vesicles would be protected from exogenous proteases (Fig. 7) and act to prolong or exacerbate symptoms associated with E. coli O157:H7 infection. The more severe manifestations of E. coli O157:H7 disease, particularly hemolytic-uremic syndrome, are presumed to be the result of Shiga toxin’s cytotoxic action. Shiga toxin released by the organism can travel through the vasculature and interact with specific cell surface receptors (globotriosylceramide, Gb3) and ultimately be internalized by the target cells (17, 23). Immunoblot analysis of vesicles from Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O157:H7 (Table 1) strains demonstrated that toxin association with vesicles is a general phenomenon (Fig. 6). The fate of toxins within vesicles has yet to be determined. The potential role(s) vesicles play in vivo in the disease process is not known.

DNA associated with vesicles was protected from hydrolysis by exogenous DNase, confirming that DNA is located within vesicles. These results suggest E. coli O157:H7 vesicles function in the export and transport of DNA. Vesicles released by P. aeruginosa were reported to harbor DNA; however, its origin was not determined (9). Vesicles isolated from N. gonorrhoeae harbor both linear and circular DNAs (3). When vesicles of N. gonorrhoeae were treated with DNase, circular but not linear DNA remained, suggesting a protective mechanism for plasmid DNA within the vesicles (3). It is not known if incorporation of DNA into E. coli O157:H7 vesicles is a random or a regulated event. Moreover, the source of DNA in E. coli O157:H7 vesicles is not known. To determine the source of DNA and to discriminate between random or regulated incorporation of DNA into E. coli O157:H7 vesicles, primers specific to virulence genes and regulatory genes located on the chromosome were constructed. It is possible that the integration of virulence genes is a regulated event, thereby allowing the transfer of specific genes to other enteric bacteria, thus facilitating genetic divergence. The eae gene is found on the chromosome, while the stx genes are bacteriophage associated and are incorporated into the chromosome. The regulatory gene uidA is located on the chromosome and is phenotypically expressed in >95% of E. coli strains. Detection of uidA implies DNA incorporation is a random event (Table 2; Fig. 5) and that there is no preferential uptake of virulence genes.

In vitro transfer of genetic material by vesicles from gram-negative pathogens to other enteric bacteria has been demonstrated previously (3, 11). Our results demonstrate that E. coli O157:H7 vesicles are able to deliver DNA to recipient E. coli JM109 cells (Table 3). PCR performed on selected colonies demonstrated DNA transfer by vesicles isolated from E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43895 to recipient E. coli JM109 cells. We have not determined yet whether transferred eae, stx1, and stx2 genes are expressed by the recipient E. coli JM109 strain; this is the current focus of our research.

Results of the present study suggest that vesicles produced by E. coli O157:H7 function in the export of toxic and genetic material. Vesicles can facilitate the transfer of genetic material to other enteric organisms and may act to disseminate toxic material directly to host cells or to bacterial cells. Determining whether genes transferred by vesicles are expressed by recipient bacteria is significant in relation to the emergence of new pathogens. Finally, vesicles may have a practical application in vaccine development; safety concerns would be reduced, since the whole organism is not used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Toke for valuable discussions and expert assistance with the PCR studies. We also thank Michael Doyle for providing monoclonal antibody against Stx1. We thank Liqiang Zhou for her technical assistance and Peter Cooke for assistance with electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Mercer A, Kusecek B, Pohl A, Heuzenroeder M, Aaronson W, Sutton A, Silver R P. Six widespread bacterial clones among Escherichia coli K1 isolates. Infect Immun. 1983;39:315–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.315-335.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Call J E, Cooke P H, Miller A J. In situ characterization of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin synthesis and export. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorward D W, Garon C F, Judd R C. Export and intercellular transfer of DNA via membrane blebs of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2499–2505. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2499-2505.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle M P, Schoeni J L. Survival and growth characteristics of Escherichia coli associated with enterohemorrhagic colitis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:855–856. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.855-856.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng P, Lum R, Chang G. Identification of uidA gene sequences in β-d-glucuronidase-negative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;57:320–323. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.320-323.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng P. Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7: novel vehicles of infection and emergence of phenotypic variants. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:47–52. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.950202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gannon V P J, King R K, Kim J Y, Golsteyn Thomas E J. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3809–3815. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3809-3815.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grenier D, Mayrand D. Functional characterization of extracellular vesicles produced by Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1987;55:111–117. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.111-117.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadurugamuwa J L, Beveridge T J. Virulence factors are released from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in association with membrane vesicles during normal growth and exposure to gentamicin: a novel mechanism of enzyme secretion. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3998–4008. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3998-4008.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadurugamuwa J L, Beveridge T J. Bacteriolytic effect of membrane vesicles isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on other bacteria including pathogens: conceptually new antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2767–2774. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2767-2774.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn M E, Barany F, Smith H O. Transformasomes: specialized membranous structures that protect DNA during Haemophilus transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6927–6931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolling G L, Cooke P H, Matthews K R. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Virulence factors associated with extracellular membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli O157:H7, abstr. P-24; p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Clarke A J, Beveridge T J. A major autolysin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: subcellular distribution, potential role in cell growth and division, and secretion in surface membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2479–2488. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2479-2488.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer D H, Fives-Taylor P M. Evidence that extracellular components function in adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4933–4936. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4933-4936.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowotony A, Beling U H, Hammond B, Lai C H, Listgarten M, Pham P H, Sanavi F. Release of toxic microvesicles by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1982;37:151–154. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.151-154.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien A D, Holmes R K. Shiga and Shiga-like toxins. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:206–220. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.206-220.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick S, McKenna J P, O’Hagan S, Dermott E. A comparison of the haemagglutinating and enzymic activities of Bacteroides fragilis whole cells and outer membrane vesicles. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:191–202. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt H, Plaschke B, Franke S, Russmann H, Schwarzkopf A, Heesemann J, Karch H. Differentiation in virulence patterns of Escherichia coli possessing eae genes. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00193628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw, W. K. Personal communication.

- 22.Sherman P M, Soni R. Adherence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli of serotype O157:H7 to human epithelial cells in tissue culture: role of outer membranes as bacterial adhesins. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:11–17. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su C, Brandt L J. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in humans. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:698–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-9-199511010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wai S N, Takade A, Amako K. The release of outer membrane vesicles from the strains of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]