Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the need to attend to Health Care Workers (HCWs) mental health. What promotes resilience in HCWs during pandemics is largely unknown.

Aim

To appraise and synthesize studies investigating resilience among HCWs during COVID-19, H1N1, MERS, EBOLA and SARS pandemics.

Method

A systematic review of studies from 2002 to 11th March 2022 was conducted. PsychInfo, CINAHL, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and the Cochrane Library databases were searched for qualitative and mixed-methods studies investigating the well-being of HCWs working in hospital settings during a pandemic. Data was extracted, imported into NVivo and analyzed by means of thematic synthesis. Reporting followed PRISMA and ENTREQ guidelines.

Results

One hundred and twenty-one eligible studies (N = 11,907) were identified. The results revealed six main themes underpinning HCWs resilience: moral purpose and duty, connections, collaboration, organizational culture, character and potential for growth.

Conclusion

The studies reviewed indicated that HCWs resilience is mainly born out of their professional identity, collegial support, effective communication from supportive leaders along with flexibility to engage in self-care and experiences of growth.

Keywords: Resilience, Mental health, Health care workers, COVID-19, Pandemic

1. Introduction

In December 2019, the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 was first identified in Wuhan, China. The infectious disease later became known as COVID-19. The disease was declared a global pandemic on March 11th 2020 by the WHO (WHO, 2020). At the current time (17th May 2022) there are 522.73 million confirmed cases across 227 countries worldwide and 6.27 million people have died due to COVID-19. The roll out of the COVID-19 vaccination program on a global scale provides a source of optimism and hope in overcoming the current pandemic with over 11.74 billion vaccine doses administered (17/05/2022) globally (Our World in Data, 2022).

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are obviously at the forefront of dealing with pandemics and may often be among the earliest members of society to experience this event in terms of their own physical and mental health. The psychological impact of a pandemic on HCWs can be significant (Wu et al., 2020). An overwhelming workload, increased exposure to COVID-19, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) or essential technical equipment and separation from loved ones (Chen et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020) can challenge well-being. Literature suggests that between one and two of every five HCWs may report anxiety, depression, distress and sleep problems in this context (Muller, Stensland, & van de Velde, 2020). It is notable that many HCWs do not report elevations in levels of psychological distress (Greenberg et al., 2021), and the experience of stress, anxiety and depression may be viewed as relatively normal emotional reactions during times of crisis (Walton, Murray, & Christian, 2020).

While most research to date has focused on the risks of adverse mental health effects on HCWs, a complementary area of research interest has focused on exploring resilience among workers who are exposed to such stressors (Brooks, Amlôt, Rubin, & Greenberg, 2020). Resilience is considered to include the act of coping (Lee & Cranford, 2008), adapting, or thriving in the context of adversity (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013; Zanotti et al., 2020), and has been viewed as a protective factor for individuals' well-being (Rutter, 1987, Rutter, 2012). Moreover, resilience has been inversely associated with the experience of workplace stress and anxiety (Heath, Sommerfield, & von Ungern-Sternberg, 2020; Jackson, Firtko, & Edenborough, 2007; Kleine, Rudolph, & Zacher, 2019; Pappa, Barnett, Berges, & Sakkas, 2021).

Given the ongoing uncertain trajectory of the present COVID-19 pandemic, understanding key lessons from resilience research with HCWs from the current and previous pandemics is critically important for the development of interventions to support HCWs. Such lessons may also help with appropriate service planning to mitigate any psychological impact and potentially improve HCWs well-being. To date psychological resilience in HCWs during COVID-19 has focused on quantitative investigations (Bozdağ & Ergün, 2020) and the utility of interventions such as Psychological First Aid (Pollock et al., 2020; Sijbrandij et al., 2020). A number of reviews and commentaries have outlined strategies to support resilience and well-being of HCWs during the pandemic (DeTore et al., 2022; Heath et al., 2020; Rieckert et al., 2021; Wald, 2020). Perceived level of adequate training, working in structured units, clear communication and support from supervisors, colleagues, family and friends have been reported as important factors influencing resilience in HCWs (Carmassi et al., 2020). The majority of the data available has arisen from studies employing questionnaire type designs and while many more studies have now utilized qualitative methods, there remains limited understanding from a qualitative perspective as to what might protect HCWs against the negative impact of working during a pandemic.

We used a multidimensional approach to resilience encompassing multiple interacting internal individual systems and external social and ecological protective and promotive systems (Ungar & Theron, 2020) to examine HCWs' resilience. This approach to resilience may be defined as “both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their wellbeing, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided and experienced in culturally meaningful ways” (Ungar, 2008).

The current systematic review aims to synthesize available qualitative data related to resilience in HCWs working through a pandemic. The research question specifically asks, what supports HCWs' resilience while working during a pandemic?

2. Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020224006) and can be accessed in full on www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42020224006. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021), and Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012) guided the preparation of the article, and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) guidelines was used to evaluate the quality of the included research studies (Checklist, 2018).

2.1. Search strategy

Systematic searches using PsychInfo, Medline, CINAHL, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus and the Cochrane Library were undertaken. Gray literature searches along with hand searches of included papers and reference lists of recent, relevant reviews was also completed. No restrictions were set according to publication type. The searches were concluded on 11th March 2022. See Appendix A for an overview of the search strategy and Appendix B for specific search terms used.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Original full text studies describing HCWs' experience of resilience while working during a pandemic since 1st January 2002 to 11th March 2022. were included which incorporated the 5 most recent pandemics. As the SARS pandemic occurred in 2003, the timeframe chosen for this review included available data from 2002 and therefore included COVID-19, H1N1, MERS, EBOLA, and SARS (Houghton et al., 2020; Pollock et al., 2020). The current article was updated to incorporate the latest peer reviewed studies to 11th March 2022.

The following studies were excluded from the meta-synthesis: 1) Studies that focused on resilience and mental health of HCWs who were not working in a hospital setting during a pandemic; 2) Studies that focused on resilience and mental health of patients and the general public only; 3) Studies in languages other than English; 4) Commentary, editorial, case report, dissertation or review; 5) Studies deemed to have no relevant data; 6) Studies that focused on the redeployment of humanitarian HCWs during a pandemic.

2.3. Data screening and extraction

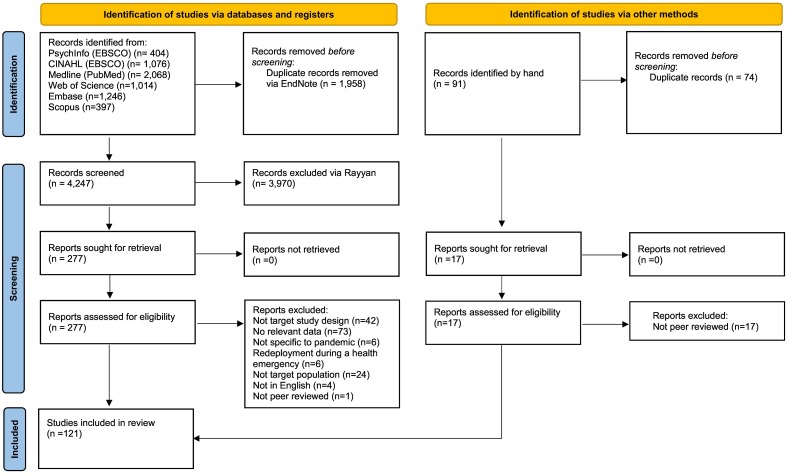

Screening and study selection were conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (see Fig. 1 ). The title and abstracts were screened by two researchers (MC, HLR). Any discrepancies were discussed between MC and HLR. MC and HLR screened all full text studies along with all excluded papers. Any discrepancy in papers to be included at any stage was resolved through discussion by all authors of this review. EndNote X9 was used for managing references and Rayyan software was used for recording decisions. Data was extracted by MC and included authors, publication year, title, countries, virus type, research aims, participant characteristics, study design and findings which were entered onto an excel spreadsheet.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart illustrating the search strategy and paper selection process.

2.4. Quality assessment

The quality of the studies included in the meta-synthesis was assessed using the CASP qualitative research checklist for the purpose of review robustness and assessment of content (Checklist, 2018). The quality appraisal was carried out by MC and HLR and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the third author DGF. No studies were excluded from the meta-synthesis based on their quality.

2.5. Meta-synthesis procedures

The authors followed guidance outlined by Lachal, Revah-Levy, Orri, and Moro (2017) on synthesizing qualitative literature. Extracted data which included both quotations (first order data) and previous authors interpretations (second order data) was exported into NVivo 12 (NVivo, 2022) and analyzed using thematic synthesis. Coding was completed using NVivo software. Codes from the first paper (in authorship alphabetical order) were translated into remaining papers along with the development of new codes until all studies were coded. In the next stage of the analysis descriptive codes were developed and discussed in a number of meetings among all authors. Analytical inductive themes were developed by the team in the third stage of the analysis with reference to the research question: what supports HCWs' resilience while working during a pandemic?

2.6. Reflexivity

The research team was made up of different clinical specialties, and career stages and thus brought different perspectives and experiences to this topic. DGF is the Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Limerick and retains a clinical role with the Irish public health service. HLR is a Principal Clinical Psychologist at a University Teaching Hospital. MC is a doctoral clinical psychologist in training. In attempts to eliminate any aspect of (MC) experience that could potentially influence the study, MC engaged in reflective journaling and regular supervision.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and characteristics

The final electronic search yielded 6205 articles. In total, 4247 studies remained after removing duplicate articles. Fig. 1 provides an overview of the selection process. All but one of the 121 included studies were cross-sectional studies. Data from 11,907 participants were included in the meta-synthesis. Fifty-six studies included a combination of HCWs, with 65 studies focusing on specific HCW groups. For studies that reported participant details, HCWs were both male and female and ranged in age from 20 to 69 years. Studies originated in 34 different countries. These were based across 6 continents including Africa (6 studies) Asia (51 studies), Australia/Oceania (5 studies), Europe (32 studies) North America (27 studies), and South America (1 study). For a full description of the included studies see Appendix C.

3.2. Quality of selected studies

A summary of results of the quality assessment of the included studies using CASP guidelines are shown in Table 1 (Checklist, 2018). Overall scores were not recorded, rather the focus was on individual quality elements to ensure the capture of individual study strengths and weaknesses (Wright, Brand, Dunn, & Spindler, 2007). The quality of studies varied, with the majority deemed to be of moderate quality. Individual scores are available in Appendix D in the supplementary data.

Table 1.

CASP Quality assessment of included studies.

| Totally met | Partially met | Not met | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 121 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 121 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 113 | 8 | 0 |

| 4 | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 74 | 46 | 1 |

| 5 | Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 103 | 18 | 0 |

| 6 | Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 29 | 43 | 49 |

| 7 | Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 70 | 50 | 1 |

| 8 | Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 97 | 21 | 3 |

| 9 | Is there a clear statement of findings? | 116 | 5 | 0 |

| 10 | How valuable is the research? | 109 | 12 | 0 |

3.3. Meta-synthesis findings

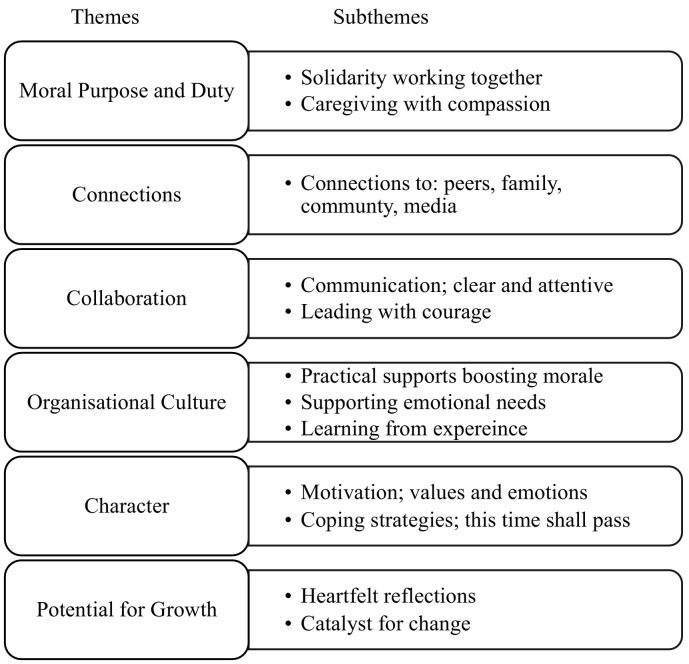

A thematic meta-synthesis was conducted yielding six main themes underpinning resilience (Fig. 2 ). See Appendix E in the supplementary data for how each included paper contributed to the development of each theme.

Fig. 2.

Overview of meta-synthesis themes and subthemes.

3.3.1. Theme 1: Moral purpose and Duty

This theme underlying resilience reflects a shared sense of moral purpose as HCWs strived to care for their patients. Studies reported a sense of professional identity, responsibility, and commitment not just to their profession but the patients for whom they cared.

3.3.1.1. Solidarity working together

HCWs joined together, worked hard, did what was necessary during pandemic outbreaks and displayed a sense of duty to their role. For example, in the case of nurses caring for patients during the Ebola outbreak; “Everyone has to take their own responsibility towards the society. If I, as a nurse, retreated from the threats of influenza, who is going to help the sick people? It is a feeling of mission calling. I am doing what I need to do…” (Lam & Hung, 2013). This was echoed by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic; “It's my duty to care for the sick.” (Gray, Dorney, Hoffman, & Crawford, 2021). Medical trainees felt that their role was much more than a job, expressing that it provided a sense of purpose and was the essence of their identity; “I think as part of the medical profession this is a very principle of why people are in medicine, whether you are a nurse or a doctor or a front desk clerk, you know, you choose this profession for a reason, and to be tested like this with SARS, it really rings true why medicine was once or even now considered by some people to be a noble profession … these are the sacrifices that you make and I take it as fundamental rather than an option” (Rambaldini et al., 2005). HCWs recognized their strengths as professionals while working during the COVID-19 pandemic; “I think as health professionals. People have a sense of duty…That's why they're there” (Baldwin & George, 2021). HCWs acknowledged fears during times of uncertainty but also displayed strength and courage in the face of adversity; “everyone had fears; how could they not?…But I still volunteered” (Ma et al., 2021). A clear moral and human purpose was evident; “We have only one mission, which is to fight the virus to the end, so that more families can be reunited. It was a unique sense of mission that belonged to the healthcare provider” (Liu et al., 2020). In addition, wartime narratives portrayed an alliance in a common effort against a great unknown during past pandemics; “This is Ebola, let's say this is a fight, we are fighting. You are the soldiers fighting a common enemy, an enemy which you don't know” (Jones et al., 2017). During COVID-19, a sense of mission was similarly likened to “going to war” and … “was a job that needed to be done” (Dopelt, Bashkin, Davidovitch, & Asna, 2021). HCWs reflected upon a heightened sense of role-meaning during COVID-19; it was viewed as a “vocation” (Stoichitoiu & Baicus, 2021), and “…exhausting but fulfilling’(Veerapen & McKeown, 2021). HCWs contributed a specific and meaningful skill set to society; “I feel it is an honor and a responsibility to the profession, to the country and generality of humanity at large” (Kwaghe et al., 2021). This sense of moral purpose may present as a source of resilience for HCWs.

3.3.1.2. Caregiving with compassion

A caring ethos represented HCWs personal nature, providing care to patients. They presented with profound levels of empathy for others. Despite their fears, HCWs were willing to provide care to patients described variously as “ethical love” and “caregiving with compassion” (Chiang, Chen, & Sue, 2007). Empathy was connected to individual values and their reasons for joining the profession. HCWs reported on “treating the patient, not just the disease” and sought to provide emotional support to their patients; “I comforted the patient while I gave the injection, [I told him] ‘Patients who were more serious finally recovered.’ I wanted to give him some hope and kept encouraging him, ‘We will not give up on you. You cannot give up on yourself either’… Then he felt better” (Liu et al., 2020). Empathy also extended to patients' family members; “I think that the physical and emotional presence of the nurses over the phone in times of crisis is important to family members because it demonstrates that someone cares about them and their relatives” (Chung, Wong, Suen, & Chung, 2005). HCWs appreciated acknowledgment from colleagues, patients and family; “make[s] it worth it, and bring[s] me some hope and motivation to keep going” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020). Patient gratitude may bolster one's resilience; “Patients bowed to us when they were discharged. Their actions of appreciation touched me, which energized me and made me have a great sense of achievement” (Zhang et al., 2020). HCWs felt respected and validated by those for whom they cared. Caring with compassion was met with gratitude, connecting a sense of meaning and purpose within a professional identity that may support resilience. The majority of studies reported in this theme are of Asian origin. While heterogeneity exits across these studies, eastern cultural based practice may influence how care is perceived as the self is often embedded in collectivist cultures. However, this sense of duty was observed across studies conducted worldwide.

3.3.2. Theme 2: Connections

This theme relates to various supports both formal and informal, within a hospital environment and wider community. Relationships that are supportive and collaborative while working within multidisciplinary environments, can provide formal and informal support protecting and encouraging resilience during a pandemic.

3.3.2.1. Connections to peers

Support from colleagues was the main source of support referred to by HCWs and was likened to a “healthcare family” (Akkus, Karacan, Guney, & Kurt, 2022).

Solidarity was noted among colleagues and comradery increased morale; “I felt warm in the team, and everyone was working together to fight against the disease” (Zhou et al., 2021). Peers were a source of emotional support and offered reassurance to one another (Abu Mansour & Abu Shosha, 2022). HCWs appreciated when colleagues asked how they were doing; “And people walk in all the time and ask, “How are you?”, “Is everything okay?” and “How are you feeling?” In that respect it is a reassuring experience (Belfroid et al., 2018). The cohesiveness was likened to “being in the same boat” (Chiang et al., 2007). HCWs highlighted the importance of “being able to meet and talk through it all and let off steam,”(Feeley et al., 2021). Where this occurred HCWs felt that “you are part of a group and everyone is all together, like a single fist, then that really gives you strength” (Dopelt et al., 2021). Similarly a buddy system for practical support in relation to PPE or completing ward rounds (Endacott et al., 2022), and well-being centres in UK hospitals to connect with peers and access support from colleagues trained in Psychological First Aid (PFA) (Blake et al., 2021) were viewed as positive resilience building approaches. Teamwork with “shared decision making” (Nowell, Dhingra, Andrews, & Jackson, 2021) was important as HCWs collaborated and pulled together. There was a shared sense of experience overcoming a common enemy and overcoming adversity; “We encouraged each other. It doesn't feel like I'm fighting alone, I'm not afraid” (Sun et al., 2020). Working together as a team was described as “very special” (Rucker et al., 2021). HCWs also highlighted the importance of “humour” within a “supportive team spirit” (Kranenburg et al., 2022). This team connection helped some HCWs to perceive the challenge of working during a pandemic in a positive way; “I have actually experienced some of my best moments as a nurse during this time” (Bergman, Falk, Wolf, & Larsson, 2021).

Peer relationships that are supportive, collaborative and create a sense of comradery may mitigate feelings of being overwhelmed. Staff cohesion reflected a collective sense of belonging among peers. New methods of communication during COVID-19 also aided connectedness; “that WhatsApp group I think probably literally saved people's lives….that was our wellness group right there” (Welsh, Chimowitz, Nanavati, Huff, & Isbell, 2021). This informal meaningful support may bolster individual resilience during a crisis.

3.3.2.2. Connections to family

Opportunities to connect with family and loved ones presented as a source of support to HCWs resilience. HCWs reported closer relationships with family members during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing for more meaningful time together (Aughterson, McKinlay, Fancourt, & Burton, 2021; Bender, Srinivas, Coutifaris, Acker, & Hirshberg, 2020; Hennein & Lowe, 2020; Veerapen & McKeown, 2021).

Some organizations had information for family members which was helpful. HCWs were also concerned for family members and often did not wish to worry their family and so limited sharing of work details; “I did not worry about myself; rather, I worried [about] my two kids and my elderly parents” (Shih et al., 2007). HCWs who were also parents required access to childcare to prevent individuals becoming “….overwhelmed. Overlooked between career job and motherhood” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020).

3.3.2.3. Connection to community

HCWs often received appreciation from their community in the form of food or letters of appreciation which offered encouragement during COVID-19 and previous pandemics. HCWs reported receiving supports from their local communities which gave them hope and felt like a “rise in respect” (Fadilioglu, Gurbuz, Yildiz, Aydin, & Aydin, 2021) This was described as “really touching” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020) as HCWs “appreciated the kindness” (LoGiudice & Bartos, 2021), and “warms the heart” (Marey-Sarwan, Hamama-Raz, Asadi, Nakad, & Hamama, 2021). HCWs reported feeling “proud” when community members adhered to public health guidelines; “The vast majority of people following social distancing, shelter-in- place and mask wearing recommendations. Makes me feel proud” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020). Community members following the recommended guidelines was viewed in solidarity with HCWs and that their efforts were not in vain and was thus supporting resilience.

3.3.2.4. Connections to media

Social media can be a source of connection with colleagues which can promote coping with challenges as some HCWs utilized during an outbreak (Raven, Wurie, & Witter, 2018). Positive stories reported in the media were also a source of optimism for HCWs. Support and hope can be effectively conveyed within the media; “Positive news stories about people pulling together to help and uplift others. Definitely raises your mood levels and gives you hope for the future” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020). This sub-theme also included managing media exposure, as information reported may become overwhelming and can increase anxiety. Indeed where disinformation regarding COVID-19 emerged through media channels, HCWs responded by posting accurate, scientific information such as “donning PPE” and guidance on how to wear the equipment (Akkus et al., 2022). Social connections with colleagues, loved ones, formal supports and the wider community that are maintained while physical distancing, supports a sense of being in this together while managing adversity.

3.3.3. Theme 3: Collaboration

This theme outlines the provision of reliable and consistent information and leadership shown by management that supported HCWs' resilience.

3.3.3.1. Communication; clear and attentive

The delivery of information and communication skills were crucial during a pandemic. HCWs required communication that was clear and consistent. A balance of information was also important in guiding HCWs' work and avoiding an overwhelming deluge of information (Mortensen, Zachodnik, Caspersen, & Geisler, 2022). Frequent updates provided by organizational managers was perceived as conducive to alleviating anxiety and increasing trust in health care systems during COVID-19 (Marey-Sarwan et al., 2021). Information that was delivered in a variety of forms including websites, e-mail, and direct communication via personal conversations or small group meetings and the veracity of the information provided by managers and the healthcare organization was most appreciated. “The administration was very truthful about the extent of knowledge, that was reassuring. The most important thing was the people were open to feedback, people were willing to talk about it, discuss it, and support others' ideas, so I think that was [more] important than a false sense of confidence” (Rambaldini et al., 2005). Daily emails that promoted transparency of the hospital response was positively viewed by HCWs and eased anxiety; “we're receiving emails from [administration] on a daily basis, I think they're very hands on, trying to stay ahead of this thing and just keeping everyone informed.” (Norful, Rosenfeld, Schroeder, Travers, & Aliyu, 2021). The type of information that HCWs required was also important. While information regarding infection control procedures and patient status was essential, people also required information that was relevant to their specific work; “I find daily emails with idiotic video tours of new hospital wards irrelevant; I want to know if I will be paid my usual hours when we get redeployed or go to a work from home roster” (Digby, Winton-Brown, Finlayson, Dobson, & Bucknall, 2021). HCWs wished to be consulted regarding the development of protocols that impacts their work on the ground. HCWs highlighted the need for consensus in decision making (Vazquez-Calatayud et al., 2022) and when this was done, they felt valued by their supervisors (Belfroid et al., 2018). Literature also highlighted HCWs' desire for information in order to better support the mental well-being of their patients. HCWs said that having a colleague appointed as a decision maker would be effective in reducing potential confusion. In addition, information delivered by colleagues, sensitively and in a supportive manner may ease underlying emotions such as fear and support resilience.

3.3.3.2. Leading with courage

The support provided by management that offered clear and compassionate leadership helped relieve stress and encourage resilience; “That was my first in-depth conversation with our director, which is unforgettable and makes me feel warm” (Zhang et al., 2020). Some HCWs positively valued the fact that their supervisors and medical specialists were more easily accessible than in normal situations. Most HCWs said that, in this exceptional situation, there was always someone available to answer their questions. Management that was physically present, visible, and available during shifts supported HWCs resilience and addressed concerns; “It meant a lot that they [the ward managers] were present in the department. They contributed to the good atmosphere and a feeling of community … you did not feel left alone” (Thude et al., 2021).

Some supervisors made themselves available at night to answer any staff queries (Belfroid et al., 2018). Visible and compassionate leadership was perceived to effectively address concerns and aid coping; “To be honest, I was very apprehensive before coming to the infectious department as support staff, but on the first day here, the head nurse personally explained relevant knowledge such as disinfection and quarantine, and that helped me calm down a lot” (Yin & Zeng, 2020). In addition, management that also encouraged HCWs' self-care may also increase healthy coping and foster resilience within a team; “my line manager believes that if we don't take good care of ourselves, we cannot take care of others. He supports self-care, which positively impacts our workplace culture.” (Kotera et al., 2022). The provision of clear guidance by effective and supportive leaders that is responsive to HCWs' needs served to reduce stress and may be essential in supporting resilience during a pandemic.

3.3.4. Theme 4: Organizational culture

The work environment theme outlines support on the front-line which reduced stress and supported resilience. Working in an environment that respects HCWs' roles, where there is flexible autonomy and where HCWs can provide necessary care to patients may be fertile ground for protecting and developing resilience.

3.3.4.1. Practical supports boosting morale

The maintenance of staffing levels was described as a major component in managing a crisis. While some studies revealed departments had necessary supports, others were not equipped to manage. Practical briefings and adequate time to prepare for the arrival of infected patients helped HCWs prepare mentally (Belfroid et al., 2018). The provision of training and education in relation to infectious diseases varied across studies. While many reported that training was helpful, many did not receive adequate training which is important for supporting resilience in HCWs and overcoming fear. Supporting staff to have the necessary skills may help staff cope in busy working environments. Training such as using PPE, respiratory equipment and how to care for patients was reported to strengthen HCWs' resilience. (Abu Mansour & Abu Shosha, 2022).

Across all data included in the review, the majority of studies reported upon training focused on preventing disease transmission, while just two studies focused on wellbeing training in the form of Psychological First Aid for HCWs (Blake et al., 2021) and “Resilience Coaching”(Rosen et al., 2022).‘Resilience Coaching’ which was offered directly on a hospital unit felt “…like an acknowledgement” from the hospital in recognising the difficulty of the situation and the need to support the mental health of HCWs. This included opportunities to learn about coping, for example lanyard cards with relaxation tips; “[my coach] made these cards available, and the uptake of that card was immediate, which to me was a sign that people…[are] trying to find ways to do even better” (Rosen et al., 2022).

While wearing PPE presented difficulties such as being “hot and heavy” (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020), sufficient, appropriate PPE was a major priority for HCWs to ensure safety and well-being: “Availability of PPEs, masks, gloves, all these gave us a feeling of support and increased our resilience…”(Khatatbeh et al., 2021). It was noted that allowing breaks every two hours while wearing PPE was effective in preventing dehydration (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020). PPE portraits, which are postcard-sized face portraits printed and affixed to PPE as stickers or laminated badges, was piloted in Africa during the Ebola crisis as a creative means to overcome emotional and physical barriers. Reidy et al. (2020) survey found that PPE portraits increased provider well-being and enhanced meaningful connection; “seeing a professional with PPE portrait improved my mood and made me smile…. PPE portrait of the professional helped me feel more connected to the person behind the mask” (Reidy et al., 2020). Safety was an important factor for HCWs which included following necessary hygiene procedures. Wong, Wong, Lee, Cheung, and Griffiths (2012) reported that on learning from SARS, HCWs felt they could negate the risk of infection by employing the appropriate hygiene practice, e.g. hand washing before and after taking care of patients, showering before going home after duty. Such hygiene practices were integral to their working environment and were done without question (Missel, Bernild, Dagyaran, Christensen, & Berg, 2020). These safety procedures may aid HCW resilience. When others, such as patients also followed safety procedures, staff felt safer when facilitating care; “every time I take care of the patients, they will take the initiative to put on a mask. I feel particularly safe in my heart…” (Sun et al., 2020). Receiving hazard pay left some HCWs feeling “acknowledged” (Hennein & Lowe, 2020), while for others monetary rewards did not adequately address the challenge faced; “I just accepted it because they gave it to me, but it could never be a good way to attract people because the value of the reward was too small. Who would work for infectious patients for an extra 100 dollars per day? It was a voluntary service” (Kim, 2018).

HCWs felt that a pandemic highlighted the shortcomings in health care. While recognition from society was appreciated, some expressed that genuine societal recognition would be reflected in more resources in hospitals and an improved salary (Missel et al., 2020). Universal testing was important in reducing anxiety, providing hope in overcoming the virus and aiding resilience; “the universal testing makes me feel safer doing my job” (Bender et al., 2020). Adequate breaks were a necessary means of coping in a busy work environment with “a place to chat to my colleagues, to sit and eat lunch safely and in company” (Digby et al., 2021). In some cases, HCWs received a day off which was appreciated, however, they preferred to choose when they could take their day (Wong et al., 2012). In some services food was provided which was greatly appreciated and contributed to boosting team morale (Corley, Hammond, & Fraser, 2010). It appears that when HCWs feel valued and receive recognition, such as the provision of practical and meaningful real world supports, that this may have a positive impact upon HCW resilience.

3.3.4.2. Supporting emotional needs

Formal psychological supports included individual and group counselling, videos, on-line resilience resources, or a mental health hotline. Informal supports included relaxation areas and well- being groups. Some HCWs felt that having access to counselling services and debriefing sessions was a useful approach in managing work-related stress and anxiety; “just to offload everything was… really helpful, and hearing other people that had felt the same about things, it was reassuring in a way” (Nowell et al., 2021). While psychological supports may be offered to support well-being and resilience, HCWs noted they may not always be accessible for staff; “part of the problem for the official support, there is a psychologist who's offering sessions, but they are in the middle of the day. So, you wouldn't be able to go if you were on nights, or if you are clinically busy you can't really attend that in the middle of the shift” (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020). COVID-19 wellbeing centers ran by staff known as “wellbeing buddies” who were trained in PFA were viewed as a “critical” and “essential” support strategy for HCWs (Blake et al., 2021). The wellbeing centers were described as an “oasis of calm” where HCWs could take time-out or access emotional support from a “wellbeing buddy” (Blake et al., 2021). Studies also highlighted that some HCWs felt that supports were directed for front-line workers or that they felt formal support was not immediately required.

3.3.4.3. Learning from experience

Organizations and individuals who worked with previous outbreaks such as SARS, felt better prepared when working with further outbreaks such as H1N1; “When H1N1 ah, came about, I really do not have any fear. I still believe it will be contained eventually, you know?… Because based on the SARS experience… we are at a higher level of preparedness” (Koh, Hegney, & Drury, 2012). Regarding preparedness and clear guidance, during the H1N1 pandemic, Wong et al. (2012) reported that communication and support from senior management was superior to the SARS period. Similarly, individuals became familiar and adapted to working with a novel virus over time which eased stress and fostered resilience; “After a few nights, when I was changing my clothes, my new buddy said, “Huh, aren't you nervous?” But it just becomes sort of a routine” (Belfroid et al., 2018). During the COVID-19 pandemic HCWs adapted to the evolving situation over time, reflecting upon their “learning as we go” (Endacott et al., 2022). HCWs grew in confidence over time as they became more familiar with the disease which promoted their inner strength; “This feeling (fear and stress) began to fade with time, as I became more familiar with the disease…” (Khatatbeh et al., 2021). Overall, these resilience-promoting strategies within the work environment must first meet HCWs' basic needs, enabling safety and protecting HCWs mental well-being.

3.3.5. Theme 5: Character

This theme describes individual characteristics such as their core values, range of emotions experienced and individual strategies that helped them cope and promoted resilience in the face of challenges.

3.3.5.1. Motivation; values and emotions

The recognition and importance of patient care may be underpinned by individuals' values that may be tied to their sense of professional identity; “I think it just an honor to do something for the nation. You feel like you are part of something bigger than yourself” (Goh et al., 2020). HCWs experienced a variety of emotions while working during a pandemic. Emotions such as powerlessness, fear, anxiety or frustration may be considered in most cases as normal reactions to a stressful situation and seemed to precede or co-exist with positive emotions across studies.

Pride was the predominant positive emotion supporting resilience experienced by HCWs. Studies reported HCWs felt proud of their work and contributed enormously to society during such stressful times; “We feel proud of being the front-line fighters against this illness” (Urooj, Ansari, Siraj, Khan, & Tariq, 2020). The experience of positive emotions, such as pride, may contribute to individual psychological resilience, whereby greater positive emotions aid coping. Upon the most rewarding aspects, HCWs reported joy at seeing patients improve (Smith, Smith, Kratochvil, & Schwedhelm, 2017). Another important emotion related to resilience was hope in overcoming challenges faced by the pandemic; “Our nation has experienced so many difficulties and finally won. Some experts said that we were the heroic people of Wuhan. I believed this time we would succeed” (Liu, Zhai, et al., 2020). Studies also highlighted hope in overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic; “Won't the COVID-19 situation be over some time down the road? Without hope, how can we live today?” (Kim & Kim, 2021). HCWs reflected upon their “necessary and meaningful” work (Zhou et al., 2021) which was empowering and supported resilience; “the frontline work helps me realise my value of being a nurse. Also, my nursing career will embed something memorable and meaningful” (Ke et al., 2021).

3.3.5.2. Coping strategies; this time shall pass

Time away from work was important for HCWs to engage in successful coping to support resilience. “To keep up with the workload, the most important thing after work is to eat and sleep to replenish strength” (Liu, Luo, et al., 2020) and exercising; “I now practice yoga and do aerobic exercises every day…” (Yin & Zeng, 2020).

Healthy lifestyle behaviors promoting physical health can be viewed as an element of resilience. Coping also included engaging in mindfulness; “Mindfulness is a useful tool. I have been using this strategy for some time…” (Digby et al., 2021) and positive self-statements while on the job; “This time shall pass” (Urooj et al., 2020).

Faith based coping was seen to play an important role for some individuals who held a high regard for their religious values. Some HCWs incorporated prayer into their working shift; “starting the duty with prayer helps a lot to cope with stress”(Feeley et al., 2021). Faith based coping was particularly highlighted in studies based in Asia and the Middle East. This reflected a difference in coping compared with Western cultures where religious coping was emphasized far less as a means of supporting resilience.

3.3.6. Theme 6: Potential for growth

This final theme encapsulated data relating to HCWs' new perspectives and experiences of growth both personally and professionally. Finding meaning was important for HCWs who were committed to their roles for the “greater good” (Liu & Liehr, 2009). There was a perception that new skills were mastered which contributed to their practice having worked through difficult situations which may strengthen their resilience in future situations.

3.3.6.1. Heartfelt reflections

HCWs reflected on their personal experiences of growth; “… I got exhausted and annoyed many times, but I didn't give up. I told myself all the time, “I have to overcome and I can do it.” This made me very zealous. Now, I can work calmly and courageously in emergency situations” (Kim, 2018). Studies highlighted that upon reflection some HCWs began to consider what was important to them; “I will spend more time learning in the future. I will not waste time any longer. Now, I want to learn from my heart” (Liu & Liehr, 2009) and “…to cherish life and live in the moment.” (Yin et al., 2022). Such reflection may bring clarity of what is in one's control, helping to regulate and support resilience during adversity. Individuals reflected upon their own strength; “I never thought I could be so strong” (Sun et al., 2020). The importance of being present in the moment was highlighted by HCWs who were; “learning to appreciate even smaller things such as “waking up early and watching the sunrise (Araujo, Siqueira, & Amaral, 2022) or that “being alive should not be taken for granted any more. Now, I will never miss any chance to say nice things about my neighbors to their face, in case I don't meet them again during my life. I do not want my life filled with regret and bad feelings before my death” (Chiang et al., 2007). HCWs felt that experiences during COVID-19 helped them to appreciate what they have in life; “…I realized the value of what I have” (Cengiz, Isik, Gurdap, & Yayan, 2021) and were motivated to carry these new learnings forward; “I will become more grateful. Without these experiences, I may not know how lucky and happy I am.” (Xu et al., 2021).

3.3.6.2. Catalyst for change

HCWs were determined to provide the best to their patients, to keep an open mind and draw upon previous clinical experience; “We try to deeply understand the guidelines released by the country, discuss with other colleagues to know their experiences in treating patients with COVID-19, then transform the knowledge and experience to use for our patients. We keep exploring” (Liu, Luo, et al., 2020). Such new experiences promoted a change in perspective and appreciation was paid to the “little things”; “I didn't realize that simply having a chance to talk to family members was so important until I handed the wireless phone to an old patient aged 75 to talk to his wife… it was unbelievable how his oxygen saturation improved afterwards” (Chung et al., 2005). Opportunities for learning was highlighted by HCWs across studies; “this new disease has increased our existing knowledge, specifically on how to deal with a pandemic” (Ali, Sadique, & Ali, 2021), and that “wisdom comes with the virus” (Fadilioglu et al., 2021). Working during a pandemic was also described as a “catalyst for changes” (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020) which HCWs hoped to continue to use in their roles. This theme of the potential for personal and professional growth highlights the remarkable adaptability and resilience of individuals as HCWs became more present, considered what was important and learned new skills.

4. Discussion

This systematic review of 121 qualitative studies involving 11,907 participants thematically synthesized experiences of resilience among HCWs working during a pandemic. Meta-synthesis revealed six key interconnected themes namely; moral purpose and duty, connections, collaboration, organizational culture, character and potential for growth. Despite adversity, HCWs positively adapted and in some studies reported that they developed and grew in their personal lives and professional practice. This was aided by positive social connections, communication, leadership, supportive working environments in the provision of practical supports and individual characteristics such as the experience of positive emotions.

The meta-synthesis showed that HCWs presented with a strong sense of duty, which pertained to their sense of professional identity and responsibility as health care providers. In the face of challenges, whether HCWs were working in the context of SARS, H1N1, MERS, Ebola or COVID-19, the research reviewed suggested that HCWs relied principally on their colleagues for support, which has been recommended as a strategy for team cohesion (Billings et al., 2020). Social support is a key mediator of resilience and is positively associated with active problem-focused coping and a sense of control (Southwick & Charney, 2012). Meaningful connections may also be associated with enhanced immune function which may be particularly important while working during a pandemic (Southwick & Charney, 2012). The wider community also presents as an aid to potential resilience in terms of social support and sense of connections, which perhaps is embedded and expressed differently within specific cultures (Rosenberg, 2020). Irrespective of the individual culture or geography, communal support, which may be expressed in the form of practical supports or in the observation of other members of that society adhering to government-recommended health guidelines, may benefit HCWs' resilience.

In terms of organizational factors, the studies reviewed clearly highlighted the need for effective communication with managers and among staff teams while working during a pandemic. HCWs reported that their well-being was supported by working environments where their viewpoints were considered and where they were involved in decision making processes. Leadership and supportive management were viewed as important along with proficient training to enable fulfilment of their roles and aid resilience. These results are in line with an increasing body of work highlighting the importance of psychologically minded managers (Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin, & Greenberg, 2018; Greenberg et al., 2021) in relation to supporting staff well-being. Resilience promoting strategies within the work environment include clear guidance, acknowledgement of uncertainty and the provision of access to mental health supports (Albott et al., 2020).

Studies captured various coping strategies employed by HCWs to retain resilience. Effective coping strategies as highlighted by Heath et al. (2020), including maintaining sleep quality, mindfulness practice, meaningful relationships (both personally and professionally), were evident among participants ways of coping in the included studies. Similarly HCWs who maintained positive emotions through social interactions with others during COVID-19 reported positive overall mental health (Prinzing et al., 2021). There were some possible geographical and cultural differences observed, with studies conducted in Asia and the Middle East more likely to include faith-based coping as a means of fostering resilience, compared with studies conducted in Western cultures. Of course, many of the ways HCWs in Western cultures described their experiences which included references to hope, reflection, empathy and compassion could be considered to have a resonance with more spiritual or faith-based aspects of experience. Whether this may represent a more universal feature of resilience that may transcend geography and culture is unfortunately beyond the data that we could access for this review.

Reflection and the observed positive reinterpretation of challenges as outlined in theme 6 may serve to foster adaptive flexibility and aid resilience in individuals (Wald, 2015). Within the meta-synthesis some studies revealed positive emotional experiences such as finding benefits within adversity, that were important to well-being. Positive emotions not only included pride, joy and optimism but also empathy and gratitude as referenced within the included studies. Self-transcendent emotions of compassion, gratitude and awe are described as encouraging individuals to transcend their own immediate needs and desires to focus on the welfare of others (Stellar et al., 2017). While there was some evidence of participants construing their experiences in terms of personal growth, it is acknowledged that given that participants in the included studies were interviewed while their pandemics were active, it is unclear if the time from the event was sufficient to create the necessary conditions for post traumatic growth. Nonetheless, there has been some welcome discussion on the nature of pandemic-induced growth experiences in HCWs (Batra, Singh, Sharma, Batra, & Schvaneveldt, 2020; Feingold et al., 2022).

4.1. Implications for practice

Several implications for practice in supporting HCWs' resilience may be derived from the findings of the current systematic review. It is important that HCW well-being is prioritized, including that basic needs are addressed, such as access to necessary PPE. Research suggests that it is important that peer networks are maintained and supported during a pandemic. The presence of organizational leaders on the ground was viewed by participants as helpful for addressing concerns and supporting their well-being. Leadership plays a central role where reliable, timely and consistent communication from leaders that are open to feedback aids resilience and, is supported by findings of the review. Furthermore, where possible, it is important that HCWs are included in the decision-making process, particularly where such decisions may impact their specific role and well-being. This research review also suggests that paying attention to the context that supports and enables HCWs to engage in helpful coping practices may support their mental health and resilience. This may potentially reduce the burden on mental health services. In addition, by supporting HCWs' well-being, vital service delivery may be maintained during a pandemic.

4.2. Methodological issues

There are a number of key strengths of this study including that the data synthesis incorporated studies from past pandemics and considered individual, organizational and societal influences on resilience, and included a diversity of health professionals in the studies included in this review. It is acknowledged that this research is targeted for HCWs based within a hospital setting and may not be generalizable to wider HCWs' community environments. While original data was used based upon the aims of the current review, and we included formal measures of bias in the review's design, we cannot exclude the possibility of potential bias in interpretations from original study authors. In order to reduce the potential bias, this would have necessitated direct use of the original transcripts which was not possible in the current study. The included studies were non-homogenous as they had somewhat different research questions, aims, and used different methodological approaches and varying inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, all included studies were in the English language. The pandemics discussed in this review disproportionality affected non-English speaking cultures, and therefore, the included studies may not sufficiently reflect discrete cultural experiences of pandemics at specific time points or pandemic waves.

5. Conclusion

This meta-synthesis provided a comprehensive in-depth review of qualitative data considering the experience of resilience among HCWs during a pandemic. Themes of moral purpose and duty, connections with others, collaboration with leaders providing necessary communication, the culture of the work environment, characteristics of the individual, and potential for growth highlight areas of experience that may prove important in supporting resilience. It is axiomatic that HCWs may experience psychological distress while working during COVID-19. The results of this thematic synthesis may have relevance for current and future pandemics, and may help to focus attention on the likely ways in which resilience can be fostered at the individual, the organizational, and the community/contextual level for HCWs.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Health Research Board Ireland (COV19–2020-042). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Authors contributions

DGF and HLR conceptualized the study, and secured funding for the study. All authors contributed to the protocol. MC conducted literature searches. All authors contributed to the data screening and analysis. MC wrote the initial first draft of the manuscript and all authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors (MC, HLR, DGF) declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102173.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Abu Mansour S.I., Abu Shosha G.M. Experiences of first-line nurse managers during COVID-19: A Jordanian qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2022;30(2):384–392. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkus Y., Karacan Y., Guney R., Kurt B. Experiences of nurses working with COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2022;31(9–10):1243–1257. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albott C.S., Wozniak J.R., McGlinch B.P., Wall M.H., Gold B.S., Vinogradov S. Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2020;131(1):43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Sadique S., Ali S. Doctors dealing with COVID-19 in Pakistan: Experiences, perceptions, fear, and responsibility. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.647543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo C., Siqueira M., Amaral L. Resilience of Brazilian health-care professionals during the pandemic. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences. 2022 doi: 10.1108/ijqss-08-2021-0111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aughterson H., McKinlay A.R., Fancourt D., Burton A. Psychosocial impact on frontline health and social care professionals in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S., George J. Qualitative study of UK health professionals' experiences of working at the point of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra K., Singh T.P., Sharma M., Batra R., Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(23):9096. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17239096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfroid E., van Steenbergen J., Timen A., Ellerbroek P., Huis A., Hulscher M. Preparedness and the importance of meeting the needs of healthcare workers: A qualitative study on Ebola. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2018;98(2):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W.R., Srinivas S., Coutifaris P., Acker A., Hirshberg A. The psychological experience of obstetric patients and health care workers after implementation of universal SARS-CoV-2 testing. American Journal of Perinatology. 2020;37(12):1271–1279. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman L., Falk A.C., Wolf A., Larsson I.M. Registered nurses’ experiences of working in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing in Critical Care. 2021;26(6):467–475. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings J., Greene T., Kember T., Grey N., El-Leithy S., Lee D.…Brewin C.R. Supporting hospital staff during COVID-19: Early interventions. Occupational Medicine. 2020;70(5):327–329. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake H., Gupta A., Javed M., Wood B., Knowles S., Coyne E., Cooper J. COVID-well study: qualitative evaluation of supported wellbeing centres and psychological first aid for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3626. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdağ F., Ergün N. Psychological resilience of healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Reports. 2020;124(6):2567–2586. doi: 10.1177/0033294120965477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S., Amlôt R., Rubin G., Greenberg N. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: Overview of the literature. BMJ Military Health. 2020;166(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2017-000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Dunn R., Amlôt R., Rubin G.J., Greenberg N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2018;60(3):248–257. doi: 10.1097/JOM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi C., Foghi C., Dell’Oste V., Cordone A., Bertelloni C.A., Bui E., Dell’Osso L. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz Z., Isik K., Gurdap Z., Yayan E.H. Behaviours and experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: A mixed methods study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2021;29(7):2002–2013. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checklist C.Q. Critical appraisal skills programme. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf URL.

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang H.-H., Chen M.-B., Sue I.-L. Self-state of nurses in caring for SARS survivors. Nursing Ethics. 2007;14(1):18–26. doi: 10.1177/0969733007071353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung B.P.M., Wong T.K.S., Suen E.S.B., Chung J.W.Y. SARS: Caring for patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(4):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47(5):577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeTore N.R., Sylvia L., Park E.R., Burke A., Levison J.H., Shannon A.…Holt D.J. Promoting resilience in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic with a brief online intervention. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2022;146:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digby R., Winton-Brown T., Finlayson F., Dobson H., Bucknall T. Hospital staff well-being during the first wave of COVID-19: Staff perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2021;30(2):440–450. doi: 10.1111/inm.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopelt K., Bashkin O., Davidovitch N., Asna N. Facing the unknown: healthcare workers’ concerns, experiences, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic—A mixed-methods study in an Israeli hospital. Sustainability. 2021;13(16) doi: 10.3390/su13169021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endacott R., Pearce S., Rae P., Richardson A., Bench S., Pattison N., Team S.S. How COVID-19 has affected staffing models in intensive care: A qualitative study examining alternative staffing models (SEISMIC) Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2022;78(4):1075–1088. doi: 10.1111/jan.15081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadilioglu K., Gurbuz E., Yildiz N., Aydin O., Aydin E.T. Extraordinary days, unusual circumstances: Psychosocial effects of working with COVID-19 patients on healthcare professionals. Anaesthetics Pain & Intensive Care. 2021;25(3):349–358. doi: 10.35975/apic.v25i3.1515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeley T., Ffrench-O’Carroll R., Tan M.H., Magner C., L’Estrange K., O’Rathallaigh E.…O’Connor E. A model for occupational stress amongst paediatric and adult critical care staff during COVID-19 pandemic. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2021;94(7):1721–1737. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01670-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold J.H., Hurtado A., Feder A., Peccoralo L., Southwick S.M., Ripp J., Pietrzak R.H. Posttraumatic growth among health care workers on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;296:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher D., Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist. 2013;18(1):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goh Y.S., Ow Yong Q.Y.J., Chen T.H.M., Ho S.H.C., Chee Y.I.C., Chee T.T. The impact of COVID-19 on nurses working in a university health system in Singapore: A qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2020;30(3):643–652. doi: 10.1111/inm.12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Dorney P., Hoffman L., Crawford A. Nurses' pandemic lives: A mixed-methods study of experiences during COVID-19. Applied Nursing Research. 2021;60 doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N., Weston D., Hall C., Caulfield T., Williamson V., Fong K. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occupational Medicine. 2021;71(2):62–67. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath C., Sommerfield A., von Ungern-Sternberg B.S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364–1371. doi: 10.1111/anae.15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennein R., Lowe S. A hybrid inductive-abductive analysis of health workers’ experiences and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton C., Meskell P., Delaney H., Smalle M., Glenton C., Booth A.…Biesty L.M. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: A rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013582. Art No: CD013582. Accessed 01/08/2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D., Firtko A., Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Sam B., Bull F., Pieh S.B., Lambert J., Mgawadere F.…van den Broek N. ‘Even when you are afraid, you stay’: Provision of maternity care during the Ebola virus epidemic: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2017;52:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q., Chan S.W., Kong Y., Fu J., Li W., Shen Q., Zhu J. Frontline nurses’ willingness to work during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2021;77(9):3880–3893. doi: 10.1111/jan.14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatatbeh M., Alhalaiqa F., Khasawneh A., Al-Tammemi A.B., Khatatbeh H., Alhassoun S., Al Omari O. The experiences of nurses and physicians caring for COVID-19 patients: Findings from an exploratory phenomenological study in a high case-load country. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(17) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim S. Nurses’ adaptations in caring for COVID-19 patients: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(19) doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control. 2018;46(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine A.K., Rudolph C.W., Zacher H. Thriving at work: A meta analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2019;40(9–10):973–999. [Google Scholar]

- Koh Y., Hegney D., Drury V. Nurses’ perceptions of risk from emerging respiratory infectious diseases: A Singapore study. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2012;18(2):195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotera Y., Ozaki A., Miyatake H., Tsunetoshi C., Nishikawa Y., Kosaka M., Tanimoto T. Qualitative Investigation into the mental health of healthcare workers in Japan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(1) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg L.W., de Veer M.R., Oude Hengel K.M., Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij T.A., de Pagter A.P., Hoogendijk W.J.…van Mol M.M. Need for support among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study at an academic hospital in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwaghe A.V., Kwaghe V.G., Habib Z.G., Kwaghe G.V., Ilesanmi O.S., Ekele B.A.…Balogun M.S. Stigmatization and psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on frontline healthcare Workers in Nigeria: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):518. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03540-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachal J., Revah-Levy A., Orri M., Moro M.R. Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2017;8:269. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J., Du H., Chen T., Li R. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K.K., Hung S.Y.M. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: A qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing. 2013;21(4):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.H., Cranford J.A. Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors?: A study of Korean adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Liehr P. Instructive messages from Chinese nurses’ stories of caring for SARS patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(20):2880–2887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Luo D., Haase J.E., Guo Q., Wang X.Q., Liu S.…Yang B.X. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6):e790–e798. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.E., Zhai Z.C., Han Y.H., Liu Y.L., Liu F.P., Hu D.Y. Experiences of front-line nurses combating coronavirus disease-2019 in China: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nursing. 2020;37(5):757–763. doi: 10.1111/phn.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoGiudice J.A., Bartos S. Experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2021;32(1):14–26. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2021816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R., Oakman J.M., Zhang M., Zhang X., Chen W., Buchanan N.T. Lessons for mental health systems from the COVID-19 front line: Chinese healthcare workers’ challenges, resources, resilience, and cultural considerations. Traumatology. 2021;27(4):432–443. doi: 10.1037/trm0000343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marey-Sarwan I., Hamama-Raz Y., Asadi A., Nakad B., Hamama L. "It's like we're at war": Nurses' resilience and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Inquiry. 2021 doi: 10.1111/nin.12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel M., Bernild C., Dagyaran I., Christensen S.W., Berg S.K. A stoic and altruistic orientation towards their work: A qualitative study of healthcare professionals’ experiences of awaiting a COVID-19 test result. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05904-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen C.B., Zachodnik J., Caspersen S.F., Geisler A. Healthcare professionals’ experiences during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 2022;68 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R.A.E., Stensland R.S.Ø., van de Velde R.S. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293:113441. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441. Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norful A.A., Rosenfeld A., Schroeder K., Travers J.L., Aliyu S. Primary drivers and psychological manifestations of stress in frontline healthcare workforce during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2021;69:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L., Dhingra S., Andrews K., Jackson J. A grounded theory of clinical nurses’ process of coping during COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo Q. QSR International Ltd.; 2022. Qualitative data analysis software. [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data Retrieved 17/05/2022 from. 2021. https://ourworldindata.org

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D.…Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;134:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Barnett J., Berges I., Sakkas N. Tired, worried and burned out, but still resilient: A cross-sectional study of mental health workers in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(9):4457. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A., Campbell P., Cheyne J., Cowie J., Davis B., McCallum J.…McClurg D. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: A mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. Issue 11, Art No. CD013778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzing M.M., Zhou J., West T.N., Le Nguyen K.D., Wells J.L., Fredrickson B.L. Staying ‘in sync’ with others during COVID-19: Perceived positivity resonance mediates cross-sectional and longitudinal links between trait resilience and mental health. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1858336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaldini G., Wilson K., Rath D., Lin Y., Gold W.L., Kapral M.K., Straus S.E. The impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on medical house staff: A qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(5):381–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J., Wurie H., Witter S. Health workers’ experiences of coping with the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone’s health system: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3072-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy J., Brown-Johnson C., McCool N., Steadman S., Heffernan M.B., Nagpal V. Provider perceptions of a humanizing intervention for health care workers—A survey study of PPE portraits. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020;60(5):e7–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckert A., Schuit E., Bleijenberg N., Ten Cate D., de Lange W., de Man-van Ginkel J.M., Trappenburg J.C. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B., Preisman M., Read H., Chaukos D., Greenberg R.A., Jeffs L.…Wiesenfeld L. Resilience coaching for healthcare workers: Experiences of receiving collegial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2022;75:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A.R. Cultivating deliberate resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020;174(9):817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker F., Hardstedt M., Rucker S.C.M., Aspelin E., Smirnoff A., Lindblom A., Gustavsson C. From chaos to control - experiences of healthcare workers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus group study. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1):1219. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07248-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(2):335–344. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih F.-J., Gau M.-L., Kao C.-C., Yang C.-Y., Lin Y.-S., Liao Y.-C., Sheu S.-J. Dying and caring on the edge: Taiwan's surviving nurses' reflections on taking care of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Applied Nursing Research. 2007;20(4):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbrandij M., Horn R., Esliker R., O’may F., Reiffers R., Ruttenberg L.…Ager A. The effect of psychological first aid training on knowledge and understanding about psychosocial support principles: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(2):484. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.W., Smith P.W., Kratochvil C.J., Schwedhelm S. The psychosocial challenges of caring for patients with Ebola virus disease. Health Security. 2017;15(1):104–109. doi: 10.1089/hs.2016.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick S.M., Charney D.S. The science of resilience: Implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science. 2012;338(6103):79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1222942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar J.E., Gordon A.M., Piff P.K., Cordaro D., Anderson C.L., Bai Y.…Keltner D. Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review. 2017;9(3):200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Stoichitoiu L.E., Baicus C. COVID-19 pandemic preparedness period through healthcare workers’ eyes: A qualitative study from a Romanian healthcare facility. PLoS One. 2021;16(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]