Abstract

The degradation of natural habitats is causing ongoing homogenization of biological communities and declines in terrestrial insect biodiversity, particularly in agricultural landscapes. Orthoptera are focal species of nature conservation and experienced significant diversity losses over the past decades. However, the causes underlying these changes are not yet fully understood. We analysed changes in Orthoptera assemblages surveyed in 1988, 2004 and 2019 on 198 plots distributed across four major grassland types in Central Europe. We demonstrated compositional differences in Orthoptera assemblages found in wet, dry and mesic grasslands, as well as ruderal habitats decreased, indicating biotic homogenization. However, mean α-diversity of Orthoptera assemblages increased over the study period. We detected increasing numbers of species with preferences for higher temperatures in mesic and wet grasslands. By analysing the temperature, moisture and vegetation preferences of Orthoptera, we found that additive homogenization was driven by a loss of species adapted to extremely dry and nitrogen-poor habitats and a parallel spread of species preferring warmer macroclimates.

Keywords: additive homogenization, timeseries, insect decline

1. Introduction

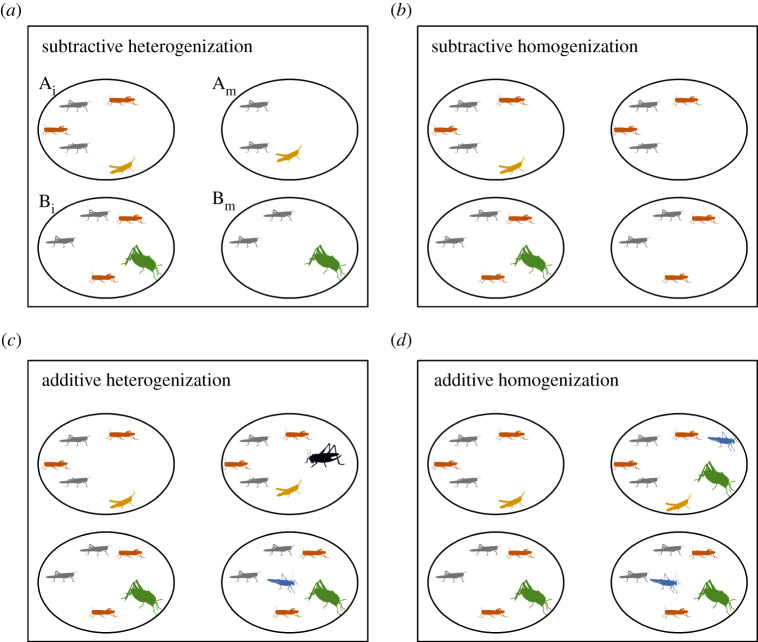

The conversion and degradation of natural habitats are causing ongoing biodiversity declines worldwide [1]. Recent studies have highlighted a decrease in terrestrial insect abundance by approximately 9% worldwide [2]. Scientists hence call for increased efforts to protect insect diversity [3,4]. Parallel to the decline of local diversity (α-diversity), compositional differences between localities (β-diversity) decrease over time [5]. This phenomenon is called ‘biotic homogenization’ [6,7]. Biotic homogenization can be caused by colonization into and extinction of species from local communities [8]. Such changes can theoretically be classified into four major cases (figure 1). First, α-diversity decreases when locally common species disappear from some or all sites, which leads to increasing dissimilarities among communities (subtractive heterogenization). Second, α- and β-diversity increase because of new species colonizing some but not all sites (additive heterogenization). By contrast, α- and β-diversities decrease when rare species disappear (subtractive homogenization). However, in an extreme case, additive homogenization may lead to an increase in α-diversity, while simultaneously vanishing dissimilarities among sites [9].

Figure 1.

Theoretical mechanisms explaining patterns of β-diversity as a consequence of species loss (subtractive processes) or species gain (additive processes) (adapted from [9]). β-Diversity between initial habitats {Ai, Bi} increases over time to the modified sites {Am, Bm} when (a) common species disappear from some or all sites leading to decreases in species numbers but increases in dissimilarities among communities, or when (b) new species colonize some but not all sites leading to increases in the number of species but also to increases in dissimilarities among communities. By contrast, β-diversity decreases, when (c) non-ubiquitous species disappear leading to decreases in the number of species and community dissimilarities, or when (d) formerly rare or absent species become common, increasing the number of species but decreasing community dissimilarities.

The distribution of species' ecological and physiological traits in a local community has become important for understanding links between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning [10] and for rapidly detecting biodiversity responses to global change [11]. Species traits are increasingly used to unravel mechanisms behind insect declines, exemplified for nocturnal moths [12], water beetles [13] and dragonflies [14]. Furthermore, species traits can determine their performance under changes in land use, for example, and hence drive biotic homogenization [15].

Orthoptera (Insecta) are focal species of conservation in open habitats [16] and some of them are commonly used as bioindicators [17,18]. Vegetation structure and microclimate, e.g. moisture and temperature, are among the most striking habitat features affecting orthopteran assemblages [19]. Most Central European Orthoptera species demand high ambient temperatures or radiation to successfully complete their life cycle [20]. Nevertheless, some species with drought-susceptible eggs are restricted to areas with high soil moisture or high precipitation [20]. Before the beginning of the twenty-first century, more than three-quarters of all Orthoptera species in Germany experienced severe range losses [21]. These range losses were more pronounced for habitat specialists and species with low dispersal ability compared to their generalist relatives [22]. However, the relative importance of ecological and/or physiological traits of species contributing to species declines and community changes over time remains largely unclear.

We investigated changes in Orthoptera diversity in four different habitat types covering a gradient from very dry to very wet meadows. We quantified changes in species communities and trait composition over three consecutive time steps from 1988 to 2019 and assessed whether changes over time differed for specific groups. We tested (I) whether differences between Orthoptera assemblages found in ruderal habitats, wet, dry and fertilized meadows decrease over time, i.e. biotic homogenization takes place and (II) if potential homogenization is related to shifts in incidence frequencies of specific traits, such as moisture or (micro- and macro-) temperature preferences.

2. Material and methods

(a) . Study area

The study was conducted in the Hassberge region in northern Bavaria, Germany (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), covering a total area of around 950 km2. The mean annual temperature is about 10°C in this region and the mean annual precipitation is around 600 mm (meteorological station ‘Köslau’). During the study period, mean temperatures for summer (May–October) and winter months (November–April) increased by almost 1.5°C (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). However, mean precipitation of summer and winter months did not change over the last 30 years (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

We selected a total of 198 study grasslands classified into four major types, namely wet grasslands (n = 39), mesic grasslands (n = 42), dry grasslands (n = 92) and ruderal habitats (n = 25) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Grasslands were classified based on characteristic plant species according to [23]. Wet grasslands included wet meadows, wet trenches, sedge fens and reeds, often located in proximity to small streams and covered with e.g. Alopecurus pratensis, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Carex disticha, Cardamine pratensis and Caltha palustris. Wet grasslands were not fertilized, and mown once or twice per year. Mesic grasslands were mown two to three times per year and typically fertilized with liquid manure after mowing. Characteristic plant species occurring in mesic grasslands were Alopecurus pratensis, Dactylis glomerata, Phleum pratense, Anthriscus sylvestris and Taraxacum officinale. Ruderal habitats included fallows, roadside vegetation, forest edges, field margins, embankments and quarries, often colonized by Artemisia vulgaris, Senecio jacobaea, Cirsium vulgare, Dactylis glomerata and Heracleum sphondylium. Ruderal habitats were not fertilized and typically not mown. Dry grasslands referred to nutrient-poor, semi-arid and arid habitats such as calcareous or silicate grasslands, dry pastures, dry meadows, slopes and dry orchard meadows. Typically occurring plant species were Arrhenatherum elatius, Bromus erectus, Cirsium acaule, Dianthus carthusianorum and Centaurea scabiosa. Dry grasslands were unmanaged or extensively managed, i.e. mown once or twice per year and not fertilized. Grasslands were on average 2.6 ± 3 ha in size. For all studied grassland patches, the classification and management did not change between 1988 and 2019.

(b) . Orthoptera surveys

Orthoptera surveys were conducted once per plot and year between mid-July and mid-September under sunny weather conditions without rain and strong wind. All visual and acoustic observations of orthopterans were recorded. We identified stridulating males in field to species level via their species-specific songs [18,24]. Sweep netting and capture by direct search were additionally used to record species restricted to specific microhabitats, such as Tetrix spp. Morphological determination of non-stridulating species followed Fischer et al. [25]. Depending on the respective size of the study plot, we spent between 15 and 90 min (30 min on average) to survey the plot. Surveys were either conducted by one or two observers and completed once the entire area of a grassland has been examined. All study sites were sampled in 1988, 2004 and 2019.

(c) . Data analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out in R v. 4.0.5 (www.r-project.org). Prior to statistical analyses, we removed occasionally recorded tree-living species (Barbitistes spp.), ant crickets (Myrmecophilus acervorum) and mole crickets (Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa), since our sampling scheme did not sufficiently cover them. We used incidence-based rarefaction-extrapolation of sample coverage, provided by the r-package iNEXT, to check our data for sufficient sampling effort [26,27]. This approach revealed high sample completeness across grassland types and study years (electronic supplementary material, figure S4).

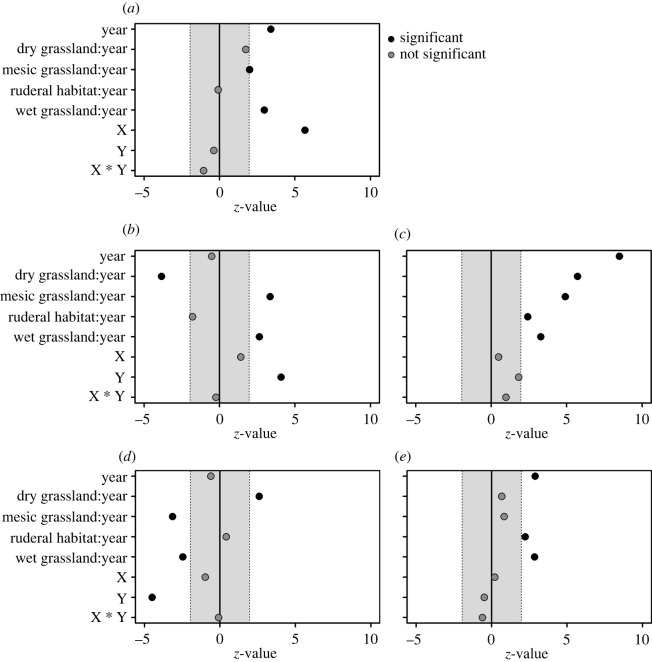

We modelled the influence of grassland type on the number of species by generalized linear mixed models for Poisson-distributed data [28] provided by the ‘lme4’ package [29]. To this end, we fitted a model with year as a predictor and site identity as a random effect to test for the overall effect of the year. Furthermore, we included a second-order trend surface to the model by adding the geographic coordinates and their interaction to account for possible spatial autocorrelation [30]. Afterwards, we tested the effect of year separately for each grassland type, in the form ‘grassland type: year’ (figure 2a). These grassland type specific z-values are presented together with the global estimated z-values for all other variables (figure 2).

Figure 2.

z-Values, i.e. standardized model estimates, of different generalized linear mixed models for (a) species number, (b) microclimate preferences, (c) macroclimate preferences, (d) moisture preferences and (e) vegetation preferences of Orthoptera communities.

Second, we used the same model formula with a binomial linear mixed model to test the effect of the year on the occurrence probability for each species separately. Here, we additionally included the site as a random effect to account for repeated surveys on the same plot. For this analysis, we removed all species, which were only recorded in a single year. This approach yields a standardized measure of species incidence increase or decrease over the study period (electronic supplementary material, figure S5).

We calculated the mean preference of Orthoptera assemblages regarding their microclimate, macroclimate, moisture and vegetation preferences (figure 2b–e). Therefore, we extracted the corresponding means of species' niches in Central Germany provided by [20] and species’ temperature index (STI) for Germany provided by [21] (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Here, vegetation preferences range from 5 (preference for shrubs, trees, higher vegetation) to 9 (preference for extremely sparse, or no vegetation). Mean humidity preferences range from 1.5 (preference for extremely dry habitats) to 8 (preference for extremely wet habitats). The STI represents a species macroclimate preference and increases with increasing preference for warmer regions. The microclimate preference ranges from 4 to 9 and increases with increasing preference for warm microclimates, i.e. warm habitats. Congruent to indicative values of plants, the microclimatic preferences of Orthoptera species were classified based on their habitat affinity within a region, whereas the macroclimatic preferences (STI) were based on the overlap of distribution records in Germany with long-term mean summer temperatures. Afterwards, we analysed the resulting mean preferences for all assemblages in linear mixed models using the same procedure as for species numbers.

To analyse the effects of grassland type on species assemblages within each year, we used permutational multivariate analysis of variance [31], provided by the ‘vegan’ package [32]. Bray–Curtis distances were used to derive the associated resemblance matrices. Community composition was visualized using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (square root transformation, Wisconsin double standardization; [33]). Finally, we used multivariate homogeneity of group dispersions analysis [34], calculated by means of the function ‘betadisper’ in the ‘vegan’ r-package [32], to compare mean pairwise dissimilarities between grassland types. This analysis tests whether the average distance to the centroid of a given grassland type (β-dispersion), differs between types. High β-dispersion indicates heterogeneous communities, while low β-dispersion indicates homogeneous communities (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

3. Results

In total, we recorded 39 species of Orthoptera from 1988 to 2019. Numbers of species varied between years, with 37 species recorded in 1988, 33 species recorded in 2004 and 35 in 2019. Psophus stridulus, Chorthippus apricarius and Chorthippus vagans were exclusively found in 1988. Ten species experienced significant incidence declines over the study period, including Metrioptera brachyptera, Euthystira brachyptera, Isophya kraussii, Pseudochorthippus montanus and Pholidoptera griseoaptera (electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S1). Vice versa, 10 species showed significantly increasing occurrence probabilities over the study period, including Platycleis albopunctata, Stethophyma grossum and Oedipoda caerulescens (electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S1).

Overall, the number of species per site significantly increased from 7.1 ± 2.9, to 7.5 ± 2.5, to 8 ± 3.1 over the course of the investigated years. This increase was driven by a gain in species in wet grasslands and mesic grasslands (figure 2a). We found no overall changes in microclimate and moisture preferences over the study period (figure 2b,d). However, the mean preferences of Orthoptera assemblages changed within the different grassland types. Assemblages in dry grasslands decreased in their mean microclimate preference due to a gain in species that occur on average in less xeric habitats (figure 2b,d). Vice versa, wet grasslands gained species preferring drier and warmer habitats, but lost species specialized to very wet habitats (figure 2d). Mesic grasslands have experienced a gain in species preferring drier and warmer microhabitats, while simultaneously lost species adapted to wet habitats (figure 2d). However, Orthoptera assemblages in all grassland types were increasingly assembled from species with preferences for warmer macroclimates, i.e. species, which are, on average, distributed in warmer regions (figure 2c). Overall, Orthoptera assemblages shifted towards species that are adapted to less heterogeneous vegetation, indicated by a change in vegetation preferences in wet grasslands (figure 2e).

Permutational analyses of variance revealed a decreasing influence of grassland type, indicated by decreasing F-values over the study period (table 1). This finding depicts community homogenization over time (electronic supplementary material, figure S6). β-Diversity within grassland types did not differ between grassland types, except in 2019, where ruderal habitats had significantly larger β-dispersion (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Table 1.

Effect of grassland type on the assemblage composition of Orthoptera obtained from permutational multivariate analysis of variance.

| year |

degrees of freedom | sequential sums of squares | mean squares | F-statistics | partial r² | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | grassland type | 3 | 9.397 | 3.132 | 21.649 | 0.251 | 0.001*** |

| residuals | 194 | 28.069 | 0.145 | 0.749 | |||

| total | 197 | 37.466 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2004 | grassland type | 3 | 5.305 | 1.768 | 18.263 | 0.220 | 0.001*** |

| residuals | 194 | 18.786 | 0.097 | 0.780 | |||

| total | 197 | 24.091 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2019 | grassland type | 3 | 4.813 | 1.604 | 14.386 | 0.182 | 0.001*** |

| residuals | 194 | 21.635 | 0.112 | 0.818 | |||

| total | 197 | 26.448 | 1.000 | ||||

4. Discussion

Our study revealed an increase in the mean number of Orthoptera species per plot, while communities tended to homogenize over the 30-year-study period. This homogenization was mainly caused by the loss of species specialized in extremely dry habitats, while species originating from warmer macroclimates have become more frequent. Our results depict an increase in α-diversity over time (figure 1), while compositional differences between grassland types decrease (table 1), corresponding to the concept of additive homogenization [9]. This increasing homogenization appears to be driven by the colonization of different grassland types by species with broad temperature and moisture niches and the simultaneous loss of species exclusively found in, e.g. dry or wet habitats [24,35]. Recently, numerous mobile and thermophilic Central European Orthoptera species have expanded their distributional ranges, which is commonly attributed to more favourable weather conditions with progressing climate change [19,21]. Decreasing differences between trait distributions of the different habitat types can be explained by the spread of species, which thrive under a broad range of environmental conditions, into dry, mesic, and wet habitats.

A counterintuitive finding is that these broadly tolerant species, which contributed most to the additive homogenization, were not already widely distributed across different grassland types before. Although their temperature, moisture and vegetation structure niches are broad [18], former microclimatic temperatures of mesic and wet grassland habitats in the study region might have been below the temperature optima of the species. While species inhabit a broad range of habitats under favourable macroclimates, they may be restricted to habitats close to their optima under less favourable macroclimatic conditions. As most spreading species originate from continental climates [20], warm and dry summers during the last two decades may have supported their spread into different grassland types.

In our study, we found an increasing number of sites colonized by mobile, macropterous species, for instance Oedipoda caerulescens, Chorthippus dorsatus and Chorthippus brunneus, which occur in a wide range of habitats [36]. These species contribute to an increase in mean macroclimatic temperature preferences and a simultaneous decrease in compositional differences between grassland types. As annual temperatures rose over time in the study region (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), a parallel increase in macroclimatic preferences of Orthoptera might be expected [23,25]. Contrarily, several specialized species of dry habitats, including Psophus stridulus, Omocestus haemorrhoidalis and Chorthippus vagans, could not be recorded in 2019. A reason for their decrease might be found in environmental microclimatic changes in the respective habitats [22]. In line with our findings are distributional range retractions of those specialized species, which are also weak dispersers, before the twenty-first century in Germany [21]. Furthermore, we did not detect the expected shift in microclimatic preferences towards heat-adapted species (figure 2). A reason for this development could be the deterioration in favourable micro-habitats by the abandonment of extensive management regimes. Simultaneously, atmospheric nitrogen deposition and leaching from arable fields in agricultural landscapes change vegetation structure by supporting dense swards of tall, competitive plant species [37]. Dense swards decrease soil temperatures, crucial for egg maturation and larval growth, which is particularly detrimental to species adapted to dry, sparsely vegetated and warm micro-habitats [38].

Furthermore, Orthoptera assemblages found in different grassland types increased in similarity because species, which require high soil moisture due to drought-susceptible eggs, suffered during the studied period. Most severely, Pseudochorthippus montanus and Omocestus viridulus decreased in occurrences in wet and mesic grasslands, possibly due to environmental changes in those habitats caused by summer droughts and evaporation. Although mean summer precipitation in our study area did not change, drought periods during summer have become more frequent [39].

Our results depicted a loss of species adapted to structural-rich vegetation (figure 2). This might be caused by an ongoing intensification of agricultural land-use, accompanied by a loss of habitat features that increase heterogeneity, e.g. shrubs and tall herbaceous plants. Indeed, land use intensification mediated through mowing frequency, grazing, irrigation and fertilization negatively affect many Orthoptera species [24,40]. Moreover, the effect was particularly strong in wet grasslands (figure 2), which used to have a high structural heterogeneity in the past. A loss of species that require either very dry and open or summer-moist habitats, together with a leaching of species with intermediate temperature and moisture preferences due to broad niches into all grassland types, led to additive biotic homogenization across grassland types in the study region. Micro- and macroclimatic preferences shed light on winners and losers of global change. While mobile and thermophilic species may be able to colonize new habitats, conservation efforts should focus to maintain habitat quality in wet and dry habitats to ensure the survival of specialized species.

Acknowledgements

The surveys in 1988 and 2004 were financially supported by ‘Bund Naturschutz in Bayern e. V.’ and the ‘Bayerischer Naturschutzfonds'. We thank the botanist Otto Elsner for support during the study site selection.

Data accessibility

All data associated with this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material [41].

Authors' contributions

S.T.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; S.K.: investigation, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; O.F.-L.: investigation and writing—review and editing; J.G.: investigation and writing—review and editing; J.G.: investigation and writing—review and editing; J.T.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources and writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

References

- 1.Newbold T, et al. 2015. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45-50. ( 10.1038/nature14324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Klink R, Bowler DE, Gongalsky KB, Swengel AB, Gentile A, Chase JM. 2020. Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances. Science 368, 417-420. ( 10.1126/science.aax9931) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samways MJ, et al. 2020. Solutions for humanity on how to conserve insects. Biol. Conserv. 242, 108427. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108427) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey JA, et al. 2020. International scientists formulate a roadmap for insect conservation and recovery. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 174-176. ( 10.1038/s41559-019-1079-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori AS, Isbell F, Seidl R. 2018. β-diversity, community assembly, and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 549-564. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2018.04.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olden JD, LeRoy Poff N, Douglas MR, Douglas ME, Fausch KD. 2004. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of biotic homogenization. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 18-24. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olden JD. 2006. Biotic homogenization: a new research agenda for conservation biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 33, 2027-2039. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01572.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, Cadotte MW, Meiners SJ, Hua Z, Jiang L, Shu W. 2015. Species colonisation, not competitive exclusion, drives community overdispersion over long-term succession. Ecol. Lett. 18, 964-973. ( 10.1111/ele.12476) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Socolar JB, Gilroy JJ, Kunin WE, Edwards DP. 2016. How should beta-diversity inform biodiversity conservation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 67-80. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2015.11.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagg C, Schlaeppi K, Banerjee S, Kuramae EE, van der Heijden MGA. 2019. Fungal–bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4841. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-12798-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacifici M, Visconti P, Butchart SHM, Watson JEM, Cassola FM, Rondinini C. 2017. Species’ traits influenced their response to recent climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 205-208. ( 10.1038/nclimate3223) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth N, Hacker HH, Heidrich L, Friess N, García-Barros E, Habel JC, Thorn S, Müller J. 2021. Host specificity and species colouration mediate the regional decline of nocturnal moths in central European forests. Ecography (Cop.) 44, 941-952. ( 10.1111/ecog.05522) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth N, Zoder S, Zaman AA, Thorn S, Schmidl J. 2020. Long-term monitoring reveals decreasing water beetle diversity, loss of specialists and community shifts over the past 28 years. Insect Conserv. Divers. 13, 140-150. ( 10.1111/icad.12411) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha-Ortega M, Rodríguez P, Bried J, Abbott J, Córdoba-Aguilar A. 2020. Why do bugs perish? Range size and local vulnerability traits as surrogates of Odonata extinction risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20192645. ( 10.1098/rspb.2019.2645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gámez-Virués S, et al. 2015. Landscape simplification filters species traits and drives biotic homogenization. Nat. Commun. 6, 8568. ( 10.1038/ncomms9568) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samways MJ, Lockwood JA. 1998. Orthoptera conservation: pests and paradoxes. J. Insect Conserv. 2, 143-149. ( 10.1023/a:1009652016332) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fartmann T, Krämer B, Stelzner F, Poniatowski D. 2012. Orthoptera as ecological indicators for succession in steppe grassland. Ecol. Indic. 20, 337-344. ( 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.03.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvořák T, Hadrava J, Knapp M. 2022. The ecological niche and conservation value of Central European grassland orthopterans: a quantitative approach. Biol. Conserv. 265, 109406. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109406) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Löffler F, Poniatowski D, Fartmann T. 2019. Orthoptera community shifts in response to land-use and climate change–lessons from a long-term study across different grassland habitats. Biol. Conserv. 236, 315-323. ( 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.05.058) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingrisch S, Köhler G. 1998. Die Heuschrecken Mitteleuropas. Magdeburg, Germany: Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poniatowski D, Beckmann C, Löffler F, Münsch T, Helbing F, Samways MJ, Fartmann T. 2020. Relative impacts of land-use and climate change on grasshopper range shifts have changed over time. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 2190-2202. ( 10.1111/geb.13188) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhardt K, Köhler G, Maas S, Detzel P. 2005. Low dispersal ability and habitat specificity promote extinctions in rare but not in widespread species: the Orthoptera of Germany. Ecography (Cop.) 28, 593-602. ( 10.1111/j.2005.0906-7590.04285.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dierschke H, Briemle G. 2002. Kulturgrasland. Stuttgart, Germany: Ulmer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fumy F, Löffler F, Samways MJ, Fartmann T. 2020. Response of Orthoptera assemblages to environmental change in a low-mountain range differs among grassland types. J. Environ. Manage. 256, 109919. ( 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109919) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer J, Steinlechner D, Zehm A, Poniatowski D, Fartmann T, Beckmann A, Stettmer C. 2016. Die Heuschrecken Deutschlands und Nordtirols: Bestimmen - Beobachten - Schützen. Wiebelsheim, Germany: Quelle & Meyer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao A, et al. 2020. Quantifying sample completeness and comparing diversities among assemblages. Ecol. Res. 35, 292-314. ( 10.1111/1440-1703.12102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A. 2016. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1451-1456. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12613) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolker BM, Brooks ME, Clark CJ, Geange SW, Poulsen JR, Stevens MHH, White JSS. 2009. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 127-135. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hothorn T, Müller J, Schröder B, Kneib T, Brandl R. 2011. Decomposing environmental, spatial, and spatiotemporal components of species distributions. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 329-347. ( 10.1890/10-0602.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legendre P, Anderson MJ. 1999. Distance-based redundancy analysis: testing multispecies responses in multifactorial ecological experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 69, 1-24. ( 10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0001:DBRATM]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oksanen J, et al. 2013. Package ‘vegan’. R Packag. ver. 2.0–8, 254. ( 10.4135/9781412971874.n145) [DOI]

- 33.Faith DP, Minchin PR, Belbin L. 1987. Compsitional dissimilarity as a robust measure of ecological distance. Vegetatio 69, 57-68. ( 10.1007/bf00038687) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson MJ. 2006. Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics 62, 245-253. ( 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00440.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gossner MM, et al. 2016. Land-use intensification causes multitrophic homogenization of grassland communities. Nature 540, 266-269. ( 10.1038/nature20575) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlumprecht H, Waeber G. 2003. Heuschrecken in Bayern. Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany: Verlag Eugen Ulmer GmbH & Co Stuttgart. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendriks RJJ, Carvalheiro LG, Kleukers RMJC, Biesmeijer JC. 2013. Temporal–spatial dynamics in Orthoptera in relation to nutrient availability and plant species richness. PLoS ONE 8, 1-10. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0071736) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schirmel J, Gerlach R, Buhk C. 2019. Disentangling the role of management, vegetation structure, and plant quality for Orthoptera in lowland meadows. Insect Sci. 26, 366-378. ( 10.1111/1744-7917.12528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brasseur GP, Jacob D, Schluck-Zöller S. 2017. Klimawandel in Deutschland—Entwicklung, Folgen, Risiken und Perspektiven. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chisté MN, Mody K, Gossner MM, Simons NK, Köhler G, Weisser WW, Blüthgen N. 2016. Losers, winners, and opportunists: how grassland land-use intensity affects orthopteran communities. Ecosphere 7, 1-15. ( 10.1002/ecs2.1545) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorn S, König S, Fischer-Leipold O, Gombert J, Griese J, Thein J. 2022. Temperature preferences drive additive biotic homogenization of Orthoptera assemblages. FigShare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5976644) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Thorn S, König S, Fischer-Leipold O, Gombert J, Griese J, Thein J. 2022. Temperature preferences drive additive biotic homogenization of Orthoptera assemblages. FigShare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5976644) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material [41].