Introduction

Caring for dying children is among the most poignant aspects of nursing care. Previous research has elucidated parents’ priorities as they navigate the end of their child’s life, including their child’s comfort, family presence, and resolution of viable treatment options (Butler et al., 2018; Falkenburg et al., 2016; McGraw et al., 2012; Meert et al., 2009; Meyer et al., 2002). Most child deaths occur in paediatric intensive care units (PICU) following a planned withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (LST; Meert et al., 2015; Trowbridge et al., 2018). The evolution of parents’ perceptions of end-of-life (EOL) needs for their child and themselves remains understudied. Much of the existing literature exploring parental experiences during the death of their child in the intensive care unit focuses on acute, short-term grief perspectives (i.e. first months or years), leaving less known about the connection between nursing care during withdrawal of a child’s LST and long-term parental bereavement many years after a child dies.

Questions remain about how to holistically care for children and their parents during withdrawal of LST. PICU characteristics, including instrumentation, monitoring, and sedation shift the parental role from primary caregiver to clinical teammate under particularly stressful circumstances (Balluffi et al., 2004; Foster et al., 2016, Macdonald et al., 2012). Few studies have examined how the PICU environment impacts end-of-life (EOL) experiences (Butler et al., 2018; Falkenburg et al., 2016; Meert et al., 2008), warranting study of how parents integrate recollections of these circumstances into their lifelong grief experience. Aspects of the EOL experience that persist in parents’ memories shape their lifelong bereavement, requiring careful attention from the clinical team. Research that examines the relationship between PICU EOL care and parents’ longstanding grief is crucial to providing the best possible family-centred care during a time of profound loss.

Theoretical and Conceptual Guidance

Though PICU staff may help facilitate parents’ transition into the grieving process, the death of a child and subsequent bereavement process are largely intrapersonal experiences. We therefore grounded our study in frameworks derived from social constructionism. Specifically, meaning making theory suggests that the circumstances of death shape the grief experience, underlying the reconstruction of a new life narrative following loss (Neimeyer, 2001; Wheeler, 2001). This theoretical lens offers a framework to link the moments around a child’s death in the critical care context to ongoing parental bereavement. The Good Death in the PICU conceptual model operationalises this lens for the PICU setting (Broden et al., 2020). The model includes clinical factors (i.e., pain and device management), situational factors (i.e., environmental considerations), and emotional/spiritual factors. The uniquely connected relationship between parent and child guides paediatric nursing care through the end of a child’s life.

Methods

Objectives

This qualitative study explored the relationship between EOL circumstances and long-term parental grief by examining parents’ perceptions of needs during withdrawal of LST and in the years following. We utilised a qualitative descriptive approach with content analysis to generate close descriptions of bereaved parents’ retrospectively defined EOL needs, with minimal researcher interpretation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2010).

Setting

This study is part of a mixed methods study that integrated dying children’s clinical presentation with parent perceived needs during and following the withdrawal of LST in the PICU. Details of the quantitative study, which examined associations between patient characteristics and nursing care requirements for children who died in the PICU, are published elsewhere (Broden et al., 2022). Quantitative data and the qualitative parent sample were identified from the RESTORE clinical trial, which includes quantitative data from 2009–2013 from 31 PICUs across the United States (Curley et al., 2015). RESTORE evaluated the impact of a nurse-implemented, goal-directed sedation weaning protocol versus usual, physician-led sedation management on duration of mechanical ventilation. Children between 2 weeks and 17 years old who were intubated and mechanically ventilated for acute lung disease were eligible for RESTORE.

Ethical Considerations

RESTORE and this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania (#808830). Parents provided additional verbal informed consent to participate in the telephone interview and were sent a gift card for their time. An IRB-approved distress protocol was available for significant emotional reactions.

The authors were attentive to parents’ psychological responses to study processes. The interview guide was structured to help guide parents gently in and out of a highly emotional state, and the phone conversation was not concluded until the first author felt that the parent was ready to hang up. At the end of the conversation, the first author reminded parents that they could contact her via email, text message, or phone call at any point with questions or concerns. Lastly, a handwritten card was sent to each parent participant within one week of the interview.

Participants

Of the 2449 children included in RESTORE, 111 died following withdrawal of LST. Parents of children who died following withdrawal of LST were eligible to participate in this study. Parents were excluded if they did not consent for RESTORE follow-up (n=6), were unable to consent to the current interview (i.e., non-English speaking, etc.; n=13), or if the child died outside the PICU (n=2). We were unable to contact 50 parents due to missing contact information (i.e., not retained by RESTORE study personnel due to death of patient or length of follow up; n=21), or operational issues at the local RESTORE site (i.e., lack of staff to support study procedures or IRB review; n = 29). Among the remaining 40 parents, we recruited with a goal of maximizing variation along key variables, including location, child age, demographics, and illness trajectory (cancer, acute illness, complex chronic condition).

RESTORE site investigators sent a personalised invitation and opt-out card to eligible parents. If a parent returned the opt-out card, they were not contacted further. Otherwise, the first author (E.B.) contacted parents to explain the study, confirm eligibility, obtain consent, update demographic information, and schedule an interview. Potential participants were classified as lost to follow up if there was no answer to up to three phone call and text message attempts (Currie et al., 2016). Data collection was temporarily postponed as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the United States. We reworded recruitment protocols to address these unprecedented circumstances.

Data Collection

The first author (E.B.) conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with individual parents from December 2019 to October 2020. Interview questions were derived from the domains of The Good Death in the PICU conceptual model (Broden et al., 2020), and prompted parents to retrospectively describe EOL needs for their child and themselves and reflect on how their child’s EOL circumstances influenced their current grief. Questions and probes were structured to correspond with variables included in the quantitative arm (Creswell, 2018), including patterns of pain, sedation, and critical care requirements (Broden et al., 2021). We added a question to assess whether the COVID-19 pandemic impacted parents’ experiences and took care to ensure the interview did not add burden to an already stressful time. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed securely. Parents were assigned pseudonyms to maintain privacy and anonymity. Field notes were recorded immediately after each interview. The data were managed using Microsoft Word, Excel, and NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018).

Constructivist meaning making theory maintains that perceptions of EOL circumstances shape individuals’ grief following profound loss (Neimeyer, 2001; Neimeyer et al., 2014); thus, during the interview, participants’ responses were reviewed to ensure accuracy in understanding. The first author moved between the processes of data collection and analysis while assessing for saturation, noting when patterns of developing categories became apparent across transcripts and in one confirmatory interview (Hennink et al., 2016; Morse, 2015a).

Data Analysis

We utilised directed content analysis to validate and expand existing knowledge of parental grief through a combination of inductive and deductive techniques (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The first author read each transcript for an initial impression of parent defined EOL needs, generating in vivo codes directly from their words (Streubert & Carpenter, 2007). In vivo codes were defined and compiled into broader codes that were present across transcripts. At this point, the first author compared codes against concepts from The Good Death in the PICU framework (Broden et al., 2020). Codes that did not correspond with the conceptual model were characterised as subcategories or new categories that extended the framework (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). During content analysis, the first author also examined the ways parents’ descriptions of EOL care shaped their current grief by coding for time (i.e., around the death, looking back), emotional tones (i.e., crying), and grief responses (i.e., raw grief, healing process).

The first author compiled a codebook to define each code and category and identify parameters for use. The research team reviewed the codebook, discussing discrepancies until consensus. The first author then re-coded all transcripts using the final codebook to confirm that definitions matched parents’ descriptions and compiled illustrative quotes to uphold credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The study team reviewed an audit trail of field notes, memos, transcripts, and narrative case summaries to ensure transparency and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Morse, 2015b; Streubert & Carpenter, 2007).

Findings

Out of 40 eligible parents with updated contact information, three parents opted out (7.5%), 8 (20%) parents declined, and 22 (52.5%) parents were lost to follow up. A total of 8 (20%) parents of 8 children completed telephone interviews. All participants were female. The deceased children’s ages varied from less than 1 to 17 years old. Half died following complex chronic conditions, and half following cancer. Time since the child’s death ranged from 7 to 11 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Parent Characteristics (n=8) | Child Characteristics (n=8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yrs); range | 29 – 73 | Age (yrs); range | <1 – 17 |

| Female | 8 (100) | Female | 3 (38) |

| Race | |||

| White | 7 (88) | White | 7 (88) |

| Black | 1 (12) | Black | 1 (12) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 8 (100) | Non-Hispanic | 8 (100) |

| Hispanic | 0 | Hispanic | 0 |

| Years since death; range | 7–11 | PCPC/POPCa; range | 1/1–4/4 |

| Interview (min); range | 36–76 | Complex chronic illness | 4 (50) |

| Married/Partnered | 7 (88) | Cancer | 4 (50) |

| Surviving sibling | 8 (100) | LOSb (days); range | 11–35 |

All data are n (%) unless otherwise noted

Baseline functional status as measured by Paediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) and Paediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) at baseline

Length of stay

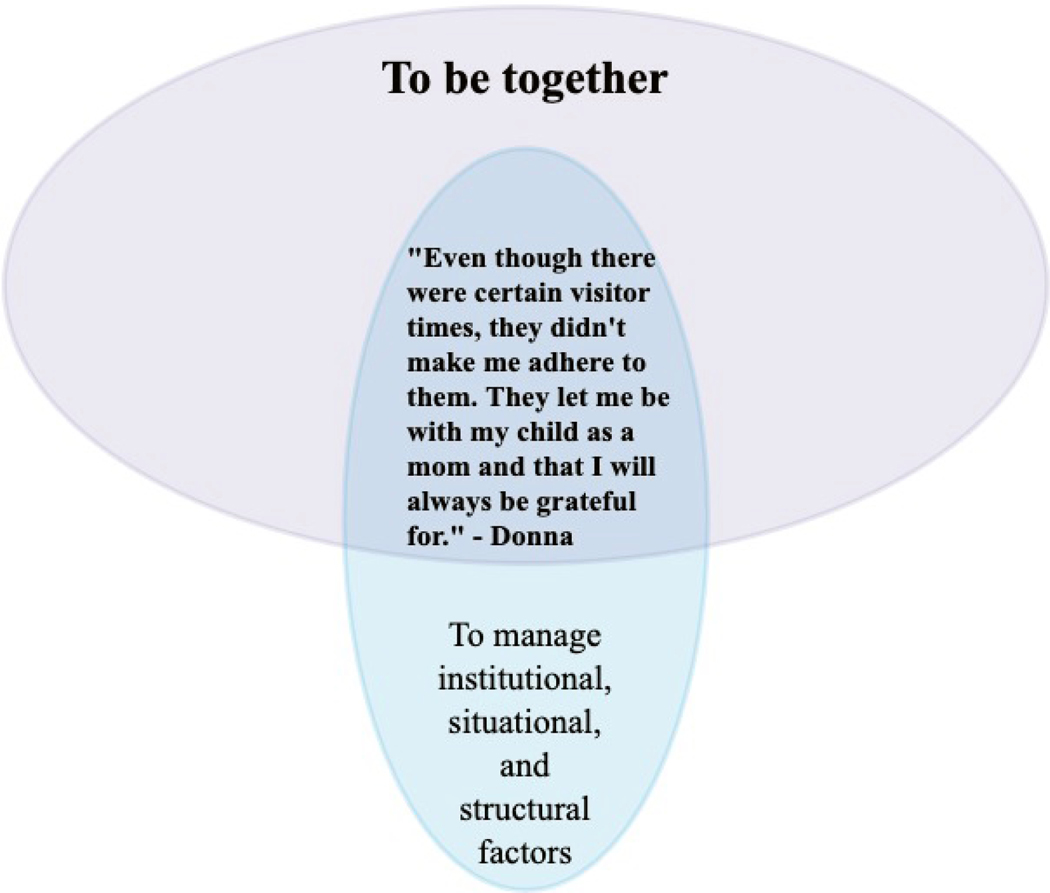

Shifting and Intersecting Domains of Needs

Parents’ stories centred around four shifting and intersecting needs: (1) To be together, (2) To make sense of the child’s evolving clinical care, (3) To manage institutional, situational, and structural factors, and (4) To navigate an array of emotions in a sterile context. Parent’s memories frequently consisted of multiple needs simultaneously, demonstrating intersections when different needs co-occurred to intensify one another (Figure 1). Table 2 presents detailed examples of parents’ quotes paired with nurses’ actions. Parents’ priorities shifted throughout the story of the child’s death, including at admission to the PICU, the hospitalization, the death itself, and their transition into the grief process.

Figure 1. Venn Diagram of Intersecting Needs.

Figure 1 presents a Venn Diagram that depicts parents’ intersecting needs; with the primary need, To be together, largest and at the center as the most prominent.

Table 2.

Codebook with definitions and exemplary quotes

| Label | Description | Sample Quotes | Nursing Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| (sub-codes) | |||

| To be together (being together with the child, parent-child relationship, knowing when and how to facilitate presence) |

Captures parents’ interactions with their child throughout the illness trajectory, death, and grief process. Includes descriptions of how parents partnered with the clinical team in trying to make the best possible experience for the child and family; particularly when clinicians seemed to intuitively understand when and how to create opportunities meaningful connections with the child. | “I stayed there every day. I never went

home. I stayed with her. If she was there, I was there. I would sleep on

that God-awful couch right next to her and I hold her hand and I'd sing

to her.” (Kim) “And when you think back, you're like, why did I go take a shower when I coulda spent that time with him?” (Nancy) |

“He sat in the rocking chair. The nurse

put her in his arms and he held her and rocked her. And her lullabies

were playing in the background. Then it was my turn and I held her and

all of my family, her sisters, her aunt and everybody's hands were on

her.” (Theresa, describing the time around withdrawal of

LST) “The nurses up there, they were great. They know when to be with you and when not to.” (Nancy, describing interactions with the nurses during the last days of her son’s life) |

| To make sense of the child’s evolving

clinical care (witnessing complex and chaotic clinical treatments, bearing witness to suffering, developing ongoing uncertainty, hoping for symbols of recovery, understanding symbols of deterioration, monitoring symptoms, knowing they tried everything) |

Captures the multitude of ways in which parents monitored and attempted to understand their child’s medical treatments throughout the illness and end-of life-trajectory. Includes witnessing different complex medical requirements, the especially challenging act of bearing witness to suffering, and developing ongoing uncertainty about treatments, options, and actions around the death. Also includes parents’ assessments of memorable symptoms, specific instances of deterioration and/or recovery that represented important symbols of their child’s well-being and prognosis, and the eventual, often retrospective, understanding that despite “trying everything”, the child would die, and their memories of the moments around the death | “She was in so much pain. Her skin was

so bad, and they would have to change her bandages [crying]. It looked

like it had been burned.... That’s the nightmares that I

struggled with for years.” (Laurie, describing dressing

changes in the days leading up to her daughter’s

death) “I have since forgiven myself, but it comes with a lifetime of questions. Had he not been given so many meds at the end, would he have been able to breathe on his own?” (Mary) |

“When they would touch her, the nurses

or doctors, she would just scream in pain. I would beg them; let's do it

a different way. It became where they had to give her something. I think

what had to happen was they sedated her. So she wouldn't feel the pain

anymore” (Laurie, describing how the nurses kept her

daughter comfortable during dressing changes)

“The [nurses] gave him some morphine or something. I can't remember, but I know I hold him until he took his last breath [crying] and that was it.” (Trish) |

| To manage institutional, situational, and

structural factors (rules and regulations, dealing with the structure of the PICU, creating a sacred space, making final memories, separating from the child) |

Identifies parents’ perceptions of how they (and/or the clinical team) navigated PICU and hospital characteristics, such as rules, structures, processes, resources, etc. that influenced the family's experience of care. May include parents’ actions such as dealing with PICU policies; creating a space in which to honor the child’s life and death and make final memories, and finally, the act of separating from the deceased child. | “The bed wouldn't fit through the door.

So, my husband and my son had to pick him up off of the bed awkwardly

with all of the equipment he was attached to, then onto the bed with

me.” (Nicole, describing moving rooms prior to withdrawal

of LST) “She was sitting in my lap and we were singing . … Then her oxygen just kept dropping [crying], then in comes the bunch of doctors and they cleared the room. She looked scared. [crying]” (Kim, describing her daughter’s emergent intubation prior to withdrawal of LST) |

“So, um, the [nurses] were, they were

very caring and they gave us as much time as what we needed. It wasn't

a, you know, hurry up and, and leave. It was 'take as much time as you

need'.” (Theresa, describing the time after her son

died) “Um, the [nurses] asked me if I wanted to help bath him. I couldn't [crying]… And I laid down next to him a couple times, but I just couldn't [bathe him]” (Mary, describing the time after her son died) |

| To navigate an array of emotions in a sterile

context (specific emotional responses; anger, sadness, isolation, numbness, etc.) |

Captures diverse and profound feelings parents experienced and the ways in which they dealt with these responses in the unfamiliar and difficult context of their child’s death in the PICU. Includes the extent to which their feelings were supported or not, by themselves and by others (including loved ones, clinicians, and supportive care providers). Includes stress, regret, anger, fear, shock, numbness, isolation, gratitude, humor, hope, etc. | “I knew all the best places to go take

a nap. That’s the bathrooms that were actually clean. You know,

all, all of that. Um, the good places that you could go and cry where no

one would bother you.” (Nicole) “You know, it was just like, I'm not turning off the f'ing TV. So that was, it was just really real weird.” (Nancy, referring to turning off her son’s ventilator). |

“When he passed, she [nurse] cried, she

cried. I cried, she holded me, it was enough” (Trish)

“The staff up there in the ICU was really helpful. They were supportive… They always made sure that we had everything we needed. And if we were there for too long of a time, they always said, you know, you need to go take a break. Or even if it was just out into the hallway, go call somebody, go whatever.” (Theresa) |

(1). The need To be together

Parents’ relationships and interactions with their child, clinicians, and loved ones constituted an important domain of EOL needs, especially around the child’s death. Parents’ need to be physically and emotionally close with their child was an particularly meaningful part of their stories.

“I don’t want to say it was the best time of my life because it certainly wasn’t, but if he had to leave this world, [I knew] I had given myself 100% to him.” (Mary)

Being close to the child was a way of being wholly, uninterruptedly together through the child’s death. This togetherness remained a source of comfort in parents’ grief, even years later.

Parents’ intense need to be with the child shaped their stories of their child’s death and often intersected with other domains of EOL needs (Figures 1–5). At times, parents recalled partnering with nurses to overcome situational and clinical barriers that presented challenges to their relational needs:

“It was important for the nurses to have compassion and the doctors that, yeah, there’s rules and he’s contagious, but I have to be his mom. I have to feel his body next to mine…You know, that skin touch, let him know I’m here.” (Donna)

Parent’s relational needs “to feel [the child’s] body” were amplified or inhibited by situational “rules” and clinical considerations (“he’s contagious”). These intersections between necessary processes (such as visitation policies and life-sustaining medical devices) and parents’ need for closeness constituted a tension that seared specific moments into parents’ constructed grief narratives, even years later (Figures 1–5). Parents seemed to fall along a spectrum from solace to remorse in their longstanding grief depending on the extent that they were able to be close with the dying child.

(2). The need To make sense of the child’s evolving clinical care

Parents recalled the complicated task of trying to comprehend their child’s medical treatments as the clinical course unfolded in the PICU, particularly early in the illness timeline. Sometimes the child’s medical life-sustaining needs conflicted with the family’s need for physical and emotional closeness. Without assistance from clinical staff, these barriers became insurmountable (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intersection of Relational (1) and Clinical (2) Needs.

Figure 2 demonstrates an intersection, when the child’s clinical needs (“breathing things” and “too much stuff”) acted as a barrier to being physically close with the child.

Parents identified indicators of their child’s recovery and decline and depended on their intuition, clinical experience (or lack thereof), and knowledge of their child to identify and define these indicators. A mother who had previous health care experience as a paramedic said, “When the fluids coming out of her were not clear and they started turning dark. I knew that wasn’t good.” (Theresa). Some parents recognised these cues in retrospect, reporting that in the moment, they did not explicitly acknowledge that they were aware of the possibility of death.

Increases in the child’s pain sometimes precipitated this mortality awareness and shifted parents’ priorities from cure- to comfort-focused. Bearing witness to their dying child’s suffering remained especially difficult for parents to recount.

“I felt like he was hurting, hurting, and I couldn’t take it and bear it. I didn’t want my baby to pass, but I don’t want him suffering either.” (Trish)

It was challenging for parents to experience their child’s suffering both in the moments around death and in their recounted stories, as it represented an existential boundary between thinking their child would survive and confronting the reality that they may die.

Parents ruminated on questions, self-blame, and doubt about the clinical circumstances around the death (Table 2). Uncertainty about treatment options constituted a source of ongoing distress. Some parents still questioned the withdrawal process itself.

“She was telling the nurse practitioner to push the morphine. And that’s why I felt like they put him down like a dog. Morphine is going to make you stop breathing. I wasn’t naive to that” (Nicole).

The balance of pain management and respiratory suppression was an ongoing source of uncertainty in parents’ grieving process. Parents were “at their mercy”, forced to put their trust in the clinical team to care for their child in high-stakes circumstances. Connections with the clinical team exacerbated or assuaged parents’ doubts and worries, leaving them with more or less uncertainty in their long-term grief.

(3). The need To manage institutional, situational, and structural factors

The PICU environment created concerns for parents throughout the end of their child’s life. Policies (e.g., visitation rules), processes (e.g., rounds, invasive procedures) and the physical set-up (e.g., open or private rooms) enabled and/or inhibited being together with the child. Situational factors sometimes complicated the story of the death. Figure 3 illustrates when situational and clinical changes inhibited making final memories with the child, which sharpened the transition into grief. Parents memories of institutional, situational, and structural details suggest these factors shaped their bereavement experience in meaningful ways.

Figure 3. Intersection of Relational (1), Clinical (2), and Situational (3) Needs.

Figure 3 shows how situational factors (i.e., the transfer between units) and clinical needs (i.e., emergent intubation and transfer to the PICU) inhibited this mother’s ability to be with her child through the transition to EOL

PICU nurses managed the environment around the family. Parents were grateful for nurses who let them be near their children, even when visitation policies did not (Figure 4). During withdrawal of LST, one mother “remember[ed] the paediatric intensive care nurse being there and just kind of shutting everything off and giving us our privacy” (Laurie). Another recounted, “the family filtered in, one by one, and they got us chairs, thank goodness, for all the crowd of us” (Nicole). Parents needed supported privacy, uninterrupted time with the child, and fulfilled instrumental needs.

Figure 4. Intersection of Relational (1) and Situational (3) Needs.

Figure 4 shows how flexible application of visitation policies could facilitate the need to be with the child.

Physically separating from the child after they had died was especially consequential, spanning both situational needs and the need to be together with the child. Many parents did not leave until the child’s body was removed from the PICU, describing their departure from their child as a monumental, yet mundane task that remained an uncomfortable memory many years later.

“I regret at the end that I just left, you know? Pulled out of the garage at the hospital and left my dead son there. I think it was probably best because shit, who wants to leave your kid in the basement of a freaking hospital.” (Nancy)

Leaving the deceased child was tremendously difficult for parents and constituted an important moment that straddled end-of-life and grief, representing the vast shift from parenting an ill child to grieving their death.

(4). The need To navigate an array of emotions in a sterile context

Parents described experiencing a range of emotions, including frustration, intense sadness, and guilt. Some parents felt a sense of release after the child died. Fear and panic were not uncommon throughout the clinical course and in the moments around death. Parents recalled how difficult it was to cope with diverse emotions while their child was dying in the PICU. Emotional needs stemmed from the ways parents required support in experiencing emotions in the unforgiving PICU environment, which one parent described as “cold, uninformative unless you forced” (Mary). One parent felt as though her family’s emotional responses were on display: “it was awful because people were staring … because he looked terrible” (Nicole).

Parents remembered clinicians’ responses to the child’s death that validated the depth of their connection with the child.

“That sweet doctor from upstairs was bawling his eyes out. I thought, [my son] always touched everyone. He was special and they all knew it” (Nicole).

Some parents recalled actions that eroded a fragile emotional situation, “…the nurses are walking in and out like, ‘Hey, get the hell out. We need a bed” (Nancy). These interactions honoured and/or minimised the sanctity of the child’s life and death and interfered with or supported parents’ need to be together through the end of the child’s life.

Many parents reflected on a sense of numbness in the immediate moments after the death: “I was numb, I was so numb. I couldn’t cry. I couldn’t think. I couldn’t do anything” (Kim). This often coincided with a raw sense of grief that was especially difficult to navigate:

“I went to my locker, got my stuff. Had to get down on my knees ‘cause you know, how you’re weak … I don’t even think I could open the doors from his room.” (Nancy)

In this phase, situational and emotional needs overlapped. Parents needed help with instrumental tasks (i.e., gathering personal belongings), for supported privacy, and time with loved ones.

Situational constraints required consideration to minimise the PICU environment’s intrusion upon parents’ emotional responses to their final moments with their dying child. One mother recalled how nurses created a sacred space, pulling the curtains amidst the other PICU beds, allowing her a place to grieve her last moments with her son without disruption (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Intersection of Relational (1), Situational (3), and Emotional (4) Needs.

Figure 5 shows how nurses tended to the structural elements of the PICU to give space for the family’s emotional responses while making final memories with their dying child.

In recounting their stories, parents described manoeuvring through profound emotions during complex clinical scenarios in an unfamiliar situational context while grasping at liminal opportunities to connect with their dying child. Parents prioritised clinical needs prior to the death itself, which centred on situational, emotional, and relational needs, especially to be with their child. Parents’ recollections demonstrated how their needs intersected to amplify, inhibit, and/or complicate one another. Vacillating between shifting and intersecting needs during their child’s dying process had lasting implications for parents’ grief responses. The degree to which parents’ needs were identified and fulfilled, or left unresolved, appeared to influence their lasting bereavement experience.

Discussion

This study uncovered that parents’ relational, clinical, situational, and emotional needs shifted and intersected throughout their child’s illness and end-of-life journey. The need to be with the child was of primary importance. Bearing witness to suffering and developing uncertainty about EOL circumstances remained sources of anguish in parents’ grief. Fulfilling, or not fulfilling, intersecting needs therefore has implications on parents’ short and long-term responses throughout the course of end-of-life care and parents’ grieving processes.

Many of our findings are consistent with the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that guided this inquiry. The details of their child’s death did not fade in parents’ recollections; consistent with the constructivist foundation of this study (Neimeyer, 2001). Parents’ stories substantiated the clinical, situational, and emotional components of The Good Death in the PICU conceptual model (Broden et al., 2020); demonstrating how these domains manifest in the story of a child’s death. Important EOL considerations illuminated by previous research, such as parent-child closeness and relationships with clinicians (Butler et al., 2018; Falkenburg et al., 2016; McGraw et al., 2012; Meert et al., 2009; Meyer et al., 2002), were apparent in the category To be together. These corroborated findings support expansion of The Good Death in the PICU model to encompass relational needs more explicitly.

Similar to other studies, parents in this analysis reflected on their time together with their child as a source of solace in their grief (Falkenburg et al., 2018, 2016). This study contributes a more dynamic perspective by illuminating that parents’ need to be with their child shifted in priority throughout the illness and EOL timeline and intersected with situational and clinical domains of needs. PICU nurses may help attend to future challenges in parents’ grieving process by focusing EOL care on these intersections. Prioritizing togetherness amidst medical equipment and parental role alteration in the ICU environment can meet parents’ needs across mutliple domains to help parents construct an EOL and grief narrative that is consistent with their embodied role as a parent.

Recent research has explored the impact of the PICU environment on family’s experiences in critical care, including the unwelcome shift in parental role (Balluffi et al., 2004; Foster et al., 2016, Macdonald et al., 2012). Our findings add nuanced understandings from bereaved parents of how structural and situational factors influence their EOL and grief experience; particularly how these aspects facilitated or inhibited parent-child bonding. Parents and/or nurses had to work carefully to overcome and/or mitigate the impact of PICU policies and processes such as interdisciplinary rounds, visitation policies, and the physical environment (open bedspaces, private rooms). A deep sense of situational awareness is thus necessary to facilitating optimal EOL care in the PICU and should be a component of EOL quality metrics and education (Ananth et al., 2021; Mack et al., 2005; Sellers et al., 2015).

Despite carrying the burden of their child’s EOL suffering, some parents expressed worries about pain medication administration once life support was withdrawn. Dual effect, the dichotomy of medically managing EOL symptoms such as pain and rattled breathing while potentially hastening death, is well-studied amongst clinicians (Burns et al., 2000; Garten et al., 2011; Henderson et al., 2017; Morrison & Kang, 2014; Van Loenhout et al., 2015). Parents, too, may be aware of dual-effect and require specific preparation and communication about this aspect of EOL symptom management during discussions planning the withdrawal of LST. Parents’ reflections also indicate that managing dying children’s pain may require a broader and more relational approach that attends to the emotional implications of EOL suffering in addition to purely medical symptom management.

Parent’s longstanding grief responses were influenced by uncertainty stemming from their child’s death circumstances and their sense of responsibility to be a “good parent” who protects their child from harm (Hinds et al., 2009; October et al., 2014). Many parents ruminated on “a lifetime of questions” about clinical treatments, the child’s suffering, and an insidious sense of self-blame and guilt. Uncertainty and guilt adversely affect the bereavement process (Boelen et al., 2016; Stroebe et al., 2014). A planned withdrawal of LST presents the opportunity to employ an anticipatory framework and prospectively attend to sources of uncertainty. Parents in this study identified specific indicators, such as the child’s suffering, ability to interact, or their dependence on devices, that helped them understand how sick, and possibly how close to death, the child was. Clinicians can help parents identify these symbols in the moment, by soliciting their perceptions of how the child looks and acts to carefully support parents’ developing mortality awareness.

The intersectional nature of parents’ EOL needs presents important avenues to strengthen nursing education and practice. Nurse training should incorporate how to facilitate parent-child closeness within situational and clinical constraints, such as by removing unnecessary devices if not painful, providing opportunities for physical touch and memory-making, and arranging equipment to promote proximity (Cole & Foito, 2019; O’Shea et al., 2015). Prioritizing parents’ deep need to be with their child and providing supported privacy for parents to navigate emotions may be beneficial. Staffing models and clinical assignments that account for shifting and intersecting needs beyond the purely clinical can also improve EOL care in the PICU. Ideally, nurses caring for dying children should not have multiple patient assignments. Allocating additional interdisciplinary providers and support staff (i.e., social workers, child life specialists, respiratory therapists, nursing assistants) to help manage clinical, emotional, and situational considerations may also prove helpful (Lang et al., 2004; Rolnick et al., 2020).

Our findings indicate that future research and approaches to care should account for intersecting, rather than disparate EOL needs. Better understanding of PICU nurses’ in-the-moment symptom, communication, and emotional support could provide the foundation to build care models that support dying children and their parents’ shifting and intersecting needs (i.e., Sisk et al., 2020; VitalTalk, n.d.). Research examining parents’ and clinicians’ collaboration to meet arising relational, situational, clinical, and emotional needs could identify strategies to support these needs and tend to uncertainty in the moments around death, facilitating an adaptive grief response.

Limitations

This study advances the science of caring for children at EOL yet is limited in ways that present opportunities for additional research. Retrospective designs are typically limited by recall bias; however, in this study, retrospection provided important insight into parents’ persistent, self-identified needs in their long-term grief. Given that the existing literature about PICU EOL has often focused on parent’s short-term experiences, the long-term perspectives offered by our findings offer an important contribution to the literature. Transferability across populations may be limited due to selection bias. Parents who volunteered to participate were of relatively similar genders and races, and parents of children whose child died from acute illness or injury did not volunteer for this study. Though the sample was small, similar patterns of needs among different parent and child ages, lengths of stay, and chronic/cancer illness trajectories indicated saturation (Hennink et al., 2016; Morse, 2015a; Streubert & Carpenter, 2007). Parents who did not volunteer also may have experienced EOL and grief differently, but the parents in our study reflected on both positive and negative aspects of their memories. These limitations, along with the extant literature, reveal that voices are missing from the field of paediatric palliative care research; particularly those of fathers, minoritised populations, and the acutely terminally ill, warranting further study.

Conclusion

The death of a child remains a tremendous hardship for families and clinicians alike. Parents relive the relational, clinical, situational, and emotional needs of their child’s EOL in the PICU as they endure through a lifelong grieving process. Fulfilling these needs, especially when they intersect, can improve how clinicians support parents through the transition from being a parent of a dying child to being a parent who is grieving.

Implications for clinical practice:

Parents of children who died in the paediatric intensive care unit defined intersecting relational, clinical, situational, and emotional EOL needs that impact their grief for years to come

The need to be together with the child is most important, but often conflicts with clinical and situational considerations, such as medical devices/equipment and visitation policies

Bedside nurses can aid in parents’ transition to their lifelong grieving process by fulfilling parents’ need to be with the child, facilitating parent-child closeness (holding the child, getting in bed with the child) amidst clinical equipment and intssensive care processes

Acknowledgments

The authors hope to honour the lives and stories of the children who died in the PICU and their families through this work. The authors also acknowledge Clare Whitney, PhD, RN, MBE, for her unmatched editorial eye.

The following RESTORE site P.I.’s aided with recruitment: Adriana Muñiz RN, BSN; Natalie Cvijanovich; MD, Shelley Diane, MS, RN, CCNS, CCRN; Santiago Borasino MD, MPH; Meghan Murdock RN, BSN; Larissa Hutchins, MSN, RN, CCRN-K, CCNS, NEA-BC; Lauren R. Sorce PhD, RN, CPNP-AC/PC, CCRN, FCCM; Chaandini Jayachandran MS CCRP; Aileen Kirby, MD; Melissa Harward, MS, CCRC, CPhT; Judy Ascenzi, DNP, RN, CCRN-K; Emily Warren, MSN, RN, ACCNS-P, CCRN-K; Colleen Meren, BSN, RN; Mary Jo Grant, APRN-AC, PhD, FAAN; John Lin, MD; Shari Simone, DNP, CPNP-AC, FAANP, FCCM, FAAN; Joana Tala, MD; Allison Cowl. MD; Ofelia Vargas-Shiraishi, BS CCRC.

Funding Source

Elizabeth Broden was funded by a National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research training grant (F31NR018104) and the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation. The RESTORE clinical trial was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01HL086622 to Dr. Curley and U01HL086649 to the Data Coordinating Center). This work was conducted as part of Elizabeth Broden’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ananth P, Mun S, Reffat N, Li R, Sedghi T, Avery M, Snaman J, Gross CP, Ma X, & Wolfe J (2021). A stakeholder-driven qualitative study to define high quality end-of-life Care for children with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(3), 492–502. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Tucker M, Dominguez T, & Helfaer M (2004). Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 5(6), 547–553. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000137354.19807.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Reijntjes A, & Smid GE (2016). Concurrent and prospective associations of intolerance of uncertainty with symptoms of prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression after bereavement. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 41, 65–72. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broden EG, Deatrick J, Ulrich C, & Curley MAQ (2020). Defining a “Good Death” in the pediatric intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 29(2), 111–121. 10.4037/ajcc2020466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broden EG, Hinds PS, Werner-Lin AV, Quinn R, Asaro L, Curley MAQ (2022). Nursing care at end-of-life in PICU patients requiring mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Critical Care, (accepted for publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burns JP, Mitchell C, Outwater KM, Geller M, Griffith JL, Todres ID, & Truog RD (2000). End-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit after the forgoing of life-sustaining treatment. Critical Care Medicine, 28(8), 3060–3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AE, Hall H, & Copnell B (2018). Becoming a team: The nature of the parent-healthcare provider relationship when a child is dying in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 40, e26–e32. cin20. 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MA, & Foito K (2019). Pediatric end-of-life simulation: Preparing the future nurse to care for the needs of the child and family. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 44, e9–e12. 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (Third edition.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Curley MAQ, Wypij D, Watson RS, Grant MJC, Asaro LA, Cheifetz IM, Dodson BL, Franck LS, Gedeit RG, Angus DC, & Matthay MA (2015). Protocolized sedation vs usual care in pediatric patients mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(4), 379–389. 10.1001/jama.2014.18399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie ER, Roche C, Christian BJ, Bakitas M, & Meneses K (2016). Recruiting bereaved parents for research after infant death in the neonatal intensive care unit. Applied Nursing Research, 32, 281–285. 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg JL, Tibboel D, Ganzevoort RR, Gischler S, Hagoort J, & van Dijk M (2016). Parental physical proximity in end-of-life care in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 17(5), e212–217. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg JL, Tibboel D, Ganzevoort RR, Gischler SJ, & van Dijk M (2018). The importance of parental connectedness and relationships with healthcare professionals in end-of-life care in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 19(3), e157–e163. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster M, Whitehead L, & Maybee P (2016). The parents’, hospitalized child’s, and health care providers’ perceptions and experiences of family-centered care within a pediatric critical care setting: A synthesis of quantitative research. Journal of Family Nursing, 22(1), 6–73. 10.1177/1074840715618193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten L, Daehmlow S, Reindl T, Wendt A, Münch A, & Bührer C (2011). End-of-life opioid administration on neonatal and pediatric intensive care units: Nurses’ attitudes and practice. European Journal of Pain, 15(9), 958–965. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson CM, FitzGerald M, Hoehn KS, & Weidner N (2017). Pediatrician ambiguity in understanding palliative sedation at the end of life. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 34(1), 5–19. 10.1177/1049909115609294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M, Kaiser B, & Marconi V (2016). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. 10.1177/1049732316665344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, Powell B, Srivastava DK, Spunt SL, Harper J, Baker JN, West NK, & Furman WL (2009). “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(35), 5979–5985. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang TA, Hodge M, Olson V, Romano PS, & Kravitz RL (2004). Nurse-patient ratios: A systematic review on the effects of nurse staffing on patient, nurse employee, and hospital outcomes. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(7), 326–337. 10.1097/00005110-200407000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, & Guba E (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald ME, Liben S, Carnevale FA, & Cohen SR (2012). An office or a bedroom? Challenges for family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Child Health Care, 16(3), 237–249. 10.1177/1367493511430678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner B, Grier HE, Weeks JC, & Wolfe J (2005). Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 23(36), 9155–9161. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw SA, Truog RD, Solomon MZ, Cohen-Bearak A, Sellers DE, & Meyer EC (2012). “I was able to still be her mom”—Parenting at end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 13(6), e350–356. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31825b5607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert K, Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston C, & Kabel A (2009). Examining the needs of bereaved parents in the pediatric intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 33(8), 712–740. 10.1080/07481180903070434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert K, Briller SH, Schim SM, & Thurston CS (2008). Exploring parents’ environmental needs at the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 9(6), 623–628. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d30d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert K, Keele L, Morrison W, Berg RA, Dalton H, Newth CJL, Harrison R, Wessel DL, Shanley T, Carcillo J, Clark A, Holubkov R, Jenkins TL, Doctor A, Dean JM, & Pollack M (2015). End-of-life practices among tertiary care pediatric intensive care units in the U.S.: A multicenter study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 16(7), e231–e238. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer E, Burns JP, Griffith JL, & Truog RD (2002). Parental perspectives on end-oflife care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 30(1), 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Carter C, Hennessey H, Eberly, & Riddle. (1989). Testing a theoretical model: Correlates of parental stress responses in the pediatric intensive care unit. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal, 18(3), 207–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison W, & Kang T (2014). Judging the quality of mercy: Drawing a line between palliation and euthanasia. Pediatrics, 133(Supplement 1), S31–S36. 10.1542/peds.2013-3608F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2015a). “Data Were saturated. . . .” Qualitative Health Research, 25(5), 587–588. 10.1177/1049732315576699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2015b). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. 10.1177/1049732315588501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, & Sondergaard J (2009). Qualitative description—The poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 52. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R (Ed.). (2001). Meaning Reconstruction & the Experience of Loss. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R, Klass D, & Dennis MR (2014). A Social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies, 38(8), 485–498. 10.1080/07481187.2014.913454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, & Hinds PS (2014). The parent perspective: “being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 15(4), 291–298. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea ER, Campbell SH, Engler AJ, Beauregard R, Chamberlin EC, & Currie LM (2015). Effectiveness of a perinatal and pediatric end-of-life nursing education consortium (ELNEC) curricula integration. Nurse Education Today, 35(6), 765–770. Scopus. 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVIVO (Version 12) [Computer software]. QSR International Pty Ltd. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home [Google Scholar]

- Rolnick JA, Ersek M, Wachterman MW, & Halpern SD (2020). The quality of end-oflife care among ICU versus ward decedents. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 201(7), 832–839. 10.1164/rccm.201907-1423OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84. 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers DE, Dawson R, Cohen-Bearak A, Solomond MZ, & Truog RD (2015). Measuring the quality of dying and death in the pediatric intensive care setting: the clinician PICU-QODD. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(1), 66–78. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk BA, Friedrich AB, DuBois J, & Mack JW (2020). Emotional communication in advanced pediatric cancer conversations. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59(4), 808–817.e2. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streubert HS, & Carpenter D (2007). Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Perspective (Fourth Edition). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schoot R van de Schut H., Abakoumkin G, & Li J (2014). Guilt in bereavement: The role of self-blame and regret in coping with loss. PLoS ONE, 9(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0096606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge A, Walter JK, McConathey E, Morrison W, & Feudtner C (2018). Modes of death within a children’s hospital. Pediatrics, e20174182. 10.1542/peds.2017-4182 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Truog RD, Meyer EC, & Burns JP (2006). Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 34(11 Suppl), S373–379. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237043.70264.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, & Bondas T (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loenhout RB, Van Der Geest IMM, Vrakking AM, Van Der Heide A, Pieters R, & Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink MM (2015). End-of-life decisions in pediatric cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(8), 697–702. Scopus. 10.1089/jpm.2015.29000.rbvl [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VitalTalk, 2022. Resources. https://www.vitaltalk.org/resources/ (accessed 18.01.2022)

- Wheeler I (2001). Parental bereavement: The crisis of meaning. Death Studies, 25(1), 51–66. 10.1080/07481180126147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]