Abstract

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently mandated a warning statement on packaged fruit juices not treated to reduce target pathogen populations by 5 log10 units. This study describes combinations of intervention treatments that reduced concentrations of mixtures of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (strains ATCC 43895, C7927, and USDA-FSIS-380-94) or Salmonella typhimurium DT104 (DT104b, U302, and DT104) by 5 log10 units in apple cider with a pH of 3.3, 3.7, and 4.1. Treatments used were short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C and/or freeze-thawing (48 h at −20°C; 4 h at 4°C) of cider with or without added organic acids (0.1% lactic acid, sorbic acid [SA], or propionic acid). Treatments more severe than those for S. typhimurium DT104 were always required to destroy E. coli O157:H7. In pH 3.3 apple cider, a 5-log10-unit reduction in E. coli O157:H7 cell numbers was achieved by freeze-thawing or 6-h 35°C treatments. In pH 3.7 cider the 5-log10-unit reduction followed freeze-thawing combined with either 6 h at 4°C, 2 h at 25°C, or 1 h at 35°C or 6 h at 35°C alone. A 5-log10-unit reduction occurred in pH 4.1 cider after the following treatments: 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing, SA plus 12 h at 25°C plus freeze-thawing, SA plus 6 h at 35°C, and SA plus 4 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing. Yeast and mold counts did not increase significantly (P < 0.05) during the 6-h storage at 35°C. Cider with no added organic acids treated with either 6 h at 35°C, freeze-thawing or their combination was always preferred by consumers over pasteurized cider (P < 0.05). The simple, inexpensive intervention treatments described in the present work could produce safe apple cider without pasteurization and would not require the FDA-mandated warning statement.

Apple cider (turbid nonfermented apple juice containing pulp) is a traditional beverage produced and consumed in the fall. Small cider mills commonly sell unpasteurized apple cider. The pH of apple juice is typically between 3.3 and 4.1 (mean ± standard deviation for a 3-year study [21]), and in the past apple beverages were not regarded as potentially hazardous. However, during the past 2 decades fresh apple juice or cider has become the most frequent acidic food vehicle transmitting enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7, an important human pathogen (3, 5, 6). Outbreaks of salmonellosis in 1974 (4) and cryptosporidiosis in 1993 and 1996 (6, 23) also involved apple cider. According to Besser et al. (3) one possible source of E. coli O157:H7 in apple beverages may be “drop” apples contaminated via animal feces on the ground. Animals such as cattle, deer, and birds have recently been reported as possible vectors of E. coli O157:H7 (17, 37, 40).

Today, enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 has become a major concern in foods for several reasons: (i) severe consequences of infection such as hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome which preponderantly afflict small children, the elderly, and immunocompromised people (12, 26); (ii) its low infectious dose (11, 16); and (iii) its high acid tolerance, which allows lengthy survival in low-pH foods and beverages (2, 10, 14, 20, 24, 35). The survival of E. coli O157:H7 in fresh unpasteurized cider has been shown to well exceed the typical 1- to 2-week refrigerated shelf life (24, 28, 39). The ability of E. coli O157:H7 to survive well in low-pH synthetic gastric fluid has also been reported (1, 29, 36), suggesting that survival while passing through the human stomach may be an important determinant of infectivity.

Considering the frequency of outbreaks associated with contaminated apple ciders and the severity of the illness caused by such cider, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently concluded that there is a risk of serious illness from consuming juice products that have not been processed in a manner designed to destroy target pathogens, including E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella spp. Thus, in 1998 the FDA published regulations requiring a warning statement on packaged juices not processed in a manner to produce at least a 5-log10-unit reduction in the pertinent target microorganism for a period of at least as long as the shelf life of the product when stored under normal and moderate abuse conditions. Such apple cider should bear the following statement: “WARNING: This product has not been pasteurized and, therefore, may contain harmful bacteria which can cause serious illness in children, the elderly, and persons with weakened immune systems” (9). Although there is considerable consumer and food industry pressure to require pasteurization for all apple cider sold, the current warning label regulations allow small cider producers, who are unable to afford a pasteurizer, to continue producing cider for sale.

In today’s cider industry the dominant preservation methods are still traditional ones such as heat treatment, organic acid additives, and cold storage. Pasteurization remains the most effective method of eliminating pathogens from cider. One currently recommended pasteurization treatment for apple cider is heating to 71.1°C for 6 s (22). Commonly used food additives in cider, such as potassium sorbate and sodium benzoate, have been shown to have a minimal lethal effect on E. coli O157:H7. The more potent additive, sodium benzoate (0.1%), has been shown to cause a 5-log10-unit reduction in E. coli O157:H7 numbers during 2 to 10 days at 8°C (39). However, concentrations of benzoate higher than 0.0125% reportedly impart noticeable tastes (31). Refrigeration is an essential part of extending the shelf life of apple cider; however, if E. coli O157:H7 is present in cider, refrigeration will enhance its survival (24, 36, 39). A relatively simple way to kill E. coli O157:H7 in apple cider is freezing and thawing. Freezing can extend the shelf life of cider and also, as reported by Sage and Ingham (30), caused a 0.63- to 3.43-log10-CFU/ml reduction in numbers of E. coli O157:H7 organisms.

The combination of inactivation treatments is known to have greater lethality for cells than one treatment alone. In apple juice with a pH of 3.4, we (15) demonstrated that E. coli O157:H7 stored at 21°C for up to 6 h became significantly more heat sensitive than cells heated shortly after exposure to the acidic juice. Short-term storage of juice after pressing would therefore decrease the intensity of heat treatment required for eliminating E. coli O157:H7 and decrease thermal effects on organoleptic characteristics. Short-term storage of cells at 21°C may also increase the sensitivity of cells to organic acids (36). The present study examined the separate and combined effects of short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; freeze-thawing; and organic acid addition (lactic, sorbic, or propionic acid) on survival of E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella typhimurium DT104 in apple cider. Particular emphasis was placed on treatments or combinations resulting in a 5-log10-unit reduction in cell concentrations. All tests were run using apple cider with a pH of 3.3, 3.7, and 4.1. The microbiological quality of the cider was also monitored by enumerating yeasts and molds during the short-term storage treatment most conducive to microbial growth. Finally, the most-effective inactivation treatments at each pH were evaluated by a consumer taste panel for desirability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three strain cocktails of E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 43895, C7927, and USDA-FSIS-380-94) and S. typhimurium (JBL 3266 [phage type DT104b], JBL 3267 [phage type U302], and JBL 3270 [phage type DT104]) were used in this study. E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 43895, which reportedly survives well in apple cider (24, 36), is an isolate from raw hamburger meat and produces Shiga-like toxins I and II. The C7927 strain was originally isolated from a patient who had drunk contaminated apple cider. The USDA-FSIS-380-94 strain is an isolate from salami linked to an outbreak. All E. coli O157:H7 strains are commonly used for challenge studies. S. typhimurium definitive type DT104 (JBL 3270) is a patient isolate and multiple-antibiotic resistance phage type that has been linked to food-borne illness (7). Strains JBL 3266 and 3267 are also patient isolates. Cultures were maintained as frozen (−20°C) stocks in Trypticase soy broth (for E. coli O157:H7; BBL Becton Dickson and Company, Cockeysville, Md.) or brain heart infusion broth (BHI) (for S. typhimurium DT104; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 10% glycerol (wt/vol; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and were passed twice at 35°C in Trypticase soy broth (for E. coli O157:H7) or BHI (for S. typhimurium DT104) before use.

Apple cider.

Unpasteurized, preservative-free apple cider was purchased directly from a Wisconsin apple cider manufacturer. The pH of the cider was 3.3 and the °Brix, measured with a temperature-compensated hand-held refractometer (Leica Inc., Buffalo, N.Y.), was 13.3. For inactivation and survival studies, the following organic acids were added to cider: 0.1% (vol/vol) lactic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.), 0.1% (wt/vol) sorbic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.), and 0.1% (wt/vol) propionic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.). To the cider, 3.0 N NaOH was then added to adjust the pH to 3.3, 3.7, or 4.1 to represent the typical pH range of apple cider (21). Cider was then dispensed in Falcon (BBL Becton Dickinson and Company) 50-ml screw-cap tubes and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min to eliminate all background microflora. Sterilized cider was stored frozen (−20°C) until used.

Inactivation treatments of E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT104 in apple cider by storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; freezing and thawing; and organic acid addition.

A three-strain mixture of E. coli O157:H7 or S. typhimurium DT104 was prepared by combining three stationary-phase cultures (18 h; 35°C), each of which was centrifuged (8,000 × g; 10 min) and resuspended in the same volume of 0.85% (wt/vol) saline, yielding a final cell concentration of ca. 9.0 log10 CFU/ml.

In apple cider with three different pHs (3.3, 3.7, and 4.1), three different treatments to inactivate E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT104 were studied. The treatments were (i) 0 to 12 h of storage at 4°C, 0 to 12 h of storage at 25°C, or 0 to 6 h of storage at 35; and/or (ii) freezing at −20°C for 48 h followed by thawing at 4°C for 4 h; and/or (iii) addition of organic acids commonly used as food and beverage preservatives (0.1% lactic acid, 0.1% sorbic acid, or 0.1% propionic acid, prepared as described above). To test the efficacy of each treatment alone and combinations of two or three treatments, the experiments were designed as follows. Apple cider samples (50 ml) with or without added organic acids were tempered to 4, 25, and 35°C; inoculated at ca. 7.0 log10 CFU/ml; and placed at 4 and 25°C for 12 h and at 35°C for 6 h. During storage a 5-ml sample was taken from 4 and 25°C ciders at 0, 2, 6, and 12 h and from 35°C ciders at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h. Of each sample, 4 ml of cider was placed in a −20°C freezer for 48 h and the remaining 1.0 ml was immediately analyzed to determine the viable cell concentration. After 48 h of freezing, the 4.0-ml samples were thawed at 4°C for 4 h and analyzed for viable cell concentration. Cell concentrations were determined in nonselective tryptic soy agar (for E. coli O157:H7; BBL Becton Dickinson and Company) or nonselective BHI agar (for S. typhimurium DT104; Difco Laboratories) on duplicate pour plates. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 days for E. coli O157:H7 and for 3 days for S. typhimurium DT104. Results were recorded as log10 CFU per milliliter of apple cider. The detection limit was 0.7 log10 CFU/ml. For averaging the results of three trials, a value of 0.7 log10 CFU/ml was assigned when no cells were recorded. Triplicate trials, each on a different day, were done for each experiment.

Yeast and mold growth during 6-h storage at 35°C.

The possible increase of yeast and mold concentrations in cider (pH 3.3) during the 6-h storage at 35°C was studied. Nonautoclaved, fresh cider with 0% additives, 0.1% lactic acid, or 0.1% sorbic acid was incubated at 35°C for 6 h. Samples were taken at 0 and 6 h of storage, and yeasts and molds were enumerated on Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol agar prepared according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Oxoid, Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 days, and results were recorded as log10 CFU per milliliter of cider. Student’s t test (18) was used to test for significant (P < 0.05) differences in mean (n = 3) cell concentrations between 0- and 6-h samples for each type of cider.

Consumer preference evaluation of apple cider.

Consumer preference evaluation of apple cider was performed in the Sensory Analysis Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. The objective of the evaluation was to compare pasteurized apple cider (15 s; 72°C) to cider subjected to two different treatments which effected a 5-log10 reduction in concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 at each pH tested (pH 3.3, 3.7, and 4.1). The first panel evaluated treatments effective in pH 3.3 cider: 6 h at 35°C and freeze-thawing. Treatments which were effective for pH 3.7 cider were evaluated in the second panel: 0.1% potassium sorbate (food grade; Eastman Chemical Company, Kingsport, Tenn.) plus 6 h at 35°C and 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing. The third panel evaluated treatments effective in pH 4.1 cider: 0.1% potassium sorbate plus 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing and 0.1% lactic acid (food grade; Archer Daniels Midland, Decatur, Ill.) plus 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing. Samples of approximately 30 ml were presented in 45-ml cups, coded with random three-digit numbers, at 4°C. A varied order of presentation was used to prevent positional bias. At least 175 participants evaluated each sample. The consumer preference ballot contained a structured 7-point hedonic scale, in which 7 was assigned to the category “like very much” and 1 was assigned to “dislike very much.” The data from each panel session were subjected to analysis of variance by the least significant difference test on SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.) to test for significant (5%-level) differences between any pair of treatment mean scores.

RESULTS

Efficacy of short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; freeze-thawing, and/or organic acid addition in reducing the numbers of E. coli O157:H7 organisms by 5 log10 units in apple cider.

Survival of E. coli O157:H7 after short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; after freezing (−20°C for 48 h) and thawing (4 h at 4°C); and/or in the presence of organic acids (0.1% lactic acid, 0.1% sorbic acid, and 0.1% propionic acid) was monitored in (i) pH 3.3 apple cider, (ii) pH 3.7 apple cider, and (iii) pH 4.1 apple cider. The initial concentration of cells in cider was ca. 7 log10 CFU/ml.

(i) E. coli O157:H7 in pH 3.3 apple cider.

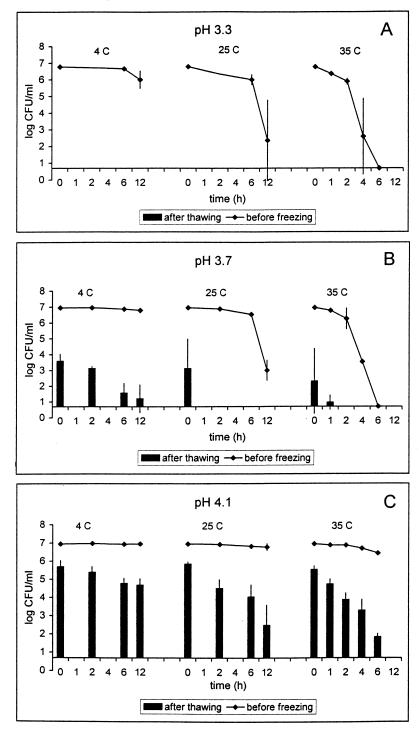

Regardless of prior storage conditions, the freeze-thaw treatment alone reduced numbers of E. coli O157:H7 by at least 5 log10 units in pH 3.3 apple cider. Likewise, storage in pH 3.3 apple cider for 6 h at 35°C also resulted in a 5-log10-unit decrease in cell numbers. But short-term storage treatments of 12 h at 4°C, 6 h at 25°C, and 12 h at 25°C resulted in reductions of <1.0, <1.0, and 4.4 log10 CFU/ml (Fig. 1A). Because of the lethality of freeze-thawing or treatment for 6 h at 35°C without addition of organic acids, the effects of added organic acids on E. coli O157:H7 survival in pH 3.3 apple cider were not studied.

FIG. 1.

Survival of E. coli O157:H7 (mixture of strains ATCC 43895, C7927, and USDA-FSIS-380-94) in pH 3.3 (A), 3.7 (B), and 4.1 (C) apple cider during storage at 4, 25, or 35°C and after subsequent freezing (−20°C; 48 h) and thawing (4°C; 4 h). Lines represent the concentrations of viable cells at the end of storage at the temperature and time indicated; bars indicate the concentrations of surviving cells determined after storage in cider and freeze-thawing at the indicated sample time point. The detection limit was 0.7 log10 CFU/ml. Results represent averages of three independent trials. Error bars, standard deviations.

(ii) E. coli O157:H7 in pH 3.7 apple cider.

In the absence of added organic acids, freezing and thawing alone were not sufficient to eliminate E. coli O157:H7 from pH 3.7 cider, as this treatment resulted in a ≤4.6-log10-unit reduction in cell numbers. However, storing the cider at least 6 h at 4°C, 2 h at 25°C, or 1 h at 35°C sensitized the cells such that ensuing freezing and thawing resulted in a ≥5-log10-unit reduction. A 6-h storage at 35°C without freezing and thawing also reduced cell numbers by ≥5 log10 units, but storage at 25 or 4°C for 12 h reduced numbers only by 4.0 and 0.2 log10 units, respectively (Fig. 1B). Compared to cider without added organic acids, cider with the addition of organic acids showed only slight differences in survival of E. coli O157:H7. Greater lethality, relative to that in cider without added organic acids, was obtained only in the presence of 0.1% lactic acid or sorbic acid, where a ≥5-log10-unit reduction was achieved after 4 h at 35°C or in the presence of 0.1% sorbic acid after 12 h of storage at 25°C. Depending on the cider temperature at inoculation, addition of propionic acid resulted in a 4.0- to >5.0-log10-unit reduction after freezing and thawing without any prior storage. Interestingly, the presence of lactic acid at 0.1% at 4 or 25°C somewhat enhanced the survival of E. coli O157:H7 compared to apple cider without added organic acids. A 6- or 12-h storage at 4°C combined with freezing and thawing did not result in a ≥5-log10-unit reduction as it did in the absence of added organic acids. Also, a 4-h-longer storage at 25°C combined with freezing and thawing was required to achieve a ≥5-log10-unit reduction in cider with 0.1% lactic acid compared to cider with no added organic acids (data not shown). To summarize, at least a 5-log10-unit reduction in E. coli O157:H7 was obtained in pH 3.7 apple cider without adding organic acids if the cider was treated as follows: 6 h of storage at 4°C followed by freezing and thawing, 2 h of storage at 25°C followed by freezing and thawing, 1 h of storage at 35°C followed by freezing and thawing, or 6 h of storage at 35°C.

(iii) E. coli O157:H7 in pH 4.1 apple cider.

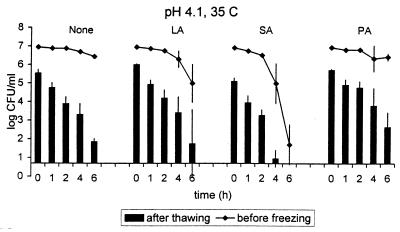

At pH 4.1, which was the highest tested, only a few combinations of treatments were able to reduce the cell concentration by ≥5 log10 units. In the absence of added organic acids, only the most severe treatment, a 6-h storage at 35°C followed by freezing and thawing, achieved sufficient lethality (Fig. 1C). Of the added organic acids, only 0.1% sorbic acid enhanced the inactivation compared to that in cider without added organic acids. A ≥5-log10-unit reduction was achieved by adding 0.1% sorbic acid followed by storage at 25°C for 12 h and then freezing and thawing; adding sorbic acid, followed by storage at 35°C for 4 h and then freezing and thawing; or storage at 35°C for 6 h. The effectiveness of the storage at 35°C in the presence of added organic acids followed by freezing and thawing is illustrated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Survival of E. coli O157:H7 (mixture of strains ATCC 43895, C7927, and USDA-FSIS-380-94) in pH 4.1 apple cider during 6-h storage at 35°C in the presence of added lactic acid (LA), sorbic acid (SA), or propionic acid (PA) and after subsequent freezing (−20°C; 48 h) and thawing (4°C; 4 h). Lines represent the concentrations of viable cells at the end of storage at the temperature and time indicated; bars indicate the concentrations of surviving cells determined after storage in cider and freeze-thawing at the indicated sample time point. The detection limit was 0.7 log10 CFU/ml. Results represent averages of three independent trials. Error bars, standard deviations.

As with pH 3.7 apple cider, lactic acid somewhat enhanced the survival of E. coli O157:H7. Except for cider treated with 0.1% lactic acid plus 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing, the longest storage times at 4, 25, or 35°C followed by freezing and thawing resulted in 0.5 to 1.6 log10 CFU less lethality per ml than in the corresponding experiments using cider with no added organic acids. Generally, better reduction in numbers of E. coli O157:H7 was achieved at pH 3.7 than at pH 4.1. Similarly, cells died faster at pH 3.3 than at pH 3.7. In the presence of added organic acids the cells behaved in the same manner.

In summary, a 5-log10-unit reduction in numbers of E. coli O157:H7 in pH 4.1 apple cider was achieved with the following treatments: 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing; 0.1% sorbic acid plus 12 h at 25°C plus freeze-thawing; 0.1% sorbic acid plus 6 h at 35°C; or 0.1% sorbic acid plus 4 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing.

Efficacy of short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; freezing and thawing; and/or addition of organic acids in reducing the numbers of S. typhimurium DT104 organisms by 5 log10 units in apple cider.

Survival of S. typhimurium DT104 after short-term storage at 4, 25, or 35°C; freezing (−20°C for 48 h) and thawing (4 h at 4°C); and/or in the presence of organic acids (0.1% lactic acid or 0.1% sorbic acid) was monitored in pH 3.3, 3.7, and 4.1 apple cider. The initial concentration of cells in cider was 6.0 to 6.7 log10 CFU/ml.

Numbers of S. typhimurium DT104 organisms decreased by ≥5 log10 units in pH 3.3 apple cider which was only frozen and thawed. These results are similar to those for E. coli O157:H7. At this pH, a ≥5-log10-unit reduction in numbers of S. typhimurium DT104 organisms also occurred during storage at 25°C for 12 h or at 35°C for 2 h. These treatments, however, did not reduce E. coli O157:H7 populations by 5 log10 units (data not shown).

The freeze-thaw treatment alone was sufficient to get the desired ≥5-log10-unit reduction in cell concentrations in pH 3.7 apple cider. For E. coli O157:H7, a ≥5-log10-unit reduction was only achieved when freeze-thawing followed storage of 6, 2, and 1 h at 4, 25, and 35°C, respectively. As with E. coli O157:H7, a 6-h storage at 35°C, led to a ≥5-log10-unit reduction of S. typhimurium DT104 numbers (data not shown).

In pH 4.1 apple cider without added organic acids, storage for at least 6 h at 25°C followed by freezing and thawing or for at least 4 h at 35°C followed by freezing and thawing was required to reduce the concentration of S. typhimurium DT104 by ≥5 log10 units. There was a small increase in lethality when 0.1% sorbic acid was added. A 6-h storage at 4°C followed by freezing and thawing, 6-h storage at 35°C alone, or 2-h storage at 35°C followed by freezing and thawing resulted in ≥5-log10-unit reductions of S. typhimurium DT104 when the cider contained 0.1% added sorbic acid. As previously described for E. coli O157:H7, lactic acid had no effect or slightly enhanced the survival of S. typhimurium DT104 during 12 h of storage at 4 or 25°C as well as after freezing and thawing following all storage conditions tested (data not shown). Overall, any treatment(s) that reduced the concentration of E. coli O157:H7 by ≥5 log10 units in pH 3.3, 3.7, or 4.1 apple cider had at least the same lethality against the tested strains of S. typhimurium DT104.

Yeast and mold growth during 6-h storage at 35°C.

The concentrations of yeast and mold cells were determined at the start and completion of 6-h storage at 35°C in cider containing no added organic acids, 0.1% lactic acid, or 0.1% sorbic acid. The initial yeast counts were 4.1 log10 CFU/ml and mold counts were 2.4 log10 CFU/ml. There was no statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in yeast and mold counts in the ciders tested, except the addition of 0.1% sorbic acid resulted in a significant 1.4-log10-unit reduction (P < 0.05) in mold counts (data not shown). These results show that 6-h storage at 35°C in the presence or absence of added organic acids did not lead to an increase in the yeast or mold counts in apple cider and, therefore, did not have a negative effect on the microbial quality of apple cider.

Consumer preference evaluation of apple cider.

Results from taste panels of cider treated with the most effective treatments to eliminate E. coli O157:H7 are presented in Table 1. In panel 1, the cider stored for 6 h at 35°C and the frozen and thawed cider were significantly preferred over pasteurized cider (P < 0.05). Similarly, in panel 2, cider with a combined treatment of 6 h at 35°C plus freeze-thawing was significantly preferred (P < 0.05) over pasteurized cider and over the cider with 0.1% sorbic acid stored 6 h at 35°C. However, when pasteurized cider was compared to cider with 0.1% sorbic acid or lactic acid treated by 6 h of storage at 35°C and freeze-thawing, pasteurized cider was viewed as significantly better (P < 0.05). These results show that cider treated either with 6 h of storage at 35°C or freezing and thawing, or the two treatments combined, was always preferred over pasteurized cider. Ciders with lactic or sorbic acid added were either not significantly different from (P < 0.05) or were significantly less preferred than (P < 0.05) pasteurized cider. All scores in all three taste panels were between 6 and 4, which represent “like moderately” and “neither like nor dislike,” respectively.

TABLE 1.

Consumer preference evaluation of apple cider exposed to various treatmentsa

| Taste panelb | Treatment(s) | Mean scorec |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pasteurizationd | 4.14 A |

| 6 h at 35°C | 5.49 B | |

| Freeze-thawe | 5.59 B | |

| 2 | Pasteurization | 4.54 C |

| 0.1% Sorbate + 6 h at 35°C | 4.75 C | |

| 6 h at 35°C + freeze-thaw | 5.94 D | |

| 3 | Pasteurization | 5.47 E |

| 0.1% Sorbate + 6 h at 35°C + freeze-thaw | 4.99 F | |

| 0.1% Lactate + 6 h at 35°C + freeze-thaw | 5.18 F |

Apple cider was exposed to treatments that reduced the concentration of E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT 104 by 5 log units.

At least 175 participants evaluated each sample.

Apple cider was evaluated on a 7-point scale: 7, like very much; 6, like moderately; 5, like slightly; 4, neither like nor dislike; 3, dislike slightly; 2, dislike moderately; 1, dislike very much. Mean scores within one taste panel followed by different letters are significantly different at the 5% level.

Apple cider was pasteurized at 72°C for 15 s.

Apple cider was frozen at −20°C for 48 h and thawed at 4°C for 4 h.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated for the first time simple nonpasteurization treatment combinations that reduced the numbers of E. coli O157:H7 by the FDA-required 5 log10 units in apple cider. The treatments proven to be effective included various combinations of traditional and inexpensive preservation methods, specifically short-term storage at 25 or 35°C, freezing and thawing, and/or addition of organic acids, all of which could be applicable and affordable for small apple cider mills. Selection of the correct treatment combination and its effectiveness depended primarily on the pH of the apple cider. According to Mattick and Moyer (21) the typical range for pH in apple juice is 3.3 to 4.1, with malic acid concentration ranging from 0.15 to 0.19%. The average pH of a cider does not necessarily ensure the product safety, as E. coli O157:H7 and certain Salmonella strains will survive, but not grow, for a significant proportion of normal cider shelf life (24, 28, 29, 39). In our study the pH of the cider was an important determinant affecting the severity of the treatments needed to achieve 5-log10-unit reductions in cell numbers, with cell death inversely proportional to the cider pH.

At the moment, cider producers’ choices of methods for reducing the concentrations of pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium by 5 log10 units are either pasteurization or UV light treatment, which both require an investment of money (19) that may be prohibitive for small cider producers. No other practical treatments are commercially available for cider producers. However, freezing is a common method for extending the shelf life of apple cider and was shown to have considerable lethality against E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT104. Mechanical injury of frozen bacterial cells is caused by intra- and extracellular ice crystals. During freezing, as water is removed, there is a concentration of cell solutes which can lead to dissociation of cellular lipoproteins. During thawing, growth of ice crystals can physically damage the cell (8). However, it is known that freezing and thawing in the absence of other stresses will not fully eliminate pathogen populations. For example, Obafemi and Davis (25) found stationary-phase S. typhimurium cells relatively resistant to freezing and thawing in chicken exudate. However, the cells’ resistance to freezing and thawing was substantially reduced by first cold shocking the cells at 5°C and then exposing them to a solution containing 5 mg of free available chlorine per liter and 1% succinic acid (pH 2.5) for 20 min. The efficacy of similar prefreezing stresses for destroying pathogenic bacteria in apple cider has not been previously established. Combined treatments exposing cells to the low pH of the cider, warm temperature, and/or added organic acids were shown in this study to sensitize E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT104 cells to subsequent freezing and thawing. Our results also showed that the survival of E. coli O157:H7 in apple cider during a 6-h storage period was inversely related to storage temperature. Reduced survival of E. coli O157:H7 in acidic foods at higher temperatures has also been seen in studies with apple juice and cider (24, 36, 39), mayonnaise (27), and ketchup (35). Our study also highlighted how storage of E. coli O157:H7 cells at warm temperature and low pH sensitized cells to subsequent freeze-thaw stress. The sensitizing effect of warm short-term storage was observed in all combinations of treatments. In our earlier study (15) we demonstrated a similar sensitizing effect of a warm storage treatment to subsequent heat stress. E. coli O157:H7 cells stored in apple juice (pH 3.4) at 21°C up to 6 h become significantly more heat sensitive at 61°C than cells heated shortly after exposure to the acidic conditions of juice. During the storage at 4°C the thermotolerance decreased more slowly than at 21°C.

The inhibitory effect of organic acids against bacterial cells is based on the pH of the juice, the pKa of the acid, the antimicrobial activity of the undissociated form of acid, and specific effects of particular acids (32). The undissociated organic acid can readily permeate the cell membrane, whereupon dissociation occurs and the internal pH of the cell drops (38). The predominant organic acid in apple cider is malic acid; several others, including citric acid, are present in varying amounts (13). As malic and citric acids in low concentrations had been shown to have no lethality against E. coli O157:H7 in apple juice (36), this study instead used lactic, sorbic, and propionic acids, all of which are used in preserving foods. In our previous study, lactic acid was more bactericidal than malic or citric acids against E. coli O157:H7 in a synthetic medium. Cells injured by lactic acid did not survive upon transfer to highly acidic synthetic gastric fluid. Sorbate has been shown to inhibit the growth of yeasts, molds, and many bacteria (for a detailed review see the work of Sofos and Busta [33]). Cider producers often use 0.1% sorbate in their cider, but its effectiveness against E. coli O157:H7 at refrigeration temperatures is reportedly marginal (24, 39). Our results, however, support the use of sorbate, particularly as a component of a combined treatment to reduce the numbers of E. coli O157:H7 by 5 log10 units.

As a final step of our study, we tested the acceptability to consumers of cider exposed to treatments shown to result in a 5-log10-unit reduction in E. coli O157:H7 concentration at one of the pH values tested. Interestingly, ciders treated with 6 h of storage at 35°C and freeze-thawing separately or in combination were preferred over pasteurized cider. Short-term warm temperature storage particularly may have matured the flavor of the cider by allowing enzymatic reactions to occur. The temperature of apple beverages during processing has been shown to significantly affect the flavor profile (34). Further studies are needed to evaluate changes in the flavor chemistry during the 6-h storage at 35°C.

Only one lot of cider, which was heat-sterilized prior to inoculation, was used in this study, so other lots of unheated cider, which may vary in composition, should be tested in the future. Nonetheless, the results of the present study point to potential processing steps which will ensure that apple cider is safe without inflicting excessive financial hardship on the apple cider industry. We have demonstrated that a 5-log10-unit reduction in numbers of E. coli O157:H7 and S. typhimurium DT104 organisms in apple cider may be achieved without pasteurization, by combining practical and inexpensive preservation methods, such as short-term storage at 35°C, freezing and thawing, and/or addition of organic acids. These treatments do not decrease the quality of cider as measured by the yeast and mold concentrations or consumer preference. Our results emphasize the importance of proper blending of apples used to ensure that cider pH is low enough to enhance the lethality of subsequent treatments. The described treatments for reducing E. coli O157:H7 concentrations in apple cider by 5 log10 units are beneficial from a public health viewpoint and provide a simple method for all cider mills to produce pathogen-free cider.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the University of Wisconsin—Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences’ Hatch Fund.

We extend our appreciation to John B. Luchansky at the Food Research Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for providing bacterial cultures, and Wei Dong of the Sensory Analysis Laboratory, University of Wisconsin—Madison, for directing consumer preference evaluation trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold K W, Kaspar C W. Starvation- and stationary-phase-induced acid tolerance in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2037–2039. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.2037-2039.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin M M, Datta A R. Acid tolerance of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1669–1672. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1669-1672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besser R E, Lett S M, Weber J T, Doyle M P, Barret T J, Wells J G, Griffin P M. An outbreak of diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh-pressed apple cider. JAMA. 1993;269:2217–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Disease Control. Salmonella typhimurium outbreak traced to a commercial apple cider—New Jersey. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1975;24:87–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with drinking unpasteurized commercial apple juice—British Columbia, California, Colorado and Washington, October 1996. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1996;45:975–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection and cryptosporidiosis associated with drinking unpasteurized apple cider—Connecticut and New York, October 1996. Morbid Mortal Weekly Report. 1997;46:4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella serotype typhimurium—United States, 1996. Morbid Mortal Weekly Report. 1997;46:308–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Kest S E, Marth E H. Freezing of Listeria monocytogenes and other microorganisms: a review. J Food Prot. 1992;55:639–648. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.8.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Food and Drug Administration. Food labeling: warning and notice statements; labeling of juice products. Federal Register. 1998;63:20486–20493. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass K A, Loeffelholz J M, Ford J P, Doyle M P. Fate of Escherichia coli O157:H7 as affected by pH and sodium chloride in fermented, dry sausage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2513–2516. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2513-2516.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorden J, Small P L C. Acid resistance in enteric bacteria. Infect Immun. 1993;61:364–367. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.364-367.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:60–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haard N F. Characteristics of edible plant tissues. In: Fennema O R, editor. Principles of food science, part 1. Food chemistry. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1976. pp. 677–764. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathcox A K, Beuchat L R, Doyle M P. Death of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in real mayonnaise and reduced-calorie mayonnaise dressing as influenced by initial population and storage temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4172–4177. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4172-4177.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingham S C, Uljas H E. Prior storage conditions influence the destruction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 during heating of apple cider and juice. J Food Prot. 1998;61:390–394. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keene W E, McAnulty J M, Hoesly F C, Williams P, Jr, Hedberg K, Oxman G L, Barret T J, Pfaller M A, Fleming D W. A swimming-associated outbreak of hemorrhagic colitis caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella sonnei. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:579–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keene W E, Sazie E, Kok J, Rice D H, Hancock D D, Balan V K, Zhao T, Doyle M D. An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections traced to jerky made from deer meat. JAMA. 1997;277:1229–1231. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540390059036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khazanie R. Statistics in a world of applications. New York, N.Y: HarperCollins College Publishers Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozempel M, McAloon A, Yee W. The cost of pasteurizing apple cider. Food Technol. 1998;52:50–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leyer G J, Wang L-L, Johnson E A. Acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 increases survival in acidic foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3752–3755. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3752-3755.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattick L R, Moyer J C. Composition of apple juice. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1983;66:1251–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCandless L. New York cider industry learns to make safe cider. Great Lakes Fruit Growers News. 1997;1997(March):11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millard P S, Gensheimer K F, Addiss D G. An outbreak of cryptosporidiosis from fresh pressed apple cider. JAMA. 1994;272:1592–1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller L G, Kaspar C W. Escherichia coli O157:H7 acid-tolerance and survival in apple cider. J Food Prot. 1994;57:460–464. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obafemi A, Davis R. The destruction of Salmonella typhimurium in chicken exudate by different freeze-thaw treatments. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;60:381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb05082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padhye N V, Doyle M P. Escherichia coli O157:H7: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and methods of detection in food. J Food Prot. 1992;55:555–565. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.7.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raghubeer E V, Ke J S, Campbell M L, Mayer R S. Fate of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other coliforms in commercial mayonnaise and refrigerated salad dressing. J Food Prot. 1995;58:13–18. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson J F, Woodward C F, Harrington W O, Hills C H, Hayes K M, Nold T. Making and preserving apple cider. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Farmers’ bulletin no. 2125. U.S. Washington, D.C: Department of Agriculture; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roering, A. M., J. B. Luchansky, A. M. Ihnot, S. E. Ansay, C. W. Kaspar, and S. C. Ingham. Comparative survival of Salmonella typhimurium DT 104, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in preservative-free apple cider and simulated gastric fluid. Int. J. Food Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sage J R, Ingham S C. Evaluating survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in frozen and thawed apple cider: potential use of a hydrophobic grid membrane filter-SD-39 agar method. J Food Prot. 1998;61:490–494. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salunkhe D K. Sorbic acid as a preservative for apple juice. Food Technol. 1955;9:590. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silliker J H, Elliot R P, Baird-Parker A C, Bryan F L, Christian J H B, Clark D S, Olson J C, Jr, Roberts T A. Microbial ecology. 1. Factors affecting life and death of microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sofos J N, Busta F F. Antimicrobial activity of sorbate. J Food Prot. 1981;44:614–622. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-44.8.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su S K, Wiley R C. Changes in apple juice flavor compounds during processing. J Food Sci. 1998;63:688–691. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai Y-W, Ingham S C. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella spp. in acidic condiments. J Food Prot. 1997;60:751–755. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uljas H E, Ingham S C. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in synthetic gastric fluid after cold and acid habituation in apple juice or trypticase soy broth acidified with hydrochloric acid or organic acids. J Food Prot. 1998;61:939–947. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.8.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace J S, Cheasty T, Jones K. Isolation of Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 from wild birds. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:399–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wart A D. Relationships between the resistance of yeasts to acetic, propionic and benzoic acids and to methyl paraben and pH. Int J Food Microbiol. 1989;8:343–349. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao T, Doyle M P, Besser R E. Fate of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple cider with and without preservatives. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2526–2530. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2526-2530.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao T, Doyle M P, Shere J, Garber L. Prevalence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a survey of dairy herds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1290–1293. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1290-1293.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]