Abstract

Objective

Observational studies utilising diffusion tractography have suggested a common mechanism for tremor alleviation in deep brain stimulation for essential tremor: the decussating portion of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract. We hypothesised that directional stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract would result in greater tremor improvement compared to sham programming, as well as comparable improvement as more tedious standard-of-care programming.

Methods

A prospective, blinded crossover trial was performed to assess the feasibility, safety and outcomes of programming based solely on dentato-rubro-thalamic tract anatomy. Using magnetic resonance imaging diffusion-tractography, the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract was identified and a connectivity-based treatment setting was derived by modelling a volume of tissue activated using directional current steering oriented towards the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract centre. A sham setting was created at approximately 180° opposite the connectivity-based treatment. Standard-of-care programming at 3 months was compared to connectivity-based treatment and sham settings that were blinded to the programmer. The primary outcome measure was percentage improvement in the Fahn–Tolosa–Marín tremor rating score compared to the preoperative baseline.

Results

Among the six patients, tremor rating scores differed significantly among the three experimental conditions (P=0.030). The mean tremor rating score improvement was greater with the connectivity-based treatment settings (64.6% ± 14.3%) than with sham (44.8% ± 18.6%; P=0.031) and standard-of-care programming (50.7% ± 19.2%; P=0.062). The distance between the centre of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and the volume of tissue activated inversely correlated with the percentage improvement in the tremor rating score (R2=0.24; P=0.04). No significant adverse events were encountered.

Conclusions

Using a blinded, crossover trial design, we have shown the technical feasibility, safety and potential efficacy of connectivity-based stimulation settings in deep brain stimulation for treatment of essential tremor.

Keywords: Essential tremor, deep brain stimulation, dentato-rubro-thalamic tract

Introduction

With an estimated prevalence of 0.9%, essential tremor (ET) is the most common movement disorder worldwide. 1 First-line therapy is pharmacological but is only efficacious in 50% of patients. 2 Unfortunately, half of those with an initial response to medication will ultimately fail, 3 necessitating alternative treatment methods. Thalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS) is currently the most widely used surgical treatment for ET. Unfortunately, there continues to be variation in patient outcomes, lack of universal targeting approaches, and challenges with optimal device programming. 4

Recent observational studies exploring brain connectivity measured by means of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) tractography and functional MRI have suggested that stimulation of overlapping regions with connectivity to the cerebello-thalamo-cortical motor network may be responsible for a positive response to therapy.5–16 In particular, stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRTT) may be a common link between various debated targeting regions, such as the posterior subthalamic area versus the ventral thalamus. To date, there is limited prospective evidence to support the hypothesis of DRTT stimulation in ET. A few studies have prospectively utilised tractography for targeting assistance, but these studies were unblinded with small cohorts and lacked a control group to show superiority or equivalence to the current standard-of-care (SOC).5–7,17

An additional concern is the lack of consistency in target tracts. Due to difficulty in tracking the crossing fibres making up the bulk of the DRTT (decussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (dDRTT)), the minor fraction of this tract consisting of non-decussating fibres (non-decussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (ndDRTT)) is commonly used as a surrogate.5–9,17,18 Importantly, these tracts have a distinctly different anatomical distribution and may also have different physiological effects.19,20 As the DRTT traverses the posterior subthalamic area (PSA) through the ventral thalamus, it also moves further anteriorly, being closer to the ventral intermediate nucleus (Vim) in the PSA and more anterior along the border of Vim and ventralis oralis posterior (VOp) as it enters the ventral thalamus. This observation may underlie discrepancies in ‘ideal’ target location between studies using PSA and ventral thalamus targets. More ventral or PSA region stimulation is likely to be more closely related to the Vim compared to more dorsal thalamic stimulation likely being closer to the Vim/VOp region.10,11,13,21 Meanwhile, the ndDRTT generally lies more posterior and medial to the dDRTT, which is an important consideration when utilising these tracts as potential targets.

Based on existing observations of ‘sweet spots’ that seem to correlate more with the dDRTT axis than the ndDRTT, we hypothesised that stimulation directly targeting the dDRTT would result in greater tremor improvement compared to sham programming, as well as comparable tremor improvement as SOC without the need for tedious monopolar review and repeated programming sessions. We designed a prospective, blinded crossover trial as a pilot study to assess the feasibility, safety and outcomes of programming based solely on dDRTT anatomy. SOC programming for parameter optimisation was performed for the first 3 months, and was subsequently compared to targeted dDRTT stimulation and sham settings that were blinded to the programmer. The primary outcome measure was the percentage improvement in the Fahn–Tolosa–Marín tremor rating score (TRS) compared to the preoperative baseline.

Methods

Patients

This prospective clinical trial was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Verbal and written consent were obtained. Subjects were recruited from the Mayo Clinic Movement Disorders Neurology Clinic after decision to undergo unilateral Vim DBS for ET. Patients between 18 and 80 years of age were included and were ineligible if they had: (a) a contraindication to 3T MRI; (b) prior cranial surgery; (c) another movement or major neurological disorder; or (d) prior DBS or functional neurosurgery for ET treatment. Prior to surgery, a baseline TRS score was obtained.

Imaging

Prior to surgery, patients underwent MRI on a 3T Siemens Prisma (Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) scanner with high performance, 80 mT/m gradient system and 32-channel head coil. Patients’ heads were tightly packed in the head coil to minimise motion. Diffusion imaging was obtained using a multiband spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence. Relevant parameters included a repetition time (TR) of 2.89 s, echo time (TE) of 89 ms, flip angle of 78 degrees, receiver bandwidth of 2024 Hz/Px, with a multiband acceleration factor of 4 and 6/8 phase partial Fourier. The resolution was 1.6 × 1.6 × 1.6 mm. A total of 192 diffusion directions were asymmetrically sampled across three shells (b = 1000, 2000, and 3000 s/mm2) using an extrapolation of the electrostatic repulsion model to multishell space to provide uniform angular coverage. 22 The scan was performed with anterior-posterior phase encoding and repeated with posterior-anterior phase encoding for subsequent distortion correction, giving a total of 404 diffusion scans per subject. The total scan time for the diffusion sequences was 21 minutes. A standard magnetisation prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) scan that was optimised for grey–white matter contrast was also obtained at 1 × 1 × 1 mm for image co-registration.

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure was performed according to current standard practice, and tractography data were not used to aid in targeting. Tractography data were excluded from targeting to eliminate the subsequent impact on assessing current SOC programming. DBS implantation was performed contralateral to the side of the body expected to provide the most benefit to the patient. A Leksell Vantage headframe (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) was applied, and a stereotactic computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. The images were transferred to the planning workstation (Brainlab planning system) and co-registered to the patient’s preoperative MRI. The anterior commissure (AC), posterior commissure (PC), and mid-sagittal plane were identified. Using Guiot's relationships to target the Vim, an initial target was planned at the AC–PC level, one-fourth the AC–PC distance anterior to the PC. The initial lateral coordinate was the sum of one-half the width of the third ventricle plus 11.5 mm. With the patient in a semi-sitting position with 30 degree head elevation, the electrode was advanced through a burr hole to the target. For all patients, test stimulations were performed to evaluate tremor relief and thresholds for stimulation of the internal capsule, paresthesias, speech disturbances, or other adverse effects. Verification of the lateral coordinate was considered acceptable if transient stimulation was observed in the thumb, index finger, or corner of the mouth on the appropriate side. If we achieved good tremor control without adverse effects, no further attempt was made to use a different target. If the result was unsatisfactory, the stimulation electrode was moved according to the stimulation effect obtained. If high-frequency stimulation completely suppressed the tremor without adverse effects or with only slight and transient adverse effects, the stimulation electrode (Vercise Cartesia; Boston Scientific Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA) was secured to the cranium using a burr hole cap. Before and after this procedure, lateral radiographs were obtained to confirm the final electrode position and to correct for electrode movements.

Approximately 3 months after surgery, high-resolution CT was obtained using a dual-energy protocol (80 kV and 150 kV) with an in-plane resolution of 0.5 × 0.5 mm and slice thickness of 0.4 mm.

Imaging data processing

The T1 MPRAGE was initially processed through the ‘fsl_anat’ pipeline implemented in the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) v6.0.3 (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk). Subsequently, segmentation was performed using FreeSurfer v7.1.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). The diffusion data underwent eddy current correction, slice-to-volume movement correction, and outlier replacement in FSL ‘eddy_cuda’ on a custom-built Linux workstation utilising three NVIDIA Quadro P5000 graphics processing units (GPUs).

Susceptibility-induced distortions can introduce substantial variation in spatial localisation in diffusion-weighted imaging. The majority of existing studies on tractography in DBS targeting fail to account for such distortions, which can produce spatial mislocalisation in the range of several millimeters. In the current study, distortion correction was performed using FSL ‘topup’. This approach utilises repeat acquisitions in opposing phase-encode directions to estimate the susceptibility-induced field and correct the distortion, which has been shown to be superior to registration-based methods and field-mapping techniques. 23

Orientation distribution functions were estimated using FSL ‘BEDPOSTX_GPU’ to model three fibre orientations per voxel. The T1 MPRAGE was co-registered to the diffusion data using a boundary-based registration implemented in FreeSurfer. The region of interest (ROI) for the primary motor cortex was derived from FreeSurfer and thalamic masks from FSL FIRST. Manual ROIs were created for the dentate nucleus and superior cerebellar peduncle. The exclusion mask consisted of the ventricles and the contralateral hemisphere white matter. Probabilistic tractography of the dDRTT was created using a seed region in the contralateral dentate nucleus with waypoints from the ROIs of the contralateral superior cerebellar peduncle, ipsilateral thalamus and ipsilateral primary motor cortex. The probabilistic streamline maps were normalised by dividing by the total number of streamlines.

Stimulation modelling

The preoperative MPRAGE images were co-registered to the postoperative CT in Lead-DBS v2.3.2 (http://www.lead-dbs.org) 24 then normalised to MNI_ICBM_ 2009b_NLIN_ASYM space, 25 as previously described.26–28 Automated electrode localisation was performed using precise and convenient electrode reconstruction for DBS (PaCER) 29 and electrode orientation determined using the directional orientation detection (DiODe) algorithm. 30 Registration and electrode localisation results were verified by a board-certified neuroradiologist experienced in DBS. A volume of tissue activated (VTA) was estimated using a finite element method (FEM)-based model in Lead-DBS.24,31 An E-field was estimated on a tetrahedral mesh including a two-tissue compartment (grey and white matter), insulating components and electrode contacts. Conductivities of 0.09 S/m and 0.06 S/m were used for grey and white matter, respectively. The E-field distribution was estimated with a modified FieldTrip-SimBio pipeline implemented in Lead-DBS with VTA shape based on a typical threshold of value greater than 0.2 V/mm.32,33

Connectivity-based settings

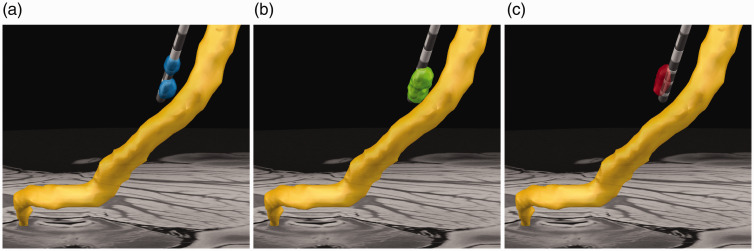

To determine the test stimulation settings, the normalised probabilistic tractography maps were thresholded to leave a single voxel per slice representing the slicewise point of greatest DRTT probability. For the connectivity-based treatment (CBT) setting, directional stimulation was utilised oriented towards the point of greatest DRTT probability to generate the closest proximity or overlap by the VTA as achievable within a maximum stimulation current of 4 mA. The sham setting was generated using directional steering to approximately 180 degrees from the treatment setting (Figure 1). Similar current was utilised unless there was anticipated intersection with the internal capsule. The pulse width and frequency were maintained at the same SOC setting for the connectivity-based setting tests. The radiologist generating the test settings was blinded to any clinical information, programming history, or SOC settings.

Clinical testing

Clinical assessments, including SOC programming, testing procedures and TRS scoring, were conducted by the same programmer, who was blinded to all imaging information. Medications were maintained at preoperative baseline. All patients were initially programmed using current standard clinical programming methods and optimised over 3 months. At approximately 3 months, each patient underwent a testing visit for the three test programming settings: SOC, CBT and sham. Patients arrived on current SOC settings and TRS was obtained. After a 1-hour washout period with DBS OFF, the first test setting was applied and TRS repeated. Another 1-hour washout period ensued with DBS OFF before the second test setting was administered and TRS measured. Any side effects were also recorded. The sham versus treatment settings were randomised, and the programmer was blinded to any knowledge of the imaging results or which setting was sham or CBT.

Imaging analysis

For each patient, the euclidean distance between the slicewise voxel of highest dDRTT probability and the closest VTA voxel was calculated for all stimulation conditions (SOC vs. CBT vs. sham). Linear regression was performed to assess the relationship of the dDRTT distance and the percentage improvement in TRS.

To compare differences among the group, the VTAs and probabilistic tract maps were normalised to MNI_ICBM_2009b_NLIN_ASYM space. The normalised VTAs were all summed for each stimulation condition. The ‘centre of gravity’ (COG) for the summed VTAs was calculated using the ‘cluster’ feature of FSL to determine the peak overlap in VTAs for each stimulation condition. Normalised stimulation information was compared to a group-averaged dDRTT map by averaging each patient’s normalised probabilistic tract map. The approximated location of Vim was also displayed using the DBS intrinsic atlas (DISTAL) 34 for illustration purposes.

Statistics

Demographic data were expressed as mean, range and standard deviation (SD), as appropriate. The primary outcome measure was the absolute percentage change in the TRS. The percentage changes for the three conditions (SOC, CBT and sham) were computed relative to the baseline rating. Friedman’s test, which is a non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) model for data that is used for studies with repeated measures under different conditions on the same person, was used to test for differences among the three conditions. Post hoc tests between conditions were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. As an additional means of summarising the data, the magnitude of percentage changes across the conditions was compared within person to determine if a larger change from baseline was found with CBT versus sham or SOC versus sham. No correction for multiple testing was applied to reported P values. Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.2.

Results

General

Eight patients in total were enrolled prior to termination due to the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Two patients were unable to return for the clinical testing visit, leaving a total of six patients. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. All patients had uneventful surgery with no complications. The final electrode position for all subjects is shown in Figure 1. All electrodes produced satisfactory intraoperative macrostimulation on the original target trajectory except one, which achieved satisfactory macrostimulation after advancing 3 mm in depth. Follow-up imaging revealed one electrode to be more anterior within the VOp. Programming parameters for all tested settings are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information for the cohort.

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | Handedness | Baseline TRS | SOC TRS | CBT TRS | Sham TRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | F | Right | 36 | 12 | 14 | 19 |

| 2 | 77 | M | Right | 24 | 15 | 10 | 19 |

| 3 | 69 | F | Right | 28 | 17 | 9 | 15 |

| 4 | 52 | F | Right | 38 | 21 | 15 | 26 |

| 5 | 72 | F | Right | 47 | 31 | 24 | 25 |

| 6 | 71 | M | Right | 33 | 6 | 3 | 8 |

CBT: connectivity-based treatment setting; F: female; M: male; SOC: standard-of-care; TRS: Fahn–Tolosa–Marín tremor rating score.

Figure 1.

Example stimulation settings. Coronal view of the decussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (dDRTT; yellow) is shown relative to final electrode position and volumes of tissue activated (VTAs). (a) The standard-of-care VTA (blue) is shown for reference. (b) Connectivity-based treatment (CBT) VTA (green) is directionally oriented towards the dDRTT. (c) The sham VTA (red) is directionally oriented near 180 degrees from the CBT setting away from the dDRTT. The standard-of-care VTA was similarly oriented in direction as the CBT setting, but further in proximity from the tract.

Outcomes

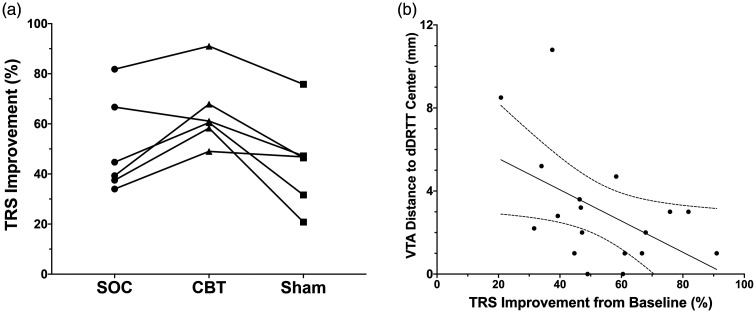

TRS improvement for each patient is shown in Figure 3(a). The TRS scores were found to differ significantly among the three experimental conditions (P=0.030). The mean TRS improvement was significantly greater with the CBT settings (64.6% ± 14.3%) than with sham (44.8% ± 18.6%; P=0.031). CBT was also superior to optimised SOC programming (50.7% ± 19.2%; P=0.062) at 3 months. In five of six patients (83.3%), the CBT setting was superior to the SOC setting. The CBT setting also had greater TRS improvement than the sham setting in all patients (100%). The SOC setting was superior to sham in four of six patients (66.7%).

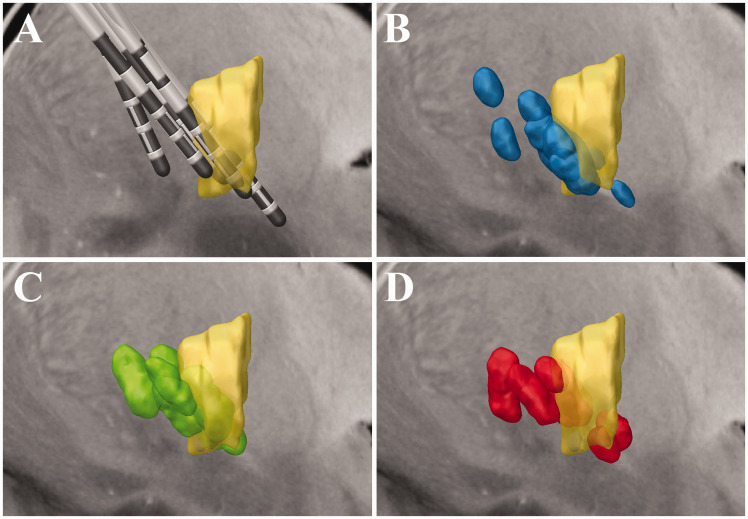

Figure 2.

(a) Sagittal image showing the location of all electrodes relative to the ventral intermediate nucleus (Vim) (yellow), as defined in the deep brain stimulation intrinsic atlas (DISTAL). (b) Group volumes of tissue activated (VTAs) relative to Vim (yellow) for the standard-of-care programming settings (b; blue), connectivity-based treatment (CBT) setting (c; green) and sham settings (d; red).

Image quality

All patients successfully completed the MRI session. MPRAGE scans were free of visible motion artifact and adequate for segmentation. The diffusion data were within acceptable limits for quality, with a group average of 1.22% ± 1.8% outlier volumes per scan leaving an average of 399/404 diffusion volumes per patient.

Imaging analysis

In agreement with the hypothesis, the distance between the centre point of the dDRTT and the nearest VTA margin inversely correlated with the percentage improvement in TRS (Figure 3(b); R2 = 0.24; P = 0.04).

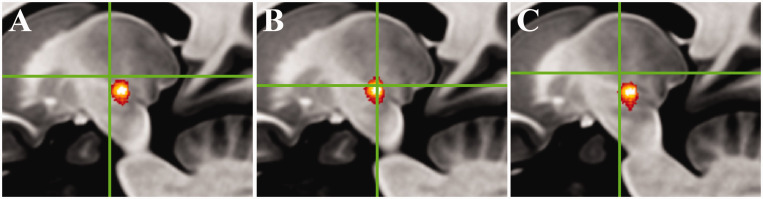

Results for the VTA COG analysis are shown in Figure 4. The COG for the SOC settings was located at Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) = –14/–14.5/0.5, which was 1 mm medial, 4 mm anterior and 3 mm superior (5.1 mm euclidean distance) from the CBT COG (MNI = –15/–18.5/–2.5). The sham COG was located at MNI = –13/–15/1.5 – closer to the SOC COG (1.5 mm euclidean distance) than to the CBT COG (5.7 mm euclidean distance).

Figure 3.

(a) Improvement in Fahn–Tolosa–Marín tremor rating score (TRS) for each patient with standard-of-care (SOC) programming, connectivity-based treatment (CBT) and sham setting. (b) Linear regression and 95% confidence interval of the distance from volume of tissue activated (VTA) to the central, maximal probability voxel of the decussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (dDRTT) and percentage improvement in TRS (R2 = 0.24; y = −0.08x + 7.1; P = 0.04).

Adverse effects

Three patients experienced mild, transient paresthesia with the test settings (one with sham setting, one with CBT setting, and one with both settings) that quickly dissipated. One patient experienced sustained mild paresthesia with the CBT setting. No additional adverse effects or significant adverse events were encountered.

Figure 4.

Sagittal images with green crosshairs showing the peak centre-of-gravity (COG) of volumes of tissue activated (VTAs) relative to the group average decussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (dDRTT; red-orange heat map) for the (a) standard-of-care (SOC) setting, (b) connectivity-based treatment (CBT) setting and (c) sham setting. The CBT setting COG lies within the central portion of the dDRTT, while the SOC and sham settings are generally more anterior and superior.

Discussion

In this pilot trial, we show that programming settings based solely on directionally targeting the dDRTT produced greater tremor improvement than sham settings, providing further evidence of dDRTT modulation in tremor control for ET. In addition, we show a trend for greater improvement in TRS with CBT programming versus the more tedious SOC programming process at the 3-month interval, suggesting that time to optimisation may be improved by the CBT approach. Expert programming capabilities are not universally available and are a major contributor to poor patient outcomes. 4 The ability to provide informed programming settings as a starting point for DBS programmers has the potential both to improve outcomes, decrease time to achieve ideal outcomes and reduce patient and practitioner burden for tedious monopolar reviews.

The DRTT is the main component of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical motor network and travels from the cerebellar dentate nucleus through the ipsilateral superior cerebellar peduncle, partially decussates in the midbrain, traverses through the PSA, ventral thalamus and terminates in the primary motor cortex. The DRTT consists of two components, the dDRTT (approximately 80% of fibres) and the ndDRTT (approximately 20% of fibres).20,35 Despite only representing a minority of the DRTT, many studies have used the ndDRTT as a marker for the DRTT due to technical challenges (discussed below) in modelling the crossing fibres of the dDRTT. Importantly, these two components have variation in their anatomical spatial relationship. Although more coherently organised through much of the subthalamic region, they further diverge on approach to the ventral thalamus. Although existing in a gradient, the dDRTT generally lies more anterior and related to Vim/VOp, while the ndDRTT is generally more posterior and medial with closer relationship to Vim.19,20 This spatial gradient may partly explain existing discrepancies regarding greater tremor improvement with more anterior ventral thalamus stimulation (nearer VOp)13,36,37 compared to more posterior PSA stimulation (nearer Vim).10,11 Regardless, the lack of consistency in prior studies, as well as a preponderance of studies using the minor ndDRTT as a marker of the DRTT, has created challenges in converging findings. To date, no definite evidence exists to show a differential physiological effect between ndDRTT and dDRTT.

Multiple prior retrospective and observational studies have supported the role of direct DRTT stimulation.5–9,11,13–18,38 Unfortunately, there is great variability in the methods and outcomes of these studies. The technique of DRTT tracking has previously been called into question, particularly related to the robustness of diffusion encoding and angular resolution due to limited sampling, limited spatial resolution, outdated single-tensor models, lack of adequate distortion correction that plagues echo-planar imaging techniques and limitations of various tracking methods. Examples include studies by Coenen et al. that used diffusion techniques ranging from 32 to 61 diffusion directions with a single b-value (b=1000 s/mm2), 2 mm isotropic voxel size and no advanced distortion correction.5–9,17 Middlebrooks et al. acquired 1.6 mm isotropic voxels with 64 diffusion directions at a b-value of 1000 s/mm2, but without distortion correction.13 Other studies ranged from 12 to 60 diffusion directions with a single b-value (b = 1000 s/mm2), limited or no distortion correction, and voxel sizes generally 2 mm isotropic or non-isotropic voxel sizes.14–16,39 Previously, the most robust approach was by Akram et al. using a 1.5 mm isotropic resolution, 128 diffusion directions, a b-value of 1500 s/mm2 and utilised reverse phase-encoded acquisitions to estimate the susceptibility-induced off-resonance field and correct distortions in the diffusion data. 11 To our knowledge, our study utilises the most robust tracking approach employed to date in DRTT targeting. We combined a multishell approach (b = 1000, 2000 and 3000 s/mm2) with a total of 192 diffusion directions acquired at a high spatial resolution (1.6 mm isotropic) on a high-performance MRI gradient system (80 mT/m). Multishell data have a more robust sampling of q-space and have been shown to account better for non-Gaussian diffusion microstructures. As a result, multishell acquisitions have greater precision in modelling fibre orientation and higher reproducibility compared to single-shell acquisitions. 40 Finally, we acquired the images in reverse phase-encode directions for distortion correction. These distortions, importantly, can have a substantial impact on DBS targeting. In our patient cohort, we measured anatomical distortions in the region of the ventral thalamus as much as 2 mm in the phase-encode direction prior to correction.

The tracking methods in prior studies have also been quite variable. A majority have utilised deterministic methods that are known to be less reliable for tracking crossing fibres and fibres that traverse grey matter structures, such as the thalamus.11,18 Probabilistic tracking has far greater sensitivity for detecting complex fibre geometry at the cost of increased false fibres.41,42 These false fibres can be reduced by more accurate acquisition methods, constraint to known anatomical pathways and a greater number of measured streamlines, which comes at the cost of increased computational power. With modern GPU technology, however, such processing techniques can be performed in a matter of minutes to hours. We have shown that this approach can be used to perform such probabilistic tracking with extremely high angular and spatial resolution data within a clinically feasible timeframe (<8 hours).

Our results are in line with previously published retrospective and observational studies that have found increasing stimulation proximity to the DRTT corresponds to greater tremor improvement.5–11,14–17 We also found that stimulation modelling based solely on directional stimulation of the dDRTT was equivalent or superior to SOC programming at 3 months. Although the study cohort is small, our results support the safety and therapeutic potential of this approach. Our connectivity-based settings were superior in all but one case to the more tedious and systematic ‘trial and error’ approach and monopolar review used in SOC programming. One important note is that additional modification of the experimental programming settings by the programmer was not allowed under the trial design, which may allow additional flexibility to maximise tremor control and minimise adverse effects using our approach. While we do not envision that connectivity-based programming will eliminate human expertise, the insights provided by our methods will allow the programmer to have a starting point with a high probability of success that can subsequently be modified with less time and effort. In addition, the increasing utilisation of leads with directional current steering allows a nearly infinite level of programming settings to test without guidance to narrow the scope of test settings. Our methods may allow maximisation of the technology by providing a structural stimulation target with a high degree of precision.

The COG for the three different programming settings was considerably different. The CBT setting was 4 mm posterior and 3 mm inferior to the SOC setting. Nevertheless, those settings for which the VTAs were more spatially related (closer to dDRTT) did indeed result in a similar degree of tremor improvement. Interestingly, Al-Fatly et al. proposed a hypothetical DBS ‘sweet spot’ in one of the most comprehensive evaluations of connectivity data in DBS for ET using normative group connectome data, which was concordant with our results. 10 Our final, normalised COG for the CBT setting was located at MNI = –15/–18.5/–2.5, less than 2 mm from their proposed target at MNI = –16/–20/–2, both of which lie in the area of greatest probability of the normalised dDRTT tracts in our cohort. The convergence of these findings further supports the role of the dDRTT in modulating tremor control.

Several limitations of our study are noteworthy. First, the small size of the study population limits interpretation of the statistical comparisons. Nevertheless, this blinded, sham clinical trial of tractography-based programming provides preliminary data on the technical feasibility, safety and efficacy of connectivity-based programming to guide and power future clinical trials. Second, as connectivity data were not used to influence targeting, some electrodes were not ideally positioned to stimulate the dDRTT maximally. However, our pilot results provide both safety and efficacy information that may justify the incorporation of dDRTT tractography into the surgical targeting itself for future trials. Third, while the limitations of diffusion tractography are well known – particularly related to modelling of crossing fibres, distortion and anatomical precision – we have attempted to address these issues by utilising the most robust, subject-specific diffusion scheme in DRTT clinical studies to date. Fourth, assessment at 3 months limits the understanding of long-term effects with the various tested settings and could also still potentially be contaminated by a persistent thalamotomy effect. Finally, the accuracy of VTA modelling using FEM-based approaches is variable but represents a reasonable approximation and directionality of stimulation volumes. 11

Conclusion

Using a blinded, crossover trial design, we have shown the technical feasibility, safety and potential efficacy of connectivity-based stimulation settings in DBS for the treatment of ET. By using directional stimulation targeting the dDRTT, defined by a robust diffusion tractography protocol, we found greater improvement in tremor compared to sham and SOC programming. Such techniques may reduce the burden on DBS programmers by providing some insight into potential ‘ideal’ settings rather than sole reliance on monopolar review and random macrostimulation testing. Finally, given the increasing interest in ‘asleep’ DBS or cases without microelectrode recording, our technique may allow improvement in initial DBS targeting. Larger trials will be needed to confirm the efficacy of connectivity-guided programming.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-neu-10.1177_19714009211036689 for Directed stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: a blinded clinical trial by Erik H Middlebrooks, Lela Okromelidze, Rickey E Carter, Ayushi Jain, Chen Lin, Erin Westerhold, Ashley B Peña, Alfredo Quiñones-Hinojosa, Ryan J Uitti and Sanjeet S Grewal in The Neuroradiology Journal

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-neu-10.1177_19714009211036689 for Directed stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: a blinded clinical trial by Erik H Middlebrooks, Lela Okromelidze, Rickey E Carter, Ayushi Jain, Chen Lin, Erin Westerhold, Ashley B Peña, Alfredo Quiñones-Hinojosa, Ryan J Uitti and Sanjeet S Grewal in The Neuroradiology Journal

Acknowledgements

The author(s) are grateful for the assistance of Alaine Keebaugh, Kendra Brown, Duane Morrow and Amy Grassle. The author(s) are also thankful to Sonia Watson, for assistance with editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) disclosed the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: EHM receives unrelated research support from Boston Scientific Corp. and Varian Medical Systems, Inc. and is a consultant for Boston Scientific Corp. and Varian Medical Systems, Inc. SSG is a consultant for Boston Scientific Corp. and Medtronic Inc. AQH is supported by the Mayo Clinic Professorship and a clinician investigator award, a Florida State Department of Health research grant and the Mayo Clinic Graduate School as well as National Institutes of Health grants (R43CA221490, R01CA200399, R01CA195503 and R01CA216855).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this research was supported by a Mayo Clinic Transform the Practice award (principal investigator: EHM).

ORCID iDs

Erik H Middlebrooks https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4418-9605

Lela Okromelidze https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1296-0522

References

- 1.Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord 2010; 25: 534–541. doi:10.1002/mds.22838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thanvi B, Lo N, Robinson T. Essential tremor-the most common movement disorder in older people. Age Ageing 2006; 35: 344–349. doi:10.1093/ageing/afj072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis ED, Rios E, Henchcliffe C. How are we doing with the treatment of essential tremor (ET)?: persistence of patients with ET on medication: data from 528 patients in three settings. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 882–884. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02926.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okun MS, Tagliati M, Pourfar M, et al. Management of referred deep brain stimulation failures: a retrospective analysis from 2 movement disorders centers. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1250–1255. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.8.noc40425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coenen VA, Allert N, Madler B. A role of diffusion tensor imaging fiber tracking in deep brain stimulation surgery: DBS of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRT) for the treatment of therapy-refractory tremor. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011; 153: 1579–1585. doi:10.1007/s00701-011-1036-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coenen VA, Sajonz B, Prokop T, et al. The dentato-rubro-thalamic tract as the potential common deep brain stimulation target for tremor of various origin: an observational case series. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020; 162: 1053–1066. doi:10.1007/s00701-020-04248-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coenen VA, Varkuti B, Parpaley Y, et al. Postoperative neuroimaging analysis of DRT deep brain stimulation revision surgery for complicated essential tremor. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017; 159: 779–787. doi:10.1007/s00701-017-3134-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coenen VA, Allert N, Paus S, et al. Modulation of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network in thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosurgery 2014; 75: 657–669. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coenen VA, Madler B, Schiffbauer H, et al. Individual fiber anatomy of the subthalamic region revealed with diffusion tensor imaging: a concept to identify the deep brain stimulation target for tremor suppression. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 1069–1075. doi:10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820a1a20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Fatly B, Ewert S, Kubler D, et al. Connectivity profile of thalamic deep brain stimulation to effectively treat essential tremor. Brain 2019; 142: 3086–3098. doi:10.1093/brain/awz236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akram H, Dayal V, Mahlknecht P, et al. Connectivity derived thalamic segmentation in deep brain stimulation for tremor. NeuroImage Clin 2018; 18: 130–142. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middlebrooks EH, Holanda VM, Tuna IS, et al. A method for pre-operative single-subject thalamic segmentation based on probabilistic tractography for essential tremor deep brain stimulation. Neuroradiology 2018; 60: 303–309. doi:10.1007/s00234-017-1972-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middlebrooks EH, Tuna IS, Almeida L, et al. Structural connectivity-based segmentation of the thalamus and prediction of tremor improvement following thalamic deep brain stimulation of the ventral intermediate nucleus. NeuroImage Clin 2018; 20: 1266–1273. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenoy AJ, Schiess MC. Deep brain stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract: outcomes of direct targeting for tremor. Neuromodulation 2017; 20: 429–436. doi:10.1111/ner.12585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenoy AJ, Schiess MC. Comparison of tractography-assisted to atlas-based targeting for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor. Mov Disord 2018; 33: 1895–1901. doi:10.1002/mds.27463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthofer JM, Steib K, Lange M, et al. Distance between active electrode contacts and dentatorubrothalamic tract in patients with habituation of stimulation effect of deep brain stimulation in essential tremor. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2017; 78: 350–357. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1597894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coenen VA, Rijntjes M, Prokop T, et al. One-pass deep brain stimulation of dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and subthalamic nucleus for tremor-dominant or equivalent type Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158: 773–781. doi:10.1007/s00701-016-2725-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sammartino F, Krishna V, King NK, et al. Tractography-based ventral intermediate nucleus targeting: novel methodology and intraoperative validation. Mov Disord 2016; 31: 1217–1225. doi:10.1002/mds.26633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen KJ, Reid JA, Chakravorti S, et al. Structural and functional connectivity of the nondecussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract. Neuroimage 2018; 176: 364–371. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.04.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Middlebrooks EH, Domingo RA, Vivas-Buitrago T, et al. Neuroimaging advances in deep brain stimulation: review of indications, anatomy, and brain connectomics. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020; 41: 1558–1568. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A6693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Middlebrooks EH, Grewal SS, Holanda VM. Complexities of connectivity-based DBS targeting: Rebirth of the debate on thalamic and subthalamic treatment of tremor. NeuroImage Clin 2019; 22: 101761. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caruyer E, Lenglet C, Sapiro G, et al. Design of multishell sampling schemes with uniform coverage in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 2013; 69: 1534–1540. doi:10.1002/mrm.24736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham MS, Drobnjak I, Jenkinson M, et al. Quantitative assessment of the susceptibility artefact and its interaction with motion in diffusion MRI. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0185647. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horn A, Li N, Dembek TA, et al. Lead-DBS v2: towards a comprehensive pipeline for deep brain stimulation imaging. Neuroimage 2019; 184: 293–316. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonov V, Evans AC, Botteron K, et al. Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. Neuroimage 2011; 54: 313–327. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Middlebrooks EH, Grewal SS, Stead M, et al. Differences in functional connectivity profiles as a predictor of response to anterior thalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for epilepsy: a hypothesis for the mechanism of action and a potential biomarker for outcomes. Neurosurg Focus 2018; 45: E7. doi:10.3171/2018.5.FOCUS18151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Middlebrooks EH, Lin C, Okromelidze L, et al. Functional activation patterns of deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. World Neurosurg 2020; 136: 357–363 e2. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okromelidze L, Tsuboi T, Eisinger RS, et al. Functional and structural connectivity patterns associated with clinical outcomes in deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus internus for generalized dystonia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020; 41: 508–514. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A6429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husch A, Petersen MV, Gemmar P, et al. PaCER – a fully automated method for electrode trajectory and contact reconstruction in deep brain stimulation. NeuroImage Clin 2018; 17: 80–89. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellerbach A, Dembek TA, Hoevels M, et al. DiODe: directional orientation detection of segmented deep brain stimulation leads: a sequential algorithm based on CT imaging. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2018; 96: 335–341. doi:10.1159/000494738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horn A, Reich M, Vorwerk J, et al. Connectivity predicts deep brain stimulation outcome in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 2017; 82: 67–78. doi:10.1002/ana.24974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astrom M, Diczfalusy E, Martens H, et al. Relationship between neural activation and electric field distribution during deep brain stimulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015; 62: 664–672. doi:10.1109/TBME.2014.2363494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vorwerk J, Oostenveld R, Piastra MC, et al. The FieldTrip-SimBio pipeline for EEG forward solutions. Biomed Eng Online 2018; 17: 37. doi:10.1186/s12938-018-0463-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewert S, Plettig P, Li N, et al. Toward defining deep brain stimulation targets in MNI space: a subcortical atlas based on multimodal MRI, histology and structural connectivity. Neuroimage 2018; 170: 271–282. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meola A, Comert A, Yeh FC, et al. The nondecussating pathway of the dentatorubrothalamic tract in humans: human connectome-based tractographic study and microdissection validation. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 1406–1412. doi:10.3171/2015.4.JNS142741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim W, Sharim J, Tenn S, et al. Diffusion tractography imaging-guided frameless linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgical thalamotomy for tremor: case report. J Neurosurg 2018; 128: 215–221. doi:10.3171/2016.10.JNS161603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pouratian N, Zheng Z, Bari AA, et al. Multi-institutional evaluation of deep brain stimulation targeting using probabilistic connectivity-based thalamic segmentation . J Neurosurg 2011; 115: 995–1004. doi:10.3171/2011.7.JNS11250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlaier J, Anthofer J, Steib K, et al. Deep brain stimulation for essential tremor: targeting the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract? Neuromodulation 2015; 18: 105–112. doi:10.1111/ner.12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pineda-Pardo JA, Martinez-Fernandez R, Rodriguez-Rojas R, et al. Microstructural changes of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract after transcranial MR guided focused ultrasound ablation of the posteroventral VIM in essential tremor. Hum Brain Mapp 2019; 40: 2933–2942. doi:10.1002/hbm.24569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong Q, He H, Gong T, et al. Reproducibility of multi-shell diffusion tractography on traveling subjects: a multicenter study prospective. Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 59: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlaier JR, Beer AL, Faltermeier R, et al. Probabilistic vs. deterministic fiber tracking and the influence of different seed regions to delineate cerebellar-thalamic fibers in deep brain stimulation. Eur J Neurosci 2017; 45: 1623–1633. doi:10.1111/ejn.13575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petersen MV, Lund TE, Sunde N, et al. Probabilistic versus deterministic tractography for delineation of the cortico-subthalamic hyperdirect pathway in patients with Parkinson disease selected for deep brain stimulation. J Neurosurg 2017; 126: 1657–1668. doi:10.3171/2016.4.JNS1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-neu-10.1177_19714009211036689 for Directed stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: a blinded clinical trial by Erik H Middlebrooks, Lela Okromelidze, Rickey E Carter, Ayushi Jain, Chen Lin, Erin Westerhold, Ashley B Peña, Alfredo Quiñones-Hinojosa, Ryan J Uitti and Sanjeet S Grewal in The Neuroradiology Journal

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-neu-10.1177_19714009211036689 for Directed stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: a blinded clinical trial by Erik H Middlebrooks, Lela Okromelidze, Rickey E Carter, Ayushi Jain, Chen Lin, Erin Westerhold, Ashley B Peña, Alfredo Quiñones-Hinojosa, Ryan J Uitti and Sanjeet S Grewal in The Neuroradiology Journal