Abstract

Background

Majority of people in Ethiopia heavily rely on traditional medicinal plants to treat a number of diseases including tuberculosis (TB). However, there has been lack of comprehensive evidences on taxonomic distribution of medicinal plant species, methods of preparation of remedies from these plants and how the remedies are administered. This systematic review is designed to examine and synthesize available evidences focusing on medicinal plants that have been used for TB treatment in Ethiopia.

Methods

Research findings related to ethno-botanical and pharmacological approaches of TB remedies were retrieved from databases. Electronic libraries of Ethiopian Universities and relevant church-based religious books were also reviewed as additional sources. Evidences are searched and organized in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline.

Result

From a total of 68 research documents that reported use of plants for treatment of TB 98 plants species belonging to 82 genera and 49 families were identified. The most frequently reported plant species belonged to family Lamiaceae (n = 8), Euphorbiaceae (n = 7), Cucurbitaceae (n = 6) and Fabaceae (n = 6). Croton macrostachyus, Allium sativum, and Myrsine Africana were the most often mentioned anti-TB medicinal plants. Shrubs (35.7%) and trees (29.6%) were reported as dominant growth forms while plant roots (31.6%) and leaves (28.6%) were frequently used plant parts for the preparations of the treatment. The most favored administration route was oral (59.1%). About 87% of the preparations were made from fresh plant materials. No experimental/clinical evidence was presented for 79.6%(78/98) of the reported plants to support their anti-mycobacterial activities.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, the number of herbal remedies is enormous and their use for TB treatment is a common practice. However, majority of them are not yet backed up by evidence generated through scientific experimentation and this warrants further experimental and clinical validations. Moreover, the efficacy, toxicity and safety tests should be initiated and this would help in the rapid identification of new anti-TB regimens, and possibly it would lead to developing more effective new plant-based drugs. This systematic review will serve as a reference for the selection of plants for developing new anti-TB regimens.

Keywords: Medicinal plants, Traditional, Treatments, Tuberculosis, Ethiopia

Medicinal plants, traditional, treatments, tuberculosis, Ethiopia.

1. Introduction

The current modern treatment of TB depends on rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid and pyrazinamide, which are less effective (Brigden et al., 2014) and costly with serious side-effects (Bhatcha, 2013; Zazueta-Beltran et al., 2011; Mohan and Sharma, 2004). An emergence of drug resistant (Gupta et al., 2010; Zazueta-Beltran et al., 2011) and geographically specific strains of TB etiologies (Firdessa et al., 2013) has further exacerbated the situation (threat) in TB-burdened developing countries of Africa, and have necessitated a need to search for new treatment regimens that target medicinal plants (Andualem et al., 2014; Hostettmann et al., 2000; Kloos et al., 1978; Kloos, 1976; Askun et al., 2013; Bhatcha, 2013).

The use of medicinal plants remains the primary source of healthcare for majority of people in most of developing countries, it may reach 70–80% among the Africans, and it could be as high as 85% in the sub-Saharan Africa (Mann et al., 2008c; Mann et al., 2007; WHO, 2002; Zuberi, 2014; Andarge et al., 2015; Abbink, 2002; Obakiro et al., 2020). Medicinal plants may offer a new hope for developing alternative medicines for a number of diseases as they are easily accessible (Zuberi, 2014; Heinrich, 2000) and cheap with a minimum of side effects (Hostettmann et al., 2000; Siddiqui et al., 2014; Abebe, 1996). Plant derived medicines may also help in fighting drug resistance (Bhatcha, 2013; Singh et al., 2015) and combating geographically specific strains of TB etiologies (Gupta et al., 2010). Therefore, effective and alternative anti-TB drugs preferably plant-based ones have to be developed to fight drug resistance and to reduce TB associated mortality and morbidity (Andualem et al., 2014; Amsalu, 2010; Hostettmann et al., 2000; Enyew et al., 2014; Bishaw, 1991; Gupta et al., 2010).

In Ethiopia there are more than 6,600 vascular plant species (Bekele-Tesemma, 2007). From 70-80% of the Ethiopians still rely on traditional medicinal plants (TMPs) to treat a variety of diseases such as gastrointestinal (Belayneh et al., 2012; Bekalo et al., 2009), respiratory tract and sexually transmitted infections (Abera, 2014; Kewessa et al., 2015), hemorrhoids, rabies (Tesfahuneygn and Gebreegziabher, 2019), hypertension, diabetes (Andarge et al., 2015), malaria (Abbink, 2002; Alemneh, 2021a, Alemneh, 2021b; Agize et al., 2013) and others (FMOH, 2003; Negussie, 1988; Birhan et al., 2011). However, there has been no study that has synthesized existing evidence focusing on documentation of traditional medicinal plants (TMPs) being used in treating TB in Ethiopia. And this has resulted in unavailability of comprehensive data on plant species, methods of preparation and administration of traditional TB remedies. This systematic review was designed to address this gap by documenting existing TMPs that are being used in TB treatments in Ethiopia. In this paper we report synthesis of existing evidence that was obtained from a systematic review of the available literatures on anti-mycobacterial plants with the hope of providing comprehensive data to hasten the research effort on development of novel plant derived drugs against human and bovine TB.

2. Methods

This systematic review and analysis of peer reviewed journal articles, Msc/PhD theses/dissertations, and unpublished documents related to medicinal plants used for the treatment of TB [n = 68] in Ethiopia was conducted over nine month period from November 2020 to July 2021.

2.1. Literature search strategy

Web-based systematic search strategy was employed. Ethno-botanical/ethno-medicinal studies reporting on medicinal plants used for traditional TB treatment in Ethiopia were gathered through two different search modalities for published and unpublished research findings. Google search engine and local university websites were assessed for unpublished MSc/PhD thesis research reports while international scientific databases that include PubMed, Research gate, Science direct, Web of Science, Google Scholar, academia edu, and AJOL were used as sources of published journal articles. The search was done using several key terms: Ethiopia/Ethiopian plants/Ethiopian medicinal plants/anti-tuberculosis plants, anti-lymphadenitis/gland TB plants, traditional knowledge/TMPs, herbal medicine/remedies, indigenous knowledge, folk medicine/remedies, ethno-botany/ethno-botanical, ethno-pharmacological/medicine/, ethno-pharmaceutical, cultural medicine following “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)” guidelines and guidance (Moher et al., 2009a, Moher et al., 2009b).

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Published and unpublished ethno-botanical/medicinal reports including experimental studies about treatments of TB in Ethiopia and reported before May 2021 were included.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Information from published and unpublished ethno-botanical and ethno-medicinal surveys lacking scientific plant names and not reporting information about anti-TB medicinal plants were excluded from the analysis.

2.4. Screening and criteria

For this systematic review, the title and abstract of identified journal articles/theses/dissertations/reports were downloaded and all those suitable for the purpose were screened out and critically inspected for inclusion.

2.5. Data retrieval

A data collection tool was developed in Microsoft Excel format into which all retrieved data (botanical name, plant family, local name(s), part(s) used, habit of growth, preparation and administration mode, extraction method of each plant used for TB treatment), were entered. Missed information in some studies, particularly local name and habit of the plants, geographic locations of the study localities/districts, and misspelled scientific names were retrieved and corrected through direct web-searching.

2.6. Data analysis

All retrieved relevant data about the Ethiopian TMPs were entered into structured Microsoft office Excel format and exported to Statistical Software Packages for Social Science (SPSS, software version 20.0). Descriptive statistical methods, percentage and frequency were used to analyze ethno-botanical data on reported medicinal plants.

3. Results

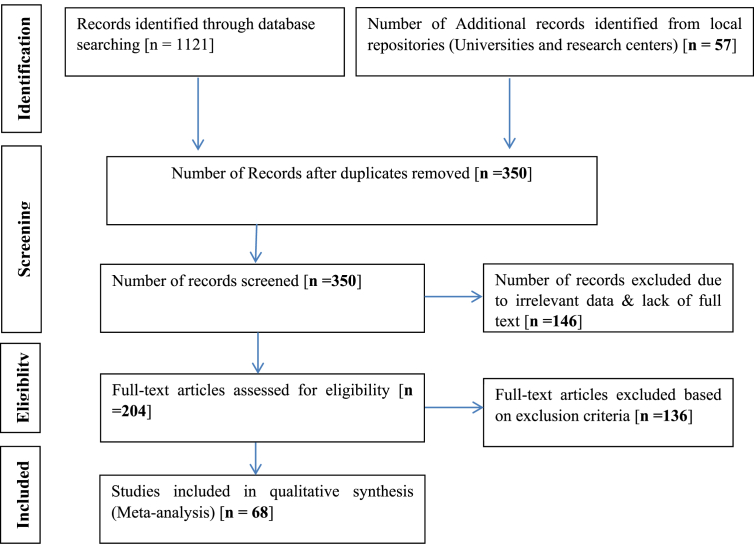

Peer reviewed journal articles, M.Sc./Ph.D. theses/dissertations research reports representing ten different regional states of Ethiopia and other unpublished documents [n = 68] were included and analyzed in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of retrieved and analyzed literatures/papers (adapted from PRISMA, 2020) (Page et al., 2021).

3.1. Taxonomic distribution of herbal medicines of TB in Ethiopia

A total of 98 different plant species that are used to treat TB traditionally were retrieved from 68 ethno-medicinal study reports recruited for this review. The plants were from 82 genera and 49 families. While taxonomic summary of reported plants is put in Table 1, detailed taxonomic and geographic distribution, habit, parts used, modes of preparation and routes of administration and dosage of herbal remedies of TB is found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Taxonomic distribution of herbal medicines used for the treatment of TB in Ethiopia.

| Family | Genera | Species | Family | Genera | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamiaceae | 5 | 8 | Anacardiaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Cucurbitaceae | 4 | 6 | Asclepiadaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Fabaceae | 4 | 6 | Combretaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Euphorbiaceae | 5 | 7 | Meliaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Asteraceae | 3 | 3 | Myrsinaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Capparidaceae | 3 | 3 | Rosaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Malvaceae | 3 | 3 | Rutaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Apocynaceae | 2 | 3 | Rubiaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Myrtaceae | 2 | 3 | Alliaceae | 1 | 3 |

| Oleaceae | 2 | 3 | Ranunculaceae | 1 | 2 |

| Solanaceae |

2 |

3 |

Other families |

29 |

29 |

| Total | 82 | 98 |

Table 2.

Taxonomic and geographic distribution, habit, parts used, modes of preparation and routes of administration and dosage of herbal remedies of TB.

| SN | Family Name | Botanical name | Common name(s)/language name/s | Region | Habit | Part used | ROA | Mode of preparation/Types of TB | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lamiaceae | Artemisia abyssinica Shc.Bip.ex.A.Rich | Tiroo (Oro) | Oro | H | Lv | Or | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Bekalo et al., 2009) |

| 2 | Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd | Chiqugn (Amh) | Oro | H | Lv | Or | Not specified | (Bekalo et al., 2009; Yineger et al., 2008) | |

| 3 | Clerodendrum myricoides Hochst. Vatke | Aghio (kaficho) | Kaffa | Sh | Or | Not specified | (Abate, 1989) | ||

| 4 | Ocimum americanum L. | Zeka-keba (Amh) | SNNP | H | Fr | Not specified | (Bekalo et al., 2009) | ||

| 5 | Ocimum basilicum L. | Besobilla (Amh) | Amh | H | Sd | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013) | ||

| 6 | Ocimum lamiifolum Hochst. ex Benth.... | Demakessie (Oro) | Oro | T | Lv | Fresh leaves pounded and juice is drunk | (Gizachew et al., 2013; Mesfin et al., 2005; Getahun, 1976) | ||

| 7 | Oenanthe procumbens (H. Wolff) Norman | Bunkaka Hida (Or) | Amh | Sh | Lv | Or, Sk | Oral/skin EPTB | (Amsalu, 2010) | |

| 8 | Otostegia integrifolia Benth | Tinjute (Amh) | Amh | Sh | Rt | Or, Ins | Fresh or dried leaf is used as fire fumigation | (Kahaliw, 2016; Enyew et al., 2014) | |

| 9 | Euphorbiaceae | Clutia abyssinica Kaub. & Spach. | Yemar semat (G) | SNNP | Sh | Lv | Or | Infusion | (Teka et al., 2020) |

| 10 | Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile | Masincho (Si) | SNNP | T | Ba | Or | Boiling leaves of shoots in water and decanting the toxic water, & allowed to dry. Mixing dry fine powder with powder of spices & water, and giving about two syringes per day for a month | (Tefera and Kim, 2019; Kewessa et al., 2015; Gonfa et al., 2015; Balcha et al., 2014; Gemechu et al., 2013; Amsalu, 2010; Geyid et al., 2005) | |

| 11 | Euphorbia candelabrum Ketshy | Kulkual (Amh) | Amh/Oro | T | Lq | Or | Dropping diluted in water (drinking) | (Bekele and Reddy, 2014; Mesfin et al., 2013) | |

| 12 | Euphorbia tirucali L. | Kenchib (Amh) | T | Lq | Not specified | (Genene and Hazare, 2017) | |||

| 13 | Euphorbia cryptospinosa Bally | Aananno (Oro) | Oro | C | Rt | Or | Crushing internal part of the root with the roots of Solanum incanum & Osyris quadripartita, making s/n & adding honey then drinking as necessary when the patients become thirsty | (Fenetahun and Eshetu, 2017; Ashagre et al., 2016) | |

| 14 | Jatropha glauca Vahl. | Qablis (Af) | Afar | Sh | Rt | Or, Ins | Making infusion of fresh root and administering intranasal and orally | (Seifu, 2004) | |

| 15 | Ricinus communis L. | Qobbo | Oro | Sh | Lv | Or | Rubbing fresh warmed leaf with fine on the swelling | (Wolditsadik, 2018) | |

| 16 | Cucurbitaceae | Coccinia abyssinica (Lam.) Cogn | Anchote (Oro) | Oro | H | Rt | Or | Cooking its root with leaves of Croton macrostachyus and eating with ‘injera’ for four days | (Birhanu et al., 2015; Dawit and Estifanos, 1991; Megersa et al., 2013; Getahun, 1985; Amare, 1973) |

| 17 | Cucumis dipsaceus Ehrenb. | Hafaflo (Tig) | Tig | C | Rt | Or | Not specified | (Zenebe et al., 2012) | |

| 18 | Cucumis ficifolius A.Rich | Yemdir embouy (Amh) | SNNP/Amh/Tig | H | Fr | Or | Mixing its fruit with root of Gnidia involucrata and bulb of garlic, crushing and soaking it 7 days in local “Tella” and taking one cup for five days or powdered, mixed with water, drink | (Araya et al., 2015; Regassa, 2013; Gebeyehu, 2011) | |

| 19 | Cucumis pastulatus L. | Qalfoon (Som) | Oro | C | RT | Or | Chewing the root or crushing the root, making s/n and drinking one coffee cup daily until cured | (Ashagre et al., 2016; Balemie et al., 2004) | |

| 20 | Momordica foetida Schumach | Yubarrae | SNNP | C | Rt | Or | Crushed/pounded fresh/dry root mixed with Allium sativum bulb is taken orally before breakfast for three days. | (Mesfin et al., 2009) | |

| 21 | Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond. | Haregresa (Amh) | Amh | H | St, Lv | Sk/To | Not specified | (Alemneh, 2021a, Alemneh, 2021b) | |

| 22 | Fabaceae | Acacia albida Del. | Gerbi (Oro) | Oro/SNNP | T | AP | Or | Concoction, crushed | (Temam and Dillo, 2016; Belayneh et al., 2012) |

| 23 | Acacia mellifera (M. Vahl) Benth | Kontir grar (Amh) | Afar | Sh | Lv | Or | ETPB (fresh leaves consumption) | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) | |

| 24 | Acacia oerfota (Forssk.) Schweinf | Wanga (Or) | Afar | Sh | Rt | Or, Ins | Fresh root consumption | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) | |

| 25 | Calpurnia aurea (Aiton) Benth. | Hitsawutse (Tig) | Tig | Sh | Rt | Or | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Zenebe et al., 2012) | |

| 26 | Erythrina brucei Schweinf | Woleko (Sid) | SNNP | T | Ba | Or | Not specified (Bovine TB) | (Kewessa et al., 2015) | |

| 27 | Pterolobium stellatum (Forsk.) Brenan. | Kentefa (Amh) | Amh/Tig | Sh | Rt | Not specified | (Kahaliw, 2016; Balcha et al., 2014) | ||

| 28 | Alliaceae | Allium cepa L. | Qey shinkurt (Amh) | Oro | B | Bu | Or | Fresh chewing | (d’Avigdor et al., 2014; Fulas, 2007; Fullas, 2003) |

| 29 | Allium ursinum L. | Yejib shinkurt (Amh) | Tig | B | Fr | Or | Fresh fruits crushed & blended with honey & butter | (Balcha et al., 2014; Gemechu et al., 2013; Belayneh et al., 2012; Yirga, 2010) | |

| 30 | Allium sativum L. H | Kashari shunkurutta (Oro) | Oro/SNNP/Tig | B | Bu/Lv | Or | Taking orally grinded and mixed with honey | (Osman et al., 2020; Belayneh et al., 2012; Mesfin et al., 2009; Wondimu et al., 2007) | |

| 31 | Apocynaceae | Carissa edulis Vahl | Agam (Amh) | Amh | T | Rt | Or | Not specified | (Kahaliw, 2016) |

| 32 | Carissa spinarum L. | Otilaa (Si) | SNNP | Sh | Fr | Or | Not specified | (Kewessa et al., 2015) | |

| 33 | Kanahia laniflora (Forssk.) R. Br. | Leehamohcaxa (Af) | Afar | Sh | Lv | Or, Ins | Making infusion of fresh leaves and administering intranasal and a small amount orally | (Seifu, 2004) | |

| 34 | Asteraceae | Echinops kebericho Mesfin | kebericho (Oro) | Oro | H | Rt | Not specified | (d’Avigdor et al., 2014; Abebe et al., 2003) | |

| 35 | Laggera tomentosa (Sch.Bip.ex A.Rich.) Oliv.& Hiern | Keskessie (Amh) | Amh | T | LV | Sk/To | Tying fresh pounded leaf on the swelling. | (Wolditsadik, 2018) | |

| 36 | Vernonia amygdalina Del. | Grawa (Amh) | Amh | Sh | Rt | Not specified | (Kahaliw, 2016) | ||

| 37 | Capparidaceae | Balanites rotundifolia (van Tiegn) Blatter | Alayto (Af) | Afar | Sh | Lv | Or, Ins, Sk/To | Crsuhing leaves ETPB (Hu + Bovine TB) | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) |

| 38 | Boscia angustifolia A. Rich | Kermed (Tig) | Tig | T | Ba | Or | Crushing together with whole part of Celtis Africana homogenize with water and drinking a bottle cup of the solution for 7 consecutive days in the morning | (Gidey et al., 2015) | |

| 39 | Cadaba rotundifolia Forssk | Kenquele (Kam) | Afar | Sh | Lv | Or, Ins | Bovine TB (fresh leaves consumption) | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) | |

| 40 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus cannabinus L. | Dans's'a (Dawro) | SNNP | Sh | Fl | Or | Chopped, pound | (Agize et al., 2013) |

| 41 | Malva parviflora L | Siito (Halaba) | SNNP | H | Lv | Or | The leaf is crushed, powder mixed with water drunk | (Regassa et al., 2017) | |

| 42 | Sida schimperiana Hochst. ex A. Rich | Chefreg (Amh) | H | Rt | Not specified | (Genene and Hazare, 2017) | |||

| 43 | Eucalyptus spps. | Bahir zaf (Amh) | Tig | T | Lv | Not specified | (Birhanu et al., 2015) | ||

| 44 | Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh | Key bahir zaf (Amh) | Tig | T | Lv | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Birhane et al., 2011) | |

| 45 | Syzygium guineense (Willd.) DC. | Duwancho (Sid) | SNNP | T | Bk | Or | Not specified (used for both human and bovine TB) | (Kewessa et al., 2015) | |

| 46 | Oleaceae | Jasminum abyssinicum Hochst. | Tembelel (Amh) | Amh | T | AP | Not specified | (Geyid et al., 2005) | |

| 47 | Olea europaea L. | Woira (Amh) | Oro/SNNP/Afar | T | Fr | Or | Not specified | (Legesse et al., 2011; Teklehaymanot and Giday, 2010; Amenu, 2007) | |

| 48 | Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. Ex G.Don.) Cif | Ejersa (Oro) | Oro | T | Rt | Sk/To | The extracted oil from the roots put on the affected site (Bone TB) EPTB | (Jima and Megersa, 2018; Kewessa et al., 2015) | |

| 49 | Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | Geed case (Som) | Som | H | WP | Or | Grounding the stem and dissolving with water & drinking | (Issa, 2015) |

| 50 | Solanum anguivai Lam. | Ambu (Bench) | SNNP | Sh | Lv | Sk/To | Pounding leaf and apply topically for gland TB | (Giday, 2009a; 2009b) | |

| 51 | Solanum marginatum L. f. | Abyiengule(Tig) | Tig | Sh | Sds | Or | Drying seeds, crushing & adding into milk or coffee and solution taking every morning for 21 days (even for cattle) | (Araya et al., 2015) | |

| 52 | Anacardiaceae | Rhus vulgaris Meikle | Kammo (Amh) | Amh | Sh | Fr | Or | Grounding fruits are mixing with honey and one glass is drunk on empty stomach until recovery. | (Gebeyehu, 2011) |

| 53 | Schinus Molle L. | Kundo berbere (Amh) | Oro | T | Sd | Or | Crushing seeds and mixing with honey and eating | (Getaneh and Girma, 2013) | |

| 54 | Asclepiadaceae | Calotropis procera (Ait.) Ait | Ginda (Tig) | Tig | Sh | Rt | Ins | Crushing its roots into powder and mix with pounded bark of Croton macrostachyus and leaves of Ficus palmate & sniffing | (Araya et al., 2015) |

| 55 | Dregea sp. | Geed sare (Sum) | Som | C | Lv | Or | Grinding leaves and boiling with milk and drinking | (Issa, 2015) | |

| 56 | Combretaceae | Combretum molle G. Don | Xamasuda (Sum) | Som | T | Lv | Or | Grounding the leaves boiling and drinking | (Issa, 2015) |

| 57 | Corrigiola capensis subsp. Africana | Dakagella (ku) Kunama | Tig | T | Lv | Or | Crushing the leaf, and drink a cup of the juice for three consecutive days | (Gidey et al., 2015) | |

| 58 | Meliaceae | Trichilia dregeana Sond | Anunu (Amh) | Oro | T | Rt | Or | Powdering and taking its 1/2 cup of tea | (Etana, 2015) |

| 59 | Ekebergia capensis Sparrm. | Olonchoo (Sid) | SNNP | T | Ba | Or | Crushing and pounding mixing with Hot Water/Bovine TB | (Tefera and Kim, 2019; Kewessa et al., 2015; Banerjee et al., 2014) | |

| 60 | Myrsinaceae | Embelia schimperi Vatke. | Sharrengo (Gedio) | SNNP | Sh | Rt | Or | Crushing fresh root with water and taking that for several days | (Mesfin et al., 2009) |

| 61 | Myrsine Africana L. | Qacama (Oro) | Oro | Sh | Lv | Leaves crushed and squeezed in fresh form with water. The juice was then indicated to be drunk in very small amount for three days | (Gizachew et al., 2013; Yineger and Yewhalaw, 2007; Wolde and Gebre-Mariam, 2002; Desissa and Binggeli, 2000) | ||

| 62 | Ranunculaceae | Clematis hirsute Perr. & Guill. | Fiitii (Oro) | Oro | C | Lv | Sk/To | Pounding the leaves, dissolving in water &drinking half of small glass & applying certain amount of the solution into the wound's opening using syringe, and also putting residues on its opening (gland TB) | (Fenetahun and Eshetu, 2017; Ashagre et al., 2016; Temam and Dillo, 2016) |

| 63 | Clematis simensis Fres. | Azo-hareg (Amh) | SNNP/Oro | C | AP | Or | Not specified | (Temam and Dillo, 2016; Geyid et al., 2005) ( | |

| 64 | Rutaceae | Citrus limon (L.) Burm.f. | Lemin (Tig) | Tig | Sh | Fr | Or | Not specified | (Zenebe et al., 2012) |

| 65 | Clausena antisata (Willd.) Benth. | Agam (Amh) | Oro | Sh | Lv | Or | Not specified | (Gizachew et al., 2013; Yineger and Yewhalaw, 2007) | |

| 66 | Rosaceae | Rosa x richardii Rehd. | Tsigereda | Amh | Sh | Fl | Sk/To | As a skin tie (Gland TB) and also for Bone TB | (Alemneh, 2021a, Alemneh, 2021b) |

| 67 | Rubus apetalus Poir | Go'ra (Oro) | SNNP | Sh | Rt | Or | The root is pounding root, boiling, and drinking | (Tuasha et al., 2018; Gedif and Hahn, 2003) | |

| 68 | Rubiaceae | Psydrax schimperiana (A.Rich.) Bridson | Gaalle | Oro | T | Rt | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Lulekal et al., 2008) | |

| 69 | Rubia cordifolia L. | Mencherer | Amh | C | Rt | Or | Crushing and smashing root in water in 3 days then drink | (Chekole, 2017) | |

| 70 | Agaveace | Indigofera amorphoides Jaub. et Spach | Jeere (Oro) | Oro | H | Rt | Not specified | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Lulekal et al., 2008) | |

| 71 | Amaranthaceae | Celosia polystachia (Forssk.) C.C. Towns.∗ | Kontoma (Af) | Afar | H | Rt | Or, Ins | Root consumption | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) |

| 72 | Amaryllidaceae | Scadoxus multiorus (Martyn) Raf. | Ija Dhukkubsituu (Or) | Amh | H | Rt | Sk/To | Not specified | (Alemneh, 2021a, Alemneh, 2021b) |

| 73 | Apiaceae | Anethum graveolens L. (dill) | Ensilal (Amh) | Tig | H | AP | Or | Not specified | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| 74 | Araceae | Arisaema schimperianum Schott | Amoch (Amh) | Oro | H | Lv | Or | Not specified | (Yineger et al., 2008) |

| 75 | Asphodelaceae | Aloe species | Quureyta (Af)/Riet (Amh) | Afar/Amh | Sh | St/Rt | Or | Drinking its infusion mixed with roots of Tamarix aphylla and root of Salvadora persica L,. Also, taking orally dried, powdered root buried for 6 months mixed with honey or only Aloe sp root buried for 6 months, dried and powdered then mixed with 1kg of honey and taken orally | (Zewdu et al., 2015; Seifu, 2004) |

| 76 | Balanitaceae | Balanites aegyptiaca (van Tieghem) Blatter | Uda (Af) | Afar | Sh | Lv | Or, Ins | Fresh leaves consumption | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) |

| 77 | Boraginaceae | Bourreria orbicularis (Hutch. & E.A. Bruce) Thulin | Ulageita (Af) | Afar | Sh | Fr | Or, Ins | Bovine TB (fresh fruit consumption) | (Teklehaymanot, 2017) |

| 78 | Brassicaceae | Lepidium sativum L. | Shunfax (Som) | Som/Oro | H | Sd | Or, Sk/To | Swallowing fresh seeds, applying on open swelling or wound, adding small amount of sulphur & covering it with seed paste of L. Sativum & latex of C. Procera (EPTB topical-for gland TB) | (Temam and Dillo, 2016; Araya et al., 2015; Issa, 2015) |

| 79 | Canellaceae | Warburgia ugandensis Sprague | Kenefa/Zogdom (Amh) | Oro | T | Bk | Not specified | (Giday, 2009a, 2009b; Lulekal et al., 2008; Wube et al., 2005) | |

| 80 | Celastraceae | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) | Kombolicha (Oro) | Oro | Sh | Rt | Or | Powdered or as an infusion (taken in/drunk) | (Bekele and Reddy, 2014) |

| 81 | Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill | Avocado | Amh | T | Lv | Not specified | (Kahaliw, 2016) | |

| 82 | Logianiaceae | Buddleja polystachia | Anfar- (Tig) | Tig | T | Lv | Or | Not specified | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| 83 | Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus globiferus (A. Rich.) Tiegh. | Hafa-teketsila (Amh) | Amh | H | WP | Sk/To | Appliying on Skin for Gland TB | (Giday et al., 2007) |

| 84 | Meliantaceae | Bersama abyssinica Fresen | Jejjebba | SNNP | Sh | Rt | Or | Crushing/pounding fresh root mixed with cold water and taking orally | (Mesfin et al., 2009) |

| 85 | Moraceae | Ficus palmata Forssk | Qotilebele-s | Tig | Sh | Lv | Ins | Crushing its leaves with roots of C. Procera is into powder and mixing with pounded bark of Croton macrostachyus &sniffing | (Araya et al., 2015) |

| 86 | Olacaceae | Ximenia americana L. | Hudhaa (Oro) | Oro | T | Rt | Or | Chewing, infusion with hot drinks, eating together with other foods | (Wondimu et al., 2007) |

| 87 | Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago zeylanica L. | Amira (Agew) | Amh | Sh | Lv | Sk/To | Crushed leaves and skin tie (Gland TB) and also for Bone TB | (Giday, 2009a, 2009b; Teklehaymanot, 2009) |

| 88 | Santalaceae | Osyris quadripartita Decn | Waatoo (Oro) | Oro | Sh | Lv, Rt | Or | Pounding them to make solution and drinking 1 water glass daily for a month | (Ashagre et al., 2016) |

| 89 | Thymelaeaceae | Gnidia involucrata Steud | Boto (Amh) | Amh | H | Rt | Or | The root mixed with the fruit of Cucumis ficifolius and bulb of garlic are crushed and soaked 7 days in local “Tella” and one cup is taken for five days | (Gebeyehu, 2011) |

| 90 | Xygophyllaceae | Balanites aegyptiacus (L.) Delile | Mekie (Tig) | Tig | T | Fr | Or | Not specified | (Zenebe et al., 2012) |

| 91 | Polygonaceae | Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. | Mekmoko (Oro) | Tig/Oro | H | Rt | Sk/To | Making paste and mixing with cow butter as ointment | (d’Avigdor et al., 2014; Moravec et al., 2014; Zenebe et al., 2012; Gebeyehu, 2011; Abebe et al., 2003; Gedif and Hahn, 2003) |

| 92 | Salvadoraceae | Salvadora persica L | Qadayto (Af) | Afar | T | Rt | Or | Making ihe infusion of the root, and the leaves of Aloe sp. And administering orally with root of Tamarix aphylla | (Seifu, 2004) |

| 93 | Sapindaceae | Dodonaea angustifolia L.F. | Kitkita (Amh) | Tig/SNNP | Sh | Fr | Or | Powdering dry fruit with water and giving orally | (Balcha et al., 2014; Birhane et al., 2011; Mesfin et al., 2009) |

| 94 | Scrophulariaceae | Striga hermonthica (Del.) Benth | Adiri bereka (Tig | Tig | H | Lv | Or | Crushing the leaf, homogenizing with water anddrinking | (Gidey et al., 2015) |

| 95 | Tamaricaceae | Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst | Saaganto (Af) | Afar | T | Rt | Or, Ins | Making infusion of its root with root of Tamarix aphylla and leaves of Aloe spp and administer orally with Salvadora persica. | (Seifu, 2004) |

| 96 | Vitaceae | Celtis Africana Burm.f. | Aga (Ku) | Tig | C | WP | Or | Crushing together with bark of Boscia angustifolia homogenize with water and drinking a bottle cup of the solution for 7 consecutive days in the morning | (Gidey et al., 2015) |

| 97 | Viscaceae | Viscum tuberculatum A. Rich | Cudurka Qaaxada (Sum) | Som | T | Lv | Or | Grounding leaves, disperse in water & drink | (Issa, 2015) |

| 98 | Zingiberaceae | Zingiber offfcinale Roscoe | Zingibil (Amh) | Amh/Tig | H | Rh | Or | Chewing and swallowing (bone TB) | (Giday et al., 2007) |

Key: growth forms (T = tree, B = bulb, Cl = climber, H=Herb, Sh = shrub, Rh= Rhizome).

PU-Parts used = (Lf = leaf, Rt = root, Ba = bark, Fl = flower, Fr = fruit, Sd = seed, Lq = liquid, Sh = shoot, St = stem, AP = Aerial part, WP = Whole part).

Routes of administration = ROA (Or = oral, Sk/To = Skin tie or Topical, Ins = intranasal).

Local names: Amh = Amharic, G = Gurage, Tig = Tigrigna, Oro = Afaan Oromoo, Sid = Sidamu-afoo, Age: Agewugna, Kem = Kambatissa, Som = Somali, Ku = kunama, NA = not available.

Types of TB: EPTB = extrapulmonary TB, BTB = bovine TB.

3.2. Growth habit of medicinal plants, parts used, condition of preparations and routes of administration

3.2.1. Growth form of plants used for TB treatment

The growth forms of herbal remedies of TB indicated that the shrubs had the highest proportion with 35.7% of the species while trees (29.6%), herbs (22.4%) and climbers (9.2%) made up the second highest proportion. The remaining 3.1% were the bulbs.

3.2.2. Plant parts used for remedy preparation

Many plant parts are utilized in Ethiopia for anti-TB remedy preparation. Most of the preparation of herbal TB medicines involved the use of a single plant part (95.9%). Plant roots (31.6%) occupied the largest proportion followed by the leaves (28.6%). In a few of TM of TB, use of aerial plant parts (n = 4), seeds (n = 4) and barks (n = 4) were also indicated. But in the remaining proportion, different parts of the plants were mixed together to prepare traditional TB remedies. Flowers, stems and the whole plant parts were reported as very rarely used parts for the preparation. Moreover, majority of the remedies were prepared from freshly harvested parts of medicinal plant species (73.5%) (Table 2).

3.2.3. Preparation and routes of administration of herbal recipes for TB treatment

Different formulations and application procedures of medicinal plant preparations were used to treat TB across the regions of Ethiopia. The most commonly used route of administration was oral (59.2%) followed by dermal/topical route (for gland TB), (10.2%). Intranasal application or sniffing is the least reported route of application, (3.1%). But for (16.7%) plant species the administration routes of TB TM have not been reported. The major modes of remedy preparation from medicinal plant materials were crushing (52%) followed by pounding (29.6%) (Table 2).

Out of a total of all reported traditionally used TB remedies 87.7% and 10.4% plant species were described to be used for the treatment of pulmonary TB (PTB) and extra-pulmonary TB (EPTB), respectively, while 5.2% were used for bovine TB (BTB) (Table 2).

3.3. Solvents and additives for preparation of anti-TB herbal medicines

The reported herbal medicines of TB in Ethiopia are prepared by using fresh material, dried form and in some cases either fresh or dried form of the plant parts. During the preparation of most of the TM of TB, water is used as a solvent and in some cases milk and alcohols are added. Milk, cow butter and honey are the commonly used additives to prepare the medicinal plant materials. A few of these TM are also recommended to be taken with hot drinks and “injera” Table 2.

3.4. Geographic distribution and frequency of citations of anti-TB medicinal plants

The largest number of herbal TB treatments were reported from Oromia Regional State (n = 22; 22.4%) followed by Tigray (n = 16; 16.3%) and Amhara, (n = 14; 14.3%). From each of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional (SNNPR) States and Afar region (n = 13; 13.3%) plant species were described. In the study reports across the country, Croton macrostachyus (n= 7), Allium sativum (n = 5), Myrsine africana (n = 4), Zingiber offfcinale (n = 4) and Allium ursinum (n = 4) are the most frequently reported plant species. The frequency of reports across the regions and distribution in the Ethiopian Flora Region are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The most frequently reported herbal medicines used for the treatment of TB in Ethiopia.

3.5. Medicinal plants with documented experimental/clinical evidence for anti-mycobacterial activity

Seventy eight (79.6%) plant species reported in this review had no experimental/clinical evidences for their ability to kill the etiologies of TB. Allium ursinum, Dodonea anguistifolia (Balcha et al., 2014; Gemechu et al., 2013), Artemisia abyssinica, Croton macrostachys, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Ocimum basilicum (Gemechu et al., 2013), Otostegia integrifolia (Kahaliw, 2016; Enyew et al., 2014), Pterolobium stellatum (Balcha et al., 2014), Carissa edulis, Persea americana, Vernonia amygdalina (Kahaliw, 2016) were some of the plants on which clinical/experimental investigations were carried out in Ethiopian research centers and Universities. Though all the remaining plant extracts show the ability to kill mycobacterial species, Carissa edulis, Vernonia amygdalina (Kahaliw, 2016) and Anethum graveolens (Balcha et al., 2014), failed to show any anti-mycobacterial activities. Particularly, Otostegia integrifolia (Kahaliw, 2016; Enyew et al., 2014) Persea americana (Kahaliw, 2016), Pterolobium stellatum (Kahaliw, 2016; Balcha et al., 2014) and Jasminum abyssinicum (Geyid et al., 2005) were reported to show significant anti-mycobacterial activities (Table 4).

Table 4.

List of medicinal plants with documented experimental/clinical evidence for anti-mycobacterial activity.

| Botanical name | Family Name | Parts used | Effectiveness | Solvent/Extraction done by | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allium ursinum | Alliaceae | Bu | Reported as effective | Methanolic extract- | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| Anethum graveolens | Apiaceae | AP | Reported as negative | Methanolic extract- | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| Artemisia abyssinica | Lamiaceae | Lv | Reported as effective | 80% methanolic crude extracts | (Gemechu et al., 2013) |

| Buddleja polystachia | Logianiaceae | Lv | Reported as negative | Methanolic extract- | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| Calpurnia aurea. | Fabaceae | Rt | Reported as effective | 80% methanolic crude extracts | (Gemechu et al., 2013) (Zenebe et al., 2012) |

| Carissa edulis Vahl | Apocynaceae | Rt | Failed | Chloroform- maceration | (Kahaliw, 2016) |

| Clausena antisata | Rutaceae | Lv | Reported as effective | Crude aqueous and meoh extracts | (Gizachew et al., 2013; Yineger and Yewhalaw, 2007) |

| Dodonea anguistifolia | Sapindaceae | Lv | Reported as effective | Methanolic extract- | (Balcha et al., 2014) |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Myrtaceae | Lv | Reported as effective | 80% Methanolic crude extracts | (Gemechu et al., 2013) (Birhane et al., 2011) |

| Jasminum abyssinicum. | Oleaceae | AP | Reported as effective | Methanol extract- soxhlet | (Geyid et al., 2005) |

| Myrsine africana | Myrsinaceae | Lv | Reported as effective | Crude aqueous and methanolic extracts | (Gizachew et al., 2013; Wolde and Gebre-Mariam, 2002; Desissa and Binggeli, 2000; Yineger and Yewhalaw, 2007) |

| Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Sd | Reported as effective | 80% methanolic crude extracts | (Gemechu et al., 2013) |

| Otostegia integrifolia | Lamiaceae | Rt | Reported as effective with significant Anti-MTB activity | Chloroform- maceration/80% methanol- soxhlet | (Kahaliw, 2016) (Enyew et al., 2014) |

| Persea americana | Lauraceae | Lv | Reported as effective with significant Anti-MTB activity | Acetone/80% methanol | (Kahaliw, 2016) |

| Pterolobium stellatum | Fabaceae | Rt | Reported as effective with significant Anti-mycobacterial activity | Chloroform/80%- maceration methanol- soxhlet | (Kahaliw, 2016; Balcha et al., 2014) |

| Vernonia amygdalina. | Asteraceae | Rt | Failed | Chloroform- maceration | (Kahaliw, 2016) |

| Warburgia Ugandensis | Canellaceae | Ba | Reported as effective with significant Anti-mycobacterial activity | (Giday, 2009a, 2009b; Lulekal et al., 2008; Wube et al., 2005) | |

| Croton macrostachyus | Euphorbiaceae | LV | Reported as effective with significant Anti-mycobacterial activity | Methanolic extract- | (Gemechu et al., 2013; Geyid et al., 2005) |

| Coccinia abyssinica | Cucurbitaceae | Rt | Reported as effective its juice has saponin as an active substance and is used to treat TB | (Dawit and Estifanos, 1991) | |

| Clematis simensis | Ranunculaceae | AP | Methanolic extract- | (Geyid et al., 2005) |

4. Discussion

Ethiopia is endowed with abundant medicinal plant resources and traditional herbal practices. Majority of its people live in rural areas and still relies on TMPs for the treatment of human and livestock ailments including TB (Abebe, 2001; Ashagre, 2011; Banerjee et al., 2014; Genene and Hazare, 2017). However, available research evidences on herbal remedies of TB in the country is highly fragmented.

In this review, 98 different plant species from 82 genera and 49 families that are used to treat TB traditionally were retrieved but it was found higher than review reports from India (Arya, 2011), South Africa (Semenya and Maroyi, 2013) and Uganda (Bunalema et al., 2014) that reported 48, 21 and 90 plant species, respectively. Higher report of anti-TB herbal medicines indicates the reliability of Ethiopians on TM, and this could be due to the high cost of modern drugs, paucity and inaccessibility of modern health services, and cultural acceptability of herbal medicines (Agize et al., 2013; Banerjee et al., 2014; Gedif and Hahn, 2003; Teklehaymanot and Giday, 2010; Seifu, 2004). Of these plant species, shrubs had the highest proportion (35.7%) of plant species which are followed by trees (29.6%), and herbs (22.9%). This finding is consistent with a number of ethno-botanical studies from Ethiopia (Bhatcha, 2013; Abebe, 2011; Alemneh, 2021a, Alemneh, 2021b; Jima and Megersa, 2018; Gonfa et al., 2015) and beyond (Obakiro et al., 2020; Bhatcha, 2013). This may be explained by the fact that shrubs are perennial in the arid or sub-arid environments and may be available for use as MPs.

Plants belonging to family Lamiaceae (8 species), Euphorbiaceae (7 species), Cucurbitaceae (6 species) and Fabaceae (6 species) were found as dominant families from which herbal remedies of TB prepared. Moreover, this review's finding of plant species belonging to Lamiaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Fabaceae is in line with the reports of Obakiro et al. from Eastern African countries that included Kenya, South Sudan Tanzania and Uganda (Obakiro et al., 2020; Tabuti et al., 2010). Moreover, significant anti-tubercular activity of plants from family Lamiaceae were also reported from Turkey (Askun et al., 2013) and Nigeria (Ibekwea et al., 2014), implying their higher potential as a target of future study. Moreover, plants belonging to the family Fabaceae were experimented to have biosynthetic phytochemicals with effective anti-mycobacterial activity in Ethiopia and Nigeria (Gemechu et al., 2013; Mann et al., 2008c; Ibekwea et al., 2014). However, plants in Hyacinthaceae, Moraceae and Rutaceae families were the most represented ones in a study from Southern Africa (Semenya and Maroyi, 2013).

According to this systematic review, 22(22.4%) of the herbal TB treatments were reported from Oromia Regional State followed by Tigray 16(16.3 %) and Amhara, 14(14.3%). From each of the SNNPR and Afar regional States, 13(13.3%) plant species were described.

Of the study reports across the country, Croton macrostachyus, Allium sativum, Myrsine Africana, Zingiber offfcinale and Allium ursinum were the most frequently reported plant species with frequencies of 7, 5, 4, 4, and 4, respectively. Similarly, studies that covered countries of Eastern Africa (Obakiro et al., 2020), India (Gupta et al., 2010; Arya, 2011) and others (Mann et al., 2008c) also revealed the potential of anti-tubercular activities of these plants. Therefore, these plant species should be considered as prime candidates for further in-depth experimental investigations. As the strains of mycobacteria are emerging and changing with specificities in some localities, these plant species could be used to tackle the challenges in TB control (Dawit and Estifanos, 1991; Worku, 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2014).

It is also disclosed that the use of a single plant part (96.9%) of which, the plant roots (31.6%) occupied the largest proportion followed by the leaves (28.6.1%) is more common. Flowers, stems and the whole plant parts were reported as very rarely used parts for the preparation. These findings are also found to be consistent with other studies (Giday et al., 2010; Lulekal et al., 2008) that reported leaves and roots as dominant parts against TB (Arya, 2011; Singh et al., 2015). But the use of plant roots for remedy preparation could significantly affect the sustainability of these herbal medicines unlike the use of aerial parts (Belayneh et al., 2012; Gedif and Hahn, 2003; Moges et al., 2019).

This review has also described oral and intranasal routes (>75%) as the most commonly used routes of administration, implying the herbal remedies are safe for systemic applications, and this was indicated in other studies from Ethiopia (Tesfahuneygn and Gebreegziabher, 2019), Malaysia (Sabran et al., 2016), India (Arya, 2011) and Eastern Africa (Obakiro et al., 2020).

The frequency of reports across the regions and distribution in the Ethiopian Flora are different but available experimental evidences are rare in the country in contrast to a study done in Nigeria (Ibekwea et al., 2014). Seventy eight (79.6%) of the plant species reported in this review had no experimental/clinical evidences for their ability to kill the etiologies of TB. Some evidences on the effectiveness of anti-mycobacterial activities of some herbal remedies of TB were done on Allium ursinum, Artemisia abyssinica, Carissa edulis, Croton macrostachys, Dodonea anguistifolia, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Ocimum basilicum, Otostegia integrifolia, Persea americana, Pterolobium stellatu, Vernonia amygdalina. While there were reports indicating negative anti-mycobacterial activities of Carissa edulis, Vernonia amygdalina (Kahaliw, 2016) and Anethum graveolens (Balcha et al., 2014). Particularly, Otostegia integrifolia (Kahaliw, 2016; Enyew et al., 2014) Persea americana (Kahaliw, 2016), Pterolobium stellatum (Forsk), Brenan (Kahaliw, 2016; Balcha et al., 2014) and Jasminum abyssinicum Hochst (Geyid et al., 2005) were reported to show significant ability to kill mycobacterial species (Table 3). This was also indicated in other studies. Experimental investigations of available anti-TB TMPs are much important for the purpose of potential identification of new antituberculosis drug regimens that further assist standardization of plant-based anti-TB recipes (Bunalema et al., 2014; Ibekwea et al., 2014; Arya, 2011) but in Ethiopia much remains to be done.

5. Conclusion

In Ethiopia, TB remains one of the most difficult public health concerns and majority of its people across the country still rely on a number of plants for its treatment. However, majority of these anti-TB plant species used by herbal practioners are not supported with scientific investigation, and this warrants further experimental and clinical validations of these commonly used TMPs of TB. Moreover, the efficacy, toxicity and safety tests should be initiated and this would help in the rapid identification of new anti-TB regimens, and possibly it will lead to a more effective drug development that could help in combating against the rapidly emerging and changing strains of TB etiologies with specificities in some localities.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abate G. Department of Biology,Science Faculty, Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 1989. Etse Debdabe (Ethiopian Traditional Medicine) [Google Scholar]

- Abbink J. Plant use among the Suri people of southern Ethiopia:a system of knowledge in danger? Afr. Arbeitspapiere. 2002;70:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe D. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Development and Utilization of Herbal Remedies in Ethiopia. Abebe D., editor. EHNRI; Addis Ababa: 1996. The role of herbal remedies and the approaches towards their development. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe D. Proceedings of the National Workshop. 2001. The role of medicinal plants in healthcare coverage of Ethiopia, the possible benefits of integration. Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia; pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe E. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa: 2011. Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants Used by Local Communities in Debark Wereda, North Gondar Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia: MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe D., Debella A., Urga K. Addis Ababa : Camerapix publishers international; 2003. Echinops Kebericho. Medicinal Plants and Other Useful Plants of Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Abera B. Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by Oromo people, Ghimbi District, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agize M., Demissew S., Asfaw Z. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in loma and Gena Bosa districts (Woredas) of Dawro zone, southern Ethiopia. Topclass J. Herb. Med. 2013;2(9):194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Alemneh D. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Yilmana Densa and Quarit districts, west Gojjam, Western Ethiopia. BioMed Res. Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6615666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemneh D. 2021. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Yilmana Densa and Quarit Districts, West Gojjam, Western Ethiopia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amare G. 1973. Developmental Anatomy of Tubers of Anchote; A Potential Dry Land Crop in Act Horticulture. Technical Communication of ISHS. [Google Scholar]

- Amenu E. Addis Ababa University; 2007. Use and Management of Medicinal Plants by Indigenous People of Ejaji Area (Chelya Woreda) West Shoa, Ethiopia: an Ethnobotanical Approach. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Amsalu N. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa: 2010. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Farta Wereda. South Gondar Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. MSc thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Andarge E., et al. Utilization and conservation of medicinal plants and their associated indigenous knowledge (Ik) in Dawuro Zone: an ethnobotanical approach. Int. J. Med. Plant Res. 2015;4:330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Andualem G., et al. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of methanol extracts of three medicinal plants in Ethiopia. Adv. Biol. Res. 2014;8(3):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Araya S., Abera B., Giday M. Study of plants traditionally used in public and animal health management in Seharti Samre District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:1–25. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0015-5. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya V. A review on anti-tubercular plants. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2011;3:872–880. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ashagre M. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa: 2011. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Guji Agro-Pastoralists. Bule Hora District of Borana Zone: Oromia Region, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ashagre E., Kelbessa E., Dalle G. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Guji agro-pastoralists, Blue Hora district of Borana zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2016;4:170–184. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Askun T., Tekwu E.M., Satil F., Modanlioglu S., Aydeniz H. Preliminary antimycobacterial study on selected Turkish plants (Lamiaceae) against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and search for some phenolic constituents. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcha E., et al. Evaluation of in- vitro antimycobacterial activity of selected medicinal plants in Mekelle, Ethiopia. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014;31(6):1217–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Balemie K., Kelbessa E., Asfaw Z. Indigenous medicinal plant utilization, management and threats in Fentalle area, Eastern Shewa, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Biol. Sci. 2004;3:37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Bekele H., Ahmed M.B. Ethno veterinary practices prevalent among livestock Rearers at Arbe Gona and Loka Abaya Woredas of Sidama zone of southern Ethiopia. Proc. Zool. Soc. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Bekalo T.H., Woodmatas S.D., Woldemariam Z.A. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in the Lowlands of Konta special Woreda, southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:5–26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekele G., Reddy P. Plants of Magada forest used in traditional management of human ailments by Guji Oromo Tribes in Bule Hora – Dugda Dawa districts, Borana zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Asian Acad. Res. J. Multidiscipl. 2014;1:202–221. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele-Tesemma A. REMA in ICRAF Project World Agroforestry Centre, East Africa Region; Nairobi, Kenya: 2007. Useful Trees and Shrubs of Ethiopia: Identification, Propagation and Management for 17 Agroclimatic Zone. [Google Scholar]

- Belayneh A., et al. Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-42. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatcha K. Review on herbal drug for TB/ethnopharmacology of tuberculosis. Int. J. Pharmacol. Res. 2013:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Birhan W., Giday M., Teklehaymanot T. The contribution of traditional healers' clinics to public health care system in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011;7:39–45. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birhane E., et al. Management, use and ecology of medicinal plants in the degraded drylands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J. Hortic. For. 2011;3:32–41. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Birhanu T., Abera D., Ejeta E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Selected Horro Gudurru Woredas, Western Ethiopia. J. Biol. Agric. Healthcare. 2015;5:2224–3208. www.iiste.org 1; (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) [Google Scholar]

- Bishaw M. Promoting traditional medicine in Ethiopia: a brief historical review of government policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991;33:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90180-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigden G., Nyang'wa B.T., du Cros P., Varaine F., Hughes J., et al. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Principles for Designing Future Regimens for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis; p. 92. 68-74. Bulletin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunalema L., Obakiro, Tabuti J.R.S., Waako P. Knowledge on plants used traditionally in the treatment of tuberculosis in Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekole G. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used against human ailments in Gubalafto District, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13 doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0182-7. 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawit A., Estifanos H. In: Plant Genetic Resources of Ethiopia. Engels J.M.M., Hawkes J.G., Worede M., editors. Cambridge University Press; 1991. Plants as a primary source of drugs in the traditional health practices of Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Desisa D. 2000. Uses and Conservation Status of Medicinal Plants Used by the Shinasha People.http://www.members.multimania.co.uk/ethiopianplants/index.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Desissa D., Binggeli P. 2000. Uses and Conservation Status of Medicinal Plantsused by the Shinasha People; pp. 1–10.http://www.mikepalmer.co.uk/woodyplantecology/ethiopia/shinasha.html [Google Scholar]

- d’Avigdor E., et al. The urrent status of knowledge of herbal medicine and medicinal plants in Fiche, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-38. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyew A., et al. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants in and around Fiche district, Central Ethiopia. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;6:154–167. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Etana B. ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES BIOLOGY DEPARTMENT Dryland Biodiversity Stream; 2015. Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants of Goma Wereda, Jima Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Fenetahun Y., Eshetu G. A review on ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants use by agro-pastoral communities in Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2017;5:33–44. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Firdessa R., et al. Mycobacterial lineages causing pulmonary and extrapulmonary Tuberculosis, Ethiopia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:460–463. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.120256. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FMOH . Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health; Addis Ababa: 2003. Assessment of the Pharmaceutical Sector in Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Fulas F. African Renaissance; London: 2007. The Role of Indigenous Medicinal Plants in Ethiopian Healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- Fullas F. Library Congress Cataloging; Iowa, USA: 2003. Spice Plants in Ethiopia: Their Culinary and Medicinal Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeyehu G. A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University. Addis Ababa University; 2011. An ethno botanical study of traditional use of medicinal plants and their conservation status in Mecha Wereda, west Gojjam zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Gedif T., Hahn H.J. The use of medicinal plants in self- care in rural central Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemechu A., et al. In vitro anti-mycobacterial activity of selected medicinal plants against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis Strains. Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-291. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genene B., Hazare S.T. Isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from medicinal plants of Ethiopia- A review. Curr. Trends Biomedical Eng. Biosci. 2017;7 5. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun A. 1976. Some Common Medicinal and Poisonous Plants Used in Ethiopian Folk Medicine.http://www.mrc.ac.za [Google Scholar]

- Getahun A. First Ethiopian Horticultural Workshop; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 1985. Developmental Anatomy of Tuber of Anchote; a Potential Dry Land Crop; pp. 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Getaneh S., Girma Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Debre Libanos Wereda, Central Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2013;8:366–379. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Geyid A., et al. Screening of some medicinal plants of Ethiopia for their anti-microbial properties and chemical profiles. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday M., et al. Medicinal plants of the Shinasha, Agew-awi and Amhara peoples in North west Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldu Z., Teklehaymanot T. Medicinal plant knowledge of the Bench ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical investigation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:24–34. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldu Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic groupof Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldu Z. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used by Sheko ethnic group of Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidey M., et al. Traditional medicinal plants used by Kunama ethnic group in Northern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2015:494–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gizachew E.Y., Giday M., Teklehaymanot T. Antimycobacterial activities of selected Ethiopian traditional medicinal plants used for treatment of symptoms of tuberculosis. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Med. Plants (GARJMP) 2013;2:22–29. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gonfa K., Tesfaye A., Ambachew D. Indigenous knowledge on the use and management of medicinal trees and shrubs in Dale district, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. A journal of plants, people and applied research. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2015;14:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G., Thakur B., Singh P., Singh H.B., Sharma V.D., Katoch V.M. Anti-tuberculosis activity of selected medicinal plants against multidrug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Indian J. Med. Res. 2010;131:809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M. Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Phytother Res. 2000;14:479–488. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<479::aid-ptr958>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostettmann K., et al. The potential of african medicinal plants as a source of drugs. Curr. Org. Chem. 2000;4:973–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Ibekwea N., et al. Some Nigerian anti-tuberculosis ethnomedicines: a preliminary efficacy assessment. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.059. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa A. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa: 2015. Ethno Medicinal Study of Plants in Jigjiga Woreda, Eastern Ethiopia: MSc Thesis/Pharmaceutics and Social Pharmacy ; School of Pharmacy. [Google Scholar]

- Jima T.T., Megersa M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in berbere district, bale zone of Oromia regional state, south east Ethiopia. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8602945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahaliw W. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa: 2016. Activity testing, toxicity assay and characterization of chemical constituents of medicinal plants used to treat tuberculosis in Ethiopian traditional medicine. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Kewessa G., Abebe T., Demessie A. Indigenous knowledge on the use and management of medicinal trees and shrubs in dale district, sidama zone, southern Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2015;14:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos H. Preliminary studies on medicinal plants and plant products in markets of central Ethiopia. Ethnomedizin. 1976;4:63–103. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos H., et al. Preliminary studies of traditional medicinal plants in nineteen markets in Ethiopia. Ethiop. Med. J. 1978;16:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legesse M., Ameni G., Mamo G., Medhin G., Bujne G., Abebe F. Knowledge of cervical tuberculosis lymphadenitis and its treatment in pastoral communities of the Afar region, Ethiopia. BMC Publ. Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-157. 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulekal E., et al. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu district, Southeastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A., et al. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous Flora for treating tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases in Niger state. Niger. J. Phytomed. Therapeut. 2007;12:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mann A., et al. Evaluation of in vitro antimycobacteria activity of Nigerian plants used for treatment of Respiratory Diseases. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008;7:1630–1636. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Megersa M., et al. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wayu Tuka district, East Welega zone of Oromia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:68. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin T., Debela H., Yehenew G. Survey of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Seka Chekorsa, Jimma zone Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2005;15 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin F., Demissew S., Teklehaymanot T. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago Woreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiolol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:28–34. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin K., Tekle G., Tesfay T. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used by indigenous people of Gemad district, northern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2013;1:32–37. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Moges A., Moges Y. Plant Science - Structure, Anatomy and Physiology in Plants Cultured in Vivo and in Vitro. IntechOpen; 2019. Ethiopian common medicinal plants: their parts and uses in traditional medicine - ecology and quality control. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan A., Sharma S.K. Side effects of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:882–888. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.169.7.952. 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., et al. Prefferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. The PRISMA group preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec I., et al. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants of northern Ethiopia. Bol. Latinoam Caribe Plant Med. Aromat. 2014;13:126–134. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Negussie B. University of Stockholm: PhD Thesis; 1988. Traditional Wisdom and Modern Development: A Case Study of Traditional Peri-Natal Knowledge Among Women in Southern Shewa,Ethiopia. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Obakiro S.B., Kiprop A., Kowino I., Kigondu E., Odero M.P., Omara T., Bunalema L. Ethnobotany, ethnopharmacology, and phytochemistry of traditional medicinal plants used in the management of symptoms of tuberculosis in East Africa: a systematic review. Trop. Med. Health. 2020;48 doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00256-1. 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Sbhatu B.D., Giday M. Medicinal plants used to manage human and livestock ailments in Raya Kobo district of Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2020;2020:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2020/1329170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regassa R. Assessment of indigenous knowledge of medicinal plantpractice and mode of service delivery in Hawassa city, southern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013;7:517–535. [Google Scholar]

- Regassa R., Bekele T., Megersa M. Ethnobotonical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human ailments by halaba people, southern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2017;5:36–47. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sabran S.F., Mohamed M., Abu Bakar M.F. Ethnomedical knowledge of plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis i n johor, Malaysia. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/2850845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifu T. Addis Ababa University; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2004. Ethnobotanical and Ethnopharmaceutical Studies on Medicinal Plants of Chifra District, Afar Region, of North-Eastern Ethiopia. M.Sc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Semenya S.S., Maroyi A. Medicinal plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis BY bapeditraditional healers in three districts of the limpopo province, South Africa. Afr. J. Tradit., Complementary Altern. Med. 2013;10:316–323. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i2.17. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui A.A., et al. Role of natural products in drug discovery process. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2014;6:172–204. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Singh B., et al. Plants as future source of anti-mycobacterial molecules and armour for fighting drug resistance. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2015;10:443–460. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Tabuti J.R., Kukunda C.B., Waako P.J. Medicinal plants used by traditional medicine practitioners in the treatment of tuberculosis and related ailments in Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.035. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefera B.N., Kim Y.D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama zone, southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019:15–25. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0302-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teka A., et al. Medicinal plant use practice in four ethnic communities (Gurage, Mareqo, Qebena,and Silti), south central Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020;16 doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00377-1. 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklay A., Abera B., Giday M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-65. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaymanot T. Ethnobotanical study of knowledge and medicinal plants use by the people in Dek Island in Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaymanot T. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal and edible plants of Yalo Woreda in Afar regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13 doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0166-7. 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaymanot T., Giday M. Quantitative ethnobotany of medicinalplants used by Kara and Kwego semi-pastoralist people in lower OmoRiver valley, Debub Omo zone, southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temam T., Dillo An Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of MirabBadwacho district, Ethiopia. J. Bio Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;5:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfahuneygn G., Gebreegziabher G. Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by Ethiopians: a review article. J. Genet. Genetic Eng. 2019;2:18–21. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tuasha N., Petros B., Asfaw Z. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers to treat malignancies and other human ailments in Dalle District, Sidama Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14 doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0213-z. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization) Vol. 1 and 2. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. (WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants). [Google Scholar]

- Wolde B., Gebre-Mariam T. Household herbal remedies for self-care in Addis Ababa:preliminary assessment. Ethiop. Pharmaceut. J. 2002;20:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wolditsadik M. Adami Tulu Jido Kombolcha District, Oromia, Ethiopia. School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology ; Haramaya University; Haramaya. Haramaya: 2018. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants. Msc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Wondimu T., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants around ‘Dheeraa’ town, Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worku A.M. A review on significant of traditional medicinal plants for human use in case of Ethiopia. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2019;10 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wube A.A., et al. Sesquiteroenes from Warburgia ugandensis and their antimycobacterial activity. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2309–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yineger H., Yewhalaw D. Traditional medicinal plant knowledge and use by local healers in Sekoru District, Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-24. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yineger H., et al. Plants used in traditional management of human ailments at bale mountains national park, southeastern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2008;2:132–153. [Google Scholar]

- Yirga G. Assessment of indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants in central zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2010;4:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zazueta-Beltran J., Leon-Sicairos N., Muro-Amador S., Flores-Gaxiola A., Velazquez-Roman J., Flores-Villasenor H., Canizalez-Roman A. Increasing drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Sinaloa, Mexico, 1997-2005. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;15:e272–e276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenebe M., Zerihun, Solomon Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in asgede Tsimbila district, Northwestern Tigray, northern Ethiopia G. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2012;10:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Zewdu B., Abyot E., Zewdineh S. An ethnomedicinal investigation of plants used by traditional healers of Gondar town, Northwestern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2015;3:36–43. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi M.I. Role of medicinal plants in healthcare in Africa and related issues: special emphasis to Ethiopia as an example. Int. Conf. Med. Plants. 2014 Kanyakumari, India. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.