Abstract

Background:

In 2020, San Francisco, CA amended an ordinance requiring warning labels on advertisements for sugary drinks to update the warning message. No studies have evaluated consumer responses to the revised message.

Objectives:

To evaluate responses to the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label and to assess whether these responses differ by demographic characteristics.

Design:

Randomized experiment.

Participants/setting:

In 2020, a convenience sample of US parents of children ages 6 months-5 years (n=2,160 included in primary analyses) was recruited via an online panel to complete a survey. Oversampling was used to achieve a diverse sample (49% Hispanic/Latino(a), 34% non-Hispanic Black, 9% non-Hispanic White).

Intervention:

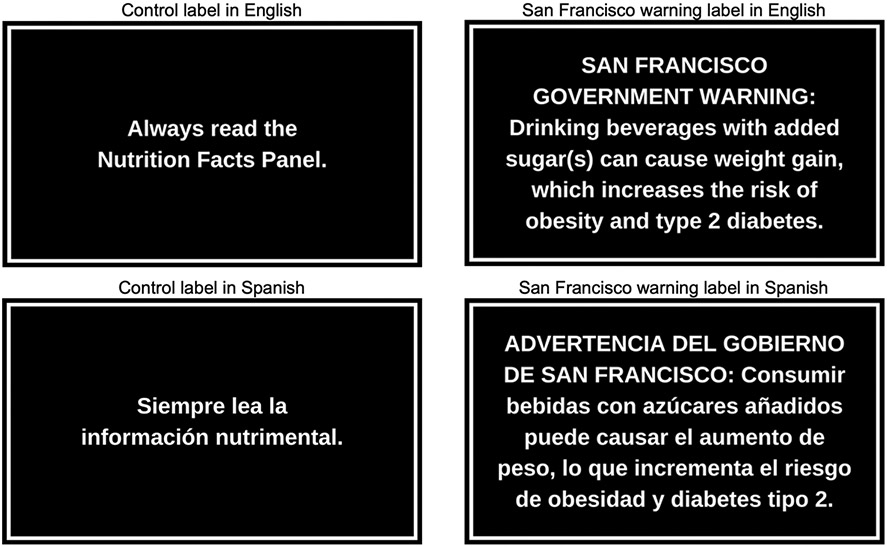

Participants were randomly assigned to view a control label (“Always read the Nutrition Facts Panel”) or the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label (“SAN FRANCISCO GOVERNMENT WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) can cause weight gain, which increases the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.”). Messages were shown in white text on black rectangular labels.

Main outcome measures:

Participants rated the labels on thinking about health harms of sugary drink consumption (primary outcome) and perceived discouragement from wanting to consume sugary drinks. The survey was available in English and Spanish.

Statistical analyses performed:

Ordinary least squares regression.

Results:

The San Francisco warning label elicited more thinking about health harms (Cohen’s d=.24, p<0.001) than the control label. The San Francisco warning label also led to more discouragement from wanting to consume sugary drinks than the control label (d=.31, p<0.001). The warning label’s impact on thinking about harms did not differ by any participant characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, or language of survey administration (all p-values for interactions>0.12).

Conclusions:

San Francisco’s 2020 sugary drink warning label may be a promising policy for informing consumers and encouraging healthier beverage choices across diverse demographic groups.

Keywords: Sugary drinks, sugar-sweetened beverages, warnings, policy, randomized experiment

Introduction

Consumption of drinks with added sugar (“sugary drinks”) remains well above recommended levels among both children and adults in the US.1-3 Sugary drink consumption is associated with obesity, tooth decay, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.4-8 One promising policy for reducing sugary drink consumption in both children and adults is requiring health warning labels on sugary drink advertisements and product packaging. In 2015, San Francisco, California became the first US jurisdiction to adopt a sugary drink warning label policy when it passed an ordinance requiring warning labels on sugary drink advertisements displayed in the city.9 In 2020, the city revised the message to be displayed on the warning label in response to court challenges.10-12 The 2020 warning message reads, “SAN FRANCISCO GOVERNMENT WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) can cause weight gain, which increases the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.”9 This language differs from other proposed warning labels in the US12-17 in its causal language (using “can cause” and “increases the risk of” instead of “contributes to”), its inclusion of weight gain and exclusion of tooth decay as possible consequences of sugary drink consumption, and its two-part construction linking weight gain to other health outcomes. Prior research suggests that these differences could affect how consumers respond to the warning labels,18,19 but no research has empirically evaluated the 2020 San Francisco warning message.

Warning labels are considered ‘compelled’ commercial speech (i.e., the government is mandating that companies display the warning label) and can be challenged on First Amendment grounds. Typically, courts will apply the Zauderer test to determine whether warning labels can be compelled.11 Among other criteria, this test requires that warning labels must be “reasonably related” to government interests such as informing consumers or improving public health.20 Studies of other warning labels proposed in the US have generally found that warning labels inform consumers about the risks of sugary drinks and discourage sugary drink consumption.21-30 In anticipation of possible legal challenges and to inform potential sugary drink warning label legislation in other jurisdictions, more research is needed to understand whether the 2020 San Francisco warning label exerts similar effects.

Sugary drink consumption and its negative impacts are inequitably distributed by race/ethnicity, education, and income,1,31-36 and researchers and advocates therefore want to know whether the effects of sugary drink warning labels differ across key demographic groups.37-40 If warning labels have larger beneficial impacts for already-advantaged groups, warning label policies could exacerbate underlying health disparities. In contrast, one modeling study found that if warning labels are similarly effective across diverse populations, warning label policies could reduce sociodemographic disparities in obesity prevalence.27 To date, however, no studies have evaluated the impact of the 2020 San Francisco warning label across different demographic groups.

To address these gaps and inform ongoing policy and legal debates about sugary drink warning labels, this study aimed to evaluate reactions to the revised 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label among US parents of young children, and to examine whether these reactions differed across key population groups relevant for warning labels’ impacts on health equity. Parents are a particularly important group to address in warning label research, as their diet-related behaviors influence both their own and their children’s health.41 Parents of young children (i.e., under age five) are an especially important population because dietary habits in early childhood are predictive of both diet and health outcomes later in childhood and into adolescence.42-45 This study focused on the extent to which the 2020 San Francisco warning label led consumers to think more about the harms of sugary drinks and discouraged them from wanting to consume sugary drinks because previous studies have found that changes in thinking about health effects46,47 and perceived message effectiveness48-55 are associated with actual behavior change. Thus, these measures have predictive value as to the 2020 San Francisco warning label’s potential to elicit behavior change.

Methods

Prior to data collection, we pre-registered study hypotheses and statistical analyses on AsPredicted.org (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=zq7qa4). The only deviations from this plan were that (1) we conducted an unplanned moderation analysis examining whether the warning label’s effect differed by income, based on peer reviewer feedback, and (2) analyses excluded participants who completed the survey implausibly quickly (i.e., completion time <7.5 minutes [approximately half of the median completion time in the soft launch of the survey]; this exclusion did not affect the pattern of results).

Participants

This study used a national convenience sample of 2,164 adults recruited by Dynata, a survey technology company commonly used by researchers. Dynata provides access to pools of millions of participants the company has recruited through recruitment campaigns, direct emails, and online marketing channels. Prior research shows that online convenience samples yield highly generalizable findings for experiments like the one used in this study.56 Participants in this experiment were recruited as part of a larger, multipart survey study that examined behavior and decision-making in response to experimental stimuli and real-world events. Participants were eligible for the survey if they were age 18 or older, lived in the US, and were a parent or caregiver (hereafter ‘parent’) to at least one child ages six months to five years. Because sugary drink consumption varies by race and ethnicity,1 we established recruitment quotas to ensure that at least 25% of participants would identify as Hispanic or Latino(a) and at least 25% would identify as Black (not mutually exclusive).

Dynata recruited participants to complete the multipart survey by sending email invitations to individuals in their online panel. Email invitations contained only generic information about the survey’s length and incentive amount and a hyperlink to complete the survey; no information was provided about the topic or goals of the survey. Interested participants could complete the survey online by following the hyperlink.

The primary study in the multipart survey focused on parents’ reactions to health and school-readiness messages embedded in children’s storybooks. For that study, we established a target sample size of ~2,100 participants with complete data. Recruitment began on May 8, 2020 and continued until May 25, 2020, when the target sample size was achieved. The Harvard Longwood Campus Institutional Review Board approved this study Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB Protocol #19-1790).

Procedures

The present experiment was embedded in a multipart survey study programmed in Qualtrics. In the survey, participants first provided informed consent and answered one screening question to determine whether they had a child in the target age range. Next, participants answered survey items that were conceptually unrelated to the present experiment, including an experiment about storybook messages, survey questions about reading to their children, and survey questions about their vaccination behaviors and intentions.57 Participants then completed the experiment described in the present study. Finally, participants reported demographic characteristics. The median response time for the entire multipart survey was 14.4 minutes. Dynata provided participants who completed the survey with previously agreed upon incentives in the form of reward points redeemable for gift cards, charitable contributions, or partner products and services; Dynata determined the amount of each participant’s incentive based on the length of the survey and the participant’s characteristics (i.e., the mutually agreed upon incentives may have varied across participants). Participants could choose to take the survey in English or Spanish. A professional translation company translated survey items and experimental stimuli from English to Spanish.

Experiment

In the present experiment, participants were randomly assigned to view a control label or the San Francisco warning label. The control message read “Always read the Nutrition Facts Panel,” similar to a previous study28 (Figure 1). The San Francisco warning message was identical to the message in San Francisco’s 2020 ordinance.10 Messages were shown in white text on black rectangular labels. Randomization was implemented using Qualtrics survey software using simple randomization in a 1:1 allocation ratio. Random assignment in the present experiment about warning labels was independent of assignment to experimental conditions in the prior experiment about storybook messages, and there were no interactions between participants’ group assignment in the two experiments for the primary or secondary outcomes (p-values for interactions>0.45).

Figure 1.

Control label and San Francisco warning label used in the online randomized experiment

Measures

Participants rated their randomly assigned label using measures adapted from previous studies. The primary outcome was thinking about the health harms of sugary drink consumption, assessed with a single item adapted from previous studies,28,58,59 “How much does this label make you think about the health problems caused by sugary drinks?” The secondary outcome was perceived message effectiveness, also assessed with a single item adapted from previous studies,28,60 “How much does this label discourage you from wanting to drink sugary drinks?” Both measures used a 5-point response scale, ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (A great deal). We selected these outcomes because they are sensitive to differences in message design and predictive of actual behavior change.46-48,50,51 Moreover, a stated goal of most sugary drink warning label policies proposed in the US is to promote consumer understanding of sugary drinks’ health harms.10,13-17 Warning labels that increase thinking about health harms could help inform consumers by keeping these harms at top of mind as they make purchase decisions.61

The survey also assessed standard demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity). Survey measures appear in Table 1 (online only).

Table 1.

Survey items used in online randomized experiment evaluating the impact of the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label

| Construct | Item | Response scale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco Warning Label Experiment | |||

| Prompt 1 | The city of San Francisco and five U.S. states have proposed requiring warning labels on sugary drinks like sodas, fruit drinks, sports drinks, sweetened teas and coffees, and energy drinks. On the next page, you will look at a label for sugary drinks and answer questions about the label. | ||

| Prompt 2 |

Please read the label closely. Then answer the questions below.

|

||

| Stimuli | [Randomly assign participants to 1 or 2 conditions 1 = Control condition showing a rectangle reading “Always read the Nutrition Facts Panel” 2 = Warning condition showing a rectangle reading, “SAN FRANCISCO GOVERNMENT WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) can cause weight gain, which increases the risk of obesity and diabetes.”]. |

||

| Thinking about the health harms of sugary drinks* | How much does this label make you think about the health problems caused by sugary drinks? | 1 = Not at all 2 = Very little 3 = Somewhat 4 = Quite a bit 5 = A great deal |

Adapted from prior studies58,59,66 |

| Perceived message effectiveness** | How much does this label discourage you from wanting to drink sugary drinks? | 1 = Not at all 2 = Very little 3 = Somewhat 4 = Quite a bit 5 = A great deal |

Adapted from prior studies60,66 |

| Demographics & Health Behaviors | |||

| Prompt | The next questions are about you and your household. | ||

| Annual household income | Which of the following categories best describes your total household income in the last 12 months? It’s fine to make your best guess. | 1= Less than $10,000 2= $10,000 to $14,999 3= $15,000 to $24,999 4= $25,000 to $34,999 5= $35,000 to $49,999 6= $50,000 to $74,999 7= $75,000 to $99,999 8= $100,000 to $149,999 9= $150,000 to $199,999 10= $200,000 or more |

Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study79 |

| Number of household members who depends on this income (household size) | How many people depend on this income, including you? | # of people [restricted to 1-20] | USDHHS 2016 |

| Number of children | How many children under the age of 18 live in your household? | # of children [restricted to 0-20] | NA |

| SNAP participation | In the last 12 months, did you or any member or your household receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits? These benefits are sometimes also called Food Stamps. | 0=No 1=Yes |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey80 |

| WIC participation | In the last 12 months, did you or any member or your household receive benefits from the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program? | 0=No 1=Yes |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey80 |

| Education | What is the highest level of school you have completed? | 1=Less than high school or U.S. high school equivalent (GED) 2=High school diploma or U.S. high school equivalent (GED) 3=Some college 4=2-year college degree 5=4-year college degree 6=Master’s degree, graduate degree, or more |

|

| Race of participant | What is your race? Please check all that apply. | [Select all that apply] 1=White 2=Black or African American 3=American Indian or Alaska Native 4=Asian 5=Pacific Islander 6=Another race: _________ |

|

| Hispanic ethnicity of participant | Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin? | 0 = No 1= Yes |

2010 Census |

| Age of parent/caregiver | What is your age? | _____ | |

| Parent/caregiver gender | What is your gender? | 1=Man 2=Woman 3=Transgender 4=Nonbinary 5=Another option not listed: [Text box] |

|

Note. Only questions relevant to the present study are shown.

Primary Outcome

Secondary Outcome

Statistical Analysis

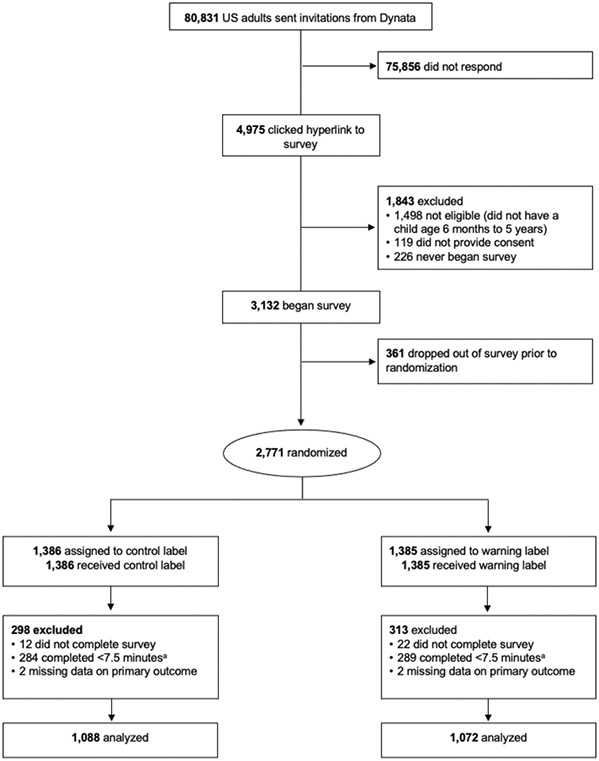

The analytic sample included 2,160 participants who completed the survey, had data on the primary outcome, and passed a quality control check to exclude those with improbably fast completion times (Figure 2 [online only]).

Figure 2. CONSORT flow diagram for an online randomized experiment evaluating the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label.

aLess than half of median response time in a soft launch of the survey.

We predicted that the San Francisco warning label would elicit more thinking about health harms and higher perceived message effectiveness than the control message. Analyses used ordinary least squares linear regression models to test these predictions. Models regressed the outcome on an indicator variable for message arm (San Francisco warning label vs. control). To allow for comparison of effects across outcomes, we report treatment effects both as unstandardized regression coefficients (Bs) and as standardized mean differences (Cohen’s ds). Cohen’s ds of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively.62

Analyses also examined whether six participant characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, income, and language of survey administration) moderated the relationship between message arm and the primary outcome by adding an interaction term between the moderator and message arm to the linear regression model described above. We focused on these characteristics because they are predictive of sugary drink consumption1,35,36 and are relevant for understanding warning labels’ potential to affect sociodemographic disparities in diet-related diseases.31-34,63 Analyses estimated separate models for each moderator and calculated marginal effects (i.e., treatment effects) at each level of the moderator.

Analyses used a critical alpha of 0.05 and two-tailed tests. Analyses were conducted in Stata MP version 16 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX) in 2021.

Results

A total of 2,160 participants were included in primary analyses (1,088 in the control arm and 1,072 in the warning label arm). Participants’ average age was 30.2 years (SD 9.3). The sample was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, income, and other characteristics. Nearly half (49%) identified as Hispanic/Latino(a), 34% identified as non-Hispanic Black or African American, 9% identified as non-Hispanic White, and 7% identified as non-Hispanic multiracial or another race (Table 2). Half of participants reported a household income of less than $50,000 per year, and 43% reported participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the past 12 months. Most (89%) participants completed the survey in English. Compared to both the general San Francisco population and the US adult population, participants in the study sample were younger, more likely to be female, and more likely to identify as Hispanic/Latino(a), among other differences (Table 3 [online only]). Participant characteristics did not differ by treatment arm (all ps>0.28).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics, n=2,160 parents of children ages 6 months to 5 years participating in an online randomized experiment evaluating the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-24 years | 610 | 29% |

| 25-34 years | 922 | 44% |

| 35-44 years | 463 | 22% |

| 45-54 years | 70 | 3% |

| 55 years or older | 44 | 2% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 599 | 28% |

| Female | 1,489 | 69% |

| Transgender, nonbinary, or another gender identity | 68 | 3% |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school | 123 | 6% |

| High school diploma or GED | 434 | 20% |

| Some college | 411 | 19% |

| College degree or more | 1,187 | 55% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 199 | 9% |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 736 | 34% |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) | 1,064 | 49% |

| Non-Hispanic other race or multiracial | 154 | 7% |

| Language selected for survey administration | ||

| English | 1,929 | 89% |

| Spanish | 231 | 11% |

| Household size | ||

| 1 | 198 | 9% |

| 2 | 434 | 20% |

| 3 | 570 | 26% |

| 4 or more | 958 | 44% |

| Annual household income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 558 | 26% |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 525 | 24% |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 356 | 17% |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 283 | 13% |

| $100,000 or more | 434 | 20% |

| Participation in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in past 12 months | 923 | 43% |

| Participation in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in past 12 months | 826 | 38% |

Note. Characteristics are reported for the primary analytic sample and exclude n=4 participants with missing data on the primary outcome. Missing data on demographic characteristics ranged from 0.0% to 2.4%. Participant characteristics did not differ by message condition.

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristics of the study sample (n=2,160 US parents of children ages 6 months to 5 years participating in an online randomized experiment evaluating the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label) to San Francisco, CA and national estimates

| Characteristic | Study Sample |

San Francisco, CA Estimatea |

National Estimateb |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Agec | |||

| Under 18 years | - | 13% | - |

| 18-24 years | 29% | 7% | 12% |

| 25-34 years | 44% | 23% | 18% |

| 35-44 years | 22% | 16% | 16% |

| 45-54 years | 3% | 13% | 16% |

| 55 years or older | 2% | 27% | 38% |

| Genderd | |||

| Male | 28% | 51% | 49% |

| Female | 69% | 49% | 51% |

| Transgender, nonbinary, or another gender identity | 3% | - | - |

| Educational attainmente | |||

| Less than high school | 6% | 12% | 11% |

| High school diploma or GED | 20% | 12% | 28% |

| Some college | 19% | 17% | 22% |

| College degree or more | 55% | 59% | 39% |

| Race (any ethnicity) | |||

| White | 32% | 45% | 74% |

| Black or African American | 44% | 6% | 12% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4% | 0.4% | 1% |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3% | 35% | 6% |

| Other or Multiracial | 16% | 14% | 7% |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) ethnicity (any race) | 49% | 15% | 16% |

| Language selected for survey administration or spoken at homef | |||

| English | 89% | 58% | 67% |

| Spanish | 11% | 10% | 21% |

| Household sizeg | |||

| 1 | 9% | - | 0% |

| 2 | 20% | - | 5% |

| 3 | 26% | - | 26% |

| 4 or more | 44% | - | 69% |

| Annual household income | |||

| Less than $25,000 | 26% | 14% | 14% |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 24% | 10% | 19% |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 17% | 10% | 17% |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 13% | 8% | 14% |

| $100,000 or more | 20% | 58% | 37% |

| Participation in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in past 12 monthsh | 43% | - | 21% |

| Participation in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in past 12 monthsi | 38% | - | - |

San Francisco, CA estimates are from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates for San Francisco County, as reported in Social Explorer.81

National estimates are survey-weighted prevalence estimates from the 2019 ACS Public Use Microdata (ACS PUMS).82 To maximize comparability to the study sample, we derived national estimates of individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender) among adults ages 18-99 participating in the ACS, and derived national estimates for household characteristics (e.g., household size, income) for households with at least one child under the age of 6 participating in the ACS.

The study sample and the national estimates included adults ages 18 or older only, so no estimates are reported for the proportion under age 18.

The ACS reports sex in two categories (male, female), so no estimates are reported for the proportion of individuals who identify as transgender or another gender for San Francisco or the US.

San Francisco estimates are for individuals age 25 and older.

San Francisco estimates show the proportion of individuals age 5 and older who speak English only at home and the proportion who speak Spanish at home (regardless of English proficiency). National estimates show the proportion of households reporting English and Spanish as their primary household language. Proportions for San Francisco and national estimates do not sum to 100% because we do not report the proportion who use languages other than English and Spanish at home.

The proportion of households with only one member is 0% in the national data because we examined only households with at least one child (and thus all households had a least 2 members); in contrast, we did not require that participants in the study sample be living with their young children, so some participants in the study sample had a household size of one. County-level information on proportion of households with 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more members was not available, so no estimates are reported for San Francisco.

County-level information on SNAP participation was not available, so no estimates are reported for San Francisco.

The ACS does not include data on WIC participation, so no estimates are reported for San Francisco or the US.

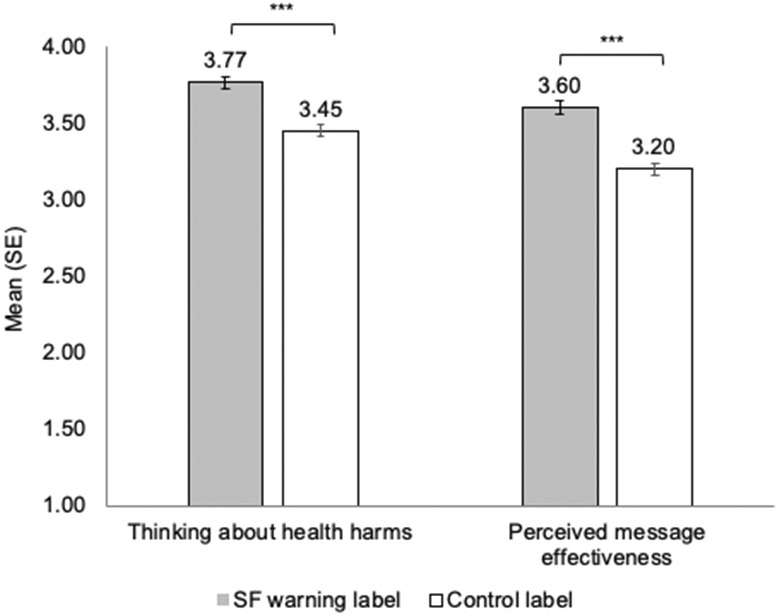

Among participants exposed to the control label, mean thinking about the health harms of sugary drinks was 3.45 (SE=0.04) (Figure 3). Among participants exposed to the San Francisco warning label, mean thinking about the health harms of sugary drinks was 3.77 (SE=0.04). Exposure to the warning labels elicited significantly more thinking about health harms than the control message (B=0.31, p<0.001). This difference was small in magnitude (d=0.24, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.33). Similarly, the San Francisco warning label was also perceived to be more effective than the control label (B=0.40, p<0.001). This effect was also relatively small in size (d=0.31, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.39).

Figure 3. Impact of San Francisco warning on thinking about health harms and perceived message effectiveness in an online randomized experiment of US adults.

***p<0.001

In moderation analyses, the effect of the San Francisco warning label on thinking about health harms did not differ by any of the six participant characteristics examined (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, or survey language; p>0.12 for all interactions; Table 4 [online only]).

Table 4.

Interaction of message arm and participant characteristics on thinking about harms in an online randomized experiment of the 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label, n=2,160 parents of children ages 6 months to 5 years

| Participant Characteristics | Impact of San Francisco warninga |

p for interactionb |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B | (95% CI) | ||

| Age | |||

| 18-34 years | 0.29 | (0.16, 0.42) | 0.60 |

| 35 years or older | 0.35 | (0.1, 0.56) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0.21 | (0.003, 0.41) | 0.44 |

| Female | 0.37 | (0.2, 0.50) | |

| Transgender, nonbinary, or another gender identity | 0.24 | (−0.3, 0.86) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.37 | (0.0, 0.73) | 0.54 |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 0.26 | (0.0, 0.44) | |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) | 0.37 | (0.2, 0.52) | |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiracial | 0.07 | (−0.3, 0.48) | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Some college or less | 0.27 | (0.11, 0.43) | 0.44 |

| Two-year college degree or more | 0.36 | (0.2, 0.51) | |

| Household income | |||

| Less than $50,000/year | 0.27 | (0.1, 0.43) | 0.53 |

| $50,000/year or more | 0.34 | (0.1, 0.50) | |

| Language selected for survey administration | |||

| Spanish | 0.06 | (−0.27, 0.40) | 0.12 |

| English | 0.34 | (0.2, 0.46) | |

Difference in predicted mean level of thinking about health harms between San Francisco warning label and control arms at each level of the moderator

p for interaction is for Wald tests of joint significance of the coefficients on all interaction terms

Discussion

Sugary drink warning labels are an increasingly popular policy tool for informing consumers and encouraging healthier beverage choices. Our study, the first to examine the warning message in San Francisco’s 2020 ordinance, found that this warning label elicited more thinking about harms than a control message. The 2020 San Francisco warning label was also perceived to be more effective at discouraging sugary drink consumption than the control label. Prior studies of sugary drink and tobacco warning labels have demonstrated that both thinking about health harms46,47 and perceived message effectiveness48,50,51 are predictive of actual behavior change. Our results thus provide important early evidence that the 2020 San Francisco warning label holds promise for encouraging healthier beverage choices. Our study also suggests that the San Francisco warning label could increase informed choice by helping consumers keep sugary drinks’ health harms at top of mind when making purchase decisions.61 These findings speak directly to evaluations of the ordinance in potential First Amendment challenges, as the results suggest that the San Francisco warning label would advance government interests of informing consumers and helping them make healthier choices.

The impact of the 2020 San Francisco warning label on thinking about health harms was statistically significant but relatively small (d=0.24), smaller than the effect found in a meta-analysis of experimental studies (d=0.65),21 but similar to the effect observed in an experiment with Australian young adults (d=0.21 for text-only warnings vs. control).24 The 2020 San Francisco warning label’s effect on perceived message effectiveness was also relatively small (d=0.31), in line with the average effect of a nutrient warning (i.e., “WARNING: High in added sugar,” d=0.27) in an experiment with US adults, but smaller than the average effect of a health warning in that study (d=0.53).28 The differences in effect sizes observed across studies could be explained by differences in experimental design, amount of exposure to the warning, measurement, study setting, or label characteristics. Although the San Francisco warning label exerted small effects in this study, small effects can yield large health benefits when policies are implemented at the population level.27,64 Moreover, prior research suggests that even modest changes in thinking about harms and perceived message effectiveness may be accompanied by meaningful changes in behavioral intentions and actual behavior.24,47,65 For example, Billich and colleagues found that text and graphic sugary drink warning labels had small effects on thinking about harms (ds=0.21 and 0.25 for text and graphic warnings, respectively) and larger effects on participants’ likelihood of choosing a sugary drink in a choice task (ds= −0.38 and −0.84, respectively).24

The impact of the San Francisco warning label did not differ across demographic groups, including for adults younger versus older than age 35, adults with different gender identities, adults with lower versus higher educational attainment and income, adults with different racial/ethnic identities, and English versus Spanish speakers. These results suggest that the San Francisco warning label is unlikely to exacerbate disparities in sugary drink consumption by these demographic characteristics, consistent with prior studies that have found limited differences in sugary drink22,23,28,66-68 and tobacco69,70 warning labels’ impacts across demographic groups. Further, one simulation modeling study found that if warning labels exert similar impacts across demographic groups, warning label policies could reduce sociodemographic disparities in obesity prevalence.27

The 2020 San Francisco warning label ordinance requires that warning labels appear in the same language as the sugary drink advertisement on which they are displayed.10 To our knowledge, ours is the first US study to examine reactions to warning labels that have been translated to a language other than English. Results of our study did not indicate differences in consumers’ responses to warning labels by language; however, care should be taken to ensure that warning labels benefit consumers regardless of their preferred language. Emerging evidence indicates that adding icons or pictures to warnings written in English enhances their efficacy, particularly among adults with low English proficiency.71 Future studies should examine whether icons and pictures similarly boost the effectiveness of warnings written in other languages, particularly for non-English speakers.

Strengths of this study include the large, diverse sample of US adults, experimental design, assessment of outcomes predictive of behavior change, and examination of warning labels’ effects across demographic groups. One limitation of this study was the use of a convenience sample that differed in several sociodemographic characteristics compared to the San Francisco, CA population and to US adults overall. In particular, this study oversampled Hispanic/Latino(a) and non-Hispanic Black adults to enable examination of the warnings’ impacts by race/ethnicity and to ensure adequate numbers of people of color, who are often underrepresented in research studies.72 Prior studies indicate that online convenience samples provide similar experimental results as probability samples,56,73,74 and this study did not find differences in warnings’ impacts by race/ethnicity, suggesting that this study’s results may generalize to other populations. Still, additional studies in other populations (e.g., adolescents, adults who are not parents, individuals with high sugary drink consumption) are warranted. Another limitation is that this study focused on parents’ discouragement from consuming sugary drinks. Future studies will be needed to determine whether the 2020 San Francisco warning label also discourages parents from serving sugary drinks to their children, as has been documented for the 2015 version of the San Francisco warning message.22 Additionally, outcomes were self-reported, so we cannot rule that results were driven by demand characteristics, including social desirability. To reduce this possibility, recruitment materials and survey questions did not reveal the study’s purpose and participants provided information anonymously via an online survey.75,76 Moreover, other online experiments have found no influence of other types of prominent nutrition labels (e.g., calorie labels,22-24 traffic light labels,77 health star rating labels78), suggesting that demand characteristics and social desirability do not always exert strong pressure on participants to respond in a certain way in these settings. Finally, while thinking about harms and perceived message effectiveness are predictive of behavior change, we did not assess behavioral outcome. Additional research is needed to evaluate the 2020 San Francisco warning label’s impact on parents’ actual sugary drink purchases, both for their personal consumption and to serve to their children.

Conclusions

This randomized experiment with a large sample of US parents suggests that the warning message in San Francisco’s 2020 ordinance holds promise for informing consumers and discouraging sugary drink consumption across diverse segments of the population. Future studies will clarify impacts in real-world settings.

Supplementary Material

Research Snapshot.

Research Questions:

Does the revised 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label inform consumers about the health harms of sugary drinks and discourage sugary drink consumption? Do consumers’ reactions to the warning label differ across population groups relevant for warnings’ impacts on health equity?

Key Findings:

In a randomized experiment, the revised 2020 San Francisco sugary drink warning label led consumers to think more about the harms of sugary drinks compared to the control message (p<0.001). The warning label also elicited higher perceived effectiveness for discouraging sugary drink consumption (p<0.001). Warning label impacts did not differ by age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, or language preference.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Hannah Rayala for assistance with graphic design and have received permission to acknowledge her work.

Financial Disclosure:

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by a grant from FIRST 5 Santa Clara County (no number). MGH was supported by K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note to Editor: Hannah Rayala has given written permission to be named in the acknowledgments.

References

- 1.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003-2014. Obesity. 2018;26(2):432–441. doi: 10.1002/oby.22056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among U.S. Adults, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among U.S. Youth, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ. 2015;351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu F Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):606–619. doi: 10.1111/obr.12040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356–1364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik V, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernabé E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: A 4-year prospective study. J Dent. 2014;42(8):952–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiener S, Mar G. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning Ordinance.; 2015. Accessed December 15, 2020. http://www.sfbos.org/ftp/uploadedfiles/bdsupvrs/ordinances16/o0004-16.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.City and County of San Francisco. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning Ordinance. Vol Article 42.; 2020. Accessed November 21, 2020. https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/san_francisco/latest/sf_health/0-0-0-58530#JD_4203 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. Can the government require health warnings on sugar-sweetened beverage advertisements? JAMA. 2018;319(3):227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. Sugar-sweetened beverage warning policies in the broader legal context: Health and safety warning laws and the first amendment. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(6):783–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera G Requires Sugar-Sweetened Beverages to Be Labeled with a Safety Warning.; 2020. Accessed January 28, 2020. https://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=S00473&term=2019&Summary=Y&Actions=Y&Text=Y&Committee%26nbspVotes=Y&Floor%26nbspVotes=Y#S00473 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi B, LoPresti M, Morikawa D. Relating to Health.; 2018. Accessed January 28, 2020. https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/session2018/bills/HB1209_.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens T, Carr S. An Act Related to Health and Safety Warnings on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages.; 2017. https://legislature.vermont.gov/bill/status/2016/H.89 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monning B Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Safety Warnings.; 2019. Accessed February 27, 2019. http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB347 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson J Concerning Mitigation of the Adverse Impacts of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages.; 2016. http://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=2798&Year=2016 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall MG, Grummon AH, Maynard OM, Kameny MR, Jenson D, Popkin BM. Causal language in health warning labels and US adults’ perception: A randomized experiment. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1429–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carl A, Taillie L, Grummon AH, et al. Awareness of and reactions to the health harms of sugary drinks: An online study of U.S. parents. Appetite. 2021;164(105234). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zauderer v Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio.(Supreme Court of the United States; 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grummon AH, Hall MG. Sugary drink warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. PLOS Medicine. 2020;17(5):e1003120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage health warning labels on parents’ choices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153185. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VanEpps EM, Roberto CA. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage warnings: A randomized trial of adolescents’ choices and beliefs. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billich N, Blake MR, Backholer K, Cobcroft M, Li V, Peeters A. The effect of sugar-sweetened beverage front-of-pack labels on drink selection, health knowledge and awareness: An online randomised controlled trial. Appetite. 2018;128:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollard T, Maubach N, Walker N, Mhurchu CN. Effects of plain packaging, warning labels, and taxes on young people’s predicted sugar-sweetened beverage preferences: An experimental study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayward L, Vartanian L. Potential unintended consequences of graphic warning labels on sugary drinks: Do they promote obesity stigma? Obes Sci Pract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grummon AH, Smith NR, Golden SD, Frerichs L, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. Health warnings on sugar-sweetened beverages: Simulation of impacts on diet and obesity among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):765–774. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grummon AH, Hall MG, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. How should sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings be designed? A randomized experiment. Prev Med. 2019;121:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temple JL, Ziegler AM, Epstein LH. Influence of Price and Labeling on Energy Drink Purchasing in an Experimental Convenience Store. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(1):54–59.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall MG, Lazard AJ, Grummon AH, Mendel JR, Taillie LS. The impact of front-of-package claims, fruit images, and health warnings on consumers’ perceptions of sugar-sweetened fruit drinks: Three randomized experiments. Prev Med. 2020;132:105998. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flegal K, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll M, Fryar C, Ogden C. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Heart Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crall JJ, Vujicic M. Children’s oral health: progress, policy development, and priorities for continued improvement: Study examines improvements in American children’s oral health and oral health care that stem from major federal and state initiatives, and persistent disparities. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1762–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vercammen KA, Moran AJ, Soto MJ, Kennedy-Shaffer L, Bleich SN. Decreasing trends in heavy sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in theUnited States, 2003 to 2016. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(12):1974–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Healthy Eating Research. 2020 Call for Proposals. Published August 2020. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https%3A%2F%2Fhealthyeatingresearch.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F08%2FHER-SSB_Final_CFP.pdf

- 38.Healthy Eating Research. A National Research Agenda to Reduce Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Increase Safe Water Access and Consumption among Zero- to Five-Year-Olds. Healthy Eating Research; 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019. https://healthyeatingresearch.org/research/national-research-agenda-zero-to-five-beverage-consumption/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieger J, Bleich SN, Scarmo S, Ng SW. Sugar-sweetened beverage reduction policies: Progress and promise. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;42:439–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-103005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duffy EW, Lott MM, Johnson EJ, Story MT. Developing a national research agenda to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and increase safe water access and consumption among 0-to 5-year-olds: A mixed methods approach. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(1):22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J Law Med Ethics. 2007;35(1):22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicklaus S, Remy E. Early origins of overeating: tracking between early food habits and later eating patterns. Curr Obes Rep. 2013;2(2):179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lioret S, McNaughton SA, Spence AC, Crawford D, Campbell KJ. Tracking of dietary intakes in early childhood: The Melbourne InFANT Program. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(3):275–281. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luque V, Escribano J, Closa-Monasterolo R, et al. Unhealthy dietary patterns established in infancy track to mid-childhood: The EU Childhood Obesity Project. J Nutr. 2018;148(5):752–759. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brewer N, Parada H Jr, Hall M, Boynton M, Noar S, Ribisl K. Understanding why pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase quit attempts. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(3):232–243. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grummon AH, Brewer NT. Health warnings and beverage purchase behavior: Mediators of impact. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(9):691–702. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bigsby E, Cappella JN, Seitz HH. Efficiently and effectively evaluating public service announcements: Additional evidence for the utility of perceived effectiveness. Commun Monogr. 2013;80(1):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Lazard AJ, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Message perceptions and effects perceptions as proxies for behavioral impact in the context of anti-smoking messages. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101434. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noar SM, Barker J, Bell T, Yzer M. Does perceived message effectiveness predict the actual effectiveness of tobacco education messages? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2018;35(2):148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noar SM, Rohde JA, Prentice-Dunn H, Kresovich A, Hall MG, Brewer NT. Evaluating the actual and perceived effectiveness of E-cigarette prevention advertisements among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2020;109:106473. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rohde JA, Noar SM, Prentice-Dunn H, Kresovich A, Hall MG. Comparison of message and effects perceptions for The Real Cost e-cigarette prevention ads. Health Commun. Published online 2020:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dillard JP, Shen L, Vail RG. Does perceived message effectiveness cause persuasion or vice versa? 17 consistent answers. Hum Commun Res. 2007;33(4):467–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00308.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvaro EM, Crano WD, Siegel JT, Hohman Z, Johnson I, Nakawaki B. Adolescents’ attitudes toward antimarijuana ads, usage intentions, and actual marijuana usage. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(4):1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dillard JP, Li SS, Cannava K. Talking about sugar-sweetened beverages: Causes, processes, and consequences of campaign-induced interpersonal communication. Health Commun. Published online October 30, 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeong M, Zhang D, Morgan J, et al. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann Behav Med. 2018;53(5):476–485. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sokol RL, Grummon AH. COVID-19 and parent intention to vaccinate their children against influenza. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e2020022871. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-022871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Cameron R, Brown KS. Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control. 2003;12(4):391–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fathelrahman AI, Omar M, Awang R, Cummings KM, Borland R, Samin ASBM. Impact of the new Malaysian cigarette pack warnings on smokers’ awareness of health risks and interest in quitting smoking. Int J Envir Res Public Health. 2010;7(11):4089–4099. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7114089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Boynton MH, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. UNC Perceived Message Effectiveness: Validation of a brief scale. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(8):732–742. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grummon AH, Hall MG, Block JP, et al. Ethical Considerations for Food and Beverage Warnings. Physiology & Behavior. 2020;222:112930. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Disparities. Healthy People. Published October 8, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities?_ga=2.94465759.2125600361.1616256199-1426856900.1616256199 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee BY, Ferguson MC, Hertenstein DL, et al. Simulating the Impact of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning Labels in Three Cities. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donnelly G, Zatz L, Svirsky D, John L. The effect of graphic warnings on sugary-drink purchasing. Psych Science. 2018;29(8):1321–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grummon AH, Taillie LS, Golden SD, Hall MG, Ranney LM, Brewer NT. Sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings and purchases: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(5):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taillie LS, Hall MG, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Acton RB, Kirkpatrick SI, Hammond D. Exploring the main and moderating effects of individual-level characteristics on consumer responses to sugar taxes and front-of-pack nutrition labels in an experimental marketplace. Can J Public Health. 2021;112(4):647–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cantrell J, Vallone DM, Thrasher JF, et al. Impact of tobacco-related health warning labels across socioeconomic, race and ethnic groups: Results from a randomized web-based experiment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e52206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hall M, Lazard A, Grummon AH, et al. Designing warnings for sugary drinks: A randomized experiment with Latino and non-Latino parents. Prev Med. 2021;148:106562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, et al. Diversity in Clinical and Biomedical Research: A Promise Yet to Be Fulfilled. PLOS Medicine. 2015;12(12):e1001918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Anal. 2012;20(3):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weinberg JD, Freese J, McElhattan D. Comparing data characteristics and results of an online factorial survey between a population-based and a crowdsource-recruited sample. Sociol Sci. 2014;1:292–310. doi: 10.15195/v1.a19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grimm P Social desirability bias. In: Kamakura W, ed. Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dodou D, de Winter JC. Social desirability is the same in offline, online, and paper surveys: A meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;36:487–495. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Findling MTG, Werth PM, Musicus AA, et al. Comparing five front-of-pack nutrition labels’ influence on consumers’ perceptions and purchase intentions. Prev Med. 2018;106:114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Egnell M, Ducrot P, Touvier M, et al. Objective understanding of Nutri-Score Front-Of-Package nutrition label according to individual characteristics of subjects: Comparisons with other format labels. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food Security Questionnaire. Published 2019. https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwwwn.cdc.gov%2Fnchs%2Fdata%2Fnhanes%2F2019-2020%2Fquestionnaires%2FFSQ_Family_K.pdf

- 81.Social Explorer. Social Explorer Tables: ACS 2019 (1-Year Estimates) (SE). ACS 2019 (1-Year Estimates). Published 2019. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.socialexplorer.com/tables/ACS2019/R12794971

- 82.United States Census Bureau. Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS). American Community Survey (ACS). Published February 23, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.