Abstract

The arrangement of the genes involved in o-xylene, m-xylene, and p-xylene catabolism was investigated in three Pseudomonas stutzeri strains: the wild-type strain OX1, which is able to grow on o-xylene but not on the meta and para isomers; the mutant M1, which grows on m-xylene and p-xylene but is unable to utilize the ortho isomer; and the revertant R1, which can utilize all the three isomers of xylene. A 3-kb insertion sequence (IS) termed ISPs1, which inactivates the m-xylene and p-xylene catabolic pathway in P. stutzeri OX1 and the o-xylene catabolic genes in P. stutzeri M1, was detected. No IS was detected in the corresponding catabolic regions of the P. stutzeri R1 genome. ISPs1 is present in several copies in the genomes of the three strains. It is flanked by 24-bp imperfect inverted repeats, causes the direct duplication of 8 bp in the target DNA, and seems to be related to the ISL3 family.

Aromatic-hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria often display remarkable metabolic versatility due to the broad range of substrates of the catabolic enzymes. This low substrate specificity allows bacteria to degrade related molecules through the same catabolic pathway. This is the case for toluene, m-xylene, and p-xylene, which are normally metabolized through the progressive oxidation of a methyl group leading to the formation of a methylbenzoic acid (TOL upper pathway), which is further converted to a (methyl)catechol (9). However, catabolic enzymes have limitations with regard to their substrate range. For instance, o-xylene cannot be degraded through the TOL upper pathway, as ortho-substituted toluene derivatives cannot act as substrates for xylene monooxygenase, the first enzyme of this route (41). A few exceptions—in which o-xylene is converted to 2-methylbenzyl alcohol and then to 2-methylbenzoate—are known, but there is no clear evidence that this pathway supports growth (2, 8).

Further metabolic versatility can be achieved through the acquisition of catabolic transposons carrying the genetic information for novel pathways (35, 42). Also, insertion sequences (ISs) can contribute to bacterial metabolic versatility, causing genomic rearrangements that may lead to the expression of genes that are otherwise silent (35).

Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 is able to grow on toluene or o-xylene as the sole carbon and energy source (3). The first step of the catabolism of these compounds consists of the hydroxylation of the aromatic ring (TOU pathway, for toluene/o-xylene utilization) catalyzed by the enzymatic complex of the toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase (6, 7). m-Xylene and p-xylene are not used for growth by P. stutzeri OX1, but they are cometabolized through toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase to intermediates unproductive for growth (4, 6) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, from P. stutzeri OX1 cultures, we isolated spontaneous mutants which had acquired the ability to grow on m-xylene and p-xylene through the TOL pathway but which lost the ability to utilize the ortho isomer (4) and, successively, revertants endowed with both catabolic pathways and able to grow on all three isomers of xylene were isolated (11) (Fig. 1).

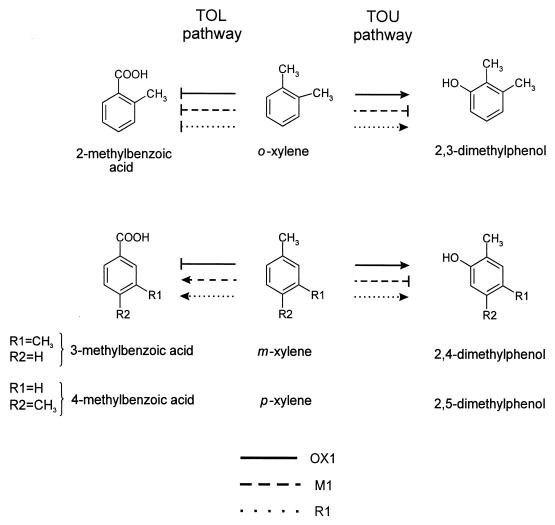

FIG. 1.

Transformations of ortho-, meta-, and para-xylene in P. stutzeri OX1, M1, and R1 via the TOL or the TOU pathway. Solid, dashed, or dotted lines that end with vertical lines rather than arrowheads indicate that the transformation does not occur. P. stutzeri OX1 and R1 grow on o-xylene, and the first catabolic step consists of the monooxygenation of the aromatic nucleus. Both strains cometabolize m-xylene and p-xylene to give the corresponding dimethylphenols, which are not used for further growth. P. stutzeri M1 and R1 grow on m-xylene and p-xylene, whose catabolism proceeds through the progressive oxidation of a methyl group. P. stutzeri M1 is unable to grow on o-xylene and does not produce dimethylphenols from any xylene isomer. None of the three strains is able to oxidize a methyl group of o-xylene. See the text for further details and references.

In this study, we set out to determine the events which switch these catabolic pathways on and off.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and general procedures.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Pseudomonas cultures were routinely grown at 30°C, and Escherichia coli cultures were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium. For selective medium, ampicillin was added at 100 μg/ml and tetracycline was added at 25 μg/ml. Induction of the lac promoter of plasmids based on pUC19 was performed by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. E. coli cells were transformed with plasmid DNAs by electroporation (12). Plasmid preparations and all the DNA manipulations were carried out in E. coli JM109 by following standard procedures (32).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 thi relA1 Δ(lac-proAB) F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacIqZΔM15) | 43 |

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 18 |

| P. stutzeri | ||

| OX1 | o-Xyl+m-Xyl−p-Xyl− | 3 |

| M1 | o-Xyl−m-Xyl+p-Xyl+; OX1 spontaneous mutant | 4 |

| R1 | o-Xyl+m-Xyl+p-Xyl+; M1 spontaneous revertant | 11 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFB3401 | Tcr; pLAFR1 derivative; contains the genes for the conversion of o-xylene into the corresponding ring fission products | 6 |

| pBZ2035 | Apr; subcloning of the pFB3401 3.5-kb EcoRI fragment into pGEM3Z; contains touA and touB | 6 |

| pED3306 | Apr; pBR322 derivative; contains the pWW0 xyl upper pathway genes in a 9.8-kb HindIII fragment | 28 |

| pUC19 | Apr; cloning vector | 37 |

| pFC3095 | Apr; 9.5-kb EcoRI fragment from P. stutzeri M1 cloned in pUC19 | This work |

| pGEM3Z | Apr; cloning vector | Promega |

| pFC1965 | Apr; 6.5-kb EcoRI fragment from P. stutzeri M1 cloned in pGEM3Z | This work |

| pFC4037 | Apr; 3.7-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment from P. stutzeri OX1 cloned in pGEM3Z | This work |

Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin; Tc, tetracycline; o-Xyl, o-xylene; m-Xyl, m-xylene; p-Xyl, p-xylene.

Southern analyses.

Genomic DNA from Pseudomonas cultures was extracted by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method and purified by CsCl gradient (32). After digestion, DNA fragments were transferred to Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham). The probe was labeled with [α-32P]dATP by using a random-primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Hybridization was performed at 42°C, and washing was performed at 65°C.

pFB3401, carrying the genes encoding both toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase and at least some of the enzymes involved in the lower pathway (6), and its derivative pBZ2035, containing touA and touB in a 3.5-kb EcoRI fragment (6, 7), were used as probes for tou (toluene o-xylene utilization) genes.

Three plasmids were used as the source of xyl (m-xylene and p-xylene degradation) genes. pED3306 (28) contained the entire pWW0 upper pathway operon. xylAM genes, coding for the two subunits of xylene monooxygenase, were isolated as a 2.5-kb SalI-HindIII fragment from pGSH2836 (19). xylB, coding for benzylalcohol dehydrogenase, and xylN, of unknown function, were isolated as a 2.7-kb SalI-ClaI fragment from pGSH2833 (19). xylC, coding for benzaldehyde dehydrogenase, was isolated as a 1.3-kb PstI-XbaI fragment from pED3306.

Cloning strategy.

To clone regions of interest from chromosomal DNA, mini-libraries were constructed as follows. After DNA digestion with the suitable enzyme(s), restriction fragments were separated by standard agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragments of the desired length (±200 bp) were identified by using suitable DNA markers, slices were cut from the agarose gel, and the DNA was purified. To verify that the desired fragment was included, 300 ng of each fraction was transferred to a nylon membrane, and a Southern analysis was performed with the appropriate probe. Approximately 1.5 μg of DNA from the appropriate fraction was then used for the ligation with the dephosphorylated cloning vector. The mini-libraries obtained were screened by colony hybridization (32).

Enzyme assays.

Xylene monooxygenase activity, responsible for the hydroxylation of a methyl group, was assayed in E. coli DH5α cells. Cultures (100 ml) were grown in M9-salts medium (21) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 before IPTG induction. The cultures were further incubated to reach an OD600 of approximately 0.7. The cells were harvested, washed in phosphate buffer (pH 7), and resuspended in the same buffer to obtain an OD600 of 2. Next, 20 mM glucose and 3 μl of p-xylene/ml were added, and the suspensions, in tightly closed containers, were incubated at 37°C. At 30-min intervals, samples were collected. The cells in these samples were eliminated by filtration, and the supernatants were analyzed by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography using a NovaPack C18 cartridge column eluted with acetonitrile-water at a concentration of 50:50 (flow rate, 1 ml/min). The detector was set to 254 nm, and the amount of 4-methylbenzyl alcohol produced was determined by using a calibration curve.

Benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase activity was assayed in crude cell extracts obtained by passage through an Aminco French pressure cell by measuring the rate of NAD+ reduction (40) supplying 4-methylbenzyl alcohol as the reaction substrate.

Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Sigma Chemical Co.) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

DNA amplification, nucleotide sequencing, and sequence analysis.

The DNA sequence of the P. stutzeri R1 xylWC and touA regions were determined directly from the PCR amplification products. Amplification of the xylWC region was performed with the primers 5′-GGGGGCGGATGAATGCAT-3′ and 5′-CCGGCCTCCCATAAGCCC-3′. The touA region was amplified with the primers 5′-GTGGGAAGGGCTACGTCTGA-3′ and 5′-CCAATCCCATTTCCTGCTCC-3′. Plasmid templates for DNA sequencing were isolated with purification kits purchased from Macherey-Nagel-Düren or Qiagen. Nucleotide sequences were determined directly from pFC1965, pFC4037, or their derivatives with the Deaza G/AT7Sequencing Mixes kit, used according to the supplier’s instructions (Pharmacia Biotech), and with [α-35S]dATP and T7, SP6, or specific synthetic primers. The sequence was analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.). software package (10). The National Center for Biotechnology Information BLASTP program (1) was used to search a nonredundant peptide sequence database.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of ISPs1 has been submitted to the EMBL data bank under accession no. AJ012352.

RESULTS

Southern analyses of P. stutzeri OX1, M1, and R1 genomes.

Any differences among OX1, M1, and R1 genomes with regard to o-xylene or m-xylene and p-xylene catabolic genes were investigated by Southern analyses. The genes involved in the initial steps of o-xylene catabolism (tou) were isolated from a P. stutzeri OX1 genomic library in the pFB3401 cosmid (6). As a probe for the genes involved in m-xylene and p-xylene catabolism, a fragment containing the pWW0 upper pathway genes (xyl) cloned in pED3306 from P. putida PaW1 (28), with which the P. stutzeri OX1 genome was previously demonstrated to have homology (4), was used.

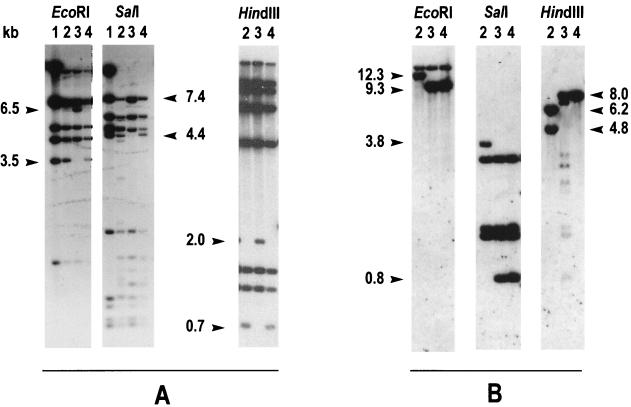

When probed with the tou genes, OX1 and R1 DNAs showed identical hybridization profiles, while in the M1 genome, novel fragments were detectable (Fig. 2A), likely resulting from the insertion of a 3-kb sequence of unknown origin. When the HindIII patterns were analyzed, it was observed that the M1 hybridization profile differed from those of OX1 and R1 by the presence of a 2-kb fragment and by the absence of a 0.7-kb fragment. If we consider an insertion event, this result could be explained by supposing that the inserted sequence had at least one HindIII cleavage site and that only one end was recognized by the tou gene probe. Based on the genetic and physical map of pFB3401 and its derivatives (6, 7), the insertion was shown to occur inside the touA gene (Fig. 3A and C), which is the first of the six genes of the toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase gene cluster and which codes for the large subunit of the terminal hydroxylase (7). The inability of M1 to grow on o-xylene could thus be the result of an insertional inactivation of a gene essential for o-xylene catabolism. Consistently, no transformation of any xylene isomer into the corresponding dimethylphenol was detectable in strain M1 (4).

FIG. 2.

Southern hybridizations of the P. stutzeri OX1 (lane 2), M1 (lane 3), and R1 (lane 4) genomic DNAs digested with the indicated restriction enzymes and probed with the tou genes (pFB3401) (A) and the pWW0 xyl upper pathway genes (pED3306) (B). Lane 1, pFB3401.

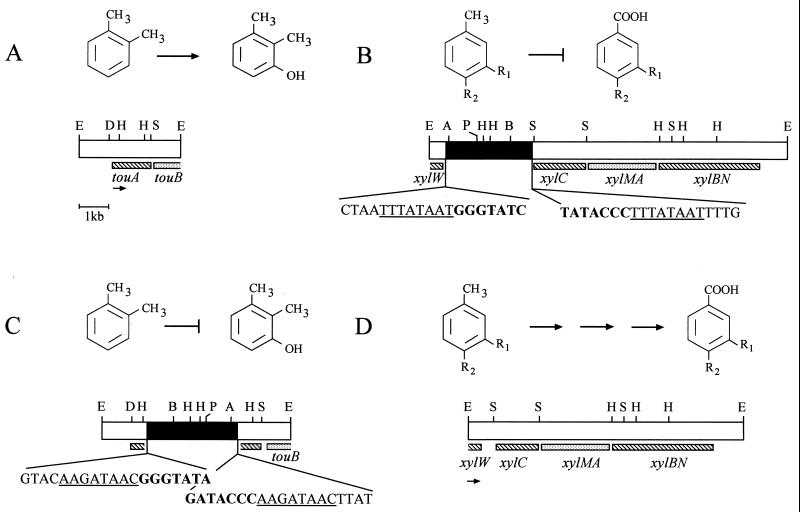

FIG. 3.

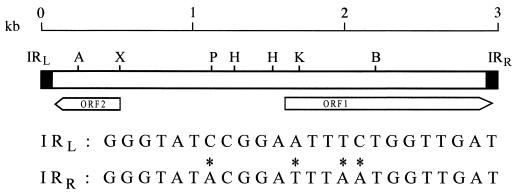

Schematic representation of tou and xyl gene arrangement in P. stutzeri OX1 (A and B) and M1 (C and D) and of the reactions they are involved in. The bars represent the physical maps of the inserts of pBZ2035 (A), pFC1965 (C), and pFC3095 (D). In pFC3095 and in P. stutzeri OX1 (B), xyl genes were mapped by Southern hybridization. The 3.7-kb EcoRI-SalI DNA fragment from the P. stutzeri OX1 xyl region illustrated in panel B was cloned in pFC4037. Only relevant restriction sites are shown. In panels B and C, the black boxes indicate ISPs1; IRL is close to the AvaI site. In the sequences shown below, the 8-bp direct duplications of the target DNA are underlined (only the coding strands are shown) and 7 bp of the 24-bp ISPs1 inverted repeats are shown in boldface (complementary strand) in panel C. Abbreviations: A, AvaI; B, BstEII; D, DraI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; P, PvuII; S, SalI.

In Southern analyses performed with pWW0 xyl upper pathway genes, M1 and R1 genomes showed identical hybridization patterns when digested with EcoRI and SalI (Fig. 2B). In the HindIII digestion, both M1 and R1 showed a reproducible 8-kb fragment homologous to the probe, whereas the extra bands of smaller size in the M1 DNA digestion were not observed in other experiments. The M1 and R1 genomes should thus be regarded as affected by a 3-kb deletion with respect to that of OX1. Because strain OX1 is unable to degrade m-xylene and p-xylene, it was reasonable to propose a correlation between this metabolic incapacity and the presence of the 3-kb sequence in the region homologous to the pWW0 upper pathway genes, a situation similar to that previously observed for M1 o-xylene catabolic genes.

Cloning of the upper pathway genes for m-xylene and p-xylene catabolism from P. stutzeri M1.

The region homologous to pWW0 xyl genes was cloned from the M1 genome to demonstrate that it actually coded for activities involved in m-xylene and p-xylene catabolism. A map of this region was also needed to precisely locate the additional 3-kb sequence detected in the corresponding OX1 region. A mini-library of approximately 9- to 10-kb EcoRI fragments was obtained from M1 and screened by using the pWW0 xylAM genes as probes, and plasmid pFC3095 was selected (see Materials and Methods for the cloning strategy). Southern hybridization of pFC3095 with pWW0 xylAM, xylBN, and xylC genes (results not shown) made it possible to draw the map depicted in Fig. 3D and revealed a highly conserved gene order with respect to the pWW0 upper operon gene organization (19). By analogy with the pWW0 upper pathway genes, it can be supposed that the cloned genes are transcribed from left to right with respect to the map shown in Fig. 3D. The sequence (not shown) of approximately 800 bp at the left end of the map reported in Fig. 3D revealed 96% overall identity with the pWW0 upper pathway genes. In particular, sequences homologous to the 3′ end of the xylW gene of unknown function (38) and to the 5′ end of xylC coding for benzaldehyde dehydrogenase (19) were easily recognizable.

Xylene monooxygenase activity (0.33 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1 in uninduced E. coli cells; 1.14 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1 upon IPTG induction) and benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase activity (716 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1) were expressed from M1 cloned genes. The cloned xylene monooxygenase activity was unable to transform o-xylene into 2-methylbenzyl alcohol, confirming the data obtained with M1 cells (4).

Referring to the map of the xyl region (Fig. 3D) and comparing OX1 and M1 hybridization profiles (Fig. 2B), it was possible to map the OX1 3-kb insertion between the regions homologous to xylW and xylC (Fig. 3B). Previously, data showed that in P. stutzeri OX1, m-xylene and p-xylene were not transformed into the corresponding methylbenzyl alcohols, whereas such transformation occurred in the mutant R1 (4, 11). Considering that most transposons exert strong polar effects on the expression of genes which lie distal to the site of the inserted element (23), the inability of OX1 to grow on m-xylene and p-xylene might be ascribed to a polar effect on xyl gene expression rather than to the disruption of the xylene monooxygenase-encoding gene.

Cloning and comparison of the P. stutzeri OX1 and M1 IS.

Though hybridization experiments could give only preliminary data about the two unidentified sequences detected in M1 and OX1 genomes, it was observed that both elements showed similar lengths and restriction patterns. In fact, in Southern hybridizations, in both the M1 and OX1 insertion elements no restriction sites were detectable for EcoRI and SalI (Fig. 2A and B) or for BglII, XhoI, and DraI (Southern hybridizations not shown), while both contained at least one HindIII cleavage site (Fig. 2A and B). Based on these data, it was possible to speculate that a similarity between the genetic elements found in the OX1 and M1 genomes existed. To verify this hypothesis, the two elements were cloned from the M1 and OX1 genomes.

The M1 insertion element was entirely contained in a 6.5-kb EcoRI fragment (Fig. 2A). A mini-library was prepared by using a fraction of M1 EcoRI-digested DNA enriched in fragments of the desired size (see Materials and Methods) and screened by colony hybridization with the touAB probe (pBZ2035; Fig. 3A). Plasmid pFC1965 was selected, and a restriction map of the insert was obtained (Fig. 3C). This analysis confirmed that the M1 insertion element lacked SalI, BglII, DraI, and XhoI restriction sites, but two HindIII cleavage sites were mapped.

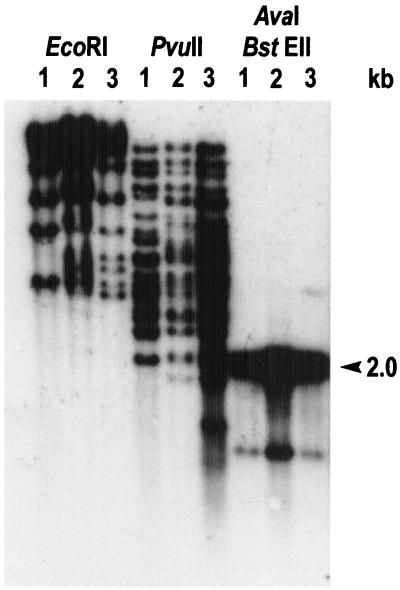

Preliminary attempts to verify homology between M1 and OX1 insertion elements were performed by using pFC1965 as the probe for OX1, M1, and R1 genomes. Several hybridization signals were detected (not shown), suggesting that multiple copies of the cloned insertion element were present in each probed strain. This hypothesis was confirmed by using a 2-kb AvaI-BstEII internal fragment as the probe (Fig. 4). As there were no EcoRI sites and only one PvuII restriction site in the IS (see Fig. 5 for the restriction map), it was possible to deduce that approximately 10 individual copies of the IS are present in the genome of each of the three strains. Based on the hybridization profiles, it is also possible that transposition events other that those investigated in the present work occurred in the genomes of the M1 and R1 mutants.

FIG. 4.

Southern hybridization with the AvaI-BstEII 2-kb internal probe derived from ISPs1 of the P. stutzeri OX1 (lane 1), M1 (lane 2), and R1 (lane 3) genomic DNAs digested with the indicated restriction enzymes.

FIG. 5.

Schematic representation and restriction map of ISPs1. The black boxes represent the IRs (not shown to scale). Nucleotide sequences of IRL and IRR are shown at bottom. Mismatches are marked with an asterisk. The arrows indicate the directions of transcription of ORF1 and ORF2. Abbreviations: A, AvaI; B, BstEII; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; P, PvuII; X, XbaI.

The IS detected in the OX1 xyl region was cloned as a 3.7-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment by following the same strategy as described above and by using xylW as a probe (0.7-kb EcoRI-SalI fragment isolated from pFC3095). Plasmid pFC4037 was selected, and its insert showed a restriction map identical to (Fig. 3B and C) and cross-hybridized with (not shown) the insertion element cloned from M1.

Sequence analysis of the ISs cloned from P. stutzeri M1 and OX1.

A schematic representation of the insertion element cloned from the M1 strain is depicted in Fig. 5. Its nucleotide sequence was determined from a set of subclones obtained from pFC1965. The IS, designated ISPs1, was delimited by 24-bp inverted repeats (IR), which showed a 4-bp mismatch. External to the IS, the direct duplication of an 8-bp AT-rich region belonging to touA (7) was found (Fig. 3C). Based on these features, and despite its atypical length, ISPs1 seems to belong to the ISL3 family, a sparsely distributed class of insertion elements (26).

Translation of the sequence in all the reading frames possible revealed a long open reading frame (ORF) (ORF1; nucleotides 1649 to 2926) preceded by a putative ribosomal binding site, putatively coding for a 425-amino-acid polypeptide, whose sequence showed significant similarities to several transposases from different ISs related or belonging to the ISL3 family. In particular, the putative ORF1 product was 93% similar to TnpA of the Serratia marcescens IS1396 (25), and, to a lesser extent, to other transposases from ISs of the ISL3 family, such as those from ISPp2 of P. putida ML2 (59%) (GenBank accession no. U25434 [17]), ISAsp1 of Anabaena sp. PCC7120 (45%) (GenBank accession no. U13767 [5]), and IS1001 of Bordetella parapertussis (40%) (36). No homologies with known sequences were found in other parts of the sequence, though another possible ORF was found (ORF2; nucleotides 94 to 492, reverse). Throughout its entire length, the 132-amino-acid putative ORF2 product showed a certain degree of similarity to bacterial transcriptional regulators, such as NolR of Rhizobium leguminosarum (54%) (GenBank accession no. AJ001934 [22]) and Rhizobium meliloti (47%) (24) and HlyU of Vibrio cholerae (44%) (39). Alignment of ORF2 with NolR and HlyU, also revealed a region, spanning amino acids 34 to 54, that strongly resembled the helix-turn-helix motif identified in NolR, HlyU, and in other transcriptional regulators (39).

As regards the IS cloned from OX1 in pFC4037, only 150 bases at each end were sequenced, and complete identity with the corresponding regions of pFC1965 was found. Externally, the presence of sequences homologous to the pWW0 xylW and xylC genes was confirmed. As in pFC1965, 8-bp direct repeats were found, corresponding to the duplication of an AT-rich intergenic region between xylW and xylC (Fig. 3B).

Sequence analysis of the tou and xyl regions of P. stutzeri R1.

Several transposons are known to be capable of excising precisely and thereby regenerating the target DNA to its original sequence and function (23).

To investigate how the excision of ISPs1 resulted in restored catabolic functions, the touA and xylWC DNA regions of the R1 genome were amplified, sequenced, and compared with those of OX1 and M1 strains.

The nucleotide sequence of the touA region (not shown) amplified from the R1 genome was found to be identical to that of the wild-type strain OX1. Restored catabolic functions were thus due to the precise excision of ISPs1 from the M1 genome. As also suggested for the deletion of catabolic genes residing on transposons (14, 29, 30), such an event may occur by means of homologous recombination involving the direct repeats.

The nucleotide sequence of the xylWC region (not shown) amplified from R1 DNA was found to be identical to that cloned from the M1 genome in pFC3095. Compared with the pWW0 corresponding region, taken as the archetype of xyl genes, the M1 and R1 xylWC regions displayed five additional nucleotides, which could be regarded as remaining from an imperfect excision of ISPs1 from the OX1 genome. However, since these five additional nucleotides are located in a nontranslated intergenic region between the end of xylW and the beginning of xylC, it is reasonable to suppose that their presence does not affect the expression of functional enzymes, as also demonstrated by enzymatic activities detected in E. coli cells carrying pFC3095.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial degradation of methylbenzenes has been extensively investigated. A model for the degradation of m-xylene and p-xylene is represented by the TOL pathway encoded by the xyl genes (9). Less information, especially at the genetic level, is available with regard to o-xylene degradation; however, the direct oxygenation of the aromatic ring seems to be required for the catabolism of this compound (6, 15, 33). Toluene can be degraded via both pathways.

Although TOL strains are widespread in the environment, laboratory competition experiments showed that, under some conditions, the strains which degrade toluene through the TOL pathway are disadvantaged with respect to those which attack this molecule through the direct oxygenation of the aromatic nucleus, regardless of whether it is a mono- or a dioxygenation (13). It is thus possible that, under particular conditions, bacterial strains endowed with the ring oxidation pathway for methylbenzene degradation are competitive, as is also suggested by the number of isolates displaying this metabolic feature (16, 20, 31, 34, 44). Furthermore, depending on the substrate range of the oxygenases involved, the direct oxygenation of the aromatic ring may allow bacteria to use o-xylene (6, 15, 33).

At the phenotypic level, P. stutzeri OX1 shows no analogy with typical TOL strains, but it carries all the genetic information required for the catabolism of m-xylene and p-xylene. In fact, the spontaneous mutant P. stutzeri M1 displays a phenotype undistinguishable from that of several environmental isolates selected for growth on m-xylene and p-xylene and here we demonstrate that even at the genetic level P. stutzeri M1 can be considered a TOL strain, carrying genes coding for activities involved in m-xylene and p-xylene catabolism, highly homologous to and arranged as for the archetypal pWW0 xyl upper pathway genes. Even if the xyl genes are not expressed in the wild-type strain P. stutzeri OX1, their maintenance may confer a selective advantage to the bacterial population. From this perspective, xyl genes represent a reservoir of genetic information and, following changes in environmental conditions, may ensure the survival of the population members in which they are expressed.

In contaminated environments, methylbenzenes are usually present as a mixture. The ability to degrade all the three isomers of xylene may thus represent a selective advantage for bacteria colonizing polluted environments. Although bacterial strains endowed with multiple pathways for toluene degradation are not unknown (20), to the best of our knowledge, only one report of bacterial strains able to grow on the three isomers of xylene has appeared (11). The studies of methylbenzene degradation carried out before now suggest that the three xylene isomers cannot usually be degraded through a unique pathway. This is likely due to the biochemical features of the catabolic enzymes involved. These either have limitations in their range of substrates or lead to the formation of dead-end intermediates (4, 11, 15, 41). Further, bacterial strains such as P. stutzeri R1 (11) that are endowed with both the TOL pathway for m-xylene and p-xylene degradation and the aromatic ring oxidation pathway for o-xylene catabolism do not seem to be widespread. This does not appear to be due to difficulties in recruiting genetic information: several catabolic genes, and among them the xyl genes themselves, are known to reside on transposons which contribute to their diffusion (42). Rather, interference between the two pathways may be responsible for the scarce diffusion of strains endowed with both catabolic routes. In fact, although P. stutzeri R1 is able to grow on m-xylene and p-xylene, it also transforms small amounts of these two isomers into the corresponding dimethylphenols (Fig. 1), which are not used for growth and are toxic to the cells (11). Toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase, which seems to be inducible by each xylene isomer (11), is responsible for this cometabolism (6). Such a strain would be obviously disadvantaged in an environment in which a mixture of the three xylene isomers is present.

At the population level, such interference can be bypassed by switching one of the two catabolic pathways on or off. In P. stutzeri OX1 and its derivatives, the metabolic versatility is brought about by genome rearrangements mediated by a transposable element. ISPs1 can transpose into and precisely excise out of catabolic genes, causing the inactivation or the activation of the corresponding catabolic functions. Consistent with its phenotype, no IS was detected in either the tou or xyl gene cluster in P. stutzeri R1. Although rough, this mechanism contributes to genome plasticity and may provide P. stutzeri with enough variability to allow some members of the population to cope with challenging environmental conditions.

The genomic shock theory proposes that environmental stress stimulates transposon-mediated genomic rearrangements (27). In this way, greater genetic variability would be created in a short time and would subsequently undergo environmental selection. The hypothesis that transposition events are triggered by environmental stress is tantalizing, and further experiments are underway to verify if, in P. stutzeri, transposition frequency is increased under stressful conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica and by the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (Rome), grant CT97.03999.CT04.115.30637.

We are grateful to M. Accarino and to R. Macchi for collaboration on the experimental work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreoni, V. Personal communication.

- 3.Baggi G, Barbieri P, Galli E, Tollari S. Isolation of a Pseudomonas stutzeri strain that degrades o-xylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2129–2131. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2129-2132.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbieri P, Palladino L, Di Gennaro P, Galli E. Alternative pathways for o-xylene or m-xylene and p-xylene degradation in a Pseudomonas stutzeri strain. Biodegradation. 1993;4:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, C. C., K. S. Ramaswamy, S. Endley, J. W. Golden, and R. Haselkorn. Unpublished results.

- 6.Bertoni G, Bolognese F, Galli E, Barbieri P. Cloning of the genes for and characterization of the early stages of toluene and o-xylene catabolism in Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3704–3711. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3704-3711.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertoni G, Martino M, Galli E, Barbieri P. Analysis of the gene cluster encoding toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3626–3632. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3626-3632.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bickerdike S R, Holt R A, Stephens G M. Evidence for metabolism of o-xylene by simultaneous ring and methyl group oxidation in a new soil isolate. Microbiology. 1997;143:2312–2329. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burlage R S, Hooper S W, Sayler G S. The TOL (pWW0) catabolic plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1323–1328. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1323-1328.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux J, Haeberly P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Lecce C, Accarino M, Bolognese F, Galli E, Barbieri P. Isolation and metabolic characterization of a Pseudomonas stutzeri mutant able to grow on the three isomers of xylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3279–3281. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3279-3281.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6125–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duetz W A, De Jong C, Williams P A, Van Andel J G. Competition in chemostat culture between Pseudomonas strains that use different pathways for the degradation of toluene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2858–2863. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2858-2863.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton R W, Timmis K N. Spontaneous deletion of a 20-kilobase DNA segment carrying genes specifying isopropylbenzene metabolism in Pseudomonas putida RE204. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:428–430. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.428-430.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson D T, Subramanian V. Microbial degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Gibson D T, editor. Microbial degradation of organic compounds. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1984. pp. 181–252. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson D T, Zylstra G J, Chauhan S. Biotransformations catalyzed by toluene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida F1. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A M, Iglewski B, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goh, C. B. H., and H. H. M. Tan. Unpublished results.

- 18.Hanahan D. Techniques for transformation of E. coli. In: Glover D M, editor. DNA cloning: the practical approach. Vol. 1. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press Ltd.; 1985. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harayama S, Rekik M, Wubbolts M, Rose K, Leppik R A, Timmis K N. Characterization of five genes in the upper pathway operon of TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida and identification of gene products. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5048–5055. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5048-5055.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson G R, Olsen R H. Multiple pathways for toluene degradation in Burkholderia sp. strain JS150. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4047–4052. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4047-4052.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn M, Kolter R, Thomas C M, Figurski D, Meyer R, Remaut E, Helinski D R. Plasmid cloning vehicles derived from plasmid ColE1, F, RK6 and RK2. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:268–280. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiss, E., A. Kereszt, B. Olah, P. Mergaert, C. Staehelin, J. A. Downie, A. E. Davies, A. Kondorosi, and E. Kondorosi. Unpublished results.

- 23.Kleckner N. Transposable elements in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 1981;15:341–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.15.120181.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondorosi E, Pierre M, Cren M, Haumann U, Buire M, Hoffmann B, Schell J, Kondorosi A. Identification of NolR, a negative transacting factor controlling the nod regulon in Rhizobium meliloti. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:885–896. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90583-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulaeva O I, Koonin E V, Wootton J C, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Unusual insertion element polymorphisms in the promoter and terminator regions of the mucAB-like genes of R471a and R446b. Mutat Res. 1998;397:247–262. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClintock B. The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science. 1984;226:792–801. doi: 10.1126/science.15739260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mermod N, Harayama S, Timmis K N. New route to bacterial production of indigo. Biotechnology. 1986;4:321–324. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meulien P, Downing R G, Broda P. Excision of the 40-kb segment of the TOL plasmid from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 involves direct repeats. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00271202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakatsu C, Ng J, Singh R, Straus N, Wyndham C. Chlorobenzoate catabolic transposon Tn5271 is a composite class I element with flanking class II insertion sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8312–8316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen R H, Kukor J J, Kaphammer B. A novel toluene-3-monooxygenase pathway cloned from Pseudomonas pickettii PKO1. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3749–3756. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3749-3756.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schraa G, Bethe B M, van Neerves A R V, van den Tweel W J J, van der Wende E, Zehnder A J B. Degradation of 1,2-dimethylbenzene by Corynebacterium strain c125. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1987;53:159–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00393844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shields M S, Montgomery S O, Chapman P J, Cuskey S M, Pritchard P H. Novel pathway of toluene catabolism in the trichloroethylene-degrading bacterium G4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1624–1629. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1624-1629.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Meer J R, de Vos W M, Harayama S, Zehnder A J B. Molecular mechanisms of genetic adaptation to xenobiotic compounds. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:677–694. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.677-694.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Zee A, Agterberg C, van Agterweld M, Peeters M, Mooi F R. Characterization of IS1001, an insertion sequence element of Bordetella parapertussis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:141–147. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.141-147.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmid, an M13mp7 derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams P A, Shaw L M, Pitt C W, Vrecl M. XylUW, two genes at the start of the upper pathway operon of TOL plasmid pWW0, appear to play no essential part in determining its catabolic phenotype. Microbiology. 1997;143:101–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams S G, Attridge S R, Manning P A. The transcriptional activator HlyU of Vibrio cholerae: nucleotide sequence and role in virulence gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:751–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worsey M J, Williams P A. Metabolism of toluene and xylenes by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for a new function of the TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:7–13. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.7-13.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wubbolts M G, Reuvekamp P, Witholt B. TOL plasmid specified xylene oxygenase is a wide substrate range monooxygenase capable of oleofin epoxidation. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1994;16:608–615. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wyndham R C, Cashore A E, Nakatsu C H, Peel M C. Catabolic transposons. Biodegradation. 1994;5:323–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00696468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vector and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yen K, Karl M R, Blatt L M, Simon M J, Winter R B, Fausset P R, Lu H S, Harcourt A A, Chen K K. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5315–5327. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5315-5327.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]