Abstract

Here we demonstrate the therapeutic effects of transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM, 1267 nm, 32 J/cm2, a 9 day course) in mice with the injected model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) associated with accumulation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) in the brain resulting in neurocognitive deficit vs. the control group (CG) (the neurological severity score (NNS), AD: 3.67 ± 0.58 vs. CG: 1.00 ± 0.26-, p<0.05) and mild cerebral hypoxia (AD: 72±6 % vs. CG: 97±2 %, p<0.001). The course of tPBM improved neurocognitive status of mice with AD (NNS, AD: 2.03 ± 0.14 vs. CG: 1.00 ± 0.26, vs. 2.03 ± 0.14, p<0.05) due to stimulation of clearance of Aβ from the brain via the meningeal lymphatic vessels (the immunohistochemical and confocal data) and an increase in blood oxygen saturation of the brain tissues (the pulse oximetry data) till 85±2 %, p<0.05. These results open breakthrough strategies for non-pharmacological therapy of AD and clearly demonstrate that tPBM might be a promising therapeutic target for preventing or delaying AD based on stimulation of oxygenation of the brain tissues and activation of clearance of toxic molecules via the cerebral lymphatics.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an incurable neurodegenerative disorder, which is characterized by widespread accumulation of Aβ plaques resulting in the progressive development of dementia [1]. In 2013, 6.8 million people in the U.S. had been diagnosed with dementia, among them 5 million had a diagnosis of AD. This number is expected to double by 2050 due to the increased aging population [2]. Currently, there are no pharmacological medications for an effective therapy of AD [3]. Therefore, the non-pharmacological approaches for treatment of AD will be a priority in the next couple of decades. Recently it has been discovered that meningeal lymphatic (MLVs) dysfunction may be an aggravating factor in AD pathology and augmentation of MLV function was proposed as a therapeutic target for prevention of age-associated neurological diseases [4]. The transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM) might be a promising method for stimulation of lymphatic clearance of Aβ and therapy of AD. The PBM known as low-level laser therapy was proposed more than 50 years ago [5]. The PBM is based on shining red lasers (600-700 nm) or near infrared light (760-1200 nm) onto the head via the intact scalp and skull. The light penetrates into the brain where it is absorbed by specific chromophores that stimulates generation of .adenosine triphosphate and nitric oxide with an increase in energetic and metabolic capacities of the brain tissues [5]. A number of reviews have focused on application of tPBM for treatment of AD and depression [6, 7], traumatic brain injuries and stroke [8]. tPBM can reduce Aβ-mediated hippocampal neurodegeneration, memory impairments in rodents, inhibits Aβ-induced brain cell apoptosis and causes a reduction in Aβ plaques in the cerebral cortex [9]. Here we tested our hypothesis that tPBM will stimulate clearance of Aβ from the brain of mice with AD via the activations of cerebral lymphatic drainage and an increase of energy metabolism of the brain tissues.

2. Methods

The experiments were performed in the following groups: 1) control group including the intact mice; 2) sham-treated mice; 3) untreated mice with AD without tPBM; 4) mice with AD received tPBM over 9 days, n=10 in each group in all sets of experiments.

To induce AD in mice, we used the injection of Aβ (1-42) peptide (1 μL, 200 μmol) in the CA1 field of the hippocampus bilaterally (Figure 1-III). The neurobehavioral status of the mice was obtained by the neurological severity score (NSS). The object recognition test was used for memory evaluation.

Fig. 1.

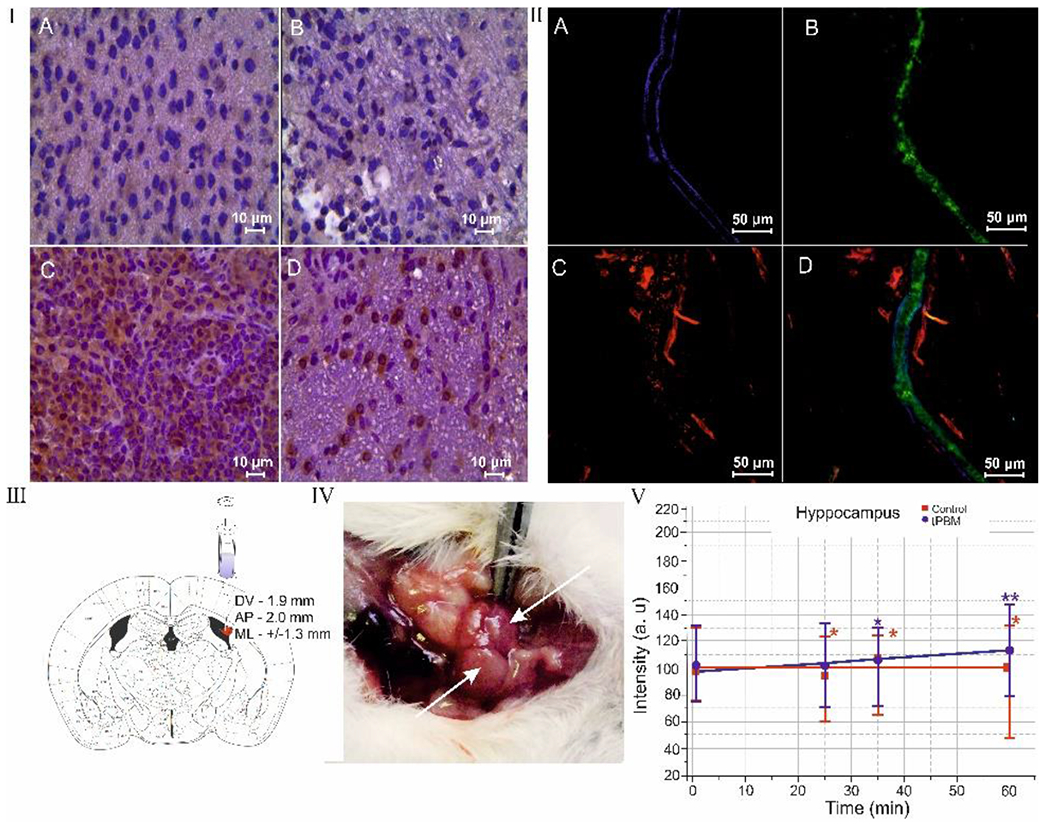

tPBM effects on distribution of Aβ deposition in the mouse brain and clearance of Aβ via MLVs: I – ICH imaging of Aβ depositions (brown color) in the brain tissues in the control group (a), in the sham-treated group (b), in the mice with AD (c) and in mice with AD after tPBM (d); II – the clearance of Aβ (green color) via MLVs (blue color): a – MLV labeled by LYVE-1; b – the precence of fluorecent Aβ in MLVs; c – the cerebral venous vessels (red color) labeled by CD31; d – the marged image from a,b,c; III – stereotaxic coordinates of intrahippocampal injection of Aβ(1-42) peptide in mice; IV - anatomical position of dcLNs on the neck of mouse; V - OCT data of rate of accumulation of GNRs in dcLNs in untreated mice (black line) and in mice received tPBM (red line) after GNRs injection into the hippocampus. * - p<0.05 vs. basal level; † - p<0.05 between groups. n=10 in each group.

A fiber bragg grating wavelength locked high power laser diode (LD-1267-FBG-350, Innolume, Dortmund, Germany) emitting at 1267 nm (32 J/cm2) was used for tPBM [10]. The mice were recovered after the surgery procedure of injection of Aβ 3 days. Afterward, mice were treated by tPBM for 9 days each second day under inhalation anesthesia (1% isoflurane at 1 L/ min N2O/O2 – 70:30). The mice, with shaved heads, were fixed in stereotaxic frame and irradiated in the area of the frontal cortex using the sequence of: 17 min – irradiation, 5 min – pause over 61 min.

A custom-made laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) system was used to monitor relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF). The blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) in the brain was monitored using a pulse oximeter (model CMS60D, Contec Medical Systems Co., Ltd., Qinhuangdao, China). Oxy-hemoglobin saturation is presented as a percentage of HbO2 vs. the total Hb in the blood. The mouse’s head was fixed in stereotaxic frame and then the optodes was placed on the lateral aspect of the skull close to right and left branches of the Sagittal sinus. The recording of the brain saturation was performed during 15 min.

For histological analysis of Aβ depositions in the cortex, we used the protocol for the immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis with anti-Aβ antibody (1:500; Abcam, ab182136, Cambridge, USA).

Gold nanorods (GNRs) coated with thiolated polyethylene glycol (5 μL at a rate of 0.1 μL/min, diameter and length of 16±3 nm and 92±17 nm) were injected in the hippocampus. Afterwards, optical coherence tomography (OCT, Thorlabs GANYMEDE (central wavelength 930 nm, spectral band 150 nm, axial resolution 4.4 μm in water, and maximal imaging depth 2.7 mm) imaging of deep cervical nodes (dcLNs) was performed for 1h in each mouse. The GNR was used with a concentration of 500 μg/ml, the injected dose of 5 μl containing 2.5 μg Au. The GNRs content in dcLNs was evaluated by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

The confocal imaging of the clearance of fluorescent Aβ (HiLyte Fluor 647-conjugated amyloid-β42 at 0.05μg ml–1, AnaSpec, Inc.) via MLVs was performed using the method of brain meninges dissection and antibodies for labelling of lymphatic (LYVE-1) and cerebral (CD31) endothelium (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA) with further confocal microscopy of the dura matter (Olympus, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. The effects of tPBM on the level of Aβ in the mouse brain with AD

In the first step, we demonstrated the effectiveness of using the injected model of AD in mice. Figure 1-Ic illustrates significant accumulation of Aβ plaques in the hippocampus after intrahippocampal injection of Aβ (1-42). There were no Aβ plaques in the brain tissues in the sham-treated and control groups (CG) (Figure1-Ia and b). The behavior analysis demonstrated the memory loss and neurocognitive failure in mice with AD. The NSS scale, which included the tests of mono / hemiparesis, startle reflex, round stick balancing, beam walk, uncovered significant neurological and memory deficit in mice with AD compared with CG (AD: 3.67 ± 0.58 vs. CG: 1.00 ± 0.26, p<0.05). The object recognition test was used for additional evaluation of neurocognitive status of mice with AD. Two identical objects (cubes) were placed in a cage for 10 min. Then one cube was changed to an object unfamiliar earlier (ball). The time for recognition of new object was faster in CG (7 sec) vs. AD (25 sec), i.e. this test revealed a memory deficit in AD vs. CG. tPBM course reduced the accumulation of Aβ deposition in the brain tissues compared with untreated mice (Figure 1-Id). The tPBM also improved NNS (AD: 2.03 ± 0.14 vs. CG: 1.00 ± 0.26, p<0.05) including performance of startle reflex, round stick balancing, and beam walk in mice with AD vs. untreated mice with AD. tPBM improved memory of mice with AD. Indeed, the time for recognition of new object in mice wit AD was reduced to 17 sec.

3.2. Mechanisms of therapeutic effects of tPBM in mice with AD

The study of the mechanisms of therapeutic effects of tPBM showed that tPBM increased the cerebral blood oxygen saturation in both healthy mice and animals with AD. Indeed, SpO2 was elevated after a single application of tPBM in CG (102±2 % vs. 97±2 %) and after a 9 day course of tPBM (tPBM 104±3 % vs. the untreated control 97±2 %) but these changes were not statistically significant. The mice with AD demonstrated a significant decrease in SpO2 compared with CG (AD: 72±6 % vs. CG: 97±2 %, p<0.001). After 9 days of tPBM we observed an increase in SpO2 in mice with AD vs. the untreated mice (AD+tPBM: 85±2 % vs. AD: 72±6 %, p<0.001). However, despite a tendency to normalization of the cerebral blood oxygen saturation after tPBM, the level of SpO2 continued to be lower in the treated mice with AD than in healthy mice (AD+tPBM 85±2 % vs. CG+tPBM 102±2 %, p<0.05 and vs. CG 97±2 %, p<0.05).

LSCI data did not reveal any changes in rCBF in mice with AD compared with the control group as well as after tPBM in both healthy and AD mice (0.37±0.02 0.34±0.02 before and after tPBM in CG; 0.35±0.07 and 0.37±0.09 before and after tPBM in mice with AD).

The elimination of Aβ from the brain of mice with AD after tPBM was accompanied by clearance of Aβ via MLVs. Figure 1-II illustrates the presence of fluorescent Aβ in MLVs in mice with AD after a tPBM course. These data are consistent with our previous results demonstrating clearance of molecules, which crossed the opened blood-brain barrier, via MLVs [11]. We hypothesized that the presence of Aβ in MLVs might be due to stimulation of the lymphatic drainage function by tPBM. To test this idea, we analyzed the effect of tPBM on the clearance of GNRs from the hippocampus (the place of injection of Aβ) into dcLN (Figure 1-III–V). Figure I-V illustrates that tPBM significantly increased the rate of GNRs accumulation in dcLN compared with the intact mice (0.369±0.009 vs. 0.029±0.002, p<0.001). The results of AAS confirmed OCT data and showed a higher level of GNRs in dcLN after tPBM-group vs. untreated group (29.3±1.9 vs. 1.8±0.1, p<0.001).

4. Conclusions

The results clearly demonstrate that a 9 day course of tPBM (1267 nm, 32 J/cm2) reduces Aβ plaques in the brain of mice with AD and stimulates the clearance of Aβ via MLVs. The possible mechanism underlying tPBM-mediated stimulation of lymphatic clearance of Aβ might be tPBM improvement of oxygen consumption of the brain structures including the lymphatic system. The increase in oxygen saturation leads to an enhancement of mitochondrial production of adenosine triphosphate that stimulates lymphatic contractility resulting in an increase drainage and clearing functions of the meningeal lymphatic system. tPBM has a high potential to be applied in routine clinical practice as a promising novel non-pharmacological method for therapy of AD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Russian Science Foundation 18-75-10033 (Immunohistochemical analysis) and 19-15-00201 (measurement of rCBF, SpO2); 20-15-00090 (measurement of lymphatic drainage) and the RF Governmental grant 075-15-2019-1885 (Confocal analysis of lymphatic clearance of beta-amyloid).

References

- 1.Santini Z, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S et al. (2015) Social network typologies and mortality risk among older people in China, India, and Latin America: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based cohort study. Soc. Sci. Med 147, 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ubhi K, Masliah E. (2012. Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances and future perspectives. J. Alzheimers Dis 33(Suppl 1), S185–S194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunkel P, Chai C, Sperlágh B et al. (2012) Clinical utility of neuroprotective agents in neurodegenerative diseases: current status of drug development for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 21(9): 1267–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Mesquita S, Louveau A, Vaccari A (2018) Functional aspects of meningeal lymphatics in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 560(7717): 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamblin M, Ferraresi C, Huang Y-Y, Freitas L, Carroll J (2018) Low-level light therapy : photobiomodulation. Bellingham, Washington, USA: : SPIE Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennessy M, Hamblin M. (2016) Photobiomodulation and the brain: a new paradigm. J. Optics 19(1), 013–003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang J, Ren Y, Wang R et al. (2018) Transcranial Low-Level Laser Therapy for Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychiatry (London) 8(2): 477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naeser M, Hamblin M. (2011) Potential for transcranial laser or LED therapy to treat stroke, traumatic brain injury, and neurodegenerative disease. Photomed. Laser Surg 29(7): 443–446). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, Wang R, Dong Y et al. (2017) Low-level laser therapy for beta amyloid toxicity in rat hippocampus. Neurobiol. Aging 49(1), 165–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinchenko E, Navolokin N, Shirokov A et al. (2019) Pilot study of transcranial photobiomodulation of lymphatic clearance of beta-amyloid from the mouse brain: breakthrough strategies for non-pharmacologic therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Opt Express. 10(8):4003–4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semyachkina-Glushkovskaya O, Chehonin V, Borisova E et al. (2017) Photodynamic opening of the blood-brain barrier and pathways of brain clearing. J Biophotonics. 11(8):e201700287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]