Abstract

Background:

Pathologic evidence of Alzheimer disease (AD) is detectable years before onset of clinical symptoms. Imaging-based identification of structural changes of the brain in people at genetic risk for early-onset AD may provide insights into how genes influence the pathologic cascade that leads to dementia.

Purpose:

To assess structural connectivity differences in cortical networks between cognitively normal autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) mutation carriers versus noncarriers and to determine the cross-sectional relationship of structural connectivity and cortical amyloid burden with estimated years to symptom onset (EYO) of dementia in carriers.

Materials and Methods:

In this exploratory analysis of a prospective trial, all participants enrolled in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network between January 2009 and July 2014 who had normal cognition at baseline, T1-weighted MRI scans, and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) were analyzed. Amyloid PET imaging using Pittsburgh compound B was also analyzed for mutation carriers. Areas of the cerebral cortex were parcellated into three cortical networks: the default mode network, frontoparietal control network, and ventral attention network. The structural connectivity of the three networks was calculated from DTI. General linear models were used to examine differences in structural connectivity between mutation carriers and noncarriers and the relationship between structural connectivity, amyloid burden, and EYO in mutation carriers. Correlation network analysis was performed to identify clusters of related clinical and imaging markers.

Results:

There were 30 mutation carriers (mean age ± standard deviation, 34 years ± 10; 17 women) and 38 noncarriers (mean age, 37 years ± 10; 20 women). There was lower structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network in mutation carriers compared with noncarriers (estimated effect of mutation-positive status, −0.0266; P = .04). Among mutation carriers, there was a correlation between EYO and white matter structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network (estimated effect of EYO, −0.0015, P = .01). There was no significant relationship between cortical global amyloid burden and EYO among mutation carriers (P > .05).

Conclusion:

White matter structural connectivity was lower in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease mutation carriers compared with noncarriers and correlated with estimated years to symptom onset.

Summary

Structural integrity of white matter networks at diffusion tensor MRI in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease mutation carriers was associated with disease progression (P = .01).

Alzheimer disease (AD) has a prolonged prodromal and preclinical phase characterized initially by the development of silent pathologic changes followed by mild cognitive impairment and then dementia. However, clinical expression of dementia is variable, determined not only by pathologic changes but also by patient-specific factors that confer greater cognitive resilience or vulnerability to the pathologic processes of AD (1–3). Although recent advances in radionuclide imaging have enabled measurement of AD pathology in vivo, a means of measuring a physical network substrate underlying cognitive resilience has been lacking. There is currently great interest in characterizing changes in the white matter structural and cortical functional networks of the brain to better explain changes in cognition along the spectrum of AD (4–7). More specifically, there is a need to determine how pathologic changes influence network connectivity and how changes in network connectivity, in turn, mediate the onset of dementia.

Early-onset autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) provides a model for studying disease onset in AD years in advance of clinical symptoms. Although ADAD accounts for only 1% of patients with AD, the clinical and pathologic characteristics are partially similar to the more common sporadic late-onset AD (8). ADAD has high penetrance in mutation carriers and reasonable predictability of estimated years to symptom onset (EYO) of clinical dementia, based on age at onset of a parental mutation carrier. Previous studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to study individuals with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and AD have shown that amyloid deposition is significantly associated with degraded whole-brain structural connectivity in sporadic AD (4), and in the case of ADAD, white matter changes are associated with EYO and mutation status (9,10). However, it is not known whether such early structural changes might mediate the onset of dementia. We therefore aimed to assess structural connectivity differences in cortical association networks between cognitively normal ADAD mutation carriers and noncarriers and to determine the relationship of both structural connectivity and cortical amyloid burden with EYO of dementia in mutation carriers. Herein, we consider EYO of dementia a surrogate measure for disease progression in the absence of clinical symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

We performed an exploratory analysis of a prospective trial, studying all participants enrolled in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) study, data freeze 6, who were cognitively normal at baseline and who had T1-weighted MRI, DTI, and Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) PET scans available at baseline. DIAN is a landmark study involving an international network of 17 performance sites (as of 2021), coordinated by Washington University in St Louis, Mo, with a goal of identifying longitudinal biologic marker changes in ADAD, particularly in asymptomatic mutation carriers (11,12). Prior publications evaluating the DIAN cohort can be found at https://dian.wustl.edu/our-research/observational-study/dian-observational-study-publications. Participants included those with ADAD mutations (in the presenilin 1, presenilin 2, or amyloid precursor protein genes) and those without ADAD mutations from the same families. EYO was determined with a semistructured interview carried out by DIAN site clinicians of study participants, collateral sources, and other informants, after which a determination was made of the initial appearance of cognitive decline in the affected parent (11). All sites received institutional review board approval, including for data analysis for the current study. All data were anonymized and centrally housed by DIAN.

T1-weighted (Anatomic) Image Acquisition and Processing

All MRI scans in the analysis were acquired with use of 3.0-T MRI scanners (Siemens Magnetom Trio Tim or Magnetom Verio and Philips Achieva; magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo, or MPRAGE, sequence; acquisition image resolution, 1.05 × 1.05 × 1.2 mm; repetition time, 2300 msec; echo time, 2.95 msec). MRI was performed using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative protocol (13). The T1-weighted images were segmented by using FreeSurfer’s default segmentation method with the Desikan-Killiany atlas (FreeSurfer, version 5.3.0; https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) (14). This produced a surface vertex representation of the cortex, which was used to conform a previously described empirically derived standard atlas of seven resting-state networks to each participant and create a volumetric representation of each network’s cortical regions in the individual’s native space (15) (Fig 1). Normalized total cerebral white matter was calculated by dividing the volume of the segmented white matter by the estimated intracranial volume, both calculated with use of FreeSurfer. The analyses were performed by one author (J.W.P., with 15 years of experience).

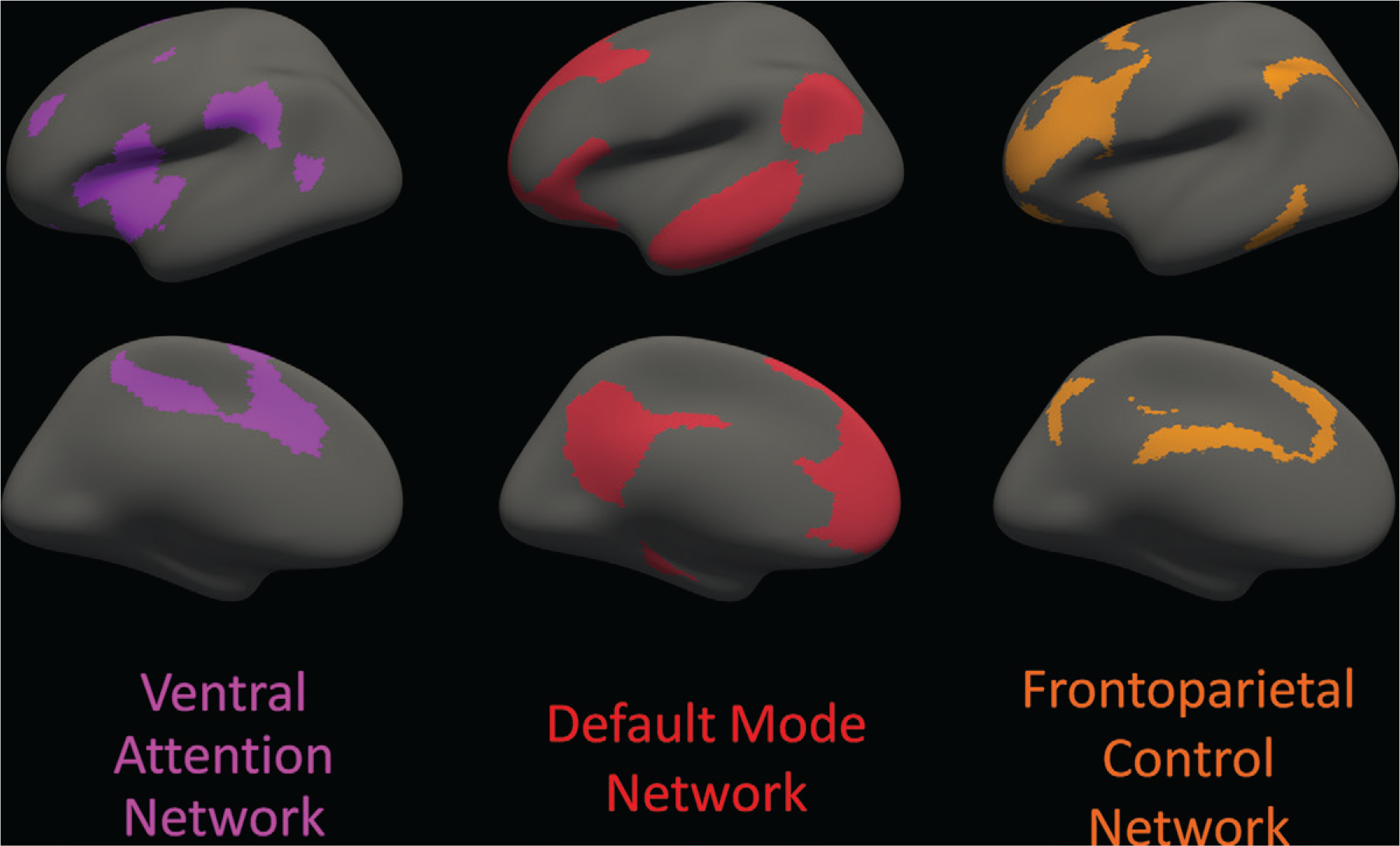

Figure 1:

Cortical areas involved with each of the three distributed cortical association networks analyzed are displayed on an inflated brain surface, viewed from the lateral aspect (top row) and the medial aspect (bottom row) of the left hemisphere; the right hemisphere (not shown) is nearly a mirror image of the left hemisphere. The regions are based on a standard functional parcellation of the human brain from a resting-state functional MRI study of 1000 healthy individuals. The three specific networks of interest are the ventral attention network (purple), default mode network (red), and frontoparietal control network (orange). Cortical regions in the ventral attention network include portions of the middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis and pars opercularis), insula, supramarginal gyrus, posterior superior temporal sulcus, superior frontal gyrus, anterior and posterior cingulate, and precuneus. Cortical regions in the default mode network include portions of the medial prefrontal cortex; precuneus; posterior cingulate; parahippocampal gyrus; superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri; and inferior parietal gyrus. Cortical regions in the frontoparietal control network include portions of the superior and middle frontal gyri, inferior temporal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, anterior and posterior cingulate, and precuneus. Note that some of the gyral-based parcellated areas are components of more than one network defined by the functional parcellation. Source.–Reference 15.

White Matter Structural Connectivity Analysis

DTI acquisition parameters were echo planar sequence, b = 1000 sec/mm2; either b0 + 64 (for Siemens Magnetom Trio Tim or Magnetom Verio scanners) or b0 + 32 isotropically distributed diffusion-sensitizing gradients (for Phillips Achieva scanners); and acquisition image resolution, 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm. White matter structural connections were constructed from the processed DTI images using DSI Studio (http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org, build from July 13, 2015), with seeds in the cerebral and cerebellar white matter, an angular threshold of 60°, and a step size of 1.25 mm. The b0 images from the DTI scans were registered to the T1-weighted anatomic scans using boundary-based registration, as implemented in FreeSurfer’s bbregister. Each of the resting-state network regions for each participant was set as a node (Fig 1). A connection, or “fiber,” between two cortical regions or nodes was defined as a curve along the major axis of anisotropy that started at one of the cortical regions and terminated at the other. The Brain Connectivity Toolbox (version 2019–03-03, https://sites.google.com/site/bctnet) was used to calculate the weighted global efficiency of the white matter structural connections between cortical nodes within each network. The weighted global efficiency is the average inverse shortest path length between any two nodes in the network (16). In our study, the weighting factor was the average fractional anisotropy of the fibers connecting two cortical regions. Prior studies have demonstrated that global metrics provide good to excellent reproducibility in measurement, and weighting with fractional anisotropy provides reasonable reproducibility (17,18). The visual and somatomotor networks were not included in our analysis because these networks each contained only two nodes (one in each hemisphere). In addition, the limbic and dorsal attention networks were not included because these networks did not exhibit connections between all nodes for each participant, which caused the global efficiency to be calculated as 0. Therefore, for these four networks, global efficiency for each participant could not be calculated. The final analysis included global efficiency calculated for the default mode network (consisting of 11 nodes), ventral attention network (consisting of 10 nodes), and frontoparietal control network (consisting of 12 nodes) (Fig 2). Cortical regions in the ventral attention network include portions of the middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis and pars opercularis), insula, supramarginal gyrus, posterior superior temporal sulcus, superior frontal gyrus, anterior and posterior cingulate, and precuneus. Cortical regions in the default mode network include portions of the medial prefrontal cortex; precuneus; posterior cingulate; parahippocampal gyrus; superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri; and inferior parietal gyrus. Cortical regions in the frontoparietal control network include portions of the superior and middle frontal gyri, inferior temporal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, anterior and posterior cingulate, and precuneus.

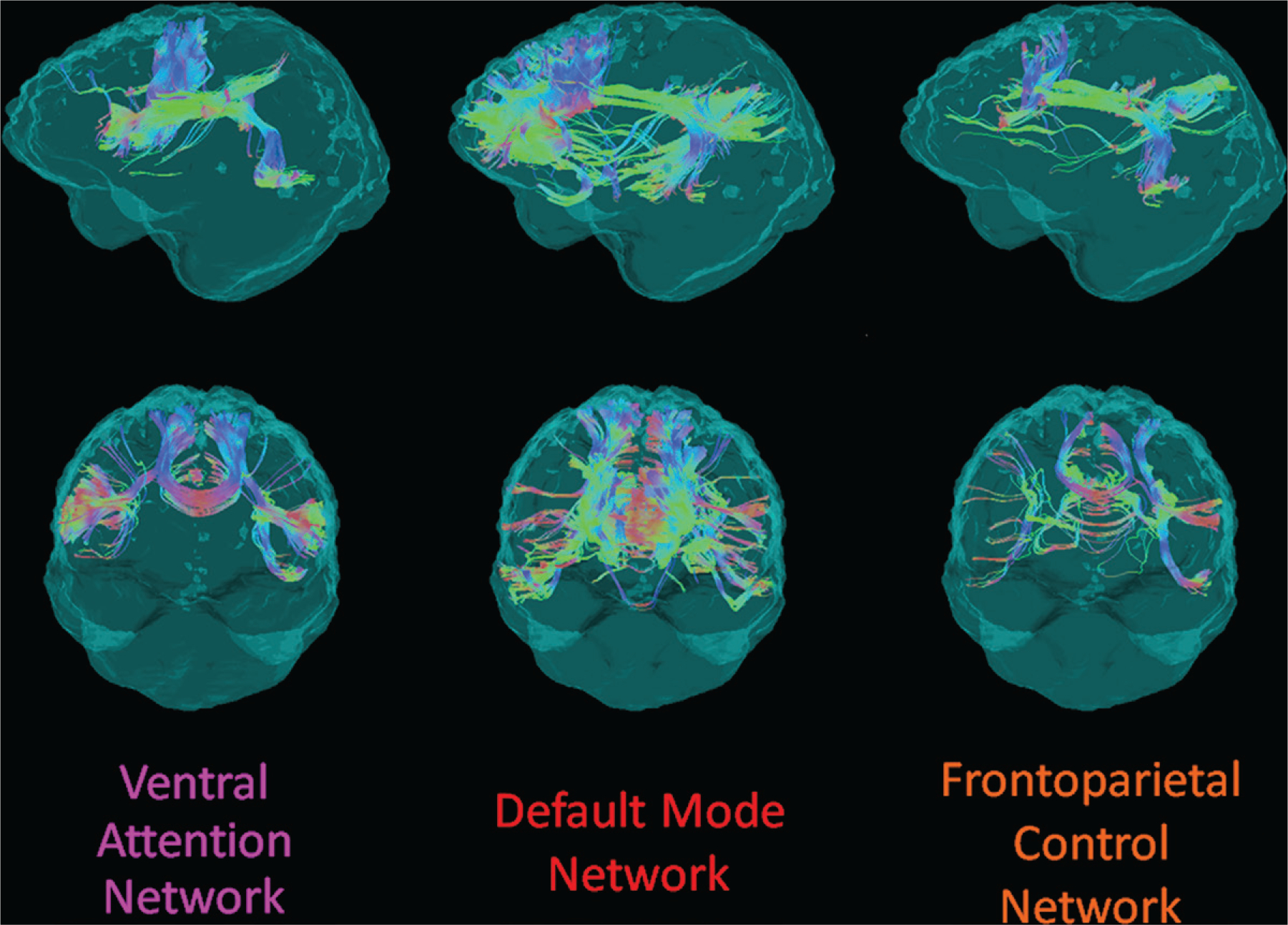

Figure 2:

Example structural connectivity of the three analyzed distributed cortical networks from one participant in the DIAN cohort, viewed laterally from the left (top row) and anteriorly (bottom row). The networks are from a standard functional parcellation of the human cortex shown in Figure 1. Streamline colors indicate directionality of water diffusion at diffusion tensor imaging: green = anteroposterior, red = left-right, blue = superoinferior.

In addition to the intranetwork analysis of these three networks, an internetwork analysis was performed. This involved calculating the global efficiency of connections between all nodes of two different networks (eg, the default mode network and frontoparietal control network). The graphs were constructed in a similar way to the intranetwork analysis, and the global efficiency of the resultant internetwork graph was analyzed. The analyses were performed by one author (J.W.P.).

Amyloid PET Analysis

The mean global summary standardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) from PiB PET scans was used in the analysis. These values were calculated by the DIAN Imaging Core. Briefly, this included region of interest segmentation from T1-weighted MRI scans using FreeSurfer, PET head motion correction, T1-weighted MRI scan registration to PET, and region of interest activity for each PET frame extracted to create time-activity curves and calculate SUVr. Image processing is further described in reference 19.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were computed for demographics. General linear models were created to analyze relationships between structural connectivity, mutation status, and EYO in all participants with normal cognition, with adjustments for sex, age, EYO, years of education, apolipoprotein E status (positive or negative for the presence of at least the E4 allele), Mini-Mental State Examination score, and normalized white matter volume. The full statistical model is included in Appendix E1 (online).

General linear models were then created for mutation carriers with normal cognition only, which were used to examine the relationship between white matter structural connectivity, amyloid burden, and EYO, with adjustments for sex, age, years of education, apolipoprotein status, Mini-Mental State Examination score, and normalized white matter volume. The full statistical model is included in Appendix E1 (online).

P < .05 was considered indicative of statistically significant difference. This was an exploratory study; no adjustments for multiple comparisons were performed. All statistical analyses were performed with use of R (version 3.0, https://www.r-project.org) by one author (J.W.P.).

Correlation Network Analysis

Correlation network analysis was applied to mutation carriers and noncarriers separately to identify clusters of related clinical and biologic marker variables. Further description of this technique is available in Appendix E1 (online). The analyses were performed by one author (D.G., with 20 years of experience).

Results

Participant Characteristics

There were 374 DIAN participants at the time of analysis. A total of 111 participants had T1-weighted, DTI, and processed PiB PET images, of whom 68 had normal cognition: 30 mutation carriers (mean age ± standard deviation, 34 years ± 10; 17 women) and 38 noncarriers (mean age, 37 years ± 10; 20 women). We found no evidence of differences in demographics, cognition, or statistical covariates between the mutation carrier and noncarrier groups (all P > .05) (Table 1). Mean whole cortex PiB PET SUVr ± standard deviation for mutation carriers with normal cognition was 1.58 ± 0.65 and for noncarriers with normal cognition was 1.04 ± 0.06 (P < .001). One mutation carrier who had normal cognition had EYO greater than 0, meaning that the mutation carrier had not developed clinical symptoms of AD even though that carrier’s age was greater than the expected age at onset of clinical symptoms.

Table 1:

Participant Demographics, Statistical Covariates, and Global Efficiency Metrics according to Mutation Status

| Mutation Status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Carrier (n = 30) | Noncarrier (n = 38) | P Value |

|

| |||

| Age (y) | 34 ± 10 (20–57) | 37 ± 10 (19–61) | .27 |

| Estimated years to symptom onset | −13.8 ± 9.0 (−28 to 3) | −9.4 ± 11.8 (−29 to 16) | .10 |

| Sex* | .93 | ||

| M | 13 | 18 | |

| F | 17 | 20 | |

| Education (y) | 15.7 ± 3.4 (11–24) | 15.1 ± 2.6 (10–21) | .41 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score | 30.0 ± 1.5 (24–30) | 29.2 ± 1.2 (25–30) | .46 |

| Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised | |||

| Logical memory IA-immediate | 14.0 ± 4.2 (4–22) | 14.3 ± 3.9 (5–24) | .73 |

| Logical memory IIA-delayed | 12.6 ± 4.8 (2–21) | 13.4 ± 3.9 (6–24) | .44 |

| Word list recall-immediate | 5.7 ± 1.9 (2–12) | 5.9 ± 2.2 (1–11) | .63 |

| Word list recall-delayed | 3.1 ± 2.1 (0–9) | 3.2 ± 2.4 (0–9) | .81 |

| Apolipoprotein E4 allele status* | >.99 | ||

| Positive | 8 | 9 | |

| Negative | 22 | 29 | |

| Global cortical PiB amyloid PET SUVr | 1.58 ± 0.65 (0.88–2.39) | 1.04 ± 0.06 (0.92–1.14) | <.001 |

| Normalized cerebral white matter volume (% intracranial volume) | 30.5 ± 2.0 (27.9–34.1) | 30.3 ± 2.0 (26.7–34.8) | .54 |

Note.—Unless otherwise specified, data are means ± standard deviations, with ranges in parentheses. P values are from analysis of variance or χ2 test of each variable versus mutation status, as appropriate. PiB = Pittsburgh compound B, SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio.

Data are numbers of participants.

Intranetwork Global Efficiency Analysis

Among all participants with normal cognition, mutation status had an effect on intranetwork global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network, with noncarrier participants having a higher global efficiency (model intercept, 0.0421; estimated effect of mutation-positive status, −0.0266, with standard error of 0.0124; P = .04) (Table 2). We found no evidence of an interaction between mutation status and EYO in this model.

Table 2:

Results of Fitting a General Linear Model of Intranetwork Global Efficiency in the Frontoparietal Control Network versus Mutation Status

| Variable | Estimated Effect* | Standard Error | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mutation-positive | −0.0266 | 0.0124 | .04 |

| EYO | −0.0005 | 0.0005 | .32 |

| Mutation-positive × EYO | −0.0013 | 0.0008 | .10 |

| Female sex | 0.0048 | 0.0078 | .54 |

| Education (y) | −0.0007 | 0.0013 | .59 |

| Apolipoprotein E4 allele positivity | 0.0036 | 0.0092 | .70 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score | 0.0022 | 0.0030 | .46 |

| Normalized cerebral white matter volume (% intracranial volume) | 0.1126 | 0.2228 | .62 |

Note.—Refer to Equation (E1) (online) for full model definition. EYO = estimated years to symptom onset.

The estimated effect represents the additive effect per unit rise in the variable on the global efficiency.

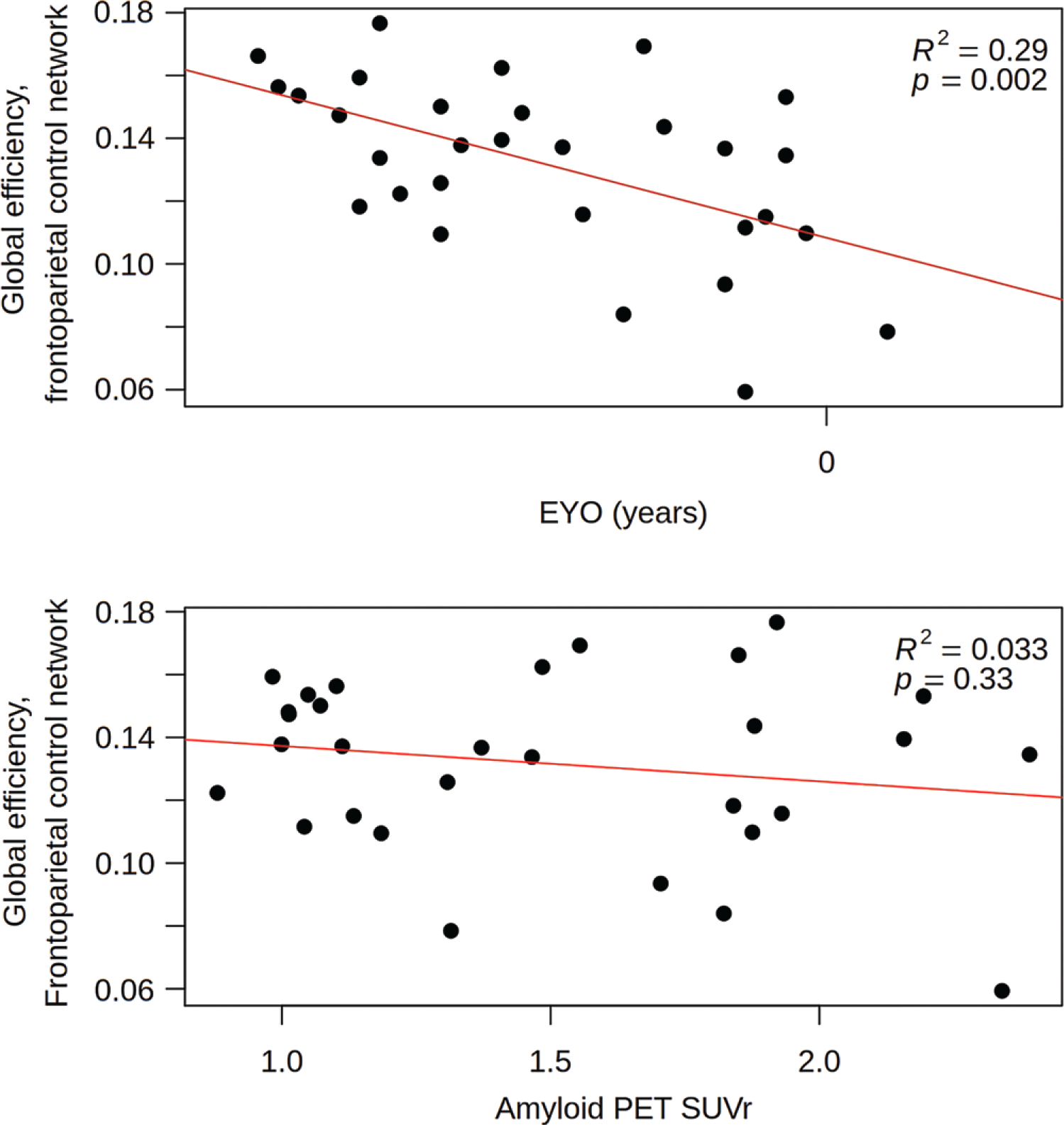

Among mutation carriers with normal cognition, after adjustment for age, sex, education, brain volume, apolipoprotein E4 allele positivity, and amyloid deposition, EYO had an effect on white matter structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network (model intercept, −0.0615; estimated effect of EYO, −0.0015, with standard error of 0.0006; P = .01) (Table 3). In this model, none of the other covariates had an effect on connectivity. We did not find evidence of such a relationship in either of the other networks. Plots of global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network versus EYO and PiB PET SUVr are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3:

Results of Fitting a General Linear Model of Global Efficiency in the Frontoparietal Control Network versus EYO for Mutation Carriers with Normal Cognition

| Variable | Estimated Effect* | Standard Error | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| EYO | −0.0015 | 0.0006 | .01 |

| Female sex | −0.0043 | 0.0098 | .66 |

| Education (y) | −0.0026 | 0.0015 | .08 |

| Apolipoprotein E4 allele positivity | 0.0114 | 0.01 | .31 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score | 0.0057 | 0.0033 | .10 |

| Normalized cerebral white matter volume (% intracranial volume) | 0.17 | 0.33 | .60 |

| PiB PET, total cortex SUVr | −0.0034 | 0.0104 | .74 |

Note.—Refer to Equation (E2) (online) for full model definition. EYO = estimated years to symptom onset, PiB = Pittsburgh compound B, SUVr = standardized uptake value ratio

The estimated effect represents the additive effect per unit rise in the variable on the global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network.

Figure 3:

Scatterplots show global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network versus estimated years to symptom onset (EYO) (top) and Pittsburgh compound B amyloid PET standardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) (bottom) in cognitively normal mutation-positive participants. The EYO axis in the top figure only has the 0 value plotted to protect against the unintended unblinding of mutation status for an individual at the extremes of the data, per Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network policy. The data in these plots, including R2 and P values, are not adjusted for multiple comparisons or for covariates that are in the statistical model defined in Equation (E2) (online).

Internetwork Global Efficiency Analysis

Among all participants with normal cognition, we found no evidence of an effect of mutation on internetwork global efficiency (all P > .05). Among mutation carriers with normal cognition, we found no evidence of an effect of EYO on internetwork global efficiency (all P > .05).

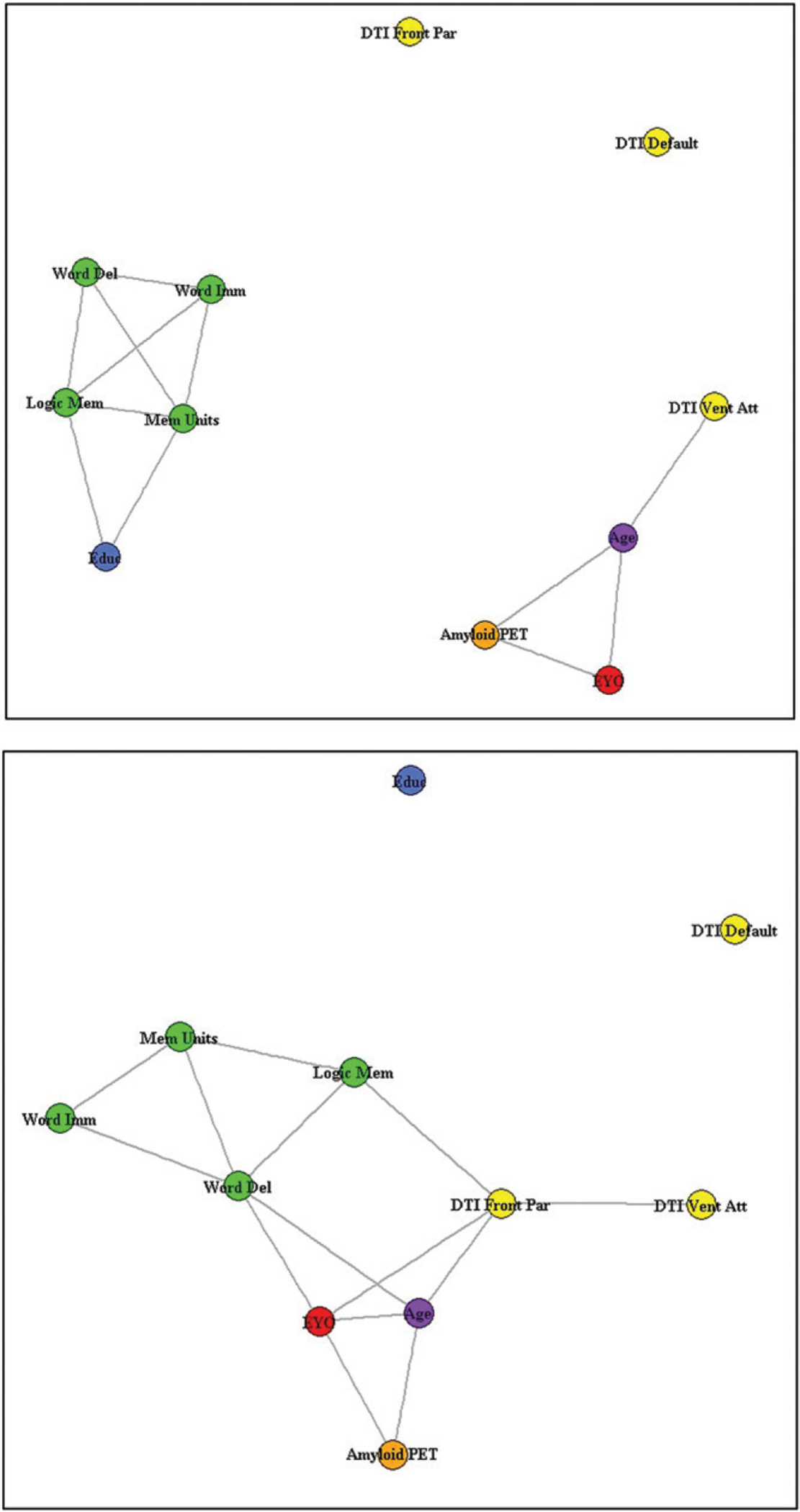

Correlation Network Analysis

The results of the multilayer clustering algorithm are represented by correlation network graphs, shown in Figure 4. In mutation carriers, there were relatively stronger correlations between EYO and clinical, amyloid, and structural connectivity variables (ρ ≥ 0.3). In noncarriers, the main cluster seen was intercorrelation among cognitive variables and education level (ρ ≥ 0.3).

Figure 4:

Correlation networks for noncarriers (top) and mutation carriers (bottom). Baseline clinical and biologic marker descriptors are denoted with circles. Circles are shaded orange for amyloid PET standardized uptake value ratio, yellow for structural connectivity measures, green for cognitive measures, purple for age, blue for education (Educ), and red for estimated years to symptom onset (EYO). The cognitive measures include word recall–immediate (Word Imm), word recall–delayed (Word Del), logical memory–immediate (Logic Mem), and logical memory–delayed (Mem Units). DTI = diffusion tensor imaging, Front Par = frontoparietal control network, Vent Att = ventral attention network.

Discussion

Our study used the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network cohort to analyze differences in white matter structural connectivity in three distributed cortical association networks in participants with normal cognition before estimated symptom onset with and without autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) mutations. The significant elevation of amyloid deposition is parallel to the reduction in white matter structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network in mutation carriers compared with noncarriers (estimated effect of mutation-positive status, −0.0266, with standard error of 0.0124; P = .04), and in mutation carriers with increasing estimated years to symptom onset (EYO) (estimated effect of EYO, −0.0015, with standard error of 0.0006; P = .01), raising the hypothesis that these changes may potentially be involved in early pathogenesis of ADAD. For example, by using the statistical model in Equation (E2) (online), for a cognitively normal male mutation carrier with average amyloid burden (standardized uptake value ratio, 1.5), apolipoprotein allele E4 negativity, 15 years of education, normalized intracranial white matter volume of 30%, and Mini-Mental State Examination score of 29, the estimated yearly decline in global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network is 0.0015, which is a decrease in the global efficiency of approximately 1%. For this individual, at an EYO of −20 years the global efficiency in the frontoparietal control network would be 0.137, which would drop to 0.107 at an EYO of 0 years, a decline of 22%.

Of note, individuals with ADAD mutation demonstrate early amyloid deposition in the parietal lobes, specifically the precuneus (20), and the frontoparietal control network includes the superior aspect of the precuneus. In this analysis, only the structural connectivity, and not amyloid pathology, was related to EYO, perhaps due to the small sample size. This raises the possibility that structural connectivity may be a measure of resilience of the brain to pathologic changes, as the presence of pathologic abnormalities (eg, amyloid) may be considered necessary, but not sufficient, for cognitive decline. In addition, there was no significant association between internetwork connectivity and EYO nor between other networks.

The frontoparietal control network contains a hub in the left frontal cortex in which functional connectivity has been shown to be potentially critical to the resilience of brain networks to neuropathologic changes (21). The results of our study support the importance of the structural integrity of this network in maintaining efficient brain function in the face of amyloid pathology. The correlation network analysis demonstrated that, for mutation carriers, structural connectivity metrics, amyloid burden, cognition, and EYO were relatively more strongly correlated than for noncarriers, which suggests the potential interconnectedness of structural connectivity to disease progression in preclinical ADAD.

There is increasing recognition of the heterogeneity of AD—both dominantly inherited and especially sporadic forms—regarding clinical presentation, neuroimaging, and pathology. Strengths of the DIAN data for analysis of preclinical AD are the reliable predictability of age at onset for mutation carriers based on parental age at onset and mutation type (22), which allows for analysis of preclinical disease progression, and the young study sample and controls who do not have substantial age-related vascular changes in the white matter. In our study of ADAD, the frontoparietal control network demonstrated significant changes in connectivity as mutation carriers got closer to the expected age of symptom onset. Insights into changes in white matter structural connectivity could provide a new target for diagnosis of AD that has historically received little attention. Indeed, most prior research has aimed at identifying changes in the gray matter, particularly with respect to amyloid burden. Previous studies of ADAD in participants in DIAN have demonstrated that abnormal levels of amyloid were detected in the cortex of mutation carriers 15 years in advance of expected onset of clinical symptoms (11,19,20). Moreover, studies in the same population using resting-state functional MRI have demonstrated that functional disruption of the default mode network begins before clinically evident symptoms in mutation carriers and worsens with increasing impairment (23–25). Studies have demonstrated that white matter structural connectivity is affected by AD-related pathology, namely amyloid, and may mediate changes in other markers of AD (4,26,27).

Limitations of our study include a relatively small sample size, cross-sectional nature, pooling of several types of genetic mutations, lack of data on tau deposition, lack of clinical outcomes, and multiplicity of comparisons. Of note, there was one mutation carrier with a very high amyloid SUVr value that influenced some of the correlations. This does not appear to be a measurement error; thus, we did not exclude the mutation carrier. As a test, this individual carrier was removed from our analysis, and the overall statistical significance of our results did not substantially change. In addition, the exploratory and cross-sectional nature of the study would require larger longitudinal data sets to allow for verification of the findings. Another limitation is that ADAD does not represent the more common late-onset AD model in important aspects, such as the high prevalence of common age-related comorbidities. Additionally, the use of fractional anisotropy for weighting the network metrics can be affected by white matter hyperintensities, and a prior study with the DIAN cohort has demonstrated increase in white matter hyperintensity volume in mutation carriers approximately 6 years before symptom onset (28). Hence, our findings must be interpreted within this context, especially as preliminary and susceptible to outliers.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a relationship between mutation status and lower frontoparietal control network connectivity. In addition, mutation carriers showed worsened frontoparietal control network changes as they approached the expected age for the onset of autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease symptoms. These findings seem to be linearly correlated with amyloid burden, though they appear in the context of elevated amyloid. Future studies with longitudinal clinical MRI connectivity data and PET markers of molecular pathology may help further elucidate the role of white matter structural connectivity in cognitive decline and as a potential biologic marker in patients at genetic risk for Alzheimer disease.

Supplementary Material

Key Results.

In an exploratory analysis of a prospective trial of 30 mutation carriers and 38 noncarriers of autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network cohort who underwent diffusion tensor MRI, the structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network was lower in mutation carriers of ADAD compared with noncarriers (estimated effect of mutation-positive status, −0.0266; P = .04).

Among mutation carriers, the estimated number of years to symptom onset was associated with white matter structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network (estimated effect of years to symptom onset, −0.0015; P = .01).

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge the altruism of the participants and their families and contributions of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network research and support staff at each of the participating sites for their contributions to this study.

Data collection and sharing for this project was supported by the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (U19AG032438) funded by the National Institute on Aging, with partial support by the Research and Development Grants for Dementia from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- ADAD

autosomal dominant AD

- DIAN

Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- EYO

estimated years to symptom onset

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

- SUVr

standardized uptake value ratio

Footnotes

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: J.W.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. P.M.D. disclosed compensation received for board membership at AHEL; received advisor fees from Neuroglee, Transposon Therapeutics, VitaKey, and Verily Life Sciences; received grants from Lilly, Avid Medical, Avanir, and Bausch; has patents related to Alzheimer disease diagnosis and therapy; has stock or stock options in uMETHOD, Evidation, Transposon Therapeutics, and Advera Health. D.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. T.B. disclosed support from Biogen for travel to meetings for the study; received consulting fees from Biogen; has performed unpaid consulting for Eisai, Siemens, and ADMdx; received payment for lectures and the development of educational presentations from Biogen. J.R.P. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Clinical trial registration no. NCT00869817

Data sharing: Data analyzed during the study were provided by a third party. Requests for data should be directed to the provider indicated in the Acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey W. Prescott, Department of Radiology, The MetroHealth System, 2500 MetroHealth Dr, Cleveland, OH 44109; Departments of Radiology and Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

P. Murali Doraiswamy, Departments of Radiology and Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Dragan Gamberger, Ruđer Bošković Institute, Zagreb, Croatia.

Tammie Benzinger, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Mo.

Jeffrey R. Petrella, Departments of Radiology and Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

References

- 1.Hohman TJ, McLaren DG, Mormino EC, et al. Asymptomatic Alzheimer disease: defining resilience. Neurology 2016;87(23):2443–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Vemuri P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 2018;90(15):695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold SE, Louneva N, Cao K, et al. Cellular, synaptic, and biochemical features of resilient cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34(1):157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott JW, Guidon A, Doraiswamy PM, et al. The Alzheimer structural connectome: changes in cortical network topology with increased amyloid plaque burden. Radiology 2014;273(1):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippi M, Agosta F. Structural and functional network connectivity breakdown in Alzheimer’s disease studied with magnetic resonance imaging techniques. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;24(3):455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews PM, Filippini N, Douaud G. Brain structural and functional connectivity and the progression of neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2013;33(Suppl 1):S163–S172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smeets D, de Barros NP, Billiet T, et al. Analysis of structural and functional connectivity MRI biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2020;16(S4):e042891. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moulder KL, Snider BJ, Mills SL, et al. Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network: facilitating research and clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther 2013;5(5):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caballero MÁA, Song Z, Rubinski A, et al. Age-dependent amyloid deposition is associated with white matter alterations in cognitively normal adults during the adult life span. Alzheimers Dement 2020;16(4):651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sánchez-Valle R, Monté GC, Sala-Llonch R, et al. White matter abnormalities track disease progression in PSEN1 autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;51(3):827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367(9):795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC, Aisen PS, Bateman RJ, et al. Developing an international network for Alzheimer research: The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clin Investig (Lond) 2012;2(10):975–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack CR Jr, Bernstein MA, Borowski BJ, et al. Update on the magnetic resonance imaging core of the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Dement 2010;6(3):212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002;33(3):341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 2011;106(3):1125–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 2010;52(3):1059–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreotti J, Jann K, Melie-Garcia L, Giezendanner S, Dierks T, Federspiel A. Repeatability analysis of global and local metrics of brain structural networks. Brain Connect 2014;4(3):203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messaritaki E, Dimitriadis SI, Jones DK. Optimization of graph construction can significantly increase the power of structural brain network studies. Neuroimage 2019;199:495–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benzinger TLS, Blazey T, Jack CR Jr, et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110(47):E4502–E4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon BA, Blazey TM, Su Y, et al. Spatial patterns of neuroimaging biomarker change in individuals from families with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol 2018;17(3):241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franzmeier N, Düzel E, Jessen F, et al. Left frontal hub connectivity delays cognitive impairment in autosomal-dominant and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018;141(4):1186–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 2014;83(3):253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chhatwal JP, Schultz AP, Johnson K, et al. Impaired default network functional connectivity in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2013;81(8):736–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas JB, Brier MR, Bateman RJ, et al. Functional connectivity in autosomal dominant and late-onset Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2014;71(9):1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith R, Strain J, Tanenbaum A, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity disruption as a pathological biomarker in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Brain Connect 2021;11(3):239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daianu M, Jahanshad N, Nir TM, et al. Rich club analysis in the Alzheimer’s disease connectome reveals a relatively undisturbed structural core network. Hum Brain Mapp 2015;36(8):3087–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandya S, Kuceyeski A, Raj A; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The brain’s structural connectome mediates the relationship between regional neuroimaging biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55(4):1639–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Viqar F, Zimmerman ME, et al. White matter hyperintensities are a core feature of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Ann Neurol 2016;79(6):929–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.