Abstract

Problem/Condition

In 2019, approximately 67,000 persons died of violence-related injuries in the United States. This report summarizes data from CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) on violent deaths that occurred in 42 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in 2019. Results are reported by sex, age group, race and ethnicity, method of injury, type of location where the injury occurred, circumstances of injury, and other selected characteristics.

Period Covered

2019.

Description of System

NVDRS collects data regarding violent deaths obtained from death certificates, coroner and medical examiner records, and law enforcement reports. This report includes data collected for violent deaths that occurred in 2019. Data were collected from 39 states with statewide data (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming), three states with data from counties representing a subset of their population (30 California counties, representing 57% of its population, and 47 Illinois counties and 40 Pennsylvania counties, representing at least 80% of their populations), the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. NVDRS collates information for each violent death and links deaths that are related (e.g., multiple homicides, homicide followed by suicide, or multiple suicides) into a single incident.

Results

For 2019, NVDRS collected information on 50,374 fatal incidents involving 51,627 deaths that occurred in 42 states (39 states collecting statewide data, 30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties), and the District of Columbia. In addition, information was collected for 831 fatal incidents involving 897 deaths in Puerto Rico. Data for Puerto Rico were analyzed separately. Of the 51,627 deaths, the majority (64.1%) were suicides, followed by homicides (25.1%), deaths of undetermined intent (8.7%), legal intervention deaths (1.4%) (i.e., deaths caused by law enforcement and other persons with legal authority to use deadly force acting in the line of duty, excluding legal executions), and unintentional firearm deaths (<1.0%). The term “legal intervention” is a classification incorporated into the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and does not denote the lawfulness or legality of the circumstances surrounding a death caused by law enforcement. Demographic patterns and circumstances varied by manner of death. The suicide rate was higher for males than for females. Across all age groups, the suicide rate was highest among adults aged 45–54 years. In addition, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) and non-Hispanic White (White) persons had the highest suicide rates among all racial and ethnic groups. Among males, the most common method of injury for suicide was a firearm, whereas poisoning was the most common method of injury among females. Among all suicide victims, suicide was most often preceded by a mental health, intimate partner, or physical health problem or by a recent or impending crisis during the previous or upcoming 2 weeks. The homicide rate was higher for males than for females. Among all homicide victims, the homicide rate was highest among persons aged 20–24 years compared with other age groups. Non-Hispanic Black (Black) males experienced the highest homicide rate of any racial or ethnic group. Among all homicide victims, the most common method of injury was a firearm. When the relationship between a homicide victim and a suspect was known, the suspect was most frequently an acquaintance or friend for male victims and a current or former intimate partner for female victims. Homicide most often was precipitated by an argument or conflict, occurred in conjunction with another crime, or, for female victims, was related to intimate partner violence. Nearly all victims of legal intervention deaths were male, and the legal intervention death rate was highest among men aged 25–29 years. The legal intervention death rate was highest among AI/AN males, followed by Black males. A firearm was used in the majority of legal intervention deaths. When a specific type of crime was known to have precipitated a legal intervention death, the type of crime was most frequently assault or homicide. The three most frequent circumstances reported for legal intervention deaths were as follows: the victim’s death was precipitated by another crime, the victim used a weapon in the incident, and the victim had a mental health or substance use problem (other than alcohol use). Unintentional firearm deaths were most frequently experienced by males, White persons, and persons aged 15–24 years. These deaths most frequently occurred while the shooter was playing with a firearm and were precipitated by a person unintentionally pulling the trigger or mistakenly thinking the firearm was unloaded. The rate of deaths of undetermined intent was highest among males, particularly among Black and AI/AN males, and among adults aged 30–44 years. Poisoning was the most common method of injury in deaths of undetermined intent, and opioids were detected in nearly 80% of decedents tested for those substances.

Interpretation

This report provides a detailed summary of data from NVDRS on violent deaths that occurred in 2019. The suicide rate was highest among AI/AN and White males, whereas the homicide rate was highest among Black males. Mental health problems, intimate partner problems, interpersonal conflicts, and acute life stressors were primary circumstances for multiple types of violent death.

Public Health Action

Violence is preventable, and data can guide public health action. NVDRS data are used to monitor the occurrence of violence-related fatal injuries and assist public health authorities in developing, implementing, and evaluating programs, policies, and practices to reduce and prevent violent deaths. For example, the New Hampshire Violent Death Reporting System (VDRS), Indiana VDRS, and Colorado VDRS have used their VDRS data to guide suicide prevention efforts and generate reports highlighting where additional focus is needed. In New Hampshire, VDRS data have been used to monitor the increase in suicide rates during 2014–2018 and guide statewide collaborative prevention efforts. Indiana VDRS used local data to demonstrate differences in suicide and other related mental health problems among Black persons and highlight a need for improved suicide awareness and culturally competent mental health care. The Colorado VDRS conducted geospatial and demographic analysis, considering local VDRS data with existing suicide prevention efforts and resources, to identify regions with high suicide rates regions and populations at high risk for suicide. Similarly, states participating in NVDRS have used their VDRS data to examine related to homicide in their state. In North Carolina for example, where homicide rates among AI/AN and Black persons were approximately 2.5 times higher than the statewide homicide rate, the North Carolina VDRS program aims to partner with historically Black colleges and universities in the state to train researchers to use VDRS data to address health equity issues in and around their immediate community.

Introduction

According to National Vital Statistics System mortality data obtained from CDC’s Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS),* violence-related injuries led to 67,304 deaths in the United States in 2019 (1). Suicide was the 10th leading cause of death overall in the United States and disproportionately affected young and middle-aged populations. By age group, suicide was the second leading cause of death for persons aged 10–34 years and the fourth leading cause of death for adults aged 35–44 years. Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) and non-Hispanic White (White) males had the highest rates of suicide compared with all other racial and ethnic groups and females.

In 2019, homicide was the 16th leading cause of death overall in the United States but disproportionately affected young persons (1). Homicide was among the five leading causes of death for children aged 1–14 years, the third leading cause of death for persons aged 15–34 years, and the fifth leading cause of death for persons aged 35–44 years. Homicide was the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic Black (Black) males aged 15–34 years and the second leading cause of death for Black boys aged 1–14 years.

Public health authorities require accurate, timely, and complete surveillance data to better understand and ultimately prevent the occurrence of violent deaths in the United States (2,3). In 2000, in response to an Institute of Medicine† report noting the need for a national fatal intentional injury surveillance system (4), CDC began planning to implement the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) (2). The goals of NVDRS are to

collect and analyze timely, high-quality data for monitoring the magnitude and characteristics of violent deaths at national, state, and local levels;

ensure data are disseminated routinely and expeditiously to public health officials, law enforcement officials, policymakers, and the public;

ensure data are used to develop, implement, and evaluate programs and strategies that are intended to reduce and prevent violent deaths and injuries at national, state, and local levels; and

build and strengthen partnerships among organizations and communities at national, state, and local levels to ensure that data are collected and used to reduce and prevent violent deaths and injuries.

NVDRS is a state-based active surveillance system that collects data on the characteristics and circumstances associated with violence-related deaths in participating states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (2). Deaths collected by NVDRS include suicides, homicides, legal intervention deaths (i.e., deaths caused by law enforcement acting in the line of duty and other persons with legal authority to use deadly force, excluding legal executions), unintentional firearm deaths, and deaths of undetermined intent that might have been due to violence.§ The term “legal intervention” is a classification incorporated into the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (5) and does not denote the lawfulness or legality of the circumstances surrounding a death caused by law enforcement.

Before implementation of NVDRS, single data sources (i.e., death certificates) provided only limited information and few circumstances from which to understand patterns of violent deaths. NVDRS filled this surveillance gap by providing more detailed information. NVDRS is the first system to 1) provide detailed information on circumstances precipitating violent deaths, 2) link multiple source documents so that each incident can contribute to the study of patterns of violent deaths, and 3) link multiple deaths that are related to one another (e.g., multiple homicides, suicide pacts, or homicide followed by suicide of the suspect).

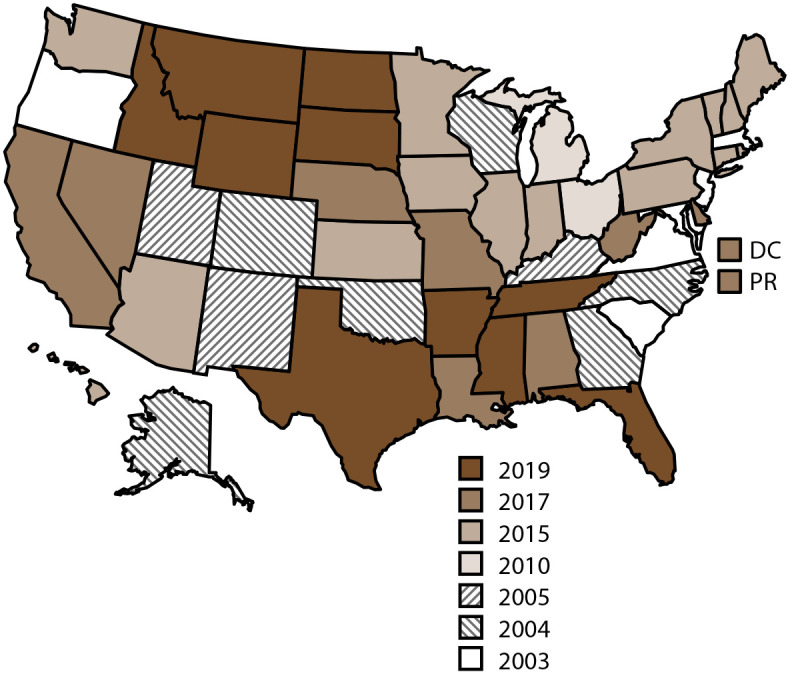

NVDRS data collection began in 2003 with six participating states (Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oregon, South Carolina, and Virginia) (Figure). Seven states (Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) began data collection in 2004, three (Kentucky, New Mexico, and Utah) in 2005, two (Ohio and Michigan) in 2010, and 14 (Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Washington) in 2015. In 2017, eight additional states began data collection (Alabama, California,¶ Delaware, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, and West Virginia), along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. NVDRS received funding in 2018 for a nationwide expansion that included the remaining 10 states (Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming), which began data collection in 2019. Since 2018, CDC has provided NVDRS funding to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. NVDRS data are updated annually and are available to the public through CDC’s WISQARS at https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nvdrs.html. Case-level NVDRS data are available to interested researchers who meet eligibility requirements via the NVDRS Restricted Access Database (https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/dataaccess.html).

FIGURE.

States participating in the National Violent Death Reporting System, by year of initial data collection* — United States and Puerto Rico, 2003–2019

Abbreviations: DC = District of Columbia; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System; PR = Puerto Rico.

* Map of United States indicates the year in which the state or territory began collecting data in NVDRS. California began collecting data for a subset of violent deaths in 2005 but ended data collection in 2009. In 2017, California collected data from death certificates for all NVDRS cases in the state; data for violent deaths that occurred in four counties (Los Angeles, Sacramento, Shasta, and Siskiyou) also include information from coroner or medical examiner reports and law enforcement reports. In 2018, California collected data from death certificates for all violent deaths in the state in 2018 (n = 6,641); data for violent deaths that occurred in 21 counties (Amador, Butte, Fresno, Humboldt, Imperial, Kern, Kings, Lake, Los Angeles, Marin, Mono, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, San Mateo, San Diego, San Francisco, Shasta, Siskiyou, Ventura, and Yolo) also included information from coroner or medical examiner reports and law enforcement (n = 3,658; 55.1%). In 2019, California collected data from death certificates for all violent deaths in the state in 2019 (n = 6,586); data for violent deaths that occurred in 30 counties (Amador, Butte, Colusa, Fresno, Glenn, Humboldt, Imperial, Kern, Kings, Lassen, Lake, Los Angeles, Marin, Modoc, Mono, Orange, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Shasta, Siskiyou, Solano, Sonoma, Tehama, Trinity, Ventura, and Yolo) also included information from coroner or medical examiner reports and law enforcement (n = 3,645; 55.3%). Michigan collected data for a subset of violent deaths during 2010–2013 and collected statewide data beginning in 2014. In 2016, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Washington began collecting data on violent deaths in a subset of counties that represented at least 80% of all violent deaths in their state or in counties where at least 1,800 violent deaths occurred. Illinois’s 2018 data are for violent deaths that occurred in 28 counties (Adams, Boone, Champaign, Cook, DuPage, Effingham, Fulton, Kane, Kankakee, Kendall, Lake, Lasalle, Livingston, Logan, Macoupin, McDonough, McHenry, McLean, Madison, Peoria, Perry, Rock Island, St. Clair, Sangamon, Tazewell, Vermillion, Will, and Winnebago). Pennsylvania’s 2018 data are for deaths that occurred in 39 counties (Adams, Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Berks, Blair, Bradford, Bucks, Cambria, Carbon, Centre, Chester, Clarion, Clearfield, Clinton, Columbia, Crawford, Dauphin, Delaware, Fayette, Forest, Greene, Indiana, Jefferson, Lackawanna, Lancaster, Lehigh, Luzerne, Monroe, Montgomery, Montour, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill, Union, Wayne, Westmoreland, Wyoming, and York). Illinois’s 2019 data are for violent deaths that occurred in 47 counties (Adams, Alexander, Bond, Boone, Brown, Bureau, Champaign, Clay, Cook, DeKalb, Douglas, DuPage, Effingham, Fayette, Fulton, Grundy, Henry, Iroquois, Jackson, Jefferson, Kane, Kankakee, Kendall, Lake, Lasalle, Livingston, Logan, Macoupin, McDonough, McHenry, McLean, Madison, Menard, Peoria, Perry, Piatt, Putnam, Rock Island, St. Clair, Sangamon, Schuyler, Stark, Tazewell, Vermilion, Wayne, Will, and Winn). Pennsylvania’s 2019 data are for violent deaths that occurred in 40 counties (Adams, Allegheny, Armstrong, Berks, Blair, Bradford, Bucks, Cameron, Cambria, Carbon, Centre, Chester, Clarion, Clearfield, Clinton, Crawford, Dauphin, Delaware, Erie, Fayette, Forest, Greene, Indiana, Jefferson, Lackawanna, Lancaster, Lehigh, Luzerne, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill, Somerset, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Union, Westmoreland, Wyoming, and York). In 2018, Washington began collecting statewide data for all deaths that occurred in the state in 2018. Beginning in 2019, all 50 U.S. states, DC, and Puerto Rico were participating in the system.

This report summarizes NVDRS data on violent deaths that occurred in 42 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in 2019. Thirty-nine states collected statewide data (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming), and the three remaining states collected data from a subset of counties in their states (30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties). This report of 2019 data includes data for three additional states that met inclusion criteria (Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming) that were not included in 2018. Data for Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas were ineligible to be included in this report because they were in an optional pilot year for data collection year 2019 and their approved and funded data collection plan represented <50% of all violent deaths in their state, or their data were ineligible to be included in this report because the data did not meet the completeness threshold for circumstances (see Inclusion Criteria).

Methods

NVDRS compiles information from three required data sources: death certificates, coroner and medical examiner records, and law enforcement reports (2). Some participating Violent Death Reporting System (VDRS) programs might also collect information from secondary data sources (e.g., child fatality review team data, Federal Bureau of Investigation Supplementary Homicide Reports, and crime laboratory data). NVDRS combines information for each death and links deaths that are related (e.g., multiple homicides, homicide followed by suicide, or multiple suicides) into a single incident. The ability to analyze linked data can provide a more comprehensive understanding of violent deaths. Participating VDRS programs use vital statistics death certificate files or coroner or medical examiner records to identify violent deaths meeting the NVDRS case definition (see Manner of Death). Each VDRS program reports violent deaths of residents that occurred within the state, district, or territory (i.e., resident deaths) and those of nonresidents for whom a fatal injury occurred within the state, district, or territory (i.e., occurrent deaths). When a violent death is identified, NVDRS data abstractors link source documents, link deaths within each incident, code data elements, and write brief narratives of the incident.

In NVDRS, a violent death is defined as a death resulting from the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or a group or community (2). NVDRS collects information on five manners of death: 1) suicide, 2) homicide, 3) legal intervention death, 4) unintentional firearm death, and 5) death of undetermined intent that might have been due to violence (see Manner of Death). NVDRS cases are determined based on ICD-10 cause of death codes (5) or the manner of death assigned by a coroner, medical examiner, or law enforcement officer. Cases are included if they are assigned ICD-10 cause of death codes (Box 1) or a manner of death specified in at least one of the three primary data sources consistent with NVDRS case definitions.

BOX 1. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes used in the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2019.

| Manner of death | Death ≤1 year after injury | Death >1 year after injury | Death any time after injury |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intentional self-harm (suicide) |

X60–X84 |

Y87.0 |

U03 (attributable to terrorism) |

| Assault (homicide) |

X85–X99, Y00–Y09 |

Y87.1 |

U01, U02 (attributable to terrorism) |

| Event of undetermined intent |

Y10–Y34 |

Y87.2, Y89.9 |

Not applicable |

| Unintentional exposure to inanimate mechanical forces (firearms) |

W32–W34 |

Y86 |

Not applicable |

| Legal intervention (excluding executions, Y35.5) | Y35.0–Y35.4, Y35.6, Y35.7 | Y89.0 | Not applicable |

NVDRS is an incident-based system, and all decedents associated with a given incident are grouped in one record. Decisions about whether two or more deaths are related and belong to the same incident are made based on the timing of the injuries rather than on the timing of the deaths. Deaths resulting from injuries that are clearly linked by source documents and occur within 24 hours of one other (see Manner of Death) are considered part of the same incident. Examples of an incident include 1) a single isolated violent death, 2) two or more related homicides (including legal intervention deaths) in which the fatal injuries were inflicted <24 hours apart, 3) two or more related suicides or deaths of undetermined intent in which the fatal injuries were inflicted <24 hours apart, and 4) a homicide followed by a suicide in which both fatal injuries were inflicted <24 hours apart (6).

Information collected from each data source is entered into the NVDRS web-based system (2). This system streamlines data abstraction by allowing abstractors to enter data from multiple sources into the same incident record. Internal validation checks, hover-over features that define selected fields, and other quality control measures are also included within the system. Primacy rules and hierarchal algorithms related to the source documents occur at the local VDRS program level. CDC provides access to the web-based system to each VDRS program. VDRS program personnel are provided ongoing coding training to learn and adhere to CDC guidance regarding the coding of all variables and technical assistance to help increase data quality. Data are transmitted continuously via the web to a CDC-based server. Information abstracted into the system is deidentified at the local VDRS program level.

Manner of Death

A manner (i.e., intent) of death for each decedent is assigned by a trained abstractor who integrates information from all source documents. The abstractor-assigned manner of death must be consistent with at least one required data source; typically, all source documents are consistent regarding the manner of death. When a discrepancy exists, the abstractor must assign a manner of death on the basis of a preponderance of evidence in the source documents; however, such occurrences are rare (6). For example, if two sources report a death as a suicide and a third reports it as a death of undetermined intent, the death is coded as a suicide.

NVDRS data are categorized into five abstractor-assigned manners of death: 1) suicide, 2) homicide, 3) legal intervention death, 4) unintentional firearm death, and 5) death of undetermined intent. The case definitions for each manner of death are described as follows:

Suicide. A suicide is a death among persons aged ≥10 years resulting from the use of force against oneself when a preponderance of evidence indicates that the use of force was intentional. This category also includes the following scenarios: 1) deaths of persons who intended only to injure rather than die by suicide; 2) persons who initially intended to die by suicide and changed their minds but still died as a result of the act; 3) deaths associated with risk-taking behavior without clear intent to inflict a fatal self-injury but associated with high risk for death (e.g., participating in Russian roulette); 4) suicides that occurred while under the influence of substances taken voluntarily; 5) suicides among decedents with mental health problems that affected their thinking, feelings, or mood (e.g., while experiencing an acute episode of a mental health condition, such as schizophrenia or other psychotic conditions, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder); and 6) suicides involving another person who provided passive (only) assistance to the decedent (e.g., supplying the means or information needed to complete the act). This category does not include deaths caused by chronic or acute substance use without the intent to die, deaths attributed to autoerotic behavior (e.g., self-strangulation during sexual activity), or assisted suicides (legal or nonlegal). Corresponding ICD-10 codes included in NVDRS are X60–X84, Y87.0, and U03 (Box 1).

Homicide. A homicide is a death resulting from the use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against another person, group, or community when a preponderance of evidence indicates that the use of force was intentional. Two special scenarios that CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) regards as homicides are included in the NVDRS case definition: 1) arson with no specified intent to injure someone and 2) a stabbing with intent unspecified. This category also includes the following scenarios: 1) deaths when the suspect intended to only injure rather than kill the victim, 2) deaths resulting from a heart attack induced when the suspect used force or power against the victim, 3) deaths that occurred when a person killed an attacker in self-defense, 4) deaths resulting from a weapon that discharged unintentionally while being used to control or frighten the victim, 5) deaths attributed to child abuse without intent being specified, 6) deaths attributed to an intentional act of neglect by one person against another, 7) deaths of liveborn infants that resulted from a direct injury due to violence sustained before birth, and 8) deaths identified as a justifiable homicide when the person committing homicide was not a law enforcement officer. This category excludes vehicular homicide without intent to injure, unintentional poisoning deaths due to illicit or prescription drug overdose even when the person who provided drugs was charged with homicide, unintentional firearm deaths (a separate category in NVDRS), combat deaths or acts of war, deaths of unborn fetuses, and deaths of infants that resulted indirectly from violence sustained by the mother before birth (e.g., death from prematurity after premature labor brought on by violence). Corresponding ICD-10 codes included in NVDRS are X85–X99, Y00–Y09, Y87.1, and U01–U02 (Box 1).

Legal intervention. A death from legal intervention is a death in which a person is killed or died as a result of injuries inflicted by a law enforcement officer or another peace officer (i.e., a person with specified legal authority to use deadly force), including military police, while acting in the line of duty. The term “legal intervention” is a classification from ICD-10 (Y35.0) and does not denote the lawfulness or legality of the circumstances surrounding a death caused by law enforcement. Legal intervention deaths also include a small subset of cases in which force was applied without clear lethal intent (e.g., during restraint or when applying force with a typically nondeadly weapon, such as a Taser) or in which the death occurred while the person was fleeing capture. This category excludes legal executions. Corresponding ICD-10 codes included in NVDRS are Y35.0–Y35.4, Y35.6, Y35.7, and Y89.0 (Box 1).

Unintentional firearm. An unintentional firearm death is a death resulting from a penetrating injury or gunshot wound from a weapon that uses a powder charge to fire a projectile and for which a preponderance of evidence indicates that the shooting was not directed intentionally at the decedent. Examples include the following: 1) a person who received a self-inflicted wound while playing with a firearm; 2) a person who mistakenly believed a gun was unloaded and shot another person; 3) a child aged <6 years who shot himself or herself or another person; 4) a person who died as a result of a celebratory firing that was not intended to frighten, control, or harm anyone; 5) a person who unintentionally shot himself or herself when using a firearm to frighten, control, or harm another person; 6) a soldier who was shot during a field exercise but not in a combat situation; and 7) an infant who died after birth from an unintentional firearm injury that was sustained in utero. This category excludes injuries caused by unintentionally striking a person with the firearm (e.g., hitting a person on the head with the firearm rather than firing a projectile) and unintentional injuries from nonpowder guns (e.g., BB, pellet, or other compressed-air–powered or compressed-gas–powered guns). Corresponding ICD-10 codes included in NVDRS are W32–W34 and Y86 (Box 1).

Undetermined intent. A death of undetermined intent is a death resulting from the use of force or power against oneself or another person for which the evidence indicating one manner of death is no more compelling than evidence indicating another. This category includes coroner or medical examiner rulings in which records from data providers indicate that investigators did not find enough evidence to determine whether the injury was intentional (e.g., unclear whether a drug overdose was unintentional or a suicide). Corresponding ICD-10 codes included in NVDRS are Y10–Y34, Y87.2, and Y89.9 (Box 1).

Variables Analyzed

NVDRS collects up to approximately 600 unique variables for each death (Boxes 1, 2, and 3). The number of variables recorded for each incident depends on the content and completeness of the source documents. Variables in NVDRS include

BOX 2. Methods used to inflict injury — National Violent Death Reporting System, 2019.

Firearm: method that uses a powder charge to fire a projectile from the weapon (excludes BB gun, pellet gun, or compressed air or gas-powered gun)

Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (e.g., hanging by the neck, manual strangulation, or plastic bag over the head)

Poisoning (e.g., fatal ingestion of a street drug, pharmaceutical, carbon monoxide, gas, rat poison, or insecticide)

Sharp instrument (e.g., knife, razor, machete, or pointed instrument)

Blunt instrument (e.g., club, bat, rock, or brick)

Fall: being pushed or jumping

Motor vehicle (e.g., car, bus, motorcycle, or other transport vehicle)

Personal weapons (e.g., hands, fists, or feet)

Drowning: inhalation of liquid (e.g., in bathtub, lake, or other source of water or liquid)

Fire or burns: inhalation of smoke or the direct effects of fire or chemical burns

Intentional neglect: starvation, lack of adequate supervision, or withholding of health care

Other (single method): any method other than those already listed (e.g., electrocution, exposure to environment or weather, or explosives)

Unknown: method not reported or not known

BOX 3. Circumstances preceding fatal injury, by manner of death — National Violent Death Reporting System, 2019.

Suicide or Death of Undetermined Intent

Intimate partner problem: decedent was experiencing problems with a current or former intimate partner.

Suicide of family member or friend: decedent was distraught over, or reacting to, the recent suicide of a family member or friend.

Other death of family member or friend: decedent was distraught over, or reacting to, the recent non-suicide death of a family member or friend.

Physical health problem: decedent was experiencing physical health problems (e.g., a recent cancer diagnosis or chronic pain).

Job problem: decedent was either experiencing a problem at work or was having a problem with joblessness.

Recent criminal legal problem: decedent was facing criminal legal problems (e.g., recent or impending arrest or upcoming criminal court date).

Noncriminal legal problem: decedent was facing civil legal problems (e.g., a child custody or civil lawsuit).

Financial problem: decedent was experiencing financial problems (e.g., bankruptcy, overwhelming debt, or foreclosure of a home or business).

Eviction or loss of home: decedent was experiencing a recent or impending eviction or other loss of housing, or the threat of eviction or loss of housing.

School problem: decedent was experiencing a problem related to school (e.g., poor grades, bullying, social exclusion at school, or performance pressures).

Traumatic anniversary: the incident occurred on or near the anniversary of a traumatic event in the decedent’s life.

Exposure to disaster: decedent was exposed to a disaster (e.g., earthquake or bombing).

Left a suicide note: decedent left a note, email message, video, or other communication indicating intent to die by suicide.

Disclosed suicidal intent: decedent had recently expressed suicidal feelings to another person with time for that person to intervene.

Disclosed intent to whom: type of person (e.g., family member or current or former intimate partner) to whom the decedent recently disclosed suicidal thoughts or plans.

History of suicidal thoughts or plans: decedent had previously expressed suicidal thoughts or plans.

History of attempting suicide: decedent had previously attempted suicide before the fatal incident.

Homicide or Legal Intervention Death

Jealousy (lovers’ triangle): jealousy or distress over an intimate partner’s relationship or suspected relationship with another person.

Stalking: pattern of unwanted harassing or threatening tactics by either the decedent or suspect.

Prostitution: prostitution or related activity that includes prostitutes, pimps, clients, or others involved in such activity.

Drug involvement: drug dealing, drug trade, or illicit drug use that is suspected to have played a role in precipitating the incident.

Brawl: mutual physical fight involving three or more persons.

Mercy killing: decedent wished to die because of a terminal or hopeless disease or condition, and documentation indicates that the decedent wanted to be killed.

Victim was a bystander: decedent was not the intended target in the incident (e.g., pedestrian walking past a gang fight).

Victim was a police officer on duty: decedent was a law enforcement officer killed in the line of duty.

Victim was an intervener assisting a crime victim: decedent was attempting to assist a crime victim at the time of the incident (e.g., a child attempts to intervene and is killed while trying to assist a parent who is being assaulted).

Victim used a weapon: decedent used a weapon to attack or defend during the course of the incident.

Intimate partner violence related: incident is related to conflict between current or former intimate partners; includes the death of an intimate partner or nonintimate partner (e.g., child, parent, friend, or law enforcement officer) killed in an incident that originated in a conflict between intimate partners.

Hate crime: decedent was selected intentionally because of his or her actual or perceived gender, religion, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or disability.

Mentally ill suspect: suspect’s attack on decedent was believed to be the direct result of a mental health problem (e.g., schizophrenia or other psychotic condition, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder).

Drive-by shooting: suspect drove near the decedent and fired a weapon while driving.

Walk-by assault: decedent was killed by a targeted attack (e.g., ambush) where the suspect fled on foot.

Random violence: decedent was killed in a random act of violence (i.e., an act in which the suspect is not concerned with who is being harmed, just that someone is being harmed).

Gang related: incident resulted from gang activity or gang rivalry; not used if the decedent was a gang member and the death did not appear to result from gang activity.

Justifiable self-defense: decedent was killed by a law enforcement officer in the line of duty or by a civilian in legitimate self-defense or in defense of others.

Suspect Information

Suspected other substance use by suspect: suspected substance use by the suspect in the hours preceding the incident.

Suspected alcohol use by suspect: suspected alcohol use by the suspect in the hours preceding the incident.

Suspect had developmental disability: suspect had developmental disability at time of incident.

Mentally ill suspect: suspect’s attack on decedent was believed to be the direct result of a mental health problem (e.g., schizophrenia or other psychotic condition, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder).

Prior contact with law enforcement: suspect had contact with law enforcement in the past 12 months.

Suspect attempted suicide after incident: suspect attempted suicide (fatally or non-fatally) after the death of the victim.

-

Suspect recently released from an institution: suspect injured victim within a month of being released from or admitted to an institutional setting.

All Manners of Death (Except Unintentional Firearm)

Current depressed mood: decedent was perceived by self or others to be feeling depressed at the time of death.

Current diagnosed mental health problem: decedent was identified as having a mental health disorder or syndrome listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Version V (DSM-V), with the exception of alcohol and other substance dependence (these are captured in separate variables).

Type of mental health diagnosis: identifies the type of DSM-V diagnosis reported for the decedent.

Current mental health treatment: decedent was receiving mental health treatment as evidenced by a current prescription for a psychotropic medication, visit or visits to a mental health professional, or participation in a therapy group within the previous 2 months.

History of ever being treated for mental health problem: decedent was identified as having ever received mental health treatment.

Alcohol problem: decedent was perceived by self or others to have a problem with, or to be addicted to, alcohol.

Substance use problem (excludes alcohol): decedent was perceived by self or others to have a problem with, or be addicted to, a substance other than alcohol.

Other addiction: decedent was perceived by self or others to have an addiction other than to alcohol or other substance (e.g., gambling or sex).

Family relationship problem: decedent was experiencing problems with a family member, other than an intimate partner.

Other relationship problem (nonintimate): decedent was experiencing problems with a friend or associate (other than an intimate partner or family member).

History of child abuse or neglect: as a child, decedent had history of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse; physical (including medical or dental), emotional, or educational neglect; exposure to a violent environment, or inadequate supervision by a caretaker.

Caretaker abuse or neglect led to death: decedent was experiencing physical, sexual, or psychological abuse; physical (including medical or dental), emotional, or educational neglect; exposure to a violent environment; or inadequate supervision by a caretaker that led to death.

Perpetrator of interpersonal violence during previous month: decedent perpetrated interpersonal violence during the previous month.

Victim of interpersonal violence during previous month: decedent was the target of interpersonal violence during the past month.

Physical fight (two persons, not a brawl): a physical fight between two individuals that resulted in the death of the decedent, who was either involved in the fight, a bystander, or trying to stop the fight.

Argument or conflict: a specific argument or disagreement led to the victim’s death.

Precipitated by another crime: incident occurred as the result of another serious crime.

Nature of crime: the specific type of other crime that occurred during the incident (e.g., robbery or drug trafficking).

Crime in progress: another serious crime was in progress at the time of the incident.

Terrorist attack: decedent was injured in a terrorist attack, leading to death.

Crisis during previous or upcoming 2 weeks: current crisis or acute precipitating event or events that either occurred during the previous 2 weeks or was impending in the following 2 weeks (e.g., a trial for a criminal offense begins the following week) and appeared to have contributed to the death. Crises typically are associated with specific circumstance variables (e.g., job problem was a crisis, or a financial problem was a crisis).

Other crisis: a crisis related to a death but not captured by any of the standard circumstances.

Unintentional Firearm Death

Context of Injury

Hunting: death occurred any time after leaving home for a hunting trip and before returning home from a hunting trip.

Target shooting: shooter was aiming for a target and unintentionally hit the decedent; can be at a shooting range or an informal backyard setting (e.g., teenagers shooting at signposts on a fence).

Loading or unloading gun: gun discharged when the shooter was loading or unloading ammunition.

Cleaning gun: shooter pulled trigger or gun discharged while cleaning, repairing, assembling, or disassembling gun.

Showing gun to others: gun was being shown to another person when it discharged, or the trigger was pulled.

Playing with gun: shooter was playing with a gun when it discharged.

Celebratory firing: shooter fired gun in celebratory manner (e.g., firing into the air at midnight on New Year’s Eve).

Other context of injury: shooting occurred during some context other than those already described.

Mechanism of Injury

Unintentionally pulled trigger: shooter unintentionally pulled the trigger (e.g., while grabbing the gun or holding it too tightly).

Thought gun safety was engaged: shooter thought the safety was on and gun would not discharge.

Thought unloaded or magazine disengaged: shooter thought the gun was unloaded because the magazine was disengaged.

Thought gun was unloaded: shooter thought the gun was unloaded for other unspecified reason.

Bullet ricocheted: bullet ricocheted from its intended target and struck the decedent.

Gun fired due to defect or malfunction: gun had a defect or malfunctioned as determined by a trained firearm examiner.

Gun fired while holstering: gun was being replaced or removed from holster or clothing.

Gun was dropped: gun discharged when it was dropped.

Gun fired while operating safety or lock: shooter unintentionally fired the gun while operating the safety or lock.

Gun was mistaken for toy: gun was mistaken for a toy and was fired without the user understanding the danger.

Other mechanism of injury: shooting occurred as the result of a mechanism not already described.

manner of death (i.e., the intent to cause death [suicide, homicide, legal intervention, unintentional, and undetermined] of the person on whom a fatal injury was inflicted) (Box 1);

demographic information (e.g., age, sex, and race and ethnicity) of victims and suspects (if applicable);

method of injury (i.e., the mechanism used to inflict a fatal injury) (Box 2);

location, date, and time of injury and death;

toxicology findings (for decedents who were tested);

circumstances (i.e., the events that preceded and were identified by investigators as relevant and therefore might have contributed to the infliction of a fatal injury) (Box 3);

whether the decedent was a victim (i.e., a person who died as a result of a violence-related injury) or both a suspect and a victim (i.e., a person believed to have inflicted a fatal injury on a victim who then was fatally injured, such as the perpetrator of a homicide followed by suicide);

information about any known suspects (i.e., a person or persons believed to have inflicted a fatal injury on a victim);

incident (i.e., an occurrence in which one or more persons sustained a fatal injury that was linked to a common event or perpetrated by the same suspect or suspects during a 24-hour period); and

type of incident (i.e., a combination of the manner of death and the number of victims in an incident).

Circumstances Preceding Death

Circumstances preceding death are defined as the precipitating events that contributed to the infliction of a fatal injury (Box 3). Circumstances are reported based on the content of coroner or medical examiner and law enforcement investigative reports. Certain circumstances are coded to a specific manner of death (e.g., “history of suicidal thoughts or plans” is collected for suicides and deaths of undetermined intent); other circumstances are coded across all manners of death (e.g., “ever treated for mental health or substance use problem”). The data abstractor selects from a list of potential circumstances and is required to code all circumstances that are known to relate to each incident. If circumstances are unknown (e.g., a body found in the woods with no other details reported), the data abstractor does not endorse circumstances; these deaths are then excluded from the denominator for circumstance values. If either the coroner or medical examiner record or law enforcement report indicates the presence of a circumstance, then the abstractor endorses the circumstance. For example, if a law enforcement report indicates that a decedent had disclosed thoughts of suicide or an intent to die by suicide, then the circumstance variable “recent disclosure of suicidal thoughts or intent” is endorsed.

Data abstractors draft two incident narratives: one that summarizes the sequence of events of the incident from the perspective of the coroner or medical examiner record and one that summarizes the sequence of events of the incident from the perspective of the law enforcement report. In addition to briefly summarizing the incident (i.e., the “who, what, when, where, and why” of the incident), the narratives provide supporting information on circumstances that the data abstractor indicated and context for understanding the incident, record information and additional detail that cannot be captured elsewhere, and facilitate data quality control checks on the coding of key variables.

Coding Training and Quality Control

Ongoing coding support for data abstractors is provided by CDC through an electronic help desk, monthly conference calls, annual in-person or virtual meetings that include coding training for data abstractors, and regular conference calls with individual VDRS programs. In addition, all data abstractors are invited to participate in monthly coding workgroup calls. VDRS programs can conduct additional abstractor training workshops and activities at their own discretion, including through the use of NVDRS Data Abstractor eLearn Training Modules. An NVDRS coding manual (6) with CDC-issued standard guidance on coding criteria and examples for each data element is provided to each VDRS program. Software features that enhance coding reliability include automated validation rules and a hover-over feature containing variable-specific information.

Each year, VDRS programs are required to reabstract a subset of cases using multiple abstractors to identify inconsistencies. In addition, each VDRS program’s data quality plan is evaluated by CDC. Before the data are released each year, CDC conducts a quality control analysis that involves the review of multiple variables for data inconsistencies, with special focus on abstractor-assigned variables (e.g., method of injury and manner of death). If CDC finds inconsistencies, the VDRS program is notified and asked for a response or correction. VDRS programs must meet CDC standards for completeness of circumstance data to be included in the national data set. VDRS programs must have circumstance information abstracted from either the coroner or medical examiner record or the law enforcement report for at least 50% of cases. However, VDRS programs often far exceed this requirement. For 2019, a total of 85.7% of suicides, homicides, and legal intervention deaths in NVDRS had circumstance data from either the coroner or medical examiner record or the law enforcement report. In addition, core variables that represent demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and race and ethnicity) and manners of death were missing or unknown for <0.1% of cases. To ensure the final data set has no duplicate records, during the data closeout process, NVDRS first identifies any records within VDRS programs that match on a subset of 14 key variables and then asks VDRS programs to review these records to determine whether they are true duplicates. One record in any set of two or more records that are true duplicates is retained, and the others are deleted by the VDRS program. Next, NVDRS uses SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) to search for any instances of duplicates of a unique identification variable associated with each decedent record. As a third and final check for duplicates, the SAS data set is created with an index that only executes successfully if no duplicates of this identification variable are found.

Time Frame

VDRS programs are required to begin entering all deaths into the web-based system within 4 months from the date the violent death occurred. VDRS programs then have an additional 16 months from the end of the calendar year in which the violent death occurred to complete each incident record. For data collection year 2019 (original completion period through April 2021), VDRS programs were provided an additional 2.5 months (July 15, 2021) to complete incident records because of delays in data collection resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Although VDRS programs typically meet timeliness requirements, additional details about an incident occasionally arrive after a deadline has passed. New incidents also might be identified after the deadline (e.g., when a death certificate is revised, new evidence is obtained that changes a manner of death, or an ICD-10 misclassification is corrected to meet the NVDRS case definition). These additional data are incorporated into NVDRS when analysis files are updated in real time in the web-based system; 2.5 months after the 16-month data collection period for the 2019 data year, case counts increased by <0.1%.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for violent deaths in this report are as follows: 1) cases met the NVDRS case definition for violent death; 2) cases occurred in participating VDRS states, the District of Columbia, or Puerto Rico in 2019; and 3) at least 50% of cases for each included state, district, or territory had circumstance information collected from the coroner or medical examiner record or law enforcement report. Data for Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas were ineligible to be included in this report because these states were each in an optional pilot year for data collection year 2019 and their approved and funded data collection plan represented <50% of all violent deaths in their state, or their data were ineligible to be included in this report because the data did not meet the completeness threshold for circumstances. Data collected in 2019 for New York was ineligible to be included in this report because the data did not meet the completeness threshold for circumstances.

Of the participating VDRS programs, 39 states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) collected information on all violent deaths that occurred in their state in 2019. In addition, data were collected on all violent deaths that occurred in the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico in 2019. Two states, Illinois and Pennsylvania, joined NVDRS with plans to collect data on violent deaths in a subset of counties that represented at least 80% of all violent deaths in their state or in counties where at least 1,800 violent deaths occurred. In 2019, these states reported data on a subset of counties that represented at least 80% of violent deaths in their state. Data were collected for 47 counties in Illinois (Adams, Alexander, Bond, Boone, Brown, Bureau, Champaign, Clay, Cook, DeKalb, Douglas, DuPage, Effingham, Fayette, Fulton, Grundy, Henry, Iroquois, Jackson, Jefferson, Kane, Kankakee, Kendall, Lake, Lasalle, Livingston, Logan, McDonough, McHenry, McLean, Macoupin, Madison, Menard, Peoria, Perry, Piatt, Putnam, Rock Island, St. Clair, Sangamon, Schuyler, Stark, Tazewell, Vermilion, Wayne, Will, and Winn) that represented 90% of the state’s population (7). In Pennsylvania, data were collected for 40 counties (Adams, Allegheny, Armstrong, Berks, Blair, Bradford, Bucks, Cameron, Cambria, Carbon, Centre, Chester, Clarion, Clearfield, Clinton, Crawford, Dauphin, Delaware, Erie, Fayette, Forest, Greene, Indiana, Jefferson, Lackawanna, Lancaster, Lehigh, Luzerne, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill, Somerset, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Union, Westmoreland, Wyoming, and York) that represented 83% of the state’s population (7). California collected data from death certificates for all violent deaths in the state in 2019 (n = 6,586); data for violent deaths that occurred in 30 counties (Amador, Butte, Colusa, Fresno, Glenn, Humboldt, Imperial, Kern, Kings, Lassen, Lake, Los Angeles, Marin, Modoc, Mono, Orange, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Shasta, Siskiyou, Solano, Sonoma, Tehama, Trinity, Ventura, and Yolo) also included information from coroner or medical examiner records and law enforcement reports and are included throughout the rest of the report (n = 3,645; 55.3%). These 30 counties represented 57% of California’s population (7). Because <100% of violent deaths were reported, data from California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, are not representative of all violent deaths occurring in these three states.

Analyses

This report includes data for violent deaths that occurred in 42 states (39 states collecting statewide data, 30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties), the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in 2019. VDRS program-level data were received by CDC by the extended date of July 15, 2021. All data received by CDC as of July 15, 2021, were consolidated and analyzed. The numbers, percentages, and crude rates are presented in aggregate for all deaths by the abstractor-assigned manner of death. The suicide rate was calculated using denominators among populations aged ≥10 years. The rates for other manners of death used denominators among populations of all ages. The rates for cells with frequency <20 are not reported because of the instability of those rates. Denominators for the rates for the three states that did not collect statewide data (California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania) correspond to the populations of the counties from which data were collected. The rates could not be calculated for certain variables (e.g., circumstances) because denominators were unknown.

Bridged-race 2019 population estimates were used as denominators in the crude rate calculations for the 42 states (39 states collecting statewide data, 30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties) and District of Columbia (8). For compatible numerators for the rate calculations to be derived, records listing multiple races were recoded to a single race, when possible, using race-bridging methods described by NCHS (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm) (9). The rates specific to race and ethnicity are not available for Puerto Rico because the Census Bureau estimates for Puerto Rico do not include race or Hispanic or Latino (Hispanic) origin (10). Data for Puerto Rico were analyzed separately. Population estimates by sex and age were used as denominators in the crude rate calculations for Puerto Rico (11).

Results

Violent Deaths in 42 States and the District of Columbia

For 2019, a total of 42 NVDRS states (39 states collecting statewide data, 30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties) and the District of Columbia collected data on 50,374 incidents involving 51,627 deaths (Supplementary Table S1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/116311). Suicides (n = 33,109; 64.1%) accounted for the highest rate of violent death (16.9 per 100,000 population aged ≥10 years), followed by homicides (n = 12,980; 25.1%) (5.8 per 100,000 population). Deaths of undetermined intent (n = 4,504; 8.7%), legal intervention deaths (n = 699; 1.4%), and unintentional firearm deaths (n = 335; <1.0%) occurred at lower rates (2.0, 0.3, and 0.2 per 100,000 population, respectively). Data for deaths by manner that include statewide counts and the rates for California are available (Supplementary Table S2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/116311).

Suicides

Sex, Age Group, and Race and Ethnicity

For 2019, a total of 42 NVDRS states (39 states collecting statewide data, 30 California counties, 47 Illinois counties, and 40 Pennsylvania counties) and the District of Columbia collected data concerning 32,560 incidents involving 33,109 suicide deaths among persons aged ≥10 years (Supplementary Table S1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/116311). The overall suicide rate was 16.9 per 100,000 population aged ≥10 years (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Number, percentage,* and rate† of suicides among persons aged ≥10 years,§ by selected demographic characteristics of decedent,¶ method used, and location in which injury occurred — National Violent Death Reporting System, 42 states and the District of Columbia,** 2019.

| Characteristic | Male |

Female |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Rate | No. (%) | Rate | No. (%) | Rate | |

|

Age group (yrs)

| ||||||

| 10–14 |

245 (<1.0) |

3.4 |

133 (1.9) |

1.9 |

378 (1.1)

|

2.7

|

| 15–19 |

1,184 (4.6) |

16.3 |

362 (5.1) |

5.2 |

1,546 (4.7)

|

10.8

|

| 20–24 |

2,147 (8.3) |

28.5 |

450 (6.3) |

6.3 |

2,597 (7.8)

|

17.6

|

| 25–29 |

2,340 (9.0) |

28.9 |

520 (7.3) |

6.7 |

2,860 (8.6)

|

18.0

|

| 30–34 |

2,290 (8.8) |

30.0 |

535 (7.5) |

7.2 |

2,825 (8.5)

|

18.7

|

| 35–44 |

4,128 (15.9) |

29.4 |

1,205 (16.9) |

8.6 |

5,333 (16.1)

|

19.0

|

| 45–54 |

4,122 (15.9) |

30.1 |

1,514 (21.3) |

10.8 |

5,636 (17.0)

|

20.3

|

| 55–64 |

4,345 (16.7) |

30.8 |

1,357 (19.1) |

9.0 |

5,702 (17.2)

|

19.6

|

| 65–74 |

2,681 (10.3) |

26.6 |

655 (9.2) |

5.7 |

3,336 (10.1)

|

15.5

|

| 75–84 |

1,730 (6.7) |

36.8 |

275 (3.9) |

4.6 |

2,005 (6.1)

|

18.7

|

| ≥85 |

780 (3.0) |

49.3 |

107 (1.5) |

3.7 |

887 (2.7)

|

19.9

|

| Unknown |

2 (<1.0) |

—†† |

1 (<1.0) |

— |

4 (<1.0)

|

—

|

|

Race and ethnicity

| ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic |

20,932 (80.5) |

32.7 |

5,694 (80.0) |

8.6 |

26,626 (80.4)

|

20.5

|

| Black, non-Hispanic |

1,847 (7.1) |

15.5 |

474 (6.7) |

3.6 |

2,321 (7.0)

|

9.3

|

| American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic |

427 (1.6) |

45.6 |

148 (2.1) |

14.9 |

575 (1.7)

|

29.8

|

| Asian or Pacific Islander |

799 (3.1) |

13.9 |

294 (4.1) |

4.6 |

1,093 (3.3)

|

9.0

|

| Hispanic§§ |

1,905 (7.3) |

14.3 |

492 (6.9) |

3.8 |

2,397 (7.2)

|

9.1

|

| Other |

67 (<1.0) |

— |

9 (<1.0) |

— |

77 (<1.0)

|

—

|

| Unknown |

17 (<1.0) |

— |

3 (<1.0) |

— |

20 (<1.0)

|

—

|

|

Method

| ||||||

| Firearm |

14,355 (55.2) |

15.0 |

2,150 (30.2) |

2.2 |

16,505 (49.9)

|

8.4

|

| Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation |

7,612 (29.3) |

7.9 |

2,150 (30.2) |

2.2 |

9,763 (29.5)

|

5.0

|

| Poisoning |

1,982 (7.6) |

2.1 |

2,173 (30.5) |

2.2 |

4,155 (12.5)

|

2.1

|

| Fall |

589 (2.3) |

0.6 |

214 (3.0) |

0.2 |

803 (2.4)

|

0.4

|

| Sharp instrument |

553 (2.1) |

0.6 |

109 (1.5) |

0.1 |

662 (2.0)

|

0.3

|

| Motor vehicles (e.g., buses, motorcycles, or other transport vehicles) |

415 (1.6) |

0.4 |

114 (1.6) |

0.1 |

529 (1.6)

|

0.3

|

| Drowning |

205 (<h1.0) |

0.2 |

107 (1.5) |

0.1 |

312 (<1.0)

|

0.2

|

| Fire or burns |

94 (<1.0) |

0.1 |

33 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

127 (<1.0)

|

<0.1

|

| Blunt instrument |

36 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

15 (<1.0) |

— |

51 (<1.0)

|

<0.1

|

| Other (e.g., Taser, electrocution, or nail gun, intentional neglect, or personal weapons) |

46 (<1.0) |

— |

12 (<1.0) |

— |

58 (<1.0)

|

—

|

| Unknown |

107 (<1.0) |

— |

37 (<1.0) |

— |

144 (<1.0)

|

—

|

|

Location of injury

| ||||||

| House or apartment |

18,547 (71.4) |

19.4 |

5,582 (78.5) |

5.6 |

24,129 (72.9)

|

12.3

|

| Motor vehicle |

1,404 (5.4) |

1.5 |

281 (3.9) |

0.3 |

1,685 (5.1)

|

0.9

|

| Natural area |

1,250 (4.8) |

1.3 |

224 (3.1) |

0.2 |

1,475 (4.5)

|

0.8

|

| Street or highway |

724 (2.8) |

0.8 |

121 (1.7) |

0.1 |

845 (2.6)

|

0.4

|

| Hotel or motel |

553 (2.1) |

0.6 |

205 (2.9) |

0.2 |

758 (2.3)

|

0.4

|

| Parking lot, public garage, or public transport |

448 (1.7) |

0.5 |

87 (1.2) |

<0.1 |

535 (1.6)

|

0.3

|

| Park, playground, or sports or athletic area |

429 (1.7) |

0.5 |

60 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

489 (1.5)

|

0.3

|

| Jail or prison |

410 (1.6) |

0.4 |

35 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

445 (1.3)

|

0.2

|

| Railroad tracks |

223 (<1.0) |

0.2 |

51 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

274 (<1.0)

|

0.1

|

| Bridge |

194 (<1.0) |

0.2 |

66 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

260 (<1.0)

|

0.1

|

| Commercial or retail area |

216 (<1.0) |

0.2 |

28 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

244 (<1.0)

|

0.1

|

| Supervised residential facility |

109 (<1.0) |

0.1 |

52 (<1.0) |

<0.1 |

161 (<1.0)

|

<0.1

|

| Other location¶¶ |

922 (3.5) |

— |

155 (2.2) |

— |

1,077 (3.3)

|

—

|

| Unknown |

565 (2.2) |

— |

167 (2.3) |

— |

732 (2.2)

|

—

|

| Total | 25,994 (100) | 27.1 | 7,114 (100) | 7.1 | 33,109 (100) | 16.9 |

* Percentages might not total 100% due to rounding.

† Per 100,000 population.

§ Suicide is not reported for decedents aged <10 years, as per standard in the suicide prevention literature. Denominators for the suicide rates represent the total population aged ≥10 years.

¶ Sex was unknown for one decedent.

** Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Illinois and Pennsylvania collected data on ≥80% of violent deaths in their state, in accordance with requirements under which these states were funded. Data for Illinois are for violent deaths that occurred in 47 counties (Adams, Alexander, Bond, Boone, Brown, Bureau, Champaign, Clay, Cook, DeKalb, Douglas, DuPage, Effingham, Fayette, Fulton, Grundy, Henry, Iroquois, Jackson, Jefferson, Kane, Kankakee, Kendall, Lake, Lasalle, Livingston, Logan, McDonough, McHenry, McLean, Macoupin, Madison, Menard, Peoria, Perry, Piatt, Putnam, Rock Island, St. Clair, Sangamon, Schuyler, Stark, Tazewell, Vermilion, Wayne, Will, and Winn). Data for Pennsylvania are for violent deaths that occurred in 40 counties (Adams, Allegheny, Armstrong, Berks, Blair, Bradford, Bucks, Cameron, Cambria, Carbon, Centre, Chester, Clarion, Clearfield, Clinton, Crawford, Dauphin, Delaware, Erie, Fayette, Forest, Greene, Indiana, Jefferson, Lackawanna, Lancaster, Lehigh, Luzerne, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill, Somerset, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Union, Westmoreland, Wyoming, and York). Data for California are for violent deaths that occurred in 30 counties (Amador, Butte, Colusa, Fresno, Glenn, Humboldt, Imperial, Kern, Kings, Lassen, Lake, Los Angeles, Marin, Modoc, Mono, Orange, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Shasta, Siskiyou, Solano, Sonoma, Tehama, Trinity, Ventura, and Yolo). Denominators for the rates for these three states (Illinois, Pennsylvania, and California) represent only the populations of the counties from which the data were collected.

†† Rate is not reported when number of decedents is <20 or when characteristic response is “other” or “unknown.”

§§ Includes persons of any race.

¶¶ Other location includes (in descending order): hospital or medical facility; industrial or construction area; farm; preschool, school, college, or school bus; cemetery, graveyard, or other burial ground; office building; abandoned house, building, or warehouse; synagogue, church, or temple; bar or nightclub; and other unspecified location.

The overall suicide rate for males (27.1 per 100,000 population) was 3.8 times the rate for females (7.1 per 100,000 population) (Table 1). The suicide rate for males ranged from 1.8 to 13.3 times the rate for females across age groups and 3.0 to 4.3 times the rate for females across racial and ethnic groups. Adults aged 45–54 years (20.3 per 100,000 population), ≥85 years (19.9 per 100,000 population), 55–64 years (19.6 per 100,000 population), and 35–44 years (19.0 per 100,000 population) had the highest rates of suicide across age groups. White persons accounted for the majority (80.4%) of suicides; however, AI/AN persons had the highest rate of suicide (29.8 per 100,000 population) among all racial and ethnic groups.

Among male suicide decedents, nearly half (48.5%) were aged 35–64 years (Table 1). Men aged ≥85 years had the highest rate of suicide (49.3 per 100,000 population), followed by men aged 75–84 years (36.8 per 100,000 population) and 55–64 years (30.8 per 100,000 population). AI/AN males had the highest rate of suicide (45.6 per 100,000 population), followed by White males (32.7 per 100,000 population). The rate of suicide for AI/AN males was 3.3 times the rate for males with the lowest rate (i.e., non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander [A/PI]; 13.9 per 100,000 population). The suicide rate was 15.5 per 100,000 population for Black males and 14.3 per 100,000 population for Hispanic males.

Among females, women aged 35–64 years accounted for 57.3% of suicides (Table 1). Women aged 45–54 years had the highest rate of suicide (10.8 per 100,000 population). The suicide rate was highest among AI/AN females (14.9 per 100,000 population), followed by White (8.6 per 100,000 population), A/PI (4.6 per 100,000 population), Hispanic (3.8 per 100,000 population), and Black (3.6 per 100,000 population) females. The suicide rate for AI/AN females was 4.1 times the rate for females with the lowest rates (i.e., Black females).

Method and Location of Injury

A firearm was used in half (49.9%; 8.4 per 100,000 population) of suicides, followed by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (29.5%; 5.0 per 100,000 population) and poisoning (12.5%; 2.1 per 100,000 population) (Table 1). Among males, the most common method of injury was a firearm (55.2%), followed by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (29.3%). Among females, poisoning (30.5%) was the most common method of injury; hanging, strangulation, or suffocation and a firearm were used in equal proportions (30.2%). Among all suicide decedents, the most common location of suicide was a house or apartment (72.9%), followed by a motor vehicle (5.1%), a natural area (4.5%), a street or highway (2.6%), and a hotel or motel (2.3%).

Toxicology Results of Decedent

Toxicology tests for blood alcohol concentration (BAC) were conducted for 53.8% of suicide decedents (Table 2). Among those with positive results for alcohol (40.7%), 63.8% had a BAC ≥0.08 g/dL. Tests for the following substances were conducted for the percentage of decedents indicated in parentheses: amphetamines (43.3%), antidepressants (30.0%), benzodiazepines (42.4%), cannabis (more commonly referred to as marijuana; 38.5%), cocaine (42.7%), and opioids (45.1%). Positive results were found for 14.7% of decedents tested for amphetamines. Among those tested for antidepressants, 32.9% had positive results at the time of death, 21.5% of those tested for benzodiazepines had positive results, 25.0% of those tested for cannabis had positive results, and 6.1% of those tested for cocaine had positive results. Test results for opioids (including illicit and prescription opioids) were positive for 21.1% of decedents tested for these substances. Carbon monoxide was tested for a substantially smaller proportion of decedents (4.4%) but was identified in almost half of those decedents (41.1%).

TABLE 2. Number* and percentage of suicide decedents tested for alcohol and drugs whose results were positive,† by toxicology variable — National Violent Death Reporting System, 42 states and the District of Columbia,§ 2019.

| Toxicology variable | Tested |

Positive |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Blood alcohol concentration¶ |

17,804 (53.8) |

7,254 (40.7) |

| Alcohol <0.08 g/dL |

— |

1,962 (27.0) |

| Alcohol ≥0.08 g/dL |

— |

4,630 (63.8) |

| Alcohol positive, level unknown |

— |

662 (9.1) |

| Amphetamines |

14,331 (43.3) |

2,106 (14.7) |

| Anticonvulsants |

7,805 (23.6) |

1,289 (16.5) |

| Antidepressants |

9,942 (30.0) |

3,273 (32.9) |

| Antipsychotics |

7,521 (22.7) |

773 (10.3) |

| Barbiturates |

12,223 (36.9) |

254 (2.1) |

| Benzodiazepines |

14,032 (42.4) |

3,010 (21.5) |

| Carbon monoxide |

1,451 (4.4) |

596 (41.1) |

| Cocaine |

14,125 (42.7) |

857 (6.1) |

| Cannabis** |

12,760 (38.5) |

3,190 (25.0) |

| Muscle relaxants |

7,715 (23.3) |

455 (5.9) |

| Opioids |

14,928 (45.1) |

3,153 (21.1) |

| Other drugs or substances†† | 2,419 (7.3) | 2,294 (94.8) |

* Number of suicide decedents = 33,109.

† Percentage is of decedents tested for toxicology. Denominator for the percentage positive is the percentage tested.

§ Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Illinois and Pennsylvania collected data on ≥80% of violent deaths in their state, in accordance with requirements under which these states were funded. Data for Illinois are for violent deaths that occurred in 47 counties (Adams, Alexander, Bond, Boone, Brown, Bureau, Champaign, Clay, Cook, DeKalb, Douglas, DuPage, Effingham, Fayette, Fulton, Grundy, Henry, Iroquois, Jackson, Jefferson, Kane, Kankakee, Kendall, Lake, Lasalle, Livingston, Logan, McDonough, McHenry, McLean, Macoupin, Madison, Menard, Peoria, Perry, Piatt, Putnam, Rock Island, St. Clair, Sangamon, Schuyler, Stark, Tazewell, Vermilion, Wayne, Will, and Winn). Data for Pennsylvania are for violent deaths that occurred in 40 counties (Adams, Allegheny, Armstrong, Berks, Blair, Bradford, Bucks, Cameron, Cambria, Carbon, Centre, Chester, Clarion, Clearfield, Clinton, Crawford, Dauphin, Delaware, Erie, Fayette, Forest, Greene, Indiana, Jefferson, Lackawanna, Lancaster, Lehigh, Luzerne, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, Schuylkill, Somerset, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Union, Westmoreland, Wyoming, and York). Data for California are for violent deaths that occurred in 30 counties (Amador, Butte, Colusa, Fresno, Glenn, Humboldt, Imperial, Kern, Kings, Lassen, Lake, Los Angeles, Marin, Modoc, Mono, Orange, Placer, Sacramento, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Shasta, Siskiyou, Solano, Sonoma, Tehama, Trinity, Ventura, and Yolo).

¶ Blood alcohol concentration of ≥0.08 g/dL is greater than the legal limit in all states and the District of Columbia, and is used as the standard for intoxication.

** More commonly referred to as marijuana.

†† Other drugs or substances indicated whether any results were positive; levels for these drugs or substances are not measured.

Precipitating Circumstances

Circumstances were identified in 29,723 (89.8%) of suicides (Table 3). Overall, a mental health problem was the most common circumstance, with approximately half (48.3%) of decedents having had a current diagnosed mental health problem and 33.0% experiencing a depressed mood at the time of death. Among the 14,344 decedents with a current diagnosed mental health problem, depression or dysthymia (75.0%), anxiety disorder (22.3%), and bipolar disorder (14.9%) were the most common diagnoses. Among suicide decedents, 25.4% were receiving mental health treatment at the time of death. Alcohol use problems were reported for 19.2% of suicide decedents, and other substance use problems (unrelated to alcohol) were reported for 17.4% of suicide decedents (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Number* and percentage† of suicides among persons aged ≥10 years,§ by decedent’s sex and precipitating circumstances — National Violent Death Reporting System, 42 states and the District of Columbia,¶ 2019.

| Precipitating circumstance | Male |

Female |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

|

Mental health problem or substance use

| |||

| Current diagnosed mental health problem** |

10,180 (43.9) |

4,164 (63.6) |

14,344 (48.3)

|

| Depression or dysthymia |

7,519 (73.9) |

3,240 (77.8) |

10,759 (75.0)

|

| Anxiety disorder |

2,079 (20.4) |

1,124 (27.0) |

3,203 (22.3)

|

| Bipolar disorder |

1,348 (13.2) |

783 (18.8) |

2,131 (14.9)

|

| Posttraumatic stress disorder |

654 (6.4) |

197 (4.7) |

851 (5.9)

|

| Schizophrenia |

649 (6.4) |

200 (4.8) |

849 (5.9)

|

| Attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

333 (3.3) |

67 (1.6) |

400 (2.8)

|

| Dementia |

70 (<1.0) |

25 (<1.0) |

95 (<1.0)

|

| Obsessive compulsive disorder |

47 (<1.0) |

16 (<1.0) |

63 (<1.0)

|

| Autism spectrum |

37 (<1.0) |

5 (<1.0) |

42 (<1.0)

|

| Eating disorder |

6 (<1.0) |

25 (<1.0) |

31 (<1.0)

|

| Other |

594 (5.8) |

212 (5.1) |

806 (5.6)

|

| Unknown |

672 (6.6) |

255 (6.1) |

927 (6.5)

|

| History of ever being treated for a mental health problem |

6,966 (30.1) |

3,125 (47.7) |

10,091 (34.0)

|

| Current depressed mood |

7,625 (32.9) |

2,184 (33.3) |

9,809 (33.0)

|

| Current mental health treatment |

5,049 (21.8) |

2,488 (38.0) |

7,537 (25.4)

|

| Alcohol problem |

4,587 (19.8) |

1,113 (17.0) |

5,700 (19.2)

|

| Substance use problem (excludes alcohol) |

3,887 (16.8) |

1,283 (19.6) |

5,170 (17.4)

|

| Other addiction (e.g., gambling or sex) |

226 (<1.0) |

52 (<1.0) |

278 (<1.0)

|

|

Interpersonal factors

| |||

| Intimate partner problem |

6,271 (27.1) |

1,594 (24.3) |

7,865 (26.5)

|

| Family relationship problem |

1,775 (7.7) |

631 (9.6) |

2,406 (8.1)

|

| Other death of family member or friend |

1,331 (5.7) |

466 (7.1) |

1,797 (6.0)

|

| Suicide of family member or friend |

548 (2.4) |

191 (2.9) |

739 (2.5)

|

| Perpetrator of interpersonal violence during past month |

581 (2.5) |

57 (<1.0) |