Abstract

Intensive tillage operations, indiscriminate use of irrigation water, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides and crop biomass burning have made the conventional rice–wheat (RW) system highly energy-intensive and inefficient. In the recent past, portfolios of climate-smart agricultural practices (CSAP) have been promoted as a potential alternative to improve the energy efficiency in conventional RW system. Therefore, to evaluate the energy input–output relation, energy flow and economic efficiency in various combinations of crop management options, a 3-year (2014–2017) on-farm study was conducted at Karnal, India. Various portfolio of management practices; Sc1-Business as usual (BAU) or Conventional tillage (CT) without residue, Sc2-CT with residue, Sc3-Reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF), Sc4-RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF, Sc5-ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer, Sc6-Sc5 + Nutrient expert were investigated. Present study results revealed that net energy, energy use efficiency and energy productivity were 11–18, 31–51 and 29–53% higher under CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) in RW system than Sc1, respectively. However, renewable and non-renewable energy inputs were 14 and 33% higher in Sc1 compared to CSAP (4028 and 49,547 MJ ha−1), respectively, it showed that BAU practices mostly dependents on non-renewable energy sources whereas CSAP dependents on renewable energy sources. Similarly, the adoption of CSAP improved the biomass yield, net farm income and economic efficiency by 6–9, 18–23 and 42–58%, respectively compared to Sc1. Overall, the adoption of CSAP could be a viable alternative for improving energy use efficiency, farm profitability and eco-efficiency in the RW system.

Subject terms: Climate sciences, Ecology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.)–wheat (Triticum aestivumL.) rotation in Indo-Gangetic Plains (IGP) of South Asia, with ~ 13.5 million hectares (Mha) acreage, is the backbone for food supply1–3. In India, the belt of rice–wheat (RW) rotation occupies almost 10.5 Mha areas and is the main source of food, nutrition and livelihood security in the country1,3. In RW system of the IGP, the energy is expensed in several forms such as labour, animal draft, farm machines, inorganic fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides and herbicides, electricity for pumping irrigation water, manual transplanting of rice seedlings into the well-puddled soils (puddled transplanted rice; PTR) etc. But presently, RW system are showing energy insecurity in the IGP`s region due to intensive energy used in various crop production activities such as multiple tillage (2–3 dry harrowing, 1–2 pass of rotavator/cultivators, 2–3 wet harrowing in rice and 1–2 planking) to get ready the field for rice and wheat planting2,4. Further, the use of more manual labour in transplanting of rice seedlings (30 days old age) into well-puddled soil also consumes an enormous amount of energy. In PTR, puddling alone needs approximately 25–30% of the total irrigation water requirement of rice2. Higher water requirement in rice is also due to more water losses in the form of puddling, percolation and surface evaporation which ultimately leads to more consumption of electricity for groundwater pumping for puddling (wet harrowing), nursery raising and frequent irrigation to keep the fields flooded throughout the growing season2,4. In upper and middle IGP, irrigation water is mostly driven by electricity pumps whereas in lower IGP diesel pumps are mainly used, and both consume a huge quantum of energy2. In recent years, higher fertilizer use, pumping of groundwater and depletion of groundwater resources along with higher pesticide consumption made RW system energy intensive which is the major threat to its future sustainability5. Approximately 84% of wheat production costs incurred from these energy-intensive inputs (e.g., irrigation, land preparation and fertilizers)6,7. In South Asia and elsewhere, published outcomes from diverse research findings have highlighted that intensive tillage practices accounts ~ 25% or more of the total production cost in RW system1. This energy-intensive system has started suffering from other production fatigue owing to over mining of nutrients, declining factor productivity, increasing production cost, reducing farm profitability, deteriorating soil health and labour shortage causing concern about its sustainability2,8. Escalating the production and energy costs in the RW system are not only harmful to keeping productivity and farmers' farm incomes but are also a major challenge for global food and energy security8–10.

Recently, under the situation of intensification of existing cropping systems the energy–farming relationship is becoming more vital11. With the adoption of traditional practices and indiscriminate use of available resources/production inputs use of the energy resources has greater than before remarkably; therefore, to reduce the energy consumption in agriculture while sustaining the food production in this densely populated region, there is a need to be switched over towards more energy-efficient crop management practices. In recent past, various energy-smart agricultural practices have been identified and validated for energy-intensive traditional practices in RW rotation1,11.

Energy smart agriculture (ESA) practices namely laser land levelling, zero tillage (ZT), direct-seeded rice (DSR), site-specific nutrient management (SSNM) and precision irrigation management have been suggested as potentially sustainable alternatives to traditional energy-intensive practices. Non-requirement of intensive tillage operations in energy-smart agriculture translates into less diesel requirement, lesser working time and slower depreciation rates of equipments. These all are reducing energy inputs in various farm operations, particularly from land preparation, as well as from the agricultural machinery manufacturing processes6. By adopting the ESA-based ZT system under the RW system, farmers could save 36 L diesel ha-1 which is equivalent to 2027 MJ ha −1. In addition, energy-intensive agricultural practices have high carbon footprints especially, greenhouse gases (CO2, N2O, CH4, etc.)12, have enhanced the global energy budget by more than 10 times since the beginning of twentieth century13and at the same time increased the cost of cultivation in crop production by approximately 4 times than ZT farming during the same period14. Therefore, energy requirements can be minimized by adopting of energy-efficient technologies. Furthermore, adequate availability of the accurate source of energy and its effective and proficient use are the prerequisites for the conventional RW system with the lowest energy inputs12. In energy budgeting, it is essential to identify or develop energy-efficient technologies, with less energy and environmental footprints. A number of climate smart agriculture (CSA) practices have been assessed in cereal systems as an alternative to energy-intensive traditional practices. So far, information on energy footprints of these practices together (as a portfolio) is scanty. Hence, there is an urgent need for a scientific assessment to use a holistic tactic of principles and procedures known to increase the energy-use efficiency (EUE) and decrease the input energy as well as associated carbon footprints in crop production.

In the IGP of South Asia, most research reported only productivity, profitability and water use efficiency under RW rotation. Thus, the present on-farm multi-location participatory research was carried out within climate-smart villages of Haryana (India) for 3-years to test the hypothesis that CSA improves the EUE, decreases the carbon footprints, cost of production and efficient use of production inputs in the RW system without jeopardizing the productivity of the crops relative to those for the conventional management practice of the RW production system, and offers a hygienic and environmentally sustainable energy use efficient production technology for this IGP region of India. The key objectives of the study were to: (1) to find out the energy conservation and energy-efficient agricultural practices for the RW system in western IGP of India; (2) to assess the key energy indicators and inputs for the RW system; and (3) to study the economic feasibility of most energy-efficient practices in the RW system.

Results and discussion

Source and operation-wise energy utilization pattern

Field operations/seedbed preparation

Energy used in different field operations under various crop management activities was significantly affected by the rice establishment methods and was ranged from 422 to 436 MJ ha−1 (Table 1 and Fig. 1, S2). Business as usual (Sc1) with high energy intensive practices consumed the highest (4336 MJ ha−1) energy in seed bed preparation, whereas in Sc5 and Sc6 no energy was required for seed bed preparation (Fig. 1). CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) consumed 57% less energy in crop establishment (transplanting/sowing) operations compared Sc1 (978 MJ ha−1). Irrespective of field operations, tillage consumed highest input energy in conventional management practice of RW system. This was due to repeated (5–6 passes) dry and wet tillage to prepare a seedbed for nursery raising and puddling consumed more diesel in machinery in Sc1. In addition to this, Sc1 and Sc2 required 15–20 additional manual labour for transplanting rice seedlings.

Table 1.

Energy (MJ ha−1) utilization pattern under different management practices in rice and wheat (mean of 3-years).

| Scenarios | Field operations | Agronomic inputs | Labor | Harvesting & threshing | Transportation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tillage | Puddling | Sowing/transplanting | Seed | Fertilizers | Pesticides | Irrigation | Weeding | Input application | |||

| Rice | |||||||||||

| Sc1 | 1977 | 1381 | 978 | 184 | 14,748A | 1993 | 20,471A | 47.04 | 2394A | 1126 | 385 |

| Sc2 | 1977 | 1381 | 978 | 184 | 14,748A | 1993 | 20,471A | 47.04 | 2394A | 1126 | 385 |

| Sc3 | 1310 | 0 | 422 | 294 | 13,474B | 351 | 17,727B | 62.72 | 2011B | 1126 | 385 |

| Sc4 | 1310 | 0 | 422 | 294 | 13,474B | 341 | 16,692C | 62.72 | 1896C | 1126 | 385 |

| Sc5 | 0 | 0 | 422 | 294 | 13,637B | 541 | 15518D | 62.72 | 1765D | 1126 | 385 |

| Sc6 | 0 | 0 | 422 | 294 | 12,491C | 541 | 15,518D | 62.72 | 1765D | 1126 | 385 |

| Wheat | |||||||||||

| Sc1 | 2228 | -NA- | 850 | 1470 | 14,328A | 364 | 3928A | 16 | 471A | 845 | 369 |

| Sc2 | 2228 | -NA- | 850 | 1470 | 14,328A | 364 | 3928A | 16 | 471A | 845 | 369 |

| Sc3 | 1382 | -NA- | 594 | 1470 | 12,752B | 352 | 3831A | 16 | 453A | 845 | 369 |

| Sc4 | 0 | -NA- | 892 | 1470 | 12,752B | 462 | 3236B | 0 | 393B | 845 | 369 |

| Sc5 | 0 | -NA- | 892 | 1470 | 11,597C | 462 | 3236B | 0 | 393B | 845 | 369 |

| Sc6 | 0 | -NA- | 892 | 1470 | 10,809D | 462 | 3236B | 0 | 393B | 845 | 369 |

Values with different Upper case (A–D) letters are significantly different between each scenarios at p < 0.05 (Duncan multiple range tests for separation of mean).

Sc1, business as usual or conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert.

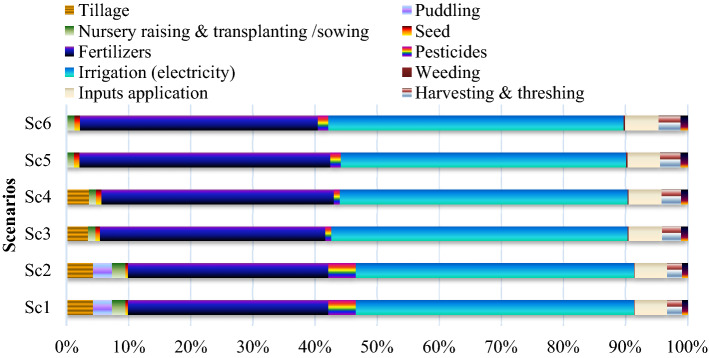

Figure 1.

Operation-wise input energy-use pattern (%)under different management practices in rice. Where; Sc1, business as usual-conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert.

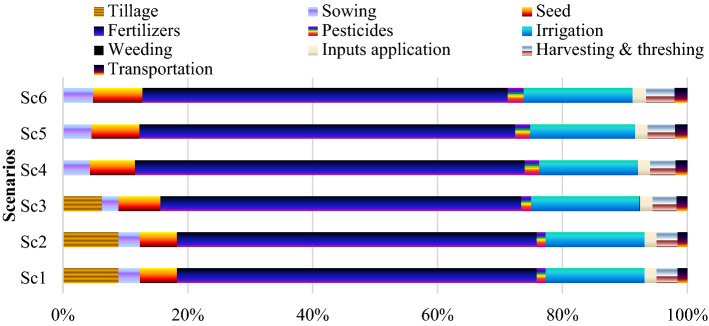

In wheat, energy used under different management practices for seedbed preparations ranged from 892 to 3078 MJ ha−1 and were significantly affected by crop establishment method (Table 1). In seedbed preparation, Sc1 and Sc2 consumed highest energy (2228 MJ ha−1) followed by Sc3 (1382 MJ ha−1), whereas in Sc5 and Sc6 no energy was required for seed bed preparation. Sc3-Sc6 consumed ~ 53% less energy in seedbed preparation and in sowing compared to Sc1 (Fig. 2). Business as usual (Sc1) consumed more energy because of it required more tillage operations in seedbed preparation1,4. However, in CSAP, tillage is not required for seeded preparation and energy is used only for seed sowing.

Figure 2.

Operation-wise input energy-use pattern (%) under different management practices in wheat. Where; Sc1, business as usual or conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert.

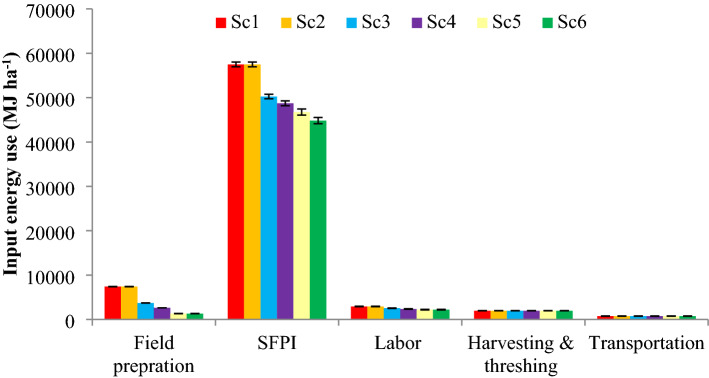

On the system basis, CSAP consumed 76% less energy in seed bed preparation compared to Sc1 (7416 MJ ha−1) (Fig. 3). The higher energy consumption in tillage could be due to fewer usages of modern agricultural machineries and higher use of human & animal power in conventional RW production (Fig. 3). These findings are in support of many other researchers they revealed that diesel consumption (15–20 L ha−1) can be reduced by minimizing numbers of tillage operations5,6. Gathala et al.9 and Laik et al.11 have also described that more tillage operations are the biggest energy consumer (~ 40% of the total energy) compared to best agronomic management practices.

Figure 3.

Operation-wise input energy-use (%) of RW system under different management practices. Where; SFPI are seed, fertilizer, pesticides and irrigation. Sc1, business as usual-conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, REDUCE tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert. Vertical bars indicate ± S.E. of mean of the observed values.

Seed, fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation (SFPI)

In rice production, agronomic energy inputs (SFPI) consumed ~ 84% of the total energy inputs, of which irrigation alone consumed about 46% (mean of six scenarios’ total energy input 3,8483 MJ ha−1) (Table 1 and Fig. 1, S2). Sc1 (puddled transplanted rice; PTR) consumed 29% higher energy in irrigation compared to CSAP (direct seeded rice; DSR) (Fig. 1). This was due to more electricity consumption in lifting of irrigation water from borewell for nursery raising, puddling operations and continuous flooding of water to complete the life cycle of crops. Furthermore, inorganic fertilizers were the second most important input that accounted for ~ 36% of total energy. Chaudhary et al.4and Pathak et al.15 stated that out of the total energy, about 43% energy is required for irrigation and fertilizers in rice production. The CSAP consumed 76, 22 and 11% less energy in pesticides, irrigation and fertilizer, respectively compared to Sc1 (Fig. 1). However, the seed energy was lower in Sc1 (transplanting methods) of rice production than CSAP (DSR), since the seed rate was used lower in PTR; these results were in accordance with Chaudhary et al.4 and Yuan et al.12. Similarly, CSAP (DSR) recorded 87% more energy for weed control and inter-cultivations than Sc1 (PTR), due to use of higher amount of herbicides in DSR (Sc3–Sc6). While in PTR (Sc1 and Sc2), submergence of water minimized the weed problem, which contributed to lesser use of herbicides. Nevertheless, the energy savings in various interculture operations and weed management practices under PTR weren't enough to compensate its more energy consumption in nursery raising, puddling for rice seedling transplantation and irrigation. Overall, Sc6, Sc5, Sc4 and Sc3 consumed 23, 20, 18 and 15% less energy in SFPI compared to Sc1 (37,212 MJ ha−1) (Fig. 1). Laik et al.11 and Nassiri et al.16 results are validated by those who reported the highest energy consumption in conventional RW production system compared to CA based RW system.

Like rice, in wheat production also, agronomic energy inputs/SFPI were the major energy consumers that contributed nearly 84% energy out of the total energy (21,660 MJ ha−1) (Table 1). Among the agronomic inputs (SFPI), fertilizer (F) was the foremost energy input requiring about 70% energy (18,208 MJha−1) of the total energy. Furthermore, irrigation is the second major energy consumer that contributed around 16% of the total agronomic energy inputs (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Overall, CSAP consumed 18.2 and 17.6% lesser energy in fertilizer and irrigation respectively, compared to Sc1 (14,328 and 3928 MJ ha−1) (Fig. 2). Less fertilizer and irrigation requirement under CSAP was due to precision agronomic input management, whereas, in Sc1 more use of N fertilizer and irrigation was made it more energy intensive. However, CSAPs consumed 26% higher energy in pesticides than to Sc1 (364 MJ ha−1). Sc6, Sc5, Sc4 and Sc3 consumed 20, 17, 11 and 8% less energy under SFPI compared to Sc1 (20,090 MJ ha−1). The findings of the present study are in accordance with some researchers12. On the system basis, CSAP consumed 19% lower energy under agronomic inputs/SFPI compared to Sc1 (57,485 MJ ha−1) (Fig. 3).

Crop managements, harvesting and threshing

The energy utilization pattern for rice production in different crop management operations (intercultural, weeding and inputs application) are presented in Table 1 and Fig. S2. In 3-years, CSAP consumed 23% less energy under various crop management activities compared to Sc1 (2394 MJ ha−1). Among the crop management practices, CSAP consumed 33% higher energy in weeding operation compared to Sc1 in rice production (Fig. 1). Likewise, in wheat production, Sc6 and Sc5 computed 19% less energy in crop management activities compared to Sc1 (487 MJ ha−1). Sc1, Sc2 and Sc3 consumed 15.6 MJ ha−1 higher energy in weeding operations whereas, no energy required in weeding under CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) (Table 1). The similar energy use pattern was recorded under all scenarios for harvesting and threshing operations in both the crops (Fig. 2). In RW system, CSAP and Sc3 consumed 23 and 13% less energy in input application compared to Sc1 (2264 MJ ha−1), respectively (Fig. 3). The highest energy use in various crop management practices under Sc1 was due to more energy required for the application of fertilizers, pesticides, hand weeding and inter-culture operations compared to CSAP. Findings of current study are in accordance who also recorded that smart crop management practices required less energy compared to conventional practices4,5,12,17.

Direct–indirect and renewable–non-renewable energy

In rice production, direct and non-renewable energy consumption was more than indirect and renewable energy (Table 2). Direct energy in different cultivation methods of rice was in the range of 57–63%, whereas indirect energy was 37–43% of total energy consumed. Among the direct energy sources, application of irrigation water in all scenarios of rice cultivation consumed the highest direct energy, which showed that irrigation methods in rice cultivation should be standardized with low water use for its future sustainability. The findings of past researchers highlighted that more tillage operation before planting needed around 1/3rd of the total field operational energy, and that can be saved without affecting the crop yields with the adoption of zero tillage based rice cultivation practices6,9,15,18. CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) recorded 43 and 17% less consumption of direct energy & indirect energy in rice cultivation compared to Sc1 (19,264 and 5735 MJ ha−1), respectively. The Sc3 also recorded 20 and 17% less consumption of direct & indirect energy compared to Sc1, respectively (Table 2). The contrast effects (BAU vs CSAP and I-BAU vs CSAP) were significant for direct and indirect energy (Table S2). However, BAU versus I-BAU was not-significant for direct energy but significant for indirect energy.

Table 2.

Total energy input (MJ ha−1) in the form of direct, indirect, renewable and non-renewable energy for different management practices under the rice, wheat and RW system.

| Scenarios | Direct energy | Indirect energy | Renewable energy | Non-renewable energy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | System | Rice | Wheat | RW system | |

| Sc1 | 28744A | 8707A | 37,452A | 16,925A | 16,162A | 33087A | 2624A | 1957A | 4582A | 43,045A | 22,912A | 65,957A |

| Sc2 | 28744A | 8708A | 37,452A | 16,925A | 16,162A | 33,087A | 2624A | 1957A | 4582A | 43,045A | 22,912A | 65,957A |

| Sc3 | 23029B | 7490B | 30,519B | 14,120C | 14,574B | 28,694B | 2368B | 1939A | 4306B | 34,781B | 20,125B | 54,906B |

| Sc4 | 21879C | 5985C | 27,864C | 14,110C | 14,684B | 28,794B | 2253C | 1863B | 4115C | 33,736C | 18,806C | 52,542C |

| Sc5 | 19264D | 5735C | 24,999D | 14,473B | 13,529C | 28,002C | 2122D | 1863B | 3985D | 31,615D | 17,401D | 49,016D |

| Sc6 | 19264D | 5735C | 24,999D | 13,326D | 12,741D | 26,068D | 2122D | 1863B | 3985D | 30,468E | 16,613E | 47,082E |

Values with different upper case (A–E) letters are significantly different between each scenarios at p < 0.05 (Duncan multiple range tests for separation of mean).

Sc1, business as usual-conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert.

The contribution of renewable energy was very low in rice cultivation methods and it highlighted that the cultivation of rice is mainly based on non-renewable sources4,5,11,15. In our study, higher percent of electricitical energy consumed for water pumping from tube-wells, could be owing to less charges of electricity in Haryana, India19–21. In the study`s area, electric energy consumed in crop production is generated mostly from non-renewable sources, particularly fossil fuels. Furthermore, non-renewable sources are still the main fuel in power plants. The contrast effect (BAU vs CSAP) was significant for renewable and non-renewable energy (Table S2).

In wheat cultivation methods, indirect & non-renewable energy consumption was greater than the direct & renewable energy. Less renewable energy uses in wheat cultivation showed that wheat production is mainly based on non-renewable resources. CSAP recorded 52 and 19% less direct and indirect energy in wheat cultivation compared to Sc1, respectively (Table 2).

In RW system, direct and indirect energy consumption varied from 24,999 to 37,452 MJ ha−1 and 26,068 to 33,087 MJ ha−1, respectively (Table 2). Business as usual required more direct energy (diesel in field operations, electricity in irrigation and labour in crop management) than indirect energy in the CT-based RW system. However, CSAP required less direct energy compared to indirect energy, which showed that less number of field operations are required under CSA-based RW production system. The contrast effect (BAU vs CSAP) were significant to direct and indirect energy (Table S2).

In RW system, higher renewable & non-renewable input energy was recorded under Sc1 and Sc2 (4582 and 65,957 MJ ha−1) followed by Sc3 (4306 and 54,906 MJ ha−1) as compared to CSAP (3985 and 47,082 MJ ha−1) (Table 2). The contrast effects were significant to renewable & non-renewable energy (Table S2). Present study indicated that conventional RW production system in the IGP plains are mostly dependent on non-renewable energysources4,15,20,22. Overall, non-renewable energy through fuel, electricity for ground water, inorganic fertilizers, pesticides and farm machineries shared maximum energy inputs followed by renewable resources viz.,labour, tractor, seed, etc.11,15,18. Dependence on non-renewable energy impacted the sustainability of the RW system15. Noteworthy, renewable energy is eco-friendly as well as reliable source of energy; hence, the use of renewable energy highlighted huge benefits, counting lesser contributions to greenhouse gasses emissions and enhanced environmental quality5. The present findings highlighted that more focus should be kept to improve, renewable energy use, technical innovation and optimized investment in rice and wheat production.

Energy balance sheet (input–output and net energy)

The total energy used for various rice production methods varied from 32,606 to 45,685 MJ ha−1 and was significantly affected by different crop management practices (Table 3). Our study results are in track with those of other similar research studies conducted in the IGP region for RW system4,5,11. Among the different rice production methods, PTR cultivation method (Sc1) of rice noted higher energy input than the CSAP (DSR method). Sc1 (32,606 MJ ha−1) recorded 40, 35, 27 and 23% higher energy use in rice production over Sc6, Sc5, Sc4 and Sc3, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, Sc1 (32,606 MJ ha−1) recorded 35, 29, 22 and 13% higher energy use in wheat production over Sc6, Sc5, Sc4 and Sc3, respectively. The CSAP and Sc3 used 24 and 16% less energy under RW system compared to Sc1 (70,538 MJ ha−1), respectively. However, CSAP recorded higher energy output from rice, wheat and RW system compared to Sc1. Compared to Sc1, the CSAP produced 1, 14 and 6% higher grain output energy under rice, wheat and system, respectively. The minimum input and maximum output energy under Sc6 were due to gained more net energy for both the crops during the respective years (Table 3). Linear contrast effects were significant to total energy input in rice, wheat and RW production systems. However, contrast effects were not significant to energy input in rice and RW system but significant to wheat production system.

Table 3.

Energy (MJ ha−1) balance under different management practices in rice, wheat and RW system (mean of 3 years).

| Scenarios | Total energy input | Energy output | Net energy | Energy use efficiencyc | Grain energy productivity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | RW system | Rice | Wheat | RW system | |

| Sc1 | 45,685 | 24,869 | 70,538A | 217,461B | 153,780C | 371,241C | 171,792E | 79,378C | 300,703D | 4.77D | 6.19E | 5.27D | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Sc2 | 45,685 | 24,869 | 70,538A | 220,720B | 156,036BC | 376,756C | 175,051DE | 80336BC | 306,218D | 4.84D | 6.28E | 5.35D | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Sc3 | 37,165 | 22,063 | 59,212B | 217,292B | 162,005B | 379298C | 180,144CD | 82,831B | 320,085C | 5.86C | 7.34D | 6.41C | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| Sc4 | 36,005 | 20,669 | 56,657C | 221,854AB | 169,805A | 391,659B | 185,865BC | 86,971A | 335,002B | 6.19BC | 8.22C | 6.92B | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.22 |

| Sc5 | 33,753 | 19,264 | 53,001D | 222,944AB | 173,759A | 396,704AB | 189,208AB | 88,872A | 343,703AB | 6.64AB | 9.03B | 7.51A | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.24 |

| Sc6 | 32,606 | 18,476 | 51,067E | 228,562A | 175,866A | 404,428A | 195,972A | 89,906A | 353,362A | 7.05A | 6.19E | 7.94A | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.26 |

Values with different upper case (A–E) letters are significantly different between each scenarios at p < 0.05 (Duncan multiple range tests for separation of mean).

Sc1, business as usual-conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert.

In rice production, the energy saving under CSAP was due to less energy inputs used in electricity that was associated with less irrigation water use in cultivation4,5,11. Efficient water management practice had a positive effect on energy consumption5,11and diverse energy sources across water regimens in India1,12,16. Our study showed that the energy input in existing rice and wheat production can be further minimized with precision water management techniques and, optimization of irrigation water management based on the precision land-levelling, frequent irrigation in rice, tensiometer based irrigation and zero tillage can efficiently decrease the total energy consumption in the IGP of India2,11.

On an average, fertilizer was the first and second largest source of energy consumption in rice and wheat in all scenarios (Figs. 1 and 2), respectively. Aggregate proof from the current study and other similar studies highlighted that fertilizer consumption created the major share of the total energy input in crop production10–12. Among different fertilizers, N-fertilizers consumed the most energy input and constituted 94% in Sc1 and 87% in CSAP of the energy from fertilizers in RW system. From several past evidences, it is crystal clear that fertilizer application is exceeded to the highest demand for crop growth & development in this region, that further encouraged low resource use efficiency (RUE) and higher environmental footprints23,24. Thus, it is necessary to use fertilizers efficiently to reduce energy use and to prevent environmental degradation. Overall, the higher energy input was allied with more tillage, labour, irrigation and higher use of N-fertilizers in Sc1 compared to CSAP. Erenstein et al.6, Gathala et al.9and Ladha et al.3 also described that more tillage for seed bed preparation, more number of irrigation, higher labour and higher fertilizer inputs are the main interventions for higher energy usage under traditional farming. The higher output energy of rice, wheat and RW system with CSAP might be due to the multiple effects of applied nutrients1, zero tillage5, residue management, improved soil health2, good water regimes5,11and improved nutrient use efficiency (NUE) relative to Sc1. The CSAP recorded greater crop yields that ultimately reflected to greater net energy, EUE, human energy profitability, EP, over conventional methods of RW system.

Energy use efficiency (EUE) and productivity

Energy use efficiency is an index used to measure the amount of energy that is effectively used in different farm activities. The highest input and the lowest output energy under Sc1 resulted into the lowest EUE and energy productivity (EP). Contrarily, the lowest energy input and the highest energy output under CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) resulted into the maximum EUE and EP in both the crops in all the study’s years (Table 3). The average energy use efficiency was 52, 53 and 54% higher under Sc6 in rice, wheat and RW system compared to Sc1 (Table 3), respectively. CSAP recorded 44% (7.57 MJ MJ−1) higher EUE compared to Sc1 (5.28 MJ MJ−1) in the RW system. Linear contrast effects were also significant to EUE in rice, wheat and RW production systems. The large gap among the two values was due to tillage, irrigation and fertilizers which highlighted that EUE can be enhanced with reduced tillage, precision use of irrigation water and nutrient. Remarkably, the values observed in the current finding fall around the range described by other researchers11 who revealed that the EUE of RW production in IGP ranged 3.94 ± 1.31 MJ MJ−1. Overall, the results of the current study showed that those existing production methods of the RW system in IGP are not too efficient. Besides, RW system is damaging to agro-ecosystems because of imbalance and excess use of inputs. Hence, efficient use of production inputs would be helpful in optimizing energy consumption in RW system in the IGP region of South Asia.

Energy productivity (EP) was statistically higher in the Sc6 in rice (0.15 kg MJ−1), wheat (0.21 kg MJ−1) and RW system (0.17 kg MJ−1) than in the Sc1 (Table 3). These findings revealed that an additional ~ 27% of RW system yield was gained per unit energy input in the Sc6 compared with the other scenarios (0.20 kg MJ−1). CSAP recorded 40% higher EP compared to Sc1 (0.17 kg MJ−1) in RW system. Linear contrast effects were significant to EP in rice, wheat and RW production systems (Table S2). The EP indices can be used for assessing the crop production associated environmental effects25. About agro-ecosystem sustainability, earlier research findings have highlighted that EP indicator could be used to judge optimal land and crop management intensities11,14. This study suggests there is an enormous potential for enhancing the energy productivity and efficiency of RW system in the IGP. CSA scenarios (Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) improved EUE and EP in rice, wheat as well as RW system, was due to lower energy input and higher energy output relative to Sc1. The findings of our research are in line with those who has described that CA-based management practices can reduce energy input and increase output4,5,11,14.

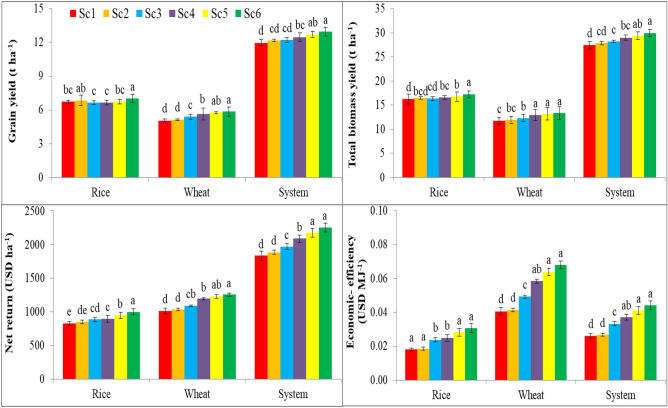

Yields, farm profitability and economic efficiency (Eco-efficiency)

The rice yields were not much influenced by different crop management. However, in wheat, CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) produced 11–16% and 10–13% higher grain and biomass yield, respectively compared to BAU. The grain and biomass yield of RW system was improved by 4–8 and 6–9% under CSAP, respectively relative to Sc1 (3-years’ mean) (Fig. 4).The CSAP improved the net income of rice, wheat and RW system by 15, 21 and 23% (3-years’ mean), respectively relative to Sc1 (US$ 824 and 1009 and 1833 ha−1, respectively) (Fig. 4). Linear contrast effects were significant to the net income in rice, wheat and RW production systems (Table S2). Higher net income was associated with CSAP due to less cultivation cost in various crop production activities such as tillage, crop establishment and irrigation9. Researcher observed that escaping field operations particularly tillage puddling and manual transplanting in rice and adoption of ZTDSR minimized tillage and establishment costs by 79–85%. CSAP improved crop yields while reducing production costs resulting in greater profitability of the RW system.

Figure 4.

Effect of management practices portfolios on net return and eco-efficiency in rice, wheat and RW system (Mean of 3 years). Where; Sc1, business as usual-conventional tillage (CT) without residue; Sc2, CT with residue; Sc3, reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF); Sc4, RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF; Sc5, ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer; Sc6, Sc5 + Nutrient expert. Values with different lower case (a–e) letters are significantly different between each scenarios at p < 0.05 (Duncan multiple range tests for separation of mean). Vertical bars indicate ± S.E. of mean of the observed values.

The results showed that eco-efficiency varied from 0.018 to 0.031 US$ MJ−1 in rice and 0.041 to 0.068 US$ MJ−1 in wheat (Fig. 4). Overall, the eco-efficiency was the highest under CSAP in both the crops and the lowest under Sc1. Based on 3-years mean, CSAP recorded 56 and 57% higher eco-efficiency under rice and wheat than Sc1 (0.018 & 0.041 US$ MJ−1) (Fig. 4), respectively. Higher eco-efficiency of rice and wheat under CSAP (Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) was due to lower energy input and more net returns in these scenarios as compared to Sc1. Linear contrast effects were significant to the eco-efficiency in rice, wheat and RW production systems (Table S2). Present study results suggested that eco-efficiency of RW system can be enhanced by the adoption of CSAP which can reduce the negative environmental impacts while at the same time can able to maintain or increase the farm returns26. Therefore, CSAP of RW systems with higher eco-efficiency are reflected as more economically and environmentally sustainable. Present finding also suggests that there is a huge potential exists for improving the eco-efficiency of RW production in the IGP.

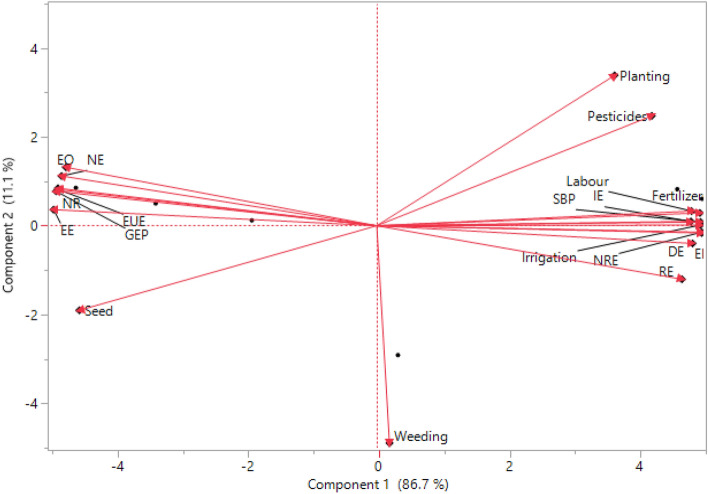

Principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation

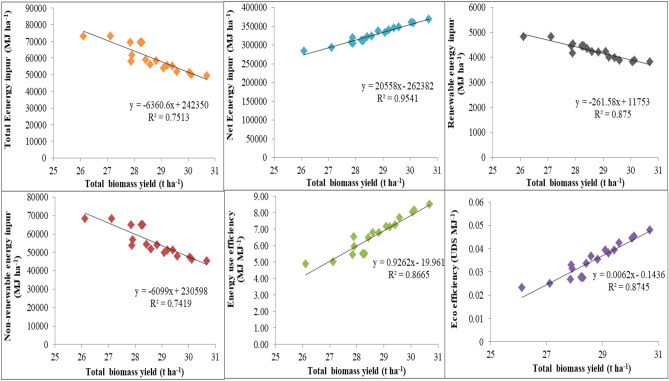

Scatter plot of scenarios on PCA coordinates showed that BAU based scenarios are distinctly located on PCA coordinates (Fig. 5). Sc1, Sc2 and Sc3 scenarios are positioned in right-hand-side coordinates with higher weightage of PC1 (86.7% of total variance). A close association between energy parameters like fertilizer, irrigation, seed bed preparation, labour, sowing/planting, pesticides, direct energy, indirect energy, renewable energy, non-renewable energy, total energy inputs and net energy is also apparent from the PCA graph. The estimated energy components of various energy inputs were more under business as usual (BAU) due to higher energy use for tillage, irrigation, fertilizer use and pesticides in comparison to CSAP. However, the total energy inputs were lesser in CSAP (mean of Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6) followed by Sc3 and maximum in Sc1 and Sc2. This might be due to precise input management, proper crop establishment, efficient water management and efficient nutrient management. Layering of climate smart agriculture practices are significantly improves crop productivity and economics2. Present study results showed that the total energy inputs were correlated (positively or negatively) with energy output, net energy, EUE, EP, net return and eco-efficiency (Table S3). In particular, energy inputs were significantly negatively correlated with grain energy output (r = 0.96, p < 0.001) net energy (r = 0.97, p < 0.001), energy use efficiency (r = 0.98, p < 0.001), energy productivity (r = 0.98, p < 0.001), net return (r = 0.98, p < 0.001) and eco-efficiency(r = 0.99, p < 0.001) (Table S3). This strong correlation may be due to lower energy input and higher output energy27. Regression and Pearson’s correlation analysis were performed between the total biomass production and energy parameters (total energy inputs, net energy input, renewable and non-renewable energy inputs, energy and eco- efficiency) for validation purposes (Fig. 5). Total biomass yield of different management practices was significantly correlated to total energy inputs(R2 = 0.75, p < 0.001), net energy input (R2 = 0.95, p < 0.001), renewable energy (R2 = 0.88, p < 0.001), non-renewable energy (R2 = 0.74, p < 0.001), energy use efficiency (R2 = 0.87, p < 0.001), and eco-efficiency (R2 = 0.87, p < 0.001) under different scenarios explaining their efficiency in predicting energy use efficiency (Fig. 6). Among different management practices, efficient use of energy inputs and higher energy use efficiency was associated with CSAP followed by improved management practices. Similarly5, researcher reported higher energy use efficiency in conservation agriculture based management practices over conventional rice–wheat system in north-west India.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis among the energy and economic indicators under the RW system; Where; SBP seed bed preparation, DE direct energy, IE indirect energy, RE renewable energy, NRE non-renewable energy, EI energy input, EO energy output, NE net energy, EUE energy use efficiency, GEP grain energy productivity, NR net return, EE eco-efficiency.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the biomass yield and energy parameters (total energy inputs, net energy input, renewable and non-renewable energy inputs, energy and eco- efficiency).

Conclusion

In our study, we attempted to explain the intricacies of energy input–output and energy flow of various management practices in the rice–wheat production system. In the study, it was found that rice–wheat production under business as usual (BAU) relies mostly on non-renewable energy sources; therefore, climate smart agriculture practices (CSAP) should be adopted to make use of available resources efficiently. Eco-efficiency of RW system was 57% higher under CSA scenarios compared to Sc1. A higher eco-efficiency reflects that CSAP are more economically and environmentally sustainable for RW system. Our results further showed that BAU practices under RW production in IGP of India is energy-input intensive as compared to CSAP. Thus, based on our study, we suggest that adopting CSAP portfolios can not only help in adapting to climatic risks but also provides viable tactic for enhancing energy output, energy use efficiency, eco-efficiency and keep productivity at its best. Energy management in RW production system should be considered as a key component in terms of efficient, sustainable and economical use of energy.

Materials and methods

Experimental site and climatic condition

A 3 years (2014–2017) on-farm study was carried out in three different climate smart villages i.e., Birnarayana (29° 75′ N, 76° 86 E), Anjanthali (29° 83′ N, 76° 88′ E) and Chandsamand (29° 80′ N, 77° 10′ E) at Karnal, India (Fig. S1). The climate of experimental sites are sub-tropical characterized by hot and dry summer and cold winters and receives nearby 70 cm annual rainfall, 80% of that occurs between June to September.

Experimental details and management

The on-farm trials were initiated in the rainy season 2014, with six treatment combinations denoted as scenarios (Tables 4 and 5). The term scenario is a portfolio of agronomic practices where more than two agronomic interventions are used. Five different alternative scenarios related to, crop establishments, tillage, in-situ crop residue management, nutrient, and irrigation management were evaluated for business as usual practices (BAU) of the RW system. Six management scenarios (portfolios of management practices) were i.e.,Sc1-Business as usual(BAU)/Conventional tillage (CT) without residue, Sc2-CT with residue, Sc3-Reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF), Sc4-RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF, Sc5-ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer, Sc6-Sc5 + Nutrient expert were included (Tables 4 and 5). The varied portfolio of climate smart agriculture practices (CSAP) were layered in Sc4, Sc5 and Sc6. Sc1 and Sc2 are related to intensive tillage operation whereas Sc3 is related to reduce tillage operation with the traditional agronomic packages, and practices. Sc5 and Sc6 are related to no-tillage with modern agronomic packages and practices (Table 5). In scenario 6, the site-specific nutrient management (SSNM) approach was used to tailor the recommended nutrient doses using Nutrient Expert (NE) instead of RDF layered with Green Seeker guided N. Nutrient Expert is an interactive, computer-based decision-support tool that enables the implementation of SSNM in individual fields without soil test data28.

Table 4.

Scenario notations and description of management protocols under different scenarios in rice–wheat (RW) system.

| Scenarios | Tillage | Crop establishment | Laser land leveling | Residue management | Water management | Nutrient management | ICT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Details | |||||||

| Sc1 | Business as usual (BAU)or Conventional tillage (CT) without residue | CT | TPR with random geometry. CTW using seed broadcasting | No | Residue removed | FP | FFP | None |

| Sc2 | CT with residue | CT | TPR with random geometry. CTW using seed broadcasting | No | 100% of rice and 25% of wheat residue incorporated | FP | FFP | None |

| Sc3 | Reduce tillage (RT) with residue + recommended dose of fertilizer (RDF) | RT | DSR sown with MCP. RTW sown with RDD | No | Same as in Sc2 | SR | RDF | None |

| Sc4 | RT/Zero tillage (ZT) with residue + RDF | RT-ZT | DSR sown with MCP. ZTW sown with HS | Yes | 100% rice residue retained and 25% wheat residue incorporated | SR | RDF | None |

| Sc5 | ZT with residue + RDF + GreenSeeker + Tensiometer | ZT | DSR and ZTW sown with HS | Yes | 100% of rice residue and 25% of wheat retained | Tensiometer based | RDF + GS guided N | Yes |

| Sc6 | Sc5 + Nutrient expert | ZT | Same as in Sc5 | Yes | Same as in Sc5 | Tensiometer based | NE + GS guided N | Yes |

CT conventional tillage, RT reduced tillage, ZT zero tillage, TPR transplanted rice, CTW conventional till wheat, DSR direct seeded rice, MCP multi crop planter, RTW reduced till wheat, RDD rotary disc drill, ZTW zero till wheat, HS happy seeder, SR state recommendation for irrigation, FFP farmer’s fertilizer practice, RDF recommended dose of fertilizer, NCU neem coated urea, GS green seeker, NE nutrient expert based fertilizer recommendation, ICT information and communication technology.

Table 5.

Crop management practices for rice–wheat (RW) system under different scenarios.

| Scenariosa/management practices | Sc1 | Sc2 | Sc3 | Sc4 | Sc5 | Sc6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field preparation |

Rice—2 pass of harrow, 1 pass of rotavator, 2 pass of puddle harrow followed by (fb) planking; Wheat- 2 pass of harrow and rotavator each fb planking |

Same as in Sc1 |

Rice-1 pass of harrow, 1 pass of cultivator fb planking; Wheat-1 pass of harrow, 1 pass of cultivator fb planking |

Rice—Same as in Sc3; Wheat- Zero tillage |

Zero tillage | Same as in Sc5 |

| Seed rate (kg ha−1)b | Rice-12.5 kg and wheat100 kg | Same as in Sc1 | Rice-20 kg and wheat-100 kg | Same as in Sc3 | Same as in Sc3 | Same as in Sc3 |

| Crop geometry | Random geometry | Same as in Sc1 | 22–20 cm | Same as in Sc3 | Same as in Sc3 | Same as in Sc3 |

| Source of fertilizers | Urea (46:0:0) and Di-ammonium phosphate (DAP) (18:46:0) | Same as in Sc1 | Urea, DAP, Muriate of potash (MOP) (0:0:60), and NPK complex (12:32:16) | urea (46:0:0), DAP, MOP and NPK complex | Same as in Sc4 | Neem coated urea (46:0:0), DAP, MOP and NPK complex |

| Fertilizer (N:P:K) in kg ha−1 |

Rice-195:58: 00; Wheat- 185:58:00 |

Same as in Sc1 |

Rice-150:60:60; Wheat- 150:60:60 |

Same as in Sc3 |

Rice-147:60:60 (in 1st year) 153:60:60 (in 2nd year) and 158:60:60 (in 3rd year); Wheat- 143:60:60 (in 1st year), 120:60:60 (in 2nd year) and 134:60:60 (in 3rd year) |

Rice-138:39:70 (in 1st year), 140:42:57 (in 2nd year) and 145:44:57 (in 3rd year); Wheat-135:62:60 (in 1st year), 111:58:55 (in 2nd year) and 122:56:55 (in 3rd year) |

| Water management |

Rice—Continuous flooding of 5–6 cm depth for 30–40 days after transplanting fb irrigation applied at alternate wetting and drying Wheat- 4–6 irrigation as per requirement |

Same as in Sc1 |

Rice—Soil was kept wet up to 20 days after sowing fb irrigation applied at hair-line cracks Wheat- 4–6 irrigation as per critical crop growth stages |

Same as in Sc3 |

Rice—Soil was kept wet till germination fb irrigation at − 20 to − 30 kPa matric potential; Wheat- Irrigation at − 50 to − 55 kPa matric potential |

Same as in Sc5 |

aRefer Table 4 for scenario description.

bSeed treatment was done with Bavistin + Streptocycline @ 10 + 1 g per 10 kg seed-Raxil; Tebuconazole 2DS (2% w/w ) at 0.2 g a.i. kg−1 seed.

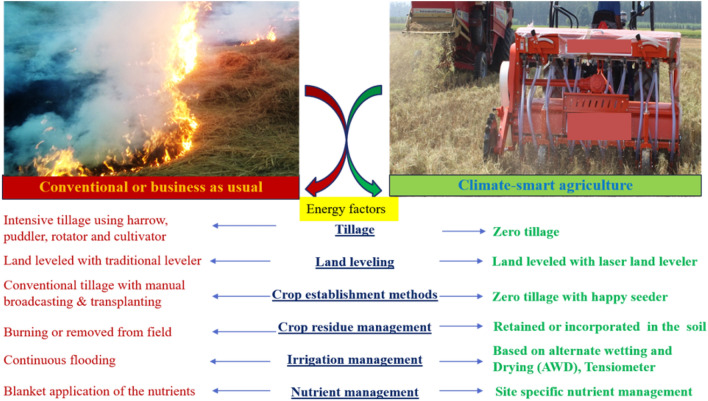

All scenarios were evaluated in ~ 1000 m19 size of plot and it repeated at three locations. Energy`s sources of different management practices (conventional vs climate smart agriculture) are given in Fig. 7. Plant materials were handled according to relevant guidelines and regulations of CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, and ICAR-CSSRI, Karnal, India. The seeds of all the various crop varieties used in this study are readily available in India.

Figure 7.

Energy sources of RW production under conventional management practice (left) and climate-smart agricultural practices (right).

Methods of energy analysis

Manual energy

For the determination of manual energy (ME) following equation was used:

| 1 |

where Lt = Total no. of labour used in different farm operations.

Ut = Useful time consumed in different farm activities by a labour, h

Energy coefficients used for data analysis which are showed in Table 6. Manual labours were documented in each farm activities with working hours that was transformed in man-hours.

Table 6.

Energy equivalents used in the study for different agricultural operations.

| Particulars | Units | Energy coefficients (MJ Unit−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | |||

| Human labour | Man-hour | 1.96 | 22 |

| Diesel | Litre | 56.31 | 22 |

| Nitrogen (N) | Kg | 66.14 | 22 |

| Phosphorus (P2O5) | Kg | 22.44 | 22 |

| Potassium (K2O) | Kg | 11.15 | 22 |

| Herbicides, insecticides and pesticides | Kg | 120.00 | 22 |

| Irrigation water | ha-cm | 143.56 | 22 |

| Zinc sulphate (ZnSO4) | Kg | 8.40 | 12 |

| Iron sulphate (FeSO4) | Kg | 110.00 | 12 |

| Rice and wheat seed | Kg | 14.70 | 22,12 |

| Tractor | Kg | 93.61 | 22 |

| Other machinery | Kg | 62.70 | 22 |

| Combine harvester | Kg | 87.63 | 22 |

| Output | |||

| Rice and wheat seed | Kg | 14.70 | 22,12 |

| Rice and wheat straw | Kg | 12.50 | 22,12 |

Mechanical/power-driven energy

Indirect energy of agricultural machineries was estimated on the basis of total diesel consumed during the seedbed preparation, sowing of crops, harvesting, threshing and transportation, etc. (Table S1)9,14,26. The total time consumed in different operations was also recorded during different farm activities. Total fuel energy was estimated based on the consumption of diesel in various farm operations by using the following equation:

| 2 |

here ME—machinery energy (MJ ha−1), β—energy conversion factor for machinery (MJ kg−1), µ—machinery weight (kg), γ—effective field capacity (ha h−1) and α—life of the machinery (h).

Effective field capacity (γ) was computed by using the following equation:

| 3 |

where EFC—effective field capacity, A—indicates total area covered (ha) and T—time require (h).

The fuel energy was computed with the following equation:

| 4 |

where FE—Fuel energy (MJ ha−1), 56.31 is energy coefficient of diesel (MJ L−1) D—total diesel consumed, L

Irrigation energy

The energy required to pump out the water from the bore wellswas calculated on the basis of following equation:

| 5 |

where DE—Direct energy (MJ ha−1), α—Density of water (1000 kg m−3), β—Acceleration due to gravity (9.80 m s−2), γ-Depth of dynamic head (m), µ–Seasonally volume of water needed (m3 ha−1), y–Pump’s efficiency (80%) and z–Efficiency of power conservation (20%)20. For estimation of irrigation energy, transmission and production efficiencies were also involved.

Inputs energy

Input energy (expressed in MJ ha−1) of each interventions were calculated based on study of other researchers4,9,14. Basic information on energy inputs (like, tillage, fertilizers, pesticides, irrigations, harvesting and threshing, transportation and other crop management activities) and outputs (in terms of rice and wheat yields) were entered into excel spreadsheets. Energy inputs under different management scenarios were calculated by multiplying the inputs with the equivalent energy coefficients (Table 6). The term Indirect-energy indicates to energy used in various forms/activities such as manufacturing, packaging, and transporting of machinery, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, whereas the term direct-energy refers to the energy consumed in the various forms such as diesel, human labour, tractor and electricity. The direct and indirect energy coefficients are presented in Table 6 which took derived from peer-reviewed literature. Below given equations are used for calculation of the following energy parameters4,19,22,29(Table 7).

Table 7.

Equations for calculation of energy parameters.

| Energy types | Components/factors | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Direct energy | Diesel + labour + tractor + electricity | (MJ ha−1) |

| Indirect energy | Machinery + fertilizers + pesticides + seeds | (MJ ha−1) |

| Renewable energy | Labour + tractor + seeds | (MJ ha−1) |

| Non-renewable energy | Machinery + diesel + electricity + chemical fertilizer + pesticides | (MJ ha−1) |

| Total energy input | Direct/renewable + indirect/non-renewable energy | (MJ ha−1) |

| Grain energy output | Energy in the harvested grain (grain) | (MJ ha−1) |

| Total energy output | Energy in the harvested total biomass (grain + straw) | (MJ ha−1) |

| Net energy | Total energy output—energy input | (MJ ha−1) |

| Energy use efficiency | Total energy output/energy input | (MJ MJ−1) |

| Energy productivity | Grain yield/energy input | (kg MJ−1) |

Economic-efficiency (Eco-efficiency)

The term eco-efficiency is an index facilitating adequate de-linking of the use of available natural resources from economic activity or pollutant release from economic activity required to meet human needs. It can be defined as a ratio between economic value-added and an environmental degradation26,30,31. Eco-efficiency of the RW system can be improved by choice climate smart agriculture (CSA) which decreases negative environmental impacts while at the same time maintaining or increasing farm returns32. Therefore, agricultural production systems with higher eco-efficiency are considered more economically and environmentally sustainable. The main target of CSA is to improve its EE by reducing agriculture’s environmental footprints (eg. energy use & emission of GHGs) while increasing farm profit17,26.

Eco-efficiency refers to the efficiency of economic motion in relation to its effect on the environment. The environmental effect can be measured in terms of the total quantity of greenhouse gas emitted (kg CO2 eq.) or energy used (MJ) or by various practices of farming. In this paper, eco-efficiency was computed by using the following equation:

| 6 |

Statistical analysis

This on-farm adaptive research experiment was conducted for consecutive 3-years in a randomized block design (RBD) with three replications. All agronomic data were recorded during field experimentation and were analysed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) technique33. Data analysis was done with the help of SAS 9.1 software34. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) method was used for comparing treatment means at 5% level of significance. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done with JMP 14.1 software. The results were submitted to PCA in order to determine the common relationships between parameters.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by CGIAR Research Programs (CRPs) on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and Wheat Agri-Food Systems (WHEAT) and Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) window 3 funding to CIMMYT for Conservation Agriculture research. In addition, we also acknowledge the CGIAR Fund Council, Australia (ACIAR), IFAD, Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, UK, USAID, Irish Aid, European Union, and Thailand for funding to CCAFS. We also acknowledge the national collaborators (CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar and ICAR) for their support during the study. Many thanks to farmer`s Mr. Vinod Kumar, Mr. Harpreet Singh, and Mr. AmitRana, Karnal for participating in management activities and for providing land for this study.

Author contributions

M.L. and P.S. conceptualized the idea, designed the research and supervised the research. M.L. acquired funding for the research. D.B. analyzed the idea in comparison with previous studies. S.K., I.S., M.G. and M.K. designed the experiment, coordinated fieldwork, implemented on-farm trials and collected data. S.K. and H.S. drafted the manuscript text. S.K., I.S. and H.S. conceived the idea and revised and edited the manuscript. All authors analyzed the data, discussed the results, commented on the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

H. S. Jat, Email: hsjat_agron@yahoo.com

M. L. Jat, Email: M.jat@cgiar.org

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-12686-4.

References

- 1.Hobbs PR, Gupta RK. Resource-Conserving Technologies for Wheat in Rice–Wheat System. In: Ladha JK, Hill JE, Duxbury JM, Gupta RK, Buresh RJ, editors. Improving the Productivity and Sustainability of Rice–Wheat System-Issues and Impact. ASA Special Publication; 2003. pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kakraliya SK, et al. Performance of portfolios of climate smart agriculture practices in a rice–wheat system of western Indo-Gangetic plains. Agric. Water Manag. 2018;202:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2018.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ladha J, Dawe D, Pathak H, Padre A, Yadav R, Singh B, Hobbs P. How extensive are yield declines in long-term rice–wheat experiments in Asia? Field Crops Res. 2013;81:159–180. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00219-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhary VP, Gangwar B, Pandey DK, Gangwar KS. Energy auditing of diversified Paddy-wheat cropping systems in Indo-Gangetic plains. Energy. 2009;34:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2009.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary VP, Singh KK, Pratibha G, Bhattacharyya R, Shamim M, Srinivas I, Patel A. Energy conservation and greenhouse gas mitigation under different production systemsin rice cultivation. Energy. 2017;130:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2017.04.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erenstein O, Laxmi V. Zero tillage impacts in India's rice-wheat systems: areview. Soil Till. Res. 2008;100:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2008.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saharawat YS, et al. Evaluation of alternative tillage and crop establishment methods in a rice–wheat rotation in north western IGP. Field Crops Res. 2010;116:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas A, Waseem M, Yang M. An ensemble approach for assessment of energy efficiency of agriculture system in Pakistan. Energy Effic. 2020;13:683–696. doi: 10.1007/s12053-020-09845-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gathala MK, et al. Productivity, profitability and energetics: A multi-criteria assessment of farmers’ tillage and crop establishment options for maize in intensively cultivated environments of South Asia. Field CropsRes. 2016;186:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan MA, Khan S, Mushtaq S. Energy and economic efficiency of wheat production using different irrigation supply methods. Soil Environ. 2007;26:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laik R, et al. Integration of conservation agriculture with bestmanagement practices for improving system performance of the rice–wheat rotationin the Eastern IndoGangetic Plains of India. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015;195:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan S, Peng S. Input-output energy analysis of rice production in different crop management practices in central China. Energy. 2017;141:1124–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2017.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pratibha G, et al. Impact of conservation agriculture practices on energy use efficiency and global warming potential in rainfed pigeonpea- castor systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2015;66:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2015.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parihar CM, et al. Bioenergy, biomass water-use efficiency and economics of maize-wheat mungbean system under precision-conservation agriculture in semi-aridagro-ecosystem. Energy. 2017;119:245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2016.12.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak BS, Bining AS. Energy use pattern and potential for energy saving in rice–wheat cultivation. Energy Agric. 1985;4:271–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5826(85)90022-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nassiri SM, Singh S. Study on energy use efficiency for paddy crop using dataenvelopment analysis (DEA) technique. Appl. Energy. 2009;86:13–205. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2008.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cicek A, Altintas G, Erdal G. Energy consumption patterns and economic analysis of irrigated wheat and rain-fed wheat production: Case study for Tokat Region Turkey. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2011;17(3):378–388. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faidley LW. Energy and Agriculture. In: Fluck RC, editor. Energy in Farmproduction. Elsevier; 1992. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akcaoz B, Fert CH. Energy requirement input-output analysis in Turkish agriculture. Renew. Energy. 2004;29:39–51. doi: 10.1016/S0960-1481(03)00135-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alluvione F, Moretti B, Sacco D, Grignani C. EUE (energy use efficiency) of cropping systems for a sustainable agriculture. Energy. 2011;36:4468–4481. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2011.03.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argiro V, Strapatsa A, George D, Nanos A, Constantinos A. Energy flow for integrated apple production in Greece. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006;116:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellabban O, Abu-Rub H, Blaabjerg F. Renewable energy resources: Currentstatus, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014;39:748–764. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhary M, Rana KS, Bana RS, Ghasal PC, Choudhary GL, Jakhar P, Verma R. Energy budgeting and carbon footprint of pearl millet: Mustard cropping system under conventional and conservation agriculture in rainfed semi-arid agro-ecosystem. Energy. 2017;141:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2017.09.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulsbergen KJ, Feil B, Biermann S, Rathke GW, Kalk WD, Diepenbrock W. Amethod of energy balancing in crop production and its application in a long termfertilizer trial. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2001;86:303–321. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(00)00286-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan S, Peng S, Wang D, Man J. Evaluation of the energy budget and energy use efficiency in wheat production under various crop management practices in China. Energy. 2018;160:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soni P, Sinha R, Perret SR. Energy use and efficiency in selected rice-based cropping systems ofthe Middle-Indo Gangetic Plains in India. Energy Rep. 2018;4:554–564. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jat HS, et al. Energy use efficiency of crop residue management for sustainable energy and agriculture conservation in NW India. Renew. Energy. 2020;55:1372–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.04.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pampolino M, Majumdar K, Jat ML, Satyanarayana T, Kumar A, Shahi VB, Gupta N, Singh V. Development and evaluation of nutrient expert for wheat in South Asia. Better Crops Plant Food. 2012;96:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta RK, Naresh RK, Hobbs PR, Jiaguo Z, Ladha JK. Sustainability of Postgreen Revolution Agriculture the Rice–Wheat Cropping Systems of the Indo-Gangetic Plains and China. In: Ladha JK, Hill JE, Duxbury JM, Gupta RK, Buresh RJ, editors. Improving the Productivity and Sustainability of Rice–Wheat Systems Issues and Impacts. American Society of Agronomy; 2003. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.OECD. Making Sustainability Accountable: Eco-Efficiency, Resource Productivity and Innovation. In: Fifth Anniversary Workshop of EEA, Copenhagen, European Environment Agency (1998).

- 31.Saling P, et al. Eco-efficiency analysis by BASF: The method. Int. J Life Cycle Assess. 2002;7:203–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02978875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Grosso SJ, Parton WJ, Mosier AR, Ojima DS, Kulmala AE, Phongpan S. General model for N2O and N2 gas emissions from soils due to dentrification. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 2000;14(4):0886–6236. doi: 10.1029/1999GB001226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez KA, Gomez AA. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2. Wiley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 34.SAS Institute, SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Version 8-1; SAS Inst.: Cary, NC, USA (2001).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.