Abstract

Ectomycorrhizal fungi have been introduced in forest nurseries to improve seedling growth. Outplanting of inoculated seedlings to forest plantations raises the questions about inoculant persistence and its effects on indigenous fungal populations. We previously showed (M.-A. Selosse et al. Mol. Ecol. 7:561–573, 1998) that the American strain Laccaria bicolor S238N persisted 10 years after outplanting in a French Douglas fir plantation, without introgression or selfing and without fruiting on uninoculated adjacent plots. In the present study, the relevance of those results to sympatric strains was assessed for another part of the plantation, planted in 1985 with seedlings inoculated with the French strain L. bicolor 81306 or left uninoculated. About 720 Laccaria sp. sporophores, collected from 1994 to 1997, were typed by using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA markers and PCR amplification of the mitochondrial and nuclear ribosomal DNAs. All plots were colonized by small spontaneous discrete genotypes (genets). The inoculant strain 81306 abundantly fruited beneath inoculated trees, with possible introgression in indigenous Laccaria populations but without selfing. In contrast to our previous survey of L. bicolor S238N, L. bicolor 81306 colonized a plot of uninoculated trees. Meiotic segregation analysis verified that the invading genet was strain 81306 (P < 0.00058), implying a vegetative growth of 1.1 m · year−1. This plot was also invaded in 1998 by strain S238N used to inoculate other trees of the plantation. Five other uninoculated plots were free of these inoculant strains. The fate of inoculant strains thus depends less on their geographic origin than on unknown local factors.

The fine-scale structure and dynamics of ectomycorrhizal fungal populations have been studied in several basidiomycete species. Genets (genetic individuals) have been shown to persist over several years (11), and their annual growth accounts for the large areas in old forest stands covered by genets of Suillus bovinus (9), Suillus variegatus (8), Suillus pungens (4), or Pisolithus tinctorius (1). Multiple genets of a small size can be found in young stands (9, 11, 37), probably as a result of the germination of many basidiospores.

The response of ectomycorrhizal fungi to disturbance has been studied at the community level: e.g., after fire (42), pollution (15), or fertilization (25). The population response to disturbance has received little attention so far. Numerous small and short-life-span genets of Hebeloma cylindrosporum have been shown to occur on periodically disturbed dune stands (20). On the other hand, Cantharellus formosus populations were hardly affected by forestry management disturbances (14). Deliberate introduction of selected ectomycorrhizal strains in indigenous populations represents a disturbance in terms of enhancing production of edible mushrooms (10) or improving tree growth (30). Tree inoculation with selected ectomycorrhizal strains can lead to persistent infection in the nursery (21), as well as shortly after outplanting (6, 39, 41). The effect of the strains introduced on native ectomycorrhizal populations remains poorly estimated (40). The population response to strain introduction is of general interest in view of the release of selected fungal strains. The fate of the fungal strains introduced has only been assessed with simple saprophytic systems (34) or for biological control purposes (23), without addressing the question of population modifications. However, in one case, namely the unintentional release of cultivated Agaricus bisporus strains, introgression of introduced markers has been demonstrated in natural populations (43), threatening indigenous populations through extinction by hybridization (26).

Laccaria laccata and Laccaria bicolor are ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes (3) that have a haplodikaryotic life cycle. Dikaryotic mycelia form ectomycorrhizas on tree roots and, under some conditions, produce sporophores (gilled mushrooms). Sporophores bear haploid meiotic spores and can be used to roughly estimate the below-ground population (11). Molecular markers have been designed for Laccaria spp. (13, 17, 18, 38) and allow the study of populations (11, 37). European Laccaria species are commonly found in young and old forest stands (24, 32), notably under Douglas firs, an introduced American tree (22). Since several different strains are currently used for nursery inoculation of Douglas firs in France (30, 41), the genus Laccaria provides an ideal model for tracking strains and analyzing the population effects of outplanting of inoculated trees.

The present study was performed at an inoculated Douglas fir plantation at Saint-Brisson (Nièvre, France), in a region where native Laccaria species have been reported for a century (28). In a previous study of this plantation, an inoculant American strain, L. bicolor S238N, was shown to persist 10 years after outplanting of the mycorrhizal trees (37). This long-term persistence of the inoculant strain on outplanted Douglas firs may be the result of the common geographical origin of the symbiotic partners, namely the Pacific Northwest. Whether European strains are able to persist on this exotic host plant is unknown. The persistence of L. bicolor S238N led to no detectable alteration of the indigenous population; i.e., this strain did not fruit out of inoculated plots and coexisted with several indigenous Laccaria genets (37). However, because mycorrhizal effectiveness is highly variable in L. bicolor strains (27), such a limited colonization may strongly depend on the inoculant strain. Coexisting Laccaria genets in the plantation showed no detectable introgression, although the S238N strain is infertile in vitro with European genets (38). This absence of hybrids could result from some outbreeding depression, which would not occur when sympatric strains are used for nursery inoculation. The present study assesses the response of Laccaria populations to outplanting of Douglas firs that were nursery inoculated with a French strain, L. bicolor 81306, and planted in another part of the Saint-Brisson plantation. We investigated (i) the persistence of the nursery-inoculated strain L. bicolor 81306, (ii) its effect on the indigenous genetic diversity, and (iii) the fine-scale genetic structure of the population under surrounding uninoculated trees.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and tree inoculation.

Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mir.] Franco) seedlings were inoculated on fumigated nursery soil in 1985 at the Peyrat-le-Château nursery (Haute-Vienne, France) according to the protocol described by Villeneuve et al. (41). The American strain, L. bicolor ([Maire] Orton) S238N (see reference 12 for a detailed origin), and the European strain L. bicolor 81306, isolated in 1981 from a sporophore collected under Douglas firs at Barbaroux (Haute-Vienne, France), were used for inoculation. Both strains are conserved at the Collection of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Nancy, France). Uninoculated seedlings were obtained from fumigated or nonfumigated soils in two French nurseries, Mieville (Nièvre) and Peyrat-le-Château. In the two uninoculated treatment groups, naturally occurring ectomycorrhizal fungi (among which were some Laccaria spp.) were shown to colonize root systems before outplanting (21). Two-year-old seedlings were outplanted in spring 1987 at an experimental plantation at Saint-Brisson (Nièvre), 200 km from both nurseries.

Experimental plantation.

The Saint-Brisson forest site, situated at an elevation of 630 m, was previously a dedicuous forest on a brown podzolic soil over granite, where Laccaria species occur spontaneously (28). The stand was divided into plots of 7.2 by 7.2 m, each containing 49 seedlings given an identical nursery treatment and separated by a 3-m nonplanted buffer zone. Trees from the same treatment were randomly distributed among four replicate plots. Each plot was thinned twice (1992 and 1995), with half of the trees being cut on each occasion. A subset of nine contiguous plots of the plantation (i.e., 1,129 m2 [see Fig. 3]) was analyzed in that study, including at least one plot for each seedling treatment (Table 1).

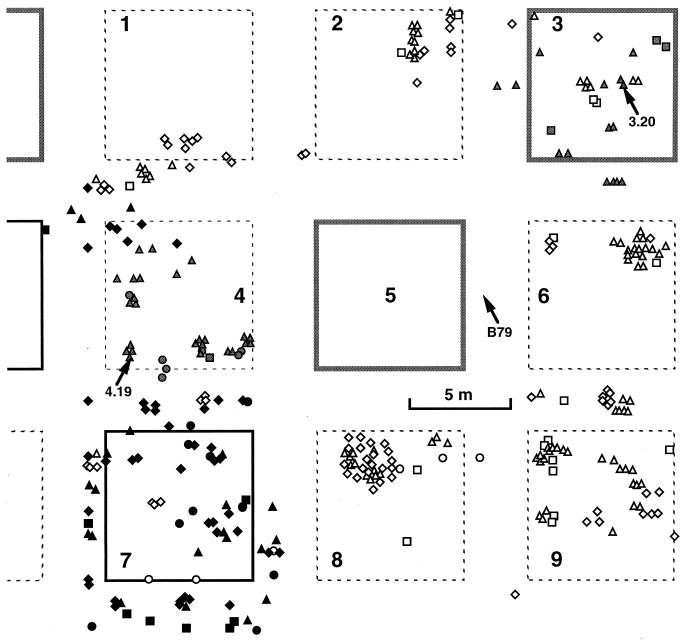

FIG. 3.

Map of the nine plots of the Douglas fir plantation at Saint-Brisson studied showing the spatial distribution of the Laccaria sporophores. Plots are limited by dotted lines (control seedlings, naturally mycorrhizal), continuous dark lines (seedlings experimentally inoculated with strain S238N), or continuous grey lines (seedlings experimentally inoculated with strain 81306). L. bicolor 81306 sporophores are represented in grey, L. bicolor S238N sporophores are represented in black, and sporophores of other genets are in white; they were collected in 1994 (circles), 1995 (squares), 1996 (triangles), or 1997 (diamonds). The central zone around plot 5 is depicted in Fig. 2. Sporophores 3.20, B79, and 4.19, used for the segregation analysis (Table 3), are localized on plots 3, 5, and 4, respectively (arrows).

TABLE 1.

Description of the nine plots of the Douglas fir plantation at Saint-Brissona

| Plot | Seedling treatment and nurseryb | Sporophores of inoculant strains on plot | No. of other genets found on:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plotc | Plot and buffer zonesd | |||

| 1 | Seedlings grown on nonfumigated soil, no inoculation (= plots 6 and 8), M | None | 3 | 7 |

| 2 | Seedlings grown on fumigated soil, no inoculation (= plot 4), P | None | 6 | 13 |

| 3 | Seedlings experimentally inoculated with L. bicolor 81306 (= plot 5), P | 81306 | 4 | 8 |

| 4 | Seedlings grown on fumigated soil, no inoculation (= plot 2), P | 81306 and S238N | 0 | 8 |

| 5 | Seedlings experimentally inoculated with L. bicolor 81306 (= plot 3), P | 81306 | 4 | 17 |

| 6 | Seedlings grown on nonfumigated soil, no inoculation (= plots 1 and 8), M | None | 4 | 13 |

| 7 | Seedlings experimentally inoculated with L. bicolor S238N, P | S238N | 3 | 7 |

| 8 | Seedlings grown on nonfumigated soil, no inoculation (= plots 1 and 6), M | None | 9 | 15 |

| 9 | Seedlings grown on nonfumigated soil, no inoculation, P | None | 9 | 16 |

The numbers of Laccaria genets found over the 3 years of the study are indicated. For a spatial distribution of the plots, see Fig. 3.

Mieville nursery; Peyrat-le-Château nursery.

Plot area: 7.2 by 7.2 (51.84 m2).

Plot and surrounding buffer zones (i.e., 13.2 by 13.2 [174.24 m2]); some genets of the buffer zones were thus counted more than once in this column.

Sporophore sampling.

Sporophores of Laccaria spp. were sampled on the nine plots between fall 1994 and summer 1997. They represented more than 98% of the epigeous sporophores of ectomycorrhizal fungi on the plantation. Amanita muscaria and Cortinarius sp. sporophores were occasionally observed. Both L. bicolor and L. laccata were collected because the Laccaria genus is divided on the basis of morphological criteria (3, 33), and there are insufficient data about the reproductive barriers in Europe. In all, 380 sporophores (Table 2) were collected on plot 5, where Douglas fir seedlings inoculated with strain 81306 were outplanted, through a comprehensive sporophore collection, except in 1994 (only one sporophore randomly chosen for each patch of sporophores on the plot). Morphological identification of Laccaria species was performed according to the method of Bon (3), without distinguishing among subspecies. The ground location of those sporophores was mapped with a precision of 5 cm. Isolation of vegetative mycelium (37) was done from all sporophores collected in 1995, leading to 105 successful pure cultures. On the other plots, random sporophore collections in 1994 and 1995 (1 sporophore per patch) and comprehensive samplings in 1996 and 1997 provided 339 additional sporophores (25 in 1994, 28 in 1995, 158 in 1996, and 128 in 1997). The ground location of those additional sporophores was mapped with a precision of 10 cm. Sporophores were kept at −80°C before DNA extraction.

TABLE 2.

Number of sporophores produced by the 18 Laccaria genets found on plot 5 and the surrounding buffer zone between 1994 and 1997a

| Genet | No. of sporophores produced in yr:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994b | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | Totalb | |

| L. bicolor | |||||

| A (=81306) | 28 | 94 | 29 | 0 | 151 |

| B | 5 | 24 | 4 | 7 | 40 |

| C | 0c | 4 | 5 | 7 | 16 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| E | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| G | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| L. laccata | |||||

| H | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| I | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| J | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 8 |

| K | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| L | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| M | 0 | 32 | 0 | 14 | 46 |

| N | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0 | 23 |

| O | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 11 |

| P | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Q | 0 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 18 |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 38 | 195 | 77 | 70 | 380 |

Molecular typing.

Total DNA from frozen sporophores and mycelium was extracted by the protocol of Henrion et al. (21). DNA extracted from the 105 pure cultures obtained in 1995 gave rise to DNA fingerprints identical to those obtained from the original sporophores (data not shown), indicating that sporophore DNA was not contaminated by other microbial DNA (see also reference 37). The molecular typing was therefore performed directly on sporophore DNA. The 25S/5S spacer (IGS1) and the 5S/17S spacer (IGS2) of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) were amplified as described by Selosse et al. (36). Molecular typing with randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers was carried out at least twice with primers 152C (5′-CGCACCGCAC-3′), 155 (5′-CGTGCGGCTG-3′), 156 (5′-GCCTGGTTGC-3′), and 174 (5′-AACGGGCAGC-3′) (37). Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism was assessed by using a fragment of the mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit DNA (LrDNA) amplified with primers ML3 and ML6 (38). The identity of genets showing a RAPD pattern identical to that of the inoculant strain S238N was further assessed by using other RAPD and mitochondrial markers previously described (37, 38).

Segregation analysis.

Spores were collected from three L. bicolor sporophores found in 1996, showing RAPD patterns identical to that of strain 81306, namely 3.20 on plot 3 (12 monokaryons), 4.19 on plot 4 (15 monokaryons), and B79 on plot 5 (29 monokaryons). They were germinated according to the method of Fries (16), and haploidy was confirmed by checking for the absence of clamp connections. Only major reproducible RAPD fragments were scored (Table 3). Fragments present in the whole progeny were considered as homozygous markers. (A less likely mitochondrial origin was not considered.) The fragments that were not present in all haploids were considered as heterozygous markers. For some fragments, it was possible to find another fragment showing a complementary segregation (i.e., haploids always had one fragment of the couple, but never none or both). In this case, both fragments were considered as alleles of a heterozygous marker. (Alternatively, they may be tightly linked in repulsion, a situation that does not change the genetic analysis.) Other fragments were considered as heterozygous dominant markers, with the present fragment allele dominant over the absent fragment allele.

TABLE 3.

Segregation of the RAPD and rDNA markers in haploid progenies of three L. bicolor 81306-related sporophores collected in 1996 on plots 3 (sporophore 3.20), 4 (sporophore 4.19), and 5 (sporophore B79)a

| Primer name | Fragment size (bp)b | Segregation in monokaryons fromc:

|

Linkage groupd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.20 | 4.19 | B79 | |||

| 152C | 1,900 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | |

| 1,800 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 1,100 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 570 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 450 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 350 or 340 | 91:3s | 121:3s | 171:12s* | ||

| 250 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 155 | 1,400 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | |

| 1,150 | 5+:7− | 6+:9− | 12+:17−* | A (2,4,4) | |

| 1,000 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 800 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 620 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 500 | 5+:7− | 5+:10− | 11+:18−* | B (0, 2,3) | |

| 430 or 380 | 61:6s | 71:8s | 141:15s* | C (3,2,5) | |

| 240 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 200 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 190 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 170 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 157 | 2,000 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | |

| 1,400 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 960 | 6+:6− | 9+:6− | 18+:11−* | D (2,2,2) | |

| 510 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 370 | 8+:4− | 9+:6− | 17+:12−* | ||

| 360 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 330 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 210 | 7+:5− | 8+:7− | 14+:15−* | C (3,2,5) | |

| 200 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 190 | 8+:4− | 10+:5− | 19+:10−* | ||

| 174 | 2,500 | 7+:5− | 11+:4− | 19+:10−* | A (2,4,4) |

| 880 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 700 | 5+:7− | 7+:8− | 14+:15−* | B (0, 2,3) | |

| 540 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 500 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 380 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 300 | 9+:3− | 11+:4− | 16+:13−* | ||

| 260 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 220 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| 160 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | ||

| rDNA | |||||

| Nuclear | α/β | 4:8 | 6:9 | 9:20 | D (2,2,2) |

| Mitochondrial | 1,100 | 12+:0− | 15+:0− | 29+:0− | |

The sporophores are shown by arrows in Fig. 3.

Allelic fragments are presented in the same row of the table. Fragments shared by genets A and B (Table 1) are underlined.

+, fragment of allele present; −, fragment of allele absent; 1, larger fragment allele; s, smaller fragment allele. Fragments amplified from heterozygous loci are in boldface. *, chi-square result not significantly different from 1:1 segregation at the 0.05 level.

Four linkage groups of two markers each were identified: A, B, C, and D. For each linkage group, the number of recombinants observed in each progeny is given in parentheses (for the 3.20, 4.19, and B79 progeny, respectively).

Genetic analysis.

The linkage relationships of the Mendelian markers were analyzed in haploid progenies with MAPMAKER 2.0 for Macintosh as described by Selosse et al. (37). The robustness of the typing of 81306 was assessed by calculating the probability of retaining in F1 the parental RAPD genotype. During selfing, assuming that no segregation bias occurs, the probability of retaining the parental genotype is P = 1 for a homozygous locus and P = 0.5 for a heterozygous locus: thus, P = (0.5)n for n independent heterozygous loci. In the case where q linkage groups involve a total of k loci (k ≤ n), the formula is changed to

|

where χi is the probability of retaining the genotype for the linkage group number, i (1 ≤ i ≤ q). In the case encountered in this study (two linked loci with a recombination fraction, r), parental genotypes arise at a frequency of χ = [(1 − r)2]/2 after selfing. This formula was used with the r values obtained from the B79 segregation (Table 3).

RESULTS

Temporal structure of fruiting on an inoculated plot.

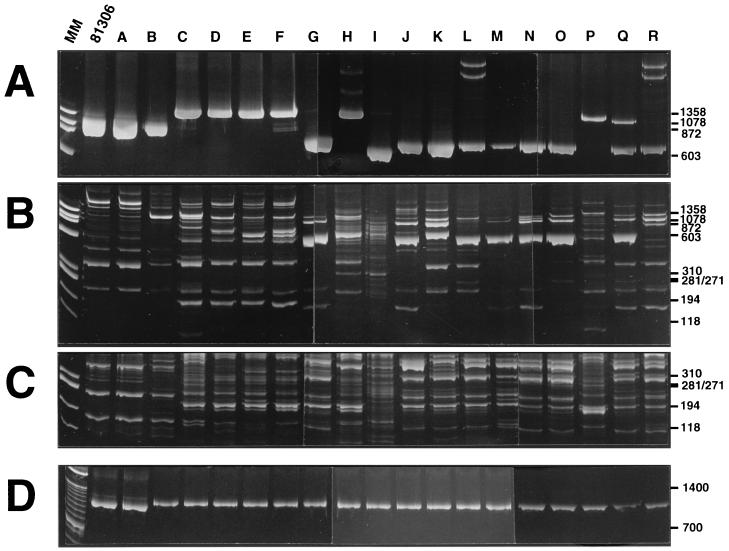

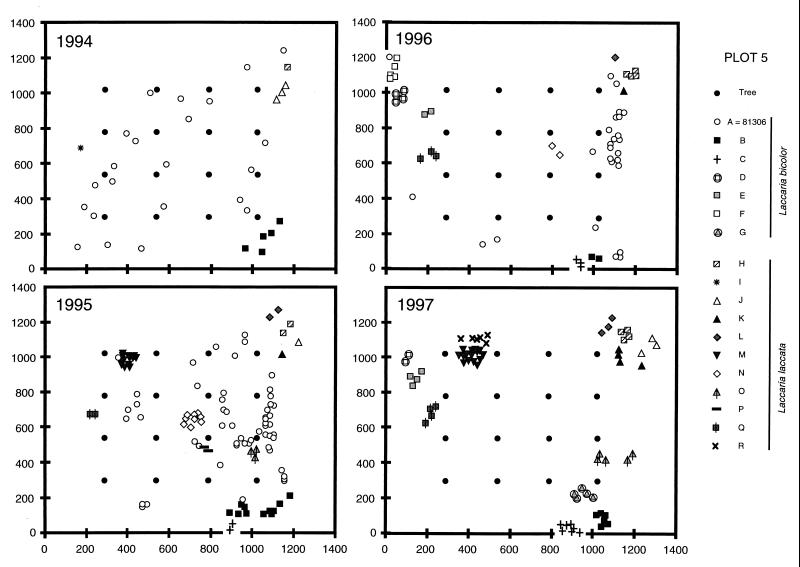

The Saint-Brisson plantation is divided into several plots where Douglas firs differing in their mycorrhizal nursery treatment (i.e., inoculated with an L. bicolor strain or uninoculated) were outplanted in 1987 (Table 1 and see Fig. 3). In all, 380 L. bicolor and L. laccata sporophores were collected between fall 1994 and summer 1997 from plot 5, where trees were inoculated in the nursery with L. bicolor 81306. The sporophores always appeared in the fall, except for July 1997, when fruiting was abundant, probably as a result of an unusually rainy summer. The various sporophores were typed by using the IGSs of the rDNA (Fig. 1A) and RAPD patterns (e.g., primers 152C and 174 [Fig. 1B and C]). Forty to 62 major RAPD fragments were scored for each genet, for a total of 264 distinct fragments. By combining these markers, the 380 sporophores were shown to belong to 18 genets (seven L. bicolor genets and 11 L. laccata genets [Table 2]). Some genets were present during the 3-year survey (genets B and H), whereas others were not detected during 1 (e.g., J in 1996) or 2 years (e.g., D and Q). Since some genets were found only once (e.g., F and I), we cannot rule out the possibility that some genets persisted for a single year.

FIG. 1.

Molecular patterns of the 18 Laccaria genets (A to R) found on plot 5, compared to L. bicolor 81306. (A) Amplified IGS1 (note the presence of heteroduplexes [bands over 1.3 kb in lanes H, L, and R]). (B) RAPD pattern obtained with primer 152C (short migration separating fragments in the 100- to 600-bp range). (C) RAPD pattern obtained with primer 174 (short migration showing only the fragments in the 100- to 400-bp range [note the similarity between genets A and B]). (D) Polymorphic fragment of the LrDNA amplified with primers ML3 and ML6. Separation was achieved on an 8% acrylamide gel. MM, molecular size marker (Phi-X-174 digested by HaeIII or a 100-bp DNA ladder). The sizes are given on the right in base pairs.

Evidence for persistence of the inoculant strain.

Genet A was genetically identical to the inoculant strain L. bicolor 81306 for all markers (Fig. 1). The sizes of the LrDNAs were also identical, suggesting the retention of the mitochondria of the introduced strain in genet A (Fig. 1D). The strain 81306 did not fruit in summer 1997, but additional sporophores collected in fall 1997 showed that it was still present on the surrounding zone of plot 5 (data not shown). The other genets shared limited similarities to the inoculant strain (Fig. 2). The genet B shared 26 of its 45 RAPD fragments with the strain 81306 (Fig. 1B and C [see fragments underlined in Table 3]) as well as an indistinguishable IGS1 (Fig. 1A), while the other genets only shared up to 12 fragments with the strain 81306 (up to only 6 fragments for the L. laccata genets). Genet B could result from the breeding of the introduced strain 81306 (=genet A) with a local genet. Molecular data thus demonstrated the persistence, and possibly the nuclear introgression, of the inoculant genotype.

FIG. 2.

Spatial distribution of the various Laccaria sporophores on plot 5 (Douglas fir inoculated with L. bicolor 81306) in 1994, 1995, 1996, and summer 1997. Positions where one or more sporophores were found are marked with a symbol representing the genet to which the sporophore belongs. The scale is given in centimeters.

Spatial structure of populations on an inoculated plot.

The sporophores collected on plot 5 were mapped from 1994 to 1997 (Fig. 2). Due to the 5-cm resolution limit, several sporophores sometimes mapped at the same position, but they always belonged to the same genet. Sporophores of a given genet always formed single patches, with the exception of the inoculant genet 81306, which fruited over the whole plot in several patches (Fig. 2). The buffer zones (limited by the outer trees) were colonized by 15 genets and showed a fairly constant sporophore density from year to year. The plot was colonized by only five genets and showed a reduction of fruiting density with time. As estimated by the maximal distance between sporophores, the size of the fruiting domain ranged from a few centimeters (in the case of genet I, represented by a single sporophore in 1994) to 3.3 m (genet B in 1995). Genets always occupied the same territory from year to year, with only minor changes (such as a reduction in apparent size for genet B or an enlargement of genet O toward the buffer zones), forming a stable population over the time span of the survey.

Dispersion of the inoculant strain to neighboring plots.

In all, 339 sporophores were sampled over the 3 years on plots surrounding plot 5. They belong to 54 genets (data not shown). Plot 3 (trees inoculated by the strain 81306) mainly exhibited sporophores of the inoculant strain (Fig. 3). The American strain, L. bicolor S238N, also remained on plot 7, where trees inoculated with this strain were introduced (Fig. 3), as reported by Selosse et al. (37). A patch of sporophores from this strain was also found between plots 1 and 4, in the border zone flanking an inoculated plot not studied here (Fig. 4). The 52 other Laccaria genets were found in both inoculated and uninoculated plots (Table 1). Plot 4, although carrying uninoculated trees, harbored exclusively the two introduced genets (S238N in 1998 and 81306 over 3 years [Fig. 3]). The other uninoculated plots (1, 2, 6, 8, and 9) were free of inoculant strains and showed three to nine genets (Table 1). The densities of genets per plot were similar on inoculated plots (four to five genets, including the inoculant one), suggesting that the persistence of inoculant genets has no definite effect on the settlement of new fruiting genets. No cytoplasmic introgression of the strain 81306 was detected among the other genets, since none of them showed its characteristic LrDNA (Fig. 1D).

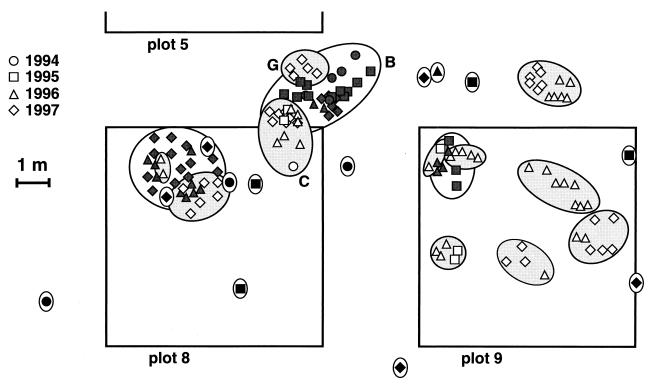

FIG. 4.

Spatial distribution of the Laccaria genets found over 3 years on the uninoculated plots 8 and 9. The seedlings originated from the Mieville and the Peyrat-le-Château nurseries, respectively [Table 1].) Sporophores were collected in 1994 (circles), 1995 (squares), 1996 (triangles), or 1997 (diamonds). Borderlines encompass sporophores belonging to the same genet. Genets from the buffer zone between plots 5 and 8 are named in the figure (Table 1). In buffer zones near inoculated plots, sporophores of inoculant strains L. bicolor 81306 and S238N (Fig. 3) were omitted for clarity.

Genetic evidence for the spreading of L. bicolor 81306.

To further ensure the identity between the genet invading plot 4 and the genets lasting on plots inoculated by L. bicolor 81306 (plots 3 and 5), we compared the meiotic segregation of markers in a haploid progeny of one sporophore of each plot. (The position of the three sporophores is given in Fig. 3.) The results are summarized in Table 3. The rDNA, corresponding to a single locus in Laccaria (36), showed allelic IGS2 fragments segregating in the three progenies (Table 3) with a strong distortion, as often observed for L. bicolor heterozygosities (13, 37). Each of the 40 RAPD fragments obtained with the four RAPD primers was transmitted identically in the three progenies (Table 3), indicating 27 homozygous markers, with 9 heterozygous dominant and 2 heterozygous codominant markers in every case. Combined linkage analysis of RAPD and ribosomal markers showed four linkage groups of two markers each in the three progenies (Table 3), with identical alleles in cis (not shown). We therefore monitored eight genetically independent heterozygous loci. After selfing, the probability of retaining all of these heterozygosities in F1 is thus P = 0.00058 (see Materials and Methods), so that selfing is unlikely to explain the identical genotypes of the three sporophores. This demonstrated that the inoculant strain 81306 spread into the control plot 4 without selfing or introgression. This dissemination likely relied on vegetative growth.

Spatial structure of fruiting on uninvaded plots.

Genets were mapped through sporophore position in the uninvaded control plots surrounding plot 5 (plots 1, 2, 6, 8, and 9—see the detailed map of plots 8 and 9 in Fig. 4). Some genets were found over 2 to 3 years, while others were represented by a single sporophore collected over only 1 year, perhaps due to the sampling procedure. Sporophores of a given genet always clustered on small areas, were never fragmented, and sometimes intermingled with other genets (Fig. 4). As estimated by the maximal distance between sporophores, the genets covered up to 2.4 m (e.g., the larger genets on plots 8 and 9), a structure very reminiscent of the genets of plot 5 (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

We analyzed a Laccaria population under several plots of a Douglas fir plantation (Fig. 3). Seedlings of some plots were nursery inoculated with an L. bicolor strain before outplanting (Table 1). We investigated the pattern of sporophore production as in order to trace the dissemination of these symbionts in the plantation. On the sampled area, molecular typing (Fig. 1) allowed to distinguish 71 genets, including the inoculant ones (i.e., a density of 600 genets · ha−1). Laccaria fruiting increasingly tends to be localized at the buffer zones between the plots (see years 1996 and 1997 on Fig. 2). This is reminiscent of the outward shift of ectomycorrhizal sporophores observed under young trees from year to year (11, 32) or the reduction of fruiting reported after canopy closure (22).

Some Laccaria genets were identified over 3 successive years, as previously reported at other experimental sites (11, 37, 38), whereas others were found only over a single year (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Lack of sporophores is not informative, since genets J and M, which fruited in 1995 and 1997, were probably present at the vegetative stage in 1996 (Table 2). Genets likely respond differentially to identical climatic conditions. During the rainy summer of 1997, we observed abundant sporophore production of both new and already described genets, with a pattern similar to those found in the fall (Table 2). Those data confirmed that (i) several successive sampling years are needed to obtain a complete picture of ectomycorrhizal populations, (ii) sporophores do not exactly reflect the above-ground population colonizing the roots, and (iii) sporophore sampling therefore cannot quantify the below-ground frequency of the genets. This discrepancy between below- and above-ground populations, also demonstrated at the mycorrhizal community level (19, 22), suggests that different resource allocation strategies (growth versus reproduction) may coexist within a Laccaria species.

Except for the inoculant L. bicolor genets (S238N and 81306), the distribution of the sporophores of one genet was always clustered (Fig. 3 and 4). The maximal distance between two sporophores of the same genet was 3.3 m (genet B [Fig. 2]), a distance observed for L. bicolor genets in young plantations (11, 37). No expansion of the genets was observed over 3 years, except for some limited migration (e.g., genet C [Fig. 4]). We cannot exclude the possibility that some of these genets originated from the nurseries, since Laccaria genets colonize uninoculated seedlings in the nursery (21). However, their small size and the fact that they are not fragmented over the plantation suggest that they arose from basidiospores after outplanting. Colonization of new stands by basidiospores has frequently been suggested for early-stage and ruderal ectomycorrhizal fungi (20, 29), as well as other forest basidiomycetes (5). Congruently, the high heterozygosity level in L. bicolor isolates (0.31 for strain 81306 in this study, 0.39 in the study by Raffle et al. [35], and 0.35 in the study by Selosse et al. [37]) implies a high outcrossing rate and supports a long-distance dispersion of the basidiospores before the rise of new dikaryons. At least one other ectomycorrhizal species, S. pungens, may share the same outcrossing and dissemination strategy (4).

Trees of several plots were inoculated with two L. bicolor strains in the nursery, namely the American strain, S238N, and the French strain, 81306 (Table 1). Both strains were still present 8 to 10 years after outplanting and fruited abundantly (Table 2) over large areas (Fig. 3). The persistence of L. bicolor S238N on plot 7 is in agreement with previous reports on the persistence of this strain in the nursery (21) and field plantation (37, 41). The persistence of L. bicolor 81306 confirms that L. bicolor is a competitive forest symbiont of Douglas firs (6, 30), independent of its American or European geographical origin. Contrasting with previous results obtained for strain S238N (37), a possible introgression of the strain 81306 was detected. Genet B shared 26 (accounting for 25 loci [Table 3]) of the 40 RAPD fragments of strain 81306. However, it lacked some homozygous markers of strain 81306 and therefore cannot be an F1 hybrid. A fortuitous genetic similarity cannot be ruled out, as a result of promiscuous European alleles, since strain 81306 was isolated in central France. No cytoplasmic introgression was detected on the basis of the LrDNA analysis (Fig. 1D), as earlier reported for L. bicolor S238N (38). However, we cannot exclude the presence of other hybrids on roots, as discussed in reference 37. For example, unfertile hybrids resulting from somatic interactions (2) could only be detected by studying mycorrhizas.

The simultaneous invasion of a plot of uninoculated trees (plot 4 [Fig. 3]) by the two inoculant Laccaria strains contrasts with our previous observation of another part of the Saint-Brisson plantation, where L. bicolor S238N was restricted to inoculated plots (37). The probability of retaining the S238N RAPD patterns after selfing (P = 0.0008 [37]) reasonably excludes colonization by spores followed by selfing. For L. bicolor 81306, segregation analysis ensured that one sporophore of plot 4 had the same genotype as sporophores found on the plot inoculated by strain 81306 (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The low probability of retaining the parental genotype after selfing (P = 0.00058) suggests a vegetative propagation, which also explains the continuous distribution of strain 81306 sporophores between plots 4 and 5 (compare Fig. 2 and 3 for the year 1994). The genet 81306 covered a domain extending at least from plot 3 to plot 4; the most distant sporophores are 30.5 m apart (Fig. 3), as for old natural mycorrhizal genets of Suillus spp. (4, 8, 9) or P. tinctorius (1). Colonization of root systems by both spores, as previously stated, and vegetative growth may explain the success of Laccaria species in both young and older forest stands.

The strain S238N found on plot 4 likely arose from the S238N-inoculated trees of a flanking inoculated plot (Fig. 3). The distance to the nearest inoculated tree (5.3 min July 1997, 11.3 years after outplanting) suggests that the growth rate of the invading mycelium was at least 0.47 m · year−1. The strain 81306 similarly colonized a wide area of plot 4, probably from plot 5, the nearest inoculated plot. In 1994 (7.5 years after outplanting), the invasion reached 8.4 m (i.e., a progression of 1.1 m · year−1). Current data on the growth rate of Laccaria spp., estimated from sporophore migration, range from 0.2 m · year−1 (11) to 0.87 m · year−1 (32). A growth rate of 0.2 to 0.5 m · year−1 accounts for the surface covered by old Suillus genets (4, 9). In vitro growth of the strain S238N reaches 0.2 cm per day (12) (i.e., 0.72 m per year of continuous growth). The expansion rate calculated for L. bicolor 81306 thus remains beyond the reported and in vitro-estimated growth values. Field colonization by the strain 81306 could also be enhanced by host root growth or fortuitous transport of mycelium by soil fauna or during tree thinnings.

The lack of invasion of plot 2 (a replicate of plot 4 [Table 1]) suggests that the initial growth of trees in the nursery is not responsible for increased receptivity or contamination of Douglas firs from plot 4. In addition, there was no obvious fungal strain effect, since both inoculant strains invaded the plot. Strikingly, no other genets fruited on this plot (Fig. 3), although their vegetative presence cannot be ruled out. This can be considered either as a result of the invasion or as a cause of the susceptibility of this plot. A depauperate mycorrhizal community may have been unable to outcompete the introduced strains (7), but there is little agreement on factors favoring invasion in ecosystems (31).

Inoculant L. bicolor strains thus persist without selfing and cytoplasmic introgression after outplanting of the host trees. The populational disturbance is highly variable at the stand level, ranging from no disturbance of the ectomycorrhizal diversity (most uninoculated plots in Table 1) to localized displacement of other genets and possible nuclear introgression, depending on poorly identifiable environmental factors. The fact that a genotype that is often selected against may show aggressive abilities in some situations is of great value in view of the release of selected fungal strains (23, 34). To confirm the present conclusions, further surveys are needed in plantations experiencing different ecological conditions (30, 39) and with other tree-fungal associations. In addition, since sporophore surveys do not directly assess the persistence of inoculant strains as symbionts on roots, the development of new markers for specific multilocus fingerprinting of soil-collected mycorrhizas, which harbor various contaminant organisms, is required to estimate the outcome of inoculations on natural populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Bernier and R. Bindner for contributing to the typing of the sporophores, J.-L. Dupouey for assistance with statistics, and the company France-Forêts, owner of the Saint-Brisson stand, for access to the experimental plots.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Bureau des Ressources Génétiques, the Ministère de l’Environnement, and EU contract PL 931742.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson I C, Chambers S M, Cairney J W G. Use of molecular methods to estimate the size and distribution of mycelial individuals of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Pisolithus tinctorius. Mycol Res. 1998;102:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J B, Kohn L M. Genotyping, gene genealogies and genomics bring fungal population genetics above ground. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bon M. Tricholomataceae de France et d’Europe occidentale (6ème partie: Tribu Clitocybeae Fayod). Clé monographique. Doc Mycol. 1983;51:1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonello P, Bruns T D, Gardes M. Genetic structure of a natural population of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus pungens. New Phytol. 1998;138:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasier C. A champion thallus. Nature. 1992;356:382–383. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buschena C A, Doudrick R L, Anderson N A. Persistence of Laccaria spp. as ectomycorrhizal symbionts of container-grown black-spruce. Can J For Res. 1992;22:1883–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case T J. Invasion resistance arises in strongly interacting species-rich model competition communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9610–9614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlberg A. Population ecology of Suillus variegatus in old Swedish Scots pine forests. Mycol Res. 1997;101:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlberg A, Stenlid J. Population structure and dynamics in Suillus bovinus as indicated by spatial distribution of fungal clones. New Phytol. 1990;115:487–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danell E, Camacho F J. Successful cultivation of the golden chanterelle. Nature. 1997;385:303. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De la Bastide P Y, Kropp B R, Piché Y. Spatial distribution and temporal persistence of discrete genotypes of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor (Maire) Orton. New Phytol. 1994;127:547–556. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Battista C, Selosse M-A, Bouchard D, Stenström E, Le Tacon F. Variations in symbiotic efficiency, phenotypic characters and ploidy level among different isolates of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor strain S238. Mycol Res. 1996;100:1315–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doudrick R L, Raffle V L, Nelson C D, Furnier G R. Genetic analysis of homokaryons from a basidiome of Laccaria bicolor using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers. Mycol Res. 1995;99:1361–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunham S, O’Dell T, Molina R, Pilz D. Abstracts of the 2nd International Congress on Mycorrhizae 1998. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; 1998. Fine scale genetic structure of chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus) patches in forest stands with different disturbance intensities; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellner R, Peskova V. Effect of industrial pollutants on ectomycorrhizal relationships in temperate forests. Can J Bot. 1995;73(Suppl. 1):1310–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fries N. Spore germination, homing reaction, and intersterility groups in Laccaria laccata (Agaricales) Mycologia. 1983;75:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardes M, Mueller G M. Intra- and inter-specific relations within Laccaria bicolor sensu lato. Mycol Res. 1991;95:592–601. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardes M, Mueller G M, Fortin J A, Kropp B R. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism in Laccaria bicolor, L. laccata, L. proxima and L. amethystina. Mycol Res. 1991;95:206–216. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardes M, Bruns T D. Community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a Pinus muricata forest: above- and below-ground views. Can J Bot. 1996;74:1572–1583. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gryta H, Debaud J-C, Effosse A, Gay G, Marmeisse R. Fine scale structure of populations of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum in coastal sand dune forest ecosystems. Mol Ecol. 1997;6:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrion B, Di Battista C, Bouchard D, Vairelles D, Thomson B D, Le Tacon F, Martin F. Monitoring the persistence of Laccaria bicolor as an ectomycorrhizal symbiont of nursery-grown Douglas fir by PCR of the rDNA intergenic spacer. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:571–580. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen A E, de Nie H W. Relations between mycorrhizas and fruitbodies of mycorrhizal fungi in Douglas fir plantations in The Netherlands. Acta Bot Neerl. 1988;37:243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen D F, Jansson H B, Tronsmo A. Monitoring antagonistic fungi deliberately released into the environment. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalamees K, Silvers S. Fungal productivity of pine heaths in North-West Estonia. Acta Bot Fenn. 1988;136:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karen O, Nylund J E. Effects of N-free fertilization on ectomycorrhiza community structure in Norway spruce stands in Southern Sweden. Plant Soil. 1996;181:295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerrigan R W, Carvalho D B, Horgen P A, Anderson J B. The indigenous coastal Californian population of the mushroom Agaricus bisporus, a cultivated species, may be at risk of extinction. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kropp B. Inheritance of the ability for ectomycorrhizal colonization of Pinus strobus by Laccaria bicolor. Mycologia. 1997;89:578–585. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langey J. D’un inventaire mycologique à l’autre. Deuxième partie: les espèces leucosporées. Bull Soc Hist Nat Autun. 1995;156:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Last F T, Dighton J, Mason P A. Successions of sheathing mycorrhizal fungi. Trends Ecol Evol. 1987;2:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(87)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Tacon F, Alvarez I F, Bouchard D, Henrion B, Jackson R M, Luff S, Parlade J I, Pera J, Stenström E, Villeneuve N, Walker C. Variations in field response of forest trees to nursery ectomycorrhizal inoculation in Europe. In: Read D J, Lewis D H, Fitter A H, Alexander I J, editors. Mycorrhizas in ecosystems. Wallingford, Conn: CAB International; 1992. pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lodge D M. Biological invasions: lessons for ecology. Trends Ecol Evol. 1993;8:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90025-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason P A, Last F T, Pelham J, Ingleby K. Ecology of some fungi associated with ageing stand of birches (Betule pendula and B. pubescens) For Ecol Manag. 1982;4:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller G M. Systematics of Laccaria (Agaricales) in the continental United States and Canada, with discussions on extralimital taxa and descriptions of extant types. Fieldiana Bot. 1992;30:1–158. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Querol A, Barrio E, Huerta T, Ramon D. Molecular monitoring of wine fermentations conducted by active dry yeast strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2948–2953. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2948-2953.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raffle V L, Anderson N A, Furnier G R, Doudrick R L. Variation in mating competence and random amplified polymorphic DNA in Laccaria bicolor (Agaricales) associated with three tree host species. Can J Bot. 1995;73:884–890. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selosse M-A, Costa G, Di Battista C, Le Tacon F, Martin F. Segregation and recombination of ribosomal haplotypes in the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor monitored by PCR and heteroduplex analysis. Curr Genet. 1996;30:332–337. doi: 10.1007/s002940050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selosse M-A, Jacquot D, Bouchard D, Martin F, Le Tacon F. Temporal persistence and spatial distribution of an American inoculant strain of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor in European forest plantations. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:561–573. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selosse M-A, Martin F, Le Tacon F. Survival of an introduced ectomycorrhizal Laccaria bicolor strain in a European forest plantation monitored by mitochondrial ribosomal DNA analysis. New Phytol. 1999;140:753–761. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomson B D, Hardy G E S, Malajcuk N, Grove T S. The survival and development of inoculant ectomycorrhizal fungi on roots of outplanted Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Plant Soil. 1996;178:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timonen S, Tammi H, Sen R. Outcome of interactions between genets of two Suillus spp. and different Pinus sylvestris L. genotype combinations: identity and distribution of ectomycorrhiza and effects on early seedling growth in N-limited nursery soil. New Phytol. 1997;137:691–702. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villeneuve N, Le Tacon F, Bouchard D. Survival of inoculated Laccaria bicolor in competition with native ectomycorrhizal fungi and effects on the growth of outplanted Douglas-fir seedlings. Plant Soil. 1991;135:95–170. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Visser S. Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in jack pine stands following wildfire. New Phytol. 1995;129:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu J, Kerrigan R W, Sonnenberg A S, Callac P, Horgen P A, Anderson J B. The indigenous coastal Californian population of the mushroom Agaricus bisporus, a cultivated species, may be at risk of extinction. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:19–34. [Google Scholar]