Summary

Background

Uncertainty exists about how best to identify primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients who would benefit from second-line therapy. Existing, purely clinical, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) response criteria accept degrees of liver biochemistry abnormality in responding patients, emerging data, however, suggest that any degree of ongoing abnormality may, in fact, be associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes. This cohort study explores the link between response status, the biology of high-risk disease and its implications for clinical practice.

Methods

Proteomics, exploring 19 markers previously identified as remaining elevated in PBC following UDCA therapy, were performed on 400 serum samples, from participants previously recruited to the UK-PBC Nested Cohort between 2014 and 2019. All participants had an established diagnosis of PBC and were taking therapeutic doses of UDCA for greater than 12 months. UDCA response status was assessed using Paris 1, Paris 2 and the POISE criteria, with additional analyses using normal liver blood tests stratified by bilirubin level. Statistical analysis using parametric t tests and 1-way ANOVA.

Findings

Disease markers were statistically significantly higher in UDCA non-responders than in responders for all the UDCA response criteria, suggesting a meaningful link between biochemical disease status and disease mechanism. For each of the criteria, however, marker levels were also statistically significantly higher in responders with ongoing liver function test abnormality compared to those who had normalised their liver biochemistry. IL-4RA, IL-18-R1, CXCL11, 9 and 10, CD163 and ACE2 were consistently elevated across all responder groups with ongoing LFT abnormality. No statistically significant differences occurred between markers in normal LFT groups stratified by bilirubin level.

Interpretation

This study provides evidence that any ongoing elevation in alkaline phosphatase levels in PBC after UDCA therapy is associated with some degree of ongoing disease activity. There was no difference in activity between patients with normal LFT when stratified by bilirubin. These findings suggest that if our goal is to completely control disease activity in PBC, then normalisation of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin should be the treatment target. This would also simplify messaging around goals of therapy in PBC, benefiting both patients and clinicians.

Funding

Funding by the UK Medical Research Council (Stratified Medicine Programme) and an independent research grant by Pfizer. The study funders played no role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation or manuscript writing.

Key words: Primary biliary cholangitis, Ursodeoxycholic acid, UDCA, Response criteria, Paris 1 criteria, Paris 2 criteria, POISE criteria, Normal LFT, High-risk disease, Proteomics, Alkaline phosphatase, Stratified medicine

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA) has entered widespread clinical use in Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) with high quality evidence showing that it improves survival and reduces the need for liver transplantation. A number of cohort studies have suggested, however, that a statistically significant proportion of PBC patients respond only partially to UDCA (conventionally termed “UDCA non-responders”, although in reality complete non-response is rare), and the majority of PBC patients progressing to liver transplant now do so despite UDCA therapy.

A number of therapies have been evaluated, or are currently under evaluation, aimed at improving disease control in UDCA non-responders and the use of such agents, such as obeticholic acid and bezafibrate, is now widespread. The challenge, however, is how to effectively identify UDCA non-responders in practice who might benefit from such second-line therapy.

There are a number of suggested clinical criteria for UDCA non-response (based around degrees of abnormality of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and alanine transaminase levels) described by different groups (Paris, Rotterdam, Toronto, Barcelona etc.). All are valid at a population level but at the level of the individual patient they can cause confusion, with the same patients potentially being deemed responders or non-responders depending on the choice of criteria chosen. There is evidence to suggest that this is confusing for both patients and clinicians and may contribute to sub-optimal use of stratified second-line therapy in practice. Guidelines in this regard are often unhelpful as they typically do not recommend use of a particular set of criteria. At present, there are no data to link any of these criteria to actual biological disease mechanisms and thus activity or severity.

Added value of this study

This study explores the relationship between the existing PBC response criteria and disease activity in terms of the serum inflammatory and metabolic proteome. This allows us to explore the implications of biochemical response criteria against actual disease activity, and give advice, based on objective evidence, as to which PBC UDCA response criteria are optimal for use in normal clinical practice.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study suggests that all the existing response criteria have a mechanistic underpinning, with disease activity being statistically significantly higher in non-responders than responders. There is, however, ongoing PBC disease activity in all “UDCA responder” groups, irrespective of the criteria used, apart from in patients with normal liver blood tests. Logically, therefore, normalisation of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin should become the goals of treatment. The higher the cut-off for biochemical tests used to define non-response, the greater the degree of disease inflammatory/immune/metabolic activity seen. This means that in current clinical practice, despite applying the most stringent response criteria, there will remain a proportion of patients labelled as “UDCA responders” who continue to have on-going disease activity with the potential for silent disease progression. The categorisation of patients based on response criteria, as opposed to normal liver function tests, potentially results in under-use of second-line therapy and increased adverse outcomes. The Global PBC Study Group suggested that using a threshold for bilirubin values of 0.6 times the upper limit of normal was necessary to see optimal control of disease activity but this is not supported by the data presented here.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Stratified therapy has now entered routine clinical practice in the chronic cholestatic liver disease, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).1, 2, 3 Treatment decisions regarding the need for additional therapy are made based on the serum biochemical response to primary therapy with the hydrophilic bile acid, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). All major guidelines at present recommend this approach,1, 2, 3 but typically do not advise which criteria to use for defining non-response. Therefore, the question, what is the optimal criteria for determining response to UDCA, and thus need for second-line therapy, remains both complex and confusing for clinicians and patients.

At present, all UDCA response criteria are based on cut-offs of the degree of elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin and, in some criteria, alanine transaminase (ALT). All accurately predict, at a population level, the risk of progression to death or transplant.4, 5, 6 At the individual patient level, however, the existence of a number of criteria sets can cause confusion, with patients being deemed a responder by some criteria and not by others. This may have contributed to the lack of understanding, on behalf of both clinicians and patients, regarding optimal management of PBC.7,8 All the current UDCA response criteria also accept some degree of ongoing liver blood biochemistry abnormality (typically of alkaline phosphatase) in “responding” patients. Recently, the Global PBC Study Group proposed that the biochemical cut-off for UDCA response should be the upper limit of normal (ULN) for alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin, or even 0.6 times the ULN of bilirubin together with a normal alkaline phosphatase, as any degree of ongoing liver biochemistry abnormality is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes.9

All the current UDCA response criteria were derived, and then validated, based on clinical outcomes, in large cohorts of patients under long-term follow-up. There has been no exploration, however, of how they link to the pathogenesis of PBC or the biology of high-risk disease (i.e. the organic basis of response and non-response states). The UK-PBC consortium recently reported a panel of 19 serum markers, identified using discovery proteomics, that remain elevated following UDCA treatment and that are plausibly linked to disease pathogenesis.10

In the current study, we set out to explore the expression of these markers in a large cohort of UK-PBC patients stratified by different UDCA response criteria status in order to better understand the mechanistic relevance of the different clinical response criteria and to help guide clinicians in how best to identify high-risk patients in clinical practice.

Methods

Study design & subjects

The aim of the study was to explore the serum proteome of UDCA-treated PBC patients from the UK-PBC study cohort, categorised by their UDCA response status, in order to inform our understanding of the biological basis of UDCA response and non-response. The UK-PBC Cohort (www.UK-PBC.com) was established to undertake studies of treatment efficacy in PBC to understand, in particular, the biological basis of high-risk disease. The details of the UK-PBC patient cohort have been described in detail previously.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 It is a large, prospective, national cross-sectional cohort of PBC patients with detailed clinical data collection. Within the cohort is a nested sub-cohort, termed the UK-PBC Nested Cohort, with additional bio-fluid sampling and banking to accompany the clinical data collection.18 This nested cohort of prevalent, fully-phenotyped PBC patients was designed to characterize the cellular and molecular response in PBC, facilitate the development of second-line therapies and biomarkers for more accurate stratification of treatment response and disease progression (MREC ref 07/H0606/96, REC ref 14/NW/1146). Recruitment was undertaken in 18 research centres, over a fixed 5 years from 2014 to 2019, with participants recruited into 1 of 6 sub-groups. The study reported here only included participants recruited to the first sub-group (cohort A; patients with a diagnosis of PBC who were receiving treatment with therapeutic dose UDCA (13–15 mg/kg/day) for greater than 12 months). All PBC diagnoses were made using the standard disease criteria used in clinical practice, namely the presence of at least two out of the three key PBC characteristics of: cholestatic liver biochemistry, positive serum anti-mitochondrial or PBC-specific anti-nuclear antibodies (at a titre of >1 in 40) and compatible or diagnostic features on liver biopsy.2 Patients had to be able to provide informed consent to be recruited to the UK-PBC nested Cohort A study. Participants with pre-PBC (AMA positive in the context of normal liver biochemistry) or clinically diagnosed PBC/autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromes were excluded. Patients were not selected on the basis of the presence or absence of co-morbidities. The sample size for this study was determined by the number of participants recruited to the UK-PBC Nested Cohort during the defined study period for whom full clinical data and serum samples were available. There were no missing data. No formal sample size calculation was undertaken given the exploratory nature of the study meaning that no data about inflammatory markers in PBC defined by UDCA response status exist to inform such a calculation. The serum markers used in this study, were previously identified and validated by the UK-PBC consortium as being elevated in patients with PBC, but not healthy controls (Table 1).10 As this study explores UDCA response in PBC, no healthy controls were included.

Table 1.

Markers Explored: All markers explored were identified in the underpinning UK-PBC study as remaining elevated in UDCA treated PBC patients compared to healthy controls.10

| Family | Abbreviation | Identity |

|---|---|---|

|

Chemokines |

CXCL9 | Chemokine CXCL9 |

| CXCL10 | Chemokine CXCL10 | |

| CXCL11 | Chemokine CXCL11 | |

| CXCL13 | Chemokine CXCL13 | |

| CCL19 | Chemokine CCL19 | |

| CCL20 | Chemokine CCL20 | |

|

Cytokine Modulators |

IL-4RA | IL-4 Receptor Alpha Chain |

| IL-18R1 | IL-18 Receptor 1 | |

|

Cell Surface & Structural Proteins |

EpCam | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| CD163 | High Affinity Scavenger Receptor | |

| VIM | Vimentin | |

| KIM1 | Kidney Injury Molecule 1 | |

| SCAMP3 | Secretory Carrier-Associated Membrane Protein 3 | |

| Metabolic Factors | HAOX1 | Human Aldehyde Oxidase |

| LEP | Leptin | |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 | |

| CA5A | Carbonic Anhydrase 5A | |

| DECR1 | 2,4-Dienoyl-CoA Reductase 1 | |

| AZU1 | Azurocidin (Heparin Binding Protein) | |

UDCA treatment and response criteria

All participants were, as a study entry requirement, taking UDCA at a therapeutic dose (13–15 mg/kg/day) for greater than 12 months at the time of recruitment. Clinical parameters, including serum biochemistry, were available both pre-treatment and at the time of study entry. This enabled all UDCA-treated patients to be grouped by their response to therapy using well-defined criteria. The following established response criteria were explored in the study:

Paris 1 Criteria: Response is defined as all three of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) <3x upper limit of normal (ULN), alanine transaminase (ALT) <2x ULN and bilirubin <ULN19

POISE Criteria: Defined as ALP <1.67x ULN and bilirubin <ULN20

Paris 2 Criteria: Response defined as both ALP <1.5x ULN and ALT <1.5x ULN21

In addition, we explored the biological correlates of the following states

Normal liver function tests (LFT): Defined as ALP <ULN and bilirubin <ULN

Low bilirubin Normal LFT: defined as ALP <1.0x ULN and bilirubin <0.6x ULN (criteria recently proposed by the Global PBC Study Group).9

For each of these response criteria, each participant was given a response status (“responder” if they met the criteria and “non-responder” if they didn't) (Supplementary Figure 1). Given the progressive, incremental increase in the cut-off values for defining response (with Paris 1 having the highest cut-offs, normal LFT with a bilirubin <0.6x ULN having the lowest), component sub-groups for each of the responder/non-responder pairings can also be identified. For example, the Paris 2 responder group includes some patients who have normal liver function tests (i.e. normal LFT responders) and some who have abnormal liver functions (i.e. normal LFT non-responders but with values below the Paris 2 cut-offs). Using the response criteria detailed above, participants were stratified into 1 of 6 such component sub-groupings (Supplementary Figure 1) based on their alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin values:

-

1.

Paris 1 non-responders (ALP > 3x ULN or bil>1.0xuln)

-

2.

POISE non-responders but Paris 1 responders (ALP > 1.67x ULN but < 3x ULN and bil<1.0xuln)

-

3.

Paris 2 non-responders but POISE responders (ALP > 1.5x ULN but <1.67x ULN and bil<1.0xuln)

-

4.

Paris 2 responders with ongoing LFT abnormality (ALP >1x ULN but <1.5x ULN and bil<1.0xuln)

-

5.

Normal LFT (ALP <1x ULN and Bilirubin >0.6 but <1.0x ULN)

-

6.

Low bilirubin, normal LFT (ALP <1x ULN and Bilirubin <0.6x ULN).

Methods

Proteins were measured using the Olink® Target 96 Cardiovascular II & III, Inflammation and Oncology II panels (Olink Proteomics AB, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Proximity Extension Assay (PEA) technology used for the Olink protocol has been well described,22 and enables 92 analytes to be analysed simultaneously, using 1 µL of each sample. 4µL of serum was analysed for 368 analytes in this study (RRID:SCR_003899). Pairs of oligonucleotide-labelled antibody probes bind to their targeted protein, and if the two probes are brought in close proximity the oligonucleotides will hybridize in a pair-wise manner. The addition of a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) polymerase leads to a proximity-dependant DNA polymerization event, generating a unique polymerase chain reaction (PCR) target sequence. The resulting DNA sequence is subsequently detected and quantified using a microfluidic real-time PCR instrument (Biomark HD, Fluidigm). The resulting CT-data is then quality controlled and normalized using a set of internal and external controls. The final assay read-out is presented in Normalized Protein eXpression (NPX) values, which is an arbitrary unit on a log2-scale where a high value corresponds to a higher protein expression. The internal controls are designed to mimic and monitor the different steps of the PEA. They consist of two incubation/immuno controls, an extension control and a detection control. The internal controls are introduced to all samples as well as to the external controls and are used for quality control and normalization of the data. The external controls consist of a negative control used to calculate the limit of detection (LOD), as well as a triplicate of interplate controls (IPCs) that are used for data normalization. Quality control of the data is performed in two steps. Firstly, the run is quality controlled by calculating the standard deviation for the detection control and the incubation/immuno controls. The standard deviation should be below 0.2 for a run to pass quality control. Secondly, each sample is quality controlled by comparing the results for the detection control and one of the incubation controls against the run median. Samples that fall more than 0.3 NPX from the run median with regards to these two internal controls will fail the quality control. All assay validation data (detection limits, intra- and inter-assay precision data, etc.) are available on the manufacturer's website (www.olink.com).

Ethics

Blood was collected under the approval of the Human Tissue Authority (HTA) by the UK-PBC tissue Bioresource with written informed patient consent obtained in accordance with research and ethics committee (REC) approval (14/NW/1146).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using Graphpad Prism, version 9. Trends across groupings were assessed using 1-way ANOVA analysis. Inter-group comparisons of specific markers were done using parametric t tests. P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Point estimates and confidence intervals are provided for all comparisons. Complete data was available for all subjects.

Role of the funding source

The study was funded by a research grant from the UK Medical Research Council (Stratified Medicine Programme) and an independent research grant by Pfizer. The study funders played no role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation or manuscript writing.

Results

The clinical details of the study population (400 UK-PBC Nested Cohort members for which all relevant clinical information were available) are summarised in Table 2. The results are in keeping with the stringency of the various response criteria, with 347 patients in the Paris 1 responder group (165 with ongoing LFT abnormality and 182 with normal LFT) as compared with 274 in the Paris 2 responder group (92 with ongoing LFT abnormality and 182 with normal LFT).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the study population.

| UDCA-Treated PBC | |

|---|---|

| (n = 400) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 64.4 (55.7–70.8) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 356 (89) |

| Cirrhotic, n (%) | 26(7) |

| UDCA Treatment at therapeutic dose, n (%) | 400 (100) |

| Mean number of prescribed medications per patient (other than UDCA) | 3.8 |

| Mean number of co-morbidities per patient (excluding osteoporosis) | 2.4 |

| Ethnicity white british or irish, n (%) | 393 (98) |

| ALP at 1 year, median (IQR) | 138 (101–222) |

| ALT at 1 year, median (IQR) | 28(19–45) |

| Bilirubin at 1 year, median (IQR) | 9(7–12) |

| Normal LFT with bilirubin ≤0.6x ULN, n (%) | 160 (40) |

| Normal LFT, n (%) | 182 (46) |

| Paris 2 Responder with on-going LFT Elevation, n (%) | 92(23) |

| POISE Responder with on-going LFT Elevation, n (%) | 107(27) |

| Paris 1 Responder with on-going LFT Elevation, n (%) | 165 (41) |

| Paris 1 non-responders, n (%) | 53(13) |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase, ALT: alanine transaminase, LFT: Liver function Tests, IQR: interquartile range.

Initially, we explored the biological pattern, for the 3 UDCA response criteria used in clinical practice that all still accept some ongoing LFT abnormality (Paris 2 [the lowest cut-offs], POISE [intermediate] and Paris I [the highest cut-off values]), of the 19 key serum protein markers (Table 1) identified in the UK-PBC proteomics study as being elevated in PBC (compared to healthy controls) despite UDCA therapy (Table 3). For each of the response criteria a statistically significant pattern of elevated marker expression was seen in the non-responders compared to the responders. VIM was the only marker that did not show any statistically significant difference between responders and non-responders irrespective of the criteria used. Leptin was the only marker that was statistically significantly higher in responders than non-responders for all criteria studied. All the other markers showed statistically significantly lower values in responders than non-responders for the most stringent of the pre-existing criteria (Paris 2 that identifies the most non-responders). When using the least stringent criteria (Paris 1 that identifies the least non-responders), CXCL9, CXCL13 and AZU1 were no longer statistically significantly different between responders and non-responders.

Table 3.

Markers values in UDCA responders and non-responders for a) Paris 2 response criteria, b) POISE response criteria and c) Paris 1 response criteria.

| a) Paris 2 Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | *Responder pg/ml (n = 274) | *Non-Responder pg/ml (n = 126) | Point Estimate | CI for PE R v Non-R | **p |

| CXCL9 | 8.9 (0.9) | 9.4 (0.9) | 0.51 | 0.32–0.70 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL10 | 9.0 (0.8) | 9.5 (0.8) | 0.57 | 0.40–0.75 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL11 | 9.0 (0.8) | 9.6 (1.0) | 0.64 | 0.46–0.81 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL13 | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) | 0.22 | 0.11–0.35 | 0.0006 |

| CCL20 | 5.5 (1.2) | 6.1 (1.1) | 0.61 | 0.36–0.85 | <0.0001 |

| CCL19 | 9.8 90.9) | 10.4 (0.9) | 0.57 | 0.38–0.76 | <0.0001 |

| IL-4RA | 2.9 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.8) | 1.15 | 1.02–1.29 | <0.0001 |

| IL-18R1 | 7.4 (0.5) | 8.3 (0.6) | 0.84 | 0.73–0.98 | <0.0001 |

| EpCam | 4.9 (0.6) | 5.3 (0.6) | 0.40 | 0.27–0.52 | <0.0001 |

| CD163 | 8.1 (0.5) | 8.6 (0.5) | 0.48 | 0.37–0.59 | <0.0001 |

| VIM | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.7) | −0.07 | −0.22–0.07 | 0.31 |

| KIM1 | 8.2 (0.8 | 9.2 (0.9) | 0.92 | 0.74–1.1 | <0.0001 |

| SCAMP3 | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.0) | 0.25 | 0.04–0.44 | 0.016 |

| HAOX1 | 5.2 (1.5) | 7.2 (1.4) | 2.0 | 1.72–2.32 | <0.0001 |

| LEP | 6.6 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.2) | −0.54 | −0.77—0.30 | <0.0001 |

| ACE2 | 4.4 (0.9) | 5.6 (1.0) | 1.21 | 1.00–1.41 | <0.0001 |

| CA5A | 3.5 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.1) | 1.21 | 0.95–1.40 | <0.0001 |

| DECR1 | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.8 (0.9) | 0.74 | 0.57–0.90 | <0.0001 |

| AZU1 | 6.5 (1.4) | 6.3 (1.1) | −0.26 | −0.5—0.02 | 0.031 |

| b) POISE Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | *Responder pg/ml (n = 289) | *Non-Responder pg/ml (n = 111) | Point Estimate | CI for PE R v Non-R | **p |

| CXCL9 | 8.9 (0.8) | 9.3 (0.9) | 0.35 | 0.17–0.54 | 0.0002 |

| CXCL10 | 9.0 (0.8) | 9.4 (0.8) | 0.47 | 0.30–0.65 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL11 | 9.0 (0.8) | 9.5 (1.1) | 0.48 | 0.29–0.67 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL13 | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) | 0.20 | 0.07–0.33 | 0.0029 |

| CCL20 | 5.5 (1.2) | 6.1 (1.1) | 0.55 | 0.30–0.80 | <0.0001 |

| CCL19 | 9.8 (0.9) | 10.3 (0.9) | 0.48 | 0.29–0.67 | <0.0001 |

| IL-4RA | 2.9 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.8) | 1.17 | 1.00–1.31 | <0.0001 |

| IL-18R1 | 7.4 (0.5) | 8.3 (0.6) | 0.83 | 0.71–0.95 | <0.0001 |

| EpCam | 4.9 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.6) | 0.44 | 0.31–0.56 | <0.0001 |

| CD163 | 8.1 (0.5) | 8.6 (0.5) | 0.49 | 0.38–0.6 | <0.0001 |

| VIM | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.4 (0.7) | −0.11 | −0.27–0.04 | 0.14 |

| KIM1 | 8.3 (0.8) | 9.2 (0.9) | 0.93 | 0.75–1.11 | <0.0001 |

| SCAMP3 | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.0) | 0.15 | −0.05–0.35 | 0.16 |

| HAOX1 | 5.3 (1.6) | 7.1 (1.4) | 1.76 | 1.42–2.11 | <0.0001 |

| LEP | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.2) | −0.54 | −0.78—0.30 | <0.0001 |

| ACE2 | 4.4 (0.9) | 5.5 (1.1) | 1.15 | 0.95–1.36 | <0.0001 |

| CA5A | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.0) | 0.93 | 0.69–1.21 | <0.0001 |

| DECR1 | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.9) | 0.50 | 0.33–0.69 | <0.0001 |

| AZU1 | 6.6 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.2) | −0.44 | −0.68- −0.20 | 0.0003 |

| c) Paris 1 Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Responder pg/ml (n = 347) | Non-Responder pg/ml (n = 53) | Point Estimate | CI for PE R v Non-R | P |

| CXCL9 | 9.0 (0.9) | 9.2 (1.1) | 0.27 | −0.01–0.47 | 0.065 |

| CXCL10 | 9.1 (0.9) | 9.6 (0.9) | 0.49 | 0.27–0.700 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL11 | 9.1 (0.9) | 9.7 (1.0) | 0.64 | 0.41–0.88] | <0.0001 |

| CXCL13 | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.7) | 0.13 | −0.04–0.29 | 0.13 |

| CCL20 | 5.6 (1.2) | 6.2 (1.3) | 0.60 | 0.28–0.91 | 0.0002 |

| CCL19 | 9.9 (1.0) | 10.3 (0.9) | 0.38 | 0.13–0.63 | 0.0033 |

| IL-4RA | 3.1 (0.7) | 4.3 (1.0) | 1.18 | 0.98–1.37 | <0.0001 |

| IL-18R1 | 7.6 (0.6) | 8.4 (0.8) | 0.81 | 0.65–0.97 | <0.0001 |

| EpCam | 5.0 (0.6) | 5.4 (0.7) | 0.38 | 0.22–0.54 | <0.0001 |

| CD163 | 8.1 (0.5) | 8.6 (0.6) | 0.47 | 0.33–0.61 | <0.0001 |

| VIM | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.7) | −0.01 | 0.21–0.18 | 0.88 |

| KIM1 | 8.4 (0.9) | 9.3 (1.1) | 0.88 | 0.64–1.1 | <0.0001 |

| SCAMP3 | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.1) | 0.36 | 0.10–0.62 | 0.0013 |

| HAOX1 | 5.5 (1.6) | 7.6 (1.4) | 2.0 | 1.6–2.4 | <0.0001 |

| LEP | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.1 (112) | −0.36 | −0.66—0.05 | 0.020 |

| ACE2 | 4.6 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.1) | 1.01 | 0.72–1.3 | <0.0001 |

| CA5A | 3.8 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.3) | 1.10 | 0.85–1.50 | <0.0001 |

| DECR1 | 4.2 (0.8) | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.84 | 0.62–1.1 | <0.0001 |

| AZU1 | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.3) | −0.30 | −0.61–0.0 | 0.053 |

*mean pg/ml (standard deviation); ** Independent samples t -test.

We next went on to compare the group of patients with normal LFT after UDCA treatment with those defined as responders by each of the pre-existing criteria (Paris 2, POISE and Paris 1), but who had ongoing LFT abnormality (Table 4). Of the 19 markers, 9 were statistically significantly lower in those with normal LFT compared to Paris 2 responders with abnormal LFT (Paris 2 being the most stringent of the pre-existing criteria, identifying the most non-responders) and POISE responders with abnormal LFT. For normal LFT compared to Paris 1 responders with abnormal LFT, 14 were statistically significantly different between the 2 groups. Leptin was statistically significantly lower in patients with normal LFT compared to all the pre-existing criteria with ongoing LFT abnormality. Seven markers (IL-4RA, IL-18-R1, CXCL11, CXCL9, CXCL10, ACE2 and CD163) were consistently statistically significantly elevated across all responder groups with ongoing LFT abnormality as compared to those with normal LFT.

Table 4.

Proteomics Markers in Responders with Ongoing LFT Abnormality below the Non-Response Threshold for Paris 2, POISE and Paris 2 Criteria Compared to the Normal LFT Group (Green cells denote statistically significant difference between those with normal LFT and the pre-existing criteria groups with ongoing LFT abnormality. Red cells denote no statistically significant difference as compared to those with normal LFT).

|

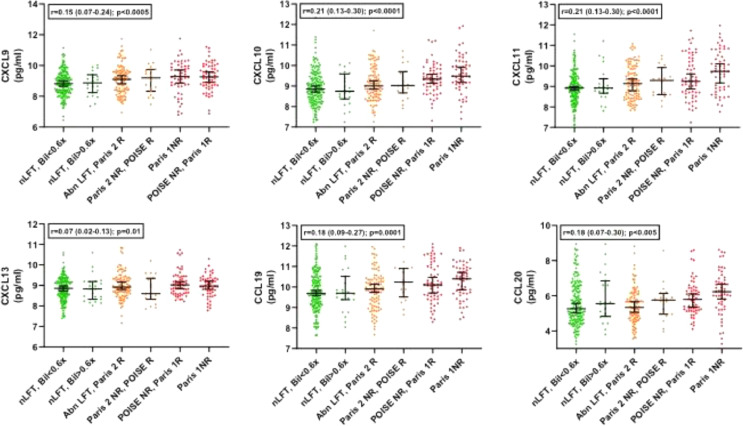

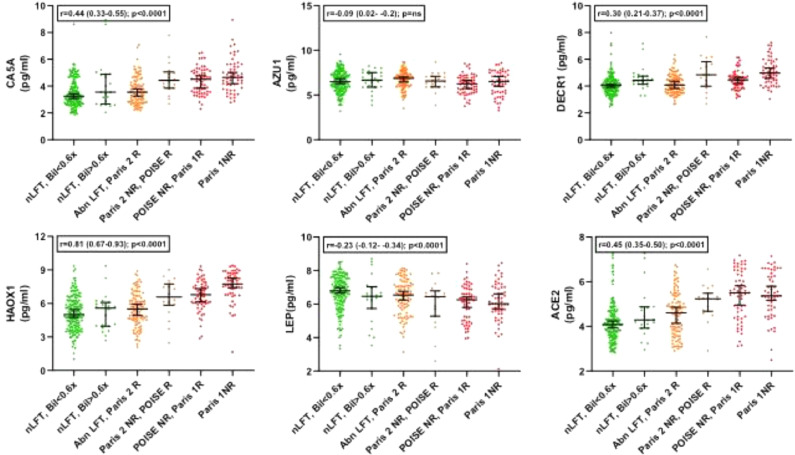

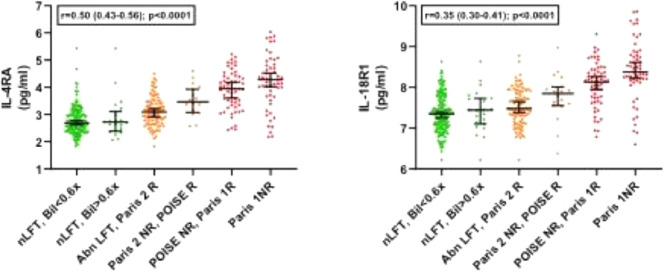

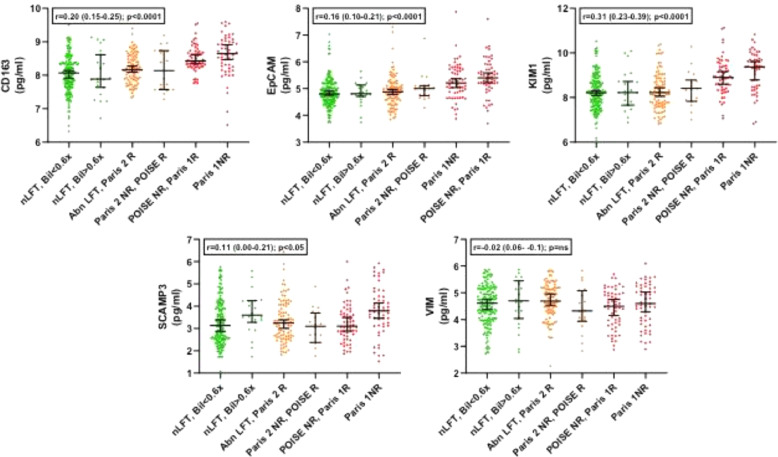

We next then explored for trends across the whole spectrum of biochemical values in the PBC groups, exploring the 6 marginal sub-groups that go to make up the clinical responder/non-responder groups for each of the criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). These sub-groups range from the most stringent criteria (ALP <ULN & Bilirubin <0.6x ULN) to the least stringent criteria (Paris 1 non-responders; ALP >x3 ULN). For 17 of the 19 protein markers, there was a statistically significant change as the stringency of UDCA-response cut-offs reduced (16 with progressive increase and 1, leptin, with progressive decrease; Table 5). Only VIM and AZU1 were not statistically significantly different. Figures 1–4 show the values for the individual serum proteomic markers for the 6 groupings, split by proteomics family type: chemokines (Figure 1), cytokine modulators (Figure 2), cell surface/structural proteins (Figure 3) and metabolic factors (Figure 4).

Table 5.

Marker levels Values Across the Responder and Non-Responder Component Sub-Groups. The component sub-groups (Supplementary Figure 1) across which the marker value trend was explored were a) ALP ≤1x ULN & Bil ≤0.6x ULN; b) ALP ≤1x ULN & Bil ≥0.6 ≤ 1.0x ULN; c) Paris 2 responders with ALP ≥1x ULN but ≤1.5x ULN; d) Paris 2 non-responders but POISE responders; ≥1.5x ULN to ≤1.67x ULN e) POISE non-responders but Paris 1 responders; ≥1.67x ULN to ≤3x ULN f) Paris 1 non-responders; ≥ 3x ULN.

| Family | Marker | Anova p value | Trend slope across the groups R (95% CI) | Trend slope P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines | CXCL9 | 7.7 × 10−3 | 0.21 (0.13–0.27) | 0.0002 |

| CXCL10 | 2.5 × 10−5 | 0.21 (0.13–0.27) | ≤0.0001 | |

| CXCL11 | 1.7 × 10−6 | 0.25 (0.17–0.34) | ≤0.0001 | |

| CXCL13 | 2.8 × 10−2 | 0.07 (0.02–0.13) | 0.011 | |

| CCL20 | 1.0 × 10−1 | 0.18 (0.07–0.30) | 0.0078 | |

| CCL19 | 2.0 × 10−3 | 0.18 (0.09–0.26) | ≤0.0001 | |

| Cytokine Modulators | IL-4RA | <1.0 × 10−16 | 0.50 (0.43–0.56) | ≤0.0001 |

| IL-18R1 | <1.0 × 10−16 | 0.35 (0.30–0.40) | ≤0.0001 | |

| Cell Surface & Structural Proteins | EpCam | 6.3 × 10−8 | 0.16 (0.10–0.22) | ≤0.0001 |

| CD163 | 8.2 × 10−12 | 0.20 (0.14–0.26) | ≤0.0001 | |

| VIM | 2.3 × 10−1 | −0.02 (−0.09–0.05 | 0.39 | |

| KIM1 | 3.4 × 10−12 | 0.31 (0.23–0.39) | ≤0.0001 | |

| SCAMP3 | 4.2 × 10−3 | 0.11 (0–0.21) | 0.15 | |

| Metabolic Factors | HAOX1 | <1.0 × 10−16 | 0.81 (0.67–0.93) | ≤0.0001 |

| LEP | 2.7 × 10−4 | −0.23 (−34—13) | ≤0.0001 | |

| ACE2 | <1.0 × 10−16 | 0.45 (0.35–0.50) | ≤0.0001 | |

| CA5A | 3.2 × 10−12 | 0.44 (0.33–0.55) | ≤0.0001 | |

| DECR1 | 3.47×10−13 | 0.29 (0.21–0.37) | ≤0.0001 | |

| AZU1 | 1.7 × 10−1 | −0.09 (−0.02–0.02) | 0.09 |

Figure 1.

Marker levels across the study groups for the chemokine group (1-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Marker levels across the study groups for the metabolic factor group (1-way ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Marker levels across the study groups for the cytokine modulator group (1-way ANOVA).

Figure 3.

Marker levels across the study groups for the cell surface/structural proteins group (1-way ANOVA).

Finally, we compared the more stringent proposed Global PBC Study Group criteria (bilirubin <0.6x ULN and normal ALP) with normal LFT to explore whether there was a difference in marker profile between patients who did and didn't meet this additional bilirubin criterion (Table 6). We found that 3 of the markers (SCAMP3, ACE2 and CA5A) showed a marginal difference between the two normal LFT sub-groups. Importantly, of the 182 normal LFT subjects in the study, the majority 160 (88%) had bilirubin levels below 0.6x ULN leaving only 22 patients in the group with normal ALP with bilirubin between 0.6–1x ULN for analysis. SCAMP3 and CA5A were not identified in any of the analyses comparing the ‘diseased’ state to normal LFT, which could suggest these are unlikely to be biologically relevant in PBC.

Table 6.

Comparison of proteomic markers between participants with normal LFTs according to bilirubin (bilirubin ≤0.6xuln versus bilirubin 0.6–1.0x upper limit of normal). Green bars denote statistically significant difference.

|

Discussion

Stratified medicine, in the form of second-line therapy used selectively in patients showing an inadequate response to first-line treatment with UDCA, has entered widespread clinical practice in PBC and is recommended in all major clinical practice guidelines. There are, however, limitations with this treatment model in practice. There is confusion amongst both patients and clinicians regarding the approach and its uptake in practice has only reached a small percentage of all potentially eligible patients. One of the recurring areas of confusion is in relation to the multiple versions of UDCA response criteria that exist without clear guidance from clinical guidelines as to which, if any, is optimal. All the criteria are, at a population level, effective in identifying groups with an elevated risk of death or need for liver transplantation and are thus “valid”. At the individual patient level, however, it is not uncommon to encounter individuals who are identified as a responder by some criteria and a non-responder by others. This can be a real source of confusion to clinicians. Furthermore, all are based on cut-offs of multiples of the upper limit of normal of key peripheral biochemical markers. Although evidence-based in terms of population predictive values, these cut-offs can appear arbitrary and counter-intuitive, especially in patients who are at the boundaries for values between “high” and “low” risk groups. Our experience is that this has contributed significantly to clinician scepticism in relation to stratified therapy in PBC and plays a part in the low uptake of accessing second-line therapy in practice. We are not aware of any published studies to directly compare risk-stratified groups (by the various UDCA response criteria) in terms of the disease biology or to understand the biological basis of these clinical cut-offs.

The UK-PBC project was established to study the biological basis of risk in PBC. In the current study, we have used data from the UK-PBC proteomics study patients on stable therapeutic dose UDCA therapy for at least 1 year with detailed clinical response data. We have previously described the underpinning observation of a highly significant and consistent profile of inflammatory proteins that, although reduced, remain elevated in PBC patients following UDCA treatment. Here, we explore the impact of the various UDCA response states on this UDCA-treated PBC proteome. We believe the findings will help to clarify how we should assess UDCA response in clinical practice in the future.

Our first finding was that for all the established UDCA criteria, there was markedly higher expression of the putative mechanistic markers in non-responders compared to responders (with the exception of leptin that was lower in responders than non-responders). This adds further evidence to the validity of these clinical markers of therapy response by linking clinical with mechanistic sensitivity. There was a progressive increase (other than in the case of leptin where there was a progressive decrease) from the Paris 2 responder only group (the most stringent criteria with the largest number of non-responders) through to the Paris 1 non-responder group (the least stringent that identifies the fewest non-responders). This suggests that the more abnormal the liver biochemistry is, the more marked the degree of mechanistic activity. This, again, adds evidence in support of the value of biochemical markers in PBC such as alkaline phosphatase where there is a linear relationship between biochemical value and disease outcome.4

Our second key finding was that for each of the responder groups according to the currently existing criteria there was ongoing elevation of disease markers in the sub-group with persisting liver blood test abnormality but at levels below the relevant response criteria threshold compared to those with normal LFT. This included the Paris 2 criteria, suggesting that even minimal elevation of LFTs is associated with residual disease activity. This finding challenges the concept of using any of the existing criteria to identify patients with on-going disease activity, suggesting that any degree of abnormality in alkaline phosphatase PBC is associated with ongoing disease activity and provides a mechanistic explanation for the findings of the Global PBC Study Group.9

In simple terms, our findings support the view that complete control of PBC requires normal liver biochemistry. The parallel with the evolution of our understanding about the target for liver biochemistry in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is striking. It is now widely accepted in AIH that any degree of liver biochemical abnormality is associated with ongoing liver inflammation, increased risk of fibrosis and poorer clinical outcomes.23

Seven markers (IL-4RA, IL-18-R1, CXCL11, CXCL9, CXCL10, ACE2 and CD163) remained statistically significantly elevated in the presence of ongoing LFT abnormality regardless of which response criteria were used. CXCL11, along with CXCL9 and CXCL10, is a CXCR3 receptor agonist that drives recruitment of Th1 cells at the site of hepatic inflammation and has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of PBC as well as other chronic liver disease.24, 25, 26 The persistent elevation of IL-18R1 in the context of ongoing LFT abnormality may be explained by its role as an IL-18 binding receptor, predominately located on Th1 cells, which are activated by both IL-18 and IL-12 to stimulate Th1 mediated responses.27 Similarly the accumulation of mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, which also express high levels of IL-18R1, have been previously identified in the bile ducts of patients with PBC.28 In addition, both IL-18R1 and IL-4RA have been identified in a meta-analysis as potential functional annotations of risk loci associated with PBC.29 ACE2 expression and ACE2 enzyme activity have previously been shown to be significantly elevated following bile duct ligation in rats (increasing with worsening fibrosis) and human cirrhotic livers secondary to chronic hepatitis C (CHC).30,31 We are not aware of previous data showing a link between ACE2 and PBC but this is an area that may warrant further research given the link between ACE and sarcoidosis, another granulomatous disease.32 CD163 is a macrophage scavenger receptor. A recent Italian study also showed elevation in more severe PBC, validating our finding.33

The focus of the current study was the clinical implications of the proteomic markers in terms of understanding the meaning and value of UDCA response criteria. It is possible that individual groups of markers may have further value as specific disease activity markers. Further study, with evaluation in further cohorts will be necessary to address this question, although our previous study did suggest potential value for a composite marker based on chemokine levels.10 The consistency across studies around CD163 also suggests potential clinical value for this marker.

A further obvious question is whether any of these molecules may offer a therapeutic target to treat enhanced risk disease. This will, again, require, further work. One of the molecules has, however, already been explored. Blockade of CXCL10 was clinically ineffective in improving UDCA non-responsive PBC.34 Whether this negative outcome reflected redundancy of the chemokine network in PBC (blocking a single chemokine might be expected to be ineffective when multiple other chemokines, also elevated in PBC, bind to the same receptor) or under-dosing isn't clear.

In this study, leptin was the only marker that decreased with worsening degrees of biochemistry. Low levels of serum leptin have been reported in PBC patients but the relationship between liver function tests and histological staging remains unclear.35,36 Elevated serum leptin has also been described in patients with CHC and significant fatigue.37 Fatigue remains a significant problem for many patients with PBC for which there is no effective therapy and is not related to disease severity.38 Further work to explore the relationship between leptin and fatigue is warranted.

Our final observation is that there is no evidence from our data set to suggest a difference in mechanistic activity between normal LFT patients with bilirubin values above and below the Global PBC Study Group's suggested threshold of bilirubin 0.6x the upper limit of normal. This may suggest that based on the data from this study, we should be aiming for ‘normal’ but we don't need to go beyond that into supra-normal as a clinical target. An important caveat this, however, is that the vast majority of the normal LFT group fell into the lower band with bilirubin <0.6x ULN.

The study has important limitations that need to be considered. Although the cohort is a contemporary one, and thus relevant to PBC as seen in the clinic today, it was cross-sectional in nature. Linear studies, with patients being sampled prior to and following therapy will be important in the future. There were also no exclusion criteria in relation to co-morbidity so an impact of co-existent disease, either in the form of linked autoimmunity or un-linked age-related conditions cannot be excluded. The cohort was large for studies of this type in a rare disease, and the demographic characteristics reflect the broader UK PBC population, however, bias in terms of patient participation cannot be excluded. Finally, the proteomic markers evaluated have been validated but the original derivation study that identified them was limited to 368 analytes meaning that other significant markers not present in the panel will have been missed.

In conclusion, we believe that these findings will, despite the study limitations, help clarify the optimal approach to managing PBC patients in practice following first-line treatment with UDCA and assessment of liver biochemistry after 1 year of therapy. Both the clinical, and now mechanistic, data suggest that complete control of disease-associated risk requires the complete normalisation of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin. This should be the target for treatment in both clinical trials and normal practice. If response criteria are still to be used, with continued acceptance of a degree of ongoing LFT abnormality, then the more stringent the threshold the better in terms of disease control (i.e. Paris 2 is preferable to POISE that in turn is preferable to Paris 1). Our mechanistic approach would not support going below the conventional upper limit of normal for bilirubin. We believe, however, that a change in current clinical practice to normalisation of liver function tests as the clinical target would have the advantage of simplifying management, removing uncertainty around alternative response criteria and improve patient and clinician understanding (and thus acceptance) of the goals of treatment.

Contributors

David EJ Jones – conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualisation, writing original draft. Aaron Wetten – Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft. Ben Barron-Millar – Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Laura Ogle – Investigation, Writing – review & editing. George Mells – Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Steven Flack – Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Richard Sandford – Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. John Kirby – Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Jeremy Palmer – Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Sophie Brotherston – Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Laura Jopson – Resources, Writing – review & editing. John Brain – Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Graham R Smith – Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Steve Rushton – Formal Analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rebecca Jones – Resources, Writing – review & editing. Simon Rushbrook – Resources, Writing – review & editing. Douglas Thorburn – Resources, Writing – review & editing. Steve Ryder – Resources, Writing – review & editing. Gideon Hirschfield – Resources, Writing – review & editing. Jessica K Dyson – Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft.

All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing

All presented data available on request, pending approval of proposed use and signed data access agreement. Application for access to data to be made via corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

Professor David Jones has received lecture fees from Intercept, Abbot, Calliditas and GSK; consulted for Intercept, Falk, Abbot and Calliditas and received grant funding from Intercept

Dr Gideon Hirschfield has consulted for GSK, Cymabay, Genfit, HighTide, Pliant, Mirum and Roche.

Dr Jessica Dyson has received speaker fees from Dr Falk Pharma and Intercept.

The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Funding by the UK Medical Research Council (Stratified Medicine Programme) and an independent research grant by Pfizer. The funders played no role in the delivery of the study or the analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104068.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hirschfield G.M., Beuers U., Corpechot C., et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: the diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):145–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschfield G.M., Dyson J.K., Alexander G.J.M., et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:1568–1594. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindor K.D., Bowlus C.L., Boyer J., Levy C., Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018 doi: 10.1002/hep.30145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lammers W.J., van Buuren H.R., Hirschfield G.M., et al. Levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are surrogate endpoints of outcomes of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis - an international follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1338–1349. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone M., Mells G.F., Pells G., et al. Sex and age are determinants of the clinical phenotype of primary biliary cirrhosis and response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(3):560–569. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.005. e7; quiz e13-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trivedi P.J., Corpechot C., Pares A., Hirschfield G.M. Risk stratification in autoimmune cholestatic liver diseases: opportunities for clinicians and trialists. Hepatology. 2016;63:644–659. doi: 10.1002/hep.28128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jopson L., Khanna A., Peterson P., Rudell E., Corrigan M., Jones D.J. Are clinicians ready for safe use of stratified therapy in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)? A study of educational awareness. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2547–2554. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leighton J., Thain C., Mitchell-Thain R., Jones D.E.J. Patient ownership of primary biliary cholangitis long term management. Frontline Gastro. 2020 doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101324. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murillo Perez C.F., Harms M.H., Lindor K.D., et al. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1066–1074. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barron-Millar B., Ogle L., Mells G., et al. The serum proteome and ursodeoxycholic acid response in primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatology. 2021 doi: 10.1002/hep.32011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mells G.F., Floyd J.A., Morley K.I., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 12 new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2011;43(4):329–332. doi: 10.1038/ng.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbone M., Mells G., Pells G., et al. Sex and age are determinants of the clinical phenotype of primary biliary cirrhosis and response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastorenterology. 2013;144:560–569. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pells G., Mells G.F., Carbone M., et al. The impact of liver transplantation on the phenotype of primary biliary cirrhosis patients in the UK-PBC cohort. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mells G.F., Pells G., Newton J.L., et al. Impact of primary biliary cirrhosis on perceived quality of life: the UK-PBC national study. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):273–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.26365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbone M., Sharp S.J., Flack S., et al. The UK-PBC risk scores: derivation and validation of a scoring system for long-term prediction of end-stage liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;60:930–950. doi: 10.1002/hep.28017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyson J.K., Wilkinson N., Jopson L., et al. The inter-relationship of symptom severity and quality of life in 2055 patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1039–1050. doi: 10.1111/apt.13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carbone M., Nardi A., Flack S., et al. Early patient stratification to enable personalized management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Lancet Gastro Hep. 2018;3:626–634. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liaskou E., Patel S., Webb G., et al. Increased sensitivity of Treg cells from patients with PBC to low dose IL-12 drives their differentiation into IFN-γ secreting cells. J Autoimmun. 2018;94:13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corpechot C., Abenavoli L., Rabahi N., et al. Biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long-term prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:871–877. doi: 10.1002/hep.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nevens F., Andreone P., Mazzella G., et al. A placebo-controlled trial of obeticholic acid in primary biliary cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;373:631–643. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corpechot C., Chazouilleres O., Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long-term outcome. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1361–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assarsson E., Lundberg M., Holmquist G., et al. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones D.E.J., Manns M.P., Terracciano L., Torbenson M., Vierling J.M. Unmet needs and new models for future trials in autoimmune hepatitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:363–370. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi J., Selmi C., Leung P.S.C., Kenny T.P., Roskams T., Gershwin M.E. Chemokine and chemokine receptors in autoimmunity: the case of primary biliary cholangitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(6):661–672. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1147956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marra F., Tacke F. Roles for chemokines in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):571–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.043. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tacke F., Zimmermann H.W., Berres M.-.L., Trautwein C., Wasmuth H.E. Serum chemokine receptor CXCR3 ligands are associated with progression, organ dysfunction and complications of chronic liver diseases. Liver International. 2011;31(6):840–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi K., Yoshimoto T., Tsutsui H., Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19(1):423–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toubal A., Lehuen A. Lights on MAIT cells, a new immune player in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1008–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordell H.J., Han Y., Mells G.F., et al. International genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new primary biliary cirrhosis risk loci and targetable pathogenic pathways. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8019. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paizis G. Chronic liver injury in rats and humans upregulates the novel enzyme angiotensin converting enzyme 2. Gut. 2005;54(12):1790–1796. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herath C.B., Warner F.J., Lubel J.S., et al. Upregulation of hepatic angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and angiotensin-(1–7) levels in experimental biliary fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2007;47(3):387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studdy P., Bird R., Geraint James D., Sherlock S. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (Sace) in sarcoidosis and other granulomatous disorders. Lancet. 1978;312(8104):1331–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91972-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossen L., Rebora P., Bernuzzi F., et al. Soluble CD163 and mannose receptor as markers of liver disease severity and prognosis in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Liver International. 2020;40(6):1408–1414. doi: 10.1111/liv.14466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Graaf K., Lapeyre G., Guilhot F., et al. NI-0801, an anti-CXCL10 antibody, in patients with primary biliary cholangitis and an incomplete response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Hepatol Comm. 2018;2:492–503. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-Suárez C., Crespo J., Luis Fernández-Gil P., Amado J.A., García-Unzueta M.T. Pons Romero F. Plasma leptin levels in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and their relationship with degree of fibrosis. Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2004;27(2):47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(03)79085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szalay F., Folhoffer A., Horvath A., et al. Serum leptin, soluble leptin receptor, free leptin index and bone mineral density in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17(9):923–928. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piche T. Fatigue is associated with high circulating leptin levels in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2002;51(3):434–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jopson L., Jones D.E. Fatigue in primary biliary cirrhosis: prevalence, pathogenesis and management. Dig Dis. 2015;33(Suppl 2):109–114. doi: 10.1159/000440757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.