Abstract

The gene encoding the type I pullulanase from the extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 was cloned and sequenced in Escherichia coli. The pulA gene from F. pennavorans Ven5 had 50.1% pairwise amino acid identity with pulA from the anaerobic hyperthermophile Thermotoga maritima and contained the four regions conserved among all amylolytic enzymes. The pullulanase gene (pulA) encodes a protein of 849 amino acids with a 28-residue signal peptide. The pulA gene was subcloned without its signal sequence and overexpressed in E. coli under the control of the trc promoter. This clone, E. coli FD748, produced two proteins (93 and 83 kDa) with pullulanase activity. A second start site, identified 118 amino acids downstream from the ATG start site, with a Shine-Dalgarno-like sequence (GGAGG) and TTG translation initiation codon was mutated to produce only the 93-kDa protein. The recombinant purified pullulanases (rPulAs) were optimally active at pH 6 and 80°C and had a half-life of 2 h at 80°C. The rPulAs hydrolyzed α-1,6 glycosidic linkages of pullulan, starch, amylopectin, glycogen, α-β-limited dextrin. Interestingly, amylose, which contains only α-1,4 glycosidic linkages, was not hydrolyzed by rPulAs. According to these results, the enzyme is classified as a debranching enzyme, pullulanase type I. The extraordinary high substrate specificity of rPulA together with its thermal stability makes this enzyme a good candidate for biotechnological applications in the starch-processing industry.

Pullulanase (pullulan-6-glucanohydrolase [EC 3.2.1.41]) is usually considered a debranching enzyme that specifically cleaves α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan, starch, amylopectin, and related oligosaccharides. However, over the last decade, a variety of pullulolytic enzymes with different substrate specificities have been characterized (35). Pullulan-degrading enzymes can be classified into four groups based on substrate specificities and reaction products: (i) pullulan hydrolase type I attacks α-1,4 glycosidic linkages in pullulan, forming panose (it was previously classified as a neopullulanase) (23); (ii) pullulan hydrolase type II attacks α-1,4 glycosidic linkages in pullulan, forming isopanose (it was previously classified as isopullulanase) (33); (iii) pullulanase type I specifically hydrolyzes α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan or branched oligosaccharides, forming maltotriose or linear oligomers, respectively; and (iv) pullulanase type II attacks α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan and branched substrates in addition to the α-1,4 glycosidic linkages in polysaccharides other than pullulan (18).

The enzymatic conversion of starch into glucose, maltose, and fructose for use as food sweeteners represents an important growth area in industrial enzyme usage. The most important industrial application of pullulanase is to the production of glucose or maltose syrups. This occurs when pullulanase is used in combination with glucoamylase or β-amylase, respectively, in the saccharification process. Thermostable pullulanases that are active between 60 and 100°C and that specifically attack the branching points of amylopectin (pullulanase type I) are of special interest, because they would allow more efficient and more rapid conversion reactions. The action of type I pullulanase results in the production of long polymers of α-1,4 linked glucose units, which are the ideal substrates for glucoamylase (9, 10). Hence, a number of pullulanases have been purified and characterized from different bacterial sources by many investigators. Most enzymes from thermophilic and hyperthermophilic microorganisms belong to pullulanase type II, whereas little information is available on thermostable pullulanases type I. To date, pullulanase type I has been characterized from moderately aerobic thermophilic bacteria Bacillus acidopullulyticus (15, 24), Bacillus flavocaldarius KP 1228 (36), Thermus aquaticus YT-1 (30), and Thermus caldophilus GK-24 (19) and the anaerobic bacterium Thermotoga maritima (4). Sequence information reveals a low level of overall conservation between type I enzymes. Recently, Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5, a newly isolated extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium, was shown to grow on starch and preferentially on branched oligomers, producing a heat-stable pullulanase (7). This pullulanase was purified and characterized from the culture supernatant, and it was demonstrated that the enzyme preferentially hydrolyzes α-1,6 glycosidic linkages. This unique thermoactive enzyme, which can be classified as a pullulanase type I according to its high substrate specificity, is active at temperatures between 60 and 85°C and has a potential application to the starch saccharification process (21). In this article we report on the cloning and sequencing of the pullulanase type I gene from F. pennavorans Ven5 and the biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

F. pennavorans Ven5 DSM 6204 was grown on starch anaerobically as previously described (21). E. coli PL2125 expressing the recombinant pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5 was grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (34) containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. E. coli FD748 containing the pullulanase cloned without the signal peptide was cultivated in LB medium or Terrific Broth (34) containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

Cloning of the pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from F. pennavorans Ven5 according to the method of Pitcher et al. (29), and 100 μg of DNA was partially digested with 20 U of Sau3A for 10 min. The digestion was terminated by a phenol-chloroform extraction, and the DNA was ethanol precipitated. A plasmid library was constructed in the vector pSJ933 (deposited in E. coli SJ989 under accession no. NCIMB 40320 [2a]) and the host strain E. coli MC100 by the usual methods (34). Red-dyed pullulan was made by suspending 50 g of pullulan (Hayashibara Biochemical Laboratories) and 5 g of Cibachron Rot B (Ciba Geigy) in 500 ml of 0.5 M NaOH and incubating the suspension at room temperature with constant stirring for 16 h. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 4 N H2SO4. The dyed pullulan was precipitated with constant stirring upon the addition of 600 ml of ethanol, harvested by centrifugation, and then resuspended in 500 ml of distilled water. This precipitation procedure was repeated three times, and the final dyed pullulan was resuspended in 500 ml of distilled water and autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. Red-dyed pullulan was added to a solid medium at a concentration of 1% (vol/vol) in order to detect, after clear halo formation, the clones containing and expressing the pullulanase gene. Halos are formed when the dye-pullulan complex is attacked by pullulanase, causing the release of the dye. E. coli transformants were plated on LB agar containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and after 16 h of incubation at 37°C approximately 14,000 colonies were observed. These were replica plated onto a new set of LB plates containing 2% agar, 6 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and 1% dyed pullulan and grown overnight at 37°C. The plates were then incubated at 60°C for 4 h, and the positive clone was identified as the one producing a halo in the agar, resulting from pullulan degradation. The isolated clone, PL2125, was grown in 10 ml of LB medium, and the plasmid was isolated with a kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany).

Subcloning and expression of open reading frame 1 (ORF1) encoding pullulanase.

PCR amplification was carried out by using the Expand long template PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim) with the following temperature profile: 94°C for 2 min and 30 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 45°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 4 min. The cloning of the PCR-amplified fragments was carried out by using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Pullulanase activity could be seen after overnight growth of the positive clones on LB medium containing red-dyed pullulan at 37°C and heat treated at 70°C for 16 h. The plasmid pSE420 containing the IPTG-inducible trc promoter (Invitrogen) was used for expression.

E. coli containing pulA cloned into pSE420 was inoculated from an overnight culture in LB medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml into Terrific Broth (34) containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and incubated with shaking at 37°C. The cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG upon reaching an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8. The cells were harvested after 18 h. The cell pellets were resuspended in a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.0 (5 ml/g [wet weight]), and sonicated for 15 min. Following centrifugation the pullulanase-containing supernatant was assayed for activity, and the protein concentration was determined as described below.

The mutation of the leucine codon TTG was carried out by PCR according to the method described by Nelson and Long (27). The primers were as follows: mutation primer, GTG GCT CTT ACA AGG AAT AG; nonsense, CGA TCG ATC GAG GAT CCT TA; reverse plus nonsense, CGA TCG ATC GAG GAT CCT TAT TAA TTA CCT TTG TAC ATT ACC; and forward, ATA AAC ATG TCG GAA ACA GAG CTG ATT ATC.

The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1, and the mutation was confirmed by sequencing. The fragment containing the mutation was digested with AflIII and BamHI and cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of pSE420. The mutation was once again confirmed by sequencing. The pullulanase-containing clones were detected on pullulan-red agar plates.

Enzyme assay.

Pullulanase activity was determined by measuring the amount of reducing sugars released during incubation with pullulan. To 50 μl of 1% (wt/vol) pullulan dissolved in a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0), 25 or 50 μl of the enzyme solution was added, and the samples were incubated at different temperatures for 10 to 60 min. The reaction was stopped by cooling the mixture on ice, and the amounts of reducing sugars released were determined by the dinitrosalicylic acid method (3). Sample blanks were used to correct for the nonenzymatic release of reducing sugars. One unit of pullulanase is defined as the amount of enzyme that releases 1 μmol of reducing sugars (with maltose as the standard) per min under the assay conditions specified. Pullulanase activity was routinely determined in a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) at 80°C with 0.5% (wt/vol) pullulan. The protein concentration was determined according to the method of Bradford (5).

Affinity column chromatography.

β-Cyclodextrin–Sepharose affinity matrix was prepared by coupling 40 μmol of β-cyclodextrin to 1 g of epoxy-activated Sepharose 6B according to the protocol described by Saha et al. (32) and following the instructions of the manufacturer (Affinity Chromatography, Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden).

Purification of the recombinant pullulanases.

All purification steps were performed at room temperature. E. coli cells (10 g) expressing pullulanase activity were washed with 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (buffer A) and then resuspended in 50 ml of the same buffer. Cells were disrupted by sonication, and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 30,000 × g. The supernatant was heat treated at 75°C for 60 min, and the denatured host proteins were pelleted by centrifugation (15 min at 30,000 × g). The pullulanase remained in the clear supernatant.

Purification of recombinant pullulanases from E. coli PL2125 and FD748. (i) Phenyl Sepharose chromatography.

The column (2.5 by 6 cm) was equilibrated with buffer A containing 1 M ammonium sulfate. The enzyme from the previous step was mixed with ammonium sulfate at a final concentration of 1 M and applied to the column at a flow rate of 20 ml/h. After being washed with 50 ml of an equilibration buffer, a linear reverse gradient of 1 to 0 M ammonium sulfate in 150 ml of buffer A was applied to the column. The column was then washed with buffer A until no absorbance at 280 nm was detectable. Pullulanase was eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 40% (vol/vol) dimethylsulfoxide in 150 ml of buffer A at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions containing high-level pullulanase activity were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8 (buffer B).

(ii) Anion-exchange chromatography.

The protein solution was then applied to a Mono Q HR 5/5 column (Pharmacia LKB, Freiburg, Germany) equilibrated with buffer B. The elution of pullulanase was carried out with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

Purification of the recombinant pullulanases from the mutated clone E. coli FD748m.

The pullulanase preparation after heat treatment was applied to a β-cyclodextrin-epoxy-activated Sepharose column (1 by 10 cm) equilibrated in a 50 mM Na acetate buffer, pH 6.0 (buffer C). The column was washed stepwise with 50 ml of buffer C and then with the same buffer containing 1 M NaCl until no absorbance at 280 nm was detectable. Pullulanase activity was eluted with 1% pullulan in buffer C containing 1 M NaCl. Active fractions were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration (cutoff, 10 kDa), and dialyzed against 1,000 volumes of buffer A. The protein solution was then applied to a Mono Q HR 5/5 column (Pharmacia LKB), which was equilibrated with buffer B, and the elution was carried out with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

Gel electrophoresis.

Native polyacrylamide gels containing a gradient of 5 to 27% polyacrylamide were prepared as described by Koch et al. (20). Gels were run at 300 V for 24 h at 4°C. High-molecular-weight marker proteins (Pharmacia Biotech) were used as standards. In order to examine the subunit composition of the pullulanase, protein samples were also analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–12% PAGE) as described by Laemmli (25) after the samples had been heated at 100°C for 5 min. Low-molecular-weight marker proteins (Pharmacia Biotech) were used as standards. Following native PAGE and SDS-PAGE the proteins were stained with Coomassie blue. Zymogram staining for pullulytic activity was performed according to the method of Furegon et al. (12).

Influence of pH and temperature.

For studies on the influence of the pH and temperature, experiments were carried out with the purified recombinant enzyme (75 U/mg). The influence of the pH on pullulanase activity was determined by using the protocol described above, except for the substitution of a 0.12 M universal buffer for the sodium acetate buffer, to obtain values from pH 3.5 to 10.0; all of the assays were performed at 80°C. To determine the influence of temperature on the enzymatic activity, samples were incubated at temperatures from 40 to 100°C for 10 min. For temperatures above 90°C, an oil bath was used. Thermostability was investigated after incubation of the samples at different temperatures and pH 6.0. In all cases, the incubations were carried out in closed Hungate tubes in order to prevent the boiling of the solutions. After various time intervals, samples were withdrawn and clarified by centrifugation, and the enzymatic activity was measured as described above.

Characterization of hydrolysis product.

The hydrolysis products arising from the action of pullulanase on various linear and branched polysaccharides were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an Aminex HPX-42A column (300 by 78 mm) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Double-distilled water was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min (21, 35). The purified pullulanase was incubated at 65°C with 0.5% (wt/vol) pullulan, starch, glycogen, amylopectin, maltodextrin, panose, and 0.2% (wt/vol) amylose.

Samples were withdrawn at different time intervals, and the reaction was stopped by incubation of the mixture on ice. In order to distinguish maltotriose (only α-1,4 bonds) from panose or isopanose (α-1,4 and α-1,6 bonds) the incubation was performed with α-glucosidase from yeast in a 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 37°C. This enzyme is capable of hydrolyzing α-1,4 but not α-1,6 linkages in short-chain oligosaccharides.

Effects of metal ions and other reagents on pullulanase activity.

The effects of various substances on pullulanase activity were examined after coincubation of the purified and extensively dialyzed enzyme (final concentration, 0.2 U/ml) with metal ions and other reagents in various concentrations at 80°C for 10 min. Samples were withdrawn, cooled on ice, and tested for pullulanase activity as described above.

NH2-terminal analysis and DNA sequencing.

The NH2-terminal sequence of the purified pullulanase was determined by automated Edman degradation on a pulsed-liquid sequencer (model 473A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) connected on-line to an HPLC apparatus for phenylthiohydantoin derivative identification, following the procedures suggested by the manufacturer.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by using Qiagen spin columns (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed by using an ABI automatic DNA sequencer with primer extensions in both directions.

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequence analysis was carried out with the Lasergene program for Windows (DNAStar Inc.). Multiple alignments were carried out with the CLUSTAL W algorithm (37). BLAST and FASTA algorithms were used to search the databases (2). Signal sequence prediction was carried out using the SIGNALP program for the UNIX (28).

Chemicals.

All chemicals were reagent grade and were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) unless otherwise stated. Chemicals for gel electrophoresis were from Serva (Heidelberg, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of and the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by pulA have been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF096862.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the 8.1-kb insert encoding pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5.

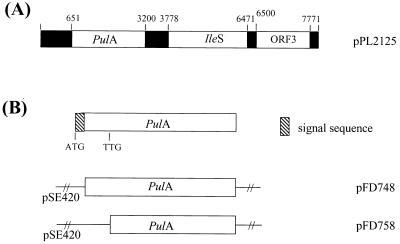

The E. coli clone PL2125 producing a thermostable pullulanase was obtained as described in Materials and Methods. The entire 8.1-kb insert was sequenced in both directions, and three large ORFs were identified (Fig. 1). ORF1 and ORF2 could be assigned functions on the basis of sequence homologies identified by the BLAST algorithm. The G+C content of the entire insert is 40.3%.

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction map of the 8.1-kb insert. The 3 ORFs and their positions are shown. (B) Subcloning of pulA to yield the clones pFD748 and pFD758.

We confirmed that ORF1 encodes a pullulanase by subcloning it into pUC18 and observing the activities of the E. coli transformants on red-dyed pullulan plates. This gene is referred to as pulA. pulA is 2,550 bp and encodes a protein of 849 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 96.6 kDa before processing. A Shine-Dalgarno-like sequence of AGGAGG is present at positions −10 to −15 in relation to the ATG site. The G+C content of pulA is 41.9%. A signal sequence of 28 amino acids is present with cleavage occurring between the amino acids Ala and Glu. This was predicted by using the method of Nielsen et al. (28) and confirmed by N-terminal sequencing of the mature pullulanase isolated from F. pennavorans Ven5 (ETELIIHYHRW).

ORF2 is 2,694 bp and encodes a protein of 897 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 103.5 kDa. The G+C content of ORF2 is 41.8%. The predicted amino acid sequence encoded by ORF2 has an overall identity of 68.3% with isoleucyl-tRNA synthase (encoded by ileS) of T. maritima. The construction of a phylogenetic tree based on isoleucyl-tRNA synthase sequences from Aquifex pyrophilus, T. maritima, Staphylococcus aureus, the human T lymphocyte, Tetrahymena thermophila, and Campylobacter jejuni placed ORF2 firmly in the T. maritima group (data not shown). This confirms that the insert containing pulA is from a bacterium belonging to the order Thermotogales that includes Fervidobacterium spp. and does not originate from contaminating DNA.

ORF3 is 1,272 bp and encodes a protein of 423 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 46.1 kDa. No significant homologies to database sequences were shown to exist by FASTA and BLAST searches.

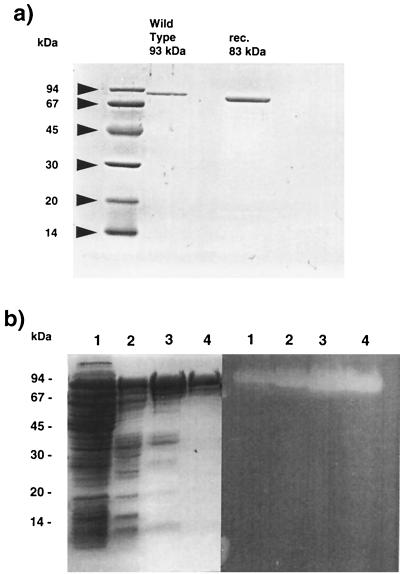

Purification of pullulanase from E. coli PL2125.

The specific activity of the purified pullulanase of F. pennavorans expressed in E. coli PL2125 was 0.43 U/mg. The denaturation of most of the proteins was achieved by treating the cell extract of the recombinant strain at 75°C for 60 min. After heat treatment, hydrophobic interaction, and anion-exchange chromatography, a specific pullulanase was purified 181-fold with a specific activity of 78 U/mg and a final yield of about 10% (Table 1). Proteins from the purification steps were separated by SDS–12% PAGE. The sample of the Mono Q pool revealed a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 83 kDa. Since the molecular mass of the native protein, calculated by native gradient gel electrophoresis, is 169 kDa the enzyme is a dimer composed of apparently identical subunits.

TABLE 1.

Purification of the recombinant pullulanases from E. coli clonesa

| E. coli clone and purification step | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U)b | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Fold purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL2125 | |||||

| Crude extract | 360 | 156 | 0.43 | 100 | |

| Heat treatment (1 h at 75°C) | 74 | 147 | 1.99 | 94 | 4.4 |

| Phenyl Sepharose | 1.65 | 59.6 | 36 | 38 | 84 |

| Mono Q | 0.19 | 14.8 | 78 | 9.4 | 181 |

| FD748m | |||||

| Crude extract | 747 | 2,268 | 3 | 100 | |

| Heat treatment (1 h at 75°C) | 172 | 2,184 | 12.7 | 96 | 4.2 |

| β-Cyclodextrin–Sepharose | 16.2 | 873.6 | 53.9 | 23 | 17.9 |

| Mono Q | 3.56 | 267 | 75 | 11.7 | 25 |

After the aerobic growth of E. coli at 37°C, a 5-liter culture was centrifuged (6 g of cells [wet weight]), and the cells were disrupted by sonication.

One unit of pullulanase catalyzes the formation of 1 μmol of reducing sugars per min under the defined conditions. Maltose was used as a standard.

Purification of the pullulanase from E. coli PL2125 yielded an enzyme whose molecular mass differs from the size of the wild-type enzyme from F. pennavorans Ven5, which is 93 kDa (see Fig. 2a). In fact, the N-terminal sequence (QGIEQIYTTKPDTSPRVL) of the pullulanase purified from E. coli was identified 118 amino acids downstream from the ATG start. A close examination of the DNA sequence at this position revealed a potential TTG translational start site complete with an ideally placed Shine-Dalgarno-like sequence (GGAGG). The translated DNA sequence at this point yields a smaller protein with 732 amino acids and a molecular mass of 83 kDa.

FIG. 2.

(a) SDS-PAGE of the purified pullulanases from F. pennavorans Ven5 and E. coli PL2125. Proteins were detected with Coomassie blue (0.1%). Arrows indicate molecular markers. (b) Gel electrophorectic analysis (left panel) and zymogram (right panel) of samples from various purification steps of the recombinant pullulanase from E. coli FD748m. On the left panel proteins were detected with Coomassie blue (0.1%). The right panel shows a zymogram as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1, crude extract (10 μg); lanes 2, crude extract after heat treatment (10 μg); lanes 3, affinity chromatography pool (4 μg); lanes 4, Mono Q pool (0.6 μg).

Overexpression of pulA in pSE420.

The pulA gene without the signal sequence was subcloned into the expression vector pSE420 under the control of the trc promoter, yielding the clone FD748. The pullulanase expression level of this clone was 40 times higher than that of E. coli PL2125. Two bands of 93 and 83 kDa were observed on an activity gel, showing that two active pullulanases were being produced in E. coli. Both proteins were purified, and N-terminal sequencing confirmed that two start sites, ATG and TTG, were used. The fragment of pulA, which starts at the second potential start site TTG, was cloned into pSE420 (Fig. 1B). The TTG was converted to ATG to optimize expression in E. coli FD758. This shorter pullulanase, which is missing 90 amino acids from the N-terminal end of the mature protein, displays activity, as determined by halo formation on red-dyed pullulan plates and measurement of reducing sugars produced from pullulan. This confirms that the first 90 amino acids following the signal cleavage are not necessary for catalytic activity or for a correct folding in E. coli.

Mutation of the second translational start site and physicochemical properties of the pullulanase purified from the mutated clone FD748m.

In order to express the pullulanase with a full size of 93 kDa the leucine-encoding TTG codon was replaced with TTA. This was necessary to eliminate the possibility of translation initiation at this point. Approximately 6 mg of pullulanase/liter of E. coli cells, as judged by SDS-PAGE and confirmed by determining the specific activity, was produced in shake flasks. The specific activity of the pullulanase of F. pennavorans Ven5 expressed in E. coli FD748m (rPulA) was 3 U/mg (Table 1). Also in this case a key purification step was the heat treatment of the cell extract at 75°C for 60 min. After affinity and anion-exchange chromatography a recombinant full-length pullulanase was purified 25-fold with a specific activity of 75 U/mg and a final yield of about 11.7% (Table 1). Proteins from the purification steps were separated by SDS–12% PAGE (Fig. 2b). After anion-exchange chromatography on Mono Q a single protein band was observed. The sample of the Mono Q pool revealed a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 93 kDa. The estimated molecular mass of the native rPulA, calculated by native gradient gel electrophoresis, is 190 kDa. Accordingly, the enzyme is a dimer which is composed of apparently identical subunits. As shown in Fig. 2b the samples from all purification steps showed one single pullulanolytic activity. This clearly demonstrates that the production of the 83-kDa pullulanase from E. coli PL2125 and E. coli FD748 was due to a false translation initiation at the second start site and not to protease cleavage.

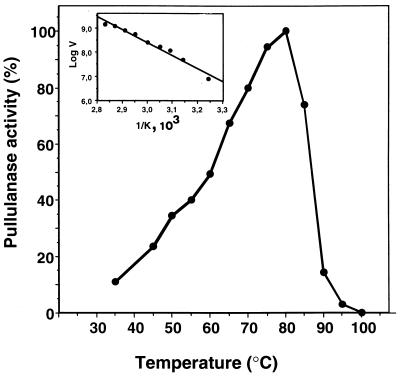

The recombinant full-length enzyme is active between 40 and 90°C. The temperature optimum of the purified enzyme is 80°C, and a rapid decrease in pullulanase activity was observed above this point (Fig. 3). An Arrhenius plot shows linearity between 40 and 90°C, being the activation energy of 20 kJ/mol (Fig. 3). The rPulA shows activity over a broad pH range with an optimum at pH 6.0. In order to evaluate the thermostability of the rPulA we measured the kinetics after prolonged and short-term incubations at high temperature in a range from 70 to 90°C. In the first case the enzyme decay obeys first-order kinetics. No loss of enzyme activity was observed after incubation of the purified rPulA at 75°C for 2 h. The half-life of the enzyme was 2 h at 80°C and 2 min at 87°C. The diagram of residual activity after 15 min of preincubation as a function of temperature led us to calculate an apparent melting temperature (Tm) of 84°C. The Km of the enzyme with pullulan as substrate is 0.4 mg/ml, and the Vmax is 1.58 U/mg.

FIG. 3.

Influence of temperature on the activity of the cloned pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5. For determination of the temperature optimum, the purified enzyme (0.03 mg/ml) was incubated in Na acetate buffer (pH 6.0), and incubation was performed for 10 min at various temperatures (35 to 100°C). (Inset) Arrhenius plot showing linearity between 35 and 80°C.

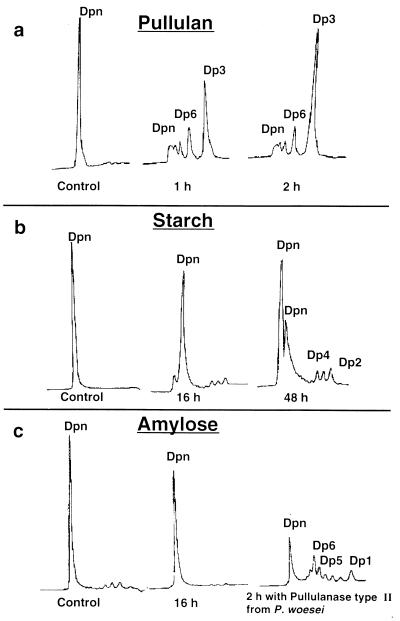

Substrate specificity and analysis of hydrolysis product.

The thermostable pullulanase hydrolyzed more than 98% of pullulan after 1 h of incubation at 80°C (Fig. 4a). The hydrolysis pattern after its action on pullulan revealed the complete conversion of pullulan to maltotriose in an endo-acting fashion. In order to confirm that the hydrolysis product from pullulan was maltotriose (possessing two α-1,4 glycosidic linkages) and not panose or isopanose (possessing α-1,4 and α-1,6 glycosidic linkages) the incubation of the products of pullulan hydrolysis was performed in the presence of α-glycosidase from yeast. The formation of glucose as the main product confirmed the formation of maltotriose (and not panose) from pullulan. No degradation of amylose was observed after 16 h of incubation at 65°C with the rPulA, demonstrating the low affinity of the purified pullulanase to α-1,4 glycosidic linkages. In contrast to this, the incubation of amylose with the purified recombinant pullulanase type II from Pyrococcus woesei (31) leads to the formation of oligosaccharides of a different degree of polymerization and glucose, thus indicating activity towards α-1,6 and α-1,4 glycosidic linkages (Fig. 4c). After 72 h of incubation with the purified rPulA, very low levels of maltose and maltotriose were detectable in the hydrolysis product of soluble starch (Fig. 4b), amylopectin, and glycogen. According to these results, the rPulA attacks specifically α-1,6 linkages of branched oligosaccharides and is classified as a type I pullulanase.

FIG. 4.

HPLC analysis of hydrolysis products formed after incubation of purified recombinant pullulanase in the presence of 0.5% pullulan (a), 0.5% starch (b), or 0.2% amylose (c). Samples were incubated at 80°C (a) or 65°C (b and c), and at different time intervals aliquots were withdrawn and analyzed on an Aminex HPX 42-A column for the oligosaccharides. The results of amylose hydrolysis by pullulanase type II from P. woesei is also shown (c). Dp, degree of polymerization (Dp1, glucose; Dp2, maltose; etc.).

Effects of metal ions and other reagents.

Divalent cations such as Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ inhibited the enzyme activity, while Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ had no effect. EDTA was also not inhibitory, suggesting that this chemical did not chelate a possible divalent cation(s) required for the activity of the thermostable rPulA. The lack of a Ca2+ binding site in the pullulanase primary structure also confirmed this experimental observation. In general, most of the reported pullulanases require Ca2+ ions for their full activity. The activity of the rPulA was inhibited by α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrins, which are known as possible competitive inhibitors of this enzyme (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Influences of different reagents on pullulanase activitya

| Reagent | Concentration | Pullulanase activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA | 5 mM | 100 |

| SDS | 1 mM | 0 |

| Triton X-100 | 0.1% | 100 |

| 1% | 100 | |

| Urea | 3 M | 64 |

| 6 M | 51 | |

| Guanidine HCl | 0.2 M | 81 |

| 0.6 M | 28 | |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 10 mM | 131 |

| 30 mM | 165 | |

| Dithiothreitol | 10 mM | 155 |

| Iodoacetamide | 10 mM | 62 |

| 20 mM | 59 | |

| MnCl2, MgCl2, CaCl2 | 5 mM | 100 |

| CuCl2 | 5 mM | 22 |

| NiCl2, FeSO4, ZnCl2 | 5 mM | 0 |

| N-Bromosuccinimide S | 0.01% | 10 |

| α-Cyclodextrin | 0.1% | 65 |

| β-Cyclodextrin | 0.1% | 36 |

| γ-Cyclodextrin | 0.1% | 45 |

Purified pullulanase was dialyzed against a 50 mM Na acetate buffer (pH 6.0). Samples (20 μg) were preincubated with the above reagents and ions at 60°C for 15 min (a 200-μl final volume). Aliquots (10 μl) were tested for pullulanase activity by incubating the samples with 0.5% pullulan in a 50 mM Na acetate buffer (pH 6.0) at 80°C for 10 min.

Sequence comparisons of pulA to other pullulanases.

On comparison with the sequence databases, the pulA product from F. pennavorans Ven5 had 50.1% pairwise amino acid identity with that from the anaerobic hyperthermophile T. maritima (4) (GenBank accession no. AJ001087). The sequence showing the next highest amino acid homology (35.5%) is the type I pullulanase from the gram-negative anaerobe Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (GenBank accession no. U67061) (11). Sequence pair distances among all of the type I pullulanases are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise similarity between the type I pullulanase amino acid sequencesa

| Pullulanase sequenceb from: | Similarity value (%) for pullulanase sequence from:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. pennavorans Ven5 | T. maritima | B. thetaiotaomicron | Thermus sp. | B. acidopullulyticus | C. saccharolyticus | K. aerogenes | K. pneumoniae | B. stearothermophilus | |

| Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 | 100 | 50.1 | 35.6 | 29.0 | 34.6 | 27.0 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 17.3 |

| Thermotoga maritima | 100 | 33.8 | 27.0 | 32.3 | 26.9 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 11.9 | |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | 100 | 31.4 | 38.6 | 27.7 | 18.4 | 16.9 | 18.3 | ||

| Thermus sp. | 100 | 27.5 | 23.9 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 18.9 | |||

| Bacillus acidopullulyticus | 100 | 26.5 | 19.0 | 15.6 | 16.9 | ||||

| Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus | 100 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.7 | |||||

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 100 | 91.0 | 92.0 | ||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 100 | 83.9 | |||||||

| Bacillus stearothermophilus | 100 | ||||||||

Calculated with CLUSTAL W and the PAM250 residue weight table.

The sequences are from the following sources: F. pennavorans Ven5 (this study), Thermotoga maritima (4) (GenBank accession no. AJ001087), B. thetaiotaomicron (11) (accession no. U67061), Thermus sp. (accession no. R71616; patent WPI 95-100945/14), B. acidopullulyticus (17), B. stearothermophilus (accession no. e03513; patent JP 1992099489-A [23]), C. saccharolyticus (1) (accession no. L39876), K. aerogenes (16) (accession no. M16187), and K. pneumoniae (22) (accession no. X52181).

Although there is little overall homology among all type I pullulanases, the four regions conserved among all amylolytic enzymes (26) could be found in the pullulanase of F. pennavorans Ven5 and are displayed in Table 4. Interestingly, a highly conserved region of seven amino acids, YNWGYDP, was detected about 40 amino acid residues to the N-terminal side of region I. This conserved region was found only in type I pullulanases that are derived from thermophilic and mesophilic bacteria (Table 4). The type II pullulanase sequences (with α-1,6 and α-1,4 activities) do not contain this conserved region.

TABLE 4.

Regions conserved among all type I pullulanases

| Source | Starting position and amino acid sequence for conserved regiona

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YNWGYDP | I | II | III | IV | |

| F. pennavorans Ven5 | 424 YNWGYDP | 465 GIRVILDMVFPHT | 538 DGFRFDQMGL | 570 YGEPWGG | 648 PQETINYVEVHDNHTLWD |

| T. maritima | 430 YNWGYDP | 473 FTGVIMDMVFPHT | 548 DGFRFDQMGL | 580 YGEPWGG | 638 PEETINYAACHDNHTLWD |

| B. thetaiotaomicron | 234 YNWGYDP | 275 GIRVIMDVVYNHT | 347 DGFRFDLMGI | 379 YGEGWAA | 670 PVQMISYVSCHDGLCLVD |

| Thermus sp. | 572 YNWGYNP | 333 GLRVVMDAVYNHV | 405 DGFRFDLMGV | 437 YGQGWDLb | 512 PRQSINYVECHDNHTFWD |

| B. acidopullulyticus | 436 YNWGYDP | 476 RIAINMDVVYNHT | 549 DGFRFDLMAL | 580 YGEPWTG | 656 PSETINYVTSHDNMTLWD |

| C. saccharolyticus | 405 YNWGYDP | 445 GIGVVMDVVFNHT | 520 DGFRFDLMGL | 552 YGEGWVM | 629 PDECVNYVSCHDNLTLFD |

| K. aerogenes | 574 YNWGYDP | 615 GMNVIMDVVYNHT | 691 DGFRFDLMGY | 723 FGEGWDS | 842 PTEVVNYVSKHDNQTLWD |

| K. pneumoniae | 562 YNWGYDP | 603 GMNVIMDVVYNHT | 679 DGFRFDLMGY | 711 FGEGWDS | 830 PTEVVNYVSKHDNQTLWD |

| B. stearothermophilus | 572 YNWGYNP | 613 GMNVIMDVVYNHT | 689 DGFRFDLMGY | 721 FGEGWDS | 456 PTEVVNYVSKHDNQTLWD |

DISCUSSION

The conversion of starch to glucose involves the addition of a heat-stable amylase, debranching enzymes, and glucoamylase. Due to the different conditions required by these enzymes, the pH and temperature are changed during the process. These variations in the process conditions are energy- and time-consuming. Finding enzymes that are active under the same conditions (the same pH and temperature) and that possess a high specificity towards the α-1,6 glycosidic linkages could dramatically improve the bioconversion of starch to glucose and fructose.

The extremely thermophilic bacterium F. pennavorans Ven5 was shown to produce a type I pullulanase which has properties that are ideal for application to the starch saccharification step (21). Due to the low enzyme yield of the thermophilic strains, its potential has not been thoroughly investigated yet. We succeeded in the cloning, sequencing, and expression of the recombinant thermostable pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5 in E. coli, thereby increasing expression levels to 0.5 mg of pure protein/g of cells.

Since there have been no pullulanase structures described yet, the identification of residues important for catalytic activity is based on the known amylase structures and is, therefore, tentative. Residues His607 and Asp677 in regions I and II of the pullulanase from Klebsiella aerogenes, suggested by Yamashita et al. (38) to be important for substrate binding, correspond to His476 and Asp543 of the F. pennavorans Ven5 pullulanase. His833 of K. aerogenes, which appears to be involved in catalytic activity towards α-1,6 linkages, corresponds to His658 of F. pennavorans Ven5. By the alignment of all the available pullulanase sequences we observed that the consensus sequence YNWGYDP is present in all enzymes characterized biochemically as type I pullulanases, with the exception of the alkaline amylopullulanase (type II) from Bacillus sp. strain KSM1378. This very large enzyme (210 kDa) is unusual in that it can be separated into two active enzymes by papain digestion, one having activity against only α-1,4 glycosidic bonds and the other against only α-1,6 bonds (14). The YNWGYDP motif is located in the enzyme half which can only hydrolyze α-1,6 bonds in pullulan. Since there is a strong selective pressure to retain this motif in enzymes which have little overall homology (for example, a 17% identity with the pullulanase from K. aerogenes) and this motif is present in all enzymes which can degrade only α-1,6 glycosidic bonds of pullulan, this region would appear to be involved in substrate binding or catalytic activity. This has been shown by the mutation of Tyr559 encoded by pulA in K. aerogenes, the second tyrosine (underlined) in the YNWGYDP motif (38), which resulted in a severe reduction of enzymatic activity but no alteration in substrate binding. The consensus sequence GYDXXXY, previously proposed for α-1,6 hydrolyzing enzymes (38), is not present in the type I pullulanases of T. maritima and F. pennavorans Ven5 or the debranching enzymes of rice and spinach, the second tyrosine XXY being replaced by Phe and Trp for each group, respectively. This tyrosine appears not to be conserved in all debranching enzymes.

The activity of the pullulanase produced under the control of the trc promoter was 122 times higher than that of the enzyme produced by the parent strain and 15 times higher than that of the shotgun clone. The recombinant pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5 was purified to homogeneity, allowing the characterization of the main structural and physicochemical properties. To date, only one gene encoding pullulanase from a Thermotogales strain has been cloned and expressed in E. coli (4), but only a preliminary enzyme characterization was carried out on the crude extract. The pullulanase from F. pennavorans Ven5 was purified from cellular extracts of E. coli and not from the supernatant. As observed for most thermophilic enzymes expressed in a mesophilic host, the production of thermoactive pullulanase was achieved at about 40°C below the optimum growth temperature of F. pennavorans Ven5, thus demonstrating that the high temperature is not necessary for the correct folding of the protein and that the enzyme does not require the presence of additional extrinsic factors to acquire its themophilia and thermostability. From SDS-PAGE experiments, the molecular mass of 93.5 kDa is very close to the values predicted for the pulA gene product. Values from 65 to 140 kDa per subunit have been reported for the enzymes derived from T. maritima, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, and B. acidopullulyticus (1, 4, 24). Unlike the dimeric enzyme from F. pennavorans Ven5, pullulanases described so far are monomeric (6, 8, 13, 14, 19, 30–32, 35, 36).

The second translational start site within pulA of F. pennavorans Ven5 is responsible for the production of the smaller pullulanase of 83 kDa in E. coli. It is interesting to note that the absence of the N-terminal 118 amino acids does not compromise the catalytic activity or substrate binding, so that the smaller pullulanase is identical to the wild-type enzyme with regard to temperature stability, temperature and pH optima, sensitivity to metal ions, and substrate specificity. This result is similar to that reported for the pullulanase of C. saccharolyticus (1), in which the removal of 127 amino acids from the N-terminal site did not appear to affect the thermostability or activity of the enzyme.

The pH optimum of 5.5 to 6.0 is very common for pullulan-hydrolyzing enzymes from various microorganisms, such as the archaea Thermococcus litoralis, Pyrococcus furiosus, P. woesei, and Thermococcus hydrothermalis, (6, 13, 31) and the bacteria Bacillus stearothermophilus, T. caldophilus GK-24, and T. maritima (4, 19, 23). Kim et al. (18) described a type I pullulanase from mesophilic alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain S-1, which exhibited an optimal activity at pH 8.0 to 10.0. The temperature optimum of the recombinant pullulanase is in the range of the optimal growth temperature of F. pennavorans Ven5 (75°C) and to the best of our knowledge represents, together with T. aquaticus YT-1 (31), the highest temperature optimum reported for a purified type I pullulanase. The purified pullulanase also shows a remarkable thermostability in this temperature range. In comparison to the commercially available pullulanase from B. acidopullulyticus (Promozyme; Novo Nordisk A/S) the recombinant enzyme from F. pennavorans Ven5 is more thermostable and active at acidic pH values, rendering it a potential candidate for industrial use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support from the Commission of European Communities (the Biotech Generic project Extremophiles as Cell Factories, contract BIO4CT975058) is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson G D, McHale R H, Gibbs M D, Bergquist P L. Cloning and sequence of a type I pullulanase from an extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1354:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Antranikian, G., P. L. Jørgensen, M. Wümpelmann, and S. T. Jørgensen. 20 February 1992. Novel thermostable pullulanases. Patent WO 92/02614.

- 3.Bernfeld P. Amylases α and β. Methods Enzymol. 1955;1:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibel M, Brettl C, Gosslar U, Kriegshäuser G, Liebl W. Isolation and analysis of genes for amylolytic enzymes of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;158:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown S H, Kelly R M. Characterization of amylolytic enzymes, having both α-1,4 and α-1,6 hydrolytic activity, from the thermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2614–2621. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2614-2621.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canganella F, Andrade C, Antranikian G. Characterisation of amylolytic and pullulytic enzymes from thermophilic archaea and from a new Fervidobacterium species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;42:239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung Y C, Kobayashi T, Kanai H, Akiba T, Kudo T. Purification and properties of extracellular amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus profundus DT5432. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1502–1506. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1502-1506.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan D. Industrial enzyme technology. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:177–178. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crabb W D, Mitchinson C. Enzymes involved in the processing of starch to sugars. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Elia J N, Salyers A A. Contribution of a neopullulanase, a pullulanase, and an α-glucosidase to growth of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron on starch. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7173–7179. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7173-7179.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furegon L, Curioni A, Peruffo D B A. Direct detection of pullulanase activity in electrophoretic polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1994;221:200–201. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gantelet H, Duchiron F. Purification and properties of a thermoactive and thermostable pullulanase from Thermococcus hydrothermalis, a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:770–777. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatada Y, Igarashi K, Ozaki K, Ara K, Hitomi J, Kobayashi T, Kawai S, Watabe T, Ito S. Amino acid sequence and molecular structure of an alkaline amylopullulanase from Bacillus that hydrolyses α-1,4 and α-1,6 linkages in polysaccharides at different active sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24075–24083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen B F, Norman B E. Bacillus acidopullulyticus pullulanase: application and regulatory aspects for use in the food industry. Process Biochem. 1984;19:351–369. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsuragi N, Takizawa N, Murooka Y. Entire nucleotide sequence of the pullulanase gene of Klebsiella aerogenes W70. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2301–2306. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2301-2306.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly A P, Diderichsen B, Jorgensen S, McConnell D J. Molecular genetic analysis of the pullulanase B gene of Bacillus acidopullulyticus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim C H, Choi H I, Lee D S. Pullulanase of alkaline and broad pH range from a newly isolated alkalophilic Bacillus sp. S-1 and Micrococcus sp. Y-1. J Ind Microbiol. 1993;12:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim C H, Nashiru O, Ko J H. Purification and biochemical characterization of pullulanase type I from Thermus caldophilus GK-24. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;138:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch R, Zablowski P, Spreinat A, Antranikian G. Extremely thermostable amylolytic enzyme from the archaeobacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch R, Canganella F, Hippe H, Jahnke K D, Antranikian G. Purification and properties of a thermostable pullulanase from a newly isolated thermophilic anaerobic bacterium, Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1088–1094. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1088-1094.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornacker M G, Pugsley A P. The normally periplasmic enzyme β-lactamase is specifically and efficiently translocated through the Escherichia coli outer membrane when it is fused to the cell surface enzyme pullulanase. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1101–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuriki T, Park J H, Imanaka T. Characteristics of thermostable pullulanases from Bacillus stearothermophilus and the nucleotide sequence of the gene. J Ferment Bioeng. 1989;69:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusano S, Nagahata N, Takahashi S, Fujimoto D, Sakano Y. Purification and properties of Bacillus acidopullulyticus pullulanase. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:2293–2298. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima R, Imanaka T, Aiba S. Comparison of amino acid sequences of eleven different α-amylases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;23:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson R M, Long G L. A general method of site-specific mutagenesis using a modification of the Thermus aquaticus polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem. 1989;180:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plant A R, Morgan H W, Daniel R M. A highly stable pullulanase from Thermus aquaticus YT-1. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1986;8:668–672. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rüdiger A, Jorgensen P L, Antranikian G. Isolation and characterization of a heat-stable pullulanase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus woesei after cloning and expression of its gene in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:567–575. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.567-575.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha B C, Mathupala S P, Zeikus G. Purification and characterization of a highly thermostable novel pullulanase from Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum. Biochem J. 1988;252:343–348. doi: 10.1042/bj2520343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakano Y, Higuchi M, Kobayashi T. Pullulan 4-glucan-hydrolase from Aspergillus niger. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1972;153:180–187. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spreinat A, Antranikian G. Purification and properties of a thermostable pullulanase from Clostridium thermosulfurogenes EM1 which hydrolyses both α-1,6 and α-1,4-glycosidic linkages. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;33:511–518. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki Y, Htagaki K, Oda H. A hyperthermostable pullulanase produced by an extreme thermophile, Bacillus flavocaldarius KP1228, and evidence for the proline theory of increasing thermostability. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;34:707–714. doi: 10.1007/BF00169338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamashita M, Matsumoto D, Murooka Y. Amino acid residues specific for the catalytic action towards α-1,6-glucosidic linkages in Klebsiella pullulanase. J Ferment Bioeng. 1997;84:283–290. [Google Scholar]