Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the global prevalence and common causes of visual impairment (VI) and blindness in children.

Methods:

In this meta-analysis, a structured search strategy was applied to search electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, as well as the list of references in the selected articles to identify all population-based cross-sectional studies that concerned the prevalence of VI and blindness in populations under 20 years of age up to January 2018, regardless of the publication date and language, gender, region of residence, or race. VI was reported based on presenting visual acuity (PVA), uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), and best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of equal to 20/60 or worse in the better eye. Blindness was reported as visual acuity worse than 20/400 in the better eye.

Results:

In the present study, 5711 articles were identified, and the final analyses were done on 80 articles including 769,720 people from twenty-eight different countries. The prevalence of VI based on UCVA was 7.26% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.34%–10.19%), PVA was 3.82% (95% CI: 2.06%–5.57%), BCVA was 1.67% (95% CI 0.97%–2.37%), and blindness was 0.17% (95% CI: 0.13%–0.21%). Refractive errors were the most common cause of VI in the subjects of selected articles (77.20% [95% CI: 73.40%–81.00%]). The prevalence of amblyopia was 7.60% (95% CI: 05.60%–09.10%) and congenital cataract was 0.60% (95% CI: 0.3%–0.9%).

Conclusion:

Despite differences in the definition of VI and blindness, based on PVA, 3.82%, and based on BCVA, 1.67% of the examined samples suffer from VI.

Keywords: Blindness, Children, Low vision, Visual impairment

INTRODUCTION

Visual impairment (VI) in childhood has a negative and sometimes irreversible impact on children's psychological, educational, and social performance, which can persist into adulthood and affect individuals' quality of life.1 Given the significant burden of VI, its causes, and visual complications, the VISION 2020 Initiative was implemented by the World Health Organization (WHO) to eliminate preventable blindness on a global level.2,3 According to WHO estimates at the beginning of the VISION 2020 program, about 19 million children under the age of 15 years were visually impaired and 1.4 million children had irreversible blindness, and it was predicted that half of the blindness cases were preventable.4 The reported prevalence of blindness in low and middle-income countries ranges from 0.2 to 7.8/10,000 people, and in developed and industrialized countries, the annual incidence is 6/10,000 in the under-15 age group.5,6 According to available information, the causes of VI differ by the residence location of the studied population (urban versus rural) or in different countries (developed, under developed, or developing) as well as the prevention strategies within each health system. Nevertheless, Courtright et al. suggest that retinal disorders, glaucoma, corneal ulcers due to vitamin A deficiency, cataract, and neural causes are the most common causes of VI in low and middle-income countries.5 This is while neurological disorders are one of the major causes of VI in industrialized countries, and in countries such as England, 75% of blindness cases are due to unpreventable causes.7,8 A large amount of information on VI in children has been generated from population-based and clinic-based studies, studies in schools for blind children, different age groups (3–5 years, 7-years, 3–10 years, under-15-years, 5–15 years, etc.) as well as different settings such as high-income and low-income countries, but due to the mentioned differences, it is not possible to make global policies or evaluate measures that have been taken in this regard. Given the lack of cohesive results on the prevalence of VI as well as the differences in the causes of VI in different parts of the world, it seems necessary to have an estimate of the global prevalence and causes of VI in children to inform policies, especially the Vision 2020 Initiative. Therefore, the present study aims to determine the overall prevalence and causes of VI in children in the world.

METHODS

The entire process of this study was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.9 All population-based cross-sectional studies concerning the prevalence of VI and blindness in individuals under 20 years of age were reviewed regardless of publication and language, gender, region of residence, and race. The search strategy and entry terms showed in Appendix 1. Of studies conducted on the same population, the one with a higher quality was included in this review. Also, we included studies that were performed in all age groups and used the prevalence rates reported for the under-20-year age groups. We excluded articles that did not have one or more of the inclusion criteria. The outcome of interest was the prevalence of VI and blindness and the causes of VI in the population. In the selected papers, cases of VI were identified using measurements based on different units including feet, logMAR, and meters. For this reason, and to facilitate the presentation of the results, all measurements were converted to feet.

The prevalence of VI in this study was calculated based on uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and presenting visual acuity (PVA) as reported in previous studies.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 The participant's PVA was considered UCVA in participants without glasses and visual acuity with present glasses in individuals with glasses. According to previous studies, the prevalence of VI was reported based on visual acuity cut-point of 20/40 or worse and 20/60 or worse in the better eye (according to the WHO guidelines, VI based on PVA, UCVA, and BCVA was considered as visual acuity in the better eye of equal to 20/60 or worse). The prevalence of blindness was determined based on: (1) BCVA of 20/200 or worse in the better-seeing eye, and (2) BCVA of 20/400 or worse in the better-seeing eye (according to the WHO guidelines, blindness was defined as visual acuity worse than 20/400 in the better eye). We excluded the studies that specifically investigated the VI and blindness in the schools for the blind.

To ensure the correct selection of articles related to the topic of the research and in accordance with the inclusion criteria, two researchers (E.H. and M.S.) independently selected the articles; they were not blinded to the names of the authors, the journal titles, or study results. The kappa agreement index between researchers was 80.2%. Cases of controversy between the researchers were decided through discussion or by consulting a third person. The two researchers independently extracted the required data based on predefined variables. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist41 to perform a qualitative assessment of the selected articles in terms of methodology and report. Present key elements of study design, describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants, clearly define all outcomes, and report numbers of outcome events or summary measures were assessed. The studies were categorized as low risk of bias if they reported all items, as moderate risk of bias if they reported all items but one, and as high risk of bias otherwise. To examine the inconsistency of the articles, the k-square test was used at a 5% confidence interval (CI). In order to quantitatively analyze the heterogeneity of the results, we used the I-square test based on the Higgins classification. According to which, an I-square more than 75% was considered as heterogeneity. The variables investigated in this study included the name of the first author, the year of publication, the country of the study, the mean age and gender distribution of study subjects, sample size, the prevalence VI (based on UCVA, PVA, and BCVA) and blindness with their 95% CI, and the prevalence of the most important causes of VI and blindness. One of the PRISMA checklist items is calculating publication bias. In our study, publication bias was not assessed because the prevalence is always a positive number between zero and one, and cannot be negative; therefore, all studies were distributed on the right side of the vertical line, and this leads to asymmetry in the funnel plot which is not related to publication bias. Data analysis was performed using Stata Software version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The data was analyzed using the random-effects model at a 95% confidence level.

RESULTS

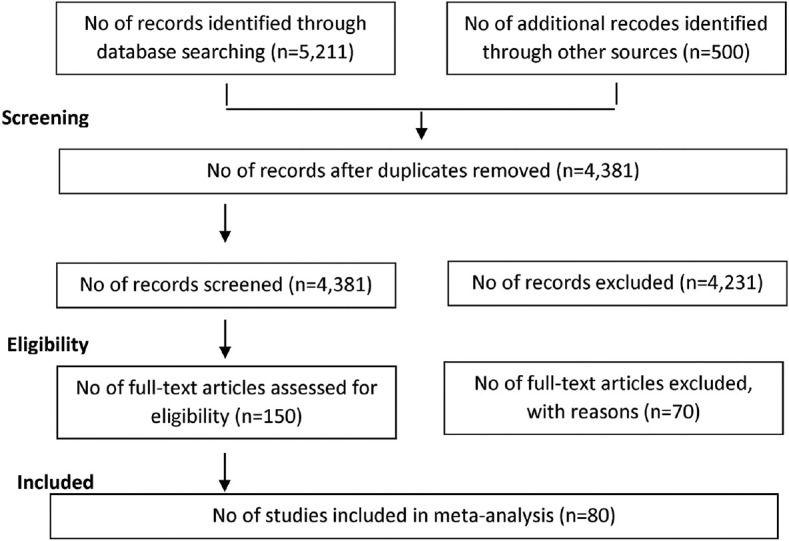

In the present study, 5711 studies were identified; 5211 articles by searching electronic databases and 500 articles through the lists of references of selected articles and other sources. After removing redundant articles, the title and abstract of 4381 articles were reviewed, and 4231 articles were excluded after applying the exclusion criteria, and thus, 150 papers were eligible for full-text review. After reviewing the full text of the articles, 70 articles were excluded from the study for not meeting the inclusion criteria, lack of access to the full text of the article, nonoriginal paper (letter, commentary, review), and finally, data for this study were extracted from 80 articles [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review

As shown in Table 1, the final 80 papers comprised 769,720 people from a total of 28 different countries.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83

Table 1.

Summary of studies results

| 1st author | Country (city) | Gender percentage male | Age mean, range | SS | UCVA % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu-Shagra et al., 199142 | Saudi Arabia | 100 | 10.9 (6-19) | 1188 | - |

| Adhikari et al., 201443 | Nepal | 47.3 | 5.7±3.1 (0-10) | 10,950 | - |

| Ajaiyeoba et al., 200744 | Nigeria | 44.1 | 11.8±3.8 (4-18) | 1144 | - |

| Akogun 199245 | Nigeria | 54.5 | 9-19 | 1600 | - |

| A1 Faran et al., 199346 | Saudi Arabia | 49.0 | 0-19 | 1909 | - |

| Alrasheed et al., 201647 | Sudan | - | 6-15 | 1678 | 6.40 (4.90-7.90) |

| Beiram 197148 | Sudan | - | 0-19 | 127,426 | - |

| Bucher and Ijsselmuiden, 198849 | South Africa | 40.5 | 0-19 | 44,977 | - |

| Casson et al., 201250 | Asia | 49.9 | 6-11 | 2899 | - |

| Congdon et al., 200827 | China | 50.2 | 14.7±0.8 (11.4-17.1) | 1892 | 41.17 (38.94-43.42) |

| Dandona et al., 199940 | India | - | 0-15 | 663 | - |

| Dandona et al., 200151 | India | - | 0-15 | 2859 | - |

| Darge et al., 201752 | Ethiopia | 50.8 | 11.05±2.5 (5-16) | 378 | - |

| Demissie and Solomon, 201153 | Ethiopia | - | 0-15 | 58,480 | - |

| Dorairaj et al., 200854 | India | - | 3-15 | 13,241 | - |

| Drews et al., 199255 | Atlanta | - | 10 | 89,534 | - |

| Farber 200356 | Israel | 48.6 | 0-18 | 1161 | - |

| Feghhi et al., 200957 | Iran | 40.5 | 5-19 | 2492 | - |

| Flanagan et al., 200358 | Ireland | - | 10.5±4.8 (1-18) | 47,110 | - |

| Fotouhi et al., 200729 | Iran | 52.1 | 7-15 | 5544 | - |

| Ghosh et al., 201259 | India | 45.8 | 6-14 | 2570 | 4.24 (3.41-5.10) |

| Gilbert et al., 200826 | Six countries | 51.7 | 5-15 | 40,779 | - |

| Goh et al., 200532 | Malaysia | 50.8 | 7-15 | 4634 | 17.07 (15.99-18.18) |

| Hashemi et al., 201811 | Iran | - | 1-15 | 766 | - |

| He et al., 201417 | China | 57.9 | 7-12 | 9512 | 13.33 (12.65-14.03) |

| He et al., 200728 | China | 52.5 | 13-17 | 2454 | 27.04 (25.27-28.86) |

| He et al., 200433 | China | 51.9 | 5-15 | 4364 | 22.27 (21.04-23.54) |

| Heijthuijsen et al., 201360 | Suriname | - | 8-16 | 4643 | - |

| Jamali et al., 200961 | Iran | - | 6 | 902 | 3.55 (2.39-5.07) |

| Johnson and Minassian, 198962 | Africa | - | 0-6 | 5436 | - |

| Kaphle et al., 201663 | Malawi | 54.8 | 0-15 | 635 | - |

| Kedir and Girma, 201464 | Ethiopia | 54.1 | 7-15 | 592 | - |

| Kemmanu et al., 201665 | India | - | ≤15 | 23,087 | - |

| Khandekar et al., 200266 | Oman | 52.1 | 0-15 | 6208 | - |

| Kingo and Ndawi, 200967 | Tanzania | - | 6-17 | 400 | - |

| Kumah et al., 201319 | Ghana | 46.6 | 12-15 | 2453 | 3.65 (2.94-4.47) |

| Li et al., 201568 | China | 51.5 | 0-19 | 22,148 | - |

| Limburg et al., 201220 | Vietnam | 52.2 | 0-15 | 28,800 | - |

| Lu et al., 200924 | Beijing | 52.2 | 4.41±1.09 (0-6) | 17,699 | - |

| Ma et al., 201613 | China | 54.0 | 3-10 | 8267 | 19.79 (18.93-20.66) |

| Maul et al., 200039 | Chile | 50.7 | 5-15 | 5303 | 15.72 (14.75-16.73) |

| Moraes Ibrahim et al., 201318 | Brazil | 51.0 | 12.4±1.6 (10-15) | 1590 | 5.72 (4.63-6.98) |

| Moser et al., 200269 | Equatorial Guinea | 47.9 | 0-19 | 812 | - |

| Murthy et al., 200236 | India | 51.9 | 7-15 | 6447 | 6.40 (5.79-7.05) |

| Naidoo et al., 200335 | South Africa | 49.3 | 5-15 | 4679 | 1.34 (1.03-1.71) |

| Newland et al., 199270 | Vanuatu | - | 6-19 | 483 | - |

| O’Donoghue et al., 201071 | Northern Ireland | 50.5 | 13.1±0.38 (12-13) | 661 | 12.85 (10.40-15.65) |

| Pai et al., 201121 | Sydney | 51.3 | 2-4 | 475 | - |

| Pan et al., 201612 | China | 53.3 | 4-6 | 713 | - |

| Park et al., 201416 | South Korea | 52.6 | 5-19 | 4394 | - |

| Paudel et al., 201415 | Vietnam | 46.1 | 12-15 | 2238 | 19.39 (17.77-21.09) |

| Pi et al., 201272 | Western China | 52.4 | 6-15 | 3079 | - |

| Pokharel et al., 200038 | Nepal | 51.7 | 5-15 | 4803 | 2.87 (2.41-3.38) |

| Premsenthil et al., 201373 | Malaysia | 49.0 | 4-6 | 400 | - |

| Raihan et al., 200574 | Bangladesh | 50.2 | 5-15 | 28,835 | - |

| Razavi et al., 201075 | Iran | - | 6-13 | 123 | - |

| Rezvan et al., 201276 | Iran | 41.5 | 11.2±2.4 (6-17) | 1547 | 2.20 (1.41-2.90) |

| Robaei et al., 200531 | Sydney | 50.6 | 6.7 (5-9) | 1738 | 1.32 (0.84-1.97) |

| Rustagi et al., 201277 | Delhi | 46.8 | 14.25 (11-18) | 1075 | 2.88 (1.96-4.06) |

| Salomão et al., 200978 | Brazil | 48.2 | 11-14 | 2440 | 4.83 (4.01-5.76) |

| Sapkota et al., 200825 | Kathmandu | 53.5 | 10-15 | 4282 | 18.63 (17.47-19.83) |

| Sewunet et al., 201479 | Ethiopia | 43.1 | 7-15 | 420 | 11.66 (8.75-15.12) |

| Shahriari et al., 200780 | Iran | 46.2 | 10-19 | 2307 | - |

| Sharma et al., 201781 | Haryana | 40.3 | 6-15 | 1265 | 2.68 (1.86-3.73) |

| Srivastava and Verma, 197882 | India | 54.4 | 0-14 | 7822 | - |

| Tabbara and Ross-Degnan, 198683 | Saudi Arabia | 50.4 | 0-19 | 4467 | - |

| Tananuvat et al., 200484 | Chiang Mai | - | 6-7 | 3467 | - |

| Taylor et al., 201085 | Australia | - | 5-15 | 1694 | - |

| Thulasiraj et al., 200334 | India | - | 6-19 | 5342 | - |

| Unsal et al., 200986 | Turkey | 53.7 | 10.52±2.2 (6-17) | 1606 | - |

| Varma et al., 201787 | United States | - | 3-5 | - | - |

| Vitale et al., 200630 | United States | 43.8 | 12-19 | 4564 | - |

| Wu et al., 201388 | China | 52.9 | 9.7±3.3 (4-18) | 6026 | 27.09 (25.97-28.24) |

| Xiao et al., 201189 | China | - | <16 | 23,675 | - |

| Yamamah et al., 201514 | Egypt | 50.6 | 10.7±3.1 (5-17) | 2070 | 29.42 (27.46-31.43) |

| Yekta et al., 201022 | Iran | 53.5 | 10.9±2.2 (7-15) | 1872 | 6.46 (4.96-7.96) |

| Zainal et al., 200290 | Malaysia | 47.0 | 0-9 | 4690 | - |

| Zerihun and Mabey, 199791 | Ethiopia | 50.5 | 0-19 | 4084 | - |

| Zhao et al., 200037 | China | 48.8 | 5-15 | 5884 | 12.81 (11.97-13.69) |

| MEPEDS Group 200923 | African-American Hispanic |

- | 2-6 | 1592 165 |

- |

| Abu-Shagra et al., 199142 | 11.86 (10.08-13.84) | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Medium risk | |

| Adhikari et al., 201443 | 0.1 (0.04-0.15) | - | 0.07 (0.02-0.12) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <6/60 |

Low risk |

| Ajaiyeoba et al., 200744 | 1.32 (0.74-2.18) | 0.17 (0.02-0.63) | VI: <6/18 either in one or both eyes BL: VA <3/60 |

Low risk | |

| Akogun 199245 | 8.12 (6.83-9.57) | - | 3.81 (2.92-4.87) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: VA <6/60 in the better eye |

High risk |

| A1 Faran et al., 199346 | - | 1.67 (1.14-2.35) | - | <6/18 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Alrasheed et al., 201647 | 4.40 (2.90-5.90) | 1.20 (0.30-2.70) | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Beiram 197148 | - | - | 0.071 (0.057-0.087) | VA ≤3/60 in the better eye | High risk |

| Bucher and Ijsselmuiden, 198849 | - | - | 0.006 (0.001-0.019) | PVA <3/60 in the better eye | High risk |

| Casson et al., 201250 | 1.90 (1.43-2.46) | - | - | <20/32 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Congdon et al., 200827 | 19.29 (17.53-21.14) | 0.47 (0.21-0.90) | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Dandona et al., 199940 | 2.86 (1.73-4.43) | - | - | <20/40 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Dandona et al., 200151 | - | - | 0.17 (0.05-0.40) | PVA <6/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Darge et al., 201752 | 5.82 (3.68-8.67) | - | - | ≤6/12 in the either eye | Low risk |

| Demissie and Solomon, 201153 | - | - | 0.05 (0.03-0.07) | PVA <6/60 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Dorairaj et al., 200854 | - | - | 0.11 (0.06-0.17) | BCVA <3/60 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Drews et al., 199255 | - | - | 0.068 (0.05-0.08) | BCVA <20/200 in the better eye | High risk |

| Farber 200356 | - | - | 14.41 (12.41-16.60) | VA ≤20/400 in the better eye | High risk |

| Feghhi et al., 200957 | - | 5.09 (4.26-6.03) | - | <20/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Flanagan et al., 200358 | - | 0.057 (0.03-0.08) | - | ≤6/18 in the better eye | High risk |

| Fotouhi et al., 200729 | 1.73 (1.40-2.11) | 0.25 (0.13-0.42) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Ghosh et al., 201259 | - | 0.19 (0.06-0.45) | - | <6/12 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Gilbert et al., 200826 | - | 0.14 (0.11-0.18) | - | <6/18 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Goh et al., 200432 | 10.08 (9.22-10.98) | 1.42 (1.10-1.81) | 2.033 (1.64-2.48) | VI: ≤20/40 in the better eye BL: ≤20/200 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Hashemi et al., 201711 | 1.30 (0.63-2.38) | 0.52 (0.14-1.33) | 0.78 (0.28-1.69) | VI: ≤20/60 in the better eye BL: VA <20/400 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| He et al., 201417 | 11.25 (10.63-11.91) | 0.63 (0.48-0.81) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| He et al., 200728 | 16.58 (15.11-18.13) | 0.45 (0.22-0.81) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| He et al., 200433 | 10.25 (9.36-11.19) | 0.61 (0.41-0.89) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Heijthuijsen et al., 201360 | 2.30 (1.89-2.77) | - | 0.81 (0.57-1.12) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <3/60 in the better eye |

Medium risk |

| Jamali et al., 200961 | - | - | - | <6/12 in either eye | Medium risk |

| Johnson and Minassian, 198962 | - | - | 0.11 (0.04-0.24) | VA<3/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Kaphle et al., 201663 | 3.60 (0.43-12.31) | - | 1.78 (0.04-9.55) | VI: VA <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <3/60 in the better eye |

Medium risk |

| Kedir and Girma, 201064 | 1.75 (0.84- 3.20) | 1.40 (0.61-2.74) | - | <6/18 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Kemmanu et al., 201565 | - | - | 0.077 (0.046-0.12) | BCVA <3/60 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Khandekar et al., 200266 | - | - | 0.08 (0.02-0.18) | PVA<3/60 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Kingo and Ndawi, 200967 | 9.50 (6.81-12.80) | - | - | VI: VA<6/18 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Kumah et al., 201319 | 3.53 (2.83-4.34) | 0.41 (0.19-0.75) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Li et al., 201568 | - | 0.07 (0.04-0.11) | 0.02 (0.007-0.05) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: BCVA <3/60 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Limburg et al., 201220 | - | - | 0.07 (0.05-0.11) | PVA <3/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Lu et al., 200924 | 0.42 (0.33-0.53) | - | - | <6/18 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Ma et al., 201613 | 15.53 (14.75-16.33) | 1.69 (1.42-1.99) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Maul et al., 199939 | 14.57 (13.63-15.55) | 7.29 (6.61-8.03) | - | <20/40 in at least one eye | Low risk |

| Moraes Ibrahim et al., 201318 | 2.83 (2.07-3.76) | 0.81 (0.43-1.39) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Moser et al., 200269 | - | - | 0.61 (0.20-1.43) | VA <3/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Murthy et al., 200136 | 4.85 (4.32-5.43) | 0.81 (0.59-1.06) | - | <20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Naidoo et al., 200335 | 1.17 (0.88-1.52) | 0.32 (0.17-0.52) | - | VA ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Newland et al., 199270 | - | - | 0.21 (0.005-1.14) | VA <6/18 in the better eye | High risk |

| O’Donoghue et al., 201071 | 3.17 (1.97-4.81) | - | - | <6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Pai et al., 201121 | 6.10 (4.12-8.65) | - | - | <20/50 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Pan et al., 201612 | 6.59 (4.88-8.66) | - | - | <20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Park et al., 201416 | 6.12 (5.43-6.87) | - | 0.25 (0.12-0.44) | VI: <20/60 in the better eye BL: VA <20/400 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Paudel et al., 201415 | 12.19 (10.87-13.62) | - | 0.26 (0.09-0.58) | VI: VA ≤6/12 in the better eye BL: PVA ≤6/120 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Pi et al., 201272 | 7.69 (6.78-8.69) | - | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Pokharel et al., 200038 | 2.83 (2.38-3.34) | 1.35 (1.04-1.72) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Premsenthil et al., 201373 | 5.0 (3.08-7.61) | - | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Raihan et al., 200574 | - | - | 0.06 (0.04-0.11) | PVA <3/60 in the better eye | High risk |

| Razavi et al., 201075 | - | - | 17.88 (11.56-25.81) | VA <3/60 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Rezvan et al., 201276 | 1.0 (0.59-1.67) | 0.25 (0.07-0.66) | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Robaei et al., 200531 | 0.86 (0.48-1.41) | - | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Rustagi et al., 201277 | - | - | 0.93 (0.44-1.70) | VI: <20/60 in the better eye BL: VA <20/200 in the better eye |

Medium risk |

| Salomão et al., 200978 | 2.70 (2.09-3.42) | 0.40 (0.19-0.75) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Sapkota et al., 200825 | 9.08 (8.24-9.98) | 0.86 (0.60- 1.18) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Sewunet et al., 201479 | - | 6.42 (4.27-9.21) | - | <20/40 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Shahriari et al., 200780 | - | 1.51 (0.98-2.04) | <20/60 using a pinhole | Low risk | |

| Sharma et al., 201781 | - | - | - | ≤6/18 in the better eye | High risk |

| Srivastava and Verma, 197882 | - | - | 0.14 (0.07-0.25) | PVA <3/60 in the better eye | High risk |

| Tabbara and Ross-Degnan, 198683 | 11.59 (10.67-12.57) | - | 2.39 (1.96-2.88) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <3/60 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Tananuvat et al., 200484 | 8.68 (7.76- 9.66) | - | - | ≤20/40 at least one eye | Medium risk |

| Taylor et al., 201085 | 1.68 (1.12-2.43) | - | 0.18 (0.03-0.52) | VI: <6/12 in the better eye BL: PVA<6/60 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Thulasiraj et al., 200334 | 0.73 (0.52-0.99) | 0.48 (0.32-0.72) | 0.07 (0.02-0.19) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA<3/60 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Unsal et al., 200986 | 1.68 (1.11-2.43) | - | - | <20/40 in the better eye | High risk |

| Varma et al., 201787 | 1.50 (1.20-1.80) | - | - | <20/50 or 20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Vitale et al., 200630 | 9.70 (8.86-10.60) | - | - | ≤20/50 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Wu et al., 201388 | - | 0.31 (0.19-0.49) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Xiao et al., 201189 | - | - | 0.02 (0.006-0.049) | PVA <3/60 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Yamamah et al., 201514 | - | - | - | ≤6/9 in the better eye | Medium risk |

| Yekta et al., 201022 | 1.49 (0.82-2.15) | 0.90 (0.30-2.74) | - | ≤6/12 in the better eye | Low risk |

| Zainal et al., 200290 | 0.44 (0.27-0.68) | - | 0.04 (0.005-0.15) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <3/60 in the better eye |

Low risk |

| Zerihun and Mabey, 199791 | 0.18 (0.04-0.53) | - | 0.07 (0.01-0.21) | VI: <6/18 in the better eye BL: PVA <3/60 in the better eye |

High risk |

| Zhao et al., 200037 | 10.92 (10.14-11.75) | 1.75 (1.43-2.11) | - | ≤20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| MEPEDS Group 200923 | 2.76 (2.01-3.69) | 0.78 (0.41-1.33) | - | <20/50 or 20/40 in the better eye | Low risk |

| 2.47 (1.77-3.35) | 0.71 (0.36-1.22) |

SS: Sample size, UCVA: Uncorrected visual acuity, PVA: Presenting visual acuity, BCVA: Best corrected visual acuity, CI: Confidence interval, VI: Visual impairment, BL: Blindness, VA: Visual acuity

Among the selected articles, the studies by Razavi et al.75 in Iran with 123 people and Beiram84 with 127,426 people in Sudan had the smallest and the largest sample sizes, respectively.

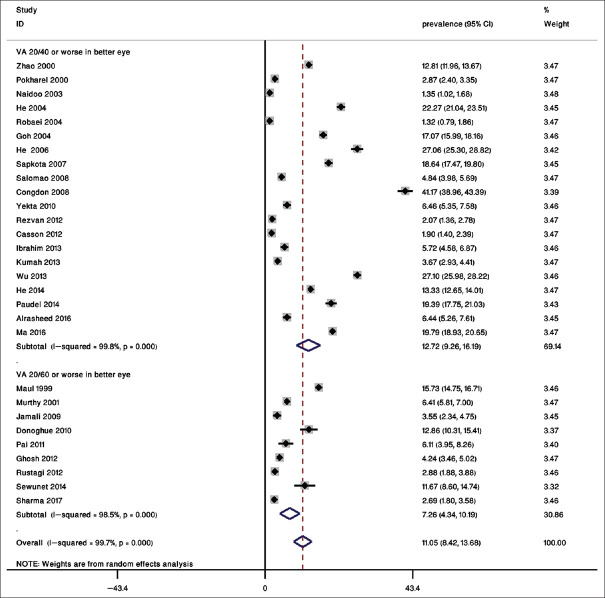

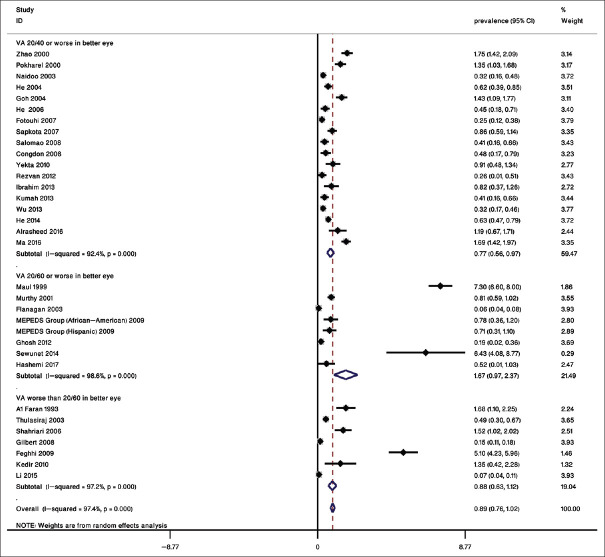

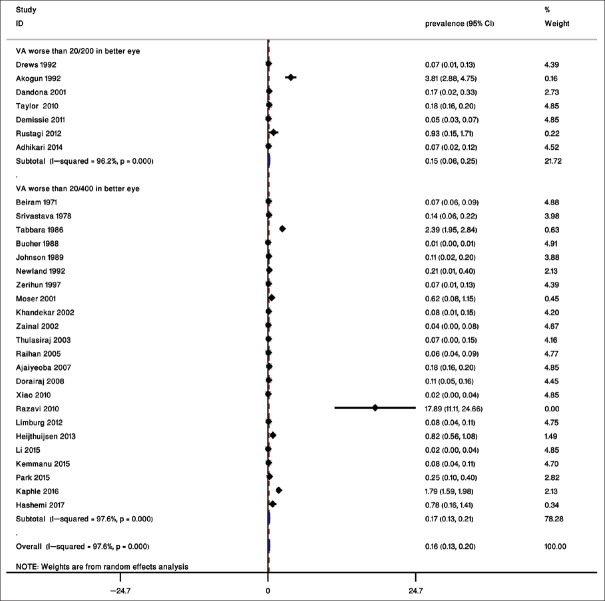

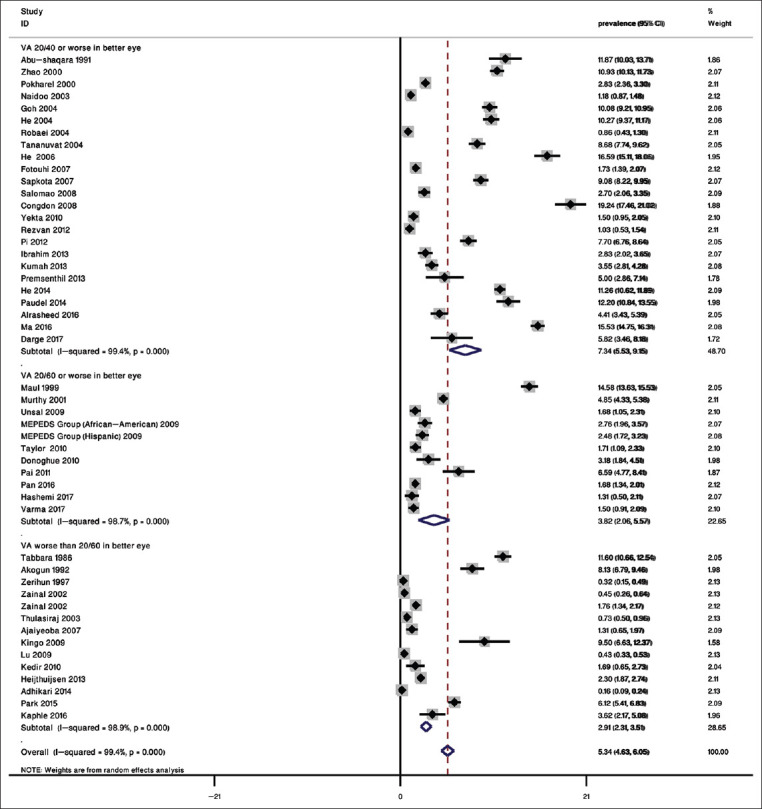

The overall prevalence of VI was 12.72% (95% CI: 9.26%–16.19%) based on a UCVA of 20/40 or worse in the better eye, and 7.26% (95% CI: 4.34%–10.19%) based on a UCVA of 20/60 or worse in the better eye [Figure 2]. The prevalence was 7.34% (95% CI: 5.53%–9.15%) based on a PVA of 20/40 or worse in the better eye and 3.82% (95% CI: 2.06%–5.57%) with a PVA of 20/60 or worse in the better eye, and 2.91% (95% CI: 2.31%–3.51%) based on a PVA worse than 20/60 in the better eye [Figure 3]. The prevalence of VI based on a BCVA of 20/40 or worse in the better eye was 0.77% (95% CI: 0.56%–0.97%), 1.67% (95% CI 0.97%–2.37%) based on a BCVA of 20/60 or worse in the better eye, and 0.88% (95% CI: 0.63%–1.12%) based on a BCVA worse than 20/60 in the better eye [Figure 4].

Figure 2.

Overall prevalence and subgroups of uncorrected visual acuity based on uncorrected visual acuity

Figure 3.

Overall prevalence and subgroups of presenting visual acuity (PVA) based on PVA

Figure 4.

Overall prevalence and subgroups of best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) based on BCVA

Based on criteria worse than 20/200 in better eye and worse than 20/400 in the better eye, the blindness prevalence was 0.15% (95% CI: 0.06%-0.25%) and 0.17% (95% CI: 0.13%-0.21%), respectively [Figure 5]. Table 2 summarizes the prevalence of UCVA, BCVA, PVA VI, and blindness in the six regions of the WHO. The highest rate of VI based on UCVA of 20/40 or worse in the better eye was 20.10% (95% CI: 13.75%–26.45%) in the Pacific Region, and based on UCVA of <20/60 in the better eye was 15.72% (95% CI: 14.74%–16.70%) in the Americas. The highest prevalence of VI based on PVA of 20/40 or worse in the better eye, 20/60 or worse in the better eye, and worse than 20/60 in the better eye in the Pacific Region was 10.87% (95% CI: 7.26%–14.48%), 8.03% (95% CI 1.00% -20.84%) in the Americas, and 11.59 (95% CI: 10.65–12.53) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, respectively. The highest prevalence of VI based on a BCVA of 20/40 was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.54–1.27) in the Pacific Region. The highest rates of blindness were 1.91 (95.1% CI: 1.78–5.58) in the African Region based on worse than 20/200 and 1.94 (95% CI: 0.27%–3.61%) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region with criteria worse than 20/400.

Figure 5.

Overall prevalence and subgroups of blindness

Table 2.

Prevalence of visual impairment and blindness in the six regions of the World Health Organization

| WHO region | UCVA % (95% CI) | PVA % (95% CI) | BCVA % (95% CI) | Blindness % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| ≤20/40 in better eye | ≤20/60 in better eye | ≤20/40 in better eye | ≤20/60 in better eye | <20/60 in better eye | ≤20/40 in better eye | ≤20/60 in better eye | <20/200 in better eye | <20/400 in better eye | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 4.24 (1.00-8.55) | 7.47 (1.00-15.43) | 3.62 (1.81-5.44) | 1.54 (1.04-2.04) | 11.59 (10.65-12.53) | 0.41 (0.12-0.71) | 3.36 (1.00-9.14) | - | 1.94 (0.27-3.61) |

| Americas | 5.19 (4.34-6.04) | 15.72 (14.74-16.70) | 2.75 (2.25-3.25) | 8.03 (1.00-20.84) | - | 0.57 (0.18-0.96) | 7.29 (6.59-7.99) | 0.07 (0.05-0.08) | - |

| Africa | 3.76 (1.09-6.44) | - | 3.57 (1.58-5.56) | - | 3.48 (1.96-5.01) | 0.55 (0.19-0.91) | 0.78 (0.36-1.21) | 1.91 (1.78-5.58) | 0.11 (0.04-0.16) |

| Western Pacific | 20.10 (13.75-26.45) | 6.10 (3.95-8.25) | 10.87 (7.26-14.48) | 2.90 (1.42-4.37) | 2.11 (0.97-3.23) | 0.91 (0.54-1.27) | - | 0.17 (0.01-0.37) | 0.05 (0.02-0.08) |

| South-east Asia | 7.77 (1.15-14.39) | 4.07 (2.23-5.93) | 6.85 (2.29-11.42) | 4.85 (4.33-5.38) | 0.44 (0.01-0.99) | 1.11 (0.63-1.58) | 0.49 (0.1-1.096) | 0.21 (0.01-0.43) | 0.08 (0.06-0.09) |

| European | - | 12.85 (10.31-15.41) | - | 2.69 (2.18-3.21) | - | - | 0.35 (0.28-0.98) | - | - |

UCVA: Uncorrected visual acuity, PVA: Presenting visual acuity, BCVA: Best corrected visual acuity, CI: Confidence interval, WHO: World Health Organization

Table 3 presents the prevalence of the causes of VI and blindness. In the selected articles, refractive errors, with a prevalence of 77.20% (95% CI: 73.40%–81.00%), were the most common cause of VI. Amblyopia, retinal disorders, congenital cataract, and corneal opacities were other causes of visual impairment, and cataract, glaucoma, and refractive errors were the most common causes of blindness.

Table 3.

The proportion (%) of causes of visual impairment and blindness in the reviewed articles

| 1st author | Causes visual impairment (%) | Causes of blindness (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Refractive errors | Amblyopia | Congenital cataract | Corneal opacity | Retinal disorder | Glaucoma | Refractive errors | Cataract | Glaucoma | |

| Al Faran et al., 199346 | 67.9 | 1.3 | 20.6 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 52.6 | 5.3 |

| Ajaiyeoba et al., 200744 | 66.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adhikari et al., 201443 | 1.9 | - | - | - | |||||

| Alrasheed et al., 201647 | 57.0 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 13.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Beiram, 197148 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.2 | 10.9 |

| Darge et al., 201752 | 77.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Demissie and Solomon, 201153 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17.0 | 33.0 | 11.0 |

| Dorairaj et al., 200854 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28.7 | - |

| Farber, 200356 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.1 | 2.7 | |

| Fotouhi et al., 200729 | 87.3 | 13.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Gilbert et al., 200826 | - | 30.0 | 3.3 | 6.6 | 36.6 | - | - | - | - |

| Goh et al., 200532 | 89.5 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| He et al., 200728 | 96.8 | 1.4 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.36 | - | - | - | - |

| He et al., 200433 | 95.6 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| He et al., 201417 | 89.5 | 10.1 | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ibrahim et al., 201318 | 89.0 | 5.5 | - | - | 4.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Jamali et al., 200961 | 62.1 | 37.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kedir and Girma 201464 | 54.0 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 8.1 | 10.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Kingo and Ndawi, 200967 | 31.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kumah et al., 201319 | 88.8 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 2.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Lu et al., 200924 | 80.3 | 4.2 | 4.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Maul et al., 200039 | 62.1 | 9.0 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 2.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Murthy et al., 200236 | 80.9 | 6.4 | 0.37 | 1.3 | 5.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Naidoo et al., 200335 | 66.4 | 9.4 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 10.9 | - | - | - | - |

| Paudel et al., 201415 | 92.7 | 2.2 | 0.7 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Pi et al., 201272 | 86.1 | 9.7 | 0.42 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pokharel et al., 200038 | 55.1 | 12.3 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 5.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Robaei et al., 200531 | 69.0 | 22.5 | - | - | 2.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Salomão et al., 200978 | 76.8 | 11.4 | - | - | 5.9 | - | - | - | - |

| Sapkota et al., 200825 | 93.3 | 1.77 | 0.10 | - | 1.25 | - | - | - | - |

| Sewunet et al., 201479 | 87.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Srivastava and Verma, 197882 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32.0 | 25.0 |

| Taylor et al., 201085 | 56.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 33.0 | - | - |

| Thulasiraj et al., 200334 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.2 |

| Wu et al., 201388 | 96.6 | 2.2 | - | 0.05 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yamamah et al., 201514 | - | 0.4 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Zainal et al., 200290 | 48.3 | - | 35.9 | 2.5 | 2.8 | - | - | - | - |

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to generate a more accurate estimate of the global prevalence of VI in children using credible population-based studies. We also presented the prevalence of VI and blindness based on different definitions. Studies in the under-20 year's old groups and especially studies in the under-15 year's old groups were the most important reason for choosing 20 years-old as a cut-off. Our results indicated that the lowest prevalence of BCVA VI was 0.057% in the study by Flanagan et al.58 in Ireland and the highest prevalence was 7.29% in a study by Maul et al. in Chile.39 The lowest and highest prevalence of VI based on PVA was, respectively, 19.29% in the study by Adhikari et al.43 and 0.1% in the study by Congdon et al.27 Despite the lower prevalence of VI in children compared to adults (3.82% versus 35.8%10), the number of years lost due to disabilities caused by vision impairment in children imposes a large burden on societies, especially in less developed countries. In a systematic review, Köberlein et al.92 reported that the direct costs of VI included hospitalization, utilization of medical services, purchase of medical products, and the recurrence of VI. They showed that in several population-based studies using representative populations in the United States, the annual cost was 12,175-14,029 dollars for a patient with moderate VI, and 14,882–24,180 dollars for a blind person.92 The high cost of treatment and follow-up on the one hand, and the mental burden, the educational failure, and in general, the reduced quality of life for children on the other hand justify the importance of determining estimates of the trend of the prevalence of VI and its causes in children.

In addition to imposing costs, the burden of disease is an important issue. In a retrospective study, examining data from 195 countries between 1995 and 2017, the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) number of refractive errors in school children was higher than preschool and teenagers.93

Determining the prevalence of VI and its most important causes are necessary to apply policies and strategies to prevent and eliminate the preventable causes of VI. Our findings showed that refractive errors were the most common cause of VI in most articles reviewed in this meta-analysis, such that 29 articles described refractive errors as the cause or one of the causes of VI with rates ranging between 48.3% in the study by Zainal et al.90 and 96.8% in the study by He et al.28 Failure to use the protocol recommended for Refractive Error Study in Children (the RESC Protocol which suggests the use of cycloplegic refraction) in some studies has led to different estimates of the prevalence of refractive errors. In the RESC study, the following definition is defined to determine the refractive error Cycloplegic Refraction: In eyes with successful cycloplegia, refraction is performed with either an autorefractor or retinoscope. Autorefraction is carried out according to the manufacturer instruction manual, including daily calibration. Retinoscopy is carried out using a streak retinoscope in a semi-dark room, with the examiner at a distance of 0.75 meters and a +1.50 diopter lens in the trial frame. Therefore, not using the same definition in studies has led to different estimates in the reports. In studies on similar age groups in geographic regions close to each other, different definitions of refractive errors have been used, and the prevalence of refractive errors, as a cause of VI, is significantly different.51 Another cause of the difference in the prevalence of refractive errors can be the difference between the studied age groups in the reviewed articles. In studies conducted in age groups over 7 years, the refractive errors as a cause of VI is higher than in studies where the average age of the participants is <7 years. In studies such as those by Sapkota et al.25 and Paudel et al.15 where the average age is 10 years and older, over 90% of VI is due to refractive errors. The age-related increase in the prevalence of myopia is one of the major causes of the high prevalence of refractive errors in studies that sampled older age groups. The meta-analysis by Rudnicka et al.94 in the Middle East Region suggested a significant age-related increase in the prevalence of myopia, such that rates changed from 3.5% in the 5-year age group to more than 47% in the 18-year age group. In a trend analysis from 1990 to 2017, the prevalence of children aged 1–14 years with refractive disorders was 1.8% (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 1.5–2.1). In school children, teenagers, and preschool children, the prevalence was 2.1% (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 1.5–2.8), 2% (95% UI: 1.4–2.7) and 1.6% (95% UI: 1.2–2), respectively.93 Another cause of difference in the results of these studies can be race and ethnic differences, and thus, genetic and lifestyle differences. In the meta-analysis by Rudnicka et al.,94 the prevalence of myopia in the East Asian Region was more than 80% while it was <5.5% in black African children of the same age group. This racial difference has also been observed with other causes of VI such as amblyopia.

According to our findings, amblyopia is the second leading cause of VI after refractive errors in the reviewed papers. In countries where such screening programs have been in effect for a longer time, the prevalence of amblyopia, as one of the most important preventable causes of VI has been reported. In the absence of apparent strabismus, amblyopia is usually not easily identifiable in children, thus, only properly designed and implemented screening programs by trained people will be effective for the timely diagnosis of amblyopia. Otherwise, childhood amblyopia will continue until they reach adulthood and will lead to a decline in the quality of life in adolescence and older age. Findings by Høeg et al.95 show that the prevalence of amblyopia in the Danish 20 to 29-year old population, who had been screened by the national screening program for children and treated in childhood was 0%, and in cohorts over 50 years of age, the rate was more than 1.5%. This significant difference clearly shows the impact of the implementation and expansion of screening program in recent years compared to previous years.

Based on our findings, the overall global prevalence of blindness in the under 20-year population was 0.17%. The definition by the WHO is based on BCVA <0.05 (20/400). The prevalence of blindness in the studies using this criterion was estimated at 4.5%. These definitions in different countries have always led to various estimates of blindness. For example, blindness is defined as a visual acuity of ≤0.02 (20/1000) in Germany and ≤0.05 in Israel.56,96 Rosenberg and Klie97 have shown that changing the definition of blindness from ≤0.1 to <0.1 can reduce the diagnosis of blindness by up 32%. Establishing national registries for the blind is very important and effective in determining the prevalence and causes of blindness. Unfortunately, few countries have established reliable registries so far, and in other countries, relevant information, such as the prevalence and causes of blindness, is generated from surveys or studies in schools for the blind, and due to methodological errors in these studies, the results are interpreted with caution. This lack of consistency in the definition and diagnosis of blindness and the lack of registries has led to overestimation or underestimation of global blindness. Despite these differences, we determined the prevalence of blindness based on different diagnostic criteria by referring to the most reliable survey articles and excluding studies performed at schools for the blind. Studies have shown that despite the reduction in age-standardized prevalence of blindness and VI over the past 20 years, based on corrected vision, cataract is still the most important cause of blindness in the world, such that in 2015, Khairallah et al.98 reported that more than 33% of the world's blindness was due to cataract between 1990 and the end of 2010. In our study, cataract was the most common cause of blindness and the third most common cause of VI in the reviewed studies. Due to lack of information such as nonreporting standard error or CI, meta-analysis of other causes was not possible for the authors. In 2002, Zainal et al.90 reported the highest prevalence of cataract (3.92%) in children younger than 19 years of age. In determining the cause of blindness and comparing it among different populations, the study of the economic status of the countries and the availability of public health services plays an important role. In countries where access to cataract surgery due to lack of equipment, lack of experienced specialists, and financial inability of people for access to surgery, cataract plays a major role in blindness. In light of this discussion, to reduce preventable blindness, it is necessary to conduct nationwide surveys to determine the existence and availability of surgical facilities and to give priority to raising public awareness for the utilization of healthcare services.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1: Search methods

The search strategy was created using the following phrase

(Vision impairment or Low Vision or Visual Disorders or Visual Disorder or Visual Impairments or Vision Disability or Visual disability or Vision Disabilities or Day Blindness or Reduced Vision or Subnormal Vision or Diminished Vision or vision impaired or Visual defect or Visual loss or Visually impaired or Visually impaired persons or blindness or Acquired Blindness or Complete Blindness) and (prevalence or epidemiology or cross-sectional stud* or observational stud* or survey). Three international databases including Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed were searched for publications indexed up to January 2018. To access more articles and to ensure the correctness of the search strategy in the databases, we also reviewed the reference lists of the selected articles as well as Google Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solebo AL, Teoh L, Rahi J. Epidemiology of blindness in children. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:853–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. (1997) Strategies for the prevention of blindness in national programmers: a primary health care approach. 2nd ed. [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 27]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41887.

- 3.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blindness and Visual Impairment; 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 05]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment .

- 5.Courtright P, Hutchinson AK, Lewallen S. Visual impairment in children in middle- and lower-income countries. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1129–34. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS British Childhood Visual Impairment Interest Group. Improving detection of blindness in childhood: The British Childhood Vision Impairment study. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e895–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong L, Fry M, Al-Samarraie M, Gilbert C, Steinkuller PG. An update on progress and the changing epidemiology of causes of childhood blindness worldwide. J AAPOS. 2012;16:501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahi JS, Cable N British Childhood Visual Impairment Study Group. Severe visual impairment and blindness in children in the UK. Lancet. 2003;362:1359–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e130–43. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Saatchi M, Ostadimoghaddam H, Yekta A. Visual impairment and blindness in a population-based study of Mashhad, Iran. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2018;30:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan CW, Chen X, Gong Y, Yu J, Ding H, Bai J, et al. Prevalence and causes of reduced visual acuity among children aged three to six years in a metropolis in China. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36:152–7. doi: 10.1111/opo.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Y, Qu X, Zhu X, Xu X, Zhu J, Sankaridurg P, et al. Age-specific prevalence of visual impairment and refractive error in children aged 3-10 years in Shanghai, China. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:6188–96. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamah GA, Talaat Abdel Alim AA, Mostafa YS, Ahmed RA, Mohammed AM. Prevalence of visual impairment and refractive errors in children of south Sinai, Egypt. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:246–52. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1056811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paudel P, Ramson P, Naduvilath T, Wilson D, Phuong HT, Ho SM, et al. Prevalence of vision impairment and refractive error in school children in Ba Ria-Vung Tau province, Vietnam. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:217–26. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SH, Lee JS, Heo H, Suh YW, Kim SH, Lim KH, et al. A nationwide population-based study of low vision and blindness in South Korea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56:484–93. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J, Lu L, Zou H, He X, Li Q, Wang W, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and rate of wearing spectacles in schools for children of migrant workers in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1312. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moraes Ibrahim F, Moraes Ibrahim M, Pomepo de Camargo JR, Veronese Rodrigues Mde L, Scott IU, Silva Paula J. Visual impairment and myopia in Brazilian children: A population-based study. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:223–7. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31828197fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumah BD, Ebri A, Abdul-Kabir M, Ahmed AS, Koomson NY, Aikins S, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in private school children in Ghana. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:1456–61. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limburg H, Gilbert C, Hon DN, Dung NC, Hoang TH. Prevalence and causes of blindness in children in Vietnam. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai AS, Wang JJ, Samarawickrama C, Burlutsky G, Rose KA, Varma R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for visual impairment in preschool children the Sydney Paediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Shiraz, Iran. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38:242–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study G. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in African-American and Hispanic preschool children: The multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1990–2000.e1991. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Q, Zheng Y, Sun B, Cui T, Congdon N, Hu A, et al. A population-based study of visual impairment among pre-school children in Beijing: The Beijing study of visual impairment in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:1075–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sapkota YD, Adhikari BN, Pokharel GP, Poudyal BK, Ellwein LB. The prevalence of visual impairment in school children of upper-middle socioeconomic status in Kathmandu. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:17–23. doi: 10.1080/09286580701772011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert CE, Ellwein LB Refractive Error Study in Children Study Group. Prevalence and causes of functional low vision in school-age children: Results from standardized population surveys in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:877–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Congdon N, Wang Y, Song Y, Choi K, Zhang M, Zhou Z, et al. Visual disability, visual function, and myopia among rural Chinese secondary school children: The Xichang Pediatric Refractive Error Study (X-PRES) – Report 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2888–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He M, Huang W, Zheng Y, Huang L, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:287–92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitale S, Cotch MF, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States. JAMA. 2006;295:2158–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robaei D, Rose K, Ojaimi E, Kifley A, Huynh S, Mitchell P. Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population-based sample of 6-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He M, Zeng J, Liu Y, Xu J, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern china. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:793–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thulasiraj RD, Nirmalan PK, Ramakrishnan R, Krishnadas R, Manimekalai TK, Baburajan NP, et al. Blindness and vision impairment in a rural south Indian population: The Aravind Comprehensive Eye Survey. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1491–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, Govender P, Holden BA, Pokharel GP, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3764–70. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, Muñoz SR, Pokharel GP, Sanga L, et al. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: Results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:427–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: Results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:436–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: Results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:445–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, McCarty CA, Srinivas M, Mandal P, et al. Burden of moderate visual impairment in an urban population in southern India. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:497–504. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45:247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abu-Shagra S, Kazi G, Al-Rushood A S. Y. Prevelance and causes of visual acuity defect in male school children in Al-Khobar area. Saudi Med J. 1991;12:397–402. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adhikari S, Shrestha MK, Adhikari K, Maharjan N, Shrestha UD. Factors associated with childhood ocular morbidity and blindness in three ecological regions of Nepal: Nepal pediatric ocular disease study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajaiyeoba AI, Isawumi MA, Adeoye AO, Oluleye TS. Pattern of eye diseases and visual impairment among students in southwestern Nigeria. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:287–92. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akogun OB. Eye lesions, blindness and visual impairment in the Taraba river valley, Nigeria and their relation to onchocercal microfilariae in skin. Acta Trop. 1992;51:143–9. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(92)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al Faran MF, Al-Rajhi AA, Al-Omar OM, Al-Ghamdi SA, Jabak M. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in the south western region of Saudi Arabia. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17:161–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00942931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alrasheed SH, Naidoo KS, Clarke-Farr PC. Prevalence of visual impairment and refractive error in school-aged children in South Darfur State of Sudan. Afr Vision Eye Health. 2016;75:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beiram MM. Blindness in the Sudan: Prevalence and causes in Blue Nile Province. Bull World Health Organ. 1971;45:511–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bucher PJ, Ijsselmuiden CB. Prevalence and causes of blindness in the northern Transvaal. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:721–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.10.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casson RJ, Kahawita S, Kong A, Muecke J, Sisaleumsak S, Visonnavong V. Exceptionally low prevalence of refractive error and visual impairment in schoolchildren from Lao People's Democratic Republic. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2021–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dandona L, Dandona R, Srinivas M, Giridhar P, Vilas K, Prasad MN, et al. Blindness in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:908–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darge HF, Shibru G, Mulugeta A, Dagnachew YM. The prevalence of visual acuity impairment among school children at Arada Subcity Primary Schools in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:9326108. doi: 10.1155/2017/9326108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demissie BS, Solomon AW. Magnitude and causes of childhood blindness and severe visual impairment in Sekoru District, Southwest Ethiopia: A survey using the key informant method. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorairaj SK, Bandrakalli P, Shetty C, Vathsala R, Misquith D, Ritch R. Childhood blindness in a rural population of southern India: Prevalence and etiology. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:176–82. doi: 10.1080/09286580801977668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drews CD, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Murphy CC, Decoufle P. Legal blindness among 10-year-old children in Metropolitan Atlanta: Prevalence, 1985 to 1987. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1377–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farber MD. National registry for the blind in Israel: Estimation of prevalence and incidence rates and causes of blindness. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:267–77. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.4.267.15910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feghhi M, Khataminia G, Ziaei H, Latifi M. Prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in Khuzestan province, Iran. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2009;4:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flanagan NM, Jackson AJ, Hill AE. Visual impairment in childhood: Insights from a community-based survey. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29:493–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay U, Maji D, Bhaduri G. Visual impairment in urban school children of low-income families in Kolkata, India. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:163–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.99919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heijthuijsen AA, Beunders VA, Jiawan D, de Mesquita-Voigt AM, Pawiroredjo J, Mourits M, et al. Causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in children in the Republic of Suriname. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:812–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jamali P, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Younesian M, Jafari A. Refractive errors and amblyopia in children entering school: Shahrood, Iran. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:364–9. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181993f42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson GJ, Minassian DC. Prevalence of blindness and eye disease: Discussion paper. J R Soc Med. 1989;82:351–4. doi: 10.1177/014107688908200613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaphle D, Gyawali R, Kandel H, Reading A, Msosa JM. Vision impairment and ocular morbidity in a refugee population in Malawi. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:188–93. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kedir J, Girma A. Prevalence of refractive error and visual impairment among rural school-age children of Goro District, Gurage Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24:353–8. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v24i4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kemmanu V, Hegde K, Giliyar SK, Shetty BK, Kumaramanickavel G, McCarty CA. Prevalence of childhood blindness and ocular morbidity in a rural pediatric population in southern India: The Pavagada pediatric eye disease study-1. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:185–92. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1090003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khandekar R, Mohammed AJ, Negrel AD, Riyami AA. The prevalence and causes of blindness in the Sultanate of Oman: The Oman Eye Study (OES) Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:957–62. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kingo AU, Ndawi BT. Prevalence and causes of low vision among schoolchildren in Kibaha District, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2009;11:111–5. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v11i3.47695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li T, Du L, Du L. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in Shanxi province, China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:239–45. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1009119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moser CL, Martín-Baranera M, Vega F, Draper V, Gutiérrez J, Mas J. Survey of blindness and visual impairment in Bioko, Equatorial Guinea. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:257–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Newland HS, Harris MF, Walland M, McKnight D, Galbraith JE, Iwasaki W, et al. Epidemiology of blindness and visual impairment in Vanuatu. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70:369–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O'Donoghue L, McClelland JF, Logan NS, Rudnicka AR, Owen CG, Saunders KJ. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in Northern Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1155–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pi LH, Chen L, Liu Q, Ke N, Fang J, Zhang S, et al. Prevalence of eye diseases and causes of visual impairment in school-aged children in Western China. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:37–44. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Premsenthil M, Manju R, Thanaraj A, Rahman SA, Kah TA. The screening of visual impairment among preschool children in an urban population in Malaysia; the Kuching pediatric eye study: A cross sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raihan A, Rahmatullah S, Arefin MH, Banu T. International Congress Series 1282. London, UK. Elsevier: 2005. Prevalence of significant refractive error, low vision and blindness among children in Bangladesh; pp. 433–7. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Razavi H, Kuper H, Rezvan F, Amelie K, Mahboobi-Pur H, Oladi MR, et al. Prevalence and causes of severe visual impairment and blindness among children in the lorestan province of Iran, using the key informant method. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:95–102. doi: 10.3109/09286581003624954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rezvan F, Khabazkhoob M, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors among school children in Northeastern Iran. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rustagi N, Uppal Y, Taneja DK. Screening for visual impairment: Outcome among schoolchildren in a rural area of Delhi. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:203–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.95872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salomão SR, Mitsuhiro MR, Belfort R., Jr Visual impairment and blindness: An overview of prevalence and causes in Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81:539–49. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sewunet SA, Aredo KK, Gedefew M. Uncorrected refractive error and associated factors among primary school children in Debre Markos District, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shahriari HA, Izadi S, Rouhani MR, Ghasemzadeh F, Maleki AR. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness in Sistan-va-Baluchestan Province, Iran: Zahedan Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:579–84. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.105734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharma A, Maitreya A, Semwal J, Bahadur H. Ocular morbidity among school children in Uttarakhand: Himalayan State of India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med. 2017;10:149–53. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Srivastava RN, Verma BL. An epidemiological study of blindness in an Indian rural community. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978) 1978;32:131–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tabbara KF, Ross-Degnan D. Blindness in Saudi Arabia. JAMA. 1986;255:3378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tananuvat N, Manassakorn A, Worapong A, Kupat J, Chuwuttayakorn J, Wattananikorn S. Vision screening in schoolchildren: Two years results. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:679–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taylor HR, Xie J, Fox S, Dunn RA, Arnold AL, Keeffe JE. The prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous Australians: The National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Med J Aust. 2010;192:312–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Unsal A, Ayranci U, Tozun M. Vision screening among children in primary schools in a district of western Turkey: An epidemiological study. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:976–81. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Varma R, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Jiang X. Visual impairment in preschool children in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2060. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:610–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu JF, Bi HS, Wang SM, Hu YY, Wu H, Sun W, et al. Refractive error, visual acuity and causes of vision loss in children in Shandong, China. The Shandong Children Eye Study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xiao B, Fan J, Deng Y, Ding Y, Muhit M, Kuper H. Using key informant method to assess the prevalence and causes of childhood blindness in Xiu'shui County, Jiangxi Province, Southeast China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18:30–5. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.528138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zainal M, Ismail SM, Ropilah AR, Elias H, Arumugam G, Alias D, et al. Prevalence of blindness and low vision in Malaysian population: Results from the National Eye Survey 1996. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:951–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.9.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zerihun N, Mabey D. Blindness and low vision in Jimma Zone, Ethopia: Results of a population-based survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1997;4:19–26. doi: 10.3109/09286589709058057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Köberlein J, Beifus K, Schaffert C, Finger RP. The economic burden of visual impairment and blindness: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003471. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abdolalizadeh P, Chaibakhsh S, Falavarjani KG. Global burden of paediatric vision impairment: A trend analysis from 1990 to 2017. Eye (Lond) 2021;35:2136–45. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01598-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rudnicka AR, Kapetanakis VV, Wathern AK, Logan NS, Gilmartin B, Whincup PH, et al. Global variations and time trends in the prevalence of childhood myopia, a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis: Implications for aetiology and early prevention. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:882–90. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Høeg TB, Moldow B, Ellervik C, Klemp K, Erngaard D, La Cour M, et al. Danish Rural Eye Study: The association of preschool vision screening with the prevalence of amblyopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:322–9. doi: 10.1111/aos.12639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Finger RP, Bertram B, Wolfram C, Holz FG. Blindness and visual impairment in Germany: A slight fall in prevalence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:484–9. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rosenberg T, Klie F. Current trends in newly registered blindness in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996;74:395–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khairallah M, Kahloun R, Bourne R, Limburg H, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, et al. Number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract worldwide and in world regions, 1990 to 2010. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6762–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]