Abstract

Quercetin (QUE), a health supplement, can improve renal function in diabetic nephropathy (DN) rats by ameliorating podocyte injury. Its clinical trial for renal insufficiency in advanced diabetes (NCT02848131) is currently underway. This study aimed to investigate the mechanism of QUE protecting against podocyte injury to attenuate DN through network pharmacology, microarray data analysis, and molecular docking. QUE-associated targets, genes related to both DN, and podocyte injury were obtained from different comprehensive databases and were intersected and analyzed to obtain mapping targets. Candidate targets were identified by constructing network of protein-protein interaction (PPI) of mapping targets and ranked to obtain key targets. The major pathways were obtained from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis of candidate targets via ClueGO plug-in and R project software, respectively. Potential receptor-ligand interactions between QUE and key targets were evaluated via Autodocktools-1.5.6. 41. Candidate targets, of which three key targets (TNF, VEGFA, and AKT1), and the major AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications were ascertained and associated with QUE against podocyte injury in DN. Molecular docking models showed that QUE could closely bind to the key targets. This study revealed that QUE could protect against podocyte injury in DN through the following mechanisms: downregulating inflammatory cytokine of TNF, reducing VEGF-induced vascular permeability, inhibiting apoptosis by stimulating AKT1 phosphorylation, and suppressing the AGE-induced oxidative stress via the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

Podocyte injury is a critical event resulting in the eventual podocyte loss in the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN), accounting for 40–45% of patients with diabetes mellitus [1–3]. Moreover, podocytes and podocyte-specific proteins are potential urinary markers to detect the early diagnosis of DN, and low podocyte density, correlating directly with the magnitude of proteinuria, is a strongest predictor for progression of DN [4]. Furthermore, podocyte injury results in permanent alterations in the glomerular filtration barrier in DN [5, 6]. Podocytes are core cells of the glomerular filtration barrier and terminally differentiated parietal epithelial cells with a very limited proliferation ability [7].

Recently, podocyte injury has been regarded as a novel early mechanism involved in DN [8]. In the progress of DN, hyperglycemia (HG) induces the excessive accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) with reactive oxygen species (ROS), initiating podocyte injury accompanied with proteinuria and ultimately accelerating the development of DN [9, 10]. Podocytes are also targets of AGEs in diabetes by increasing AGE receptor (RAGE) expression [11]. The activated AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (AGEs binding to RAGE) increasing expressions of proinflammatory cytokine and oxidative stress is closely associated with podocyte injury and has been confirmed exactly one of the mechanisms of DN occurrence [12, 13]. However, the alleviation of podocyte injury in DN is mainly to control HG or proteinuria for the management of renal damage [3, 14], but lacks targeted agents. So, drugs targeting podocyte injury are urgently needed to treat DN and will be one of the most promising field of inquiry [13].

Quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone, QUE) belongs to natural flavonoids that are commonly defined as dietary antioxidants [15]. It has significant therapeutic effects on DN by reducing proteinuria which is a typical clinical manifestation mostly resulted from the podocyte injury [16, 17]. Moreover, it can reduce the oxidative stress, inflammatory responses and apoptosis involved in the progression of DN [18, 19]. Many clinical trials of QUE, including clinical research for renal insufficiency in advanced diabetes (clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT02848131) are currently underway (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) [20, 21]. In vitro experiments have confirmed that QUE reverses diabetes-induced podocyte injury by increasing the expression level of nephron and podocin in podocytes [20, 22, 23].

QUE is a phytochemical contained in many Chinese herbs such as Astragalus membranaceus (ASM) and Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge (SMB). ASM has been reported to have protective effects on podocyte injury and SMB can ameliorate diabetic vascular injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [24, 25]. However, the molecular mechanism of protects against podocyte injury in DN is lacking. Fortunately, network pharmacology can decipher the mechanism of drugs action with a holistic perspective, which breaks through the “one drug, one target” in the traditional drug discovery model and realizes the synergy of multiple targets [26]. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the mechanism of QUE protecting against podocyte injury to treat DN through network pharmacology [26], microarray data analysis, and molecular docking.

2. Materials and Methods

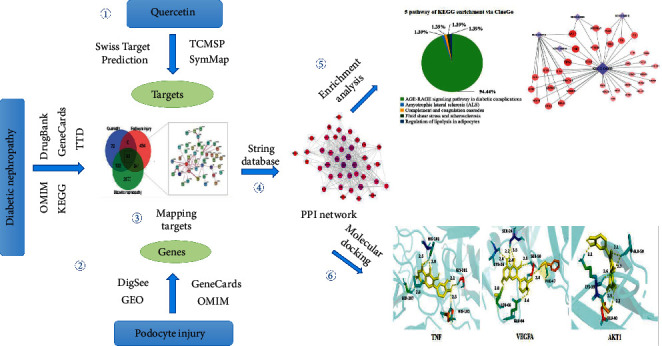

The flowchart of this study design about the network pharmacology method used to clarify the key targets and the major pathway of QUE protecting against podocyte injury is shown in Figure 1, including six parts: searching QUE-associated targets, screening genes related to DN and podocyte injury, retrieving of mapping target interaction proteins, constructing protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, enrichment analysis, and molecular docking.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of network pharmacology method used in this study.

2.1. Searching QUE-Associated Targets

Targets of QUE were searched from the following three databases with the keyword “quercetin.” One is the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology database [27] (TCMSP, https://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/) which focuses on the exploration of the targets from the HIT database, SysDT model, and targets validated by experiments [27]. Another is the SwissTargetPrediction database [28] (https://www.swisstargetprediction.ch) which estimates the most probable targets of QUE in view of 2D and 3D similarity between QUE and known activities in this database [29]. The third is the SymMap database [30] (https://www.symmap.org/) which builds a large heterogeneous network by combining 19595 herbal ingredients and 4302 target genes related to symptoms [30]. After deleting repeated targets, all the unique targets obtained were considered to be regulated by QUE.

2.2. Obtaining Genes Related to DN and Podocyte Injury

Genes associated with DN were retrieved from five comprehensive databases, including the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database [31] (OMIM, https://www.omim.org/), DrugBank database [32] (https://www.drugbank.ca/), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway Database [33] (KEGG, https://www.kegg.jp/), and Therapeutic Target Database [34], (TTD, https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/) with the keyword “diabetic nephropathy,” as well as GeneCards database [35] (https://www.genecards.org/), with the keyword “[all] (diabetic nephropathy) and [all] (Homo sapiens).”

Genes related to podocyte injury were searched from four databases: OMIM and DigSee database [36] with the keyword “Podocyte injury” (https://210.107.182.61/digseeOld/), GeneCards database with the keyword “[all] (podocyte injury) and [all] (Homo sapiens),” and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [37] with the keyword “(Podocyte injury) AND “Homo sapiens”[porgn: txid9606].” From the GEO database, a human gene expression data series (GSE51834) [38] titled “Indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin and aryl-hydrocarbon receptor ligand, mediates progressive glomerular disease by damaging podocytes” published in 2014, was selected to explore differential genes (DEGs) of podocyte injury. There was a series matrix file that included three podocyte injury samples and three control samples in this series. The DEGs were gathered by comparing these two types of samples with fold change (FC) of genes expression (|logFC| ≥ 1) and false discovery rate (P < 0.05) using the Limma package [39] of the R project software.

2.3. Constructing Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) of Mapping Targets and Identifying Candidate Targets

QUE-associated targets, podocyte injury-related genes, and DN-associated genes were subjected to intersection analysis to identify the mapping targets that were considered to be highly relevant to QUE protecting against podocyte injury in DN. The “protein-protein interaction (PPI)” topological network of the mapping targets was constructed using the STRING database [40] (https://string-db.org) using Cytoscape 3.71 [41]. The nodes of this network represent proteins, and the edges represent the interactions between the two proteins. The targets having interactions with a probabilistic association confidence a score ≥0.4 were identified candidate targets. The network topology parameters, including the “degree” of targets in the PPI network were analyzed using the Network Analyzer plug-in of Cytoscape. The top three targets with the highest “degree” values were defined as three key targets for QUE protecting against podocyte injury in DN.

2.4. Enrichment Analysis of GO Term and KEGG for Candidate Targets using ClueGO and R Project, Respectively

The candidate targets were imported into the ClueGO plug-in [42] of Cytoscape and R project for Gene Ontology (GO) term and KEGG enrichment analysis, respectively, to decipher the molecular mechanisms of QUE protecting against podocyte injury. The results gathered from above two enrichment software were further analyzed and compared, and the most reliable signaling pathway (the largest percentage or the lowest P value) was considered to be the major pathway for QUE protecting against podocyte injury in DN.

GO terms describe the biological function of genes through three semantic terms, namely, biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) [43]. KEGG consists of artificially annotated metabolic pathways and defines the complex interrelationship between genes and metabolites [33]. R project software has been widely used in network pharmacology studies for screening of DEGs, enrichment, and annotation analysis [37, 44].

2.5. Docking QUE with Key Targets

The interaction between QUE (ligand) and key targets (receptors) were evaluated using Autodocktools-1.5.6 [45] and visualized through PyMOL [46], being able to calculate and analyze the binding affinity and binding energy. The structure of QUE (as a mol2 file) and the targets (as a PDB file) were downloaded from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the Protein Data Bank database (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/pages/contactus), respectively.

3. Result

3.1. QUE-Associated Targets

A total of 355 targets of QUE (Supplementary Table 1) were obtained from TCMSP (148 targets), SwissTargetPrediction (99 targets), and SymMap (108 targets) databases, and 247 unique targets of QUE were gathered after deleting 108 repeated targets. And, there were six targets (AKT1, TOP1, PARP1, MMP9, MMP3, and MMP2) recorded in those three databases.

3.2. 3387 Genes Associated with DN and 816 Genes Related to Podocyte Injury

A total of 4895 human genes (Supplementary Table 2) associated with DN were identified from those five databases, and 3387 unique genes of DN were obtained after deleting 1508 duplications.

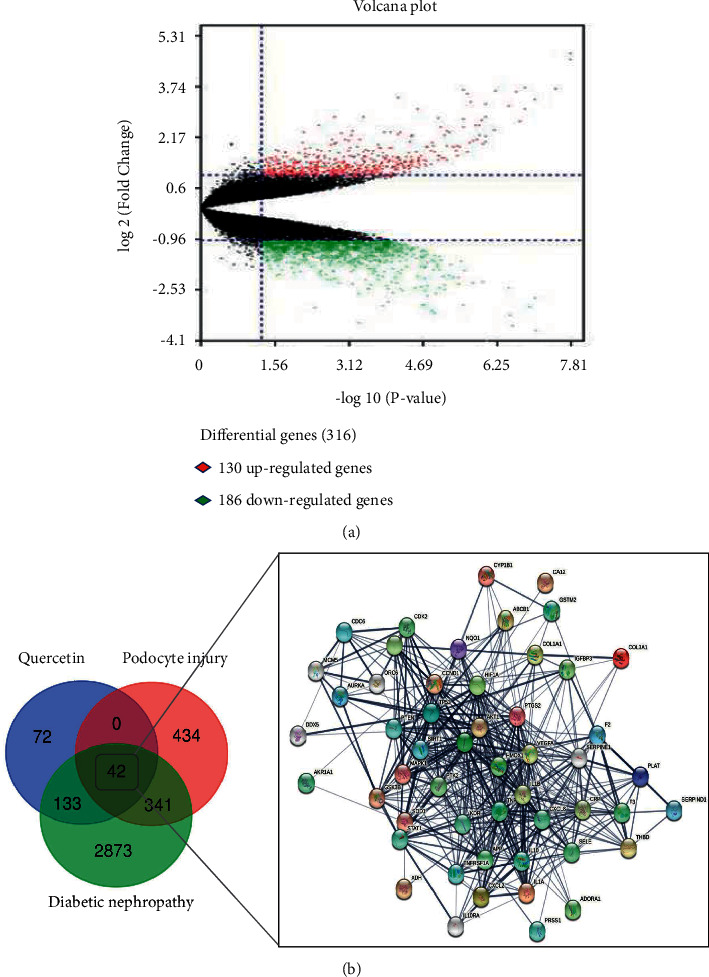

848 human genes (Supplementary Table 3) related to podocyte injury were identified, of which 316 were DEGs (130 upregulated genes, including TNFAIP6, TNFAIP3, and VEGFA and 186 downregulated genes, including TNFRSF19 and COL1A1) (Figure 2(a)), 532 of which were obtained from the OMIM (191 genes), GeneCards (339 genes), and DigSee (2 genes) databases. Totally 816 unique genes of podocyte injury were gathered after deleting 32 duplications.

Figure 2.

(a) Volcano map of 316 differential genes of podocyte injury. The 130 upregulated genes are presented in red, whereas 186 downregulated genes are presented in green. (b) Venn diagram and PPI network showed the 42 mapping targets of QUE protects against podocytes injury in DN.

3.3. 41 Candidate Targets from PPI Network Analysis of 42 Mapping Targets Related to QUE, DN, and Podocyte Injury

Through intersection analysis QUE-associated targets, DN-associated genes and podocyte injury-related genes, 42 mapping targets (Figure 2(b), Supplementary Table 4) were identified closely related to QUE protecting against podocyte injury in DN.

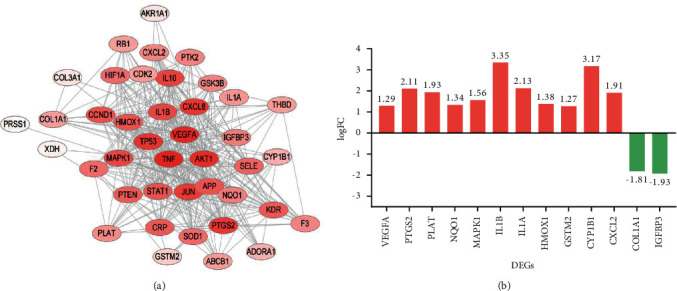

In total, 41 candidate targets (Figure 3(a), Supplementary Table 5), including 13 DEGs (2 downregulated and 11 upregulated genes (Figure 3(b)) were identified through the PPI network of 42 mapping targets. The PPI network contained 41 nodes, 340 edges with an average “degree” value (the mean number of connections per node) of 16.585. There were 21 candidate targets with a “degree” value ≥average “degree” (Table 1), and the top three targets TNF, VEGFA, and AKT1 ranked by degree were identified as the key targets of protecting against podocyte injury in DN.

Figure 3.

(a) 41 candidate targets obtained from network of “protein-protein” interaction (PPI), including three key targets TNF (degree = 34), VEGFA (degree = 33), and AKT1 (degree = 31). The color of the nodes is shown in a gradient from to red to transparent according to the degree value. (b) 13 DEGs contained in 41 candidate targets, the red bars represents11 upregulated genes (log C 1), and the green bars represents 2 upregulated genes (log FC < −1).

Table 1.

21 candidate targets with a degree greater than average.

| Target | Uniprot ID | Description | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | P01375 | Tumor necrosis factor | 34 |

| VEGFA | P15692 | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 33 |

| AKT1 | P31749 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 | 31 |

| TP53 | P04637 | Tumor protein p53 | 29 |

| PTGS2 | P35354 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | 28 |

| CXCL8 | Q9UI36 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 | 28 |

| JUN | P05412 | Jun proto-oncogene, | 27 |

| IL10 | P22301 | Interleukin-10 | 25 |

| IL1B | P01584 | Interleukin-1 beta | 24 |

| MAPK1 | P10911 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 24 |

| CCND1 | P24864 | Cyclin D1 | 22 |

| HMOX1 | P09601 | Heme oxygenase 1 | 21 |

| STAT1 | P42224 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | 21 |

| APP | P05067 | Amyloid beta precursor protein | 21 |

| VEGF2 | P35968 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | 20 |

| PTEN | P60484 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | 20 |

| CRP | P02741 | C-reactive protein | 20 |

| SELE | Q5TI75 | Selectin E | 18 |

| F2 | P16930 | Coagulation factor II, thrombin | 17 |

| HIF1A | P01892 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha | 17 |

| SOD1 | P00441 | Superoxide dismutase 1 | 17 |

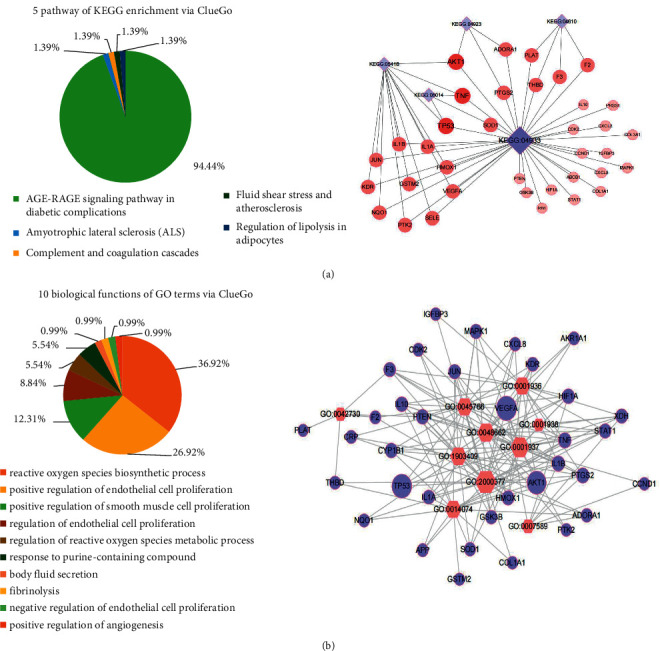

3.4. Results of Enrichment Analysis about Candidate Targets

A total of five signaling pathways (Figure 4(a)) and 10 biological functions (P < 0.05, Figure 4(b)) involving in QUE protecting against podocyte injury were obtained via ClueGO, respectively. Detailed information of ClueGO enrichment results is listed in Table 2. 118 signaling pathways (P < 0.05, Supplementary Table 6) and 52 biological functions (P < 0.05, Supplementary Table 7) were obtained via R project, respectively. The top 20 signaling pathways with low P values are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

The enrichment results of KEGG (a) and GO terms analysis (b) for the 41 candidate targets via ClueGO. The AGE-RAGE signaling pathway is the most reliable pathway in ClueGO (94.44%), regulation of reactive oxygen metabolism (36.92%) and endothelial cell proliferation (26.92%) are top two reliable biological functions.

Table 2.

KEGG (A) and GO (B) term enrichment results from ClueGO.

| ID | Description | Percentage | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| KEGG: 04933 | AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 94.44% | 36 |

| KEGG: 05418 | Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis | 1.39% | 15 |

| KEGG: 04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 1.39% | 4 |

| KEGG: 05014 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 1.39% | 3 |

| KEGG: 04923 | Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes | 1.39% | 3 |

|

| |||

| B | |||

| GO: 1903409 | Reactive oxygen species biosynthetic process | 36.92% | 18 |

| GO: 0001937 | Positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation | 26.92% | 24 |

| GO: 0048662 | Positive regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation | 12.31% | 20 |

| GO: 0001936 | Regulation of endothelial cell proliferation | 8.84% | 17 |

| GO: 2000377 | Regulation of reactive oxygen species metabolic process | 5.34% | 31 |

| GO: 0014074 | Response to purine-containing compound | 5.34% | 17 |

| GO: 0045766 | Positive regulation of angiogenesis | 2% | 17 |

| GO: 0007589 | Body fluid secretion | 2% | 6 |

| GO: 0042730 | Fibrinolysis | 2% | 5 |

| GO: 0001937 | Negative regulation of endothelial cell proliferation | 2% | 3 |

Figure 5.

Enrichment results of KEGG (a) and ClueGO (b) from R project. The AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (P=3.655 × 10−19; count = 15) is also the most reliable pathway R project.

The top pathway obtained in ClueGO (accounting for 94.44%) and R project (P=3.655 × 10−19; count = 15) both was the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications that was also identified as the major signaling pathway of QUE protecting against podocyte injury in DN. Oxidoreductase activity, antioxidant activity, and peroxidase activity from R project were consistent with the regulation of reactive oxygen metabolism (36.92%) from ClueGO [47], and growth factors, cytokine receptors, and protein phosphatase 2A from R project were consistent with endothelial cell proliferation (26.92%) from ClueGO [48].

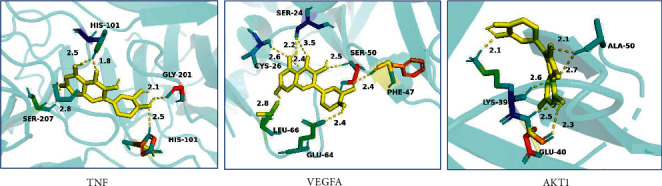

3.5. Results of Molecular Docking

The molecular docking analysis showed that QUE (ZINC3869685) could easily enter and bind to the key target TNF (2JG9), VEGFA (1MKK), and AKT1 (1UNR) with several interactions, hydrogen bonds, and amino acid residues, shown in Figure 6. QUE can form five H-bonds with GLY-201 (2.1), HIS-101 (2.5), SER-207 (2.8), and HIS-101 (2.5 and 1.8) of TNF, eight H-bonds with LEU-66 (2.8), CYS-26 (2.6 and 2.4), GLU-64 (2.4), PHE-47 (2.4), SER-50 (2.5), and SER-24 (2.2 and 3.5) of VEGFA. And, the binding energy of QUE and TNF, VEGFA and AKT1 were −6.35 kJ/mol, −6.75 kJ/mol, and −5.36 kJ/mol, respectively.

Figure 6.

3D molecular binding model of QUE to key targets TNF, VEGFA, and AKT1. Three key targets are represented as light blue flat strips, and amino acid residues of key targets are represented as colored sticks and QUE is represented as the yellow stick. The yellow dashed lines demarcate hydrogen bonds, and the interaction distances are indicated next to the bonds.

4. Discussion

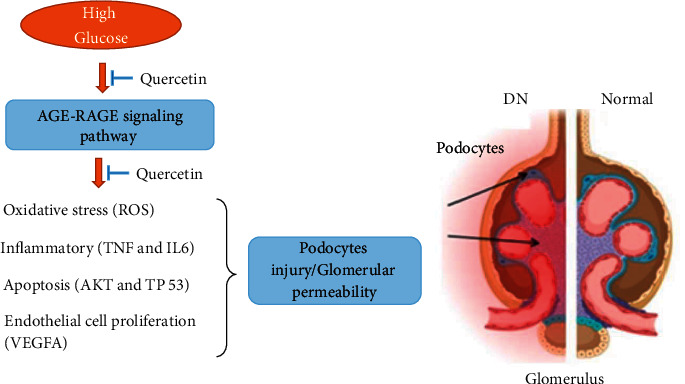

The present study shows that QUE would protect against podocyte injury in DN mainly by regulating the major AGE-RAGE signaling pathway and three key targets: TNF mediating the proinflammatory, VEGF promoting vascular permeability and proliferation, and AKT1 participating in apoptosis. Furthermore, QUE, having the five hydroxy groups (placed at the 3-, 3′-, 4′-, 5- and 7-positions), should have suitable binding sites with three key targets and interacts with amino acid residues of targets through multiple hydrogen bonding and Van der Waals using molecular docking analysis.

QUE regulates the oxidative stress-associated AGE-RAGE signaling pathway to protect against podocyte injury in DN. It is known that the binding of AGEs to the receptor RAGE can induce oxidative stress and inflammation, eliciting podocyte injuries [49, 50]. Encouragingly, Li et al. validated that QUE can reduce the production of AGEs by trapping 50.5% of glyoxal and 80.1% of methylglyoxal which are the crucial reactive dicarbonyl precursors of AGEs [51]. Moreover, QUE decreases the expression of RAGE [52] and increases the expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) to suppress oxidative stress accelerated by the activated AGE-RAGE pathway, protecting the cell from injury [53]. Additionally, QUE is an antioxidant, it can not only increase the expression of podocyte slit diaphragms and sensitive markers of podocyte nephrin and podocin to the maintenance of the skeletal structure and function of podocytes [23, 54] but also lower the kidney hypertrophy index (KI), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and blood creatinine (Scr) to improve kidney function in diabetic rats [52]. Therefore, it can be inferred that QUE can prevent podocytes from the stimulation of oxidative stress by inhibiting HG which induced excessive accumulation of AGEs, lowering ROS synthesis. Furthermore, accumulating evidence has also shown there is a close relation between the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway and other complications of diabetes such as diabetic peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy [55–57]. Therefore, QUE might also have preventive effects on complications of diabetes.

QUE inhibits key targets of TNF mediating the proinflammatory and regulates VEGF promoting vascular permeability and AKT mediating apoptosis to protect podocytes from injury in DN. Experiments in the streptozocin-induced diabetic rat have demonstrated that the inflammatory cytokine of TNF-α, a member of the TNF receptors superfamily, is an intermediate factor for excessive ROS-induced podocyte injury and apoptosis [58–60]. Moreover, TNF-α plays a predictive role in DN, attributing to its involvement in the onset and progression of DN [61]. Encouragingly, QUE has been proven to decrease the renal TNF-α and ROS synthesis [62] induced by high homocysteine (Hcy) [63] which is an independent risk factor for DN [64]. High Hcy can also directly cause podocyte injury, with subsequent progression of glomerular permeability induced by oxidative stress [64, 65], and can affect the function of renal endothelium and mesangial cells during the progression of DN [66, 67]. While, as DN progresses further, abnormal elevation of Hcy directly damages vascular endothelial cells and aggravates microalbuminuria and ultimately forms a vicious circle between DN and Hcy [65, 68]. Interestingly, QUE can also reduce the level of Hcy and increase the level of the Hcy's metabolite, taurine, an antioxidant that has been demonstrated to improve glomerular sclerosis and attenuate the progression of DN in mice [69, 70]. Metabolomic studies have consistently shown that QUE increases the level of taurine in mice serum and urine [70, 71]. Treatment with taurine significantly downregulates the protein levels of podocyte homeostasis regulator and consequently the reduction of glucose-induced podocytes injuries in DN mice model [72]. Furthermore, high Hcy-induced endothelial cell apoptosis is commonly associated with increased VEGF [73]. VEGF is the important mediator in endothelial cell proliferation and glomerular mesangial proliferation at the end-stage of DN [74]. It is regulated by candidate target ERK1/2 (also known as MAPK1, degree = 24) and key target AKT (degree = 31), and the excessive production of VEGF subtype A (VEGFA), resulting from the interaction of AGEs and RAGE, is a novel risk factor in the pathogenesis of the endstage renal disease [55, 75]. But excessive inhibition of VEGF causes glomerular injury with prominent podocyte injury [76, 77]. So, it would be speculated that the therapeutic index of VEGF for podocyte injury is narrow, which is in line with the statements of Oe et al. [78]. Interestingly, QUE can moderately regulate the expressions of VEGFA and alleviate podocyte injury and kidney function in diabetic rats [23]. Hence, QUE is a new appropriate product that targeted VEGFA to ameliorate podocyte injury. The phosphorylation of another key target AKT can significantly prevent from podocyte apoptosis, foot process shrinkage, and renin loss [78]. However, the levels of phospho-Akt are downregulated by long-term HG, causing the increased activation of p38 MAPK and renal proximal tubule cell apoptosis [79]. Noteworthily, QUE can increase the phosphorylation of AKT to promote the synthesis of liver glycogen with lowering blood sugar and regulate the downstream proteins of AKT to facilitate lipid metabolism [80]. Thus, it can be assumed that QUE promotes glycogen synthesis via AKT phosphorylation to prevent podocytes from injury. In addition, QUE inhibits the expression of candidate target TP53 being a key regulator of p53 apoptotic signaling pathways which are involved in podocyte senescence and apoptosis [80, 81], and the downstream signaling pathways of TP53, such as NF-kB signaling pathways, that participate in HG-induced podocyte injury [82, 83].

Moreover, this study also indicates that QUE protects against podocytes injury having relation with autophagy from enrichment analysis (P=0.0048 from the R project). Autophagy, which can accelerate the metabolism of ROS induced by HG, significantly accelerates the metabolism of ROS and inhibits the activation of VEGF, showing its importance to maintain the postmitotic podocytes cells [84, 85]. More and more researches prove that QUE can suppress ROS synthesis through induction of autophagy to cure liver fibrosis and CVD [86–88]. Additionally, QUE can significantly upregulate autophagy by suppressing oxidative stress and downregulating TNF-α and AKT and ameliorating doxorubicin-induced podocyte injury in rats [89, 90]. Thus, it can be hypothesized that QUE may act on autophagy associated with the reduction of ROS to participate in the protection of podocytes injury [91, 92].

Although it has been confirmed in different experimental models that QUE regulates key targets at TNF, VEGFA, and AKT1, as well as the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway to protect against podocyte injury. In this article, the findings suggest that the multipronged therapeutic effect of QUE on podocyte injury, attributing to its synergistic effects on these multiple targets. However, further experimental studies will be needed to verify it.

5. Conclusion

This study reveals that QUE can reduce the inflammatory response (TNF and IL6), inhibit endothelial cell proliferation (VEGFA) and apoptosis of podocytes (AKT1 and TP53), and suppress the AGE-induced oxidative stress by regulating the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway activated by HG to protect against podocytes injury in DN (Figure 7). This study provides a scientific basis for developing QUE as a potential natural medicine for the treatment of DN.

Figure 7.

Effects of QUE protecting against podocytes injury in DN via key targets TNF, VEGFA, and AKT1 in AGE-RAGE signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the key scientific research projects of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (no. 17401901100) and Science and Technology Innovation Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health (no. ZYKC201701007).

Contributor Information

Jingjing Huang, Email: huangjingjing0112@163.com.

Wanhua Yang, Email: yangwanhuaxy@163.com.

Data Availability

The data of this research is obtained through authoritative online databases and software analysis and can be acquired from the Supplementary Materials uploaded with this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Chenxia Hao contributed to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: 355 targets of QUE. Supplementary Table 2: 4895 human genes related to DN. Supplementary Table 3: 848 human genes associated with podocyte injury. Supplementary Table 4: 42 mapping targets. Supplementary Table 5: specific analytical parameters of 41 candidate targets. Supplementary Table 6: 118 signaling pathways from R project. Supplementary Table 7: 52 biological functions from R project.

References

- 1.Li Y., Sui X., Hu X., Hu Z. Overexpression of KLF5 inhibits puromycin induced apoptosis of podocytes. Molecular Medicine Reports . 2018;18:3843–3849. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou D., Zhou M., Wang Z., et al. PGRN acts as a novel regulator of mitochondrial homeostasis by facilitating mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis to prevent podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Death & Disease . 2019;10(7):p. 524. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1754-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gnudi L., Coward R. J. M., Long D. A. Diabetic nephropathy: perspective on novel molecular mechanisms. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism . 2016;27(11):820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kravets I., Mallipattu S. K. The role of podocytes and podocyte-associated biomarkers in diagnosis and treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Journal of the Endocrine Society . 2020;4 doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa029.bvaa029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang H., Xie T., Li D., et al. Tim-3 aggravates podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy by promoting macrophage activation via the NF-κB/TNF-α pathway. Molecular Metabolism . 2019;23:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu C., Sun L., Xiao L., et al. Insights into the mechanisms involved in the expression and regulation of extracellular matrix proteins in diabetic nephropathy. Current Medicinal Chemistry . 2015;22(24):2858–2870. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150625095407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp J. B., Anders H. J., Susztak K., et al. Podocytopathies. Nature Reviews Disease Primers . 2020;6(1):p. 68. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y., Hao Y., Li H., et al. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis of differentiated mouse podocytes induced by high glucose. International Journal of Molecular Medicine . 2014;33(4):809–816. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X. Y., Mi Y., Wang C. l. Podocyte injury and diabetic nephropathy. Chinese Journal of Nephrology, Dialysis & Transplantation . 2019;28:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X., Li F., Sun W., et al. Extracts of magnolia species-induced prevention of diabetic complications: a brief review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2016;17(10):p. 1629. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondeva T., Wolf G. Role of neuropilin-1 in diabetic nephropathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine . 2015;4(6):1293–1311. doi: 10.3390/jcm4061293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S., Wang D. J., Xue N., et al. Nicousamide protects kidney podocyte by inhibiting the TGFβ receptor II phosphorylation and AGE-RAGE signaling. American Journal of Translational Research . 2017;9:115–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L. Study on the mechanism of diabetic podocyte injury and the treatment of Chinese and Western medicines. Diabetes New World . 2014;34:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H. Y., Chen J. Q., Li J. Y., et al. Deep learning and random forest approach for finding the optimal traditional Chinese medicine formula for treatment of alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling . 2019;59(4):1605–1623. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghimire B. K., Seo J. W., Yu C. Y., Kim S. H., Chung I. M. Comparative study on seed characteristics, antioxidant activity, and total phenolic and flavonoid contents in accessions of sorghum bicolor (L.) moench. Molecules . 2021;26(13):p. 3964. doi: 10.3390/molecules26133964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes I. B. S., Porto M. L., Santos M. C. L. F. S., et al. Renoprotective, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic effects of oral low-dose quercetin in the C57BL/6J model of diabetic nephropathy. Lipids in Health and Disease . 2014;13:p. 184. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q., Ye Q., Huang X., et al. Revealing active components, action targets and molecular mechanism of Gandi capsule for treating diabetic nephropathy based on network pharmacology strategy. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies . 2020;20(1):p. 362. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granados-Pineda J., Uribe-Uribe N., Garcia-Lopez P., Ramos-Godinez M., Rivero-Cruz J., Perez-Rojas J. Effect of pinocembrin isolated from Mexican Brown propolis on diabetic nephropathy. Molecules . 2018;23(4):p. 852. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding T., Wang S., Zhang X., et al. Kidney protection effects of dihydroquercetin on diabetic nephropathy through suppressing ROS and NLRP3 inflammasome. Phytomedicine . 2018;41:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer A. K., Xu M., Zhu Y., et al. Targeting senescent cells alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. Aging Cell . 2019;18 doi: 10.1111/acel.12950.e12950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickson L. J., Langhi Prata L. G. P., Bobart S. A., et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine . 2019;47:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta C., Prakash D. Nutraceuticals for geriatrics. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine . 2015;5(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y. l., Qu Z. H., Yang P. P., Yuan B. Y., Chen L. B. Effects of quercetin on the expression of nephrin and podocin in kidney pods of diabetic rats. Chinese Journal of Laboratory Diagnosis JST . 2019;23:519–522. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao W., Yuan Y., Zhao H., Han Y., Chen X. Aqueous extract of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge-Radix Puerariae herb pair ameliorates diabetic vascular injury by inhibiting oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology . 2019;129:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhai R., Jian G., Chen T., et al. Astragalus membranaceus and panax notoginseng, the novel renoprotective compound, synergistically protect against podocyte injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Diabetes Research . 2019;2019:14. doi: 10.1155/2019/1602892.1602892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R., Zhu X., Bai H., Ning K. Network pharmacology databases for traditional Chinese medicine: review and assessment. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2019;10:p. 123. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics . 2014;6(1):p. 13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. Swiss target prediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research . 2019;47(W1):W357–W364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gfeller D., Michielin O., Zoete V. Shaping the interaction landscape of bioactive molecules. Bioinformatics . 2013;29(23):3073–3079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y., Zhang F., Yang K., et al. SymMap: an integrative database of traditional Chinese medicine enhanced by symptom mapping. Nucleic Acids Research . 2019;47(D1):D1110–D1117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amberger J. S., Hamosh A. Searching online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM): a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic phenotypes. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics . 2017;58:1 2 1–2 12. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wishart D. S., Feunang Y. D., Guo A. C., et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Research . 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Tanabe M., Sato Y., Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Research . 2017;45(D1):D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y. H., Yu C. Y., Li X. X., et al. Therapeutic target database update 2018: enriched resource for facilitating bench-to-clinic research of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Research . 2018;46(D1):D1121–D1127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stelzer G., Rosen N., Plaschkes I., et al. The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics . 2016;54:1–13. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J., So S., Lee H. J., Park J. C. DigSee: disease gene search engine with evidence sentences (version cancer) Nucleic Acids Research . 2013;41(W1):W510–W517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clough E., Barrett T. The gene expression Omnibus database. Methods in Molecular Biology . 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichii O., Otsuka-Kanazawa S., Nakamura T., et al. Podocyte injury caused by indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin and aryl-hydrocarbon receptor ligand. PLoS One . 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108448.e108448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie M. E., Phipson B., Wu D., et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Research . 2015;43(7):p. e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szklarczyk D., Morris J. H., Cook H., et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Research . 2017;45(D1):D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Parys T., Melckenbeeck I., Houbraken M., et al. A Cytoscape app for motif enumeration with ISMAGS. Bioinformatics . 2017;33:461–463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics . 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature Genetics . 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma X., Yu M., Hao C., Yang W. Identifying synergistic mechanisms of multiple ingredients in shuangbai tablets against proteinuria by virtual screening and a network pharmacology approach. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:15. doi: 10.1155/2020/1027271.1027271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bikadi Z., Hazai E. Application of the PM6 semi-empirical method to modeling proteins enhances docking accuracy of AutoDock. Journal of Cheminformatics . 2009;1:p. 15. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seeliger D., de Groot B. L. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design . 2010;24(5):417–422. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9352-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galehdari H., Azarshin S. Z., Bijanzadeh M., Shafiei M. Polymorphism studies on microRNA targetome of thalassemia. Bioinformation . 2018;14(5):252–258. doi: 10.6026/97320630014252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janet L., Douglas J. K. G., Moses A. V., Dezube B. J., Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis: a triad of viral infection, oncogenesis and chronic inflammation. Translational Biomedicine . 2012;1:p. 172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frédérick R., Pochet L., De Tullio P., Dufrasne F. 31ièmes journées franco-belges de pharmacochimie: meeting report. Pharmaceuticals . 2017;10(4) doi: 10.3390/ph10040094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto Y., Yamamoto H. Interaction of receptor for advanced glycation end products with advanced oxidation protein products induces podocyte injury. Kidney International . 2012;82(7):733–735. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X., Zheng T., Sang S., Lv L. Quercetin inhibits advanced glycation end product formation by trapping methylglyoxal and glyoxal. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 2014;62(50):12152–12158. doi: 10.1021/jf504132x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang L. X., Zhu K. M., Li D. P., Gu S. M. Effects of quercetin linosomes on the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) in kidney of diabetic rats. Tianjin Medical Journal . 2016;44:71–74+132. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J. l., Yang Z. C., Wang C., Sun F., Xu X. H. The hypoglycemic effect and mechanism of quercetin for diabetic rats. Jining Medical University . 2018;42:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin W., Xu Z., Lu Y., et al. Mixed organic solvents induce renal injury in rats. PLoS One . 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045873.e45873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamagishi S. I, Matsui T., Nakamura K., et al. Olmesartan blocks advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-induced angiogenesis in vitro by suppressing receptor for AGEs (RAGE) expression. Microvascular Research . 2008;75(1):130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramasamy R., Yan S. F., Schmidt A. M. Receptor for AGE (RAGE): signaling mechanisms in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences . 2011;1243(1):88–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi G. J., Li Y., Cao Q. H., et al. In vitro and in vivo evidence that quercetin protects against diabetes and its complications: a systematic review of the literature. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2019;109:1085–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu M. X., Qin Y. T., Ge C. X., et al. Activated iRhom2 drives prolonged PM2.5 exposure-triggered renal injury in Nrf2-defective mice. Nanotoxicology . 2018;12(9):1045–1067. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2018.1513093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mudyanadzo T. A. Endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular correlates. Cureus . 2018;10 doi: 10.7759/cureus.3342.e3342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J., Liu B., Xue H., Zhou Q. Q., Peng L. miR-217 is a useful diagnostic biomarker and regulates human podocyte cells apoptosis via targeting TNFSF11 in membranous nephropathy. BioMed Research International . 2017;2017:9. doi: 10.1155/2017/2168767.2168767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uwaezuoke S. N. The role of novel biomarkers in predicting diabetic nephropathy: a review. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease . 2017;10:221–231. doi: 10.2147/ijnrd.s143186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H. Y., Zhao J. G., Wei Z. G., Zhang Y.-Q. The renal protection of flavonoid-rich ethanolic extract from silkworm green cocoon involves in inhibiting TNF-α-p38 MAP kinase signalling pathway in type 2 diabetic mice. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2019;118 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109379.109379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin X., Meng X., Song Z. Homocysteine and psoriasis. Bioscience Reports . 2019;39(11) doi: 10.1042/bsr20190867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang R., Wang X., Gao Q., et al. Taurine supplementation reverses diabetes-induced podocytes injury via modulation of the CSE/TRPC6 axis and improvement of mitochondrial function. Nephron . 2020;144(2):84–95. doi: 10.1159/000503832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang J., Li J., Chen S., et al. Modification of platelet count on the association between homocysteine and blood pressure: a moderation analysis in Chinese hypertensive patients. International Journal of Hypertension . 2020;2020:8. doi: 10.1155/2020/5983574.5983574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu J., Yue S., Geng J., et al. Relationship between diabetic retinopathy and subclinical hypothyroidism: a meta-analysis. Scientific Reports . 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1038/srep12212.12212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jahangir E., Vita J. A., Handy D., et al. The effect of L-arginine and creatine on vascular function and homocysteine metabolism. Vascular Medicine . 2009;14(3):239–248. doi: 10.1177/1358863x08100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guan H., Xia M. D., Wang M., Guan Y. J., Lyu X. C. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genetic polymorphism and the risk of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2020;99(35) doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000021558.e21558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oyenihi A. B., Ayeleso A. O., Mukwevho E., Masola B. Antioxidant strategies in the management of diabetic neuropathy. BioMed Research International . 2015;2015:15. doi: 10.1155/2015/515042.515042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang L., Dong M., Guangyong X., Yuan T., Tang H., Wang Y. Metabolomics reveals that dietary ferulic acid and quercetin modulate metabolic homeostasis in rats. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 2018;66(7):1723–1731. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu C. Quercetin and Isorhamnetin from Metabolism Distribution in Mice Plasma and Tissues after Long Term Administration . Nanchang, China: Nanchang University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ngowi E. E., Sarfraz M., Afzal A., et al. Roles of hydrogen sulfide donors in common kidney diseases. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.564281.564281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tawfik A., Mohamed R., Elsherbiny N. M., DeAngelis M., Bartoli M., Al-Shabrawey M. Homocysteine: a potential biomarker for diabetic retinopathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine . 2019;8(1):p. 121. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alam-Faruque Y., Hill D. P., Dimmer E. C., et al. Representing kidney development using the gene ontology. PLoS One . 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099864.e99864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prasad K., Dhar I., Zhou Q., Elmoselhi H., Shoker M., Shoker A. AGEs/sRAGE, a novel risk factor in the pathogenesis of end-stage renal disease. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry . 2016;423(1-2):105–114. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2829-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eremina V., Quaggin S. E. The role of VEGF-A in glomerular development and function. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension . 2004;13(1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xiao H., Shi W., Liu S., et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) prevents puromycin aminonucleoside-induced apoptosis of glomerular podocytes by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-signaling pathway. American Journal of Nephrology . 2009;30(1):34–43. doi: 10.1159/000200769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oe Y., Fushima T., Sato E., et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 protects against VEGF inhibitor-induced glomerular endothelial and podocyte injury. Scientific Reports . 2019;9(1):p. 2986. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39914-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J., Yu G. A systems biology approach to characterize biomarkers for blood stasis syndrome of unstable Angina patients by integrating MicroRNA and messenger RNA expression profiling. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2013;2013:21. doi: 10.1155/2013/510208.510208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peng J., Li Q., Li K., et al. Quercetin improves glucose and lipid metabolism of diabetic rats: involvement of akt signaling and SIRT1. Journal of Diabetes Research . 2017;2017:10. doi: 10.1155/2017/3417306.3417306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leiserson M. D. M., Blokh D., Sharan R., Raphael B. J. Simultaneous identification of multiple driver pathways in cancer. PLoS Computational Biology . 2013;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003054.e1003054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen Y., Liu Q., Shan Z., et al. The protective effect and mechanism of catalpol on high glucose-induced podocyte injury. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2019;19(1):p. 244. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roy S., Banerjee S., Chakraborty T. Vanadium quercetin complex attenuates mammary cancer by regulating the P53, Akt/mTOR pathway and downregulates cellular proliferation correlated with increased apoptotic events. Biometals . 2018;31(4):647–671. doi: 10.1007/s10534-018-0117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ding Y., Choi M. E. Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. Journal of Endocrinology . 2015;224(1):R15–R30. doi: 10.1530/joe-14-0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miaomiao W., Chunhua L., Xiaochen Z., Xiaoniao C., Hongli L., Zhuo Y. Autophagy is involved in regulating vegf during high-glucose-induced podocyte injury. Molecular BioSystems . 2016;12(7):2202–2212. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00195e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cao H., Jia Q., Yan L., Chen C., Xing S., Shen D. Quercetin suppresses the progression of atherosclerosis by regulating MST1-mediated autophagy in ox-LDL-induced RAW264.7 macrophage foam cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2019;20(23):p. 6093. doi: 10.3390/ijms20236093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li X., Jin Q., Yao Q., et al. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates liver inflammation and fibrosis by regulating hepatic macrophages activation and polarization in mice. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2018;9:p. 72. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lagerweij T., Hiddingh L., Biesmans D., et al. A chemical screen for medulloblastoma identifies quercetin as a putative radiosensitizer. Oncotarget . 2016;7(24):35776–35788. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sato S., Norikura T., Mukai Y. Maternal quercetin intake during lactation attenuates renal inflammation and modulates autophagy flux in high-fructose-diet-fed female rat offspring exposed to maternal malnutrition. Food & Function . 2019;10(8):5018–5031. doi: 10.1039/c9fo01134j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khalil S. R., Mohammed A. T., Abd El-Fattah A. H., Zaglool A. W. Intermediate filament protein expression pattern and inflammatory response changes in kidneys of rats receiving doxorubicin chemotherapy and quercetin. Toxicology Letters . 2018;288:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tili E., Michaille J. J. Promiscuous effects of some phenolic natural products on inflammation at least in part arise from their ability to modulate the expression of global regulators, namely microRNAs. Molecules . 2016;21(9):p. 1263. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dutra L. A., Ferreira de Melo T. R. The paradigma of the interference in assays for natural products. Biochemistry & Pharmacology: Open Access . 2016;5(3) doi: 10.4172/2167-0501.1000e183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: 355 targets of QUE. Supplementary Table 2: 4895 human genes related to DN. Supplementary Table 3: 848 human genes associated with podocyte injury. Supplementary Table 4: 42 mapping targets. Supplementary Table 5: specific analytical parameters of 41 candidate targets. Supplementary Table 6: 118 signaling pathways from R project. Supplementary Table 7: 52 biological functions from R project.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this research is obtained through authoritative online databases and software analysis and can be acquired from the Supplementary Materials uploaded with this article.