Abstract

Altogether, 100 strains of Listeria monocytogenes serovar 1/2a isolated from humans, animals, food, and the environment were typed by a combination of PCR and restriction enzyme analysis (REA). A PCR product of 2,916 bp, containing the downstream end of the gene inlA (955 bp), the space between inlA and inlB (85 bp), and 1,876 bp of the gene inlB, was cleaved with the enzyme AluI, and the fragments generated were separated by gel electrophoresis. By this method two different cleavage patterns were obtained. Seventy of the 100 strains shared one restriction profile, and the remaining 30 strains shared the second one. No relation was found between the types differentiated by PCR-REA and the origins of the strains.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive rod occasionally causing severe infections in humans and animals. Immunocompromised hosts are at particular risk for developing septicemia and/or meningitis, and infection in pregnant women may lead to infection in the fetus and thus to abortion, stillbirth, or the premature birth of a gravely ill child (20, 22). Ingestion of contaminated foods is considered to be the major cause of listeriosis (5).

Discriminant typing methods for the isolated bacteria are essential for linking a case of human listeriosis to a suspected food item. Serotyping and phage typing are established phenotypic methods. However, they have limitations. Phenotypic characteristics are determined not only by the genotype but also by environmental conditions (21). Serotyping is appropriate for the screening of large numbers of strains, for instance, during epidemics, but it lacks discriminatory power (18). Most strains belong to one of only three serovars, namely, 4b, 1/2a, or 1/2b (5, 15). Therefore, further typing is necessary. The reproducibility of serotyping is good for serovars 1/2a and 4b but poor for other serovars (1). Phage typing is labor-intensive and not always reproducible (10). Some L. monocytogenes strains are not phage typeable because they do not react strongly with any phage (10). Thus, there is a need for strictly genetic typing methods that are easy to perform.

The aim of this study was to investigate if a combination of PCR and restriction enzyme analysis (REA) could differentiate L. monocytogenes strains belonging to serovar 1/2a. A segment of 2,916 bp, containing the downstream end of the gene inlA (955 bp), the space between inlA and inlB (85 bp), and 1,876 bp of the gene inlB, was studied by using PCR and REA. A similar study on serovar 4b strains was done by Ericsson et al. (4). The genes inlA and inlB are two of the virulence genes of L. monocytogenes, and they are part of the same gene family (8, 12). Internalin, the gene product of inlA, is necessary for L. monocytogenes to enter cultured epithelial cells (6), and the gene product of InlB is necessary for L. monocytogenes to enter into hepatocytes in vitro (3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Altogether, 100 strains of L. monocytogenes serovar 1/2a isolated from humans (n = 36), animals (n = 33), foods (n = 21), and the environment (n = 10) during the period of 1977 through 1997 were studied. In addition two serovar 4b strains from humans were included. The human strains were isolated from patients with clinical listeriosis, and the animal strains came both from clinically ill animals and from asymptomatic carriers. The food strains were isolated from cheese (n = 12), salmon (n = 6), and meat products (n = 2) from the Swedish retail market and from unpasteurized milk delivered to a Swedish dairy plant (n = 1). The animal strains were from sheep (n = 10), cows (n = 9), fallow deer (n = 7), goats (n = 2), a chinchilla (n = 1), a cat (n = 1), a wild boar (n = 1), and a roe deer (n = 1) in Sweden and from a guinea pig (strain NCTC 7973/ATCC 19111). Environmental strains were isolated from litter (n = 3), fodder (n = 4), and silage (n = 3) on Swedish farms. The strains have previously been serotyped according to reference methods (19) and identified as belonging to serovar 1/2a.

PCR analysis.

The procedure described is based on the method of Ericsson et al. (4). One loopful of each strain, taken from freeze-stored bacterial cultures (−70°C in 80% brain heart infusion broth and 20% glycerol, vol/vol), was streaked onto horse blood agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. One well-isolated colony of each strain was inoculated into 25 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Difco) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, 15 μl of each culture was mixed with 140 μl of sterile water and denatured with 14 μl of 0.8 M NaOH in an Eppendorf tube. The tubes were heated to 70°C for 10 min and cooled on ice, and 18 μl of Tris (pH 8.0) and 12.5 μl of 0.8 M HCl were added. The pH of the suspension was checked and adjusted if it was not between 7 and 9. Five microliters (approximately 100,000 bacteria) of suspension was used for PCR.

The primers used were LIP 32 (5′ AACGACAACATTTAGTGGAACCGTGACG 3′, positions 2977 to 3004) and LIP 23 (5′ ATTAGCTGCTTTCGTCCAACCAATGAAAG 3′, positions 5893 to 5865). Sequence data used for construction of the primers were those previously published by Gaillard et al. (6). The PCR was performed essentially as described by Saiki et al. (16). The PCR mixture of 50 μl contained 30 mM Tricine, pH 8.4 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.); 2.0 mM MgCl2; 0.1% Thesit (Sigma); 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP; Boehringer Mannheim); 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer; and 1.0 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). PCR was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer thermocycler (P13480) run for 40 cycles (94°C for 1 min 15 s, 50°C for 1 min 15 s, and 72°C for 6 min), with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Four microliters of the reaction mixture was mixed with 2 μl of gel loading buffer, type IV (17), separated on a 2% agarose gel (SeaKem, LE; FMC) in 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA) at 8 V/cm for 30 min. The PCR product was visualized by ethidium bromide staining (1.5 μg/ml for 15 min) and photographed with a Polaroid MP-3 camera over a 312-nm transilluminator.

REA.

The restriction enzyme AluI (10 U/μl; Promega) was used as recommended by the manufacturer. Twenty microliters of the PCR product was incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a mixture of 20 U of AluI and 5 μl of Promega 10× buffer, with sterile water added for a volume of 50 μl. The mixture of cleaved DNA was placed on ice for 30 min to precipitate in 2.5 M ammonium acetate and 2.5 volumes of ethanol (99.5%, vol/vol). After centrifugation (20 min, 1,500 × g) the pellet was washed with 1.5 ml of ethanol (75%, vol/vol) and dried for 30 min at 70°C. The pellet was dissolved in 12 μl of 0.5× TBE, mixed with 2 μl of gel loading buffer, and separated on a 3% agarose gel (NuSieve GTG; FMC) in 0.5× TBE at 8 V/cm for 45 min. The gel was stained in ethidium bromide and photographed as previously described. The lanes on the gel were compared visually, and the strains were divided into different groups depending on the restriction profiles obtained. Culturing of strains, PCR, and REA were carried out a second time on all strains in order to ensure repeatability.

RESULTS

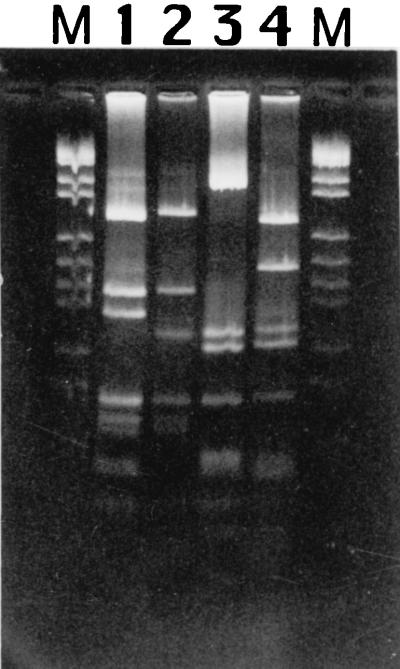

The 100 L. monocytogenes serovar 1/2a strains were divided into two groups (profiles 1/2a:I and 1/2a:II) by the PCR-REA method used. Seventy strains shared profile 1/2a:I and 30 shared profile 1/2a:II (Fig. 1; Table 1). Based on available data, we have not found any connections between PCR-REA type and strain origin. Of the 1/2a:I strains, 26 were isolated from humans, 20 were from animals (one strain was NCTC 7973/ATCC 19111), 18 were from food, and 6 were from environmental samples. Of the 1/2a:II strains, 10 were isolated from humans, 13 were from animals, 3 were from food, and 4 were from environmental samples.

FIG. 1.

PCR-REA profiles of L. monocytogenes serovars 1/2a and 4b produced by PCR amplification of the inlA and inlB regions followed by cleavage with AluI. Lanes M, pBR328 BglI plus pBR328 HinfI markers; lane 1, 1/2a:I (SLU 77); lane 2, 1/2a:II (SLU 83); lane 3, 4b:I (SLU 501); lane 4, 4b:II (SLU 592).

TABLE 1.

Serovar 1/2a strains divided into two groups by PCR-REA

| PCR-REA group | Strain origin | No. of strains in group |

|---|---|---|

| 1/2a:I | Human | 26 |

| Animal | 20 | |

| Food | 18 | |

| Environment | 6 | |

| Total | 70 | |

| 1/2a:II | Human | 10 |

| Animal | 13 | |

| Food | 3 | |

| Environment | 4 | |

| Total | 30 |

DISCUSSION

Characterization of L. monocytogenes strains is of utmost importance for the investigation of food-borne listeriosis. Outbreaks of human listeriosis are often caused by serovar 4b strains. Consequently, typing methods have been focused on and developed especially for strains belonging to this serovar. However, L. monocytogenes serogroup 1/2 strains seem to have become increasingly prevalent in human cases (7, 9, 11). Serogroup 1/2 strains are also often isolated during routine food examinations (15). Effective typing methods for 1/2 strains are therefore of increasing importance. By means of the genotypic method used in the present study, two different restriction profiles were obtained within a group of 100 1/2a strains. A similar PCR-REA study using the same gene segment was performed by Ericsson et al. on serovar 4b strains (4). They divided 133 strains of L. monocytogenes serovar 4b into two groups after cleavage with AluI. The two cleavage profiles obtained by Ericsson et al. are, however, clearly distinguishable from the two cleavage profiles obtained in the present study (Fig. 1). These two studies demonstrate that it is possible to subtype L. monocytogenes by PCR-REA, at least for strains belonging to serovars 1/2a and 4b. Only two cleavage patterns per serovar were obtained, indicating a low degree of polymorphism, at least in the region examined, based on the method used. Other studies have also shown a low degree of polymorphism in the virulence gene regions of the L. monocytogenes genome (14, 23, 24). Poyart et al. (13) used PCR to amplify two segments, one containing 1,157 bp and the other 760 bp, of the inlA gene in 68 strains of L. monocytogenes, mainly serovar 4b and 1/2a strains. After cleavage of the 1,157-bp fragment with AluI, five different profiles were obtained. The 760-bp fragment, internal to the inlA part of the PCR product of the present study, generated only one restriction pattern for all 68 strains. This result (13) may indicate that the differences in the PCR products observed in the present study and in the study of Ericsson et al. (4) are located in the inlB part. Comi et al. (2) studied a segment within the iap gene of 107 strains of L. monocytogenes by PCR and REA with the enzymes HindIII and RsaI. They obtained two groups of strains, one including strains of serovars 1/2a and 1/2c and another including strains of serovars 1/2b, 3b, and 4b. This is in close agreement with the results of Vines et al. (23), who, after PCR amplification of four virulence-associated genes of L. monocytogenes and analysis with several restriction endonucleases, divided 29 strains into two groups, one with strains of serovars 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a and the other with strains of serovars 1/2b, 3b, and 4b.

The present study and the study of Ericsson et al. (4) show that strains belonging to the same serovar may be divided into different groups based on differences in the inlA and inlB genes. In the future genetic differences might be used as a basis for a genotypic characterization method built on the established serovar nomenclature but having higher reproducibility than serotyping.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported financially by the Foundation of Michael Forsgren and by the Research Foundation of Ivar and Elsa Sandberg, to whom we express our gratitude.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bille J, Rocourt J. WHO international multicenter Listeria monocytogenes subtyping study—rationale and set-up of the study. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comi G, Cocolin L, Cantoni C, Manzano M. A RE-PCR method to distinguish Listeria monocytogenes serovars. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dramsi S, Biswas I, Maguin E, Braun L, Mastroeni P, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of InlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ericsson H, Stålhandske P, Danielsson-Tham M-L, Bannerman E, Bille J, Jacquet C, Rocourt J, Tham W. Division of Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4b strains into two groups by PCR and restriction enzyme analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3872–3874. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3872-3874.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerner-Smidt P, Weischer M, Jensen A, Frederiksen W. Proceedings of the XIIth International Symposium on Problems of Listeriosis. Canning Bridge, Australia: Promaco Conventions Pty Ltd.; 1995. Listeriosis in Denmark—results of a 10-year survey; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn M, Goebel W. Molecular studies on the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Genet Eng. 1995;17:31–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loncarevic S, Tham W, Danielsson-Tham M-L. Program and abstracts of the XIIIth International Symposium on Problems of Listeriosis. 1998. Changes in serogroup distribution among Listeria monocytogenes human isolates in Sweden; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLauchlin J, Audurier A, Frommelt A, Gerner-Smidt P, Jacquet C, Loessner M J, van der Mee-Marquet N, Rocourt J, Shah S, Wilhelms D. WHO study on subtyping Listeria monocytogenes: results of phage-typing. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLauchlin J, Newton L. Proceedings of the XIIth International Symposium on Problems of Listeriosis. Canning Bridge, Australia: Promaco Conventions Pty Ltd.; 1995. Human listeriosis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: a changing pattern of infection; pp. 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portnoy D A, Chakraborty T, Goebel W, Cossart P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1263–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1263-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Berche P. The inlA gene required for cell invasion is conserved and specific to Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiology (Great Britain) 1996;142:173–180. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen O F, Beck T, Olsen J E, Dons L, Rossen L. Listeria monocytogenes isolates can be classified into two major types according to the sequence of the listeriolysin gene. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3945–3951. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3945-3951.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocourt J. Foodborne listeriosis. Proceedings of a symposium on September 7, 1988, in Wiesbaden, FRG. Hamburg, Germany: Behr’s Verlag; 1988. Identification and typing of Listeria; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 6.12–6.13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schönberg A, Bannerman E, Courtieu A L, Kiss R, McLauchlin J, Shah S, Wilhelms D. Serotyping of 80 strains from the WHO multicentre international typing study of Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeliger H P R, Höhne K. Serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes and related species. Methods Microbiol. 1979;13:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeliger H P R, Jones D. Genus Listeria Pirie 1940, 383AL. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1235–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singleton P, Sainsbury D. Dictionary of microbiology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1978. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer J A D. Perinatal listeriosis. Br Med J. 1987;295:349. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6594.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vines A, Reeves M W, Hunter S, Swaminathan B. Restriction fragment length polymorphism in four virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vines A, Swaminathan B. Identification and characterization of nucleotide sequence differences in three virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes strains representing clinically important serotypes. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:309–318. doi: 10.1007/s002849900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]