Abstract

The ruminal anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens OR79 produces a bacteriocin-like activity demonstrating a very broad spectrum of activity. An inhibitor was isolated from spent culture fluid by a combination of ammonium sulfate and acidic precipitations, reverse-phase chromatography, and high-resolution gel filtration. N-terminal analysis of the isolated inhibitor yielded a 15-amino-acid sequence (G-N/Q-G/P-V-I-L-X-I-X-H-E-X-S-M-N). Two different amino acid residues were detected in the second and third positions from the N terminus, indicating the presence of two distinct peptides. A gene with significant homology to one combination of the determined N-terminal sequence was cloned, and expression of the gene was confirmed by Northern blotting. The gene (bvi79A) encoded a prepeptide of 47 amino acids and a mature peptide, butyrivibriocin OR79A, of 25 amino acids. Significant sequence homology was found between this peptide and previously reported lantibiotics containing the double-glycine leader peptidase processing site. Immediately downstream of bvi79A was a second, partial open reading frame encoding a peptide with significant homology to proteins which are believed to be involved in the synthesis of lanthionine residues. These findings indicate that the isolated inhibitory peptides represent new lantibiotics. Results from both total and N-terminal amino acid sequencing indicated that the second peptide was identical to butyrivibriocin OR79A except for amino acid substitutions in positions 2 and 3 of the mature lantibiotic. Only a single coding region was detected when restriction enzyme digests of total DNA were probed either with an oligonucleotide based on the 5′ region of bvi79A or with degenerate oligonucleotides based on the predicted sequence of the second peptide.

The rumen has a complex microbial community which includes bacteria, archaea, protists, and fungi (14). The ruminal bacterial population is predominantly composed of obligate anaerobes, among which Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens is an important and frequently isolated species (4, 34). B. fibrisolvens isolates are small, motile, curved rods with tapered ends; they produce butyric acid as the major fermentation end product and stain gram negative (12). Although currently classified as gram-negative bacteria (12), analyses of both cell wall structure (6) and 16S rRNA gene sequences (8, 39) indicate that butyrivibrios are in fact gram positive, falling within cluster XIV of the greater clostridial assemblage (39). Furthermore, both DNA-DNA hybridization (22) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing indicate that these isolates are more phylogenetically diverse than the current single-species designation suggests (8, 39).

Previously, we demonstrated bacteriocin-like inhibitory activity among a large proportion of B. fibrisolvens isolates obtained from diverse ruminal sources (18). The inhibitory peptide from one isolate (B. fibrisolvens AR10) was isolated and characterized, and the gene encoding the peptide was cloned and sequenced (19). Butyrivibriocin AR10 is a type IIc bacteriocin (24) that demonstrates significant homology to acidocin B, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus (21). The isolated bacteriocin demonstrated a wide spectrum of activity against Butyrivibrio isolates but a relatively limited spectrum of activity against other genera (18). Several of the B. fibrisolvens isolates previously examined, grouping into a common 16S rRNA cluster, exhibited inhibitory activity demonstrating much broader spectra of activity, not only against Butyrivibrio isolates but also against an assortment of gram-positive ruminal bacteria and against a number of Listeria strains.

Here, we report on the isolation and characterization of the broad-spectrum inhibitor produced by one of these Butyrivibrio isolates, B. fibrisolvens OR79. Our findings suggest that this isolate produces two new, closely related lantibiotics: butyrivibriocins OR79A and OR79B. The structural gene encoding one of these lantibiotics, bvi79A, was cloned and sequenced and its transcription was evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures and growth conditions.

All cultures were maintained as glycerol stocks at −20°C. B. fibrisolvens OR79, which was from our collection, was originally isolated from the rumen of a dairy cow. Routine sensitivity testing was carried out with B. fibrisolvens OB156 as the indicator strain. OB156 was originally isolated from the rumen of a deer and was obtained from R. Forster (Lethbridge Research Centre, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada). Routine culturing was carried out with L-10 medium (5) containing glucose, maltose, and soluble starch (each at 0.2% [wt/vol]). For isolation of the bacteriocin from liquid cultures, the growth medium was supplemented with additional glucose (2.0% [wt/vol]). For growth of non-Butyrivibrio isolates, cellobiose (0.2% [wt/vol]) was routinely included in the medium. These strains and their sources were as previously listed (18). Cultures were grown in an anaerobic hood with an atmosphere of CO2-H2 (90:10) at 37°C.

Activity assays.

Levels of inhibitory activity at each step of the purification were assayed by the critical dilution method (35), with activity (in units per milliliter) being defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution demonstrating inhibition of the test organism when 10 μl of the dilution was spotted on an overlay containing the indicator organism (18). The indicator organism used was B. fibrisolvens OB156, and the dilution buffer consisted of Tris-buffered saline (100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Tween 20 at this level has no inhibitory effect on Butyrivibrio isolates (18). The spectrum of activity was determined by spot testing 10 μl of a 10−1 dilution of the isolated peptide(s) (fraction IV; see the next section) on an overlay seeded with the test organism.

Isolation of butyrivibriocin OR79.

L-10 medium (1.0 liter) supplemented with additional glucose (2% [wt/vol]) was inoculated with 10 ml of a fresh overnight culture of B. fibrisolvens OR79 grown in standard L-10 medium. Cultures were incubated at 37°C without agitation for 2 days. Tween 20 was then added directly to the culture to a final concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol), and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min). The spent-culture supernatant was saturated with ammonium sulfate (60 g/100 ml) and mixed at room temperature for 1 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 30 min). The pellet was resuspended in 200 ml of distilled, deionized water (dH2O), and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 30 min). The clarified supernatant was retained and the pellet was discarded. The resulting supernatant is referred to as fraction I.

The 10 to 40% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate cut was precipitated from fraction I as described above, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 100 ml of dH2O. Insoluble material was removed by high-speed centrifugation (100,000 × g, 30 min). The supernatant was acidified to pH 3.3 by dropwise addition of 1.0 M HCl, and the insoluble material was removed by high-speed centrifugation (100,000 × g, 30 min). The resulting supernatant was retained and the pellet was discarded. The supernatant was neutralized with 1.0 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and washed by using a 100-ml flow cell (Amicon Corp.) fitted with a membrane with a molecular mass cutoff of 3 kDa. The retentate was washed until the filtrate exhibited no significant absorbance (determined at 280 nm). The retentate was concentrated to a final volume of 13 ml and subjected to a high-speed centrifugation (100,000 × g, 30 min), and the pellet was discarded. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter and stored at 4°C until required. This material is referred to as fraction II.

The bacteriocin-like activity was purified by fast protein liquid chromatography, using a combination of reverse-phase and gel filtration chromatography. Briefly, 0.5-ml aliquots of fraction II were subjected to reverse-phase chromatography on a Resource RPC 3.0-ml column (Pharmacia, Baie d’Urfé, Quebec, Canada). Solvent phases A and B consisted of dH2O-acetonitrile (95:5 and 5:95, respectively) with 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA). Samples were eluted from the column with a linear acetonitrile gradient (from 5 to 70%). The column eluate was monitored at 206 nm and assayed for activity by spot testing on a lawn of sensitive bacteria. The fraction with the highest activity was neutralized by the addition of 3.0 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), dried with a rotary evaporator, and dissolved in 6 M guanidine-HCl. The peak fractions from four separate runs were combined (100 μl total volume). This material was designated fraction III.

Fraction III was dried down with a rotary evaporator, dissolved in 6 M guanidine-HCl, and subjected to high-resolution gel filtration on a Superdex Peptide HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia). The mobile phase consisted of 40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water and 0.1% TFA. The column eluate was monitored at 206 nm, and 0.5-ml fractions were collected and assayed for activity as described above. A single active peak (fraction IV) was recovered from the column eluate. Fraction IV was characterized by gel electrophoresis, amino acid analysis, and N-terminal amino acid sequencing.

Gel electrophoresis.

The purity of the isolated bacteriocin was evaluated by Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2). Gels (10% acrylamide) were silver stained for visualization of the peptides.

N-terminal and amino acid analysis.

N-terminal sequencing and total amino acid analysis were carried out on fraction IV. No precautions were taken to protect either cysteine or tryptophan residues in the amino acid analysis, nor were standards included for the detection of modified amino acid residues. The analysis was carried out in the laboratory of M. Yaguchi, National Research Council, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

DNA and RNA isolations.

For the isolation of genomic DNA, cells from a 100-ml overnight culture were pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of a lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA, 1% (wt/vol) SDS, and 10 μg of proteinase K/ml, and the cell suspension was incubated at 60°C. Following completion of digestion (4 to 6 h), 1.0 ml of 7 M ammonium acetate (pH 7) was added and the mixture was extracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (75:20:5). The aqueous phase was extracted a second time, with chloroform only. Genomic DNA was precipitated from solution by the addition of two volumes of ice-cold ethanol, and the precipitate was recovered by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min). The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and dried under a vacuum. One milliliter of a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, and 10 μg of RNase A/ml was added to the pellet, and the mixture was held at room temperature for 24 h to dissolve the DNA pellet. Plasmid DNA isolation and in vitro DNA manipulations were carried out according to the procedures of Sambrook et al. (33).

Total cellular RNA was isolated from 20 ml of liquid culture following overnight growth. In each case, cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) under anaerobic conditions. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1.0 ml of sterile L-10 medium, and the suspension was transferred into a stoppered serum centrifuge tube that had previously been equilibrated under anaerobic conditions. The tube was sealed by the use of a rubber septum and crimp seal, and the anaerobic cell suspension was placed on ice. A 2.0-ml volume of a solubilization buffer consisting of 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5% (wt/vol) SDS, and 1 mM EDTA was added to the tube by the use of a needle and syringe, and the contents were rapidly mixed by using a vortex mixer. A 2.0-ml volume of acidic phenol, previously equilibrated with 0.02 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), was added, the contents were again mixed, and the suspension was incubated for 5 min at 60°C. The aqueous phase was recovered by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), reextracted with acidic phenol-chloroform (50:50) at 60°C for 5 min, and subjected to a final extraction with chloroform only. Total RNA was precipitated from the solution by the addition of 2 volumes of ethanol and overnight incubation at −20°C. RNA was stored in 100% ethanol at −20°C until required. Northern blotting of isolated RNA was carried out by the method of Rosen et al. (32).

Cloning and sequence analysis.

Cloning of a gene encoding a bacteriocin was carried out with two different mixed-oligonucleotide probes to identify homologous sequences, one (5′-ATTTCTCATGARTGTTCTATGAAT-3′) based on both the determined N-terminal sequence and the N-terminal regions of previously reported homologous lantibiotic sequences (NH2-ISHECSMN-COOH) and the second (5′-TTYGTWTTYACYTGCTGCTCWTAA-3′) based on the C termini of the previously reported homologous lantibiotic sequences (NH2-FVFTCCS-COOH). Probes were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (222 TBq/mmol; New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.) by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (33). In both instances, hybridization and washing of the blots were carried out under low-stringency conditions (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], room temperature) (at higher stringency these probes did not hybridize with DNA digests). Under these conditions, both probes hybridized to a number of restriction fragments. These included a common 4.7-kb region of an EcoRI genomic-DNA digest. The 4.7-kb region was purified from a gel and shotgun cloned into pGEM7zf(−) (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). Recombinants were selected from the partial library by using the C-terminus-based mixed oligonucleotide and sequenced in both directions.

Search for homologous genes.

In an attempt to identify any homologous gene sequences within the genome, restriction enzyme-digested chromosomal DNA was hybridized against oligonucleotide probes based on the nucleic acid sequence of the cloned bvi79A gene and on other possible sequences coding for the predicted and determined peptide sequences. The probe 5′-CTCGTGGCTGATTGTGTTGATGAC-3′ was an exact match for the gene sequence coding for the predicted Bvi79A (butyrivibriocin OR79A) sequence NH2-VIKTISHEC-COOH. This probe was also used for determination of bvi79A expression by Northern blotting of isolated cellular RNA. The degenerate oligonucleotides 5′-TGYCAYATGAAYACITGGCAR-3′ and 5′-GGICARCCIGTIATIAARACIATI-3′ encoded the amino acid sequences NH2-CHMNTWQ-COOH (amino acids 34 to 40 of the predicted peptide [see Fig. 2B]; common to both peptide sequences) and NH2-GQPVIKTI-COOH (amino acids 1 to 8 of the determined sequence [see Fig. 2B]; specific for the predicted sequence of the second peptide at the second and third amino acid positions). Southern blots were hybridized at 38°C overnight and washed under either low-stringency (5× SSC-0.1% SDS, 38°C, 60 min) or high-stringency (1× SSC–0.1% SDS, Tm − 2°C, 60 min) conditions.

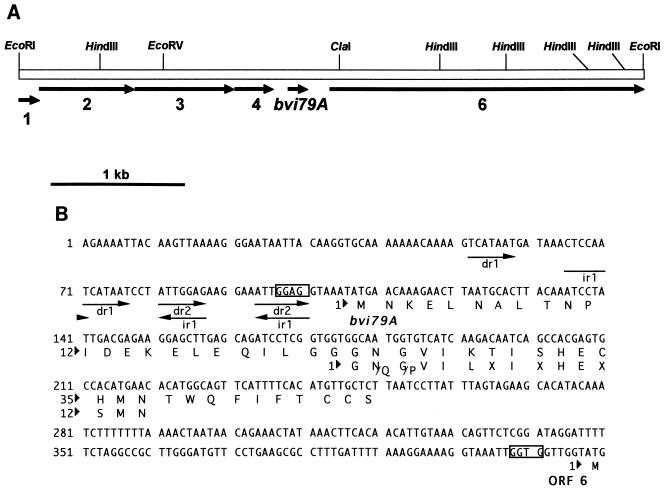

FIG. 2.

(A) Graphic representation of the nucleotide sequence of the 4,731-nucleotide EcoRI fragment containing the butyrivibriocin OR79A (bvi79A) gene. Other ORFs are identified by number. (B) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences for the butyrivibriocin OR79A gene (bvi79A). Putative ribosome binding sites are boxed. The determined N-terminal sequence is illustrated directly below the predicted amino acid sequence encoded by bvi79A. Residues designated by an X represent blank cycles. The locations of direct repeats (dr) and inverted repeats (ir) are indicated by arrows below the nucleotide sequence.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of bvi79A and the other open reading frames (ORFs) indicated in Fig. 2A has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF062647.

RESULTS

Purification of butyrivibriocin OR79.

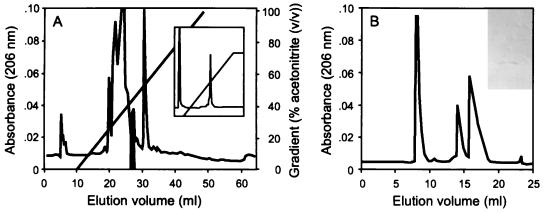

An inhibitor produced in liquid culture was isolated by a combination of ammonium sulfate and acidic precipitations followed by reverse-phase chromatography (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The major inhibitory activity present in fraction II eluted from the reverse-phase column as a single peak (fraction III) (Fig. 1A) at approximately 40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. Fraction III eluted as a single peak at the same acetonitrile concentration on rechromatography (Fig. 1A, inset). Significant activity (approximately 75% of the total activity) was lost during the reverse-phase chromatography step (Table 1). A second, minor inhibitory component eluted from the reverse-phase column at approximately 35% (vol/vol) acetonitrile (data not shown). No enhancement of activity, in terms of improved titer, above that found with only fraction III was evident when the two fractions were recombined. No further characterization or fractionation of the minor inhibitory component was carried out.

FIG. 1.

Isolation of butyrivibriocin OR79. (A) Reverse-phase chromatograph of fraction II. The area under the peak containing the inhibitory activity, which was taken as fraction III, is filled in black. (Inset) Rechromatography of the active peak (fraction III). (B) High-resolution gel filtration of fraction III. The identities of the peaks, in order of elution, are as follows: butyrivibriocin (taken as fraction IV), unknown, and guanidine-HCl. (Inset) Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of fraction IV, showing the single silver-stained band which ran at the buffer front of the gel.

TABLE 1.

Purification of butyrivibriocin OR79

| Fraction | Total vol (ml) | Total activitya | Total A280b | Sp actc | Relative sp act | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant | 1,000 | 1.6 × 106 | 4,800 | 333 | 1 | 100 |

| I | 200 | 1.3 × 106 | 800 | 1,625 | 4.9 | 81 |

| II | 13 | 3.3 × 105 | 127 | 2,600 | 7.8 | 21 |

| III | 13 | 8.2 × 104 | 1.7 | 4.8 × 104 | 144 | 5 |

| IV | 13 | 8.2 × 104 | 0.8 | 1.0 × 105 | 300 | 5 |

Activity (units per milliliter) × total volume.

Absorbance at 280 nm × total volume.

Total activity/total A280.

Silver staining of a Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel on which was run a sample of fraction III revealed no distinct protein band. Instead, fraction III stained as a low-molecular-weight smear (results not shown). When dried down, fraction III was found to consist of an oily residue. No additional components contained within fraction III could be resolved through alterations to the conditions used in the reverse-phase chromatography. High-resolution gel filtration of fraction III, however, demonstrated the presence of an additional, inactive component (Fig. 1B). Inhibitory activity resided in the major peak only (fraction IV), which passed through the gel near the molecular weight cutoff for the gel filtration column. Silver staining of fraction IV indicated the presence of a single peptide of less than 3,000 molecular weight running at the gel buffer front (Fig. 1B, inset). Fraction IV was subjected to both N-terminal and total amino acid analyses.

Total recovered yields (Table 1) amounted to 5% of the total activity originally present in fraction I.

Spectrum of activity.

To confirm that the inhibitor originally detected by the use of an indirect plating assay was the same as the purified inhibitor (fraction IV), the spectrum of activity on a selected number of Butyrivibrio and ruminal isolates was evaluated (Table 2). Sensitivities determined by drop testing with fraction IV were, in most cases, similar to those determined with the deferred antagonism plating assay (Table 2) (18). Several isolates (B. fibrisolvens OR36, B. fibrisolvens OR37, B. fibrisolvens OB146, B. fibrisolvens VV1, and Lachnospira multiparus D25e) which were originally resistant in the indirect plating assay were found to be sensitive to the purified inhibitor. In addition, three isolates (B. fibrisolvens OB251, B. fibrisolvens ATCC 19171, and Streptococcus bovis B-b-3) which were sensitive by the indirect plating assay (18) were negative when tested with fraction IV by a drop test.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivities of selected butyrivibrios and ruminal isolates in indirect assays and spot tests

| Isolateb | Sensitivity determined bya:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Indirect assayc | Spot testd | |

| B. fibrisolvens OR02 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OR35 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OR36 | − | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OR37 | − | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OR76 | − | − |

| B. fibrisolvens OB145 | − | − |

| B. fibrisolvens OB146 | − | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OB150 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OB192 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OB194 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OB235 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens OB251 | + | − |

| B. fibrisolvens AR10 | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens ATCC 19171 | + | − |

| B. fibrisolvens H10b | + | + |

| B. fibrisolvens VV1 | − | + |

| Butyrivibrio crossotus ATCC 29175 | + | + |

| Clostridium clostridiforme ATCC 25537 | + | + |

| Lachnospira multiparus D25e | − | + |

| Lachnospira multiparus ATCC 19207 | + | + |

| Lactobacillus leichmanii ATCC 4797 | − | − |

| Ruminococcus flavefaciens OR18 | + | + |

| Selenomonas ruminantium OB268 | − | − |

| Streptococcus bovis ATCC 33317 | + | + |

| Streptococcus bovis B-b-3 | + | − |

| Megashaera elsdenii ATCC 17752 | NDe | − |

+, isolate was sensitive to the indicated inhibitor; −, isolate was not sensitive to the indicated inhibitor.

Sources of strains are as previously reported (18).

Indirect plate assay, as previously reported (18).

Spot tested (35) with 6 U (10 μl of a 10−1 dilution) of fraction IV.

ND, not determined.

N-terminal and amino acid analysis.

N-terminal analysis of fraction IV yielded 15 amino acid residues (G/V-N/Q/I-G/P/L-V-I-L-H-I/E-X-H-E-X-S-M-N-). Positions 1 and 8 contained two different amino acid residues, and positions 2 and 3 contained three different amino acid residues. There were significant differences in the peak heights of the triple-residue positions and at a number of single-residue positions. It was realized that a minor component, consisting of a homologous peptide in which the first three amino acid positions were deleted (V-I-L-X-I-X-H-E-X-H-), was present within the sample. The corrected N-terminal sequence was G-N/Q-G/P-V-I-L-X-I-X-H-E-X-S-M-N-, indicating the presence of at least two major homologous peptides. No amino acid residue was detected at three positions within the N terminus (positions 7, 9, and 12), and the sequence abruptly terminated at position 15, indicating a blockage at this residue. Results of the total amino acid analysis of fraction IV are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence determined by analysis of fraction IV with the predicted amino acid composition of FibA

| Residue | No. of residues in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Fraction IV | FibA | |

| Asp/Asn | 2 | 2 |

| Glu/Gln | 2 | 2 |

| Ser | 1 | 2 |

| Gly | 2 | 2 |

| His | 2 | 2 |

| Thr | 0 | 3 |

| Ala | 0 | 0 |

| Pro | 1 | 0 |

| Tyr | 0 | 0 |

| Val | 1 | 1 |

| Met | 1 | 1 |

| Ile | 2 | 3 |

| Phe | 2 | 2 |

| Lys | 1 | 1 |

| Leu | 0 | 0 |

| Cys | NDa | 3 |

| Trp | ND | 1 |

ND, not determined.

Cloning of butyrivibriocin OR79A.

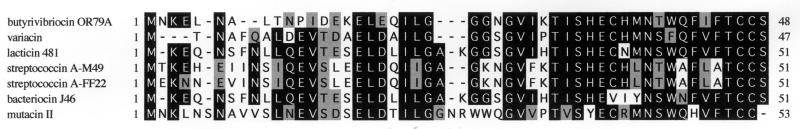

Comparison of the N-terminal sequence determined for OR79A with those of other bacteriocins revealed homology with the N-terminal regions of several previously reported type A lantibiotics (13, 16, 27, 28). A mixed oligonucleotide based on a consensus sequence derived from both the determined N-terminal sequence data and the homologous lantibiotic amino acid sequences was used to probe restriction enzyme digests of genomic DNA. Low-stringency washing of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA hybridized against this probe indicated the presence of multiple homologous DNA restriction fragments of various lengths, all of which melted off under low-stringency conditions. A second mixed-oligonucleotide probe, based on the C termini of the homologous lantibiotic sequences, was used to reprobe the blot. Low-stringency washing indicated the presence of two homologous sequences, which also hybridized with the first probe. The more-intense 4.7-kb EcoRI fragment was cloned directly from a gel slice, with the C-terminus probe being used to identify clones of interest, and the cloned fragment was sequenced in both directions. The results are presented in Fig. 2.

DNA sequence analysis.

DNA sequence analysis of the cloned 4.7-kb EcoRI fragment revealed the presence of an ORF, bvi79A (Fig. 2A), demonstrating a significant degree of homology to one combination of the determined N-terminal amino acid sequence (Fig. 2B). No other homologous sequence was present in the cloned DNA. bvi79A encoded a peptide which was identical to the determined sequence at 10 of the 15 determined positions. The blank positions (7, 9, and 12) that occurred in the N-terminal determination corresponded to a threonine, a serine, and a cysteine, respectively. Two of the determined amino acid residues did not correspond with the predicted sequence; residue 6 was a leucine instead of the predicted lysine, and residue 13 was a serine instead of the predicted histidine. bvi79A was found to encode a peptide of 48 amino acids and was preceded by the Butyrivibrio ribosome binding sequence (GGAG) located at position −10 from the initiating methionine. The N terminus of the peptide contained the double-glycine peptidase processing site, which is also found in a portion of the homologous lantibiotic sequences (Fig. 3). Cleavage at this site would give the observed N-terminal amino acid sequence and result in a mature peptide of 25 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 2,900 and a predicted pI of 7.0.

FIG. 3.

Alignment by ClustalW (11) of the deduced peptide sequence for butyrivibriocin OR79A and homologous group A lantibiotic sequences variacin (28), lacticin 481 (21), streptococcin A-M49 (15), streptococcin A-FF22 (16), bacteriocin J46 (13), and mutacin II (40). Identical residues are on a black background; conserved substitutions are on a gray background. Dashes indicate gaps introduced during the alignment.

The region immediately preceding bvi79A contained a significant number of direct repeats and two inverted repeats (Fig. 2B). It is likely that this region plays a role in the regulation of expression of bvi79A. Repetitive elements with a presumptive regulatory function have been noted in the plantaricin A (7), carnobacteriocin B2 (29), sakacin A (3), epidermin (26), and sakacin P (36) operons; the palindromic sequence in the epidermin operon appears to represent the recognition site for EpiQ, a transcriptional activator of this operon (26). A complex of direct and inverted repeats has also been found within the promoter regions of the two ORFs found on a cryptic plasmid isolated from B. fibrisolvens (10).

Five other ORFs were identified in the 4.7-kb EcoRI fragment (Fig. 2A). ORFs 1, 2, 3, and 6 demonstrated significant homology in a BLAST 2.0 alignment (1) with genes involved in lantibiotic production or immunity in other bacteria: ORF1 (a partial ORF) demonstrated homology to scnF, an ORF from the Streptococcus pyogenes FF22 lantibiotic gene cluster (23); ORF2 showed homology to lctG, a gene encoding an ABC transport protein homologue in Lactococcus lactis (31); ORF3 exhibited homology to spaE and spaF, which are involved in immunity to the lantibiotic subtilin (20); and ORF6 (a partial ORF located 168 bp downstream of bvi79A) demonstrated homology to genes encoding a number of previously reported protein sequences, including Lcn2 (30), ScnM (16), MutM (40), and CylM (9), thought to be involved in dehydration of threonine and serine residues during the formation of lantibiotics.

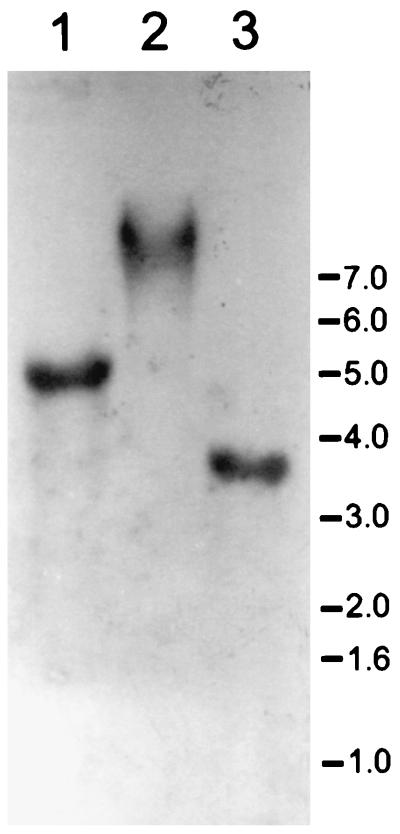

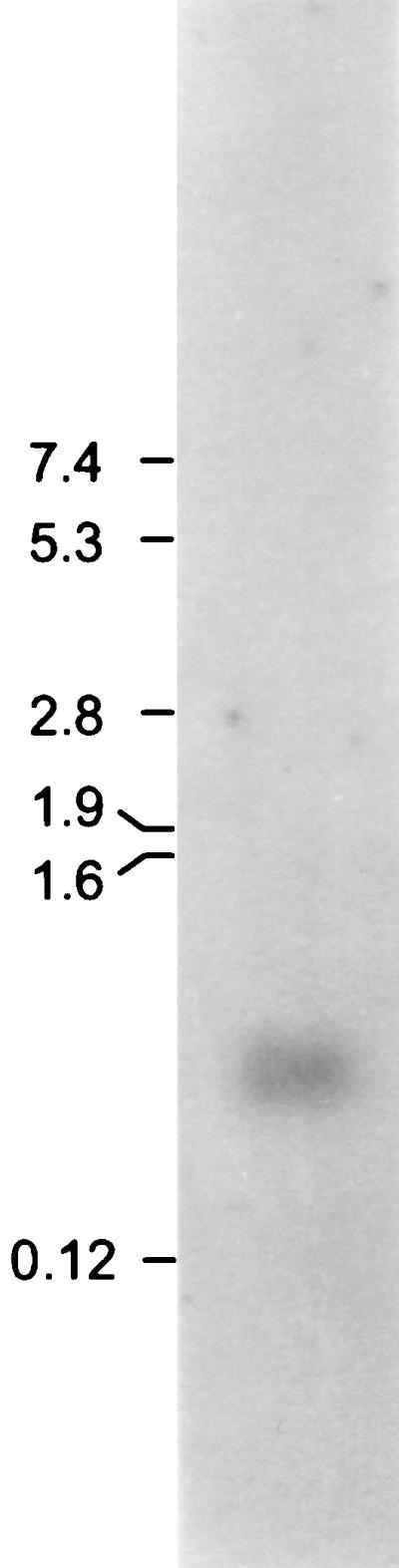

To confirm expression of bvi79A, total RNA isolated from an overnight culture was probed with an end-labeled 24-mer oligonucleotide matching a DNA sequence in the region of bvi79A coding for the mature peptide (see above). A major signal of approximately 500 bases was evident following overnight exposure of the blot (Fig. 4). This transcript is of sufficient size to encode butyrivibriocin OR79A but not ORF2 as well.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot of total RNA hybridized with the oligonucleotide probe based on the determined bvi79A nucleotide sequence. The positions and corresponding molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of RNA standards are indicated. The Northern blot was washed at 50°C with 1× SSC–0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 60 min and exposed to X-ray film overnight.

The same probe was used in an attempt to identify homologous bacteriocin genes in Southern blots of genomic-DNA digests. In all cases examined, only a single hybridizing DNA fragment was identified (Fig. 5). Degenerate oligonucleotides, one encoding an amino acid sequence common to both putative peptide sequences and the other encoding an amino acid sequence partially unique to the second putative peptide, butyrivibriocin OR79B, were also used to probe Southern blots of HindIII, EcoRI, and EcoRV genomic-DNA digests. In each case, only a single hybridizing band was identified (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Hybridization of restriction enzyme-digested bacterial DNA with the exact-match oligonucleotide probe homologous to the encoded bvi79A sequence. The blot was washed under conditions of low stringency (5× SSC–0.1% [wt/vol] SDS, 38°C, 60 min) and exposed to X-ray film overnight. Lanes: 1, EcoRI digest; 2, EcoRV digest; 3, ClaI digest. The positions and molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of DNA standards are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The bacteriocin-like activity previously identified in B. fibrisolvens OR79 held considerable interest due to its wide-ranging activity against butyrivibrios, other ruminal bacteria, and pathogenic food bacteria (18). Using a combination of ammonium sulfate and acidic precipitations, reverse-phase chromatography, and high-resolution gel filtration, an inhibitor was isolated from spent-culture fluids. The peptide nature of the inhibitor was confirmed by N-terminal analysis, total amino acid analysis, silver staining of Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing the isolated inhibitor, and, finally, cloning of a homologous gene. Our evidence indicates that two inhibitory peptides were copurified and that they represent two new lantibiotics, butyrivibriocins OR79A and OR79B.

The sensitivities of the tested butyrivibrios and other ruminal isolates toward fraction IV indicated that the isolated inhibitor was responsible for the primary activity originally characterized by the use of a deferred plating assay (18). However, three isolates which were previously sensitive in a deferred plating assay (18) were found to be resistant in a drop test with fraction IV, while four strains which were previously resistant were sensitive (Table 2). These minor differences in the observed host range likely resulted from differences in the level of bacteriocin to which the test strains were exposed or from the presence of the second, minor inhibitory component which was fractionated out of the crude extracts at the reverse-phase chromatography step. We have yet to characterize this additional inhibitory substance. It may represent an additional peptide antibiotic, since other bacteria have been reported to produce multiple bacteriocins (15, 37).

N-terminal sequence analysis of fraction IV indicated that it contained at least three distinct peptides. There was homology evident between the determined N terminus and the N termini of a number of previously reported lantibiotics, suggesting that the isolated peptides might represent new lantibiotics.

The major peptide components of fraction IV had identical N-terminal sequences, with the exception of two amino acid positions (positions 2 and 3). In addition, the amino acid composition of fraction IV correlated closely with the predicted amino acid composition of Bvi79A, indicating that all of the components contained within fraction IV were very similar.

The deduced minor peptide component (N-terminal sequence, V-I-L-X-I-X-H-E-X-) was also homologous, although its N terminus aligned with the primary sequence at the fourth amino acid from the N terminus of the major peptide species. This minor peptide may be an artifact, since it was subsequently found that storage of fraction IV under acidic conditions (i.e., in the presence of TFA) resulted in significant decreases in titer. This may have been due to degradation of the peptides. Similar N-terminal deletions have been reported in the lantibiotics epilancin K7 (38) and streptococcin A-FF22 (17). We theorize that fraction IV originally consisted of only the two closely related, although distinct, full-length peptides.

A cloning strategy which utilized two mixed-oligonucleotide probes, based on both the determined N terminus and the N- and C-terminal sequences of the homologous lantibiotics, resulted in the identification of a single homologous gene sequence (bvi79A). Our evidence supports the conclusion that this gene encodes one of the isolated peptides. First, bvi79A was expressed, as determined by Northern blotting of cells grown under the conditions used for the production of the inhibitory activity. Second, the predicted amino acid sequence of Bvi79A demonstrated a significant degree of homology to one possible amino acid combination of the determined N terminus (identical in 10 of 15 residues). Finally, bvi79A was contiguous with four other ORFs exhibiting significant homology to genes that are believed to be involved in the formation of or immunity to lantibiotics. bvi79A is thus a member of an operon organized similarly to previously reported lantibiotic-encoding operons (9, 16, 20, 23, 30, 31, 40). The presence of the genes encoding the enzymes responsible for the formation of lanthionine has been suggested to represent the definitive determinant of lantibiotic production capability in a given isolate (25).

Although the determined N-terminal sequence was not a perfect match to the encoded N-terminal sequence of bvi79A, the majority of sequence discrepancies are easily accounted for. Three positions in the N-terminal analysis of fraction IV were blank. In the N-terminal sequencing of proteins, blank positions usually arise through the degradation of cysteine or tryptophan residues. In the N-terminal sequencing of lantibiotics, blank positions can also result from the presence of the unsaturated amino acids didehydroalanine and didehydrobutyrine, formed by the dehydration of threonine and serine, respectively. In fact, the results of the total amino acid analysis support the presence of these modified amino acids. No threonines and only a single serine residue were present in fraction IV, despite the finding that bvi79A encodes three threonine and two serine residues of the predicted mature peptide. Furthermore, in bvi79A as well as several of the homologous lantibiotic sequences, these blank positions correspond to a threonine, a serine, and a cysteine residue. The three blank cycles within the determined N termini, then, likely result from the dehydration of a threonine and a serine residue and the breakdown of a cysteine residue. Only two positions within the determined N terminus were not compatible with the predicted amino acid sequence of bvi79A: a leucine in position 6 and a serine in position 13. The leucine probably represents an N-terminus amino acid sequencing error, since no leucine was detected in the total amino acid determination. The serine in position 13 of the determined sequence might also represent an amino acid sequencing error, which could be explained by the presence of a second, closely related peptide.

N-terminal sequence analysis indicated that fraction IV contained at least two major peptide components. The total amino acid analysis confirmed the N-terminal sequence results, showing the presence of a proline residue that was not part of the predicted amino acid sequence of Bvi79A (Table 3). Predictions of both the molecular mass and pI for the respective peptides (butyrivibriocin OR79A [Bvi79A], 2.86 kDa, pI = 7; butyrivibriocin OR79B [deduced sequence identical to Bvi79A except for the second and third residues, where -Q-P- replaces -N-G-], 2.91 kDa, pI = 7) explain our inability to separate these components by our purification scheme. Whether the second peptide is encoded by a second gene or represents a modification of Bvi79A is an important question. No additional gene sequence homologous to the second peptide was present in the 5.0-kb EcoRI restriction fragment encoding bvi79A. Furthermore, an oligonucleotide probe based on the region of bvi79A coding for the mature peptide failed to hybridize with any additional sequences within the genome, even under conditions of very low stringency (Fig. 5); hybridizations with degenerate probes based on the determined amino acid sequences were similarly unsuccessful. At this point, despite having been unable to detect a second gene, we cannot be certain whether butyrivibriocin OR79B represents a modified form of butyrivibriocin OR79A or is encoded by a second, related gene (15).

The peptide encoded by bvi79A demonstrated significant homology to other type A lantibiotics which contain the double-glycine leader peptidase cleavage site (Fig. 3) (25). The high degree of homology to other lantibiotics, the blank positions in the N-terminal analysis, and discrepancies between the threonine and serine contents of fraction IV and those of the predicted peptide product of bvi79A are all consistent with both peptides representing new lantibiotics.

Previous research concerning the occurrence of bacteriocin-like activities among Butyrivibrio isolates indicated that this was a widespread characteristic (18). We have demonstrated that B. fibrisolvens OR79 is a producer of lantibiotics which, despite the phylogenetic distance (39), are closely related to lantibiotics previously isolated from the lactic acid bacteria (25). Butyrivibriocin OR79 represents the second bacteriocin to be isolated from a Butyrivibrio strain of ruminal origin and characterized. The first, butyrivibriocin AR10, was not a lantibiotic (19); it demonstrated significant homology to the type IIc bacteriocin acidocin B isolated from Lactobacillus acidophilus (21). Therefore, bacteriocins representing both major groups of peptide antibiotics (24, 25) have now been isolated from B. fibrisolvens and characterized. Given that these bacteriocins represent only two such compounds obtained from a large number of isolates which demonstrated bacteriocin-like activities, the bacteriocins produced by isolates of B. fibrisolvens may be as diverse as those found among the lactic acid bacteria and may represent a good source for new bacteriocins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Dairy Farmers of Canada and the Dairy Farmers of Ontario.

Footnotes

Lethbridge Research Centre contribution no. 3879911.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelsson L, Holck A. The genes involved in production of and immunity to sakacin A, a bacteriocin from Lactobacillus sake Lb706. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2125–2137. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2125-2137.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant M P, Small N. The anaerobic monotrichous butyric acid-producing curved rod-shaped bacteria of the rumen. J Bacteriol. 1956;72:16–21. doi: 10.1128/jb.72.1.16-21.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldwell D R, Bryant M P. Medium without rumen fluid for non-selective enumeration and isolation of rumen bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1966;14:794–801. doi: 10.1128/am.14.5.794-801.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng K-J, Costerton J W. Ultrastructure of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens: a gram-positive bacterium? J Bacteriol. 1977;129:1506–1512. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.3.1506-1512.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Nes I F. Characterization of the locus responsible for the bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4472–4483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4472-4483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forster R J, Teather R M, Gong J, Deng S-J. 16S rDNA analysis of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens: phylogenetic position and relation to butyrate producing anaerobic bacteria from the rumen of white-tailed deer. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:218–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilmore M S, Segarra R A, Booth M C, Bogie C P, Hall L R, Clewell D B. Genetic structure of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded cytolytic toxin system and its relationship to lantibiotic determinants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7335–7344. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7335-7344.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hefford M A, Teather R M, Forster R J. The complete nucleotide sequence of a small cryptic plasmid from a rumen anaerobe bacterium of the genus Butyrivibrio. Plasmid. 1993;29:63–69. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins D G, Thompson J D, Gibson T J. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt J G, Krieg N R, Sneath P H A, Staley J T, Williams S T, editors. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 9th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hout E, Meghrous J, Barrena-Gonzalez C, Petitdemange H. Bacteriocin J46, a new bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris J46: isolation and characterization of the protein and its gene. Anaerobe. 1996;2:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hungate R E. Introduction: the ruminant and the rumen. In: Hobson P N, editor. The rumen microbial ecosystem. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier Applied Science; 1988. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes W L, Friend V L, Ferretti J J. Duplication of the lantibiotic structural gene in M-type 49 group A streptococcus strains producing streptococcin A-M49. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4207–4209. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4207-4209.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynes W L, Ferretti J J, Tagg J R. Cloning of the gene encoding streptococcin A-FF22, a novel lantibiotic produced by Streptococcus pyogenes, and determination of its nucleotide sequence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1969–1971. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1969-1971.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack R W, Tagg J R. Isolation and partial structure of streptococcin A-FF22. In: Jung G, Sahl H-G, editors. Nisin and novel lantibiotics. Leiden, The Netherlands: Escom Publishers; 1991. pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalmokoff M L, Teather R M. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriocin (butyrivibriocin AR10) from the ruminal anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens AR10: evidence in support of the widespread occurrence of bacteriocin-like activity among ruminal isolates of B. fibrisolvens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:394–402. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.394-402.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalmokoff M L, Whitford M, Teather R M. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding butyrivibriocin AR10, a bacteriocin produced by the rumen anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens AR10, abstr. O-73; p. 431. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein C, Entian K-D. Genes involved in self-protection against the lantibiotic subtilin produced by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2793–2801. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2793-2801.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leer R J, van der Vossen J M B M, Van Giezen N, van Noort J M, Pouwels P H. Genetic analysis of acidocin B, a novel bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Microbiology. 1995;141:1629–1635. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannarelli B M. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness among strains of the species Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:340–347. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin R E, Hines W L. Complete sequence of the Streptococcus pyogenes FF22 lantibiotic (scn) gene cluster. GenBank accession no. AF026542. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nes I F, Diep D B, Havarstein L S, Brurberg M B, Eijsink V, Holo H. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00395929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nes I F, Tagg J R. Novel lantibiotics and their pre-peptides. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:89–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00399414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peschel A, Augustin J, Kupke T, Stevanovic S, Gütz F. Regulation of epidermin biosynthesis genes by EpiQ. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piard J C, Kuipers O P, Rollema H S, Desmazeaud M J, De Vos W M. Structure, organization, and expression of the lct gene for lacticin 481, a novel lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16361–16368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pridmore D, Rekhif N, Pittet A-C, Suri B, Mollet B. Variacin, a new lanthionine-containing bacteriocin produced by Micrococcus varians: comparison to lacticin 481 of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1799–1802. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1799-1802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quadri L E N, Kleerebezem M, Kuipers O P, De Vos W M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Characterization of a locus from Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B involved in bacteriocin production and immunity: evidence for global inducer-mediated transcriptional regulation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6163–6171. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6163-6171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rince A, Dufour A, Le Pogam S, Thuault D, Bourgeois C M, Le Pennec J P. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of genes involved in production of lactococcin DR, a bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1652–1657. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1652-1657.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rincé A, Dufour A, Uguen P, Le Pennec J-P, Haras D. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4252–4260. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4252-4260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen K M, Lamerti E D, Villa-Komaroff L. Optimizing the Northern blot procedure. BioTechniques. 1990;8:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart C S, Bryant M P. The rumen bacteria. In: Hobson P N, editor. The rumen microbial ecosystem. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier Applied Science; 1988. pp. 21–76. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tagg J R, Dajani A S, Wannamaker L W. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:722–756. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.722-756.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tichaczek P S, Vogel R F, Hammes W P. Cloning and sequencing of sap encoding sakacin P, the bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus sake LTH 673. Microbiology. 1994;140:361–367. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Belkum M J, Kok J, Venema G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of lcnB, a third bacteriocin determinant from the lactococcal bacteriocin plasmid p9B4-6. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:572–577. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.572-577.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van De Kamp M, Horstink L M, Van Den Hooven H W, Konings R N H, Hilbers C W, Frey A, Sahl H G, Metzger J W, Van De Ven F J M. Sequence analysis by NMR spectroscopy of the peptide lantibiotic epilancin K7 from Staphylococcus epidermidis K7. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:757–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willems A, Amat-Marco M, Collins M D. Phylogenetic analysis of Butyrivibrio strains reveals three distinct groups of species within the Clostridium subphylum of the gram-positive bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:195–199. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodruff W A, Novak J, Caufield P W. Sequence analysis of mutA and mutM genes involved in the biosynthesis of the lantibiotic mutacin II in Streptococcus mutans. Gene. 1998;206:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]