Abstract

Background

Patient-centered care reflecting patient preferences and needs is integral to high-quality care. Individualized care is important for psychosocially complex or high-risk patients with multiple chronic conditions (i.e., multimorbidity), given greater potential risks of interventions and reduced benefits. These patients are increasingly prevalent in primary care. Few studies have examined provision of patient-centered care from the clinician perspective, particularly from primary care physicians serving in integrated, patient-centered medical home settings within the US Veterans Health Administration.

Objective

We sought to clarify facilitators and barriers perceived by primary care physicians in the Veterans Health Administration to delivering patient-centered care for high-risk or complex patients with multimorbidity.

Design

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews from April to July 2020 among physicians across 20 clinical sites. Findings were analyzed with deductive content analysis based on conceptual models of patient-centeredness and hierarchical factors affecting care delivery.

Participants

Of 23 physicians interviewed, most were female (n = 14/23, 61%), serving in hospital-affiliated outpatient clinics (n = 14/23, 61%). Participants had a mean of 21 (SD = 11.3) years of experience.

Key Results

Facilitators included the following: effective physician-patient communication to individualize care, prioritize among multiple needs, and elicit goals to improve patient engagement; access to care, enabled by interdisciplinary teams, and dictating personalized care planning; effortful but worthwhile care coordination and continuity; meeting complex needs through effective teamwork; and integrating medical and non-medical care aspects in recognition of patients’ psychosocial contexts. Barriers included the following: intra- and interpersonal (e.g., perceived patient reluctance to engage in care); organizational (e.g., limited encounter time); and community or policy impediments (e.g., state decisional capacity laws) to patient-centered care.

Conclusions

Physicians perceived individual physician-patient interactions were the greatest facilitators or barriers to patient-centered care. Efforts to increase primary care patient-centeredness for complex or high-risk patients with multimorbidity could focus on targeting physician-patient communication and reducing interpersonal conflict.

KEYWORDS: multimorbidity, qualitative research, patient-centered care, clinical decision-making, health priorities

INTRODUCTION

Care guided by patient preferences, needs, and values is considered patient-centered.1 Patient-centeredness is frequently included in quality standards for health systems and international organizations,1,2 is valued by patients,3 and improves healthcare outcomes.4,5 Patient-centeredness is particularly important for patients with multiple chronic conditions (i.e., multimorbidity). These patients are at higher risk of adverse health outcomes, greater self-management burdens, and conflicting treatment recommendations due to multiple diseases.6–8 These patients—especially those with additional psychosocial complexity—have a greater need for clear communication, shared decision-making, and consideration of individual circumstances during care planning.9–11

Patients with multimorbidity are increasingly encountered by frontline primary care physicians (PCPs).12–14 In the integrated Veterans Health Administration (VHA), over 90% of the highest-risk patients are cared for in general primary care, a patient population overlapping with those experiencing multimorbidity.14–16 The VHA uses a team-based, patient-centered medical home model in over 900 clinics nationwide.17 The model consists of a PCP, nurse care manager, clinical supporter (e.g., licensed practical nurse), and clerical assistant, with embedded multidisciplinary services including behavioral health, social work, and pharmacy. This structure supports PCPs and provides wraparound services beneficial to patients with multimorbidity, especially with psychosocial complexity.18,19

Systematic reviews have summarized how PCPs approach care decisions for patients with multimorbidity.9,11,20 Only a few studies have focused on perceived PCP ability to deliver patient-centered care for these patients,21,22 and none describes this for US PCPs in the unique VHA environment. This study aimed to improve understanding of perceived barriers and facilitators to patient-centered care for complex patients with multimorbidity for this clinician group.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted semi-structured individual telephone interviews with VHA physicians from April to July 2020. We performed a content analysis on transcripts with deductive coding, reaching consensus. Reporting follows standards for qualitative research (SRQR).23 This project was deemed quality improvement under national evaluation efforts for VHA primary care and was not subject to IRB review or waiver. We obtained verbal informed consent from all PCPs.

Researcher Characteristics

The team included CS (a health-services trained, experienced qualitative interviewer) and 3 analysts (SHS as a lead analyst experienced with operationally-partnered VHA research, supervising EW and NJ). The project was led by LS, a health-services trained VHA PCP. Advising and collaboration on interpretation came from GS, a social sciences-trained qualitative researcher, and 3 health-services trained physicians.

Participants

We purposively sampled physician PCPs (MD, DO, or equivalent license), stratifying sampling 50:50 between hospital- and community-affiliated clinics due to care environment differences. Eligible PCPs were non-trainees, working clinically at least 40% time. We determined eligibility from VHA administrative databases. Participants were recruited by email in batches of 25–75 weekly. Due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, to avoid adding to the clinician workload, no follow-up emails were sent to non-responders. LS emailed a total of 475 PCPs; 25 PCPs responded and were interviewed.

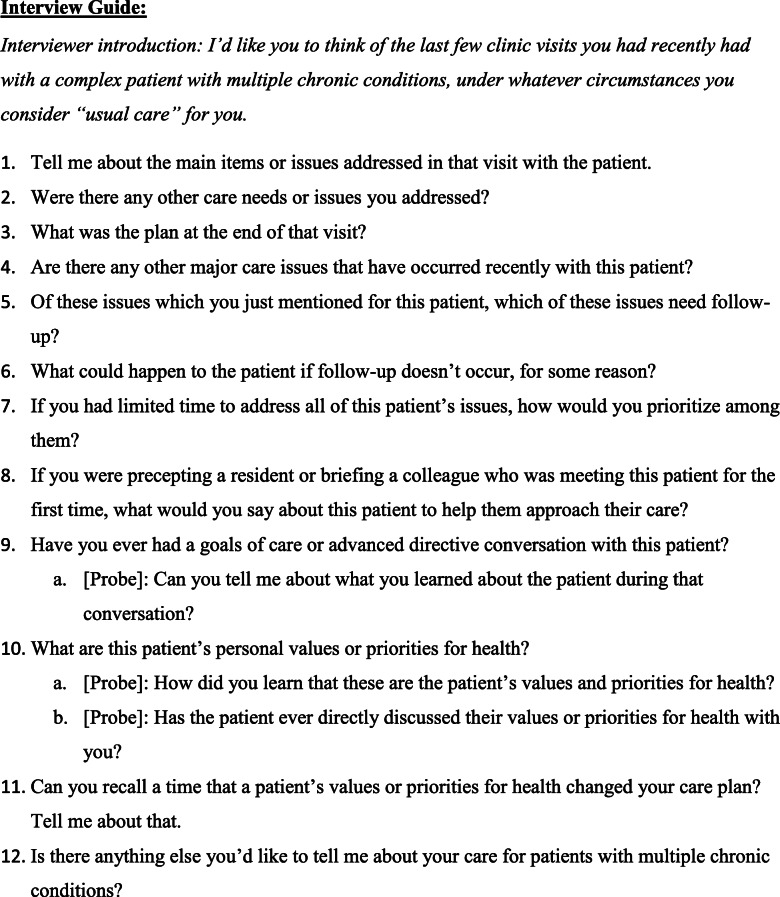

Interviews, Interview Guide, and Data Collection

Our 12-question interview guide (Appendix) asked PCPs to consider recent decision-making for a specific high-risk or complex patient with multimorbidity, how they approached care needs, and how patient needs, preferences, and values affected care planning. The interview guide was iteratively developed by LS, CS, and GS with other co-author input. CS conducted 20- to 30-min telephone interviews with participants. CS and LS met and reviewed audio recordings every 2–3 interviews to check conceptual fidelity and review probes (paraphrasing, interpretive statements). Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were reviewed by LS for accuracy using audio recordings. After reaching the a priori threshold of 20–25 interviews,24 the team reviewed interviews weekly until content saturation was apparent.25 Two interviews were dropped due to unsalvageable audio.

Data Analysis

We analyzed transcripts (n = 23) using MAXQDA software25 with additional processing in Microsoft Excel. SHS conducted initial coding, then met with EW and NJ to review and reach a consensus. A final review and consensus discussion occurred with LS. Deductive coding was developed from existing conceptual frameworks26,27 to align with a rapid, operationally responsive timeline. Barrier codes were based on a hierarchical ecological model of care, describing interactions of levels of factors within a health context.27 The conceptual model of Scholl et al.26 illustrates domains of patient-centered care. In this model, patient-centeredness is composed of dimensions: clinician characteristics (e.g., empathy); partnered clinician-patient relationships; perceiving patients as unique individuals; and biopsychosocial perspectives. The model describes five patient-centered care enablers: clinician-patient communication; integration of medical and non-medical care; teamwork and teambuilding; access to care; and coordination and continuity of care. Facilitators were coded using these enabler categories.26

RESULTS

Participants were mostly MDs (n = 21) in hospital-affiliated clinics (n = 14) across the USA, with an average 20 years’ experience (Table 1). PCPs described facilitators across all five conceptual enablers of patient-centeredness, and barriers across all hierarchical care levels (Tables 2 and 3).

Facilitators of patient-centered care

1A. Physician-patient communication

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Primary Care Physicians (n = 23)

| Demographics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 14 (61) |

| Non-MD degree (DO, MBBS) | 2 (9) |

| Practice affiliation | |

| VHA hospital | 14 (61) |

| Community | 7 (30) |

| Other location | 2 (9) |

| Region | |

| Midwest | 7 (30) |

| Southeast | 7 (30) |

| West | 5 (22) |

| Northeast | 2 (9) |

| Southwest | 2 (9) |

| Clinical environment | |

| General primary care | 17 (74) |

| Women’s clinic | 4 (17) |

| Other setting | 2 (8) |

| Proportion of time spent in clinical role, mean (SD) | 78 (21) |

| Years of experience after residency, mean (SD) | 20.5 (11.3) |

Table 2.

Primary Care Physician Perceptions of Facilitators to Patient-Centered Care

| Summary points | Key quote |

|---|---|

| A. Physician-patient communication: verbal and nonverbal skills that enable patient-centered care | |

| Clear communication is helpful when individualizing and prioritizing among issues | “I ask explicitly from the patient, what it is that they want to accomplish at this appointment; […] I ask that early in the conversation, so that I have as clear a set of expectations from the patient’s perspective as possible. They may align with what my concerns are in terms of problem solving, but knowing that upfront obviously facilitates better communication, better care.” [PCP#20] |

| Eliciting patient goals and what is important enables better engagement | “This patient very much brings up the need to be heard, to be understood, to be reassured, and once that’s happened, then he’s game for trying lots of things.” [PCP#20] |

| B. Access to care: facilitating timely and conveniently located healthcare tailored to patient needs | |

| PCPs personalize care plans according to perceptions of patient access | “Most of the time when I’m taking care of patients, I try to take care of their things right that minute.” [PCP#02] |

| PCPs use care teams to extend and match accessible services to complex patient needs | “I took the disabled parking placard application, walked across the hall, gave that to my RN, and asked her to begin to work on it; then reassured him that we would have that taken care of and the paperwork ready to go by the time he left, and then said, “OK, now let’s focus on some of the other issues that are going on.”[PCP#24] |

| C. Coordination and continuity of care: enabling well-coordinated healthcare allowing continuity across encounters | |

| Care coordination and continuity require effort, but provide better, more individualized care | “We actually made a system where we called up the entire panel of 270 patients to verify their goals of care and healthcare proxies were up to date and really check in about it. […] During that process, we actually learned a lot and changed some.” [PCP#07] |

| D. Teamwork and teambuilding: recognition of effective teams characterized by patient-centered qualities | |

| A multidisciplinary primary care team is key for meeting the diverse needs of complex patients | “I may not have thought of it and the nurse brings it to my attention. She may be closer to the family than me. She’s been there for a long time and knows some patients. Sometimes she may tell me this what the patient is wanting, that changes the plan.” [PCP#04] |

| E. Integration of medical and non-medical care: integrating non-medical aspects of care into healthcare | |

| Patient context and psychosocial issues are part of caring for complexity | “As a primary care provider, I was still needing to be aware, and kind of reviewing with this patient, how his complex pain was affecting his mood and vice versa.” [PCP#20] |

Table 3.

Primary Care Physician Perceptions of Barriers to Patient-Centered Care

| Summary points | Key quote |

|---|---|

| A. Intra- and interpersonal: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, personality aspects or interactions between individuals impeding patient-centered care | |

| PCPs feel some complex patients are unable or unwilling to engage in care | “If he suddenly decides to stop going to his treatments or his follow-ups with oncology, obviously it’s just going to go downhill. Depending on his mood, he may or may not want to contact us.” [PCP#15] |

| PCPs may be unable to offer care plans that meet the patient needs, expectations, or goals | “Our priorities might be a little different because, as with most patients, their first priority is always pain control. That’s not generally my first priority.” [PCP#12] |

| B. Organizational or institutional: facility or system rules, regulations, or informal structures limiting patient-centered care | |

| Complex patient needs do not always align with available services | “That leads to the frustration he has with the types of care that we’re able to provide—he would like us to be able to have someone to come to his house, to inject all of his doses of insulin, and there’s just no service like that available.” [PCP#09] |

| System features can be incompatible with patient-centeredness | “We don’t see our patients very often, which I think is a big issue, because you don’t get to know them very quickly.” [PCP#23] |

| C. Community or Policy: social norms or relationships between individuals or groups, or policies or laws regulating health practices interfering with patient-centered care. | |

| Policy affects meeting complex patient needs in a patient-centered manner | “We don’t take away people’s capacity for anything in [this] state—you can be demented until the very end, and you’ll still be controlling your bank account. […] So you don’t want to jump immediately and scare them away by involving too many people, like the ethics committee, and legal, and all that stuff.” [PCP#03] |

Communication was the main facilitator described by PCPs for delivering patient-centered care for patients with multimorbidity. Many physicians relied on direct, open communication to organize among care needs of complex patients and decide what to address first by eliciting concerns and asking questions to establish acuity.

You have to walk that balance, address their priorities as much as you can, then you’ve got to address anything that might kill them before the next time you could see them. [PCP#03]

PCPs described seeking out and prioritizing patient goals for care, adapting communication, tailoring explanations for patients, and asking about needs to gain patient “buy-in.”

Asking about a patient’s priorities, what happens is they begin to relate what can be done from a medical standpoint to help with their personal goals and by doing that, you get buy-in from the patient. [PCP#08]

Communication was described occasionally as intersectional with integrating medical and non-medical care and care coordination, for example, during discussions including family and caregivers about end-of-life care.

1B. Access to care

Some PCPs discussed either how patient care access or their consideration of patient access facilitated delivering patient-centered care. Access (or perception of access), along with communication, enabled patient agenda-setting in encounters given high numbers of care needs to address and allowed patient goals and priorities to be incorporated into care plans more generally.

I try to attend to everything that they want for that visit first, because like I said, many of my patients drive three hours. [PCP#15]

The primary care team was felt to be important for expanding visit capacity and supplying embedded services for more convenient and patient-centered access, given greater psychosocial needs and care requirements within complex multimorbidity.

The two of them met with our social worker at the end of the visit and then we arranged for him to have a telephone call with my nurse in two weeks to also follow up and […] make sure that things were improving. [PCP#19]

Occasionally, patient access or the perceived in(ability) of the PCP to provide access influenced how emotionally receptive physicians were and their attitudes towards patient needs. For example, one physician mentioned when transitioning to conducting visits remotely, the extra time from not commuting positively impacted that physician’s well-being and presence for patients.

1C. Coordination and continuity of care

A few PCPs described care coordination as facilitating meeting care needs in a patient-centered manner for complex patients. When described, care coordination was usually referenced as a team-based activity interacting with patient-centered access to meet patient needs—particularly with multiple needs to address.

I wrote through Skype to our social worker and coordinated for him to meet with the social worker right after our visit, went in there and shared the situation so there was a warm handoff. [PCP#09]

PCPs noted how coordination affected patient trust and involvement—for example, one PCP described how a lonely patient felt more engaged in care when receiving multiple calls from different providers. PCPs also described that coordinating care required persistence and follow-up visits for residual items left unresolved.

A lot of times with a patient this complex, you know that in that first 60 minutes, they did not tell you everything. [PCP#03]

A few PCPs described how care continuity and knowledge of patients paid off when making nimble care decisions tailored to individual patients.

The plan changed—even though we didn’t see the patient, but we knew the patient. [PCP#04]

1D. Teamwork and teambuilding

Teamwork within multidisciplinary primary care teams was frequently described by PCPs as a facilitator. Those PCPs who discussed teamwork talked about how they could disperse care needs from complex patients and exercise available team roles to meet care goals.

You’ve got all these people that you can disperse some of this person’s needs onto; […] you have to utilize the team and you have to be in constant contact with them.[PCP#03]

Some PCPs described proactively using team members to anticipate the needs of high-risk patients, or follow through on unresolved issues, intersectional with patient-centered access and continuity, as above.

If there’s an issue that needs to be addressed and I’ve got people waiting, I will get my staff and say, “I need you to give this guy a call and dig into this a little bit.” [PCP#11]

1E. Integration of medical and non-medical care

Recognizing the importance of integrating medical and non-medical care for complex patients was described as facilitating patient-centered care by a few PCPs. PCPs brought up how both patient context and psychosocial issues were important to patient-centered care for these patients.

That is also when it came out that he was having trouble navigating his medications, […] so we’ve had Home Health fill his pillboxes, and because he can’t get around, he needs the [activities of daily living] help, and so he’s had a visiting nurse and a home health aide. [PCP#21]

Interactions between medical and non-medical aspects of life were also described—for example, one PCP described a story involving a high-risk patient who refused a nursing home transfer because of concern about leaving a pet dog at home.

-

2.

Barriers to patient-centered care

2A. Intra- and interpersonal

Intra- and interpersonal barriers were commonly described by PCPs and usually discussed together. PCPs often described feeling unable to deliver patient-centered care when they perceived complex patients as reluctant to engage or unable or unwilling to follow through with care. Some PCPs felt they (the physicians) did not always understand the disengagement when it occurred, but others speculated on motivations such as financial, transportation, mental health, mistrust of the medical community, personality conflicts, or prior negative experiences.

I think a lot more [patients] probably have mental health issues that […] don’t get addressed because they don’t admit to them. The resources are there, but you lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink. [PCP#23]

Other PCPs described feeling at an impasse in providing patient-centered care to some high-risk patients in the setting of differing care priorities.

Something I’ve learned about working with the homeless population is my goals are often not their goals. [PCP#00]

Some physicians described difficulty meeting care needs when patients did not disclose needed information. This may be because “when people have multiple problems, they could forget to say something” (PCP#04), or others felt it might be because of a lack of patient ability or desire to articulate needs or concerns.

2B. Organizational or institutional

Time and (in)ability to conduct regular follow-up visits were described by some PCPs as limiting understanding of complex patient needs and meeting patient goals for those with multimorbidity.

I just haven’t had time to really get to know him in terms of why he is the way he is. [PCP#13]

One PCP described how institutional expectations for primary care were changing to be less patient-centric and more focused on care coordination for complex patients.

We’re transitioning to being more managers than care providers. [PCP#12]

Performance metrics also sometimes created pressure that PCPs felt were not patient-centered.

That’s the difference between the metrics people and providers, they’re not sitting in the room and they don’t have access to those other nuances that we do. [PCP#11]

Institutional barriers to providing care within the VHA affected PCP perception of patient-centered care delivery for complex patients. PCPs described barriers related to lapses in scheduling, unmet need for enhanced care management, “mixed messages” (PCP#19) for patients due to multiple clinicians between VHA and non-VHA systems, lack of informational continuity due to system features, or occasionally limited resources impeding meeting needs of high-risk patients.

Referrals that go to community care clinics, […] they can fall through the cracks—sometimes they schedule and sometimes they don’t. [PCP#04]

2C. Community or policy

Barriers extending beyond the organization were rarely noted. At the policy level, when talking about state decisional capacity policy, one PCP described how a patient’s trust could be affected by initiating a formal capacity evaluation. Several PCPs described the intersection of the coronavirus pandemic and care delivery for high-risk patients, particularly how delays and disruptions made care more cumbersome (“because of COVID-19, we have not been bringing our veterans in for routine testing,” explained PCP#22). One PCP described how VHA transportation policies impeded meeting patient needs in a timely manner, recalling a highly rural patient with frequent hospitalizations that would have benefited from greater access to care.

DISCUSSION

Our study identifies perspectives on patient-centered care for multimorbidity from PCPs in the VHA, an integrated US health system with a multidisciplinary, team-based patient-centered medical home primary care model. PCPs described the central importance of communication as a facilitator to patient-centered care, and leveraged communication as a path to tailoring care plans to patients with multimorbidity. Involving the patient in care decisions (i.e., shared decision-making (SDM)) and individualizing care plans were jeopardized when PCPs were unable to elicit the values, preferences, and needs of patients, or when patients and PCPs were unable to agree on care priorities. These findings have been described in clinical decision-making literature,9,11,28 but are notable in occurring in the practice setting of this study.

The key facilitator described by our PCPs was effective, purposeful communication to deliver patient-centered care for patients with multimorbidity. Facilitating individualized care planning, communication was also often intersectional with integrating medical and non-medical care aspects (e.g., when incorporating family views) and care coordination (e.g., with goals-of-care discussions). Communication was an important facilitator of responding to patient needs, reflecting the understanding of patient individuality, and increasing patient engagement in care. Effective communication skills were particularly valued for patients with lower health literacy, complexity due to mental health comorbidities, cognitive impairment, or greater illness burden—an in vivo finding in our study, but previously reported by PCPs during an intervention to promote increased patient-centered care.21 Even in VHA practices with other structural and staffing-based advantages for patient-centered care, communication was still perceived as a primary facilitator by our PCPs—underscoring its foundational role for patient-centered multimorbidity care.20–22,29,30 PCP perception of communication triangulates with studies from the patient perspective of communication facilitating patient-centeredness. Patient perception of better clinician communication correlates with satisfaction, therapeutic alliance, and adherence.31–33

Shared decision-making (SDM) requires understanding patient needs, preferences, and values.34 We found many PCPs recognized SDM was a gateway to delivering patient-centered care for high-risk patients, enabling the use of individualized knowledge to gain buy-in, decide on care matching patient values, and prioritize patient goals. However, the interpersonal barriers to patient-centered care delivery described by our PCPs suggest the SDM process may fail in two scenarios. First, if PCPs are unable to ascertain patient needs, preferences, and values. Complex patients with multimorbidity may have comorbid mental health conditions engendering distrust, may be frustrated by the need to repeat information, or have other challenges in communicating what is most important among numerous care concerns.35,36 Improving PCP-patient communication (especially motivational interviewing skills), promoting trust through relational continuity, and staffing role delineation and function expansion (e.g., clinical assistants taking on health coaching) are strategies that may address this barrier.11,37 Second, SMD may fail if intractable differences in PCP-patient priorities occur—a common phenomenon within multimorbidity.38,39 Encouragingly, there are increasing numbers of successful interventions that dedicate effort to eliciting patient values, preferences, and priorities, and negotiating an agreement on shared priorities for patients with multimorbidity.40,41

Beyond the interpersonal barriers described above, we found several noteworthy organizational barriers to delivering patient-centered care for complex patients with multimorbidity. First, consistent with prior studies and related to their perceptions of patient care access, PCPs were concerned with the time needed to understand patient goals and address numerous needs.9,42 Interventions that asynchronously elicit patient values and goals40 or improve encounter priority-setting may offer solutions.43 Physician perspectives on the effects of time on their own well-being and ability to engage with patients are consistent with findings suggesting greater workload and burnout diminish patient-centered care.44,45 Limited time negatively impacts patients’ perceived experiences when affecting the practice and care team, but not necessarily for individual encounters.46 PCPs may buffer the effect of time on patient experiences, though this may be effortful or create stress for clinicians by reducing perceived access for other patients. Second, our study occurred at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Surprisingly, few physicians (n = 5) directly referenced COVID-related care disruptions, but this may have influenced perceptions of access or time given shifts to telemedicine and disruptions in chronic disease-related care.47,48 Third, unique aspects of working within the VHA arose. Despite the VHA’s system-wide patient-centered medical home17 with benefits to patient satisfaction, care quality, and staffing,49 there are unresolved organizational weaknesses that continue to limit patient-centered care delivery for high-risk patients. Trials of innovative VHA care delivery models focusing on some of the barriers described by our PCPs have improved the patient experience, including perceptions of activation and communication.50 Of interest, despite the potential structural advantages for patient-centered care delivery of the VHA system, such as informational continuity, our PCPs commonly described more universal facilitators and barriers (e.g., intrapersonal communication or conflict) than VHA-specific aspects.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study advances knowledge about PCP’s perceived ability to deliver patient-centered care for patients with multimorbidity. Our findings are supported by literature from other health systems, clinician, and patient populations, improving finding transferability. Our use of a national sample of physicians, data collection until content saturation, and convergence with other literature increase trustworthiness. We note we sampled only VHA physicians and have no data on PCPs not responding to recruitment emails. Our study occurred at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have affected recruitment and PCP experiences. While necessary for our operationally responsive rapid analysis, the use of a deductive analysis framework may have limited exploration of deeper themes. Future analyses will address inductive findings. Our study assessed physician perspectives; we did not validate accuracy from patient perspectives.

Conclusions

This qualitative study of frontline physicians in a large, integrated health system describes perceived facilitators and barriers to delivering patient-centered care for high-risk and complex patients with multimorbidity. Our findings support specific strategies that may benefit organizations and healthcare systems seeking to improve patient-centered care. First, interventions strengthening PCP-patient communication may be well received by frontline clinicians, given the perceived importance of communication in facilitating patient-centered care. Second, designating resources to elicit patient values and care priorities may help align PCPs and patients on shared goals of care and engage patients. Doing so without drawing on PCP workflows may alleviate clinician time concerns. Finally, conflict resolution techniques may help PCP-patient relationships, improving perceived ease of delivering patient-centered care. Attention to these factors within health systems may improve the delivery of patient-centered, high-quality care for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Elsa Sweek, Emily Ashmore, and Rachel Orlando for transcription, comments, and assistance with the background literature.

Appendix. Interview guide

Funding:

This work was supported by the VHA’s Primary Care Analytics Team (PCAT) with funding provided by the VHA Office of Primary Care. Additional funding for the primary author (LS) was from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number K12HS026369). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the University of Washington, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Government.

Data Availability

Data for this study was collected as part of a national evaluation effort through the Veterans Health Administration Office of Primary Care. A deidentified limited dataset supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics and other permissions

This project was deemed quality improvement under the national evaluation efforts for VHA primary care, which was therefore not subject to IRB review or waiver, in accordance with the VHA Office of Research and Development policy describing non-research operational activities. We obtained verbal informed consent to participate and be recorded from all PCPs.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

This work was previously presented as an oral abstract at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Conference (virtual, April 21–23, 2021).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001. Accessed January 24, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/ [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization. Quality Health Services: A Planning Guide. World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336661

- 3.de Boer D, Delnoij D, Rademakers J. The importance of patient-centered care for various patient groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(3):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes TM, Merath K, Chen Q, et al. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am J Surg. 2018;216(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaure CB du, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. Potential workload in applying clinical practice guidelines for patients with chronic conditions and multimorbidity: A systematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010119. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870–2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(12):849-857, W152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sinnott C, Mc Hugh S, Browne J, et al. GPs’ perspectives on the management of patients with multimorbidity: Systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003610. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luijks HD, Loeffen MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, et al. GPs’ considerations in multimorbidity management: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(600):e503–e510. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X652373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damarell RA, Morgan DD, Tieman JJ. General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(669):e245–e251. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X695465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinman MA, Lee SJ, John Boscardin W, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in elderly veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1872–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon J, Zulman D, Scott JY, et al. Costs associated with multimorbidity among VA patients. Med Care. 2014;52(3):S31–S36. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zulman DM, Chee CP, Wagner TH, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilisation among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007771. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang ET, Zulman DM, Nelson KM, et al. Use of general primary care, specialized primary care, and other Veterans Affairs services among high-risk veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e208120. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuttner L, Reddy A, Rosland AM, et al. Association of the implementation of the patient-centered medical home with quality of life in patients with multimorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05429-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosland AM, Wong E, Maciejewski M, et al. Patient-centered medical home implementation and improved chronic disease quality: A longitudinal observational study. Health Serv Res. Published online November 20, 2017. 10.1111/1475-6773.12805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Evidence on multimorbidity from definition to intervention: An overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;37:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuipers SJ, Nieboer AP, Cramm JM. Making care more patient centered: Experiences of healthcare professionals and patients with multimorbidity in the primary care setting. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01420-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuipers SJ, Nieboer AP, Cramm JM. Easier said than done: Healthcare professionals’ barriers to the provision of patient-centered primary care to patients with multimorbidity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):6057. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res. 2000;10(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MAXQDA. VERBI Software; 2019. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.maxqda.com/

- 26.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness: A systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e107828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32(1):307–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):75–80. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient–provider relationship in chronic pain care: Providers’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1688–1697. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuehn BM. Patient-centered care model demands better physician-patient communication. JAMA 2012;307(5). 10.1001/jama.2012.46 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Paddison CAM, Abel GA, Roland MO, et al. Drivers of overall satisfaction with primary care: Evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1081–1092. doi: 10.1111/hex.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zolnierek KBH, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto RZ, Ferreira ML, Oliveira VC, et al. Patient-centred communication is associated with positive therapeutic alliance: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2012;58(2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenberg NE, Leach C, Edwards W. “It’s a toss up between my hearing, my heart, and my hip”: Prioritizing and accommodating multiple morbidities by vulnerable older adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(1):134–151. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith ML, Bergeron CD, Adler CH, et al. Factors associated with healthcare-related frustrations among adults with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(6):1185–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz DA, Wu C, Jaske E, et al. Care practices to promote patient engagement in VA primary care: Factors associated with high performance. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(5):397. doi: 10.1370/afm.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Junius-Walker U, Stolberg D, Steinke P, et al. Health and treatment priorities of older patients and their general practitioners: A cross-sectional study. Qual Prim Care. 2011;19(2):67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, et al. Patient-provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):408–414. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1232-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities–aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salisbury C, Man MS, Bower P, et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: A pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant RW, Lyles C, Uratsu CS, et al. Visit planning using a waiting room health IT tool: The Aligning Patients and Providers randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(2):141–149. doi: 10.1370/afm.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–766. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4011-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1338–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald KM, Rodriguez HP, Shortell SM. Organizational influences on time pressure stressors and potential patient consequences in primary care. Med Care. 2018;56(10):822–830. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright A, Salazar A, Mirica M, et al. The invisible epidemic: Neglected chronic disease management during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2816–2817. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aubert CE, Henderson JB, Kerr EA, et al. Type 2 diabetes management, control and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in older US veterans: An observational study. J Gen Intern Med. Published online January 6, 2022. 10.1007/s11606-021-07301-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration: associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1350. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zulman DM, Chee CP, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. Effect of an intensive outpatient program to augment primary care for high-need Veterans Affairs patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):166–175. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study was collected as part of a national evaluation effort through the Veterans Health Administration Office of Primary Care. A deidentified limited dataset supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.