Abstract

Inherited microorganisms can selfishly manipulate host reproduction to drive through populations. In Drosophila melanogaster, germline expression of the native Wolbachia prophage WO proteins CifA and CifB cause cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) in which embryos from infected males and uninfected females suffer catastrophic mitotic defects and lethality; however, in infected females, CifA expression rescues the embryonic lethality and thus imparts a fitness advantage to the maternally transmitted Wolbachia. Despite widespread relevance to sex determination, evolution, and vector control, the mechanisms underlying when and how CI impairs male reproduction remain unknown and a topic of debate. Here, we use cytochemical, microscopic, and transgenic assays in D. melanogaster to demonstrate that CifA and CifB proteins of wMel localize to nuclear DNA throughout the process of spermatogenesis. Cif proteins cause abnormal histone retention in elongating spermatids and protamine deficiency in mature sperms that travel to the female reproductive tract with Cif proteins. Notably, protamine gene knockouts enhance wild-type CI. In ovaries, CifA localizes to germ cell nuclei and cytoplasm of early-stage egg chambers; however, Cifs are absent in late-stage oocytes and subsequently in fertilized embryos. Finally, CI and rescue are contingent upon a newly annotated CifA bipartite nuclear localization sequence. Together, our results strongly support the Host modification model of CI in which Cifs initially modify the paternal and maternal gametes to bestow CI-defining embryonic lethality and rescue.

In Drosophila melanogaster, germline expression of the Wolbachia proteins CifA and CifB causes cytoplasmic incompatibility, but how this impairs male reproduction remains unclear. This study shows how Cif proteins encoded by the endosymbiont prophage invade the fly’s gametic nuclei and modify the histone-protamine transition of spermatogenesis.

Introduction

Numerous animal species harbor heritable microorganisms that alter host fitness in beneficial and harmful ways. The most common, maternally inherited bacteria are Wolbachia that typically reside intracellularly in reproductive tissues of both male and female arthropods. Here, they induce reproductive modifications with sex specific effects such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) that can selfishly drive the bacteria to high frequencies in host populations. CI also notably yields important consequences on arthropod speciation [1–3] and vector control strategies [4–9] by causing lethality of embryos from Wolbachia-infected males and uninfected females. As CI is rescued by Wolbachia-infected females with the same strain [10,11], the phenotype accordingly imparts a relative fitness advantage to infected females that transmit the bacteria [12].

Two genes, CI factors cifA and cifB, occur in Wolbachia prophage WO within the eukaryotic association module enriched for arthropod functions and homology [13–15]. We previously demonstrated that dual, transgenic expression of cifA and cifB from wMel Wolbachia in Drosophila melanogaster males induces CI, while single expression of cifA in females rescues CI [16,17]. These results form the basis of the Two-by-One genetic model of CI for several, but not all, strains of Wolbachia [13,15,18,19]. At the cellular level, CI-defining lethality associates with chromatin defects and mitotic arrest within the first few hours of embryonic development. Normally, after fertilization, the sperm-bound “protamines” are removed in the embryo and replaced by maternally supplied “histones,” resulting in the rapid remodeling of the paternal chromatin [20]. However, during CI, there is a delay in the deposition of maternal histones onto the paternal chromatin, resulting in altered DNA replication, failed chromosome condensation, and various mitotic defects that generate embryonic death [13,21–27].

The incipient, prefertilization events in the reproductive tissues that establish CI and rescue remain enigmatic and under recent debate, namely whether (i) Cifs modify the paternal genome during spermatogenesis (Host modification model) or embryogenesis (Toxin–antidote model) and (ii) rescue occurs or does not occur by CifA binding CifB in the embryo [28,29]. These 2 key observations can conclusively differentiate the mechanistic models of CI, although they have not been explicitly addressed to date. Notably, paternal transmission of the proteins from sperm to embryo may occur under either mechanistic model [11,29]. Recent work proposed the Toxin–antidote model is operational using transgenic, heterologous expression of Cif proteins from wPip Wolbachia [30]. In this study, the CifBwPip protein paternally transfers to the fly embryo and associates with DNA replication stress of the paternal genome in the embryo. However, without the ability to rescue this non-native, transgenic CI and thus visualize CifA-CifB binding in the rescue embryo, these interesting results do not yet resolve the predictions of the 2 models. Additionally, the paternal DNA replication defects observed in the embryos may be established before fertilization by the Cif proteins, in concordance with Host modification model.

Here, we develop antibodies to localize Cif proteins from wMel Wolbachia during D. melanogaster gametogenesis and embryogenesis and then perform genome integrity measurements of developing sperm across transgenic, mutant, and wild-type treatment groups. We describe the following cell biological and gametic chromatin events underpinning the Host modification model of CI and rescue: (i) CifA and CifB proteins localize to the developing sperm nuclei from early spermatogonium stage to late elongating spermatids; (ii) in mature sperm, CifA associates with sperm tails and occasionally occurs in the acrosome, whereas CifB localizes to the acrosome in all mature sperms; (iii) Cifs increase histone retention in developing spermatids and decrease protamine levels in mature sperms; (iv) both CI and rescue are dependent upon a newly annotated bipartite nuclear localization signal (bNLS) in CifA that impacts nuclear localization and sperm protamine levels; (v) during copulation, both Cif proteins transfer with the mature sperm exhibiting reduced protamine levels; importantly, protamine mutant flies enhance wild-type CI; (vi) in the ovaries, CifA is cytonuclear in germline stem cells and colocalizes with Wolbachia in the nurse cell cytoplasm; and (vi) CifA is absent in the embryos, and, thus, rescue must be established in oogenesis independently of CifA’s presence in the embryo. Taken together, results demonstrate that prophage WO-encoded Cif proteins from Wolbachia invade gametic nuclei to modify chromatin integrity at the histone to protamine transition stage in males. At the mechanistic level, results support the Host modification model of CI and rescue whereby native Cifs wield their impacts prior to fertilization.

Results

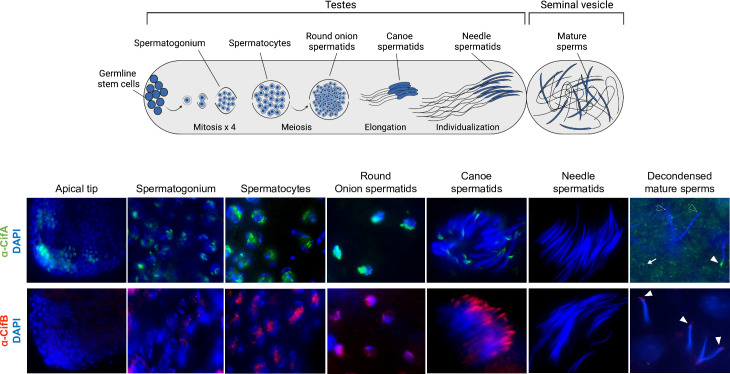

CifA and CifB invade sperm nuclei during spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis

To evaluate the cellular localization of the Cif proteins, we generated monospecific polyclonal antibodies for visualizing the proteins in reproductive tissues (S1 Fig). In D. melanogaster males, the sperm morphogenesis process is subdivided into 2 events: (i) spermatogenesis including mitotic amplification and meiotic phases; and (ii) spermiogenesis, a postmeiotic phase. During spermatogenesis, the germline stem cell undergoes 4 rounds of synchronous mitotic divisions to produce 16 precursor cells called spermatogonia. The spermatogonia then grow and become spermatocytes [31]. After the growth phase, the spermatocytes divide by meiosis and differentiate into 64 haploid round onion spermatids. Postmeiosis, the round sperm nuclei elongate to gradually change their shape accompanied by reorganization of the chromatin during the canoe stage [32]. This results in an individualization complex forming slim, needle-shaped sperm nuclei with reduced volume [31,32]. Elongation and individualization of the spermatids is the final stage of spermiogenesis, after which the mature sperms are transported to the seminal vesicle [31,33].

CifA, but not CifB, localizes in the germline stem cells at the apical end of testes in <8-hour-old cifA and cifB transgene-expressing (Fig 1) and wild-type wMel+ males (S2 Fig). CifA and CifB were both detected in the nuclei of mitotic spermatogonium and spermatocytes. CifA is more abundant than CifB in the spermatogonium stage (S3A Fig and S1 Table). In the postmeiotic, round onion spermatids, clusters of both CifA and CifB are adjacent to the nuclei. In the elongating canoe-shaped spermatids, CifA and CifB localize apical to the sperm head nucleus, in what is likely the acrosome (Figs 1 and S2). CifB is present in all of the spermatid nuclei, whereas CifA is present on average in 39% of the elongating spermatids per sperm bundle (S3B Fig). During the elongating canoe stage, chromatin-bound histones are typically removed and replaced with protamines to yield compact nuclear packaging and chromatin organization of sperm DNA [32]. After nuclear compaction is complete, neither of the Cif proteins are detectable in late spermatid needle-shaped nuclei (Fig 1) and in the mature sperms from the seminal vesicle (S4 Fig), indicating either the Cif proteins are fully stripped or they might not be accessible by the antibodies when the chromatin is tightly compacted [34,35]. To evaluate Cif presence/absence in the mature sperm, we decondensed sperms after isolations from seminal vesicles of <8-hour-old males (see Methods) and stained them with the respective Cif antibodies. CifA is common along sperm tails in a speckled pattern (Figs 1 and S2) and infrequently present in the acrosome region, on average in 45% or 0% of the mature sperm heads depending upon the sampled seminal vesicles (S3B Fig). CifB is present in all of the acrosomal tips of the sperms and not localized to the sperm tails (Figs 1 and S2).

Fig 1. CifA and CifB invade sperm nuclei during spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis.

Schematic representation of Drosophila melanogaster male reproductive system created with Biorender.com is shown on the top. Testes (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males expressing dual transgenes cifAB were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) during sperm morphogenesis. DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. CifA, but not CifB, localizes in the germline stem cells at the apical end of testes. Both CifA and CifB localize in the nuclei of mitotic spermatogonium, spermatocytes, and round onion stage spermatids. In the later stages of spermiogenesis, elongating spermatids harbor CifA and CifB at the acrosomal tip of the heads. CifB is present in all canoe-stage spermatid nuclei, whereas CifA is present on average in 39% of spermatids per bundle. Cifs are not accessible by the antibodies in the tightly compacted spermatids at the needle stage. After decondensing mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles (see Methods), CifA and CifB are detectable in the acrosome regions at varying percentages. CifA is common among sperm tails in a speckled pattern (white arrow) and either present on average in 45% or 0% of the mature sperm heads depending upon the sampled seminal vesicles. CifA’s presence in the acrosome region is shown by solid white arrowheads and absence with empty white arrowheads. CifB is present in acrosomal tips of all of the sperms (solid white arrowheads) and does not occur with sperm tails. CifA and CifB localization patterns are similar in wild-type (wMel+) line and signals are absent in Wolbachia-uninfected (wMel−) negative control line (S2 Fig). Some of the CifA and CifB proteins are also stripped by the individualization complex into the cytoplasmic waste bag (S5 Fig). The experiment was repeated in 2 biological replicates.

During spermatogenesis, Wolbachia are stripped into the cytoplasmic waste bags, which eliminate excess cytoplasmic material during the process of spermatid elongation [23]. Here, we show that some CifA and CifB proteins are also stripped by the individualization complex into the cytoplasmic waste bag (S5 Fig). Since Wolbachia are not present in the mature sperms [36,37], these data suggest that the Cif proteins exit Wolbachia cells during spermatogenesis to possibly interact with and modify sperm DNA (see below). Taken together, these findings demonstrate CifA and CifB proteins access Drosophila sperm nuclei throughout development.

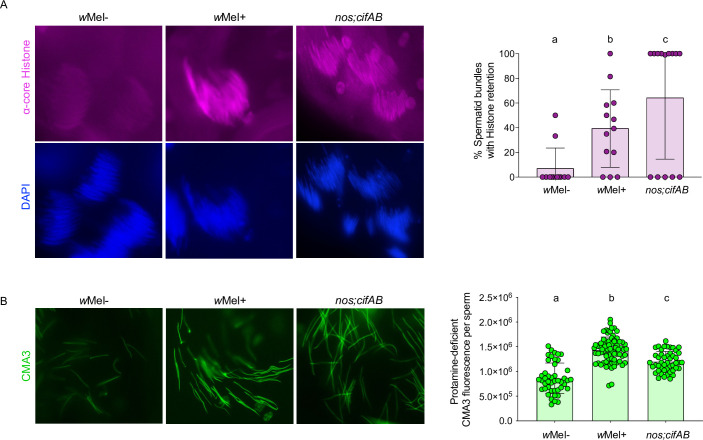

Cifs cause abnormal histone retention and protamine deficiency

Since the Cifs localize to developing sperm nuclei during spermatogenesis, we hypothesized that they may incipiently interact with nuclear DNA to impact sperm genome integrity—a central prediction of the Host modification model of CI [11,29]. At the histone-to-protamine transition stage during spermiogenesis [38], histones normally undergo various posttranslational modifications (PTMs) for removal and replacement by smaller protamines for tight chromatin reorganization [38–41]. Lack of PTMs can lead to histone-bound chromatin with improper protamine deposition that causes paternal chromatin defects, male infertility, and embryonic lethality [27,42,43]. Thus, the incipient defects initiated in the testes can lead to postfertilization catastrophes.

Utilizing a core histone antibody, we investigated histone abundance within spermatid bundles at the late canoe stage in CI- and non-CI causing males. We detected significantly increased histone retention in both wMel+ and cifAB-expressing testes from <8-hour-old males compared to the negative controls (Figs 2A and S6 and S1 Table). Single transgenic expression showed significantly less histone-retaining bundles at this stage similar to wMel− negative controls (S7A Fig and S1 Table). To detect if abnormal histone retention is linked with protamine deficiency in mature sperms, we next used the fluorochrome chromomycin A3 (CMA3) stain that fluoresces upon binding to protamine-deficient regions of DNA [44,45]. Mature sperms isolated from wild-type seminal vesicles of young (high CI inducing) wMel+ males exhibit increased protamine deficiency relative to wMel− males (Fig 2B and S1 Table).

Fig 2. Cifs cause histone retention in late canoe spermatids and protamine deficiency in mature sperms.

(A) Testes (n = 15) from <8-hour-old males of wMel+, wMel−, and transgenic cifAB lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize and quantify spermatid bundles with histone retention (purple) during late canoe stage of spermiogenesis. DAPI stain (blue) was used to label spermatid nuclei. Total spermatid bundles with DAPI signals and those with retained histones were manually counted and graphed. Compared to the negative control wMel−, wMel+ Wolbachia and dually expressed cifAB transgenic lines show abnormal histone retention in the late canoe stage. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by pairwise comparisons based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (B) Mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles (n = 15) of <8-hour-old males reared at 21°C were stained with fluorescent CMA3 (green) for detection of protamine deficiency in each individual sperm nucleus. Individual sperm head intensity was quantified in ImageJ (see Methods) and graphed. wMel+ and transgenic cifAB lines show enhanced protamine deficiency levels compared to wMel− control. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table. The experiments were performed in 2 independent biological replicates and samples were blind-coded for the first run. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file. CMA3, chromomycin A3.

To investigate if lack of protamines associates with CI, we isolated sperms from <8-hour-old males with a protamine A and B knockout mutant line. We show that protamine mutants, both in the presence (ΔProt+) and absence (ΔProt−) of Wolbachia, also exhibit a significant increase in fluorescence relative to wMel− (Fig 3A and S1 Table). Moreover, a key outcome of higher protamine deficiency in ΔProt+ males with Wolbachia is an increase in CI compared to wild-type wMel+ CI, under the same experimental setup (Fig 3B and S2 Table). These findings indicate an additive effect by Wolbachia and ΔProt knockouts on the protamine deficiency and CI penetrance. Notably, ΔProt− males do not recapitulate CI on their own; thus, the protamine deficiency is not the sole cause of CI and must operate in conjunction with other CI modifications. Consistent with these results, 7-day-old wMel+ males that express almost no CI exhibit a similarly weak protamine deficiency level to wMel− males, as expected (S8A and S8B Fig and S2 Table). Moreover, transgene analyses specify both single and dual expression of CifA and CifB cause protamine deficiencies at significantly higher levels than negative controls of wMel− and a non-CI transgene (S7B Fig and S1 Table). Since singly expressed Cifs do not cause CI in D. melanogaster [16] (S7C Fig and S2 Table), additive effects on the protamine deficiency and/or histone retention due to abnormal PTMs may be required to fully establish CI.

Fig 3. Protamine mutants enhance wild-type CI and show significantly increased levels of protamine deficiency in mature sperms.

(A) Sperms from the Wolbachia-infected (ΔProt+) and Wolbachia-uninfected (ΔProt−) protamine mutant (w[1118]; ΔMst35B[floxed], Sco/CyO) males exhibit significantly increased CMA3 fluorescence indicative of protamine deficiency compared to both wild-type wMel+ and wMel−. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table. (B) CI hatch rate analyses of male siblings used in CMA3 assays (panel A) validate that ΔProt+ males with increased sperm protamine deficiency cause stronger (rescuable) CI levels than wMel+. ΔProt− males do not cause CI. Asterisks indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by pairwise Mann–Whitney tests. All of the p-values related to CI assay are reported in S2 Table. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file. CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility; CMA3, chromomycin A3.

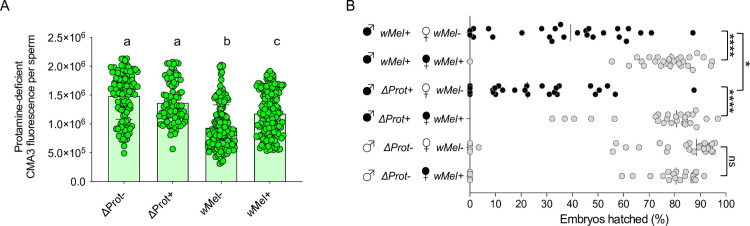

Both CI and rescue are dependent upon a CifA bNLS

Based on the cNLS mapping tool for nuclear localization signals [46], CifA amino acids harbor a predicted bipartite nuclear localization sequence (S3 Table) in the most conserved region of the protein [13,47,48] that is under strong purifying selection [17]. As nuclear localization signals bind to the extended surface groove of nuclear transport protein importin-α, also known as karyopherin-α [49], we hypothesized that sperm nuclear localization of CifA, and CI and rescue are dependent on the bNLS. To test this hypothesis, we mutagenized 2 bNLS sequences with alanine substitutions (aa189-190 for NLS1 (denoted cifA189) and aa224-225 for NLS2 (denoted cifA224)), and we additionally deleted the entire bNLS region (cifAΔbNLS) (Fig 4A). The bNLS deletion also corresponds to the weakly predicted catalase-rel domain in CifA [47,48].

Fig 4. A nuclear localization signal in CifA is necessary for CI, rescue, and protamine levels.

(A) Schematic representation of CifA annotation shows the annotated bNLS with engineered amino acid substitutions and deletions. (B, C) Hatch rate assays assessed both CI (B) and rescue (C) in flies expressing wild-type, transgenic, and mutant cifA. Each dot represents the percent of embryos that hatched from a single male and female pair. Sample size is listed in parentheses. Horizontal bars represent the median. Letters to the right indicate significant differences determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple comparison tests. All the p-values are reported in S2 Table. (D) Antibody labeling (green) and DAPI staining of onion stage spermatids in the testes of the bNLS mutant line (cifAΔbNLS) reveals that the deletion ablates CifA’s localization to the nucleus, and CifA thus remains in the surrounding cytoplasm. The imaging experiment was conducted in parallel to nos;cifAB line shown in Fig 1. (E) Mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles (n = 15) of <8-hour-old males of transgenic cifAΔbnlsB line shows reduced fluorescence indicative of less Protamine deficiency compared to cifAB. To control for any background confounding effects of nos-Gal4VP16 driver line, wMel− fathers were prior crossed to nos- mothers to generate males with nos;wMel− genotype. CMA3 fluorescence levels of sperms isolated from nos;wMel− males were similar to wMel− wild-type lines used in previous assays in this study. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table, and raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file. bNLS, bipartite nuclear localization signal; CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility.

Each bNLS mutant, individually and together (cifA189;224), was dually expressed in testes with transgenic, intact cifB to assess CI and singly expressed in females to assess rescue. Transgenic cifA189 expression significantly reduced CI and rescue as previously reported (Fig 4B and 4C and S2 Table) [48]. Conversely, transgenic cifA224 expression showed no significant difference from the controls in either CI or rescue, suggesting this region has little to no impact. However, when both mutants are expressed in cifA189;224 or when the entire bNLS is deleted, CI and rescue are strongly inhibited (Fig 4B and 4C and S2 Table). These results highlight the importance of the nuclear localization sequence in inducing CI as well as rescue. To determine if the lack of CI induction is due to nonnuclear localization of CifA protein, we used the deletion mutant cifAΔbNLS with wild-type cifB to demonstrate that in contrast to its normal, nuclear localization (Fig 1), it mislocalizes to the cytoplasm of onion stage spermatids rather than the nuclei (Fig 4D). Additionally, to test if deletion of the bNLS impacts sperm genomic integrity, we performed a CMA3-based protamine deficiency assay (as described above) and found reduced protamine deficiency levels in matures sperms due to non CI-causing cifAΔbNLS;B line compared to CI-causing cifAB (Fig 4E and S1 Table), providing further evidence that protamine deficiency is linked to CI. Overall, these data provide previously unknown findings that a functional nuclear localization sequence and CifA nuclear localization impacts CI, rescue, and sperm protamine levels.

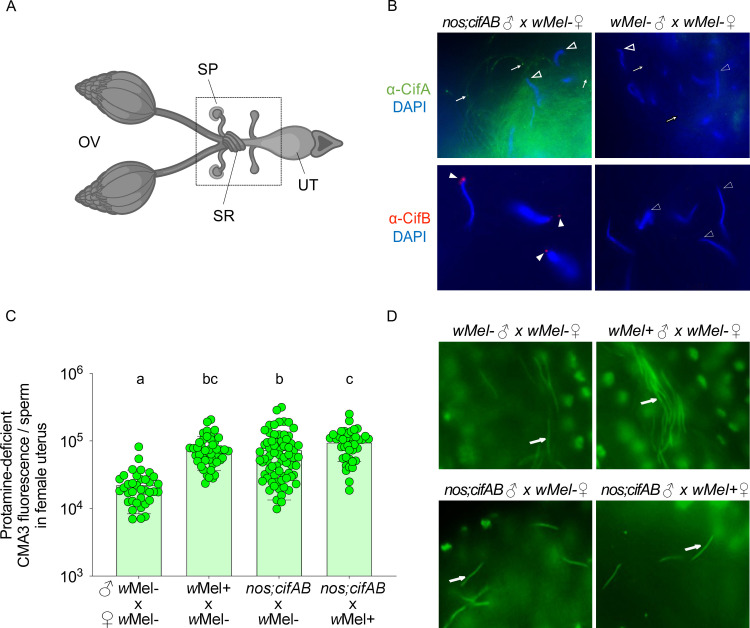

Cifs cause a paternally transferred protamine deficiency

To investigate if Cif proteins and/or the genome integrity modifications transfer paternally to the female reproductive tract, single male:female pairwise matings were set up for CI and rescue crosses. After 4 hours of mating, we isolated the whole uterus (Fig 5A) including the sperm storage organs (spermathecae (SP) and seminal receptacle (SR)). Following sperm decondensation, antibody staining, and microscopy, we observed 2 key results. First, both CifA and CifB proteins transfer with sperm tails and heads, respectively, to the sperm storage organs of Wolbachia-free females (Fig 5B). Second, the CI-associated sperm protamine deficiency induced by wMel+ and cifAB-expressing males transfers and persists in the sperms isolated from SP and SR of Wolbachia-free, mated females (Fig 5C and 5D and S1 Table). These findings connect a paternally transferred sperm modification with the activity of Wolbachia and the Cifs themselves. Results strongly support the Host modification model of CI since a Cif-induced sperm modification established in the testes transfers to the female reproductive tract.

Fig 5. CifA, CifB, and the protamine deficiency are transferred with the mature sperm to the female reproductive tract.

(A) Schematic representation of Drosophila melanogaster female reproductive system. Mature oocytes leave the OV and reach the UT, where they can be fertilized prior to being laid. Sperms from males are stored in specialized organs—SP and SR shown in the box, which open into the UT for fertilization to occur. Schematic is created with BioRender.com. (B) Transgenic cifAB-expressing and wMel− males were crossed to wMel− females. Four hours postfertilization, sperms isolated from females were decondensed and immunostained for localizing CifA (green) and CifB (red). DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. CifA is absent in sperm heads (empty arrowheads) and puctae are seen along the sperm tails (arrows). CifB is present in apical acrosomal tip of all of the sperm heads (solid arrowheads), with more distant signal in the more decondensed sperm nuclei. No Cifs are present in the sperms transferred from wMel− negative control males. (C) Individual sperm intensity quantification shows that protamine deficiency of sperms from wMel+ and transgenic cifAB males persists after transfer in the females compared to wMel− males. Sperm protamine deficiency from transgenic cifAB males also persists in the reproductive tract of wMel+ females. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table, and raw data underlying this panel can be found in S1 Data file. (D) Representative images of CMA3-stained mature sperms (arrows) transferred from wMel−, wMel+ and transgenic cifAB males in wMel− and wMel+ female reproductive systems are shown. CMA3, chromomycin A3; OV, ovary; SP, spermathecae; SR, seminal receptacle; UT, uterus.

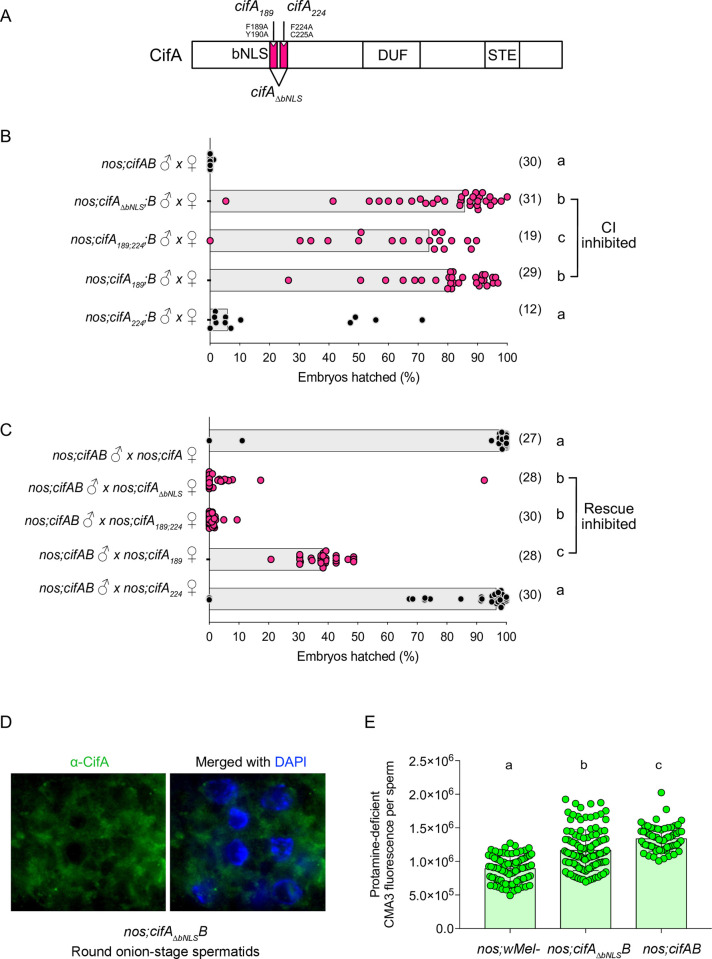

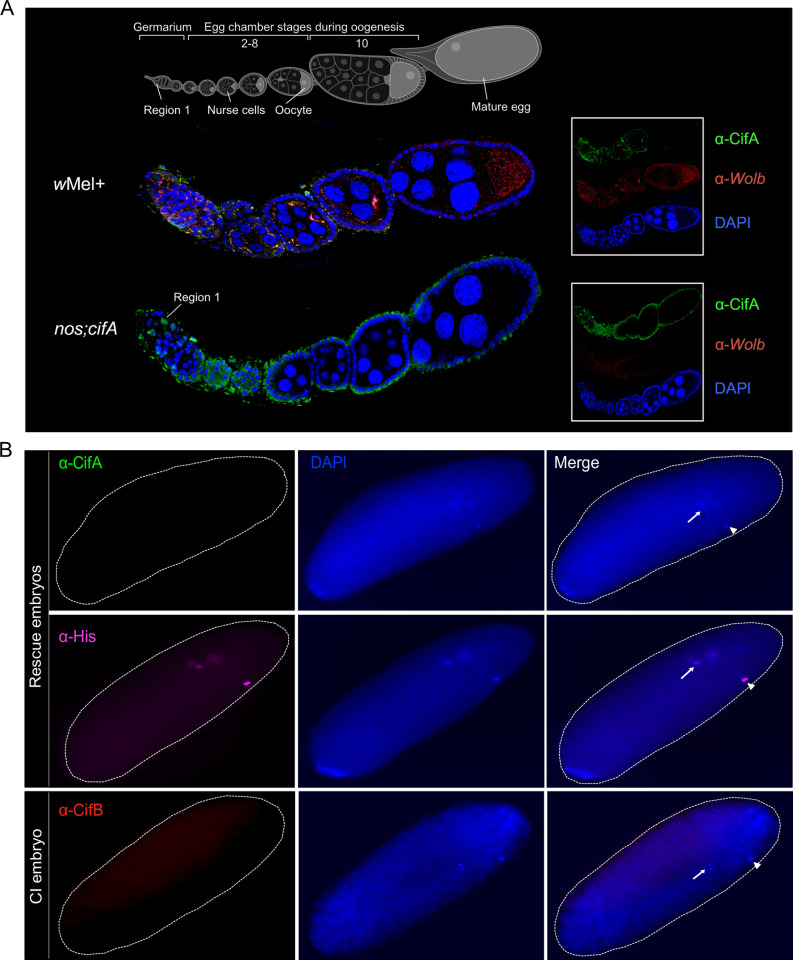

CifA is present in early oogenesis and absent from mature eggs and rescue embryos

Expression of cifA alone in the ovaries rescues CI [16,17], yet how CifA protein mediates rescue is unknown and central to further differentiating the mechanistic models of CI. For instance, CifA in females may modify reproductive cell biology to nullify CI-inducing sperm modifications in the embryo (Host modification), or, alternatively, CifA may directly bind CifB in the embryos to prevent its proposed CI toxicity (Toxin–antitoxin). Using CifA antibodies, we show in wMel+ and cifA transgene-expressing ovaries that CifA protein is cytonuclear and specifically localizes to cyst DNA in region 1 of the germarium (Fig 6A), indicative of nuclear access in ovaries similar to that in testes (Fig 1). Cystoblast in the germarium undergoes rounds of mitotic divisions to produce oocyte and nurse cells [50,51]. Along egg chamber stages 2 to 8 of wMel+ females, CifA colocalizes with Wolbachia in the nurse cells and oocyte cytoplasm (Fig 6A). While Wolbachia are abundant in the stage 10 egg chamber, CifA is notably absent. In transgenic females, CifA is also primarily detected in the germarium and cytoplasm of the early egg chambers and absent in late egg chambers (Figs 6A and S9A). Presence of high levels of CifA in Wolbachia-infected eggs is proposed to rescue CI; importantly, we did not detect CifA in approximately 30- to 60-minute-old rescue embryos during early mitotic divisions (Fig 6B). Moreover, CifA was not detected in 1- to 2-hour-old embryos (S9B Fig), whereas the positive control histone signals colocalize with embryonic DNA at both embryonic developmental stages.

Fig 6. CifA is present in early oogenesis and absent in late-stage egg chambers.

Both CifA and CifB are absent in CI and rescue embryos. (A) Schematic representation of Drosophila melanogaster ovariole at the top illustrates the stages of oogenesis from left to right. Image was created with BioRender.com. Immunostaining assay indicates localization of CifA (green) to the cyst DNA (blue labeled with DAPI) in region 1 of the germarium of Wolbachia-uninfected transgenic cifA line. In wMel+ line, CifA colocalizes with Wolbachia (red) in the germarium, nurse cells and oocyte cytoplasm along 2–8 stages of egg chambers. CifA is absent in stage 10 egg chamber, whereas Wolbachia signals persist. In the transgenic cifA line, we note the observed autofluorescence in green channel outlining the tissue morphology does not signify CifA signals. Ovariole images were manually adjusted in Affinity designer software to align egg chamber stages in the same plane. (B) Immunofluorescence of CifA (green) and CifB (red) in approximately 30- to 60-minute-old embryos obtained from rescue (cifAB male × wMel+ female) and CI crosses (nos;cifAB male × wMel− female). Histone antibody labeling core-histones (magenta) was used as a positive control. Histone signals were detected colocalizing with host DNA, labeled with DAPI (blue), whereas no CifA and CifB signals were detected. Dotted white embryonic periphery is drawn around the embryo shape. White arrows indicate dividing nuclei post fertilization and arrowheads indicate polar bodies. CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility.

CifB from wPip was recently shown to be paternally transferred to the CI embryos [30]. We evaluated if wMel CifB colocalizes with mitotic, embryonic DNA after fertilization. CifB is absent from embryonic nuclei and the cytoplasm of CI embryos (Fig 6B), suggesting that CifB is not inherited with the paternal DNA to the embryo. The absence of CifA and CifB in late wild-type and transgenic eggs and embryos indicates that host gametic changes prime the embryo for CI and rescue before fertilization, as predicted by the Host modification model of CI. This inference is also consistent with previous studies where ovarian, rather than embryonic, transgenic cifA expression rescues CI [13,15–17,52].

Discussion

At the genetic level, dual expression of cifA and cifB or single expression of cifB can recapitulate CI, and cifA rescues CI [13,15–19,52]. However, the cellular and mechanistic bases of CI and rescue remain unresolved and the subject of several questions: When and where do the Cif proteins localize in testes to potentiate CI? Are the Cifs transferred to the embryo already modified for CI-defining defects? Do CifA and CifB bind in the embryo to rescue lethality? Here, we establish that both CifA and CifB proteins invade nuclei of developing spermatids and modify paternal genome integrity by altering the histone–protamine transition process. Specifically, dual CifA and CifB expression induces abnormal histone retention and protamine deficiency in CI-causing male gametes to induce CI. Moreover, knocking out protamines enhances wild-type CI, and a nuclear localization sequence in CifA is essential for CI, rescue, and protamine deficiency. Finally, binding of CifA and CifB in the embryo is not evident.

Sperm genome compaction is normally achieved during the postmeiotic canoe phase of spermiogenesis, when histones are replaced by protamines [53]. This compaction process is highly conserved from flies to humans [54–56] and plays a crucial role in successful fertilization and embryonic development [57,58]. Histone marks are carriers of transgenerational epigenetic information [59], and changes in the sperm epigenome can lead to detrimental consequences including early embryonic lethality and birth defects [59,60]. Histones undergo various PTMs such as ubiquitination, methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation before degradation and removal from the sperm chromatin [38]. Therefore, abnormally retained histones could result from aberrant PTMs in Cif-expressing flies. In a protein interactome screen, both ubiquitin and histone H2B were determined as binding host candidates to CifB [52]. Thus, it is possible that inhibition of the histone ubiquitination process mediates abnormal histone retention. Additionally, histone acetylation during the canoe stage of spermiogenesis is required for histone eviction in Drosophila [61]. Indeed, reduced acetylation levels lead to abnormal histone retention and protamine deficiency, which causes embryonic inviability in flies [61] and in mammals [40,62,63]. Future research investigating what specific PTMs are altered at the histone–protamine transition stage will help elucidate the molecular pathway(s) leading to CI.

The paternally derived Cif proteins travel with the sperms to the female reproductive tract, where CifB is present in the acrosomal region and CifA occurs along the tail. Notably, both Cifs are not evident in the embryos. While the presence of paternally transferred Cifs is ambiguous to the mechanistic models of CI [11,29] and recently confirmed in another transgenic study [30], it is the presence of CifA-CifB binding in the rescue embryo that would support the Toxin–antitoxin model. However, there is no evidence of this binding phenomenon in the embryos to date. Thus, we conclude that Cifs act before fertilization to prime the sperm chromatin and incipiently launch CI. Paternal effect proteins can modify sperm in various systems to bestow embryonic defects, even though the proteins themselves do not transfer to the embryos [60,64,65].

In Drosophila, the sperm enters the egg with an intact membrane [66]. Therefore, absence of Cifs in the embryos raises the question at what point CifA along the tail and CifB in the acrosome are lost before the sperm enters the egg. One possible explanation is that the Cif proteins are released from the sperm upon exocytosis of the acrosome. The acrosome, best known as a secretory vesicle, undergoes exocytosis and releases its contents to facilitate sperm-egg binding in mammals [67,68]. Although not well characterized in insects, studies in the house fly Musca domestica suggest loss of the sperm plasma membrane before entry into the egg, followed by exocytosis of acrosomal contents during passage of the sperm through the egg micropyle [69].

CifA is absent in Wolbachia-infected and transgenic embryos, which indicates that rescue is established during oogenesis under the Host modification model, and CifA thus does not bind and nullify CifB from wMel Wolbachia in the embryos. Indeed, a CifA mutant in the newly annotated nuclear localization sequence ablates rescue, suggesting that access to ovarian nuclei is important for rescue. Interestingly, structures of CifA and CifB support binding of the 2 proteins [70], yet in light of these results here, the CifA-CifB binding may be central to CI induction instead of rescue. Moreover, mutating amino acid sites across the length of the CifA protein, including binding and nonbinding residues, generally ablates CI and rescue [48,70]. Thus, it is possible that CifA mutants that ablate rescue do so by altering the protein structure, function, and/or location of ovarian targets to modify, rather than the embryonic binding of CifA to CifB in vivo. Future work will be important to resolve how CifA primes oogenesis to alter specific cell biological and biochemical events that underpin rescue.

Once fertilization occurs, protamines from the paternal chromatin must be removed and replaced by maternal histones to decondense and activate the chromatin of the developing embryo [71]. Interestingly, postfertilization delays in maternal H3.3 histone deposition occur in CI embryos [21]. The delay may in part be due to preloaded paternal histones or altered paternal epigenome information leading to mistiming of maternal histone deposition, hence causing CI. Thus, we propose that a genome integrity network involving histones, protamines, and possibly other factors in the gametes may be a common and defining feature underpinning the onset of CI and rescue.

Altogether, discovery of nuclear-targeting Cif proteins in male and female gametes establishes new insights on the early cell biological and biochemical steps that underpin the CI drive system with relevance to arthropod speciation and pest control [11]. In addition to disentangling the reproductive events of the Cif proteins that control gametogenesis and embryogenesis, the evidence specifies that the Cif proteins modify sperm genomic integrity and transfer paternally, but they themselves do not enter and bind each other in the embryo to enable rescue. These findings are consistent with the Host modification model of CI by wMel Wolbachia. More generally, as there are no previous reports of prophage proteins invading animal gametic nuclei to impair the histone–protamine transition during spermiogenesis, the findings have implications for expanding an appreciation of prophage–bacteria–eukaryote interactions into the realm of animal reproduction.

Methods

Cif proteins antibody development

Conserved amino acid regions of CifA and CifB proteins from wMel Wolbachia were previously identified [47]. Using these regions, monospecific polyclonal antibodies were commercially generated by Pacific Immunology (Ramona, CA) through injection of 3 synthesized and conserved short (20 aa) peptides for each protein into rabbits. Sequences of peptides were Cys-EYFYNQLEEKDKEKKLTE for CifA and Cys-DENPPENLLSDQTRENFRR for CifB. The resulting α-CifA and α-CifB antibodies were evaluated using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and titers were determined to be higher than 1:500,000 for each antibody. Using standard protocols of the Invitrogen WesternDot kit (#W10142, Carlsbad, CA), antibody specificity to wMel+ samples was verified using western blots (1:1,000-fold antibody dilution) on protein isolated from homogenates of 50 testes pairs (0- to 8-hour-old males) and 10 ovary pairs (6-day-old females) from wMel+ (positive), wMel− (negative control), and cifAB transgenic (positive) flies. The correct size band was only detected from wMel+ and cifAB reproductive tissues (S1 Fig). Because the antibodies were generated in the same animal, all subsequent labeling was done with individual antibodies.

NLS identification

CifA amino acid sequences from known Wolbachia and close relatives were input into the cNLS Mapper software [72] to identify putative NLS sequences within each protein (S3 Table). cNLS Mapper identifies sequences specific to the importin α/β pathway. A cutoff score of 4 was applied to all sequences. Higher scores indicate stronger NLS activities. Scores >8 indicate exclusive localization to the nucleus, 7 to 8 indicate partial localization to the nucleus, 3 to 5 indicate localization to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and score 1 to 2 indicate localization exclusively to the cytoplasm. Predicted NLS sequences are divided into monopartite and bipartite classes. Monopartite NLSs contain a single region of basic residues, and bipartite NLSs contain 2 regions of basic residues separated by a linker region.

Development of transgenic lines

A cifA variant was synthesized de novo at GenScript and cloned into a pUC57 plasmid as described previously [48]. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by GenScript to produce the mutants outlined in Fig 5. The cifA189 variant was first described in Shropshire and colleagues [48] as cifA2. UAS transgenic cifA mutant flies were then generated using previously established protocols [13]. Briefly, GenScript subcloned each gene into the pTIGER plasmid, a pUASp-based vector designed for germline-specific expression. Transgenes were then integrated into y1 M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A w*; P{CaryP}attP40 attachment sites into the D. melanogaster genome using PhiC31 integrase via embryonic injections by BestGene. At least 200 embryos were injected per transgenic construct, and successful transformants were identified based on red eye color gene included on the pTIGER plasmid containing the transgene. All sequences are reported in S4 Table.

Fly rearing and strains

D. melanogaster stocks y1w* (BDSC 1495), nos-GAL4:VP16 (BDSC 4937), UAS transgenic lines homozygous for cifA, cifB, cifAB, WD0508 [13], and Protamine mutant (w[1118]; ΔMst35B[floxed], Sco/CyO) [73] were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 25°C and 70% relative humidity on 50 mL of standard media. Uninfected protamine mutant line was generated by 3 generations of tetracycline treatment (20 μg/ml in 50 ml of fly media) as described in previous studies [13], followed by 2 rounds of rearing on standard food media before using in the experiments. Infection status for all lines was regularly confirmed by PCR using Wolb_F and Wolb_R3 primers [74].

Hatch rates

Parental flies were either wild-type uninfected (wMel−) or infected (wMel+) with Wolbachia or transgene-expressing with no Wolbachia infection. Uninfected transgenic flies were generated previously [13,17]. Paternal grandmother age was controlled to 9 to 11 days for expression of naturally high penetrance of wMel CI [75]. Parental transgenic males were generated through crossing nos-Gal4:VP16 virgin females (aged 9 to 11 days) to UAS-cif transgenic, uninfected males [75]. Mothers were aged 6 to 9 days before crossing, while father males first emerged between 0 and 8 hours were used in hatch rates and tissue collections to control for the younger brother effect associated with lower CI penetrance [13,76].

Hatch rates were set up as described previously [13,17]. Briefly, a male and female pair was placed in an 8 oz, round bottom, polypropylene Drosophila stock bottle with a grape juice agar plate containing a small amount of yeast placed at the base and secured with tape. These bottles were then placed in a 25°C incubator overnight to allow for courting and mating. The following day, these plates were discarded and replaced with new grape juice agar plates with fresh yeast. After an additional 24 hours, the plates were removed, and the embryos were counted. The embryo plates were then incubated for 36 hours at 25°C before the total number of unhatched embryos were counted. Any crosses with fewer than 25 embryos laid were discarded from the analyses. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were determined by pairwise Mann Whitney U tests or by a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction in GraphPad Prism 7. All p-values are listed in S2 Table.

Immunofluorescence: Testes and seminal vesicles

Siblings from the hatch rate (males 0 to 8 hours) were collected for testes dissection in ice-cold 1× PBS solution. Tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde diluted in 1× PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature and washed in 1× PBS-T (1× PBS + 0.3% Triton X-100) 3 times for 5 minutes each. Tissues were then blocked in 1% BSA in PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature. They were then incubated with 1° antibody (α-CifA 1:500 OR α-CifB 1:500) overnight at 4°C rotating. After washing in 1× PBS-T 3 times for 5 minutes each at room temperature, they were incubated with 1:1,000 dilution Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibody (Fisher Scientific, Cat#A11037, CA, USA) for 4 hours at room temperature in the dark. Tissues were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in 1× PBS-T and mounted on slides. To stain the nuclear DNA, 0.2mg/mL of DAPI was added to the mounting media before the coverslip was gently placed over the tissue and excess liquid wiped away. Slides were allowed to dry overnight in the dark before viewing on the Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. All images were acquired with the same parameters for each line and processed in ImageJ as described in [77].

Decondensation of mature sperm nuclei

Squashed seminal vesicles collected from male flies (aged 0 to 8 hours) were treated with 10 mM DTT, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 400 U heparin in 1× PBS for 30 minutes [34]. The slides were then washed quickly in 1× PBS before immunofluorescence staining (see above).

Immunofluorescence and quantification: Histones

Testes from male flies (aged 0 to 8 hours) were fixed and stained as described above for testes. The tissues were stained with a core histone antibody (MilliporeSigma, Cat#MABE71, USA) (1:1,000) and imaged on a Keyence BZ-800 microscope. Total late canoe-stage sperm bundles were quantified in each testis, and those that retained histones were determined. Ratios of late canoe-stage bundles containing histones relative to total bundles from each individual testis were graphed in GraphPad Prism 7. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) were determined by pairwise comparisons based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction in GraphPad Prism 7.

Sperm isolation and CMA3 staining/quantification

Seminal vesicles were collected from male flies (aged 0 to 8 hours for 1-day-old flies and 7 days for older flies) and placed on a microscope slide in ice-cold 1× PBS. Sperm was extracted on the slide using forceps and fixed in 3:1 vol/vol methanol:acetic acid at 4°C for 20 minutes. Excess solution was then removed, and the slide was air dried. Each slide was treated in the dark for 20 minutes with 0.25 mg/mL of CMA3 in McIlvain’s buffer, pH 7.0, with 10 mM MgCl2. Sperm was then washed in 1× PBS, mounted, and imaged using a Keyence BZ-X700 Fluorescence microscope. All images were acquired with the same parameters for each line and did not undergo significant alteration. Fluorescence quantification was performed by scoring fluorescent pixels in arbitrary units (A.U.) within individual sperm heads using ImageJ as per the details described in [77], and calculated fluorescence intensity per sperm head was graphed. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction in GraphPad Prism 7. All of the experiments involving CMA3 staining were performed at 21°C instead of 25°C. CI hatch rate assays were run in parallel to ensure that CI and rescue phenotypes are not impacted due to changed temperature conditions.

Immunofluorescence: Ovaries

Ovaries from females (6 days old) were dissected in 1× PBS on ice and processed as described previously [76,78]. Tissues were blocked in 1% BSA in PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature and were first incubated with α-CifA (1:500) primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After washing in 1× PBS-T 3 times for 5 minutes each at room temperature, they were incubated with 1:1,000 dilution Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#A11034, USA) for 4 hours at room temperature in the dark. Samples were then rinsed properly and blocked again before incubating with α-ftsZ (1:150) primary antibody (a kind gift from Dr. Irene Newton) to stain Wolbachia at 4°C overnight. After washing in 1× PBS-T 3 times, samples were incubated with second secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594) for 4 hours in the dark. Since both CifA and ftsZ antibodies were generated in the same animal, we used secondary antibodies conjugated to 2 distant fluorophores to distinguish specific signals. Tissues were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in 1× PBS, stained with DAPI to label nuclear DNA and mounted on slides. Slides were allowed to dry overnight in the dark before viewing on the Zeiss LSM 880 (USA) confocal microscope.

Immunofluorescence: Embryos

After 24 hours of mating, plates were switched, and embryos were collected every 30 minutes. Embryos were collected in a 100-μm mesh basket in embryo wash solution. To remove the chorion, the basket was placed in 50% bleach for 3 minutes and then rinsed with 1× PBS. The embryos were then transferred to 50:50 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and heptane in a microcentrifuge tube and rotated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Tubes were then removed from the rotator, and the heptane and PFA were allowed to separate before the bottom PFA phase was carefully removed. Methanol was added to the remaining heptane, and the tube was shaken vigorously for 20 seconds before the embryos settled to the bottom and solution was removed. A new volume of methanol was added to the embryos, and they were allowed to settle to the bottom of the tube. Methanol was removed, and all blocking, staining, and imaging steps were carried out for testes and ovary tissues above.

Supporting information

Western blots were run on protein extracted from ovaries (n = 10) of wild-type infected wMel+, uninfected wMel−, cifA transgenic (cifA), and dual cifA;B expressing transgenic lines. The expected size for CifA is approximately 54 kD. Western blots were run using anti-CifB antibody on testes (n = 15) of wild-type infected (+), uninfected (−), and cifA;B transgenic (A;B) lines. Expected CifB size is approximately 133kD. Cifs are absent in wMel− control and present at accurate size in wMel+ and cif expressing lines.

(TIF)

Testes (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males of wild-type wMel+ and wMel− lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) during sperm morphogenesis. DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. CifA and CifB localization patterns in wild-type lines are similar to that of transgenic cifAB (Fig 1) and signals are absent in wMel− uninfected control line. The experiment was conducted in parallel to the one shown in Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) ImageJ-based signal intensity quantification indicates CifA (green) is more abundantly expressed than CifB (red) in the spermatogonium stage of the spermatogenesis. Mean of individual data points with standard deviation is plotted on the graph. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by pairwise comparisons based on a Mann–Whitney test. p-Values are reported in S1 Table. (B) In the decondensed mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles, CifB is present in the acrosomal tip of canoe-shaped spermatids and mature sperm heads, whereas CifA is present in only 40% and 20% of them, respectively. Quantification was performed on the images obtained in Fig 1 data. Each dot represents percentage of Cifs present in spermatids or mature sperms per testes examined. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file.

(TIF)

Seminal vesicles (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males of transgenic cifAB, wild-type wMel+ and wMel− lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) in the mature condensed sperms (indicated by white arrows). DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. Absence of both CifA and CifB indicates that proteins are not accessible to the antibodies when the sperm chromatin is condensed and tightly packed.

(TIF)

Testes (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males of transgenic cifAB, and wild-type wMel− lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) in the cytoplasmic (WBs that are present near the basal end of sperm tail bundles. Some of the Cif proteins strip down in the WB in cifAB line and absent in wMel− control testes. Brightfield is shown to highlight the morphology of sperm tail bundles and WBs, which are otherwise not visible using Cif antibodies and DAPI stain. The experiment was run in parallel to the ones shown in Figs 1 and S2. WB, waste bag.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(A) Testes (n = 15) from <8-hour-old males of single transgene-expressing lines cifA, cifB, and a non CI-causing control gene WD0508 were dissected to quantify spermatid bundles with histone retention (purple) during late canoe stage of spermiogenesis. DAPI stain (blue) was used to label spermatid nuclei. Total spermatid bundles with DAPI signals and those with retained Histones were manually counted and graphed. Single transgenic expressing lines showed significantly less histones similar to the negative control wMel− at the late canoe stage. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. (B) Mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles (n = 15) of <8-hour-old males reared at 21°C were stained with fluorescent CMA3 (green) for detection of protamine deficiency in each individual sperm nucleus. Individual sperm head intensity was quantified in ImageJ (see Methods) and graphed. cifA- and cifB-expressing lines showed significantly higher fluorescence indicative of reduced levels of protamines compared to wMel− and WD0508 control lines. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table. The experiments were performed in parallel to the ones shown in Fig 2. (C) CI hatch rate analyses of transgenic male siblings used in CMA3 assays (Figs 2B and S6) validate that CI crosses (black circles) yielded significantly less embryonic hatching compared to non CI-inducing ones, when reared at 21°C. Letters to the right indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons based on a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S2 Table. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file. CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility; CMA3, chromomycin A3.

(TIF)

(A) Sperms from the 7-day-old wild-type Wolbachia-infected (wMel+) males show similar level of protamine levels as of wMel−. Vertical bars represent mean, and error bars represent standard deviation. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by pairwise Mann–Whitney test. All of the p-values are reported in S1 Table. (B) CI hatch rate analyses of male siblings used in CMA3 assays (panel A) validate that 7d old wMel+ do not induce CI that correlates with their normal levels of sperm protamine levels. Letters to the right indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by multiple comparisons calculated using a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn multiple test correction. All of the p-values are reported in S2 Table. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file. CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility; CMA3, chromomycin A3.

(TIF)

(A) In the transgenic cifA line, CifA (green) is absent in the late oocyte stages. Image was acquired at 20× magnification to show mid and late oocytes in one plane. We note the autofluorescence upon enhanced exposure in the green channel outlining the tissue morphology of stage 15 egg chamber does not signify CifA signals. (B) Immunofluorescence of CifA (green) and histones (magenta) in 1- to 2-hour-old embryos (n = 50) obtained from rescue cross (cifAB male × wMel+ female). Histone signals are detected in the developing embryos colocalizing with host DNA, labeled with DAPI (blue), whereas CifA signals are absent.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Battle for her assistance in fly collections and staining for sperm integrity assays; Alex Mansueto for his assistance in hatch rates; and Sarah Bordenstein, Dylan Shropshire, and Luis Mendez for providing helpful feedback on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Janna McLean for sending the protamine mutant fly line for conducting the experiments. We thank Dr. Irene Newton for sharing the Wolbachia antibody and providing useful feedback on the preprint version of this manuscript. We also thank the Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CISR) at Vanderbilt for imaging assistance.

Abbreviations

- A.U.

arbitrary units

- bNLS

bipartite nuclear localization signal

- CI

cytoplasmic incompatibility

- CMA3

chromomycin A3

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PTM

posttranslational modification

- SP

spermathecae

- SR

seminal receptacle

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Digestive Disease Research Center Scholarships S1848284, S1848300, S1883559 to S.R.B., Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Scholarships S1871288, S1848887, S1848952 to S.R.B., National Institutes of Health Awards R01 AI132581 and AI143725 to S.R.B., F32 AI140694 Ruth Kirschstein Postdoctoral Fellowship to B.A.L., and the Vanderbilt Microbiome Innovation Center to S.R.B. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bordenstein SR, Ohara FP, Werren JH. Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia. Nature. 2001;409:707–10. doi: 10.1038/35055543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlat S, Hurst GDD, Merçot H. Evolutionary consequences of Wolbachia infections. Trends Genet. 2003;19:217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00024-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaenike J, Dyer KA, Cornish C, Minhas MS. Asymmetrical reinforcement and Wolbachia infection in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:1852–62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The Endosymbiotic Bacterium Wolbachia Induces Resistance to Dengue Virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000833. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frentiu FD, Zakir T, Walker T, Popovici J, Pyke AT, van den Hurk A, et al. Limited Dengue Virus Replication in Field-Collected Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Infected with Wolbachia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, McMeniman CJ, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476:450–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourtzis K, Dobson SL, Xi Z, Rasgon JL, Calvitti M, Moreira LA, et al. Harnessing mosquito-Wolbachia symbiosis for vector and disease control. Acta Trop. 2014;132. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes GL, Koga R, Xue P, Fukatsu T, Rasgon JL. Wolbachia infections are virulent and inhibit the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002043. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor L, Plichart C, Sang AC, Brelsfoard CL, Bossin HC, Dobson SL. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a wolbachia biopesticide: field performance and infection containment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor MJ, Bordenstein SR, Slatko B. Microbe profile: Wolbachia: A sex selector, a viral protector and a target to treat filarial nematodes. Microbiol (Reading). 2018. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shropshire JD, Leigh B, Bordenstein SR, Initiative M. Symbiont-mediated cytoplasmic incompatibility: What have we learned in 50 years? Elife. 2020:1–51. doi: 10.7554/eLife.61989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turelli M. Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes and their hosts. Evolution (N Y). 1994;48:1500–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb02192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LePage DP, Metcalf JA, Bordenstein SR, On J, Perlmutter JI, Shropshire JD, et al. Prophage WO genes recapitulate and enhance Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature. 2017;543:243–7. doi: 10.1038/nature21391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordenstein SR, Bordenstein SR. Eukaryotic association module in phage WO genomes from Wolbachia. Nat Commun. 2016;7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckmann JF, Ronau JA, Hochstrasser M. A Wolbachia deubiquitylating enzyme induces cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shropshire JD, Bordenstein SR. Two-by-one model of cytoplasmic incompatibility: Synthetic recapitulation by transgenic expression of cifa and cifb in drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2019;15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shropshire JD, On J, Layton EM, Zhou H, Bordenstein SR. One prophage WO gene rescues cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:4987–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800650115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams KL, Abernathy DG, Willett BC, Selland EK. Wolbachia cifB induces cytoplasmic incompatibility in the malaria mosquito. 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.20.440637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun G, Zhang M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M. The Wolbachia CinB Nuclease is Sufficient for Induction of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. bioRxiv. 2021; 2021.10.22.465375. Available: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.22.465375v1%0Ahttps://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.22.465375v1.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang P, Wu W, Macfarlan TS. Maternal histone variants and their chaperones promote paternal genome activation and boost somatic cell reprogramming. BioEssays. 2015;37:52–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landmann F, Orsi GA, Loppin B, Sullivan W. Wolbachia-mediated cytoplasmic incompatibility is associated with impaired histone deposition in the male pronucleus. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lassy CW, Karr TL. Cytological analysis of fertilization and early embryonic development in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. Mech Dev. 1996;57:47–58. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00527-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serbus LR, Casper-Lindley C, Landmann F, Sullivan W. The genetics and cell biology of Wolbachia-host interactions. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:683–707. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tram U, Sullivan W. Role of delayed nuclear envelope breakdown and mitosis in Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. Science. 2002;296:1124–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1070536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tram U, Fredrick K, Werren JH, Sullivan W. Paternal chromosome segregation during the first mitotic division determines Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility phenotype. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3655–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callaini G, Riparbelli MG, Giordano R, Dallai R. Mitotic defects associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans. J Invertebr Pathol. 1996;67:55–64. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1996.0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callaini G, Dallai R, Riparbelli MG. Wolbachia-induced delay of paternal chromatin condensation does not prevent maternal chromosomes from entering anaphase in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 2):271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, et al. The Toxin–Antidote Model of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Genetics and Evolutionary Implications. Trends Genet. 2019:175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shropshire JD, Leigh B, Bordenstein SR, Duplouy A, Riegler M, Brownlie JC, et al. Models and Nomenclature for Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Caution over Premature Conclusions–A Response to Beckmann et al. Trends Genet. 2019:397–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horard B, Terretaz K, Gosselin-Grenet A-S, Sobry H, Sicard M, Landmann F, et al. Paternal transmission of the Wolbachia CidB toxin underlies cytoplasmic incompatibility. Curr Biol. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller M. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Spermatogenesis. 1993:71–147. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayaramaiah Raja S, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Replacement by Drosophila melanogaster Protamines and Mst77F of Histones during Chromatin Condensation in Late Spermatids and Role of Sesame in the Removal of These Proteins from the Male Pronucleus. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6165–77. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6165-6177.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabian L, Brill JA. Drosophila spermiogenesis. Spermatogenesis. 2012;2:197–212. doi: 10.4161/spmg.21798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eren-Ghiani Z, Rathke C, Theofel I, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Prtl99C Acts Together with Protamines and Safeguards Male Fertility in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonnefoy E, Orsi GA, Couble P, Loppin B. The essential role of Drosophila HIRA for de novo assembly of paternal chromatin at fertilization. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1991–2006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bressac C, Rousset F. The reproductive incompatibility system in Drosophila simulans: Dapi-staining analysis of the Wolbachia symbionts in sperm cysts. J Invertebr Pathol. 1993;61:226–30. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1993.1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark ME, Veneti Z, Bourtzis K, Karr TL. The distribution and proliferation of the intracellular bacteria Wolbachia during spermatogenesis in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2002;111:3–15. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11804774. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00594-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rathke C, Baarends WM, Jayaramaiah-Raja S, Bartkuhn M, Renkawitz R, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Transition from a nucleosome-based to a protamine-based chromatin configuration during spermiogenesis in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1689–700. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner AM, Nanni P, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic marking of sperm by post-translational modification of histones and protamines. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2014;7. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-7-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luense LJ, Donahue G, Lin-Shiao E, Rangel R, Weller AH, Bartolomei MS, et al. Gcn5-Mediated Histone Acetylation Governs Nucleosome Dynamics in Spermiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2019;51:745–758.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goudarzi A, Shiota H, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. Genome-scale acetylation-dependent histone eviction during spermatogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenic I, Sonnack V, Failing K, Bergmann M, Steger K. In vivo effects of histone-deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin-A on murine spermatogenesis. J Androl. 2004;25:811–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sonnack V, Failing K, Bergmann M, Steger K. Expression of hyperacetylated histone H4 during normal and impaired human spermatogenesis. Andrologia. 2002;34:384–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2002.00524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lolis D, Georgiou I, Syrrou M, Zikopoulos K, Konstantelli M, Messinis I. Chromomycin A3-staining as an indicator of protamine deficiency and fertilization. Int J Androl. 1996;19:23–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1996.tb00429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazerooni T, Asadi N, Jadid L, Kazerooni M, Ghanadi A, Ghaffarpasand F, et al. Evaluation of sperm’s chromatin quality with acridine orange test, chromomycin A3 and aniline blue staining in couples with unexplained recurrent abortion. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:591–6. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9361-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10171–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindsey ARI, Rice DW, Bordenstein SR, Brooks AW, Bordenstein SR, Newton ILG. Evolutionary Genetics of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility Genes cifA and cifB in Prophage WO of Wolbachia. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10:434–51. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shropshire JD, Kalra M, Bordenstein SR. Evolution-guided mutagenesis of the cytoplasmic incompatibility proteins: Identifying CifA’s complex functional repertoire and new essential regions in CifB. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008794. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Matsumura N, Takashima H, Miyamoto-Sato E, Tomita M, et al. Six classes of nuclear localization signals specific to different binding grooves of importinα. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:478–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807017200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferree PM, Frydman HM, Li JM, Cao J, Wieschaus E, Sullivan W. Wolbachia utilizes host microtubules and Dynein for anterior localization in the Drosophila oocyte. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marlow FL. Maternal Control of Development in Vertebrates. Colloq Ser Dev Biol. 2010;1:1–196. doi: 10.4199/c00023ed1v01y201012deb005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beckmann JF, Sharma GD, Mendez L, Chen H, Hochstrasser M. The Wolbachia cytoplasmic incompatibility enzyme CIDB targets nuclear import and protamine-histone exchange factors. Elife. 2019;8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braun RE. Packaging paternal chromosomes with protamine. Nat Genet. 2001;28:10–2. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sassone-Corsi P. Editorial: Never enough—On the multiplicity and uniqueness of transcriptional regulators in postmeiotic male germ cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1575–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.5.8874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaucher J, Reynoird N, Montellier E, Boussouar F, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. From meiosis to postmeiotic events: The secrets of histone disappearance. FEBS J. 2010;277:599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rathke C, Baarends WM, Awe S, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Chromatin dynamics during spermiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:155–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schagdarsurengin U, Paradowska A, Steger K. Analysing the sperm epigenome: Roles in early embryogenesis and assisted reproduction. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:609–19. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carrell DT, Hammoud SS. The human sperm epigenome and its potential role in embryonic development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;16:37–47. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaneshiro KR, Rechtsteiner A, Strome S. Sperm-inherited H3K27me3 impacts offspring transcription and development in C. elegans. Nat Commun. 2019;10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07709-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levine MT, Vander Wende HM, Malik HS. Mitotic fidelity requires transgenerational action of a testis-restricted HP1. Elife. 2015;4:1–20. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hundertmark T, Gärtner SMK, Rathke C, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Nejire/dCBP-mediated histone H3 acetylation during spermatogenesis is essential for male fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2018;13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aoki VW, Emery BR, Liu L, Carrell DT. Protamine levels vary between individual sperm cells of infertile human males and correlate with viability and DNA integrity. J Androl. 2006;27:890–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cho C, Jung-Ha H, Willis WD, Goulding EH, Stein P, Xu Z, et al. Protamine 2 deficiency leads to sperm DNA damage and embryo death in mice. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:211–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.015115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loppin B, Lepetit D, Dorus S, Couble P, Karr TL. Origin and neofunctionalization of a Drosophila paternal effect gene essential for zygote viability. Curr Biol. 2005;15:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark ME, Heath BD, Anderson CL, Karr TL. Induced paternal effects mimic cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila. Genetics. 2006;173:727–34. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Karr TL. Intracellular sperm/egg interactions in Drosophila: A three-dimensional structural analysis of a paternal product in the developing egg. Mech Dev. 1991;34:101–11. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90047-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans JP. The molecular basis of sperm-oocyte membrane interactions during mammalian fertilization. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:297–311. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.4.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flesch FM, Gadella BM. Dynamics of the mammalian sperm plasma membrane in the process of fertilization. Biochim Biophys Act. 2000;1469:197–235. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00018-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Degrugillier ME, Leopold RA. Ultrastructure of sperm penetration of house fly eggs. J Ultrasructure Res. 1976;56:312–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(76)90006-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xiao Y, Chen H, Wang H, Zhang M, Chen X, Berk JM, et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into the complexes formed by Wolbachia cytoplasmic incompatibility factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2107699118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107699118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McLay DW, Clarke HJ. Remodelling the paternal chromatin at fertilization in mammals. Reproduction. 2003;125:625–33. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang B, Ye W, Ye Y, Zhou H, Saeed AFUH, Chen J, et al. Structural insights into Cas13b-guided CRISPR RNA maturation and recognition. Cell Res. 2018;28:1198–201. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0109-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tirmarche S, Kimura S, Sapey-Triomphe L, Sullivan W, Landmann F, Loppin B. Drosophila protamine-like Mst35ba and Mst35bb are required for proper sperm nuclear morphology but are dispensable for male fertility. G3 (Bethesda). 2014;4:2241–5. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.012724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Casiraghi M, Bordenstein SR, Baldo L, Lo N, Beninati T, Wernegreen JJ, et al. Phylogeny of Wolbachia pipientis based on gltA, groEL and ftsZ gene sequences: clustering of arthropod and nematode symbionts in the F supergroup, and evidence for further diversity in the Wolbachia tree. 2006:4015–22. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28313-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Layton EM, On J, Perlmutter JI, Bordenstein SR, Shropshire JD. Paternal grandmother age affects the strength of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. mBio. 2019;10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01879-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shropshire JD, Hamant E, Cooper BS. Male Age and Wolbachia Dynamics: Investigating How Fast and Why Bacterial Densities and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility Strengths Vary. mBio. 2021;12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02998-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaur R, Martinez J, Rota-Stabelli O, Jiggins FM, Miller WJ. Age, tissue, genotype and virus infection regulate Wolbachia levels in Drosophila. Mol Ecol. 2020;29:2063–79. doi: 10.1111/mec.15462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Newton ILG, Savytskyy O, Sheehan KB. Wolbachia Utilize Host Actin for Efficient Maternal Transmission in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Western blots were run on protein extracted from ovaries (n = 10) of wild-type infected wMel+, uninfected wMel−, cifA transgenic (cifA), and dual cifA;B expressing transgenic lines. The expected size for CifA is approximately 54 kD. Western blots were run using anti-CifB antibody on testes (n = 15) of wild-type infected (+), uninfected (−), and cifA;B transgenic (A;B) lines. Expected CifB size is approximately 133kD. Cifs are absent in wMel− control and present at accurate size in wMel+ and cif expressing lines.

(TIF)

Testes (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males of wild-type wMel+ and wMel− lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) during sperm morphogenesis. DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. CifA and CifB localization patterns in wild-type lines are similar to that of transgenic cifAB (Fig 1) and signals are absent in wMel− uninfected control line. The experiment was conducted in parallel to the one shown in Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) ImageJ-based signal intensity quantification indicates CifA (green) is more abundantly expressed than CifB (red) in the spermatogonium stage of the spermatogenesis. Mean of individual data points with standard deviation is plotted on the graph. Letters indicate statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences as determined by pairwise comparisons based on a Mann–Whitney test. p-Values are reported in S1 Table. (B) In the decondensed mature sperms isolated from seminal vesicles, CifB is present in the acrosomal tip of canoe-shaped spermatids and mature sperm heads, whereas CifA is present in only 40% and 20% of them, respectively. Quantification was performed on the images obtained in Fig 1 data. Each dot represents percentage of Cifs present in spermatids or mature sperms per testes examined. Raw data underlying this figure can be found in S1 Data file.

(TIF)

Seminal vesicles (n = 20) from <8-hour-old males of transgenic cifAB, wild-type wMel+ and wMel− lines were dissected and immunostained to visualize CifA (green) and CifB (red) in the mature condensed sperms (indicated by white arrows). DAPI stain (blue) was used to label nuclei. Absence of both CifA and CifB indicates that proteins are not accessible to the antibodies when the sperm chromatin is condensed and tightly packed.

(TIF)