Abstract

Background:

There is limited data to inform minimum case requirements for training in robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting (RA-CABG). Current recommendations rely on nonclinical endpoints and expert opinion.

Objectives:

To determine the minimum number of RA-CABG procedures required to achieve stable clinical outcomes.

Methods:

We included isolated RA-CABG in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) registry performed between 2014 and 2019 by surgeons without prior RA-CABG experience. Outcomes were approach conversion, reoperation, major morbidity or mortality, and procedural success. Case sequence number was used as a continuous variable in logistic regression with restricted cubic splines with fixed effects. Outcomes were compared between operations performed earlier versus later in case sequences using unadjusted and adjusted metrics.

Results:

There were 1195 cases performed by 114 surgeons. A visual inflection point occurs by a surgeon’s 10th procedure for approach conversion, major morbidity or mortality, and overall procedural success after which outcomes stabilize. There was a significant decrease in the rate of approach conversion (7.7% and 2.5%), reoperation (18.9% and 10.8%), and major morbidity or mortality (21.7% and 12.9%), as well as an increase in the rate of procedural success (72.9% and 85.3%) with increasing experience between groups. In a multivariable logistic regression model, case sequences of >10 were an independent predictor of decreased approach conversion (odds ratio [OR]: 0.27; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.09-0.84) and increased rate procedural success (OR: 1.96; 95% CI: 1.00-3.84).

Conclusions:

The learning curve for RA-CABG is initially steep, but stable clinical outcomes are achieved after the 10th procedure.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary artery disease, coronary artery revascularization, learning, learning curve, minimally invasive, robot, robotic, skill acquisition

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Robotically assisted coronary artery bypass procedures (RA-CABG) can potentially offer numerous advantages over traditional sternotomy.1,2 Despite this, RA-CABG represents roughly 1% of total CABG procedures performed in the United States.1 Reasons for slow adoption might include cost, lack of institutional support, technical demand, and lack of a formalized training regime.

In 2016, a joint Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) task force was created to address the gaps in RA-CABG utilization and implementation. Optimal surgeon training has been identified as a critical component of procedural development across various domains remains central to their tasks; however, their recommendations to date rely mostly on expert opinion and single-institution analyses of component-specific operative times.3 The purpose of this study is to quantify the learning curve associated with RA CABG. As a corollary, we sought to define how surgeon experience is related to clinical outcomes following RA-CABG using a large national database. Understanding this learning curve will help our community better understand how to train cardiac surgeons to perform robotic procedures.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Case selection

We studied outcomes from all isolated RA-CABG procedures in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (ACSD) performed between July 2014 and June 2018 (data versions 2.81 and 2.9). Earlier versions of the ACSD do not include a variable for operative approach conversion and were excluded.

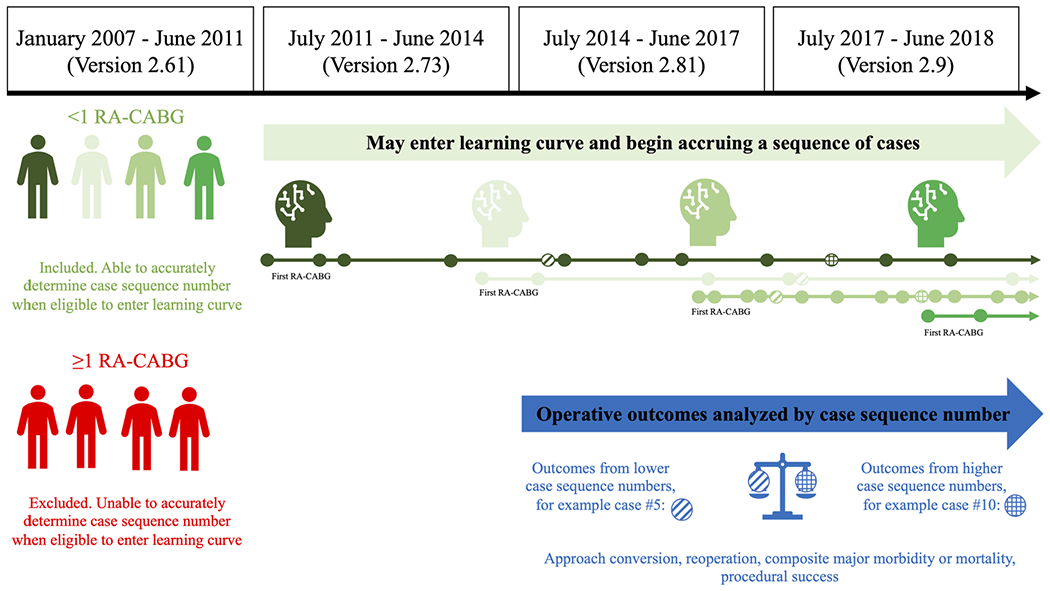

2.2 |. Determination of case sequence number

Each procedure was assigned a case sequence number that represents the order of its occurrence within each surgeon’s experience. Although outcomes were limited to data from versions 2.81 and 2.9, operations performed between July 2011 and July 2014 (data version 2.73) were permitted to count toward a surgeon’s case sequence number for operations performed between July 2014 and July 2018. This was done to maximize the number of eligible surgeons contributing who could be included in the study. We eliminated all surgeons who performed ≥1 RA-CABG procedures in the 4 years before July 2011 to ensure the accuracy of case sequence numbers for the study participants (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Methodology for determining surgeon case-sequence number and cases analyzed

For example, suppose a surgeon performed two RA-CABG procedures in 2007. This surgeon would be excluded from the study because there is no way to determine whether the two RA-CABG procedures performed in 2007 were his and her first and second or 99th and 100th due to lack of data before 2007. The ACSD does not capture the entire operative experience surgeons in practice before 2007. As another example, suppose a surgeon did not perform any RA-CABGs before 2011, but performed 20 RA-CABGs between July 2011 and June 2014. Unfortunately, key outcome variables are not available in the ACSD for these 20 procedures, but he/she has still accrued the experience 20 RA-CABG procedures. Instead of excluding this surgeon from the study, we credited this experience toward cases performed after July 2014, for which we had outcome data. Therefore, if this same surgeon performed their next RA-CABG on July 4, 2011, this would be considered RA-CABG number 21 and the outcome of the procedure would be associated with the 21st case sequence number, even though it was the first of the surgeon’s case series to contribute outcome data. As a final example to illustrate the concept of case sequence, if there were 14 additional surgeons who had also performed at least 21 RA-CABG procedures by July 4, 2011, then there would be a total of 15 patients at this time who were contributing outcome data to the 21st case sequence.

2.3 |. Determination of procedure and outcomes

Isolated CABG was defined in accordance with the STS. A procedure was considered robot assisted if a robot was used during any part. Baseline patient characteristics included in the STS 2008 CABG risk model were used (Supporting Information Appendix Table 1).4 Primary outcomes were rate of unanticipated approach conversion, reoperation, composite major morbidity or mortality, and procedural success. Procedural success is an inverse composite of the other three primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes were operative mortality and prolonged length of hospitalization. All outcomes except for procedural success are defined in accordance with the STS (Supporting Information Appendix Table 2).

2.4 |. Statistical analysis: Case sequence and the volume-outcome relationship

Case sequence number was used as a continuous variable in univariable logistic regression with restricted cubic splines with fixed effects. Splines were truncated after case sequence number 25 because too few surgeons performed more than 25 cases. The results of a Type III test with fixed effects are reported with each.

This methodology allows the “learning curve” associated with each outcome to be visually represented. The slope at any given point represents the log odds of the outcome occurring. Therefore, a point at which the slope is steep indicates rapid change in the outcome, whereas a point at which the slope is flat indicates stability in the rate of the outcome. Curves are visually analyzed to determine points the case number at which stability is reached.

2.5 |. Statistical analysis: Dichotomized case sequence and the volume-outcome relationship

Next, each case was categorized into two groups by surgeon case sequence number. Group 1 is composed of patients whose procedure occurred within a surgeon’s first 10 cases and Group 2 is composed of patients whose procedure occurred after a surgeon’s first 10 cases. Case number 10 was chosen based on a visually evident inflection point in the spline for procedural success, as described in the previous section. The rate of each outcome was described using the appropriate descriptive statistic and compared between Groups 1 and 2 using a χ2 test or t test.

Multivariable logistic regression with case sequence number dichotomized as ≤10 or >10 and surgeon as a fixed effect was performed for each primary outcome. Variables included in the model were chosen using stepwise selection. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4.

This project was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board approval. The data for this study were provided by the STS’ National Database Participant User File Research Program. Data analysis was performed at the investigators’ institution(s). The results were reviewed and approved by the STS Participant User File Adult Cardiac Committee.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient and surgeon characteristics

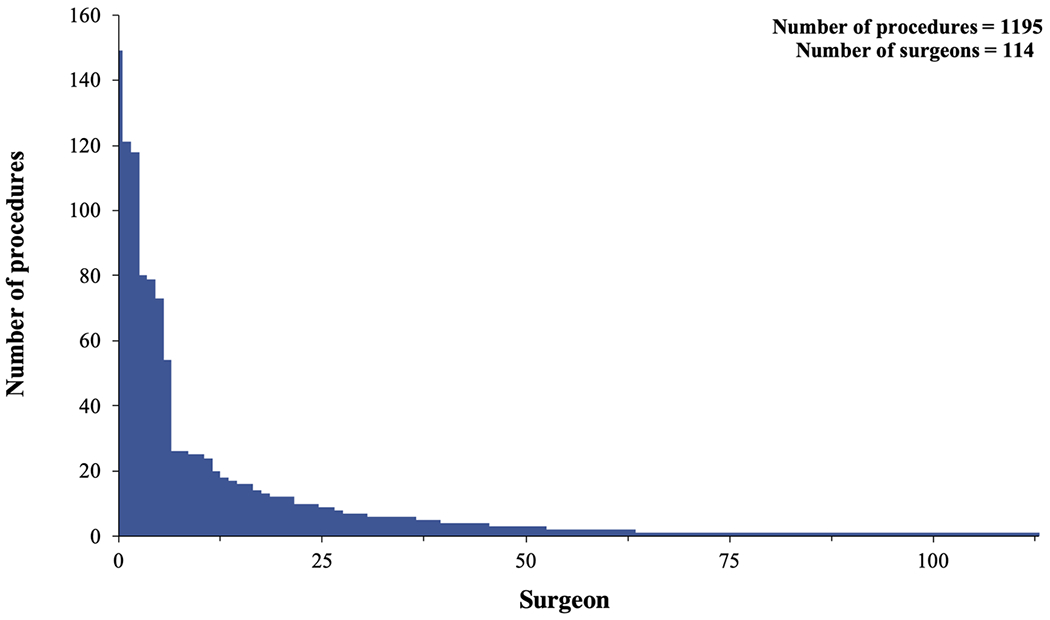

During the study period, 1195 RA-CABGs were performed by 114 surgeons with known sequence counts across 98 institutions. This cohort represents 18% (1195/6815) of RA-CABG procedures, 19% of surgeons (114/587), and 19% (98/525) institutions performing RA-CABG in the ACSD during the same time period (Supporting Information Appendix Figure 1). Surgeons performed a median of two procedures (IQR: 1-149). Nine surgeons performed >25 procedures and 74 surgeons performed <5 (Figure 2). Baseline characteristics are shown (Table 1). Patients were relatively young (65 ± 11 years) and predominantly male (76%). Overall, this cohort was healthier than usual with relatively low STS predicted major morbidity or mortality (10%); however, the prevalence of comorbidities, such as chronic lung disease (25%), peripheral vascular disease (13%), congestive heart failure (18%), recent myocardial infarction (8%), and diabetes (59%) was comparable to that of the national average for a traditional CABG.4 No patients were in the cardiogenic shock before the operation and 19 (2%) required a preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump, a rate that is less than a third of the national average for a traditional CABG (7%).4 The majority of cases were performed electively (75%), which is a higher rate than in traditional CABG (55%). Emergent or salvage procedures were rare (1%).

FIGURE 2.

Total number of robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting performed by each surgeon

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | All (n = 1195) | Group 1 (≤10) (n = 465) | Group 2 (>10) (n = 730) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 64.7 ± 11.0 | 64.6 ±11.1 | 64.8 ± 10.9 | .7417 |

|

| ||||

| Male, no. (%) | 913 (76.4) | 356 (76.6) | 557 (76.3) | .9185 |

|

| ||||

| Ejection fraction (fraction) | 52.5 ± 11.9 | 51.5 ± 13.7 | 52.9 ± 10.9 | .2977 |

|

| ||||

| Body surface area (m2) | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | .2549 |

|

| ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | .9144 |

|

| ||||

| Dialysis, no. (%) | 13 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) | .5903 |

|

| ||||

| Arrythmia, no. (%) | 155 (13.0) | 62 (13.3) | 93 (12.7) | .7659 |

|

| ||||

| Shock, no. (%) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | NA |

|

| ||||

| Preoperative IABP | 19 (1.6) | 11 (2.4) | 8 (1.1) | .0871 |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 1045 (87.4) | 388 (83.4) | 657 (90.0) | .0009 |

|

| ||||

| Immunosuppression, no. (%) | 39 (3.3) | 18 (3.9) | 21 (2.9) | .3456 |

|

| ||||

| Prior PCI, no. (%) | 505 (42.3) | 192 (41.3) | 313 (42.9) | .5883 |

|

| ||||

| PVD, no. (%) | 149 (12.5) | 54 (11.6) | 95 (13.0) | .4748 |

|

| ||||

| Left main CAD, no. (%) | 85 (7.1) | 35 (7.5) | 50 (6.8) | .6568 |

|

| ||||

| Aortic stenosis, no. (%) | 36 (3.0) | 14 (3.0) | 22 (3.0) | .9977 |

|

| ||||

| Aortic insufficiency, no. (%) | 127 (10.6) | 63 (13.5) | 64 (8.8) | .0089 |

|

| ||||

| Mitral insufficiency, no. (%) | 331 (27.7) | 128 (27.5) | 203 (27.8) | .9156 |

|

| ||||

| Tricuspid insufficiency, no. (%) | 933 (78.1) | 361 (77.6) | 572 (78.4) | .7688 |

|

| ||||

| Chronic lung disease, no. (%) | .0106 | |||

| None | 112 (9.4) | 36 (7.7) | 76 (10.4) | - |

| Mild | 37 (3.1) | 23 (4.9) | 14 (1.9) | - |

| Moderate | 28 (2.3) | 9 (1.9) | 19 (2.6) | - |

| Severe | 229 (19.2) | 93 (20.0) | 136 (18.6) | - |

|

| ||||

| CVD/CVA, no. (%) | .6113 | |||

| No CVD | 975 (81.6) | 384 (82.6) | 591 (81.0) | - |

| CVD without CVA | 139 (11.6) | 50 (10.8) | 89 (12.2) | - |

| CVD with CVA | 81 (6.8) | 31 (6.7) | 50 (6.8) | - |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | .0126 | |||

| No diabetes | 484 (40.5) | 167 (35.9) | 317 (43.4) | - |

| Diabetes not insulin dependent | 514 (43.0) | 207 (44.5) | 307 (42.1) | - |

| Diabetes insulin dependent | 197 (16.5) | 91 (19.6) | 106 (14.5) | - |

|

| ||||

| Myocardial infarction, no. (%) | .5464 | |||

| MI ≤ 6 h | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

| MI > 6 or <24 h | 2 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | - |

| MI 1 to 21 days | 95 (7.9) | 34 (7.3) | 61 (8.4) | - |

|

| ||||

| Race, no. (%) | .4649 | |||

| Black | 86 (7.2) | 31 (6.7) | 55 (7.5) | - |

| Asian | 39 (3.3) | 18 (3.9) | 21 (2.9) | - |

| White | 1012 (84.7) | 390 (83.9) | 622 (85.2) | - |

| Hispanic | 27 (2.3) | 7 (1.5) | 20 (2.7) | - |

| Other | 31 (2.6) | 19 (4.1) | 12 (1.6) | - |

|

| ||||

| Status, no. (%) | .0102 | |||

| Elective | 893 (74.7) | 328 (70.5) | 565 (77.4) | - |

| Urgent | 286 (23.9) | 127 (27.3) | 159 (21.8) | - |

| Emergent | 16 (1.3) | 10 (2.2) | 6 (0.8) | - |

| Salvage | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

|

| ||||

| CHF and NYHA class, no. (%) | .5112 | |||

| No CHF | 983 (82.3) | 388 (83.4) | 595 (81.5) | - |

| CHF not NYHA IV | 166 (13.9) | 58 (12.5) | 108 (14.8) | - |

| CHF with NYHA IV | 46 (3.8) | 19 (4.1) | 27 (3.7) | - |

|

| ||||

| Endocarditis, no. (%) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | NA |

|

| ||||

| Carotid stenosis, no. (%) | 103 (8.6) | 32 (6.9) | 71 (9.7) | .0876 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer within 5 years, no. (%) | 53 (4.4) | 24 (5.2) | 29 (4.0) | .3305 |

|

| ||||

| Tobacco use, no. (%) | 678 (56.7) | 262 (56.3) | 416 (57.0) | .8271 |

|

| ||||

| Liver disease, no. (%) | 30 (2.5) | 18 (3.9) | 12 (1.6) | .0164 |

|

| ||||

| PROMM (fraction) | 10.1 ± 8.7 | 10.5 ± 10.3 | 9.9 ± 7.5 | .2208 |

Note: Plus-minus values are means ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CVD, cerebral vascular disease; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PROMM, predicted rate of major morbidity or mortality; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

3.2 |. Clinical outcomes

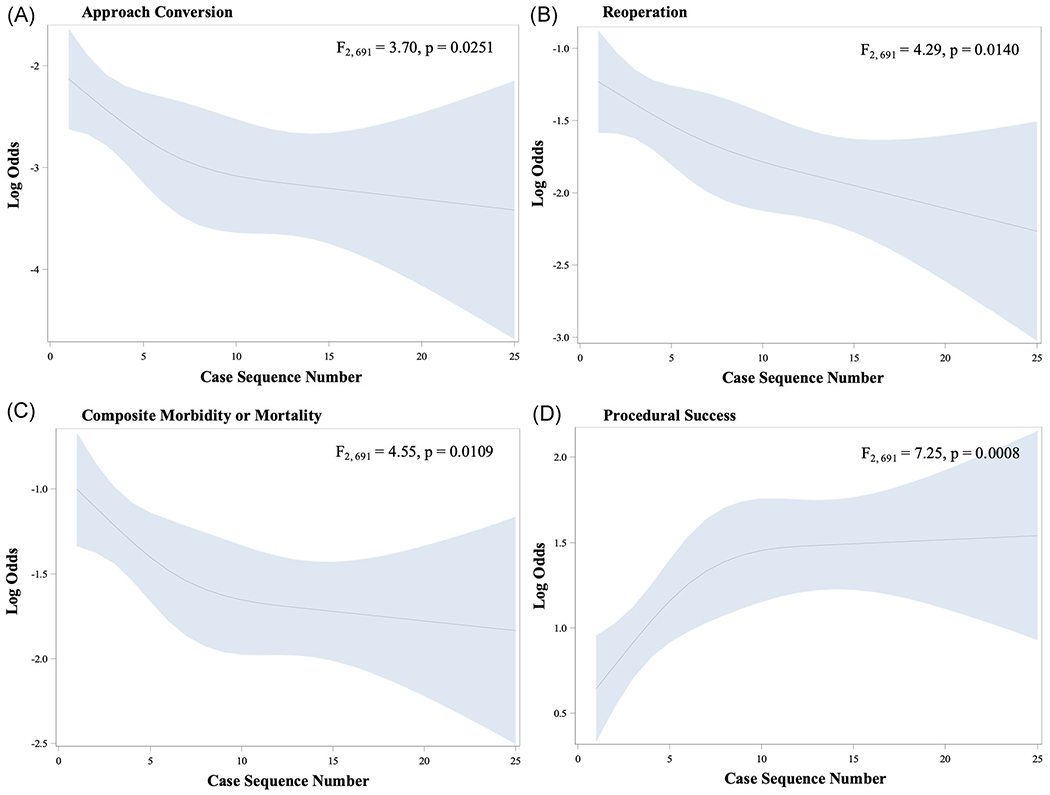

There is a visually evident inflection point for rate of approach conversion at approximately eight cases, after which the learning curve begins to flatten, but not completely (F2,691 = 3.70, p = .0251) (Figure 3A). For reoperation, the inflection point is less apparent, likely around case 8, but has not flattened by case 25 (F2,691 = 4.29, p = .0140) (Figure 3B). The inflection point for composite morbidity or mortality occurs at approximately 8 cases (F2,691 = 4.55, p = .0109) (Figure 3C). For the composite endpoint of procedural success, an inflection point is evident around 10 cases (F2,691 = 7.25, p = .0008) (Figure 3D). For procedural success, major morbidity or mortality, and approach conversion there continues to be gradual learning out to 25 cases, but in this slow.

FIGURE 3.

Learning curves for robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting for (A) approach conversion (B) reoperation (C) composite morbidity or mortality and (D) procedural success

Cases were categorized into two groups based on surgeon case sequence number ≤10 (Group 1) or >10 (Group 2). Baseline characteristics were similar between groups with the exceptions that Group 1 contains fewer patients and has a significantly higher rate of chronic lung disease, insulin-dependent diabetes, hypertension, liver disease, and is more likely to have been done urgently (Table 1). Patients in Group 1 were less likely to be completed off-pump, had longer durations of cardiopulmonary bypass utilization and were more likely to receive multiple grafts than those in Group 2 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Intraoperative characteristics of the sample population

| Characteristic | Group 1 (≤10) (n = 465) | Group 2 (>10) (n = 730) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-pump, n (%) | 361 (77.6) | 709 (97.1) | <.0001 |

| CPB time (min), mean (SD) | 91.8 (31.6) | 84.1 (49.4) | .0028 |

| Total grafts, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.4) | <.0001 |

Abbreviation: CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass.

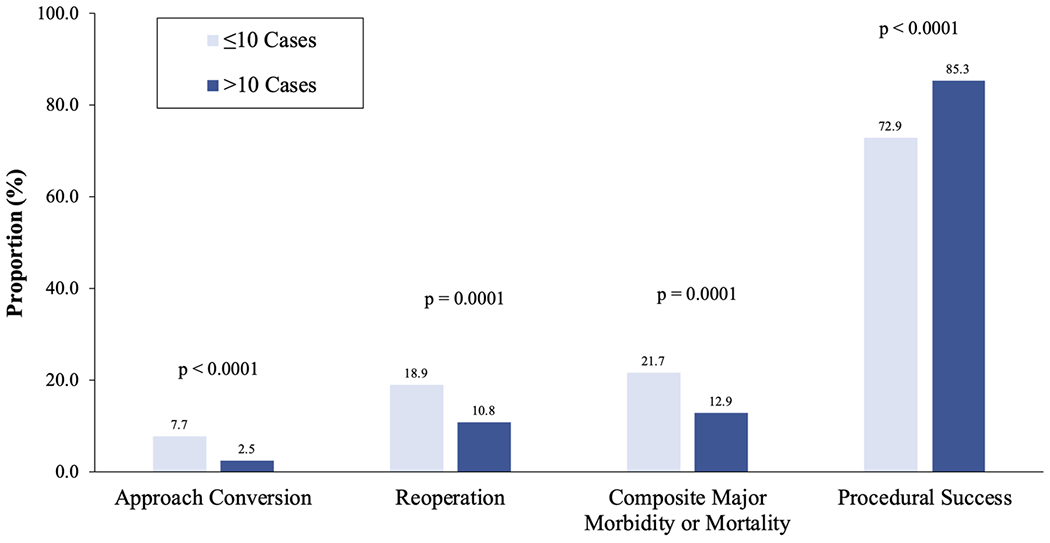

There was a significant association between the primary outcomes and the surgeon experience group. The rate of approach conversion was 7.7% and 2.5% (p < .0001), reoperation 18.9% and 10.8% (p = .0001), and major morbidity or mortality 21.7% and 12.9% (p = .0001) in Groups 1 and 2, respectively. Correspondingly, the rate of procedural success was 72.9% for Group 1 and 85.3% for Group 2 (p < .0001) (Figure 4). The overall rate of operative mortality was 0.8% and there was no significant difference between groups. There was also no significant difference in prolonged length of stay (Table 3).

FIGURE 4.

Rate of clinical endpoint for robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting performed later in a sequence (>10 cases) versus earlier (≤10 cases)

TABLE 3.

Rate of clinical outcomes for the entire study population and for inexperienced and experienced surgeons

| Endpoint | All (n = 1195) | Group 1 (<10) (n = 465) | Group 2 (>10) (n = 730) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||||

| Approach conversion, no. (%) | 54 (4.5) | 36 (7.7) | 18 (2.5) | <.0001 |

| Reoperation, no. (%) | 167 (14.0) | 88 (18.9) | 79 (10.8) | <.0001 |

| Composite major morbidity or mortality, no. (%) | 195 (16.3) | 101 (21.7) | 94 (12.9) | <.0001 |

| Procedural success, no. (%) | 962 (80.5) | 339 (72.9) | 623 (85.3) | <.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Secondary | ||||

| Operative mortality, no. (%) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | .4702 |

| Prolonged length of hospitalization, no. (%) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | .7475 |

Multivariable logistic regression with stepwise selection demonstrates that experience of >10 cases is an independent predictor of less frequent approach conversion (odds ratio [OR]: 0.27; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.09-0.84) and increased procedural success (OR: 1.96; 95% CI: 1.00-3.84). Experience group was not found to be an independent predictor of reoperation or composite morbidity or mortality (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Results of multivariable regression analysis demonstrating adjusted associations between predictors and primary clinical outcomes

| Endpoint | Predictor | OR (95% CI) | p values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach conversion | Experience Group 2 (>10 cases) | 0.27 (0.09–0.84) | .0233 |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 0.24 (0.06–0.90) | .0341 | |

| Female gender | 5.61 (1.83–17.2) | .0026 | |

|

| |||

| Procedural success | Experience Group 2 (>10 cases) | 1.96 (1.00–3.84) | .0499 |

| Myocardial infarction between 1 and 21 days | 0.43 (0.19–0.95) | .0358 | |

|

| |||

| Composite major morbidity or mortality | Age | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | .0029 |

| Myocardial infarction between 1 and 21 days | 4.80 (1.88–12.2) | .001 | |

| Aortic insufficiency | 3.15 (1.03–9.62) | .0443 | |

| Hispanic race | 3.99 (1.27–12.5) | .0181 | |

|

| |||

| Reoperation | Mitral valve insufficiency | 3.92 (1.38–11.1) | .0104 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The primary findings of this study are:

Surgeon experience is an independent predictor of RA-CABG procedural success.

The learning curve for RA-CABG is initially steep, but consistently flattens after a surgeon’s 10th case.

The relationship between experience and performance is natural. Its study in the context of RA-CABG has been mostly limited to small, single-institution, single-surgeon case series evaluating the effect of experience on the efficiency of procedural components. Robotic takedown of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) can initially take a lengthy time, however, a period of rapid learning universally occurs with an inflection point between 5 and 20 cases with stabilization thereafter.5–8 Efficiency of port placement, speed of LIMA to coronary artery anastomosis, and total operative times show a similar trend.6–9 Surgeons will focus on achieving good clinical outcomes before focusing on performing the operation more quickly, which is why the learning curve for achieving stable clinical outcomes described in this paper may be fewer cases than the learning curve to complete the operation efficiently. Learning curves for similar endpoints have been observed in other fields such as robotic cystectomy, prostatectomy, and transoral surgery.10–12

This study demonstrates that the learning curve has significant implications for clinical outcomes in addition to procedural efficiency. We found clear inflection points for rates of approach conversion, major morbidity and mortality, and procedural success (Figure 3A,C,D). For each, stability is achieved after about the 10th case, with slow improvement beyond case 25. In contrast, an inflection point for reoperation is less evident and the curve is not stable by case 25 (Figure 3B).

This finding was reinforced when outcomes were dichotomized as within the first 10 cases or beyond the first 10. Rate of adverse outcomes declined and that of procedural success increased with experience (Figure 4). The rate of adverse events in the less experienced group was high, but consistent with other reports of early experience. Our rate of approach conversion was consistent with the rates reported in other series of 0%-11.5%, although definitions vary in the literature.7,9,13,14

We report a relatively high rate of reoperation in both experience groups; however, our definition is inclusive not only of reoperation for hemorrhage but also of graft occlusion, myocardial ischemia, and valve or aortic issues. The rate of major morbidity or mortality observed in the experienced surgeon group (12.9%) is similar to the overall rate previously reported in the STS ACSD for nearly 10,000 RA-CABG procedures (10.2%). Finally, a procedural success rate of 85.3% is disappointing, even for more experienced surgeons, but has precedent. In a 500-case series of totally endoscopic RA-CABG procedural success (similarly defined as no conversion or major adverse cardiac or cerebral events) was achieved in only 80% of cases.15

Notably, surgeon experience in the multivariable analysis was not an independent predictor of major morbidity or mortality. This may be due to the higher incidence of some comorbidities among patients in the lower experience group (Table 1). It may also be due to successful rescue by conversion to open, which was higher in earlier sequence numbers.

Because most surgeons are comfortable with traditional approaches to CABG, learned and practice during traditional training curriculums, the learning curve for RA-CABG consists of gaining competence with the robotic interface and set-up. For this reason, experience with other nontraditional approaches, for instance, robotically assisted mitral valve procedures, is likely to expedite the learning curve for RA-CABG. Additionally, time spent in the simulation of RA-CABG likely modifies the learning curve, though this has not been studied for RA-CABG. Also, the experience of other team members including bedside assistants, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, and nursing staff also contributes to clinical outcomes. Finally, the higher comorbidity burden observed in the lower experience group may hint at the possibility that patient selection, though nonprocedural, is an important aspect of the learning curve.

This study has several limitations. Only variables captured in the ACSD can be adjusted for in multivariable analyses, so it is possible that uncaptured variables could be confounding the association between surgeon experience and outcomes. Importantly, the extent of robotic utilization was not able to be determined from the STS ACSD, making distinctions between minimally invasive direct CABG (MIDCAB), totally endoscopic robotic CABG (TECAB), or hybrid procedures unreliable. Furthermore, we do not know whether cases were proctored. The effect of hospital experience could not be accounted for as a fixed effect because of nonconvergence.

5 |. CONCLUSION

The potential advantages of RA-CABG to the patient include shorter length of hospitalization, less postoperative pain and higher quality of life, and improved cosmesis.1,15 Given outcomes equivalent to non-RA-CABG, RA-CABG will continue to be an enticing strategy.1,16 Robotic technology will continue to improve, incorporating haptic feedback, visualization coregistration, remote proctoring, and more. Market forces are an incentive for increased robot utilization in coronary surgery. We show that the learning curve is steep, but flattens after approximately 10 cases. With informed guidance and a standardized curriculum, it is likely that cardiac surgeons can become safely trained in RA-CABG. We have demonstrated that in the current environment, negotiation of the learning curve is associated with an increase in adverse outcomes in RA-CABG.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was partially funded by a National Institutes of Health T32 Training Grant (T32HL007843). This study was presented at the Annual Meeting of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Virtual, Texas January 30-February 2, 2021 (Virtual).

Abbreviations:

- AATS

American Association for Thoracic Surgery

- ACSD

Adult Cardiac Surgery Database

- LIMA

left internal mammary artery

- MIDCAB

minimally invasive direct CABG

- RA-CABG

robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- TECAB

totally endoscopic robotic CABG

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whellan DJ, McCarey MM, Taylor BS, et al. Trends in robotic-assisted coronary artery bypass grafts: a study of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database, 2006 to 2012. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonaros N, Schachner T, Wiedemann D, et al. Quality of life improvement after robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting. Cardiology. 2009;114:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez E, Nifong LW, Bonatti J, et al. Pathway for surgeons and programs to establish and maintain a successful robot-assisted adult cardiac surgery program. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1-coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:S2–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oehlinger A, Bonaros N, Schachner T, et al. Robotic endoscopic left internal mammary artery harvesting: what have we learned after 100 cases? Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1030–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonatti J, Schachner T, Bernecker O, et al. Robotic totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass: program development and learning curve issues. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemli JM, Henn LW, Panetta CR, et al. Defining the learning curve for robotic-assisted endoscopic harvesting of the left internal mammary artery. Innovations (Phila). 2013;8:353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng N, Gao C, Yang M, Wu Y, Wang G, Xiao C. Analysis of the learning curve for beating heart, totally endoscopic, coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1832–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argenziano M, Katz M, Bonatti J, et al. Results of the prospective multicenter trial of robotically assisted totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1666–1674 discussion 74-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayn MH, Hussain A, Mansour AM, et al. The learning curve of robot-assisted radical cystectomy: results from the International Robotic Cystectomy Consortium. Eur Urol. 2010;58:197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaul S, Shah NL, Menon M. Learning curve using robotic surgery. Curr Urol Rep. 2006;7:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White HN, Frederick J, Zimmerman T, Carroll WR, Magnuson JS. Learning curve for transoral robotic surgery: a 4-year analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Göbölös L, Ramahi J, Obeso A, et al. Robotic totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting: systematic review of clinical outcomes from the past two decades. Innovations (Phila). 2019;14:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappert U, Cichon R, Schneider J, et al. Robotic coronary artery surgery—the evolution of a new minimally invasive approach in coronary artery surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;48:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonaros N, Schachner T, Lehr E, et al. Five hundred cases of robotic totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting: predictors of success and safety. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanagawa F, Perez M, Bell T, Grim R, Martin J, Ahuja V. Critical outcomes in nonrobotic vs robotic-assisted cardiac surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.