Summary

Background

Longitudinal evidence for sociodemographic and clinic factors deviating risk for suicide and repetition following SH (self-harm) varied greatly.

Methods

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO was conducted from January 1st, 2010 to April 5th, 2022. Longitudinal studies focusing on examining associating factors for suicide and repetition following SH were included. PROSPERO registration CRD42021248695.

Findings

The present meta-analysis synthesized data from 62 studies published from Jan. 1st, 2010. The associating factors of SH repetition included female gender (RR, 95%CI: 1.11, 1.04–1.18, I2=82.8%), the elderly (compared with adolescents and young adults, RR, 95%CI: 0.67, 0.52–0.87, I2=86.3%), multiple episodes of SH (RR, 95%CI: 1.97, 1.51–2.57, I2=94.3%), diagnosis (RR, 95%CI: 1.60, 1.27–2.02, I2=92.7%) and treatment (RR, 95%CI: 1.59, 1.40–1.80, I2=93.3%) of psychiatric disorder. Male gender (RR, 95%CI: 2.03, 1.80–2.28, I2=83.8%), middle-aged adults (compared with adolescents and young adults, RR, 95%CI: 2.40, 1.87–3.08, I2=74.4%), the elderly (compared with adolescents and young adults, RR, 95%CI: 4.38, 2.98–6.44, I2=76.8%), physical illness (RR, 95%CI: 1.95, 1.56–2.43, I2=0), multiple episodes of SH (RR, 95%CI: 2.02, 1.58–2.58, I2=87.4%), diagnosis (RR, 95%CI: 2.13, 1.67–2.71, I2=90.9%) and treatment (RR, 95%CI: 1.36, 1.16–1.58, I2=58.6%) of psychiatric disorder were associated with increased risk of suicide following SH.

Interpretation

Due to the substantial heterogeneity for clinic factors of suicide and repetition following SH, these results need to be interpreted with caution. Clinics should pay more attention to the cases with SH repetition, especially with poor physical and psychiatric conditions.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [No: 82103954; 30972527; 81573233].

Keywords: Suicide, Self-harm, Repetition, Meta-analysis, Associating factors

Abbreviations: SH, Self-harm; SA, Suicide attempt; SP, Self-poisoning; SC, Self-cutting; CI, Confidence interval; RR, Risk ratio; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO was conducted to include longitudinal studies from January 2010 to April 2022 using search terms related to self-harm, repeated self-harm, suicide and cohort study.

Although few reviews summarized the associating factors of suicide and repetition following self-harm, meta-analyses for pooling the comprehensive associating sociodemographic and clinic factors of suicide and repetition following self-harm, especially for specific types of psychiatric disorders, are lacking. Additionally, longitudinal evidence for associating factors of suicide and repetition following self-harm varied greatly.

Added value of this study

This meta-analysis and systematic review include a quantitative synthesis for a range of associating factors of suicide and repetition following self-harm from longitudinal studies with large samples. It updates the evidence from early reviews with studies published in recent 10 years and adds to the literature by synchronizing the findings on the influence of specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders in the risk of suicide and repetition following self-harm. Specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders including mood disorder and psychotic disorder were associated with increased risk of suicide and repetition following self-harm. Besides, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, personality disorder, and eating disorder were associated with increased risk of self-harm repetition.

Implications of all available evidence

Strategies to address the associating factors could have some effects on intervention and prevention of subsequent self-harm and suicide. Implementing interventions such as regular follow-up of self-harm and valid treatment of psychiatric disorder should be considered. These insightful details found in this study could add some evidence for clinical care and self-harm prevention in the future.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Self-harm (SH) is an intentional act of self-poisoning and/or self-injury irrespective of motivation1 that induces huge burdens to economic costs2,3 and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide.4 Under this definition, suicide attempt, self-injury, parasuicide, and deliberate self-harm are also used to describe SH nomenclature.5,6 A history of SH not only implies an increased risk of recurrence,7,8 but also increases the risk for mortality by all causes,9,10 especially suicide.11 A recent meta-analysis summarizes that the prevalence of suicide and repetition following SH in one year is 1.3% and 17.0%, respectively.12 While SH repetition is more prevalent in female and young people, subsequent suicide is more prevalent in males and the elderly.12 A better understanding of factors deviating the risk for suicide and repetition following SH in the patients is vital for efforts to prevent such adverse outcomes.

Two published reviews, to our knowledge have reported the associating factors for SH repetition. A review from Larkin et al.13 included 129 studies up to June 2012 found that previous SH, personality disorder, hopelessness, history of psychiatric treatment, schizophrenia, alcohol and substance misuses, and living alone were associated with repetition of SH. Another systematic review synthesized 27 studies focusing on adolescents and found psychiatric morbidity, features of previous SH, psychological distress, alcohol misuse, poor family, peer relationships, age, gender, and ethnicity being related to SH repetition.6 However, neither of the two reviews conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the strength of these associations.

About associating factors for suicide following SH, a systematic review and meta-analysis included 12 prospective studies up to February 2014 and found previous episodes of SH, suicidal intent, physical health problems and male gender were highly related to eventually suicide.14 This study also pooled the risk scales of Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) and the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) for suicide following SH. Although this review also pooled the estimates of psychiatric history, specific diagnosis of psychiatric disorder such as psychotic disorder, mood disorder and treatment of psychiatric disorder were not included for consideration; and the limited number of included studies affect the extrapolation of the conclusions.

There was also a review on associating factors for suicide and repetition following suicide attempt,15 that searched for the studies between January 1991 to December 2009 and included 76 studies. This review identified important predictors of SH repetition that included previous attempt, being a victim of sexual abuse, poor global functioning, having a psychiatric disorder, being on psychiatric treatment, depression, anxiety, and alcohol abuse or dependence and the strongest predictors of suicide following SH were older age, suicide ideation, and history of suicide attempt. However, this review included case-control and cross-sectional studies and lacked longitudinal evidence and pooled results of associating factors.

Despite of these reviews summarizing the associating factors with data from different time periods, meta-analysis on longitudinal evidence is needed to document associating sociodemographic and clinic factors on risk for suicide and repetition following SH in the general population. There is also a need to explore whether the estimates on the longitudinal association between associating factors and subsequent suicide and repetition following SH have varied by the used model, time of follow-up, sample size, definition of SH, and risk of bias. Considering the effect of time of follow-up on the associating factors and the review performed by Beghi et al.15 to include studies between January 1991 and December 2009, this systematic review and meta-analysis included the longitudinal studies published in recent 10 years (from January 2010 to April 2022), with the aims: i) to identify the sociodemographic and clinic factors of suicide and repetition following SH; ii) to explore the effect of the specific diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders on suicide and repetition following SH; iii) to examine the effect of the used model, time of follow-up, sample size, definition of SH, and risk of bias on the pooled estimates; iv) compare the pooled results with previous reviews.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021248695). The databases used to search original studies included PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. Detailed search strategy could be found in the Supplementary material 1. Briefly, primary search terms included: (“attempted suicide” OR “deliberate self-harm” OR “self-harm” OR “self-injury” OR “self-poisoning”) and (“repeated self-harm” OR “suicide”) and (“cohort study” OR “population-based study” OR “follow-up”). Two investigators (YKY and XL) independently identified relevant studies published from January 1st, 2010, to April 5th, 2022, and compared with others until sorting out consistent records. The references of included studies and systematic reviews were also checked to identify additional studies that were not captured by our searching strategies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis met the following criteria: (1) had longitudinal data with a design of prospective or retrospective cohort study enabling calculation of the effect of associating factors on subsequent repetition and suicide following SH; (2) original research studies published in English (excluding case report, editorial comments, conference studies, randomized controlled trials, reviews, unpublished studies or doctoral theses); (3) had a clear definition of SH for the study participants and had SH repetition or suicide following SH as primary outcomes, which were recorded by the specific system or cohort for self-harm/death; (4) reported associating factors of suicide and repetition following SH with effect size (odds ratio, risk ratio, hazards ratio) and 95% confidence interval or raw data with cross tables.

Studies were excluded if they aimed to study specific population such as single gender, veterans, or limited age groups, namely the studies focusing on the adolescents, the elderly and the middle-age population. Besides, included studies with sample size less than 100 were excluded in consideration of low incidence of outcomes and unstable results in these studies. For studies using the same database, only the one with the largest sample size was included. The studies reporting associating factors of suicide and repetition following SH using the data of presentation or episode of SH, which might have internal correlation for the same case, were excluded in consideration of intraclass correlation. The studies with cross-sectional design were excluded to get longitudinal estimates.

Data extraction

Extracted information included the name of first author, country or area, publication year, follow-up time, definition of SH (including self-harm, suicide attempt, self-poisoning or self-cutting under the definition of SH by Hawton1), primary outcomes (suicide or repetition following SH, respectively), age range for included population, sample size, models (crude or adjusted model) used to report the associating factors and odds ratio/risk ratio/hazards ratio with 95%CI for included factors. Two researchers (BPL and YYZ) extracted information separately and discussed the discrepancies.

Consistent follow-up time was recorded for the cohort with no censored data. Range, mean or median time of follow-up was recorded for cohort with censored and survival data. In order to explore the associations between pooled associating factors and follow-up time, mean or median time of follow-up was used to represent the concentration. For the studies only providing period of time, the result from sum of maximum and minimum time divided by two was used to represent the concentration of follow-up time. Long-term follow-up time was above 1 year for SH repetition and above 3.5 year for suicide following SH after calculating the median of follow-up time for all included studies. The sample size after taking the natural logarithm was used to analyze the associations with pooled associating factors owing to big differences for included studies.

Learning from previous reviews and reports from included studies (only associating factors recorded in above two studies were included), sociodemographic factors such as age group, gender, employment, marital status, and educational level, and clinical factors such as multiple episodes of SH, physical illness, diagnosis, and treatment of psychiatric disorder were extracted for this review as the primary associating factor. Specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorder were extracted under the criteria of Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Disorders (SCID, 2002 Edition).16 Specific treatment of psychiatric disorder including psychiatric clinic and hospitalization were also extracted from included studies. Due to varying cut-offs of age groups (cut-off age of adolescents and younger adults and middle-aged adults: from 20 years to 34 years and cut-off age of middle-aged adults and the elderly: from 50 years to 65 years) among included studies, a somewhat flexible cutting point of age with clinical significances for dividing the lifespan into the adolescents and young adults, middle-aged adults, and the elderly was adopted when pooling the estimates related to age groups.

Quality assessment of the included studies

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of included studies.17 NOS included 8 items assessing the selection (4 items, 4 points), comparability (1 item, 2 points), and outcomes (3 items, 3 points) of every included study with the total scores of 9 points. A total score of 9 points for included studies were deemed to have a low risk of bias. The studies with two or three points for selection, one for comparability, and two for outcomes were considered to have medium risk of bias. The studies scored of zero or one point for selection or outcomes, and zero point for comparability were deemed to have a high risk of bias.18 Besides, a total score lower than 6 points for included studies were also deemed to have a high risk of bias in this meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

The pooled associating factors for suicide and repetition following SH were performed using R version 3.6.4. OR/HR used in cohort studies was considered as RR in this meta-analysis. Adjusted RRs and their 95%CIs reported in these included studies were prioritized. Crude RRs and 95%CIs were also used if adjusted estimates were not available. Considering some studies only reported indexes from different subgroups such as age group, gender, specific psychiatric disorder and so on, the overall effect for each study was calculated based on heterogeneity between subgroups. Heterogeneity was tested with I2 statistics19 in this study. Random effect model (REM) with Dersimonian and Laird method was used to calculate the estimates.20 Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the risk of suicide and SH repetition for definition of SH, namely self-harm, self-poisoning, self-cutting and suicide attempt, and follow-up time for associating factors. Subgroup analyses of the specific diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorder were not performed because of limit number of include studies. Meta-regression was also performed to examine the potential sources of heterogeneity between studies according to sample and study characteristics such as risk of bias, sample size, adopted model, follow-up time, and definition of SH. To examine the stability of the pooled results, sensitivity analysis by leave-one-out methods (i.e., exclusion of one study at a time) was performed.21 Sensitivity analysis was also performed by omitting low-quality studies and to observe the effect by study quality . Begg's test22 and Egger's test23 were used to examine publication bias. Funnel plot was also used to detect publication bias. If existing publication bias, trim-and-fill method was used to detect the stability of pooled results.24 All the analyses were two-sided and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or in the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript, had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Literature search and characteristics of included studies

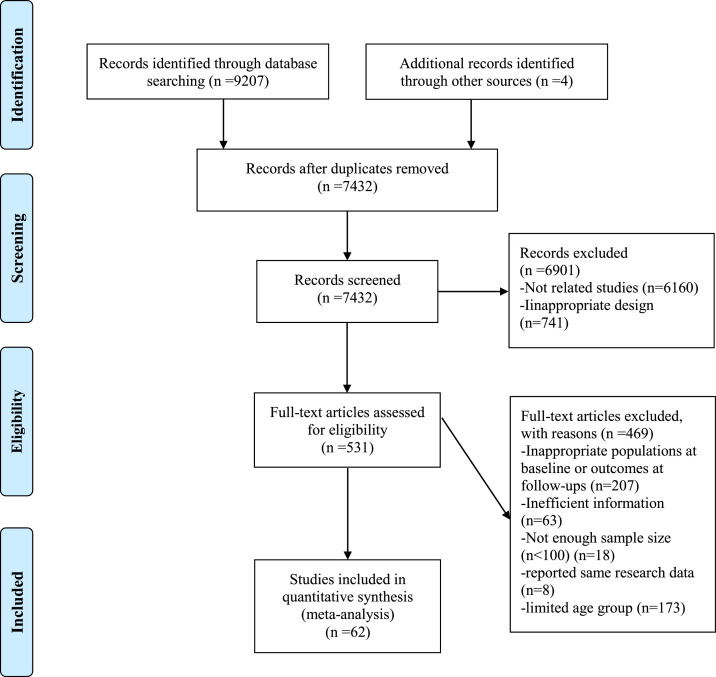

Following search strategies shown in the Supplementary material 1, 9211 studies were identified, and 62 longitudinal studies were eventually included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The flow diagram for including studies could be seen in the Figure 1. Of the included studies, 32 studies reported the associating factors of SH repetition,7,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 21 studies reported the associating factors of suicide following SH,11,56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 and 9 studies both reported the associating factors of suicide and repetition following SH.8,76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 For the definition of participants, 31 studies adopted SH, 26 studies adopted suicide attempt (SA), 4 adopted self-poisoning (SP) and 1 adopted self-cutting (SC). A total of 34 studies were based on data from Europe (UK 9, Sweden 8, and the others from Denmark, Norway, France, Italy, Spain, Ireland), 19 from Asia (Taiwan, China 13, and the others from Japan, Sri Lanka, mainland China and Japan), and 9 from America (USA 6 and Canada 3). The sample size of included studies was from 160 to 136,451. The item-based quality assessment by NOS for each included studies could be seen in the Supplementary material 2 and the risk of bias could be seen in the Table 1. Most of included studies scored 7 points or above (30/41) for SH repetition and (27/30) for suicide following SH associated with NOS. The number of included studies with low, medium, and high risk of bias were 2, 33, and 6 for SH repetition and 17, 10, and 3 for suicide following SH, respectively. The proportion of the males was from 22.9% to 54.0% in the studies of SH repetition and 25.0% to 49.7% in the studies of suicide following SH. More details of characteristics about included studies could be seen in the Table 1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram showing process of study selection for inclusion in our meta-analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies and assessment of risk of bias.

| First author (year of publishment) | Country or region | Follow-up time (Mean or Median or range) | Outcomes | Age range | Male (%) | Sample size | Included factors | Assessment of risk of bias using NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of SH: SH | ||||||||

| Bergen (2010) | UK | 0–2 years | SH | Median: 30 years (IQR: 19 years) | 41.8 | 13,966 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: history of SH, and treatment of psychiatric disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Bergen (2012) | UK | 3–11 years | Suicide | Median: 27 years (IQR: 19 years) | 35.0 | 30,202 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and employment. Clinical factors: history of SH and treatment of psychiatric disorder. |

Low risk |

| Bhaskaran (2014) | Canada | 0.5 years (At least 0.5 years for all cases) | SH | 18 years or above | 45.1 | 922 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: substance use disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Bilen (2011) | Sweden | 0–3 years | SH | 18 years or above | 35.0 | 1524 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, marital status, employment, and educational level. Clinical factors: history of SH, treatment of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, personality disorder, and psychiatric clinic |

Medium risk |

| Bilen (2014) | Sweden | 0.5 years (At least 0.5 years for all cases) | SH | 18 years or above | 28.3 | 325 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: history of SH, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, and psychiatric clinic. |

Medium risk |

| Birtwistle (2017) | UK | Mean: 4.4 years | Suicide | 12 years or above | 42.0 | 6024 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age Clinical factors: history of SH. |

Medium risk |

| Chen (2013) | Taiwan, China | Mean:1.43 years | Suicide | 10–98 years | 29.4 | 3299 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, and employment. Clinical factors: physical illness and` diagnosis of psychiatric disorder |

Low risk |

| Chen (2011) | Taiwan, China | Mean: 5.8 years | Suicide | 11–90 years | 36.3 | 1080 | Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, educational level, and marital status | Low risk |

| Chen (2010) | Taiwan, China | Mean: 3.7 years | SH | 11–90 years | 37.0 | 970 | Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, educational level, and marital status | Medium risk |

| Chung (2012) | Taiwan, China | 0–8 years | SH | All age groups but not identifying the range | 46.1 | 39,875 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: physical illness and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. |

Low risk |

| Chung (2013) | Taiwan, China | 0–8 years | Suicide | 10 years or above | 43.5 | 3388 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: physical illness and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Corcoran (2015) | UK | 1 year (At least 1 year for all cases) | SH | All age groups but not identifying the range | 46.3 | 3337 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: history of SH. |

Medium risk |

| Cully (2021) | Ireland | 0–1 year | SH | 18 years or above | 52.8 | 324 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: treatment of psychiatric disorder |

Medium risk |

| Hawton (2015) | UK | 2–13 years | Suicide | 7–97 years | 41.5 | 40,346 | Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. | High risk |

| Kapur (2015) | UK | 0–1 years | Suicide | 10 years or above | 43.0 | 38,415 | Clinical factors: psychiatric hospitalization | Low risk |

| Kawahara (2017) | Japan | 0–0.5 years | SH | 12–88 years | 29.9 | 405 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: history of SH, treatment of psychiatric disorder, physical illness, and psychiatric hospitalization |

Medium risk |

| Knipe (2019) | Sri Lanka | Median:1.9 years | SH | 10 years or above | 49.7 | 2259 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: history of SH. |

Medium risk |

| Suicide | Medium risk | |||||||

| Kuo (2012) | Taiwan, China | Median: 3.3 years | Suicide | 15 years or above | 27.8 | 8343 | Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. | Low risk |

| Kwok (2014) | Taiwan, China | Median: 1.4 years | SH | 15–96 years | 30.5 | 7601 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, and marital status. Clinical factors: history of SH. |

Medium risk |

| Lindh (2018) | Sweden | 0.5 year (At least 1 year for all cases) | SH | 18–95 years | 33.0 | 804 | Sociodemographic factors: gender. | High risk |

| Suicide | High risk | |||||||

| Madsen (2013) | Denmark | Mean: 4.2 years | Suicide | 18 years or above | 45.2 | 17,257 |

Sociodemographic factors: employment, educational level, and marital status. Clinical factors: Mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorder, and psychiatric clinic. |

Medium risk |

| Miller (2013) | US | 0–5 years | SH | 15 years or above | 41.6 | 3600 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, and personality disorder. |

Low risk |

| Suicide | Low risk | |||||||

| Olfson (2013) | US | 0.08 years | SH | 21–64 years | 31.8 | 5567 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder and personality disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Olfson (2017) | US | 0–1 years | SH | 18–64 years | 33.0 | 61,054 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: treatment of psychiatric disorder, psychiatric hospitalization, and psychiatric clinic. |

Medium risk |

| Suicide | ||||||||

| Perry (2012) | Ireland | 0–1 years | SH | 10 years or above | Not available | 48,206 |

Sociodemographic factors: age. Clinical factors: history of SH |

Medium risk |

| Riedi (2012) | France | 0.5 years (At least 0.5 years for all cases) | SH | Mean: 37.8 years (SD: 12.1 years) | 29.0 | 184 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and employment. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, and anxiety disorder |

High risk |

| Runeson (2016) | Sweden | Mean: 5.3 years | Suicide | 10 years or above | 40.6 | 34,219 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, and personality disorder. |

Low risk |

| Steeg (2018) | UK | 1 year (At least 1 years for all cases) | Suicide | 16 years or above | 42.0 | 31,715 | Clinical factors: psychiatric hospitalization, and psychiatric clinic. | Low risk |

| Thomas (2021) | US | 2 years | SH | 5 years or above | 37.0 | 9518 |

Sociodemographic factors: age and gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder |

Median risk |

| Suicide |

Sociodemographic factors: age and gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and history of SH |

Low risk | ||||||

| Tidemalm (2015) | Sweden | 9–19 years | Suicide | 10 years or above | 42.4 | 53,843 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and history of SH. |

Low risk |

| Vuagnat (2019) | France | 0–1 years | Suicide | 16 years or above | 37.2 | 136,451 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: history of SH. |

Medium risk |

| Definition of SH: SA | ||||||||

| Aguglia (2020) | Italy | 0–0.5 years | SA | 18 years or above | 22.9 | 432 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: history of SA, mood disorder, and psychotic disorder |

Medium risk |

| Chen (2016) | Taiwan, China | 0–3 years | SA | All age groups but not identifying the range | 33.0 | 51,579 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age |

Medium risk |

| Suicide | 25.0 | 6485 | Medium risk | |||||

| Chen (2013) | Taiwan, China | 0–0.5 years | SA | Mean: 38 years (SD: 15 years) | 31.6 | 1056 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and employment. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and history of SA. |

Medium risk |

| Chung (2021) | Taiwan, China | 0–16 years | SA | 10 years or above | 45.6 | 24,300 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: physical illness and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, and psychiatric hospitalization. |

Medium risk |

| Demesmaeker (2021) |

France | 0–1.17 years | SA | 18 years or above | 36.4 | 972 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: history of SA, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, and eating disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Espandian (2020) | Spain | 1 year (At least 1 year for all cases) | SA | 18 years or above | 25.7 | 319 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, marital status, employment, and educational level. Clinical factors: history of SA, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, personality disorder, anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Exbrayat (2017) | France | 1 year (At least 1 year for all cases) | SA | 18 years or above | 30.4 | 823 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and employment. Clinical factors: history of SA, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, personality disorder, anxiety disorder, eating disorder, and psychiatric hospitalization. |

Medium risk |

| Fedyszyn (2016) | Denmark | 0–16 years | SA | All age groups but not identifying the range | Not available | 11,802 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: treatment of psychiatric disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Suicide | Clinical factors: psychiatric hospitalization | Low risk | ||||||

| Fossi (2021) | France | 0.5 years | SA | Mean: 40.6 (SD: 15.0 years) | 41.3 | 10,666 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: history of SA |

Medium risk |

| Haglund (2016) | Sweden | 0.5 year (At least 0.5 year for all cases) | SA | 10–92 years | 37.5 | 355 | Sociodemographic factors: gender. | High risk |

| Suicide | High risk | |||||||

| Huang (2014) | Taiwan, China | 1–6 years | SA | Mean: 40.5 years (SD:15.6 years) | 32.7 | 2070 | Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, marital status, and educational level. | Medium risk |

| Irigoyen (2019) | Spain | Mean: 1.7 years | SA | 18 years or above | 33.4 | 371 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: history of SA, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder, and personality disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Johannessen (2011) | Norway | 0–5 years | SA | 15 years or above | 31.7 | 1304 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: history of SA. |

Medium risk |

| 0–20 years | Suicide | Medium risk | ||||||

| Lipsicas (2014) | Multiple countries from Europe | 1 years (At least 1 years for all cases) | SA | Mean: 36.3 years (SD: 16.7 years) | 40.5 | 11,942 | Sociodemographic factors: gender. | Medium risk |

| Liu (2022) | China | 0–10 years | Suicide | 15–70 years | 36.3 | 1103 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and marital status. Clinical factors: physical illness and history of SA, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. |

Low risk |

| Mehlum (2010) | Norway | 0–5.5 years | SA | 18 years or above | 34.8 | 911 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: physical illness and treatment of psychiatric disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Monnin (2012) | France | 0–2 years | SA | 20 years or above | 30.8 | 273 | Clinical factors: treatment of psychiatric disorder, history of SA, anxiety disorder, psychotic disorder, and substance use disorder. | Medium risk |

| O'Connor (2012) | UK | 2 years (At least 2 years for all cases) | SA | 16 years or above | 36.7 | 237 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, marital status, and employment. Clinical factors: history of SA. |

Medium risk |

| O'Connor (2017) | US | 0.5 years (At least 0.5 years for all cases) | SA | Mean: 37.3 years (SD: 10.54 years) | 54.0 | 160 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: history of SA. |

High risk |

| Pan (2013) | Taiwan, China | Median: 1.4 years | Suicide | 15 years or above | 33.5 | 50,805 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Parra-Uribe (2017) | Spain | 1 years (At least 1 years for all cases) | SA | Mean: 40.8 years (SD: 16.0 years) | 37.6 | 1241 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, marital status, educational level, and employment. Clinical factors: personality disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Pavarin (2014) | Italy | 0–8.5 years | Suicide | Mean: 45.6 years | 39.4 | 505 | Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. | Low risk |

| Runeson (2010) | Sweden | 21–31 years | Suicide | 10 years or above | 48.4 | 48,649 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, psychotic disorder, and mood disorder. |

Low risk |

| Sawa (2017) | Japan | Mean: 3.7 years | SA | Mean: 39.8 years | 31.6 | 291 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, substance use disorder, psychotic disorder, and personality disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Wang (2015) | Taiwan, China | 1–6 years | Suicide | Mean:40.4 years (SD: 15.6 years) | 32.4 | 2052 | Sociodemographic factors: gender, age, educational level, and marital status. | Medium risk |

| Definition of SH: SC | ||||||||

| Carroll (2016) | UK | Mean: 2.1 years | Suicide | 14- 101 years | 41.1 | 3928 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender. Clinical factors: history of SC, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, mood disorder, and personality disorder |

Low risk |

| Definition of SH: SP | ||||||||

| Finkelstein (2015) | Canada | Median: 5.3 years | Suicide | Median: 32 years (IQR:25 years) | 38.3 | 65,784 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: history of SP, mood disorder, and substance use disorder. |

Low risk |

| Finkelstein (2016) | Canada | Median:4.3 years | SP | 10 years or above | 38.2 | 81,675 |

Sociodemographic factors: gender and age. Clinical factors: mood disorder, and substance use disorder. |

Medium risk |

| Pushpakumara (2019) | Sri Lanka | 0.08 years (At least 0.08 years for all cases) | SP | 10 years or above | 50.8 | 4022 | Sociodemographic factors: gender. | High risk |

| Rajapakse (2016) | Sri Lanka | 1 years (At least 1 years for all cases) | SP | 14 years or above | 44.2 | 335 | Sociodemographic factors: gender. | High risk |

SH: self-harm, SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range, NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, SA: suicide attempt, SP: self-poisoning, SC: self-cutting.

Associating factors for SH repetition

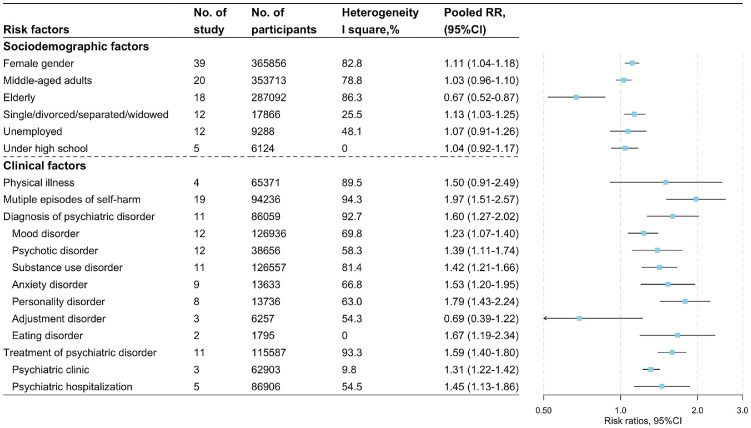

Figure 2 shows the associating factors related to SH repetition. The forest plots of associating factors for SH repetition could be seen in the Supplementary material 3. The number of included participants for pooling the associating factors was between 1795 and 365856 and the number of included studies for pooling associating factors was between 2 and 39.

Figure 2.

Characteristics, heterogeneity, and pooled estimates for sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with risk for SH repetition (No.: number, RR: risk ratio, CI: confidence interval. Horizontal line span 1 represented statistically significant. The reference for middle-aged adults and elderly was adolescent and young adults. Each line represented a pool estimate by meta-analysis.).

The sociodemographic factors including female gender (RR: 1.11, 95%CI: 1.04–1.18, I2=82.8%), and a marital status of being single (RR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.03–1.25, I2=25.5%) were found to be associated with increased risk of SH repetition. Compared with adolescents and young adults, the elderly had a lower risk of SH repetition (RR: 0.67, 95%CI: 0.52–0.87, I2=86.3%). Employment and educational level were not found to have statistically significant associations with SH repetition.

Clinical factors showed stronger associations with SH repetition compared with sociodemographic factors. Multiple episodes of SH (RR: 1.97, 95%CI: 1.51–2.57, I2=94.3%), diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (RR: 1.60, 95%CI: 1.27–2.02, I2=92.7%), and treatment of psychiatric disorder (RR: 1.59, 95%CI: 1.40–1.80, I2=93.3%) were all found to be associated with increased risk of SH repetition. Some specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders including mood disorder (RR: 1.23, 95%CI: 1.07–1.40, I2=69.8%), psychotic disorder (RR: 1.39, 95%CI: 1.11–1.74, I2=58.3%), substance use disorder (RR: 1.42, 95%CI: 1.21–1.66, I2=81.4%), anxiety disorder (RR: 1.53, 95%CI: 1.20–1.95, I2=66.8%), eating disorder (RR: 1.67, 95%CI: 1.19–2.34, I2=0) and personality disorder (RR: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.43–2.24, I2=63.0%) were associated with increased risk of SH repetition. However, there was not statistically significance between adjustment disorder and SH repetition. Specific methods of treatment of psychiatric disorders such as psychiatric clinic (RR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.22–1.42, I2=9.8%) and psychiatric hospitalization (RR: 1.45, 95%CI: 1.13–1.86, I2=54.5%) were both related to have increased risk of SH repetition. Besides, physical illness was not found to have statistically significant associations with SH repetition. The forest plots of associating factors for SH repetition and more details about the pooled estimates could be seen in the supplementary material 3.

Associating factors for suicide following SH

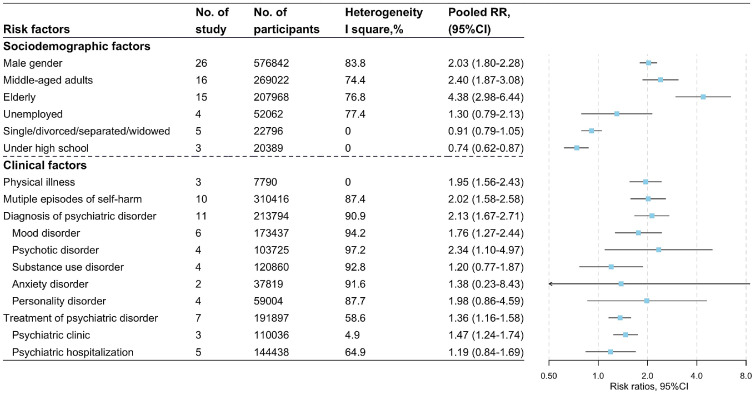

Associating factors for suicide following SH could be seen in the Figure 3. The number of included participants for pooling the associating factors was between 7790 and 576,842 and the number of included studies for pooling associating factors was between 2 and 26.

Figure 3.

Characteristics, heterogeneity, and pooled estimates for sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with risk for suicide following self-harm (No.: number, RR: risk ratio, CI: confidence interval, horizontal line span 1 represented statistically significant. The reference for middle-aged adults and elderly was adolescent and young adults. Each line represented a pool estimate by meta-analysis).

Among the sociodemographic factors, male gender (RR: 2.03, 95%CI: 1.80–2.28, I2=83.8%), middle-aged adults (RR: 2.40, 95%CI: 1.87–3.08, I2=74.4%), and the elderly (RR: 4.38, 95%CI: 2.98–6.44, I2=76.8%) were significantly associated with increased risk of suicide following SH. Compared with high school or above, under high school had a lower risk of suicide following SH (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.62–0.87, I2=0). Unemployment and a marital status of being single were not found to have statistically significant associations with SH repetition.

Some clinical factors showed significant effect on suicide following SH. Physical illness (RR: 1.95, 95%CI: 1.56–2.43, I2=0), multiple episodes of SH (RR: 2.02, 95%CI: 1.58–2.58, I2=87.4%), diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (RR: 2.13, 95%CI: 1.67–2.71, I2=90.9%), and treatment of psychiatric disorder (RR: 1.36, 95%CI: 1.16–1.58, I2=58.6%) were all found to be associated with increased risk of suicide following SH. Some specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders including mood disorder (RR: 1.76, 95%CI: 1.27–2.44, I2=94.2%), and psychotic disorder (RR: 2.34, 95%CI: 1.10–4.97, I2=97.2%) were associated with increased risk of suicide following SH. However, there was not statistically significance between other types of psychiatric disorders and suicide following SH. Specific methods of treatment of psychiatric disorders such as psychiatric hospitalization (RR: 1.19, 95%CI: 0.84–1.69, I2=64.9%) were also not found to have statistically significant associations with suicide following SH. Psychiatric clinic (RR: 1.47, 95%CI: 1.24–1.74, I2=84.2%), which included only three records, was found to be associated with suicide following SH. The forest plots of associating factors for suicide following SH and more details about the pooled estimates could be seen in the supplementary material 3.

Subgroup analysis and heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses by follow-up time were additionally performed and shown in the Supplementary material 4. The associating factors including the elderly, female gender, a marital status of being single, multiple episodes of SH, and diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorder seemed to have a significant effect on SH repetition in the group of long-term follow-ups. Middle-aged adult, unemployment, multiple episodes of SH, and diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorder were significantly associated with increased risk of suicide following SH in the group of short-term follow-ups. Apart from significant association of treatment of psychiatric disorder with suicide following SH in the group of short-term period, the estimates of other associating factors were similar with total estimates regardless of follow-up time. The heterogeneity of associating factors decreased in the subgroup analysis of follow-up time, namely middle-aged adult, female gender, unemployment and physical illness in the short-term period and a marital status of being single in the long-term period for SH repetition and middle-aged adult, male gender, multiple episodes of SH, diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorder in the short-term period for suicide following SH.

Subgroup analysis by the definition of SH was also performed in this study. The details could be seen in the Table 2. Consistent with total estimates, the elderly, multiple episodes of SH, and treatment of psychiatric disorder were significantly associated with SH repetition and advancing age (middle-aged adults and the elderly), male gender, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder was associated with increased risk of suicide following SH. Differently, the associating factors including female gender and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder seemed only to have a significant effect on SH repetition among suicide attempters and a marital status of single was only related to SH repetition among the cases with a definition of SH/SP/SC. Physical illness, treatment of psychiatric disorder and multiple episodes of SH were only significantly associated with increased risk of suicide following SH among the cases with a definition of SH/SP/SC. The heterogeneity of associating factors decreased in the subgroup analysis of the definition of SH, namely physical illness under the definition of SH/SP/SC for SH repetition and middle-aged adult under the definition of SA and male gender and treatment of psychiatric disorder under the definition of SH/SP/SC for suicide following SH.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses by the definition of self-harm.

| Associating factors | SH repetition |

Suicide following SH |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of SH: SH/SP/SC |

Definition of SH: SA |

Definition of SH: SH/SP/SC |

Definition of SH: SA |

|||||

| n | RR (95%CI), I2 | n | RR (95%CI), I2 | n | RR (95%CI), I2 | n | RR (95%CI), I2 | |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||||

| Middle-aged (Ref. adolescent and young adults) | 13 | 1.02 (0.94–1.10), 79.3% | 7 | 1.08 (0.85–1.36), 80.2% | 12 | 2.48 (1.84–3.35), 80.2% | 4 | 2.21 (1.55–3.16), 0 |

| Elderly (Ref. adolescent and young adults) | 11 | 0.74 (0.58–0.96), 72.7% | 7 | 0.56 (0.38–0.82), 83.0% | 11 | 4.05 (2.59–6.33), 80.8% | 4 | 5.69 (2.45–13.18), 57.3% |

| Gender* | 19 | 1.07 (0.99–1.15), 75.3% | 20 | 1.15 (1.03–1.29), 83.1% | 17 | 2.08 (1.95–2.22), 26.6% | 9 | 1.72 (1.39–2.12), 69.3% |

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 4 | 1.19 (1.03–1.37), 30.0% | 8 | 1.09 (0.95–1.24), 27.5% | 2 | 0.97 (0.68–1.39), 47.4% | 3 | 1.03 (0.69–1.53). 0 |

| Unemployment | 3 | 1.06 (0.60–1.86), 63.3% | 9 | 1.09 (0.92–1.29), 44.1% | 3 | 1.08 (0.69–1.70), 68.3% | 1 | 2.11 (1.11–3.99), NA |

| Under high school | 2 | 1.08 (0.93–1.26), 0 | 3 | 0.96 (0.78–1.18), 0 | 2 | 0.73 (0.62–0.87), 0 | 1 | 0.79 (0.39–1.60), NA |

| Clinical factors | ||||||||

| Physical illness | 2 | 1.11 (0.98–1.25), 0 | 2 | 1.93 (0.64–5.87), 94.4% | 2 | 2.15 (1.36–3.40), 34.8% | 1 | 1.41 (0.50–3.99), NA |

| Multiple episodes of SH | 8 | 2.24 (1.58–3.19), 93.5% | 11 | 1.77 (1.14–2.74), 94.1% | 8 | 2.05 (1.57–2.66), 89.8% | 2 | 2.02 (0.74–5.50), 65.4% |

| Diagnosis of psychiatric disorder | 6 | 1.32 (0.99–1.75), 91.6% | 5 | 2.29 (1.38–3.81), 94.4% | 7 | 2.44 (1.83–3.25), 65.9% | 4 | 1.81 (1.33–2.45), 76.8% |

| Treatment of psychiatric disorder | 6 | 1.47 (1.30–1.66), 91.8% | 5 | 1.90 (1.30–2.78), 84.1% | 5 | 1.35 (1.19–1.53), 37.3% | 2 | 0.80 (0.16–4.12), 90.1% |

Male gender and female gender as the reference groups for suicide and repetition following self-harm, respectively.

SA: suicide attempt, SH: self-harm, SP: self-poisoning, SC: self-cutting, RR: risk ratio, CI: confidential interval.

n: The number of studies included in the subgroup analysis.

NA: I2 is not available when there was only one study included in the estimates.

Meta-regression and heterogeneity

The heterogeneity (I2) of included associating factors varied in this study (Figs. 2 and 3). Respective meta-regression model for each associating model was presented in the Table 3. As for SH repetition, adjusted model could result in higher estimates for diagnosis of adjustment disorder and lower estimates for diagnosis of substance use disorder. The RRs associated with unemployment diagnosis of anxiety disorder and psychiatric hospitalization were significantly smaller and female gender was significantly larger in size as the follow-up time increased. Higher estimates of multiple episodes of SH and diagnosis of adjustment disorder and lower estimates of the elderly (compared with adolescent and young adults), diagnosis of substance use disorder, and treatment of psychiatric disorder were independently associated with larger sample size. Suicide attempt as the definition of SH could result in higher estimates for diagnosis of personality disorder and lower estimates for diagnosis of adjustment disorder.

Table 3.

Factors associated with heterogeneity assessed by meta-regression analysis.

| Associating factors | SH repetition, slope (P) |

Suicide following self-harm, slope (P) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted model (Ref: crude model) | Long-term follow-up (Ref: short-term follow-up) | Sample size (ln) | SA as the definition of SH (Ref: SH/SP/SC) | Adjusted model (Ref: crude model) | Long-term follow-up (Ref: short-term follow-up) | Sample size (ln) | SA as the definition of SH (Ref: SH/SP/SC) | |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||||

| Middle-aged (Ref. adolescent and young adults) | 0.034 (0.640) | −0.106 (0.113) | −0.074 (0.146) | 0.047 (0.585) | −0.436 (0.103) | 0.004 (0.990) | 0.317 (0.105) | −0.159 (0.622) |

| Elderly (Ref. adolescent and young adults) | −0.165 (0.565) | −0.380 (0.139) | −0.424 (0.002) | −0.302 (0.192) | −1.048 (0.011) | −0.507 (0.229) | 0.232 (0.462) | 0.342 (0.472) |

| Gender* | 0.111 (0.084) | 0.154 (0.009) | 0.066 (0.135) | 0.092 (0.148) | −0.012 (0.924) | −0.009 (0.941) | −0.050 (0.595) | −0.247 (0.004) |

| Single/divorced/ separated/widowed |

0.150 (0.122) | 0.141 (0.195) | 0.044 (0.723) | −0.094 (0.361) | −0.247 (0.179) | −0.292 (0.326) | −0.223 (0.181) | 0.135 (0.535) |

| Unemployment | −0.181 (0.337) | −0.295 (0.048) | −0.482 (0.062) | 0.127 (0.560) | −0.669 (0.192) | −0.863 (0.177) | −0.749 (0.023) | 0.669 (0.192) |

| Under high school | −0.135 (0.337) | 0.007 (0.973) | −0.213 (0.621) | −0.118 (0.365) | 0.041 (0.875) | −0.076 (0.838) | −0.033 (0.890) | 0.076 (0.838) |

| Clinical factors | ||||||||

| Physical illness | 0.207 (0.763) | 0.474 (0.496) | 0.220 (0.588) | 0.493 (0.420) | ⁎⁎⁎ | −0.579 (0.203) | 0.848 (0.516) | −0.422 (0.500) |

| Multiple episodes of SH | 0.304 (0.296) | −0.061 (0.842) | 0.500 (0.014) | −0.235 (0.411) | 0.198 (0.473) | −0.159 (0.582) | 0.041 (0.831) | −0.088 (0.817) |

| Diagnosis of psychiatric disorder | 0.076 (0.757) | 0.161 (0.543) | −0.142 (0.389) | 0.505 (0.059) | 0.408 (0.096) | 0.075 (0.778) | 0.245 (0.250) | −0.308 (0.151) |

| Mood disorder | 0.016 (0.906) | −0.028 (0.853) | 0.010 (0.894) | 0.029 (0.845) | 0.522 (0.242) | 0.249 (0.550) | 0.132 (0.739) | −0.059 (0.924) |

| Psychotic disorder | −0.345 (0.088) | −0.221 (0.381) | −0.205 (0.216) | −0.014 (0.955) | 1.001 (0.314) | −0.068 (0.944) | 0.456 (0.635) | 0.320 (0.810) |

| Substance use disorder | −0.400 (0.040) | −0.140 (0.428) | −0.261 (0.037) | 0.035 (0.840) | 0.343 (0.499) | −0.163 (0.778) | −0.045 (0.940) | ⁎⁎⁎ |

| Anxiety disorder | −0.379 (0.193) | −0.529 (0.001) | −0.352 (0.169) | 0.440 (0.057) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Personality disorder | 0.251 (0.350) | 0.069 (0.806) | −0.174 (0.536) | 0.468 (<0.001) | 1.250 (<0.001) | −0.090 (0.926) | 0.266 (0.804) | ⁎⁎⁎ |

| Adjustment disorder | 0.760 (0.039) | −0.284 (0.716) | 0.628 (0.038) | −0.760 (0.039) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Treatment of psychiatric disorder | 0.035 (0.838) | −0.033 (0.793) | −0.157 (0.025) | 0.245 (0.055) | 0.036 (0.886) | 0.018 (0.917) | 0.346 (0.183) | −0.089 (0.722) |

| Psychiatric clinic | −0.286 (0.136) | −0.080 (0.740) | −0.067 (0.328) | ⁎⁎⁎ | 0.219 (0.194) | −0.219 (0.194) | 0.327 (0.386) | ⁎⁎⁎ |

| Psychiatric hospitalization | ⁎⁎⁎ | −0.407 (0.025) | −0.228 (0.130) | −0.302 (0.319) | ⁎⁎⁎ | −0.207 (0.652) | 0.656 (0.109) | −0.207 (0.652) |

Male gender and female gender as the reference groups for suicide and repetition following self-harm, respectively.

Meta-regression was only performed when the number of included articles was above 3 records.

Only one category was found in the corresponding variable.

SA: suicide attempt, SH: self-harm, SP: self-poisoning, SC: self-cutting.

As for suicide following SH, adjusted model resulted in lower estimates for the elderly and higher estimates for diagnosis of personality disorder. Lower estimates of unemployment were independently associated with larger sample size. Suicide attempt as the definition of SH resulted in lower estimates for male gender.

Due to the substantial heterogeneity found in this study, these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analyses were performed for each associating factor related to suicide and repetition following SH by excluding one study at a time. The combined RR of overall risk estimates were relatively consistent and without apparent fluctuation. Although the pooled RRs did not materially change in term of strength of effects in the sensitivity analyses, some included studies might result in changes in statistical significance, such as adjustment disorder of SH repetition, and educational level, physical illness, psychotic disorder, personality disorder, and psychiatric hospitalization of suicide following SH. More details could be seen in the Supplementary material 5. The analyses did not substantially change the pooled estimates by deleting the studies with high risk of bias (Supplementary material 6).

Funnel plots for each meta-analysis in this study are presented in Supplementary material 7. Although the funnel plots showed relatively minimal asymmetry for these meta-analyses, analyses for publication bias were only found for the estimates of gender of suicide following SH (P = 0.021) by Egger test. After adjusting for funnel plot asymmetry by trim-and-fill methods, male gender was still associated with increased risk of suicide following SH (RR: 1.75, 95%CI: 1.57–1.95, I2=83.8%). Begg test and Egger test for other meta-analyses could be seen in the Supplementary material 8.

Discussion

Previous reviews summarized that male gender14,15 and elder age15 were associated with suicide following SH. Our results from meta-analyses are in line with these findings and further showed that the risk of suicide following SH for the males is two folds higher than that in females, and that the risk of suicide following SH in the middle-aged adults and the elderly is 2.4 and 4.4 times higher than that in the younger age. The finding of middle-aged adults increasing the risk of suicide attempt repetition in a previous appraisal84 is different from the estimates in this study. However, our study supported that the elderly has lower risk of SH repetition. Another finding is that the risk of SH repetition in the females was slightly higher than that in the males, which was not reported in the previous reviews. The characteristics of age and gender related to suicide and repetition following SH should be paid more attention and could provide some evidence for SH and suicide prevention.

The study of Beghi et al.84 mentioned that the role of demographic factors on risk for suicide and repetition following SH is less clear. Our finding showed that only living in a single marital status was related to SH repetition and educational level was related to suicide following SH. The possible explanation is that SH repetition occurs more often in the short time after SH, while death by suicide tends to occur in the long period after SH.12 The socioeconomic factors at the time of initial SH may have changed greatly when repeated SH or suicide occurs. Compared with some clinical factors, the influence of demographic and socioeconomic factors may be weaker. Consistent with a previous systematic review,14,15 this review also found physical illness was associated with increased risk of suicide following SH, but not for SH repetition. These findings could be explained by the high suicide intent in the population of SH with physical illness.85

Consistent with previous reviews,13, 14, 15 multiple episodes of SH, and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder were highly associated with increased risk of suicide and repetition following SH. This review moreover examined the risk of suicide and repetition following SH associated with specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders, which could add some evidence for clinical prevention of adverse outcomes of SH. Personality disorder are at the highest risk of SH repetition and psychotic disorder at the highest risk of suicide following SH. In addition, psychiatric treatment, whether psychiatric clinic or hospitalization does not seem to have the effect on decreasing the risk of suicide and repetition following SH. Kapur et al. using a large cohort of UK found that most aspects of management were not significantly associated with increased risk of total mortality and suicide in adjusted models.64 The hospitals and clinical services might be assigning the most intensive management to the highest risk patients.64 In that case, psychiatric hospitalization, as the minority of cases for SH, is associated with higher risk of suicide and repetition following SH compared with mild SH. However, Kapur et al. also mentioned that psychiatric admission might be a life-saving intervention for some high-risk population.64 More randomized controlled trials are needed to explore the associations in the future.

The review of Beghi et al.15 mentioned that associating factors of suicide and repetition following suicide attempt were not comparable for meta-analysis in consideration of different designs and follow-up time. Therefore, this review and meta-analysis included the longitudinal studies of recent 10 years to obtain stable and trustable estimates. Although heterogeneity for some of meta-analytic associating factors were relatively high, relative factors including adopted model, follow-up time, sample size, definition of SH, and risk of bias were used to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity by meta-regression models. Besides, stabilization of pooled estimates was also examined by sensitivity analyses of leave-one-out method. Unstable meta-analytic estimates are from diagnosis of psychiatric disorder,46,66,69,70,81 educational level,66 physical illness61 and psychiatric hospitalization.58 These studies included some studies with a shorter time of follow-up (30 days),46 which might have contributed to high heterogeneity for the specific diagnoses of psychiatric disorders. The reason of unstable estimates of educational level and psychotic disorder caused by study of Madsen66 might be included cases in this study only including SH before psychiatric admission. The study of Bostwick58 found that psychiatric hospitalization was associated with decreased risk of suicide following SH, which was conflict with the other included studies. Although this study taking advantage of long-term follow-up, the small cohort of the patients (1442 for prospective design) might underpower the results for the associations between psychiatric hospitalization and suicide. Chung et al.61 used the data of repeated self-harm to explore the association of physical illness with suicide and might exaggerate the effect of physical illness because of poor condition compared with the cases of first self-harm. Some other factors such as different methods of diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders, cultural characteristics, provision of health services, and the loss of follow-up might have an effect on heterogeneity.

However, some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, due to the contextual heterogeneity of pooling estimates of the included studies, these findings need to be taken with considerable caution. More studies are needed to explore the factors which could have effect on the estimates. Second, the cut-offs of age band were not fixed because of different criteria among the included studies. However, adolescents and young adults, middle-aged adults and the elderly were used to distinguish the different period in the life and might have more clinical implications. Third, the number of included studies is relatively small for some associating factors, extrapolation of this conclusion should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, included studies from low-and-middle-income countries are few, more studies are warranted in this area. Finally, only English-written studies were included, which might lead to selection bias towards findings from Western countries.

In conclusion, a range of sociodemographic and clinical factors are identified to increase the longitudinal risk of suicide and repetition following SH. Female adolescents and male elder with self-harming behaviors should be paid more attention with the higher risk of suicide and repetition following SH, respectively. What's more, comorbidity of self-harm and psychiatric disorder and multiple repetition of SH are other concerns for preventing adverse outcomes of SH. Strategies to address these associating factors could have some effects on intervention and prevention of subsequent SH and suicide. Implementing interventions such as regular follow-up of SH and valid treatment of psychiatric disorder should be considered. The insightful details found in this study could inform personalized clinical care and suicide preventions in SH patients as a high-risk group.

Data sharing statement

The study protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021248695). Raw data are available upon request from jiacunxian@sdu.edu.cn or shixueli@sdu.edu.cn.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [No: 82103954; 30972527; 81573233].

Contributors

BPL, PQ, SXL and CXJ formulated the research question and design the study. BPL, YYZ, YKY, and XL contributed the acquisition and extraction of data, and quality assessment. BPL analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript, had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101461.

Contributor Information

Cun-Xian Jia, Email: jiacunxian@sdu.edu.cn.

Shi-Xue Li, Email: shixueli@sdu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hawton K., Zahl D., Weatherall R. Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:537–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard D.S., Gurewich D., Lwin A.K., Reed G.A., Jr., Silverman M.M. Suicide and suicidal attempts in the United States: costs and policy implications. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(3):352–362. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsiachristas A., McDaid D., Casey D., et al. General hospital costs in England of medical and psychiatric care for patients who self-harm: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(10):759–767. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30367-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1603–1658. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Practice Manual For Establishing and Maintaining Surveillance Systems For Suicide Attempts and Self-Harm. 2016. https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/attempts_surveillance_systems/en/.

- 6.Rahman F., Webb R.T., Wittkowski A. Risk factors for self-harm repetition in adolescents: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen V.C., Tan H.K., Cheng A.T., et al. Non-fatal repetition of self-harm: population-based prospective cohort study in Taiwan. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):31–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knipe D., Metcalfe C., Hawton K., et al. Risk of suicide and repeat self-harm after hospital attendance for non-fatal self-harm in Sri Lanka: a cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(8):659–666. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K., Harriss L., Zahl D. Deaths from all causes in a long-term follow-up study of 11,583 deliberate self-harm patients. Psychol Med. 2006;36(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjornaas M.A., Jacobsen D., Haldorsen T., Ekeberg O. Mortality and causes of death after hospital-treated self-poisoning in Oslo: a 20-year follow-up. Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia, Pa) 2009;47(2):116–123. doi: 10.1080/15563650701771981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen V.C., Tan H.K., Chen C.Y., et al. Mortality and suicide after self-harm: community cohort study in Taiwan. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(1):31–36. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B.P., Lunde K.B., Jia C.X., Qin P. The short-term rate of non-fatal and fatal repetition of deliberate self-harm: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2020;273:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larkin C., Di Blasi Z., Arensman E. Risk factors for repetition of self-harm: a systematic review of prospective hospital-based studies. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e84282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan M.K., Bhatti H., Meader N., et al. Predicting suicide following self-harm: systematic review of risk factors and risk scales. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(4):277–283. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.170050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beghi M., Rosenbaum J.F., Cerri C., Cornaggia C.M. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1725–1736. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S40213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First M.B., Spitzer R.L., Gibbon M., William J.B.W. Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. Structured Clinical Interview For DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, 11/2002 Revision) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Well G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonramdomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 18.Viale L., Allotey J., Cheong-See F., et al. Epilepsy in pregnancy and reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10006):1845–1852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xi B., Huang Y., Reilly K.H., et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of hypertension and CVD: a dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(5):709–717. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514004383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguglia A., Solano P., Parisi V.M., et al. Predictors of relapse in high lethality suicide attempters: a six-month prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2020;271:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergen H., Hawton K., Kapur N., et al. Shared characteristics of suicides and other unnatural deaths following non-fatal self-harm? A multicentre study of risk factors. Psychol Med. 2012;42(4):727–741. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhaskaran J., Wang Y., Roos L., Sareen J., Skakum K., Bolton J.M. Method of suicide attempt and reaction to survival as predictors of repeat suicide attempts: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):e802–e808. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilen K., Ottosson C., Castren M., et al. Deliberate self-harm patients in the emergency department: factors associated with repeated self-harm among 1524 patients. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(12):1019–1025. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.102616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilen K., Pettersson H., Owe-Larsson B., et al. Can early follow-up after deliberate self-harm reduce repetition? A prospective study of 325 patients. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W.J., Shyu S.S., Lin G.G., et al. The predictors of suicidality in previous suicide attempters following case management services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(5):469–478. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung C.H., Chien W.C., Yeh H.W., Tzeng N.S. Psychiatric consultations as a modifiable factor for repeated suicide attempt-related hospitalizations: a nationwide, population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung C.H., Lai C.H., Chu C.M., Pai L., Kao S., Chien W.C. A nationwide, population-based, long-term follow-up study of repeated self-harm in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:744. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corcoran P., Griffin E., O'Carroll A., Cassidy L., Bonner B. Hospital-treated deliberate self-harm in the western area of Northern Ireland. Crisis. 2015;36(2):83–90. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Espandian A., González M., Reijas T., et al. Relevant risk factors of repeated suicidal attempts in a sample of outpatients. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2020;13(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Exbrayat S., Coudrot C., Gourdon X., et al. Effect of telephone follow-up on repeated suicide attempt in patients discharged from an emergency psychiatry department: a controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1258-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein Y., Macdonald E.M., Hollands S., et al. Repetition of intentional drug overdose: a population-based study. Clin Toxicol. 2016;54(7):585–589. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2016.1177187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y.C., Wu Y.W., Chen C.K., Wang L.J. Methods of suicide predict the risks and method-switching of subsequent suicide attempts: a community cohort study in Taiwan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:711–718. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S61965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irigoyen M., Porras-Segovia A., Galván L., et al. Predictors of re-attempt in a cohort of suicide attempters: a survival analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;247:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawahara Y.Y., Hashimoto S., Harada M., et al. Predictors of short-term repetition of self-harm among patients admitted to an emergency room following self-harm: a retrospective one-year cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwok C.L., Yip P.S., Gunnell D., Kuo C.J., Chen Y.Y. Non-fatal repetition of self-harm in Taipei City, Taiwan: cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:376–382. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipsicas C.B., Makinen I.H., Wasserman D., et al. Repetition of attempted suicide among immigrants in Europe. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 2014;59(10):539–547. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehlum L., Jorgensen T., Diep L.M., Nrugham L. Is organizational change associated with increased rates of readmission to general hospital in suicide attempters? A 10-year prospective catchment area study. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(2):171–181. doi: 10.1080/13811111003704811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monnin J., Thiemard E., Vandel P., et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathological risk factors in repeated suicide attempts: gender differences in a prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor R.C., O'Carroll R.E., Ryan C., Smyth R. Self-regulation of unattainable goals in suicide attempters: a two year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Connor S.S., Comtois K.A., Atkins D.C., Kerbrat A.H. Examining the impact of suicide attempt function and perceived effectiveness in predicting reattempt for emergency medicine patients. Behav Ther. 2017;48(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olfson M., Marcus S.C., Bridge J.A. Emergency department recognition of mental disorders and short-term outcome of deliberate self-harm. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1442–1450. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parra-Uribe I., Blasco-Fontecilla H., Garcia-Pares G., et al. Risk of re-attempts and suicide death after a suicide attempt: a survival analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):163–174. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1317-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pushpakumara P., Thennakoon S.U.B., Rajapakse T.N., Abeysinghe R., Dawson A.H. A prospective study of repetition of self-harm following deliberate self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajapakse T., Griffiths K.M., Cotton S., Christensen H. Repetition rate after non-fatal self-poisoning in Sri Lanka: a one year prospective longitudinal study. Ceylon Med J. 2016;61(4):154–158. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v61i4.8380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riedi G., Mathur A., Seguin M., et al. Alcohol and repeated deliberate self-harm: preliminary results of the French cohort study of risk for repeated incomplete suicides. Crisis. 2012;33(6):358–363. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawa M., Koishikawa H., Osaki Y. Risk factors of a suicide reattempt by seasonality and the method of a previous suicide attempt: a cohort study in a Japanese Primary Care Hospital. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017;47(6):688–695. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perry I.J., Corcoran P., Fitzgerald A.P., Keeley H.S., Reulbach U., Arensman E. The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self harm: findings from the world's first national registry. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cully G., Corcoran P., Leahy D., et al. Factors associated with psychiatric admission and subsequent self-harm repetition: a cohort study of high-risk hospital-presenting self-harm. J Ment Health. 2021;30(6):751–759. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.1979488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demesmaeker A., Chazard E., Vaiva G., Amad A. A pharmacoepidemiological study of the association of suicide reattempt risk with psychotropic drug exposure. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fossi L.D., Debien C., Demarty A.-.L., Vaiva G., Messiah A. Suicide reattempt in a population-wide brief contact intervention to prevent suicide attempts: the VigilanS program, France. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1) doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergen H., Hawton K., Waters K., Cooper J., Kapur N. Psychosocial assessment and repetition of self-harm: the significance of single and multiple repeat episode analyses. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birtwistle J., Kelley R., House A., Owens D. Combination of self-harm methods and fatal and non-fatal repetition: a cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2017;218:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bostwick J.M., Pabbati C., Geske J.R., McKean A.J. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094–1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carroll R., Thomas K.H., Bramley K., et al. Self-cutting and risk of subsequent suicide. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen V.C., Chou J.Y., Hsieh T.C., et al. Risk and predictors of suicide and non-suicide mortality following non-fatal self-harm in Northern Taiwan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(10):1621–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0680-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung C.H., Pai L., Kao S., Lee M.S., Yang T.T., Chien W.C. The interaction effect between low income and severe illness on the risk of death by suicide after self-harm. Crisis. 2013;34(6):398–405. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Finkelstein Y., Macdonald E.M., Hollands S., et al. Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):570–575. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hawton K., Bergen H., Cooper J., et al. Suicide following self-harm: findings from the Multicentre Study of self-harm in England, 2000-2012. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kapur N., Steeg S., Turnbull P., et al. Hospital management of suicidal behaviour and subsequent mortality: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):809–816. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo C.J., Gunnell D., Chen C.C., Yip P.S., Chen Y.Y. Suicide and non-suicide mortality after self-harm in Taipei City, Taiwan. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(5):405–411. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.099366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Madsen T., Agerbo E., Mortensen P.B., Nordentoft M. Deliberate self-harm before psychiatric admission and risk of suicide: survival in a Danish national cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(9):1481–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pan Y.J., Chang W.H., Lee M.B., Chen C.H., Liao S.C., Caine E.D. Effectiveness of a nationwide aftercare program for suicide attempters. Psychol Med. 2013;43(7):1447–1454. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pavarin R.M., Fioritti A., Fontana F., Marani S., Paparelli A., Boncompagni G. Emergency department admission and mortality rate for suicidal behavior. A follow-up study on attempted suicides referred to the ED between January 2004 and December 2010. Crisis. 2014;35(6):406–414. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Runeson B., Haglund A., Lichtenstein P., Tidemalm D. Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: a national cohort study, 2000-2008. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):240–246. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Runeson B., Tidemalm D., Dahlin M., Lichtenstein P., Langstrom N. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tidemalm D., Beckman K., Dahlin M., et al. Age-specific suicide mortality following non-fatal self-harm: national cohort study in Sweden. Psychol Med. 2015;45(8):1699–1707. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]