Abstract

Background

Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, are being increasingly used to deliver public health interventions. Despite the high level of research interest, there is no consensus or guidance on how to report on social media interventions. Reporting guidelines that incorporate elements from behavior change theories and social media engagement frameworks could foster more robust evaluations that capture outcomes that have an impact on behavior change and engagement.

Objective

The aim of this project is to develop, publish, and promote a list of items for our Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research (RESOME) checklist.

Methods

RESOME will be developed by using a modified Delphi approach wherein 2 rounds of questionnaires will be sent to experts and stakeholders. The questionnaires will ask them to rate their agreement with a series of statements until a level of consensus is reached. This will be followed by a web-based consensus meeting to finalize the reporting guidelines. After the consensus meeting, the reporting guidelines will be published in the form of a paper outlining the need for the new guidelines and how the guidelines were developed, along with the finalized checklist for reporting. Prior to publication, the guidelines will be piloted to check for understanding and simplify the language used, if necessary.

Results

The first draft of RESOME has been developed. Round 1 of the Delphi survey took place between July and December 2021. Round 2 is due to take place in February 2022, and the web-based consensus meeting will be scheduled for the spring of 2022.

Conclusions

Developing RESOME has the potential to contribute to improved reporting, and such guidelines will make it easier to assess the effectiveness of social media interventions. Future work will be needed to evaluate our guidelines’ usefulness and practicality.

International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID)

PRR1-10.2196/31739

Keywords: social media, research design, web-based social networking, health behavior, health promotion, public health

Introduction

Social media use is becoming increasingly common; social media has been estimated to be used by more than half of the world’s population [1,2]. Given social media’s potential for promoting widespread public engagement, it is commonly incorporated into public health interventions [3,4]. The term intervention in this protocol refers to a spectrum of activities that range from national awareness-raising public health campaigns, such as awareness months, to more targeted activities that use social media groups to deliver information or interventions to specific audiences [5,6].

Systematic reviews of public health interventions involving social media have shown that social media has been used for a wide range of health promotion activities, such as weight management improvement, physical activity, smoking cessation, mental health improvement, the promotion of the use of health care services, HIV prevention, cancer prevention, and vaccination uptake [7-18]. These reviews highlight several potential benefits of social media interventions; they are generally found to be acceptable and feasible, and they offer unique advantages over traditional health messaging, such as the functionality of targeting information regarding specific populations, particularly those who may be hesitant to access in-person services [10,14,19,20].

Several methodological challenges however have been identified that hinder the ability to draw strong conclusions about the effectiveness of social media interventions. For example, some studies do not sufficiently describe interventions to allow for replicability, to understand the “active ingredients” of an intervention, or to understand the behavior change techniques used [11,13,15,16]. Very few studies explore the impacts on behavior change or quantitative clinical outcomes, and the majority instead focus on descriptions of engagement within a social media platform, such as views or shares, which may not indicate a genuine increase in knowledge or change in behavior [8,10,11,15,17]. Further, 3 systematic reviews reported that the majority of their included studies had a high or unclear risk of bias, which prevented a meta-analysis from being performed [8,13,21]. Many campaigns are not formally evaluated, and reports on social media campaigns are often not publicly available. These issues further contribute to the challenge of synthesizing research evidence. Furthermore, although social media interventions have been carried out in a variety of different populations, there are very few studies that actively explore and report the impact of social media interventions on health inequalities [7,11,22].

There are existing reporting guidelines that have some relevance to social media interventions, such as Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in Healthcare: Revised Guideline (CReDECI 2) for complex health care interventions, CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomized controlled trials, Guidance for Reporting Intervention Development Studies in Health Research (GUIDED) for intervention development, and guidelines for using the theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions and for better reporting on interventions (eg, Template for Intervention Description and Replication [TIDieR]) [23-27]. However, there are currently no reporting guidelines available that take into account the diverse and unique aspects of research on social media interventions. For example, not all evaluations of social media interventions have the same study design; it is not always feasible or possible to randomize participants in a trial, and some studies are observational in nature (eg, an evaluation of a national awareness campaign delivered by a third party) [19,20,28].

There is therefore a clear need for guidance to be developed on the reporting of social media interventions. The development of reporting guidelines that incorporate elements from existing and widely used behavior change theories and social media engagement frameworks could foster more robust evaluations that capture outcomes that have an impact on behavior change and engagement and inform policy decisions [19,29,30]. Specific guidelines for social media research could include additional domains about the methods for collecting data, provide technical information about social media platforms and the social context in which the research takes place, and address the ethical and privacy issues that are unique to social media research.

The aim of this project is to develop and establish consensus on which items should be included in reporting guidelines for social media interventions. The development of these guidelines will be achieved by conducting a series of Delphi surveys to achieve consensus on which items should be included.

Methods

The methods that will be used in this project have been informed by guidance on the development of reporting guidelines that was produced by Moher et al [31] in 2010 and the EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research) Network [32]. The development of our Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research (RESOME) has been registered on the EQUATOR Network website [33].

Design

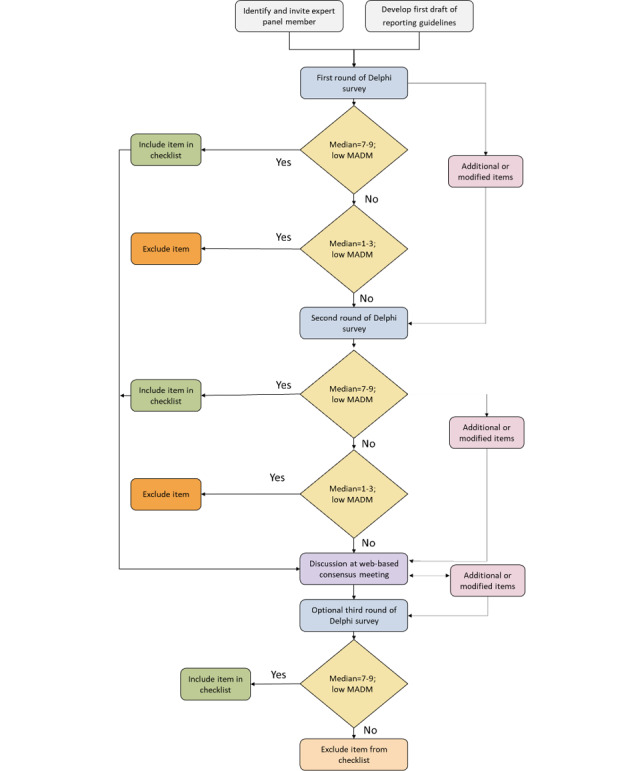

The reporting guidelines will be developed by conducting a Delphi exercise, during which several rounds of questionnaires will be sent to experts and stakeholders. The questionnaires will ask them to rate their agreement with a series of statements until a level of consensus is reached. This will be followed by a web-based consensus meeting to finalize the reporting guidelines [34,35]. Figure 1 summarizes the processes of the Delphi method.

Figure 1.

Delphi process flowchart. MADM: mean absolute deviation from the median.

The project is led by an expert, multidisciplinary executive panel composed of 9 people from the fields of behavioral science, epidemiology, health services research, public health, social media, and statistics and patient and public representatives. The panel is responsible for providing academic oversight for the project and directly participating in some aspects of the research activities, such as identifying participants, chairing discussions, and contributing to developing research reports.

Participants

As recommended by the EQUATOR Network [32] and the guidance produced by Moher et al [31] in 2010, stakeholders with expertise in statistics, epidemiology, and research methodology; primary care and public health professionals; journal editors; and patient and public representatives will be invited to form an expert panel in addition to researchers with experience in conducting or evaluating social media interventions. Potential participants will be identified via research networks and invited to take part by email. We will contact social media researchers and journal editors directly and advertise the project on social media. The invitation email will contain background information on the project; a link to the preprint of the protocol; a participant information sheet; and a privacy notice stating that any personal data will be collected, stored, and deleted in accordance with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (2018) [36]. Potential participants will be asked to share information about the project with colleagues and among their own research networks to increase the pool of potential participants. The final participant panel will include a maximum of 30 people. We will aim to ensure that the panel is diverse with respect to age, gender, ethnicity, and subject specialty.

Delphi Survey

The purpose of the Delphi exercise is to generate a list of items for consideration at the consensus meeting [34]. The first iteration of the checklist items was developed based on previously conducted research and relevant guidelines. The current items are outlined in Table 1 [4,11,23-25]. Using questionnaires will allow for anonymous responses, which can help with avoiding influence from other members, and allow people from geographically dispersed countries to participate. The purpose of the web-based consensus meeting is to provide an opportunity for clarifying and discussing items.

Table 1.

The draft of Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research to be included in round 1 of the Delphi exercise.

| Sections and item numbers | Descriptiona | |

| Title and abstract | ||

|

|

1A | Indicate the use of social media in the title or abstract |

|

|

1B | Indicate the social media platform(s) in the title or abstract |

| Methods: study design | ||

|

|

2A | Specify study design e.g., observational, experimental, qualitative |

|

|

2B | Specify if this study reports an evaluation of an existing social media campaign (e.g., a process evaluation) or a novel intervention |

|

|

2C | Specify the trial registration details and/or previously published protocol, if applicable |

| Methods: participants and data | ||

|

|

3A | Describe the eligibility criteria for participants to be involved in the study or the population targeted by the intervention |

|

|

3B | Describe any methods used to identify participants |

|

|

3C | Describe how participants were recruited into the study |

|

|

3D | Explain if the data are publicly available and where it can be accessed |

|

|

3E | Describe the methods used to collect data e.g., search terms, social media metrics or data mining |

| Methods: setting | ||

|

|

4A | Provide a summary of the social media platform(s), including the main features and how it is used |

|

|

4B | Provide information about the number of users of the social media platform(s) and their characteristics |

|

|

4C | Describe any relevant algorithms employed by the social media platform(s) at the time of the research which may have an impact on the way that information is shared and viewed |

|

|

4D | Provide details of any social, political and economic contextual factors relevant to the project e.g., ongoing public debates or events |

|

|

4E | Provide dates of exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

| Methods: intervention | ||

|

|

5A | Describe the primary and secondary aims of the intervention or campaign (e.g., change in knowledge, awareness, intentions, behaviours, or health outcomes) |

|

|

5B | Describe how the social media intervention or campaign works with reference to behaviour change techniques, mechanisms of action, and targeted behaviour change |

|

|

5C | State whether the intervention or campaign was paid for or not |

|

|

5D | Describe the purchase model if used for any advertisements or promoted posts |

|

|

5E | Describe the implementation strategy for the social media campaign and any incentives for participants |

|

|

5F | Describe the resources required for the campaign or intervention e.g., time, money, technology, equipment, and partners |

|

|

5G | Provide a description of the intervention with sufficient detail to allow replication, including any links to audio/visual materials |

|

|

5H | Specify whether the intervention materials are subject to a copyright license or can be reused e.g., through a public or creative common license |

|

|

5I | Describe the creative process underlying the development of intervention materials, including an acknowledgement of any outside agencies involved in developing creative materials |

|

|

5J | Describe any aspects of the intervention which took place outside of social media e.g., television, print and radio communications |

|

|

5K | Describe any secondary features of the intervention or campaign which may impact the outcome measures e.g., sponsors, collaborators and links to other websites |

| Methods: measures | ||

|

|

6A | Reach: Describe the demographic data of included participants, if applicable |

|

|

6B | Low-medium level engagement: Describe which measures were used to measure engagement with the intervention e.g., likes, comments, reposts |

|

|

6C | High-level engagement: Describe any measures for change in knowledge, awareness of offline activities e.g., measures of behaviour change, intentions, or health-related outcomes. |

| Methods: ethics | ||

|

|

7A | Provide details of any ethical implications related to consent, privacy issues and data protection |

|

|

7B | Provide details of any safeguarding measures e.g., moderation of discussion |

|

|

7C | Describe any commercial interests related to the project e.g., funding, sponsorship, advertisements, endorsements |

|

|

7D | Describe how any commercial interests were communicated to participants |

| Results: participant flow diagram | ||

|

|

8 | Include a flow-diagram showing the number of people who were targeted, exposed to the intervention, engaged with the intervention, and included in the analysis, if applicable |

| Results: participant characteristics | ||

|

|

9 | Include a table showing demographic information for participation (by group if a control group is used), if applicable |

| Results: outcomes | ||

|

|

10A | Report descriptive statistics of social media metrics, such as reach, views, likes and reposts |

|

|

10B | Include a description of novel content such a conversations, videos, or images |

|

|

10C | For measures of high-level engagement, provide an estimation of differences between groups or over time with a measure of precision (such as 95% confidence interval). |

| Discussion: summary of results | ||

|

|

11 | Describe the main results in the context of the objectives described in the methods section and any previously published research protocols or trial registrations |

| Discussion: feasibility | ||

|

|

12 | Discuss the feasibility of the campaign and intervention for wider implementation with reference to the benefits in relation to the resources required |

| Discussion: generalizability | ||

|

|

13 | Discuss which components are generalisable to other social media platforms and contexts e.g., for different target behaviours, socio-demographic groups or countries |

aAll descriptions appear exactly as they did when they were presented to participants.

Participants will be asked to rate their agreement with including each item on a scale of 1 to 9 (1=strongly disagree; 9=strongly agree). Each question will be accompanied by a free-text box, in which participants will be able to add comments, such as justifications for their responses, suggestions for alternative phrasing, or additional items.

After the first round, items for which there is consensus for inclusion will be retained (see Statistical Analysis section for further details). Each participant will receive the aggregate results of the survey, along with their own answers to the questions. Any items for which consensus is not reached will be included in a second round of surveys, along with any additional items or modifications identified through free-text responses. Participants will then be presented with the results of the first round and asked to rate the items again before the web-based consensus meeting.

Consensus Meeting

In-person meetings are one of the major challenges of consensus meetings due to the cost and practicality of convening an international group of experts. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, these meetings will be conducted on the internet, which will eliminate the cost of international travel and allow for the greater participation of experts in different countries.

The consensus meeting will be limited to 30 people to allow for effective communication and participation and will take place over 1 day. Prior to the meeting, preparations will be made, including developing the agenda and presentations relevant to the session; making sure that participants have information about joining the session; sharing the results of the Delphi exercise; and sharing any other relevant materials, such as the current item list. The meeting will be conducted by using web-based conferencing software, such as Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc) or Remo (Remo.co), and conversations will be recorded for future reference.

The consensus meeting will include presentations on the research background and the results of the Delphi exercise. Each item will be discussed in turn to allow participants to express their viewpoints in more detail and to ultimately reach consensus on items’ inclusion or exclusion in the reporting guidelines. Due to the meeting taking place on the internet, it will be possible to incorporate live and anonymous voting on items to break deadlocks. The meeting will also be used to discuss additional reporting guidelines, such as the inclusion of a participant flowchart or a summary of social media metrics; the name of the reporting guidelines; the publication and dissemination strategy; and the accompanying explanation and elaboration document.

Statistical Analysis

For each item, the mean, SD, median, IQR, and mean absolute deviation from the median (MADM) will be used to assess the strength and extent of agreement [37]. Medians of 7 to 9 will be defined as strong support, medians of 4 to 6 will be defined as moderate support, and medians of 1 to 3 will be defined as no support. The MADM will be categorized as high (>2.68), medium (1.34-2.67), or low (<1.33), with a low MADM representing a high-level consensus. Items will be included if the median score is ≥7 and the MADM is low (<1.33). Items will be excluded if the median score is ≤3 and the MADM is low (<1.33). Items that do not meet these criteria after the second round will be discussed in the web-based consensus meeting, and an additional, third Delphi round will be conducted after the meeting. If consensus is not reached by this stage, a decision will made by the executive panel.

Free-text comments from each Delphi survey will be qualitatively analyzed by using a thematic analysis [38]. The main themes will be reported to the executive panel and the participants in order to identify any additional items or item modifications that need to be included in the next round of the survey.

Developing the Reporting Guidelines and an Explanatory Document

After the consensus meeting, the reporting guidelines will be published in the form of a paper outlining the need for the new guidelines and how the guidelines were developed, along with the finalized checklist for reporting. Prior to publication, guidelines will be piloted to check for understanding and to simplify the language, if necessary.

An explanation and elaboration document will be published alongside the reporting guidelines. The document will explain why each reporting guideline is important and provide examples for each item.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained in June 2021 from the University College London ethics committee (ID number: 14687/004) to contact participants and to collect and store their responses in accordance with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (2018). All participants will complete a web-based consent form prior to taking part in the study and have the right to withdraw themselves from the study.

Dissemination

After the publication of the reporting guidelines, a range of strategies will be implemented to improve the usability and implementation of the reporting guidelines (Textbox 1).

Strategies for improving the usability and implementation of Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research.

Strategies

Ensuring that the guidelines are freely available and are in an editable format

Creating a dedicated website containing additional resources

Recording the guidelines on the EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research) Network database

Obtaining journal endorsement and endorsement from other organizations

Presenting the guidelines at relevant conferences and meetings

Writing blog posts and other social media posts about the guidelines

Developing and delivering web-based training in using the guidelines

Translating the guidelines into different languages

Results

As of January 2021, the executive panel has been convened and has drafted the first version of the RESOME checklist. The recruitment of participants and round 1 of the Delphi survey took place between July and December 2021. Round 2 is due to take place in February 2022, and the web-based consensus meeting will be scheduled for the spring of 2022. The finalized guidance and supporting explanatory document will be published by August 2022.

Discussion

Study Implications

Social media interventions are a relatively recent phenomenon that has attracted a high level of research interest; however, there is a clear need for reporting, as evidenced by the large number of reviews that report a lack of robust and rigorously conducted studies [8,10,11,13,15-17,21]. The rapid changes in the way that people use social media make investigating methods for promoting the public’s engagement with health messages via social media a high priority. The development of and adherence to reporting guidelines for social media interventions will facilitate replicability and allow for a better understanding of which interventions are effective and for whom they are effective.

Delphi surveys are a validated consensus method that involve using anonymous surveys to quantify levels of consensus according to an a priori statistical analysis plan. This approach is especially beneficial because it allows for the equal contribution of participants and prevents dominating personalities from impacting decision-making [39]. Qualitative and quantitative data will be analyzed to achieve a deeper understanding of participants’ responses. The main limitation of Delphi surveys is the lack of opportunities for nuanced discussions or clarifications among individuals. This limitation will be addressed with an interactive and deliberative consensus meeting. Due to the web-based nature of the consensus building process, a broader range of stakeholders than what would normally be possible will be recruited. By including participants from different geographical regions who would not normally be able to participate, it is possible to achieve a global perspective and an increased level of diversity in terms of participants [40]. The publication of this protocol provides an opportunity to improve the research methods (via feedback from reviewers) and transparency for the process of including and excluding items.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this project that must be acknowledged. First, the recruitment of the expert panel may be challenging in terms of finding and engaging people with relevant expertise and diverse opinions. Second, the reporting guidelines that will be produced in this project may not be applicable or relevant to all types of social media interventions. It is expected that these social media reporting guidelines could and should be used by researchers in conjunction with other existing reporting guidelines (eg, CReDECI 2, CONSORT, GUIDED, and TIDieR) [23-27]. Third, the field of social media research is fast-moving, and as such, any reporting guidelines will require regular reviews and updates to reflect changes in methodological approaches. Finally, once the reporting guidelines have been published, several steps will be taken to disseminate and encourage their use. However, this will require engagement and endorsement by relevant journals and third-party organizations.

Conclusions

There is a lack of high-quality research on social media interventions, which limits our understanding of their effectiveness. This protocol outlines the methods that will be used to develop reporting guidelines for social media interventions. The development of these guidelines are a first step toward improving the quality, rigor, and robustness of social media interventions. Future work will be needed to evaluate the guidelines’ usefulness and practicality.

Acknowledgments

This report presents independent research commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme, conducted through the Policy Research Unit in Cancer Awareness, Screening and Early Diagnosis, PR-PRU-1217-21601. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or its arm's-length bodies, or other government departments.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CReDECI 2

Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in Healthcare: Revised Guideline

- EQUATOR

Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research

- GUIDED

Guidance for Reporting Intervention Development Studies in Health Research

- MADM

mean absolute deviation from the median

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- RESOME

Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research

- TIDieR

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: AK and CVW conceptualized the project. All authors contributed to refining the study methodology and contributed meaningfully to the drafting and writing of the final protocol.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Internet access – households and individuals, Great Britain: 2018. Office for National Statistics. 2018. [2022-04-07]. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2018 .

- 2.Kemp S. Digital 2020: Global digital overview. DataReportal. 2020. Jan 30, [2022-04-07]. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview .

- 3.Korda H, Itani Z. Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract. 2013 Jan;14(1):15–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839911405850.1524839911405850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neiger BL, Thackeray R, Burton SH, Thackeray CR, Reese JH. Use of twitter among local health departments: an analysis of information sharing, engagement, and action. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Aug 19;15(8):e177. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2775. https://www.jmir.org/2013/8/e177/ v15i8e177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Be clear on cancer. Cancer Research UK. [2022-04-07]. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/awareness-and-prevention/be-clear-on-cancer/about-be-clear-on-cancer .

- 6.Breast Cancer Awareness Month. National Breast Cancer Foundation. [2022-04-07]. https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-cancer-awareness-month .

- 7.Welch V, Petkovic J, Pardo JP, Rader T, Tugwell P. Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: an overview of reviews. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016 Apr;36(4):63–75. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.4.01. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.4.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Tang W, Pan S, Pendse R, Tucker JD. Social media interventions to promote HIV testing, linkage, adherence, and retention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Nov 24;19(11):e394. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7997. https://www.jmir.org/2017/11/e394/ v19i11e394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tso LS, Tang W, Li H, Yan HY, Tucker JD. Social media interventions to prevent HIV: A review of interventions and methodological considerations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016 Jun 01;9:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.019. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26516632 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han CJ, Lee YJ, Demiris G. Interventions using social media for cancer prevention and management: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(6):E19–E31. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000534. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28753192 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plackett R, Kaushal A, Kassianos AP, Cross A, Lewins D, Sheringham J, Waller J, von Wagner C. Use of social media to promote cancer screening and early diagnosis: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 09;22(11):e21582. doi: 10.2196/21582. https://www.jmir.org/2020/11/e21582/ v22i11e21582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Wood CE, Kostkova P. Vaccine hesitancy and behavior change theory-based social media interventions: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med. 2022 Feb 16;12(2):243–272. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab148. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34850217 .6445967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu MSH, Rouf A, Allman-Farinelli M. Effectiveness and behavioral mechanisms of social media interventions for positive nutrition behaviors in adolescents: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2018 Nov;63(5):531–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.009.S1054-139X(18)30249-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naslund JA, Kim SJ, Aschbrenner KA, McCulloch LJ, Brunette MF, Dallery J, Bartels SJ, Marsch LA. Systematic review of social media interventions for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2017 Oct;73:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.002. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28499259 .S0306-4603(17)30172-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw JM, Mitchell CA, Welch AJ, Williamson MJ. Social media used as a health intervention in adolescent health: A systematic review of the literature. Digit Health. 2015 Jun 15;1:2055207615588395. doi: 10.1177/2055207615588395. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2055207615588395?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .10.1177_2055207615588395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simeon R, Dewidar O, Trawin J, Duench S, Manson H, Pardo JP, Petkovic J, Roberts JH, Tugwell P, Yoganathan M, Presseau J, Welch V. Behavior change techniques included in reports of social media interventions for promoting health behaviors in adults: Content analysis within a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jun 11;22(6):e16002. doi: 10.2196/16002. https://www.jmir.org/2020/6/e16002/ v22i6e16002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Välimäki M, Athanasopoulou C, Lahti M, Adams CE. Effectiveness of social media interventions for people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Apr 22;18(4):e92. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5385. https://www.jmir.org/2016/4/e92/ v18i4e92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams G, Hamm MP, Shulhan J, Vandermeer B, Hartling L. Social media interventions for diet and exercise behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2014 Feb 12;4(2):e003926. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003926. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=24525388 .bmjopen-2013-003926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn AG, Mandl KD, Coiera E. Social media interventions for precision public health: promises and risks. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:47. doi: 10.1038/s41746-018-0054-0. doi: 10.1038/s41746-018-0054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno MA, D'Angelo J. Social media intervention design: Applying an affordances framework. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Mar 26;21(3):e11014. doi: 10.2196/11014. https://www.jmir.org/2019/3/e11014/ v21i3e11014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei C, Herrick A, Raymond HF, Anglemyer A, Gerbase A, Noar SM. Social marketing interventions to increase HIV/STI testing uptake among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 07;(9):CD009337. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodyear VA, Wood G, Skinner B, Thompson JL. The effect of social media interventions on physical activity and dietary behaviours in young people and adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021 Jun 05;18(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01138-3. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-021-01138-3 .10.1186/s12966-021-01138-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Möhler R, Köpke S, Meyer G. Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2) Trials. 2015 May 03;16:204. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y. https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y .10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan E, O'Cathain A, Rousseau N, Croot L, Sworn K, Turner KM, Yardley L, Hoddinott P. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open. 2020 Apr 08;10(4):e033516. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033516. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32273313 .bmjopen-2019-033516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, Lund C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016 May 06;11:63. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6 .10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan AW, Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014 Mar 07;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010 Mar 24;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-32. https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-11-32 .1745-6215-11-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arigo D, Pagoto S, Carter-Harris L, Lillie SE, Nebeker C. Using social media for health research: Methodological and ethical considerations for recruitment and intervention delivery. Digit Health. 2018 May 07;4:2055207618771757. doi: 10.1177/2055207618771757. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2055207618771757?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .10.1177_2055207618771757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adewuyi EO, Adefemi K. Behavior change communication using social media: A review. Int J Commun Health. 2016;9:109–116. http://communicationandhealth.ro/upload/number9/EMMANUEL-O-ADEWUYI.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Althoff T, Jindal P, Leskovec J. Online actions with offline impact: How online social networks influence online and offline user behavior. WSDM 2017: Tenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; February 6-10, 2017; Cambridge, United Kingdom. 2017. Feb, pp. 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010 Feb 16;7(2):e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.How to develop a reporting guideline. The EQUATOR Network. [2022-04-08]. https://www.equator-network.org/toolkits/developing-a-reporting-guideline/

- 33.Reporting guidelines under development for other study designs. The EQUATOR Network. [2022-04-08]. https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-other-study-designs/

- 34.Black N, Murphy M, Lamping D, McKee M, Sanderson C, Askham J, Marteau T. Consensus development methods: a review of best practice in creating clinical guidelines. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1999 Oct;4(4):236–248. doi: 10.1177/135581969900400410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization . WHO Handbook for Guideline Development, 2nd Edition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaushal A, Bravo C, Duffy S, Lewins D, Möhler R, Raine R, Vlaev I, Waller J, von Wagner C. Reporting Guidelines for Social Media Research (RESOME): Study protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. doi: 10.2196/preprints.31739. Preprint posted online on July 2, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leys C, Ley C, Klein O, Bernard P, Licata L. Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013 Jul;49(4):764–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. In: Teo T, editor. Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hutchings A, Raine R, Sanderson C, Black N. A comparison of formal consensus methods used for developing clinical guidelines. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006 Oct;11(4):218–224. doi: 10.1258/135581906778476553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khodyakov D, Grant S, Denger B, Kinnett K, Martin A, Peay H, Coulter I. Practical considerations in using online modified-Delphi approaches to engage patients and other stakeholders in clinical practice guideline development. Patient. 2020 Feb;13(1):11–21. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00389-4. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31544219 .10.1007/s40271-019-00389-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]