Abstract

The roles of several trophic groups of organisms (methanogens and sulfate- and nitrate-reducing bacteria) in the microbial degradation of methanethiol (MT) and dimethyl sulfide (DMS) were studied in freshwater sediments. The incubation of DMS- and MT-amended slurries revealed that methanogens are the dominant DMS and MT utilizers in sulfate-poor freshwater systems. In sediment slurries, which were depleted of sulfate, 75 μmol of DMS was stoichiometrically converted into 112 μmol of methane. The addition of methanol or MT to DMS-degrading slurries at concentrations similar to that of DMS reduced DMS degradation rates. This indicates that the methanogens in freshwater sediments, which degrade DMS, are also consumers of methanol and MT. To verify whether a competition between sulfate-reducing and methanogenic bacteria for DMS or MT takes place in sulfate-rich freshwater systems, the effects of sulfate and inhibitors, like bromoethanesulfonic acid, molybdate, and tungstate, on the degradation of MT and DMS were studied. The results for these sulfate-rich and sulfate-amended slurry incubations clearly demonstrated that besides methanogens, sulfate-reducing bacteria take part in MT and DMS degradation in freshwater sediments, provided that sulfate is available. The possible involvement of an interspecies hydrogen transfer in these processes is discussed. In general, our study provides evidence for methanogenesis as a major sink for MT and DMS in freshwater sediments.

Microbial formation and degradation of the volatile organic sulfur compounds (VOSC) dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and methanethiol (MT) are thought to have a dramatic impact on the total flux of sulfur compounds in the atmosphere (18, 23). Kiene and Bates (14) demonstrated that the microbial degradation of DMS was far more important in affecting its concentration in water at the ocean surface than ventilation to the atmosphere. As a consequence of their importance, these microbial processes have been extensively studied in various systems, including marine, estuarine, salt marsh, and salt lake sediments or water layers, with respect to the microbial populations involved and the factors affecting them. In these systems, the catabolism of DMS and MT has been ascribed to various groups of bacteria, including aerobes (e.g., Thiobacillus and Methylophaga species) (5, 35–37) and anaerobes (anoxygenic phototrophs, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and methanogenic bacteria) (7, 17, 20, 24, 25, 28, 29, 34, 38), depending on the light intensity and the availability of oxygen or alternative electron acceptors (sulfate and nitrate).

In comparison with these high-salinity systems, the distribution of VOSC in freshwater systems has been less extensively described (1–3, 8, 9, 22, 26, 27, 31, 32). Although significant amounts of DMS and MT have been detected in freshwater systems (2, 3, 8, 9, 22, 31, 32), the microbial formation and degradation of VOSC in these environments have hardly been studied. The principal mechanisms of VOSC formation in freshwater environments appeared to be the methylation of H2S and MT to form MT and DMS, respectively (6, 16, 22), and to a lesser extent the formation of VOSC during the breakdown of sulfur-containing amino acids (12, 19, 39).

In most organic-rich freshwater sediments, the degradation of DMS and MT primarily occurs anaerobically, due to oxygen limitation (21). An extended survey of various freshwater sediments demonstrated that the degradation of DMS and MT effectively balanced the formation of these VOSC, resulting in low steady-state concentrations of these compounds in freshwater sediments (22). Zinder and Brock (40) demonstrated that DMS and MT were degraded anaerobically to methane, carbon dioxide, and H2S by methanogenic bacteria in slurries prepared from Lake Mendota sediment. In Sphagnum peat slurries, however, the role of methanogens in DMS and MT degradation remained unclear, since no net DMS consumption was recorded (16). In this study, we examined the degradation of DMS and MT in freshwater sediments in detail, with respect to the methanogenic population and other bacteria that can utilize DMS or MT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description and sampling.

Sediment samples were taken from ditches of a minerotrophic peatland (De Bruuk) and a eutrophic pond (on the campus of Dekkerswald Institute), both near Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Sulfate-rich freshwater sediment samples were collected from ditches at Zegveld, The Netherlands. Sediment samples were taken as described before (22).

Slurry incubations.

Bottles for slurry incubations were prepared and treated as described previously (22). Before the experiment was started the slurries were flushed with N2 or N2-CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]). Most experimental additions were made from pH-neutral stock solutions prepared in distilled water. These additions included bromoethanesulfonic acid (BES), sodium molybdate, sodium tungstate, sodium sulfate, sodium nitrate, DMS, MT, methanol, sodium acetate, and trimethylamine (TMA). An abiotic loss of MT or DMS was followed by the incubation of either sterilized sediment slurries (121°C for 20 min) or slurries amended with chloroform (final concentration, 500 μM). The sediment slurries (duplicates or triplicates) were incubated in the dark with or without shaking at 30°C.

Analytical procedures.

Gas samples (0.5 to 1.0 ml) taken from the incubation bottles with gastight syringes were analyzed for the presence of methane, MT, and DMS on a Hewlett-Packard model 5890 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and a Porapak Q (80/100 mesh) column (10). The specific determination of sulfur compounds (H2S, MT, and DMS) in gas samples of the incubations was done on a Packard model 438A gas chromatograph equipped with a flame photometric detector and a Carbopack B HT100 (40/60 mesh) column as described previously (4, 22). The dry weights of the sediment slurries were determined by drying them to a constant weight at 80°C. To determine the organic matter content, dried sediments were ashed for 4 h at 550°C. Sulfate and nitrate analyses were done according to the methods described by Roelofs (33).

RESULTS

Degradation of endogenous MT and DMS.

The conversion of endogenously produced MT and DMS to methane was investigated by the incubation of sediment slurries prepared from a eutrophic pond with or without the addition of BES. In incubations without BES, concentrations of MT and DMS remained low while methane accumulated to high levels in 15 days (330 μmol per bottle) at an accumulation rate of 36.7 nmol per ml of sediment slurry · h−1. Similar to previous findings (21, 22), the inhibition of methanogenesis by BES resulted in the accumulation of MT (55 μM) and small quantities of DMS (3.3 μM). Using the stoichiometry according to which 1 mol of DMS or 1 mol of MT results in the formation of 1.5 and 0.75 mol of methane, respectively (17), it was calculated that the methane arising from endogenous MT and DMS in these freshwater sediments makes up only a minor part (0.5%) of the total amount of methane produced.

Degradation of added DMS.

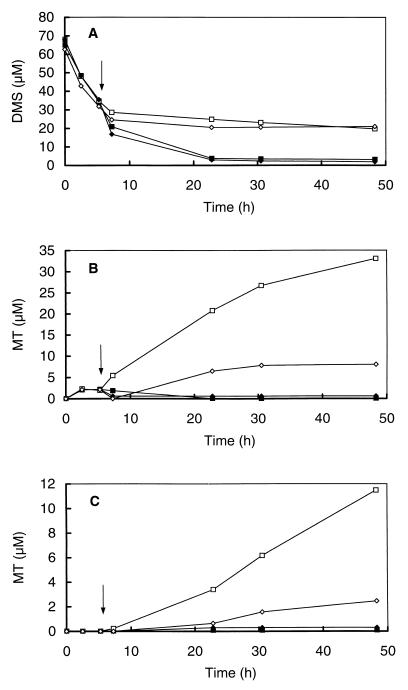

DMS added to the slurries of a eutrophic pond was rapidly consumed with some transient accumulation of MT (Fig. 1A and B). The conversion of DMS was inhibited by 95% by the addition of BES. MT accumulation in these incubations, which increased dramatically after the addition of BES, was not derived solely from endogenous substrates but was also derived from the conversion of the added DMS, since the level of MT accumulation in incubations which did not receive DMS was much lower (Fig. 1C). In contrast to BES addition, molybdate did not inhibit DMS degradation and even slightly stimulated MT and DMS degradation (Fig. 1A and B). Slurries without added DMS did not show any accumulation of MT upon the addition of molybdate, as was the case for BES-inhibited slurries (Fig. 1C). In contrast to BES inhibition, the combined inhibition of the DMS-amended slurries with BES plus molybdate resulted in a complete inhibition of DMS degradation (Fig. 1A). The level of MT accumulation in these incubations was lower than that in BES-inhibited slurries (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the level of MT accumulation in BES- or molybdate-inhibited slurries without the addition of DMS was also lower than that in slurries inhibited with BES alone (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Effects of several inhibitors on the degradation of DMS (A) and the formation of MT (B and C) in anoxic slurries prepared from the sediment of a eutrophic pond (on the campus of Dekkerswald Institute) after the addition of DMS (A and B) and without addition of DMS (C). Both DMS-amended slurries and slurries without DMS were incubated without inhibitor (control) (■) or with the addition of BES (□), molybdate (⧫), or molybdate plus BES (◊). The arrows indicate the times of the addition of the inhibitors (BES and molybdate).

Stoichiometry of DMS conversion.

To elucidate the stoichiometry of the DMS conversion in freshwater sediments, DMS was added to a slurry prepared from the sediment of Dekkerswald Pond. The DMS was added by pulse-wise additions of small amounts to avoid toxicity problems. Three subsequent additions of DMS had to be made to get a significant difference in the amount of methane produced from DMS compared with the (large) amount of methane produced from endogenous substrates. The total amount of added DMS (75 μmol) was converted to 112 μmol of methane (corrected for endogenous production). The amount of methane which can be calculated from the DMS added, by using the stoichiometry reported by Kiene et al. (17), is almost identical to the experimentally determined values.

Alternative methanogenic substrates.

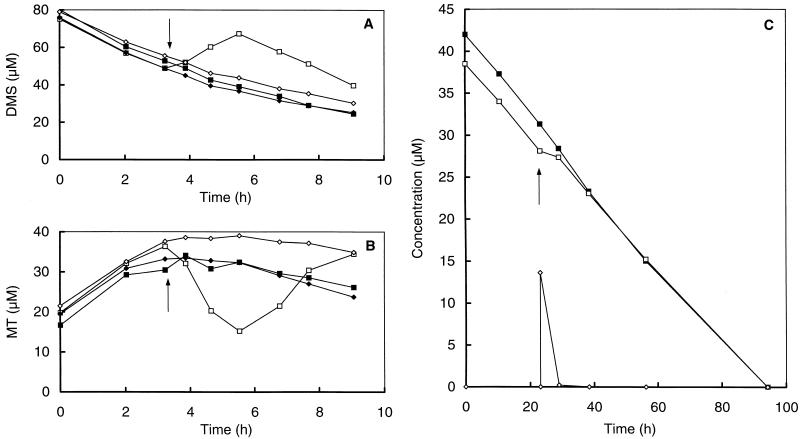

The effect of alternative methanogenic substrates on the degradation of MT and DMS by bacteria in freshwater sediments was tested by the addition of methanol (66 μM), TMA (66 μM), sodium acetate (66 μM), or MT (14 μM) to a DMS-degrading slurry. The degradation of DMS was not influenced by the addition of TMA and sodium acetate (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the addition of methanol had a dramatic impact on the degradation of DMS and MT. Directly after methanol addition, MT was rapidly converted, while at the same time a transient accumulation of DMS was observed (Fig. 2A and B). DMS degradation, coupled with MT formation, was restored to the original level 3 h after the addition of methanol. The addition of MT (14 μM) slightly decreased the degradation of DMS. DMS degradation was restored to the original rate after all MT had been converted (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Effects of the addition of alternative substrates on the transformation of DMS (A) and MT (B) in anoxic slurries prepared from a minerotrophic ditch in the De Bruuk peatland. At the times indicated by the arrows, DMS-amended slurries were pulsed with methanol (66 μM) (□), TMA (66 μM) (⧫), and sodium acetate (66 μM) (◊). Controls (■) were incubated without any further addition. (C) Effect of the addition of MT on the degradation of DMS. Shown are DMS concentrations in slurries without further addition (control) (■) and slurries with the addition of MT (14 μM) (□). For the latter incubations the MT concentrations (◊) are also shown.

Effect of sulfate on the degradation of endogenous DMS and MT.

Competition between sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic bacteria for DMS has been shown to occur in marine and estuarine environments which are rich in sulfate. To find out whether a similar competition takes place in freshwater systems, the roles of methanogenic bacteria and sulfate-reducing bacteria in the degradation of MT and DMS in sulfate-rich freshwater sediments were studied. Sediment slurries prepared from various sulfate-rich ditches were incubated without addition of a substrate to determine the in situ methane formation rates. The degradation of endogenously produced MT was analyzed by inhibition with BES, molybdate, or BES plus molybdate. Sulfate concentrations and formation rates of methane and MT of these incubations are given in Table 1. The slurry with the smallest amount of sulfate had the highest methane formation rate (Table 1, sample 4). The addition of BES to this slurry resulted in an inhibition of methanogenesis and an accumulation of MT. No accumulation of MT was found in the other three (sulfate-rich) slurries. Molybdate addition caused an increase of methanogenesis in all the sulfate-rich slurries (Table 1, samples 1 to 3), whereas methane formation in slurry 4 was slightly inhibited. In none of the slurries inhibited with molybdate was MT accumulation detected. As expected, slurries inhibited with BES plus molybdate showed a lower level of methane formation than the samples inhibited with molybdate alone. In contrast to incubations of sulfate-rich slurries with BES or molybdate addition or without addition (controls), incubations with BES plus molybdate added all showed a significant accumulation of MT, with MT accumulation rates all in the same order of magnitude (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effects of sulfate concentrations on the formation of methane and the degradation of MT in various sediment slurries prepared from freshwater ditches at Zegveld, The Netherlands

| Sample | SO42− (μM) | Formation rate (pmol/mg of organic matter · h−1)a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control

|

BES

|

Molybdate

|

BES + molybdate

|

||||||

| CH4 | MT | CH4 | MT | CH4 | MT | CH4 | MT | ||

| 1 | 1,783 | 4.2 | 0 | 2.6 | 0 | 108 | 0 | 12 | 0.21 |

| 2 | 1,780 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 55 | 0 | 23 | 0.20 |

| 3 | 1,825 | 9.8 | 0 | 3.4 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 17 | 0.19 |

| 4 | 549 | 175 | 0 | 36.5 | 0.46 | 105 | 0 | 27 | 0.12 |

Rates of methane and MT formation were calculated from time courses of duplicate bottles, with or without the addition of BES (25 mM), molybdate (20 mM), or BES (25 mM) plus molybdate (20 mM), and the formation rates are given in picomoles/milligram of organic matter · hour−1.

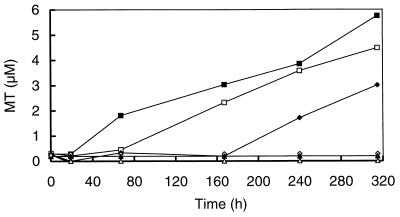

The impact of sulfate on the degradation of MT and DMS was studied in detail by the addition of sulfate to sediment slurries prepared from ditches in the De Bruuk peatland, in which methanogenesis was inhibited by BES. In incubations without additional sulfate, MT started to accumulate immediately after BES addition (Fig. 3). At first, no accumulation of endogenously produced MT was found in slurries with sulfate addition. However, in slurries amended with 0.5 or 1.0 mM sulfate, MT started to accumulate after 67 and 167 h of incubation (Fig. 3). Results of sulfate analysis showed that at that time sulfate was depleted. After termination of the experiment (550 h), MT also started to accumulate in slurries amended with a 2.5 mM concentration of sulfate (data not shown). Sulfate analysis revealed that at that time, sulfate concentrations in the slurries amended with 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 mM concentrations of sulfate had decreased to 0, 2.9, and 5.9 mM, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Time courses of endogenously produced MT in BES-inhibited (25 mM) sediment slurries prepared from a minerotrophic ditch in the De Bruuk peatland amended with sulfate to various final concentrations. Shown are slurries without sulfate (control) (■) and slurries amended with sulfate to final concentrations of 0.5 mM (□), 1.0 mM (⧫), 2.5 mM (◊), 5 mM (▴), and 7.5 mM (▵).

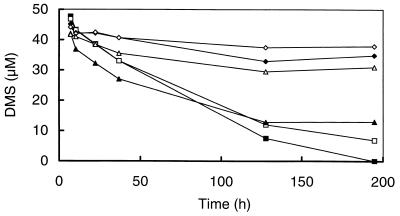

Effects of sulfate and H2 on the degradation of added DMS and MT.

The incubation of sediment slurries amended with MT or DMS demonstrated that the inhibition of MT and DMS degradation by BES could be reversed by the addition of sulfate (Fig. 4A and B). Consistent with the results of molybdate inhibitions mentioned above (Fig. 1), tungstate also slightly enhanced MT and DMS degradation (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

Effects of sulfate and various inhibitors on the degradation of DMS (A) and MT (B) in anoxic slurries prepared from a minerotrophic ditch in the De Bruuk peatland. Shown are the control (▴), sodium tungstate (4 mM) (▵), BES (⧫), BES plus sodium sulfate (1.5 mM) (◊), an abiotic control that was heated for 1.5 h (70°C) (■), and chloroform (500 μM) (□).

An alternative explanation for the effect of sulfate on the methane formation from DMS or MT is the occurrence of an interspecies transfer of reduction equivalents. According to this view, reducing equivalents, in the form of H2, are transferred from the DMS- or MT-degrading methanogen to the H2-consuming sulfate-reducing bacterium. This hypothesis was investigated by the incubation of slurries with the addition of DMS, DMS plus BES, and DMS plus BES and sulfate under an N2 or H2 gas phase. The degradation of added DMS ceased in slurries inhibited with BES (N2 and H2 gas phases). In accordance with the results discussed above, DMS degradation in slurries with BES and an N2 headspace was restored to the level of the controls by the addition of sulfate (Fig. 5). In incubations with BES plus sulfate, in which the N2 headspace was substituted with H2, however, the effect of sulfate on the DMS degradation was not found. After 120 h of incubation, DMS degradation in incubations with BES and sulfate (in N2) decreased and finally stopped completely (Fig. 5). Sulfate analysis of pore water of the sulfate-amended samples revealed that at that stage sulfate was completely converted (data not shown). Experiments with nitrate (instead of sulfate) gave similar results although at a different time scale. The complete degradation of the added DMS was achieved after more than 500 h.

FIG. 5.

Effects of sulfate and H2 headspace on the degradation of added DMS in BES-inhibited sediment slurries prepared from a minerotrophic ditch in the De Bruuk peatland. Shown are controls (■ and □), BES (⧫ and ◊), and BES plus sulfate (▴ and ▵). Closed symbols represent slurry samples incubated under an N2 headspace, and open symbols represent slurry samples incubated under an H2 headspace.

DISCUSSION

The microbial degradation of MT and DMS was studied in freshwater sediments, since these processes are known to be an important factor in determining the total flux of sulfur from these systems into the atmosphere (14, 18, 23). Sediment slurry experiments in previous studies had demonstrated that the formation of VOSC in freshwater sediment is well balanced by its (mainly anaerobic) degradation, resulting in low steady-state concentrations (21, 22). This study investigates the possible role of several groups of microorganisms (methanogens and sulfate- and nitrate-reducing bacteria) in the degradation of MT and DMS in freshwater sediments.

The use of specific inhibitors of methanogenic and sulfate-reducing bacteria in nonamended and DMS- or MT-amended freshwater sediment slurry incubations revealed that methanogens are the dominant DMS and MT utilizers in sulfate-poor freshwater systems. By conversion of these substances to methane these methanogens lower the concentrations of MT and DMS in situ as was also found before (21, 22). In contrast, in marine and estuarine environments the major part (80 to 90%) of the DMS is degraded by sulfate-reducing bacteria (13, 15, 17). The conversion of MT (and DMS) to methane in freshwater sediments represents less than 1% of the total amount of methane produced in situ, calculated by using the stoichiometry proposed by Kiene et al. (17). In marine or salt marsh systems, however, the conversion of DMS is a substantial part (28 to 40%) of the total methanogenic activity (13, 17).

BES inhibition appears to have more effect on the MT degradation than on the degradation of DMS. Similar results were published by Kiene et al. (17). These differences were also observed in slurry experiments in which MT and DMS were added. BES completely blocked MT degradation, whereas DMS degradation continued at a low rate (Fig. 4A and B). The reason for this difference remains unclear.

Since methanogens appeared to degrade almost all the DMS added, the stoichiometric formation of methane from DMS was investigated. In sediment slurries, which were depleted of sulfate, 75 μmol of DMS was converted to 112 μmol of methane. This is in accordance with the stoichiometry proposed by Kiene et al. (17), where 1 mol of DMS results in the formation of 1.5 mol of methane. Consequently, the 3:1 ratio of methane to carbon dioxide we found is much lower than the ratio of 14C-labelled methane and 14C-labelled carbon dioxide (>9:1) produced from 14C-labelled DMS mentioned in the only other study on the degradation of MT and DMS in freshwater sediments (40).

The addition of alternative substrates for methanogens to the DMS-degrading slurries at concentrations similar to that of DMS revealed that methanol and MT lowered the degradation rates for DMS (Fig. 2). This indicates that the methanogens in freshwater sediments, which degrade DMS, are also consumers of methanol and MT with an apparently slightly higher affinity for these substrates than for DMS. This is in accordance with the fact that most methanogens isolated on DMS are obligate methylotrophs (11, 17, 20, 24, 25, 28). This methylotrophic characteristic was confirmed by the observation that sodium acetate did not have any effect on DMS degradation. Surprisingly, however, TMA did not affect DMS degradation. This may be due to the fact that TMA is not a common substrate in freshwater sediments as is the case for marine and estuarine systems.

Competition between sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic bacteria for DMS has been shown to occur in marine and estuarine environments which are rich in sulfate (13, 17). To verify whether a similar competition also takes place in sulfate-rich freshwater systems, the effects of sulfate and inhibitors, like BES, molybdate, and tungstate, on the degradation of MT and DMS were studied. Sulfate-rich slurries reacted differently upon the addition of inhibitors compared to sulfate-poor slurries (Table 1). Whereas the degradation of endogenous MT in sulfate-poor slurries could be inhibited by BES alone, in sulfate-rich slurries this was realized only by a combined inhibition with BES plus molybdate. In sulfate-rich slurries in which methanogenic activity is inhibited by BES, endogenous MT is therefore likely to be degraded by sulfate-reducing bacteria into carbon dioxide and H2S. In the slurries inhibited with molybdate, methanogenesis was stimulated significantly compared to the controls, and in these incubations endogenous MT is likely to be degraded by methanogens (Table 1). The impact of sulfate on the degradation of endogenous MT was also clearly demonstrated by the addition of various concentrations of sulfate to sulfate-depleted sediment slurries in which methanogenesis was inhibited by BES. In these experiments MT accumulated only after the depletion of sulfate. In MT- or DMS-amended slurries, the inhibition of MT and DMS degradation by BES could be reversed by the addition of sulfate. The degradation rates of the sulfate-amended slurries, however, were lower than those of the controls. Furthermore, the degradation of the added MT and DMS in the sulfate-amended slurries stopped when sulfate was depleted. These results clearly demonstrate that besides methanogens, sulfate-reducing bacteria take part in MT and DMS degradation in freshwater sediments, provided that sulfate is available. Although this contribution of sulfate reducers to MT and DMS degradation is often mentioned in the literature, most attempts at the isolation of sulfate reducers on MT or DMS have been unsuccessful, except for an isolate which was obtained from a thermophilic anaerobic digester (34). Improved isolation techniques have shown that former unsuccessful isolations of bacteria from a certain inoculum often were caused by suboptimal culture conditions rather than by the absence of that species of bacteria from the inoculum. However, it is also possible that the contribution of sulfate reducers to the MT and DMS degradation occurs by cometabolism or by a facultative syntrophic metabolism between methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria. One of the possibilities is the occurrence of an interspecies H2 transfer between the DMS-degrading methanogen and the H2-consuming sulfate-reducing bacterium. An interspecies H2 transfer has been demonstrated to occur during the degradation of methanol by cocultures of Methanosarcina barkeri and Desulfovibrio vulgaris (30). Our results of sediment slurry incubations amended with BES or BES plus sulfate or nitrate, in which DMS degradation was inhibited under an H2 headspace, support a syntrophic interaction: sulfate reducers withdraw reducing equivalents (H2) from the DMS-degrading methanogens, forcing them to primarily oxidize the MT or DMS to carbon dioxide and H2S. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the effect of H2 is due to the preference of DMS-degrading nitrate or sulfate reducers for H2 over DMS as substrate. Nevertheless, the results of most of the studies published on the competition of methanogens and sulfate reducers for DMS and MT (13, 15, 17, 29, 40) can easily be explained by this transfer of H2 between DMS-degrading methanogens and H2-consuming bacteria, such as sulfate or nitrate reducers.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for methanogenesis as a major sink for MT and DMS in freshwater sediments. Further, the results are supportive, but not conclusively, for the occurrence of a syntrophic degradation of DMS by methanogens and sulfate- or nitrate-reducing bacteria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caron F, Kramer J R. Gas chromatographic determination of volatile sulfides at trace levels in natural freshwaters. Anal Chem. 1989;61:114–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Mello W Z, Hines M E. Application of static and dynamic enclosures for determining dimethylsulfide and carbonyl sulfide exchange in Sphagnum peatlands. J Geophys Res. 1994;99:14.601–14.607. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Mello, W. Z., and M. E. Hines. Emissions of dimethylsulfide from northern Sphagnum-dominated wetlands: controls on production and flux. Submitted for publication.

- 4.Derikx P J L, Op den Camp H J M, van der Drift C, van Griensven L J L D, Vogels G D. Odorous sulfur compounds emitted during production of compost used as a substrate in mushroom cultivation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:176–180. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.176-180.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Zwart J M M, Nelisse P N, Kuenen J G. Isolation and characterization of Methylophaga sulfidovorans sp. nov.: an obligate methylotrophic aerobic, DMS oxidizing bacterium from a microbial mat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;20:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finster K, King G M, Bak F. Formation of methyl mercaptan and dimethyl sulfide from methoxylated aromatic compounds in anoxic marine and freshwater sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;74:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finster K, Tanimoto Y, Bak F. Fermentation of methanethiol and dimethylsulfide by a newly isolated methanogenic bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:425–430. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henatsch J J, Jüttner F. Capillary gas chromatographic analysis of low-boiling organic sulphur compounds in anoxic lake-water by cryo-adsorption. J Chromatogr. 1988;445:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henatsch J J, Jüttner F. Occurrence and distribution of methane thiol and other volatile organic sulphur compounds in a stratified lake with anoxic hypolimnion. Arch Hydrobiol. 1990;119:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutten T J, de Jong M H, Peeters B P H, van der Drift C, Vogels G D. Coenzyme M derivatives and their effects on methane formation from carbon dioxide and methanol by cell extracts of Methanosarcina barkeri. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:27–34. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.27-34.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadam P C, Ranade D R, Mandelco L, Boone D R. Isolation and characterization of Methanolobus bombayenis sp. nov., a methylotrophic methanogen that requires high concentrations of divalent cations. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:603–607. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadota H, Ishida Y. Production of volatile sulfur compounds by microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1972;26:127–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.26.100172.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiene R P. Dimethyl sulfide metabolism in salt marsh sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1988;53:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiene R P, Bates T S. Biological removal of dimethyl sulfide from sea water. Nature. 1990;345:702–705. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiene R P, Capone D G. Microbial transformations of methylated sulfur compounds in anoxic salt marsh sediments. Microb Ecol. 1988;15:275–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02012642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiene R P, Hines M E. Microbial formation of dimethyl sulfide in anoxic Sphagnum peat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2720–2726. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2720-2726.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiene R P, Oremland R S, Catena A, Miller L G, Capone D G. Metabolism of reduced methylated sulfur compounds in anaerobic sediments and by a pure culture of an estuarine methanogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1037–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.1037-1045.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiene R P, Service S K. Decomposition of dissolved DMSP and DMS in estuarine waters: dependence on temperature and substrate concentration. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1991;76:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiene R P, Visscher P T. Production and fate of methylated sulfur compounds from methionine and dimethylsulfoniopropionate in anoxic salt marsh sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2426–2434. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2426-2434.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Boone D R, Choy C. Methanohalophilus oregonense sp. nov., a methylotrophic methanogen from an alkaline, saline aquifer. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomans B P, Op den Camp H J M, Pol A, Vogels G D. Anaerobic versus aerobic degradation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;65:438–443. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.438-443.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomans B P, Smolders A J P, Intven L M, Pol A, Op den Camp H J M, van der Drift C. Formation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4741–4747. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4741-4747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovelock J E, Maggs R J, Rasmussen R A. Atmospheric dimethyl sulfide and the natural sulfur cycle. Nature. 1972;237:452–453. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathrani I M, Boone D R, Mah R A, Fox G E, Lau P P. Methanohalophilus zhilinae sp. nov., an alkaliphilic, halophilic, methylotrophic methanogen. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:139–142. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-2-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni S, Boone D R. Isolation and characterization of a dimethyl sulfide-degrading methanogen, Methanolobus siciliae HI350, from an oil well, characterization of M. siciliae T4/MT, and emendation of M. siciliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:410–416. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nriagu J O, Holdway D A. Production and release of dimethyl sulfide from the Great Lakes. Tellus. 1989;41:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nriagu J O, Holdway D A, Coker R D. Biogenic sulfur and the acidity of rainfall in remote areas of Canada. Science. 1987;237:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4819.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oremland R S, Kiene R P, Whiticar M J, Boone D R. Description of an estuarine methylotrophic methanogen which grows on dimethylsulfide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:994–1002. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.4.994-1002.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oremland R S, Zehr J P. Formation of methane and carbon dioxide from dimethylselenide in anoxic sediments and by a methanogenic bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1031–1036. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.1031-1036.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelps T J, Conrad R, Zeikus J G. Sulfate-dependent interspecies H2 transfer between Methanosarcina barkeri and Desulfovibrio vulgaris during coculture metabolism of acetate or methanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:589–594. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.3.589-594.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards S R, Kelly C A, Rudd J W H. Organic volatile sulfur in lakes of the Canadian Shield and its loss to the atmosphere. Limnol Oceanogr. 1991;36:468–482. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards S R, Rudd J W M, Kelly C A. Organic volatile sulfur in lakes ranging in sulfate and dissolved salt concentration over five orders of magnitude. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:562–572. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roelofs J G M. Inlet of alkaline river water into peaty lowlands: effects on water quality and Stratiotes aloides L. stands. Aquat Bot. 1991;39:267–293. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanimoto Y, Bak F. Anaerobic degradation of methylmercaptan and dimethyl sulfide by newly isolated thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2450–2455. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2450-2455.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visscher P T, Quist P, van Gemerden H. Methylated sulfur compounds in microbial mats: in situ concentrations and metabolism by a colorless sulfur bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1758–1763. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1758-1763.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visscher P T, Taylor B F. A new mechanism for the aerobic catabolism of dimethyl sulfide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3784–3789. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3784-3789.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visscher P T, Taylor B F, Kiene R P. Microbial consumption of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in coastal marine sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeyer J, Eicher P, Wakeham S G, Schwarzenbach R P. Oxidation of dimethyl sulfide to dimethyl sulfoxide by phototrophic purple bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2026-2032.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinder S H, Brock T D. Methane, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide production from the terminal methiol group of methionine by anaerobic lake sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:344–352. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.344-352.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zinder S H, Brock T D. Production of methane and carbon dioxide from methane thiol and dimethyl sulfide by anaerobic lake sediments. Nature. 1978;273:226–228. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.344-352.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]