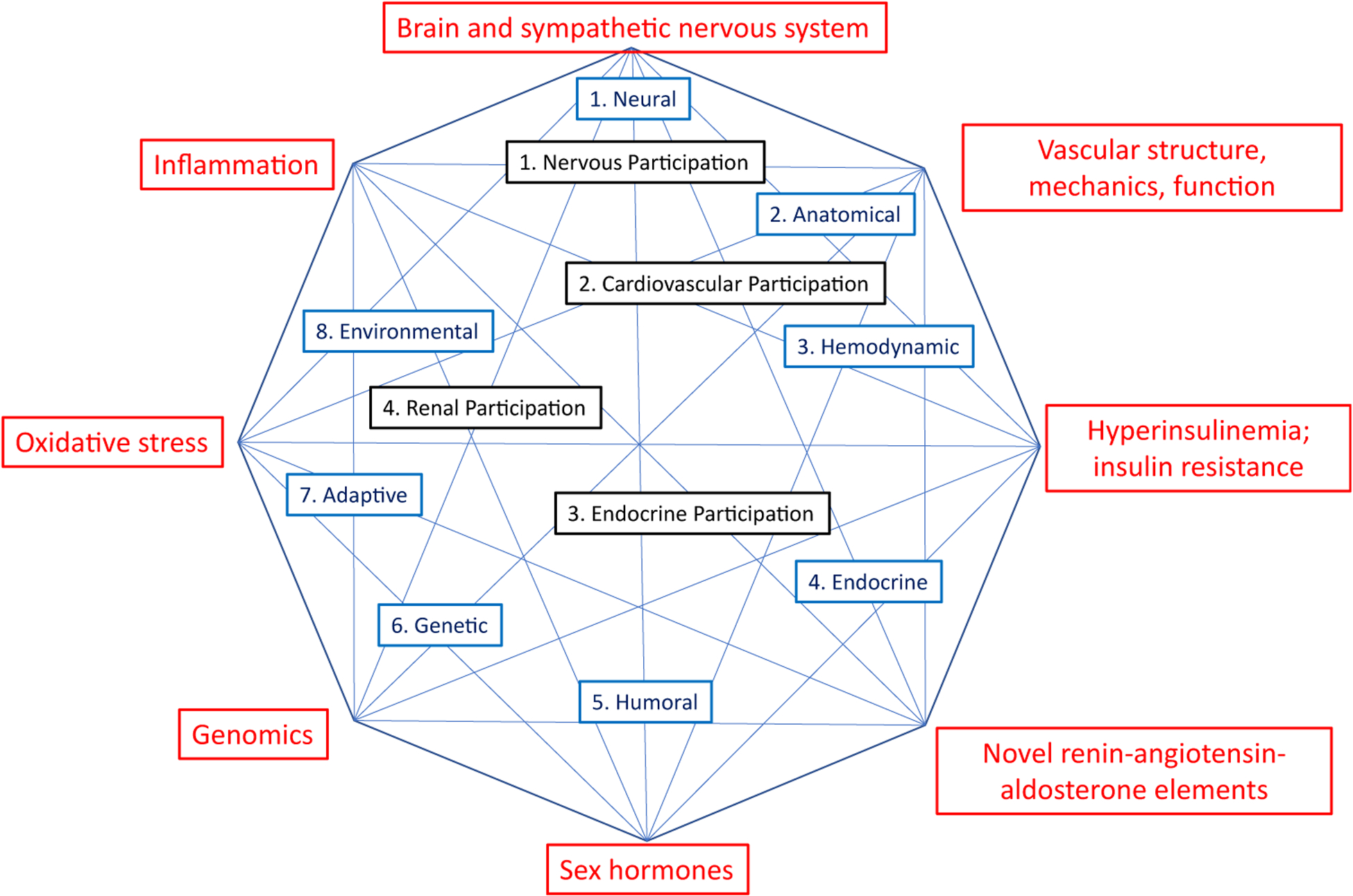

Despite extensive research, the pathogenesis of hypertension is still elusive. Although the origin is known in less than 5% of patients, the majority of patients have primary hypertension when identifiable cause(s) remain unknown. However, what is clear is that the pathophysiology of primary hypertension is multifactorial, multifaceted, and highly complex and includes several interacting physiological systems. This was highlighted more than 70 years ago,1 when Irving H. Page suggested in his “mosaic theory” that hypertension is a disease of “dysregulation” that involves multiple interacting elements (black elements, Figure 1). This was subsequently conceived as an octagon with regulators on each point, connected by arrows. This paradigm was refined 32 years later2 to include genetic, environmental, anatomic, adaptive, neural, endocrine, humoral, and hemodynamic factors as the pivotal components of the octagon (blue elements, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different aspects of Irving Page’s mosaic theory of hypertension revisited in this compendium. The 4 black elements are the principal components mentioned in the original 1949 paper.1 The 8 blue components are enumerated in the subsequent, more extensive revisiting of the theme in 1982.2 The 8 red components are themes dealt with by review papers in the current issue of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Since then, there has been enormous progress in unravelling molecular, cellular, and organ-system mechanisms that underlie hypertension. Moreover, it has become evident that the development of primary hypertension, from early to established and advanced stages, involves a range of cardiovascular and renal mechanisms ranging from the dysregulation of fetal/neonatal renal programming, the elevation in cardiac output that is characteristic of the elevations in blood pressure in adolescents and young adults, to the increased peripheral resistance that is the hallmark of established and advanced hypertension.

With advancements in hypertension research, it has become necessary to reconsider the comprehensiveness of the hypertension mosaic. This was highlighted in 2013 in a paper entitled The Mosaic Theory Revisited.3 In the current issue of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, we further develop the concept with a collection of reviews focusing on some new aspects (red elements, Figure 1) related to genomics;4 sex hormones;5 the sympathetic nervous system;6 the brain aminopeptidase system;7 hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance;8 oxidative stress;9 inflammation;10 the angiotensin AT2 receptor;11 and structure, mechanics, and function of the vasculature.12

This compendium of reviews, together with the 2 papers on hypertension guidelines,13,14 provides state-of-the art knowledge that will keep the reader abreast of the complexities associated with hypertension.

Funding Sources

E.L.S. is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research First Pilot Foundation Grant 143348 and a Canada Research Chair (CRC); D.G.H. is funded by the National Institutes of Health Grants R35HL140016 and Program Project Grant P01HL129941; and R.M.T. is funded by the British Heart Foundation (CH/12/4/29762, RE/18/6/34217).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Page IH. Pathogenesis of arterial hypertension. J Am Med Assoc 1949;140:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page IH. The mosaic theory 32 years later. Hypertension 1982;4:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison DG. The mosaic theory revisited: common molecular mechanisms coordinating diverse organ and cellular events in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens 2013;7:68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lip S, Padmanabhan S. Genomics of blood pressure and hypertension: extending the mosaic theory towards stratification. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman RD. Sex-specific determinants of coronary artery disease and atherosclerotic risk factors: estrogen and beyond. Can J Cardiol 2020;36: 706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLalio LJ, Sved AF, Stocker SD. Sympathetic nervous system contributions to hypertension: updates and therapeutic relevance. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:712–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marc Y, Boitard SE, Balavoine F, Azizi M, Llorens-Cortes C. Targeting brain aminopeptidase A: a new strategy for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Li X, Wang Z, Mouton AJ, Hall JE. Role of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in hypertension: metabolic syndrome revisited. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:671–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touyz RM, Rios FJ, Alves-Lopes R, Neves KB, Camargo LL, Montezano AC. Oxidative stress: a unifying paradigm in hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:659–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao L, Harrison DG. Inflammation in hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:635–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assersen K, Sumners C, Steckelings UM. The renin-angiotensin system in hypertension, a constantly renewing classic: focus on the angiotensin AT2-receptor. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiffrin EL. How structure, mechanics and function of the vasculature contribute to blood pressure elevation in hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiremath S, Sapir-Pichhadze R, Nakhla M, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 evidence review and guidelines for the management of resistant hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabi DM, McBrien K, Sapir-Pichhadze R, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, risk assessment and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol 2020;36: 596–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]