Abstract

Rationale & Objective

People receiving maintenance hemodialysis (HD) experience significant activity barriers but desire the ability to do more and remain independent. To learn about how to help people who require dialysis stay active, a mixed methods study was designed to assess functional status and explore participants’ lived activity experiences.

Study Design

A concurrent mixed methods design was chosen to increase understanding of the real-life activity experiences of people who require dialysis through in-depth interviews paired with functional status measures. The qualitative findings were fully integrated with the quantitative results to link characteristics associated with different physical activity levels.

Setting & Participants

A purposive sample of 15 adult patients receiving maintenance HD for at least 3 months was recruited from 7 dialysis centers in Newark, New Jersey.

Analytical Approach

Thematic analysis using principles of interpretive phenomenology. Fully integrated quantitative and qualitative data with joint displays and conversion mixed methods.

Results

Participants had a median age of 58 years and were predominantly African American (83%) and men (67%). Three descriptive categories were generated about the participants. They described physical activity as a routine daily activity rather than structured exercise. All participants experienced substantial hardship in addition to chronic kidney disease and expressed that family, friends, and faith were essential to their ability to be active. An overarching theme was generated for participants’ mindsets about physical activity. Within the mindset theme, we discerned 3 subthemes comprising characteristics of participants’ mindsets by levels of engagement in physical activity.

Limitations

While code saturation and trends in functional status measures were achieved with 15 participants, a larger sample size would allow for deeper meaning saturation and statistical inference.

Conclusions

Patients receiving maintenance HD with an engaged mindset exhibited more adaptive coping skills, moved more, wanted to help others, and had a normal body weight habitus. These participants employed adaptive coping skills to carry out daily life activities of importance, highlighting the value of adaptive coping to help overcome the challenges of being physically active.

Index Words: Activities of daily living, chronic kidney disease, coping skills, engagement, functional status, hemodialysis, mindset, mixed methods research, physical activity

Plain-Language Summary.

Since people requiring dialysis struggle with physical activity, we sought to learn more about the everyday reality and physical activity aspirations of 15 people receiving maintenance hemodialysis. A functional status assessment was administered, and these measures were linked with themes generated from interviews with participants for an integrated picture of functional status and participants’ lived experiences. The participants’ mindsets about physical activity emerged as the main theme overarching 3 levels of engagement in activities of daily living. The participants with an engaged mindset exhibited more adaptive coping skills, moved more, wanted to help others, and had a normal weight body habitus. In contrast, participants with a disengaged mindset had maladaptive coping skills, infrequent activity, and obesity. The differences in participants’ mindsets provide preliminary evidence for programs such as adaptive coping and resilience support and mindset interventions.

Editorial, •

Patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis (HD) experience a suboptimal functional status marked by low physical activity levels, prolonged sitting time, sarcopenia, frailty, and a diminished health-related quality of life. Because of the disablement process associated with maintenance HD, such symptoms negatively affect an individual’s ability to perform activities of daily living and achieve the recommended amounts of exercise or physical activity and therefore impair their health-related quality of life.1,2

Structured exercise or physical activity interventions in this population3, 4, 5 have improved functional abilities, reversed sarcopenia, and enhanced health-related quality of life.5, 6, 7 Despite significant resources devoted to increasing the rehabilitative outcomes of this vulnerable population,8 considerable work remains to develop effective, sustainable, patient-centered strategies geared toward the preservation of functional status. People who require dialysis have rated the ability to do more and remain independent as the most critical outcomes for maintaining their health and wellbeing.9 Prior qualitative studies investigating this topic have identified common themes of functional disability or impairment,10, 11, 12 psychological distress,11 loss of control,12,13 and the importance of a social support network10,12, 13, 14; however, more research is warranted. Therefore, to learn more about supporting people who require dialysis to do more or remain independent, this research aimed to understand in more depth their physical activity and the barriers and facilitators for maintaining and improving their level of desired activity.

Methods

A concurrent mixed methods research design was chosen to integrate the qualitative findings with the functional status outcomes for a more comprehensive description and practical application to practice.15 A purposive sample of 15 adult patients receiving maintenance HD who were similar in demographics to the US Renal Data System population were recruited in person from 7 dialysis centers in Newark, New Jersey. Participants were eligible for the study if they were adults older than 18 years of age, had stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), and were on maintenance HD for at least 3 months before enrollment in the study. Participants were excluded if they had a significant illness, recent hospitalization, or surgery within the past 30 days. This research underwent an expedited review by the Rutgers University IRB with an approved Protocol #Pro20170000925, and written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The study coordinator (EP) obtained clinical measurements during the initial appointment, conducted a physical examination, and administered a comprehensive functional status assessment. All measurements were standardized using established protocols and taken within the research laboratory on a nondialysis treatment day at consistent time points by one assessor. An objective validated measure, the timed up-and-go test, was used to evaluate the study participant’s functional status.16 To reduce patient burden, each measurement was only taken once (timed up-and-go test and hand-grip strength) and was supervised by a licensed physical therapist (MJM). In addition to the tools used for assessing functional capacity, a subjective measure was also performed. The Human Activity Profile (HAP) is a self-administered and validated tool used to measure study participants’ abilities to perform activities of daily living that range from very easy to extremely strenuous.17

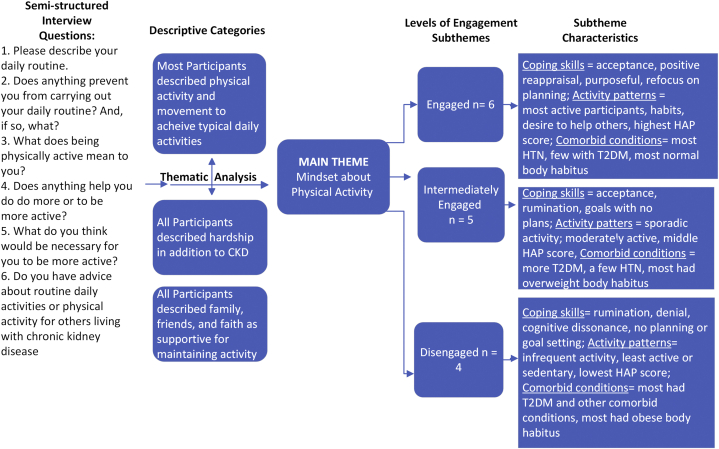

The semi-structured interview guide (Fig 1) was pilot tested with 2 persons who require maintenance dialysis. A researcher (PRP) with training and experience in qualitative research conducted the interviews from July 2018 to October 2018. She did not have a relationship with the participants before the study. The interviews took place in person at the university and took up to 1 hour to complete. Interviews were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed, and loaded into NVivo 12 software program for thematic analysis.18,19

Figure 1.

Interview guide and descriptive categories and themes generated from thematic analysis. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; HAP, Human Activity Profile; HTN, hypertension; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Analytic Approach

Thematic analysis is a systematic, inductive, and comparative data analysis method suitable for descriptive and interpretive qualitative research.19, 20, 21, 22 We used a basic interpretive qualitative research approach commonly used in health sciences20 with principles of interpretive phenomenology to understand the essence or deeper meaning of the physical activity experience from participants.20,23,24 The thematic analysis procedures are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1. Thematic Analysis Procedures.

Qualitative Data Analysis Procedures25

Data were analyzed descriptively and interpretively. The descriptive categories captured semantic meaning and included a summary of the range of what the participants said about a topic. In contrast, the interpretive themes captured latent meaning that is less obvious and based on linkages, patterns of contradiction, or dichotomization of shared meaning organized around a central concept. In other words, categories include similar data topically, and themes are conceptual and dig below the surface. These are the steps in this process:

-

•

Becoming familiar with the data by conducting the interviews and reading full transcripts

-

•

Generating initial codes by segmenting and conceptually labeling data

-

•

Making comparisons among the conceptually labeled data to cluster similar codes for the identification of a smaller number of categories

-

•

Identifying patterns and creating connections among the categories to develop themes, analytic meanings for assertions/theory development, and a storyline about the central theme

-

•

Identifying conditional paths that link attributes for the development of classifications, matrices, or typologies20,26,27

Alt-text: Box 1

Many strategies for ensuring the trustworthiness of qualitative data were employed in this study.18 Field notes and a reflective journal were kept throughout the process to consider and discuss the assumptions and biases of the research team. None of the research team require dialysis or are “insiders,” but several have years of experience working in CKD (LBG and CTH). The research team met regularly to discuss reflexivity, develop a codebook, and reach a consensus on coding and theme development (PRP, LBG, and CTH).18 The participants were not asked to provide feedback about the study design or findings. We compared participant cases on similar phenomena to focus on how they differ–a strategy deemed as indicative of quality.28 A final strategy for verifying the qualitative data analysis included triangulating the qualitative data with the quantitative functional status outcomes.

The functional status quantitative measures were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The final step in data analysis included fully integrating the qualitative and quantitative data. This was done by sorting participants into the subtheme characteristics discerned during thematic analysis. Once the participants were sorted into the subthemes, these data were converted to categorical variables to compare data and display results in joint displays such as Box 1 and Fig 1.29

Results

Fifteen participants between the ages of 26-68 years participated in the study. Two additional participants could not complete the interviews for health reasons and did not participate. Most participants (87%) were African American, 67% were men, the median age was 58 years, and participants had been on dialysis between 6 months to 10 years (Table 1). Diabetes (60%) was the primary CKD etiology.

Table 1.

Demographics, Clinical Characteristics by Mindset Level by Engagement Group (N = 15)

| Disengaged |

Intermediate Engagement |

Engaged |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Median | %/(25th Percentile, 75th Percentile) | N/Median | %/(25th Percentile, 75th Percentile) | N/Median | %/(25th Percentile, 75th Percentile) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male | 3 | 75.0% | 3 | 60.0% | 4 | 66.7% |

| Age (y) | 60.0 | (46.2, 66.8) | 57.1 | (45.1, 66.0) | 57.0 | (44.1, 66.4) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 20.0% | 1 | 16.7% |

| African American | 4 | 100.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 5 | 83.3% |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 20.0% | 1 | 16.7% |

| Etiology | ||||||

| Diabetes 1 or 2 | 4 | 100.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 1 | 16.7% |

| Smoker | 1 | 16.7% | 2 | 50.0% | 1 | 16.7% |

| Food insecure | 2 | 50.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 3 | 50.0% |

| Clinical | ||||||

| Diabetes | 4 | 100.0% | 4 | 80.0% | 1 | 16.7% |

| Hypertension | 4 | 100.0% | 2 | 40.0% | 6 | 100.0% |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 | 75.0% | 3 | 60.0% | 5 | 83.3% |

| BMI | 31.9 | (28.5, 41.4) | 29.0 | (26.0, 35.0) | 22.2 | (18.4, 35.3) |

| WH ratio | 1.0 | (.92, 1.1) | 1.0 | (.91, 1.1) | 1.0 | (.87, 1.1) |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 9.0 | (4.5, 93.0) | 48.0 | (29.5, 63.0) | 18.0 | (11.75, 81.0) |

| TUG (seconds) | 14.2 | (13.3, 18.0) | 11.6 | (10.1, 16.0) | 12.7 | (9.5, 16.1) |

| Activity | ||||||

| Human activity profile score | 44.5 | (36.5, 51.0) | 59.0 | (45.5. 76.5) | 63.0 | (57.0, 73.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; TUG, timed up-and-go test; WH, waist-to-hip ratio.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the results. Descriptive categories included information about participants’ Movement for Typical Daily Activities, Hardship, Family, Friends, and Faith. Participants’ mindsets about physical activity was the central theme generated. Within the mindset theme, we developed 3 distinct subthemes related to the participant’s level of engagement in physical activity. These subthemes included an engaged, intermediately engaged, and disengaged mindset. The participant’s mindset theme overarches and integrates the qualitative findings with some of the quantitative functional status outcomes to capture 3 categories of the participant’s mindset about their physical activity. When no new concepts were generated, code saturation was achieved at 13 interviews.30

All 15 participants described wanting to continue doing typical daily activities when asked about their current physical activities and goals. These participants also described having experienced significant adversity beyond that due to dialysis and had support from family, friends, and faith. Table 2 includes example quotes from each of these descriptive categories.

Table 2.

Descriptive Categories with Example Quotes

| Descriptive Categories | Example Quotes |

|---|---|

| Typical daily activities | (1703) “I do less physical running and less heavy lifting, but I still try to stay active, stay positive, talk to people, continue to pray, stay active in the church, and believe and do everything I can to live a normal life.” |

| Hardship | (1716) “Went to his office. Then he tell me, your prostate is shit. I know what pain it is. They did surgery in February 2013. It’s been five years and I have the catheter below my belly. That’s where they did the surgery.” (1714) “And I have lupus going on with me too, so that can be rheumatoid arthritis. So I walk a lot, because I don’t want to stiffen up with the rain and all that stuff that’s going on.” (1711) “Let me tell you. Four kids; three dead and one living. One got murdered, one had–the oldest had AIDS, and I had a stillborn baby.” (1702) “I used to live in shelters for about five, six months. I was living in shelters, and they kick you out like, the first was 7:00 in the morning, they kick you out. I had to walk around with 60-, 75-pound backpack on my back all day because I had to take everything that I had with me.” |

| Family and friends | (1706) “Well, my family got my back 100 percent.” (1718) “Yes, because my foot is amputated, and I have a big rod on this leg. So, at the time, I needed somebody to help me get around because I was in a wheelchair because of my foot. And my mom, she said that I could come to the house here and stay with her and she could help me, but she helped me a lot, her and my sister. So, I’m doing pretty good.” (1703) “The way my mother and father brought me up was never to let that [congenital anomaly] get the best of me. I would be in school, and I would come home, say oh, I’m classified as this, so I’m not going to be able to do this. And they always said no, you’re not. You can do it. Get out there with them and play with them. And now even my wife said I’m so much of a go-getter; she said she doesn’t consider me disabled. I didn’t look at that as a–I looked at that as a testament to what I try to do, so that was good to hear.” |

| Faith | (1704) “You gotta have the faith. You can’t doubt yourself because when you doubt yourself, things ain’t gonna work out for you. So that’s what I do. I have faith. Far as spiritual, God and stuff. If you ask the God upstairs, give me the faith to heal, he give you the faith to heal long as you believe it. But if you don’t believe in him, you don’t have no type of faith, it’s not gonna work.” |

The Movement to Achieve Typical Daily Activities

As opposed to structured exercise, all participants characterized their movement as daily physical activity, including lifestyle activities such as walking a dog, completing errands like grocery shopping, attending church, playing board games in a group living setting, participating in social events, going to the hairdresser, and arranging health care appointments. Two participants reported completing physical activities such as intentionally walking to build stamina, going to the gym, swimming, or walking stairs. All participants related physical activity to the movement that enables them to carry out more activities of daily living and activities to maintain their lifestyle.

Hardship

Hardship among this sample of participants requiring maintenance HD included traumatic life experiences, financial problems, housing concerns, and comorbid conditions. Every participant mentioned adverse life experiences and at least one comorbid condition such as diabetes, alcoholism, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Other types of life adversity experienced were substantial, including life-long disability, violence, homelessness, suicide attempts, financial stress, death of a spouse, child, or another close family member, teenage pregnancy, leg amputation, and immigration status difficulty. Sixty percent of the participants had experienced food insecurity. In addition to the problem of managing maintenance HD, all the participants experienced other significant trauma and adversity.

Friends, Family, and Faith

Every participant described the support of family and friends as important, expressing satisfaction with having family connections. Some participants explained that life-long family support shaped current coping skills and that this support helped them cope with requiring maintenance dialysis. In addition to family, 2 participants also mentioned the importance of their dog for their daily walking activity and companionship. Every participant remarked on the importance of faith and spirituality, and most also discussed going to church as an essential activity.

Engaged, Intermediately Engaged, or Disengaged in Activity Mindset

The participant’s mindset emerged as influencing their levels of engagement in activity. When participants spoke about their activities and HD schedules during the interviews, they expressed that living with kidney failure, which requires dialysis, is difficult and stressful; some even described it as traumatic when diagnosed. However, the participants described different activity patterns and means of coping. These patterns were linked to varying levels of activity engagement among participants falling on a continuum from engaged to intermediate engagement to disengaged. These differences in coping skills and activity patterns enabled the development of conditions for classifying participants’ activity levels into 3 levels of engagement. Table 3 depicts example quotes from each level of engagement within the mindset theme.

Table 3.

Physical Activity Mindset Level of Engagement and Example Quotes From Study Participants

| Mindset Attributes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|

| Engaged | |

| Acceptancea | (1714)”You have to make the best of it to live.” (1702) “Without this [dialysis] technology, I’d be dead. And I should have been dead a few times ago. Without me being born in this day and age, I would have died a long time ago.” |

| Positive reappraisal | (1700) “So, my daughter said, well, Ma, you gotta be careful. I said I am careful. I take my time; I take my steps as far as I can go. When I’m tired, I stop. Okay. But I just wanted to get my legs back in order again. I can’t run as fast as I used to, but I can run a little bit like that, right. But I’m so glad, with dialysis—if it wasn’t for dialysis, I don’t think I would have been here.” (1702) “I want to live. I don’t wanna survice, either. I wanna enjoy life. I realize that my attitude is mine, my attitude. Nobody’s responsible to make me happy but me. I don’t sit there and dwell on negativity.” |

| Purposeful | (1714) “So when I feel weak, I’m like no, I can’t just be down like this. I’ve got to push myself. I can’t stiffen up, and I can’t just be tired like this. I’ve got to go take care of my business. I’ve got to go. I’ve got to go take care of my business.” (1716) “When I go to do a project, or go to do some painting work, or go to just install a door, or do some plumbing job, or install a water heater, the next day. And that help me due to my condition. It help me feel good. It helps me feel real strong. Helps me feel positive.” (1706) “One of my dreams—I like to cook. That’s my—that was my passion, cooking. Pulls me outta my bed. Uncle you can cook for me? Okay. I’ll cook for you.” (1716) “I fixed a door for her. How much do I owe you? Uh-uh, no. No, nothing. No, no, no. Mm-mm. It was me. I did that from the bottom of my heart. And make me feel so good, so useful.” |

| Refocus on planning | (1702) “Make an agenda of what I need to get done. I make an agenda of prioritizing the things that I need to do, the things that I wanna do and the things that I have to do. And I usually categorize them like that, the most important first.” (1700) “I said, you gotta come better than this, you gotta do something better. So, what I did was this. I would get up out of my bed and I would hold onto the wheelchair and I would step. And I learned how to walk myself in my daughter’s house, okay. They had to carry me down the stairs. From there, they brought me into the ambulance and brought me to dialysis. And from there I said, you know what? I gotta practice on my own. So, I used to go up and down the stairs. Take my time up and down the stairs, to where I didn’t have to use the wheelchair anymore.” (1714) “But my life is different now being on dialysis because I’m taking more control. It’s not like I have to go to work. I have to come to the hospital because it’s my health, but I have a choice, too. When I was in the workforce, it was just set. So, I wasn’t really planning.” |

| Desire to help others | (1716) “And you know what I did for three months? I went 4:30 in the morning to pick her up, bring her to the clinic and take her back, for three months. And that made me feel so good.” (1703) “We have an advocacy program at my dialysis center. They asked me to be the one for Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, knowing all of this because the social worker keep telling me I don’t see how. I’m just being myself. But she keeps telling me I’m such a help to the other patients.” (1702) “When I help somebody, I really feel good. It gives me a sense of purpose.” |

| Intermediate Engagement | |

| Acceptancea | (1704) “I was upset about it, but I was like, well, I’ve got to go back—when they told me I had to go back on dialysis, they—matter of fact, the doctors didn’t want to put me back on dialysis, and I didn’t want to go back on dialysis. So they did everything they could to try to save the kidney, but it just didn’t work. So I went back on dialysis, and I said, hey, chalk it up to this. You’re still alive, kid. Deal with it.” |

| Goals with no plans | (1715) “As soon as I get my documentation, I want to start traveling. I don’t want to be stuck in just one place. I want to be six months here, six months in Brazil. I want to be like—travel. I want to change my life. I don’t want to be like this—getting too depressing so easy now. I don’t want to—I want to put some motivation in my life. I want to have something to do. So, I’m going to keep on traveling.” |

| Ruminationb | This participant talks about his desire to drive five times during the interview. (1707) “So when I would, like if somebody let me drive, I’m like okay. I’m like I can prove to you that I can still drive. I can show you that right now. So I’ll show them, and I’m like okay. I can drive. But they’re like but you’re not medically cleared. You’ve got to wait until you get your kidney, and I’m like but I just proved to you that I can drive. I’m like ‘I have a license. Can I just have the keys?’ That’s all. And even if somebody said well, I’m going to come with you—okay. I have no problem with that. But I want to drive.” |

| Disengaged | |

| Ruminationb | (1711) “I feel disabled. I really am disabled, but I feel disabled more. Yeah. Because I can’t do the things I wanna do now. Can’t do the things. I can’t walk three blocks.” |

| Denial | (1709) “I don’t let—I’m with my normal life before this happened. It doesn’t bother me and I won’t think about it. I don’t have no purpose.” (1721) “I don’t even wanna think about it. I think about my normal life.” |

| Cognitive dissonance | (1721) “I’m not sure. Well, I got a son and I don’t want him to see me all down and out, so I just keep it cheerful, keep moving, keep it going.” Interviewer: So, you want to show your son you’re strong? “Yeah. I don’t wanna—this is somethings that is down and bad. So, just keep a little cheerful part.” Interviewer: But what do you do when you don’t feel so cheerful? “TV. Phone. Other than that, I’m already motivated and happy.” |

| No planning or goal setting | No quotes |

Acceptance is an attribute in the engaged and intermediately engaged mindset

Rumination is an attribute in the intermediately engaged and disengaged mindset

Below we describe the adaptive and maladaptive coping skills that characterize the different engagement groups. We also describe the linkages between these engagement groups and the level of activity and functionality.

Engaged Participants

Participants classified as having an engaged mindset distinguished themselves by reporting a more extensive repertoire of adaptive coping skills, including positive reappraisal, purposiveness, and a refocus on planning. Other distinguishing attributes identified in participants with an engaged mindset included habitual activity patterns and the desire to help others.

Acceptance

Participants in the engaged activity group described an acceptance of the CKD diagnosis and maintenance HD as a part of life—a trait shared with individuals in the intermediately engaged group. These individuals adjusted to their “new normal” and assimilated treatment into their lifestyle. Acceptance for some individuals was more pragmatic and indicated that they understood the benefit of the maintenance HD technology, while others acknowledged that accepting their diagnosis took time.

Positive Reappraisal

Engaged participants described reframing maintenance HD positively and manifested a desire to move forward with optimism and a belief about their capabilities. The reframing is combined with acceptance and includes elements of personal growth and creating new standards to achieve.

Purposeful

Engaged participants were purposeful in their involvement in activity. Many participants wanted to do more and were intentional about increasing their activity. In addition, some engaged participants also described performing an activity to feel better. Similarly, other engaged participants viewed activity to feel a sense of purpose.

Refocus on Planning

All participants classified with an engaged mindset sought resolutions by planning and using strategies to achieve their goals. Planning included deliberate agenda setting and daily planning to complete the next step in reaching their goals. Several participants were determined to do a little more each day. One participant worked each day to walk on her own to live independently again. One participant indicated that dialysis enabled him to plan and take control of his day more than when he was in the workforce with a set schedule.

Desire to Help Others

The desire to help others emerged as a strong pattern among engaged participants. When participants described helping others, they characterized it as providing a sense of purpose and increasing self-efficacy. Participants described how helping friends and family makes them feel good about themselves and provides a sense of purpose. Other participants shared how they help other people during maintenance HD.

Habitual Activity Patterns

Engaged participants described patterns of resilience and determination to continue activity each day despite significant challenges. In this study, higher median HAP scores (indicating higher self-reported physical activity levels) were associated with increased engagement compared with those in the immediate or disengaged groups (63.0, 59.0, and 44.5, respectively). In addition, they could perform the timed up-and-go test quicker than disengaged participants. Many participants talked about remaining active each day to maintain independence, and most talked about striving to do more even when it is difficult or when they feel weak.

Intermediately Engaged Participants

Intermediately engaged participants are distinguished by describing both adaptive and maladaptive coping skills. Like the engaged participants, acceptance emerged as a pattern of adaptive coping. Most intermediately engaged participants expressed acceptance of the CKD diagnosis and maintenance HD. The maladaptive coping behaviors evident among intermediately engaged participants included goals with no plans and rumination.

Goals With No Plans

Many intermediately engaged participants described goals for the future but did not discuss a plan to achieve them. These goals included accomplishing different activities like swimming, working part-time, or driving. However, these participants were not actively engaged in these activities and indicated no clear plans for making them a reality.

Rumination

Intermediately engaged participants spoke numerous times about the difficulties they faced. At almost every question in the interview, these participants circled back to the adverse circumstances. Examples of their rumination included dismay over the lack of independence, treatment and lifestyle restrictions, and issues with a home health aide. Two participants expressed the desire to drive but could not because of immigration or health issues. Other participants ruminated over not eating the foods they wanted, travel restrictions caused by dialysis, and the need for a home health aide.

Sporadic Activity Patterns

Intermediately engaged participants reported activity patterns consistent with a HAP score indicating moderate activity levels. As opposed to the engaged participants (where activity is habitual and part of the lifestyle), the intermediately engaged participants described both adaptive and maladaptive coping skills. Barriers to exercise included sleep disruptions, arthritis, and a dislike of exercise. Sleep disruption was the most common reason for lack of activity. Most participants described arising very early in the morning, sometimes at 3 or 4 AM, to get ready and wait for transportation to dialysis. They do not adjust this pattern on a nondialysis treatment day. Many people also talked about sleep difficulty, and several mentioned only getting a few hours of sleep at night and then napping throughout the day. The most prominent activity described by these participants included a commitment to attend every dialysis session. Other participants relayed that exercise made them feel better when they did it, and one participant described trying to exercise so that he would be eligible for a kidney transplant.

Disengaged Participants

Disengaged participants are distinguished by demonstrating more maladaptive behaviors and ways of thinking. Like the participants in the intermediately engaged group, the disengaged participants also exhibited maladaptive rumination. The maladaptive coping exclusively within this level of engagement included denial, cognitive dissonance, and no planning or goal setting. Another distinguishing characteristic of disengaged individuals was infrequent activity patterns due to feeling unwell or disabled.

Denial

Disengaged individuals expressed despondency and tended to act as if their CKD did not exist. Many participants did not want to accept the reality of requiring maintenance HD.

Cognitive Dissonance

There were many instances where disengaged participants were inconsistent with their descriptions of daily activity. For example, one participant talked about not feeling well and not taking medication in one part of the interview. In another part of the interview, he claimed he took his medication every day without fail.

No Planning or Goals Setting

Disengaged participants provided no discussion about planning or goal setting. Even when asked about potential or prospective activities, these participants offered no further discussion or plans to do so in the future.

Infrequent Activity Patterns

Disengaged participants described more sedentary regular activities like reading or watching television. Based on the timed up-and-go and HAP scores, individuals with a disengaged mindset were the least physically active and had the lowest mobility compared with the intermediately engaged and disengaged. Also, disengaged individuals had a higher median body mass index than the other engagement groups (Table 1). At every level of engagement, participants discussed not feeling well or not doing what they used to do. Still, the disengaged participants described more instances where they could not be active due to disability associated with maintenance HD.

Discussion

The participants with an engaged mindset exhibited more adaptive coping skills, moved more, wanted to help others, and had a normal body weight habitus. These participants employed adaptive coping skills to carry out daily life activities of importance. These findings closely align with other studies involving people requiring maintenance HD where adaptive coping such as accepting dialysis as a lifestyle change and a flexible mindset helped patients overcome the challenges of being physically active.31,32 The findings are also in accord with The World Kidney Day Steering Committee advocacy for the inclusion of life participation as a health care goal in CKD.33

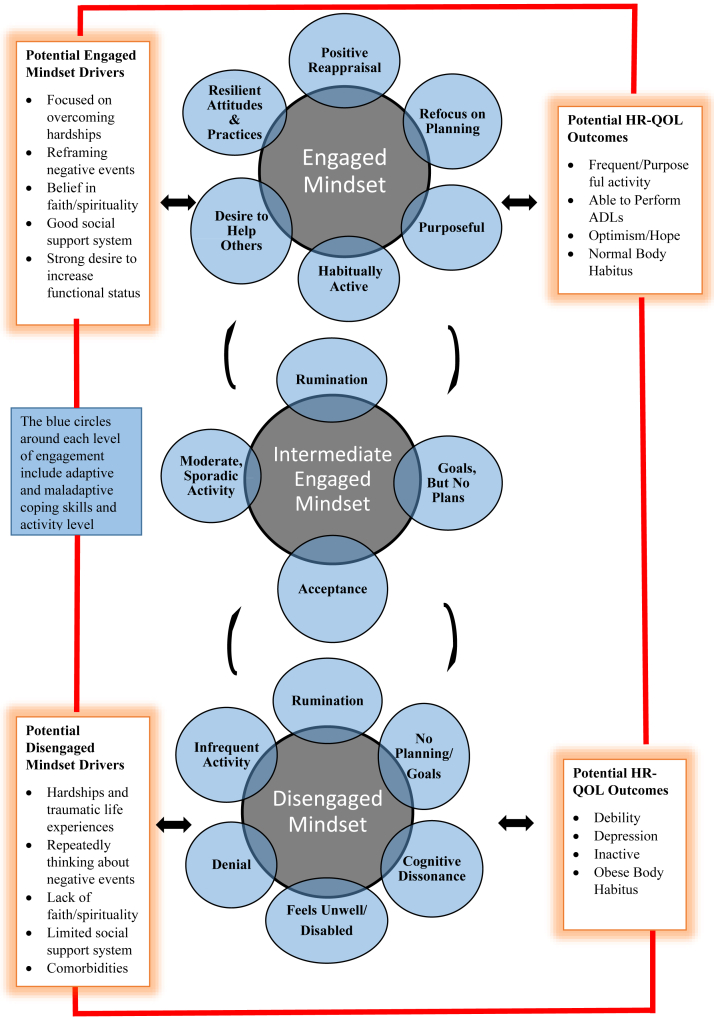

The differences (Fig 2) in participants’ mindsets about physical activity highlight the difficulty of activity for some people requiring dialysis and were clinically meaningful. We found that the participants with a disengaged mindset about movement had maladaptive coping skills, infrequent activity, multiple comorbid conditions, and obese body habitus. We know that CKD is linked with muscle impairment and functional limitations that may inhibit activity,34 and comorbid conditions and obesity may compound this problem. Adaptive coping strategies may prevent comorbid conditions and obesity since coping skills and resilience are modifiable factors to change thinking and behavior for people requiring dialysis to increase physical activity and live well.35, 36, 37 In line with this, Gillanders et al38 studied affect, social functioning, and wellbeing outcomes for 106 people requiring maintenance HD with reappraisal (flexible cognition to reframe a stressor) or suppression (blocking or hiding distress) emotional regulation skills. They found that cognitive reappraisal, especially early, was correlated with more positive emotions, less anxiety, and reduced behavioral disengagement.38

Figure 2.

Coping skills that may be associated with levels of activity engagement for patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

The differences in participants’ mindset and engagement level in activity also raise questions about underlying causes such as life course factors, sociocultural influences, and fatigue. Fatigue constrains the ability to participate in life activities,39 and it is essential to learn more about whether physical activity may lessen fatigue.32 Subramanian et al40 found coping strategies such as expressing emotion, having a social support system, problem-solving, and cognitive restructuring was linked to positive outcomes in contrast to the participants who described maladaptive strategies including social withdrawal, problem avoidance, and wishful thinking. As with our findings, others have described the benefits of helping others through volunteerism,41,42 highlighting the importance of purpose and social connection. Despite the significant hardship described by participants in this study, all individuals described protective factors such as having friends, family, and faith-based support as important. These findings are consistent with prior qualitative studies conducted by Hall et al,10 Raj et al,13 and Aghakhani et al,14 which found that social support was an essential health-related quality of life indicator in older adults receiving maintenance HD.

It may be helpful to assess coping strategies and physical activity mindset to promote targeted interventions for people requiring maintenance HD. Further research is needed to identify the assessment tools and interventions associated with significant clinical and social outcomes. Still, there is evidence that people receiving maintenance HD can relearn and adjust coping strategies through mindset interventions.36, 37, 38,43 Subramanian et al40 describe cognitive restructuring where participants reframed their CKD diagnosis and circumstances into a more positive light. Cognitive restructuring aligns with our findings and others about the positive reappraisal demonstrated by engaged participants.43

Participants reported everyday daily activities like grocery shopping and attending dialysis. Most participants also described activities associated with self-care and social events such as going to church, playing games in the community recreation room, and going to the barber or hair salon. The activities that these participants described were not part of a typical exercise or training program recommended for improving exercise tolerance in people requiring dialysis.44 However, they are consistent with the recommendations for increasing overall physical activity versus formal exercise programs for people requiring maintenance HD.32

These findings indicate that exercise programs for people receiving maintenance HD need a personalized approach to strength and endurance training to maintain activities of daily living. Activities of daily living are essential for people who require maintenance HD to continue to maintain their independence and are rated as one of the most critical health outcomes by patients.9 Some options such as intradialytic exercise, yoga, ergonomic cycles, and others have shown positive health changes;45, 46, 47, 48, 49 however, effects vary depending on the participant’s level of motivation.50, 51, 52

By being sensitive to different mindset characteristics, health care providers can develop a personalized treatment plan to address potentially modifiable risk factors or drivers of disengagement. Patients who lack an actively engaged support network could benefit from joining a peer support group.53 They could also be encouraged to participate in a faith-based counseling program for spiritual support and guidance. Individuals requiring dialysis who are disengaged due to homelessness or unemployment may benefit from a shelter or career planning center referral. Patients should be encouraged to pursue volunteerism when they exhibit a desire to help others or participate in a rehabilitative program if they have CKD disablement.54,55

The strengths of this study include a fully integrated mixed methods research design, in-depth interviews to understand better the lived experience of people who require maintenance HD, researchers with extensive experience in CKD, and qualitative or mixed methods research. Limitations include a small sample size that precludes generalizability. The sample was predominantly male and African American, an understudied minority group, but the qualitative findings may only be transferable to a similar population. While numerous trustworthiness steps were taken, participants were not asked to review the transcripts or conclusions. Coding saturation was met, but a larger sample would achieve deeper meaning saturation and statistical power to detect differences in the participants’ physical activity mindset levels of engagement. Additionally, people use different coping skills at other times, and these data are cross-sectional and collected at one point. Lastly, in terms of activity patterns (HAP score), these values were self-reported and may be either over- or underestimated depending on the perceptions of the individual.

These findings provide preliminary support for identifying and characterizing the mindset and levels of engagement in activity for people requiring maintenance HD and have implications for future research in assessing coping skills. Since coping skills are modifiable, the findings may also provide preliminary evidence for programming for people requiring maintenance HD to include volunteering opportunities and mindset interventions such as coping and resilience training.36,37

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Pamela Rothpletz-Puglia, EdD, RDN, Terry Brown, MBA, MPH, RD, CNSC, Emily Peters, MPH, Charlotte Thomas-Hawkins, PhD, RN, Joshua Kaplan, MD, Mary J. Myslinski, PT EdD, JoAnn Mysliwiec, DPT, James S. Parrott, PhD, and Laura Byham-Gray, PhD, RDN, FNKF

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: LBG, PRP, MJM; data acquisition: EP, JM, PRP; data analysis/interpretation: PRP, LBG, CTH, TLB; statistical analysis: TLB, JSP; supervision or mentorship: JK, LBG. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This project was supported by K18HS023434 from the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Peer Review

Received November 19, 2021 as a submission to the expedited consideration track with 2 external peer reviews. Direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form February 20, 2022.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Soni R.K., Weisbord S.D., Unruh M.L. Health-related quality of life outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(2):153–159. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328335f939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mujais S.K., Story K., Brouillette J., et al. Health-related quality of life in CKD patients: correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(8):1293–1301. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05541008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Headley S.A., Hutchinson J.C., Thompson B.A., et al. A personalized multi-component lifestyle intervention program leads to improved quality of life in persons with chronic kidney disease. medRxiv. 10.1101/19007989 Preprint posted online October 2, 2019.

- 4.Filipčič T., Bogataj Š., Pajek J., Pajek M. Physical activity and quality of life in hemodialysis patients and healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1978. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirai K., Ookawara S., Morishita Y. Sarcopenia and physical inactivity in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrourol Mon. 2016;8(3) doi: 10.5812/numonthly.37443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu Y., Wang Y., Lu Q. Effects of exercise on muscle fitness in dialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2019;50(4):291–302. doi: 10.1159/000502635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheema B., Abas H., Smith B., et al. Progressive exercise for anabolism in kidney disease (PEAK): a randomized, controlled trial of resistance training during hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(5):1594–1601. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Life Options Rehabilitative Advisory Council. Building Quality of Life: A Practical Guide to Renal Rehabilitation. Medical Education Institute, Inc. Published 1997. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://lifeoptions.org/assets/pdfs/qualoflife.pdf

- 9.Byham-Gray L.D., Peters E.N., Rothpletz-Puglia P. Patient-centered model for protein-energy wasting: stakeholder deliberative panels. J Ren Nutr. 2020;30(2):137–144. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall R.K., Cary M.P., Jr., Washington T.R., Colón-Emeric C.S. Quality of life in older adults receiving hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(3):655–663. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02349-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones D.J., Harvey K., Harris J.P., Butler L.T., Vaux E.C. Understanding the impact of haemodialysis on UK National Health Service patients’ well-being: a qualitative investigation. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1-2):193–204. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberti J., Cummings A., Myall M., et al. Work of being an adult patient with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raj R., Brown B., Ahuja K., Frandsen M., Jose M. Enabling good outcomes in older adults on dialysis: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-1695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aghakhani N., Sharif F., Molazem Z., Habibzadeh H. Content analysis and qualitative study of hemodialysis patients, family experience and perceived social support. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(3) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.13748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark V.L.P., Ivankova N.V. Vol. 3. Sage Publications; 2015. (Mixed Methods Research: A Guide to the Field). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leal V.O., Mafra D., Fouque D., Anjos L.A. Use of handgrip strength in the assessment of the muscle function of chronic kidney disease patients on dialysis: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(4):1354–1360. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen K.L., Painter P., Kent-Braun J.A., et al. Validation of questionnaires to estimate physical activity and functioning in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;59(3):1121–1127. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nowell L.S., Norris J.M., White D.E., Moules N.J. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merriam S.B., Tisdell E.J. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2016. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guest G., MacQueen K.M., Namey E.E. SAGE; 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall C., Rossman G.B. 6th ed. SAGE; 2016. Designing Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norlyk A., Harder I. What makes a phenomenological study phenomenological? An analysis of peer-reviewed empirical nursing studies. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(3):420–431. doi: 10.1177/1049732309357435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahlke R.M. Generic qualitative approaches: pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. Int J Qual Methods. 2014;13(1):37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V., Clarke V. SAGE; 2022. Thematic Analysis A Practical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxwell J. SAGE; 2012. A Realist Approach to Qualitative Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miles M.B., Huberman M.A., Saldana J. 4th ed. SAGE; 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamont M, White P. Workshop on interdisciplinary standards for systematic qualitative research. In National Science Foundation Workshop; May 19, 2005.

- 29.Teddlie C., Tashakkori A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE; 2009. The analysis of mixed methods data; pp. 251–284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennink M.M., Kaiser B.N., Marconi V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C.K., Seo J., Lee D., et al. Mobility in older adults receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(4):539–548.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jhamb M., McNulty M.L., Ingalsbe G., et al. Knowledge, barriers and facilitators of exercise in dialysis patients: a qualitative study of patients, staff and nephrologists. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):192. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0399-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalantar-Zadeh K., Li P.K.T., Tantisattamo E., et al. Living well with kidney disease by patient and care-partner empowerment: kidney health for everyone everywhere. Kidney Med. 2021;99(2):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roshanravan B., Gamboa J., Wilund K. Exercise and CKD: skeletal muscle dysfunction and practical application of exercise to prevent and treat physical impairments in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(6):837–852. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manning L.K., Carr D.C., Kail B.L. Do higher levels of resilience buffer the deleterious impact of chronic illness on disability in later life? Gerontologist. 2016;56(3):514–524. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jamieson J.P., Crum A.J., Goyer J.P., Marotta M.E., Akinola M. Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: an integrated model. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2018;31(3):245–261. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2018.1442615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamieson N.J., Hanson C.S., Josephson M.A., et al. Motivations, challenges, and attitudes to self-management in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(3):461–478. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillanders S., Wild M., Deighan C., Gillanders D. Emotion regulation, affect, psychosocial functioning, and well-being in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):651–662. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson J., Ju A., Baumgart A., et al. Patient perspectives on the meaning and impact of fatigue in hemodialysis: a systematic review and thematic analysis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(2):179–192. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian L., Quinn M., Zhao J., Lachance L., Zee J., Tentori F. Coping with kidney disease—qualitative findings from the Empowering Patients on Choices for Renal Replacement Therapy (EPOCH-RRT) study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0542-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kail B.L., Carr D.C. Successful aging in the context of the disablement process: working and volunteering as moderators on the association between chronic conditions and subsequent functional limitations. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;72(2):340–350. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson N.D., Damianakis T., Kröger E., et al. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: a critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(6):1505–1533. doi: 10.1037/a0037610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barberis N., Cernaro V., Costa S., et al. The relationship between coping, emotion regulation, and quality of life of patients on dialysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2017;52(2):111–123. doi: 10.1177/0091217417720893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams G.R., Vaziri N.D. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in chronic renal failure: effects of exercise. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(4):F753–F761. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00296.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett P.N., Fraser S., Barnard R., et al. Effects of an intradialytic resistance training programme on physical function: a prospective stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(8):1302–1309. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsufuji S., Shoji T., Yano Y., et al. Effect of chair stand exercise on activity of daily living: a randomized controlled trial in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2015;25(1):17–24. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandey R.K., Arya T.V., Kumar A., Yadav A. Effects of 6 months yoga program on renal functions and quality of life in patients suffering from chronic kidney disease. Int J Yoga. 2017;10(1):3–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.186158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yurtkuran M., Alp A., Yurtkuran M., Dilek K. A modified yoga-based exercise program in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15(3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogataj Š., Pajek J., Ponikvar J.B., Hadžić V., Pajek M. Author Correction: Kinesiologist-guided functional exercise in addition to intradialytic cycling program in end-stage kidney disease patients: a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10399. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang S.H., Do J.Y., Jeong H.Y., Lee S.Y., Kim J.C. The clinical significance of physical activity in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42(3):575–586. doi: 10.1159/000480674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heiwe S., Jacobson S.H. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(3):383–393. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilund K.R., Viana J.L., Perez L.M. A critical review of exercise training in hemodialysis patients: personalized activity prescriptions are needed. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2020;48(1):28–39. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Kidney Foundation. PEERS Lending Support. Published 2021. Accessed July 23, 2021. https://www.kidney.org/professionals/Peers

- 54.Tawney K.W., Tawney P.J.W., Kovach J. Disablement and rehabilitation in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2003;16(6):447–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2003.16097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kolewaski C.D., Mullally M.C., Parsons T.L., Paterson M.L., Toffelmire E.B., King-VanVlack C.E. Quality of life and exercise rehabilitation in end stage renal disease. CANNT J. 2005;15(4):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]